Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2015: A ...Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2...

Transcript of Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2015: A ...Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2...

Management of Hyperglycemia inType 2 Diabetes, 2015: A Patient-Centered ApproachUpdate to a Position Statement of theAmerican Diabetes Association and theEuropean Association for the Study ofDiabetesDiabetes Care 2015;38:140–149 | DOI: 10.2337/dc14-2441

In 2012, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for theStudy of Diabetes (EASD) published a position statement on the management of hyper-glycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes (1,2). This was needed because of an increasingarray of antihyperglycemic drugs and growing uncertainty regarding their proper selec-tion and sequence. Because of a paucity of comparative effectiveness research on long-term treatment outcomeswithmanyof thesemedications, the 2012publicationwas lessprescriptive than prior consensus reports. We previously described the need to individ-ualize both treatment targets and treatment strategies, with an emphasis on patient-centered care and shared decision making, and this continues to be our position,although therearenowmorehead-to-head trials that showslight variancebetweenagentswith regard to glucose-lowering effects. Nevertheless, these differences are often smalland would be unlikely to reflect any definite differential effect in an individual patient.The ADA and EASD have requested an update to the position statement incorpo-

rating new data from recent clinical trials. Between June and September of 2014, theWriting Group reconvened, including one face-to-facemeeting, to discuss the changes.An entirely new statement was felt to be unnecessary. Instead, the group focused onthose areas where revisions were suggested by a changing evidence base. This brieferarticle should therefore be read as an addendum to the previous full account (1,2).

GLYCEMIC TARGETS

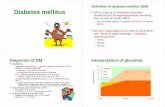

Glucose control remains a major focus in the management of patients with type 2diabetes. However, this should always be in the context of a comprehensive car-diovascular risk factor reduction program, to include smoking cessation and theadoption of other healthy lifestyle habits, blood pressure control, lipid managementwith priority to statin medications, and, in some circumstances, antiplatelet ther-apy. Studies have conclusively determined that reducing hyperglycemia decreasesthe onset and progression of microvascular complications (3,4). The impact ofglucose control on cardiovascular complications remains uncertain; a more modestbenefit is likely to be present, but probably emerges only after many years ofimproved control (5). Results from large trials have also suggested that overlyaggressive control in older patients with more advanced disease may not havesignificant benefits and may indeed present some risk (6). Accordingly, insteadof a one-size-fits-all approach, personalization is necessary, balancing the benefitsof glycemic control with its potential risks, taking into account the adverse effects ofglucose-lowering medications (particularly hypoglycemia), and the patient’s ageand health status, among other concerns. Figure 1 displays those patient and dis-ease factors that may influence the target for glucose control, as reflected by HbA1c.The main update to this figure is the separation of those factors that are potentiallymodifiable from those that are usually not. The patient’s attitude and expectedtreatment efforts and access to resources and support systems are unique in so

1Section of Endocrinology, Yale University Schoolof Medicine, Yale-New Haven Hospital, New Ha-ven, CT2International Diabetes Center at Park Nicollet,Minneapolis, MN3Division of Endocrinology, University of NorthCarolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC4Diabetes Center/Department of Internal Medi-cine, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam,the Netherlands5Department of Medicine, University of PisaSchool of Medicine, Pisa, Italy6DiabeteszentrumBadLauterberg, Bad Lauterbergim Harz, Germany7Division of Endocrinology, Keck School of Med-icine of the University of Southern California, LosAngeles, CA8Second Medical Department, Aristotle Univer-sity Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece9American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA10Department of Family and Community Medi-cine, Jefferson Medical College, Thomas JeffersonUniversity, Philadelphia, PA11Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology andMetabolism, Churchill Hospital, Oxford, U.K.12National Institute for Health Research (NIHR),Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, U.K.13Harris Manchester College, University of Ox-ford, Oxford, U.K.

Corresponding author: Silvio E. Inzucchi, [email protected].

S.E.I. and D.R.M. were co-chairs for the PositionStatement Writing Group. R.M.B., J.B.B., A.L.P.,and R.W. were the Writing Group for the Amer-ican Diabetes Association. M.D., E.F., M.N., andA.T. were the Writing Group for the EuropeanAssociation for the Study of Diabetes.

M.D. is credited posthumously. Her experience,wisdom, and wit were key factors in the creationof the original 2012 position statement; theycontinued to resonate with us during the writingof this update.

This article is being simultaneously published inDiabetes Care and Diabetologia by the AmericanDiabetes Association and the European Associa-tion for the Study of Diabetes.

This article contains Supplementary Data onlineat http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc14-2441/-/DC1.

A slide set summarizing this article is availableonline.

© 2014 by the American Diabetes Associationand Springer-Verlag. Copying with attributionallowed for any noncommercial use of the work.

Silvio E. Inzucchi,1 Richard M. Bergenstal,2

John B. Buse,3 Michaela Diamant,4

Ele Ferrannini,5 Michael Nauck,6

Anne L. Peters,7 Apostolos Tsapas,8

Richard Wender,9,10 and

David R. Matthews11,12,13

140 Diabetes Care Volume 38, January 2015

POSITION

STATEMEN

T

far as they may improve (or worsen) overtime. Indeed, the clinical team should en-courage patient adherence to therapythrough education and also try to optimizecare in the context of prevailing healthcoverage and/or the patient’s financialmeans. Other features, such as age, lifeexpectancy, comorbidities, and the risksand consequences to the patient from anadverse drug event, aremore or less fixed.Finally, the usual HbA1c goal cut-off pointof 7% (53.0 mmol/mol) has also been in-serted at the top of the figure to providesome context to the recommendations re-garding stringency of treatment efforts.

THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS (SEETABLE 1; FOR OTHER UNCHANGEDOPTIONS, ALSO REFER TO THEORIGINAL STATEMENT [1,2])

Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter 2InhibitorsThe major change in treatment optionssince the publication of the 2012 posi-tion statement has been the availabilityof a new class of glucose-lowering drugs,the sodium–glucose cotransporter 2

(SGLT2) inhibitors (7). These agents re-duce HbA1c by 0.5–1.0% (5.5–11mmol/mol) versus placebo (7,8).When compared with most standardoral agents in head-to-head trials,they appear to be roughly similarly ef-ficacious with regard to initial HbA1c

lowering (9–12). Their mechanism ofaction involves inhibiting the SGLT2 inthe proximal nephron, thereby reduc-ing glucose reabsorption and increas-ing urinary glucose excretion by up to80 g/day (13,14). Because this action isindependent of insulin, SGLT2 inhibi-tors may be used at any stage of type2 diabetes, even after insulin secretionhas waned significantly. Additional po-tential advantages include modestweight loss (;2 kg, stabilizing over 6–12 months) and consistent loweringof systolic and diastolic blood pressurein the order of ;2–4/;1–2 mmHg(7,8,15). Their use is also associatedwith reductions in plasma uric acid lev-els and albuminuria (16), although theclinical impact of these changes overtime is unknown.

