Management,Aan

description

Transcript of Management,Aan

-

DOI 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313378.77444.ac 2008;70;2067Neurology

T. D. Fife, D. J. Iverson, T. Lempert, et al.Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology

vertigo (an evidence-based review) : Report of the Quality Practice Parameter: Therapies for benign paroxysmal positional

April 30, 2012This information is current as of

http://www.neurology.org/content/70/22/2067.full.html

located on the World Wide Web at: The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0028-3878. Online ISSN: 1526-632X.Allsince 1951, it is now a weekly with 48 issues per year. Copyright 2008 by AAN Enterprises, Inc.

is the official journal of the American Academy of Neurology. Published continuouslyNeurology

http://www.neurology.org/content/70/22/2067.full.html

-

Practice Parameter: Therapies for benignparoxysmal positional vertigo(an evidence-based review)Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the AmericanAcademy of Neurology

T.D. Fife, MDD.J. Iverson, MDT. Lempert, MDJ.M. Furman, MD,PhD

R.W. Baloh, MDR.J. Tusa, MD, PhDT.C. Hain, MDS. Herdman, PT, PhD,FAPTA

M.J. Morrow, MDG.S. Gronseth, MD

INTRODUCTION Benign paroxysmal positionalvertigo (BPPV) is a clinical syndrome character-ized by brief recurrent episodes of vertigo trig-gered by changes in head position with respect togravity. BPPV is the most common cause of recur-rent vertigo, with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%.1

The term BPPV excludes vertigo caused by le-sions of the CNS. BPPV results from abnormalstimulation of the cupula within any of the threesemicircular canals (figure e-1 on theNeurology

Web site at www.neurology.org); most cases ofBPPV affect the posterior canal. The cupular exci-tatory response is usually related to movement ofotoliths (calcium carbonate crystals) that create acurrent of endolymph within the affected semicir-cular canal. The most common form of BPPV oc-curswhen otoliths from themacula of the utricle fallinto the lumen of the posterior semicircular canalresponding to the effect of gravity. These ectopicotoliths, which have been observed intraoperatively,are referred to as canaliths. The canaliths are denseand move in the semicircular canal when the headposition is changedwith respect to gravity; the cana-lith movement ultimately deflects the cupula, lead-ing to a burst of vertigo and nystagmus. In somecases, canaliths adhere to the cupula, causing cupu-lolithiasis, which is a form of BPPV less responsiveto treatment maneuvers.

Typical signs of BPPV are evoked when thehead is positioned so that the plane of the affectedsemicircular canal is spatially vertical and thus

aligned with gravity. This produces a paroxysmof vertigo and nystagmus after a brief latency. Po-sitioning the head in the opposite direction re-verses the direction of the nystagmus. Theseresponses often fatigue upon repeat positioning.The duration, frequency, and intensity of symptomsof BPPV vary, and spontaneous recovery occurs fre-quently. Table e-1 outlines the characteristics ofBPPV by canal type.

Repositioning maneuvers are believed to treatBPPV by moving the canaliths from the semicir-cular canal to the vestibule from which they areabsorbed. There are a number of repositioningmaneuvers in use, but they lack standardization.The figures and Web-based video clips do not in-clude all variations but represent those maneuversand treatments used in the Class I and Class IIstudies that are reviewed as well as several othersin common use.

This practice parameter seeks to answer the fol-lowing questions: 1) What maneuvers effectivelytreat posterior canal BPPV? 2)Whichmaneuvers areeffective for anterior and horizontal canal BPPV? 3)Are postmaneuver restrictions necessary? 4) Is con-current mastoid vibration important for efficacy ofthe maneuvers? 5) What is the efficacy of habitua-tion exercises, BrandtDaroff exercises, or patientself-administered treatmentmaneuvers? 6) Aremed-ications effective for BPPV? 7) Is surgical occlusionof the posterior canal or singular neurectomy effec-tive for BPPV?

Supplemental data atwww.neurology.org

Address correspondence andreprint requests to theAmerican Academy ofNeurology, 1080 MontrealAve., St. Paul, MN [email protected]

GLOSSARYAAN American Academy of Neurology; BPPV benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; CONSORT Consolidated Stan-dards of Reporting Trials; CRP canalith repositioning procedure; NNT number needed to treat.

From the Barrow Neurological Institute and University of Arizona College of Medicine (T.D.F.), Phoenix, AZ; Humboldt NeurologicalMedical Group, Inc. (D.J.I.), Eureka, CA; Department of Neurology (T.L.), Schlosspark-Klinik, Berlin, Germany; Department ofOtolaryngology (J.M.F.), University of Pittsburgh, PA; Department of Neurology (R.W.B.), Reed Neurological Research Center, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA; Departments of Neurology (R.J.T.) and Rehabilitation Medicine (S.H.), Emory University; Atlanta, GA;Northwestern University (T.C.H.), Chicago, IL; Providence Multiple Sclerosis Center (M.J.M.), Portland, OR; and University of Kansas(G.S.G.), Kansas City, KS.

