Locomotion: Railroads in the Early Age of Steam

-

Upload

bruce-bradley -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Locomotion: Railroads in the Early Age of Steam

Railroads in the Early Age of SteamOctober 2, 2008 – March 20, 2009

Linda Hall Libraryof Science, Engineering & Technology

5109 Cherry Street, Kansas City, MO 64110 n 816.363.4600 n www.lindahll.org

I

3Locomotion2 Linda Hall Library

Locomotion

In 1824, a Supplement to the latest edition of theEncylopaedia Britannica included a report aboutsome railways near Newcastle where the freight

wagons were drawn by a steam engine that rode ina wagon by itself, with the wheels being driven by theengine. Stationary steam engines had been in use bythis time for well over one hundred years, and railwayswith wooden or even iron rails were commonlyemployed because it was easier for a horse to pull aloaded wagon when its wheels rolled over the smoothsurface of the rails. But a steam-driven locomotiveengine, the Supplement reported, was a novelty,unperfected, and not in general use. As little as tenyears later, all of that would change.

e development of the steam locomotive in the firstpart of the nineteenth century was a dramatic and rad-ical change in transportation technology. It happenedvery quickly over the course of a few decades, as spider-like networks of railroads slowly spread across thelandscape, beginning in the 1820s. e combinationof traditional tramways with a mechanical engine mayhave been a novelty, but the steam locomotives used inthe railway networks were the first practical form ofmechanized land transportation. ey inspiredengineers to continually make improvements in theirdesign, functionality, safety, and efficiency. Newdesigns for stronger, longer bridges were also required,while construction of the lines themselves representedhuge civil engineering projects. Railway networkspermanently changed the land, and the way thatpeople and goods traveled over it. is exhibitionfrom the Linda Hall Library’s collections highlightsthe engineering and technological developments insteam engines, railway design and practice, locomotiveengineering, and some of the major landmarks in theearly history of railroads through the 1860s.

Railway track at theNewcastle mines, om G. Jars.Voyages métallurgiques.Lyon, 1774-81.

Jars visited several Europeancountries in the 1760s to learnabout mining technology.In Newcastle he observed arailway where horses pulledmining wagons that werefitted with flanged wheelsover wooden rails.

Blenkinsop Patent SteamCarriage, Middleton nearLeeds, om T. Gray.Observations on a generaliron rail-way. London, 1823.

John Blenkinsop of theMiddleton Colliery developeda locomotive to transport coalto Leeds in 1812. With itscog-toothed driving wheels,the engine could pull 100 tonson a level track at 3 ½ mph.

Viaduct over the River Colnein 1838, om T. Roscoe. eLondon and BirminghamRailway. London, [1839].

e London and Birming-ham Railway was the first toconnect two major cities, butnot without major engineer-ing projects for viaducts tocross rivers or cuts throughhillsides that permanentlyaltered the lay of the land.

BBrruuccee BBrraaddlleeyy

Librarian for History of Science

Exhibition Curator

I

TT

T

5Locomotion4 Linda Hall Library

Mine Wagons on Rails

Tramways with wooden rails were in use at leastas early as the sixteenth century, and they aredescribed in classic books such as Agricola’s

De re metallica of 1556. e wooden carts loaded withore were kept from going off the narrow track by aniron bar that was attached to the bottom of the cartand went between the rails, so that the cart could notswerve too far to the le or right. e carts made asound, Agricola said, that resembled the bark of dog as they were pushed over the rails.

The Miner’s Friend

The earliest use of stationary steam engines wasalso in mines, to pump out water and allowaccess to the lower seams of ore. omas

Savery invented one at the end of the seventeenth century that was not very practical, but it was the first.e engine was patented in 1698 and demonstratedbefore the Royal Society the following year. But ittook a few years to install the first working device inthe Warwickshire coal mines in 1712.

