Karuturi CaseStudy PartA Draft2

Transcript of Karuturi CaseStudy PartA Draft2

Copyright © 2008 London Business School. All rights reserved. No part of this case study may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise without written permission of London Business school.

This case was prepared under the guidance of Professor Nirmalya Kumar by Nilav Bose (MBA 2012) and Sanjeev Mehra (MBA 2012) as a basis for class discussion and is not intended to serve as an endorsement, a source of primary data, or an illustration of effective or ineffective management.

ecch: Nirmalya Kumar London Business School REF: Nilav Bose, Sanjeev Mehra Date: Jan 12, 2012

Karuturi Global – Don’t crave roses if you can’t grasp thorns OR

How a small Indian company is working overtime to transform East African agriculture

In April 2008, Ram Karuturi, the CEO of Karuturi Global (hereafter Karuturi) received a proposal to set up a large agriculture farm in a remote corner of western Ethiopia. The Ethiopian government was offering Karuturi more than 300,000 hectares of land, an area that was more than seven times the size of Mumbai city, at favourable prices to grow food crops. Ethiopia and its neighbouring countries faced food shortages, but had an abundance of undeveloped land. However, Karuturi had no prior experience with food crops let alone farming on such a large scale. Outsized investments would be needed to bring this land to production, and the risks were immense for a company of Karuturi’s size. The tract of land offered bordered war-torn Sudan and had little infrastructure. Success would make Karuturi one of the largest food producers in the world within a few years if it was developed well. But Ram also realized that it would change his life for the next several years, and he would have to make immense personal sacrifices to make this work. Not the wrong company for the job Karuturi however was not new to such growth prospects. Incorporated in 1994 in the south-Indian city of Bangalore, then a wooded and laidback city known more for multiple Indian government public sector enterprises than anything else, Karuturi had by 2008 become the world’s largest cut rose producer exporting about 1.5 million stems of 40 different rose varieties a day to markets in Japan, Australia, South-East Asia, the Middle East, Europe and North America. And it was no novice in Africa either, with most of its production coming from two east-African countries – Kenya and Ethiopia. In a span of about 15 years, the company had broken into the mature rose market dominated by European farmers and managed to capture about 9% of the European market share. From modest beginnings

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

2

After finishing his undergraduate studies in Mechanical Engineering from Bangalore University and then obtaining an MBA from the Case Western Reserve University in the US, Ram Karuturi joined the family business - Deepak Cables in 1990. India had just begun liberalizing its economy and was beginning a new phase of economic development. Deepak Cables was an established business, and was expected to do well in the liberalized economy. However wanting to do something different and on his own, he left after four years. During his childhood and before moving into the cables business, the family had developed a large tract of land for cultivation in the rice belt in the Indian state of Karnataka. Ram had grown up in a farm environment and even today he credits those formative years as eventually influencing his decision to move into farming, something that he has been passionate about throughout. This decision did not come straight away though. He initially pondered the meat processing business as he felt there was good availability of cattle in India and a huge market in the MiddleEast. However, in early 1994, a meat-processing plant in the sate of Punjab was shuttered after pressure from Indian NGOs not long after it began operations. Ram realized that the socio-religious situation in India would not allow such a business to be successful. Subsequently, while on a sabbatical to Israel, he saw opportunities in greenhouse farming. His move into floriculture was moulded by this trip and the subsequent discovery of the gap in demand against the supply of roses in the international market, and Bangalore’s favourable climatic conditions for rose growing. By 1996 had setup a four hectare rose farm in Doddaballapur near Bangalore. His family was not initially serious about his plans; he says “My family thought that this was a passing interest and that in a year, I would fail and go back to the cables business”. Although India liberalized its economy in 1991, doing business in the country had become easier only in a relative sense - India was still not an easy place to establish an export-oriented business of scale. There were the well documented issues with infrastructure shortages such as with regional airports that were required by Karuturi to ship large volumes of roses. Bangalore airport was owned by a public sector defence manufacturing company which out of necessity was being used as a civilian airport, but was not equipped with critical facilities such as cold storages required for bulk exports of perishables. Roads from the farm to the airport were underdeveloped resulting in long delivery times due to traffic jams. Tax laws and bureaucratic procedures were still complicated and capital remained in short supply - Karuturi’s first loan from the Industrial Development Bank of India cost an eye-watering 18% per year. Achieving leadership at home By 2003, Karuturi had become the lowest-cost and largest single rose producer in India. It was not just reliant on exports and had worked with the Karnataka government to set up the first rose trading exchange in Bangalore, where Dutch-style auctions had been initiated. It had also ventured into food processing (Gherkins for export) and information technology as an internet service provider. However floriculture was its main business and Karuturi was still producing only about 8 million roses a year, which was a negligible fraction of the global market. India, and its cities like Bangalore, was developing rapidly resulting in cost-based inflation that was eating into Karuturi’s bottom line. Meanwhile, African rose growers, its main competitors in the key European market, had a significant cost advantage over

