Kaushik Das Guptacdn.downtoearth.org.in/themes/DTE/images/wed2013_ebook.pdfContent Editor Kaushik...

Transcript of Kaushik Das Guptacdn.downtoearth.org.in/themes/DTE/images/wed2013_ebook.pdfContent Editor Kaushik...

Content Editor Kaushik Das Gupta

Design Chaitanya Chandan

Publisher Sunita Narain

Cover photo : An artist’s impression of an 18th century saltpetre factory,

courtesy Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, Civilizations, Macmillan, 2000

Unless indicated otherwise, Kaushik Das Gupta wrote the pieces

Down To EarthSociety for Environmental Communications41, Tughlakabad Institutional Area, New Delhi 110062

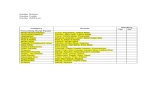

5 Evolution in times of climate change

7 Inundated by colonial misconceptions

11 Founded on piracy

15 The perfect brew

18 Pox Americana

21 A Swiss canton that banished cars

24 How Shell drums created music history

27 Parents' keepsake

30 Stub cut short

33 Ancient roots of a modern holiday

CONTENTS

Human interaction with the natural world is rarely inextricable

from their dealings in other arena. So, a piece of environmental

history of an age is also a window to understanding other aspects

of that era. For example, the US government's cavalier attitude to

copyrights matters during the early years of the country's

industrialisation shows a country intent on ripping off umbilical

relations with England. Or the Swiss canton Graubnden's banning

automobiles in the early 20th century betrays an early fear of the

car.

Such histories can also be subversive in revealing that much of

what we take as granted today had troubled pasts. To say that

urban people feared the car when it was launched, that the nation

that today creates paranoia over bio-terrorism wantonly

eliminated people through dreadul contagion centuries before the

word bio-terrorism was coined, or the nation advocating

copyrights most zealously today built its industries on piracy is to

question certitudes. Similarly, to show that many of India's laws

on forests—or other environmental matters—have a colonial past

is to drive home the urgency of laws in tune with local ecologies.

This is not to say that history is at the beck and call of

contemporary agendas, but to say that the past is present in much

of what we do today. Understanding it is critical to the way we

shape our agendas, including that for the environment.

So, on World Environment Day, we present some glimpses

from the past. They might help you contest some of the things

taken for granted today. Or, help you build connections with the

past. Or they might just make the past somewhat less distant—

and more enjoyable—territory.

THOSE WE TAKE FOR GRANTED

Natural Pasts | 5

Climate in South Africa abruptly turned warm and wet around 100,000

years ago. The humid weather lasted several hundred years. Such

humid spells would return to South Africa several times in the next

60,000, fostering cultural changes and technological innovation that bear

rudiments of modern behaviour, according to a new study.

The origins of some of the ways we communicate, relate to other human

beings as well as to nature lie in changes in climate, according to the study

published in the journal Nature Communications. Lead researcher, Martin

Ziegler, an earth science researcher at Cardiff University in Wales, told NBC

News, “the study is the first to link climate change in ancient times with

cultural and technological innovations.”

Ziegler and his colleagues analysed marine sediments off the coast of

South Africa to show that “South Africa experienced spells of warm climates,

when the Northern Hemisphere reeled under extremely wet conditions.” In

such times it acted as a “refugia for people from Sub-Saharan Africa,” says

Ziegler.

Ian Hall, professor at Cardiff University's School of Earth and Ocean

Sciences and one of the co-authors of the paper, says, “When the timing of

these warm and wet pulses was compared with the archaeological datasets, we

found remarkable coincidences. The occurrence of several major Middle

Stone Age industries co-incided with the onset of periods with increased

rainfall.” The humid conditions coincide with significant periods of human

AN

IRBA

N B

ORA

/ C

SE

Evolution in times of climate change

6 | Natural Pasts

advancement made about 71,500 years ago, and again between 64,000 and

59,000 years ago. During these times human beings made significant advances

in the production and use of stone tools and in the use of symbols, thought to

be essential for the development of complex language. These periods have

been linked with the first appearance of jewellery.

The Nature Communications paper could solve one of the mysteries of

human evolution. Archaeological data suggests that early human advances in

technology moved in fits and starts. Scientists and historians are sometimes

clueless when confronted with advances in stone technology in Sub-Saharan

Africa around 90,000 years ago and their near disappearance a few thousand

years later. “Scientists have offered many suggestions as to why these cultural

explosions occurred where and when they did, including new mutations

leading to better brains, advances in language, and expansions into new

environments that required new technologies to survive. The problem is that

none of these explanations can fully account for the appearance of modern

human behavior at different times in different places, or its temporary

disappearance in sub-Saharan Africa," according Stephen Shennan who heads

UCL's department of archaeology.

"There is a very good fit between rapid climate change and the occurrence

and disappearance of these first evidences of modern behavior in early

humans," believes Ziegler. It's well possible that people from Sub-Saharan

Africa migrated to South Africa, bringing their advanced tool-making

technology.

Chris Stringer, an authority on human origins at London's Natural History

Museum and one of the co-authors of the study, suggests that as population

density increased in South Africa, people networked, shared ideas and

innovations.The new findings, he told NBC, fit well with the idea that

population density breeds cultural innovation.

"Those dense populations form networks over the landscape which are no

longer huge patches of arid land that they cannot cross," he said. Tool-making

technology is not the only indicator of cultural efflorscence. Messages written

in ochre, a type of pigment, indicate an advancement in communications,

according to Stringer. Remains of seashell jewellery that are dated to the times

of wet weather are perhaps an indicator of social rank, according to historians.

Floods have ravaged India from times immemorial and people have

controlled and turned them into beneficial processes. But today they

are seen as catastrophic events that are to be forcefully contained by

dams and embankments.