Mine wagons for use on rails, om G. Agricola. De re metallica. Basle, 1556.

ese wagons were about the size of a large wheelbarrow andhad wooden wheels. Miners pushed loads of ore out of thelongest tunnels with them, over narrowly spaced wooden rails.

Savery’s steam pump, om T. Savery. e miners friend or, anengine to raise water by fire. London, 1702.

e engine did not use a piston, and instead worked by causingsteam to condense in a receiver. is created a vacuum, whichcaused the water to be drawn up through the pipes and into thereceiver. en the receiver was again filled with steam, forcingthe water up and out of the mine, and the process started allover again.

The Newcomen Engine

The idea of using steam to remove water from mines was a good one, and omasNewcomen was able to make it an even more

convincing technology with a steam engine that used a piston moved by steam in a cylinder. It was still relatively inefficient, but it worked. By 1729, whenNewcomen died, his huge but practical machines were at work pumping water out of mines or supplyingwater from rivers for public use not only in Britain,but in Hungary, Belgium, France, Germany, Sweden,Austria and possibly Spain.

James Watt

Improvements in the design of steam engines byJames Watt in the late eighteenth century led tomachines with greater efficiency and more power,

so that it was possible to use steam engines for purposes other than the up and down motion of a pump. A steam engine that made a wheel turn, for example, could power a mill or raise a load of ore from a mine sha. And if a steam engine could turnthe wheel for a mill, it could also turn the wheels of a wagon or carriage.

Newcomen steam engine, om J.T. Desaguliers. Cours dephysique expérimentale. Paris, 1751.

e Newcomen engine illustrated in Desaguliers’ book isthought to have been an actual machine that was installed at a colliery in the English county of Warwickshire. e domedfirebox is on the le, directly beneath the cylinder that encloseda single piston. A huge timber rocking bar connected the actionof the piston to the pump on the right.

Watt’s Double Acting Steam Engine, om D. Lardner. esteam engine explained and illustrated. Philadelphia, 1836.

Watt’s initial design used steam to power the piston in only onedirection, but he continued to make improvements in the design and soon developed the idea for a double acting engine.In this machine, valves alternately open and close to allowsteam into the top and bottom of the cylinder, thus pushing thepiston in both directions.

T

T

7Locomotion6 Linda Hall Library

Trevithick’s Locomotive

The idea of converting a stationary steam engine to one that moved by its own powerover rails was realized about 1802 by Richard

Trevithick. His experimental engine proved, during atrial of the engine in 1804, that it could pull a 10-tonload at about five mph on a tramway of iron-cappedwooden rails that was built for horse drawn wagons.Aer the experiment, the engine was converted backto a stationary engine and used to power an automatichammer at an iron works.

The idea, however, caught on. Working steamlocomotives were put to use in the collieriesand other mining operations in Britain. eir

earliest use was purely industrial and they began to replace horses as a reliable means of pulling a train offreight cars heavily loaded with coal, ore, or quarriedrock from the mine to a port or regional center.

Trevithick's Tramroad Locomotive, om F. Trevithick. Life of Richard Trevithick. London, 1872.

e engine was powered by a single cylinder. To even out the action of the single piston rod, it wascoupled to a large fly-wheel. It is considered the first steam railway locomotive in the world.

Top Right: George Stephenson, aer a portrait by H.P. Briggs,om G.D. Dempsey. e practical railway engineer. London,1855.

George Stephenson is widely regarded as the earliest master ofsteam locomotive construction.

Bottom Right: Entrance to the Liverpool Station; om J.Walker. Report to the directors of the Liverpool and Manchester railway. Philadelphia, 1831.

e Moorish Arch made a handsome entrance to the LiverpoolStation of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Locomo-tives, such as Rocket and Novelty pulled passengers and eightover the 35 miles of the line.

