Karen J. Gibson BLEEDING ALBINA:A H ISTORY OF …

Transcript of Karen J. Gibson BLEEDING ALBINA:A H ISTORY OF …

3

Transforming Anthropology, Vol. 15, Numbers 1, pps 3–25. ISSN 1051-0559, electronic ISSN 1548-7466. © 2007 by the AmericanAnthropological Association. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content throughthe University of California Press’s Rights and Permissions website, http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintInfo.asp. DOI: tran.2007.15.1.3. 3

Karen J. Gibson

BLEEDING ALBINA: A HISTORY OF COMMUNITY

DISINVESTMENT, 1940–2000

Portland, Oregon, is celebrated in the planning litera-ture as one of the nation’s most livable cities, yet thereis very little scholarship on its small Black community.Using census data, oral histories, archival documents,and newspaper accounts, this study analyzes residentialsegregation and neighborhood disinvestment over a60-year period. Without access to capital, housing con-ditions worsened to the point that abandonment becamea major problem. By 1980, many of the conditions typi-cally associated with large cities were present: highunemployment, poor schooling, and an undergroundeconomy that evolved into crack cocaine, gangs, andcrime. Yet some neighborhood activists argued that theredlining, predatory lending, and housing speculationwere worse threats to community viability. In the early1990s, the combination of low property values, renewedaccess to capital, and neighborhood reinvestmentresulted in gentrification, displacement, and racialtransition. Portland is an exemplar of an urban realestate phenomenon impacting Black communitiesacross the nation.

KEYWORDS: community, segregation, disinvest-ment, gentrification, inequality

This was really part of much, much larger forcesthat are at work, and they may or may not be con-sciously malicious . . . This is the result of city pol-icy, of other kinds of large-scale things thatsystematically cripple or dismember a community.Some neighborhoods are “fed.” Others are bled.

—Paul Bothwell, Boston Dudley Street neighborhood activist1

The preponderance of scholarship on Portland, Oregon,analyzes the city’s achievements in various fields ofurban and regional planning: land use, environment,transportation, central city revitalization, and civicinvolvement (Ozawa 2004; Abbott et al. 1994). Othersdebate the impact of the urban growth boundary,designed to limit sprawling development, on housingprices (Downs 2002; Fischel 2002; Howe 2004).However, very little scholarship analyzes the experienceof Portland’s Black community in this relatively remoteNorthwest city. Although the population is very small(never comprising more than 7 percent of the city and 1 percent of the state), Portland provides an interestingcase study of a Black community that found itself sud-denly in the path of urban redevelopment for “higherand better use” after years of disinvestment. The occu-pation of prime central city land in a region with anurban growth boundary and in a city aggressively seek-ing to capture population growth, coupled with an eco-nomic boom, resulted in very rapid gentrification andracial transition in the 1990s. As cities across the coun-try increasingly seek to improve land values and woo themiddle and upper classes back to the central cities as aneconomic development strategy, the fate of urban Blackcommunities is uncertain. Local policy makers are grap-pling with ways to reduce the negative effects of sprawl-ing development patterns, and the conversion of centralcity land into residential use offers a solution, especiallyas baby boomers and their children leave suburbia forcompact inner-city living. It is critical to understand thelinks between the historical processes of urban develop-ment and contemporary forces that impinge on Blackcommunities, so that central city residents might proac-tively engage with these forces. This work contributes tothat effort by shedding light on the link between disin-vestment and gentrification in Portland.

This is a case study analysis of the historical processof segregation and neighborhood disinvestment that pre-ceded gentrification in Portland’s Black community,Albina. Drawing upon various sources such as censusdata from 1940 to 2000, oral histories, archival docu-ments, and news articles, it investigates the mechanismsthat facilitated residential segregation and housing disin-vestment. It also traces some of the Black resistancestrategies to these mechanisms. Only after pressure from

Karen J. Gibson is an associate professor of urban stud-ies and planning at Portland State University. Herresearch interests concern racial economic inequality inthe urban context, housing and urban policy, and thetheory and practice of community development. She isinterested in interdisciplinary approaches to under-standing urban life, and applied research. She holds anM.S. in public management and policy from CarnegieMellon University and a Ph.D. in city and regional plan-ning from the University of California at Berkeley.

4 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

activists and the media did politicians, seeking votes,respond to the needs of Albina. The real estate industry(government housing officials, Realtors, bankers,appraisers, and landlords), by denying access to conven-tional mortgage loans, played a pivotal role in perpetu-ating the absentee ownership and predatory lendingpractices that fueled the decline in housing conditions.Many Black residents were denied the opportunity toown homes when they were affordable. Even after Whiteflight from Albina in the 1950s and 1960s, Black homeownership continued to be restricted by discriminatorymortgage lending policies in the 1970s and 1980s, caus-ing some to search elsewhere for ownership opportuni-ties. During the 1990s, residential segregation betweenBlacks and Whites in Portland decreased so sharply thatit ranked tenth nationally among metropolitan areas withthe greatest declines (Frey and Meyers 2005). Ironically,although desegregation partly reflects the gradual open-ing up of the housing market, it also reflects the dis-placement of Black renters to suburban locations becauseof gentrification. In 2000, the African American homeownership rate in the city of Portland was just 38 percent,well below the national average of 46 percent. Recentlythe city, which has done a fairly good job of producinglow-income housing, began trying to remedy the racialdisparity in home ownership. While there are positiveaspects to the revitalization of Albina neighborhoods,many Black residents wonder why it did not happen ear-lier, when it was their community. Portland is lauded forits livability—but livability for whom?

RESIDENTIAL SEGREGATION AND HOUSINGDISINVESTMENT PROCESSES

The emergence of the black ghetto did not happenas a chance by-product of other socioeconomicprocesses. Rather, white Americans made a seriesof deliberate decisions to deny blacks access tourban housing markets and to reinforce spatial seg-regation. Through its actions and inactions, whiteAmerica built and maintained the residential struc-ture of the ghetto.2

Economic disinvestment—the sustained andsystemic withdrawal of capital investment from thebuilt environment—is central to any explanation ofneighborhood decline.3

This study traces the simultaneous processes of racialresidential segregation and disinvestment in Portland,Oregon. While the scale of segregation has been verysmall relative to large cities in the Midwest andNortheast, the consequences for residents are similar.Segregation is a tool of social and economic control thatoperates by confining Black citizens to a designatedsection of the city. Early sociologists labeled such areas

the “Black Belt” or the “ghetto.” Sociologist St. ClairDrake and anthropologist Horace Cayton were prescientin their analysis of the White rationale for segregationin their classic study of Chicago’s South Side, BlackMetropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City:

Midwest Metropolis seems to say: “Negroes have aright to live in the city, to compete for certain types ofjobs, to vote, to use public accommodations—butthey should have a community of their own. Perhapsthey should not be segregated by law, but the cityshould make sure that most of them remain within aBlack Belt.” As it becomes increasingly crowded—and “blighted”—Black Metropolis’s reputationbecomes ever more unsavory. The city assumes thatany Negroes who move anywhere will become a focalpoint for another little Black Belt with a similar repu-tation. To allow the Black Belt to disintegrate wouldscatter the Negro population. To allow it to expandwill tread on the toes of vested interests, large andsmall, in contiguous areas. To let it remain the samesize means the continuous worsening of slum condi-tions there. To renovate it requires capital, but this is apoor investment. It is better business to hold the landfor future business structures, or for the long-talked-of rebuilding of the Black Belt as a White office-workers’ neighborhood. The real-estate interestsconsistently oppose public housing within the BlackBelt, which would drive rents down and interfere withthe ultimate plan to make the Black Belt middle-classand White. [Drake and Cayton 1945:198, 211]

The mechanisms or “compulsions” by which citiesacross the United States ensured that Black peoplestayed in their place were articulated by housing scholarand advocate Charles Abrams (1955), in ForbiddenNeighbors: A Study of Prejudice in Housing:

1. Physical compulsion through bombs, arson, threats,mobs

2. Structural controls such as walls, fences, dead-endstreets

3. Social controls such as segregation in clubs, schools,and public facilities

4. Economic compulsions such as refusal to makemortgage loans, Realtors’ codes of ethics, andrestrictive covenants

5. Legalized compulsions that use the powers of gov-ernment to control the movements of minorities suchas condemnation powers, urban renewal, and slumclearance.

