MAESTROS DE OBRAS · 2013-02-14 · 1 Rafael Guastavino Moreno, Maestro de Obras in Spain: from the...

Transcript of MAESTROS DE OBRAS · 2013-02-14 · 1 Rafael Guastavino Moreno, Maestro de Obras in Spain: from the...

1

Rafael Guastavino Moreno, Maestro de Obras in Spain: from the Tailor

Shop to the Privilege of Invention

Miguel Rotaeche

Practicing architect

Formidable was the river until a ford was found.

(Baltasar Gracián, 1601-1658)

What sort of training enabled Rafael Guastavino Moreno (1842-1908) to undertake such

important projects early in his career? The answers are many, and they lie not only in

his training. In the first place, it is well established that, although modest, the

coursework he completed at the time to earn the title of Maestro de Obras carried great

prestige. Its practical nature and immediate application in the construction of 19th-

century Barcelona are a fact. Also beyond question were Guastavino’s personal talent

and astuteness, and the fact that his family contacts led to most of his commissions. But

there is still a considerable degree of uncertainty concerning the authorship of his work.

These four questions—studies, talent, contacts and authorship—will be addressed in

this paper.

______________________

The course of studies Guastavino pursued in the second half of the 19th century was

called Maestro de Obras, a program created in the mid-18th century by the Academy of

Fine Arts in Madrid at the same time as Architecture.

Until that time, and ever since the Middle Ages, a maestro de obras had been a

contractor, generally a stonemason, who secured construction projects, purchased

materials, assigned jobs to his workers and paid salaries (Alonso 1991, 52). When the

two professional degree programs in the field of construction, architect and maestro de

obras, were created in the mid-18th century, the latter was “a second-class architect.”

This was a product of the hierarchical structure of the ancien régime in Spain. The

difference was that the so-called “academic” maestro de obras was only allowed to

design private buildings, whereas an architect could work on buildings of all types. This

way architects were awarded commissions directly connected to the ancien régime, i.e.,

mansions, churches and so forth, whereas a maestro de obras could only design

buildings of a more practical nature such as residential, industrial or agricultural

structures.

We can easily imagine the consequences of this distinction in the 19th century: the

maestros de obras went on to design most of the houses and industrial buildings, as

there were not enough architects in Spain to meet the demand. According to Juan

Bautista Peyronnet, assistant director of the School of Architecture in Madrid, (Basurto

2

1999, 22) in 1869 there were less than 400 architects in Spain and many of them were

not actively practicing. The shortage of maestros de obras was acute in every city in

Spain. In 1832 there were 11 architects and four maestros de obras in Barcelona; in

1852, the numbers grew respectively to 24 and 19 (Bassegoda 1972, 19, 20, 26). In

Barcelona the Escuela de Maestros de Obras did not open until 1850, and there was no

independent school of architecture in Barcelona until 1875 (Basurto 1999, 23).

A revealing example of this situation is that from 1870 to 1875, the clients of Barcelona

architects applied for 160 municipal building permits, whereas over the same time

period maestros de obras filed for 1,117 permits (Bassegoda 1972, 41). In fact, the

19th-century city expansions we see today in Spanish provincial capitals is owed in

large part to these professionals. (Bonet 1985, 43) Also significant is the fact that the

professional fees for a maestro de obras were made equal to those of an architect.

(Bassegoda 1972, 34) (Basurto 1999, 22)

This situation would logically lead to fierce competition between the two professions,

with architects pressuring to do away with the Maestro de Obras program, a goal they

ultimately achieved in 1796. However, the program was reinstated in 1814 due to the

large amount of reconstruction required in the country after the Napoleonic wars. The

program was again suppressed in 1855, only to reopen in 1857. In view of this situation,

as Ángel Martín so aptly wrote, “Some were backed by law and others by reason.”

(Martín 2004, 188) The Maestro de Obras program was definitively eliminated in 1871.

