«Mach’s razor» applied to itself: Sober, Einstein’s «Mach’s principle», and the...

-

Upload

vasil-penchev -

Category

Science

-

view

29 -

download

1

Transcript of «Mach’s razor» applied to itself: Sober, Einstein’s «Mach’s principle», and the...

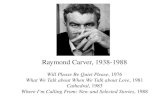

«Mach’s razor» applied to itself Sober, Einstein’s «Mach’s

principle», and the cosmological constant

Vasil Penchev

Bulgarian Academy of Sciences:Institute for the Study of Societies and Knowledge: Dept. of Logical Systems and Models: [email protected]:15 – 12:00, Friday, June 12th, Husova 4, Praha,Department of Analytic Philosophy, Institute of Philosophy, Czech Academy of Sciences

«Parsimony in Philosophy», June 12th – 13th , 2015

Sober’s “Reconstructing the Past”

Sober (“1988: 59) interprets the principle of parsimony relatively: “to a set of empirical background assumptions”

This means that the background assumptions determines a reference set, only according to which can be define a certain subset by its properties or in other words, a notion or theory by its intension

Then the principle of parsimony suggests equating the extension and intension or the “principle of abstraction”: any set can be equivalently defined both by its properties and by its elements

Mach’s «Razor»If that principle should be universal, a common set of that kind should exist

That common set cannot help but the set of all sets

Then the principle of parsimony would be really universal for it would refer to any set

However the set of all sets is self-contradictory as Russell’s paradox (1902) demonstrates

Mach’s «economy of thought» as a «razor»

Mach’s “economy of thought” accepted as an universal principle would be to be referred to that most universal set of all sets

In fact Mach’s “economy of thought” is a paraphrase of “Occam’s razor” and thus one can speak of “Mach’s razor”

However both Occam’s and Mach’s “razor” turn out to be self-contradictory each considered as an absolute principle

The razor of Russell’s «barber»According to the popular version of Russell’s paradox, a

barber has been employed in a village under the following conditions:To be an inhabitant of that villageTo shave those villagers who do not shave themselvesNot to shave those villagers who shave themselves

Then the barber himself should begin to shave as he does not shave himself, but immediately stop for he shave himself, then again and again start and stop

The lesson is: Mach’s “razor” razors itself turning out to be self-contradictory just as that of Russell’s “barber”

Einstein’s «Mach’s principle»

Einstein (1918) involved an additional principle in his general relativity titled by himself “Mach’s principle”

It “razors” any source of gravitational field different than mass and energy

Furthermore Einstein’s application of it forced a hypothetical constant called cosmological to conserve the universe stationary as the simplest conjecture

«Mach’s principle» as the “biggest blunt”

The cosmological constant was called “the biggest blunt” by Einstein (Gamov, “My World line” 1970: 44) after Hubble’s discovery of the expansion of the universe Nevertheless, the “biggest blunt” of some nonzero cosmological constant is very widely utilized nowadays in different cosmological models of the expanding universe and even confirmed experimentally (“Supernova Search Team” 1998; “The Supernova Cosmology Project” 1999)

The history of the “biggest blunt”:

the cosmological constantThe history of Einstein’s “Mach’s principle” can be considered as an example for the self-contradictory of “Mach’s razor” as an absolute principle

Its application forces for the “cosmological constant” and other corollaries to be successively accepted and refused just for their refusing or accepting immediately before that and just as a demonstration of Russell’s Barber and his self-contradictory

Initially: no cosmological constant

There was no cosmological constant in the initial variant of general relativity (1915-1916)

However this infers two “ridiculous” corollaries:

The universe is not stationary

Gravitational field allows as its source some entity, which is neither mass nor energy

Both did not confirm experimentally at that time and should be “shaved” by some relevant correction in the principles

Einstein’s revision of himself

Einstein introduced (1918) a revised variant of his field equation containing an additional member containing the cosmological constant

If the cosmological constant has any nonzero value, both ridiculous corollaries turn out to be “shaved”

The principle justifying that “shaving” Einstein called “Mach’s principle” as a direct application of Mach’s “economy of thought”

The intention of «Mach’s principle»

He grounded it by “Mach’s principle” (only mass and energy is the source of gravitational field) as it implies that the cosmological constant is nonzero

However Mach’s principle itself is an additional assumption in relation to the initial corpus of general relativity principles

Thus one can debate whether Mach’s razor should not shave Einstein’s “Mach’s principle”

GeorgeGamow’s statement of the “biggest blunt”

However Edwin Hubble observed experimentally the expansion of all universe, which therefore turns out not to be stationary

If the universe is not stationary, this rejects “Mach’s principle” in general relativity

Once “Mach’s principle” is rejected, the other conclusion about the cosmological constant should be refused as well

According to Gamow (1970: 44), Einstein declared the cosmological constant as his “biggest blunt” after he had been invited by Hubble to observe the evidences about the expansion of the universe

Now: The “biggest blunt” is ... correct

However the cosmological constant could conserve some nonzero value(s) on other ground, different than that of “Mach’s principle”

Indeed the contemporary experiments are in favor of a nonzero and even variable in time value of the cosmological constant not less than in favor of Einstein’s theory of general relativity

Then, the cosmological constant would still one case in science for a correct conclusion from an incorrect premise

Rejecting « Mach’s principle» ...