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

3

Karuturi in production and transportation, which when combined with a favourable tax structure, resulted in lower cost to market of over 25%. Realizing that he would not be able to compete for long on price in the competitive international market, Ram took the bold step of shifting production to Africa. However he chose Ethiopia over Kenya (which was then the established rose production center in east Africa) as it had the same favourable climate but being less developed, had lower establishment and operational costs. Moreover Ethiopian exports to Europe were exempt from customs duty which made his overall product pricing even more favourable. Karuturi’s decision to move into Ethiopia turned out to be a landmark giving the company a base in Africa and the experience to launch its next phase of growth a few years later. At that time however, it was fraught with immense risk. Karuturi had no prior experience of operating a foreign site and that too in an African country about which not much was known to investors. There was also no precedent of any significant corporate Indian investments into Ethiopia whose experience and resources he could leverage. In the absence of any meaningful investment protection, the possibility of losing the entire investment due to a change in government or the political environment was a possibility. Given this uncertainty, Karuturi was very cautious and spent a good amount of time doing its due diligence. The size of the investment was also small and would not have a significant impact on the overall company were it to be lost. Ram says “We decided to invest Rs. 20 lakh, and I had at the back of my mind that the day I lost Rs. 18 lakhs, I would go home without thinking much about anything” Becoming a global player of scale By 2006, Karuturi had managed to fully operationalize its first facilities near Addis Ababa and was looking at acquiring additional sites in the area for expansion. It had competent management in place, drawing talented people from its operations in India, and was well versed with doing business out of Ethiopia. At this time it came across an opportunity to acquire one of the world’s largest standalone rose farms – Sher Agencies. A Dutch family owned rose producer was offering 188 hectares of its greenhouse assets in Naivasha, Kenya, which it had set up in the early nineties. After months of due diligence and negotiations, Karuturi finally bought out the assets for USD 67 million in Sep. 2007, and in a single move became the single largest producer of cut roses in the world producing over 650 million stems a year translating to a 9% share of the European market. The transaction was financed through a USD 50 million FCCB (foreign currency convertible bonds) offering to foreign institutional investors and the rest through retained profits. The acquisition was not without its share of problems. On the day of the takeover, employees stopped working en-masse as there was confusion among them as to whether they had their jobs or not, and as to whether they would manage to keep all their benefits accumulated through their service years. There was also a lot of scepticism about the attitude of the new owners towards wages, welfare and development, some of which came from the general perception that Indian businesses were low cost model operators which would be bad for employees. Ram realized that he had to move quickly to control the

