La Guitarra y Su Musica Sparks

-

Upload

pablo-arroyo -

Category

Documents

-

view

231 -

download

1

description

Transcript of La Guitarra y Su Musica Sparks

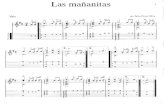

IntroductionWhat was the nature of the instrument that sixteenth-century Spaniards, Italians,Frenchmen, and Englishmen knew as the guitarra, chitarra, guiterre, and gittern,respectively? Was the Spanish vihuela de mano considered a guitar? What did Italianmusicians in the late sixteenth century mean y the terms chitarra spagnola, chitar-riglia, chitarrino, chitarra italiana, and chitarra napolitanat!ccording to documentary evidence, including contemporaneous sources of musicfor the instrument, the typical sixteenth-century guitar was a small, figure-"-shaped,four-course, trele-range instrument, tuned a fourth or more higher and aout one-third the si#e of a modern $lassical guitar% &ater in the century the Italians would alsorefer to it as chitarrino, chitarra italiana, and chitarra napolitana% 'he somewhat largerfive-course guitar, which the Italians called the chitarra spagnola, first appeared in thethird (uarter of the sixteenth century% 'he still larger, six-course, lower-range, figure-"-shaped Spanish vihuela de mano, and its Italian counterpart, the viola da mano,were not considered guitars% Indeed, as will e seen, all availale evidence from thesixteenth century indicates that the guitar had its own separate and distinct character,function, tunings, and repertory, and that sixteenth-century players, theorists, andcomposers regarded the vihuela not as a guitar ut as a figure-"-shaped Spanishe(uivalent of the lute%Spain: La Guitarra de quatro or denesIn his set of variations on the $onde $laras ground) for vihuela *+elphin demusica % % %),-"., the excellent Spanish composer &uis de /arvae# *fl% ),-0-,0. provides con-clusive evidence that the guitar and vihuela were regarded as two distinct instrumentsin sixteenth-century Spain% 1e specifically heads one section of his fifteenth variation2contrahaciendo la guitarra2 *in imitation of the guitar., and for this section employsonly the four inner courses of the vihuela, which comprise the interval pattern*though not the pitches. of the four-course guitar%3ore evidence from mid-sixteenth-century Spain is provided y 4uan 5ermudo*c% I ,Io-I ),6,., who pulished a ook of music theory, Ellira primo de la declarationde instruments, in 7suna in ),89 and an expanded edition, El lira llamado declarationde instruments musicales, in I,,,-: 5ermudo is the source of the earliest tuning in-formation we have for the guitar% 1e also explains the procedures for intaulatingpre-existing vocal and instrumental music for the guitar, vihuela, and andurria? 1edescries the guitar as smaller than the vihuela *2mas corto2, ch% 6,., and as generallyhaving only four courses,8 with an interval pattern resemling the second to fifthcourses of a vihuela% 'he specific tunings for guitar given in Ex% i% i are found in &ira(uarto *ch% 6,.% ;oman numerals designate the courses%!s illustrated, in oth the 2temple a los nuevos2 *new tuning. and 2temple a losvie 1owever, unlike 5ermudo, he does not specify nominaltunings for either the guitar or the vihuela%Part IIn addition to vihuela solos, songs to the vihuela, and a solo for harp or organ, 'resliros de mmica includes six solos for the four-course 2guitarra2%)" 'he first is a fantasiain imitative style using the 2temple vie also includes five guitar ta-latures that were copied from &e ;oy2s printed ooks% 'he collection for four-courseguitar pulished in !ntwerp in ),>0 y Eierre Ehalese and 4ean 5ellere under the&atin title Selectissima elegantissima(ue, Callica, Italica el &atina in guiterna ludendacarmina% % ,:" includes ninety-two items pirated from &e ;oy2s ooks I-H, as wellas the talature parts for his voice and guitar pieces, ut not the vocal parts in staffnotation% 'he remaining sixteen items in the Ehalese and 5ellere pulication alsoseem to e y &e ;oy, ut are not from any of his surviving ooks%:9'he Ehalese and 5ellere print egins with instructions in &atin for tuning andplaying the guitar% Some scholars have surmised that they were from &e ;oy2s losttutorD however, +oson, Segerman, and 'yler-0 have shown that they are actually avery ad adaptation for guitar of Seastian Hredeman2s cittern instructions from a),6" pulication that was also printed y Ehalese% Ironically, these garled, mislead-ing instructions serve as another indication of how closely associated the guitar andcittern were in the minds of sixteenth-century musicians%'he two pulished series y 3orlaye, Corlier, &e ;oy, and 5rayssing comprise anextensive and varied selection of music for an instrument that had ecome, y thistime, a true fixture in the musical life of France% 4ust how popular the guitar hadecome is revealed in a short anonymous treatise entitled +iscours non plus melan-coli(ues % % % *Eoitiers, ),,6.