Various forms of these compulsions, including the physi-cal threats such as cross-burnings, were used to restrictBlack housing choice in Portland. Rose Helper, in heroriginal book, Racial Policies and Practices of Real

KAREN J. GIBSON 5

Estate Brokers (1969), details how Realtors used their“code of ethics” to put into practice the “racial real estateideology” that property values decline when Black peoplelive in White neighborhoods. This was the official word ofthe American Institute of Real Estate Appraisers, whichmaintained that “the clash of nationalities with dissimilarcultures” contributed to the “destruction of value” (Helper1969:201). Realtors, lenders, and government guarantorswidely promoted the use of restrictive covenants (mutu-ally agreed upon by builders, Realtors, bankers, apprais-ers, insurers, and residents) that forbade non-Whites toown property in specific areas. Residential segregationholds the power to mold, stigmatize, and harm the livingenvironment of a people. This does not imply that“ghetto” residents are passive victims, or that they arepathological, as some strands of urban theory suggest.

Neighborhood disinvestment involves the system-atic withdrawal of capital (the lifeblood of the housingmarket) and the neglect of public services such asschools; building, street, and park maintenance;garbage collection; and transportation. The classicalecology theories of Chicago School sociologyexplained neighborhood growth and decline as a natu-ral life cycle that unfolded in stages: rural, residentialdevelopment, full occupancy, downgrading, thinningout, and then either crash or renewal (Park et al. 1984).Downgrading is associated with the outflow of originalresidents and inflow of lower-income residents andoften corresponds with racial segregation. The housingages, rents fall, and often there is overcrowding thatalso hastens dilapidation of the stock. Residents moveout (if they can), and the neighborhood becomes aslum. While this interpretation is helpful for under-standing the stages of neighborhood change, it does notadequately explain why such changes occur, as it lacksa discussion of capital, space, race, class, and power.

Scholars with a more critical approach analyzeneighborhood decline by emphasizing the profit-takingof Realtors, bankers, and speculators, which systemati-cally reduces the worth or value of housing in a processcalled devalorization (N. Smith 1996). The devaloriza-tion cycle has five stages: new housing construction andfirst cycle of use, transition to landlord control, block-busting, redlining, and abandonment. After new housingages, owners move elsewhere, sometimes to avoid thecost of repair, and the neighborhood has more rentersthan owners. During the second stage, absentee land-lords may choose to profit off of the rent and decide notto make repairs. Depending on the market, it may beeconomically rational to under-maintain the property.The transition to landlord control may or may notinclude the third stage, blockbusting, but often involvesa process of racial succession, or rapid populationturnover. Blockbusting is the process by which Realtors

use the fear of racial turnover and property value declineto induce homeowners to sell at below-market prices.Then the Realtor sells the property at inflated prices toBlack (or other) home buyers. The fourth stage is whenbanks redline the neighborhood; this reduces owneroccupancy and often prevents absentee landlords fromselling a property they no longer want to keep. At thispoint, home ownership rates decline, and the downwardtrajectory of dilapidation continues until the final stage:abandonment. This is often accompanied by arson asproperty owners seek to cash out through fire insurance.Gentrification is the recycling of a neighborhood up tothe point at which property values are comparable tothose in other neighborhoods. If a developer can pur-chase a structure in an area, rehabilitate it, make mort-gage and interest payments, and still make a return onthe sale of the renovated building, then that area is ripefor gentrification. The cost of mortgage money is animportant economic factor affecting the feasibility ofreinvestment. This process occurs at the level of theneighborhood, not individual structures, and requires theinvolvement of housing market actors at the institutionalscale. It also involves redlining motivated by appraisalsthat devalue African American neighborhoods. Whenthe public and private sectors make a decision to disin-vest, it is essentially proclaiming an area unworthy andensuring its decline. In this view, gentrification is notjust a matter of individual preferences for older centrallylocated neighborhoods; it is a matter of financial andgovernmental decisions. When capital is withheld fromcertain areas, predatory lenders move in to fill the void.

Historian Kenneth Jackson (1985) described thefederal role in urban disinvestment on a mass scalethrough housing and transportation policies that sup-ported massive suburbanization after World War II.Inner-city neighborhoods were systematically deemedunworthy of federally insured home loans by real estateappraisers, because they were destined for decline bytheir heterogeneous populations and mixed land-use pat-terns (residential, commercial, and industrial). When thefederal government took the lead in proclaiming oldercentral-city neighborhoods ineligible for investment,local government and private sector actors followed.Jane Jacobs (1961), a fierce critic of urban redevelop-ment schemes, argued that the policy of denying loans tourban neighborhoods because they were declining was aself-fulfilling prophecy. Housing dilapidation and aban-donment are key indicators of poverty concentration in“underclass” neighborhoods (Jargowsky and Bane1991). Abandonment almost always occurs simultane-ously with tax delinquency: defraying the tax burden isone way to milk a property (Sternlieb and Burchell1973). Perhaps the absolute final method of cashing inon property is through purposeful arson for insurance

6 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

payoffs. Arson was an almost nightly occurrence in theDudley Street neighborhood of Roxbury in Boston,Massachusetts (Medoff and Sklar 1994).

In Portland, there is evidence supporting the notionthat housing market actors helped sections of the AlbinaDistrict reach an advanced stage of decay, making the arearipe for reinvestment. Critical to the process was the sys-tematic denial of mortgage capital, which was justified byappraisals that devalued African American neighbor-hoods. In addition, predatory lenders, speculators, andslumlords played a strong role in keeping Albina residentsfrom accumulating wealth through home ownership and,in some cases, cheated residents out of their equity invest-ments and earnings. Since home ownership is the mostcommon form of wealth, this helped to perpetuate eco-nomic inequality in Portland (Oliver and Shapiro 1997).

As the Portland economy rebounded from a reces-sion during the early 1990s, Albina became ripe forgentrification. Gentrification involves reinvestment inhousing and commercial buildings, as well as infra-structural amenities such as transportation, street trees,signage, and lighting. It includes the movement ofhigher-income residents into a neighborhood and ofteninvolves racial transition. It requires financial investmentin the built environment until property values are compa-rable to those of other neighborhoods, and it is an insti-tutional, rather than individual-scale, process (N. Smith1996). In other words, it is not just a cultural or socialphenomenon reflecting a lifestyle trend—it reflects sys-tematic reinvestment by financial institutions and thepublic sector. In Portland, the Black community wasdestabilized by a systematic process of private sectordisinvestment and public sector neglect. After the presspublicized the discriminatory lending practices ofOregon bankers, the city put pressure on them to reversetheir policy. Financing became available at the sametime that the economy was improving. In addition, bythe mid-1990s, several nonprofit housing organizationshad helped to improve Albina neighborhoods by devel-oping new housing and rehabilitating tax-foreclosedproperties. Combined with more aggressive buildingcode enforcement and the creation of a huge urbanrenewal district and light-rail project on InterstateAvenue, the area was primed for reinvestment. The gapbetween the value of properties and what they couldpotentially earn was large enough for speculators to lineup to buy tax-foreclosed properties in Albina.