Added to all of these factors were the politics of local town halls and other municipal

corporations, which throughout the country disapproved of the centralism imposed by

the Bourbons in the 18th century. This anti-centralism sentiment did not abate until the

19th century. As late as 1835 architects and maestros de obras in Barcelona petitioned

Queen Isabel II, stating that they had “not been appointed chief master builders for

projects commissioned by town councils, courts and other local corporations.” Indeed,

the local corporations “did not defend the interests of the bricklayer or the old guild-

member master builder over the academic architect or maestro de obras. Above all else,

they defended the sphere and legitimacy of their own autonomy as opposed to the

absolutist invasion of central power.” (Marcos 1973-4, CAU 24, 67).

________________

This is the background in which Rafael Guastavino appeared on the scene. It was in

1861, at the age of 19, when he enrolled at the Escuela Especial de Maestros de Obras

in Barcelona to begin his studies. He was already married, had two children and was

living with his affluent uncle, Ramón Guastavino, who had done well as a tailor and had

become founding member of a chain of textile stores. (Oliva 2009a, 65)

If we confine ourselves to the vicissitudes of his life and profession, we could say,

echoing the words of Jorge Luis Borges, that Rafael Guastavino “lived in a difficult

time, like everyone else.”

Guastavino’s first trade had been tailoring, as recorded on his certificate of marriage in

1859. He then began the three-year Maestro de Obras program, which offered classes in

3

the late afternoon, as students worked during the day. The schedule included an hour

and a half of theory and two and a half hours of drafting and practical application every

day. (Montaner 1983, 25) He later worked until 1862 in the studio of maestros de obras

Granell and Robert, and after that, as an assistant to a foundry engineer. (Vegas 2011,

137)

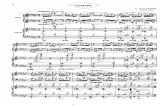

The School was housed in the attic of the Exchange in Barcelona, (fig. 1) a neoclassical

building completed in 1802 arranged around the original 14th-century Gothic-style

Exchange hall. (Fig. 2) This grand hall and the building’s magnificent staircase (Fig. 3)

were bound to have made an impression on the young Guastavino.

Fig. 1 The Exchange in Barcelona. Photograph: Arxiu Mas

Fig. 2 The 14

th century gothic Exchange hall. Fig. 3 The main staircase of the Exchange.

Photograph: Baitiri. Photograph: Baitiri.

4

Below is the 1858 curriculum, which was in force in Guastavino’s day. (Montaner

1983, 25) The program was governed by the General Instruction Act of 1858, also

known as the Moyano Act:

First year:

- Mathematics

- Surveying and Topography

- Technical and Topographic Drawing

- Legal Aspects of Surveying

Second year:

- Descriptive Geometry

- Stereotomy or stone-cutting

- Mechanics

- Materials and Construction

Third year:

- Composition of Public and Private Buildings

- Legal Aspects of Architecture

- Composition Exercises:

Drawing copies of model buildings and designing buildings for residential,

agricultural or industrial use or for entertainment, public utility, festivities and

celebrations.

To complete the study program, the aspiring maestros de obras had to gain experience

by working on public or private building projects during their summer holidays.

Certification was required to validate their participation, and upon completion of

coursework, they were required to submit a final project. (Montaner 1983, 24, 32)

(Martín 2004, 186) By the time Guastavino arrived at the School, the program had

earned a well-deserved reputation.

The Maestro de Obras degree program was concurrent with Architecture. Prior to 1875

Barcelona did not have an independent school of architecture. Before then, students had

to go to Madrid to validate their studies. (Ochsendorf 2010, 19) Architecture was a six-

year program with classes held from nine o'clock in the morning to three in the

afternoon. Attendance was mandatory, absences were sanctioned, and students were not

allowed to leave the school premises during their half hour break. (Prieto 2004, 55)

These strict regulations were a reaction to the lenient attitude toward Architecture

studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in the 18th century. (Quintana 1983, 81-82)

Moreover, the School also wanted to apply the same stringent regulations regarding

attendance and hours as Civil Engineering studies, in turn a copy of the French

engineering school École des Ponts et Chaussées in Paris. A knowledge of French was

one of the absolute prerequisites for the Architecture Studies program, (Basurto 1999,

59) since essentially all of the books at the school were in French (Prieto 2004, 87).

Architecture students also had to have successfully completed their high school

education. (Santamaría 2000, 343)

5

The curriculum for Architecture studies under the 1855 plan is outlined below: (Prieto

2004, 188)

First year

- Differential and Integral Calculus, and Topography

- Pure Descriptive Geometry

- Topographic and Architectural Drawing

Second year

- Rational Mechanics, applying theories speculatively and experimentally to the

elements used in civil and hydraulic constructions

- Elements of descriptive geometry with applications to shades, perspective and

gnomonic projection.

