Macken-Horarik, M - Interacting With Multimodal Text (2004)

-

Upload

martinacebal -

Category

Documents

-

view

25 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Macken-Horarik, M - Interacting With Multimodal Text (2004)

-

http://vcj.sagepub.comVisual Communication

DOI: 10.1177/1470357204039596 2004; 3; 5 Visual Communication

Mary Macken-Horarik Interacting with the Multimodal Text: Reflections on Image and Verbiage in Art Express

http://vcj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/3/1/5 The online version of this article can be found at:

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at:Visual Communication Additional services and information for

http://vcj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://vcj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://vcj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/3/1/5 Citations

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

A R T I C L E

Interacting with the multimodal text:reflections on image and verbiage in

ArtExpress

M A R Y M A C K E N - H O R A R I KUniversity of Canberra

A B S T R A C T

The phenomenon of the multimodal or composite text is a challenge fordiscourse analysts, particularly those working with linguistic tools fashionedto account for verbal texts. Drawing on systemic functional semiotics, thisarticle focuses on the interactive meanings of two student artworkspresented in a Sydney exhibition called ArtExpress. It analyses thecomplementary contribution of image (artwork) and verbiage (text panel) tothe meaning-making process. Drawing principally on APPRAISAL analysisas practised within Sydney School linguistics, the article proposes a richeraccount of evaluation in both image and verbiage than is currently availablein analyses of separate modes. The article aims to contribute to thedevelopment of semiotic grammars adequate for an integrated account ofmultimodal texts at different institutional moments in their (re)production.

K E Y W O R D S

discourse analysis integrated analyses multiliteracies multimodality systemic functional grammar visual and verbal texts

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Attending to the multimodal poses particular challenges for discourseanalysts who have worked primarily with verbal texts. In attempting toproduce a comprehensive account of the different meanings carried bydifferent modalities, the limits of linguistic grammars are soon reached;consequently, one is forced to look for new semiotic grammars that aresensitive to the character and contours of specific modalities, and responsiveto their interplay in texts and with readers.

One such semiotic grammar has been developed by Gunther Kressand Theo van Leeuwen in Reading Images (1996). Drawing on systemicfunctional linguistics, they provide a theoretically consistent framework foranalysis of visual texts and transform the linguistic paradigm in which they

Copyright 2004 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi:www.sagepublications.com) /10.1177/1470357204039596

Vol 3(1): 526 [1470-3572(200402)3:1; 526]

v i s u a l c o m m u n i c a t i o n

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

work. This article builds on their research, providing a detailed commentaryon the creation of interactive meaning in verbal and visual texts. It takesseriously the challenge issued by Kress and Van Leeuwen (p. 183) to analysemultimodal (or composite) texts in an integrated way using compatibleterminology for speaking about both. This is an important task for bothsocial and educational reasons. First, we deal in multimodal texts on a dailybasis every time we read a newspaper, watch television, play a video orcomputer game, or even read a book. Our semiotic frameworks of analysisshould enable us to understand more about the contribution of differentmodes to our changing semiotic practices. Second, multimodality isincreasingly a feature of the school curriculum and we need to take accountof this in our work in education. Most young learners are already more adeptthan their parents at using computer-based technologies in leisure andschool contexts. Beyond a practical expertise, however, they need access toanalytical tools which make the potentials and limits of these modalitiesmore apparent and more open to challenge and redesign where necessary.Our literacy programs need to facilitate our students metasemiotic work.

This article addresses three questions in the context of a student artexhibition in Sydney called ArtExpress:

(i) How do viewers engage with artworks in exhibitions?(ii) What kinds of interactions are facilitated by different modalities in each

artwork?(iii) What does our analysis of image and verbiage reveal about the uses and

limitations of our semiotic grammars?

The pursuit of a common framework for analysing multimodal textsproduces two kinds of awareness in the analyst (or in this one at least): (a)awareness of a lack of fit between categories of one mode applied toanother; and (b) awareness of the deconstructive power of this kind ofanalysis, which reveals gaps, silences and, surprisingly, providential riches intransmodal analysis. My analysis focuses on two images and theiraccompanying text panels (referred to here as verbiage) from ArtExpress.The category of text is taken to encompass both image and verbiage. I assumethat the reader of the composite text has access to different butcomplementary meaning potentials in each mode and that it is the task ofthe analyst to account for both.

This article comprises five sections. Section 1 discusses the impact ofthe institutional context of ArtExpress on viewing practices. Section 2presents two texts from this exhibition and the factors influencing theircurrent form. Section 3 presents the resources used to analyse interactionalmeanings, focusing on three major systems: contact, social distance andattitude. Section 4 presents an analysis of image and verbiage in the twoworks. Where possible, I draw on analytical resources as outlined by Kressand Van Leeuwen (1996: 11958) to reflect on both modes. However, I

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )6

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

propose a richer account of attitudinal meaning than they provide, anaccount based on recent work within systemic functional linguistics onappraisal systems in discourse.

1 . T H E I N S T I T U T I O N A L C O N T E X T

In order to reflect on the contribution of verbiage and image to interpretivepractices, we need first to consider the institutional context in which theseoccur. The ArtExpress exhibition is hosted every year from January to Marchby the New South Wales Art Gallery and displays the best students artworksproduced for the Year 12 Higher School Certificate examination in the VisualArts. ArtExpress is the gallerys most popular exhibition and attracts thousandsof visitors who might otherwise never set foot inside a gallery. Since itsinception 10 years ago, this exhibition has proved such a crowd puller thatstudent artworks are now displayed in places around Sydney, including DavidJones department store, the State Library, the College of Fine Arts and the ArtGallery of New South Wales. However, the Art Gallery hosts the largest display.

