Learning and Instruction · a conflpeer climate is likely an important social-contextual...

Transcript of Learning and Instruction · a conflpeer climate is likely an important social-contextual...

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Learning and Instruction

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/learninstruc

An intervention to help teachers establish a prosocial peer climate inphysical education☆

Sung Hyeon Cheona, Johnmarshall Reeveb,∗, Nikos Ntoumanisc

a Korea University, South KoreabAustralian Catholic University, Australiac Curtin University, Australia

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:Autonomy supportProsocial behaviorAntisocial behaviorPeer climateRandomized control trialSelf-determination theory

A B S T R A C T

When teachers participate in an autonomy-supportive intervention program (ASIP), they learn how to adopt amotivating style toward students that is capable of increasing need satisfaction and decreasing need frustration.Given this, we tested whether an ASIP experience might additionally help teachers establish a peer-to-peerclassroom climate that is capable of increasing prosocial behavior and decreasing antisocial behavior. Forty-twosecondary grade-level physical education teachers (32 males, 10 females) and their 2739 students were ran-domly assigned into either an ASIP or a no-intervention control condition, and their students completed aquestionnaire four times over an academic year to assess their need satisfaction and frustration, task-involvingand ego-involving peer climates, prosocial and antisocial behaviors, and academic success. Teacher participationin the ASIP increased students' T2, T3, and T4 perceived autonomy-supportive teaching, need satisfaction, peertask climate, prosocial behavior, and academic success, and it also decreased students' T2, T3, and T4 perceivedcontrolling teaching, need frustration, peer ego climate, and antisocial behavior. A multilevel structural equationmodeling analysis showed that intervention-enabled increases in T2 peer task-involving climate longitudinallyincreased students' subsequent T3 and T4 prosocial behavior, while the intervention-enabled decreases in T2peer ego-involving climate longitudinally decreased students’ subsequent T3 and T4 antisocial behavior.Autonomy-supportive teaching is therefore a precursor to the establishment of a prosocial-boosting and anantisocial-diminishing peer-to-peer classroom climate.

1. Introduction

Prosocial behavior is action taken to benefit others or to promoteharmonious relationships (Bergin, 2018). In physical education (PE)classes, benefitting others takes the form of helping, sharing, providingencouragement, and including a classmate in one's activities, whilepromoting harmonious relationships takes the form of cooperating,making peace, showing respect, and standing up for a classmate(Caldarella & Merrell, 1997; Greener & Crick, 1999). To warrant the“prosocial” label, such acts of benevolence and social harmony need tobe intentional and volitional and not just a response to a teacher'smandate or the promise of an extrinsic incentive (Stukas, Snyder, &Clary, 1999). Such prosocial behavior is important to students' socialfunctioning, but it is further educationally important because it is as-sociated with indicators of academic success, such as math and reading

test scores (Adams, Snowling, Hennessy, & Kind, 1999; Miles & Stipek,2006) and longitudinal gains academic achievement (Caprara,Barbaranelli, Pastorelli, Bandura, & Zimbardo, 2000).

1.1. Increasing students’ prosocial behavior

While common in most classrooms, prosocial behavior neverthelessemerges mostly in an “if, then” fashion—with the “if” being the pre-sence of supportive teachers and classmates (Gregory & Ripski, 2008).When schools introduce educational programs to increase students’capacity to understand and support one another, then both prosocialbehavior and academic success tend to rise (Durlak, Weissberg,Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011).

In the present study, we sought to expand our understanding of theclassroom conditions that enhance prosocial behavior. One such

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101223Received 13 June 2018; Received in revised form 9 May 2019; Accepted 29 June 2019

☆ This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2018S1A5A2A03036395).This research was supported by Korea University Future Research Grant: 2018.09.01- 2019.07.31.

∗ Corresponding author. Institute of Positive Psychology and Education, North Sydney Campus, 33 Berry Street, 9th Floor, Sydney, 2060, Australia.E-mail address: [email protected] (J. Reeve).

Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

0959-4752/ © 2019 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

T

classroom condition is teacher-provided interpersonal support (Cheon,Reeve, & Ntoumanis, 2018), but another condition may be supportivepeer relationships. For instance, when students learn how to be moresupportive of their peers (e.g., to listen actively, to cooperate), thentheir classmates show greater prosocial behavior (Watkins & Wentzel,2008). Supportive peer-to-peer relationships may also include thelarger “peer climate” (Ntoumanis & Vazou, 2005; Vazou, Ntoumanis, &Duda, 2005). Together, teacher support and a supportive peer-to-peerclassroom climate seem to be additive and complementary (rather thanredundant) in the prediction of positive student outcomes (Joesaar,Hein, & Hagger, 2012); similar findings have been reported in youthsport with respect to coach and peer motivational climates (Vazou,Ntoumanis, & Duda, 2006). Given that peer support predicts prosocialbehavior, then the next question becomes, “How can we create such asupportive peer climate?”

1.2. Autonomy-supportive intervention program

An autonomy-supportive intervention program (ASIP) is a theory-based and carefully-designed intervention to help teachers becomemore autonomy supportive and less controlling toward students duringinstruction (Cheon, Reeve, & Moon, 2012). ASIPs are based on self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017), which proposes that allstudents possess three psychological needs (autonomy, competence,and relatedness) which, when supported, catalyze students' well-beingand adaptive personal and social functioning but, when thwarted, leadto ill-being and maladaptive personal and social functioning. In anASIP, teachers learn how to increase students' need satisfaction duringinstruction and also how to decrease students’ need frustration. Inter-vention-enabled increases in need satisfaction then promote adaptiveoutcomes such as engagement and prosocial behavior, while interven-tion-enabled decreases in need frustration then diminish maladaptiveoutcomes such as disengagement and antisocial behavior (Cheon,Reeve, & Song, 2016b; Cheon et al., 2012, 2018).

An autonomy-supportive motivating style, once adopted by theteacher, can be expected to increase students' prosocial behavior in twoways. First, it enhances students’ autonomy, competence, and related-ness need satisfaction and hence enables greater empathy towardothers, better and more proactive coping with conflict, more positive

emotionality, and acceptance (internalization) of classroom expecta-tions for prosocial behavior (Delrue et al., 2017; Hodge & Lonsdale,2011; Roth, Kanat-Maymon, & Bibi, 2010). Second, an autonomy-sup-portive motivating style allows teachers to establish caring teacher-student relationships and also a caring community environment(Froiland & Worrell, 2017). These caring relationships and classroomenvironments then tend to catalyze prosocial behavior (Solomon,Watson, Delucchi, Schaps, & Battistich, 1988).

1.3. Peer climate

A teacher's autonomy-supportive motivating style is only one part ofthe classroom's motivational climate (Conroy & Coatsworth, 2007), asstudent-to-student interactions and peer relationships add a secondpart. Once perceived and experienced by students, a supportive peerclimate is likely an important social-contextual resource capable ofpromoting adaptive personal, social, and academic functioning, just asa conflictual peer climate is likely an important social-contextual lia-bility capable of promoting maladaptive personal, social, and academicfunctioning (Hodge & Gucciardi, 2015; Smith, 2003). Some evidence inyouth sport suggests that the benefits accrued from these two parts ofthe motivational climate (coach autonomy support, athlete-to-athletepeer climate) are largely independent from one another (Ntoumanis,Vazou, & Duda, 2007).

All studies to date conceptualize (and operationally define) a sup-portive peer climate as a “peer task-involving climate” and a conflictualpeer climate as a “peer ego-involving climate”, drawing from Ames'(1992) achievement goal theory work on motivational climates(Joesaar et al., 2012; Ntoumanis & Vazou, 2005; Vazou et al., 2005).This original work in youth sport has direct relevance for PE. Drawingon and adapting such work, we conceptualized a peer task-involvingclimate as a supportive PE climate in which one's classmates emphasizeimprovement, task mastery, interpersonal inclusion, verbal en-couragement, and working together. Such a task-involving peer climatemay emerge out of teacher-provided autonomy support, out of personalexperiences of need satisfaction, or out of both sources (Jia et al., 2009;Wang, Bergin, & Bergin, 2014). Similarly, we conceptualized a peerego-involving climate as a conflictual PE climate in which one's class-mates emphasize social comparison, normative ability hierarchies, and

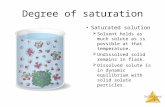

Fig. 1. Categories of instructional behaviors that flow out of an autonomy-supportive interpersonal tone of understanding and support (left side), and categories ofinstructional behaviors that flow out of a controlling interpersonal tone of pressure and coercion (right side).

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

2

interpersonal competition.

1.4. Why greater autonomy support might enable a more prosocial peerclimate

When autonomy supportive, the teacher offers students an inter-personal tone of understanding and acceptance during instruction. Asillustrated on the left side of Fig. 1, this tone communicates to stu-dents—explicitly and implicitly—relationship messages such as, “I amyour ally. I am here to support you and your strivings.” This tone affectsnot only how teachers relate to students but also how students relate toone another, as high-quality teacher-student relationships tend to leadto high-quality student-student relationships (Hendrickx, Mainhard,Oudman, Boor-Klip, & Brekelmans, 2017; Hughes & Kwok, 2006). Thatis, how teachers relate to students serves as a social referent for howstudents relate to each other.