Approved by the Quality Standards Subcommittee on May 1, 2007; by the Practice Committee on June 21, 2007; and by the AmericanAcademy of Neurology Board of Directors in July 2007.

QSS Subcommittee members, AAN classification of evidence, Classification of recommendations, Conflict of Interest Statement, MissionStatement of the QSS, and references e1e32 are available as supplemental data on theNeurology Web site at www.neurology.org.

Disclosure: Author disclosures are provided at the end of the article.

All figures in this manuscript and online were printed with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.

SPECIAL ARTICLE

Copyright 2008 by AAN Enterprises, Inc. 2067

-

DESCRIPTION OF THE ANALYTIC PROCESSOtoneurologists with expertise in BPPV and gen-eral neurologists with methodologic expertisewere invited by the Quality Standards Subcom-mittee (appendix e-1) to perform this review. Us-ing the four-tiered classification scheme describedin appendix e-2, author panelists rated all rele-vant articles between 1966 and June 2006.

Articles included in this analysis met all of thesecriteria: 1) BPPV was diagnosed by both symptomsof positional vertigo lasting less than 60 seconds,and paroxysmal positional nystagmus in responseto the DixHallpike maneuver (figure 1) or otherappropriate provocative maneuver; 2) for all formsof BPPV, the nystagmuswas characterized by a brieflatency before the onset of nystagmus or a reductionof nystagmus with repeat DixHallpike maneuvers(fatigability); 3) for posterior canal BPPV, a positiveDixHallpike maneuver was defined by the pres-ence of upbeating and torsional nystagmus with thetop pole of rotation beating toward the affected(downside) ear; and 4) for horizontal canal BPPV,the DixHallpike or supine roll maneuver producedhorizontal geotropic (toward the ground) or apo-geotropic (away from the ground) direction-changing paroxysmal positional nystagmus.Geotropic direction-changing positional nystag-mus refers to paroxysmal right beating nystagmuswhen the supine head is turned to the right andparoxysmal left beating nystagmus with the su-pine head turned to the left. Conversely, apogeo-tropic indicates the nystagmus is right beatingwith the head turned to the left and left beatingwith head turned to the right.

ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE Question 1: Whatmaneuvers effectively treat posterior canal BPPV?Canalith repositioning procedure for BPPV.Of15 ran-domized controlled trials identified, there weretwo Class I studies2,3 and three Class II studies.4-6

The first Class I study of 36 patients2 com-pared the canalith repositioning procedure (CRP)(figure 2) with a sham maneuver where the pa-tient was placed in a supine position with the af-fected ear down for 5 minutes and then sat up. Allpatients were symptomatic for at least 2 months;the median duration of symptoms was 17 months(range 2240 months) in the treatment group and4 months (range 2276 months) in the controlgroup, a difference that approached significance.

At 4 weeks, 61% of the treated group reportedcomplete symptom resolution, vs 20% of thesham-treated group (p 0.032). The numberneeded to treat (NNT) was 2.44. The NNT is anepidemiologic measure that indicates the numberof patients that had to have treatment to elimi-nate symptoms in one patient. The DixHallpikemaneuver was negative in 88.9% of treated pa-tients vs 26.7% in sham-treated patients (p 0.001; NNT 1.60), as measured by an observerblinded to treatment.

The second Class I randomized controlled trialand crossover study,3 of 66 patients with a diag-nosis of posterior BPPV based on a positive DixHallpike maneuver, compared a CRP (figure 2)with a sham procedure. The sham procedure con-sisted of a CRP performed on the contralateral,asymptomatic ear.

After 24 hours, 80% of treated patients wereasymptomatic and had no nystagmus with theDixHallpike maneuver compared with 10% ofsham patients (p 0.001; NNT 1.43). At thispoint, all patients in both the treatment and con-trol groups with a persistently positive DixHallpike maneuver underwent a CRP. Ninety-three percent of patients from the original controlgroup reported resolution of symptoms 24 hoursafter undergoing the CRP. By 1 week, 94% of pa-tients in the original treatment group and 82% ofpatients in the original control group (all of whomunderwent a CRP at 24 hours) were asymptomatic(p value not stated). At 4 weeks, 85% of patients inboth groups were asymptomatic.

Three studies were rated as Class II becausethe method of allocation concealment was notspecified. Allocation concealment is a techniquefor preventing researchers from inadvertently in-fluencing which patients are assigned to the treat-ment or placebo group; inadequate allocationconcealment may cause selection bias that overes-timates the treatment effect.7

The first Class II study of 50 patients4 com-pared a CRP with the same sham maneuver per-formed by Lynn et al.,2 with blinded outcomemeasurements of symptom resolution and absent

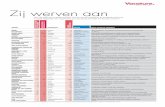

Figure 1 DixHallpike maneuver for diagnosis ofright posterior canal benignparoxysmal positional vertigo(BPPV)

The patients head is turned 45 degrees toward the side tobe tested and then laid back quickly. If BPPV is present, nys-tagmus ensues usually within seconds.