There is an exuberance as well as a technical and artistic sophistica-tion, indeed adventurousness, in the gallery showing of these artworks,which is unmatched in any other exhibition. There are several factors at workhere. First, there is the sheer variety of art forms displayed, includingdrawings, paintings, photography, computer-based images, sculptures,wearables, installation works and art videos. Second, there is the use ofspace. The works are displayed in four large rooms, with some of the largerworks spilling over into the foyer outside. Once they move into theArtExpress space, visitors movements are constrained only by the need toenter and exit through the same room. Of course, you cannot move into laterrooms except through earlier ones but, other than this, the rooms and thespace and hence the viewing path are as open as possible. Third, viewingpractices in this exhibition are very extrovert. There are none of the hushedand respectful decorums accorded other more formal exhibitions elsewherein the gallery. Visitors often exclaim, laugh, respond quite openly to theworks and, perhaps more important, interact with others occupying theexhibition space even strangers whose only connection is to be standingclose by. It is also a space used freely by art apprentices. It is common to seestudents taking notes from text panels or making drawings of the artworks. Itis a very informal and inviting exhibition space.

Viewers typically move between image and verbiage as they respondto each artwork. Many of those I observed at the exhibition would look at theimage for a while, read the text panel, then return to the image. Like them, Itoo used the writing as a meta-commentary on the image, an opportunity tosee the work from the point of view of the student artist. I would respond inthe first instance, often in a diffuse way, to the image and then reframe this inthe light of the text panel, which directed my gaze to certain qualities in theartwork. When I returned to the image, there was more meaning than before

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 7

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

a third semantic domain which was more than the sum of the parts. It isthis domain that is in focus here and which I attempt to account for in myanalysis of interactive meaning in the artworks. If the verbal text carriesmeanings not available in the visual, and vice versa, this complementarityshould be reflected in our analysis of both.

Certainly, if image and verbiage are central to viewers interpretivepractices in this exhibition, then so is talk, which flows in abundance aroundthe artworks. The multimodality of the presentation seems to license similarbehaviour in visitors. As an art and talk-fest, ArtExpress breaks down theboundaries between high culture and popular art, presenting works of avery high quality in the context of popular appeal, and the public respondsby coming in droves.

2 . T H E T E X T S

I now consider the two texts from ArtExpress and the shaping context of theircurrent form as catalogue artworks. These include a photographic work by

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )8

Figure 1 SarahAdameksGloria.

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

Sarah Adamek called Gloria, and a painting by Derek Allan calledElaboration.

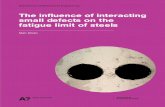

Gloria is a monumental photographic image of an older female nudepresented in two views: an oblique (side-on) view in the left-hand image anda back view (though front-posed) in the right-hand image. This black andwhite photograph has a documentary quality. The artist uses high-contrastlighting to model the shapes, curves, lines and folds of the older body. Thisfigure stands in a contrastive relationship with other nudes more familiar inthe artists contemporary youth culture (an issue explored in her text panel).She conceals her subjects identity while revealing something of the solid andimposing grandeur of the older woman.

Elaboration is a painting of human hands opening to the viewer andsuggesting prayer, joy, or supplication. These hands have a particular salienceas a result of the diagonal vectors they create through a centric holdreleasemovement and the warm light which bathes them from above. This imagecombines a sensory orientation in the treatment of the setting (with itsintense red flowers, green foliage and deep blue background) with anaturalistic coding orientation (verging on the hyper-real) in the artiststreatment of the hands.

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 9

Figure 2 DerekAllans

Elaboration.

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

Before moving on to analyse the interpersonal structures immanentin both image and verbiage, it is important to stress that what is presentedhere is not what the gallery visitors saw, nor is it what the artists submitted.As the notation under the title of each image shows, the number of worksdisplayed was a fraction of those actually submitted for the Higher SchoolCertificate. Of the four artworks submitted by Derek Allan, only three weredisplayed in ArtExpress and, of the fifteen submitted by Sarah Adamek, onlysix were displayed.

But the culling and shaping process is even more trenchant when itcomes to the catalogue. In the exhibition, Gloria consisted of two largephotographic images 1,830 mm high (just over 6) and 550 mm wide (justunder 2) plus four smaller images 530 mm high and 420 mm wide. Thefour smaller photographs were placed to the right of the large ones and thewhole series was displayed on a screen facing visitors as they entered the finalroom of the exhibition. In the catalogue, the two large but separate imageshave been spliced together and treated as one whole. The smallerphotographs showing details of the womans body, such as her nipple or theinside folds of her elbow, have not been included in the catalogue at all. Asimilar transformation process has occurred for the second of the images infocus here. Elaboration is a single painting 510 mm (1.7) high and 405 mm(approximately 1.3) wide. Although three works were displayed in theexhibition, we see only one in the catalogue.

In this selection and shaping of the artworks, we see the imprint ofthe institution on both exhibition and viewing practices. It is important thatwe take account of such processes both in our contextualization of the worksand in our analysis of their structuring principles. This is especiallysignificant when it comes to their compositional details, such as informationvalue, salience and framing. Like other curated exhibitions, ArtExpress shapestexts for public consumption and this affects the art making, art assessingand art displaying business. Neither Gloria nor Elaboration are presented astheir student producers would have intended but rather as the educators,curators and catalogue publishers decided. Of course, without the artworksthemselves, there would have been nothing to massage.

Given this institutional context mediating our response to theartworks, which tools do we use to analyse their interactivity?

3 . T H E T O O L S

In order to develop a semiotic grammar adequate for multimodal discourseanalysis, we have to start somewhere. Hallidays systemic functional grammar(SFG) has proved useful on several counts.

First, SFG attempts to relate linguistic structures to the social contextin which they are produced. Halliday and his colleagues start with theassumption that language is as it is because of the functions it has evolved toserve in peoples lives, ... [and] we have to proceed from the outside inwards,

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )10

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

interpreting language by reference to its place in the social process (Halliday,1978: 4). Relating linguistic structures to social processes is a centralpreoccupation within social semiotics and this makes SFG a useful resourcefor wider study of different semiotic modes. A focus on the relationshipbetween linguistic and social structures has also given it a powerful appliededge over other grammars, leading to some influential research in educationamongst other institutional sites.