F

I

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Freight traffic was the motivating incentive for a new railway line between Liverpool and Man-chester in the mid-1820s. e Liverpool and

Manchester Railway is oen described as the firstmodern railroad. It operated between two major citieson a regular schedule and provided both freight andpassenger service. It was not, of course, the first railwayline, and George Stephenson, the chief engineer, hadalready designed several locomotives for use on someof England’s mining railways by the time the Liverpooland Manchester Railway opened in 1830. One of hisearlier engines, Locomotion No. 1, for example, wasbuilt in the 1820s to haul coal from the mining regionat 20 mph. It was built specifically for the Stocktonand Darlington Railway, a line that was opened in1825 in lieu of a canal to move coal to Stockton, whereit could be loaded onto sea-going ships.

In contrast to mining railways such as the Stocktonand Darlington, the Liverpool and Manchesterline would link two major cities, and the antici-

pated potential for commercial traffic was muchgreater. When the line was nearly completed in 1829,however, it was still unclear whether locomotive engines were the most suited for use on the new line,or whether it would be better to pull the loaded wagons with ropes using stationary steam engines. To help decide the question, a competition was held.

C

T

9Locomotion

Rocket and the Rainhill Trials

Crowds gathered to watch the famous RainhillTrials, at which George Stephenson’s locomo-tive Rocket triumphed. It consistently pulled

heavy loads at an average speed of 12 mph and a topspeed of 30 mph, without breaking down during thetrials. On the ceremonial opening day of the Liverpooland Manchester Railway in October 1830, Rocketdemonstrated another feature of these heavy mechani-cal locomotives – they were hard to stop. As Rocketapproached, one of the local dignitaries was unable toget out of the way and the engine was unable to stopquickly. It knocked him down and ran over his leg,causing the first accidental railway fatality.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway never-theless opened that year and it was a great success. It was also somewhat a surprise to

find that there was great interest in passenger trafficand not just in hauling freight. Its success influencedrailroad development in England and abroad, as planners began to envision networks of such lines between cities that ran at scheduled times.

Locomotives at the Rainhill Trials, om e Mechanics' Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette, Satur-day, October 10, 1829.

e competition began on October 6, 1829. Sans Pareil (bot-tom) was forced to drop out aer it cracked a cylinder, whileNovelty (middle), lighter, faster, and a real crowd pleaser, wasseverely damaged by a broken boiler pipe. Stephenson’s Rocket(top) finished the trials, winning the £500 prize and everlast-ing fame.

Locomotive competition at Rainhill, October 1829, om S.Smiles. Lives of the engineers. London, 1861-62.

T

S

11Locomotion10 Linda Hall Library

Transfer of Railroad Technology and Engineering

Stephenson quickly became recognized as a master of steam locomotive construction andrailway engineering. So it was natural that

observers traveled to England to learn about Stephen-son’s patents and other aspects of railroad technology.William Strickland came from the United States in1825, for example, on behalf of the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Internal Improvements.His charge was to study the technology of British railway engineering in the hope of providing ideas, andeven patterns for construction, to inspire the inventorsand mechanics of America. Among the detailed plansthat American engineers could study in Strickland’sbook was an engraving of “Stephenson’s patent locomotive,” although it was an early one and alreadyoutdated by newer designs.

G. Stephenson's Patent Locomotive Engine, om W. Strickland. Reports on Canals, Railways, Roads, and other Subjects.Philadelphia, 1826.

Stickland observed this early Stephenson locomotive in 1825, and reported that it could pull 27 wagons loaded with 94 tons at 4 mph on level grade. A distinctive feature was the use of a chain to couple the wheel axles.

“High Bridge,” Portage, New York, om e Civil Engineer & Architect's Journal. (London), No 227 Vol XVI February, 1853.

is timber structure was the highest railroad bridge in the world when it was completed in 1852. Engineers marveled at howquickly and inexpensively it had been built to solve the problem of a railroad link across the wide Genesee valley. It was designed sothat any damaged or deteriorated part could be removed and replaced without disturbing other parts of the bridge.