%-) Its author oserves that formerly the lute was used morethan the guitarD however, during the last twelve or fifteen years everyone has taken tothe guitar, and today there are more guitarists in France than in Spain%-: 1e also men-tions that the lute and guitar have their strings arranged in doule courses, except forthe first, which is single, and thus corroorates 5ermudo2s statement that the guitarhas seven strings in four courses% !fter explaining how to divide up thevirating string length of a lute from nut to ridge in order to find the proper places forthe tied frets, he says that you end up with a string length of two or three feet *2pie2.,ut when you calculate the fretting for a guitar, you are working with a string length ofonly a foot and a half--! manuscript from aout ),", *F-En 3S fr% 9),:., intended y its author 4ac(ues$ellier as a didactic discourse on a wide range of suIn F%)9>> eight pages of ;owotham2s lost gittern ook were recovered%)" Four ofthem, now in the Han Eelt &irary of the Lniversity of Eennsylvania in Ehiladelphia*no shelf numer., are headed 2!n instruction to the Citterne2 and contain incomplete pieces in French talature for a four-course instrument tuned to guitar intervals% 'hecaptions on two of the pages are in French, 2Elus diminues2 and 2Elus fredonnes2,which indicate here, as they do in some of &e ;oy2s lute pulications, that these are themore emellished and the much more emellished versions *in terms of the rapidityof the passagework and the smaller note values. of well-known pieces% 'he plain ver-sions of the pieces are not among the fragments preserved here% /either are there titleson the fragments, although one is an exact concordance of the complete 2Elusdiminues2 version of the !lmande% &es ouffons from Ehalese2s ),>0 print, and is fol-lowed y the 2!2 section of the 2Elus fredonnes2 version of the same piece%/ot long after the existence of the Ehiladelphia fragments ecame known, anothertwo pages were recovered in Shrewsury y Eeter +uckers, who, several months later,found two more%)9 !stonishingly, the four new pages turned out to e from the samesection of the ook as the previously recovered Ehiladelphia fragments% It is now pos-sile to assemle a hypothetical se(uence of the pages as follows? a Ehiladelphia pagecontaining a short untitled prelude *to demonstrate the ma6-arpiece% It would not e difficult to reconstruct its missing opening ars%7n the same +uckers page is &es uffons, which turns out to e the plain version ofthe piece mentioned previously in the description of the Ehiladelphia fragments% It isan exact concordance of the plain version of the !lmande% &es ouffons from Ehalese2s),>0 print% 'he next Ehiladelphia page contains the aforementioned 2Elus diminuesversion of &es uffons, and the Ehiladelphia page which follows, the aforementioned 2!2section of the 2Elus fredonnes2 version of the piece% 'he 252 section of this versionwould have een on the next page, which, unfortunately, is still missing, and the final+uckers page contains the last eight measures of it% 'he 2Elus fredonnes2 versions ofthis and other &e ;oy pieces are not included in the Ehalese print, perhaps ecause he0"% 'he music isvery simpleD most of the pieces have no arlines or rhythm signs, and it is clear thatthey are the work of an amateur scrie, notating as est she6 could, an aide-memoirefor future reference% /evertheless, the contents, which have not een identified or dis-cussed previously, offer not only an anthology of some of the guitar2s most popularrepertory, ut also some valuale ancillary information%'he manuscript contains twenty short guitar pieces in all, eginning on folio )8with an untitled setting of the 5ergamasca in triple time, followed y a setting of;uggiero% Folio i8v includes a piece entitled &afranchina, which is a setting of thepopular commedia dett2arte song &a ella Franceschina% Folio ), contains a setting ofthe $avalletto #oppo, which is the accompaniment to a popular song ased on theEassame##o antico ground% /othing is known aout 3algarita on folio i,v% Folioi6rWv contains an !ria da cantare, a harmonic formula to which poetry was sung%> /otsurprisingly, the harmonies are that of the most fre(uently used ground for this prac-tice, the ;omanesca% !n unidentified Eavana appears next *fo% )>., followed y twountitled and unidentified pieces on folios iyv and )"% 'he next two pieces are entitled&irum and $iciliana *fos% )"H and )9.D and on folio )9H there is a 3atacinata, the Italianversion of the French 3atachines, a semi-ritual dance that generally portrays a mockattle or sword fight% 'he folk-religious version of the 3atachines survives to this dayin 3exico and elsewhere%" 'he music for the Italian 3atacinata, as for the other six-teenth-century versions, consists of two ars of I and two ars of IH, with an offeat or syncopated rest from ar - into 8% 'he four ars are repeated again and again until thedance ends%9'he next piece *on the same folio., entitled 5uratinata, has