Autonomy-supportive teachers commonly enact prosocial-enhan-cing instructional behaviors, such as perspective taking and empathiclistening (see Fig. 1). Taking perspective and showing empathy gen-erally enable greater prosocial behavior and lesser antisocial behavior(Miller & Eisenberg, 1988). Autonomy-supportive teachers also enactinstructional behaviors to satisfy students' psychological needs and topromote their volitional internalization of adaptive ways of behaving(see Fig. 1). Specifically, to help students internalize teacher-re-commended adaptive ways of behaving, autonomy-supportive teachersacknowledge and accept students’ behavioral resistance and expres-sions of negative emotionality, provide explanatory rationales for theirrequests, use invitational language, and display patience (Deci et al.,1994). Because such autonomy support fuels both need satisfaction andinternalization, such a motivating style tends to foster greater prosocialbehavior (Cheon et al., 2018).

In addition to our focus on prosocial behavior, we also focused onstudents' academic success in the course. The addition of this secondoutcome measure allowed us to test whether teacher participation inthe ASIP would increase not only students' adaptive social functioning(i.e., prosocial behavior) but also students’ adaptive personal func-tioning (i.e., academic success). We further wanted to test if ASIP-en-abled gains in need satisfaction and a supportive peer climate mightpredict these two outcomes selectively (e.g., need satisfaction mightpredict personal but not necessarily social functioning, while peer cli-mate might predict social but not necessarily personal functioning).

1.5. Dual-process model

Self-determination theory highlights two parallel processes thatunderlie students' adaptive and maladaptive motivation and func-tioning (Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch, & Thogersen-Ntoumani, 2011a), including PE students' adaptive and maladaptivemotivation and functioning (Gunnell, Crocker, Wilson, Mack, & Zumbo,2013; Haerens, Aelterman, Vansteenkiste, Soenens, & Van Petegem,2015). On the one hand, autonomy-supportive teaching vitalizes the“brighter side” of students' motivation and functioning (e.g., need sa-tisfaction, classroom engagement), while teacher control galvanizes the“darker side” of students' motivation and functioning (e.g., need frus-tration, classroom disengagement). SDT researchers therefore propose adual-process model in which different aspects of a teacher's motivatingstyle (autonomy supportive vs. controlling) set in motion two parallelstudent trajectories of more adaptive and less maladaptive motivationand functioning (Jang, Kim, & Reeve, 2016).

To better understand how lesser maladaptive motivation mightcontribute to lesser maladaptive functioning, we focused on students'need frustration and antisocial behavior. Antisocial behavior is actiontaken to harm others or to promote conflictual relationships (Bergin,2018). In PE and sport, harming others takes the form of verballyabusing, criticizing, hitting, injuring, pushing and shoving, excluding aclassmate from one's activities, and damaging a classmate's equipment,

while promoting conflictual relationships takes the form of annoyingone's classmates, generating conflict and hostility, showing dis-respect—to people and to property, intimidating, being rude andaversive, rejecting, attacking, and enacting disruptive and destructivebehavior (Birch & Ladd, 1998; Kavussanu & Boardley, 2009). By fo-cusing on both prosocial and antisocial behavior, we sought to in-vestigate whether teacher participation in the ASIP would not onlyincrease students' adaptive (bright side) social functioning but alsodecrease students' maladaptive (dark side) social functioning.

When controlling, the teacher offers an interpersonal tone of pres-sure and coercion during instruction. As illustrated on the right side ofFig. 1, this tone communicates relationship messages to students suchas, “I am your boss. I am here to socialize and to change you and yourbehavior.” The controlling teacher takes only his or her perspectiveduring instruction and pressures students to think, feel, and behave in ateacher-prescribed way. Controlling teachers both suppress students'psychological needs and steer them toward teacher-defined desirablebehavior (prescriptives) and away from teacher-defined undesirablebehavior (proscriptives). Specifically, controlling teachers counter andtry to change students’ negative emotionality into something more ac-ceptable to the teacher, utter directives without explanations, rely onpressuring language, and push for immediate compliance. Because suchinterpersonal control generates conflict and defiance in students (VanPetegem, Soenens, Vansteenkiste, & Beyers, 2015), such a motivatingstyle tends to foster greater antisocial behavior (Aelterman,Vansteenkiste, & Haerens, 2019).

1.6. Hypotheses and hypothesized model

Hypotheses. We predicted that teacher participation in the ASIP(experimental group), relative to teacher non-participation (controlgroup), would significantly increase students' post-intervention (T2, T3,and T4) perceived autonomy-supportive teaching, need satisfaction,prosocial behavior, and academic success, and significantly decreasestudents’ T2, T3, and T4 perceived controlling teaching, need frustra-tion, and antisocial behavior.

Hypothesized Model. The hypothesized dual-process model ap-pears in Fig. 2. As shown in the 11 upwardly-slopped lines, experi-mental condition (ASIP participation) was hypothesized to increaseboth T2 need satisfaction and T2 peer task climate. These ASIP-enabledincreases in T2 need satisfaction and T2 peer task climate were boththen predicted to longitudinally increase both T3 prosocial behaviorand T3 academic success. In addition, subsequent increases in T3 needsatisfaction and T3 peer task climate were further predicted to long-itudinally increase both T4 prosocial behavior and T4 academic successin the following semester.

As shown in the 7 downwardly-slopped lines, experimental condi-tion was hypothesized to decrease both T2 need frustration and T2 peerego climate. These ASIP-enabled decreases in T2 need frustration andT2 peer ego climate were then both predicted to longitudinally decreaseT3 antisocial behavior. In addition, subsequent decreases in T3 needfrustration and T3 peer ego climate were predicted to longitudinallydecrease T4 antisocial behavior.

It is also possible that intervention-enabled increases in T2 peer taskclimate might predict increases in T3 need satisfaction and that inter-vention-enabled decreases in T2 peer ego climate might predict de-creases in T3 need frustration. Because of this possibility, we addedthese later two paths (T2 peer task climate → T3 need satisfaction; T2peer ego climate → T3 need frustration → status) to the test of theoverall model.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Teacher-Participants. Teacher-participants were 42 full-time

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

3

certified PE teachers (32 males, 10 females) who taught in one of 42different schools (33 middle, 9 high schools) dispersed throughout theSeoul metropolitan area in South Korea. All teacher-participants wereethnic Korean. Teachers on average had 6.9 years of PE teaching ex-perience (SD=3.8; range=1–16) and were, on average, 35.0 years old(SD=4.6; range=28–45). All 42 teacher-participants completed allaspects of the study, and each teacher-participant received theequivalent of $100 at the end of the study.

Student-Participants. Student-participants were the 1429 (52.2%)females and 1310 (47.8%) males in the classrooms of the 42 partici-pating teachers. Of these 2739 students, 2219 (81.0%) were middleschool students while 520 (19.0%) were high school students; 1376(50.2%) were students of teachers in the experimental condition while1363 (49.8%) were students of teachers in the control condition. Onaverage, students were 14.8 years old (SD=1.3, range=13 to 18).

2.2. Procedure and implementation of the ASIP intervention

The research protocol was approved by the University ResearchEthics Committee of the first author's university. Prior to the data col-lection, we obtained permission to conduct the study from each schoolprincipal and each teacher. Prior to completing their questionnaires,students completed a consent form. To respect the school principals'preferred procedure, we used the passive consent procedure for parentsto allow their adolescents to participate in the study.

We recruited PE teachers to participate in a semester-long study on“classroom instructional strategies.” Teachers were randomly assignedinto either the experimental (ASIP intervention; n=20) or control (nointervention; n=22) condition. The procedural timeline for the year-

long intervention and the four waves of data collection appear in Fig. 2.For teachers in the experimental conditions, we delivered the ASIP inthree parts.

Part 1 of the ASIP was a 3-h morning workshop that took place inthe weeks before the start of the academic year (i.e., spring semester). Itintroduced autonomy-supportive teaching, contrasted it against con-trolling teaching, offered empirical evidence on the benefits of au-tonomy support and the costs of control, and introduced (via PPT slidesand brief videos) each of the following recommended autonomy-sup-portive instructional strategies: Take the students' perspective; supportstudents' psychological needs during instruction; acknowledge and ac-cept students’ expressions of negative affect; provide explanatory ra-tionales for teacher requests; rely on invitational language; and displaypatience.

Following Part 1 and a lunch break, Part 2 was a 3-h afternoon “howto” workshop to help teachers develop, refine, and personalize theteaching skill needed to deliver the six recommended autonomy-sup-portive instructional behaviors in their own classrooms. Teachers re-ceived hands-on modeling, guidance, practice, and corrective feedbackfor each instructional behavior. Most of the “how to” workshop in-volved teaching simulations in which teachers enacted each re-commended instructional behavior in the context of small groups whilereceiving guidance from the workshop administrator and from theother teacher-participants. During the Part 2 skill-building training,teachers learned how to restructure their existing controlling instruc-tional behaviors (e.g., use pressuring language, neglect to provide ex-planatory rationales) into alternative autonomy-supportive instruc-tional behaviors (i.e., use invitational language, provide explanatoryrationales for teacher requests).

Fig. 2. Hypothesized model. Upwardly- and downwardly-slopped lines represent hypothesized paths. Horizontal lines represent stability effects.