- Mineralogy and chemistry applied to architecture, analysis, manufacturing and

handling of materials

- Architectural Drawing

Third year

- Mechanics applied to the industrial part of the art of building

- Stereotomy of stone, wood and iron, and graphic work associated with the

subject

- Architectural Drawing

Fourth year

- Mechanical theories, procedures and operations of civil and hydraulic

engineering: conduction, distribution and elevation of water; graphic resolution

of construction problems, plotting and working drawings

- Notions of acoustics, optics and hygiene applied to architecture

- Elements of the theory of art and composition theory, as an introduction to the

history of architecture and the analysis of ancient and modern buildings

- Elements of composition of secondary buildings

Fifth year

- History of architecture and analysis of ancient and modern buildings

- Composition

Sixth year

- Legal Aspects of Architecture: exercises specific to the profession; technology.

- Composition

Turning our attention again to the School, Guastavino’s teachers were the architects

José Casademunt, Elias Rogent, Francisco de Paula del Villar and Juan Torras.

(Montaner 1983, 23)

Guastavino always spoke highly of Elías Rogent (1821-1897) and Juan Torras (1827-

1910). Rogent was professor of Topography and Composition and author of the old

neo-Gothic University in the center of Barcelona. Later he would become the first

director of the School of Architecture in Barcelona. Juan Torras was professor of

Construction Materials and of Mechanics and Construction, and was affectionately

6

known as the “Catalonian Eiffel.” (Montaner 1983, 23) Thirty years later, Guastavino

would write about the influence of his teachers in his book Escritos sobre la

construcción cohesiva. (Guastavino 2006, 2)

I owe my understanding of this material not so much to my studies and

research, but to the learning of my distinguished teachers at the Barcelona

School, Mr. Juan Torras and Mr. Elías Rogent, whom I remember with great

fondness and who instructed me and fostered my interest in studying the arts

and applied sciences…

His teacher Elías Rogent also sang Guastavino’s praises in a report on a competition he

had entered in 1874, describing him as a “young man with a brilliant imagination and

extensive practice…” Later in the same report Rogent went on to say:

The project is feasible although not economically flawless. Apart from the very

brief observations I have had the honor to make, I can say to the Company

Management that the author of the project presents a complete constructive

system and that together with the variations he himself would incorporate upon

development of the project, I consider it feasible. (Oliva 2009b, 10)

Guastavino completed the three-year program between 1861 and 1864, obtaining the

following marks: (Bassegoda 1999, 3)

First year (1861-1862):

Topography: Pass (C)

Descriptive Geometry: Outstanding (B)

Second year (1862-1863):

Mechanics: Outstanding (B)

Construction: Pass (C)

Third year (1863-1864):

Composition: Distinction (A)

Legal Aspects: Distinction (A)

Upon finishing his first year, Guastavino was eligible to qualify as topographer by

simply completing a topography exercise. We do not know why he waited until

November 1863 to apply for the title. His qualifying exercise (Fig. 4) is kept at the

library of the Barcelona School of Architecture, together with the draft of the

measurements taken at the site. These are Guastavino’s only documents held at the

school. The exercise consisted of an ink and watercolor survey of an area in Barcelona.

The draft (Fig. 5) is a pencil drawing containing handwritten annotation. Both are in

very good condition, are made on excellent paper and still have the freshness of the day

they were made. The exercise corresponds to an area near the old University, a building

that topography professor and architect Elías Rogent would soon be commissioned to

build.

7

Fig. 4 Guastavino’s 1863 topography exercise. Fig. 5 Draft of the exercise.

(Archivo Gráfico de la Biblioteca de la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona.

Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña)

The teaching at the School was essentially practical. One example is the ideas defended

by Professor Juan Torras, who spoke of the different ways of bonding bricks in a wall:

“The bond should be easy so that the bricklayer can remember it without effort, and if

possible, the bond should be similar to what the bricklayer is familiar with…”

(Montaner 1983, 52) Moreover, the final projects were all easily practicable. Sometimes

the plans included scaffolding and auxiliary equipment (Montaner 1983). All of this

leads us to recognize the realistic, on-the-ground teaching approach at the school.