This perception has its roots in India's colonial past, according to recent

evidence from Orissa. Floods, famines and crop failures were thought to be

merely phenomena that occurred because of the unpredictable vagaries of

nature. This whimsy then had to be overcome, if the most pressing objective-

collecting the maximising revenue possible-was to be. But this short-term

objective and misconception about the role of floods created havoc among the

peasantry. Unfortunately, imperceptions about floods have not changed much

since the colonial period.

Coastal Orissa, consisting of the districts of Cuttack, Puri and Balasore,

came under colonial rule in 1803, but it took till 1834 to set the first definite

guidelines for revenue collection. From 1836 and 1843 the entire province was

surveyed and mapped at the cost of Rs 20,36,348, but the revenue increased by

only Rs 34,680.

In the process of surveying, the colonial administration come to grips with

a unique ecological setting. Andrew Stirling, an administrator-geographer,

Natural Pasts | 7

Inundated by colonial misconceptions■ ROHAN D’SOUZA

8 | Natural Pasts

wrote in his book An Account, Geographical, Statistical and Historical, of

Orissa Proper, or Cuttack published in 1822, that a striking characteristic of

the coastal tract was its river system, which was "peculiarly subject to

inundation".

This river system consists of the Mahanadi, the Brahmani and the

Baitarani, which drain into the Bay of Bengal. They often shifted course,

overflowed and inundated villages and fields. Besides, the water torrents with

their silt load destroyed or altered the topography of the land.

The frequent changes in the river system evoked a tremendous sense of

chaos in the colonial mind. The ever-changing character of this unique deltaic

region subverted the continuity of British rule and disrupted its solidity.

Remissions of revenue on account of floods between 1852 and 1867 amounted

to L26, 472 per year, a substantial 16 per cent of the land tax collected in

Orissa. Panicked British policy makers, obsessed with revenue collection and

profit, began looking for solutions.

By the 1850s, new strategy, based on engineering solutions to prevent

rivers from overflowing their banks, emerged. The new approach differed from

the earlier thinking that consisted of approximating the costs incurred from

flood damage and correspondingly remitting tax amounts as relief. Flood

waters were now to be "controlled", "regulated" or "brought under absolute

subjection".

Detailed studyIn 1856, J C Harris, the executive engineer of Cuttack conducted a detailed

study of the Mahanadi and its tributaries. Harris argued that the floods in the

Mahanadi delta were caused by the incapacity of the river to carry its silt load.

As a remedy he suggested that a spur be constructed at Naraje to divert water

away from the river Kathjuri, a tributary of the Mahanadi, to increase the

latter's flow, enabling it to clear the silt load and retain the water within its

banks.This study led the administration to develop systematic and scientific

monitoring of the river system of coastal Orissa. Seveal stations were

established to measure the depthsof the rivers and their water speed.

Irrigation engineer Arthur Cotton, after touring Orissa in 1858, suggested

investments in a more comprehensive programme to regular rivers through a

system of weirs, embankments and canals. Cotton linked flood and drought to

the loss of revenue and his solution lay in transforming these losses into profits

through "Western knowledge and technology". Active intervention through

technological fixes, as opposed to a remission-centric policy, became the new

focus in flood policies.

However, despite this apparent shift in the policy of dealing with floods,

there was a remarkable continuity. From 1803 to the Report of the Orissa

Flood Committee 1928, the discussion on floods was centred on the event as

opposed to the process.

There were, nevertheless, some perceptive officials who saw the floods as

essentially beneficial to the delta. "Indeed, a heavy flood, however severe and

long continued it may be, seems always to contain in itself an element of future

compensation for present loss by the increased fertility," said British historian

G Toynbee.

Floods were seen as s blessing in disguise as the destruction of one season

was compensated by the unusual abundance of the next. But the British

revenue system was rigid in its demands. Instalments were collected in

November and April regardless of the circumstance. A flexible revenue system,

like of the Maratha regime (1751-1803)-synchronised with the ruthless policy

of forcing cultivators to pay on fixed dates.

Canals constructedTo prevent floods from occurring, the colonial government adopted Cotton's

scheme. In 1863, a system of weirs and canals began to be constructed by the

East India Irrigation Company (EIIC). Popularly known as the Orissa scheme,

these canals were supposed to irrigate area of nearly 1 million ha and yield a

21 per cent return on investments of L200, 000 made by private British

speculators who bought EIIC shares.

The Orissa scheme proved to be a colossal failure and EIIC did not recover

its costs. In 1866, the first irrigation lease was signed for an area of only 1.4 ha.

At the end of February 1887, the area irrigated was just 2,702 ha at a time when

there was sufficient water to irrigate 24,291 ha. At the end of October 1867,

EIIC was prepared to supply water for 61,943 ha but the area under irrigation

was only 3,982 ha. There was a complete mismatch of demand and

supply.Since the peasantry could not pay the land revenue, the British revenue

department failed to make profits. The entire gross revenue from the

Natural Pasts | 9

10 | Natural Pasts

commencement of the project amounted to a measly Rs 4,339.

There were other adverse consequences. By sealing rivers within their

banks, cultivators were denied access to the rich deposits of fertilising silt.

Floods continued to ravage the land. The unplanned construction of

embankments interfered with natural drainage lines, diverted water currents

to previously unaffected areas and thus complicated flood levels.

In 1904, the colonial government finally realised the inefficiency of

maintaining these embankments, it not only washed its hands off the problem

but secretly set about dismantling some of these embankments. Seventy years

after Cotton published his "scientific" study, the flood committee of 1928

wrote, "Orissa is a deltaic country and in such a country floods are inevitable.

They are nature's method of creating new land and it is useless to attempt to

thwart her in her working." Little heed was paid to this wisdom.