THE ALBINA DISTRICT

Oregon was a Klan state—it was as prejudiced asSouth Carolina, so there was very little differenceother than geographic difference.

—Otto Rutherford, community leader, 1978

We were discussing at the [Portland] Realty Boardrecently the advisability of setting up certain dis-tricts for Negroes and orientals.

—Real Estate Training Manual, 19394

Albina was a company town controlled by the UnionPacific Railroad before its 1891 annexation to Portland(MacColl 1979). This area is located within walking dis-tance of Union Station, on the east side of the WillametteRiver. Since the vast majority of Blacks, prior to WorldWar II, worked for the railroad as Pullman porters, thosewho stayed settled near the station. Before the GreatDepression, there was a small Black community in north-west Portland, with Black-owned businesses such as cafés,barbershops, and the Golden West Hotel, but most did notsurvive the Depression. Around 1910, they were pushedout of that community to the east side, according to EddieWatson, who said, “As the town began to grow theyswitched us out” (Watson 1976). Black Portlanders hadbuilt the Mt. Olivet Baptist Church in Albina at the turn ofthe century. Because they were such a tiny fraction of thecity’s population (less than 1 percent) and many lived scat-tered about, Black Portlanders often spent time together atchurch, one of the few social functions available. Thissmall community was well educated and primarily middleclass, and about half were homeowners. But by 1940, halfof Black Portland was confined to the Williams Avenuearea in Albina as a result of severe housing discrimination(Pearson 1996; McElderry 2001). Residential segregationreflected the prejudice and discrimination Black people inOregon had faced for more than a century, both by customand by law. The Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850promised free land to White settlers only. Many of the set-tlers preferred this territory because slavery was not per-mitted by law, and therefore they would not faceeconomic competition from slaveholders. In 1857, bypopular vote, Oregon inserted an exclusion clause in thestate constitution that made it illegal for Black people toremain in the state. This clause was not removed until1926. Oregon was one of only six states that refused toratify the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution,which gave Black people the rights of American citizen-ship and Black men the right to vote (McLagan 1980).

The hostile racial attitude of White Oregonians man-ifested in Portland’s built environment through real estatepractices. In 1919, the Portland Realty Board adopted arule declaring it unethical for an agent to sell property toeither Negro or Chinese people in a White neighborhood.The Realtors felt that it was best to declare a section ofthe city for them so that the projected decrease in prop-erty values could be contained within limited spatialboundaries. Historian Stuart McElderry (2001) peri-odizes the process of “ghetto-building,” finalized by1960, in three phases: 1910 to 1940, the 1940s, and the

KAREN J. GIBSON 7

1950s. First, between 1910 and 1940, more than half theBlack population of 1,900 was squeezed into Albina bythe real estate industry, local government, and privatelandlords, who restricted housing choice to an area twomiles long and one mile wide in the Eliot neighborhood.The second phase occurred in the 1940s, when roughly23,000 Black workers who migrated to Portland for workin the shipyards were restricted to segregated sections ofdefense housing developments in Vanport and Guild’sLake and to the Eliot and Boise neighborhoods in theAlbina District. During the third phase, in the 1950s,when defense housing was demolished by flood and

bulldozer, Blacks were funneled into the Albina District.(Vanport, the largest wartime development in the nation,was flooded when the dike holding back the ColumbiaRiver broke.) As Blacks moved in, Whites moved out.Between 1940 and 1960, the Black population in Albinagrew dramatically, while the White population shranksignificantly as more than 21,000 left for the suburbs orother Portland neighborhoods.

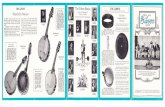

This study focuses on the neighborhoods in theAlbina District that were at least 35 percent Black in1970 (see Figure 1). The Albina District includes all orpart of eight neighborhoods (ten census tracts) that form

Figure 1. Albina District neighborhoods in Portland, Oregon.

Lower and Upper Albina, which are distinguished bothby their location (south or north of Fremont Street) andby the point in time that each was the center of the Blackcommunity.5 During the 1940s and 1950s, the Blackcommunity was centered in Lower Albina, which con-sists of three neighborhoods: Eliot, Irvington, and Lloyd.During the late 1960s and early 1970s, urban renewal andfreeway construction forced residents to relocate north-ward, above Fremont Street, into Upper Albina. UpperAlbina consists of five neighborhoods: Boise, Humboldt,King, Sabin, and Woodlawn. In the first period, the Eliotneighborhood was the focal point; in the 1970s it wassucceeded by the King (formerly Highland) neighbor-hood, which remains the center to this day. Table 1 showsthe point at which the Black population in each neigh-borhood peaked, as indicated by bold print. Note thatEliot was the largest neighborhood, both in populationand geographic area, and it therefore consists of threecensus tracts. While Black residents comprised at least43 percent of these neighborhoods at some point in thepostwar period, Portland’s Black population has neverbeen greater than 7 percent, and Oregon’s Black popula-tion has never been greater than 2 percent.

Although it is helpful to distinguish Lower andUpper Albina in order to understand the patterns ofsettlement and resettlement and the changing shape ofthe community, the name Albina is synonymous with theBlack community in Portland. By 1960, four of fiveBlack Portlanders lived in this 4.3-square-mile area, andby 1980, despite the opening up of housing markets, oneof two still did. By 2000, slightly fewer than one of threeBlack Portlanders lived there, and while many Black

Portlanders appreciate the physical improvements asso-ciated with the recent neighborhood revitalization, theyalso lament the loss of community that has come with it.

Of course it’s nice and fixed up now, and the crimerate is down. We wouldn’t want to have it the otherway. But everyone wants home. Where is our placethen? People know where they want to live if theirculture is represented there. If a certain kind of per-son looks at Hawthorne, they know that’s where theycan be to feel comfortable. But our culture is scat-tered everywhere. It used to be that living “far out”was 15th and Fremont. Now it’s 185th and Fremont.A lot of people leave the neighborhood because theyfeel they’re leaving something that’s not theirs any-more anyway. It will never be that way again. There’sa lot of sadness. For a lot of us, it’s just too hard tostay and watch your history erased progressivelyover time. There are just too many ghosts.

—Lisa Manning, Albina resident6

ALBINA COMMUNITY FORMATION, 1940–1960

At that time it was almost impossible to buy propertyanywhere other than around Williams Avenue . . .Portland was really a very prejudiced city.

—Maude Young, 1976

The formation of the Black community in the AlbinaDistrict was shaped by two major events: the labormigration during World War II and the 1948 flooding ofVanport City, the largest single wartime development in

8 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

Table 1. Black population trends in Albina District neighborhoods, 1960–2000.