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

4

Overall, teachers learned how to (1) involve and satisfy students'psychological needs during a learning activity and (2) help studentsinternalize the value, importance, or usefulness of a more adaptive wayof functioning whenever they struggled with a problem such as disen-gagement, poor performance, or disruptive behavior. For instance,teachers learned how to support students’ autonomy by taking theirperspective (e.g., “What about this lesson is most interesting to you?“),by providing opportunities for students to pursue their interests andgoals (e.g., “What would you like to do?“), and by revealing to studentsthe personal usefulness of a more adaptive way of behaving that theywere not necessarily aware of (e.g., “The more you use respectful lan-guage, the better your friendships will be.“).

Part 3 was a 2-h peer-to-peer group discussion that took place in thesixth week of the spring semester. During the group discussion, teachersshared their classroom experiences and exchanged tips, suggestions,strategies, and teacher-to-teacher insights on how to better implementeach autonomy-supportive instructional behavior in their own class-room with their own students.

As to the data collection, it was conducted in four waves in whichstudents completed the same 4-page questionnaire at the beginning (T1;week 1), middle (T2; week 10), and end (T3; week 19) of the springsemester and once again at the end (T4; week 44) of the fall semester.The survey was administered at the beginning of the class period, andstudents completed the questionnaire in reference to that particular PEteacher and that particular PE class. The questionnaire began with aconsent form, and students were assured that their responses would beconfidential.

2.3. Measures

Except for course grade (that used a 0–100 scale), each student-reported dependent measure used the same 7-point Likert scale thatranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). For each ques-tionnaire, we had available to us a previously back-translated andKorean-validated version of each English-language questionnaire(Cheon, Hwang et al., 2016a; Cheon & Song, 2011).

Perceived Autonomy Supportive and Controlling Teaching. Weassessed perceived autonomy-supportive teaching with the 6-item ver-sion of Learning Climate Questionnaire (LCQ; Williams & Deci, 1996).The LCQ includes items such as, “My PE teacher listens to how I wouldlike to do things.” The LCQ has been used in the PE context to assessperceived autonomy support and to predict students' need satisfaction(Jang, Kim, & Reeve, 2012). Students' reports of perceived autonomysupport were internally consistent across the four waves of data col-lection (αs at T1, T2, T3, and T4 were 0.88, 0.92, 0.93, and 0.94, re-spectively). We assessed perceived controlling teaching with the 4-itemControlling Teacher Scale (CTS; Jang, Reeve, Ryan, & Kim, 2009). TheCTQ includes items such as, “My PE teacher puts a lot of pressure onme.” The TCQ has been used in previous studies to assess controllingteaching and to predict students' need frustration (Jang et al., 2016).Students’ CTS scores were internally consistent in each assessmentperiod (αs= 0.80, 0.85, 0.85, and 0.86).

Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration. We assessedstudents’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction withthree separate scales, each of which has been used extensively in pastPE research. We assessed autonomy satisfaction with the 5-itemPerceived Autonomy scale (Standage, Duda, & Ntoumanis, 2006). Asample item is, “In this PE class, I feel that I do PE activities because Iwant to.” (αs were 0.85, 0.90, 0.92, and 0.93). We assessed competencesatisfaction with the 4-item Perceived Competence scale from the In-trinsic Motivation Inventory (McAuley, Duncan, & Tammen, 1989). Asample item is, “I think I am pretty good at physical education.” (αswere 0.88, 0.91, 0.91, and 0.92). We assessed relatedness satisfactionwith the 5-item Perceived Relatedness scale from the Basic Needs Sa-tisfaction Scale (Ng, Lonsdale, & Hodge, 2011). A sample item is, “Ihave close relationships with others in my PE class.” (αs were 0.81,

0.89, 0.92, and 0.93).We assessed students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness

frustration with the 12-item Psychological Need Thwarting Scale(PNTS; Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, & Thøgersen-Ntoumani,2011b). The PNTS includes three 4-item subscales to assess autonomyfrustration (“In PE class, I feel pushed to behave in certain ways.“; αswere 0.77, 0.86, 0.88, and 0.90), competence frustration (“In PE class,there are situations where I am made to feel inadequate.“; αs were 0.87,0.92, 0.93, and 0.94), and relatedness frustration (“I feel rejected by myPE teachers.“; αs were 0.90, 0.94, 0.95, and 0.95). The PNTS has beenused previously in the PE context (Hein, Koka, & Hagger, 2015).1

2.3.1. Peer task-involving and peer ego-involving climatesTo assess students' perceptions of the quality of the classroom peer

motivational climate, we used an adapted version the Peer MotivationalClimate in Youth Sport Questionnaire (PeerMCYSQ; Ntoumanis &Vazou, 2005). We adapted the PeerMCYSQ by referring to the PE (ra-ther than to the competitive sport) context and also by referencing“classmates” and “students” (rather than “teammates”). The 5-scale, 21-item PeerMCYSQ features three subscales to assess peer task-involvingclimate (improvement, effort, and relatedness support) and two sub-scales to assess peer ego-involving climate (ability, conflict). For thepeer task-involving climate, we did not include scores from the relat-edness support scale because they overlapped substantially with ourmeasure of relatedness need satisfaction discussed above (a decision wemade prior to analyzing the data). So, for peer task-involving climate,we used the 4-item improvement scale (e.g., “In this class, most stu-dents work together to improve the skills they don't do well”;αs= 0.90, 0.95, 0.96, and 0.97) and the 5-item effort scale (e.g., “Inthis class, most students set an example by giving forth maximum ef-fort”; αs= 0.88, 0.93, 0.94, and 0.95). For the peer ego-involving cli-mate, we used the 5-item ability scale (e.g., “In this class, most studentsencourage each other to outplay their classmates”; αs= 0.80, 0.85,0.86, and 0.88) and the 4-item conflict scale (e.g., “In this class, moststudents make negative comments that put their classmates down”;αs= 0.89, 0.93, 0.95, and 0.96).2

Prosocial and Antisocial Behavior. To assess students' prosocialand antisocial behaviors, we used a slightly adapted version of theProsocial and Antisocial Behavior in Sport Scale (PABSS; Kavussanu &Boardley, 2009), as we changed the scale's original referents of“teammate” and “opponent” to “classmates” (because our study tookplace in the context of PE instruction rather than in the context ofcompetitive sports). The 4-scale, 20-item PABSS features two subscalesto assess prosocial behavior and two subscales to assess antisocial be-havior. For prosocial behavior, we used the 4-item prosocial teammatescale, which we refer to as “encourage”, (e.g., “encouraged a class-mate”; αs= 0.90, 0.93, 0.94, and 0.94) and the 3-item prosocial op-ponent scale, which we refer to as “help”, (e.g., “helped an injuredclassmate”; αs= 0.71, 0.79, 0.82, and 0.86). For antisocial behavior,

1 To check that participants could distinguish need satisfaction from (low)need frustration, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis featuring 2 fac-tors (satisfaction, frustration) and 6 indicators (autonomy satisfaction, compe-tence satisfaction, relatedness satisfaction, autonomy frustration, competencefrustration, and relatedness frustration). Participants made this satisfaction vs.frustration distinction reasonably well at T2: X2 (48)= 440.62, p < .001,RMSEA=0.092 (90% CI=0.085 to 0.101), SRMR=0.022, CFI=0.969,NNFI=0.971. The correlation between the satisfaction and frustration latentfactors was −0.48.

2 To check that participants could distinguish task-involving from (low) ego-involving climates, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis featuring 2factors (task-involving, ego-involving) and 4 indicators (improvement, effort,ability, conflict). Participants made this task vs. ego distinction reasonably wellat T2: X2 (19)= 136.44, p < .001, RMSEA=0.080 (90% CI= 0.068 to0.093), SRMR=0.003, CFI=0.976, NNFI=0.977. The correlation betweenthe task-involving and ego-involving latent factors was −0.56.

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

5

we used the 4-item antisocial teammate scale, which we refer to as“argue”, (e.g., “verbally abused a classmate”; αs= 0.84, 0.87, 0.84, and0.86) and the 8-item antisocial opponent scale, which we refer to as“fight”, (e.g., “tried to injure a classmate”; αs= 0.84, 0.89, 0.89, and0.90). For all four measures, students self-reported the extent to whichthey engage in such behaviors with their classmates. The PABSS hasbeen used in both the sports and PE contexts (Cheon, Hwang et al.,2016a; Ntoumanis & Standage, 2009).3

Academic Success. To assess academic success, we measured bothperceived skill developed during the course and self-reported expectedcourse grade. For perceived skill development, we used the 4-itemPerceived Skill Development scale (PSD; Cheon et al., 2012) that in-cludes items such as “I have learned new and important skills duringthis PE class.“; αs were 0.93, 0.95, 0.96, and 0.97). For expected coursegrade, students completed the following single item to assess their an-ticipated achievement at the beginning, middle, and end of the springsemester and again at the end of the fall semester: “In this PE class, Iexpect my course grade will be ___ points (enter a number between 0and 100).” This same measure has been used in prior longitudinal re-search (Jang et al., 2012).

