Mandibular Growth Anomalies || The Le Fort l-Type Mobilization Procedure

Transcript of Mandibular Growth Anomalies || The Le Fort l-Type Mobilization Procedure

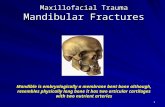

CHAPTER 21

The Le Fort 1-Type Mobilization Procedure

21.1 Terminology

First a remark on the terminology. All authors who have published on the problem of advancing the retrodisplaced maxilla called it "Le Fort !-osteotomy advancement". When I started to work on this I also produced real Le Fort I osteotomies. That means the osteotomy line was the same as in a traumatic fracture. What is generally done since I published the mobilization of the maxilla as a standard procedure is not a Le Fort I fracture, as the pterygoid processes are not included. I was wrong to call it a Le Fort I osteotomy. That is the reason why I have changed to the term LeFort 1-type osteotomy, just in order to be correct.

21.2 Historical Background

My teacher, Richard Trauner, and I had a common interest in maxillo-mandibular disharmonies. With his extensive experience in all fields of our specialty, discussing problems with him was very stimulating and rewarding.

We were examining a case of what we then called a pseudoprognathism. It was towards the end of 1952, when Trauner suggested we find a new osteotomy procedure on the mandible with broader contacting raw bone surfaces for the correction of the prognathic mandible. He said, in many cases of so-called prognathism, the cause is the retropositioned maxilla, not that the mandible is too far forward. If we could reposition the maxilla anteriorly that would be a tremendous advance in the correction of many facial skeletal anomalies.

It is not intended to report here all historical details on the subject of mobilizing the maxilla, mentioned in the literature. R. Drommer (1986) has published an excellent paper on the history of the Le Fort I -type osteotomy procedure. It makes very interesting and worthwhile reading. I can only repeat what has been published already. However, I do want to mention the very important historical steps of this subject.

The surgical mobilization of the maxilla has a long history. It started with an operation for gaining temporary access to the epipharynx and the base of the skull.

For that purpose, the maxilla was cut horizontally through an extensive horizontal facial incision and also sagittaly by dividing the upper lip, which in the German language was first reported by B. Langenbeck (1859) and in the United States by D. Cheever (1867). Temporary mobilization of the maxilla was then used for the same purpose quite frequently, however, using an oral access only. To close an open bite M. Wassmund (1935), reported that in 1927 he had separated the maxilla as a Guerin-type fracture without separating it from the pterygoid processes. He used elastics to rotate the maxilla into occlusion with the mandible. So, that was not a complete mobilization of the maxilla. G. Axhausen reported repeatedly ( 1934, 1936, 1939) successful anterior repositioning of the maxilla in post-trauma patients as well as in cleft cases by the use of elastics after complete osteotomy of the maxilla, including separation of the pterygoid processes from the maxilla. K. Schuchardt (1942) after he had detached the pterygoid processes in a second operation, used weight traction to reposition the maxilla in a post-traumatic war case. He stated that this procedure would have a large application in cleft cases, but in such cases it will probably never come into use.

When, in 1975, I was invited by R. Dingmann to Ann Arbor as a guest speaker to a postgraduate course on cleft lip and palate, to explain my philosophy on the correction of secondary deformities in cleft cases, I presented cases for which I had done the maxillary advancement in one, or two or three pieces for unilateral and bilateral cleft cases and I presented cases of Le Fort III advancement osteotomy and Le Fort III and simultaneously additional Le Fort I corrections (H. Obwegeser 1969). In the discussion, Dingmann congratulated me on the results and said that we Europeans were far ahead in the correction of these anomalies. I replied that Dingmann himself had published in 1951 on Le Fort I and Le Fort III osteotomies in posttraumatic cases. He said, did I ? He had forgotten.

J.M. Converse and H. Shapiro (1952) and I. Cupar (1954) used an almost circular incision in the vestibulum for the horizontal osteotomy and in addition they raised the whole palatal covering in performing the transpalatal and retromolar osteotomies. As for mobilizing the maxilla completely, the nasal mucosa must

H. L. Obwegeser, Mandibular Growth Anomalies© Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2001

386 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort 1-Type Mobilization Procedure

also be reflected, that procedure does not seem to leave enough blood supply to the maxilla, when it is moved forward for quite a distance. It did not come into general usage either.

When I trained with Sir Harold Gillies in 1951/52 I had the privilege of assisting him in quite a number of cleft cases in which he did aLe FortI-type osteotomy for correcting the collapsed segments of the maxilla and their vertical deficiency. Through the help of N.L. Rowe the segments were fixed in the new position by cast cap splints with a connecting bar, attached to a headcap of plaster of Paris. The gaps between the laterally and downwardly rotated maxillary segments were filled with cancellous bone chips. These bone transplants were covered by the mobilized vestibular mucosa only, but were otherwise in open communication with the antral and nasal cavities. They all healed well. However, I never saw him mobilize a maxillary segment or the whole maxilla completely for repositioning it further anteriorly. Also in the publication of H. G. Gillies and N. L. Rowe (1954) all illustrated cases were handled in the same way as "greenstick fractures", as also did H. G. Gillies and R. Millard in 1957. The same is true for the cases shown in the publications of P. Cernea et a!. (1955) and J. Levignac (1958).

In the German literature W. Widmaier ( 1960) reported that his chief, Eduard Schmid, had corrected the retrodisplaced maxilla in several cleft cases by performing a Guerin-type fracture on the two halves of the maxilla. A horizontal vestibular incision was used to expose the anterior surface of the maxilla and the osteotomy was performed with an osteotome. Occasionally, E. Schmid tunnelled the vestibular mucosa to secure the blood supply to the maxilla in cases in which the very scarred palatal mucosa had to be "detached". Separating the junction between the pterygoid plates and the maxilla was accomplished with an osteotome via the maxillary sinus. Sometimes it was additionally necessary to detach the pterygoid processes through a small incision in the palate. By rotational movements of the osteotome or by a gentle blow with the hammer, the alveolar process of the maxilla was made sufficiently mobile. That is the description of E. Schmid's procedure by his co-worker W. Widmaier. Nothing is mentioned about additional mobilization or advancement of the maxillary segments. The results of the cases shown in that publication are the result of lateral rotation of the maxillary segments only, similar to those of H.G. Gillies and R. Millard (1957). The cases published byW. Widmaier also do not permit the conclusion that the maxillary segments had been advanced. Regrettably, there is no publication in the literature up to that date and later, by E. Schmid himself, in which he reports on that subject, showing cases of real maxillary advancement. I worked for him for several months in 1954 and before, and I never saw him advancing a maxilla. I have, however, learned a lot

from him. I consider him to be one of my very important teachers. He was very innovative.

It seems astonishing that a clear working procedure had never been developed for advancement of the retrodisplaced maxilla, in spite of the fact that many surgeons had seen the need for it and had tried to do it. g. Axhausen (1934, 1936a,b, 1939) seems to have been the only surgeon who has frequently shown results of the repositioning of the maxilla after its mobilization, however, by the use of elastics. For some reason his technique also did not come into use.

When I lectured on the full mobilization of the maxilla at a postgraduate course at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C. in June 1966, not one of the over 500 participating surgeons seemed to have ever done or seen it done.

In 1969 I visited my good friend Ralph Millard in Miami, for almost a week. A few days before, I had just presented the previously mentioned paper on "Surgical Correction of Deformities of the Jaws in Adult Cleft Cases" at the First International Conference on Cleft Lip and Palate, at Houston. My colleague and friend from Erlangen, Gerhard Steinhard, was also there for some days. Ralph asked us to present a paper to his staff. G. Steinhard's paper (1969) on spontaneous regeneration of large mandibular defects after subperiosteal resection in animals and patients was very impressive. I presented the same paper that I had given at the Houston meeting. Almost all of his staff and trainees did not agree with our philosophy regarding the need for dual qualification for the work we were doing.