Side effects of SGLT2 inhibitor ther-apy include genital mycotic infections,at rates of about 11% higher in womenand about 4% higher in men comparedwith placebo (17); in some studies, aslight increase in urinary tract infectionswas shown (7,9,12,17,18). They alsopossess a diuretic effect, and so symp-toms related to volume depletion mayoccur (7,19). Consequently, theseagents should be used cautiously in theelderly, in any patient already on a di-uretic, and in anyone with a tenuous in-travascular volume status. Reversiblesmall increases in serum creatinine occur(14,19). Increasedurine calciumexcretionhas been observed (20), and the U.S.Food and Drug Administration (FDA)mandated a follow-up of upper limb frac-tures of patients on canagliflozin after anadverse imbalance in cases was reportedin short-term trials (21). Small increases inLDL cholesterol (;5%) have been notedin some trials, the implications of whichare unknown. Due to their mechanism ofaction, SGLT2 inhibitors are less effectivewhen the estimated GFR (eGFR) is,45–60 mL/min/1.73 m2; currently availableagents have variable label restrictionsfor values below this threshold.

Data onmicrovascular outcomes withSGLT2 inhibitors are lacking (as withmost agents other than sulfonylureasand insulin). Effects onmacrovascular dis-ease are also unknown; cardiovascularsafety trials are currently in progress (22).

ThiazolidinedionesEarlier concerns that the thiazolidine-diones (TZDs)din particular pioglitazonedare associated with bladder cancer havelargely been allayed by subsequent evi-dence (23–25). These agents tend tocause weight gain and peripheral edemaand have been shown to increase the in-cidence of heart failure (26). They alsoincrease the risk of bone fractures, pre-dominately inwomen (27). Pioglitazone isnow available as a generic drug, substan-tially decreasing its cost.

Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 InhibitorsOne large trial involving the dipeptidylpeptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitor saxagliptinfound no overall cardiovascular risk orbenefit (although the follow-up wasonly slightly more than 2 years) com-pared with placebo (28). However,more heart failure hospitalizations oc-curred in the active therapy group(3.5% vs. 2.8%, P 5 0.007) (28,29).

Figure 1—Modulation of the intensiveness of glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. Depiction ofpatient and disease factors that may be used by the practitioner to determine optimal HbA1ctargets in patients with type 2 diabetes. Greater concerns regarding a particular domain arerepresented by increasing height of the corresponding ramp. Thus, characteristics/predica-ments toward the left justify more stringent efforts to lower HbA1c, whereas those towardthe right suggest (indeed, sometimes mandate) less stringent efforts. Where possible, suchdecisions should be made with the patient, reflecting his or her preferences, needs, and values.This “scale” is not designed to be applied rigidly but to be used as a broad construct to guideclinical decision making. Based on an original figure by Ismail-Beigi et al. (59).

care.diabetesjournals.org Inzucchi and Associates 141

Table

1—Pro

pertiesofava

ilable

gluco

se-loweringagents

intheU.S.andEuro

pethatmayguideindividualize

dtreatm

entch

oicesin

patients

withtype2diabetes

Class

Compound(s)

Cellularmechanism(s)

Primaryph

ysiologicalaction(s)

Advantages

Disadvantages

Cost*

Biguanides

cMetform

inActivates

AMP-kinase

(?other)

c↓Hep

aticglucose

production

cExtensive

experience

cGastrointestinalsideeffects(diarrhea,

abdominalcram

ping)

Low

cNohypoglycem

iacLacticacidosisrisk

(rare)

c↓CVDeven

ts(UKPD

S)cVitam

inB12defi

cien

cycMultiplecontraindications:CKD

,acidosis,

hypoxia,deh

ydration,etc.

Sulfonylureas

2ndGen

eration

ClosesKATPchan

nelson

b-cellp

lasm

amem

branes

c↑Insulin

secretion

cExtensive

experience

cHypoglycem

iaLow

cGlyburide/gliben

clam

ide

c↓Microvascularrisk

(UKPD

S)c↑Weight

cGlipizide

c?Bluntsmyocardialischem

icpreconditioning

cGliclazide†

cLowdurability

cGlim

epiride

Meglitinides

(glinides)

cRep

aglinide

ClosesKATPchan

nelson

b-cellp

lasm

amem

branes

c↑Insulin

secretion

c↓P

ostprandialglucose

excursions

cHypoglycem

iaModerate

cNateglinide

cDosingflexibility

c↑Weight

c?Bluntsmyocardialischem

icpreconditioning

cFreq

uen

tdosingsched

ule

TZDs

cPioglitazone‡

Activates

thenuclear

transcriptionfactor

PPAR-g

c↑Insulin

sensitivity

cNohypoglycem

iac↑Weight

Low

cRosiglitazone§

cDurability

cEdem

a/heartfailure

c↑HDL-C

cBonefractures

c↓Triglycerides

(pioglitazone)

c↑LD

L-C(rosiglitazone)

c?↓CVDeven

ts(PROactive,

pioglitazone)

c?↑MI(m

eta-an

alyses,rosiglitazone)

a-Glucosidase

inhibitors

cAcarbose

Inhibitsintestinal

a-glucosidase

cSlow

sintestinalcarbohydrate

digestion/absorption

cNohypoglycem

iacGen

erallymodestHbA1cefficacy

Moderate

cMiglitol

c↓P

ostprandialglucose

excursions

c?↓CVDeven

ts(STO

P-NIDDM)

cGastrointestinalsideeffects

(flatulence,d

iarrhea)

cNonsystem

ic

cFreq

uen

tdosingsched

ule

DPP

-4inhibitors

cSitagliptin

InhibitsDPP

-4activity,

increasingpostprandial

active

incretin

(GLP-1,GIP)