The policy of containing floods still continues. Orissa remains one of the

most flood-prone areas in India, her sad experience with flood control

somehow forgotten as history continues to repeat itself.

Natural Pasts | 11

In the last decades of the 18th century, a garrulous North American was a

conspicuous presence in the working class colonies of Manchester,

England. He also frequented working class localities in other parts of

England, and in Ireland. This was Thomas Atwood Digges, the scion of a

wealthy family in Maryland, USA, and a thwarted novelist. But Digges was not

in England in search of any literary pursuit. He was a spy on the look out for

designs of new machines that inventors in early industrial England were

producing. Much of early American industrialisation owed itself to the efforts

of industrial spies such as Digges. According to historian Doron Ben Atar,

"Copyright violations and outright economic espionage were key elements in

the political and economic life of newly-independent US."

The founding fathers of the country realised that economic self-sufficiency

Founded on piracy

12 | Natural Pasts

was essential to ensure the political independence of the young republic.

Besides, while in the 17th and even the early-18th centuries, Britain shared

technological innovations selectively with its American colonies, it became less

willing to do so once the colonies asserted their independence. Exporting

industrial equipment from Britain's textile, leather, metal, glass and clock-

making industries was prohibited in the 1780s. The New World responded

with technology piracy. James Watt's steam engine was among the first to be

copied. According to Ben Atar, the steamboats of John Fitch and James

Rumsey used the technique employed by Watt's more famous steam engine. In

1787, Rumsey obtained a patent from the state of Virginia for steam

navigation. Many followed in Fitch's and Rumsey's footsteps. Among them

was Samuel Compton, whose spinning frame -- The Mule -- combined the

techniques used by Richard Arkwright's famous weaving machine and James

Hargreaves' Spinning Jenny.

But while spies like Digges could get copies of industrial designs or

sometimes machines -- dismantled in Europe, only to be put back in the US -

- there was a paucity of skilled hands to work the gadgets. So, European

artisans had to be lured into emmigrating to the US. Once such incentive was

giving "winners lottery tickets" to artisans -- the draws were rigged in favour

of the immigrants. The artisans were also given gifts of land -- though the

authorities took care to ensure that it was not used for agriculture.

England retaliated hard. In the late 1770s, the country's parliament ruled

that all people leaving for the North American colonies from the British Isles,

with intent to settle there, were required to pay 50. Besides, a 200 fine,

forfeiture of equipment and a year in prison were laid down for those caught

attempting to export industrial machinery. This did not deter spies such as

Digges. An anti-emigration pamphlet, published in London in the mid-1790s,

declared that "there are plenty of agents hovering like birds of prey on the

banks of the Thames, eager in their search for such artisans, mechanics,

husbandmen and labourers, as are inclinable to direct their course to

America."

Digges recruit The American novelist's most famous recruit was William

Pearce, a mechanic from Yorkshire who had settled in Belfast, Ireland. The wily

Marylander claimed, "Pearce that was a second Archimedes and was the

inventor of Richard Arkwright's famous spinning and weaving machinery, but

Natural Pasts | 13

had been robbed of his invention by Arkwright." After Pearce failed to get

premiums from the Irish parliament in recognition of his mechanical

innovations, he warmed up to Digges' overtures and agreed to emmigrate to

the US. In 1795, Digges proudly reported to Secretary of State, Thomas

Jefferson, that "a box containing the materials and specifications for a new

invented double loom" was about to depart for American shores. "Pearce and

two of his able assistants would follow, they reconstruct the machinery and

put it to work," he added with much elation.

Digges had his fair share of critics. Many argued that he had blotted his

record by working as a double agent during the American War of

Independence. But supporters of this novelist-turned industrial spy included

George Washington. The first American president declared that Digges' critics

"should look no further than his activity and zeal (with considerable risk) in

sending artisans and machines of public utility to this country."

Hamilton's report Another Digges supporter was Alexander Hamilton. In 1791, this secretary of

treasury submitted the seminal Report on Manufactures to the American

Congress. The report had a section on aggressive technology piracy. Hamilton

proposed a federally-orchestrated programme, aimed at acquiring the

industrial secrets of rival nations. "Most manufacturing nations," Hamilton

explained, "Prohibit, under severe penalties, the exportation of implements

and machines which they have either invented or improved." "The US

government," he argued, "Must circumvent the efforts of these industrially

advanced nations by offering inducements and developing opportunities for

employment."

Digges was delighted at the endorsement of his methods. He had 1,000

copies of Hamilton's report printed in Dublin in 1792 and spread among the

manufacturing societies of Britain and Ireland. He believed the report would

"induce artists to move toward a country so likely to very soon give them

ample employ and domestic ease".

Hamilton's report also spawned the Society for Establishing Useful

Manufactures, a New Jersey-based outfit created "to procure from Europe

skilful workmen, and such machines and implements as cannot be had here in

sufficient perfection." Ben Atar calls this society the most ambitious economic

14 | Natural Pasts

enterprise of the early republic. By 1794 it had built Paterson, a British-model

industrial centre, on the banks of the Passaic river in New Jersey. "The entire

project was founded on pirated knowledge," says Ben Atar.

A patent regime But how long could the young republic flout international copyright

conventions? US federal acts of 1790 and 1793 forbade patents on

importation. "After all," says Ben Atar, "A self-respecting government eager to

join the international community could not flaunt its violation of the laws of

other countries." But though federal officials disavowed any connection to the

theft of knowledge, piracy continued well into the 19th century. William

Thornton, the first superintendent of patents, who ran the office almost

single-handedly from 1802 to 1828, did not even insist that patentees take the

required oath that their application was original. Ben Atar contends, "It is

entirely possible that most of the applications received by the patent office

during the first few decades of national independence were for devices already

in use, elsewhere."

