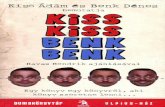

KISS - Kashmir 1947-48 English

-

Upload

peterakiss -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

description

Transcript of KISS - Kashmir 1947-48 English

-

1

Peter A. Kiss

THE FIRST INDO-PAKISTANI WAR, 1947-48

Abstract: The confrontation between India and Pakistan dates from the first day of their

independence from the British Empire, and the first war they fought was over the possession

of Jammu and Kashmir. The war was a limited affair limited in its goals, in a limited

theatre, with limited means. It was the first modern war in which one of the belligerents

(Pakistan) relied on an artificially created and nurtured insurgency in the target area to realize

its political goals. The experiment partly due to lack of doctrinal foundations and lack of

experience had only limited success, but its results encouraged Pakistan to rely on

insurgents and irregular militias in the enemy's rear in it later wars.

Keywords: India, Pakistan, Partition of India, Jammu and Kashmir, asymmetric warfare,

Pathan tribal militia, Azad Kashmir

This short and limited war is a fascinating story for several reasons. Its most significant

element is the employment of non-state actors as combatants in service of a states interests.

The employment of non-state combatants was only partly successful, but the events have

shown how a modern state can deploy the principles, tactics, techniques and procedures of

asymmetric warfare against another, much stronger state. The events of the war also call

attention to the fact that contrary to the contemporary western attitude which lingers on to

this day there is absolutely no difference between western and Asian soldiers, when the

latter are properly trained and led. Asian officers are able to plan and execute large-scale

operations, control, move and support divisions and corps without the benefit of western

advisors, and their command performance can meet the highest standards. Asian soldiers

under Asian officers and NCOs can fight with as much skill as, and their self-sacrificing

heroism and professional behaviour can be a match to, or even surpass, any European or

American regular force.

THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In spite of the economic and strategic advantages the colonies represented, maintaining a

large colonial empire was a huge burden for Great Britain after World War Two. The Labour

-

2

Party made the dissolution of the empire a key part of its post-war agenda, and following its

electoral victory in 1945 it set about granting independence to those colonies that were

sufficiently developed to stand on their own as sovereign states and India was among the

first.

Although the Muslims were in a significant numerical minority in India, they had dominated

the subcontinent for hundreds of years. This dominant role ended by the middle of the 19th

century, as the European empires gradually extended their rule over India. The Muslims could

not come to terms with the loss of their power, influence and privileges and adjusted to the

new social order with great difficulty. They barely tolerated the rule of the Christian infidels,

and simply could not imagine living under the rule of peoples they had subjugated and

despised for centuries the Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs even if independent India

promised secular democracy and free exercise of religion.1 Their mass organization, the

Muslim League, insisted on creating a Muslim state as part of the independence process.

Pakistan the Land of the Pure was created by combining the Muslim-majority parts of the

country (in the west Sindh, Baluchistan, the Northwest Frontier Province, and the western part

of the Punjab, and East Bengal in the east). (See Figure 1.)

According to the law governing the independence process (the Independence of India Act) the

rulers of Indias nearly 600 states could decide to join India or Pakistan, or remain

independent. Most rulers had no real choice: geography and demographics made the decision

for them, but in the case of Kashmir the question was more complicated.2 The state's location

on the borders of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and China made it a strategically important

place for both India and Pakistan. The ruler was Hindu, but the majority (about 2/3) of the

population was Muslim. However, even among the Muslims there was no consensus on the

countrys future: the most influential politician, Sheik Abdullah was opposed to Indias

partition, but if that had to be, then he stood for Kashmiri independence. The Maharaja could

not or did not want to make a decision: he hoped that if he delayed the decision long

enough, Kashmir could become an independent, sovereign state.

India could perhaps have accepted an independent Kashmir, but Pakistan insisted that the

Muslim-majority state should join the Muslim Pakistan. Pakistan's head of state, Ali Jinnah,

was ready to settle the matter by force, but that would have led to open war with India and

1 As Indias independence was becoming a reality, the Muslims had reason to fear Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist,

Christian, Jaini, Jewish and other religious payback for centuries of abuse. (Goel, no year) 2 "Kashmir" as a geographic term is applied to the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir; to the Pakistani state of

Azad Kashmir; to the Kashmir valley, and to the independent principality of Jammu and Kashmir.

-

3

the Pakistani armed forces, which were just being created, were nowhere near strong enough.

In order to avoid the embarrassing spectacle of former colonies obtaining independence and

immediately attacking each other, the British government would also have prevented open

conflict. Even before independence was declared, the Pakistani government already applied

economic pressure: it halted traffic on the only railroad line going into Kashmir, confiscated

Kashmiri trucks and blocked the importation of essential staples and fuels (food grains, sugar,

salt, gasoline, household kerosene) into Kashmir. Economic blockades generally work slowly,

and it was not different in Kashmirs case either. Since the blockade did not achieve results

fast enough, the leading politicians of the Muslim League and senior officers of the armed

forces (either with or without Jinnah's approval) prepared a plan which promised a swift

resolution, yet kept the risk of open conflict with India at a minimum. The plan very nearly

succeeded.

Figure 1. India and Pakistan after August 15, 1947. The red oval marks Jammu and Kashmir. Source: http://www.oberlin.edu/faculty/svolk/367f07syllabus-main.htm

-

4

SPACE-FORCES-TIME-INFORMATION FACTORS

Space Kashmir's Military-Geographic Characteristics

Jammu and Kashmir has an area of 222 000 square km; its north-south extent is 640 km, east-

west it is 480 km. Only small patches of this area are suitable for permanent human

habitation. The altitude above sea level varies between 300 and 7000 meters. Tall mountain

ranges divide the country into the following regions:

- In the north, between the Karakoram Range and the northern peaks of the Himalayas the

Northern Areas consist of the Indus valley, Gilgit, Hunza and Baltistan.

- Southeast of the Northern Areas Ladakh consists of the Ladakh and Zanskar ranges and the

Indus valley.

- The Kashmir valley and the state's summer capital, Srinagar, are south of the Himalayas.

- To the southwest, beyond the Pir Panjal range is the Jammu region and the city of Jammu,

the winter capital.

The mountain ranges are not only recognizable boundaries between the regions, but as nearly

impenetrable barriers, also play a significant role in maintaining the local ethnic, cultural and

linguistic differences. The ranges also divided the theatre of operations into four nearly

entirely isolated sectors. Possession or loss of the few narrow mountain passes played a

decisive role during the operation. (See Figure 2.)

The climate is determined by latitude (about the same as Morocco), as well as altitude. Jammu

(average altitude: 305 m) is subtropical. The Kashmir valley (1700 m) is temperate

continental, the Northern Areas and Ladakh (2500-3500 m) are high mountain deserts.3 In the

mountain ranges the unpredictable weather makes flying a hazardous undertaking. Due to the

thin air the use of parachutes is risky, and the performance of internal combustion engines is

inferior to that at sea level. Troops transferred from low-lying regions (primarily the Indian

forces) suffered greatly from the lack of oxygen and the intense cold. For the Pakistani forces

(organized primarily from local militias) this was far less of a problem.

In 1947 the infrastructure of Jammu and Kashmir was quite primitive and whatever there

was depended on Pakistan: the all-weather roads followed the river courses and led through

Pakistani territory. From India there were only two fair weather roads into Kashmir: the dirt

road from Pathankot to Srinagar, which ran through the Banihal Pass at 2700 m elevation, and

the caravan trail from Manali to Ladakh. Only a spur of Indias well-developed rail network

ran into Kashmir but that also ran through Pakistani territory, through Wazirabad. The

3 The elevation figures are for the low-lying areas of the regions only. The peaks are between 5000 and 7000 m.

-

5

throughput capacity of the roads and the weight bearing capacity of the bridges strictly limited

the numbers, equipment and supply of the forces that could be deployed.