Second, as a grammar, SFG enables us to map not just words butarrangements of words, what Halliday (1978: 21, 1994: xxi) calls wordings,and to interpret these linguistic syntagms in functional terms. To date, therehas been very little systematic analysis of analogous structures in visualcommunication. As Kress et al. (1997: 260) point out, analysis of images hasfocused on items of content, or lexis, rather than on the internal structure ofimages, or syntax. This is an important task if we are to develop grammarswhich enable us to relate linguistic to non-linguistic structures.

Third, SFG is a grammar oriented to choice rather than to rules.Linguistic choices are modelled in terms of system networks bundles ofoptions related to different meanings which are realized by particular lexico-grammatical outputs (types of clauses and phrases). Although not suited toall types of meaning structures (prosodic, gradient and culminative), thesystem network is a useful representational resource for displaying discreteoptions for meaning in different semiotic environments (speech, writing,and now, image). They are the chief representational formalism in thecurrent study, as Table 2 shows (see section 4.3).

Fourth, SFG incorporates three general types of meaning in itsanalysis of human communication. These metafunctions include:interpersonal meaning (social and identity relations enacted and played outin texts); ideational (the representation of experiential reality (or, better,realities) in texts; and textual meaning (the ways in which texts are madecoherent and related to their context). The metafunctional principle hasprovided semioticians with abstract and general categories for analysis ofdifferent semiotic systems.

Research that draws on these organizing principles includes analysisof images (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 1996; OToole, 1994); layout (Kress et al.,1997; Kress and Van Leeuwen, 1998), and sound, music and voice (VanLeeuwen, 1999). This research is now making significant inroads into literacyeducation (Callow, 1999; Goodman, 1996; Van Leeuwen and Humphrey,1996). I apply these same principles here in order to understand the power ofthe multimodal text in ArtExpress.

Kress and Van Leeuwen (1996) draw on three principal systems foranalysing interactive meaning in images. These include: the system of contact,through which an image acts on the viewer in some way (demanding aresponse or offering visual information); the system of social distance,through which the viewer is invited close to the represented participants(intimate social distance), kept at arms length (social distance) or put at a

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 11

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

remove (impersonal distance); and two sets of systems within attitude: ahorizontal dimension, which creates viewer involvement (through frontality)or detachment (through obliqueness), and a vertical dimension, whichcreates a relation of power between viewer and represented participants(hierarchical or solidary).

These visual resources correspond loosely to linguistic systems such asspeech acts, mood, and person, and to resources such as evaluation. In thefollowing section, I move between image and verbiage in relation to featuresof contact, social distance and attitude, drawing on resources outlined byKress and Van Leeuwen (1996) where possible and moving beyond thesewhere necessary.

4 . T H E A N A LY S I S

When we analyse interactional meanings within social semiotics, we areconcerned with virtual rather than real relations between texts and readers orviewers. Real readers and viewers are free to engage with a text in any waythey choose, although this engagement is never free of social constraints. Butit is the task of a social semiotics to theorize the texts contribution to thisrelation to account for the structuring principles which open up certainkinds of meanings for readers or viewers and limit others. For simplicity, Irefer to the reader or the viewer, while recognizing that this is a necessaryfiction one that idealizes the complex relationship between texts,interpretive practices and interactants themselves.

4.1 Contact

In analysing images, contact has to do with the imaginary relation establishedbetween represented and interactive participants (viewers). At a primarylevel of distinction, there are two choices here: the represented participantseither demand attention of the viewer, or they offer information. Thedemand picture typically features a human or quasi-human participantwho gazes directly at the viewer. This gaze creates a vector between theeyeline of the represented and interactive participants, demanding a responseof some kind. In the offer picture, on the other hand, the representedparticipants (if human) do not look directly at the viewer but gaze away.Here, the represented participants make indirect contact only, being offeredas objects for the viewers contemplation. Offer pictures are more commonthan demand pictures amongst artworks of this kind, as they include allnon-human participants.

Gloria and Elaboration establish different kinds of connection withthe viewer. With Gloria, there is no direct contact at all. The womanrepresented on the left has her face in shadow with her gaze averted. Thewoman on the right (the same woman presumably) has her back turned andthus disengages altogether from the viewer. Gloria is an extreme example ofthe offer picture a figure for dispassionate study rather than active

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )12

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

engagement. This is not so with Elaboration. Although there is no gaze tospeak of in this picture (we have only a metonym of the human body toengage with), I think that the gesture does make demands of the viewer. Thehands open out directly to the viewers gaze, creating immediate contact. Ifhands could be said to have gaze, then these face the viewer, drawing us in tothe centre of the image. They are very addressive hands. In terms of contactthen, these two images interact with the viewer in quite different ways.

Kress and Van Leeuwen (1996) relate what they call the image act tothe system of speech act and person in language and we can use these toexplore the text panels. Halliday relates speech acts to two basic speech roles(giving and demanding) and two commodities (information, and goodsand services). These yield four basic elementary speech acts: statements(giving information); questions (demanding information); commands(demanding goods and services) and offers (offering goods and services). InEnglish, these semantic choices are typically realized through correspondingmood choices, with statements realized as declaratives, questions asinterrogatives, commands as imperatives and offers through differentmoods, as in the modulated interrogative would you like ...? While choiceswithin the image act are essentially limited to two (demanding/goods andservices or offering/information), speech acts offer speakers a greater range,especially if we consider untypical (non-congruent) realizations of these (seeHalliday, 1994: 68105 for an extended discussion of the mood system).

Mood does not take us very far in understanding the interactivity ofthe text panels, however. Compared with everyday interaction, with its oftenrapid shifts of speech acts and moods, the verbiage is monologic. Everysentence works the same way offering information through declarativemood. We need to look elsewhere if we are to appreciate the contribution ofthe text panels to interpersonal meaning.