concentrations

c↑Insulin

secretion

(glucose-dep

enden

t)cNohypoglycem

iacAngioedem

a/urticariaandother

immune-mediatedderm

atologicaleffects

High

cVildagliptin†

c↓Glucagonsecretion

(glucose-dep

enden

t)

cWelltolerated

c?Acute

pancreatitis

cSaxagliptin

cLinagliptin

c?↑Heartfailure

hospitalizations

cAlogliptin

Bile

acid

sequestrants

cColesevelam

Bindsbile

acidsin

intestinaltract,increasing

hep

aticbile

acid

production

c?↓Hep

aticglucose

production

cNohypoglycem

iacGen

erallymodestHbA1cefficacy

High

c?↑Incretin

levels

c↓LD

L-C

cConstipation

c↑Triglycerides

cMay

↓absorptionofother

med

ications

Con

tinu

edon

p.14

3

142 Position Statement Diabetes Care Volume 38, January 2015

Table

1—Continued

Class

Compound(s)

Cellularmechanism(s)

Prim

aryph

ysiologicalaction(s)

Advantages

Disad

vantages

Cost*

Dopam

ine-2

agonists

cBromocriptine(quickrelease)§

Activates

dopam

inergic

receptors

cModulateshypothalam

icregu

lationofmetabolism

cNohypoglycem

iacGen

erallymodestHbA1cefficacy

High

cDizziness/syncope

c↑Insulin

sensitivity

c?↓CVDeven

ts(CyclosetSafety

Trial)

cNau

sea

cFatigue

cRhinitis

SGLT2inhibitors

cCan

aglifl

ozin

InhibitsSG

LT2in

the

proximalnep

hron

cBlocksglucose

reab

sorption

bythekidney,increasing

glucosuria

cNohypoglycem

iacGen

itourinaryinfections

High

cDap

aglifl

ozin‡

c↓Weigh

tcPo

lyuria

cEm

paglifl

ozin

cVolumedep

letion/hypotension/dizziness

c↓Bloodpressure

c↑LD

L-C

cEffectiveat

allstages

ofT2DM

c↑Creatinine(transien

t)

GLP-1

receptor

agonists

cExen

atide

Activates

GLP-1

receptors

c↑Insulin

secretion(glucose-

dep

enden

t)cNohypoglycem

iacGastrointestinalsideeffects(nau

sea/

vomiting/diarrhea)

High

cExen

atideextended

release

c↓Glucagonsecretion

(glucose-dep

enden

t)c↑Heartrate

cLiraglutide

c↓Weigh

t

c?Acute

pancreatitis

cAlbiglutide

cSlowsgastricem

ptying

c↓Po

stprandialglucose

excursions

cC-cellh

yperplasia/med

ullary

thyroid

tumorsin

anim

als

cLixisenatide†

c↑Satiety

c↓Somecardiovascular

risk

factors

cInjectab

lecDulaglutide

cTrainingrequirem

ents

Amylin

mim

etics

cPram

lintide§

Activates

amylin

receptors

c↓Glucagonsecretion

c↓Postprandialglucose

excursions

cGen

erallymodestHbA1cefficacy

High

c↑Satiety

c↓Weigh

tcGastrointestinalsideeffects(nau

sea/

vomiting)

cHypoglycem

iaunless

insulin

dose

issimultan

eouslyreduced

cSlowsgastricem

ptying

cInjectab

lecFreq

uen

tdosingsched

ule

cTrainingrequirem

ents

Insulins

cRap

id-actinganalogs

Activates

insulin

receptors

c↑Glucose

disposal

cNearlyuniversal

response

cHypoglycem

iaVariable#

-Lispro

-Aspart

-Glulisine

cShort-acting

-Human

Regular

cInterm

ediate-acting

cWeightgain

-Human

NPH

cBasalinsulin

analogs

c↓Hep

aticglucose

production

c↓Microvascularrisk

(UKP

DS)

c?Mitogeniceffects

-Glargine

cInjectab

le

-Detem

ir

cTrainingrequirem

ents

-Degludec†

cOther

cTheo

retically

unlim

ited

efficacy

cPatien

treluctan

ce

cPrem

ixed

(severaltypes)

CVD,cardiovasculardisease;GIP,glucose-dep

enden

tinsulinotropicpep

tide;

HDL-C,H

DLcholesterol;LD

L-C,LDLcholesterol;MI,myocardialinfarction;PP

AR-g,p

eroxisomeproliferator–activatedreceptorg;

PROactive,Prospective

PioglitazoneClinicalTrialinMacrovascularEven

ts(26);STOP-NIDDM,Studyto

Preven

tNon-Insulin-Dep

enden

tDiabetes

Mellitus(60);T2DM,type2diabetes

mellitus;UKP

DS,UK

Prospective

Diabetes

Study(4,61).C

yclosettrialofquick-releasebromocriptine(62).*Costisbased

onlowest-pricedmem

ber

oftheclass(see

Supplemen

tary

Data).†Notlicen

sedintheU.S.‡Initialconcerns

regardingbladder

cancerrisk

aredecreasingaftersubsequen

tstudy.§N

otlicen

sedin

Europefortype2diabetes.#C

ostishighlydep

enden

tontype/brand(analogs

.human

insulins)anddosage.

care.diabetesjournals.org Inzucchi and Associates 143

Alogliptin, another DPP-4 inhibitor, alsodid not have any demonstrable cardio-vascular excess risk over an even shorterperiod (18 months) in high-risk patients(30). A wider database interrogation indi-cated no signal for cardiovascular diseaseor heart failure (30,31). Several other trialsare underway, and until the results ofthese are reported, this class should prob-ably be used cautiously, if at all, in patientswith preexisting heart failure.One area of concern with this class,

as well as the other incretin-basedcategory, the glucagon-like peptide 1(GLP-1) receptor agonists, has beenpancreatic safetydboth regardingpossible pancreatitis and pancreaticneoplasia. The prescribing guidelinesfor these drugs include cautions aboutusing them in individuals with a priorhistory of pancreatitis. While this isreasonable, emerging data from largeobservational data sets (32), as well asfrom two large cardiovascular trialswith DPP-4 inhibitors (28–30), havefound no statistically increased ratesof pancreatic disease.Generally speaking, the use of any

drug in patients with type 2 diabetesmust balance the glucose-lowering effi-cacy, side-effect profiles, anticipation ofadditional benefits, cost, and otherpractical aspects of care, such as dosingschedule and requirements for glucosemonitoring. The patientdwho is obvi-ously the individual most affected bydrug choicedshould participate in ashared decision-making process regard-ing both the intensiveness of blood glu-cose control and which medications areto be selected.

IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES

Initial Drug Therapy (See Fig. 2)Metformin remains the optimal drugfor monotherapy. Its low cost, provensafety record, weight neutrality, and pos-sible benefits on cardiovascular outcomeshave secured its place as the favored ini-tial drug choice. There is increasing evi-dence that the current cut-off points forrenal safety in the U.S. (contraindicated ifserum creatinine $1.5 mg/dL [$133mmol/L] in men or 1.4 mg/dL [124mmol/L] in women)may be overly restric-tive (33). Accordingly, there are calls torelax prescribing polices to extend theuse of this importantmedication to thosewith mild–moderate, but stable, chronickidney disease (CKD) (34–36). Many

practitioners would continue to prescribemetformin even when the eGFR fallsto less than 45–60 mL/min/1.73 m2, per-haps with dose adjustments to accountfor reduced renal clearance of the com-pound. One criterion for stopping thedrug is an eGFR of,30 mL/min/1.73 m2

(34,37,38). Of course, any use in patientswith CKD mandates diligent follow-up ofrenal function.

In circumstances where metformin iscontraindicated or not tolerated, one ofthe second-line agents (see below) maybe used, although the choices becomemore limited if renal insufficiency is thereason metformin is being avoided. Inthese circumstances it is unwise to usesulfonylureas, particularly glyburide(known as glibenclamide in Europe), be-cause of the risk of hypoglycemia. DPP-4inhibitors are probably a preferablechoice, although, with the exception oflinagliptin (39), dosage adjustments arerequired.

Advancing to Dual Combinationand Triple Combination Therapy(See Fig. 2)While the SGLT2 inhibitors are approvedasmonotherapy, they aremainly used incombination with metformin and/orother agents (19). Given their demon-strated efficacy and clinical experienceto date, they are reasonable options assecond-line or third-line agents (40–42)(Fig. 2). Similar to most combinations,efficacy may be less than additivewhen SGLT2 inhibitors are used in com-bination with DPP-4 inhibitors (43).There are no data available on the useof SGLT2 inhibitors in conjunction withGLP-1 receptor agonists; an evidence-based recommendation for this combi-nation cannot be made at this time.

As noted in the original position state-ment, initial combination therapy withmetformin plus a second agent may al-low patients to achieve HbA1c targetsmore quickly than sequential therapy.Accordingly, such an approach may beconsidered in those individuals withbaseline HbA1c levels well above target,who are unlikely to successfully attaintheir goal using monotherapy. A reason-able threshold HbA1c for this consider-ation is $9% ($75 mmol/mol). Ofcourse, there is no proven overall ad-vantage to achieving a glycemic targetmore quickly by a matter of weeks oreven months. Accordingly, as long as

close patient follow-up can be ensured,prompt sequential therapy is a reason-able alternative, even in those withbaseline HbA1c levels in this range.

Combination Injectable Therapy (SeeFigs. 2 and 3)In certain patients, glucose control re-mains poor despite the use of three anti-hyperglycemic drugs in combination.With long-standing diabetes, a signifi-cant diminution in pancreatic insulin se-cretory capacity dominates the clinicalpicture. In any patient not achieving anagreed HbA1c target despite intensivetherapy, basal insulin should be consid-ered an essential component of thetreatment strategy. After basal insulin(usually in combination with metforminand sometimes an additional agent), the2012 position statement endorsed theaddition of one to three injections of arapid-acting insulin analog dosed beforemeals. As an alternative, the statementmentioned that, in selected patients,simpler (but somewhat less flexible)premixed formulations of intermediate-and short/rapid-acting insulins in fixedratios could also be considered (44).Over the past 3 years, however, the ef-fectiveness of combining GLP-1 receptoragonists (both shorter-acting and newerweekly formulations) with basal insulinhas been demonstrated, with moststudies showing equal or slightly supe-rior efficacy to the addition of prandialinsulin, and with weight loss and lesshypoglycemia (45–47). The availabledata now suggest that either a GLP-1receptor agonist or prandial insulincould be used in this setting, with theformer arguably safer, at least forshort-term outcomes (45,48,49). Ac-cordingly, in those patients on basal in-sulin with one or more oral agentswhose diabetes remains uncontrolled,the addition of a GLP-1 receptor ago-nist or mealtime insulin could beviewed as a logical progression of thetreatment regimen, the former per-haps a more attractive option in moreobese individuals or in those who maynot have the capacity to handle thecomplexities of a multidose insulinregimen. Indeed, there is increasingevidence for and interest in this ap-proach (50). In those patients whodo not respond adequately to the ad-dition of a GLP-1 receptor agonist tobasal insulin, mealtime insulin in a

144 Position Statement Diabetes Care Volume 38, January 2015

combined “basal–bolus” strategy shouldbe used instead (51).In selected patients at this stage

of disease, the addition of an SGLT2

inhibitor may further improve controland reduce the amount of insulin re-quired (52). This is particularly an issuewhen large doses of insulin are required

in obese, highly insulin-resistant pa-tients. Another, older, option, the addi-tion of a TZD (usually pioglitazone), alsohas an insulin-sparing effect and may