2068 Neurology 70 May 27, 2008 (Part 1 of 2)

-

nystagmus in response to the DixHallpike ma-neuver. One to 2 weeks after treatment, 50%of the treated group reported symptom resolutionvs 19% in the sham group, an absolute differenceof 31% (95% CI 0.06-0.56, p 0.02; NNT 3.22). Using the absence of nystagmus after theDixHallpike maneuver as an outcome measure-ment, an improvement was seen in 65% oftreated patients vs 38% of sham patients, a27% absolute difference (95% CI 0.02 0.52,p 0.046; NNT 3.7).

Another Class II study5 randomized 29 pa-tients to a CRP and another 29 patients to notreatment. The diagnosis of posterior BPPV wasbased on observing nystagmus after the DixHallpike maneuver and a complete neurotologi-cal examination. All patients were given aprescription for cinnarizine to use for vertigo.Over the next month, all patients were exam-

ined at weekly intervals by a blinded observer.Patients with a positive DixHallpike maneu-ver who were assigned to the treatment groupunderwent repeat CRP. A questionnaire wasadministered to patients with a negative DixHallpike maneuver.

At 1 week, 41% of treated patients were symp-tom free, vs 3% of untreated controls (p 0.005;NNT 2.63). The DixHallpike maneuver wasnegative in 75.9% of treated patients vs 48.2% ofuntreated controls, an absolute difference of27.7% (95% CI 0.2410.489, p 0.03; NNT 3.68). At 2 weeks, 65% were symptom free in thetreatment group vs 3% of controls (p 0.005). At3 weeks, 65% were symptom free vs 21% of thecontrols (p 0.014). There were no significantdifferences at 4 weeks. The control group usedcinnarizine more often (23 doses) than did thetreatment group (5.8 doses, p 0.001).

The third study6 randomized 124 patients to aCRP, a Semont liberatory maneuver (figure 3),BrandtDaroff exercises (figure e-2), habituationexercises, or a sham maneuver of slow neck rota-tion and flexion performed with the patient in asitting position. The diagnosis for posterior canalBPPV was based on history and paroxysmal posi-tional nystagmus in response to the DixHallpikemaneuver (figure 1). The median duration ofsymptoms was 4 months (range 10 days to 30years). The outcome measure was an arbitrarypatient-rated vertigo intensity and frequency scaleof 1 to 10 (10 being the most severe or frequent),recorded by a blinded observer.

The treatment effect in this study is difficult toquantify because the results are expressed in theform of regression curves, rather than as discretevalues. At 90 days after treatment, vertigo fre-quency was reportedly significantly reduced inboth CRP and Semont maneuvertreated pa-tients. Both treatment maneuvers were superiorto the sham maneuver (CRP, p 0.021; Semontmaneuver, p 0.010) for vertigo intensity. Thevertigo scores were not significantly different be-tween the CRP and Semont maneuver. There wassignificantly less frequent vertigo in those treatedby either CRP or Semont maneuver comparedwith BrandtDaroff exercises (p 0.033).

The remaining randomized controlled trialswere graded as Class IV because they did notclearly state whether the outcomes were obtainedin a blinded and independent manner8-15 or be-cause of important baseline differences betweenstudy and control groups.16

The literature search also yielded four meta-analyses and one systematic review. All four

Figure 2 Canalith repositioning procedure for right-sided benign paroxysmalpositional vertigo

Steps 1 and 2 are identical to the DixHallpike maneuver. The patient is held in the right headhanging position (Step 2) for 20 to 30 seconds, and then in Step 3 the head is turned 90degrees toward the unaffected side. Step 3 is held for 20 to 30 seconds before turning thehead another 90 degrees (Step 4) so the head is nearly in the face-down position. Step 4 isheld for 20 to 30 seconds, and then the patient is brought to the sitting up position. Themovement of the otolith material within the labyrinth is depicted with each step, showing howotoliths are moved from the semicircular canal to the vestibule. Although it is advisable forthe examiner to guide the patient through these steps, it is the patients head position that isthe key to a successful treatment.

Neurology 70 May 27, 2008 (Part 1 of 2) 2069

-

meta-analyses17-20 concluded that CRP and Se-mont maneuver have significantly greater efficacythan no treatment in BPPV. All references in-cluded in these four meta-analyses were reviewedindividually for this practice parameter.

In all these studies, complications of nauseaand vomiting, fainting, or conversion to horizon-tal canal BPPV occurred in 12% of patients. In aretrospective study of 85 patients treated with aCRP,21 6% developed a conversion to either hori-zontal canal BPPV or anterior canal BPPV.