The transfer of railroad technology began toflow in all directions. In the United Sates, oneof the engineering marvels that Europeans

came to study was the High Bridge at Portage, NewYork. Built in 1851-52, it rose 234 feet above theriverbed, higher than any other railroad bridge in theworld. Its span was impressive too – 800 feet across theGenesee valley. It was designed by Silas Seymour andbuilt completely with timber, except for the piers whichwere of stone. Observers were impressed at how quicklyand inexpensively the bridge was built. e only realproblem with the bridge was the danger from fire. Inspite of every precaution, such as the presence of watch-men and strategically placed barrels of water, the bridgeburned to the ground in 1875 – perhaps giving laterobservers yet another, and unintended, lesson.

S

B

13Locomotion12 Linda Hall Library

Railway Networks and the Britannia Bridge

Bridges were obviously necessary for the expand-ing railway networks of the 1830s, and many ofthem, like the High Bridge, were considered

the most marvelous structures of the time. Anotherone was the Britannia Bridge in north Wales, whichopened in 1850 across the Menai Strait to provide arail link between London and Dublin, through theport of Holyhead. A spectacularbridge by omas Telford had al-ready been built there in 1826, butit was not designed for railway traf-fic so a need for a second bridgearose within a very few years. Vari-ous proposals were considered andrejected, including one in 1838 touse Telford’s bridge for the railway.George Stephenson surveyed therailway route, including the possi-bility of going south to a new portand avoiding the Menai Strait alto-gether. But the Holyhead routepromised the better and more levelline, so when the Chester and Holy-head Railway was finally approvedin 1845, the plans called for a newrailway bridge across the Strait.

Stephenson’s talented son and partner, RobertStephenson, was appointed chief engineer forthe project and thus given the challenge of de-

signing the new bridge. His solution was to build onethat used rectangular tubular structures for strengthand support. Aer the Britannia Bridge opened, ob-servers likened it to an iron tunnel, hung across an armof the ocean on three piers. At a critical point in theconstruction, several prominent engineers came to ad-vise and observe. One of them was Robert Stephen-son’s friend, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

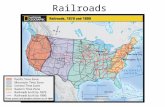

Plan of the Railways of Great Britainand Ireland, 1841 (detail), om F.Whishaw. e railways of Great Britainand Ireland. London, 1842.

e outlines of the British network ofrailways were already in place by 1841,with many lines branching out omLondon alone, such as the London andBirmingham heading northwest and theGreat Western almost due west. (above)

e proposed route for the Chester and Holyhead line led across the Menai Strait to the Isle of Angleseywith connections to Dublin by boat.

The Britannia Bridge, with a train exiting on the island of An-glesey and flanked by two limestone lions that decorated eachend of the tubular iron bridge, from E. Clark. The Britanniaand Conway tubular bridges. London, 1850.

B

BB

15Locomotion14 Linda Hall Library

Brunel and the Great Western Railway

Brunel was engineer for the Great Western Railway, an appointment he had received in1833. Building the railway was part of Brunel’s

larger vision of creating a transportation link fromLondon to New York. By boarding a train at Padding-ton Station on the Great Western, a passenger wouldbe able to travel across Britain, board a steamship, anddisembark on the other side of the Atlantic.

Brunel insisted that the Great Western use broadgauge track of seven feet instead of the four feeteight and one half inch gauge that was becom-

ing the standard gauge on other lines. e ride on hisrailroad would be on the largest, most comfortable,fastest, and safest trains in the world.

But to get to the westernmost part of England,the broad gauge line had to cross the TamarRiver near Plymouth, and it seemed to some

that a ferry would be a better solution than a bridge.Brunel instead adapted the tubular concept for abridge across the span, and the Royal Albert Bridge became a lasting monument to his engineering genius.His tubes were oval shaped and formed the archedtrusses of the bridge. It opened in May 1859, when a passenger train carrying Prince Albert traveled fromPaddington Station in London and crossed the bridge,completing the last link in Brunel’s broad gauge routefrom London to the west.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, engraving by T.G. Barlow aer a painting by J.C. Horsley, omI. Brunel. e life of IsambardKingdom Brunel, civil engi-neer. London, 1870.