The Srinagar and Jammu airfields were suitable for landing modern transport aircraft, but

Srinagar was usable only in daylight. The larger lakes and some stretches of the rivers were

navigable by small boats, but this had very infrequent and only limited, local tactical

significance (for example in infiltrating small raiding parties).

Figure 2. The original borders and current partition of Jammu and Kashmir. Source: Central Intelligence Agency, Langley, 2003

-

6

Forces

The Indian Army had been one of the most significant components of the British Empires

armed forces; the Indian Navy and the Indian Air Force were far less important, but they were

far from negligible forces. During World War II the armed forces of British India expanded to

2 500 000; Indian forces fought in Africa, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. The officer

corps was 2/3 British, but as time passed, an increasing number of Indian officers also reached

substantial rank. In 1947, following post-war demobilization, the strength of the armed forces

was about 460 000 (12 000 officers and 440 000 non-commissioned officers and other ranks).

The various Indian principalities had their own armed forces; these amounted to another

75 000.

According to the Independence of India Act, two thirds of the personnel and material

resources of the armed forces were to go to India, one third to Pakistan; as the princely states

joined either India or Pakistan, their forces were also incorporated into the two national

armies. Nearly 150 000 men and 160 000 tons of war materiel had to be shifted to Pakistani

territory from India4 and from the other colonies of the empire. Due to the shortage of the

available time a fair and equitable division of materiel (and particularly of installations) was

impossible. The airbases were mostly in Pakistani territory, but only nine of the 46 training

establishments were there. The arsenals, supply dumps, repair installations and naval bases

were all in Indian territory.

The commanders of the armed forces were British officers (General Messervy in Pakistan,

General Lockhart in India). Instead of the Pakistani and Indian heads of state, they reported to

a British Commander In Chief (Field Marshal Auchinleck). Their actions and decisions served

the interests of Britain, rather than the national interests of India and Pakistan.

The Indian Armed Forces

In the division of British Indias army the new Indian Army obtained 88 infantry battalions,

12 armoured regiments and 19 artillery regiments.5 These were organized into 10 divisions

(nine infantry and one armour), an independent armour brigade and two parachute brigades.

Loss of entire units and one third of personnel significantly reduced the battle readiness of the

forces. However, several entirely Hindu, Sikh and Gurkha battalions were unaffected. Even

the mixed battalions generally lost only one or two companies, but the units themselves, with

4 It is a frequently repeated Pakistani complaint that the Indian authorities sabotaged the delivery of war materiel:

instead of functional weapons, munitions and equipment they delivered mostly scrap. 5 Following the British pattern of organization, the armour, cavalry and artillery regiments were in reality

battalion-sized formations.

-

7

their special traditions and histories, remained and served as the cores that could be

augmented by newly recruited personnel and could be organized into larger formations.

Local militias either spontaneously organized, or raised by the Indian Army also took part

in some operations, especially in Ladakh.

The Indian Air Force was a respectable force, even after some of its equipment and

personnel were transferred to Pakistan. It had well trained and experienced personnel (900

officers and 10 000 non-commissioned officers and other ranks, 820 civilian technicians and

administrative staff), and was equipped with modern aircraft (Tempest and Spitfire fighters

and C47 Dakota transports). These forces were organized into seven fighter squadrons and

one transport squadron. The transport squadron had only eight C47 aircraft, but its lift

capacity was multiplied by renting civilian airliners. Bomber squadrons were organized only

in late 1948, but these took no part in the war. The greatest problem of the Air force was the

shortage of adequate bases.

The Indian Navy came into existence with 19 warships (frigates and smaller surface

combatants) and 15 other vessels (tugs, landing craft, etc). The Navy did not play any role in

combat operations.

The Pakistani Armed Forces

The centuries of rejectionist attitude of Indias Muslims had a particularly grave effect on the

organization of the Pakistani Army. In the British Indian Army there were several entirely

Hindu, Sikh and Nepali (Gurkha) battalions, but very few entirely Muslim ones. Pakistan

received 33 infantry battalions, six armoured and nine artillery regiments from The British

Indian Army but most were not complete units, only their various elements. Many Muslim

soldiers opted for service in India, so even the Muslim companies were arriving in Pakistan

without their full complement. Therefore, most formations lacked the hard and firm core,

which could have been organized into larger combat formations. The shortage of officers was

another serious problem: the planned 150 000-man army needed a minimum of 4 000 officers,

but there were only 2 300 available, among them a major general, two brigadiers and 53

colonels.6 As a temporary solution British and other European officers were hired. In spite of

the difficulties, organization proceeded fairly quickly. New regiments were formed by

amalgamating parts of old ones; under strength formations were filled with units and men

arriving from India, Africa, the Middle East and the other parts of Asia, as well as new

recruits. In August 1947 a two-brigade division (the 7th) was formed in Rawalpindi. By

6 Hassan, 2004. p. 32

-

8

October that year there were already ten infantry brigades and one armour brigade (with 13

light tanks) guarding Pakistans borders. The brigades were organized into four divisions in

West Pakistan and one division in East Pakistan.

Pathan tribal militias from Pakistans Northwest Frontier Province played an important role

in the Pakistani operations in Kashmir. Every Pathan tribe was instructed to raise a lashkar

(battalion) of about 1 000 men, to serve as assault forces. In September 1947 the lashkars

were concentrated around the border garrisons, where they were provided with arms,

ammunition and vehicles.7 The Pathans were a warlike people, but they were no soldiers.

They were familiar with small arms, but could not operate advanced weapons and

communications equipment. They were masters of the tactics commonly employed in tribal

warfare (raiding, hit and run attacks, ambushes, long distance opportunistic sniping), but they

were not familiar with the principles of modern tactics, and military discipline was completely

alien to their nature.8 To compensate for some of these shortcomings every lashkar had a

number of Pakistani officers and non-commissioned officers (either recently discharged or

on leave) assigned to it to operate the communications equipment and crew-served

weapons, and to provide tactical advice.

Kashmiris in favour of joining Pakistan established local volunteer militias, first in the area of

Poonch, later in other areas of west and south Kashmir. A prominent politician of the Muslim

League, Kurshid Anwar, became the commander of the militias.9 The militias fought

primarily in the vicinity of their recruiting areas, and gradually became the semi-regular

forces of the provisional government of Azad Kashmir (Free Kashmir).

Three aviation squadrons formed the nucleus of the Pakistani Air Force. Personnel strength

was 220 officers (among them 65 pilots) 2 000 non-commissioned officers and other ranks,

and 400 civilian technicians and administrative staff. The equipment consisted of modern

fighter (Tempests and Spitfires) and transport (C47 Dakota) aircraft. The air force was

initially organized into two fighter squadrons and one transport squadron. As Pakistan had

been British Indias western border region and its initial line of defence against a Russian

threat, the three squadrons had a choice of seven airbases. The Air Force played only a limited

role in the course of events: Pakistan wanted to maintain the pretence of having nothing to do 7 According to Indian sources the payment promised to the lashkars was to loot the Maharajas palace and

treasury in Srinagar. Their logistic support was minimal: they were issued weapons and ammunition in their assembly areas, but subsistence, billeting and treatment of their wounded was up to them obviously at the expense of the local population.

8 Much of this assessment holds true of the Pathans to this day. 9 The weak point of the militias and of the entire enterprise was the lack of firm, centralized leadership.

-

9

with events in Kashmir in any case, the two fighter squadrons could not have stood against

the much stronger Indian Air Force.

