Ladakh Diary on Blogger

-

Upload

arjun-l-sen -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Ladakh Diary on Blogger

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 1/45

THOUGHTS, RANTS AND A

TRAVELOGUEF O R T H O S E S L E E P L E S S , I N S O M N I A C N I G H T S W H E N Y O U ´ R E J U S T M O O C H I N G A R O U N D A N D Y O U

D O N ´ T M I N D C H E C K I N G O U T S O M E O N E E L S E ´ S T H O U G H T S A G A I N S T Y O U R O W N . . .

T U E S D A Y , J A N U A R Y 0 4 , 2 0 0 5

Ladakh, a travelogue

FAVOURITE QUOTES

Poetry is just the evidence

of life.

If your life is burning well,

poetry is just the ash.

- Leonard Cohen

NOTE

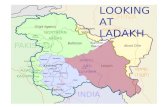

For those unfamiliar with the

location, Ladakh is a remote

high-altitude district north-

east of the main Himalaya

mountains and geologically a western extension of the Tibetan plateau. It

forms part of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. It remains disputed

territory between India and China but except for a north-eastern chunk of it,

called Aksai Chin, which was taken by the Chinese in 1962, the rest of it

remains in Indian control. To the west of Ladakh is Kashmir, to the north-

west is Baltistan, controlled by Pakistan since 1947, and further north-west

is Afghanistan.

Chumathang-Nyoma Road, Eastern Ladakh, August 1977

I was twenty-one years old and on board a jeep moving across the high

desert of eastern Ladakh after leaving the silent, sun-blinded military

outpost of Nyoma. All day the four-wheel drive vehicle laboured across a

A B O U T M E

CERRONEVADO

VIEW MY COMPLETE

PROFILE

P R E V I O U S P O S T S

Next Blog»[email protected] BLOG FLAG BLOG FOLLOW BLOG

Page 1 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 2/45

seemingly trackless waste, deadly and pure. At the end of the day we arrived

at another outpost, a huddle of prefabricated buildings in a dead landscape

strewn with boulders as big as houses.

I sat alone beside a pebble-strewn stream, under a sky turned flesh and

midnight blue, spangled with stars like mica spots. Mountains bulked in the

distance, a torn and stretched black curtain against the luminous sky. I felt

tensely alive in a place that seemed so vast and so dead, not a bird, animal or

insect in sight. Yet I felt through the warmth of my body a strange oneness

with the cold, dead stone, the yielding, mirror-like water, the dark, limpid,

canvas of the sky, the brooding stillness of dark night clouds, the powdery

smell of dust and sand.

I sat in the twilight world between the living and the dead, the awakened and

the sleeping, the dark and the dawn, till all distinctions and separations and

discrete understanding were banished from my mind. I knew then that I

could never pass beyond the earth and the immense embrace of its spiritual

gravity. When I awoke from this emotional and perceptual fever, the stars

were just fading above the cold, cold hills and a jackrabbit stood a few feet

away, all tremble-nose and bright eyes. It was as still as a stone till it saw

me staring at it and fled.

It is one of the few occasions that I seem to recall I meditated. Not

deliberately, but just naturally. It wasn´t day-dreaming but a much more

alert and intense state. I felt extraordinarily alive. It was one of those rare

occasions when I could cope with not doing something specific, even just

reading a book, without getting bored. I felt that life was best when one felt

just like this. I discovered, for a few fleeting minutes, a genuine sense of

perfection. Of beauty, of sensation, of tension, of peace of a state of

awareness.

Arrival in Leh, October 1996.

In October 1996 I had an opportunity once again to visit the high plateau of

eastern Ladakh. I arrived in Leh by air with two friends . Leh stood at about11,500 feet above sea level and the first night, like many new arrivals to

fairly high altitude, I slept badly. In the morning I went to the cold, bare,

concrete bathroom and looked out of the window to see dawn over the

mountains. It was a stunning view. The Ladakh Range rumbled across my

field of vision, brown fore-ranges flanked behind by snow peaks. Twenty-

one thousand-foot Stok Kangri raised her white-mantled head among many

other tall peaks like a queen surrounded by admiring courtiers. To the left, a

spur of the Ladakh Range darted towards us, like a rusty blade. In a sky of

luminous, soft blue, edged with flush-pink, a group of cumulous clouds

boiled dramatically dark. It was raining over that spur but the rain appeared

Page 2 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 3/45

as downward smudges of black and grey, not anything you could see

moving, like the effect of an artist's hand deliberately smudging paint on

canvas to convey this impression, or the view caught in a still

photographer's lens: vigorous, natural movement, frozen in time. It was

worth more than a night's discomfort to experience this strange and

wonderful view, full of improbably colours, with at least two different

weather conditions visible in the same field of vision. The other part of the

view was huge, serene, bright, uncluttered.

A few days before leaving for the eastern sector, we decided to spend a day

in one of the villages outside the Leh valley. We were fortunate to have the

loan of a military jeep and we asked the driver to head towards the

monasteries of Shey and Thikse (Khrig-rtse) upriver. The sunlight was

wonderful, the sky clear with a few fluffy clouds to give definition.

Fifteen kilometres out of Leh, along a beautiful winding road fringed by

golden poplars and willows and bubbling streams feeding the Indus, we

arrived at Shey. We stopped beyond the monastery by the side of a stone

wall separating a bit of marshland from the village school. Shey was an

oasis of peace, silence, space and the most intense colour and beauty. Leh

had its attractions but to a jaded mood its bustle could seem tawdry and the

noise and hubbub could get wearisome. All this seemed very remote now. In

Shey, sunlight glittered on marshy water, drenching everything in liquid

gold. On looking up I saw an old ruined fort east of the monastery sprawled

along the crest of a steep, boulder-strewn hill. The pale, sand-coloured stone

of the fortress glowed against the gritty texture of the hillside from which itthrust upwards like a fist in the sky which was a deep blue, so deep that if I

kept looking at it I felt as though I was levitating gently upwards and

disappearing into space. The outline of the fortress walls and the roof of the

buildings against the sky was sharp and abrupt between the intense swatches

of colour, making the forms appear as though drawn flat on a painter's blue

canvas. Beyond the road : golden willows and poplars, brilliant green

cultivated fields flashing with nuggets of water, a short-horned dzo quiet

beside a stone wall, her coat the colour of dark, rolling clay. Beyond: the

folds of the Ladakh Range, triumphant, like a rippling flag unfurled, snow

shining on the higher peaks.