Raters' Scoring of Teachers' Motivating Styles. Before the datacollection, a team of two undergraduates and two graduates receivedinstruction, training, and practice with rating sheets adapted fromprevious studies (Cheon et al., 2018). During the data collection (weeks10 and 11, see Fig. 3), raters worked in pairs, came to the class un-announced 5–10min before its start, did not know into which group(experimental or control) the observed teacher had been randomly as-signed, and made independent ratings using a pair of 1–7 unipolarscales (1= not at all, 7= very much). The autonomy-supportiveteaching rating sheet listed the following six instructional behaviorsthat the two classroom observers rated in a consistent way: takes thestudents' perspective r (42)= 0.72; vitalizes students' psychologicalneeds, r=0.65; provides explanatory rationales, r=0.71; uses in-vitational language, r=0.82; acknowledges and accepts negative af-fect, r=0.78; and displays patience, r=81. We averaged the tworatings into a single score for each behavior and then averaged these sixintercorrelated ratings into one overall “rater-scored autonomy-sup-portive instructional behaviors” score (6-items, α=0.95). The con-trolling teaching rating sheet listed the following six instructional be-haviors: takes only the teacher's perspective, r (42)= 0.58; introducesextrinsic motivators, = 0.46; neglects explanatory rationales, r=0.57;uses pressuring language, r=0.67; counters and tries to change nega-tive affect, r=0.69; and displays impatience, r=0.73. We averagedthe two ratings into a single score for each behavior and then averagedthe six intercorrelated ratings into one overall “rater-scored controllinginstructional behaviors” score (6-items, α=0.94).

Raters' and Students' Agreement. We used observers' ratings andstudents' perceptions of teachers' motivating styles as two independentmanipulation checks of the ASIP manipulation. We checked to seewhether observers' and students' middle-of-semester (T2) ratings cor-responded with each other, and they did. Observers' ratings of teachers'autonomy-supportive instructional behavior scored at the teacher level(n=42, M=4.85, SD=0.71) significantly and rather strongly pre-dicted (i.e., agreed with) students' T2 perceived autonomy-supportiveteaching at the individual student level (n=2,739, M=5.07,SD=0.81): β=0.41, SE=0.05, t (40)= 8.30, p < .001. Similarly,observers' ratings of teachers' controlling instructional behavior scored

at the teacher level (n=42, M=2.94, SD=0.65) significantly butmore modestly predicted students’ T2 perceived controlling teaching atthe student level (n=2,739, M=2.57, SD=1.17): β=0.18,SE=0.09, t (40)= 2.04, p= .049.

2.4. Data analyses

Missing Data. Of the 2739 student-participants, 2407 (87.9%) hadcomplete data across all four waves of the data collection. For thesestudents, missing data were rare (< 0.01%), and they were missing atrandom (Little's MCAR test, X2 (df=1614)=1211.68, ns). To dealwith the 332 missing cases distributed across T1, T2, T3, or T4, we usedthe multiple imputation procedure using the expectation-maximizationalgorithm in SPSS 24 (with 200 iterations).

Multilevel Analyses. We conducted two types of data analyse-s—one to test the individual hypotheses (the effect of experimentalcondition on each of the eight dependent variables), and one to test theoverall hypothesized model.

To test each individual hypothesis, we conducted multi-level ana-lyses using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM software; Raudenbush,Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2011), because the data had a 3-level hierarchical structure with repeated measures (Level 1, 4 waves,N=10,956) nested within students (Level 2, N=2739), nested withinclassrooms (Level 3, k=88), nested within teachers (a cross-classifiedLevel 3, k=42). At level 1 (within student), the longitudinal data al-lowed us to measure students' increase or decrease on each dependentmeasure over the academic year. Accordingly, we entered ‘‘time’’ as anindependent variable (scored as 0, 1, 2, 3). At level 2 (between stu-dents), we entered gender and grade level to function as a pair of groupmean centered covariates. At level 3 (between classrooms, nestedwithin teachers), we entered experimental condition as an un-centeredindependent variable (control group=0, experimental group=1).Finally, and most importantly, we created the hypothesis-testing con-dition× time interaction term as a cross-level predictor (experimentalcondition was a level 3 predictor, time was a level 1 predictor) to testthe extent to which the year-long changes in each dependent measuredepended on experimental condition.4 To estimate effect sizes for theseinteraction effects, we used the independent-groups pretest-posttestdesign test (d IGPP-RAW) that is appropriate for multilevel, repeated-measures group comparisons to determine the magnitude of the changein the dependent variable in the intervention group relative to themagnitude of the change in the control group (Feingold, 2009).5

To test the overall hypothesized model (see Fig. 1), we used mul-tilevel latent variable structural equation modeling (LISREL 9.20 soft-ware; Joreskog & Sorbom, 2015). The measurement model featured 24latent variables (4 latent variables assessed at T1, T2, and T3 and 3latent variables assessed at T1, T2, T3, and T4), including three in-dicators for need satisfaction (autonomy, competence, and relatedness),three indicators for need frustration (autonomy, competence, and re-latedness), two indicators for peer task climate (improvement, effort),two indicators for peer ego climate (ability, conflict), two indicators forprosocial behavior (help, encourage), two indicators for antisocial be-havior (fight, argue), and two indicators for academic progress (per-ceived skill development, expected course grade). To represent the

3 To check that participants could distinguish prosocial from (low) antisocialbehaviors, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis featuring 2 factors(prosocial, antisocial) and 4 indicators (encourage, help, argue, fight).Participants made this prosocial vs. antisocial distinction reasonably well at T2:X2 (19)= 116.87, p < .001, RMSEA=0.073 (90% CI=0.061 to 0.086),SRMR=0.009, CFI=0.980, NNFI=0.981. The correlation between the pro-social and antisocial latent factors was −0.49.

4 For the condition main effects, 5 of 10 effects were statistically significant(perceived autonomy support, psychological need satisfaction, psychologicalneed frustration, prosocial behavior, and perceived skill development). For thetime main effects, all 10 effects were statistically significant (p < .001). For therandom effects test for meaningful classroom-level variance, all 10 effects werestatistically significant (p < .001).

5 IGPP stands for “Independent-Groups Pretest-Posttest”. The formula for thed IGPP-RAW statistic is: d IGPP-RAW = (M CHANGE-T, T4-T1/SD RAW-T at T1) – (MCHANGE-C, T4-T1/SD RAW-C at T1), where M=mean, SD=standard deviation,T= treatment (or experimental) group, C=control group, T4= time 4 (orwave 4), and T1= time 1.

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

6

longitudinal character of the data set, we allowed the between-waveerror terms of each repeated-measures indicator to correlate with itselfat a later time. The eight predictor variables and the two statisticalcontrols (gender, grade level) were allowed to correlate freely at T1.Within T2, T3, and T4, the errors of the within-wave variables wereallowed to correlate. We report the X2 statistic and degrees of freedom,but we relied mostly on multiple indices of fit (Kline, 2011), includingthe root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), the compara-tive fit index (CFI), and the non-normed fit index (NNFI). For RMSEA,values less than 0.08 indicate a good fit; for CFI and NNFI, valuesgreater than 0.95 indicate a good fit (Kline, 2011).

Mediation Analyses. The model depicted in Fig. 2 is a mediationmodel, so we tested for mediation effects. Using Krull and MacKinnon’s(2001) nomenclature, the type of model tested was a 2-1-1 model (i.e.,group-based Level 2 intervention effect predicted the two student-re-ported Level 1 mediators, which predicted each student-reported Level1 outcome). Fig. 2 features six proposed mediators to explain the threeT3 outcomes (i.e., ASIP → T2 need satisfaction, T2 peer task climate →T3 prosocial behavior; ASIP → T2 need satisfaction, T2 peer task cli-mate → T3 academic success; and ASIP → T2 need frustration, T2 peerego climate → T3 antisocial behavior) and six proposed mediators toexplain the same three T4 outcomes (i.e., ASIP → T3 need satisfaction,T3 peer task climate → T4 prosocial behavior; ASIP → T3 need sa-tisfaction, T3 peer task climate → T4 academic success; and ASIP → T3need frustration, T3 peer ego climate → T4 antisocial behavior). Thetypical procedure to test for such mediation effects is to use resamplingmethods to generate bias-corrected confidence intervals, but this con-ventional bootstrapping method cannot be applied to multilevel mod-eling, because the assumption of independence of observations is vio-lated when using nested or clustered data (Preacher & Selig, 2012).Accordingly, we utilized a Monte Carlo approach to resampling thatallowed us to construct the appropriate confidence intervals necessaryto test for the significance of the 12 possible indirect effects. To do so,we used Selig and Preacher’s (2008) web-based utility6 to generate andrun R code for simulating the sampling distribution of each indirecteffect (20,000 values). If the 95% CI from this simulation excludes zero,then the indirect effect test is significant (p < .05).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

Values for skewness and kurtosis for the 40 dependent measures (10dependent measures x 4 waves) were all less than |3|, indicating littledeviation from normality. We tested for any baseline mean differencesbetween the experimental and control conditions. Statistically sig-nificant but small (i.e., effect size) differences emerged for 4 of the 10T1 dependent measures: perceived autonomy-supportive teaching (Ms,4.77 vs. 4.66, t=3.23, p= .001, d=0.12); need satisfaction (Ms, 4.86vs. 4.78, t=2.51, p= .012, d=0.10); need frustration (Ms, 2.44 vs.2.54, t=2.83, p= .005, d=0.11); and peer task climate (Ms, 4.82 vs.4.73, t=2.77, p= .006, d=0.11). We also tested for possible asso-ciations between students’ demographic characteristics (gender, gradelevel) with their baseline scores on the 10 dependent measures. Genderwas associated with 6 measures, while grade level was associated with4. Given these associations (reported in the lower part of Table 2), weincluded gender (females= 0; males= 1) and grade level (middleschool= 0; high school= 1) as covariates (i.e., a statistical control) inall analyses.