The Pakistani Navy commenced operations with eight warships and eight other vessels, and

no naval bases. The navy played no role in the Kashmiri operations.

The Kashmiri Forces

Kashmir had its own armed force: about 9 000 men organised into four brigades (a total of

eight infantry battalions) as well as a household cavalry regiment. Kashmiri units participated

in the wars of the British Empire under their own officers and had some battlefield

experience, but the standard of their training was not particularly high. As a part of the British

Empire, Kashmir had had no reason to fear a foreign invasion, therefore the army performed

border security, constabulary and parade functions. A major problem was that nearly one

fourth of the personnel were Muslims, who sided with the Pakistani forces in the first days of

the conflict. In the course of events some of the non-Muslim units were disbanded, others

were amalgamated into the Indian Army.

Time

Studying the timeline of landmark events, it is surprising how quickly they followed each

other. The immediate preliminaries, from Indias partition to the first attacks by the Pathan

tribal militias, took only four months. The major combat operations, from landing the first

Indian troops in Kashmir to the ceasefire agreement took hardly more than a year. With the

electoral victory of the Labour Party in England independence was undoubtedly assured, and

the most closely affected local political decision makers probably made some plans in

advance. But the devil is in the details and detailed plans could be developed and executed

only after Parliament passed the Independence of India Act, and the local political elites

learned of the plans and intentions of the British administration that was still in control of

Indias government.

From an operational perspective, time was not on the side of Pakistan: the initial operations

required close timing and had to be executed within narrow time-constraints. When these

failed, Pakistan could not match the pace at which India built up its forces in the theatre. On

the other hand, time may have served Pakistan strategically. With the passage of decades the

international community seems to have accepted Pakistan's occupation of the Northern Areas

and western Kashmir as permanent. On the other hand, legitimacy of India's sovereignty over

the rest of Kashmir has been put into doubt by continuous Muslim insurgencies in the

Kashmir valley and to a lesser extent in Jammu (supported by Pakistan), as well as Pakistan's

diplomatic efforts.

-

10

Information

Dividing British Indias intelligence organization, the Intelligence Bureau, was also part of

Partition, but neither India, nor Pakistan benefited from this. They took over empty offices

and bare shelves: the British destroyed the Bureaus holdings. In any case, neither country

would have profited much, even if the Bureaus files had remained intact. The Information

Bureaus primary function had been to support the perpetuation of British rule, and the

information it had collected on individuals and organizations that threatened that rule would

not have been useful in the conflict.

Thus, Indias government and armed forces were deaf and blind on August 15, 1947 the day

of independence. Pakistan fared only marginally better: the director of the IB (Gulam

Mohamed) and much of its staff were Muslims and chose to enter Pakistani service although

they took no useful information with them, they did have the professional skills needed to

build up an intelligence organization quickly.

At the beginning of the war Pakistan had a clear informational advantage, nevertheless. It

could focus its available intelligence assets on the selected target area, and as the belligerent

with the initiative, it knew when, where and in what strength it was going to attack. Pakistan

could not retain this advantage for long, once operations commenced.

THE BELLIGERENTS PLANS

Independent India has always been more fortunate with its generals than with its politicians

(perhaps starting with the heart and soul of independence, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi).

The Indian political elite that came into power in 1947 was strongly influenced by Gandhis

philosophy of ahimsa (nonviolence): peace-loving India will have no need for strategic

defence plans or intelligence organizations perhaps it could even do without armed forces.

Without a functioning intelligence organization neither the Indian government, nor the armed

forces were provided with timely and reliable information on the events in Kashmir, so they

did not prepare any plans either to seize Kashmir by force, or prevent a Pakistani attempt to

do so.

The situation was different in Pakistan. When the economic blockade proved to be

ineffective, Pakistani politicians and the officers of the armed forces drew up a plan

(Operation Gulamarg) for a faster and more decisive resolution of the problem:

- irregular forces (primarily Pathan tribal militias) launch raids into Jammu and Kashmir

along the border, in order to force the dispersal of the state forces into many small

defensive packets.

-

11

- a revolutionary movement in the Northern Areas (that could not be reached from India)

shakes off the Maharajahs rule and declares the territorys accession to Pakistan;

- militias raised in the Northern Areas launch an offensive into Ladakh and occupy it before

the Indians could send in reinforcements;

- Muslims in the western and southern regions of the state (near the Pakistani border) revolt

and provoke violent government reaction;

- tribal militias recruited in Pakistan's Pathan regions execute cross-border raids to lure the

Kashmiri forces to the border region, where they can be defeated in detail;

- the Pathan militias invade the Kashmir valley and Jammu, in order to support their fellow

Muslims suffering under Dogra oppression; militia forces also infiltrate deeper into

Kashmir, to interdict the Srinagar airfield and the far weather road from India to the

Jammu region, and thereby prevent or delay the arrival of Indian reinforcements.

- the Pathan raiders occupy Kashmirs capital, Srinagar;

- Pakistan dispatches regular forces to Kashmir, in order to restore order, and at the same

time discretely force the Maharaja to join his state to Pakistan.

The Pakistani planners expected to be able to create an irreversible fait accompli by the time

India could react, and at the same time deny Pakistans role in the events. They started to

execute the plan even before the official date of independence.10

The goal of the Maharaja of Kashmir was to play off India and Pakistan against each other

long enough and thereby retain Jammu and Kashmirs independence. If that was not possible,

his Plan B was to join India to Kashmir.

SEQUENCE OF EVENTS

Indian historiography divides the war into ten phases, which seems way too many for such a

brief and limited conflict.

August October 1947

In spite of the intentions of British, Indian and Pakistani politicians, Indias partition was

accompanied by serious violence. In the summer of 1947 riots broke out in the Punjab,

10 Pakistani sources are generally silent about this plan. According to the Pakistani version of events the

Pakistani government, the political leaders and the armed forces were only passive observers of the events albeit they sympathized with the Kashmiris. If Pakistanis played any active role, that was only due to individual initiative. The one significant exception is Muhammad Akbar Khan: Raiders in Kashmir, who discusses some parts of the plan.

-

12

Muslim refugees streamed into Pakistan, Sikhs and Hindus were fleeing to India.11 The

violence soon reached Jammu and Kashmir. The state forces did their best to maintain order

by suppressing both Hindu and Muslim violence, but whenever they tried to curb Muslims,

the press and the local Muslim politicians accused them of carrying out Hindu state terror

against a peaceful, innocent, defenceless religious minority. Pakistani propaganda accused the

Maharaja of planning the extermination or mass expulsion of the Muslim population. In

August open revolt broke out in Poonch and the first Muslim militia was raised.12 Attacks on

police stations and army garrisons became more frequent, and the organization of the Azad

Kashmir (Free Kashmir) government was begun.

In early September attacks from Pakistani territory commenced. Pathan groups of several

hundred men raided Hindu and Sikh villages along the border, then fled back to Pakistan

when government forces responded. The Pakistani Army supported the raiders with arms,

ammunition, communications equipment and transport, and its patrols entered Kashmiri

territory on several occasions. The Pakistani authorities feigned ignorance of the incidents and

of the role of the Army and at the same time kept accusing the Kashmiri government of

atrocities against the Muslim population.

By the middle of October the situation was ripe for a general offensive. The incidents were

becoming more serious along the 300 km long border, and they were occurring in

unpredictable locations at unpredictable times. The state forces could not protect every village

and every vulnerable point; they could only react to the attacks, but could not prevent them.

Their forces gradually became fragmented and they became incapable of concerted action.