Then we were asked to give our opinion on some trauma cases which had been treated by them. Our philosophy of facial fracture treatment was different to theirs. One case presented to us was treated 1 year before, but he still had a retrodisplaced maxilla, including one zygoma. The horizontal occlusal gap was about 10 mm. Our suggestions for correcting that situation were invited. The answer was simple: bring forward surgically what the trauma had displaced. They wanted me to demonstrate it to them as they would not be able to do it. As mobilizing the zygoma is quite difficult without proper instruments I suggested I would do the maxillary osteotomy and bring it into proper occlusion and they should then deal with the depressed zygoma if this was still requested by the patient. They agreed. Days went by. At the end of that week I had to leave at noon for the airport. Nothing had happened. On the last day of my visit at 10.30 a.m. I was watching Ralph Millard performing his technique of face lifting when someone asked me to do that case straight away. I asked them to prepare the necessary wire splints on the teeth and take some cancellous bone from the iliac crest for grafting behind the tuberosities and in both canine fossae. They worked hard in two teams, one in the mouth and the other on the hip. At 11.00 A.M. I was asked to come to the

21.3 Steps in the Development of the LeFort 1-Type Standard Operation Technique 387

operating room again. The wire splints on the upper and lower teeth were not finished and the piece of bone taken from the iliac crest was waved proudly in the air by an ambitious young surgeon. But it was just enough for one side! He had to reopen the donor site on the hip and take another piece of bone and the team working in the patient's mouth also still needed another 20 min to finish the splint. It was almost 11.30 a.m. when I was able to step in and start, with everything else except a bone cutting machine and instruments to which I was accustomed. It was a bit of a "rough operation". Within 15 min, the maxilla had become so mobile that I could overcorrect it with a pair of tweezers. I did the intermaxillary fixation and asked them to do the bone grafting for me as I had to leave for the airport. The young surgeons were obviously pleased and thanked me. Dr. Ben Hur from Israel, one of the trainees, apologized that he had attacked us so vehemently, disagreeing with the necessity for dual qualification for maxillofacial surgery. He said, he was now convinced.

One year later I was there again for a short visit. The case was shown to me. He had a perfect occlusion and mouth opening. But he had a fistula in the back of his upper vestibulum discharging a little pus. I was asked why was this the case. With a probe I could follow the fistula behind the tuberosity area. No cause was possible in my opinion other than an overlooked piece of gauze. The following day it was found and removed.

Summarizing, I dare to state that around 1960, neither in Europe nor in the USA, did there exist a clear procedure for mobilizing the maxilla in such a way that it could be placed wherever needed. But there was definitely a need for a standard procedure which enabled the safe mobilization of the maxilla for the correction of its anomalies of whatever origin. It was a challenge to find also a procedure for correcting most of the abnormal positions and forms of the maxilla, after the sagittal splitting procedure on the mandibular rami and the

chin sliding procedure had introduced the possibility to correct most of the common mandibular anomalies. Following my principle "A necessity can neither be forbidden nor be eliminated by ignoring it" (Principle No. 37), I started to work on it.

21.3 Steps in the Development of the Le Fort 1-Type Standard Operation Technique

In the "late fifties", when I was already working at Zurich University, I had to deal with post-traumatic retromaxillism in several cases. I was of the opinion that what the trauma can push backwards I must be able to bring forwards. In order to secure as much blood supply as possible to the maxilla, I wanted to leave the vestibular mucosa attached to it. From vertical incisions in the midline and behind the canine and in the molar regions, I raised the mucoperiosteum, sectioned the anterior surface of the maxilla with Lindemann burs (Fig. 88a) and detached the nasal septum after I had elevated the nasal mucosa. For that I had the forked-type nasal septum osteotome made. I also cut the pterygoid plates horizontally, using an osteotome, as the trauma had also fractured them. For the mobilization itself, I used a pair of Rowe's disimpaction forceps. When it seemed to be loose enough, I pulled the maxilla with wires into the planned occlusion. After 4 weeks intermaxillary fixation a certain amount of relapse occurred again. I did not know why. In the next case I did the same and again got some relapse. It then occurred to me that it was due to the backward pull of the pterygoid musculature. In the following case I separated the tuberosity area from the pterygoid plates and again performed a proper mobilization. I obtained a good occlusal result in that case (Fig. 88b ).

After these simple LeFort 1-type post-traumatic cases, we had an open bite case which, according to the occlusion, was also post-traumatic but not as a 1- piece fracture. It was my first case involving cutting the maxilla into two unequal pieces for repositioning them upwards in the posterior regions (Fig. 88c).

Fig. 88a, b. The development of the LeFort 1-type mobilization. a Vertical vestibular mucosal flaps for securing blood supply to the mobilized maxilla. b First successful case of mobilization of the maxilla in a late post-traumatic situation, for correction of its retrodisplacement (from H. Obwegeser 1962)

388 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort 1-Type Mobilization Procedure

That experience I then used for the correction of a collapsed and retrodisplaced maxilla in an unilateral cleft case. Somehow it was very difficult to mobilize the maxilla. I was glad that there was a vestibular blood supply as the palatal mucosa looked badly damaged by the use of the disimpaction forceps. After I had reopened the cleft, I could swing the fragments nicely laterally. But the mobilization and the advancement was not really complete. After 6 weeks intermaxillary fixation the result was not bad, but also not perfect (Fig. 88d).

The number of cases seeking improvement of their dish-face deformity due to retromaxillism increased. Particularly the cleft cases, with collapse of two or even three segments of the severely retrodisplaced maxilla,

were a challenge. With the vertical vestibular mucosal flaps securing the blood supply to the maxillary segments in unilateral cleft cases, it was still difficult to mobilize the maxillary segments well enough after the cleft had been reopened. I did not dare to cut the vestibular mucosa horizontally. I was frightened to interfere too much with the palatal blood supply when advancing the maxillary segments by 10 mm and more. I had watched Sir Harold Gillies using horizontal vestibular incisions when I trained with him in 1951/52. But he only rotated the segments laterally and I never saw him advancing these segments. He fixed them in the new position with the help of cast cap splints which were attached via a vertical bar to a head cap. Once he had stabilized the ro-

Fig. 88c, d. The development of the Le For t 1-type mobilization. c First case of mobilization and sectioning the maxilla into two pieces for closure of a post-traumatic open bite (from H. Obwegeser 1964). d First unilateral cleft case in which the maxilla was sectioned into two pieces and advanced for correction of severe retromaxillism together with collapse of the dental arch (from H. Obwegeser 1965)

21.3 Steps in the Development of the LeFort I-Type Standard Operation Technique 389

Fig. 88e-g. The development of the LeFort I-type mobilization. e-g Very severe retromaxillism in a bilateral cleft deformity case, corrected by swinging the two main segments laterally and the front segment forwards and correcting the sagittal discrepancy with a mandibular set back operation. Additionally, the lip was reoperated on and simultaneously the columella was elongated by the use of Millard's forked flap technique (from H. Obwegeser 1966)

tated segments he placed cancellous bone grafts on the steps in the canine fossa, leaving them in wide open communication with the maxillary sinuses. He then mobilized the vestibular mucosa and covered the bone grafts with it on the vestibular side only. The horizontal discrepancy he corrected by retropositioning the mandible. I also did this in very severe dish-face deformity cases which were due to a collapse of all three maxillary segments in bilateral clefts (Fig. 88e-g) if I was unable to advance them far enough. The vertical vestibular mucosal flaps limited the amount of advancement of the maxillary segments.