We walked along the stone wall of the schoolyard swamped in heavy,

sweet,sun-laden silence. It was a long wall. Half a mile further, scores of

white, scarred chorten (reliquary shrines) stood like a troop of silent

sentinels on a low, uneven escarpment beyond a plantation of gold-leaved

fruit trees. I walked among the old monuments feeling oddly watched by

these impassive structures, overpowering in their numbers in such a humble

village. Centuries of human prayer seemed to emanate from the historic

relics, the way thoughts and feelings seem to whisper from tombstones in a

graveyard. The chorten stood in the sunshine bearing a faintly reproving air,

Page 3 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 4/45

like retired guardians of a culture nearly forgotten, almost like ruins

themselves. This effect was enhanced by the loudness of the silence and the

fact that as I had chosen to walk on ahead while and were meticulously

contemplating and taking pictures, I was now utterly alone. My mood

picked up a strong contrast between the joyous optimism of the sunshine

and intense colour of everything around and the brooding quality of the

chortens. They looked like frozen figures about to speak but held back by a

spell. This emotional and visual trick imparted an uneasy and slightly

exciting quality to the peaceful surroundings. I picked my way among the

monuments, climbed over a low rubble wall and wandered among willows

and fruit-trees. Blue and gold were the dominant colours, blue of sky, gold-

orange and gold-red of the trees, and shivering white their elegant,

corrugated bark. The tall, blonde poplars and the red-headed willows

seemed as though they had been designed thus not for any practical purpose,

but simply to please, as though nature in Ladakh abhorred any clumsiness of

design. Every rough-textured stone and pebble, every green blade on the

earth, sprung up to meet the eye in an exuberance of form and texture and

colour. This was a place where the detail competed with the big picture and

the eye, unable to focus, to prioritise, and yet taking everything in, was

overwhelmed. Here among the fruit trees of Shey, light was love, beauty,

peace. The easy phrases, so glib-sounding and easily dismissed in more

prosaic surroundings, here came to mind with a vibrant sense of reality. The

cleanliness of the paths and yet their absence of prim, regulated boundaries

and smoothness of surfaces, the unfinished yet adequate apearance of

dwellings in traditional style, all strongly suggested a union of the forces of

nature and the hand of man. Little in the environment here appeared to bewasted or abused, and if there was some such abuse, it was not much in

evidence.

I sat on a piece of broken stone wall on my own, looking across the grove of

fruit trees to a group of children and their teachers chanting lessons in

Ladakhi in the dusty courtyard, their voices soothing and clear-toned in the

sharp, dry, carrying air, impelling one to listen. The beauty and

reasonableness of life here, seemingly far away from the roaring misery of

the world, was like a cool, damp cloth on a feverish brow, putting a

sleepless man into a kind of restful, waking oblivion. Here, in Shey, I began

to see some merit in the much maligned idea of escape. I thought I

understood something of the idea that bliss is not some form of oblivion or

unconsciousness, but rather, an intense consciousness amid an absence of

pain and a near surfeit of beauty, perhaps closer to the Western paradise

than the Indian nirvana, to some minds. If only for a few minutes, I peered

through the gateway of my eyes and my other senses into the garden where

the flower always blooms on the branch and the fruit is always sweet. Then I

turned my head and saw the jeep that brought us to Shey, and the metalled

road linking Leh with the villages upriver, and the trucks lumbering

occasionally in both directions, and I was reminded that peace in Shey

Page 4 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 5/45

depended on the village people living their frugal but adequate lives in

relative isolation and using old-fashioned, spare, but ecologically sound

technology. This peace was probably on its way out already, despite

appearances to the contrary.

The Tibetan Girl

I had very little meaningful contact with Tibetans in Leh. They occupy a

slightly tense place between Ladakhis, on the one hand, both Buddhist and

Muslim, and the Kashmiri Muslims of Srinagar and the Indians of the plains

on the other. I have always been interested in them since I was a little boy. I

used to go on holiday to my grandfather´s house in Kurseong in the

Darjeeling District. He had a Tibetan housekeeper and my younger brother

and I got friendly with his two sons. I had no understanding whatsoever

about political issues then (I was about twelve and not very politically

aware) but I knew that Tibetans and Chinese didn´t get along. I didn´t know

that China forcibly occupied Tibet in 1950, and slaughtered one million

people out of a total population of six million, and Tibet remains the

longest-running genocide which the world has chosen to turn a blind eye to

as everyone is so anxious for trade with big and powerful China. One day I

fished out a Chinese stamp out of stamp collection (yes, a lot of boys

collected stamps when I was young!) and showed it to the elder son,

Kesang. His face turned red and he spat on the ground. Then he wrenched

the stamp out of my hand and stamped his boot on it. My education aout

what happened to the Tibetans began on that day. It was 1968.

The only chance I got to meet Tibetans in Ladakh on my last visit in 1996

was towards the end of the trip and there was no time to build on it. I used to

walk occasionally from our government accommodation two kilometres out

of town to a Tibetan restaurant in the centre of Leh. It was a typically small,

dark, slightly secretive little place, with rough wooden chairs and tables, and

Tibetan posters and calendars on the walls. An open courtyard separated the

eating area from the kitchen where Tibetan, Indian and European-style food

was cooked. Apart from excellent Tibetan and Chinese dishes, they did a

great line in deep-fried potato chips, thick and steamy like English fish-and-

chips. Whenever we went there we always found Westerners. It was the sort

of place where it was impossible not to overhear other people's

conversations and, inevitably, to get drawn into some of them unless one

maintained a resolute social distance from one's fellow diners. Plenty of

locals used the place as well. Some of the posters were political, dedicated

to supporting the Dalai Lama and the cause of Tibetan freedom. It was run

by a young couple, perhaps in their late twenties or early thirties. The young

man wore glasses and had a faintly academic air, incongruous with his

chef's apron. The woman wore jeans and tee-shirt and was beautiful in a

fragile sort of way with long, shoulder-length hair, a delicate heart-shaped

face and large eyes.

Page 5 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 6/45

Initially, there seemed to be no possibility of interaction beyond ordering

our food and being served. The man never hung around the cashier's table

much; he was usually away in the kitchen and the young woman did most of

the serving and interacting with the customers. The young woman's manner

was brisk and to the point and she did not hang about much while we were

there, or indeed, any other outsiders including Westerners. I had a distinct

impression that she and her young man would rather be doing something

else if they had the opportunity, perhaps something making use of higher

education and advanced skills, something professional perhaps. Other

people in the restaurant tended to be rather silent or spoke in low voices,

enhancing the slightly conspiratorial air I had initially noticed when we first

visited the restaurant. We also started by speaking in whispers but after a

couple of visits this furtive approach seemed to lessen the enjoyment of the

good food so we became rather more expansive.

Our conversations could be easily overheard by everyone else in the small

restaurant. Some people listened in and occasionally someone would join in

though generally, the Westerners seemed to be very cautious about

interacting with me and my two Indian companions. There definitely

seemed to be a barrier between the Western visitors and ourselves. I suppose

we must have appeared like the sort of city-bred Indian tourists who just

didn´t "understand and appreciate" Ladakh - whereas they, of course, did .

One or two attempts I made to draw Westerners into conversations we were

having met with stiff or embarrassed responses.

All the time, the young Tibetan woman proprietor stood about listening,

either behind her cashier's desk or, more often, at the doorway to the

courtyard, with a rough cloth curtain partly drawn between us . She had

been watching us from the kitchen corner for several days. On the

penultimate occasion that we visited her restaurant, a few days before

leaving Leh, she suddenly approached our table and handed us a leaflet

asking for charitable donations to help Tibetan refugees in Ladakh improve

their conditions and to start self-help projects. Between the three of us we

gave several hundred rupees, a good cash donation within our very limited

funds at the tail end of our trip. I also asked her if she knew somewhere in

Leh where I could get Tibetan freedom posters and stickers as I would use

them in England. With her advice, I eventually managed to track down a

small shop in the Leh bazaar and obtained some of these stickers.