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

4

situation. All employees were gathered in the company’s football stadium and Ram outlined that none of the employees would be laid-off and also promised to maintain and improve their benefits. At the same time he drew the line on discipline, and announced that any employee who would like to leave would be paid full benefits immediately but if all employees did not resume work by that afternoon, the company would close down the farm. These first steps went a long way in defining the image of the new management as sympathetic but strict no-nonsense businessmen. Only about a hundred of the four and half thousand workers left that day and the rest returned to work. But then in the last week of 2007, crisis struck again as Kenya became engulfed in a civil unrest after incumbent President Mwai Kibaki was declared the winner of the presidential election. The opposition Orange Democratic Movement alleged electoral manipulation and large scale rioting and targeted ethnic violence primarily against Kikuyu people broke out in several parts of the country. This had the immediate effect of workers not being able to come to work, and also workers from the affected ethnicity worrying about their own safety on the farm. Ram moved quickly and refused to leave despite suggestions from many friends - what was initially a humanitarian gesture eventually saved the business from large losses. He increased security on the farm by hiring an additional 400 armed guards. Employees were warned that any ethnic intimidation or discrimination on the farm would be dealt with sternly. At the same time he provided shelter for affected employees in the company run school and hospital, ordered more than 6000 blankets and also asked employees to bring over their affected dependents. This brought some sense of security to the area and increased faith in the management. Whereas several other farms in the area had to curtail operations due to shortage of labour, Karuturi now had an excess supply of labour for the farm through the dependents who had sought shelter and had nothing to do. Roses were trucked out of the farm between midnight and dawn, when there was usually a lull in violence (this is something Ram had learned from a police officer in India several years ago). Over a few months, after a UN brokered power sharing agreement between the rivals, Kenya returned to normalcy. The management’s response to the crisis however generated a lot of goodwill and this helped the new owners consolidate control over the enterprise. Foray into Agriculture By the middle of 2008, the Kenyan operations were stable. Karuturi now had about 240 hectares of greenhouses producing roses in Kenya, Ethiopia and India. Revenues had reached USD 100 million for the first time with overall EBITDA margins of over 35%. With floriculture accounting for 97% of the revenues, the company was looking to diversify and was already operating a small food processing unit for gherkins near Bangalore. At the same time it was putting in place plans for the next phase of growth. The plans however revolved around Ethiopia which, being at a lower point in the development curve when compared to Kenya, had much lower costs for the floriculture business. At 100 hectares and employing over 3000 people, the planned Wolisso (located 90 km from Addis Ababa) facility was much larger than Karuturi’s flagship operation near Addis Ababa. At this point Karuturi was presented with an opportunity to acquire a large amount of fertile land in the Gambela province of western Ethiopia. 300,000 hectares of virgin land rich in organic content (over 5%) was offered by the Ethiopian government for a 50 year lease at