Percent Black

Census Tracts 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Lower Albina

Eliot 22.01 69 50 35 38 5822.02 72 54 43 41 2523.01 65 77 62 58 41

Irvington 24.01 14 43 38 33 23Lloyd 23.02 54 45 28 25 20

Upper AlbinaBoise 34.02 67 84 73 70 50Humboldt 34.01 40 65 69 69 52King 33.01 21 61 63 63 54King-Sabin 33.02 31 62 64 58 43Woodlawn 36.01 12 36 49 62 51

Note: Bold figures indicate when the Black percentage peaked. Irvington refers to western half of the neighborhood. Only asmall part of Sabin is within the eastern census boundary at NE 15th Avenue, and a tiny portion of the Vernon neighborhood isin the study area, so it is not included.Source: Author’s calculations from United States Census Bureau Decennial Census, Summary File 3.

KAREN J. GIBSON 9

Table 2. Black population growth in west coast cities, 1940–1950.

San SanYear Los Angeles Oakland Francisco Diego Seattle Portland

1940 63,774 8,462 4,846 4,143 3,789 1,9311950 171,209 47,562 43,502 14,904 15,666 9,529

Percent Increase 169% 462% 798% 260% 314% 394%

Source: In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528–1990. Quintard Taylor, New York:W.W. Norton, 1998.

the United States and Oregon’s second-largest city(Pancoast 1978). The migration, which temporarilycreated a tenfold increase in the Black population dur-ing the war years, meant that Portland had to face thequestion of housing. Although city leaders stubbornlyresisted the development of any publicly subsidizedhousing, defense or otherwise, the attack on PearlHarbor in December 1941 made it a patriotic duty tohouse defense workers, at least temporarily. Within afew months, “Magic Carpet Specials” brought the firsttrainloads of roughly 23 thousand African Americansand 100 thousand Whites, mostly from the South, tohelp with the Pacific war effort. Shipyards in Portlandboomed with activity, as did five other major WestCoast cities: Seattle, San Francisco, Oakland, LosAngeles, and San Diego. Black migrants came for theopportunity to work, and many chose to remain afterwar. The fact that more chose to leave Portland thanany other West Coast city reflected its “national repu-tation among blacks of being the worst city on the WestCoast, as bad as any place in the South” and dismal post-war employment prospects (Pancoast 1978:48; Taylor1998). In Portland, after the war, there was little work, ahousing shortage, and open hostility to the newcomers(both Black and White). The peak Black population in1945, estimated at 23 thousand to 25 thousand, fell bymore than half by 1950. Table 2 shows that Portland’sBlack population was the smallest of the six coastalcities, both before and after the war. Meanwhile, LosAngeles and Seattle continued to attract migrants, andSan Diego and San Francisco saw their populationsincrease modestly (Taylor 1998). A field report issued bythe National Urban League, “The West Coast and theNegro,” predicted that after the war, the region wouldhave “a stranded population on its hands” because ofemployment and housing discrimination, as well as resi-dency restrictions on relief assistance (Johnson 1944:22).

Black workers faced various forms of racial dis-crimination in both ship building (all cities except SanDiego) and aircraft production (San Diego, LosAngeles, Seattle). In 1942, workers from New York Cityprotested unequal working conditions at the KaiserCompany in Portland, claiming to have been recruited

under the “false pretense” of equal rights to jobs andtraining (Pancoast 1978:41). The struggle for equalemployment opportunity in West Coast shipyards lastedthroughout the war. Black workers who refused to jointhe Boilermakers’ segregated union auxiliaries were firedby the hundreds in Portland and Los Angeles. Forminggroups such as the Shipyard Negro Organization forVictory (with 600 members in 1943), and organizingalong with the NAACP, churches, Black newspapers, andother local leaders, those workers pressured the FederalEmployment Practices Commission to rectify this indig-nity. Despite their efforts, the AFL Boilermakers Union,which covered two-thirds of all shipyard workers in thenation (6,600 in Portland and 7,200 in Los Angeles),never complied with the federal ruling to integrate theunion locals (A. Smith and Taylor 1980).

Vanport is now housing many of the colored peo-ple. They will undoubtedly want to cling to thoseresidences until they can get something better. Nosection of the city has yet been designated as a col-ored area which might attract them from Vanport.

—W. D. B. Dodson, Chamber of Commerce, 19457

Housing was also a critical arena of racial conflictall along the West Coast, and defense housing, builtwith federal dollars, was little different. Black migrantswere more likely to depend on public housing thanwere Whites, and “shipyard ghettos” were created inSan Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, and Portland(Johnson 1944; Taylor 1998:268). During the 1940s, theHousing Authority of Portland (HAP) built and/or man-aged more defense housing than did any other city inthe nation (18,000 units). Unlike Seattle’s housingauthority, which integrated defense housing, HAPrestricted Black families to certain developments: the vastmajority was housed in segregated sections of Vanport(6,000 residents) and Guild’s Lake (5,000 residents), bothof which were located outside of the city’s residentialareas. Vanport was hurriedly built in 1942–43 on marsh-land, and Guild’s Lake was built on industrial land. Afterthe Kaiser shipyards closed in 1945, many Black familieswho could not crowd into Albina, either due to lack of

10 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

resources or the inability to find housing, remained inVanport and Guild’s Lake. Comprising more than one-third of Vanport’s population, Black residents organizedthe Vanport Tenants League to demand integrated housingand fair treatment from HAP and the police (McElderry1998). HAP and city officials were eager to dismantle thetown, calling it “troublesome” and “blighted” because ofthe racially mixed population and “crackerbox” housingconstruction (MacColl 1979:595). On Memorial Day1948, a dike at the Columbia River broke and floodedVanport. It killed 15 people and displaced more than5,300 families, roughly 1,000 of them Black (McElderry1998). Yet the flood that washed away Vanport did notsolve the housing problem—it swept in the final phase of“ghetto building” in the central city.

After this disaster, thousands of residents lived intemporary trailers and barracks on the industrial land ofSwan Island and Guild’s Lake, some for as long as fouryears. Hundreds of Black and White families werestranded without employment or decent housing duringthis time. While there was some tension between theolder Black residents and the newcomers, housing dis-crimination affected them both. During this decade, thepattern of racial transition in Albina neighborhoods thatwould last 50 years was first established: almost incheckerboard fashion, when Black residents settled in,White residents would move out. This pattern repeateditself within the eight neighborhoods of the AlbinaDistrict until the early 1990s. Between 1940 and 1950,the entire Black population of Portland increased by7,500 residents; about half of these crowded into theestablished Black community along Williams Avenue inLower Albina. Whites migrated out, causing Blacks toincrease proportionately to roughly one-third of thepopulation. At this time, the Urban League of Portland,an interracial social agency, became active in improvingemployment and housing opportunities in Portland. In1945, Dr. DeNorval Unthank, a physician and commu-nity leader, provided office space for Portland’s newUrban League branch. Bill Berry, the first executivedirector, had been recruited from Chicago for a specificpurpose, according to Shelly Hill, the League’s firstemployment specialist: “The president of First NationalBank, who was an Urban League member, told this newhire, ‘We need a good intelligent Negro to tell thesepeople to go home.’” But Berry responded that he had“the wrong person,” because Berry’s job was “to makePortland a place people can stay in” (Hill 1976).

MAKING ALBINA HOME

The flood washed out segregation in housing inVanport. That is when the real estate board decidedthat it would sell housing to Negroes only between

Oregon Street which is the Steel Bridge andRussell from Union to the river. Later theyexpanded it to Fremont so they had no choice inbuying a home; these were the only ones available.