Another facet of this institution that has made it to our times is a book of third-year

Composition notes dating from 1869 written by Professor Del Villar: Escuela Especial

de Maestros de Obras. Apuntes de Composición de Edificios de habitación, rurales e

industriales. (Del Villar 1869) It is a booklet containing text only, in which Del Villar

explains that the illustrations were not taken to press because they would be circulated

in the classroom. The table of contents gives us a clear idea of the class outline, briefly

covering aesthetic and historic aspects, while describing rural, residential and industrial

buildings in great detail.

Another compilation of notes is one that Montaner mentions in the reference section of

his book L’Ofici de l’Arquitectura. The notes written in Guastavino’s hand: Apuntes

manuscritos de las clases de construcción dadas por el Profesor Torras en el curso

1862-63. (Montaner 1983, 97) These notes are not kept at the library of the School of

Architecture or in the archive of the Institute of Architects.

During his last year at the School, Guastavino also enrolled at the School of Painting,

Sculpture and Printmaking, passing Art Theory and obtaining the highest mark in Art

History. (Bassegoda 1999, 3) After completing his three-year program in 1864, once

again, for reasons unbeknownst to us, Guastavino did not obtain his title. It is possible

that he did not do the requisite practical work during his holidays, (Vegas 2011, 137) or

he may not have completed his final project. We do know that the cost of tuition that

year was 1,000 reales, (Prieto 2004, 57) which his uncle may not have been inclined to

pay at the time (equivalent to three months’ salary of a qualified construction worker).

In any event, instead of earning his title, Guastavino worked under different colleagues’

names as designer, technical project manager or contractor. (Tarragó 2002, 47) (Oliva

2009b, 5-8)

8

The breadth and caliber of the projects are striking, bearing in mind that Guastavino was

only 22 years of age when he began his career. This may be explained by the fact that

most of Guastavino’s clients were from industrial families, primarily the textile

industry, associated with the business activities of his uncle, Ramón Guastavino. (Oliva

2009b, 4).

Without a degree, at first he could not officially design. Therefore, he worked under the

name of other maestros de obras, which makes it difficult to know what part of the

earlier projects he actually designed. (Oliva 2009b, 4) Adding to the confusion over

authorship, Guastavino was sometimes also the contractor on his projects, (Rosell 2002,

47) a common practice in the profession.

By contrast, in France it was typical at the time for architects to begin working without

having finished their studies. An architecture student at the École des Beaux-Arts could

interrupt his studies at any time and go into business. The creation of the diplôme in

1867 did not make much of a difference since the degree was not required in order to

open a studio. (Prieto 2004, 37)

__________________

Guastavino’s career in Barcelona can be divided into three stages: (Oliva 2009b, 2)

Stage one

The first stage is from the time Guastavino completed his studies in 1864 until he

received his title in 1872; during this time he realized the following projects: (Tarragó

2002, 47) (Oliva 2009b, 5-8)

-1865-71: House of textile merchant Miguel Buxeda on Paseo de Gracia. Demolished.

The project bears the signature of Maestro de Obras Jerónimo Granell, who had

employed Guastavino as a student.

-1866: Four-storey apartment building in the Ensanche neighborhood of Barcelona.

-1868: Blajot apartment building on 32 Paseo de Gracia. Still standing. The project

bears the signature of classmate and maestro de obras Antonio Serra Pujals, although

recognized as the work of Guastavino.

-1868-79: Tanning workshop built for Bernard Muntadas. Demolished.

-1869: Palacio Oliver on Paseo de Gracia. Demolished. The project bears the signature

of Pablo Martorell.

-1866-69: Batlló textile factory in the Ensanche neighborhood of Barcelona. Still

standing, but with several additions. The building currently houses the Escuela de

Ingeniería Técnica and is used for other purposes. There are doubts as to the authorship

of the project, since the fees for “plans and technical project manager” were paid to

Pablo Martorell. It was most likely a joint project in which Alejandro Mary was

engineer, Ramón Mumbrú, contractor, and Guastavino, purportedly the actual site

supervisor. (Oliva 2009b, 7)

-1870-71: Rosich factory, on Calle Pelayo.