Royal Albert Bridge over the RiverTamar, om W. Humber. A com-plete treatise on cast and wroughtiron bridge construction.London, 1861.

e arched trusses for the bridgewere built on shore, then floated to the center of the river and raisedinto position. When the first section was ready to be floated out,some 20,000 spectators are reported to have been on hand towatch the process. e albumenprint used as a ontispiece in thisvolume shows the bridge in construction, one span in positionand the second ready to be raised.

Locomotive for the Great Western Railway, om F. Whishaw.e railways of Great Britain and Ireland. London, 1842.

e Great Western Railway ran om London to Bristol ontracks seven feet wide using locomotives especially designed withdistinctive large center driving wheels.

I

T

17Locomotion16 Linda Hall Library

Locomotives

The locomotives designed for Brunel’s GreatWestern Railway were, in fact, some of thefastest in the world. Locomotives of the Iron

Duke class were the most famous of all the GreatWestern’s broad-gauge locomotives and had a distinc-tive large center driving wheel, eight feet in diameter.ey were designed by Daniel Gooch and are reportedto have had a top speed of 80 mph. ey continued tobe used until the broad gauge tracks were abandonedin favor of the standard gauge of 4 feet 8½ inches in1892.

In America, locomotives came to have a distinctivedesign and appearance that set them apart fromtheir European counterparts. e American

Standard Locomotive was known as a 4-4-0 engine,that is, it had 8 wheels – four in the front that servedto guide the engine on the track, and four behind thatwere powered by the steam cylinders to drive the engine forward. ere were no trailing sets of wheelsbehind the drivers. By the 1840s, this type of enginebecame the locomotive of choice for American railroads, in part because they were powerful and ranwell on the American lines. Manufacturers such as theBaldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia featuredthem almost exclusively in their catalogs. e Ameri-can Standard Locomotives typically were wood-burn-ing engines with balloon smokestacks that weredesigned to let out the smoke and steam but keep inthe cinders and sparks. e cylinders were placed on a level with the axles of the driving wheels, and wereoutside of the track. Other distinguishing features always found on these engines were an enclosed cab, a large headlight, and a bell.

An Iron Duke eight-wheel engine & tender, on the Great Western Railway, om T. Tredgold. e steam engine. London, 1850-53.

When Brunel specified the broad gauge track of seven feet for the railway, he calculated that it would allow not only for larger andmore comfortable railway carriages, but faster locomotives as well which could travel safely on the wide tracks. e Iron Duke class oflocomotives accomplished that goal.

Passenger Locomotive built by the New Jersey Locomotive & Machine Co. “Talisman”, om G. Weissenborn. American engineering. New York, 1861.

e Talisman was a typical American Standard Locomotive, with two sets of driving wheels coupled together and four smallerwheels on a swiveling truck at the ont. American locomotives oen had flourishes of decorative detail around the cab, which is shown only in outline in this black and white lithograph. In 1861, Talisman was a top-of-the-line product, considered by Weissenborn to be the latest and grandest development of the steam engine.

O

A

19Locomotion18 Linda Hall Library

The Chanute Bridge in Kansas City

American standard locomotives such as Talisman would have been seen in KansasCity in the 1860s, but the city did not

become a major railroad center until the first bridgeacross the Missouri River was completed in 1869.en, as now, the river flooded aer high rainfall orduring the spring thaw. But there was little or nothingto keep the flooding waters from shiing the navigablechannel for hundreds of yards or destroying the banksthemselves. So bridging the river was quite a challenge.

Once the bridge was completed, Kansas Citygrew to become an important city in thewestern United States, serving as a depot for

the vast amounts of goods that were carried east andwest, or brought down the river from Nebraska andthe Dakotas. Coincidentally, the bridge was completedonly a few weeks aer the ceremonial golden spike wasdriven at Promontory, Utah, joining the Union Pacificand Central Pacific into a transcontinental railroad.Kansas City was part of a growing network that wastypical of railroad growth around the world. e “ageof steam”, fueled by mechanical and civil engineering,was at full throttle.

