Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

-

Upload

justin-d-geer -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

1/18

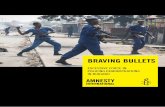

C H A R L E S L. B R I G G S

Linguistic Magic Bullets in the Making of aModernist AnthropologyABSTRACT This article engages current debates about concepts of cul ture inU.S. anthropology by examin ing how assumptionsabout language shape the m . Characterizing l inguistic patterns as particularly inaccessible to conscious intros pec tion, Franz Boas sug-gested that culture is similarly automatic and unconsciousexcept for anthropologists. He used this notion in attempting to posi t ionthe discipl ine as the obligator y passage point fo r academic and public debate abou t difference . U nfortu nate ly, this m ode of insert inglinguistics in the discipline, which has long outl ived Boas, reif ies language ideologies by p rom oting simplistic models th at belie the cul-tural complexity of human communication. By pointing to the way that recent work in l inguistic anthropology has questioned key as-sumptions that shaped Boas's concept ofculture, the article urges other anthropologists tostop asking their l inguistic col leagues formagic bullets and to appreciate the critical role that examining linguistic ideologies and practices can play in discussions of the poli t icsof culture. [Keywords: Franz Boas, culture con cept, l inguistic anthrop ology , language ideologies, scientif ic a utho rity]

The concept of culture, as it is handled by the cultural an-thropologist, isnecessarily something of a statistical fic-tion. .. . It is not the concept of culture which is subtlymisleading but the metaphysical locus to which culture isgenerally assigned.Edward Sapir 1949a:516

Where did so problem atic, so self-defeating a concept [cul-ture], one vulnerable toso many "fairly obvious" objec-tions, one which leads in practice to such dubiousscientific resultswhere did such a concept originate, andin obedience to wha t influences?Christopher Herbert 1991:21IN THE LATE-19TH- and early-20th-century , com petitionto establish and institutionalize scientific disciplines,

candidates needed to carve out a distinct discursive terrainand undermine all opposing territorial claims. Promoterslikewise needed to propose schemas for identifying the prin-cipal landmarks and procedures for institutionalizing thiscartographic process. "Culture," as analytic tool and researchobject, provided anthropology in the United States with animportant source of symbolic capital. As George Stocking(1968, 1992) has argued, Franz Boas advanced the cultureconcept, even though he did not always invoke the term orse it consistently, to establish anthropology as a distinct dis-in the United States and to challenge the scientificof evolutionary perspectives on race. From these

Boasian beginnings, constructions of language have in-formed rhetorics of culture, defining cultural difference inparticular ways and locating anthropology in relationship tomodern and scientific projects in the United States.1From the 1970s to the present, however, it would seemthat many anthropologists have sought to deflate the valueof their disciplinary currency. The epistemological and politi-cal underpinn ings of the culture concept have figured impor-tantly in the decentering impact of poststructuralist, post-modern, postcolonial, feminist, Marxist, and other perspectiveson anthropology. Johannes Fabian (1983) argues that an-thropological constructions of culture and cultural relativityhave helped foster a "denial of coevalness" that has legiti-mated colonialism and imperialism by locating other cul-tures outside the temporal sphere of modernity. The ambiva-lence of James Clifford's often quoted admission that "culture

is a deeply compromised idea I cannot yet do without"(1988:10) expresses a process of critical scrutiny that has, formany anthropologists, repositioned notions of culture as re-search objects rather than as tools of discovery, analysis, andexposition (see also Clifford and Marcus 1986; Marcus andFischer 1986; Yengoyan 1986).Some anthropologists have declared that "culture" isdead or dyingor that it should "be quietly laid to rest"(Kahn 1989:17). Lila Abu-Luxhod suggests that use of th eterm culture necessarily places in operation processes of sepa-rating selves and others that continue to elevate Western

elites and sulxwdinate subaltern subjects; she argues that it isAMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST 104(2):481-498. COPYRIGHT 2002, AMJRICA N ANTHRO POIOGICA I ASSOCIATION

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

2/18

48 2 American Anthrop ologist Vo l. 104, No. 2 June 2002thus necessary to develop "strategies for writing against cul-ture" (1991:138). Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1991) notes thatanthropological critiques of culture have sustained the valueof "the savage slot" in Western society by m aintaining the il-lusion of anthropology's epistemological autonomy from thesymb olic and material processes that created the West. In ad-umbrating the broad range of ways that the concept hasbeen critiqued, Robert Brightman (1995) argues that criticscommit the very sin that they ascribe to "culture"it getsconstructed as homogeneous, bounded, and stable in theprocess. While he seems to subscribe to some dimensions ofthe critique, he gives the impression that the end result hasbeen more a renaming game than an epistemological trans-formation. Herbert Lewis (1998) goes further, suggesting thatculture's critics are guilty of "the misrepresentation of an-thropology" and the distortion of its history. Marshall Sahlins(1999) accuses postmodernists (largely unnamed) of havinginvented the notion that Boas and his students saw culturesas bound, stable, and self-contained. Brightman, Lewis, andSahlins point to work by th e Boasians that presents culture asa dynamic and historical entity, internally differentiated,and often contested by its "bearers."

Threats to the usefulness of culture as U.S. anthropol-ogy's symbolic capital have certainly not emanated fromwithin the discipline alone. Both Claude Levi-Strauss (1966)and Clifford Geertz (1973) were so successful in promotingtheir differing mo dels of culture that their formulations wereappropriated b y literary critics, historians, so ciologists, politi-cal scientists, and others. Anthropologists lost their monopolyon ethnography and cultural analysis as a "cultural turn"wh ich paralleled a "linguistic turn"gained propon ents in arange of disciplines (see Bonnell and H unt 1999). Even as no -tions of "multiculturalism" have essentialized and homoge-nized notions of culture taken from anthropological reason-ing (see Segal and Handler 1995), anthropologists haveseldom played central roles in shaping popular and institu-tional multicultural projects,

Practitioners in cultural and literary studies, postcolonialstudies, ethnic and women's studies, American studies, andother fields have often claimed the authority to define cul-ture in ways that they see as countering the perceived com-plicity of anthropological constructions in consolidating he-gemony, In their introduction to a collection entitled ThePolitics of Culture in the Shadow of Capital, for example, LisaLowe and David Lloyd argue for "a con cept ion of culture asemerging in economic and political processes of modern-ization" rather than Orientalist and anthropological notionsthat characterize "premodern cultures'' as simple and undif-ferentiated, that aestheticize culture, and that extract it fromeconomic and political forces (1997;23). If culture "consti-utes a site in which the reproduction of contemporary capi-

talist social relations may be continually contested" (Lowend Lloyd 1997:26), antitrvpology becom es, for many scholars, aynonym for locations in which hegemonic notions of cul-ure and attempts to reproduce Inequality themselves net re-roduced.

Scholars have often characterized th e w ay in w hich Boasand his studen ts related qu estions of language and culture as"the linguistic analogy" or "the linguistic relativity hypothe-sis." What is at stake here is more than a simple analogy orsome sort of simplistic idea that linguistic categories deter-mine culture (a position that neither Boas nor his studentsadopted); rather, constructions of language and linguisticsshaped Boas's imaginings of culture in a range of crucialways. I argue here that so me of th e m ost problematic aspectsof anthropological conceptions of culture emerge from theparticular ima ginin gs of lan guage an d lingu istics used in ar-ticulating th em . These so-called linguistic analogies emergedat key junctureswhen cultural reasoning got defined andits scientific parameters were delimited. Although Sahlinsand o ther critics are right, mut atis m utan dis, in asserting thatthe Boasians did not see culture as bounded, homogeneous,and stable, this defense is largely beside the point. The prob-lems with the culture concept lie elsewhere, particularly inthe way that it helps produce unequal distributions of con-sciousness, authority, agency, and power. By exploring theseimaginings of language, I hope to open up more room for re-configuring culture.