-1870: Reparcelling of land adjacent to the Batlló factory, resulting in 19 parcels.

-1870: Independent house for the tailor Manuel Galve in Sarriá. Still standing.

-1871: Vidal e Hijos factory.

9

-1871-74: Juliá apartment building on 80 Paseo de Gracia. Demolished. The plans are

signed by Guastavino first, and formally by Antonio Serra Pujals.

-1871: Apartment building for shoe manufacturer Pablo Montalt on 11 Calle Trafalgar.

Still standing.

-1872: Four-storey apartment building for himself, on Calle Aragón, corner of Calle

Lauria. Demolished.

This makes a total of two individual houses, six apartment buildings, and four industrial

buildings. Most noteworthy among the latter is the Batlló textile factory, which stands

on an expansive 16-acre block. The plot was the result of joining four contiguous blocks

in Barcelona’s Cerdá neighborhood. The engineer Alejandro Mary was the designer,

and Ramón Mumbrú the contractor. (Oliva 2009b, 7) Guastavino is said to have been in

charge of this project. But Guastavino denies this in a letter sent to the newspaper

Diario de Barcelona in 1869, when work on the factory was coming to an end. (Rosell

2009, 1-2) (Ochsendorf 2010, 29)

Dear Sirs: Thanking you in advance, I ask that you kindly publish the

following statement:

For some time now I have been reported in the local papers as the site

supervisor for the Batlló brothers’ factory; this is not accurate. Recently I

have again read the same reference and feel obligated to repeat myself.

In all buildings of this type, there are two thoughts to develop, represented

by two different experts whose powers and limitations are well defined. One

represents the foremost in importance, the eminently useful, that which,

strictly speaking, constitutes the design and management of the factory; this

is the job of the engineer, whose work is determined by the very nature of

the building. The other is of secondary importance in buildings of this type,

namely, the exterior aspect, the pure and simple architectural projection.

The first corresponds exclusively to my distinguished friend D. Alejandro

Mary.

The second belongs to someone who does not like to see his name

published, if we are to avoid hurt feelings.

Your obedient servant, Rafael Guastavino

Barcelona, 18 November 1869.

Stage two

The second stage is from the time Guastavino received his title Maestro de Obras in

1872 until 1877.

Two critical events affected Guastavino in a short period of time. His uncle passed away

on June 27, 1871 (Oliva 2009b, 1), and the official Maestro de Obras program was

10

abolished by Royal Order (published on June 7, 1871), rendering all matriculated

students, even those who had not completed the program, eligible for the title.

The students had one year from the date of enactment of the Royal Order to in sit an

exam or defend a project before a committee of professors (Bassegoda 1972, 20)

(Basurto 1999, 62). Guastavino received the title Maestro de Obras in 1872. There is no

evidence of a final project, probably because he earned his title by examination.

In 1871 Guastavino enrolled in the architecture program at the Provincial Polytechnic

School, where he studied for just one year, since the school closed a year later.

(Bassegoda 1999, 3) However, none of his academic records remain today, neither from

the School of Architecture in Barcelona, nor from his three years at the School, nor

from his year at the Provincial Polytechnic School.

During this second stage Guastavino did not undertake any building projects, dedicating

his time instead to managing the agricultural business handed down to him by his uncle

(Oliva 2009b, 2) (Vegas 2011, 137). His uncle’s death probably explains the drop in

clientele. Although he did not work as maestro de obras during this time, he did

advertise his services and sought commissions, but with no clear results. (Oliva 2009b,

8) (Loren 2009, 73)

Stage three

From 1877 to 1881 (when he left for America).

It is in this stage that Guastavino began building again, taking on a large number of

projects. (Oliva 2009b, 2) (Vegas 2011, 137). Below is a list of the buildings: (Oliva

2009b, 17-18) (Tarragó 2002, 47)

-1875: Muntadas, Aparicio and Co. tanning workshop.

-1877: Grau warehouse in Barcelona.

-1877: Elías apartment building on Calle Nápoles.

-1877: Apartment building for Amparo Vallés Puig on 329 Calle Aragón.

-1877: Workshop for Edmond C. Sivatte on 262 Calle Urgell.