We report the effect of the ASIP on the dependent measures in threeways. First, Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics (i.e., means andstandard deviations) for all 10 student-reported dependent measuresbroken down by experimental condition and time of assessment.Second, Fig. 4 graphically illustrates these same group means for thestudy's four outcome measures (prosocial behavior, antisocial behavior,expected course grade, perceived skill development). Third, Fig. 5shows the results of the test of the overall hypothesized model (fromFig. 2).

3.2. Effect of the ASIP on the two manipulation checks

We tested the effectiveness of the ASIP manipulation by assessingteachers’ autonomy support and interpersonal control using both ob-server-scored ratings and student self-reports.

Autonomy-Supportive Teaching. For objectively-scored autonomy-supportive behaviors, observers rated PE teachers in the experimentalgroup as enacting more autonomy-supportive behaviors during class-room instruction than did PE teachers in the control group (Ms, 5.42 vs.

Fig. 3. Procedural timeline for the events included in the delivery of the 3-part intervention and in the 4 waves of data collection. In interpreting the figure, it isimportant to note that the Korean school year begins in March and ends in December.

6 http://quantpsy.org/medmc/medmc.htm.

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

7

4.33), t (40)= 7.99, p < .001, d=2.49. For student perceptions of au-tonomy-supportive teaching, the critical condition× time interaction wassignificant, t (8,070)= 21.23, p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=1.25). As re-ported in Table 1, perceived autonomy-supportive teaching increasedsignificantly for students of the teachers in the ASIP experimentalcondition from T1 to T4 (Δ = +1.04, t=41.02, p < .001, d=1.17),while it decreased significantly (though modestly) for students of theteachers in the control condition from T1 to T4 (Δ=−0.07, t=2.98,p= .003, d=0.08).

Controlling Teaching. For objectively-scored controlling behaviors,observers rated PE teachers in the experimental group as enacting lesscontrolling behaviors during classroom instruction than PE teachers inthe control group (Ms, 2.55 vs. 3.31), t (40)= 4.60, p < .001,d=1.43. For student perceptions of controlling teaching, the criticalcondition× time interaction was significant, t (8,070)= 14.18,p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=0.69). As reported in Table 1, perceived con-trolling teaching decreased significantly for students of the teachers in

the ASIP condition from T1 to T4 (Δ=−0.63, t=22.04, p < .001,d = 0.63), while it increased significantly (though modestly) for stu-dents of the teachers in the control condition from T1 to T4(Δ = +0.06, t=2.17, p= .030, d=0.06).

3.3. Effect of the ASIP on the eight dependent measures

For need satisfaction, the critical condition× time interaction wassignificant, t (8,070)= 24.39, p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=1.14). As re-ported in Table 1, need satisfaction increased significantly for studentsof the teachers in the ASIP condition from T1 to T4 (Δ = +0.87,t=36.98, p < .001, d = 1.06), while it also increased significantly(though modestly) for students of the teachers in the control conditionfrom T1 to T4 (Δ = +0.07, t=2.79, p= .005, d=0.08).

For need frustration, the critical condition× time interaction wassignificant, t (8,070)= 14.26, p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=0.66). As re-ported in Table 1, need frustration decreased significantly for students

Table 1Descriptive statistics for all ten dependent measures broken down by experimental condition and time of assessment.

No Intervention Control Group (N=1363) ASIP Experimental Condition (N=1376)

Dependent Measure Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Time 4 Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Time 4

Perceived Autonomy Support M (SD) 4.77 (0.89) 4.79 (1.00) 4.79 (1.03) 4.70 (1.00) 4.66 (0.89) 5.55 (1.00) 5.60 (1.04) 5.70 (1.00)Perceived Teacher Control M (SD) 2.91 (1.03) 2.88 (1.14) 2.92 (1.11) 2.97 (1.11) 2.86 (1.00) 2.26 (1.15) 2.21 (1.11) 2.23 (1.11)Need Satisfaction M (SD) 4.86 (0.85) 4.94 (0.93) 4.95 (0.92) 4.93 (0.92) 4.78 (0.82) 5.48 (0.93) 5.54 (0.93) 5.65 (0.93)Need Frustration M (SD) 2.44 (0.92) 2.44 (1.08) 2.49 (1.07) 2.55 (1.07) 2.54 (0.93) 2.03 (1.09) 2.02 (1.08) 2.04 (1.08)Peer Task-Involving Climate M (SD) 4.82 (0.85) 4.89 (1.01) 4.93 (1.00) 4.90 (1.00) 4.73 (0.85) 5.54 (1.01) 5.60 (1.00) 5.67 (1.00)Peer Ego-Involving Climate M (SD) 3.44 (1.00) 3.50 (1.18) 3.48 (1.14) 3.48 (1.18) 3.43 (1.00) 3.04 (1.19) 2.92 (1.15) 2.83 (1.18)Prosocial Behavior M (SD) 4.67 (0.89) 4.80 (1.03) 4.76 (1.03) 4.75 (1.04) 4.65 (0.89) 5.31 (1.00) 5.37 (1.04) 5.52 (1.01)Antisocial Behavior M (SD) 2.83 (1.07) 2.93 (1.29) 2.95 (1.26) 2.95 (1.25) 2.88 (1.08) 2.57 (1.30) 2.60 (1.22) 2.54 (1.21)Expected Course Grade M (SD) 80.8 (14.0) 79.5 (14.4) 79.7 (14.3) 80.9 (13.7) 80.0 (14.0) 83.5 (14.4) 85.0 (14.3) 86.8 (13.7)Skill Development M (SD) 4.78 (1.11) 5.00 (1.18) 4.95 (1.14) 4.97 (1.11) 4.73 (1.11) 5.50 (1.18) 5.60 (1.15) 5.71 (1.11)

N=2739 students. M=Mean, SD = Standard Deviation.

Table 2Descriptive Statistics, Unstandardized, and Standardized Factor Loadings Associated with the Dependent Measures in the Measurement Model.

Latent Variable Indicators Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Time 4

M (SD) B SE β M (SD) B SE β M (SD) B SE β M (SD) B SE β

Need Satisfaction1. Autonomy 4.78 (1.01) 1.00 – .89 5.24 (1.14) 1.00 – .93 5.25 (1.15) 1.00 – .932. Competence 4.11 (1.17) .80 .02 .73 4.65 (1.29) .84 .01 .78 4.76 (1.28) .86 .01 .803. Relatedness 4.74 (1.10) .71 .02 .63 5.17 (1.23) .79 .02 .74 5.21 (1.26) .81 .01 .76

Need Frustration1. Autonomy 2.72 (1.02) 1.00 – .84 2.35 (1.18) 1.00 -.91 2.34 (1.16) 1.00 – .942. Competence 2.61 (1.12) 1.01 .02 .86 2.34 (1.28) .99 .01 .90 2.35 (1.25) .97 .01 .913. Relatedness 2.16 (0.98) .91 .02 .76 1.98 (1.13) .96 .02 .87 2.05 (1.14) .95 .02 .89

Peer Task Climate1. Improvement 4.79 (0.92) .94 .02 .79 5.28 (1.20) .96 .02 .86 5.33 (1.19) .93 .01 .862. Effort 4.77 (0.91) 1.00 – .84 5.22 (1.11) 1.00 – .89 5.27 (1.11) 1.00 – .92

Peer Ego Climate1. Conflict 3.12 (1.17) 1.00 – .88 2.93 (1.45) 1.00 – .92 2.86 (1.43) 1.00 – .922. Ability 3.74 (1.10) .71 .02 .63 3.60 (1.33) .73 .02 .67 3.55 (1.33) .73 .02 .67

Prosocial Behavior1. Help 4.46 (0.93) .75 .02 .67 4.92 (1.13) .83 .02 .77 4.95 (1.17) .87 .01 .82 5.05 (1.19) .89 .01 .842. Encourage 4.86 (1.01) 1.00 – .91 5.20 (1.18) 1.00 – .92 5.18 (1.19) 1.00 – .93 5.22 (1.18) 1.00 – .94

Antisocial Behavior1. Fight 2.79 (1.11) 1.00 – .88 2.68 (1.36) 1.00 – .91 2.70 (1.34) 1.00 – .91 2.69 (1.34) 1.00 – .912. Argue 2.94 (1.22) .91 .02 .80 2.84 (1.46) .93 .02 .86 2.89 (1.41) .95 .02.86 2.85 (1.44) .96 .02 .88

Academic Progress1. Skill Development 4.75 (1.09) 1.00 – .78 5.26 (1.20) 1.00 – .89 5.29 (1.21) 1.00 – .89 5.35 (1.20) 1.00 – .872. Exp. Course Grade 80.4 (13.9) .35 .02 .28 81.6 (14.5) .30 .02 .27 82.5 (14.7) .30 .02 .28 84.0 (14.3) .35 .02 .32

Possible range for each variable, 1–7, except Expected Course Grade whose range was 0–100. Note. All Bs are statistically significant (p < .001).

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

8

of the teachers in the ASIP condition from T1 to T4 (Δ=−0.50,t=18.59, p < .001, d = 0.54), while it increased significantly forstudents of the teachers in the control condition (Δ = +0.11, t=4.11,p < .001, d=0.12).