A second goal is to read this process of co-constructinglanguage and culture in attem pting to grasp the problematiclocation of linguistics in U.S. anthropology. Ironically, themodels of language that get canonized by other anthropolo-gists are probably the least similar to cultural processes andcertainly the least suited to building more sophisticated no-tions of culture. By pointing t o recent work on language thatscrutinizes anthropological contributions to modernity andcolonialism, I ask anthropologists to stop limiting linguisticresearch to a role that destines it for marginalization and torecognize its contributions to the o ngo ing th inkin g of funda-mental anthropological concepts and practices.THE LEGACY OF FRANZ BOASDell Hymes (1983:143-144) and George Stocking (1992:64)have argued that it was not his academic training but the en-counter with Native American nation s that interested Boas inlinguistics. He met Heyman Steinthal, the influential fol-lower of Alexander von Humboldt, during the course of hisstudies in Germany (see Bauman and Briggs in press; Bunz1996 on the influence of Herder and Humboldt on Boas's\ie w of language and culture), But Boas told Rom an Jakob-son (1944:188) that he regretted having railed to attend anyof Steinthal's lectures. Boas did not study Indo-Europeancomparative and historical linguistics, and he did not use itto ana lyze Nat ive Am erican langu ages. Rather, as Michael Sil-verstein (1979) suggests, Boas's rhetorical strategy in his dis-cussions of language is largely negative, constructing lan-guage by way of dem onstrating the failure of Indo-Europeancategories as point s of reference. H e challenges a prime con-ceit of Euro-American elites in arguing that the grammaticalsubtleties of m any "primitive languages" can m ake that epit-om e of linguistic precision and elegance. Latin, "seem crude."

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

3/18

Briggs Linguistic Magic Bullets 483Beyond providing the clearest challenge to evolutionary

schemas, linguistics afforded Boas a means of mapping thecore and the boundaries of a broader "ethnological" inquiry.Boas suggested that linguistics is of "practical" significancefor anthropology in providing a means of circumventing thedistorting influence of lingua francas, translators, and themediation of "intelligent natives" who embed their theoriesof cultureand their perceptions of what the scientist wantsto hearin the way they cross cultural and linguistic borders.Boas also privileged the "theoretical" contribution that lin-guistics can make to ethnology. Language occupied a par-ticularly privileged place in Boas's efforts to demonstrateboth that human mental processes are fundamentally thesame everywhere and that individual languages and culturesshape thought in unique ways; it thus enabled Boas to pre-sent a broad outline of human universals and specificitiesamodel of culture.

By editing the Handbook of American Indian Languages,Boas attempted to shape how language would be perceivedthrough an anthropological lens, what role it would play inthe discipline, and how researchers would study NativeAmerican languages and entextualize their analyses (seeStocking 1974a). His famous "Introduction" (1911) lays outthe theoretical charter. Boas pressed a number of his studentsinto contributing chapters and following the blueprint heimposedwhich called for the inclusion of phonetic, gram-matical, and lexical analyses as well as text collections. Nota-bly, Sapir's (1922) much more extensive grammar ofTakelma was published only in the second volume, whichappeared 11 years later. Sapir's more structural and humanis-tic view of linguistics made him reluctant to accept Boas'smore atomistic approach to grammatical categories.2

A fascinating and productive tension shapes the influ-ence of Boas's view of language on the way he constructs cul-ture. On the one hand, a crucial element of his attack on ra-cism is the notion that language, culture, and race do notform a single package but, rather, each element pursues a dif-ferent historical trajectory. Communities with similar cul-tural patterns may, he argues (1965), speak unrelated lan-guages. On the other hand, Boas uses this characterization oflanguage as a crucial means of constructing and legitimizingnotions of culture and in providing models for how it shouldbe studied. Silverstein (2000b) argues that linguistics (espe-cially phonology) is incorporated into research on culture inthe form of metaphorical "caiques," creating point-for-pointcorrespondences that treat cultural data like linguistic dataand/or transpose linguistic modes of analysis onto culturalnes. Rather than a single analogy, Boas's constructions of

language vis-a-vis culture pursue a number of lines.1. Languages and cultures do not develop along simple, unil-

inear evolutionary sequences. In seeking to undermineevolutionist arguments for the increasing sophistica-tion of all human institutions in a linear progressionfrom primitive to civilized, Boas argues that "it is per-haps easiest to make this clear by the example of

e, which in many respects is one of the most

important evidences of the history of human devel-opment" (1965:160). Venturing forth with a broadgeneralization regarding linguistic change, Boas ar-gues that language seems to reverse the evolutionists'historical cartography, moving, on the whole, frommore complex to simpler forms. In a host of works,including his publications on art (1927, 1940b), Boasextends this argument to cultural forms. As we shallsee, the rejection of evolutionism did not entail theconviction that no universal framework for compari-son could be discerned. As Hill and Mannheim (1992)point out, widespread accounts of Boasian "relativism"fail to appreciate that he saw cultural and linguisticparticulars as systematically related to universals.

2. All humans have language and culture, but all languageandcultures are unique. For Boas, language and cultureconstitute what is uniquely and fundamentally hu-man. He argues that animals also have patternedways of relating to nature and to each other. What isdistinctively human is variabilitybehavior is learnedthrough the internalization of "local tradition" ratherthan determined by environmental conditions or in-stinct (Boas 1965:152). Boas asserts that "language isalso a trait common to all mankind, and one thatmust have its roots in earliest times" (1965:156). Inthe introduction to the Handbook and elsewhere,Boas argues that each language is distinct on phono-logical, lexical, and grammatical grounds. Thus, thescientific study of what is most characteristically hu-man lies not in discovering biological, cultural, orlinguistic universals alone but in the empirical studyof variability. Linguistics provided a privileged modelfor locating and comparing difference, in that itseemed to be the most universalall societies possessthe ability to communicate through languageandthe most variable at the same time, given the range oflinguistic diversity.

3. Membership in linguistic and cultural communities in-volves the sharing of modes of classification. One of themost crucial and widely explored dimensions of thelinguistic analogy pertains to Boas's emphasis on thecentrality of categories in social life. He suggests that"our whole sense experience is classified according tolinguistic principles and our thought is deeply influ-enced by the classification of our experience" (1962:54). The centrality of classification for Boas followsfrom a fundamental divergence between experienceand the means available to encode it linguistically:"Since the total range of personal experience whichlanguage serves to express is infinitely varied and itswhole scope must be expressed by a limited numberof word-stems, an extended classification of experi-ences must necessarily underlie all articulate speech"(1965:189). Cultural categories channel social liteand relations with the natural environment in par-ticular customary or traditional ways. Boas moves inThe Mini of Primithv Man (1965:189) from acoustic

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

4/18

8 4 American Anthropologist Vol. 104, No. 2 - June 2002articulations to the way that lexical and grammaticalunits categorize unique sense impressions and emo-tional states. Arguing that "in various cultures theseclassifications may be founded on fundamentally dis-tinct principles," he uses color perception, food cate-gories, the terminology of consanguinity and affin-ity, and ways of perceiving illness and nature asexamples (1965:190-192),

4. The principle of selectivity in languages and cultures. Acrucial dimension of Boas's attack on ethnocentrisminvolves the principle of selection. He argues that "ifin a language the number of articulations were un-limited the necessary accuracy of movements neededfor rapid speech and the quick recognition of soundcomplexes would probably never develop" (1965:188). Languages must select a limited number of"movements of articulation" from the vast range ofpossibilities, and the possibilities for combiningthem must be restricted as well (Boas 1965:189). Thequestion is not just one of which elements are cho-seneach phonetic element is patterned in waysthat contrast substantially with how similar soundsare embedded in other languages (Boas 1911:1819).Each culture similarly represents a unique selectionfrom the vast range of human possibilities and a par-ticular type of "structure" that links them (Boas1965:149).3

5. The operation of categories is automatized and uncon-scious. Constant repetitions of this limited number ofarticulations "bring it about that these accurate ad-justments become automatic/' resulting in firm asso-ciations between articulations and their correspondingsounds (Boas 1965:189) that are utilized "automat-ically and without reflection at any given moment"(Boas 1911:25). This quality limits speakers' ability torepresent their own language: "The use of language isautomatic, so that before the development of a sci-ence of language the fundamental ideas never riseinto consciousness"" (Boas 1965:192-193). Languageis thus free from the "secondary explanations"dis-tortions of the historical basis of the development ofcategories through rationalizationthat so plaguethe study of culture. Herein lies an important basisfor advancing what Stocking (1968) calls Boas's dis-placement of biological or racial determinism by cul-tural determinism; the very possibility of communi-cation and social order was based on surrender tocategories over which the individual lacks both con-trol and awareness.