-1877-78: Factory for Ignacio Carreras on 53-55 Calle Casanova.

-1877: Apartment building for Ramón Mumbrú on 14 Calle Doctor Dou. Still standing.

-1877-78: Apartment building and workshops for Modesto Casademunt on 3 Calle

Aribau. Still standing.

-1879: Glass factory for Modesto Casademunt on Calle Enrique Granados, corner of

Calle Aragón.

-1878: Anglada Goyeneche apartment building on 280 Calle Aragón.

-1879: Apartment building for Andrés Anglada on 280 Calle Aragón.

-1880: Industrial building for Eusebio Castells on 54-56 Calle Caspe.

-1877-80: Porcelain factory owned by the Florensa family, Hostafranchs.

- Michans y Cía. factory, in Villafranca(?)

- Martín Riu factory, in San Martin de Provençals.

-1880: Ramón Mumbrú apartment building on 103 Calle Mayor, Sarriá. Still standing.

11

-1880-1881: Theater in Vilassar. Still standing.

-1881-1882: Industrial building for the Estrany family, in Vilassar. Still standing.

Example of the use of the 1878 patent.

-1883-1884: Saladrigas factory in San Martín de Provençals. Still standing. Example of

the use of the 1878 patent.

Thus, we have a total of seven apartment buildings, 11 industrial buildings and one

theater. Here we can see the lack of commissions for independent houses and the

significant number of industrial buildings.

In this last stage in Barcelona, Guastavino patented a system for vaulting in 1878, to

which he gave the obscure name of: Construcción de techos abovedados de inter-

estribos y descarga (a literal translation might be Inter-buttress and unload vault

construction). Guastavino applied for the patent in Madrid, where it was officially given

the curious and rather quaint name of Privilege of Invention. To obtain the patent he

granted power of attorney (Fig. 6) to an engineer from Madrid named Sandalio de

Garbiso. The patent was valid for five years. There is no extant record of the patent,

which means that we have neither drawings nor written descriptions—once again a case

of missing documents. The only mention of the patent can be found in the registration

book of the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office, which includes the title of the

privilege of invention, together with the entry date, payment and validity date. (Fig. 7)

Fig. 6. Power of attorney granted to the engineer Fig. 8. Agreement between Guastavino and

Sandalio de Garbiso. the bricklayers.

(Archivo Histórico de Protocolos de Barcelona) (Archivo Histórico de Protocolos de Barcelona)

12

Fig. 7 Patent entry in the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office registration book.

(Ministerio de Industria y Energía. Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas. Archivo Histórico)

In order to ensure immediate returns from his patent in Barcelona, Guastavino came up

with an unusual agreement reached with four local bricklayers. Under the agreement,

recorded in a notarial act which still exists today, (Fig. 8) the city would be divided into

four zones, each allocated to one of the four bricklayers. They, in turn, were to pay

Guastavino half the cost of a fee, based on facade length and number of floors, every

time the patent was used (we assume it was a floor system for multi-storey buildings).

The document also turned the four bricklayers into fee collectors in their respective

areas, making sure that anyone using the patent paid the stipulated fee, and then

delivering half the amount to Guastavino. (It is curious how often the term “privileged

system” appears in the patent description, as if an advertising slogan.) Before signing

the document, each bricklayer had already given Guastavino 500 pesetas “for the agreed

concession” (at the time 500 pesetas was the equivalent of six months’ salary of a

qualified construction worker in Barcelona). The agreement was signed and notarized

on January 29, 1879, and is held in the Barcelona Archive of Protocols. It is clearly

specified that the patent was valid for “five years ending on the twenty-first of

November, eighteen eighty-three,” two years after Guastavino’s unexpected departure

for the United States.

The patent name Construcción de techos abovedados de inter-estribos y descarga does

not resemble any of the 24 Guastavino patents granted to both father and son in the

United States (Redondo 2000, 895-9). We have also ascertained that there are no other

patents under the name Rafael Guastavino in the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office

archives.

13

In conclusion, Rafael Guastavino was a person with excellent technical training and

exceptional talent, which together with good family contacts enabled him to launch a

brilliant career.