21.3.1 The All-Decisive Case

Then the all-decisive case turned up. It forced me to change my approach. The patient was a young man, the

18-year-old son of a famous Swiss family, who was referred by the chief of plastic surgery of the University Hospital. In a car accident, 6 weeks earlier, he had lost three upper incisors and suffered an open bite, due to an untreated telescoping Le Fort !-fracture in two pieces. So far, I had always used vertical vestibular incisions leaving mucosal bridging flaps attached to the maxilla. In this post-traumatic case the maxilla was not only split into equal halves but also retrodisplaced and telescoped into the nasal and maxillary sinuses, producing not only a retromaxillism condition but also a severe open bite in the anterior region (Fig. 89a). Additionally there were several communications between the oral cavity and the nose (Fig. 89b). The three upper incisors were missing. In the vestibulum on both sides, a scar ran as far back as the zygomatic crest. The model operation proved that a perfect occlusion in the cheek teeth regions could be achieved when the maxilla was mobi-

390 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort I· Type Mobilization Procedure

lized and cut into two pieces (Fig. 89c). Because of the scars in the vestibulum, there was no chance of leaving vestibular mucosal flaps attached to the maxilla to ensure a safe blood supply. Because of that vestibular scar I made an incision from one zygomatic crest, through the oro-nasal fistulae, over to the other zygomatic crest. I removed the scar tissue in the former fracture lines. As the two halves were telescoped into the maxillary sinuses I had to free them there and perform osteotomies from the canine fossae over the zygomatic crests posteriorly. I carefully observed the bleeding of the fragments during the vestibular osteotomies which were accomplished by the use of osteotomes and thin fissure-type burs. It remained satisfactory. Then I raised the nasal mucosa all the way back along the nasal floor and the lower part of the septum. The bleeding of the maxilla still remained satisfactory. Next, I detached the septum from the hard palate with the forked nasal septum osteotome and cut the lateral nasal walls below the inferior nasal conchae. The blood supply still remained satisfactory. Next, I separated the maxilla from the pterygoid plates using a slightly curved, rather strong osteotome. For mobilizing the maxilla I did not dare to use the disimpaction forceps for fear of damaging the palatal blood supply as there were some post-traumatic scars. Instead I pushed the maxilla in the front region inferiorly. This was later called the downfracture technique when I did it routinely in all the subsequent cases and demonstrated it to many visitors. With the strong, slightly curved osteotome I tried to pull the maxilla gently forwards on each side.

Naturally, I was frightened to interfere with the blood supply as in the literature all surgeons who had split the

maxilla in two halves and rotated them inferiorly and laterally had stated that the descending palatine artery must remain intact for the necessary blood supply to each half of the maxilla. It worked and the blood supply became poor but recovered after a while. I had to separate the two halves of the maxilla in the palate also, in order to be able to place them independently into proper occlusion (Fig. 89d). Direct bone wires were used to secure the two halves of the maxilla in the correct position. The blood supply to the two halves of the maxilla remained satisfactory. The oro-nasal communications could be closed after some mobilization of the vestibular mucosa and also the palatal opening between the two halves of the maxilla could be closed simultaneously. The occlusion achieved (Fig. 89e) was equivalent to that before the accident.

This case demonstrated that the maxilla receives an adequate blood supply from the palate even when it is mobilized. It does not need any blood supply from the vestibular, nasal or antral mucosa. A large advance in the technique of mobilizing the maxilla was achieved. This was the actual "birthday" of today's LeFort !-type mobilization procedure. It was in 1964.

However, knowledge concerning the development of the Le Fort I-type osteotomy procedure was not finished. I still had to learn to deal with the most severely retrodisplaced, collapsed maxillae of unilateral or bilateral cleft patients. I had also to learn how to overcome the tendency to relapse in these cases. The majority of cases badly needing an advancement of the maxilla were cases of secondary cleft deformity. In addition to the advancement they also needed an increase in maxillary height as their cleft maxillary segments were not

Fig. 89a-e. First case of advancement of the maxilla in two segments in spite of horizontal vestibular incisions (from H. Obwegeser 1967). a Severe open bite in the front region due to a post-traumatic telescoping retromaxiliism in two segments. b Oro-nasal communication and vestibular scarring on both sides. c Model operation. d The completely mobilized two halves of the maxilla. e Occlusion achieved

21.3 Steps in the Development of the Le Fort 1-Type Standard Operation Technique 391

only collapsed and too far back but they also had a severe lack of downward growth. In most of them their mandible was in a normal position but their prognathic appearance differed very much, depending on the degree of retromaxillism.

21.3.2 The Final Step: Bone Grafts to the Osteotomy Defects

Then a very severe unilateral cleft deformity case was referred to me. The maxilla was slightly collapsed and far back while the mandible was in the normal position for a straightforward profile type (Fig. 90a, b). Occlusion was present in the molar regions only (Fig. 90c). The profile planning indicated that the mandible should remain untouched. The model planning showed that a forward movement of the maxilla was required by moving both segments independently, 15 mm on one side

and 13 mm on the other side (Fig. 90d). Because of the rather large steps in the canine fossa regions I planned to use bone grafts to bridge these defects and also between the pterygoid processes and the tuberosities. As the right infraorbital region was even flatter than the left I intended to place there also a piece of bone graft to improve the contour. The operation plan was to bring the two maxillary segments so far forward that the mandible could remain untouched (Fig. 90e).

The mucosal covering of the hard palate looked reasonable, but there was a rather long fistula between the small and the large segments. I used the circular vestibular incision learned from the previously mentioned post-traumatic case. The osteotomies in the canine fossae and in the lateral nasal walls were performed using a Lindemann bur after the nasal mucosa had been elevated and protected. The separation of the maxilla from the pterygoid process was done as in the previous cases and so was the detachment of the nasal septum from its crest.

Fig. 90a-d. First case of correction of retromaxillism of 1 5 mm in a unilateral cleft deformity (from H. Obwegeser 1969). a, b Patient's presurgical profile view and lateral cephalogram disclosing severe retromaxillism with dish-face deformity and typical cleft humpy nose. c Presurgically there was occlusion i n the molar regions only. d The model operation showed that the two maxillary segments had to be moved forwards independently

392 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort Hype Mobilization Procedure

There was enormous resistance to the mobilization of the maxilla in spite of the strong force I used. Then I opened the cleft again, rotated the two halves laterally. Now I could feel with a finger where the scars were which had prevented the advancement of the maxilla. I cut them carefully. Finally, I got both segments absolutely loose and far enough forwards with their blood supply still satisfactory. The distance between the tuberosity and the pterygoid process measured 15 mm on the side of the lesser segment as determined in the model operation. Due to the lateral rotation of the two halves there was also a large step in the canine fossa and in addition a bit of a vertical defect, as both segments also had to be rotated downwards. It was obvious that these bone gaps had to be filled with bone. I used blocks of cancellous bone from the iliac crest, 15 mm long behind the small segment and 13 mm long behind the major segment. For

the horizontal and vertical defects in the canine fossa, the bone pieces were cut accordingly and fixed with wires. After mobilization of the vestibular mucosa the bone grafts could be covered on the vestibular side. But they stayed in wide open communication with the maxillary sinus and the nasal cavity. The postoperative course was uneventful. Aesthetically and occlusally the result was very satisfying (Fig. 90f,g). The unilateral cleft remained open. It had to be closed in a separate operation later, using local tissue and bone grafting.

With this case, the technique for advancing the maxilla had become a safe standard procedure (H. Obwegeser 1962, 1964, 1965, 1966a, 1967a, b). The bone grafting to the open maxillary sinus I had seen when I trained with Sir Harold Gillies in 1951/1952. He swung the two segments laterally producing a greenstick fracture at the pterygo-maxillary junction as did E. Schmid accord-

Fig. 90e-g. First case of correction of retromaxillism of 15 mm in a unilateral cleft deformity (from H. Obwegeser 1969). e Diagrammatic illustration of the planned operation. f, g Patient's profile view and lateral cephalogram 1 year after surgery. The humpy nose was automatically corrected just by the advancement of the maxilla. The large bone block behind the maxilla is easily detectable on the lateral cephalogram

21.3 Steps in the Development of the Le Fort I· Type Standard Operation Technique 393

ing toW. Widmaier (1960). Later, there were also cleft and non cleft cases in which I had to move the maxilla forwards by up to 20 mm.

21.3.3 Closing the Defect of a Missing Tooth

In almost all cases of cleft maxillary advancement, the cleft had to be reopened to permit the achievement of an acceptable occlusion. The reopened cleft had to be closed again in a second operation. Later, I closed the alveolar cleft in unilateral cases simultaneously by advancing the small segment with its teeth into direct

b

tooth contact with the main segment. This meant that the canine tooth was brought into contact with the first incisor of the major fragment or even its first bicuspid with the second incisor (Fig. 9la-f).