In the case of cultural forms, the constant repetition ofions also Increases their emotional hold. Violations of ac-ted behavior and the need to transmit customs to chil-, who often misbehave or question the basis of accepted

condary explanations that spring from thein which cultural forms are lodged In society at that

moment, thereby obscuring their historical basis. Folklorestands alongside language as a privileged example in thiscontext. In Boas's view, it springs from the emergence intoconsciousness of unconscious processes; by attempting to ex-plain custom, these secondary explanations serve to legiti-mate cultural forms and processes. Language provides a privi-leged site in which to study categories and their operation, inthat cultural data tend to get mixed up with secondary expla-nations. As Stocking notes, these notions of unconscious pat-terns and secondary explanations "implied a conception ofman not as a rational so much as a rationalizing being"(1968:232).

6. The constant danger of distortion in cross-cultural research.Particularly in his famous article "On AlternatingSounds" (1889), Boas argues that fieldworkers are notexempt from the distortions that arise when one setof unconscious patterns is projected onto another.He begins with experimental evidence that smacks ofhis earlier career in psychophysics, suggesting that"we learn to pronounce the sounds of our languageby long usage" (1889:48). Other sound patterns arethus misperceived through the process of fittingthem into familiar patterns. After reporting his ownexperiments on perceptions of the length of lines,Boas presents the now familiar argument that colorterms shape the perception of color; an individualwhose language lacks a term for "green" will perceivesome green samples as yellow and others as blue,"the limit of both divisions being doubtful" (Boas1889:50). Boas asserts, however, that cross-culturalresearch produces more authoritative examples thanconventional psychology.

In a classic move, Boas suggests that claims to the effectthat "alternating sounds," perceived fluctuations in how par-ticular sounds in Inuit and Native American languages arepronounced, provide "a sign of the primitiveness of thespeech in which they are said to occur" (1889:52) are evi-dence of bad science, not faulty languages. He argues that"the nationality even of well-trained observers" shapes howthey perceive the sounds of a non-Indo-European language,reducing them to phonological patterns with which they arefamiliar (1889:51). Moreover, "the first studies of a languagemay form the strong bias for later researchers1' (Boas1889:52), imbuing the misperception with scientific author-ity. Boas brilliantly critiques evolutionism, demoting its cen-tral claim regarding the greater simplicity and mutability of"primitive" forms, their presumed status as defective copiesof European institutions, into a predictable form of laic dis-tortion. In doing so, he appropriated the scientific authorityformerly enjoyed by evolutionists for his own emerging an-thropological perspective. Phonetic misperception and themisreading of Native American grammatical categories pro-vided a model for thinking about the way that "the bias ofthe European observer" (Boas 1935:v) amid distort the re-cording and interpretation of cultural material as well.

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

5/18

Briggs Linguistic Magic Bullets 4 85TABLE 1. Boas's consonan t chart .

BilabialLabio-dentalLinguo-labial . . .Linguo-dcntalDentalLingual

ApicalCerebralD o r s a l -

M e d i a l . . . .Velar

LateralGlottalNasal

Stops.Sonant.

bdd

} -gBL&N

Surd.Ptt

tkqL

Fortis.p !t!tl

t!k!q'L!

Spirants.Sonant.

VV

Ci

z

Yr1

Surd.fftcs

XXI

Nasals.Sonant.

mnn

nfifi

Surd.

n

ft

Trill.Sonant.

rrT

Surd.

?

rp.

Semi-vowels y, w. B re ath ,' h. Hiatus7. Charting the vast spectrum of human possibility. Boasmapped the vast phonetic spectrum of human possi-

bility on two axes, the location of articulation (wherethe airstream is obstructed in the mouth and throat)and the manner in which air is impeded. Boas cap-tures the cartography of h um an possibility for conso-nants in a single chart (see Table 1), thereby repre-senting it abstractly, visually, and scientifically. Thisuniversal, objective phonetic grid has helped tran-scend nationalistic and scientific biases evident inevolutionary research by locating languages spokenby observers simply as different sets of points on thesame grid.Boas goes on to extend the mode l of difference he devel-

tic grid for Boas lay in what he describes as the univer-

y of behavior in regard to his relations to nature and to hisSome of Boas's most interesting examples are evi-in his comparisons of stylistic and symbolic dimensions

of plastic arts. In his discussion of expressive art, he suggeststha t "the con tents of primitive narrative, poetry and song areas varied as the cultural interests of t he singers" (1927:325).8. The need for a "purely analytic" m ethod of descriptionand ana lysis. Boas argues that previous students ofNative American languages lacked arigorousresearchmethodology, and the Handbook offers a model forsystematic fieldwork and analysis guided by scientificprinciples. Boas taught his students how texts should bewritten phonetically, and he argues for "a presentationof the essential traits of the grammar as they wouldnaturally develop if an Eskimo, without any knowl-edge of any other language, should present the essen-

tial notions of his own grammar" (in Stocking1992:81). In this "purely analytic" techniq ue, the u n-conscious categories of language thus become notonly the centralresearchobject but the central meth-odological tool as well, thereby avoiding the distort-ing effects of Indo-European categories.The goal in exploring custom s and traditions is similarlyto identify the categories that shape not only how people be-have but how they perceive their actions. With respect to acollection of texts, Boas asserts, "1 $>ive a description of themode of lite, customs, and ideas ot the Tsimshian, so tar asthese are expressed in the myths" (191t>:393). "They present'he remarks, "in a way an autobiography of the tribe*(19I6;393). Hymes points out that these categories serve not

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

6/18

8 6 American Anthro pologist Vo l. 104, No. 2 June 2002nly as tools for discovery and analysis but as "neat qua lita-tive pigeon-holes for ordering ethnological da ta" (1983:28),both on the page and on the museum shelf (Boas 1974). Ifexts are based on Native American categories, their organi-zation should ironically capture not only cultural patternsut people's implicit understan dings of them , just as linguis-tic analyses should reflect native speakers' "essential no-tions" of their grammar. Conducting research in a "purely

analytic" fashion thus enables anthropologists to brackettheir special awareness of the universal framework and thebiasing effects of the categories they learned as children andrender their texts and analyses authoritative.9. Linguistic and cultural research as textual enterprises. AsStocking (1992:91) suggests, Boas viewed linguisticslargely as the study of written texts. He argued thatthe major problem that students of Native Americangroups have had to face in linguisticsas in histori-cal studyis th e lack of a corpus of texts. At the sametime that he built on the efforts of Henry Rowe

Schoolcraft in creating a market for Native Americantexts (see Bauman 1995), Boas fashioned this projectinto a scientific enterprise and tried to place it at thecore of the emerging discipline of anthropology inthe United States. Boas feared the subordination ofanthropologists who did not learn "native'' lan-guages to more established scholars: A classicist w hodid no t know Greek would hardly be taken seriously(1906). On the other hand, learning the languagesand teaching Native Americans to w rite texts in theirown languages provide anthropologists with a m eansof generating a textual corpus to rival that of the clas-sicists and imbuing it with authenticity and author-ityin Derrida's (1974) terms, with a metaphysics ofpresence. Such texts constitute "the foundation of allfuture researches" (Boas, July 24, 1905, in Stocking1974b:l23).