Francis Cabot Lowell Let us see another example. In 1810, an American businessman, Francis Cabot

Lowell, travelled to Great Britain for what he claimed was a tour of the English

countryside. Along the way, he quietly visited the mill towns -- Manchester

and Edinburgh -- that had become the heart of England's booming textile

industry, thanks to Edmund Cartwright's loom -- one of the first great

inventions of the industrial revolution. Although the textile factories were off

limits to foreigners, Lowell talked his way in and memorised the loom's design.

Back home, he had a version built, and made it the centerpiece of what was to

become the booming industrial township of Massachusetts.

At the close of the 18th century, the US comprised underdeveloped and

badly-connected agricultural settlements. It was transformed into an

industrial superpower in the next 75 years. Technology piracy played a very

important role in the success. It's another matter that the US flaunts a holier

than thou attitude on patents today.

Natural Pasts | 15

The last week of April is usually party time in many parts of Germany.

Beer halls in Munich are packed with people drinking tall glasses of

dark brew served by women dressed in dirndls, while men in leather

shorts pump out oompah music from battered brass instruments. The

government of Bavaria sometimes declares a Beer Week to let tourists and

residents sample from some of the state’s 40 breweries and 4,000 brands. The

Germans toast the anniversary of an edict issued nearly 500 years ago at the

small town of Ingolstadt, some 30 km north of Munich.

On April 23, 1516 Bavarian co-rulers Wilhelm IV and Ludwig summoned

a meeting of the Bavarian estate assembly. It was a noisy affair. The beer loving

dukes had their eyes set on the perfect brew. By the end of the day they had

stamped their seal on what is regarded as the world’s oldest food purity law:

Reinheitstgebot or the Beer Purity Law.

The perfect brew

16 | Natural Pasts

The decree stipulated that only barley, hops, and water could be used to

make the brew. Yeast had not yet been discovered. The intent of the feudal

decree was to keep cheap—and often unhealthy ingredients—such as rushes,

roots and a variety of fungi out of the German people’s favourite drink. Some

of these herbs were downright poisonous, others induced hallucinations.

Monasteries and households were as culpable as feudal manors. But this

was not always so. Beer became a staple monastic drink in the 9th century

when trade with Western Europe came to a halt. Deprived of wine supplies

from France, the monks took to beer. They experimented with new techniques

and ingredients and in the process, discovered the virtues of hops: the flower,

a distant relative of cannabis, gave the liquor its bitter taste and also helped

preserve it.

The Benedictine abbess Hildegard von Bingen’s 12th century treatise

Physica sacra, contains the first written description of the healthful effects of

hops in beer. Hildegard drank beer regularly and lived to be 81 years old, an

incredible age for that time. Monastic rules framed by immigrant Irish priest,

St Columban, regulated the consumption of the drink: drunkenness was

forbidden and the monk who spilled beer had to stand still for an entire night.

But the food, drink and shelter the monks shared with dusty travellers

soon became a commodity. Observance of ascetic rules began to take a back

seat to the chores of providing for the itinerant customers. After a day of hard

work in the monasteries’ fields, kitchens and breweries, many a monk found

more solace in the merry company of his guests than in the austere regimen

prescribed by an Irishman.

The monks began looking for newer elements of intoxication. And

travelers took the knowledge home. The brew very often went wrong. The

failure was usually blamed on women who brewed beer in households.

Thousands of beer witches were burnt at the stake between the 14th and 16th

centuries.

How could the feudal estates stay away from such frenzy? Control of

breweries was one of the ways for a feudal lord to assert his authority. Many

were keen to innovate as well. But none was as obsessed with the perfect brew

as Wilhelm IV: his Tobbaco Council spent hours discussing beer everyday.

The Bavarian duke’s 1516 purity decree was not accepted instantly. The

Protestant reformer Martin Luther who lived around the same time preferred

Natural Pasts | 17

the earthy brew of Northern Germany to the regulated Bavarian variety.

But the Reinheitsgebot did spread northwards to other German states

and by 1919 it had become the official law in all of the realm of the German

Kaiser, with the addition of yeast as a basic ingredient and malted wheat as

an allowable component in top-fermented beers.

But non-German brewers regarded the Reinheitsgebot as an impediment

to free trade. In 1987, the European Court struck down the 1516 edict. Even

now, however, a German beer brand is sure to carry either of the messages:

Gebraut nach dem deutschen Reinheitsgebot or Gebraut nach dem

Bayerischen Reinheitsgebot von 1516 (brewed according to the German Purity

Law or the Bavarian Purity Law of 1516).

Commemorating the 16th century edict began the year it was struck

down.

18 | Natural Pasts

In late 2003 and early 2004 US authorities went on a massive search for

blankets in the plains around the Great Lakes in North America. These

were not ordinary blankets. They were bison skins that were smeared with

body fluid tainted with smallpox and used, two hundred years ago, to

obliterate American Indians. Post 9/11, US authorities feared that some such

blankets might still exist, and a viable source of smallpox might fall into wrong

hands. Many areas in the US and Canada have been cordoned off. The search

did not yield much, but it brought to the fore some sordid pages from

American history.

Pontiac's rebellion Many historians trace the notorious blankets to a

gruesome episode in American history during the spring of 1763. That year, a

party of Delaware Indians, led by their Ottawa chief Pontiac, laid siege on the

British-owned Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Captain Simeon

Ecuyer, a Swiss mercenary and the fort's senior officer, saved the day for the

British. The Indians agreed to temporarily abandon their siege in return of a

gift of two blankets and a handkerchief. They had no inkling that the wily

Ecuyer had deliberately infected the presents with smallpox contagion.