Anyway if Mach’s principle is rejected and gravitational field can have some other source, the gravitational field created by that unknown source can be equivalently represented by the same action of some hidden mass and energy

If that is the case, that unknown source of gravitational field would seem as missing energy and mass in the universe

“Dark” entities in physics:

“Dark matter” and “dark energy” are experimentally absolutely confirmed nowadays

As the adjective “dark” shows, the contemporary physical theory and the Standard model first of all cannot even suggest any possible source of them

However any source of gravitational field different than mass and energy would explain both facts above

The global average density of mass and energy as well

Even more, the average density of mass and energy in the universe globally seems to be zero implying the cosmological constant to be zero following Einstein’s introduction of it by Mach’s principle

However if the cosmological constant is globally zero (i.e. being nonzero only locally), it implies some other source of gravitation field in turn

Sober’s cureThe self-contradiction of “Mach’s razor” can be anyway removed and it can survive as a principle if it is interpreted relatively, only to background empirical assumptions as Sober (1988) did Just the change of those “background assumptions” can explain that contradictory history of Einstein’s “Mach’s principle”When Mach’s principle had been introduced, the empirical and experimental data had been ones, then they changed and this should imply its irrelevance to the new data

The cure in mathematics

Indeed mathematics does so, too: Sets of obvious postulates ground axiomatic and deductive method

Any theorem can be true only to some set of axioms rather than at all

If one changes the background assumptions whether for new experimental data or for newly axioms, this implies corresponding changes in the intension or the extension of the theory at issue

The abstract setting of the problem

An information approach to the problem is the following:

One theory as a very extended notion can be defined both by its extension, i.e. as the collection of data (facts), and by its intension, i.e. as a certain subset of a reference set

The two ways of definition are different in general

The quantity of information can serve as a measure for the degree of mismatch between those two definitions of one and the same theory

Theory as a very extended notion

Any theory can be considered as a relation between

(A) principles, axioms, premises and any statements, which are constant, and

(B) experiments, theorems, results and any fact, which are variables

(A) is the intension of the notion, to which the theory is supposedly equivalent

(B) is the corresponding extension

(A) and (B) turn out to be in information equilibrium after a long enough period

Equating the extension and intension

However both any new principle and inconsistent fact (experiment) violate that equilibrium generating unstable disturbance converging to some new equilibrium and thus requiring either new facts or new principles

Consequently, if one adds a new principle (whether even of “Mach’s razor”), this one generates disbalance and addresses implicitly some new equilibrium supposing new facts

That equation as information (entropy)

equilibriumThe coincidence of the extension and intension of a theory implies the minimum of the function of mutual entropy (information), i.e. the information of intension to that of extension

That minimum is furthermore a state of equilibrium, in which the theory would remain arbitrarily long without an external action such as new facts, experiments, principles or at least interpretations

The self-contradictory of «Mach’s razor»

“Mach’s razor” should remove those principles, which are redundant to the available facts

However therefore it is a new principle, which generates information inequilibrium if it makes sense to be involved

That inequilibrium is unstable and converges to some new balance of extension and intension by adding new facts

In turn those new facts contradict to the “razor” converging to its removing and so on just as in the “fable about the barber”

«Mach’s razor» as that information equilibrium

One can object that no theory is the set of all sets

However any theory can be effectively considered as the set of all sets if it is not referred to any more general theory

Just that is the case about any actual theory yet not generalized by some new one

Consequently the self-contradictory of Russell’s barber’s razor is quite relevant to it

In fact, any meta-principle involved in any valid and actual theory generates the same contradictoriness rather only than that of “Mach’s razor”

Conclusions:Any actual and last theory yet not being generalized can be considered effectively as Russell’s set of all sets

Any meta-principle such as “Mach’s razor” is self-contradictorily to be incorporate within its proper principles because this supposes for its boundaries to be known, but they are in fact unknown

This can be demonstrated by the case of Einstein’s “Mach’s principle” in general relativity

References:Banks, Erik (2004) “The Philosophical Roots of Ernst Mach's Economy of Thought,” Synthese, 139 (1): 23–53.Gamow, George (1970) My world line : an informal autobiography. New York : Viking Press, 1970.Einstein, Albert (1918) “Prinzipielles zur allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie,” Annalen der Physik, 55 (4): 241-244.Peebles, Phillip James Edwin and Ratra, Bharat., (2003) “The cosmological constant and dark energy,”. Reviews of Modern Physics, 75 (2), 559–606.Perlmutter, Saul. et al. (The Supernova Cosmology Project) (1999) “Measurements of Omega and Lambda from 42 high redshift supernovae,” Astrophysical Journal, 517 (2): 565–86.Riess, Adam et al. (Supernova Search Team) (1998) “Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant,” Astronomical Journal, 116 (3): 1009–38. Russell, Bertrand (1902) “Letter to Frege,” in Jean van Heijenoort (ed.), From Frege to Gödel, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967, 124–125.Russell, Bertrand (1986) The philosophy of logical atomism and other essays, 1914-19. London - Boston: George Allen & Unwin.Sober, Elliott (1988) Reconstructing the Past. Parsimony, Evolution, and Inference. MIT Press, Cambridge (Mass), London.The CSM Collaboration (2014) “Evidence for the direct decay of the 125 GeV Higgs boson to fermions,” Nature Physics, 10, 557–560.Trimble, Virginia. (1987) “Existence and nature of dark matter in the universe,” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 25, 425–472.

Velice vám děkuji za vaši laskavou pozornost

Těším se na vaše dotazy a

komentáře!