ity for all went hand, Stocking notes, with a comm itment to progress, theion of science and rationality into social life, and a com-ent to act as "a m ember of hu inanity as a whole" ratheras a nationa l sub|ect (1968.149).In the United States, Boas encountered many fin-de-siedeal scientists and social thinkers w ho were concerned with

en seen as disrupting close-knit com mu nities and pressing

workers into impoverished urban quarters. Speaking as apublic intellectual, Boas argues tha t "no a moun t of eugenicselection will overcome those social conditions that haveraised a poverty- and disease-stricken proletariatwhich wilJbe reborn from even the best stock, so long as the social con-ditions persist that remorselessly push human beings intohelpless and hopeless misery" (1962:118). Pointing to thetremendous gap between rich and poor, Boas argues that atruly democratic society would have to undertake "a pro-gram of justice" for poor children that would include hugeexpenditures in c lothing, housing, an d food in order to over-come the physiological effects of poverty in thwarting educa-tion (1945:184, 193). At the same time that he embracedmany goals articulated by socialist m ovements, Boas worriedabout "conflicts between the inertia of conservative traditionand the radicalism which has no respect for the past but at-tempts to reconstruct th e future on the basis of rational con-siderations intended to further its ideals" (1962:136-137),Constructions of language and culture enabled Boas to placeanthropology as a key site for building a third way of chart-ing the future, a regime of knowledge that could help cir-cumvent racism, fascism, and international conflict and, si-multaneously, place the discipline in a pro min ent position.For Boas, culture is the natural enem y of a rational andinternationalist perspective. In his view, to use Arjun Appa-durai's (1988) notion, all people are incarcerated by culture.Linguistic analogies provided Boas with a basis for develop-ing three dim ensions of the distorting effects of culture: First,human beings lack a universal perspective that would enablethem to understand critically the forces that shape their be-havior and consider possible alternatives to their own cul-tural norms. The selectivity principle (listed above as #4) hasdeprived people of awareness of linguistic and cultural ele-ments not incorporated into their own systems, and theprinciple of automaticity and unconsciousness (#5) conflatesunique patterns with what is "universally human," therebypreventing us from grasping our failure to perceive thisbroader spectrum.Second, Boas posits that people lack awareness of eventhat part of the arc of human possibilities that constitutestheir language and culture. Linguistic and cultural patternsare acquired in childhoo d by imitation and then internalizedthrough repetition; afterward, "our behavior in later years isdetermined by what we learn as infants and children" (Boas1962:56). The principle of shared categories (#3) suggeststhat group membership fundamentally involves this sort ofunquestioned, unreasoned sharing of culture. Because our re-lationship to cultural patterns is primarily emotional at-tempts at conscious introspection simply produce secondaryreasoning. Language plays a dual rhetorical role he re. On theone h and, linguistic patterns provide a mean s of demonstrat-ing that native consultan ts do no t need conscious awarenessin order to provide anthropologists with scientific datain-deed, such attempts at conscious analysis only get in theway. On the other hand, because "habitual speech causesconformity of our actions and tho ug ht" (Boas 1962:149), ex-ploring these linguistic labels can enable anthropologists to

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

7/18

Briggs Linguistic Magic Bullets 4 87replay the process in reverse, thereby discovering the natureand historical genesis of cultural categories.

In both his scientific writings and those aimed at moregeneral audiences, Boas points to the political dangers latentin this process of cultural disto rtion. He argues in The Mind ofPrimitive Man (1965) that unconscious categories join dispa-rate entities so powerfully that we fail to perceive their het-erogeneity or the arbitrariness of the connection; this processis "one of the fun dam ental causes of error an d th e diversityof opinion" (1911;70). The secondary reasoning invoked inexplaining and justifying (erroneously) the nature and appli-cation of categories has even m ore p erniciou s effects:

These tendencies are also the basis of the success of fanat-ics and of skillfully directed propaganda. The fanatic whoplays on the emotions of the masses and supports histeachings by fictitious reasons, and the unscrupulousdemagogue who arouses slumbering hatreds and design-edly invents reasons th at give to the gullible mass a plau-sible excuse to yield to the excited passions make use ofthe desire of man to give a rational excuse for actions thatare fundamentally based on unconscious em otion. [Boas1965:210]

The 1938 edition of The Mind of Primitive Man cites Hitler as aprime example.Third, if people canno t grasp the broad range of hu m anpossibilities or their o w n linguistic an d cultural systems, th eyare certainly not capable of grasping the relationship be-tween the two. Just as speakers of a language cannot locatetheir phonetic elements on a cross-linguistic grid or specifyhow they contrast w ith oth er systems, bearers of a culture areunable to see how their categories relate to oth er p ossibilities.Because people take their own cultural patterns for univer-sals, their attempts to look beyond their own cultural bordersbecome value-laden judgm ents of good and bad or colonial-ist projections of one set of categories onto another society.Boas thus, in essence, deem s racism an d xen oph obia to b enatural products of people's misrecognition of the nature ofheir cultural categories and their inability to see how theyrelate to what is "universally human." In Race and Democratic(1945) an d Anthropology an d Modern Life (1962), Boasargues that racism, colonialism, imperialism, and classismrovide evidence of the political stakes for people's inability

a universal process of reifying unconscious categoriess. Balibar (1991) argues that th is sort of reasoning provides

e that it follows directly from Boas's own cu lture theory.Boas's reference to "the gullible mass" suggests that these

provides two exam ples: "A sudden explosion will associate it-self in his mind , perhaps, with tales which he has heard in re-gard to the mythical history of the world, and consequentlywill be accompanied by superstitious fear, The new, un-known epidemic may be explained by the belief in dem onsthat persecute mankind" (1965:200). Note that Boas locatesfolklore and mythology, whose study he so strongly advo-cated and effectively institutionalized, as mod ernity's o ppo-site, a source of conclusions tha t led entire p opulation s to re-act irrationally. On the other han d, speaking for the civilizedworld, Boas suggests that "we have succeeded by reasoningto develop from the crude, automatically developed catego-ries a better system of the whole field of knowledge, a stepwhich the primitives have not made" (1965:198). Althoughprimitives' categories are derived from "the crude experienceof generations," modern knowledge springs from "centuriesof experimentation" (Boas 1965:199-200) and "the abstractthought of philosophers" (Boas 1965:198). The "advance ofcivilization" has enabled "us" "to gain a clearer and clearerinsight into th e hypo thetical basis of our reas onin g" throughincreasing elimination of "the traditional element" (1965:201; see also 1965:196). Paul Radin, it should be noted, waslater to turn this argument on its head in Primitive Man asPhilosopher.* Boas similarly asserts "primitive man, whenconversing with his fellow man, is not in t he habit of discuss-ing abstract ideas" (1911).

It would be wrong to suggest, however, that Boas saw"modern" thought as having been thoroughly transformedby science and rationality. In a classist rhetoric, Boas distin-guishes the "lay public," "average man," and the "popularmind" from the educated. "The less educated" have bene-fited less from the eradication of "traditional elements" (Boas1965:201). Indeed, the "primitive" versus "civilized" opposi-tion is projected into the midst of "modern society": Boaspoints to the "excessive" gap in "cultural status" between"the poor rural population of many parts of Europe andAmerica and even more so of the lowest strata of the prole-tariat" as opposed to "the active minds representative ofmodern culture" (1965:180), It is precisely the failure of "lin-guistic classifications" to "rise into consciousness" that links"primitive" and "uneducated" people (Boas 1965:190): "Theaverage man . .. first acts, and then justifies or explains hisacts by such secondary considerations as are current amongus" (Boas 1965:214). For this reason, Boas suggests that justas "the educated classes" had to develop a nationalist spiritamo ng "the m asses" (1945:118), it is "the educated groups ofall nations" that must teach others how to overcome culturalprovincialism and develop an international perspective(1945:149). Abstract, rationally based thought that tran-scends concrete local contexts is, of course, th e definition ofthe m odern subject; Boas therefore confirms a two-centuries-old relegation of "primitives" and the working class to thepremodern world, thereby helping to sustain the legitimacyof modern schemes for creating and naturalizing social in-equality that he himself criticized, Nevertheless, even ci\i-Und individuals who try to free themselves from "the fettersof tradition* are still "controlled by custom " to a great extent

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

8/18

488 American Anthropologist Vol. 104, No. 2 June 2002within "the field of habitual activities" (Boas 1965:201,224-225).

In a number of passages, however, Boas begins to turnhe relationship among traditionality, rationality, and con-sciousness with class on its head. He argues that in societieswith rigid class segregation, elites are guided by class self-interest and unquestioned traditions transmitted from pastgenerations. The "masses,1 on the other hand, have had littlechance to develop an emotional contact with tradition be-cause of irregular attendance or little interest in school (Boas1962:197). He concludes:

For this reason1 should always be more inclined to accept,in regard to fundamental human problems, the judgmentof the masses rather than the judgment of the intellectu-als, which is much more certain to be warped by uncon-scious control of traditional ideas. [1962:199]Expert knowledge similarly came in for criticism; scientists,like the nobility, artists, and clergy, can be bound by tradi-tional modes of thought and their embodiment in catchphrases that "motivate people to action without thought"(Boas 1945:183). Boas is quick to contain the effects of thisreversal, however, suggesting that science can render intel-lectuals less dogmatic. In any case, he says, these remarkspertain only to "fundamental concepts of right and wrong,"and he suggests that the masses lack the experience andknowledge to discern "the right way of attaining the realiza-tion of their ideals" (1945.139).