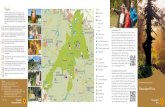

Figure 2—Antihyperglycemic therapy in type 2 diabetes: general recommendations. Potential sequences of antihyperglycemic therapy for patientswith type 2 diabetes are displayed, the usual transition being vertical, from top to bottom (although horizontal movement within therapy stages isalso possible, depending on the circumstances). In most patients, begin with lifestyle changes; metformin monotherapy is added at, or soon after,diagnosis, unless there are contraindications. If the HbA1c target is not achieved after ;3 months, consider one of the six treatment optionscombined with metformin: a sulfonylurea, TZD, DPP-4 inhibitor, SGLT2 inhibitor, GLP-1 receptor agonist, or basal insulin. (The order in the chart, notmeant to denote any specific preference, was determined by the historical availability of the class and route of administration, with injectables to theright and insulin to the far right.) Drug choice is based on patient preferences as well as various patient, disease, and drug characteristics, with thegoal being to reduce glucose concentrations while minimizing side effects, especially hypoglycemia. The figure emphasizes drugs in common use inthe U.S. and/or Europe. Rapid-acting secretagogues (meglitinides) may be used in place of sulfonylureas in patients with irregular meal schedules orwho develop late postprandial hypoglycemia on a sulfonylurea. Other drugs not shown (a-glucosidase inhibitors, colesevelam, bromocriptine,pramlintide) may be tried in specific situations (where available), but are generally not favored because of their modest efficacy, the frequency ofadministration, and/or limiting side effects. In patients intolerant of, or with contraindications for, metformin, consider initial drug from otherclasses depicted under “Dual therapy” and proceed accordingly. In this circumstance, while published trials are generally lacking, it is reasonable toconsider three-drug combinations that do not include metformin. Consider initiating therapy with a dual combination when HbA1c is $9% ($75mmol/mol) to more expeditiously achieve target. Insulin has the advantage of being effective where other agents may not be and should beconsidered a part of any combination regimen when hyperglycemia is severe, especially if the patient is symptomatic or if any catabolic features(weight loss, any ketosis) are evident. Consider initiating combination injectable therapy with insulin when blood glucose is $300–350 mg/dL($16.7–19.4 mmol/L) and/or HbA1c $10–12% ($86–108 mmol/mol). Potentially, as the patient’s glucose toxicity resolves, the regimen can besubsequently simplified. DPP-4-i, DPP-4 inhibitor; fxs, fractures; GI, gastrointestinal; GLP-1-RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; GU, genitourinary; HF, heartfailure; Hypo, hypoglycemia; SGLT2-i, SGLT2 inhibitor; SU, sulfonylurea. *See Supplementary Data for description of efficacy categorization.†Consider initial therapy at this stage when HbA1c is $9% ($75 mmol/mol). ‡Consider initial therapy at this stage when blood glucose is $300–350mg/dL ($16.7–19.4 mmol/L) and/or HbA1c$10–12% ($86–108mmol/mol), especially if patient is symptomatic or if catabolic features (weightloss, ketosis) are present, in which case basal insulin1mealtime insulin is the preferred initial regimen. §Usually a basal insulin (e.g., NPH, glargine,detemir, degludec).

care.diabetesjournals.org Inzucchi and Associates 145

also reduce HbA1c (53,54), but at theexpense of weight gain, fluid retention,and increased risk of heart failure. So,if used at this stage, low doses are

advisable and only with very carefulmonitoring of the patient.

Concentrated insulins (e.g., U-500Regular) also have a role in those

individuals requiring very large dosesof insulin per day, in order to minimizeinjection volume (55). However, thesemust be carefully prescribed, with

Figure 3—Approach to starting and adjusting insulin in type 2 diabetes. This figure focuses mainly on sequential insulin strategies, describing thenumber of injections and the relative complexity and flexibility of each stage. Basal insulin alone is the most convenient initial regimen, beginningat 10 U or 0.1–0.2 U/kg, depending on the degree of hyperglycemia. It is usually prescribed in conjunction with metformin and possibly oneadditional noninsulin agent. When basal insulin has been titrated to an acceptable fasting blood glucose but HbA1c remains above target, considerproceeding to “Combination injectable therapy” (see Fig. 2) to cover postprandial glucose excursions. Options include adding a GLP-1 receptoragonist (not shown) or a mealtime insulin, consisting of one to three injections of a rapid-acting insulin analog* (lispro, aspart, or glulisine)administered just before eating. A less studied alternative, transitioning from basal insulin to a twice daily premixed (or biphasic) insulin analog*(70/30 aspart mix, 75/25 or 50/50 lispro mix) could also be considered. Once any insulin regimen is initiated, dose titration is important, withadjustments made in both mealtime and basal insulins based on the prevailing blood glucose levels, with knowledge of the pharmacodynamic profileof each formulation used (pattern control). Noninsulin agents may be continued, although sulfonylureas, DPP-4 inhibitors, and GLP-1 receptoragonists are typically stopped once insulin regimens more complex than basal are utilized. In refractory patients, however, especially in thoserequiring escalating insulin doses, adjunctive therapy with metformin and a TZD (usually pioglitazone) or SGLT2 inhibitor may be helpful in improvingcontrol and reducing the amount of insulin needed. Comprehensive education regarding self-monitoring of blood glucose, diet, and exercise and theavoidance of, and response to, hypoglycemia are critically important in any insulin-treated patient. FBG, fasting blood glucose; GLP-1-RA, GLP-1receptor agonist; hypo, hypoglycemia; mod., moderate; PPG, postprandial glucose; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose; #, number.*Regular human insulin and human NPH-Regular premixed formulations (70/30) are less costly alternatives to rapid-acting insulin analogs andpremixed insulin analogs, but their pharmacodynamic profiles make them suboptimal for the coverage of postprandial glucose excursions. †A lesscommonly used and more costly alternative to basal–bolus therapy with multiple daily injections in type 2 diabetes is continuous subcutaneousinsulin infusion (insulin pump). ‡In addition to the suggestions provided for determining the starting dose of mealtime insulin under “basal–bolus,”another method consists of adding up the total current daily insulin dose and then providing one-half of this amount as basal and one-half asmealtime insulin, the latter split evenly between three meals.

146 Position Statement Diabetes Care Volume 38, January 2015

meticulous communication with bothpatient and pharmacist regarding properdosing instructions.Practitioners should also consider the

significant expense and additional com-plexity and costs of multiple combina-tions of glucose-lowering medications.Overly burdensome regimens shouldbe avoided. The inability to achieve gly-cemic targets with an increasingly con-voluted regimen should prompt apragmatic reassessment of the HbA1ctarget or, in the very obese, consider-ation of nonpharmacological interven-tions, such as bariatric surgery.Of course, nutritional counseling and

diabetes self-management educationare integral parts of any therapeuticprogram throughout the disease course.These will ensure that the patient hasaccess to information on methods to re-duce, where possible, the requirementsfor pharmacotherapy, as well as tosafely monitor and control blood glu-cose levels.Clinicians should also be wary of the

patient with latent autoimmune diabe-tes of adulthood (LADA), which may beidentified by measuring islet antibodies,such as those against GAD65 (56). Al-though control with oral agents is pos-sible for a variable period of time, theseindividuals, who are typically but not al-ways lean, develop insulin requirementsfaster than those with typical type 2 di-abetes (57) and progressively manifestmetabolic changes similar to those seenin type 1 diabetes. Ultimately, they areoptimally treated with a regimen con-sisting of multiple daily injections ofinsulin, ideally using a basal–bolus ap-proach (or an insulin pump).Figure 3 has been updated to include

proposed dosing instructions for thevarious insulin strategies, including theaddition of rapid-acting insulin analogsbefore meals or the use of premixed in-sulin formulations.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