REFERENCES

Acuerdo entre Rafael Guastavino y varios albañiles. Sig. 1258, Notario Francisco

Gomís Miret. Manual 1879-I, núm. 43, f. 129r-131r, 29-I-1879. Archivo Histórico

de Protocolos de Barcelona.

Alonso Ruiz, Begoña, El Arte de la Cantería, Ed. Universidad de Cantabria,

Santander 1991.

Arranz, Manuel, Mestres d’obres i fusters. La construcció a Barcelona en el segle

XVIII, Ed. Colegio de Aparejadores y Arquitectos técnicos de Barcelona,

Barcelona 1991.

Basalobre, Juana Mª, Catálogo de proyectos de Académicos, Arquitectos y Maestros

de Obras alicantinos. Censuras de obras y otras consultas en la Academia de San

Fernando (1760-1850), Ed. Instituto Alicantino de Cultura Juan Gil-Albert,

Alicante 2002.

Bassegoda Nonell, Juan, Los maestros de obras de Barcelona, Ed. Real Academia de

Bellas Artes de San Jorge, Editores Técnicos Asociados, S.A., Barcelona 1972.

Bassegoda Nonell, Juan. La obra arquitectónica de Rafael Guastavino en Cataluña

(1866-1881), in Las bóvedas de Guastavino en América, Ed. Instituto Juan de

Herrera, Madrid 1999.

Basurto Ferro, Nieves, Los maestros de obras en la construcción de la ciudad. Bilbao

1876-1910. Ed. Diputación Foral de Vizcaya. Bilbao 1999.

Bonet Correa, Antonio, La polémica Ingenieros-Arquitectos en España, siglo XIX,

Ed. Colegio de Caminos, Canales y Puertos, Madrid 1985.

Camps Goset, Sergio, Los pioneros del hormigón estructural: de Europa a Cataluña

(Tesina de Especialidad, Ingeniería de la Construcción), Ed. Escuela Técnica

Superior de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos de Barcelona, Barcelona

2009.

14

De las Casas Gómez, Antonio, Las bóvedas de los Guastavino, Revista de Obras

Públicas, Junio 2002/Nº 3.422, pp. 51 a 60.

Del Villar, Francisco de Paula, Escuela Especial de Maestros de Obras. Apuntes de

Composición de Edificios de habitación, rurales e industriales, según las lecciones

explicadas por el profesor de dicha escuela, Barcelona 1869.

Fornés y Gurrea, Manuel, Observaciones sobre la práctica del arte de edificar, Ed.

D. Mariano de Cabrerizo, Valencia 1857.

Graus, Ramón, y Rosell, Jaime, La fábrica Batlló, una obra influent en

l’arquitectura catalana, VIII Jornadas de Arqueología Industrial de Cataluña,

Asociación del Museo de la Ciencia y de la Técnica y de Arqueología Industrial de

Cataluña (mNACTEC), Barcelona 2009.

Guastavino, Rafael, Escritos sobre la construcción cohesiva, Ed. Instituto Juan de

Herrera, Madrid 2006.

Guastavino IV, Rafael, An Architect ans his son, Ed. Heritage Books, Maryland,

USA, 2006.

Laborda Nieva, José, Maestros de Obras y Arquitectos del período ilustrado en

Zaragoza. Crónica de una ilusión, Ed. Diputación General de Aragón, Zaragoza

1989.

Loren, Mar, Texturas y pliegues de una Nación. New York city: Guastavino Co. y la

reinvención del espacio público de la metrópolis estadounidense, Ed. General de

Ediciones de Arquitectura, Valencia 2009.

Marcos Alonso, Jesús A., Arquitectos, maestros de obras, aparejadores. Notas para

una historia de las modernas profesiones de la construcción, Revista CAU, nº 22-23-

24 y 25, Barcelona 1973-1974.

Martín Ramos, Angel, Labor de arquitectos y maestros de obras en los inicios del

ensanche donostiarra, Revista Ondare nº 21, 2002, (pp.345-360)

Martín Ramos, Angel, Los orígenes del ensanche Cortázar de San Sebastián, Ed.

Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona 2004.

Montaner, Joseph María, L’ofici de l’arquitectura. El saber arquitectònic dels

mestres d’obres analitzat a través dels seus proyectes de revàlida (1859-1871), Ed.