If culture necessarily involves incarceration, there is oneclass of players that is uniquely qualified to break out ofjailanthropologists. For each of the three spheres that ren-der people subject to tradition, Boas proposes a theoreticaland methodological basis for developing the reasoned andcritical perspective that he deemed necessary for productionof free and enlightened citizens. First, identifying the broaderframework of human possibilities constitutes a major goal ofanthropological endeavor. Boas argues that "a critical exami-nation of what is generally valid for all humanity and what isspecifically valid for different cultural types comes to be a

atter of great concern to students of society" (1940c:261),Learning which attitudes are "universally human" preparesnthropologists for determining which "specific forms" theyake in each society (Boas 1940c:262). Anthropological train-ing pushes students to overcome the universal tendency "toonsider the behavior in which we are bred as natural for all

mankind" (Boas 1962:206).A "purely analytic" approach to the study of particular

anguages and cultures enables anthropologists to circum-he natural tendency to project one's own categories

o others. Boas argues that "the scientific study of general-social forms requires, therefore, that the investigator free

self from all valuations based on our culture. An objec-e, strictly scientific inquiry can be made only if we succeed

tering into each culture on its own basis" (1962:4-205). Culture becomes an object of knowledge for an-ropologists and their means of developing epistemologicalpolitical freedom at the same time that it constitutes the

pal obstacle to objective knowledge, rationality, and

freedom from traditional dogma for all others, To be sure,even the adoption of a "purely analytic" approach does notfully shield anthropologists from the principle of distortion(#6), but it does provide them with unique access to objec-tive knowledge of particular cultures, thereby complement-ing their unique access to the domain of "the common prop-erty of mankind." This ability to penetrate alien culturalworlds apparently knows no limits, for it can include every-thing from art, to kinship, to religion, to cooking,

Having established unique access to universal and cul-turally specific domains, anthropologists enjoy privilegedac-cess to the sphere of cross-cultural comparison. By virtue ofits ability to compare a range of types of formal patterns inrelatively abstract principles, linguistics makes unique ele-ments and patterns seem to be naturally comparable to otherunique phenomena. Native American lexical and grammati-cal features could be compared with Greek, Sanskrit, andEnglish, just as the social position of "chiefs of Polynesian Is-lands, kings of Africa, [and] medicine men of many coun-tries" (1962:192) could be compared with the New Yorkelites with whom Boas interacted.

Having discredited the cross-cultural forays of layper-sons, evolutionists, and others as projections of one set ofcategories and values onto others, Boas could assert that an-thropologists are uniquely qualified to compare systems andgeneralize about linguistic and cultural difference. Objectiveand analytic study prepares anthropologists to place a par-ticular culture vis-a-vis others and in relationship to the uni-versal framework on the basis of a "mind relatively uninflu-enced by the emotions elicited by the automatically regulatedbehavior in which he participates as a member of our society"(Boas 1962:207). Classicists, Orientalists, philologists, andhistorians lack a sufficiently broad basis of comparison toachieve this perspective, for what is needed is "the objectivestudy of types of culture that have developed on historicallyindependent lines or that have grown to be fundamentallydistinct" (Boas 1962:207). Differences between "Europeansand their descendants" are slight because a common basis inGreek and Roman culture suggests that "the essential culturalbackground is the same for all of these" (Boas 1962:206). An-thropologists may invite psychologists, sociologists, andother colleagues into the comparative enterprise of deter-mining what is "universally human," but it will be on an-thropological terms and using anthropological data.

To borrow a term from Bruno Latour (1988), Boas at-tempted to fashion anthropology into an obligatory passagepoint for academic and popular debates regarding the poli-tics of difference and human nature. Admitting that anthro-pologists could not predict what was going to happen or en-gage in experimentation (1962:215), Boas did not try tomake anthropology into an "exact" or "experimental" sci-ence, On a number of occasions, he similarly expresseddoubt that cultural phenomena could be reduced to laws or"to a formula which may be applied to every case, explainingits past and predicting its future" (194Oa:257). Rather thanlimiting the scope of anthropological authority, however,this mine expanded it. If anthropological expertise were

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

9/18

Briggs Linguistic Magic Bullets 4 8 9reduced to a formula, it could be easily decontextualized andused by other specialists or laypersons, persons who had notbeen transformed by anthropological training and fieldwork.Boas suggests in a number of popular works that theunique ability of the anthropologist to reach "a standpointthat enables him to view our own civilization critically , . .and to enter into a comparative study of value" (1962:207) isneeded to counter racism and war and to secure democracyfrom majoritarian and state censorship. Rather than provid-ing laws or formulas, th e anthropologist's d uty is "to watchand judge day by day what we are doing, to understand w hatis happening in the light of what we have learned and toshape our steps accordingly" (Boas 1962:245). He states inthe introduction to Race and Democratic Society that "a newduty arises. No longer can we keep the search for truth aprivilege of the scientist. We must see to it that the hard taskof subordinating the love of traditional lore to clear thinkingbe shared with us by the larger and larger masses of our peo-ple" (1945:1-2). Teaching the masses was clearly a primarymission of the anthropolog ical m useum (Boas 1907). Boas ar-gues that "the task of weaning the people from a complacentyielding to prejudice" (1945:2) involves a process of resociali-zation in which unquestioned emotional attachment to tra-dition is replaced during childhood by a critical weighing ofcultural alternatives. Anthropologists thus need to guidewhat takes place in hom es and schools as well as in domesticand foreign policy decisions, providing knowledge that canmove societies beyond racism, xenophobia, and war.CULTURAL L IMITS TO ANTHRO POLO GICAL CRIT IQUESOF M O DERN SOCIET YBoas should be lauded for sounding a brave internationalistvoice that challenged privileges of race, nation, and class. Hiscourage in standing up to censorship in the academy and be-yond and in pushing a pacifist agenda during tw o world warsis remarkable. As many anthropologists seek to become pub-lic intellectuals and give anthropology a much stronger voicein policy and m edia debates, we still have a lot to learn fromBoas. As man y progressive academics are attem pting to fostera critical cosmopolitan stance, Boas's attempt to fashion an-thropology asa cosm opolitan discipline deserves broader ap-preciation.5 Some anthropologists demand that we end thestory here, assailing those who dare to critically assess hisoeuvre as attem pting to den igrate the reputation of U.S, an-thropology's most distinguished ancestor. Richard Baumanand 1 were recently attacked in the American Anthropologist byHerbert Lewis (2001) for publishing a reassessment of Boas'stext-making practices (Briggs and Bauman 1999). Lewislaims that our assessment of the Boas-Hunt texts is "harsh"we regard the corpus as "truly harmful" (2001:448).(This is hardly the way we read our argument,)

It seems worthwhile to point out that the m ain thrust ofoas's work is a penetratingly criticalone might even say

criticism violate the very spirit of Boas's academic a nd popu-lar contributions. Indeed, Boas believed that intellectual free-dom and democracy require each generation to reflect criti-cally on what they have been bequeathed; "It is our task no tonly to free ourselves of traditional prejudice, but also tosearch in t he heritage of the past for what is useful and righ t,and to endeavor to free the mind of future generations sothat they may no t cling to our mistakes, but m ay be ready tocorrect them" (1962:200-201). Therefore, suggesting waysthat Boas's linguistic and cultural modeling have dulled theeffectiveness of his critical tools and proposing avenues forrecasting these theoretical principles seem to me to consti-tute a more productive relationship to anthropological schol-arship than attempting to place Boas beyond criticism.