This episode is confirmed by William Trent -- the leader of the militia of

European settlers at Fort Pitt -- in his journal. Most historians regard this

source as the "most detailed contemporary account of the anxious days and

nights in the beleagured fort." Trent notes in an entry dated May 24, 1763, "I

hope the means have the desired effects." They indeed had. By July 17,

Pox Americana■ PRANAY LAL

Natural Pasts | 19

smallpox had become endemic among the Delaware Indians.

Another villain in this piece is Lord Jeffrey Amherst, the commander of

British forces in North America during the final battles of the French and

Indian wars (1756-1763). The general's correspondence shows that he entered

into tacit collaboration with his bitter colonial rival, the French, to further the

dubious methods initiated by Ecuyer. In his book, The Conspiracy of Pontiac

and the Indian War after the Conquest of Canada (Boston: Little Brown,

1886), historian Francis Parkman notes that Amherst and a French general

Henry Bouquet exchanged regular letters about spreading "smallpox mong the

disaffected tribes of Indians."

Bouquet was aware of Ecuyer's method. In a letter dated June 23, 1763, he

notes that smallpox had broken out among Indians at Fort Pitt. And on July

13, 1763, he suggests "the distribution of smallpox smeared blankets to

innoculate the Indians." Amherst approves of the method in a letter dated July

16, 1763 and also queries his French interlocutor about other methods, "To

extirpate this execrable race."

Bouquet and Amherst also discuss the use of dogs to hunt down Indians,

called the "Spanish method". But this method could not be put into practice,

because there were not enough dogs.

Amherst had been at war with the French as much as with the Indians, but

he was not driven by any obsessive desire to extirpate them from the face of

the earth. The French were apparently a "worthy" enemy. But the general had

no scruples about methods when it came to Indians. His letters abound with

phrases such as, "That vermine (sic) have forfeited all claims to the rights of

humanity." The historian J C Long, records the general as saying, "I would be

happy for the provinces [Pittsburg] if there was not an Indian settlement

within a thousand miles of them." Other historians have noted that Amherst

derived almost sadist pleasure in listening to accounts of spies and others who

reported smallpox in Indian settlements.

Who knows and who does not European colonialists like Amherst and Bouquet could go on with

exterminating Indians using the notorious blankets because they themselves

were armed with the knowledge of inoculation. The process was discovered by

a Dutch physiologist Jan Ingenhaus and was brought to England in 1721 by

20 | Natural Pasts

one Lady Mary Wortly Montague. It involved inoculating healthy people with

pus from the pustules of those who had a mild case of the disease, but this

often had fatal results.

But colonialists like Amherst did not have to wait for long. By the closing

decades of the eighteenth century, they could carry on with their methods with

even greater impunity. By that time, British physician Edward Jenner's

reserarch on the relation between cowpox and smallpox had begun to yield

decisive results. And in 1796, Jenner reported that humans could be vaccinated

against smallpox if a small dose of cowpox could be administered to them.

Such knowledge was of course kept away from indigenous people in the

colonies. And colonialists like Amherst continued to exploit the divide of who

knew and who didn't.

This divide persists. Today, the West remains in mortal fear of strange new

diseases that originate in Asia (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, or sars;

avian influenza) and Africa (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome or aids,

Ebola and monkeypox). But almost all vaccination measures are designed to

protect citizens of the developed world. There is very little effort to protect

those who face the greatest risk from violent diseases. For example,

discontinuation of smallpox vaccination in Africa has exposed many in the

continent to other related infections, like the monkeypox.

The threats of bioterrorism are real and relevant. But the real challenge is

to protect those who who actually live with mysterious diseases. However,

developed societies continue to live with the Amherst syndrome.

Natural Pasts | 21

Car dependency may now have become a serious problem, but in 1882,

when the German car maker Karl Benz took out his rudimentary

internal combustion engine for a test drive in the streets of Stuttgart,

he was arrested. The French count Albert de Dion fared no better. When he

tried to produce his steam automobile commercially, his father got a court to

restrain him.

But by the beginning of the 20th century, de Dion and his partner George

Bouton had become car barons. So had Benz. Newspaper reports in Europe

and America glowed with enthusiasm about the car. The first issue of the

American automobile magazine, Horseless Age, waxed eloquent: "The

growing needs of civilization demand it. The public believe in it."

Actually, not everybody started believing in the car even then. People of

the Swiss canton Graubnden were among the sceptics. On August 24, 1900, the

government of Graubnden banned all automobiles from all its roads "to turn

the canton into a peaceful oasis where everybody will be safe from the

A Swiss canton that banished cars

22 | Natural Pasts

automobile's nuisances". A year later the canton of Uri imposed a similar ban.

The ban sparked off a propaganda war, featuring pamphlets and polemics.

Apologists for motorisation harped on the difficulties posed by horses,

exaggerating the stink of horse manure and swarms of flies. Those opposed

included saddlers, coachmen, nature lovers as well as people along the main

roads. They were scared of accidents, dust, noise and smell, and most

importantly, apprehended ouster from the roads.

Antipathy against the car prevailed in many other parts of Europe and

America. According to historian Katie Alvord, "Not only were the poor

publicly reminded of their poverty when motorists drove by but cars began

eating what little they had: public spaces." In many places, resentment against

car owners inspired stone-throwing episodes. In 1904, this became so rampant

in New York neighbourhoods that the police had to be pressed into action.

Two years later, the then US president Woodrow Wilson expressed the concern

that cars allowed their owners to display their wealth so ostentatiously that

people would be driven to socialism.

In other places the car became associated with national pride. Just before

World War I, the German Riechstag saw the car as a symbol of national

resurgence. "The progress of our industry and nation depends on

automobilism," wrote a German paper.

The term automobolism was, in fact, made popular by the Austrian anti-

automobile campaigner Michael Freiher von Pidol. In a 1912 pamphlet, he

wrote, "Where does the motorist get the right to master, as he boasts, the

street? It no way belongs to him, but to the population as a whole.