The very last time we visited the restaurant, we had a good meal, left a

generous tip and we were about to leave. I was about to go, gathering up my

shoulder bag and camera, when the young woman came upto my table and

hesitantly started a conversation. She wanted to know where we were from,

what we had done and enjoyed during our trip to Ladakh etc. etc. I started to

tell her a little bit about what we were doing, that we were taking pictures, I

Page 6 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 7/45

was hoping to keep up a diary of our trip, that we had enjoyed her food. I

started asking her about the life of Tibetan people in Ladakh and wanted to

know what she thought but knew I no longer had the time to explore this

properly. Her replies were cautious, hesitant, she was obviously not sure

whether speaking freely was a good idea. I said that unfortunately I should

have asked her earlier, tried to establish some communication, that it was

my fault but now we had no time left and had to leave Ladakh. Reluctantly,

we shook hands and with mutual expressions of good will I left. Her face

had a look of resignation and slight disappointment. I think she had a great

deal she wanted to say, and that it would be easier with a stranger like me

who would go away and not trouble her again, than with people round about

whom she knew. Perhaps she felt that a stranger like me, and Indian

perhaps, but from outside India, would be able to understand some things

that other people round her - except for her husband - would not. These

things I sensed, they were not articulated verbally, they came across in

expression, gesture, body language. As I walked away I saw her standing at

the entrance of the restaurant, down a small alley, looking intently in my

direction. Once again I felt that I had failed to conquer my diffidence and

hesitation, that I should have found a way to turn back and pursue the

communication, to learn about something that I had the opportunity to learn,

but I did not.

Tendzin, the shepherd-nomad and I

Idealistic Western visitors have their biases andenthusiasms which also romanticise and, in doing so,

patronise. To them, Ladakhis are sophisticated in spiritual

gifts but simple in material things and technology. Within

this overlap, however, there is room for re-evaluation and

a better mutual appreciation on both sides. To Indians,

however, determinedly bent on a modernisation course,

Ladakhis are just plain backward. I have never heard an

Indian say that India has something to learn from Ladakh,

whereas plenty of Westerners are saying that they could

learn something. With Westerners, and despite all thecaveats and resentments I have heard expressed from

Ladakhis, I think the Ladakhis are in some respects freer

to be themselves.

Tendzin, a young farmer I met in Leh, told me about his

life in the village, his deep feeling for the land, the

spiritual joy of hard work in the fields, the uncertainties

and dangers of a life at the mercy of the elements, his

close relationship with his grandfather whom he admired

Page 7 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 8/45

and revered, who was now old and wanted to keep

Tendzin at home. He told me of his desire to go away,

back into India where he had got his college education, to

become a film director and express his feelings and

thoughts for his land and people in an age of rapid change.

He also spoke of his difficult relationship with his father

who he respected but whose consevative views frustratedhim.

My background was very different, city-bred, food

appearing not out of the earth but as if by magic in

markets and thence to the kitchen table, my life lived in

various parts of the world, my sense of self a bricolage

cobbled together from various places, a coat of many

colours. His sense of self was as rooted as the earth that

nurtured him, with him from the day he was born. Now he

looked outside as well as in. I do not think I had any clear

ideas about myself until I was over thirty. I had my own

kind of growth from the outside back in. It greatly moved

me that though we had different things to say, neither

needed to be something other than what we already were,

neither sought some other state of being than what was

already within the individual concerned. There was a kind

of basic acceptance of what the other person was, different

in many respects but with points of mutual comprehension

in others. and joined the conversation and contributedgreatly to expanding some of the things Tendzin and I had

touched on.

The conversation carried on throughout the day. It was

interrupted by a dreamy, vividly remembered walk over a

hillside, covered in marshy clumps of grass to the edge of

a cold, powerful stream. and lagged behind again, perhaps

looking for things to photograph or perhaps even sensing

that I was trying to get through some things with Tendzin

on his own. Late afternoon sunlight glowed on the yellow

grass and the glistening marshy water. Looking down from

the stream, I saw and heard the buzzing fields, the hillside,

the lowing yaks, the occasional tinkling bells of goats.

Among them, the dazzling white of the farmhouses, two-

storied, and with the Tibetan-style wooden-shuttered

windows and painted borders angled pyramidically

inwards, so characteristic of the tradional style. Here, in

this village, it was kept up without any apparent self-

consciousness. The buildings all looked quite old. Beyond,the half-hidden, clustered silhouettes of other villages,

Page 8 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 9/45

Karzu, Samkar, Yuthung, Leh out of sight behind the fold

of a huge hill. Willow and poplars waved streaming

blonde heads in the sunshine. Beyond them, the far valley

across from the hidden Indus, violet, purple, sienna and

soft blue mountains, the highest peaks of the Ladakh

Range topped with snow. Above, the sky, a dreamy, easy,

unquestioning blue, like a summer sky in England.Tendzin decided to take a bath in the stream. I contented

myself with rolling up my trousers to above knee length

and plunging in. The stream was as cold as it looked and

after stepping out, my feet and lower legs were flushed

red. I was glad I had not considered a full dip. Tendzin

seemed to relish the dip and rubbed himself down

vigorously while a cold wind coming from the hills to the

north began whistling down. Here, on the hill by the

stream, Tendzin was really very much a countryman, a

local farmer by conditioning, and the signs of his

acclimatisation to the easier and more sophisticated life of

the Indian city were few, though important : his Delhi

University accent when he spoke in English, his excellent

grasp of Hindi, and his habit of smoking tobacco and

grass. He gave an impression of having acquired from

Indian city life only what he found interesting and useful

after due consideration.

We sat on tussocks of nearly dry grass among lumpy whiteboulders and spread out our lunch - parathas, curried

vegetables, processed cheese, beer. Above, the sky began

to fill up with dark clouds rumbling in over the hard, bare

brown hills to the north. suddenly noticed the figure of a

man coming in from the hills upstream. We turned to look

and saw a tiny, indistinct figure, scarcely more than a dot.

The figure was approaching with great speed and within a

couple of minutes, became distinguishable as a man,

moving over the rough, steep, boulders and pebble-strewn

hillside in a fast, rolling gait. Within five or six minutes

we could see that he was wearing the dark purple gonchha

(woollen gown) tied with a cloth cummerbund at the

waist, traditional in these parts. By the time he was within

twenty yards of us, more interesting details became

apparent. He wore a Mongolian fur hat, the ear flaps taken

up and fastened to the headpiece in the characteristic

fashion of the nomadic clans. He wore knee-length

rawhide boots, reinforced with leather thongs and chased

with worked silver along the flanks. In one hand, hecarried some sort of long, whip-like object, looped into a

Page 9 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 10/45

double-length. His lined, leathery face suggested an age of

sixty but he was probably not much more than forty-five.