Particularly in his popular work, Boas helps us imagineculture as historical, constructed, and interested. The projectof analyzing it rested, however, on a pre- or extracultural do-main that is not con structed or deconstructable. He says that"it is, therefore, one of the fund amental aims of scientific an-thropology to learn which traits of behavior, if any, are or-ganically determined and are, therefore the common prop-erty of mankind, and which are due to the culture in whichwe live" (1962:206). Language and culture seem ultimatelyto respond to external organic requirements. His phoneticmodel suggests that the spectrum of possible sou nds is deter-mined by the physiology of the vocal apparatus and that theuniversal classification of sound is based on its landscape(lips, tongue, teeth, alveolar ridge, etc.) and the range of itsmovements. The phonetic chart, descendants of which arestill widely used, seems to embody what Foucault (1970)identified as a major drive of m odern science, the search foran exhaustive ordering of th e world, as embodied in th e dis-covery of simple elements and the way they enter into com-binations; at the center of this quest, particularly in th e 17thand 18th centuries, lay the table. Boas also uses the exampleof walking in linking these two domains: That humans walkon their feet is organically determined, but how people in aparticular com mu nity walk is cultural (1962:138). He gener-alizes: "In all these cases the faculty of developing a certainmotor habit is organically determined. The particular form ofmovem ent is automatic, acquired by constant, habitual use"(1962:139). Awareness of this universal grounding for hu-man experiences is open only to members of "educatedgroups" in modern society, and it isnot susceptible to decon-struction. Boas thus, imposes a fundamental limit to U.S. an-thropology's deconstnictive moves as a price for asserting itsown authority and scientific status. If Boas had started withreligion or mythology rather than linguistics, finding thisuniversal basisand particularly its physiological underpin-ningsm ight have been more of a challenge.

If U.S. anthropology's special domain is culture, it is re-markable that Boas constructs it in largeiv negative terms. Ifanthropology's job is to break " the tetters of tradition." it ad-vances the process of constructing modern subjects laid outby John Locke (1959) and o thers in th e 17th ce ntury an d re-invigorated by lmmanuel Kant (19S6) in the late 18th. An-thropology's valui' for critiquing notions of modernity and

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

10/18

9 0 American Anthro pologist Vo l, 104, No. 2 June 2002rationality and for disrupting their use in creating and natu-ralizing schem es of social inequ ality is thu s severely compro-mised. If subaltern subjects cannot develop awareness of thehistorical genesis of either "civilized" or "primitive" catego-ries, their critical insights cannot be used in developing

nthropological challenges to colonialism. The doors of Co-lumbia and other universities were rather more easily accessi-ble to "the educated groups" than to "the masses"; access toanthropological enlightenment was accordingly shaped byclass-based gatekeeping mechanisms. Rather than challeng-ing privilege and social inequality, this conc eption of culturethus opens the door to new modes of producing power andknowledge,

Herein lies a central contradiction in Boas's epistemol-ogy, Languages and cultures are historically shaped and c on-stantly changin g. Nevertheless, rather than emerging as het-erogeneous dimensions of social practices that themselvesbecome objects of scrutiny and contention, languages areconstructed arrangements of sounds, words, and grammati-cal forms that are neatly stuck in each child's head in a placethat is inaccessible to the conscious mind. Silverstein sug-gests that the point-for-point correspondences created be-tween phonological and cultural data and analysis constitute"at best a misleading ca ique in th e first place" (2000b: 14). AsHymes (1983:25) suggests, this model of language leaves lit-tle room for interactive and social dimensions. Early in life,each individual assimilates oneand only onelanguage,and, Boas told us, it is virtually impossible to fully assimilatea secon d o ne later in life.

The view of languages and cultures as entities that c om e"one to a customer" fails to come to terms with the possibil-ity of living in a linguistically and culturally com plex societythat provides individuals and communities with multiple al-legiances. It is remarkable that Boas's ethnographic successcould depend for more than three decades on the multilin-gual and multicultural abilities of George Hunt, who wasaised with overlapping English Canadian, Tlingit, andwakwaka'wakw memberships, without creating a theoreti-

German immigrant of Jewish ancestry did not recognizeing of borders (see Clifford 1997). Boas keenly recognizedhat national languages and their use in legitimizing nation-list projects are recent inventions (1962:91-92), but hepeakers is similarly constructed and that it erases other per-

anthropological border cross-

Zygmunt Bauman (1987) argues that modernity has cre-

lectuals have assumed the task of "legislators" who exercisesurveillance and control over the projected transformation ofpremodern to modern subjects through the production anddissemination of new forms of knowledge, In the 19th cen-tury, these legislators were increasingly professionalized andspecialized, claiming exclusive rights to determine whatcoun ts as kn owledge in a particular dom ain. Boasian anthro-pology could truly become a science, possessing a distinctobject of investigation, methods, and theoretical postulates;the phonological analogy hedged bets by making sure thatits principal source of symbolic capital had the formal, ab-stract, general, and quasi-mathematical features to make itlook like science.

Herein lies, I think, the source of the the crucial linger-ing problems with anthropological constructions of culture.Sahlins (1999 ) an d o ther critics of culture's critics are right inarguing that Boas and h is studen ts do not simply portray cul-ture as boun ded, stable, self-contained, and h omo geneou s. (Iwill attest some crucial linguistic evidence along these linesshortly.) But Boas does suggest that the primordial founda-tion of social life is the socialization of each individual vis-a-vis one language and one culture. The idea that individualscannot understand or deal sympathetically with people so-cialized in other cultures does construct culture as rather co-hesive and bounded. Thus, although Boas describes specificcultures as heterogeneous, shifting, and porous, his charac-terizations of cross-cultural enc oun ters t en d t o present arather less complex view of culture. But the basic problemhere is not the nature of culture but, rather, who possessesknowledge of culture and who is authorized to represent itCulture, for Boas, operates unconsciously; when its bearersattempt to grasp or represent it, they produce distortions.Some of these, like folklore, may be of academic interest asobjects of study (but not tools for analyzing culture). But.Boas told us, mos t are not, and anthro pologists must learn toset native representations aside and come up with their ownanalyses. Sahlins remains true to Boas in asserting that struc-ture holds the key to culture. And "structure," he tells us, "isthe organization of conscious experience that is not itselfconsciously experienced" (1999:413). Models of culture thatmake anthropological authority over culture contingent ondenying it to others are not just politically problem-aticthey fail to take into account the degree to whichBoasian notions of culture have become social facts thatshape ind ividual and c ollective identities and practices of thenation-state.

I would like to propose my own analogy in order to dai-ify the place of linguistics in this project. One of the mostprovocative works in science studies scholarship is Shapinand Schaffer's (1985) analysis of the role of Robert Boyle's airpump In shaping science and society during the 17th cen-tury. Rather than tying scientific authority to grand deduc-tive systems, Boyle located its nexus in the artificial contextof action s performed in a transparent glass containe r locatedat the top ot an apparatus capable of producing a vacuum.The production of scientific facts was tied to wha t too k placein the container, the concurrence of credible witnesses to

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

11/18

Briggs Linguistic Magic Bullets 491these events, and their abstraction and decontextualizationas general principles that could explain how nature workseverywhere and anytime, The air pump thus placed thosewho controlled it in the position of an obligatory passagepoint for the production of scientific knowledge, and it en-abled them to make huge leaps of scale between the particu-lar contexts that they dom inated and th e world at large.

In thinking about th e place of linguistic models in Boas'smodel of culture, this analogy is as interesting for where itfails as for where it succeeds. The fieldwork encounter be-came for anthropology what the air pump was for 17th-century mechanical philosophya means of displacinggrand deductive schemes (particularly those of the evolution-ists) in favor of a mode of producing facts through observation.Fieldwork became a complex set of practices that had to bemastered through professional training; like owning an airpump, controlling access to this pedagogical process enabledBoas and those he trained to regulate the obligatory passagepoints that provided access to cultural knowledge. The anal-ogy begins to break down, however, in tha t the air pum p wasdesigned to produce public knowledge, to open scientificwork to scrutiny by groups of observers. Fieldwork placed thelocus of observation far away from the center. Because "na-tives" were not credible witnesses, being unable to gain con-scious and objective perspectives on what they knew, thelone fieldworker was responsible for making scientific obser-vations.

Convincing skeptical colleagues that these unusual en-counters between strangers produce substantive, reliable in-formation still seems to be a never-ending task. Linguisticslent an aura of science and credibility to these interactions.The phonetic table helped ensure that fieldworkers would re-cord accurately exactly what was said. Fieldwork producedobservations of facts, not speculations about historical orpsychological origins. Their publication , which constituted amajor component of the Boasian program, transformedthem into stable, publicly accessible observations that couldbe subjected to scrutiny, analysis, and comparison, like thecollective observations on what took place in the glass con-tainer. Herein lies, I think, the solution to a question thatseems to have puzzled many readers of Boas: Why did hespend so much time collecting texts, and why did he seethem as so central to anthropological research? Texts couldrum a unique, private encounter into something public andpermanent, and they could transform what had been thepurview of missionaries, colonial civil servants, and otheramateurs into a science.