—Shelly Hill, 1976

During the 1950s, Albina lost one-third of its popula-tion and experienced significant racial turnover asWhite residents left en masse for the suburbs and Blackresidents moved into Albina from temporary war hous-ing. By decade’s end, there were 23,000 fewer Whiteand 7,300 more Black residents (total population was31,510). Lower Albina grew from one-fifth to one-halfBlack, and Upper Albina increased from less than one-20th to nearly one-third Black. As soon as it was polit-ically feasible in the early 1950s, HAP closed theremaining Guild’s Lake and Swan Island housingdevelopments, where former shipyard workers stillremained and Vanport residents had found shelter afterthe flood. HAP refused to provide any public housingalternatives, so Black residents were channeled andcompressed into Albina. Despite the protests of con-cerned citizens, both Black and White, Portland, likeother northern cities, responded to its growing Blackpopulation by confining them to “crowded, ancient,unhealthy and wholly inadequate” housing (City Clubof Portland 1957:358). The City Club (a research-based civic organization established in 1916), in itsrole as a watchdog over civic issues, reflects the pro-gressive, reformist tradition of Portland’s citizenry.The 1957 report “The Negro in Portland: A ProgressReport, 1945–1957” documented what was generallyunderstood: 90 percent of Realtors would not sell ahome to a Negro in a White neighborhood. The reportdrew attention to the contradiction between the OregonApartment House Association’s claim that 1,000 hous-ing vacancies existed and the “known scarcity of apart-ment space for Negroes” (City Club of Portland1957:361). Dr. Unthank, the only Black member of theCity Club, who 20 years earlier had protested the lackof public housing alternatives which forced residents tolive in substandard housing, criticized the reticence ofHAP to build public housing in the face of a severehousing shortage. But HAP and Portland Realtors, liketheir national counterparts, had two major reasons forrefusing to integrate neighborhoods. First, they main-tained that because “Negroes depress property values,”it was unethical to sell to them in a White neighbor-hood; and second, if they “sell to Negroes in Whiteareas, their business will be hurt” (City Club ofPortland 1957:359). In addition, citizens activelysought out restrictive covenants to prevent any non-Whites from buying homes in their neighborhoods.City planners tended to locate urban redevelopment

KAREN J. GIBSON 11

projects in the neighborhood niches Blacks had estab-lished for themselves, causing residents great disruptionand often relocating the same families more than once.

While racial discrimination was deeply institution-alized in a variety of arenas, Black Portlanders had along history of fighting against it. After decades ofstruggle, the 1950s brought success in three areas: pub-lic accommodations, housing, and employment. OfWest Coast cities, Portland was noted for its segregatedrestaurants, movie theaters, hotels, and amusementparks. Within three blocks of the Union Station, therewere 13 signs that read “We cater to white trade only.”Shelly Hill said, “The only way we got them down wasby threatening them” (Hill 1976). Veterans returningfrom World War II broke out windows that displayedthese signs, and the Negro Taxpayers’ League organizedto boycott those who would not serve them and frequentthe places that would. The Portland branch of theNAACP, the oldest branch on the West Coast, haddrafted the first public accommodations bill in 1919;the bill finally passed the legislature in 1953. OttoRutherford, then president of the NAACP, said thatthere had to be “some funerals” before the bill couldpass, meaning that members of the opposition literallyhad to grow old and die before they could get theneeded votes (Tuttle 1990). Rutherford’s parents hadowned a café and barbershop in northwest Portland. Hedescribed one of the ways Blacks got around barriers tohome ownership: since a 1926 state law said that “noNegro or Oriental could buy property,” his “dad anduncle had a white attorney who would buy the propertyand sell it to them” (Rutherford 1978). In 1959, a FairHousing Law that forbade discrimination in the sale,rental, or lease of housing passed the state legislature.In 1961, the League of Women Voters conducted a sur-vey in integrated neighborhoods to evaluate the appli-cation of the Fair Housing Law. Black residents tendedto be more educated than did their White neighbors.Four out of five said they had experienced housing dis-crimination. One Black family claimed that the inabil-ity to buy homes was compounded by employmentdiscrimination: “There is a problem of fair and adequateemployment . . . if there was adequate employment, aNegro could purchase the kind of house he wants”(League of Women Voters 1962).

In 1949, Oregon passed the Fair EmploymentPractices Act in response to pressure from a coalition ofveterans, churches, and labor unions (Hill 1976). Thisact was an improvement over a previous version of thebill, which contained no enforcement provisions.During the 1950s, Shelly Hill, representing the UrbanLeague, was instrumental in helping Blacks gain theirfirst employment opportunities in state and local gov-ernment, local newspapers, private companies, “the

professions,” and local colleges. The Urban League suc-ceeded in getting more than 180 employers to hireBlack workers. Portland’s waterfront remained segre-gated until 1964, when the Longshoremen’s andWarehousemen’s Union accepted Black workers(Bosco-Milligan Foundation 1995).

Yet it was difficult for residents, regardless of race,to save their neighborhoods from the steady march ofprogress embodied in the urban renewal bulldozer. Incities across the nation, urban power brokers, with thehelp of the federal government, eagerly engaged incentral-city revitalization after World War II. Luxuryapartments, convention centers, sports arenas, hospi-tals, universities, and freeways were the land uses thatreclaimed space occupied by relatively powerless resi-dents in central cities, whether in immigrant White eth-nic, Black, or skid row neighborhoods. In 1956, votersapproved the construction of the Memorial Coliseumin the Eliot neighborhood, which destroyed commercialestablishments and 476 homes, roughly half of theminhabited by African Americans. The Federal AidHighway Act of 1956 made funds available to citiesacross the nation to whisk suburban residents to andfro. As a result, several hundred housing units weredemolished in the Eliot neighborhood to make way forInterstate 5 and Highway 99, both running north/souththrough Albina. Displaced residents relocated in anortheasterly direction, above Fremont Street andtoward Northeast 15th Avenue. Many crowded intoolder housing in the Boise and Humboldt neighbor-hoods, becoming more racially isolated from Whites.The Housing Act of 1957 gave cities the tools theyneeded to achieve the national goal of clearing slums,and local officials used them by systematically deem-ing Black neighborhoods “blighted” and in need ofrevitalization. Thus, not long after Black Portlandersgot settled in Lower Albina, city leaders were makingplans to convert the land, which was the heart of theircommunity, into commercial, industrial, and institu-tional uses. The following statement, from Portland’sapplication for federal urban renewal funds, is typicalof the justifications for renewal employed by citiesacross the country:

There is little doubt that the greatest concentrationof Portland’s urban blight can be found in theAlbina area encompassing the Emanuel Hospital.This area contains the highest concentration oflow-income families and experiences the highestincidence rate of crime in the City of Portland.Approximately 75% to 80% of Portland’s Negropopulation live within the area. The area containsa high percentage of substandard housing and ahigh rate of unemployment. Conditions will not

Fig

ure

2.R

usse

ll an

d W

illia

ms

Ave

nues

,196

2.T

his

inte

rsec

tion

was

the

hea

rt o

f Alb

ina’

s B

lack

com

mun

ity

unti

l the

cit

y de

clar

ed t

he a

rea

blig

hted

an

d to

re it

dow

n.T

he b

lock

whe

re t

he d

rug

stor

e,sh

ops,

and

hous

ing

once

sto

od n

ow c

onta

ins

a pa

tch

of g

rass

.Ore

gon

His

tori

cal S

ocie

ty.

12 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

KAREN J. GIBSON 13

improve without a concerted effort by urbanrenewal action. The municipal goals as establishedby the Community Renewal Program for the City ofPortland further stress the urgent need to arrest theadvanced stages of blight. (Portland DevelopmentCommission 1966:17)

Albina residents organized, seeking to remedy theproblem of aging and declining housing conditionsthrough rehabilitation, not clearance. While theywould have some success north of Fremont Streetthrough the Albina Neighborhood ImprovementProgram (1961–73), Black residents would lose theirown “Main Street” at the junction of Russell andWilliams Avenues (see Figure 2).