21.3.4 Deep Frozen Bank Bone in Maxillary Advancement

In many cases in which I had to advance the maxilla between 5-10 mm only, I routinely used deep-frozen human cadaver cancellous bone with excellent results. I placed it behind the advanced maxilla and at the step in

Fig. 91 a-d. Simultaneous advancement of the two segments of a cleft maxilla and closing the gap of a missing second incisor (from Obwegeser 1988). a Model operation indicating that a very acceptable occlusion can be achieved when both segments of the maxilla are advanced and rotated together. b Diagrammatic illustration of planned procedure. c, d Occlusion before and 1 1/z years after surgery

394 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort 1-Type Mobilization Procedure

Fig. 91 e, f. Simultaneous advancement of the two segments of a cleft maxilla and closing the gap of a missing second incisor (from Obwegeser 1988).e, f Patient's pre- and postsurgical appearance

the canine fossa. In cases requiring more than 10 mm advancement, it did not produce bony union. In those cases I then used the patient's own cancellous bone

21.4 First Case of Simultaneous Advancement of the Maxilla and Repositioning of the Mandible

Then a case turned up with such a severe horizontal discrepancy between the two dental arches and the middle and lower facial thirds that neither with a maxillary advancement alone nor with a mandibular set back operation alone could the facial disfigurement be corrected properly as well as the planned occlusion achieved. This situation was found in both non-cleft and cleft cases. Formerly I had tried to improve the aesthetic as well as the occlusal situation by retropositioning the mandible only. The achieved occlusion was acceptable but not so the aesthetic result. I also had experienced that there is some limitation to pushing the mandible backwards by the sagittal splitting procedure. It had become unavoidable that in these cases the maxilla had to be advanced as well as the mandible retropositioned. I decided to do this in one operation. It was performed on 5 September 1969.

The main indication in the first patient to have repositioning of the mandible and advancement of the maxilla in one operation was his severe micro- and retromaxillism, well recognizable in the appearance (Fig. 92a) as well as in the lateral cephalogram (Fig. 92c). The occlusion was that of a severe bilateral class III relationship (Fig. 92b). As a consequence of the severe mi-

wedged in between the tuberosity area and the pterygoid plates and the canine fossa step (H. Obwegeser 1969b,c).

cromaxillism, there was a large distance between the upper and lower teeth when the patient's mandible was in its resting position (see Fig. 92c).

The occlusion result would always be the same, whether the mandible or the maxilla alone were moved or both simultaneously (Fig. 92d). The necessary amount of vertical height increase of the maxilla could be measured on the lateral cephalogram, taken in the resting position of the mandible (see Fig. 92c). In order to find out the amount of repositioning of the maxilla and the mandible in the sagittal dimension that would be ideal for the final result, the desired profile line was drawn on a transparent sheet over the existing profile line. The sagittal difference of the two gave an idea of the necessary amount of sagittal movement of the two jaws. I planned to make the final decision on the operating table.

The necessary amount of maxillary advancement and the additional necessity to increase the vertical height of that very small maxilla made it clear that I had to add bone in the canine fossa as well as behind the maxilla. The bone grafts for the canine fossa had to be shaped like a step in order to secure the necessary

21.4 First Case of Simultaneous Advancement of the Maxilla and Repositioning of the Mandible 395

Fig. 92a-d. First case of simultaneous advancement of the maxilla and retropositioning of the mandible for correction of a very severe sagittal discrepancy (from H. Obwegeser 1970). a, b Patient's appearance and occlusion before surgery. c Lateral cephalograms, before surgery in the closed and mandibular resting position and l ' /,years after surgery. d Model operation demonstrating that the occlusion will always be the same whether the maxilla or the mandible alone or both are repositioned

amount of vertical height increase of the maxilla as well as to reduce the flatness in the canine fossa region (Fig. 92e).

A continuous loop wiring splint was fixed to the teeth to secure the planned occlusion for 6 weeks with intermaxillary fixation. During surgery there were no real problems. When both jaws were completely mobile I fixed them together. Now I could move the jaws as one firm block. I fixed this provisionally in position according to my imagination and checked the patient's appearance. As I found it satisfactory I then completed the operation.

After 6 weeks both jaws were firm. The occlusion was as planned. There was not only full bony union, but due

to the bone grafting to the canine fossa, a welcome contouring of the face resulted. There was some over-contouring at the beginning but after 1 year the facial contour was just right (Fig. 92f) and so was the occlusion (Fig. 92g).

When it had become a routine procedure in my hands to reposition simultaneously the whole maxilla as well as the mandible (H. Obwegeser 1970) this was not only the solution for the correction of the very severe sagittal discrepancy of the two jaws but it also opened the door for modern corrective surgery of the lower half of the facial skeleton. Nowadays, many surgeons rarely do one jaw only, most do both at the same time, even if it is for 2- 3 mm repositioning only.

396 CHAPTER 21 The le Fort I· Type Mobilization Procedure

Fig. 92e-g. First case of simultaneous advancement of the maxilla and retropositioning of the mandible for correction of a very severe sagittal discrepancy (from H. Obwegeser 1970). e Schematic illustration of first case of simultaneous retropositioning of the mandible and advancement of the maxilla with additional increase in its height. f, g Patient's front view and occlusion 1 year after surgery

When I lectured on the "Surgical correction of Deformities of the Jaws in Adult Cleft Cases", at the First International Conference on Cleft Lip and Palate at Houston in 1969, I showed various types and degrees of secondary cleft deformities and their correction, including my first cleft case of simultaneous repositioning of the maxilla, even in sections, and the mandible. I was then asked whether I was such a bad primary cleft surgeon that I

21.5 Modifications and Further Progress

Just as modifications of the sagittal splitting procedure had been advocated, there were several modifications suggested for the Le Fort I-type osteotomy, mainly in

was producing such poor late results. However, I had seen such and also worse cleft deformities all over the world. They very much depended on the technique used and the radicalness of the primary cleft surgeon. But with this procedure of repositioning the maxilla and the mandible, as a whole or in sections, it was now possible to produce a normal facial skeletal framework out of a very distorted one (H. Obwegeser et al. 1978, 198Sa).

the antral wall area. Some osteotomies with steps, others descending or ascending or even curved.

21.5.1 Kutner's Extended Osteotomy of the Maxilla

In my opinion, the only one which brought additional improvement was J. Kufner's suggestion (1971) to include a part of the inferior orbital rim and zygoma (Fig. 93a). Quite a high percentage of cases, in particular the cleft cases, require a contour improvement higher up in the face than just at the base of the maxilla. Instead of performing that extended LeFort I -type osteotomy, I often camouflaged the flatness of the paranasal and infraorbital-zygoma area by inserting a piece of cancellous bone at the step in the canine fossa area. Or, I im-

21.5 Modifications and Further Progress 397

planted bilaterally an L-shaped piece oflyophilized cartilage paranasally (see Fig. 561), if there were no occlusal indications to advance the maxilla.

Because of the good results obtained in the correction of maxillo-mandibular disharmonies, other cases were referred which needed more than just repositioning of the maxilla and the mandible. There were cases which required an advancement of the full middle third of the face, some even including the forehead. Sir Harold Gillies had told me that he had tried to perform a Le Fort III advancement and warned me not to do it, as it was too hazardous. Nevertheless, I tried, again first in post-traumatic cases. When I related this in summer

Fig. 93a-e Extension of the LeFort I mobilization. a Kufner's procedure includes the infraorbital rims. b Diagrammatic illustration of simultaneous LeFort I and III mobilization for correction of severe dish-face deformity (from H. Obwegeser 1969). The procedure applied

in an 18-year-old patient with severe midface hypoplasia and syndactylism of the upper and lower extremities, of unknown origin (radiologically noM. Apert). c front view before, d 3 years and e II years after surgery

398 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort 1-Type Mobilization Procedure

1967 to Dr. J. Dautrey, a French visitor, he informed me that his chief, Dr. Paul Tessier in Paris, has produced a technique to advance the middle third of the face and also to correct hypertelorism. I met Dr. Paul Tessier in September 1967 in Rome at the International Plastic Surgery Congress. We became very good friends and I learned a lot from him, to the benefit of many patients. I consider him as my last real teacher.