Linguistics m odeled the way that anthropologists couldovercome the immense problems of scale presented by field-work, Sounds extracted from particular utterances and inter-actions could be compared with those found in any languagein the world, poten tially filling in spaces in the grid along th eay. The same process could be applied to lexical and gram-matical categories and, as Boas repeatedly suggests, to cul-ided Boas with a means of overcoming the issues of ob-ectivity and public accessibility that confronted his efforts to

place fieldwork at the heart of anthropology. It transformedthe perception of anthropology as "a collection of curiousfacts, telling us about the peculiar appearance of exotic peo-ple and describing their strange customs and beliefs" into a"science of m an" tha t "illuminates the social processes of ourown times" (Boas 1962:11).MA GIC BULLETS AN D THE ERASURE OFNONCANONICAL CONSTRUCTIONSBoas was hardly the last practitioner to use the linguistic airpum p in attempting to construct and legitimate a new cul-tural theory. Beginning in the 1950s, Kenneth Pike drew onthe distinction between phonetics and phonem ics in proposing"a unified theory of the structure of human behavior," toquote from the title of his book, based on "etic" and "emic*"approaches to language and culture (1967). Ward Goode-nough (1956) and Floyd Lounsbury (1956) drew on theetic/emic distinction in proposing a theory of culture and amethodology for describing it that "takes one's audience intothe culture of another people and allows it to experience th atculture and to learn something of it from the insider's (thesophisticate's) point of view" (Goodenough 1970.110).6 Levi-Strauss's (1966) appropriation of th e Jakobson-Halle (1956)model of phonology and of Saussure's (1959) scientific re-writing of Locke's (1959) linguistic theory similarly placedanthropology in the academic limelight. In each case, aphonological model is used in infusing analyses in culturalanthropology with greater formal elegance and scientificrigor.

Being assigned to th is task has, however, bequeathed lin-guistics a rather uncertain status in the discipline. Anthro-pologists often still look to their linguistic colleagues formagic bullets when they seek to establish, ex tend, or restorethe discipline's claim to a central place in m odernity.7 Whenlinguists can perform this task, a "linguistic turn"and en-hanced intellectual authority and institutional resourcesisthereward.But when magic bullets do not seem to be neededor linguistic anthropologists are judged to be unable to pro-duce themthey are banished to th e fringe of the discipline.This mode of inserting linguistics in U.S. anthropologyhas created three fundamen tal problems. One is that moder-nity is constantly in flux w ith respect to how it is denned andthe degree to which it generates autho rity. So booms tend tobe transient, and changes in definitions of modernity renderthese shifting targets hard to hit with new magical bullets.Second, many anthropologists are less interested in servingas legislators for the reform projects of modernity than inscrutinizing how anthropology has helped construct moder-nity. If linguistic anthropology's status is limited to produc-ing magic bullets capable of scientizlng the discipline andplacing it at the center of modernist projects, its stock projec-tions are bleak. A third problem lies in the way this processseriously thwarts the integration of linguistically informedthinking within the discipline Fortunately, linguistic an thro-pologists do not always find it necessary these da\ s to gen-erate decontextualized, abstract, ahistorkal, and apolitical

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

12/18

92 American Anthro pologist Vo l, 104, No. 2 June 2002odels of boun ded, discrete bundles of linguistic patterns inrder to succeed in th e anthropological marketplace, even ifare still a lot of practitioners w ho look to their linguisticolleagues for formal models. When they produce nuanced,omplex, historically, and politically grounded under-standings that are based on detailed examinations of dis-course, linguistic anthropologists tend to get labeled as tooempiricist, atheoretical, and particularisticor their work is

simply overlooked.Other dimensions of the work of Boas, Whorf, and par-ticularly Sapir are most illuminating in this regard. I listabove some of the most commonly cited features of Boas'sapproach to language. But he also created other sorts ofanalogies between language and culture, ones that line upmuch more squarely with contemporary theory. Boas writes,"It should be borne in mind that th e vague term 'culture' asused here is not a unit which signifies that all aspects ofculture must have had the same historical fates" (1965:145-146). He suggests that technical inventions, social or-ganization, art, and religion have separate historical trajecto-ries and th at the re is no reason to believe that they "developin precisely the same w ay or are organically and indissolublyconnected" (1965:146). Boas extends the analogy from cul-ture to language, suggesting that "not even language can betreated as a unit, for its phonetic, grammatical and lexico-graphic materials are not indissolubly connected, for by as-similation different languages may become alike in some fea-tures" (1965:146). If this analogy had become th e cornerstoneof anthropological theorizing, M. M. Bakhtin's (1981) viewof language as a heteroglossic, heterogeneous, fragmented,and fundamentally historical object or Arjun Appadurai's(1996) image of the semiautonomous circulation of culturalforms through "ethnoscapes," "technoscapes," "financescapes,""mediascapes," and "ideoscapes" might not have seemed sonovel. Boas critiqued the use of language in nationalist pro-jects more than half a century before Benedict Anderson(1991) pointed to the "imagined" character of the language-nation connection.In the case of Benjamin Lee Whorf, Gumperz (Gumperznd Levinson 1996), Hill and Mannheim (1992), Lucy1992), and Silverstein (1979, 2000a) have suggested that

hem to a so-called linguistic relativity hypothesis. The ten-

ative contexts in which certain is-and phrases, the discursive practices used in constitut-

ceptions of culture, then the sorts of questions regardingpower, authority, technology, and elite control over discur-sive practices and the way they structure perceptioninshort, Bourdieu's (1991) notion of symbolic capitalmighthave become part of the way that culture was commonly in-vestigated in th e 1930s and 1940s.The range and richness of the linguistic thinking thatgot left on the cutting-room floor of anthropology are per-haps most notable in the case of Edward Sapir. Sapir's lin-guistics helped him develop a theory of culture that Handlerrefers to as "iconoclastic" (1983;210). Handler (1983, 1986)and Darnell (1990) detail the way in which Sapir's thinkingabout language and culture was informed by his pursuits as apoet and musician and by his interest in psychiatry. Sapir'sarticle "Speech as a Personality Trait" (1949g) explores theconstruction of voice and its role in shaping personal identi-ties. For him, the sim ilarity between language and culture liesin their heterogeneity and historical fragmentation or layering:"Language, like culture, is a composite of elements of verydifferent age, some of its features reach ing back into themists of an impenetrable past, others being the product of adevelopment or need of yesterday" (1949i:432). Sapir deems"so-called culture" to be "necessarily something of a statisti-cal fiction," suggesting that the "metaphysical locus towhich culture is generally assigned" is "subtly misleading*(1949b:515-516). He (1949c) sometimes rhetorically jugglesbetween competing definitions of culture in the same article,juxtaposing the "technical" definition used by the ethnolo-gist with other varieties.Rather than viewing human communities as relativelyhomogeneous, unified, and bounded entities, Sapir was in-terested in units ranging from a crowd tha t gathered after anautomobile accident to transnational links between scien-tists, and he (1949e:15-16) draws our atten tion to the crucialrole that language plays in constituting groups and regulat-ing mem bership in the m. He defines "society" as "a culturalconstruct which is employed by individuals who stand in sig-nificant relations to each other in order to help them in theinterpretation of their behavior" (1949b:515). Therealworld,including notions of culture and society, had becom e a pow-erful fiction that is "to a large extent unconsciously built upon the language habits of the group" (Sapir 1949h:lb2); un-like Boas, he does not seem to have privileged anthropolo-gists' constructions.Sapir contrasts the cultural anthropologist's notion ofculture, "essentially a systematic list of all the socialiy inher-ited patterns of behavior which may be illustrated in the ac-tual behavior of all or most of the indhiduals of the group. uwith the ways that individuals understand their relationswith other human beings (1949b:515). Individuals partici-pate in multiple subcultures that are internally heterogene-ous. Constructing languages as "cultural deposits" did leadSapir to follow Boas in suggesting that "the culture of theseprimitive folk has no t advanced to the p oint w here it is of in-terest to them to torm abstract conceptions of a philosophi-cal order" (1949d: 154). Nevertheless, it also prom pted him tochallenge Boas's celebration of the role of philosophy and