RESHAPING THE COMMUNITY, 1960–80

When you get to feeling locked in—that’s when thefrustrations start.

—Frank Fair, Youth Worker, Church CommunityAction Program, 1967 (Bosco-Milligan

Foundation 1995:95)

[Albina] could be not only one of the most accessi-bly convenient areas of the city, but one of the mostprogressive and innovative neighborhoods as well.(City of Portland Model Cities 1969:2)

During the 1960s, Portland’s African American popula-tion, although small relative to those in larger cities,was experiencing the same problems associated withracial discrimination and spatial segregation found else-where: high unemployment and occupational segrega-tion, poverty, overcrowded and low-quality housing,segregated schools, and tension with police. It seemsthat the relationship between the Albina community andcity agencies could be characterized by extremes ofabsolute neglect and active destruction. At times whenresidents resisted, they got some cooperation and supportfrom the city, but ultimately they could not trust that ithad their best interests at heart. Redevelopment policieswere a source of deep conflict during the 1960s and1970s. Albina’s total population shrank by about 5,000,and neighborhoods experienced more racial transition,but this time most significantly in Upper Albina. Albina’sWhite population dropped by nearly 8,000 residents,three-quarters from Upper Albina, as Black residentsdisplaced from Lower Albina moved there. Some fledthe area because of the increased anger of Black resi-dents, which exploded into riots in 1967 and 1969. TheEmanuel Hospital project, a classic top-down planningeffort, destroyed the heart of the Black community inLower Albina during the late 1960s, shifting andexpanding it toward the northeast.

More than 11 hundred housing units were lost inLower Albina, and the Black population in Eliot shrankby two-thirds. Businesses along Williams Avenue suchas the Blessed Martin Day Nursery, the Chat and ChewRestaurant, and Charlene’s Tot and Teen Shop (alreadyrelocated from the Coliseum area) were decimated tomake way for the hospital (Bosco-Milligan Foundation1995). By the end of the decade, the center of the Blackcommunity was relocated to a contiguous set of neigh-borhoods (King, Boise, and Humboldt) in an area of nomore than two and a half square miles, bounded byFremont and Killingsworth Avenues on the south andnorth and by Mississippi and Northeast 15th Avenueson the east and west. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard(formerly Union Avenue) ran straight up the middle, andthe largest neighborhood, King, became the center. TheBlack presence had tripled in the Irvington, King, andWoodlawn neighborhoods, making Blacks the majoritygroup in Albina. The Boise neighborhood was the mostsegregated: Black residents comprised 84 percent of itspopulation, but just 6 percent of the city’s total popula-tion. Among the six West Coast cities, segregationbetween Blacks and Whites in Portland was second onlyto that in Los Angeles (Sorensen and Taeuber 1975).

Black leaders, after their experience with urbanrenewal in the 1950s, devised strategies to protect, pre-serve, and enhance their neighborhoods. In 1960,Mayfield Webb, NAACP president and attorney, alongwith clergy and other activists, resisted the CentralAlbina Plan, a proposal to clear the entire area belowFremont Street from the interstate to Martin LutherKing Jr. Boulevard (Bosco-Milligan Foundation 1995).They secured a commitment from the city to invest inhousing and neighborhood improvements in the areaabove Fremont Street, where the Black home ownershiprate was roughly 60 percent. The Albina NeighborhoodImprovement Program (ANIP) brought neighborstogether in a 35-block area, where they rehabilitatedmore than 300 homes and built a park named afterDr. Unthank (see Figure 3). Meanwhile, citizens peti-tioned the city to extend ANIP activities below FremontStreet and to change the city’s plan to renew the area,but city commissioners refused. The Emanuel Hospitalproject was in motion and could not be stopped. Thecity expected to site a federally supported veterans’ hos-pital there, and this justified clearance of a massive landarea (76 acres). After the heart of the Black communitywas demolished, the federal project fell through, andlarge swaths of land lay vacant decades after the renova-tion of Emanuel Hospital. This was a particularly bitterpill to swallow for those who had seen the heart of theirneighborhood destroyed. Jobs promised by the hospitalnever materialized (see Figure 4). During this decade,Eliot residents were also relocated for construction of

the school district’s central office and the city’s waterbureau. Nearly four decades later, a Black resident ofgentrified Boise claimed that “a generation of black peo-ple” had grown up hearing the tale from their parentsand grandparents of the “wicked White people who tookaway their neighborhoods” (Sanders 2005).

Urban renewal brutally disrupted various aspectsof residents’ lives: economic, social, psychological,spiritual. It disrupted their attachment to place and

community. It forced them to start over, often withoutadequate compensation for their loss. By 1969, whilemiddle- and working-class Blacks significantly increasedthe number of homes owned in Irvington, King, Sabin,and Woodlawn, the overall Albina home ownership ratedeclined from 57 percent to 46 percent. Urban renewaland unemployment (12 percent for males and 8 percentfor females) were key factors in the declining homeownership rate, but the systematic refusal of banks to

14 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

Figure 3. Neighborhood clean-up by the Albina Neighborhood Improvement Project, 1961–1973 pp.Oregon Historical Society.

KAREN J. GIBSON 15

Fig

ure

4.In

197

1,pr

otes

tors

dem

and

that

Em

anue

l Hos

pita

l pro

vide

the

job

s it

pro

mis

ed a

nd k

eep

the

heal

th c

linic

ope

n.O

rego

n H

isto

rica

l Soc

iety

.

16 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

provide mortgage capital was a pivotal factor. It meantthat prospective buyers could not buy and sellers couldnot sell, except if they lent the money themselves. Manyin Albina, Black and White, purchased their homes “oncontract” from the sellers. A 1969 housing survey con-cluded that “Blacks get bad terms in purchasing. Theyusually buy on contract paying 10% interest. It is diffi-cult for them to get conventional financing. Sellingprices are frequently inflated to black buyers” (Booth1969:84). The inability to get capital to exchangehomes or invest in improvements quickened the deteri-oration of the old, often overcrowded, housing stock. Inrecognition of the problem, a Black-administered bank,the Freedom Bank of Finance, opened in 1970.Venerable F. Booker, the bank president, was fullyaware that the White bankers involved expected it to fail(Laquedem 2005). At that time, the median value ofhomes ($9,350) in Albina was just two-thirds themedian value in the city of Portland.