Automobile traffic involves the constant endangerment of passers-by or

other vehicles, as well as a severe infringement of community relations that

correspond to an advanced culture." The pamphlet noted 438 car accidents

with 16 deaths in Vienna in the first half of 1912. Seven children were

killed in the latter half of the year von Pidol wrote.

In Graubnden, the car ban withstood nine referendums. But by 1919, the

ban was relaxed to allow public transport to ply. Actually the Swiss PostBus.

Started by the Swiss Postal Service in 1906, the bus initially linked capital

Berne to the family-vacation town of Detligen. Beneath heavy sacks of mail

lashed onto the roof of their omnibus, a dozen or so passengers sitting on hard

wooden benches paid modest fares to take the hour-and-a-quarter commute

Natural Pasts | 23

over 10 km.

But it took very little time for the bus service to establish itself, and the

bright yellow PostBus was a much loved feature of life in other parts of

Switzerland by the time it was introduced in Graubnden.

After the war, hundreds of military trucks were converted for the

conveyance of goods and people by the bus company. The ban on private

motor cars too came to an end in the Swiss canton in 1921.

PostBus retains its popularity in Switzerland. In the early 1940s, engineers

endowed the buses with the face of a good-natured St. Bernard--with the

slanted black radiator grill recalling a dog's muzzle and the separated, gently

downward-bent windshield its big faithful eyes. Even later, as the so-called

"muzzled Postbuses" gradually disappeared, the buses manufactured by the

Swiss company, Sauer, continued to adhere to this friendly-face principle.

The new flat radiator grill of the bus resembled a mouth, the Sauer

emblem with its chrome mouldings a moustache and the fresh-air inlets at the

front a set of expectantly raised eyebrows.

24 | Natural Pasts

In the summer of 2007, Shell officials at the Caribbean island of Trinidad

and Tobago were in a spot of bother. Business was fine for the oil company

and environmentalists and other usual gadflies weren't making much

noise. But the Shell factory in Barracones Bay was confronted with an

awkward demand musicians planning to play at the cricket world cup wanted

oil barrels. The oil company wasn't caught unawares though it had faced a

similar demand a year earlier, during the football world cup. Barracones Bay

honchos had learnt an important lesson in Trinidadian culture then about

steelpans. Crafted from oil drums, their lilting melodies were as essential to

spectator sport--indeed all celebration--in the West Indies as rum and

dancing.

Many Shell officials denied the association."Our drums are disposed of

properly, and Shell's health and safety rules prevent the use of empty drums

for anything but Shell oil products," William Rosales, the manufacturing

engineer at Trinidad's factory told www.caribbeannewsnow.com. Shell wasn't

always this uncomfortable with musicians beating its oil barrels. In the 1950s,

the company put one of the early innovators of the steelpan, Elie Mannette, on

its payroll. This was to stop him and his friends, Birdie Puddin and Cobo Jack,

from stealing Shell's empty and toxic oil drums.

Out of Africa, into a Shell Steelpan music has its roots in the tradition of

drumming that enslaved people brought with them from West Africa. Trinidad

became a British colony in 1797; the British feared the drums would foment

revolt by transmitting coded messages from one sugarcane plantation to

another. Besides, the Anglican Church wanted to dissolve African religions and

cultures. So drums were banned, and descendants of slaves were forbidden to

practice their religion or to speak their own language.

Winston Spree SimonNot to be denied expression of their traditional rhythms, they crafted

makeshift drums from hollow bamboo. In the 1930s, Trinidadian bands began

How Shell drums created music history

Natural Pasts | 25

to incorporate metal objects like garbage can lids, pots and pans and biscuit

tins because these objects were louder and more durable than bamboo.

Legend has it that in 1942, a 12-year-old boy Winston Spree Simon lent his

metal drum to a friend. When it was returned it had been beaten into a

concave shape and had lost its special tone. Hammering the drum back to

shape, Simon noticed the pounding created different pitches or notes. He went

on to create four distinct notes on his drum and could now play melody

instead of percussion. The steelpan was born.

Many historians doubt this story. But there is no disputing that Simon was

an early pioneer of the melodic steel drum. In 1946 he developed the 14-note

pan using old drums left behind by the British navy that had made Trinidad

its base during World War II.

This was also the time when Shell set up shop in Trinidad. For Simon's

friend Mannette, this was a heaven send. He hammered discarded oil drums to

produce an instrument capable of playing sophisticated melodies. Modern

pan makers rigorously follow Mannette's system in crafting any of the nine

drums that make up the steelpan family. The barrels are first sliced according

to register, from soprano to bass. Then, using a selection of rubber and metal

mallets, blenders stretch the thickness of the metal top to create a concave

drumhead capable of producing anywhere from three to 30 notes. In Trinidad,

a steelpan costs about US $600. And should they carry the Shell sticker--which

the company tries its best to remove--add another hundred.

Beating a drum into a drum Winston Spree Simon

26 | Natural Pasts

Mannette remained with Shell until 1967, as a sales manager, steel-drum

maker and leader of pan band the Shell Invaders. He went on to become the

artist-in-residence and then a professor of music at West Virginia University in

the US . Another Shell Invader, Malcolm Weekes, received an annual US $2,000

scholarship to attend university in Washington, where he played the double

alto for the school's Trinidad Steel Band and graduated with a degree in

chemical engineering. "We had bonfires to burn out all the crap stuck inside

the drums. It was dangerous work. We inhaled the fumes. But what the barrel

contained also helped define the sound of the drums," the former Shell

Invaders' star was to reminisce later.

Shell company archives, however, make no note of this band the company

help found. Or any steelpan music at all. For the company they are almost

relics of a past embarrassment.