Late October 1947 Pathan invasion

The general offensive started on two fronts on October 22, 1947 (See Figure 3.):

- Five Pathan lashkars (5 000 men) broke into the Kashmir valley from the direction of

Abbottabad. The Muslims serving in the Kashmiri state forces mutinied, killed their non-

Muslim fellow soldiers and officers and joined the Pathans or the local militias. The

attackers occupied Domel and on the 23rd they destroyed a state forces battalion, but near

11 Violent confrontation between India's religious communities is nothing new the English-language Indian

press even has special expressions for it: communalism and communal violence. However, the "communal violence" that accompanied Partition was far worse than anything seen before: a mass migration of 10 million people, and casualties approaching one million.

12 There were plenty of men who were familiar with weapons and had some combat experience: about 60 000 discharged veterans lived in Kashmir many of them Muslims.

-

13

Uri they met with stiff resistance: the state forces withstood their attacks for a while, then

destroyed the bridge over the Uri River and withdrew towards Baramulla.13

- The Azad militias attacking in the Jammu region were also met with stiff resistance, and

they achieved their objectives only after some serious fighting. They seized the border

towns (Bagh, Rawalkot, Rajauri, Beri Pattan) one after the other, surrounded Poonch and

cut the Poonch-Jammu road, but by the time they reached Jammu the Indian forces were

already on the move. Jammu remained in Indian hands and subsequently served as the base

of Indian operations in the south.

Soon after the attacks commenced (on 24 October), the Azad Kashmir government was

formed under the leadership of Mohamed Ibrahim.14 Henceforth two governments existed in

the state, each claiming full jurisdiction over the entire territory.

The operations in the south (in the Jammu region) were useful because they distracted the

defenders attention and forced him to split his forces. But the key to Kashmir was the

Kashmir valley and the key of the valley was Srinagar seizing the city was the most

important goal of the invasion. However, the men in the lashkars were warlike tribal militias,

not disciplined, regular forces. Their physical toughness, courage and fighting spirit cannot be

doubted, but obedience and carrying out orders without discussion were not their strong

points strategic foresight or an understanding of time and space factors even less so. Their

weakness lack of discipline became apparent in the operations around Uri.

For disciplined, well trained and well led troops the destroyed bridge over the Uri River

would have been a challenge, but not an obstacle to success: crossing the river without

vehicles was no problem, and the distance between Uri and Srinagar is somewhat over 100

km with light equipment a matter of two, or at most three days' forced march. However, the

lashkars refused to give up their vehicles (which they needed more for carrying their plunder,

than for transporting personnel), and thus they delayed the advance for nearly four days. As a

result of this delay they reached Baramulla (30 km from Srinagar) only on October 26. Once

they seized the town, the only force between them and Srinagar was a roadblock manned by

50 men of the state forces, five km east of Baramulla. The situation required a fast,

determined advance, before the state forces could react or receive reinforcements, but the

13 The fact that the Commander in Chief of the Kashmiri state forces, Brigadier Rajinder Singh, could collect

only 150 men for the defence of Uri, and he felt compelled to direct the defence himself, shows the desperate state of his forces. Brigadier Singh himself fell during the retreat from Uri.

14 This was actually a second attempt at creating a government: the first Azad Kashmir government had been formed on 4 October, as the revolt of the Muslims in the Poonch area was gathering strength. However, since this government was established in Pakistan (in Rawalpindi), it lacked credibility.

-

14

lashkars lack of discipline showed again. Instead of a fast and determined advance, they

indulged in looting and the massacre of Baramullas Sikh and Hindu population.

These delays gave the Maharaja time to make up his mind and appeal to India for assistance.

The Indian government was ready to provide it, but only on the condition that Kashmir

accedes to India. Accession duly took place on October 26, and Indian forces entered the

conflict the next day.15

October-November 1947 Relief of Srinagar and Indian counteroffensive

Moving sufficient Indian forces and their equipment into Kashmir over the difficult terrain, on

bad roads and weak bridges, in steadily worsening weather would have taken several months.

However, instead of months, there were only hours available. Obviously the forces had to be

flown in. The key to Kashmirs relief was therefore the Srinagar airfield, at an altitude of

1655 m, with a short, grass runway and primitive navigation equipment.

The first Indian troops to land were one rifle company and the battalion headquarters of the

1st Battalion, Sikh Regiment (1 Sikh), at 0930 on October 27. Instead of establishing a

defensive perimeter, constructing defensive positions and sending out careful probing patrols,

the battalion commander (Lt Col Dewan Ranjit Rai) left a small force at the airfield for

security, and immediately advanced in the direction of Baramulla. The company joined the

state troops at the roadblock and forced the advancing militia to halt, but could not hold the

position. It made a fighting withdrawal towards Srinagar and established a blocking position

on a commanding height 20 km from the city.16 This position held up the Pathans advance

for several days: they did not have the tactical skills necessary to assault dug-in infantry

supported by airstrikes, and due to the many marshes and lakes in the area, they could bypass

it only with great difficulty.

In the time thus gained, the Air Force flew in the remaining rifle companies of 1 Sikh, as well

as the other three battalions of the 161st Infantry Brigade, a machinegun company and an

artillery battery. As Indian strength increased, additional blocking positions were established

and strong patrols were sent out just in time to throw back a Pathan raiding force that did

nanage to bypass 1 Sikhs roadblock and advanced on the airfield from the southwest

(November 3 1947).

As Indian reinforcements (including an armoured car troop and a rifle troop of the 7th Indian

Light Cavalry) were coming into Srinagar by air from the Delhi area and by road from

Jammu, the commander of 161st Infantry Brigade (Brigadier Sen), extended the brigades 15 Pakistan has disputed the legality of accession ever since. 16 The company lost 24 men in the withdrawal, among them Lt Col Rai.

-

15

defensive perimeter to include the city of Srinagar, and planned to advance west and drive the

Pathans out of the Kashmir valley. Before the offensive could begin, the brigades defensive

positions were attacked by the massed Pathan militias (November 7 1947), and the Army of

Independent India fought its first real battle.

Figure 3. Operations in October-November 1947 (Drawn by the author)

The battle started with Pakistani militias attacking the Indian defensive positions manned by

the 1 Sikh and the 1st Battalion, Kumaon Regiment (1 Kumaon), and one company of 4

-

16

Kumaon in reserve. The defenders were seriously outnumbered, but their training, discipline

and leadership made up for lack of numbers. While the attackers were held by the fire of 1

Sikh, two armoured cars and the rifle troop of the 7th Indian Light Cavalry made a wide

turning movement (much of it through enemy-held territory). When they got into position

behind the attackers, 1 Kumaon made an unnoticed advance on the Pathans right flank. Thus,

when the coordinated attack of the armoured cars and 1 Kuamon went in, the attackers were

caught between three fires: Indian defensive positions to the front, machinegun fire from the

armoured cars to their rear, and a flanking attack. They withdrew hastily, leaving behind 700

dead and most of their vehicles, equipment, ammunition and supplies.17 (See Figures 3 and 4.)

The pursuing Indian forces recaptured Baramulla the next day, then Uri on the 13th. With the

recapture of Uri all Pakistani forces were forced out of the Kashmir valley.

Figure 4. Battle of Shalateng, November 7 1947. (Drawn by the author) 17 Sen, pp. 78-100.

-

17

After the recapture of Baramulla and Uri the Indian forces concentrated on clearing the

Jammu region.

- On November 16 the 50th Parachute Brigade advanced from Jammu towards the

northwest, in order to recapture the lost towns. This attempt was only partially successful:

the relief force reached Kotli on November 26, but it could hold the town only until it was

evacuated.

