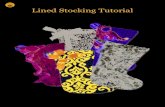

Karl Krinken, His Christmas Stocking

-

Upload

alreadyaaken -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Karl Krinken, His Christmas Stocking