The system of person is more promising in this respect. There arethree basic options here: first person (I or we), second person (you) orthird person (he, she, it, they). There are definite connections to be madehere in relation to the image. If the demand quality of Elaboration is a kindof visual you, then the offer quality of Gloria is a visual she. Within visualrepresentation, there are only two options available: the option of second- orthird-person address. There is no equivalent of the first person (I) becauseinteraction is carried out by represented participants and cannot beexpressed directly. This is not so in verbal texts, and is manifested in the useof the first person in a prominent position in both text panels. Dereks panelbegins with the sentence I hope in beauty, and goes on to present a personalview of his art aesthetic. Sarahs panel also emphasizes the personalviewpoint through first person or genitive constructions (I feel or Myartwork).

In this way, the verbiage supplies what the image does not (andcannot). We have access to two kinds of address here: (a) where the imagesopen up (the visual you of the hands or the she of the nude); and (b)

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 13

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

through the verbiage (the I of the text panels). The verbal and visual textsthus create complementary kinds of contact with their addressee.

4.2 Social distance

Simultaneous with the decision to make the represented participants look atthe viewer or not is the decision to depict them as close to or far away fromthe viewer. Social distance is the distance from which people, places and thingsare shown, and creates a visual correlate of physical proximity in everydayinteractions. Social distance is realized through frame size and there are threebasic options available here: close-up, medium or long shot. The close-upsuggests personal closeness between viewer and image; the medium shotsuggests social distance the distance of public business interactions. Andthe long shot correlates with impersonal distance, the distance between peoplewho are and are to remain strangers (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 1996: 131).

Gloria presents us with a figure in medium long shot the full figurewith a small amount of space around it. This distance of at least 3 metres(10) corresponds with the close social distance of a formal relationship. It isthe kind of relationship open to a doctor, an artist, or a medical imagingperson. This distance is mitigated somewhat by the womans nakedness,which suggests a more intimate relationship, especially in the morevulnerable back view. Elaboration establishes a different relation with theviewer. Here we adopt the close personal distance which the close-up makesavailable to the viewer. Although closeness does not always mean intimacy,the proximity of these open hands calls for a corresponding response in theviewer. Where the nude is objectified through analytical social distance fromthe viewer, the hands are subjectified, presented as up close and personal.

What about the written text in relation to social distance? Does therelation with the reader established in the verbiage correspond to that of eachimage? Kress and Van Leeuwen (1996) see formality of style as the linguisticrealization of social distance. They outline three styles based on work by Joos(1967), though similar accounts have also been developed in relation to tenorby Eggins (1994). The personal style is the language of intimates. This styletends to implicitness, context-dependence and local frames of reference; it is thelanguage of social solidarity in a world where much can be taken for granted;it has affinities with what Bernstein (1990) calls restricted code. The socialstyle is the language in which the outside business of the day is conducted.There are fewer colloquialisms and abbreviated forms here and greater use ofstandard syntax and lexis in this style. Greater explicitness is required becauseof the greater social distance between interactants. Finally, the public style isthe language of formal occasions, where people talk like books. This is farmore self-conscious than other styles, more explicit, more articulated in itsuse of full forms. In the public domain, interactants are maximally distantfrom one another and adopt what Bernstein (1990) calls the elaborated code.

It is this code which dominates in the verbiage, which is monologic,

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )14

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

crafted and explicit. Both text panels feature formal vocabulary, genericreference (e.g. the viewer and the older body) and, most telling, high levelsof abstraction, especially in their nominal (noun) groups. In Gloria, forexample, Sarah focuses on abstract essentials such as the beauty andstrength or the true essence and feeling of the body. And in Elaboration, thesame tendency to abstraction is boosted by high levels of nominalization astyle of writing in which dynamic processes are linguistically encoded asqualities (through adjectives) or things (through nouns) rather than as verbs.For example, in nominal groups such as, the interplay between the gestureand its symbolism and its environment or the juxtaposition of the hyper-realsubject and its opulent surroundings, processes like (inter)playing,gesturing and juxtaposing come to function as abstract things. Working inconcert, abstraction and nominalization enable students to objectify the art-making process putting it (and therefore the viewer) at an aestheticremove. Both verbal texts display control of elaborated code and this iscrucial to their success as verbal performances. Making art is only part of thechallenge facing students in the Higher School Certificate exam.Philosophizing about it in the public style is another.

In Elaboration, there are two kinds of social distance established by theartwork: the closeness of the image and the relative semiotic distance of theverbiage. Even though Derek personalizes his message somewhat throughfirst-person pronouns or mental process verbs like hope or contemplate, forthe most part it is couched in the public style. In Gloria, Sarah uses a simpler(less convoluted) variant of the same style with a similar effect on the reader.In this artwork, there is greater convergence of meanings along the socialdistance parameter. But it is also true that, given the distancing quality of theframe size, Sarahs focus on the beauty of her subject invites us to lookagain, to move away from the objectifying viewpoint on the nudeencouraged by choices within the image for contact and social distance. Thereappears to be a compensatory principle at work here in the interplay betweenimage and verbiage, as if the artist wanted to exploit the potential of themultimodal text for multiple meanings. Through her text panel, Sarah re-frames the analytical viewpoint offered by the image, foregrounding theaesthetic appeal rather than the verisimilitude of the older body.

Again, as with the system of contact, we have complementarymeanings established through each mode in relation to social distance. Thereare two kinds of social relations possible here: one made available throughthe public style of the artists commentary and the other through the moreprivate vision of the artist whether distancing, as in Gloria, or close andintimate, as in Elaboration.

4.3 Attitude: involvement and power

Producing an image involves not only the choice between offer and

demand and the selection of a certain size of frame, but also a

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 15

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

selection of angles, a point of view and this implies the possibility of

expressing subjective attitudes towards the participants, human or

otherwise. (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 1996: 135)

There are two dimensions to consider in relation to images: the horizontaldimension, through which participants are presented frontally or obliquely;and the vertical dimension, through which participants are presented fromabove (a high-angle shot), at eye level or from below (a low-angle shot).Horizontal choices represent either involvement (a frontal angle) ordetachment (an oblique angle). Vertical dimension choices represent powerdifferentials between viewer and what is viewed: a relation of viewer powerover represented participant (high-angle shot); a relationship of relativeequality (eye-level shot); and a relation of represented participant (or text)power over the viewer (low-angle shot). We see things from the point ofview of the powerful, the solidary or the powerless.