- A relief force reached Poonch from the direction of Uri on 25 November. It fought its way

into the city, but could not raise the siege. Poonch remained under siege for another year.

- Meanwhile Azad Kashmir forces captured Mirpur on November 25, looted it and

massacred its Hindu and Sikh population.

In the north the Pakistani forces were more successful. A local insurgent movement, the Jang-

i-Azadi Gilgit-Baltistan, carried out a quick revolution. Supported by the Gilgit Scouts (a

locally raised paramilitary force led by British officers) they declared the establishment of the

Gilgit Islamic Republic and elected a provisional government, which 14 days later gave up

independence and acceded to Pakistan. A task force consisting of Gilgit Scouts and local

militia occupied the Burzil Pass and commenced infiltration into Kashmirs Gurais region.

Another task force surrounded Skardu, the last government garrison in the Northern Areas.

December 1947 to April 1948 winter and spring offensives

As winter set in, the intensity of operations decreased. For the Indian forces the weather was a

serious problem: many soldiers saw snow for the first time in their life, they were not

accustomed to the cold weather at all, and there was not enough winter clothing and footwear

available (shortages were gradually eased by local purchases). The locally recruited Azad

militias and the Pathan fighters who were generally used to the weather of high mountains

were far less affected by winter conditions. In early December the Azad militias occupied

Janghar, but in January they lost Kot, and their attacks on Naoshera and Uri also failed.

The build-up of Indian forces continued during the winter, and by early spring there were five

brigades deployed in the state. In the March-April Indian offensive (Operation Vijay) in the

south three brigades (50th Parachute, 19th Infantry and 20th Infantry), supported by a light

armour squadron (A Squadron, Central India Horse) advanced along the Naoshera-Rajauri

road and recaptured Janghar (March 17 1948), then changed direction and occupied Rajauri

(April 12 1948). (See Figure 5.)

-

18

The siege of Poonch continued. The garrison (which had been designated 101st brigade) built

a short emergency airstrip, and after December 12 the Indian Air Force kept the defenders

supplied with munitions and provisions and evacuated the wounded. The capacity of the air

bridge was sufficient to fly in provisions for the 40 000 refugees trapped in the city as well.

Figure 5. Operations between December 1947 and April 1948. (Drawn by the author)

-

19

In the Northern Areas the militias commenced Operation Hammer (February, 1948), in order

to exploit their early success. Their objective was to take Skardu, then seize Kargil, occupy

the Zoji Pass, and finally seize Leh. At this time Leh's garrison consisted of a single rifle

platoon (33 men). It was reinforced only at the very last minute: in mid-February 1948 forty

volunteers (each carrying an extra rifle) crossed the Zoji Pass (a particularly difficult feat in

mid-winter), and joined the defenders. With the extra rifles they armed a locally raised militia,

and also built an emergency airstrip.18

The Pakistani commanders realized that the Indian forces, now in firm control of the Kashmir

valley, could exploit their central location to initiate offensives in several directions, and the

tribal militias would not be able to block them. Therefore they deployed a gradually

increasing proportion of the Pakistani Army in the threatened sectors. In the spring of 1948

regular army battalions, later entire brigades and artillery regiments participated in operations.

May to December 1948

In the spring of 1948 the Indian forces gradually became dominant in every sector. In early

May the steadily increasing forces were organised into two divisions: the units in the south

were subordinated to the Jammu and Kashmir Division and those in the Kashmir valley to the

Srinagar Division. The two divisions were subordinated to a temporary corps headquarters,

the Jammu and Kashmir Force.19

In the Kashmir valley Muzaffabarad was the objective of a two-pronged Indian advance. In

the attack in the north the 163rd Infantry brigade seized Tittwal (March 23 1948) and Keran,

but the southern attack by two brigades (161st Infantry and 77th Parachute) deploying from

Uri failed: the Pakistani government wanted to keep Muzaffabarad at any price, and deployed

two regular brigades (the 10th and the 101st) to support the militias in the area.20 At least five

more regular brigades were deployed between Muzaffabarad and Mirpur as reinforcements

for the Pathan and Azad militias.

The Indian forces made another attempt to relieve Poonch in June 1948. The 101st brigade

broke out of the city at the same time as the 19th Infantry Brigade advanced on the besiegers

from the direction of Rajauri. The attempt failed: the Indian forces could not break through

18 At 3300 meters altitude this was the world's highest airstrip at the time, and it was doubtful that the C47

Dakotas of the Indian Air Force would be able to land and take off at such altitude. To dispel the doubts the first C47 to land piloted by Colonel Mehar Singh, the commander of air operations. Major General Timayya, the commander of the Srinagar Division sat in the co-pilot's seat. (May 24 1948)

19 Subsequently the Jammu and Kashmir Division became the 26th Division, the Srinagar Division became the 19th Division, and the Jammu and Kashmir Force became the 5th Corps.

20 Khan, 1970. pp. 82-92.

-

20

the siege lines. The next attempt in October-November 1948 was a far more thoroughly

prepared operation by three infantry brigades, supported by an armoured squadron and

airstrikes. On October 13 1948 the 268th Infantry brigade delivered a diversionary attack

from the Naoshera area in the direction of Kotli, in order to secure the left flank of the main

attack. The 5th and 19th Infantry Brigades carried out the main attack between November 8

and 19 1948 from the Rajauri area, with the support of a light tank squadron of Central India

Horse. The 101st Brigade broke out of the city again, and on November established a

permanent linkup with the 19th Infantry Brigade. This ended the siege of Poonch (See Figure

6.).

In the Northern Areas the situation initially developed in a more promising manner for

Pakistan, but eventually the offensive there failed just as those in the Kashmir valley and in

Jammu. The Pakistani forces (primarily local militia) surrounded and besieged Skardu, Kargil

and Dras. They ambushed and destroyed the two Indian battalions despatched to relieve

Skardu (May 10 1948), then seized Kargil (May 22 1948) and Dras (June 11 1948). The

Skardu garrison held out in the old Kharpocho Fort for over six months and surrendered only after it ran out of food and ammunition. The besiegers massacred most of the defenders, as

well as the Hindu and Sikh civilians who had sought refuge in the fort.

When Skardu fell on August 14 1948, the last obstacle was removed from the way of an

offensive to take Leh. At this time the Leh garrison consisted of a company of regulars and

150-200 militiamen. Due to weather conditions the emergency airstrip was often closed, but

the Indian Air Force could always deliver sufficient munitions for the defenders to hold their

own, and in the last minute (August 23 1948) they managed to fly in a Gurkha battalion,

which beat back the Pakistani attack.

The first Indian attempt to retake Kargil and Dras and relieve the pressure on Leh (Operation

Duck, September 1948) was a failure. The entrance of the Zoji Pass21 that leads from the

Kashmir valley to the north was held in considerable strength by the Pakistani forces. The

terrain at the entrance of the pass favours the defender: there is no vegetation to conceal troop

movements, and the steep mountain sides reduce manoeuvre room to next to nothing. The

Pakistani defensive positions, carved into the steep mountain slopes, were impossible to hit

either from the air or by indirect fire from the ground, and they were impervious to the direct

fire of the attacking infantry. The gallantry of the Indian assault troops was not enough to

21 The Zoji Pass is a narrow, 3 km long corridor at an altitude of 3600 meters, squeezed on either side by

mountains of over 5000 meters.

-

21

overcome lack of cover and concealment, no manoeuvre room and the defenders interlocking

fields of fire.