Semont maneuver for BPPV. One Class II study6

showed that patients treated with Semont maneu-ver were significantly improved compared withthose treated with a sham maneuver. A Class IIIstudy22 randomized 156 patients to Semont ma-neuver, medical therapy (flunarizine 10 mg/dayfor 60 days), or no treatment. At 6-month follow-up, 94.2% of patients treated with Semont ma-neuver reported symptom resolution, vs 57.7% ofpatients treated with flunarizine and 34.6% of pa-tients who received no treatment.

A Class IV study23 comparing Semont maneu-ver and a CRP either with or without post-treatment instructions found success rates for allgroups ranging from 88% to 96%, with no differ-ences between groups. Another Class IV study24

compared patients randomized to treatment withCRP, Semont maneuver, or BrandtDaroff exer-cises. Symptom resolution among those treatedwith either CRP or Semont maneuver at 1 weekwas the same (74% vs 71%; 24% for BrandtDaroff exercises). At 3-month follow-up, 93% ofpatients treated with CRP were asymptomatic vs

77% of those treated with Semont maneuver (p 0.027); 62% of patients treated with BrandtDaroff exercises were asymptomatic at 3 months.

Conclusion. Two Class I studies and three ClassII studies have demonstrated a short-term (1 dayto 4 weeks) resolution of symptoms in patientstreated with the CRP, with NNT ranging from1.43 to 3.7. The Semont maneuver is possiblymore effective than no treatment (Class III), asham treatment (Class II), or BrandtDaroff exer-cises (Class IV) as treatment for posterior canalBPPV. Two Class IV studies comparing CRP withSemont maneuver have produced conflicting re-sults; one showed no difference between groups,and the other showed a lower recurrence rate inpatients undergoing CRP.

Recommendation (appendix e-3). Canalith reposi-tioning procedure is established as an effectiveand safe therapy that should be offered to patientsof all ages with posterior semicircular canal BPPV(Level A recommendation). The Semont maneu-ver is possibly effective for BPPV but receives onlya Level C recommendation based on a singleClass II study. Although many experts believethat the Semont maneuver is as effective as cana-lith repositioning maneuver, based on currentlypublished articles the Semont maneuver can onlybe classified as possibly effective. There is in-sufficient evidence to establish the relative effi-cacy of the Semont maneuver to CRP (Level U).

Question 2: Which maneuvers are the most effectivetreatments for horizontal canal and anterior canalBPPV? Horizontal canal BPPV. Horizontal canalBPPV accounts for 10% to 17% of BPPV,25-29

though some reports have been even higher.30,31

The nystagmus of horizontal canal BPPV is hori-zontal and changes direction when the head isturned to the right or left while supine (direction-changing paroxysmal positional nystagmus). Thedirection-changing positional nystagmus may beeither geotropic or apogeotropic.31 The geotropicform, which is thought to result from free-movingotoconial debris in the long arm of the semicircularduct, is generally more responsive to treatment. Theapogeotropic form is likely due to otoconial mate-rial in the short arm of the canal or attached to thecupula (cupulolithiasis).24,32 Hence, one seeks toconvert the more treatment-resistant apogeotropicto the more treatment-responsive geotropic nystag-mus form of horizontal canal BPPV.32,33

The nystagmus and vertigo of horizontal canalBPPV may be provoked by the DixHallpike ma-neuver but are more reliably induced by the su-pine head roll test or so-called PagniniMcCluremaneuver (figure 4).34-36 The methods used to de-

Figure 3 Semont maneuver for right-sided benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

While sitting up in Step 1, the patients head is turned 45 degrees toward the left side, andthen the patient is rapidly moved to the side-lying position as depicted in Step 2. This positionis held for 30 seconds or so, and then the patient is rapidly taken to the opposite side-lyingposition without pausing in the sitting position or changing the head position relative to theshoulder. This is in contrast to the BrandtDaroff exercises that entail pausing in the sittingposition and turning the head with body position changes.

2070 Neurology 70 May 27, 2008 (Part 1 of 2)

-

termine the affected side in horizontal canal BPPVare described elsewhere.30,37,38,e1 CRP or modifiedEpley maneuvers are usually ineffective for hori-zontal canal BPPV,21,34 so a number of alternativemaneuvers have been devised.

Variations of the roll maneuver (Lempert ma-neuver or barbecue roll maneuver) (figure 5) are

the most widely published treatments for hori-zontal canal BPPV.25,26,29,31,32,34,36,38,e1,e2 Success intreatment, based on all Class IV studies, is proba-bly 75%32,e2 but ranges from approximately50% to nearly 100%. However, the studies useddiffering and sometimes unclear endpoints, andmany lacked control groups to allow comparisonbetween the treatment and the natural rate of res-olution of this condition.

The Gufoni maneuver is another techniquethat has been reported as effective in treating hor-izontal canal BPPVe3 (figure e-3, A and B). Severalstudies, all Class IV, have reported success usingthis or a similar maneuver for horizontal canalBPPV for both the geotropic and apogeotropicnystagmus forms.32,33,38,e4 Similarly, the Vannuc-chiAsprella liberatory maneuver may be effec-tive, but there is only limited Class IV datasupporting its use.38,e5,e6 Casani et al.32 and Appianiet al.33 review other techniques used with success inthe treatment of both the geotropic and apogeotro-pic forms of horizontal canal BPPV.