Gloria presents us with two points of view on the female nude: anoblique angle shot reinforcing a detached perspective in the viewer and aback view, which suggests disengagement certainly by the female nudefrom her audience. Of course, point of view can be a complex phenomenon.The womans nakedness makes her more vulnerable to the viewers appraisaland this reduces detachment. Though this woman is certainly not part ofour world, her nakedness makes her disengagement less alienating. This isreinforced by the eye-level angle along the vertical dimension, an angle whichcreates relative equality between viewer and viewed.

Of course, the eye-level view of the catalogue image does not (andcannot) recreate the impact of the physical position of the work in theexhibition context. Gloria was mounted relatively high on the gallery wall sothat the figure was above eye level physically and seemed to tower over me asI contemplated it. Thus, the power of the image in the exhibition itself wasgreater than can be imagined using the vertical-angle cue in the catalogueimage. In the catalogue image, we view Gloria in a detached but respectfulway, coming not too close, but observing that she is, after all, on a par withthe rest of us. We have neither more nor less power than this woman although we are invited to see her from two viewpoints and hence to engagein different kinds of scrutiny.

Different choices have been made in Elaboration when it comes topoint of view. The hands are presented frontally and at a relatively highangle. This frontality suggests high involvement and the high-angle relativeviewer-power over the implicit demand of the open hands. We are asked, as itwere, to respond and are given the discretionary power to imagine what ourresponse might be. It is as if the image says Its up to you, a point echoed inthe text panel where the writer invites the viewer to consider their ownspirituality. There is far more intersubjectivity created through the resourcesof point of view in Elaboration than in Gloria.

What kinds of attitudes are manifested in the text panels? Once again,

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )16

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

we are concerned with two dimensions: relations of involvement, of greateror lesser solidarity with those around us (the horizontal dimension), andrelations of greater or lesser power over those above or below us (the verticaldimension).

In this semantic domain, we consider the kinds of attitude expressedin verbal texts and made available to the reader. Kress and Van Leeuwen(1996: 147) propose a linguistic analogy between involvement and the use ofpossessive pronouns. There are instances of these in the verbiage. InElaboration, Derek refers to the viewers spirituality using the relativelydistancing third-person pronoun their spirituality and in Gloria, Sarah usesthe genitive construction, my artwork, which suggests involvement with herwork and, by implication, with the reader. A further parallel is suggested byKress and Van Leeuwen between power and the use of evaluative adjectives.Once again, there are examples of these in the verbiage, as in the subjectsnatural beauty in Gloria and a universal beauty in Elaboration. However, afocus on evaluative adjectives per se does not take us very far inunderstanding the kinds of attitude expressed or the cumulative effect ofattitudinally loaded choices in the text as a whole. In relation to verbal texts,we need to ask: What kinds of evaluations does the text foreground? Whatlinguistic resources are drawn on? How does the text dynamicize attitude making particular evaluative positions available to the reader?

Some interesting work on evaluative meaning has emerged within theSydney School of SFG in the domain of appraisal. This research outlinessome of the salient lexical choices in play in evaluation and, most promisingfrom my point of view, focuses on syndromes of attitudinal meaning in text(see Coffin, 1997; Iedema et al., 1994; Macken-Horarik, 1996, 2003; Martin,1997, 2000; White, 1998, 2003 for accounts of this work).

Within appraisal, the systems relevant to analysis of the text panels arecovered under attitude. Within attitude there are three major subsystems:affect (to do with emotional responses and desires); judgement (to do withethical evaluations of behaviour); and appreciation (to do with the aestheticdimensions of experience). These subsystems can be further subclassified, asin Martin (1997), but this would create more complexity than is necessary inthe current context.

Predictably enough, given that this is a public display of the artistspersonal aesthetic, there are several examples of appreciation in both textpanels either focusing on features of the works composition or thevaluation ascribed by the artist to the work (see Table 1). Examples ofappreciation [App] are shown in bold. In Gloria, Sarah states that her artworkcelebrates the beauty and strength of the older body [App: valuation] andthat she has captured the true essence and feeling of the body [App:valuation] in its purest forms [App: composition]. Similar choices forappreciation are made in the Elaboration text panel.

Although appreciation is the primary choice, we also find examples ofaffect and judgement in each text. The verb in Dereks proclamation, I hope in

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 17

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )18

Table 1 Patterns of attitude in the text panels

Theme Focus (new)

Gloria

1. My artwork 1. the beauty and strength of the older

body. [App: +ve valuation of the older

body]

2. Through photography, 2a. the true essence and feeling of the body,

[App: +ve valuation of her representation

of the body]

2b. in its purest forms. [App: +ve view of

her composition]

3. With the use of such techniques as 3. the subjects natural beauty. [App: +ve

light and shadow, valuation of the subjects beauty]

4a. While we 4a. as decrepit and wasting [App/Judg: -ve

view of aged flesh in our culture]

4b. through my respectful visions, 4b. with grandeur and solidity. [App: +ve

[App/Judg: +ve representation of her valuation of ageing flesh]

artistic vision of ageing flesh]

Elaboration

1. I 1. in beauty. [+ve valuation of artists own

aesthetic]

2. For this work, 2. set meaning.

3. rather I, 3. the interplay between the gesture, its

symbolism and its environment.

4. Certain cultural overtones 4. within the work.

5. However, the main thrust 5. its sheer aesthetic diversity; [App: +ve

valuation of the artworks diversity; a

universal beauty [App: +ve valuation of his

aesthetic vision].