The affluence of our nation during the 1960s, thecivil rights movement, and civil unrest in urban areasled the federal government to sponsor a variety of com-munity development initiatives such as the War onPoverty and Model Cities. Community action programsduring the War on Poverty were designed to give moneydirectly to neighborhoods that had been neglected bylocal governments. In 1964, Mayfield Webb directed aneighborhood services center funded by the War onPoverty, and a number of community action programswere developed in Albina at this time (Bosco-MilliganFoundation 1995). Of course, mayors across the nationwere furious at the Johnson administration for circum-venting their offices and empowering grassroots organ-izations. Model Cities was the federal response to themayors’ complaints. It still required citizen involvementin the form of “citizen planning boards,” but mayorsfought to retain authority over finance and projects.While the Portland Development Commission (PDC)had worked with Albina residents on the ANIP, it didnot involve them in its initial 1967 application and plan-ning for $15 million in Model Cities money from theDepartment of Housing and Urban Development(HUD). HUD required public participation in ModelCities, and Portland’s plan was criticized for merely“informing” rather than “involving” residents. In arevised plan that reached the city council in 1968, thePDC was “shocked” at resident perceptions of the prob-lems in their neighborhoods, especially because they“spoke directly about racial discrimination.” By 1969,the PDC had taken an official position opposing theplan, in fear that the Citizens’ Planning Board wouldassume the primary role in setting housing and devel-opment policy in northeast Portland. In fact, the PDChad kept plans for Emanuel Hospital “carefully

reserved” from the Model Cities process “despite bitteropposition” (Abbott 1983:194–196). Charles Jordanbecame the fourth director of the Model Cities program.He later became the first Black city commissioner inPortland. While these two federal programs “did notsolve the complex problems of Albina,” they helpednew Black leadership to emerge, and they focusedattention on the problems of Albina (Bosco-MilliganFoundation 1995:93). However, a shortage of decentaffordable housing, residential segregation, and unem-ployment remained vexing problems. While a variety ofcommunity-based initiatives began during this period,including the Albina Corporation (a job-training andmanufacturing firm), the Albina Art Center, the AlbinaYouth Opportunity School, and the Black EducationalCenter, despite these efforts, some residents lostpatience with the status quo.

Black youth in Albina, frustrated with being“locked in” and occupied by the police, exploded inriots in 1967 and 1969, accelerating White residentialand business flight (City of Portland Planning Bureau1991). Riots broke out in cities across the nation in thesummer of 1967. A national commission was formed,the Kerner Commission, which studied the reasons forthese violent explosions. The City Club of Portland(1968) issued a report entitled “Problems of RacialJustice in Portland” as a parallel to the national study. Itconcluded the following:

The range of deficiencies and grievances inPortland is similar to that found by the KernerCommission to exist in large cities in general. Itincludes discrimination or inadequacies in manyareas: in police attitudes and practices; in adminis-tration of justice; in unemployment and underem-ployment; in consumer treatment; in education andtraining; in recreation facilities and programs; inwelfare and health; in housing and communityfacilities; in municipal services; in federal pro-grams, and in the underlying attitudes and behaviorof the White community. Thus Portland shares thecommon pressing problems and perils. To theextent that its problems differ from those of Watts,Newark, or Detroit, the differences are of degree,not of cause and effect, or urgency. [City Club ofPortland 1968:9]

The report noted that racial residential patterns hadresulted in racially isolated schools; specifically, fourelementary schools were more than 90 percent Black(Boise, Eliot, Humboldt, and Highland [now namedKing]). Nearly half the Black children in Portlandattended these schools. The report drew on analyses ofhousing conditions from Model Cities and mentionedtwo key elements usually associated with a systematic

KAREN J. GIBSON 17

disinvestment process: absentee landlordism and mort-gage redlining. These two operate in concert, as redlin-ing prevents households from owning, and thereforethey have little choice but to rent from absentee land-lords who often neglect the property and charge highrent. The report also noted that substandard housing andnegative environmental health conditions were perva-sive in Albina and that these conditions and their allevi-ation were made more difficult by absentee ownership.Black homeowners with equity who wanted to move outof Albina faced discrimination in their attempts to buyin other neighborhoods or the suburbs, and those whostayed in the area had “more than normal difficulty inobtaining improvement or building loans” (City Club ofPortland 1968). Speculation was noted as a problem aswell in another Model Cities study, which found thathousing investment in Albina was discouraged by the“speculative attitude of property owners,” residents’“poor credit,” and “builders’ fear of militant actions” asa result of the civil unrest a few years earlier (City ofPortland Model Cities 1971:4).

The City Club’s Racial Justice Report urged thecity to “overcome deficiencies in numbers of units andquality of available housing” and “review and reformbuilding and sanitary codes, and their administrationand enforcement, on an equitable, nondiscriminatorybasis” (City Club of Portland 1968:52). It noted thatPortland lagged behind other western cities with com-parably sized Black populations in the development ofpublic housing. Black residents, it argued, complainedabout the “scarcity” of brokers handling rental proper-ties for African Americans. In some ways, the real estateindustry had not changed its policies from the 1940s—many brokers continued to discriminate for fear of los-ing “future business by dealing or listing with Negroes”(City Club of Portland 1968: 33–36). Despite commu-nity efforts, Albina was left to predatory lenders, spec-ulators, and absentee landlords. The spiral of declinebegan to manifest itself in the form of dilapidated andabandoned housing, as Black residents began to relo-cate in better housing near Albina.

During the 1970s, African Americans across thenation saw improvements in their economic status as aresult of the civil rights movement and affirmativeaction policies in education and employment. For thefirst time since the post–World War II period, the trendof Black population growth in Albina stopped as thehousing market began to open up. Economic gains weremanifested in the number of homeowners in UpperAlbina, which by 1979 exceeded the number of Whitehomeowners for the first time. Black residents hadtaken the opportunity to buy new homes in Woodlawn,where their home ownership rate was 56 percent, sec-ond only to Irvington at 81 percent. Their increased

presence in Woodlawn caused many Whites to leave,making it the last Albina neighborhood to transition tomajority Black. In Lower Albina, the reclamation ofland for commercial and industrial use meant that theBlack population in Eliot declined by 70 percent for thesecond decade in a row. The only significant Black pres-ence was on the east side of Eliot and in Irvington.Home values in Albina remained just two-thirds of thecity’s median value, and while residents were able toachieve the rehabilitation of several hundreds of units asplanned through the Model Cities process, this still fellshort of the need (City of Portland Planning Bureau1977). Although a late 1970s report by the PDC statedthat the “problem of abandoned housing is a new area ofconcern for the City,” the PDC would not seriously inter-vene until the problem hit crisis proportions in the late1980s (Portland Development Commission 1978:18).

THE ROAD TO ROCK BOTTOM, 1980–90

You’ve got to be a real strong person to live here. Ifyou have children, I’d advise against it.

—King resident, 19887

One mortgage broker, Dominion Capital, Inc., hasset up hundreds of home buyers in risky loans. Thecompany’s own principals said that they can makeloans because they have little competition fromconventional lenders.8

During the 1980s, disinvestment in the Albina area con-tinued until problems became so severe that they finallybecame an issue for politicians in 1988. Economic stag-nation, population loss, housing abandonment, crackcocaine, gang warfare, redlining, and speculation wereall part of the scene. Neighborhood activists such asEdna Robertson, who worked in the Model Cities pro-gram and was the coordinator of the NortheastCoalition of Neighborhoods, had “raised warning flagsabout prostitution, drug dealing, abandoned housingand gang activity before they became public issues”(Oliver 1988). Gang members from the Los Angelesarea had maintained a quiet presence in Albina since theearly 1980s, but that changed during the summer of1987, when competition intensified between the Cripsand the Bloods over crack cocaine. Dozens of dealersfrom the Los Angeles area had begun streaming intoPortland in search of new markets. It helped that theycould sell crack for two to three times the price itfetched in southern California, and that the local policewere unprepared for them (Ellis 1987).