Another treatment reported as effective30,32,36,e2,e7

is referred to as forced prolonged positioning. Withthis method, the patient lies down laterally to theaffected side, and the head is then turned 45 degreestoward the ground and maintained in that positionfor 12 hours before the patient is returned to thestarting position. Some authors advocate this tech-nique for refractory horizontal canal BPPV.32,e3 Us-ing this approach, one Class IV study reportedremission rates of 75% to 90%.32

Anterior canal BPPV. Anterior canal BPPV is usu-ally transitory and most often is the result of ca-nal switch that occurs in the course of treatingother more common forms of BPPV.21

We identified only two studies specifically ad-dressing the treatment of anterior canal BPPV;both were Class IV studies.e8,e9 Success rates werebetween 92% and 97%, though there were nocontrols to determine whether this represents animprovement over the natural history of this fre-quently self-resolving form of BPPV.

Conclusion. Based on Class IV studies, variationsof the Lempert supine roll maneuver, the Gufonimethod, or forced prolonged positioning seemmod-erately effective for horizontal canal BPPV.Twoun-controlled Class IV studies report high responserates to maneuvers for anterior canal BPPV.

Recommendation: None (Level U).

Question 3: Are postmaneuver activity restrictionsnecessary after canalith repositioning procedure? Inone Class I study2 and one Class II4 study demon-strating the benefit of CRP, patients wore a cervi-cal collar for 48 hours and avoided sleeping on the

Figure 4 Supine roll test (PagniniMcClure maneuver) to detect horizontal canalbenign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

The patient may be taken from sitting to straight supine position (1). The head is turned to theright side (2) with observation of nystagmus and then turned back to face up (1). Then thehead is turned to the left side (3). The side with the most prominent nystagmus is taken to bethe affected horizontal semicircular canal. The direction of nystagmus in each position deter-mines whether the horizontal canal BPPV is of the geotropic or apogeotropic type.

Figure 5 Lempert roll maneuver for right-sided horizontal canal benignparoxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

When it is determined to be horizontal canal BPPV affecting the right side, the patient is takenthrough a series of step-wise 90-degree turns away from the affected side in Steps 1through 5, holding each position for 10 to 30 seconds. From Step 5, the patient positions hisor her body to the back (6) in preparation for the rapid and simultaneous movement from thesupine face up to the sitting position (7).

Neurology 70 May 27, 2008 (Part 1 of 2) 2071

-

affected side for 1 week. One Class I study3 andtwo Class II studies5,6 that demonstrated the ben-efit of CRP used no post-treatment restrictions orinstructions. These studies were not designed todetermine whether such restrictions affect treat-ment success; however, there seems to be little dif-ference in the rate of treatment success whether ornot restrictions were included.

Six Class IV studies comparing CRP with andwithout post-treatment activity restriction wereidentified.23,e10-e14 Five studies23,e10-e13 showed noadded benefit from post-treatment activity re-striction or positions. Only one study showed aminimal benefit in patients with post-activity re-strictions, as measured by the number of maneu-vers required to produce a negative DixHallpikemaneuver.e14

Conclusion and recommendation. Five Class IVstudies support the omission of post-treatmentactivity restrictions; one study supports the use ofpost-treatment restrictions. There is insufficientevidence to determine the efficacy of post-maneuver restrictions in patients treated withCRP (Level U).

Question 4: Is it necessary to include mastoid vibrationwith repositioning maneuvers? Mastoid vibrationwas included in the original Epley repositioningmaneuver. One Class II study,e15 comparing pa-tients with posterior canal BPPV treated by ap-propriate canalith repositioning maneuvers,performed with and without vibration, showedno difference in immediate symptom resolutionor relapse rate between groups.

A Class III studye16 compared patients treatedby CRP with and without mastoid vibration.There was no difference in symptom relief be-tween the groups at 4 to 6 weeks (p 0.68).

Two Class IV studiese17,e18 showed no differ-ence in the rate of symptom resolution betweenpatients treated by a CRP with or without mas-toid vibration. A third Class IV study9 reportedthat of patients treated by a CRP with vibration,92% were improved, vs 60% improvementwith CRP alone.

Conclusion and recommendation.OneClass II, oneClass III, and two Class IV studies showed noadded benefit when mastoid vibration was addedto a CRP as treatment for posterior canal BPPV.Mastoid oscillation is probably of no added bene-fit to patients treated with CRP for posterior ca-nal BPPV (Level C recommendation).

Question 5: What is the efficacy of BrandtDaroffexercises, habituation exercises, or patient self-administered treatments for BPPV? A Class II studythat randomized patients to a CRP, a liberatory

maneuver, BrandtDaroff exercises, habituationexercises, or a sham treatment found that patientstreatedwith habituation exercises did no better thanthose treated with a sham procedure.6 Patientstreated with BrandtDaroff exercises did worsethan those treated with CRP or liberatory maneu-vers but were not compared with sham-treatedpatients.