He had high cheekbones and a wispy beard and

moustaches. His eyes, elongated, were hidden almost

completely in their epicanthic folds as his face creased into

a friendly, but slightly wary, smile. There was a strange

minutes' silence when the nomad approached and stoodbefore us and we sat or half stood facing him. It was an

infrequent, but characteristic type of moment we

encountered occasionally in Ladakh, when we met very

simple people who had few of the trappings of modern life

about them, and faced us without any attempt to pose, to

present themselves in a certain way. The effect is

distinctive and a little startling and I feel certain that it has

something in common with encounters with simple,

traditional people elsewhere in the world. There is a lack

of pretension or artifice about them, of either pride or

humility, just a way of confronting you with themselves,

looking you straight in the eye, neither challenging nor

calculating. There seems to be no hidden agenda, no

impression that one is needed and being worked on. To us

city people it created a feeling of mystery, magic almost,

and of having encountered somebody who knows how to

be what they are, whereas we are always trying to make

ourselves be what we are really not because the exigencies

of sophisticated life require it at all times; we have beenrole-playing false personas for so long that we have

forgotten how to be ourselves.

No one spoke, there was a slight tension in the air, but it

was not an unfriendly tension, more, a kind of

anticipation. The wind stirred. Time stood still for the

minute or so in which all this seemed to take place, like

slow-motion photography, with all the details clear and

measured. I could hear the gurgle of the stream. Sunlight

glinted off the metal surfaces of our eating utensils.

Instinctively, I grasped a boiled egg and held it out to the

nomad in a gesture of welcome and to join us and eat. The

nomad looked at me slowly, searchingly, then at Tendzin,

an expression of enquiry on his face. There was no verbal

reply but Tendzin made a slight gesture with his head. The

nomad took the egg in a large, calloused hand, paused

briefly and smiled, then stood back straight and carefully,

almost reverently, placed it in the folds of his gonchha. He

refused to take any other food but and , through Tendzin,persuaded the nomad to have his photograph taken. He

Page 10 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 11/45

acquiesced and stood straight and relaxed. I could not

resist the urge myself, and took a couple of shots. We

wanted to know what the whip-like object was. Through

Tendzin as an interpreter, we asked him. The nomad

chuckled and offered to give us a demonstration. He took a

stone about the size of a man's palm, and placed it in the

loop of the sling - for that is what it turned out to be - andthen pointed to a pinkish boulder among a lot of white and

gray boulders about fifty or sixty yards away. It looked, at

this distance, not much bigger than a large stone itself. He

then whipped the swing round in a hard, very fast motion

and a moment later we saw a puff of rock powder coming

off the pink boulder followed by a tremendous crack like a

rifle shot. The bang reverberated round the hills and in its

wake, a small pile of little stones came slithering down a

scree slope. There was a moment's silence. It was clear

that the sling may have looked like a primitive weapon,

but when used with force and accuracy of this kind, it was

as deadly as a firearm. The nomad laughed heartily and

looped it round again and stuffed the end into his

cummerbund, at the hip. He explained to us through

Tendzin that he was a shepherd and used the sling to deter

wolves. After exchanging a few more words with Tendzin,

he smiled round at all of us and shook our hands warmly

and then moved off, back up the rough, brown hills, in that

fast, rolling motion that within a few minutes, renderedhim once more a little dot in the distance.

A few minutes later we packed up our lunch and started

making our way back to the village. Around us, the red-

brown hills loomed, hard against the sky. Their pinnacles

must have been two to three thousand feet above us and

rose so steeply from the narrow valley that to see their tops

one had to look almost vertically up. The dark clouds were

mingled with pale grey, pinkish and pearly white cumulus.

They were moving swiftly and golden light wallowed

through them. Choughs flitted among the clouds, little,

dark, fast-moving birds, indistinct and slightly batlike at

that distance. , whose eyes were the keenest, pointed out to

me a line of sheep walking the crest of one of the hills. I

craned upwards and screwed up my eyes to see and for a

few moments, saw nothing. Then suddenly the pattern

emerged: I must have detected the movement first. A line

of tiny white specks were negotiating the crest of the

mountain. The crest of the hill was a long row of hundredsof small, needle points, like crocodile teeth. Clouds moved

Page 11 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 12/45

swiftly, seemingly just above the crest of the hill, like a

patchwork quilt just unfurled and about to come down. I

stared at this giddy vision and I could feel my sense of

balance going. The idea of any animal actually standing or

walking up there, looking down thousands of feet of

nearly sheer drop, head in the clouds, made me feel

slightly sick. Despite my attraction to mountains I havenever had a head for heights. I dismissed the thought of

falling by telling myself that they were, after all, sheep,

who could and would do, without much trepidation, what a

man would not. Then I remembered that behind the sheep

must be the shepherd. I asked Tendzin about it. He grinned

and confirmed that the sheep belonged to the nomad we

had just met and he was making for most of the way up to

the top. After another hour he would lead his sheep down

to an evening bivouac somewhere in the hills.

When we arrived back in the village, Tendzin led us to a

two-storied farmhouse, nestled among flame-leaved trees.

It was a traditional-looking structure of stone and plaster

with walls a foot thick. A narrow, steep little staircase led

up to the living quarters on the first floor. This consisted

of a large, rectangular, simply furnished room which

served as kitchen and dining room. Small windows of

smeared glass were recessed deeply into the thick walls on

which copper kettles and pots gleamed. A Ladakhi one-stringed guitar, about 45 cm. long, carved and painted in

wood, hung on one wall. A woman in her late twenties or

early thirties sat handling the kitchen fire. She had the still,

composed manner of the village people which made her

such an excellent subject for a photographer. With a little

persuasion from Tendzin she agreed to be photographed.

She was composed and just herself, neither camera-shy

nor forward. I marvelled at her simple dignity, something I

certainly could not achieve in front of a camera. In a way,

these people just took their own pictures.

While the picture-taking session was going on, I wandered

out of the room. Another small set of stairs led up to the

roof. A few square yards of open courtyard was backed by

another room, standing as a structure on its own on the top

of the building. I did not enter this room but stood in the

courtyard and looked around, breathing in the cold, clean

air. It was slightly moisture-laden, partly from the fast-

moving little stream rushing through the village andpassing very close to the house, and partly from the storm

Page 12 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 13/45

clouds moving over and away from the village, in the

direction of the Ladakh Range beyond the far side of the

Indus. Bales of straw for animal feed were piled in neat

bundles, tied together with grass stems. The hills were

darkening a little to soft browns, blues and purples. In a

few minutes, the others all came up to the roof and we

went inside the free-standing room. It turned out to be verysimple, little more than a cell about eight foot by ten foot.

One small panelled window looked out over the

mountains, the fragmented view scraping past behind

stands of willows. Some thick woollen blankets were

folded out at one end of the room in a U-shape and at the

other end, a simple wooden table and a couple of wooden

chairs. We sat around together on the blankets and the

woman brought us supper, a simple but hearty meal of

rice, parathas and vegetables. It was a much better meal

than anything we had in Leh and we all ate ravenously.

After dinner a joint was passed around. I engaged Tendzin

in conversation. sat back, relaxed, observing. A kind of

happy intensity seemed to invade us all, in the peace of

that room, high up in the hills.

The walk back to Leh turned into a kind of odd fiasco. It

was nearly seven kilometres back to Leh, plus an extra two

kilometres to the government building in which we werestaying. By the time we left Gyamsa it was nearly dark.