For peer task-involving climate, the critical condition× time inter-action was significant, t (8,070)= 21.23, p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=1.02).As reported in Table 1, peer task climate increased significantly forstudents of the teachers in the ASIP condition from T1 to T4

Fig. 4. Means for prosocial behavior (upperleft panel), antisocial behavior (upper rightpanel), expected PE course grade (lower leftpanel), and perceived skill development(lower right panel) broken down by experi-mental condition and time of assessment.Note. Standard errors for prosocial behavior,antisocial behavior, and perceived skill de-velopment range from 0.03 to 0.04, whilestandard errors for expected course graderange from 0.39 to 0.42.

Fig. 5. Standardized beta weights from the test of the hypothesized model. Solid lines represent hypothesized paths; dashed lines represent statistical controls.

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

9

(Δ = +0.94, t=37.52, p < .001, d = 1.11), while it also increasedsignificantly (though modestly) for students of the teachers in thecontrol condition (Δ = +0.08, t=3.32, p < .001, d=0.09).

For peer ego-involving climate, the critical condition× time interac-tion was significant, t (8,070)= 13.26, p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=0.64).As reported in Table 1, peer ego climate decreased significantly forstudents of the teachers in the ASIP condition from T1 to T4(Δ=−0.60, t=20.20 p < .001, d = 0.60), while it remained un-changed for students of the teachers in the control condition(Δ = +0.04, t=1.59, p= .112, d=0.04).

For prosocial behavior, the critical condition× time interaction wassignificant, t (8,070)= 19.48, p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=0.89). As re-ported in Table 1 and as illustrated in the upper left panel of Fig. 4,prosocial behavior increased significantly for students of the teachers inthe ASIP condition from T1 to T4 (Δ = +0.87, t=33.92, p < .001,d = 0.98), while it also increased significantly (though modestly) forstudents of the teachers in the control condition (Δ = +0.08, t=3.31,p= .001, d=0.09).

For antisocial behavior, the critical condition× time interaction wassignificant, t (8,070)= 8.62, p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=0.42). As reportedin Table 1 and as illustrated in the upper right panel of Fig. 4, antisocialbehavior decreased significantly for students of the teachers in the ASIPcondition from T1 to T4 (Δ=−0.34, t=10.77, p < .001, d = 0.31),while it increased significantly for students of the teachers in the con-trol condition (Δ = +0.12, t=3.87, p < .001, d=0.11).

For expected course grade, the critical condition× time interactionwas significant, t (8,070)= 15.09, p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=0.48). Asreported in Table 1 and as illustrated in the lower left panel of Fig. 4,expected course grade increased significantly for students of the tea-chers in the ASIP condition from T1 to T4 (Δ = +6.8, t=18.13,p < .001, d = 0.49), while it remained unchanged for students of theteachers in the control condition (Δ = +0.1, t=0.43, p= .664,d=0.01).

For perceived skill development, the critical condition× time inter-action was significant, t (8,070)= 17.83, p < .001 (d IGPP-RAW=0.71).As reported in Table 1 and as illustrated in the lower right panel ofFig. 4, perceived skill development increased significantly for studentsof the teachers in the ASIP condition from T1 to T4 (Δ = +0.98,t=32.90, p < .001, d = 0 0.88), while it also increased significantly(though modestly) for students of the teachers in the control condition(Δ = +0.19, t=6.30, p < .001, d=0.17).

3.4. Test of the measurement model

The measurement model fit the data reasonably well, X2

(4272)= 8848.23, p < .001, RMSEA=0.034 (90% CI=0.033 to0.035), CFI=0.991, NNFI=0.990. Table 2 shows the descriptive sta-tistics and factor loadings for all 54 individual indicators included inthe measurement model, while Table 3 shows the intercorrelationsamong experimental condition, the 24 latent variables, and the 2 sta-tistical controls (gender, grade level).

3.5. Test of the hypothesized model

The hypothesized model fit the data reasonably well, X2

(4466)= 11,048.64, p < .001, RMSEA=0.039 (90% CI=0.038 to0.040), CFI=0.987, NNFI=0.986. The path diagram showing thestandardized estimate for each hypothesized path appears in Fig. 5. Forclarity, we do not show the T1 statistical controls in the figure, but wedo report each of these paths in the full statistical results below.

Early First Semester Effects. Early in the first (spring) semester,the experimental treatment produced all four hypothesized effects. Thatis, experimental condition significantly increased both (1) T2 need sa-tisfaction (B=0.19, SE B=0.01, β=0.22, t=16.53, p < .001),controlling for T1 need satisfaction (B=0.50, p < .001), grade level(B=0.00, p= .980), and gender (B=0.01, p= .564) and (2) T2 peer

task climate (B=0.21, SE B=0.01, β=0.25, t=18.51, p < .001),controlling for T1 peer task climate (B=0.49, p < .001), grade level(B=0.04, p= .018), and gender (B=0.00, p= .782).

Experimental condition significantly decreased both (3) T2 needfrustration (B=−0.10, SE B=0.01, β=−0.12, t=7.73, p < .001),controlling for T1 need frustration (B=0.28, p < .001), grade level(B=0.03, p= .069), and gender (B=0.08, p < .001) and (4) T2 peerego climate (B=−0.08, SE B=0.01, β=−0.09, t=5.65, p < .001),controlling for T1 peer ego climate (B=0.50, p < .001), grade level(B=−0.10, p < .001), and gender (B=0.09, p < .001).

Late First Semester Effects. Late in the first (spring) semester, 6 ofthe 8 hypothesized effects on changes in the T3 measures were sig-nificant.

For increases in T3 peer task climate, the experimentally-enabledgain in T2 need satisfaction was a significant predictor (B=0.08, SEB=0.03, β=0.08, t=2.26, p= .024), controlling for T2 peer taskclimate (B=0.58, p < .001), T1 peer task climate (B=0.12,p < .001), T1 need satisfaction (B=0.01, p= .683), grade level(B=0.02, p= .209), and gender (B=0.03, p= .100).

For increases in T3 prosocial behavior, the gain in T2 need satisfac-tion (B=0.11, SE B=0.04, β=0.11, t=3.07, p= .009) and the gainin T2 peer task climate (B=0.33, SE B=0.04, β=0.31, t=7.47,p < .001) were both individually significant predictors, controlling forT2 prosocial behavior (B=0.22, p < .001), T1 prosocial behavior(B=0.07, p= .015), T1 need satisfaction (B=−0.02, p= .621), T1peer task climate (B=0.05, p= .218), grade level (B=0.08,p < .001), and gender (B=0.02, p= .181).

For increases in T3 academic success, the gain in T2 need satisfaction(B=0.28, SE B=0.04, β=0.30, t=6.75, p < .001) and the gain inT2 peer task climate (B=0.16, SE B=0.04, β=0.16, t=4.10,p < .001) were both individually significant predictors, controlling forT2 academic success (B=0.24, p < .001), T1 academic success(B=0.12, p= .020), T1 need satisfaction (B=−0.01, p= .868), T1peer task climate (B=−0.03, p= .417), grade level (B=0.05,p= .009), and gender (B=−0.02, p= .445).

For declines in T3 peer ego climate, the experimentally-enabled de-cline in T2 need frustration was not a significant predictor (B=0.01,SE B=0.02, β=0.01, t=0.61, p= .541), controlling for T2 peer egoclimate (B=0.63, p < .001), T1 peer ego climate (B=0.09,p < .001), T1 need frustration (B=0.06, p= .005), grade level(B=−0.04, p= .023), and gender (B=−0.05, p= .001).

For declines in T3 antisocial behavior, the decline in T2 peer egoclimate was a significant predictor (B=0.24, SE B=0.03, β=0.24,t=8.01, p < .001) while the decline in T2 need frustration was not(B=0.00, SE B=0.02, β=0.00, t=0.18, p= .907), controlling forT2 antisocial behavior (B=0.36, p < .001), T1 antisocial behavior(B=0.09, p= .001), T1 need frustration (B=0.14, p < .001), T1peer ego climate (B=−0.04, p= .184), grade level (B=−0.05,p= .001), and gender (B=−0.02, p= .150).

In addition to testing these 8 hypothesized late-semester effects, wetested whether intervention-enabled changes in the peer climates mightaffect late-semester changes in students’ psychological need states. TheASIP-enabled increase in T2 peer task climate did longitudinally in-crease T3 need satisfaction (B=0.19, SE B=0.03, β=0.18, t=6.71,p < .001), controlling for T2 need satisfaction (B=0.47, p < .001),T1 need satisfaction (B=0.16, p < .001), T1 peer task climate(B=0.09, p= .013), grade level (B=0.03, p= .082), and gender(B=0.02, p= .099). Similarly, the ASIP-enabled decrease in T2 peerego climate did longitudinally decrease T3 need frustration (B=0.16,SE B=0.02, β=0.15, t=6.98, p < .001), controlling for T2 needfrustration (B=0.40, p < .001), T1 need frustration (B=0.18,p < .001), T1 peer ego climate (B=−0.09, p < .001), grade level(B=−0.02, p= .284), and gender (B=−0.01, p= .456).

Second Semester Effects. By year-end (end of the fall semester), 3of the 6 hypothesized effects on changes in the T4 measures were sig-nificant.