To break through the pass, Major General Timayya had an armour squadron of the 7th Light

Cavalry brought up from the south. The squadron was moved from its deployment area in

Akhnur to the new attack's assembly area in Sonomarg (440 km) in secret. The turrets of the

tanks were dismounted and transported on trucks, under canvas. The convoy moved only at

Figure 6. Operations between May and December 1948. (Drawn by the author)

-

22

night, and when it arrived in Srinagar, the city was placed under curfew. These precautions

paid off: Pakistani intelligence remained unaware of the Indian preparations.

The appearance of the armoured squadron (November 1 1948) was a total surprise for the

Pakistani forces in the pass. At such altitude and in such difficult terrain they did not expect

tanks; they had made no preparations for anti-tank defence, had no antitank weapons, and

their training had not included field expedient anti-tank measures. The tanks were impervious

to Pakistani small arms and mortar fire, and the direct fire of their guns could finally destroy

the Pakistani bunkers that indirect fire artillery and air strikes had not been able to hit. The

tanks and their supporting infantry soon forced the Pakistani defenders out of the pass, and

continued to advance towards Dras and Kargil.22 On November 15 1948 they took Dras, and

on the 24th they linked up with the Gurkhas advancing from Leh. (Figures 6 and 7.)

Forcing the Zoji Pass, the recovery of Kargil and Dras and the relief of Leh was the war's last

significant series of combat operations. There were some subsequent efforts to improve

already occupied positions, but these actions had no significant effect on the conclusion of the

conflict.

January 1 1949 ceasefire

By the end of 1948 India's armed forces responded to the logistical challenge of long

distances, bad roads and rickety bridges, mobilized their significantly larger resources and

were ready to crush the Pakistani forces, and occupy Pakistani territory. Pakistani forces were

losing everywhere, and there were no resources in reserve, whose mobilization could have

turned the situation around. India was close to victory, yet in November 1948 the government

requested UN mediation to resolve the conflict.

After some political manoeuvres, lengthy negotiations and some last minute operations a

ceasefire came into effect on January 1, 1949 but the Kashmiri problem has remained

unresolved ever since. The belligerents retained their positions: the ceasefire line of January

1949 the Line of Control has become a de facto international border between India and

Pakistan. The two countries fought two more wars for the possession of Kashmir (in 1965 and

1999). To this day significant guerrilla activity has been going on, which according to

India's accusations Pakistan supports with arms, training, propaganda and money.

22 Major General Timayya was a firm believer in leading from the front: in the attack on the Pass he was

directing operations from the lead tank's turret.

-

23

Figure 7. Operations in the Northern Areas and in Ladakh. (Drawn by the author)

-

24

THE WAR'S BALANCE SHEET

Casualties

The war caused surprisingly few casualties at least as far as the Indian armed forces are

concerned: they lost 1 500 dead and 3 500 wounded (many of the latter were returned to their

units after recovery). There are no reliable data on the Pakistani losses, which is not

surprising: due to the nature of the Pakistani forces, there could have been no reliable record

keeping.

The Kashmiri civilian population sustained the heaviest losses. According to the accounts of

independent observes those of foreign (primarily British) citizens and journalists the

Pathan tribal militias treated the non-Muslim civilians with remarkable brutality (and they

were not particularly gentle with the Muslims, either). But instead of reliable data, there are

only estimates available on the numbers of victims.

Foreign Influence

At the time the events unfolded, the independence and sovereignty of the belligerents were

not yet complete. They depended on the former colonial power for economic progress, supply

of war materiel and diplomatic support. Furthermore, some of their highest decision making

and executive institutions were still directed by British civil servants, and the commanders of

their armed forces were all British officers. These civilians and soldiers protected and

promoted the momentary interests of the British Empire, instead of those of Pakistan or India.

Therefore neither the Indian, nor the Pakistani political elites could influence the outcome of

the war to the extent they wanted to.

The British government considered Pakistan more important for the long-term interest of

Great Britain, but wanted to avoid a war between former colonies right after their

independence. Therefore, the war's intensity had to be limited: militia raids and small border

clashes could be written off as the growing pains of independence, but they could not be

allowed to spread to other regions. The British officers and civil servants therefore had to

manoeuvre between neutrality and favouring one side or the other. They were so successful in

this, that outside Jammu and Kashmir there were hardly any holdups in the partition process:

Muslims continued to stream into Pakistani territory from India, and non-Muslims from

Pakistan to India. The transfer of Muslim units and individuals who selected Pakistani service

also continued in an orderly manner.23

23 It is worth noting that the sources discussing the Kashmiri events of 1947-48 whether they are Indian or

Pakistani accuse the British government and the British officers and civil servants of supporting the other side.

-

25

Land Forces

On both sides infantry played the dominant role. This was due to three principal factors: the

terrain, the inventory and the nature of the enemy. The rugged terrain (especially that outside

the Kashmir valley) restricted vehicle movement to a few bad roads. Most off-road movement

had to be carried out on foot, with the equipment either man-packed or on mules. Also, the

equipment available in the belligerents' inventories was nowhere near the scale of

contemporary European (much less American) forces: brigade-scale operations were routinely

supported by a few mountain howitzers and mortars, even for the better equipped Indian

forces. In any case, artillery was of limited utility against the Pathans who appeared

unexpectedly as ghosts among the rocks, and disappeared just as quickly. The Pathan and

Azad militias occasionally deployed a few mortars, and in the last months of the conflict

Pakistani artillery also appeared, but also on a very limited scale.

Artillery played a significant role in the defence of Poonch: in the early phase of the siege the

Indian Air Force flew in a light mountain battery, which kept the besiegers' mortars away

from the emergency airstrip. In larger engagements (the battle of Shalateng, the recapture of

Baramulla, the relief of Poonch) the artillery again played a significant role, but the number

and calibre of the available guns limited the effectiveness of their fire.

The Pakistani planners counted on quick success and did not expect the quick reaction of the

Indian armed forces; consequently they failed to prepare the militias to fight against armoured

forces, and failed to provide them with anti-tank weapons. As a result, armoured formations

could play a decisive role on three occasions (the battle of Shalateng, the relief of Poonch and

in the Zoji Pass), even though the forces were very small in every case, and their equipment

(Daimler armoured cars and M5 Stuart light tanks) were already obsolescent in 1947-48. The

experience gained in the war had a great influence on the development of Indian tactics in

later Indo-Pakistani wars.

Air Forces

From the very first day of the conflict to the very last the Indian Air Force was in complete

control of the air. As soon as the first Indian ground forces secured the Srinagar airfield,

Spitfire and Tempest fighters were flown in and commenced air operations, even though there

was hardly any aviation fuel available locally.24 Control of the air guaranteed air supply to

remote garrisons, as long as an airfield was available.

24 Sufficient fuel stocks were eventually built up, but initially the transport aircraft landing at the Srinagar airfield

had their tanks drained until they had only sufficient fuel left to return to India.

-

26

In addition to maintaining air supremacy, the fighters were also used for reconnaissance and

for ground support for the land forces (e.g. prior to the battle of Shalateng) although due to

the extreme dispersal of the Pakistani forces these functions were not nearly as useful as they

would have been in more conventional theatre. Indian control of the air hampered Pakistani

air reconnaissance and concentration of forces, and on the rare occasions when the aircraft of

the belligerents met in the air, the Indians always prevailed.

The air transport squadron (No. 12) played a particularly prominent role in the conflict. Its

pilots flew in nearly impossible weather conditions, undertook missions that promised certain

death they landed on airfields under enemy fire and lit only by the torches of local citizens.

Since the squadron's lift capacity (eight C47 Dakota aircraft) was not sufficient to support for

any length of time the forces deployed in Kashmir, the Air Force leased some 30 civilian

airliners.