The sun was declining redly behind mountains which were

now black backdrops to the hushed valley. The birds had

stopped twittering and the yaks and goats were silent in

their byres. We walked back along the broad, stony jeep

track out of Gyamsa, towards Leh in a loop via Yuthung

and some of the other villages. As it grew darker, our

ability to see the track worsened. I had a weak left ankle,

injured a year ago in an accident and I tended to favour it a

little. This also made me cautious about my footing and I

started worrying about turning my ankle again on the large

and often sharp stones. It was by now quite cold and the

wind was beginning to bite. and maintained a comfortable

pace while I tried to keep up with Tendzin, partly in an

effort to keep him company but more out of a growing

anxiety to get the walk over with. He remained a little

ahead of me maintaining a steady, easy gait over the stony

path. He moved without looking down at the ground at all,

his feet in sneakers bouncing lightly over the uneven,potentially dangerous surface as though he were on level

Page 13 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 14/45

ground, while I planted my feet rather awkwardly and

heavily and frequently stumbled. In that dim light, he

seemed almost to levitate slightly, so unencumbered was

his progress. As for me, I just wanted to be back in town

as fast as possible. I was so engrossed in trying to walk

without stumbling that I had to stop occasionally to take in

the overpowering beauty of the whole experience, the skysilky blue-black but rent with pearly snatches of moonlight

from gaps in the cloud cover like ichor-coloured wounds.

Stars in the gaps glimmered faintly like scatterings of

silver dust. The hills hulked all around, a dark army of

sleeping giants, massive shoulders hunched against a light

sprinkling of rain.

Tendzin must have noticed that in the gathering darkness

we were all having increasing difficulty in negotiating the

path and our pace was slowing down so he suggested

taking a short cut. He meant well but the results were

actually worse. The short cut involved negotiating ditches,

five foot high stone walls at two points, streams with sharp

and stony declines at various places, and walking along

narrow alleys alongside houses guarded by aggressive

dogs, which, for all we knew, were likely to be untethered

by this time. For me, the darkness was the problem, I

could not see what I was doing. The others seemed to

manage better, and Tendzin simply floated overeverything as though the obstacles were not there, like a

phantom. Fortunately I had a pocket torch handy. A little

after we had got past Yuthung village, we hit the main

metalled road. A jeep slowed down, dazzling us in its

powerful headlights. Two young locals, respectably

dressed, gave us a lift all the way to where we were

staying, even though it was well off their own route. This

kindness, we thought, had a lot to do with the fact that

Tendzin was with us as well as because they were

Ladakhis. Generally we found that in Leh, people in

vehicles were not obliging about giving us lifts. This is not

because they fear muggers, as in Western countries.

Cadging lifts was still an innocent activity, as it used to be

in Europe in the sixties. However, most vehicles in Ladakh

are driven mainly by public servants, usually Indian, or

Kashmiri, who usually come from traditionalist

backgrounds and who do not like the urban, westernised

classes. Ladakhis, as yet, do not seem to have the same

level of difficulty with westernised Indians, although thismay not be far off coming.

Page 14 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 15/45

The last frontier: Ladakh-Tibet border, Nyoma to Kyari

and Pangong Lake, September 1996

The morning we left for the frontier on the east of Ladakh

with Chinese-occupied Tibet, the sun was shining in acharacteristic hard blue sky and the golden poplars (yarpa)

and willows (sol-'cang) splashed the twists and turns of the

broad Indus valley near Shey and Thikse in a frieze of

crumbling gold. Mr K. of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police

was our host and driver. His subordinate officer, Sonam,

sat impassively, sandwiched tightly between two of us in

the back seat. With our sacks and photographic equipment

and a party of five, there was no spare room in the four-

wheel drive Maruti Gypsy. This Indian-made vehicle

designed with Japanese collaboration only had a 1000 cc

engine, the sort that in Britain is installed in small cars

used for tootling around towns to bring home children and

shopping. The vehicle had a fuel consumption of about 8

kilometres per litre over hard terrain. The first day's

driving was to prove the longest and hardest, subjecting

the vehicle to a punishing regime as Mr K. proudly

demonstrated his cross-country driving skills on what must

have been one of the tougher jeep trails in Asia. Mr K.

planned to reach Chushul Post, on the eastern edge of Indian-held territory, a few kilometres from the shores of

Pang-gong, the largest (140-kilometres long) salt lake in

the Western Tibetan plateau, about a quarter of which

remains in Indian-held Ladakh, the rest under the Chinese

military occupation. None of us had any experience of

terrain driving. The tour convinced us that any notions we

may have entertained at the outset of driving ourselves

over this territory were unrealistic - we would probably

have broken the vehicle's axle within twenty miles of

leaving the dirt trails and moving over country. Thedriver's skills invited awe ; so did the hardiness of the

vehicle. Comfort and interior space were certainly not

uppermost in the minds of the engineers who designed it

but if stamina was, their efforts were not misplaced. The

initial 30 kilometres or so to Karu were easy. We bowled

along merrily on a broad, single carriage road, passing the

majestic tumuli of Shey and Thikse monasteries and a

number of small villages till we turned sharply left at a

junction after Karu. The road began to climb steeply. After

two hours the mountains were now completely bare rock,

Page 15 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 16/45

rolling and tumbling down in great sweeps of burnt umber,

ochre and rust-red scree which plunged thousands of feet

down the slopes.

We were crossing the Ladakh Range from south to north.

All the passes in this range were high ; the highest peak,

Stok Kangri, stood at over 23,000 feet. The Khardung Lapass at 18,380 feet, leading into the Nubra Valley north of

Leh, still claims the world's highest metalled road,

although there may be roads in Tibet climbing higher, for

all anyone knows. The Chang La pass on the road to Pang-

gong Lake, which we were about to tackle, is estimated to

reach 17,350 feet at the top. Mr K. believed that some of

these altitudes were exaggerated a little but as they remain

the officially published figures, it is not my place to

dispute them. At about 16,500 feet above sea level we

stopped for a breather, fighting nausea from the effects of

drinking alcohol at Mr K.'s house the previous night.

Patches of ice glittered on the sun-beaten, treeless slopes

around us. was ecstatic : he had never seen snow or ice

before, outside the cold compartment of a refrigerator or

the television screen. Smoking a cigarette was not

recommended but and I smoked one anyway. Up here, life

seemed so fragile anyway that to smoke or not seemed a

side issue. As we struggled back to the Gypsy, a huge

pick-up truck loaded with road workers grunted painfullyaround the steep corner of the road behind us and panted

slowly away up towards the top of the pass. The ragged-

looking road workers with both Indian and Ladakhi

features, stared back at us with the automatic, tired

curiosity they all have in these remote areas. I thought

about how hard their work must be ; I could scarcely take

breath and walk about quickly up there let alone break up

stones by hand into smaller pieces for laying into tar.

India's mountain roads have exacted a heavy toll in the

lives and health of road workers. The Chang La road over

the pass to Drangtse, Lukung Post and Pang-gong Lake

was reputedly one of the worst.

When we finally reached the top of the pass, the wind was

icy despite the brilliant sunshine and snow blanketed the

rock in huge patches all around. Indian army soldiers in

camouflage stared at us from their dark green trucks as we

took pictures for the record beside a plaque declaring the

altitude of the pass above sea level. Prayer flags - strips of paper and cloth covered in Tibetan scripture - fluttered in

Page 16 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 17/45

the wind, strung out on long strings like clothes on clothes

lines, giving the powerful, desolate scene a slightly

incongruous, festive air. We piled back into the Gypsy and

left the hostile environment of the pass as quickly as we

could. The jeep trail was nothing more than a snaking pile

of rubble through the mountains and our tightly packed

condition did not prevent us from being jolted up anddown and from side to side with every foot of track

covered. We had started out at 8.30 in the morning and by

lunchtime we reached Drangtse, at 14,700 feet above sea

level, having covered about eighty kilometres in four

hours.