Bridge over the River Missouri, At Kansas City, om W.H.Maw. Modern examples of road and railway bridges. Lon-don, 1872.

e Kansas City Bridge was designed by Octave Chanute,started in 1867, and completed in July 1869. A city that wasconsidered “utterly insignificant” by W.H. Maw before thebridge was built, Kansas City became a distinguished rail center with seven railroads shortly aer it was opened. Chanuteis the middle one of the three engineers standing on the deck ofthe completed bridge, with a view looking north om KansasCity, across the river to points beyond.

Details of an American standard 4-4-0 locomotive, such as would have been seen in Kansas City and throughout the United States in the 1860s, om D.K. Clark.

Recent practice in the locomotive engine. Glasgow, 1860.

21Locomotion20 Linda Hall Library

Exhibiton List

Agricola, Georg. De re metallica libri XII. Basel: H. Froben & N. Bischoff, 1556.

Baldwin Locomotive Works, Philadelphia. Illustrated catalogue of locomotives. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott &Co, [187?]

Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton Corporation. Baldwin Locomotive Works: Illustrated Catalogue of Locomotives.Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & co, 1881.

Branca, Giovanni. Le machine. Rome: Ad istanza di Iacomo Martuci . . . per Iacomo Mascardi, 1629.

Brees, Samuel Charles. Railway practice. London: John Williams, 1837.

Brees, Samuel Charles. Railway practice. 2nd ed. London: John Williams, 1838.

Brunel, Isambard. The life of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, civil engineer. London, Longmans, Green, and co.,1870.

The Civil Engineer & Architect’s Journal. Vol 16. London: R. Groombridge and Sons, 1853.

Clark, Daniel Kinnear. Railway machinery, a treatise on the mechanical engineering of railways. Glasgow, Edinburgh, London, New York: Blackie and Son, 1855.

Clark, Daniel Kinnear. Recent practice in the locomotive engine being a supplement to “Railway machinery”.Glasgow: Blackie and Son, 1860.

Clark, Edwin. The Britannia and Conway tubular bridges. London: Published for the author by Day and Son . . .and John Weale, 1850.

Dempsey, George Drysdale. The practical railway engineer. London: J. Weale, 1855.

Desaguliers, John Theophilus. Cours de physique expérimentale. Paris: Chez J. Rollin et C.A. Jombert, 1751.

Dollfus, Charles. Histoire de la locomotion terrestre: Les Chemins de Fer. Paris: L’Illustration, 1935-36.

The Engineer and machinist’s drawing-book. Glasgow: Blackie and Son, 1855.

Gordon, Alexander. An historical and practical treatise upon elemental locomotion. London: Printed for B.Steuart, 1832.

Gray, Thomas. Observations on a general iron rail-way. 4th ed. London: Published by Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy,1823.

Hebert, Luke. A practical treatise on rail-roads and locomotive engines. London: T. Kelly, 1837.

Hero, of Alexandria. Spiritalium liber. Urbino, 1575.

Herron, James. A practical description of Herron’s patent trellis railway structure. Philadelphia: E. G. Dorsey,1841.

Hodge, Paul R. The steam engine, its origin and gradual improvement. New-York: D. Appleton & Co., 1840-41.

Humber, William. A complete treatise on cast and wrought iron bridge construction. [2d ed.] London: E. & F.N.Spon, 1861.

The Illustrated exhibitor, a tribute to the world’s industrial jubilee. London: J. Cassell, 1851.

Jars, Gabriel. Voyages métallurgiques. Lyon: G. Regnault; 1774-81.

Lardner, Dionysius. The steam engine explained and illustrated. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: E.L. Carey & A. Hart,1836.