Universidad Politécnica de Barcelona, Barclona 1983.

Montaner, Joseph Maria, Gremios, arquitectos y maestros de obras, en Escola

d’Arquitectura de Barcelona. Documentos y Archivo, Ed. Escuela Técnica

Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona, Barcelona 1996.

Ochsendorf, John, Guastavino Vaulting. The Art of Structural Tile, Ed. Princeton

Architectural Press, New York 2010.

15

Ochsendorf, John, Los Guastavino y la bóveda tabicada en Norteamérica, Revista

Informes de la Costrucción, Vol.56, nº 496, marzo-abril 2005, pp. 57 a 65.

Oliva i Ricós, Benet, La Febre d’Or i Guastavino a Vilasar de Dalt, Revista

d’Historia i Patrimoni Cultural de Vilassar de Mar i el Maresme, Nº 25, Vilassar,

junio 2009.

Oliva i Ricós, Benet, L’etapa catalana de Rafael Guastavino (1859-1881). Els camins

de la innovació: València & Barcelona (& Vilassar) & Nova York & Boston… XI

Congrès d’História de la Ciutat. La ciutat en xarxa. Ed. Archivo Histórico de la

Ciudad de Barcelona, Instituto de Cultura, Ayuntamiento de Barcelona. Barcelona

2009.

Partida de matrimonio de Rafael Guastavino Moreno con María Francisca

Ventura, Archivo de la Catedral de Barcelona, libro de “Llicencies d’esposalles”

1859-1860, vol. 200, fol. 67r.

Poder notarial de Rafael Guastavino a Sandalio de Garbiso. Sig. 1258, Notario

Francisco Gomís Miret. Manual 1878-II, núm. 316, f. 1071r-v, 7-VIII-1878.

Archivo Histórico de Protocolos de Barcelona.

Prieto González, José Manuel, Aprendiendo a ser arquitectos. Creación y desarrollo

de la Escuela de Arquitectura de Madrid (1844-1914), Ed. Consejo Superior de

Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid 2004.

Privilegio de invención: “Sistema de construcción de techos abovedados de inter-

estribos y descarga”. Privilegio 5902 del libro de Registro 5008. Archivo Histórico

de la Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas.

Quintana, Alicia, La arquitectura y los arquitectos en la Real Academia de Bellas

Artes de San Fernando (1744-1774), Ed. Xarait, Madrid 1983.

Redondo Martínez, Esther, Las patentes de Guastavino & Co. En Estados Unidos

(1885-1939), Actas del Tercer Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción,

Sevilla, 26 a 28 de octubre de 2000, Volumen II, pp. 895 a 905.

Rosell, Jaime, Rafael Guastavino Moreno. Inventiveness in 19th century

architecture, in Guastavino Co. (1885-1962) Catalogue of Works in Catalonia and

America, Ed. Colegio de Arquitectos de Cataluña, Barcelona 2002.

Rosell, Jaime y Graus, Ramón, La fábrica Batlló, una obra influent en

l’arquitectura catalana, VIII Jornadas de Arqueología Industrial de Cataluña,

Asociación del Museo de la Ciencia y de la Técnica y de Arqueología Industrial de

Cataluña (mNACTEC), Barcelona 2009

Santamaría Almolda, Rosario, Los Maestros de obras aprobados por la Real

Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (1816-1858). Una profesión en continuo

conflicto con los arquitectos, Revista Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie VII, Hª del

Arte, t.13, págs 329-359, UNED, Madrid 2000.

16

Tarragó, Salvador, Guastavino Co. (1885-1962). Catalogue of Works in Catalonia

and America, Ed. Colegio de Arquitectos de Cataluña, Barcelona 2002.

VV.AA., Escola d’Arquitectura de Barcelona, Documentos y Archivo, Ed. Escuela

Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona, Barcelona 1996.

VV.AA., Exposició conmemorativa del Centenari de l’Escola d’Arquitectura de

Barcelona 1875-76/1975-76, Ed. Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de

Barcelona, Barcelona 1977.

Vegas, Fernando y Mileto, Carmina, Guastavino y el eslabón perdido, Actas del

Simposio Internacional sobre Bóvedas Tabicadas, Ed. Universidad Politécnica de

Valencia, Valencia 2011.