Natural Pasts | 27

Seven thousand years ago, about 100 km from the contemporary port

city of Arica in Chile, a child died. The grieving parents did not want to

part with the last remains. They removed the head and internal organs

of the child, stuffed it with animal hide, painted a clay model of his head and

decorated it with tufts of his hair.

The delicately preserved body was excavated in 1983. Archaeologists

believe it is the earliest mummy. More than 100 child mummies were

discovered in Camarones near Arica that year. Later, preserved bodies of adults

were found as well. Archaeologists say the embalmed bodies were of people

from Chile's Chinchorro community.

Unlike mummies in later civilizations--most notably Egypt that flourished

Parents' keepsake■ SAVVY SOUMYA MISRA

A mummified Chinchorro baby in SanMiguel Museum in Arica city

28 | Natural Pasts

for 2,500 years beginning 3,000 BC--that spun around prestige, wealth and

power, Chinchorro mummification was based on a democratic and

humanistic view of the dead, and everyone was mummified.

Archaeologist Bernardo Arriaza, who studies the Chinchorro at the

University of Tarapaca in Arica, wrote that unlike the Egyptians who hid the

dead, the Chilean community embraced them. The child mummies even took

their place besides their parents at the dinner table.

A few years ago Arriaza launched a daring new theory the Chinchorro were

victims of arsenic poisoning. "I was reading a Chilean newspaper that talked

about pollution and it had a map of arsenic and lead pollution, and it said

arsenic caused abortions. I jumped in my seat and said, That's it," Arriaza said.

Following the lead, Arriaza collected 46 hair samples from Chinchorro

excavated from 10 sites in northern Chile. Ten samples from the Camarones

river valley had an average of 37.8 microgrammes per gramme--much higher

than one to 10 microgramme of arsenic per gramme

that indicates chronic toxicity according to World Health Organization

(WHO) standards. The sample from an infant's

mummy had a residue of 219 microgramme per gramme. One theory is that

they could have washed their hair with arsenic contaminated water but

pathologists explain that washing is unlikely to leave such high levels of arsenic

traces.

Arriaza has another explanation. Chinchorros were a fishing society. They

collected plants along river mouths and hunted both sea mammals

and wild birds. They made fishhooks out of shellfish, bone or cactus needles,

spear throwers were used to hunt sea lions and wild camelids, while both lithic

points and knives were manufactured using flint stones.

The Chinchorro lacked ceramic vessels, metal objects and woven textiles,

but this was not a social handicap their simple yet efficient fishing technology

allowed them to thrive along the Pacific coasts.

But life was not without dangers. In the 1960s tests on water drawn by the

city of Antofagasta in the Camarones river valley showed that it was laced with

860 microgrammes of arsenicper litre--86 times higher than the limits

acceptable by WHO. Arriaza believes this was so even 7,000 years ago. Tests on

the Chinchorro mummies strengthen the arsenic poisoning theory.

He also believes Chinchorros suffered from chronic ear irritation and

Natural Pasts | 29

impairment probably due to continuous fishing in the Pacific Ocean's cold

waters. They also suffered from parasitic infections from eating poorly cooked

fish and sea lion meat.

"In highly stratified societies like ours, lower-class children receive simple

or meager mortuary disposal.

But in a small group, the death of children certainly threatened the

survival of the entire group. Affection and grief may thus have triggered the

preservation of children," the archaeologist said.

Chinchorro morticians made incisions to deflesh the body and removed

internal organs. Clay, grasses and feathers were used to fill the cavities.

The bodies were painted bright red from head to toe, the face was painted

black or brown. A long wig up to 60 cm was used to ornament the head. Facial

features were modelled to convey life.

30 | Natural Pasts

On October 2, 2008, India

joined a growing number of

countries that have

implemented far-reaching smoke-free

legislation. But a look back reveals that

tobacco bans are hardly new--and

rarely permanent. Some of the earlier

smoke-free legislations:

1575A Mexican ecclesiastical council

forbids the use of tobacco in any

church in Mexico and Spanish

colonies in the Caribbean. The

prohibition is ineffective. The order

does not deter even priests from

smoking on church premises.

1590Pope Urban VII threatens to

excommunicate anyone who takes

tobacco in the porchway of or inside a

Roman Catholic church, whether by

chewing it, smoking it with a pipe or

sniffing it in powdered form. But

Urban VII who believed smoking

detracted from the clergyman's duties

has a 13 day reign and his successor

Gregory XIV makes no mention of a

ban on tobacco.

1624On grounds that tobacco use prompts

Stub cut short

Natural Pasts | 31

sneezing, which resembles sexual ecstasy, Pope Urban VIII issues a worldwide

smoking ban and threatens excommunication for those who smoke or take

snuff in holy places. A century later, snuff-loving Pope Benedict XIII repeals all

papal smoking bans--the embarrassing sight of priests sneaking out of Church

premises to steal a smoke plays a role in the revocation. In 1779, the Vatican

opens a tobacco factory.

1633The Ottoman ruler Murad IV prohibits smoking in his empire; 18 people are

executed for breaking the law in one day in his reign. Murad's successor,

Ibrahim lifts the ban in 1647, and tobacco soon becomes an elite indulgence-

-joining coffee, wine, and opium, according to a historian living under

Ibrahim's reign, as one of the four "cushions on the sofa of pleasure".

1634Czar Michael Feodorovich of Russia bans smoking, threatening offenders with

whippings, floggings, a slit nose, and a one-way trip to Siberia. His successor

Alexei Mikhailovitch rules that anyone caught with tobacco should be

tortured until he gives the name of the supplier. But by 1676 the ban on

tobacco is off.

1638China's Ming emperor decrees any person trafficking in tobacco will be

decapitated, the decree is ineffectual: smoking spreads within the court.