The Indians also tried to compensate for their lack of bombers by using large explosive

devices rolled out of the doors of C47 transports. These did little or no damage (hardly any to

the enemy, at any rate), but they served as a morale booster to the Indian forces. Bomber

squadrons were organized late in 1948 (using refurbished American B17 bombers), but these

came too late to play a role in the war.

The above paragraphs are not intended to belittle the service and gallantry of the officers and

men of the Pakistani Air Force. However, it is a matter of record that Pakistan held back its

fledgling Air Force, partly for political reasons, in order to maintain the deniability of the

country's involvement in Kashmir, and perhaps partly to husband a scarce, but very valuable

resource.

Militias

The employment of militias was very advantageous for Pakistan. They could be deployed in

offensive operations when the combat readiness of the regular forces was still very low. Also,

the militias were quite expendable. Playing the roles of "freedom fighting forces

spontaneously organized by the local population" and "volunteers helping their Muslim

brothers suffering under Hindu oppression," the militias also concealed Pakistan's role or at

least made it deniable to an audience that was willing to be deceived. For every independent

observer, every Indian politician and every soldier it was obvious that Pakistan was

orchestrating the events, but "obvious" was not sufficient reason to start an international

conflict.

Since they had no doctrinal foundations and had little experience in the employment of

irregular forces, the Pakistani officers directing the operations had unrealistic expectations

-

27

about the endurance, discipline and combat readiness of the militias, and had to improvise

when the latter failed to perform as expected. Although the lashkars' lack of discipline

deprived Pakistan of success in the first operation (and thereby deprived it of victory),

Pakistan still managed to seize the strategically significant 1/3 of Jammu and Kashmir's

territory.

The Principles of War

Both the Indian and the Pakistani Armed forces were inheritors of British military traditions,

and their officers (most of them veterans of World War II), followed the contemporary British

principles of war.25 For the disciplined and well trained regular units of the Indian armed

forces the application of these principles was second nature. The case was different for the

Pakistani armed forces. Until regular Pakistani forces entered the conflict, the poor discipline

and limited combat capabilities of the Azad and tribal militias allowed only limited

application of the principles of war. In the following paragraphs only a few outstanding

examples of the principles' application will be discussed.

Selection and Maintenance of the aim. The objectives of the Azad Kashmir forces and tribal

militias were selected on the basis of sound reasoning force the Kashmiri state forces to

divide their strength, defeat them in detail, then make a quick dash for the capital and seize

the person of the ruler. Initially their operations were surprisingly successful. However, the

objective must also be within the capabilities of the available forces and this was not the

case. The bravery and fighting capabilities of the Pathans cannot be doubted, but the lashkars'

lack of discipline caused significant delays, and they did not achieve the most important

objective (Srinagar and the person of the Maharajah). After the failure at Srinagar the

objective changed: retain territory hitherto captured and occupy further territory in those

regions (e.g. in Ladakh) where the Indian forces were weak. In this they were partly

successful: although they could not retain the Kashmir valley, they did retain a narrow

crescent along the state's western border, and retained the Northern Areas.

The Indian armed forces especially considering the very short time available also selected

the first objective correctly: the key to Kashmir was Srinagar, and in the given situation the

key to Srinagar was the airfield. Achieving this objective proved to be well within the

capabilities of the Indian forces. Once Srinagar was secured, the correctness of the selection

and maintenance of further objectives was debatable. After Baramulla and Uri had been

25 The analytical framework for this analysis is the set of principles in general use in the British Empires forces

in the late 1940s, as they had been set down by Field Marshal Montgomery in 1946. Romilly: The principles of War in Todays World.

-

28

retaken, the next logical objective of the offensive would have been Muzaffabarad: the city

was the key to the valley of the Jhelum River, it was also the gateway through which the tribal

militias had invaded the Kashmir valley, and through which further invasion forces may

come. But instead of continuing with the already successful offensive, the Indian forces

changed the focus of their operations to the Jammu region, where they achieved only limited

success. In fairness to the Indian commanders, three widely separated fronts (the Kashmir

valley, the Jammu region and the Northern Areas/Ladakh) competed for their attention, and

they tried to answer the demands of every front.

Maintenance of the forces morale and combative spirit. After the passage of over six

decades it is difficult to assess how successfully this principle was applied, but the available

sources, as well as the progress of the operations indicate that combative spirit remained high

on both sides throughout the conflict. It is particularly noteworthy that for nearly a year and a

half the Pakistanis managed to keep in the field a large number of Pathan mountain tribesmen,

who were (and are) generally considered unreliable and unsuitable for long-term, high

intensity operations.

Offensive action. The belligerents continuously strove to exploit the advantage inherent in

possessing the initiative, and tried to achieve their goals primarily by offensive action. Forces

that were compelled to assume a defensive posture (e.g. the Poonch garrison) strove to

conduct active defence and kept the enemy off balance by constant patrolling and raiding

activity. When due to Indian superiority the Pakistani militias and regular units were

forced on the defensive by late 1948, they also employed the most active tactics, techniques

and procedures of active defence.

Surprise. In the initial phase of the conflict Pakistan achieved operational surprise with the

offensive in the direction of Srinagar, but due to the nature of the forces employed, could not

exploit the opportunity thus created. The tribal militias' tactics (raids, ambushes, guerrilla

warfare) often caused tactical surprise to the Indian forces, but due to the militias inadequate

training and light equipment, they could not aggregate their tactical successes into operational

success. Nevertheless, at the strategic and political levels of war the militias introduced a new

and unexpected uncertainty factor, which caused significant difficulties to the Indian political

leadership.

The Indian forces due to the availability of resources and to superior discipline had better

success in exploiting tactical and operational surprise. Two armoured cars unexpectedly

appearing behind the tribal militias decided the outcome of the battle of Shalateng which in

turn led to clearing the militias out of the Kashmir valley in a few days. The sudden

-

29

appearance of tanks in the Zoji Pass was a tactical surprise to which the Pakistani forces had

no response, and were compelled to withdraw from Ladakh the tactical surprise led to a

strategic success.

Concentration of forces. The Kashmiri state forces in reality more of a constabulary than an

army violated this principle as they responded to the series of raids initiated from Pakistani

territory. As they tried to defend an increasing number of threatened points, they were

operating in smaller and smaller units that had little or no contact and could not support each

other. This made them vulnerable to defeat in detail by the attackers.26

The Indian forces made the same mistake on the strategic level. After the relief of Srinagar

and the reoccupation of Baramulla and Uri they divided their forces in order to meet the

challenges of three widely separated fronts, as related above. As a consequence they failed to

achieve success in several operations, or achieved only limited results. At the tactical and

operational level concentration of the Indian forces was correct: the Indian commanders

would rather accept that some areas remained in enemy hands for some more months, but did

not divide their forces.

The Pakistanis concentrated sufficient forces for the attack on Srinagar, but after the failure of

that operation they had a constant problem with concentration. In the first place, the tribal

militias had their own ideas on how the war should be conducted, and seldom accepted advice

(much less commands) from Pakistani offices. Also, keeping the concentrated forces

adequately supplied would have required a reliably functioning logistical system something

Pakistan could not provide. Furthermore, the Indians' complete control of the air made

concentration a risky undertaking, as it provided desirable and vulnerable targets to air

strikes.

Economy of forces. For different reasons economy of forces was crucial for both sides. The

numerical strength, combat readiness and logistical capabilities of India's armed forces were

far superior to those of the just forming Pakistani armed forces. Nevertheless, the great

distances, bad roads and limited air transport capacity severely limited the size of the forces

that could be kept in the field for an extended period. Furthermore, India's forces were also

required in other theatres. Therefore, sufficient force but not one man more had to be

employed to execute every task, and there could be no idle units in the theatre. The events

showed that the Indian commanders generally applied this principle correctly.