A Class IV study24 compared BrandtDaroffexercises, performed three times daily, with theSemont maneuver or CRP. Patients treated withmaneuvers were pretreated with diazepam andgiven postmaneuver activity restrictions; patientstreated with BrandtDaroff exercises were not.Compliance with the exercises was not recorded.At 1-week follow-up, 24% of patients treatedwith BrandtDaroff exercises were symptom free,vs 74% of those treated with the Semont maneu-ver or CRP. Given the limitations of the study, itsvalidity is questionable.

Three Class IV studies investigated the effi-cacy of patient-administered treatment forBPPV using various techniques. One studyfound 88% improvement of BPPV when treatedwith CRP and home CRP compared with 69%improvement in those only treated with CRPonce.e19 Another study reported improved reso-lution of nystagmus among patients that self-administered CRP (64% recovery) vs self-administered BrandtDaroff exercises (23%).e20

The third study found that 95% had resolutionof positional nystagmus 1 week after self-treatment with CRP vs 58% of self-treatmentwith a modified Semont maneuver.e21

Conclusion and recommendation. One Class II andone Class IV study suggest that BrandtDaroffexercises or habituation exercises are less effectivethan CRP in the treatment of posterior canalBPPV. Self-administered BrandtDaroff exercisesor habituation exercises are less effective thanCRP in the treatment of posterior canal BPPV(Level C). There is insufficient evidence to recom-mend or refute self-treatment using Semont ma-neuver or CRP for BPPV (Level U).

Question 6: What is the efficacy of medication treat-ments for BPPV? One Class III studye22 found nodifference between lorazepam, 1 mg three timesdaily; diazepam, 5 mg three times daily; or pla-cebo over the 4-week study period. Another ClassIII study21 found that flunarizine was more effec-tive than no treatment but less effective than Se-mont maneuver in eliminating symptoms. Thereare no randomized controlled trials of meclizine

2072 Neurology 70 May 27, 2008 (Part 1 of 2)

-

or other drugs used for motion sickness in thetreatment of BPPV.

Conclusion and recommendation. A single Class IIIstudy did not demonstrate that lorazepam or di-azepam hastened resolution of symptoms inBPPV. A single Class III study demonstrated somebenefit of flunarizine, a drug that is unavailable inthe United States, in BPPV. There is no evidenceto support a recommendation of any medicationin the routine treatment for BPPV (Level U).

Question 7: What are the safety and efficacy of sur-gical treatments for posterior canal BPPV? All stud-ies of surgical treatment for refractory BPPV areClass IV. The most common procedure is fenes-tration and occlusion of the posterior semicircu-lar canal. Five studies, e23-e27 with a total of 86patients undergoing canal occlusion, reportedcomplete relief of BPPV symptoms in 85, as as-certained by the treating surgeon. Reported com-plications included a mild conductive hearingloss for 4 weeks or less, mild and transientunsteadiness in most patients, and a high fre-quency sensorineural hearing loss in 6 patients.

In a Class IV study of singular neurectomyas a treatment for intractable BPPV,e28 96.8%were reported to have complete relief; severesensorineural hearing loss occurred in 3.7% ofpatients.

Conclusion and recommendation. Six unblinded,retrospective Class IV studies report relief fromsymptoms of BPPV in nearly every patient under-going posterior semicircular canal occlusion orsingular neurectomy. Because the studies areClass IV, they do not provide sufficient evidenceto recommend or refute posterior semicircular ca-nal occlusion or singular neurectomy as treatmentfor BPPV (Level U).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RE-SEARCH Class I studies are needed to clarify thebest treatments for horizontal canal BPPV. Futurestudies on these topics should adhere to theConsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials(CONSORT) criteria using validated, clinicallyrelevant outcomes.

PROGNOSIS AND RECURRENCE RATE The re-lapse rate and second recurrence rate of BPPV arenot fully established. Short-term relapse rates rangefrom 7% to nearly 23% within a year of treatment,but long-term recurrences may approach 50%, de-pending on the age of the patient. e29-e32

DISCLOSUREThe authors report the following disclosures: Dr. Fife hasreceived research support from GlaxoSmithKline and esti-

mates that 6% of his time is spent on canalith repositioningprocedures. Dr. Iverson has nothing to disclose. Dr. Lempertestimates that 5% of his time is spent on videooculogra-phy. Dr. Furman holds stock options in Neurokinetics, hasreceived research support from Merck, has served as an ex-pert witness on vestibular function, and estimates that 1% ofhis time is spent on the Epley maneuver. Dr. Baloh estimates5% of his time is spent on ENG. Dr. Tusa estimates that 5%of his time is spent on quantified positional testing. Dr. Hainestimates that 5% of his time is spent on ENG and 5% onVEMP. Dr. Herdman received research support fromVAMC and served as an expert witness on the Hallpike-Dixmaneuver. Dr. Morrow has received honoraria from Bio-genIdec and has served as an expert witness and consultanton medico-legal proceedings. Dr. Gronseth has receivedspeaker honoraria from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, andBoehringer Ingelheim and served on the IDMC Committeeof Ortho-McNeil.