21.5.2 The Lower Two Thirds of the Facial Skeleton

After P. Tessier (1967, 1968; P. Tessier et a!. 1967) had published his Le Fort III operation procedure and the correction of hypertelorism, the ultimate road towards the non-limited correction of cranio-maxillo-facial skeletal anomalies was opened. It was then obvious that in craniosynostosis cases, as well as in some ordinary cleft cases, in which the whole middle third of the face required advancement, the maxilla could be separated from the upper half of the middle third in order to reposition it, if necessary in two segments, according to the needs of the occlusion, and the upper half according to the needs of the orbits (H. Obwegeser 1969b,c, 1973b) (Fig. 93b-e).

While P. Tessier's Le Fort III and his hypertelorism procedure with their variations opened up the possibility of correcting any skeletal anomaly of the upper half of the facial skeleton, so did the sagittal splitting of the rami procedure and the Le Fort I mobilization together with the alveolar segmental corrective surgery (H. Obwegeser 1968) and the trans-oral chin correction enable us to correct even the most severe occlusal and skeletal configuration anomaly of the lower half of the facial skeleton.

When I had operated upon little Antonio with his two complete noses and a wide medial facial cleft the little 11-year-old boy had acquired quite a reasonably pleasing result (Fig. 94a, b) in spite of the fact that I had to remove the reconstruction of the defects of the lateral orbital walls due to massive infection. That infection also necessitated the neurosurgeon taking away the huge bone flap of the craniotomy (H. Obwegeser et al. 1978). When the boy had finally completed his general skeletal growth, a grotesque facial and occlusal picture had developed (Fig. 94c-e) due to my inexperience of what damage too early surgery can do to the middle third of the face. To correct this very severe facial skeletal and occlusal anomaly, I had formulated the following operation plan (Fig. 94f): Advancing the maxilla by an extended bilateral Kufner LeFort !-type mobilization and additionally separating the upper parts from the severely retroplaced maxilla for correction of the lack of vertical height. This should correct the severe dish-face deformity, apart from the missing nasal bridge. Simultaneously, a mandibular set back operation along with retropositioning of the lower anterior alveolar segment should create an acceptable intermaxillary relationship (Fig. 94g). For the reconstruction of the missing nasal bridge I planned to use an L-shaped piece of cartilage, as I had learned from E. Schmid (1956), simultaneously with the necessary elongation of the columella by a caterpillar flap (Fig. 94h). The nose turned out well (Fig. 94i).

Regrettably, in those days we still used infraorbital incisions to approach the orbits for the correction of the extremely severe hypertelorism. Otherwise the extremely severe facial and occlusal deformities were very satisfactorily corrected by altering the various parts of the lower two-thirds of the facial skeleton (Fig. 94j-l).

Fig. 94a, b. Very severe facial skeletal and occlusal anomaly after correction in childhood of a midfacial duplication and extreme hypertelorism (from H. Obwegeser eta!. 1978), a, b 11-year-old boy with facial duplication before and after correction

21.5 Modifications and Further Progress 399

Fig. 94c-f. Very severe facial skeletal and occlusal anomaly after correction in childhood of a midfacial duplication and ext reme hypertelorism (from H. Obwegeser et al. 1978). c Lateral cephalograms showing severe lack of growth of the patient's middle third within 6 years of correction. d, e Patient's front and profile views with extreme facial deformity at age 18. f Schematic illustration of planned correction of the patient's facial skeletal deformity

400 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort Hype Mobilization Procedure

Fig. 94g-l. Very severe facial skeletal and occlusal anomaly after correction in childhood of a midfacial duplication and extreme hypertelorism (from H. Obwegeser eta!. 1978). g Profile view of the result of the correction. h Reconstruction of the missing columella by a caterpillar flap and the missing nasal bridge by an L-shaped cartilage. i Patient's appearance in profile view 1 year after the last surgery. j, k Situation of the maxilla before surgery and the final result. I Lateral cephalograms before first correction and 1 year after the last surgery

21.5.3 The Whole Facial Skeleton

Using present day surgical procedures, it is possible to correct in one operating session, very severe craniomaxillofacial skeletal anomalies such as those seen in Apert's syndrome deformities. The skeletal anomalies in such cases can include all three thirds of the facial skeleton. It is worthwhile demonstrating such a case for discussion of some important points (Fig. 95).

The upper and middle thirds of the facial skeleton are usually much too far posterior in these cases. Apart from that, in most cases teleorbitism is present as well as a micro- and retromaxillism (Fig. 95a, b). The mandible is not directly involved in the craniostenosis. So, it can be of normal shape, or it can also show signs of some type of malformation, including a misregulation of growth anomaly.

The planning of the corrective surgery is done as usual, on tracings of the lateral cephalogram, to ascertain the necessary amount of forward movement of the forehead and the middle third of the face (Fig. 95c, d) and on model operations for the correction of the occlusion (Fig. 95e).

The craniotomy is planned in such a manner that not only allows the forehead to be moved anteriorly by the necessary amount, but the design also allows good fixation of the advanced and rotated orbits. Then the mid-facial complex is mobilized, the orbits together with the maxilla. This procedure, without separating the maxilla, is called the monobloc advancement of the upper two-thirds of the facial skeleton (F. Ortiz-Monasterio 1978).

In addition to that monobloc advancement, many craniostenosis cases require not only an independent

21.5 Modifications and Further Progress 401

amount of advancement of the orbits and the maxilla as shown in Fig. 93b, but also rotation of the orbits and reduction of their distance apart (Fig. 9Sf, g). For that the maxilla is then separated from the orbital cones and the desired occlusion with the mandible is confirmed.

In these cases the maxilla is often not only too far back but also so small that presurgical orthodontics requires extraction of several teeth on each side in order to be able to place the remaining teeth in correct angulation to the small maxillary base. The maxilla may be so small that on each side only four or five teeth can be left. If the teeth are orthodontically protruded, instead of achieving the necessary space by extractions, the orthodontist limits the surgeon's possibility of advancing the maxilla far enough forward (Fig. 9Sh,i).

Next, the surplus width of the nasal framework, together with the underlying ethmoid cells is reduced and then the orbits are rotated together and fixed in their new position. The osteotomies within the orbital cones should have been made far back in order to be able to rotate the orbital contents, also when the orbits are brought together. Next the maxilla is fixed to the mandible in the planned occlusion. Then the surgeon has to decide whether he can fix the maxilla directly to the united orbital cones or whether he has to interpose a bone graft on each side for correction of an existing vertical deficiency. After the maxilla is fixed to the upper half of the middle third of the facial skeleton, the intermaxillary fixation is released again and a canthopexy is done on both sides.

If the position or shape of the mandible must also be corrected, that will now be done according to the new position of the maxilla. Before closing the incision in the upper vestibular sulcus, the desired nasal correction is performed or a bridge augmentation is carried out.

Fig. 95a-c. Correction of the whole facial skeleton in a case of Apert's syndrome deformity. a, b Patient's front and profile view disclosing the very severe retroposition of the upper two facial thirds, accompanied by teleorbitism and additional hyper- and retrogenia. c The profile planning

402 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort 1-Type Mobilization Procedure

d

g

Fig. 95d- g. Correction of the whole facial skeleton in a case of Apert's syndrome deformity. d Evaluation of the amount of the necessary sagittal movement of the various facial skeletal parts. The upper half of the middle third has to be advanced by 20 mm. e The model operation indicates that for occlusal reasons the maxilla requires advancement by II mm. f, g Diagrammatic illustration of planned skeletal correction, monobloc advancement of the upper two-thirds of the face pius correction of the malposition of the orbits and independent advancement of the maxilla and correction of the retro- and hypergenia

21.5 Modifications and Further Progress 403

Fig. 95h-n. Legend see page 404

404 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort Hype Mobilization Procedure

The defects in the lateral and medial orbital walls as well as in the floor and roof of the orbital cones are reconstructed. Cranial bone can easily be obtained from the bone flap which was removed for gaining the necessary access to the anterior base of the skull. I am very fond of using split rib grafts. First, I take off most of the cortical covering of the rib with an acrylic bur and then I take off the rib edges with the same bur (Fig. 95j). Next, the rib is split with thin osteotomes or a strong knife. Finally the rib is bent as required by the use of bone-contouring forceps (Fig. 95k). The decorticated half of a rib can be formed and bent better than any other piece of bone. With this technique I have been able to reconstruct a skull defect the size of almost half of the skull (see Fig. 94c and 941).