1640The founder of modern Bhutan, the warrior monk Shabdrung Ngawang

Namgyal, outlaws the use of tobacco in government buildings.

1646The General Court of Massachusetts Bay in then British American colonies

prohibits residents from smoking tobacco except when on a journey and at least

five miles away from any town. The next year, the colony of Connecticut restricts

citizens to one smoke a day, "not in company with any other." By the early 1700s,

the British American colonies are major tobacco consumers and producers.

32 | Natural Pasts

1818Smoking is banned on the streets of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, USA. The mayor

is fined when he becomes the first man to break the law.

1891Angered by the Shah's tobacco concession to England, Iranians protest, and

the Grand Ayatollah--Iran's religious leader--Haji Mirza Hasan Shirazi issues

a fatwa banning Shias from using or trading tobacco. The tensions spark the

Tobacco Rebellion--according to historians the beginning of a long

confrontation between Iran's rulers and its clergy over foreign influence. In

1892, once Iran cancels all its business dealings with England, people in the

country resume smoking.

1895North Dakota in the US bans the sale of cigarettes. In 1907, Washington passes

legislation banning the manufacture, sale, exchange or giving away cigarettes,

cigarette paper or wrappers.

1914Smoking is banned in the US senate.

By 1920, 15 US states have laws banning the sale, manufacture, possession and

use of cigarettes, propelled by the national temperance movement. Anti-

smoking crusader Lucy Gaston announces her candidacy for president in

1920--the same year Warren G Harding's nomination is decided by

Republican Party bosses in a "smoke-filled room." By 1927, all smoke-free

legislation in the US --except that banning the sale of cigarettes to minors--is

repealed.

1942Adolf Hitler directs one of the most aggressive anti-smoking campaigns in

history, including heavy taxes and bans on smoking in many public places.

The country's antismoking movement loses most of its momentum after

World War II.

34 | Natural Pasts

In ancient and medieval Europe, May signalled the onset of spring. It

meant the onset of the warmer part of the year. For most people it was

time to end winter hibernation, and reconnect with friends and loved

ones. It was the time of festivities.

Before Christianity took root, the Celts and Saxons celebrated May 1 as

Beltane or the day of Bel, the Celtic god of sun and fire. To honour the fire

god, torch bearing peasants and villagers would climb top of hills or mountain

crags and light wooden wheels, which they would roll into the fields below.

The celebrations signified the soil's return to fertility, after a long—and usually

exacting—winter. Cattle were driven through the smoke of the Beltane fires,

and blessed with health and fertility for the coming year.

The festivities began with Celtic communities selecting a virgin as “May

Queen” to lead the march to the top of the hill. She represented the virgin

goddess on the eve of her transition from Maiden to Mother. Her consort was

variously called, “Jack-in-the-Green”, “Green Man,” “May Groom” or “May

King”. He would be the king or priest for a day. But May Day was also a day

of social inversion. So the symbolic lord would be butt of the much humour

and ridicule—the sort peasants could only murmur about their their real

lords.

In less agrarian societies this one-day chief was called the King Stag. He

had to run through the woods with a pack of deer in tow. Only after he had

successfully locked antlers with and killed a stag, could the King Stag return to

the festival and claim his right as consort to the May Queen.The union of the

Queen and her consort symbolised the fertility and revitalisation of the world.

Usually, the festivities involved the raising of a Maypole around which

young single men and women would dance. Historians believe the Maypole to

be a phallic symbol, but many Celtic communities regarded the pole as

pathway by which demons trapped in the earth could climb to the surface—

and from there escape to heaven. They set up maypoles as a way of releasing

evil spirits from their prison in the earth. Historians see this as another

symbolisation of the rebirth of the soil.

Christianity scoffed at this tradition. The observances were outlawed in

many parts of Europe. But like many pagan observances, the church could not

root out Beltane festivities. Every year, Christian priests would lament the

number of virgins despoiled on Belane, but the peasants ignored the jibes.

Natural Pasts | 35

They believed babies born from a Beltane union were blessed.

While it failed to root out the festivities, the church tried to assimilate the

May I festivities. I some places, May Day became Mary's Day—the May Queen

became virgin Mary. Some Catholic priests preached that Christ was crucified

on a Maypole.

Around the 15th century, the Church gave its blessings to less riotous

celebration: the Mayfayre, later known as the May Fair. For traders and

artisan's guilds, the fair became a chance to display their wares.

When industrialisation took roots in Europe, most workers had roots in

rural areas. They came from peasant and artisan families. In the late 19th

century, the festival of pagan origins became associated with the struggle for

an eight-hour working day. On May 1, 1890, the leaders of the Socialist

An artist's impression of Raising of the Maypole

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY: CHAMBER'S BOOK OF DAYS

36 | Natural Pasts

Second International called for an international day of protest. They did so

just as the American Federation of Labour was planning its own

demonstration on the same date. Both protests were hugely sucessful.

Initially, May Day was intended to be a one-off protest, and perhaps a

solemn affair. But with trade unionism flourishing, May Day developed a

carnivalesque character—somewhat akin to its pagan roots. May Day

celebrated working class solidarity with the paraphernalia of badges, flags, art,

sporting events, fairs and heavy drinking. Historian Eric Hobsbawm calls May

Day, the only unquestionable dent made by a secular movement on the

Christian calendar.

But like the Christian church, the modern state was quick to assimilate the

symbolism of May Day. May 1 is a holiday in many parts of the capitalist

world. And, according to Hobsbawm, Nazi Germany one of the first few

countries to declare May I as a paid holiday.

![[C P Kaushik, S S Bhavikatti, Anubha Kaushik] Basi(BookFi.org)](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/55cf9b90550346d033a68cc1/c-p-kaushik-s-s-bhavikatti-anubha-kaushik-basibookfiorg.jpg)