26 In the 1971 Indo-Pakistani war India successfully employed the same tactics against the Pakistani forces

deployed in East Pakistan (Bangladesh).

-

30

Economy of force was even more important to Pakistan. The Pakistani forces were inferior to

their Indian counterparts in nearly every military metric, and the employment of the militias

was clearly a measure to husband scarce resources. With their guerrilla tactics and perhaps

even more important with their fierce reputation the Pathan tribal warriors tied down Indian

forces that were far out of proportion to their numbers. In addition, they were combat

experienced, yet cheap and expendable forces, and were available in large numbers at the

right time when the Pakistani forces were being created and needed every soldier to man the

regular units.

By the time operations were coming to a close in late 1948 the Pakistani officers had learned

to coordinate and harmonize the differing capabilities of regular and Azad militia battalions

and Pathan lashkars. When the various forces were organized into composite brigades, the

regular battalion would serve as a firm base of operations, protection for the other forces, and

a source of significant firepower. Around this base the Azad militia battalion, relying

primarily on its familiarity with the area of operations, would form a wide security belt.

Relying on these for support, the Pathans with their raids, ambushes and general

unpredictability, as well as their reputation could dominate areas far out of proportion to the

actual forces employed.27

Security. Both belligerents committed some serious mistakes, as well as achieved some

remarkable successes in protecting their forces from unexpected attack. The Pakistani forces,

especially in the early days of the conflict were particularly lax in matters of security, due to

the nature of the forces employed. A striking example of this is the movement of the 7th Light

Cavalrys two armoured cars and riflemen during the Shalateng battle. They had to march

several kilometres through enemy-held territory; the Pathans saw them and waved to them,

assuming them to be Pakistani forces, and realized their mistake only when the armoured cars

started firing into the rear of the Pakistani positions.

Perhaps the most obvious such Indian mistake, which affected not only the security of the

deployed forces, but also jeopardized the success of their operations, was the failure to occupy

the passes leading out of the Kashmir valley. No doubt, this would have required significant

forces (at least 3-4 battalions), whose maintenance at the end of long and tenuous supply lines

would have been a serious logistical challenge. On the other hand, the transfer of a squadron

of the Indian 7th Light Cavalry from Akhnur to Sonomarg was an especially noteworthy

success. The Indians moved the squadron 440 km to an assembly area near Sonomarg, and

27 Khan, Akbar, 1970. pp. 106-107

-

31

widened the road and reinforced the bridges from Sonomarg to the Zoji Pass all in complete

secrecy.

Flexibility. In this respect the Pakistani forces were at a disadvantage, especially in the early

phases of the conflict. The low tactical and operational capacity of the Azad Kashmir forces

and tribal militias limited the operations that could be carried out. They lacked the regular

forces cohesiveness, which allows a unit to keep up its morale and quickly to regain its

equilibrium after a reverse. However, to a certain extent this was counterbalanced by the

strong ideological support Islam provides its adherents; booty was a strong motivating factor

and the absence of regulations and doctrines allowed wide latitude for initiative,

experimentation and improvisation.

Due to their superior tactical and operational training, the Indian forces successfully employed

the concepts of the mobile defensive-offensive: they often occupied strong defensive positions

that the enemy could not bypass and had to attack from a disadvantageous posture. This way a

single rifle company of 1 Sikh held up the lashkars advancing from Baramulla towards

Srinagar. The Indian forces tactical superiority allowed them to switch from attack to defence

and from defence to attack (e.g. in the battle of Shalateng). The Pakistani forces, on the other

hand, employed defensive-offensive concepts with success only after regular forces begun to

take a more active role in operations (e.g. in the defence of Muzaffabarad).

The disciplined Indian regular forces did have sufficient cohesiveness to overcome their

reverses. Their commander learned from their failures and instead of giving up their

objectives, they would concentrate larger forces and more resources and would return after

some weeks or months, trying different methods and tactics, until they succeeded. On the

other hand, aside from a few outstanding achievements (e.g. breaking through the Zoji Pass),

the Indian commanders general lack of initiative led to a number of missed opportunities.

Sustainability. India inherited a tried and tested, well functioning war machine, and put all its

components including its logistical component to good use in the conflict. Pakistan's case

was somewhat different. Due to the heterogeneous nature of the forces, they had no

administration in the traditional, military sense of the word (i.e. regulations, forms, minutes,

chain of command, functioning logistical system, and all the rest). Nevertheless, for 14-15

months the Pathan lashkars, the Azad militias and the steadily growing regular forces were

supplied with munitions and subsistence, to some extent their casualties were also cared for,

and they not only gave a good account of themselves, but also managed to retain significant

areas when the ceasefire came into force.

-

32

Cooperation. The Indian forces operated on the basis of doctrines and regulations, and

applying the principle of cooperation was not a problem for them. For the heterogeneous

Pakistani forces the Pathan militias' wilful behaviour was initially a source of significant

problem, and an obstacle to the adequate application of cooperation. Their behaviour led to

the failure of the operation against Srinagar. In subsequent operations, as the Pathans

recognized the advantages of cooperation, their behaviour gradually changed, and those who

remained in the theatre until the end became quite reliable partners for the regular and Azad

forces.

A MILESTONE OF FOURTH GENERATION WARFARE

Interstate wars, fought by the regular forces of nation states have become rare events since the

end of World War II. Armed conflict between non-state belligerents and the states security

forces, generally fought within the borders of one state (insurgency, civil war) has become the

dominant form of warfare the age of asymmetric warfare has arrived.28 The first conflict

between India and Pakistan is one of the milestones, and Pakistan is one of the pioneers of

this process. Unlike subsequent asymmetric conflicts, non-state belligerents played the

decisive role only during the first few months of this war (between August 1947 and about

January 1948), then conventional forces and conventional tactics begun to dominate

operations, and the irregular forces gradually came under central control. Even so, the events

have shown that by employing the principles and tactics of asymmetric warfare, a modern

state can promote its interests against another, much more powerful state, and has a good

chance of achieving results far out of proportion to the resources it invests.

Pakistan evaluated the experiences of the Kashmir experiment as positive, and in its

subsequent wars has given an increasing role to non-state actors. It deployed them with

significant success in Afghanistan against the Soviet occupation forces, and against India. Its

regular forces were defeated in every war against India, but by employing non-state

belligerents it nevertheless managed to introduce a strategic and political uncertainty factor

into the relationship between the two countries that significantly reduced the difference in

strength between them. What Pakistan has been unable to achieve through its armed forces, it

28 The theory of generations in warfare was developed in the 1980s in the United States to explain this

phenomenon. According to this, developments in warfare constitute an evolutionary process, but in this process dialectical qualitative changes can be identified, which divide it into recognizable generations. The social and political changes in the 20th century, as well as the explosive developments in technology have brought about a new generational shift we are in the age of fourth generation warfare. (Strachan, 2007, Kiss, 2009, Somkuti, 2009)

-

33

has achieved by more or less open support to non-state belligerents: it has provided arms,

training and a safe haven to religious and ethnic minorities rebelling against Indias central

government. For sixty years it has successfully prevented the integration of Jammu and

Kashmir into India, and has continuously subverted the cohesion of the Republic of India.

In the 1960s India also deployed these tactics with considerable success against Pakistan

one result of this success was the Indian victory in the war in 1971 and the independence of

Bangladesh. Pakistans stability and cohesion has always been far more uncertain than those

of India, therefore India has far more opportunities to destabilize Pakistan, than the other way

around. However, based on purely political considerations (whose analysis is beyond the

scope of this essay) India has stopped supporting Pakistani resistance movements.

Cited sources