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

5

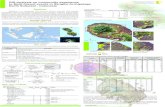

an unbelievably low rate of about 245 USD a week. Moreover, the land in Gambela was located on the banks of the perennial Baro river, making the entire offering very favourable for the company. Karuturi was also offered a smaller 10,000 hectare plot of developed land in Bako in central Ethiopia. The Ethiopian government was clear that it was leasing out ‘uninhabited wildernesses’. The Gambela province has offered about 1.1 million hectares of land for lease, and about 900 companies including major ones from Saudi Arabia and China are reported to have invested in the region so far. This seems to make strong economic sense for a country like Ethiopia – despite its primary dependence on agriculture; the country suffers from massive food shortages and was estimated to have received more than 700,000 tonnes of food aid in 2010. Moreover, unlike some other African countries, Ethiopia is not an oil-producer and thus does not have access to petro-dollars that would allow it to purchase food grains from the international market. Notwithstanding, Ethiopia’s decision to lease its land has generated a lot of criticism, notably from outside of the country, with several writers and social organisations questioning the benefits to the local country of such large-scale industrialized farming. Some have even termed the large scale leasing of land as a ‘land-grab’ and ‘re-colonization’. Unsurprisingly however, there has been limited criticism from within the country itself - says Chombe Seyoum, a UK educated Ethiopian entrepreneur from a family of farmers, and currently also distributor for John Deere based out of Addis Ababa “No doubt the land has been given cheaply, but hundreds of millions of dollars are coming into the country through these investments, and this money is being spent here, on local wages, procurement and infrastructure – this cannot possibly be bad for a country like Ethiopia”. There are several factors that make Ethiopia a favourable destination for farming. It is strategically located at the north-east corner of Africa closer to Asia and the Middle East and more easily accessible than most of the continent. It has one of the fastest growing economies among non-oil producing African countries with agriculture estimated to account for about 80% of the employment. Besides significant local demand (with a population of 85 million), it has preferential trading status with neighbouring countries as a member of COMSEA (Common Market for East and Southern Africa), is able to easily export to the USA under the Africa Growth Opportunities Act, and enjoys duty-free agricultural exports to the European markets through the Lome convention. There are large areas of undeveloped fertile land with low population densities, access to water through rivers and favourable climactic conditions for a variety of crops, and low labour costs. Law and order is well maintained, there is swift judicial redressal and the society is largely corruption-free. Culturally the people are non-confrontational and processes and systems in Ethiopia government and bureaucracy are relatively well established. However, the low cost of Karuturi’s land concession reflects the risk inherent in its investment. The land offered was in the remote undeveloped western corner of the country, close to the Sudan border with an uncertain security environment that required military protection. Up until 2010, the area was connected to Addis Ababa by only a mud road. Gambela airport, the only port of access for investors was merely a small airstrip with a shed (see figure). Finally, with Ethiopia being land-locked, the Baro river, a distributary of the Nile, was probably the only avenue available for transporting the farm’s produce.

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

6

However, even this waterway was undeveloped and required passage through areas with high security concerns. Given the complete lack of downstream infrastructure in the local area Ram plans to develop the area as an agri-economic zone with sugar factories, oil processing plants, rice mills and other food processing facilities on site. Joint-ventures with established companies in each sector with specialized knowledge and organisational infrastructure would form the optimal route. Karuturi’s own contribution would be in the areas of project implementation and execution, land development, and in facilitating the joint ventures by bringing in investors and companies. Areas would be developed in phases with a mix of short cycle crops such as maize and sugarcane crops to generate revenues towards investments in the long-cycle crops such as palm oil which has a seven year gestation period. Power to operate the planned facilities would be generated through a mix of hydo-electric power plants and rice husk and bagasse (a bye product of the sugar production process) based power units. Capital would be raised through a mix of equity and debt offerings to both domestic and foreign institutions.

The present: Large greenfield projects are hard work, and very uncertain By the end of 2009, Karuturi had begun land development in Gambela and in 2011 planted its first crop of maize, the easiest short-cycle crop possible in the area. The land in Bako, which did not require initial development, was already producing maize. But the key challenge lay with the Gambela site which was central to the company’s ambition of becoming a large transnational food producer. Karuturi began with a conservative approach to the development of the Gambela land. With cost control firmly at the center of its resource strategy, its initial plan was to procure a large number of low cost farm machinery such as tractors and bulldozers from suppliers in countries such as India that they were already familiar with and deploy them for farming. But it soon realized that Indian farm equipment was never designed to operate large sized

Figure 1: Gambela airport was a small tin shed when Karuturi was offered the land in 2008, and was the only way of accessing the designated area