Drangtse was set in a silent, well-watered valley

surrounded by gigantic mountains, the highest peaks

smothered in plentiful snow. There were about twenty five

or thirty houses built in the sturdy, white-washed Ladakhi

style, strung in an irregular line a few yards away from the

banks of a winding stream that watered the meadows on

both sides. The meadows were covered in short gold and

green grass. Golden poplar and willow clumped heavily in

the village, all white and silent stone. The village walls

held together without masonry, relying on weight and

balance for stability and forming interstices between the

buildings. Suddenly I saw what Mr K. had hinted at: the

village monastery, prayer-flags in red and yellow aflutter,perched high up a steep hill like a small fort, on the edge

of a nearly sheer drop. A steep path, partly in the form of

rock-cut steps, led up to the monastery. I reached the main

courtyard with some difficulty, several hundred feet above

the valley. The monastery, silent and sunlit, appeared to be

deserted, Though the buildings looked old, the main

temple entrance was decorated with new frescoes. Mr K.

and had moved up into the second tier courtyard. My

asthma was beginning to impede my breathing seriously

now and I was panting heavily. After about five or six

minutes I had recovered my breath. I decided not to go

further up into the monastery as there were no monks to be

seen and I did not wish to be inadvertently intrusive. I

picked my way back down the rough, steep steps to the

village below.

The monastery was surrounded by a close outcrop of hills,

grainy, heavyªshouldered and tall. They seemed to form a

protective ring around it, patient guardians of their charge.It was a huge, open, but strangely secret sort of place, the

Page 17 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 18/45

effect enhanced by the lack of human voices and figures

despite the ubiquity of human dwellings. As I passed one

of the houses in the village, an unkempt youngish man

appeared at a gate, grinning. He invited me to have tea

which I amiably declined. I stopped to exchange a few

words. His name was Pema and he had no occupation.

Although related to a number of the Drangtse farmingfamilies, he himself did nothing. He did not look

physically disabled or unwell in any way but he had a way

of looking craftily sidelong and grinning widely at

inappropriate moments that suggested that he may have

had some intellectual or emotional disadvantage - it was

not definite enough for me to feel sure. I could not get him

to discuss his situation very logically, why he had no work

to do, how he found money to live, how he managed to

live on his own. His responses were vague. Pema found

out quite a lot about me except the fact that I was currently

living abroad. He told me that he had been to Leh and

even to Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir. This he

announced proudly as though he had been some

astonishingly far distance, almost to the edge of the world.

It made me realise how solid and compact his world was,

and how immensely large the world beyond must seem to

him, and also how large my world was but, in some

respects, a good deal less well defined than his.

"I was born here", he said, "so here I must stay. I cannot

live in the town because it costs money and I do not have

any." He laughed loudly and flashed me a sidelong look.

"No woman, no children : I live here by myself." He

looked me intently in the face, his expression now serious,

his brows furrowed. There was a strange yearning in his

look, as though he hoped I would find a way to take him

away from this place where he lived in silence and had no

one to talk to. He wanted bright lights, big city. He had

been to Leh and Srinagar, had eaten of the apple from the

tree of city delights and was never quite the same again.

Yet, he seemed also to be afraid to leave, here where the

people knew him and would see to it that he was fed and

watered and attended to if sick. For one such as him even

Leh may have been too big and anonymous and Srinagar

exhilarating but frightening like a ride on a fairgound giant

wheel: you can stay on it for a bit but not for long.

I looked around in the silence at the trees, at the lovely,blank blue sky, the golden willows. For me it was peace,

Page 18 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 19/45

remote, hidden space, champagne air. Here lived a man in

this peace, without money, in the sort of place which

stressed out professional types from big cities in India or

the West would pay a lot of money to get away to, away

from their pressures. Provided, of course, piped hot water

and bearer service in hotels were available.It was so easy

to romanticise the situation, but for this man it wasboredom, frustration, a trap.

I could not see Drangtse, however, turn into one of these

meditational circuses: it had too powerful an air of hidden,

serene secrecy about it for me to really imagine such a

transformation. Here there were only rusting bukhari

stoves to keep men and animals warm in thick-walled,

solid houses, cold water available from wells, parched

barley (rtsampa) and dried fruit to eat, and not much else.

Indian security issues kept it free of mass tourism - but for

how long?

Unlike Thikse monastery, there was no blaring from radios

or ghetto blasters, no advertising posters on village walls,

no corner shop with plastic food and household ware from

the towns. It looked as though the Drangtse people, by

virtue of their relative isolation, still had a choice about

how to live. So far, it looked as though they had chosen to

stay more or less as they had been before, for as long asthey were going to be able to. The gold of autumn willow,

the deep blue of the sky, the secretive ring of mountains,

the monastery huddled precipitously against the gaunt

flank of the hill, the bubbling stream, the sheep grazing on

the brilliant green meadows, that was all there was, that

was all, it seemed, there could be in such a place.

The road to Lukung took about two and a half hours of

hard driving through jolting rubble track. The stony

valleys climbed steeply up on both sides. Occasionally, ablack-haired yak raised its bison-like horned head to peer

suspiciously at us, its long belly hair hanging to the

ground. Great ranges marched parallel on either side of the

vehicle and in the distance, Mr K. pointed out the ice

peaks of the Chang Chenmo Range marking the southern

border of Chinese-held Aksai Chin. Soon after, we passed

a trail that veered off towards the Shyok (She-yog) valley.

There was no sign of humanity in all that silent, sunlit

wilderness till we came upon three tents. Two small boys

in local dress looked at us out of a wreath of smoke from a

Page 19 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 20/45

dung fire on which their mother was cooking. They stared

silently but without fear. We stopped and Mr K. chuckled

at them. Their faces broke into grins and they came

forward. Pictures were taken. The woman stayed where

she was, watching the little group from the fire, the wind

flapping at her wine-coloured gown. At one point we

passed a tarn, a turquoise jewel set in a stony-red coombe,its shining surface deep blue, peacock green and blush

pink, a mica mirror reflecting the face shattered of the

afternoon sun back into the sky. The tarn was a prologue

to the grand opening of the performance, the first view of

the western edge of the big lake which we finally

encountered, all of a sudden, as we rounded a great green-

shouldered hill.

We reached Lukung Post, a well-kept police building with

a railing around its forecourt jutting towards the lake. The

great depth of the lake rendered the colour of the water a

deep ink blue, even in the stunning late afternoon sunlight.

The jagged strip of dark blue water, narrow on the

approach, got quickly larger as we reached Lukung until at

the post it was like a narrow sea several kilometres wide,

its eastern end scores of kilometres out of sight, lost

among the twisting, kidney-coloured mountains. The air at

Lukung, 14,786 feet above sea level, was cold even in the

sun and a wind battered our exposed hands and faces aswe stumbled about, taking pictures. It ruffled the smooth

surface of the lake, leaving thousands of fine, virtually

unmoving, wrinkles like the skin of a monstrous lizard.