“Machine pour elever l’eau par le moyen du feu et le poids de l’athmosphere, presentee par MM. Mey et Meyer,in: Machines et inventions approuvées par l’Académie Royale des Sciences. Vol. 4, (1726). Paris: Chez AntoineBoudet, 1735.

Maillard, Sebastian von. Théorie des machines mues par la force de la vapeur de l’eau. Vienna & Strasbourg: Chezles Frères Gay, 1784.

Mantell, Reginald Neville. “An account of the strata and organic remains exposed in the cuttings of the branchrailway, from the Great Western Line near Chippenham through Trowbridge, to Westbury in Wilshire.” In:Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. Vol. 6 (1850), 310-319. London: Longman, Brown, Green,and Longmans, 1850.

Maw, William Henry. Modern examples of road and railway bridges. London: Published at the offices of “Engineering”, 1872.

The Mechanics’ Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette. Vol. 12. London: Published by M. Salmon,1829.

Minard, Charles Joseph. Leçons faites sur les chemins de fer à l’Ecole des ponts et chaussées en 1833-1834. Paris:Carillan-Goeury , 1834.

Morris, John. A series of large geological diagrams. London: James Reynolds, [1858].

Münster, Sebastian. Cosmographiae vniversalis. Basel: ex officina Henricpetrina, 1572.

Roscoe, Thomas. The London and Birmingham railway. London: C. Tilt; 1839.

Savery, Thomas. The miners friend; or, an engine to raise water by fire. London: Printed for S. Crouch, 1702.

Schlumberger, Albert. Description de la première locomotive avec chaudière tubulaire construite par M. Seguin.Lyon: Imprimerie Pitrat ainé, 1889.

Smiles, Samuel. The life of George Stephenson and of his son Robert Stephenson comprising also a history of the in-vention and introduction of the railway locomotive. New York: Harper, 1868.

Smiles, Samuel. Lives of the engineers. London: J. Murray, 1861-62.

Stephenson, Robert and Locke, Joseph. Observations on the comparative merits of locomotive & fixed engines.Liverpool: Printed by Wales and Baines, 1830.

Strickland, William. Reports on Canals, Railways, Roads, and other Subjects. Philadelphia: H.C. Carey & I. Lea,1826.

Supplement to the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. With preliminary dissertationson the history of the sciences. Edinburgh: Printed for Archibald Constable, 1824.

23Locomotion22 Linda Hall Library

Tredgold, Thomas. A practical treatise on rail-roads and carriages. London: Nichols and son, 1835.

Tredgold, Thomas. The steam engine. London: Printed for J. Taylor, 1827.

Tredgold, Thomas. The steam engine. London: J. Weale, 1850-1853.

Trevithick, Francis. Life of Richard Trevithick with an account of his inventions. London, New York: E. & F.N.Spon, 1872.

Walker, Jas, Stephenson, Robert, Locke, Joseph, and Booth, Henry. Report to the directors of the Liverpooland Manchester railway on the comparative merits of locomotive and fixed engines, as a moving power. Philadelphia:Carey & Lea, 1831.

Weissenborn, Gustavus. American engineering. New York, 1861.

Whishaw, Francis. The railways of Great Britain and Ireland. 2nd ed. London: John Weale, 1842.

Williams, Frederick Smeeton. Our iron roads: their history, construction and social influences. London: Ingram,Cooke, and co., 1852.

Wood, Nicholas. A practical treatise on rail-roads, and interior communication in general. London: Knight andLacey, 1825.

Wood, Nicholas. A practical treatise on rail-roads, and interior communication in general. London: Printed forLongman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1832.

Wood, Nicholas. A practical treatise on rail-roads, and interior communication in general. London: Longman,Orme, Brown, Green, & Longmans, 1838.

Right: A visionary proposal tomove passengers, freight,

and mail with steam locomotivesover a national network

of railways, from T. Gray.Observations on a general iron

rail-way. London, 1823.

![Locomotion [2015]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/55d39c9ebb61ebfd268b46a2/locomotion-2015.jpg)