Figure 2: Gambela airport in Dec. 2011

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

7

farms and were more suitable for single family farms back in India. There were reliability issues, with equipment having lower run cycles than high-end western alternatives, and this was compounded by poor service and support networks in Ethiopia resulting in high equipment downtime and manual intervention. After spending several million in equipment that lies largely unused today, Karuturi changed strategy in 2010, and began roping in suppliers such as John Deere that already had vast experience and high technology machinery products to serve industrial farms. It placed orders for large tractors and heavy duty ploughing, seeding, watering and harvesting equipment. While servicing issues refuse to go away completely, with the changed strategy the gain in efficiencies has been immense and immediate. Attracting skilled labour has been another serious challenge – while there is enough availability of local labour, these personnel are largely unskilled in the methods of modern farming. Karuturi thus has to spend a considerable amount of time in training after it hires its workers. Management talent is simply unavailable and it is recruiting managers from India, mostly managers serving with or retired from public sector enterprises that have the skills and also desire to be involved in challenging opportunities. While Karuturi has been able to find talented people willing to spend time on the site in remote Gambela, there is criticism that many of its current managers have no experience with industrial farming, given their backgrounds, and this is leading to many incorrect decisions, lost revenues and increased costs. Karuturi seems to have realized this shortcoming and is now planning to hire consultants with direct industrial farming experience from countries such as the USA and Uruguay. But even the best strategies can fail in agriculture when it comes to the effects of nature. With the land in Gambela along the Baro river, the company spent a lot time building dykes along the entire stretch prior to planting its first crop. Irrigation facilities, as with the rest of the facilities on the farm were being developed in phases. Low lying land on the banks of the river was cleared first and planted with the maize crop. But in Sep. 2011, a few weeks before the harvest of its first maize crop, the area experienced floods that were stronger than in recent memory and overwhelmed the newly constructed dykes. The floods wiped out crops that would have produced 50,000 tonnes of maize and delayed the project’s first revenues. At the time of writing the case, Karuturi was re-evaluating its approach to the development by advancing the construction of irrigation infrastructure for higher placed un-submerged areas, planning to remove flood waters from the low-lying areas by using pumps and discharge canals, and constructing additional dykes. The stock market has been quick to pick on these execution risks. After reaching a multi-year high of Rs. 37 in Oct. 2010, Karuturi’s stock (listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange and the National Stock Exchange in India) has declined more than 85% at the time of writing the case, which the company thinks is unwarranted. Says Ram “I did not think the high valuations in 2010 were justified. We are a food producer, not an internet start-up. At the same time current valuations are also unjustified. We have been open about the extent of risk in our operations through full disclosure throughout and of the damages caused by recent floods, but it seems the market has over risked our operations based on these disclosures”

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

8

This difference in risk perception is evident even in the company’s operations, although in a very different way. With most of his mangers having worked in structured decision making environments and thus lacking entrepreneurial experience, there is a conspicuous absence of risk taking at the lower management levels. Ram has been quick to realize this and when new initiatives are needed he leads from the front. For instance, with the issue of floods - Being grasslands, the water did not dry out quickly, and could take years till the land became arable again. Hence the company is now working on developing drainage solutions. To assess the damage, search for drains and signal his risk appetite, Ram personally drove a tractor miles into a flooded field, something he says his managers would not have done on their own for fear of submerging or damaging the expensive tractors. He says “Risk, if properly calibrated can be broken down in parts into issues that can be resolved and thus the risk eliminated”. Looking ahead – one of the largest food producers by the end of the decade? When you meet and get to know Ram Karuturi, you get the sense that his passion to become a global food producer of scale is the overarching driving influence of his life at this moment. He himself acknowledges that he has been lucky in his opportunities and gets to spend most of his time on what he loves most – agriculture. And quite logically as well, as without this passion it would be hard to make the personal sacrifices that are needed in developing his venture. He spends a significant amount of time travelling and on site in remote Ethiopia away from his wife and three school going children who are based in Bangalore. Like never before in its existence of 17 years, Karuturi now has an opportunity that very few companies of its size come across – if the Gambela project is executed well, Karuturi would be one of the ten largest food producers in the world. It would be a major producer of sugar and have its own brand of palm oil. There have been Indian companies like the Tata’s that have made strategic acquisitions to gain global scale and outreach, but there are few examples of Indian companies generating scale through such large scale greenfield developments which are seen as high risk ventures. In this context the company faces a clear challenge: it has to operate on scale to have a good chance of recovering its large initial investments and developing a sustainable production model, but at the same time it is constrained by its lack of experience in industrial farming. Managing costs will be critical going ahead. Given the overall shortage of food in the region, the company plans to sell most of its produce to the COMSEA countries – but even with many of these countries being net importers of food, local farmers have to compete on price with imports from developed countries where agriculture is subsidized on a large scale. Often local produce is unable to compete with import prices, putting domiciled farmers out of business. Given such expected pricing pressures, the rates at which the company was offered the land is not surprising. Development cost control is also critical as macro-economic challenges may hinder additional capital raising additional. The Indian corporate bond market is undeveloped, the company has already used up a good amount of the credit available from Indian banks and foreign debt is also hard to come by at the present due to macroeconomic factors in India and abroad. And given its low stock valuation, any equity issues will be hugely dilutive. This leaves retained earnings as the