The salt lake was deathly quiet. It was devoid of fish, I

was told, on account of its high salinity. Its shores were

littered with shells, descendants of ancestors that lived in

the Tethys Sea of which the lake had been a part millions

of years ago till it was pushed along with the rest of the

Tibetan plateau all these thousands of feet up into the air

when India crushed slowly into the Eurasian land mass.

The general absence of plant and animal life was partly

responsible for the clarity and intensity of the colour of the

surface water. The knowledge that the lake was dead

despite the intense vitality of its colours made the water

appear as though it were somehow a metal rather than a

fluid, closer to the rock in essence than to organic matter.

The Pang-gong Range on the near side marched as

pyramids, sharp, pointed heads all of the same height and

shape, brown, dusted with snow. On the far side of thelake, a long spur of the Chang Chenmo Range rumpled

Page 20 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 21/45

and twisted like hills in a dream: sienna, russet, dark red,

sand-blasted gold, lizard green, salmon pink, duck-egg

blue, pale purple, etched against a cobalt, cloudless sky.

Small villages, Man, Spangmik, nestled in the rubble-

strewn approaches to the lake shore from the hills, fading

from sight in the slowly gathering darkness caused by the

steep shadows of the hills on the narrow valley down tothe lake shore. The track, if there was one, was atrocious.

The last time I was at Pang-gong Lake there was some sort

of proper jeep trail and I do not remember the terrible

olting we got this time round as Mr K. wrenched and low-

gear gunned his vehicle, twisting and turning, churning up

showers of sharp crunching stones all along.

I grew sick, then got better. I developed nausea and a

fierce headache. The sky grew dark after sunset, the pale

light, storm-like, remained as a scar in the sky above

rolling dark clouds crowning the tops of the hills on the far

shore. The hills blackened, became mysterious, flung

across the horizon like the cape of a sorcerer. In the fading

light the deep rose sunset was flushed against an

opalescent blue and milk upper sky quartered by dark

purple and flesh-coloured clouds, and in a while the angry,

pale colour was gone. In the middle of this psychedelic

loneliness, hushed except for the churning of the rubber

tyres, vast, somehow threatening and restless, a young boyappeared, alone in this enormous, deadly place, a stick and

a bundle on his shoulder. He stared as the vehicle went by

and raised his hand in a slow, automatic, almost absent

greeting which we returned. Where had he come from,

where was he going ? No doubt there was a village nearby

but being completely hidden from view, the huddled

buildings, white as they were, stayed shielded by shadow

from any reflective light. They appeared to vanish

altogether, as though conjured up in my feverish

imagination like a mirage, expressions of my desire for

human contact in all this overpowering, beautiful, terrible

desolation. The sense of abandonment was actually

enhanced, not relieved, by the appearance of this fragile,

solitary figure, popping up out of nothing. The child

himself seemed like a trick of the mind, like the appearing

and disappearing villages. I was overcome by a sudden

intimation of my own mortality, the way I did from time to

time in this terrible, beautiful place, something like the

way I did in the desert beyond Nyoma, twenty years ago.

Page 21 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 22/45

The landscape seemed to mock us, playing tricks with

colours, forms, perspectives, dropping things down in

front of us and taking them away in caprice, reminding the

photographers among us that the open wilderness was the

primary source of illusion and the original magician with

light, inventing thoughtlessly what all the artifices of the

deliberate will and ingenuity of the photographer couldnever emulate. A couple of Tibetan wild asses (skiang)

appeared dimly on the rubble-strewn valley, our first view

of these wild creatures of Tibet's immense highªaltitude

northern plateau. They wheeled and cantered off into the

dusk as our vehicle approached. I felt so nauseous that I

had to stop the vehicle and get out to be sick, my stomach

cramping painfully. I stood alone in cold, black space, the

vehicle only a few feet away but scarcely visible in near

pitch darkness. I really did think for a moment, in my

confused state of mind, that the jeep was itself part of the

illusion, that it would vanish as I walked back towards it,

that I was alone in this silent place, that I always had been.

I felt that the world of crowded humanity was a dream,

that I was on the point of waking from this dream to

realise that I and the emptiness around was all there ever

was or had been. Then came up and got a grip of my

shoulder, and the spell was broken.

The last hour of the journey to Chushul was made incomplete darkness, nothing whatever of the landscape

being visible. Our host was Mr K. who worked for the

Ladakh Scouts. He expertly followed an invisible stony

track in the soft glare of his headlights. He also switched

on a red strobe light mounted on the bonnet of the vehicle

which enhanced the peculiar, unreal quality of the journey.

The turning, flashing red light interfered with my forward

vision creating a confusing effect as in a discotheque but

he seemed quite happy with it and as he was the one

driving, I supposed that was all right. I was too sick and

tired to care. It was beyond my understanding how he

could distinguish a trail in those conditions : it was really

ust open country. Some of it was sandy with thick

tussocks of grass, and large stretches were rubble, the

sharp stones heaped thickly about and on which the tyre

marks of previous vehicles left little or no visible trace,

even, I discovered, in daylight let alone under the

conditions in which we were driving. Every few miles a

marker would appear, confirming that we were still ontrack. They were tall boulders or posts three or four feet

Page 22 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 23/45

high with a target motif painted on them, red centre in

white surround. Out of the darkness, they loomed

suddenly into view in the glare of the headlights like the

faces of astonished ghosts. Mr K. never missed one of

them. We had long since left the lake shore so there were

no other obvious directional guides in the landscape.

Visibility was limited to a few dozen yards ahead and tofive or six yards on either side of the vehicle. Occasionally

a hare would spring out in view, sitting stunned in the

headlights, and then it would spring for cover. Twice we

saw foxes, lean creatures with thick, bushy tails of a

colour somewhere between red and dark brown; it was

impossible to be sure. After some three hours of driving,

ghostly white buildings appeared and I thought, thank God

we've arrived! We had not. We passed these building and

moved on. Ten minutes later, we passed some more

ghostly buildings. These were not the end of the trail

either. Ten or fifteen minutes later it happened again.

Again the sense of unreality pressed urgently in my mind:

I began to think that I was trapped in a crazy dream which

played the same images repeatedly like a faulty slide

projector, and that it would never end. Finally, we arrived

at an iron bridge, broken down and trailing one huge rusty-

metalled end into the bouldery bed of a stream. Mr K.

manoevered the vehicle through the stream with a

tremendous amount of jolting, the Gypsy's suspensiongroaning under the strain. I cracked my head a few times

hard against the side of the jeep but I scarcely noticed, I

was so dazed.

About ten minutes beyond the iron bridge, we finally

arrived at Chushul Post which, at 14,566 feet above sea

level, was a huddle of buildings of thick stone and plaster.