6. The viewer 6. the juxtaposition of the hyper-real

subject [App/Judg: +ve valuation of the

veracity of the subject] and its opulent

surroundings, [App: +ve valuation of the

rich background of the painting]

7. their own spirituality. [Judg: +ve

edification of viewers

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

beauty, is explicitly affectual and focuses our attention on his emotionalconnection with his work. Then, in Gloria, we come across the injunctiveconditional clause, While we are culturally conditioned to see the aged flesh asdecrepit and wasting. This clause fuses appreciation with judgement andindexes Sarahs awareness of the prevalence of negative cultural views ofageing and its contrast with her own views.

Attitudes typically carry a positive or a negative loading. While lexicalchoices such as decrepit and wasting carry a negative loading, grandeurand solidity are positive. Many verbal texts create evaluative oppositionssimilar to those in Sarahs text. The system of loading is essential to thecreation of syndromes of attitude in text.

However, equally important in this regard are covert markers ofattitude: lexical choices which work by connotation rather than denotation.The system of attitude type indicates whether values are inscribed (madeexplicit, usually through evaluative adjectives, adverbs or nouns), or areevoked (left implicit, usually through colouring of verb choices or use offigurative language). Both text panels tend to inscribe appraisal throughevaluative nouns, as in, the beauty and strength of the older body oradjectives, as in, the subjects natural beauty or a universal beauty. But thereare also examples of evoked attitude in each text panel. Both writers openwith sentences containing emotive verbs. Derek proclaims that he hopes inbeauty and Sarah that her artwork celebrates the beauty and strength of theolder body. These verbs infuse attitude into the text and flag the guidingpreoccupations of each writer.

When we move away from spatially organized texts such as images (inwhich all elements relevant to interpretation are co-present) to linear textssuch as verbiage, we need to consider how they create certain evaluativepositions for us as we read. We need to dynamicize our account of textualmeaning, much as Van Leeuwen (1996) has done for filmic texts. Throughcombinations of choices for attitude, a text opens up evaluative positions forits reader. These positions accumulate significance as the text unfolds, enteringinto relations of synonymy, contrast or change (see Macken-Horarik, 1996,2003, on the relationship between appraisal choices and reader positioning).

How does a verbal text dynamicize attitude? In order to analyse therhetorical force of evaluation, we need to look at resources within the textualmetafunction, which enables us to create text. There are two complementarysystems that enable us to give different kinds of prominence to informationin the unfolding text. The first system is theme, which highlights the speakersor writers point of departure on the message. In declarative clauses (the onlyones used here), theme typically corresponds to the subject and is realized inEnglish by first position in the clause. Non-subject (marked) themes createspecial kinds of prominence in texts. In Sarahs verbiage, marked themespredominate and centre on the technical aspects of her art-making. Aconsistent pattern of themes contributes to the rhetorical method ofdevelopment in a text.

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 19

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

The other system relevant to dynamic unfolding of attitude in text isfocus. Focus is a phonological system for assigning prominence throughintonation. The units of information in a message which carry the moststress (technically, the tonic) also carry salience for the listener. The part ofthe message which carries salience is called new, and in the unmarked case,new is mapped onto the end of the clause. The part of the message that ispresented by the speaker as already known to the listener is called given andtypically occurs at the beginning of the clause.

The systems of theme and focus create complementary patterns ofprominence in each clause. The theme represents speaker-orientedprominence. It is what I am starting out from. The new, on the other hand,represents listener-oriented prominence: it is what I am asking you to attendto. The clause moves away from the first peak of prominence in themetoward the second in new, and this gives a sort of periodic or wave-likemovement to the discourse (see Halliday, 1994: 3368 for a fuller discussionof this very interesting phenomenon within textual meaning).

If theme presents the writers angle on the message, the new is thereaders point of rest. It is not surprising, then that appraisal tends to beweighted toward the back half of the clause, which is where the focus typicallyoccurs. As Fries (1985) has pointed out in relation to narrative, Many of theevaluative items of the text occur in the unmarked focus of new informationin their respective clauses. The end of the story, likely end of the clause, is aplace of prominence (pp. 31516).

Table 1 presents the evaluative meanings of each text panel as theyoccur within theme and new. The processes of each clause are displayed inthe middle column. Inscribed appraisal is in bold and intensifiers whichamplify the force or focus of each evaluation are underlined. The type ofattitude is shown in abbreviated form in square brackets either appreciation[App] or judgement [Judg]. Loading is identified as positive [+ve] or negative[-ve]. As Table 1 makes clear, most of the inscribed evaluation occurs withinthe new while evoked evaluation is carried by the verbs. Themes have to dowith either the artist or with technical details of the artwork. News have todo with the abstract aesthetic significance of the artwork.

In the Gloria text panel, two attitudinal positions are set up for thereader: a cultural stereotype which sees the aged flesh as decrepit and wastingand the artists alternative vision, which presents it as grand, solid andbeautiful. The writer inscribes her aesthetic attitude through specific andpositively loaded values for appreciation (valuation or composition) as wellas evoking an emotional attitude through continual selection of positivelyloaded verbs which are dispersed throughout the text. This artist doesnt justuse photographic art forms to represent older nudes; she celebrates,captures, enhances and invests the older nude with particular feelings andaesthetic values. In this respect, the attitude evoked by the verbs opens up acomplementary evaluative position on the artwork, encouraging a moreinvolved, even reverential attitude in the reader and moving us away from

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )20

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

both distancing abstractions of the news in the verbiage and thedocumentary style of the image.

Two viewing positions are also set up in the Elaboration text panel.One has to do with the artists aesthetic and the other with spirituality, whichbook-end the verbiage. Both are positively loaded. Affect is dispersed in itsrealization here too. An emotional response to the image is invited, throughthe use of evoking verbs like hope, explore, encouraged and contemplate.The text panel inscribes the aesthetic value of the work through attitudinalnouns and adjectives and evokes feeling and awe through attitudinal verbs.

Again, as with contact and social distance, the two modes set upcomplementary attitudes in the viewer. Table 2 highlights these differencesand presents the trends for contact, social distance and attitude for the twotexts.