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

10

Table3

Intercorrelation

matrixam

ongexpe

rimen

talco

ndition,

the24

depe

nden

tmeasures,

andthe2statisticalco

ntrols

includ

edin

thetest

ofthestructural

mod

el.

Variable

1.2.

3.4.

5.6.

7.8.

9.10

.11

.12

.13

.14

.15

.16

.17

.18

.19

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

1.Ex

perimen

talCon

dition

Time1

2.NeedSa

tisfaction

-.07

-3.

NeedFrustration

.04

-.49

-4.

Peer

Task

Clim

ate

-.03

.70

-.48

-5.

Peer

EgoClim

ate

-.07

-.30

.53

-.51

-6.

Prosoc

ialBe

havior

.02

.63

-.49

.74

-.46

-7.

Antisoc

ialBe

havior

-.03

-.32

.64

-.49

.66

-.43

-8.

Acade

mic

Prog

ress

-.06

.84

-.50

.73

-.36

.83

-.37

-Time2

9.NeedSa

tisfaction

.33

.55

-.33

.39

-.23

.42

-.24

.52

-10

.NeedFrustration

-.23

-.26

.38

-.23

.31

-.25

.32

-.27

-.47

-11

.Pe

erTa

skClim

ate

.39

.38

-.28

.46

-.32

.45

-.31

.40

.79

-.46

-12

.Pe

erEg

oClim

ate

-.26

-.21

.38

-.36

.51

-.33

.43

-.24

-.41

.56

-.60

-13

.Prosoc

ialBe

havior

.32

.37

-.29

.42

-.31

.33

-.31

.42

.72

-.46

.84

-.55

-14

.Antisoc

ialBe

havior

-.20

-.21

.31

-.31

.44

-.30

.45

-.25

-.38

.65

-.51

.73

-.51

-15

.Acade

mic

Prog

ress

.27

.51

-.33

.42

-.23

.44

-.25

.60

.83

-.45

.74

-.40

.83

-.38

-Time3

16.

NeedSa

tisfaction

.35

.49

-.30

.37

-.23

.41

-.24

.50

.72

-.46

.64

-.38

.59

-.37

.66

-17

.NeedFrustration

-.27

-.25

.39

-.24

.28

-.27

.31

-.27

-.44

.58

-.44

.43

-.44

.47

-.44

-.56

-18

.Pe

erTa

skClim

ate

.38

.37

-.29

.41

-.30

.44

-.32

.43

.63

-.42

.71

-.55

.65

-.46

.60

.82

-.54

-19

.Pe

erEg

oClim

ate

-.30

-.25

32-.3

544

-.68

.35

-.25

-.44

.45

-.65

.68

-.51

59-.3

7-.5

3.63

-.66

-20

.Prosoc

ialBe

havior

.35

33-.2

9.37

-.28

42-.3

130

.58

-.42

.47

-.45

.65

-.44

.58

.76

-.55

.83

-.59

-21

.Antisoc

ialBe

havior

-.20

-.23

.37

-.31

.37

-.31

.43

-.26

-.37

.46

-.31

.57

-.48

.64

-.38

-.46

.70

-.55

.73

-.58

-22

.Acade

mic

Prog

ress

.36

.42

-.31

.35

-.24

.53

-.25

.54

.68

-.44

.61

-.37

.86

-.37

.73

.87

-.57

.80

-.53

.86

-.41

-Time4

23.

Prosoc

ialBe

havior

.42

.32

-.24

.34

-.25

.41

-.26

.36

.54

-.34

.60

-.41

.66

-.39

.58

.59

-.43

.65

-.51

67-.4

6.64

-24

.Antisoc

ialBe

havior

-.22

-.23

.32

-.32

.36

-.32

.39

-.23

-.38

.39

-.46

.50

-.53

.62

-.50

-.43

.44

-.51

.56

-.53

.62

-.48

-.63

-25

.Acade

mic

Prog

ress

.41

.40

-.28

.35

-.22

.40

-.25

.43

.63

-.39

.57

-.34

.63

-.35

.75

.69

-.46

.64

-.45

.63

-.41

.75

.64

-.59

-StatisticalCon

trols

26.

Gen

der

-.13

.13

.02

-.03

.18

-.05

.09

.11

.05

.11

.05

.21

-.04

.16

.06

.04

.07

.01

.11

.04

.10

.00

.02

.06

.04

-27

.Grade

Leve

l.26

.00

-.03

.13

-.19

.14

-.17

.00

.06

.04

.16

-.23

.17

-.16

-.06

-.07

.07

-.12

.19

-.17

.17

-.09

.19

.18

.11

-.19

-

N=

2739

.r's

≥0.04

,p<

.05;

r's≥

0.05

,p<

.01.

Forexpe

rimen

talco

ndition,

control=

0an

dexpe

rimen

tal=

1.Fo

rge

nder,fem

ale=

0an

dmale=

1.Fo

rgrad

eleve

l,middle=

0an

dhigh

=1.

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

11

For increases in T4 prosocial behavior, the increase in T3 peer taskclimate was a significant predictor (B=0.17, SE B=0.04, β=0.17,t=4.03, p < .001) while the increase in T3 need satisfaction was not(B=−0.01, SE B=0.04, β=0.00, t=0.20, p= .839), controlling forT3 prosocial behavior (B=0.28, p < .001), T2 prosocial behavior(B=−0.03, p= .403), T1 prosocial behavior (B=0.20, p < .001),T2 peer task climate (B=0.27, p < .001), T1 peer task climate (B= -0.18, p < .001), T2 need satisfaction (B=0.03, p= .491), T1 needsatisfaction (B=0.05, p= .154), grade level (B=0.09, p < .001),and gender (B=0.02, p= .141).

For increases in T4 academic progress, the increase T3 need sa-tisfaction was a significant predictor (B=0.14, SE B=0.05, β=0.15,t=2.78, p= .005) while the increase in T3 peer task climate was not(B=0.05, SE B=0.04, β=0.05, t=1.08, p= .279), controlling forT3 academic progress (B=0.30, p < .001), T2 academic progress(B=−0.06, p= .153), T1 academic progress (B=0.23, p < .001), T2peer task climate (B=0.13, p= .009), T1 peer task climate (B= -0.09,p= .061), T2 need satisfaction (B=0.18, p < .001), T1 need sa-tisfaction (B=−0.09, p= .116), grade level (B=0.06, p= .001), andgender (B=0.03, p= .128).

For decreases in T4 antisocial behavior, the decline in T3 peer egoclimate was a significant predictor (B=0.12, SE B=0.03, β=0.12,t=3.54, p < .001) while the decline in T3 need frustration was not(B=−0.04, SE B=0.02, β=−0.05, t=1.83, p= .067), controllingfor T3 antisocial behavior (B=0.36, p < .001), T2 antisocial behavior(B=0.14, p < .001), T1 antisocial behavior (B=0.05, p= .090), T2peer ego climate (B=0.10, p= .011), T1 peer ego climate (B=0.00,p= .896), T2 need frustration (B=0.00, p= .865), T1 need frustration(B=0.05, p= .032), grade level (B=−0.06, p < .001), and gender(B=−0.05, p= .003).

Mediation Analyses. As shown on the left side of Table 4, all threedirect effects of ASIP on the T3 outcomes (prosocial behavior, academicsuccess, and antisocial behavior) were statistically significant, as wereall three direct effects of ASIP on the same outcomes at T4 (p's <0.001). As shown on the upper right side of Table 4, there were sig-nificant indirect effects of ASIP on (1) T3 prosocial behavior via both T2need satisfaction (95% CI=0.008 to 0.034) and T2 peer task climate(0.048, 0.086); (2) T3 academic success via both T2 need satisfaction(0.036, 0.070) and T2 peer task climate (0.016, 0.046); and (3) T3antisocial behavior via T2 peer ego climate (0.011, 0.026) but not T2need frustration (−0.005, 0.004). As shown on the lower right side ofTable 4, there were significant indirect effects of ASIP on (1) T4 pro-social behavior via T3 peer task climate (0.013, 0.035) but not T3 need

satisfaction (−0.010, 0.008); (2) T4 academic success via T3 need sa-tisfaction (0.005, 0.031) but not T3 peer task climate (−0.005, 0.018);and (3) T4 antisocial behavior via T3 peer ego climate (0.002, 0.010)but not T3 need frustration (−0.012, 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study builds upon and extends a series of studies testing thecapacity of a teacher-focused autonomy-supportive intervention pro-gram (ASIP) to help teachers learn how to support their students'classroom motivation and adaptive functioning (Cheon et al., 2012,2016a, b; Reeve, Jang, Carrell, Barch, & Jeon, 2004). In the presentinvestigation, teachers who participated in the ASIP were not only ableto promote their students’ in-class need satisfaction and academicsuccess, they were further able to nurture a peer-to-peer classroomclimate that was perceived by students as increasingly more task-in-volving and increasing less ego-involving. This latter finding is uniqueto both the SDT literature and to empirical tests of ASIP benefits.