Due to the amount of orbital advancement, a bilateral enophthalmos may result, as well as an unsightly de-

21.6 My Final Version of the Le Fort 1-Type Mobilization

Mobilization of the maxilla is now most probably more often performed than repositioning of the mandible. The technique may differ from one surgeon to another, although not very much. It has only changed slightly in my hands since 1970. In a straightforward case, the mobilization itself should not take much longer than 10-15 min.

Approaching the Maxilla

With the patient under naso-tracheal intubation anaesthesia, either the blood pressure is lowered, or a vasoconstrictor is injected into the vestibular incision and tuberosity areas. I perform the vestibular incision horizontally through the mucosa and then, in one cut, vertically to the alveolar process through the periosteum, about 5 mm above the attached mucosa, using a scalpel. Some prefer electrosurgery. The incision goes all the way around from one zygomatic crest to that on the other side. Where it ends, on top of the zygomatic crest, I direct the incision obliquely dorsally upwards for some millimetres to achieve enough access to the tuberosity area without elongating the incision by tearing it with the retractor. Then the mucoperiosteum is elevated up to the infraorbital nerve. I want to know where it is. In

Figure is on page 403

pression in both temporal areas (Fig. 951). These secondary defects can be reconstructed some months after the main operation. For the correction of the enophthalmos, I will again mobilize the orbital contents completely and place behind the equator of the eyeball enough very thin slices of lyophilized cartilage. They must be cut with the dermatome so thinly that the globe compresses them against the walls of the socket. It requires some experience to know what is the correct amount to produce a good result. If too much cartilage has been placed resulting in overcorrection, the surplus can easily be removed later as the cartilage slices remain as if they had just been placed. I also use the same material to fill the depression in the temporal areas. So, finally in two operations a very pleasing result can be achieved, from the aesthetic point of view as well as functionally (Fig. 95m,n).

the front it is raised above the nasal spine. On top of the zygomatic crest I incise the periosteum vertically for 5-8 mm. Next I make marks with a bur on the zygomatic crest and in the canine fossa. These will enable me to measure the amount of forward or backward movement of the maxilla. If the maxilla has to be raised I mark the amount of excision necessary on the antral wall. Next, the edge of the pyriform aperture is freed and the mucoperiosteal covering of the floor of the nose is raised on both sides along the whole length of the hard palate and on the lateral walls of the nasal cavities up to the inferior turbinates. On the medial aspect along the nasal crest of the palatine bones, elevating the muco-periosteum without tearing may present some difficulties. Care must be taken to prevent this from happening especially when approaching the juncture of the nasal crest of the palatine bones with the septum. Maintaining an intact muco-periosteum is even more important when a deviated septum is being corrected at the same time.

Separating the Maxilla

The periosteum is then carefully raised behind the zygomatic crest and into the pterygo-maxillary junction.

Fig. 95h-n. Correction of the whole facial skeleton in a case of Apers syndrome deformity. h Lateral cephalogram of another case of Apert's syndrome before presurgical orthodontics, the severe protrusion of the upper teeth makes it impossible for the surgeon to advance the maxilla by the amount necessary to produce a good facial appearance. i When the upper front teeth have been repositioned into proper angulation to the base of the maxilla by orthodontic means, additional advancement of the maxilla by 15 mm will be possible. j Preparation of a rib graft for splitting and bending. k Forming the decorticated half of a rib with the bone-contouring forceps for the reconstruction of the defects in the orbital walls. I After the 1-stage correction of the facial skeletal anomaly in accordance with the plan, a normal facial skeleton and intermaxillary relationship resulted, but with a rather severe bilateral enophthalmos and a concavity (depression) in the temporal regions due to the 20 mm advancement of the orbits. m, n Patient's fmal appearance 1 year after correction of the enophthalmos and the temporal depressions by subperiosteal implantation of thin slices of lyophilized cartilage

21.6 My Final Version of the LeFort 1-Type Moblllzatlon 405

'!,

c

Fig. 96a-e. My final version of the LeFort !-type mobilization. a Schematic drawing of the osteotomy lines for the LeFort T-type mobilization and its fixation with wires or plates and screws. b Strips of bone removed with the saw for correction a maxillary long face. c Thin, slightly curved osteotome for separating the junction between the maxilla and the pterygoid process. d The nasal septum osteotome in action. e The posterior downfracture of the maxilla with the bone separator

406 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort 1-Type Mobilization Procedure

If it is torn, Pichat's fat pad will come through the opening in the periosteum into the operation field. That annoying situation is best handled by excising what has come through and then covering the opening with a flat piece of gauze which is held by the retractor, which is now to be inserted. I prefer the upwardly bent retractor inserted at the junction between the maxilla and the pterygoid process.

I still use the same horizontal osteotomy for separating the maxilla as I did at the beginning when I started to use this procedure in non-trauma cases, occasionally varying it a bit from behind up, or downwards to the front region (Fig. 96a).

For the osteotomy of the walls of the maxillary sinus I like to use thin disposable blades in the reciprocating saw to cut the antral wall from posteriorly forwards including the lateral nasal wall, where a periosteal elevator prevents the mucosa being cut. Others prefer a bur and use an osteotome for the lateral nasal wall. I hate bone fragments in that area because of possible obstruction of the lacrimal duct and also possible postoperative nasal problems.

There are other reasons why I prefer to use a thin disposable blade in the saw to perform my osteotomy of the maxilla. With it, the loss of bone is negligible compared with the use of burs or even osteotomes. Also, I can direct the cut according to the planning, upwards or downwards; in addition I can remove exactly that strip and shape of bone which I need in my correction of a maxillary long face (Fig. 96b ).

Next the pterygo-maxillary junction is separated using a very thin, slightly curved and slightly flexible osteotome (Fig. 96c). The posterior antral wall is cut with the saw with that osteotome in place.

The nasal septum is now detached from the hard palate using the forked septal osteotome (Fig. 96d). For safety reasons, the posterior pharyngeal wall may be protected from the forked septal osteotome being driven into it by packing the epipharynx with a large strip of gauze. The latter should not be forgotten! For that reason a black thread is fixed to it, emerging through the mouth. This packing is removed before the end of the operation and definitely before intermaxillary fixation.

The Actual Mobilization of the Maxilla

When all bony connections of the maxilla to the higher bones are cut, now comes the mobilization. For quite some time now I have ceased commencing with the frontal down fracture. I learned from my nephew J. Obwegeser to bring the maxilla inferiorly first in the posterior part. To do this, I insert the narrower bone separator from the zygomatic crest further posteriorly and open it gently. The maxilla comes down easily (Fig. 96e). Then the front part is lowered, again with the bone separator inserted at the nasal aperture rim. This is the reverse of my previous procedure. This ensures that the maxilla is really freed from the pterygoid processes.

To advance the maxilla and complete the mobilization further, I no longer use the so-called maxillary mobilizer type elevator (Fig. 96f). The necessary force is not always that easy to control and I am also not in favour of using Tessier's maxilla mobilizers also because of the possibility of applying too much uncontrolled force. I had an instrument made by the Medicon Company which I called a "maxillary advancer" (see Fig. 102d). With one leg resting on the zygoma, the other

Fig. 96f,g. My final version of the LeFort !-type mobilization. f Mobilization of the maxilla with the surgeon's hand power. g Mobilization of the maxilla with the maxillary advancer

part, a type of "shovel", is inserted behind the tuberosity. That part can now be moved anteriorly millimetre by millimetre (Fig. 96g). After one side is done the next is dealt with in the same way. With the maxillary advancer one can move the maxilla anteriorly by more than 20 mm. One should not do as much as that on one side only, but go over to the other side after 10 mm or so of advancement. The maxilla must be so loose that it can be easily overcorrected with a pair of tweezers. It is a "must" (Fig. 96h).

Particularly in cleft cases, great resistance against the complete mobilization may be experienced. The palpating finger can identify where the knife or the scissors has to cut some still-resisting scars. It is better to cut them than to pull so hard with the maxillary advancer that they come loose. Scars do not include large vessels. So there is no risk of severe bleeding when cutting.

The maxillary advancer is also a very useful instrument for pulling the middle third of the facial skeleton forwards in aLe Fort III-advancement procedure.