There are clear parallels between evoked appraisal and involvementand inscribed appraisal and power in the verbal texts. While expressions offeeling about ones work invite solidarity with the reader, abstractpronouncements of ones aesthetic create hierarchies, as if control ofabstraction is crucial to a place at the art theory table.

Work on attitude within linguistic texts can also have pay-offs for ourthinking about visual text. Of course, we are dealing with different semioticcodes here: in verbal texts with a linear code and in visual texts with a spatialcode. In the linear code, there is a temporal unfolding of meaning and in thespatial code everything that is needed for interpretation is immediately co-present. These different codes influence the subjectivities available to theviewer/reader. Where the image is implicit and embodied, the verbiage(certainly in the interpretive genre as here) is explicit and attenuated. As aconsequence of this, different systems need to be developed to account forattitude in each modality. Nevertheless, the potential for transmodal work isthere.

If we consider the very emotive image from Elaboration, how do weaccount for the affectual meaning of the opening hands, the strongholdrelease pattern in the gesture which demands a response? For me, thegesture is an expression of desire in which the emotional theme of theopening hands is overlaid on the representational meaning of the image. InGloria, affect is cooler and more dispassionate than that of Elaboration butnevertheless a factor to take account of in interactional analysis. Of course,analysing the semiotic systems underlying the emotional content of animage is no simple matter. But the accumulation of attitudinal meanings inthe verbal texts, the dispersed character of their realization, particularlywithin evocative appraisal, is suggestive for work in the visual realm. Itorients us to the image as a whole (text rather than syntax) and to the overlayof affectual meaning over representational meaning.

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 21

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )22

Table 2 Summary of choices for contact, social distance and attitude in the two texts

Image Verbiage

Contact ContactOFFER OFFER

IMAGE (Info) Absence ofACT gaze at viewer DEMAND

SPEECH ACTDEMAND INFORMATION(Goods & Direct gazeServices) GOODS & SERVICES

THIRD

PERSON SECOND

FIRST

Gloria: Absence of gaze at viewer (she). Gloria and Elaboration: Use of first Elaboration: Direct gaze at viewer (you) person (I) to express personal viewpoint.

Occasional use of third person (e.g. her)in relation to artworks.

Social distance Social distancePERSONAL PERSONAL

Close-upDISTANCE SOCIAL STYLE SOCIAL

Medium shotIMPERSONAL PUBLIC

Long shot

Gloria: Medium long shot; the social distance Gloria and Elaboration: publicof artistic or medical scrutiny. language of the professional artist; use of Elaboration: close-up; the personal distance of elaborated code in the meta-commentaryintimate communication. on the artwork.

Attitude AttitudeAFFECT

INVOLVEDFrontal angle VALUE JUDGEMENTINVOLVEMENT

DETACHED APPRECIATIONOblique angle

POSITIVEATTITUDE LOADING

NEGATIVE

EVOKEDTYPE

INSCRIBED

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

C o n c l u s i o n

In summary, what effect do these complementary meaning potentials, thesedifferent ways of relating text to viewer or reader, have on our takes ofstudents work? If the image is primary, and it certainly is in an artexhibition, the verbiage offers a commentary on the image, creating a thirdsemantic domain greater than the sum of the parts. This recalls the wordsof Roland Barthes (1977) in his exposition on the Rhetoric of the Image:

Here, text and image stand in a complementary relationship; the

words, in the same way as the images, are fragments of a more general

syntagm and the unity of the message is realised at a higher level, that

of the story, the anecdote, the diegesis. (p. 41)

Our apprehension of both aspects of the multimodal text needs to besensitive to points of overlap, points of difference, and points of directjuxtapositions in each mode. In the ArtExpress texts, we observe two kinds ofcontact which are embodied in the system of person in each mode: the visualyou or she of the images and the verbal I of the text panels. There are twokinds of vision corresponding to two kinds of social distance in each mode:the private vision of the artist (whether distancing, as in Gloria or intimate,as in Elaboration) and the public vision expressed in the formal statements ofthe text panels. Finally, there are two kinds of attitude in each mode. Alongthe horizontal dimension, there is the involved relation suggested by thehands in Elaboration and the detached relation suggested by the nude inGloria. A complementary relation is proposed by the text panels, suggesting

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 23

Table 2 continued

Image Verbiage

Attitude AttitudeVIEWER POWER RAISE

High angle FORCEPOWER EQUALITY

GRADUATIONLOWER

Eye levelREPRESENTED SHARPENPARTICIPANTS FOCUSPOWER SOFTEN

Low angle

Gloria: horizontal: oblique angle suggesting Note: Realizations of Attitude are dispersed detachment and back shot, suggesting throughout text rather than discrete.disengagement from viewer; vertical: eye-levelshot, creating equality. Gloria and Elaboration: primarily Elaboration: horizontal: frontal angle, Appreciation within Attitude; positive Loading suggesting involvement; vertical: high angle and inscribed Attitude type; Graduation: highlyshot, suggesting viewer power. amplified expressions of Attitude.

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

that the nude is not a subject for medical-style analysis but for aestheticappreciation and that Elaboration is not a goods and services type encounterbut an opportunity for contemplation and spiritual edification. Along thevertical dimension, the equality suggested in Gloria is reframed by the artistspowerful public display of her formal aesthetic. In addition, while the viewerhas the power to accede to or deny the demand of hands through the high-angle viewpoint, the verbiage has an injunctive quality which reframes theimage as a spiritual challenge. Thus the analysis highlights the power of themultimodal text in the creation of a third semantic space and the importanceof fashioning tools of analysis adequate to this.

If the semiotic world in which we live and communicate is amultimodal one, then we need access to an analytical apparatus which isadequate to this. But this is a tall order. This analytical apparatus includingits grammar must itself be a highly differentiated and multipurpose tool.Any grammar we develop for multimodal discourse analysis will need tofacilitate specialized (or, perhaps specializable) investigations of differentsemiotic modes (such as language, or image, or music) in their own terms.And it will need to be inclusive enough to explore the interaction of differentmodes, both with one another and with viewers/readers themselves indifferent contexts. Any grammar we use should enable us to understand theways in which semiotic systems structure and constrain particular meaning-making practices and the ways in which these work together and regulateviewing/reading practices.