DISCLAIMERThis statement is provided as an educational service of theAmerican Academy of Neurology. It is based on an assess-ment of current scientific and clinical information. It isnot intended to include all possible proper methods ofcare for a particular neurologic problem or all legitimatecriteria for choosing to use a specific procedure. Neither isit intended to exclude any reasonable alternative method-ologies. The American Academy of Neurology recognizesthat specific patient care decisions are the prerogative ofthe patient and the physician caring for the patient, basedon all of the circumstances involved.

Received August 1, 2007. Accepted in final form February23, 2008.

REFERENCES1. von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, et al. Epidemiol-

ogy of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a popula-tion based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2007;78:710715.

2. Lynn S, Pool A, Rose D, Brey R, Suman V. Random-ized trial of the canalith repositioning procedure. Oto-laryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;113:712720.

3. von Brevern M, Seelig T, Radtke A, Tiel-Wilck K,Neuhauser H. Long-term efficacy of Epleys manoeu-vre: a double-blind randomized trial. J Neurol Neuro-surg Psychiatr 2006;77:980982.

4. Froehling DA, Bowen JM, Mohr DN, et al. The cana-lith repositioning procedure for the treatment of be-nign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomizedcontrolled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:695700.

5. Yimtae K, Srirompotong S, Srirompotong S, Sae-SeawP. A randomized trial of the canalith repositioning pro-cedure. Laryngoscope 2003;113:828832.

6. Cohen HS, Kimball KT. Effectiveness of treatments forbenign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posteriorcanal. Otol Neurotol 2005;26:10341040.

7. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in ran-domised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet2002;359:614618.

Neurology 70 May 27, 2008 (Part 1 of 2) 2073

-

8. Sherman D, Massoud EA. Treatment outcomes of be-nign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Otolaryngol2001;30:295299.

9. Li JC. Mastoid oscillation: a critical factor for successin canalith repositioning procedure. Otolaryngol HeadNeck Surg 1995;112:670675.

10. Blakley BW. A randomized, controlled assessment ofthe canalith repositioning maneuver. OtolaryngolHead Neck Surg 1994;110:391396.

11. Lempert T, Wolsley C, Davies R, et al. Three hundredsixty-degree rotation of the posterior semicircular ca-nal for treatment of benign positional vertigo: aplacebo-controlled trial. Neurology 1997;49:729733.

12. Wolf M, Hertanu T, Novikov I, Kronenberg J. Epleysmanoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: aprospective study. Clin Otolaryngol 1999;24:4346.

13. Asawavichianginda S, Isipradit P, Snidvongs K, et al.Canalith repositioning for benign paroxysmal posi-tional vertigo: a randomized, controlled trial. Ear NoseThroat J 2000;79:732734.

14. Angeli SI, Hawley R, Gomez O. Systematic approachto benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the elderly.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;128:719725.

15. Sridhar S, Panda N. Particle repositioning manoeuvrein benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: is it reallysafe? J Otolaryngol 2005;34:4145.

16. Chang AK, Schoeman G, Hill M. A randomized clini-cal trial to assess the efficacy of the Epley maneuver inthe treatment of acute benign positional vertigo. AcadEmerg Med 2004;11:918924.

17. Lopez-Escamaez J, Gonzalez-Sanchez M, Salinero J.Meta-analysis of the treatment of benign paroxysmalpositional vertigo by Epley and Semont maneuvers.Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 1999;50:366370.

18. Woodworth BA,GillespieMB, Lambert PR. The canalithrepositioning procedure for benign positional vertigo: ameta-analysis. Laryngoscope 2004;114:11431146.

19. Teixeira LJ, Machado JN. Maneuvers for the treat-ment of benign positional paroxysmal vertigo: a sys-tematic review. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed)2006;72:130139.

20. Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley manoeuvre for benignparoxysmal positional vertigo: a systematic review.Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 2002;27:440445.

21. Herdman SJ, Tusa RJ. Complications of the canalithrepositioning procedure. Arch Otolaryngol Head NeckSurg 1996;122:281286.

22. Salvinelli F, Casale M, Trivelli M, et al. Benign parox-ysmal positional vertigo: a comparative prospectivestudy on the efficacy of Semonts maneuver and notreatment strategy. Clin Ter 2003;154:711.

23. Massoud EA, Ireland DJ. Post-treatment instructionsin the nonsurgical management of benign paroxysmalpositional vertigo. J Otolaryngol 1996;25:121125.