21.6.1 Narrowing and Widening the Maxilla

Narrowing a too wide maxillary arch is not a difficult task: when the maxilla is loosened it can be approached from above. The necessary size of bone strip is removed with a bur from above, along or adjacent to the midline of the palate. The defect ends in the front between the two first incisors, or wherever planned.

21.6 My Final Version of the LeFort I· Type Mobilization 407

Widening the maxilla is more delicate, at least depending on the amount necessary. For 2-3 mm only it can also be done from above (Fig. 96i). But if a widening of 3-5 mm on each side is required then the covering mucosa on the palate does not allow that much. In such a case I do it from below. I incise the palatal mucosal covering in the midline, diverging the incision from the papilla towards the lateral interdental spaces of the first incisors. The palatal mucosa is raised laterally, rather close to the sulcus of the palatine artery (Fig. 96j). The hard palate is cut from behind towards the interdental space of the two first incisors. A thin alveolar osteotome is used to split the alveolus in the front region while a flat twisting osteotome opens the two palatal defects. They should be filled with bone before the palatal flaps are resutured or held against the hard palate by a vaseline gauze pack. That gauze is held in place by a second plain gauze pad that has been moistened with acetone cement and fixed to the teeth with circumdental sutures that may extend across the palatal area on top of the gauze.

In such a case the maxilla must be freed all the way around, including from the pterygoid processes, but the nasal septum must not be detached and the maxilla therefore not mobilized, only widened. If the usual osteotomy along the hard palate were to be performed, that middle piece of palate would become necrotic because of lack of blood supply, as the nasal floor mucosa has to be raised for that osteotomy.

Fig. 96h-j. My final version of the LeFort !-type mobilization. h The maxilla must be that loose that it c an be overcorrected with a pair of tweezers. i Widening the maxillary arch from above when the maxilla is mobilized. j Widening the maxilla from below when a large amount of widening is necessary

408 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort 1-Type Mobilization Procedure

21.6.2 Mobilizing and Repositioning the Maxilla in Sections (Fig. 97)

In some cases, in particular those in which presurgical orthodontics is not available, the maxilla must be mobilized and repositioned in sections in order to achieve the desired occlusal and aesthetic result. This is especially the case when the number of teeth present cannot be arranged into proper angulation to the respective base of the jaw without extractions. Mostly the front teeth are protruding and therefore require repositioning independent of the lateral parts of the maxilla. In these cases, a triangular ostectomy in the area of the necessary tooth extractions has to be performed with removal of a connecting strip of bone from the hard palate. That requires mobilization of the palatal mucosa from the front backwards, including the area of the connecting strip of bone which has to be excised. That means that for that frontal segment of the maxilla no palatal blood supply would remain. For this reason we must secure the vestibular blood supply to that anterior segment, exactly as in the operation procedure for correction of a maxillary protrusion situation only (S. Wunderer 1962).

The procedure is carried out as follows (Fig. 97a- e): the vestibular muco-periosteum has to be raised in the area of the horizontal osteotomy from the pyriform aperture back to the region where the wedge-shaped bone excision in the alveolus has to be performed. This undermining starts from an incision in the labial frenu-

lum and ends at a vertical incision in the vestibular mucosa where the bone excision in the alveolus, with or without extraction of a tooth, will be placed. From that medial incision in the vestibular mucosa the anterior nasal spine will be fractured or removed for better access to the nasal crest of the palatine bones and for easier elevation of the mucosa of the nasal floor. That anterior segment of the maxilla becomes free to be placed as planned, when the horizontal osteotomy at the anterior surface of the maxilla is done, the wedge-shaped bone is excised from the alveolus and the connecting bone strip on the palate is removed as well, after separating the attached portion of the nasal septum from the palate. If protruded teeth have to come into proper angulation, the freely movable anterior segment of the maxilla has to be raised in its posterior region. That requires gaining the necessary space by additional excision of the nasal septum or the nasal crest and of the posterior part of the horizontal osteotomy in the canine fossa.

In cases with a gothic-type dental arch, the mobile frontal segment has to be additionally split. This is performed from the palatal side where the raised palatal mucosa gives good access for doing this.

In addition to the freely movable anterior segment of the maxilla, the remaining posterior part of the maxilla may also need some widening or narrowing. This is achieved after that part of the maxilla has also been made completely free. If the necessary correction in transverse width is only minimal, it is achieved by cutting the remaining hard palate from above after it is

Fig. 97a. Mobilizing and repositioning the maxilla in sections for correction of dish-face deformity due to micro- and retromaxillism with anterior protrusion and lack of width of the maxilla. a Schematic illustration of the procedure for correcting the anomaly of the maxilla

21.6 My Final Version of the LeFort 1-Type Mobilization 409

Fig. 97b-e. Mobilizing and repositioning the maxilla in sections for correction of dish-face deformity due to micro- and retromaxillism with anterior protrusion and lack of width of the maxilla. b Schematic illustration of the planned operation including reconstruction of the missing cartilaginous support of the nose by the use of an L-shaped piece of rib cartilage. c Tracings of the lateral pre- and postoperative cephalograms demonstrating clearly the result of the correction of the protruded upper front teeth and the retrodisplaced maxilla. d, e. Mobilizing and repositioning the maxilla in sections for correction of dish-face deformity due to micro- and retromaxillism with anterior protrusion and lack of width of the maxilla. d, e Patient's profile view before and I ' /z years after the correction

410 CHAPTER 21 The le Fort I-Type Mobilization Procedure

completely mobile. If a substantial widening is required the procedure shown in Fig. 96j will have to be applied, leaving the central part of the hard palate of that posterior half of the maxilla connected to the nasal septum and its mucosal covering. All four maxillary fragments are fixed together by a wire splint and, if prepared, with an additional occlusal splint or by mini plates and screws.

Mobilizing and repositioning the maxilla in sections can help to overcome the existing difficulties in producing a nice occlusal and aesthetic result.

21.6.3 Advantages for the Nose

The completely mobile maxilla offers the possibility of investigating the nasal cavity carefully. It is now easy to remove the often almost rectangularly bent nasal crest of the palatine bones. Particularly in cleft cases, it is often impairing the free airway in the inferior nasal choanae. Its complete removal during an ordinary approach for a nasal correction is often very difficult, rarely without causing severe damage to its covering nasal mucosa. It is much easier to free the periosteum including the mucosa from that irregularly formed piece of bone using the advantage of the access to the floor of the nose during aLe FortI-type operation. This bone is exposed when freeing the nasal floor from its muco-periosteal covering and before that crest is cut with the forked septal osteotome (Fig. 98a).

Now, when the maxilla is mobile, there is the chance to see all details in that nasal cavity, with a good head light. Of particular importance is its floor, as bone fragments or severely damaged mucosa etc., need to be removed.

This access also permits very easy correction of a commonly occurring septal deviation. The septal cartilage is freed without any difficulty from its covering perichondrium including the mucosa (Fig. 98b) . Any type of correction of a septal deviation is now done without difficulty. I correct its deviation by the use of the septal cutter (see Fig. 102e). Direct vision helps a lot in doing this.

The inferior turbinates also now deserve special attention. They can easily be reduced in size when necessary. In cases of correction of a maxillary long face, when the maxilla has to be positioned higher, these turbinates may block the inferior nasal airway almost completely when the mobilized maxilla is fixed in a higher position than it was before. The reduction in the turbinate's size is simple: a triangular piece of its inferior rim is cut out all the way back, preferably using diathermy. The defect should be closed with a resorbable suturing material. It is not advisable to reduce the turbinate's size with cutting diathermy without suturing. In the event of damage to the nasal mucosa, such a turbinate may become adherent to the floor of the nose and block the airway. Occasionally, although rarely, the turbinate including its bony part is resected.