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

9

primary source of future CapEx – the stable rose business generates healthy cash flow that it can draw upon. The company recognizes its challenges and is working on reducing risk in its development plans. Its biggest challenge currently is to strengthen its irrigation and flood control infrastructure, and for this it has retained the services of two consultants to advise on flood control measures besides designing an irrigation and drainage system. It is in talks with its suppliers to outsource the entire maintenance and operation of its equipment fleet and is talking with institutions such as the Africa Development Bank (AfDB) for additional capital. It is bringing in consultants – people with direct experience in large scale farming from countries such as the USA. It has also enjoyed a lot of support from both the Indian and the Ethiopian governments. It is a member of the ‘India Business Forum’ in Addis Ababa that acts as an advisory and resource body for Indian businesses in Ethiopia. At the time of writing the case, it has also completed most of the processes to obtain political risk insurance from MIGA, an arm of the World Bank. Karuturi is also conscious that it is doing business in one of the most deprived regions of the world, and it is keen to contribute to overall well-being of the communities it operates in. It wants to develop local talent and does not plan to rely much on foreign workers. The long term target is to cap the foreign population in its operations at 2%, down from the current 5%. In some areas, such as in sugarcane farming it thinks it has access to better skills locally than elsewhere in the world. In areas where there is a significant local skills deficit such as in palm oil, it plans to rely on foreigners, for example highly skilled subsistence farmers and land croppers who have very little future in agriculture in India but are willing to put in tremendous efforts when given the opportunities that Karuturi can. In Kenya, it provides free healthcare in Naivasha through a company operated multi-facility hospital and runs schools for more than 2000 children of employees. The Karuturi football team plays in the Kenyan Premier League and the Kenyan Cricket team is also sponsored by the company. In Ethiopia a low cost hospital is being planned in Addis Ababa in partnership with one of the pioneers of low cost quality healthcare providers in India. Even in Gambela, though the farm has barely managed to build up basic facilities for its workers, it is already involved in building a school and hospital, and in the process propagating low cost housing technologies that have already been deployed effectively in India. Besides this it is involved in rural drinking water projects and plays a part in the US government’s ‘Feed the Future’ program for Africa and some USAID initiatives in the region. Says Ram “A big motivation for taking up this project was the Ethiopian famine in 2008 when the project was offered to us – we believe with this project we can alleviate the shortage of many food crops in the country”

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

10

Exhibit 1: Details of Karuturi’s production facilities in Africa

Site Company name Country Area Crop Farm StartInvestmen

t (Mil USD)

Employed Remarks Lease period

1Holetta, 40 kms from Addis Ababa

Ethiopian Meadows

Ethiopia108 Ha, 50 Ha (net cultivatable area under green house)

Floriculture 2005 18 1700

15 years being extended to 30 years

2Wolisso, 96 kms from Addis Ababa

Surya Blossoms PLC Ethiopia

Total land 372 HA, Developed 77 Ha, Expansion plans in 2012/2013 is 111 Ha

Floriculture 2008/2009 78

1000 scaling to 5000 after expansions

30 years, till Sep 2037

3Naivasha, 90 kms from Nairobi

Karuturi Limited

KenyaTotal land : 200 Ha, 160 Ha (under green house)

Floriculture 2007 60 5000

Acquisition of the Kenya-based Sher Agencies in September 2007 from Dutch horticulturists Gerrit & Peter Barnhoorn. The farm also houses a High-Tech nursery which produces close to 500,000 plants per month. The company produces close to 350 million stems p.a.