24. Soto Varela A, Bartual Magro J, Santos Perez S, et al.Benign paroxysmal vertigo: a comparative prospectivestudy of the efficacy of Brandt and Daroff exercises,Semont and Epley maneuver. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhi-nol (Bord) 2001;122:179183.

25. White JA, Coale KD, Catalano PJ, Oas JG. Diagnosisand management of horizontal semicircular canal be-nign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol HeadNeck Surg 2005;133:278284.

26. Prokopakis EP, Chimona T, Tsagournisakis M, etal. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: 10-year ex-perience in treating 592 patients with canalith repo-sitioning procedure. Laryngoscope 2005;115:16671671.

27. Caruso G, Nuti D. Epidemiological data from 2270PPV patients. Audiological Med 2005;3:711.

28. Leopardi G, Chiarella G, Serafini G, et al. Paroxysmalpositional vertigo: short- and long-term clinical andmethodological analyses of 794 patients. Acta Otolar-yngol Ital 2003;23:155160.

29. Fife TD. Recognition and management of horizontalcanal benign positional vertigo. Am J Otol 1998;19:345351.

30. Koo JW, Moon IJ, Shim WS, Moon SY, Kim JS. Valueof lying-down nystagmus in the lateralization of hori-zontal semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positionalvertigo. Otol Neurol 2006;27:367371.

31. Nuti D, Agus G, Barbieri M-T, Passali D. The manage-ment of horizontal-canal paroxysmal positional ver-tigo. Acta Otolaryngol 1998;118:455460.

32. Casani AP, Vannucchi G, Fattori B, Berrettini S. Thetreatment of horizontal canal positional vertigo: ourexperience in 66 cases. Laryngoscope 2002;112:172178.

33. Appiani GC, Catania G, Gagliardi M, Cuiuli G. Repo-sitioning maneuver for the treatment of the apogeotro-pic variant of horizontal canal benign paroxysmalpositional vertigo. Otol Neurotol 2005;26:257260.

34. Lempert T, Tiel-Wilck K. A positional maneuver fortreatment of horizontal-canal benign positional ver-tigo. Laryngoscope 1996;106:476478.

35. McClure JA. Horizontal canal BPV. J Otolaryngol1985;14:3035.

36. Appiani GC, Gagliardi M, Magliulo G. Physical treat-ment of horizontal canal benign positional vertigo. EurArch Otorhinolaryngol 1997;254:326328.

37. Han BI, Oh HJ, Kim JS. Nystagmus while recumbentin horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional ver-tigo. Neurology 2006;66:706710.

38. Asprella Libonati G. Diagnostic and treatment strategyof the lateral semicircular canal canalolithiasis. ActaOtorhinolaryngol Ital 2005;25:277283.

2074 Neurology 70 May 27, 2008 (Part 1 of 2)

-

DOI 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313378.77444.ac 2008;70;2067Neurology

T. D. Fife, D. J. Iverson, T. Lempert, et al.American Academy of Neurology

evidence-based review) : Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the Practice Parameter: Therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an

April 30, 2012This information is current as of

ServicesUpdated Information &

http://www.neurology.org/content/70/22/2067.full.htmlincluding high resolution figures, can be found at:

Supplementary Material

.DC2.htmlhttp://www.neurology.org/content/suppl/2008/06/09/70.22.2067

.DC3.htmlhttp://www.neurology.org/content/suppl/2008/11/16/70.22.2067

.DC1.htmlhttp://www.neurology.org/content/suppl/2008/05/24/70.22.2067Supplementary material can be found at:

References

1http://www.neurology.org/content/70/22/2067.full.html#ref-list-This article cites 38 articles, 9 of which can be accessed free at:

Citations

urlshttp://www.neurology.org/content/70/22/2067.full.html#related-This article has been cited by 11 HighWire-hosted articles:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.neurology.org/cgi/collection/vertigoVertigo

http://www.neurology.org/cgi/collection/nystagmusNystagmus

http://www.neurology.org/cgi/collection/all_neurotologyAll Neurotologyfollowing collection(s):This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.neurology.org/misc/about.xhtml#permissionstables) or in its entirety can be found online at: Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

Reprints http://www.neurology.org/misc/addir.xhtml#reprintsus

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://www.neurology.org/content/70/22/2067.full.htmlhttp://www.neurology.org/content/suppl/2008/05/24/70.22.2067.DC1.htmlhttp://www.neurology.org/content/suppl/2008/11/16/70.22.2067.DC3.htmlhttp://www.neurology.org/content/suppl/2008/06/09/70.22.2067.DC2.htmlhttp://www.neurology.org/content/70/22/2067.full.html#ref-list-1http://www.neurology.org/content/70/22/2067.full.html#related-urlshttp://www.neurology.org/cgi/collection/all_neurotologyhttp://www.neurology.org/cgi/collection/nystagmushttp://www.neurology.org/cgi/collection/vertigohttp://www.neurology.org/misc/about.xhtml#permissionshttp://www.neurology.org/misc/addir.xhtml#reprintsus