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

13/18

Briggs Linguistic Ma gic Bullets 493science in rationalizing Western society by arguing that phi-losophers become dupes as they project the linguistic moldsin which they operate as "cosmic absolutes" (I949d:157), acritique that Whorf further developed (Carroll 1956).Languages could be shaped by competing structuralprinciples that wage constant battles, fought out in millionsof individual utterances.8 Sapir's classic article "Male and Fe-male Forms in Yana" describes how a special set of forms isused when men speak only to men, going on to concludethat "possibly" these pa tterns provide a mean s of subordinat-ing women (1949e:212), His article "Abnormal Types ofSpeech in Nootka" describes an elaborate grammatical andphonological machinery used in implicitly depicting (oftenin derogatory ways) the physical characteristics of the personspoken to or of; Sapir uses this case in suggesting tha t speechis widely used to implicitly construct "status, sex, age, orother characteristics" (1949a), that is, both difference anddifferential power.My point is not that Sapir anticipated all of poststructu-ralist or postmodern theory. Nor do I wish to po int a know-it-all finger at nonlinguistic anthropologists. As LeonardBloomfield's (1933) blend of Saussurean structuralism, Vi-enna positivism, and American behaviorism swept throughthe United States, linguists failed to respond to the radicalchallenge offered by Sapir's theory of language, just as cul-tural anthropolog ists failed to take his cultural iconoclasm toheart. The work of Noam Chomsky (1965) and Claude Levi-Strauss (1966) did not improve the situation. But Roman Jak-obson (1960) and Dell Hymes (1962) drew on the suppressedinsights of Boas, Sapir, and others in inducing m any linguis-tically oriented practitioners to adopt poetic and sociolin-guistic vantage points and to see languages as loci of hetero-geneity, agency, and creativity. Some social and culturalanthropologists have paid close attention to these more com-plex ways of thinking about language, as Pierre Bourdieu's(1991) and Emily Martin's (1994) highly productive re-read-ings of sociolinguistics and the ethnography of communica-tion suggest. Unfortunately, other anthropologists some-times still look to their linguistic colleagues for the sorts offormal, reductionist models of language that are least com-patible with an understanding of culture as constructed, h et-erogeneous, polyglossic, and hybrid and as both a productand a producer of difference and inequality. Linguistic an-thropologists are often still asked to com e up with magic bul-lets,REINSERTING L INGUISTICS INTO A CRIT ICALANT HROPOL OGYThis reductionism has exerted institutional effects. Many de-partments of anthrop ology in the United States that claim tobe four field often end up having one or m ore of their quad-rants missing, and linguistics is most likely to be the lost ter-rain. A decade ago, chairs folded as linguistic anthropologistswere often replaced with other types of practitionersorwere not replaced at all.9 But recent work is beginning tochange perceptions of what linguistic anthropologists do and

the value of their work for other areas of inquiry. My goal isnot to survey that research here, but I would like to point o uta few of the most compelling contributions of this work to-ward reconceptualizing language and culture.10Linguistic anthropologists and other practitioners haveradically questioned the assumptions that form the concep-tual and m ethodological foundations of the "linguistic anal-ogy." Language has come to be seen less as an object th at ex-ists prior to and independ ently of efforts to study it and moreas an ideological field that shapes academic, social, and po-litical projects. In a number of publications, Michael Silver-stein (1979, 1981, 1985) points to the language ideologiesthat shape how peopleincluding linguiststhink aboutand use language. A num ber of collections have outlined thepower of language ideologies in generating and legitimizingschemes of governmentality and structuring everyday life(see Kroskrity 2000; Schieffelin et al. 1998; Woolard and Schief-felin 1994). Bauman and Briggs (in press) argue tha t defininglanguage as a distinct epistemological domain in the 17th cen-tury provided no less important a basis for launching newprojects of knowledge and inequality than fashioning sepa-rate domains of nature/science and society/politics (see La-tour 1987).

When the frame of reference shifts from the con tents oflinguistic and cultural models to their ideological produc-tion, the idea that anthropologists can discern common lin-guistic and cultural patterns that are "universally human*'fits neatly in to wh at Chakrabarty (2000) refers to as the "de-provincialization" of Europe, the projection of a particularset of elite categories as valid for all peoples and times, Thenotion of a universal linguistic framework, as defined byphonetic, lexical, and grammatical commonalities, is basedon the idea that language can be neatly separated from thatwhich is nonlinguistic, supposedly including culture and so-ciety (see Hill and Mannheim 1992). Hymes's (1974) "eth-nography of speaking" and Silverstein's (1976) "metaprag-matics" point to the ideological work that needs to be doneto reduce vast arrays of sign types and ideological repre-sentations to th e Lockean vision of language as sets of refer-entially defined signs, tha t is, stable pairings of forms and ref-erents. Hymes has suggested that "it is only in our owncentury, through the decisive work of Boas, Sapir, and othe ranthropologically oriented linguists, tha t every form ofhum an speech has gained th e 'right,' as it were, to co ntributeon equal footing to the general theory of human language"(1980:55). But, although Boas may have incorporated NativeAmerican content, he deprovincialized a familiar Euro-American ideology of language.

Recent work in linguistic anthropology similarly chal-lenges the assumptions that shored up Boas's notion of a"purely analytic" approach to indi\idual languages and cul-tures. Practitioners have detailed the role that Herderian as-sumptionsregarding he shaping of each individual and col-lective identity through a single linguistic and cultural systemhave played in creating nation-states and colonial societies andother projects for producing and managing social inequal-ity." Beyond disproving the notion that multilinjjualism is

-

8/8/2019 Linguistic Magic Bullets, AA

14/18

494 American Anthropologist Vol.104, No. 2 June 2002unusual orpathological, they have explored the contempo-rary uses of Herderian ideologies in public policies and every-day practices tha t subordinate or exclude people with multi-ple linguistic and cultural identifications.12 Similarly, theideologies and power relations that underlie the notion thatother people's linguistic andcultural worlds can bepene-trated, ordered, and rendered transparent for scholarly audi-ences have been scrutinized. Briggs (1986, 2002b) and Ci-courel (1982) point to the power that interviews affordresearchers for constructing discourse in ways tha t maximizetheir insertability in to academic publications.Transforming Derrida's (1974) insights into e thnograph-ic studies of the multiplicity of actually observed literaciesand their diverse social functions, linguistic anthropologistshave detailed the political power that follows from the con-struction of such practices as dictation, transcription, and theentextualization of ethnographic knowledge as transparentand neutral (see Collins 1995; Samarin 1984). As Schieffelinsuggests, the social effects of literacy practices "take o n pow erby virtue of those who control the resources and set theparticipant structure" (2000:321); the content of texts is thusinseparable from the contexts of their production. Hill(1999) points out that anthropologists' textual ideologiesand practices have often conflicted with those of the com-mun ities in w hich they worked. As Boas's example suggests,our entextualization procedures render our control of theprocess and its resistance by our collaborators largely invis-ible (seeBerman 1996; Briggs and Bauman 1999; Maud2000). And Bakhtin's (1981) work has inspired great interestin the discursive complexity and the social and politicalpower that accrue to techniques for decontextualizing andrecontextualizing texts (see Bauman andBriggs 1990; Shu-man 1986; Silverstein and Urban 1996). These contributionsenables us to see the complex ideological work that Boas per-formed in re-presenting Hunt's and other texts inpublishedcollections and inmaking them seem comparable toothertextual corporathat is, in enabling anthropologists to makecultures and make them seem both analogous toand ut-terly distinct fromother cultures.

O N C L U S I O NMy point is not that Boas got language wrong and that wehave now got it right, 1 am, rather, interested in the questionith which I begin this articlethe problems associated with

of culture and how they are used in the academy,state institutions, and everyday life. Some of the m ost prob-of constructions of cultureas bounded ,in the head, unconscious, deterministic, andinpart, through par-of language, The ideological work that

and relations of inequality. Boas, of course, was af n ationalism ami imperialism, and his social-and sense of social justice ledhim tocritici/c-of social inequality. The political conservatismof the language Ideologies that helped