Furthermore, the development of a grammar for multimodal textanalysis is a pressing task not least within literacy education the field inwhich I work. Analysis and production of integrated texts has now become aroutine part of school learning whether in visual arts, science, geography oreven English. Whatever the subject, students now have to interpret andproduce texts which integrate visual and verbal modalities, not to mentioneven more complex interweavings of sound, image and verbiage in filmicmedia and other performative modalities. Control not just of the practicalapplication of different technologies but of their structuring principles iscrucial to students literacy practices in school education. Thereforeeducators need access to analytical apparatuses (including grammars) whichenable them to relate one modality to another in explicit and mutuallyinforming ways and to problematize their relationships in the process.Before students can do this, they need access to metasemiotic tools foranalysing these texts tools that enable them to move in a mutuallycomprehensible way between one modality and another.

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S

Figures 1 and 2 were produced by students for examination in the Visual Artscourse in the New South Wales Higher School Certificate. The artworks(including two images and accompanying text panels) were reproduced for

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )24

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

the catalogue accompanying the student exhibition, ArtExpress. Bothstudents have given permission for their artwork to be reproduced.

R E F E R E N C E S

Barthes, R. (1977) Image-Music-Text. London: Fontana.Bernstein, B. (1990) The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse (Class, Codes and

Control, Vol. IV). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.Callow, J. (ed.) (1999) Image Matters: Visual Texts in the Classroom. Sydney:

Primary English Teaching Association (PETA).Coffin, C. (1997) Constructing and Giving Value to the Past: An

Investigation into Secondary School History, in F. Christie and J.R.Martin (eds) Genre and Institutions: Social Processes in the Workplaceand School, pp. 196230. London: Cassell.

Eggins, S. (1994) An Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics. London:Pinter.

Fries, P. (1985) How Does a Story Mean What It Does? A Partial Answer, inJ.D. Benson and W.S. Greaves (eds) Systemic Perspectives on Discourse,Vol. 1: Selected Theoretical Papers from the 9th International SystemicWorkshop, pp. 295321. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Goodman, S. (1996) Visual English, in S. Goodman and D. Graddol (eds)Redesigning English: New Texts, New Identities, pp. 3872. London:Routledge/Open University.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1978) Language as Social Semiotic: The SociologicalInterpretation of Language and Meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1994) An Introduction to Functional Grammar, 2nd edn.London: Edward Arnold.

Iedema, R., Feez, S. and White P. (1994) Media Literacy (Write it RightLiteracy in Industry Research Project Stage 2). Sydney: MetropolitanEast DSP.

Joos, M. (1967) The Five Clocks of Language. New York: Harcourt Brace andWorld.

Kress, G., Leite-Garca, R. and Van Leeuwen, T. (1997) Discourse Semiotics,in T. van Dijk (ed.) Discourse as Structure and Process (DiscourseStudies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, Vol. 1), pp. 25791. London:Sage.

Kress, G. and Van Leeuwen, T. (1996) Reading Images: The Grammar of VisualDesign. London: Routledge.

Kress, G. and Van Leeuwen, T. (1998) Front Pages: (The Critical) Analysis ofNewspaper Layout, in A. Bell and P. Garrett (eds) Approaches to MediaDiscourse, pp. 186219. Oxford: Blackwell.

Macken-Horarik, M. (1996) Construing the Invisible: Specialized LiteracyPractices in Junior Secondary English, unpublished PhD thesis,University of Sydney.

Macken-Horarik, M. (2003) Appraisal and the Special Instructiveness ofNarrative, TEXT 23(2), special issue, edited by M. Macken-Horarikand J. R. Martin: 285312.

M a c k e n - H o r a r i k : I n t e r a c t i n g w i t h t h e m u l t i m o d a l t e x t 25

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

Martin, J.R. (1997) Analysing Genre: Functional Parameters, in F. Christieand J.R. Martin (eds) Genre and Institutions: Social Processes in theWorkplace and School, pp. 339. London: Cassell.

Martin, J.R. (2000) Beyond Exchange: Appraisal Systems in English, in S.Hunston and G. Thompson (eds) Evaluation in Text: Authorial Stanceand the Construction of Discourse, pp. 14275. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press,

OToole, M. (1994) The Language of Displayed Art. Leicester: LeicesterUniversity Press.

Van Leeuwen, T. (1996) Moving English: The Visual Language of Film, in S.Goodman and D. Graddol (eds) Redesigning English: New Texts, NewIdentities, pp. 81105. London: The Open University.

Van Leeuwen, T. (1999) Speech, Music, Sound. London: Macmillan.Van Leeuwen, T. and Humphrey, S. (1996) On Learning to Look through a

Geographers Eyes, in R. Hasan and G. Williams (eds) Literacy inSociety (Applied Linguistics and Language Study). London: Longman.

White, P. (1998) An Introductory Tour through Appraisal Theory, papergiven at a workshop on appraisal systems in discourse, University ofSydney.

White, P. (2003) Beyond Modality and Hedging: A Dialogic View of theLanguage of Intersubjective Stance, TEXT 23(2), special issue, editedby M. Macken-Horarik and J.R. Martin: 25984.

B I O G R A P H I C A L N O T E

MARY MACKEN-HORARIK is a senior lecturer in the School of TeacherEducation at the University of Canberra. Her research interests includeeducational linguistics, literacy and multiliteracies. Recent research focuseson applications of systemic functional linguistics to student writing and tomultimodal discourse in front-page news.

Address: School of Teacher Education, Division of Communication andEducation, University of Canberra, Belconnen, ACT, 2601, Australia. [email:[email protected]]

V i s u a l C o m m u n i c a t i o n 3 ( 1 )26

by Martn Acebal on October 18, 2008 http://vcj.sagepub.comDownloaded from