NA

4Gambela, 800 Kms from Addis Ababa

Karuturi Agro Products PLC Ethiopia 100,000 Ha in Phase 1

Agriculture growing Oil Palm, Sugarcane, Maize, Paddy, Sorhum, Cotton etc

2009

900, scaling to several thousand

50 years, till 2058

5Bako, 250 kms from Addis Ababa

Karuturi Agro Products PLC Ethiopia 11,700 Ha

Maize, paddy, and other cereals 2008 300

45 years, till 2053

6Doddaballapur, Bangalore

Karuturi Limited India Total land : 10 Ha Roses Pre 2000 3000

350

Produces close to 200 million stems p.a. out of the Ethiopian farms. The farms also house a high-tech nursery which produces close to 500,000 plants per month.

Exhibit 3: Company revenues and EBITDA

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

11

Exhibit 2: Consolidated Financial Data

FY2007 FY2008 FY2009 FY2010 FY2011 Revenues 1,013 3,955 4,458 5,338 6,387 Operating Expenses (569) (2,555) (3,002) (3,418) (4,004) EBITDA 444 1,401 1,456 1,920 2,383 Depreciation & Amortization (39) (112) (154) (556) (619) Finance Charges (15) (54) (208) (65) (266) Other Income 4 19 78 129 65 EBT 394 1,253 1,172 1,428 1,564 Exceptional Items 2 (211) 10 - - Tax (3) (14) (8) 6 (14) Profit After Tax 393 1,027 1,173 1,434 1,550 Share Capital 120 331 453 489 806 Share Warrants 1,689 - 760 - Reserves & Surplus 846 2,827 5,781 7,197 12,386 Total Equity 966 4,848 6,234 8,446 13,192 Debt 1,230 3,114 4,668 4,397 5,585 Sources of Funds 2,196 7,962 10,902 12,843 18,777 Goodwill 1,171 116 757 1,127 Fixed Assets 535 4,027 6,893 9,174 12,111 Capital WIP 182 1,024 1,461 1,308 1,565 Investments 3 121 12 13 28 Long Term Assets 720 6,345 8,482 11,252 14,832 Current Assets 1,616 2,332 2,439 2,512 5,100 Less:Current Liabilities (136) (818) (508) (1,077) (1,223) Net Current Assets 1,479 1,515 1,932 1,435 3,876 Deferred Tax Asset/(Liability) (6) 7 2 6 2 Forex Adjustments - - - 150 67 Misc Expenditure not written off 3 96 486 - - Uses of Funds 2,196 7,962 10,902 12,843 18,777 Operating Profit 445 1,192 1,525 1,990 2,287 Increase/(Decrease) in Working Capital 272 961 451 (690) 808 Cash Flow from Operations 172 231 1,075 2,680 1,479 Net Investments (569) (5,736) (3,044) (2,680) (4,374) Increase/(Decrease) in Goodwill - - - 169 (65) Increase/(Decrease) in Forex Adjustments - 50 752 (1,072) (1,145) Interest & Dividends 4 16 19 1 4 Others - (93) (380) 0 - Cash Flow from Investments (565) (5,763) (2,653) (3,581) (5,579) Net Proceeds from Equity 247 2,911 121 1,201 3,803 Net Proceeds from Debt 1,158 1,815 1,424 (19) 1,005

London Business School ecch:

Copyright © 2008 London Business School

12

Increase/(Decrease) in Hedging Reserve - - - (28) 100 Dividends (28) (29) (67) (45) (61) Cash Flow from Financing 1,377 4,698 1,478 1,109 4,847 Net Increase in Cash during the year 985 (835) (100) 208 747 Cash & Equivalents at the beginning of the year 29 1,014 180 424 632 Cash & Equivalents at the end of the year 1,014 180 79 632 1,379