The ASIP-enabled more task-involving and less ego-involving peerclimate had two reliable and rather strong effects. The first was to booststudents' prosocial behavior and to diminish their antisocial behavior(see upper panels in Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 5, these effects were re-liable in that they occurred at both T3 and T4, and they were potent inthat they occurred even after statistically controlling for the T2 and T3changes in need satisfaction on T3 (βs= 0.31) and T4 (βs= 0.17)prosocial behavior and for the T2 and T3 changes in need frustration onT3 (βs= 0.24) and T4 (βs= 0.12) antisocial behavior. The second wasthat the increased T2 peer task-involving climate boosted T3 need sa-tisfaction (β=0.18) while the decreased T2 peer ego-involving climatediminished T3 need frustration (β=0.15). This means that the au-tonomy-supportive teachers in the present study enjoyed two pathwaysto contribute constructively to their students’ need states—one directway by being more autonomy-supportive and less controlling and oneindirect way by creating the relationship conditions that enable agreater peer task-involving climate and a lesser peer ego-involvingclimate to emerge in the classroom.

4.1. Peer task-involving classroom climate

Little research exists to explain how a supportive classroom climatedevelops and how such a classroom climate, once developed, advancesstudents' personal, social, and educational benefits (Smith, 2003). Oneprevious study did identify perceived autonomy support from one's

Table 4Mediation analyses to test the 12 indirect effects of ASIP on the T3 and T4 outcomes.

Direct Effects Indirect Effects Mediation Tests:

T3 Outcome Variable Estimate SE t p-value T2 Mediators Estimate SE t p-value 95% CILower Limit

95% CIUpper Limit

ASIP → T3 Prosocial Behavior .087 .008 11.19 .001 T2 Need Satisfaction .109 .035 3.07 .002 .008 .034T2 Peer Task Climate .326 .044 7.47 .001 .048 .086

ASIP → T3 Academic Success .085 .008 10.33 .001 T2 Need Satisfaction .277 .041 6.75 .002 .036 .070T2 Peer Task Climate .161 .039 4.10 .001 .016 .046

ASIP → T3 Antisocial Behavior .017 .004 4.14 .001 T2 Need Frustration -.003 .022 0.18 .907 -.005 .004T2 Peer Ego Climate .239 .030 8.01 .001 .011 .026

Direct Effects Indirect Effects

T4 Outcome Variable Estimate SE t p-value T2 Mediator Estimate SE t p-value 95% CILower Limit

95% CIUpper Limit

ASIP → T4 Prosocial Behavior .111 .009 12.51 .001 T3 Need Satisfaction -.008 .037 0.20 .839 -.010 .008T3 Peer Task Climate .170 .042 4.03 .001 .048 .086

ASIP → T4 Academic Success .106 .009 11.35 .001 T3 Need Satisfaction .140 .050 2.78 .005 .005 .031T3 Peer Task Climate .047 .043 1.08 .279 -.005 .018

ASIP → T4 Antisocial Behavior .017 .005 3.68 .001 T3 Need Frustration -.044 .024 1.83 .067 -.012 .001T3 Peer Ego Climate .115 .033 3.54 .001 .002 .010

S.H. Cheon, et al. Learning and Instruction 64 (2019) 101223

12

coach as an antecedent to a more task-involving peer-to-peer climate(Joesaar et al., 2012). Our investigation confirmed Joesaar et al.‘spioneering finding, and it extended it by showing that the facilitatingeffect of autonomy support on the quality of the peer-to-peer climatewas a causal one.

Autonomy support from a leader (i.e., coach, teacher) acts as a so-cial-contextual precursor to the establishment of a supportive (hightask-involving, low ego-involving) peer-to-peer climate. This occurs, webelieve, because autonomy-supportive teaching offers students an in-terpersonal tone of understanding and acceptance (see Fig. 1) that is notonly need-supportive but is prosocial as well (e.g., “I am here to helpyou.“). Autonomy-supportive teachers use this tone of understandingduring behavioral change suggestions (e.g., “Is making friends im-portant to you?“) and during conflict situations (e.g., “using respectfullanguage can be useful because …“). When a teacher shows under-standing and values students' perspective and input, then the teacheracts as a role model to show students ways to support each other and toavoid interpersonal rivalry and conflict. What is most notable about thefindings in the present study was the strong interdependency or cov-ariation among autonomy support, need satisfaction, peer task-invol-ving climate, and prosocial behavior on the one hand as well as thestrong interdependency among teacher control, need frustration, peerego-involving climate, and antisocial behavior on the other hand. In thefuture, it would be desirable to extend these findings after developingand validating new measures of peer-provided autonomy support (inaddition to peer task-involving climate) and after developing and va-lidating new measures of peer-provided interpersonal control (in ad-dition to peer ego-involving climate). Among other benefits, suchmeasures would enable new and informative comparisons of the re-lative effects of teacher vs. peer autonomy support (and control) onstudents’ prosocial and antisocial behavior.

Peer task-involving climate did not explain independent (i.e., ad-ditive) variance in students’ greater academic success (Fig. 5). Thus, theconclusion that emerged from the present findings was rather clear—-namely, that gains in peer task-involving climate led to longitudinalgains in prosocial behavior but not necessarily to greater academicsuccess, while gains in need satisfaction led to longitudinal gains inacademic success but not necessarily to greater prosocial behavior.

Not all hypothesized effects were significant. The need satisfactionand prosocial behavior measures were strongly positively correlated, aswere the need frustration and antisocial behavior measures (seeTable 3). But when both need satisfaction and peer task climate wereused together to predict prosocial behavior, peer task climate was aconstant predictor (significant at both T3 and T4) while need satisfac-tion was an inconsistent predictor (significant at T3, non-significant atT4). Similarly, when both need frustration and peer ego climate wereused together to predict antisocial behavior, peer ego climate was aconsistent predictor (significant at both T3 and T4) while need frus-tration was not (non-significant predictor at both T3 and T4). Theseresults contrast with Cheon et al. (2018) who found rather strongpredictive relations for need satisfaction on prosocial behavior and forneed frustration on antisocial behavior. Evidently, greater autonomy-supportive teaching produces two correlated effects (not just the oneeffect studied by Cheon et al., 2018)—namely, greater need satisfactionand greater peer task-involving climate, and it is the latter peer climateeffect that more catalyzes students' subsequent prosocial behavior. Si-milarly, lesser teacher control produces two correlated effects—namely,diminished need frustration and lesser peer ego-involving climate, andit is again the latter peer climate effect that more diminishes students’subsequent antisocial behavior.

4.2. Limitations, future research, and conclusion

Our conclusions are limited by one statistical and three methodo-logical decisions. As to the statistical limitation, small but significantbaseline (T1) mean differences emerged for 4 of the 10 dependent

measures. These baseline differences are important to the interpretationof the four associated condition× time interaction effects because, ineach case, students in the experimental condition had a bit more roomfor improvement in their T2, T3, and T4 scores than did students in thecontrol condition. The first methodological limitation was that all de-pendent measures included in the hypothesized model were assessedusing only students' self-reported data. Our study could be madestronger with the addition of objective ratings of peer climate andstudents’ prosocial-antisocial behavior. The second methodologicallimitation was that teachers randomly assigned into the no-interventioncontrol group did not participate in a structurally equivalent activeintervention experience. Our study could be made more methodologi-cally rigorous by having teachers in the control group complete anactive 3-part intervention experience (that was unrelated to motivatingstyle). The third methodological limitation was that we did not includea baseline score for rater-observed autonomy-supportive and control-ling teaching. The future inclusion of such baseline observations couldhelp overcome over-reliance on student-reported measures (i.e., alimitation which may cause problems with shared method variance)and confirm that teachers in the intervention condition did objectivelychange their in-class instructional behaviors.

Greater autonomy-supportive teaching nurtured a prosocial-boosting peer climate, while lesser controlling teaching nurtured anantisocial-diminishing peer climate. We suspect that future researchmay find that these same teacher-enabled changes in the peer climatemay affect additional classroom processes. For instance, changes in thepeer climate may have important implications for students' motivationto learn (as observed in the present study's effects on T3 need sa-tisfaction and T3 need frustration), and they may also have importantimplications for teachers' well-being and motivation to teach(Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Cuevas-Campos, & Lonsdale, 2014). Thefinding that teacher participation in an ASIP had a constructive effecton the peer-to-peer classroom climate seems to opens up a promisingnew area of research as to how teachers might additionally promotestudents' adaptive functioning and outcomes.

In conclusion, two new findings emerged. First, autonomy-suppor-tive teaching was a precursor to the establishment of a supportive peer-to-peer classroom climate (i.e., more task-involving, less ego-invol-ving). Second, once this more supportive and less conflictual peer cli-mate emerged, it enabled greater prosocial and lesser antisocial beha-vior.

Declarations of conflict of interests

None.

References

Adams, J. W., Snowling, M. J., Hennessy, S. M., & Kind, P. (1999). Problems of behavior,reading and arithmetic: Assessments of comorbidity using the Strengths andDifficulties Questionnaire. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 69, 571–585.

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., & Haerens, L. (2019). Correlates of students' inter-nalization and defiance of classroom rules: A self-determination theory perspective.British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 22–40.

Ames, C. (1992). Achievement goals and classroom motivational climate. In J. Meece, &D. Schunk (Eds.). Students' perceptions in the classroom (pp. 327–348). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.

Bartholomew, K., Ntoumanis, N., Cuevas-Campos, R., & Lonsdale, C. (2014). Job pressureand ill-health in physical education teachers: The mediating role of psychologicalneed thwarting. Teaching and Teacher Education, 37, 101–107.