The main building housed the senior officers and guests of

the force and was comfortably decorated with reed carpets

and snug bukharis. The bukharis were insecure,

dangerous-looking contraptions of rusted metal. A

cylinder functioned as a burner-oven, a pipe in segments

fed evil-smelling kerosene into the oven, and an exhaust in

several segments of thick piping snaked crookedly

upwards and through the roof. The whole effect was like

that of an aga though much cruder, smaller and unreliable

looking. The bukhari was typically placed in the centre of

the room. Much of the winter life in the post, when not out

on patrol in temperatures of minus 40 degrees Centigradeand below, would be spent huddled around these

Page 23 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 24/45

contraptions, trying not to burn one's self by knocking into

them. Once they got going, they did keep the rooms

reasonably warm. Electric lighting was from solar-

powered cells. Mr K., we discovered later, was an

enthusiastic proponent of solar powered energy of which

more, later. Kerosene lanterns hissed, giving out a dirty-

looking light. In the dining room, genial border police sator stood around us, grinning politely, and making stilted

small talk. After an excellent dinner of parathas (fried,

unleavened bread), several vegetable curries and a chicken

curry finished off by a sweet milk dessert, we retired to

our rooms. We huddled around the bukhari which roared

and burbled softly, and looked out through the small,

smeared-glass single window pane at the brooding, jagged

shadows of the mountains. The cold, dimly seen landscape

seemed somehow to suggest not merely an indifference to

the fragile presence of life, but a kind of brooding

hostility, a positive hatred of life. A dog howled

mournfully into the moonless night and the wind rattled

the projecting corrugated iron roof of the single-storey

building as we shoved ourselves into sleeping bags and

blankets.

However, we were not going to sleep just yet. Mr K.

turned up in our room in his striped pyjamas. Perhaps it

was his usual serious, slightly suspicious expression andhis straight, military bearing, feet planted slightly apart for

balance, that gave him a faintly comical look in this night

garb. He sat on the edge of my bed and regarded me

wordlessly, head cocked slightly to one side as though

listening for a faint sound. As none was forthcoming

beyond the noises already indicated, I gave in to my not

always suitable predilection for conversation. We talked

about social and cultural trends in Ladakh. Mr K. took a

staunchly conservative, even isolationist line. supported

my argument for a more open, less defensive approach to

outside influences but it did not go down well and the

discussion began to border on the acrimonious before I

realised that I was probably upsetting our generous host

and tailed off. Eventually Mr K. decided to turn in himself

and bidding us amiably good night, he withdrew. We

drifted uneasily into a disturbed sleep. My breathing was

still laboured in the thin air, and I slept fitfully, catching

only an hour or two of undisturbed sleep in between

erking awake and gasping for breath.

Page 24 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 25/45

Curiously, when morning came and the sun shone brightly

in the cold, still air, my eyes snapped wide open, my

stomach had settled, my mind was alert and, along with

the others, I was ready to enjoy the day. For some reason,

disturbed nights did not mean tiredness in the day time. I

noticed something of this effect in Leh, also. Perhaps in

Ladakh, I just did not need my normal quota of sleep.Before breakfast, the genial second in command at the

post, a well-educated South Indian, joined us for a few

minutes. We were pleased to find someone at the post to

have a conversation with. He was a big, well-built man in

his thirties, bespectacled and smiling, looking faintly like a

bank manager in disguise. I described my reactions to the

extraordinary, disturbing beauty of the Pangong Lake area,

and suggested that I thought the best thing for eastern

Ladakh would be to turn the whole area into a protected

region, such as a national park. Its striking and unique

environment would make a case for this very easy, if not

obvious. The flora and fauna could be relatively easily

protected since human habitation was thin and the nomads

had an ecologically sound relationship with their

environment. It was not necessary to interfere with their

way of life, and a policy of guided tourism - the new

buzzword "eco-tourism" inevitably came to my lips -

could ensure that not only did the tourists bring some

benefit to Ladakh but also that they were not allowed todisrupt the environment unduly. The big man smiled even

more genially and, without a trace of irony, agreed that

tourism was a good idea. What Pangong Lake needed was

plenty of tourist hotels, sports and wildlife observation

facilities, a few good bars and a discotheque. That would

turn it around from a boring dump into somewhere worth

visiting. Who wanted a wilderness ?

I got out a little early, to take a walk. Cameras swinging

from our necks, wrapped up warmly in duffle coats and

leather jackets, thick socks, boots, gloves and mufflers, we

boot-crunched our way over a thin-frost ground to the

entrance of the post and out in the direction of the village.

Brown, dun and cream-coloured mountains roped around

the horizon. The sun dazzled. It was very cold. One of the

uniformed men we asked told us that the temperature that

morning at eight o'clock, despite the strong sunshine,

registered at two degrees centigrade. The low, white

buildings of Chushul village were scattered around thevalley, and women were already working in the fields.

Page 25 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 26/45

eased into an alleyway near which three women were

threshing grain, emitting a curious rythmic, rattling whistle

as they did so. A white dog barked at us. took pictures, the

women grinned, apparently pleased and embarrassed at the

same time. When we returned to our building we found a

generous breakfast laid out and Mr K. in hearty good

humour. Backs were slapped as curries again were served.I remember Chushul, along with Dungti post, for the

outstanding food by frontier standards in contrast to the

poor quality of cooking in Leh and elsewhere. All the

good cooking in Chushul was down to a shy young man

from Punjab who was introduced to us and whom we

thanked for his good work. The taste and quality of food is

always important, but in the conditions of post life it feels

like the only thing that matters and a good cook is one of

the most precious assets post personnel can have to make

their duties bearable.

The whole of the morning after we left the post was spent

near and on the Sirijap-Chushul battlefield and beyond,

scene of the sad and lonely defeat of defending Indian

forces against invading Chinese PLA troops in October-

November 1962. The details behind the dispute are well

documented. Chairman Mao's China not only crushed and

absorbed Tibet but laid claim to various border areas also,

including Ladakh. The 1,500 mile MacMahon Linedemarcating the borders of India, China, Nepal, Sikkim

and Bhutan at the Simla Agreement in 1914 was never

ratified by the Nationalist regime in China and this was

used as part of the rationale for Chairman Mao's claim.

China occupied Aksai Chin, an area in the north-east of

Ladakh that Indian forces had never actually held.

It is one thing to read the facts in the dry, unemotional

texts of historians and documentalists, quite another to feel

it as though one is reliving the experiences of the Indian

troops who fought and died there. We walked slowly,

breathing heavily in the cold, clear air, up to the

monuments dedicated to the dead soldiers from every part

of India: Sikhs, Jats and Rajputs from the plains of the

north, Tamils and Malayalis from the tropical south. The

Gorkha monument was decorated in green with two

crossed kukris glinting gold in the sun. The dedication

stones were carefully maintained and willows were

planted in ranks around them, rustling their red-goldleaves. The monuments were located several kilometres

Page 26 of 45Thoughts, Rants and a Travelogue: Ladakh, a travelogue

19/04/2009http://cerronevado.blogspot.com/2005/01/ladakh-journey.html

8/14/2019 Ladakh Diary on Blogger

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ladakh-diary-on-blogger 27/45

from the battlefield itself, and perhaps two kilometres

from the police post. We drove towards the battlefield and

stopped in the middle of a huge plain, completely devoid

of human habitation or even traces of visits by humans

such as tracks, camp litter or remains of fires. The plain

was of hard, cracked mud, dun-grey in one part and

blueish-grey in another, separated in huge stretches bytracts of fine sand knotted together by clumpy red bushes.

The cracking gave the mud plains the appearance of a

gigantic mosaic, a shattered dish whose pieces had just