As emphasized in the original positionstatement, optimal treatment of type 2diabetes must take into account the var-ious comorbidities that are frequentlyencountered in patients, particularly asthey age. These include coronary arterydisease, heart failure, renal and liverdisease, dementia, and increasing pro-pensity to (and greater likelihoodof experiencing untoward outcomes

from) hypoglycemia. There are fewnew data to further this discussion. Asmentioned, new concerns about DPP-4inhibitors and heart failure and the is-sues concerning SGLT2 inhibitors andrenal status should be taken into con-sideration (29). Finally, cost can be animportant consideration in drug selec-tion. As the prices of newer medicationscontinue to increase, practitionersshould take into account patient (andsocietal) resources and determinewhen less costly, generic productsmight be appropriately used.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

More long-term data regarding thecardiovascular impact of our glucose-lowering therapies will be availableover the next 1–3 years. Informationfrom these trials will further assist us inoptimizing treatment strategies. A largecomparative effectiveness study in theU.S. is now assessing long-termoutcomeswith multiple agents after metforminmonotherapy, but results are not antici-pated until at least 2020 (58).

The recommendations in this positionstatement will obviously need to be up-dated in future years in order to providethe best and most evidence-based rec-ommendations for patients with type 2diabetes.

Acknowledgments. This position statementwas written by joint request of the ADA and theEASD Executive Committees, which have ap-proved the final document. The process in-volved wide literature review, one face-to-facemeeting of the Writing Group, and multiplerevisions via e-mail communications. We grate-fully acknowledge the following experts whoprovided critical review of a draft of this update:James Best, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine,Singapore; Henk Bilo, Isala Clinics, Zwolle, theNetherlands; Andrew Boulton, Manchester Uni-versity, Manchester, U.K.; Paul Callaway, Uni-versity of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita,Wichita, KS; Bernard Charbonnel, University ofNantes, Nantes, France; Stephen Colagiuri, TheUniversity of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; LeszekCzupryniak, Medical University of Lodz, Lodz,Poland; Margo Farber, University of MichiganHealth System and College of Pharmacy, AnnArbor, MI; Richard Grant, Kaiser PermanenteNorthern California, Oakland, CA; FaramarzIsmail-Beigi, Case Western Reserve UniversitySchool of Medicine/Cleveland VA Medical Cen-ter, Cleveland, OH; Darren McGuire, Universityof Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas,TX; Julio Rosenstock, Dallas Diabetes and En-docrine Center at Medical City, Dallas, TX;Geralyn Spollett, Yale University School of Med-icine, New Haven, CT; Agathocles Tsatsoulis,

University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece; DeborahWexler, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston,MA; Bernard Zinman, Lunenfeld-TanenbaumResearch Institute, University of Toronto andMount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada. The finaldraft was also peer-reviewed and approved bythe Professional Practice Committee of the ADAand the Panel on Guidelines and Statements ofthe EASD.Funding. The face-to-face meeting was sup-ported by the EASD. D.R. Matthews acknowl-edges support from the National Institute forHealth Research.Duality of Interest. During the past 12months, the following relationships with com-panies whose products or services directlyrelate to the subject matter in this documentare declared:

R.M. Bergenstal: membership of scientific advi-sory board, consultation services or clinicalresearch support with AstraZeneca, BoehringerIngelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck & Co., Novo Nordisk,Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda (all under contractswith his employer). Inherited stock in Merck &Co. (previously held by family)

J.B. Buse: research and consulting withAstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eli Lilly and Company;Johnson & Johnson; Merck & Co., Inc.; NovoNordisk; Sanofi; and Takeda (all under contractswith his employer)

E. Ferrannini: membership on scientific advisoryboards or speaking engagements for Merck Sharp&Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline,Bristol-Myers Squibb/AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly & Co.,Novartis, and Sanofi. Research grant supportfrom Eli Lilly & Co. and Boehringer Ingelheim

S.E. Inzucchi: membership on scientific/re-search advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim,AstraZeneca, Intarcia, Lexicon, Merck & Co., andNovo Nordisk. Research supplies to Yale Univer-sity from Takeda. Participation in medical educa-tional projects, for which unrestricted fundingfrom Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Merck& Co. was received by Yale University

D.R. Matthews: has received advisory boardconsulting fees or honoraria from NovoNordisk, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Johnson &Johnson, and Servier. He has research supportfrom Johnson & Johnson. He has lectured forNovo Nordisk, Servier, and Novartis

M. Nauck: research grants to his institutionfrom Berlin-Chemie/Menarini, Eli Lilly, MerckSharp & Dohme, Novartis, AstraZeneca,Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, LillyDeutschland, and Novo Nordisk for participa-tion in multicenter clinical trials. He has re-ceived consulting fees and/or honoraria formembership in advisory boards and/or honorariafor speaking from Amylin, AstraZeneca, Berlin-Chemie/Menarini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Diartis Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly,F. Hoffmann-La Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Hanmi,Intarcia Therapeutics, Janssen, Merck Sharp &Dohme, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Takeda,and Versartis, including reimbursement for travelexpenses

A.L. Peters: has received lecturing fees and/orfees for ad hoc consulting from AstraZeneca,Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Eli Lilly, NovoNordisk, Sanofi, and Takeda

care.diabetesjournals.org Inzucchi and Associates 147

A. Tsapas: has received research support (to hisinstitution) from Novo Nordisk and BoehringerIngelheim and lecturing fees from Novartis, EliLilly, and Boehringer Ingelheim

R.Wender: declares he has no duality of interestAuthor Contributions. All the named WritingGroup authors contributed substantially to thedocument. All authors supplied detailed inputand approved the final version. S.E. Inzucchi andD.R. Matthews directed, chaired, and coordi-nated the input with multiple e-mail exchangesbetween all participants.