Fixation of the Mobilized Maxilla

Next comes the fixation of the maxilla in the planned occlusion, followed by its osteosynthesis. Nowadays, plates are used by most surgeons. I am fond of screws or plates for the split mandible but not for the maxilla. By experience, I have learned that in almost 100% of the cases we will have a perfect occlusion after removal of

Fig. 98a, b. Correction of nasal septum pathology. The possible necessity for the correction of a septal cartilage deviation a and removal of the nasal crest of the palatine bones b should be evaluated in every LeFort I-type mobilization. It is an easy task once the maxilla is mobile

the intermaxillary fixation as long as the patient was under general anaesthesia. But when fully awake and closing the mouth according to the muscular function, almost SO% showed a slight change in occlusion. This is also true for the mandible. With plates for osteosynthesis that is difficult to correct. Some surgeons leave them loose purposely. I prefer a pair of 0.4 mm wires on each side, one at the piriform aperture and one at the zygomatic crest, not tied too tightly. It will also produce bony union within 4-6 weeks, better without than with, intermaxillary fixation. The latter can prevent it and result in a pseudoarthrosis of the maxilla. But when necessary these wires permit postoperative correction of the occlusion by the insertion of elastics fixed to brackets on the teeth or the wire splints. For the mandible, there is no chance for such a postoperative correction of the occlusion if plates or screws have been used to fu the split mandible together.

Bone Grafting to the Osteotomy Lines

In cases in which bone grafting is needed in the canine fossa areas I will use three wires on each side which will prevent the bone graft from dropping into the maxillary sinus and from moving about.

For many years I used deep-frozen cancellous bank bone obtained from fresh cadavers. That worked nicely as long as the step or gap in the canine fossa was not more than 10 mm. Otherwise, the iliac crest is used to obtain the amount of cancellous bone required. For obtaining and preparing deep-frozen bank bone see Chap. 26.4.

The indications for using bone grafting in a case of LeFort I-type mobilization vary, depending on whether or not enough bone contacts between the mobile maxilla and the upper osteotomy line exist without a bone graft and also on the size of the horizontal step or gap in the canine fossa. That defect may finally be bridged by scar tissue or a thin layer of spontaneously regenerated bone. In any case it will result in a flatness in that area, more so than it did preoperatively, when that gap was more than 8-10 mm.

Taking a bone graft is, of course, a disadvantage for both the patient and the surgeon. But the bone graft has the great advantage that it produces a nice contour, contrary to the otherwise flat-remaining paranasal-canine fossa region.

I also see the need for bone grafting when we have to produce a vertical gap in the canine fossa for the correction of a vertical maxillary deficiency (see Fig. 92e). In all cases of bone grafting to the canine fossa area, I also wedge a piece of bone into the empty space between the advanced tuberosity and the pterygoid process. There it does not need any fixation, but it fills the empty space, stabilizing the maxilla additionally.

21.6 My Final Version of the LeFort Hype Mobilization 411

21.6.4 Simultaneous Nasal Correction

The individual case may not only require maxillary repositioning but also nasal correction. It is more logical that minor or major nasal corrections be carried out during the same operating session, although never without the patient's presurgical agreement.

Once the maxilla is fixed in its new position then there will never again be an easier approach to the nose. The nasal crest of the palatine bones was removed while the maxilla was still mobile. Now the surgeon's favourite approach for nose correction is used and executed with the advantage that now the lateral nasal wall osteotomies can be performed under direct vision, using a rotating bur or a saw or even a nasal osteotome. The access to the nasal bridge and tip is the same as usually used by the surgeon. For smoothing uneven spots on the bridge I am very fond of the perforated nasal rasps as they cannot clog (see Fig. 102f). If there was also a septal deviation, that will have to be dealt with after the bony bridge and the work on the nasal tip is finished and before the vestibular incision is closed.

Finishing the Operation

The wound closure in the vestibulum of the maxilla is done with partially everted continuous suturing. I prefer a monofilament non-resorbable thread as I do not want the suture material to carry the mouth flora into the operation field. My favourite suture material for use within the mouth is Supramid.

The last step in the operation is to put a folded, rather small, soft rubber tube into the inferior nasal airways. This has the purpose of adapting the mobilized mucosa to the floor and lateral wall of the nose and also presses it gently against the nasal septum. In the case where a correction of a septal deviation has also to be performed, these soft tubes, in both sides of the nose, will guarantee that the cut septal cartilage will not swing to one or other side or become deviated again. I may change them after a day or two in order to get rid of the blood clots and then I leave them in place generally for 8-10 days in cases in which a septal deviation was corrected. It is essential to prevent these tubes from being aspirated. For that reason I fix them together with a mattress stitch to the columella. By doing so they can be left so short that they will not be visible. When no septal deviation had to be corrected I leave them or a strip of vaseline-impregnated gauze in place for 3 days only. It is obvious that the patient should not blow his nose for at least 12 days because of the open maxillary sinuses.

After every Le Fort I-type mobilization there is always a little bit of bleeding from the nose, both post-na-

412 CHAPTER 21 The LeFort 1-Type Mobilization Procedure

sally and externally. After a few days it will look like bloodstained water.

21.7 Principal Complications, How to Deal with Them and How to Avoid Them

Problems During Surgery

Bleeding. It is the most common problem which can arise from behind the maxilla when the descending palatine artery in the retromaxillary area is cut with the osteotome when separating the maxilla from the pterygoid process. It is very rare in my experience. If it does happen it has to be stopped immediately by packing that area with gauze. After advancing the maxilla the vessel may become approachable for clipping. Otherwise a piece of bone is wedged in, or a vaseline gauze tampon is used. The end of the gauze strip should be left emerging through the sutured incision and gently removed within 3 weeks.

Ischaemia of the Vestibular Mucosa. It is not uncommon, in particular after the mobilization of the maxilla. In cleft cases, even the palatal mucosa can become blanched. This ischaemia can have two possible origins, either due to a local shock-like contraction of the vessels, partially also as a consequence of previous injection of a vasoconstrictor, or due to existing scars or damage to the palatal blood supply during the mobilization manoeuvre. For the latter reason the use of the maxillary disimpaction forceps was abandoned at my clinic after some bad experiences. When the ischaemia is due to previously existing scars on the palate or due to mechanical damage to the tissues, forget it and pray. I do not think anything will help, not even applying warm saline compressions with some Liquemine (antecoagulation fluid). When the ischaemia is due to a shock-contraction of the small vessels, application of warm wet gauze compressions will help, sometimes with some additionallocal injection of Liquemine at different sites. In these cases, the suturing of the wound edges has to be done as gently as possible.

Pulling the Maxilla or a Portion of it Right Out of the Mouth. It is the worst thing that can happen to the surgeon as well as to the patient! I have heard of such a misfortune several times, but never saw it happen. I can imagine that it could happen when pulling very hard to mobilize the maxilla with any type of instrument. For that reason one should not cut the maxilla into pieces before advancing it. When that is done it is more likely, that one-half suddenly becomes so loose that the surgeon cannot stop pulling. That should not occur when

mobilizing an intact maxilla. However, that too has happened. Avoidance of this is discussed under point 4.

Insufficient Mobilization. It is another problem. Many surgeons, in particular the inexperienced, hesitate to pull very hard. In cleft cases there is no other way to bring the maxilla forward than by using force. In order not to have a nasty surprise by its sudden loosening and then pulling it out of the mouth, all scars around the former operation area must be released by proper mobilization with a periosteal elevator or with a knife but not by elevating the palatal mucosal flaps. If the maxilla or its segments can only be brought into occlusion by force, then a relapse has to be expected.

To eliminate the risk of pulling the maxilla out of the mouth or insufficient mobilization, I had an instrument made by the Medicon Company, which enables the surgeon to pull the maxilla safely forwards, millimetre by millimetre. I called that instrument the maxillary advancer. It too requires that the osteotomies are completed all the way around the maxilla and floor of the nose. It also requires that all scarring in cleft cases is released. But, with that instrument, advancing the maxilla becomes a safe procedure. The maxilla must always be mobilized so well that it can easily be brought into occlusion or overcorrected, with a pair of tweezers.

Fracturing the Maxilla During Mobilization. It is another embarrassing problem. It easily happens when using two disimpaction forceps. A period of intermaxillary fixation will manage this, followed by the insertion of an acrylic splint.

Problems After Surgery

Quite a number are possible:

Late Bleeding from Behind the Tuberosity Area. I have seen this commence hours or days or even a full week after surgery. I have heard of cases in which the bleeding ended in the patient's death. One must reopen that region and pack it. Ligature of the external carotid artery may not stop the bleeding.