References1. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al.Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabe-tes: a patient-centered approach. Positionstatement of the American Diabetes Associa-tion (ADA) and the European Association forthe Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care2012;35:1364–13792. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al.Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 dia-betes: a patient-centered approach. Positionstatement of the American Diabetes Associa-tion (ADA) and the European Association forthe Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia2012;55:1577–15963. Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Associa-tion of glycaemia with macrovascular and mi-crovascular complications of type 2 diabetes(UKPDS 35): prospective observational study.BMJ 2000;321:405–4124. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sul-phonylureas or insulin compared with conven-tional treatment and risk of complications inpatients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lan-cet 1998;352:837–8535. Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, MatthewsDR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glu-cose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med2008;359:1577–15896. Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al.;Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabe-tes Study Group. Effects of intensive glucoselowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med2008;358:2545–25597. Vasilakou D, Karagiannis T, Athanasiadou E,et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitorsfor type 2 diabetes: a systematic review andmeta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:262–2748. Stenlof K, Cefalu WT, Kim KA, et al. Efficacyand safety of canagliflozin monotherapy in sub-jects with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequatelycontrolled with diet and exercise. DiabetesObes Metab 2013;15:372–3829. Schernthaner G, Gross JL, Rosenstock J, et al.Canagliflozin compared with sitagliptin for pa-tients with type 2 diabetes who do not haveadequate glycemic control with metforminplus sulfonylurea: a 52-week randomized trial.Diabetes Care 2013;36:2508–251510. Roden M, Weng J, Eilbracht J, et al.; EMPA-REG MONO trial investigators. Empagliflozinmonotherapy with sitagliptin as an active com-parator in patients with type 2 diabetes: a ran-domised, double-blind, placebo-controlled,phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2013;1:208–21911. Nauck MA, Del Prato S, Meier JJ, et al. Da-pagliflozin versus glipizide as add-on therapy in

patients with type 2 diabetes who have inade-quate glycemic control withmetformin: a random-ized, 52-week, double-blind, active-controllednoninferiority trial. Diabetes Care 2011;34:2015–202212. CefaluWT, Leiter LA, Yoon KH, et al. Efficacyand safety of canagliflozin versus glimepiride inpatients with type 2 diabetes inadequately con-trolled with metformin (CANTATA-SU): 52 weekresults from a randomised, double-blind, phase3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2013;382:941–95013. Bakris GL, Fonseca VA, Sharma K, WrightEM. Renal sodium-glucose transport: role in di-abetes mellitus and potential clinical implica-tions. Kidney Int 2009;75:1272–127714. Ferrannini E, Solini A. SGLT2 inhibition indiabetes mellitus: rationale and clinical pros-pects. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012;8:495–50215. Rosenstock J, Seman LJ, Jelaska A, et al.Efficacy and safety of empagliflozin, a sodiumglucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, asadd-on to metformin in type 2 diabetes withmild hyperglycaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab2013;15:1154–116016. Chino Y, Samukawa Y, Sakai S, et al. SGLT2inhibitor lowers serum uric acid through alter-ation of uric acid transport activity in renal tu-bule by increased glycosuria. Biopharm DrugDispos 2014;35:391–40417. Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Fung A, et al. Genitalmycotic infections with canagliflozin, a sodiumglucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, in patientswith type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pooled analysisof clinical studies. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:1109–111918. Johnsson KM, Ptaszynska A, Schmitz B, SuggJ, Parikh SJ, List JF. Vulvovaginitis and balanitis inpatients with diabetes treated with dapagliflo-zin. J Diabetes Complications 2013;27:479–48419. Monami M, Nardini C, Mannucci E. Efficacyand safety of sodium glucose co-transport-2 in-hibitors in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis ofrandomized clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab2014;16:457–46620. Weir MR, Kline I, Xie J, Edwards R, Usiskin K.Effect of canagliflozin on serum electrolytes inpatients with type 2 diabetes in relation to es-timated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). CurrMed Res Opin 2014;30:1759–176821. FDA briefing document. Invokana (canagli-flozin) tablets. [NDA 204042], U.S. Food andDrug Administration, 201322. Neal B, Perkovic V, de Zeeuw D, et al. Ratio-nale, design, and baseline characteristics of theCanagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study(CANVAS)–a randomized placebo-controlled tri-al. Am Heart J 2013;166:217–223.e1123. Balaji V, Seshiah V, Ashtalakshmi G,Ramanan SG, Janarthinakani M. A retrospectivestudy on finding correlation of pioglitazone andincidences of bladder cancer in the Indian pop-ulation. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2014;18:425–42724. Kuo HW, Tiao MM, Ho SC, Yang CY. Piogli-tazone use and the risk of bladder cancer. Kaoh-siung J Med Sci 2014;30:94–9725. Wei L, MacDonald TM,Mackenzie IS. Piogli-tazone and bladder cancer: a propensity scorematched cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;75:254–25926. Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ,et al.; PROactive investigators. Secondary

prevention of macrovascular events in patientswith type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study(PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial InmacroVascular Events): a randomised con-trolled trial. Lancet 2005;366:1279–128927. Colhoun HM, Livingstone SJ, Looker HC,et al.; Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epi-demiology Group. Hospitalised hip fracture riskwith rosiglitazone and pioglitazone use com-pared with other glucose-lowering drugs. Dia-betologia 2012;55:2929–293728. Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al.;SAVOR-TIMI 53 Steering Committee and In-vestigators. Saxagliptin and cardiovascularoutcomes in patients with type 2 diabetesmellitus. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1317–132629. Scirica BM, Braunwald E, Raz I, et al.; SAVOR-TIMI 53 Steering Committee and Investigators.Heart failure, saxagliptin and diabetes mellitus:observations from the SAVOR - TIMI 53 random-ized trial. Circulation. 4 September 2014 [Epubahead of print]30. White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, et al.;EXAMINE Investigators. Alogliptin after acutecoronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabe-tes. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1327–133531. White WB, Pratley R, Fleck P, et al. Cardio-vascular safety of the dipetidyl peptidase-4 in-hibitor alogliptin in type 2 diabetes mellitus.Diabetes Obes Metab 2013;15:668–67332. Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreaticsafety of incretin-based drugsdFDA and EMAassessment. N Engl J Med 2014;370:794–79733. Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA,Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic ac-idosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetesmellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;Apr 14(4):CD00296734. Lipska KJ, Bailey CJ, Inzucchi SE. Use of met-formin in the setting of mild-to-moderate renalinsufficiency. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1431–143735. Nye HJ, HerringtonWG.Metformin: the saf-est hypoglycaemic agent in chronic kidney dis-ease? Nephron Clin Pract 2011;118:c380–c38336. Pilmore HL. Review: metformin: potentialbenefits and use in chronic kidney disease. Ne-phrology (Carlton) 2010;15:412–41837. Lu WR, Defilippi J, Braun A. Unleash met-formin: reconsideration of the contraindicationin patients with renal impairment. Ann Phar-macother 2013;47:1488–149738. National Institute for Health and Care Ex-cellence. Type 2 diabetes: the management oftype 2 diabetes [CG87]. London, NICE, 200939. Groop PH, Del Prato S, Taskinen MR, et al.Linagliptin treatment in subjects with type 2 di-abetes with and without mild-to-moderate re-nal impairment. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014;16:560–56840. Phung OJ, Sobieraj DM, Engel SS, RajpathakSN. Early combination therapy for the treat-ment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic re-view and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab2014;16:410–41741. Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, PaganoG. A novel approach to control hyperglycemia intype 2 diabetes: sodium glucose co-transport(SGLT) inhibitors: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. AnnMed 2012;44:375–39342. Goring S, Hawkins N, Wygant G, et al. Dapa-gliflozin compared with other oral anti-diabetes

148 Position Statement Diabetes Care Volume 38, January 2015

treatments when added to metformin mono-therapy: a systematic review and networkmeta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014;16:433–44243. Bosi E, Ellis GC, Wilson CA, Fleck PR.Alogliptin as a third oral antidiabetic drug inpatients with type 2 diabetes and inadequateglycaemic control on metformin and pioglita-zone: a 52-week, randomized, double-blind,active-controlled, parallel-group study. Dia-betes Obes Metab 2011;13:1088–109644. Holman RR, Thorne KI, Farmer AJ, et al.; 4-TStudy Group. Addition of biphasic, prandial, orbasal insulin to oral therapy in type 2 diabetes. NEngl J Med 2007;357:1716–173045. Eng C, Kramer CK, Zinman B, Retnakaran R.Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist andbasal insulin combination treatment for themanagement of type 2 diabetes: a systematicreview and meta-analysis. Lancet. 11 Septem-ber 2014 [Epub ahead of print]46. Diamant M, Nauck MA, Shaginian R, et al.;4B Study Group. Glucagon-like peptide 1 recep-tor agonist or bolus insulin with optimized basalinsulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37:2763–277347. Buse JB, Bergenstal RM, Glass LC, et al. Useof twice-daily exenatide in basal insulin-treatedpatients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized,controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:103–11248. Balena R, Hensley IE, Miller S, Barnett AH.Combination therapy with GLP-1 receptor ago-nists and basal insulin: a systematic review ofthe literature. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013;15:485–50249. Charbonnel B, Bertolini M, Tinahones FJ,Domingo MP, Davies M. Lixisenatide plus basal

insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus:a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications. 18July 2014 [Epub ahead of print]50. LaneW,Weinrib S, Rappaport J, Hale C. Theeffect of addition of liraglutide to high-doseintensive insulin therapy: a randomized pro-spective trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014;16:827–83251. Davidson MB, Raskin P, Tanenberg RJ,Vlajnic A, Hollander P. A stepwise approach toinsulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetesmellitus and basal insulin treatment failure. En-docr Pract 2011;17:395–40352. Rosenstock J, Jelaska A, Frappin G, et al.;EMPA-REG MDI Trial Investigators. Improvedglucose control with weight loss, lower insulindoses, and no increased hypoglycemia with em-pagliflozin added to titratedmultiple daily injec-tions of insulin in obese inadequately controlledtype 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37:1815–182353. Charbonnel B, DeFronzo R, Davidson J,et al.; PROactive investigators. Pioglitazoneuse in combination with insulin in the prospec-tive pioglitazone clinical trial in macrovascularevents study (PROactive19). J Clin EndocrinolMetab 2010;95:2163–217154. Shah PK,Mudaliar S, Chang AR, et al. Effectsof intensive insulin therapy alone and in combi-nation with pioglitazone on body weight, com-position, distribution and liver fat content inpatients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes ObesMetab 2011;13:505–51055. Davidson MB, Navar MD, Echeverry D,Duran P. U-500 regular insulin: clinical experi-ence and pharmacokinetics in obese, severelyinsulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Diabe-tes Care 2010;33:281–283

56. Hawa MI, Buchan AP, Ola T, et al. LADA andCARDS: a prospective study of clinical outcomein established adult-onset autoimmune diabe-tes. Diabetes Care 2014;37:1643–164957. Zampetti S, Campagna G, Tiberti C, et al.High GADA titer increases the risk of insulin re-quirement in LADA: a 7-years of follow-up(NIRAD Study 7). Eur J Endocrinol. 11 September2014 [Epub ahead of print]58. Nathan DM, Buse JB, Kahn SE, et al.; GRADEStudy Research Group. Rationale and design ofthe glycemia reduction approaches in diabetes:a comparative effectiveness study (GRADE). Di-abetes Care 2013;36:2254–226159. Ismail-Beigi F, Moghissi E, Tiktin M, HirschIB, Inzucchi SE, Genuth S. Individualizing glyce-mic targets in type 2 diabetes mellitus: implica-tions of recent clinical trials. Ann Intern Med2011;154:554–55960. Chiasson JL, Gomis R, HanefeldM, Josse RG,Karasik A, Laakso M; STOP-NIDDM TrialResearch Group. The STOP-NIDDM Trial: an in-ternational study on the efficacy of an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor to prevent type 2 diabetesin a populationwith impaired glucose tolerance:rationale, design, and preliminary screeningdata. Diabetes Care 1998;21:1720–172561. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose controlwith metformin on complications in overweightpatients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lan-cet 1998;352:854–86562. Gaziano JM, Cincotta AH, O’Connor CM,et al. Randomized clinical trial of quick-releasebromocriptine among patients with type 2diabetes on overall safety and cardiovascularoutcomes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1503–1508

care.diabetesjournals.org Inzucchi and Associates 149