Although 20 years earlier the City Club had criti-cized the city for its neglect of this area, an Oregonianjournalist called Albina a “forgotten stepchild of city

18 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

planning and economic development efforts” (Durbin1988b). Black residents who could afford to move leftthe area, while those who could not stayed behindand lived with the consequences. During the 1980s,Irvington, King-Sabin, Humboldt, and Boise experiencedsignificant declines in the Black population (see Figure 5).By the end of the decade, the proportion of BlackPortlanders in Albina had shrunk by a more than a fifth,from 49 percent to 38 percent. The racial successionprocess that began in the 1940s finally came to an end,except in the Woodlawn neighborhood, where the Blackpopulation increased. Woodlawn borders the northern-most edge of the city, at the “dead end barrier” of theColumbia floodplain (Abbott 1985:6). The long processof moving the Black community northward, whichbegan around 1910, as Eddie Watson said, when theywere first “switched out” of northwest Portland, nowculminated with residents at a physical dead end.

In terms of housing and neighborhood conditions,Albina hit rock bottom in the 1980s. The Albina popu-lation had thinned by nearly 27 thousand people since1950. The value of homes dropped to 58 percent of thecity’s median. In fact, the decline was so sharp that nineneighborhoods received a special reassessment of prop-erty; some homes sold for half their assessed value.Absentee landlordism reached its height by 1989, whenonly 44 percent of homes in Albina were owner occu-pied. The vast majority of the change in housing occu-pancy among Blacks in Upper Albina (96 percent) andLower Albina (63 percent) represented Black ownersselling homes. Some of this was due to generationalchange: many of the war migrants who came in the 1940s

were now at the end of their lives, and their children hadmoved on. White homeowners also left in large num-bers, especially in Upper Albina. The decline in popula-tion and owner occupancy can be explained by anumber of factors. Certainly the economic stagnationthat affected Albina beginning in the 1970s, and hit theentire state hard during the 1980s, explains part of it.The crack epidemic that devastated many communitiesnationwide also hit Portland in the mid-1980s. A recov-ering crack addict, Harrison Danley, compared the epi-demic to the 1960s civil rights era: “We’re not burningdown houses now. We’re burning down the fabric of oursociety” (Durbin 1988c). Gang shootings became moreand more frequent from the middle to late 1980s. Drugdealing became a way for those out of work to makequick money, and the abandoned houses provided aplace to both use and abuse. Houses would be strippedof any valuable materials by addicts or transients inneed of money—doorknobs, light fixtures, wiring.

But the raiding of abandoned houses was only onetype of plundering going on in Albina; other forces hadbeen invisibly preying on the neighborhood for decades.Back in 1968, Black homeowners had complainedabout access to capital for home purchase and rehabili-tation. In 1988, evidence of their complaints wouldcome to light. The King and Boise neighborhoods,which comprised 1 percent of the city’s land, contained26 percent of the city’s abandoned housing units. Thebanking industry had left a vacuum in the communitywhen it decided not to lend money on properties below$40,000. The rationale that the bank does not makemoney on small loans is a poor excuse for a policy of

Figure 5. Number of people transitioning in and out of neighborhoods that experienced higher than normal population changes.

Racial Transition in Impacted Neighborhoods, 1980s and 1990s

-1000 -750 -500 -250 0 250 500 750 1000

Eliot E

Irvington

King-Sabin

Humboldt

Boise

Woodlawn

Nei

gh

borh

ood

s

Black 80s Black 90s White 90s

KAREN J. GIBSON 19

blatant discrimination against Black communitieswhere property values are relatively low (Squires 1994).The only kinds of sales that occurred for years in Albinawere through privately financed deals, often with termsconsidered predatory. As a Boston neighborhoodactivist articulated in this article’s opening quotation,some neighborhoods are “fed,” while others are “bled”(Medoff and Sklar 1994:33). Conventional bankers hadeffectively redlined Albina—bled the life out of it. Thisled to housing abandonment at a major scale. The worstneighborhoods were Boise, Eliot, and King, with morethan 10 percent of the single-family homes vacant.Edna Robertson said that “absentee landlords were buy-ing up houses as tax write-offs and putting no moneyinto them” (Durbin 1988a). In 1988, she spent morethan three months surveying 11 neighborhoods andcounted a total of 900 abandoned buildings. This wasthe final stage of the devalorization cycle.

Activists such as Ron Herndon of the Black UnitedFront had long urged the city to do something about ris-ing crime and housing disinvestment, but their voiceswere not heard until the 1988 mayoral campaign of BudClark (Austin and Gilbert 1988). That same year, thePortland Organizing Project, an interracial faith-basedalliance, began legal challenges against the lendingpractices of local banks, using the newly fortifiedCommunity Reinvestment Act. Eventually this issuecaught the attention of the local newspaper. InSeptember 1990, as a result of a three-month investiga-tion into bank mortgage lending practices in northeastPortland, the Oregonian published a series of articlescalled “Blueprint for a Slum” (Lane and Mayes 1990).The series documented the lack of conventional mort-gage loans and predatory lending practices in theAlbina community. In 1987, all the banks and thrifts inPortland made just ten mortgage loans to a four-censustract area constituting the heart of the Albina commu-nity. The following year, they made nine loans. Thiswas one-tenth the average number of loans per tract inthe metropolitan area (Lane 1990b). This explainedthe flight of many Black middle-class householdsfrom the area. It also explained why predatory lendersand slumlords had come to fill the void left by conven-tional lenders. Lincoln Loan and Dominion Capitalwere two of the biggest companies “selling” homes tounaware consumers, using land sales contracts that keptreal ownership in their hands. Lincoln Loan rented mostof the 200 houses it owned in Albina but sold the ones thatneeded the most work to unsuspecting buyers (Mayes1994). Lincoln Loan not only lent money to buy homesbut also lent homeowners money to fix up the homes.When the owners wanted to cash out and move on, theywould find out that they didn’t really own the house afterall. Dominion Capital owned more than 350 houses in

inner northeast Portland and “sold” them to buyers,sometimes even when previous investors still had title.The scam worked as follows: Dominion would buyproperty at low prices, get phony appraisals that over-valued the property, and entice buyers into sales con-tracts with high-interest mortgage loans containing aballoon payment clause, which required that the mort-gage be paid in full after a short period. Unsuspectingbuyers who were unable to meet the balloon paymentwould be evicted. Dominion would then find anotherfamily to swindle. Shortly after “Blueprint for a Slum”ran in the paper, the state attorney general investigatedDominion, and the owners (one was named Cyril Worm)were sentenced to prison on 32 counts of fraud and rack-eteering. Albina had become a host for predatorsbecause of the void in conventional mortgage lending.Many neighborhood activists felt that these people haddone more to hasten the deterioration of Albina than thecrack dealers and gangbangers. Herndon, lamenting thedecline in neighborhood stability that resulted from thedeparture of the Black middle class, pointed to thebankers: “Had they insisted that fairness be exercised—almost single-handedly they could have stabilized thatcommunity a long time ago” (Lane 1990b). Yet the statehad also failed to protect its consumers.

RECLAMATION AND TRANSFORMATION,1990–2000

I can guarantee you they are paying more in rentthan they would to buy a house in this neighborhood.

—Ora Hart, Realtor9

We fought like mad people to keep crime out ofhere. Had we not fought, I don’t know what this areawould’ve eventually been. But the newcomershaven’t given us credit for it. I envisioned cleaningup the neighborhood, making the neighborhood liv-able for all of us. . . . We never envisioned that thegovernment would move in and mainly assistWhites. They came in to the area, younger Whites.[The Portland Development Commission] gavethem business and home loans and grants, and madeit comfortable and easy for them to come. I didn’tenvision that those young people would come inwith what I perceive as an attitude. They didn’t comein “We want to be a part of you.” They came in withthe idea, “We’re here and we’re in charge.” . . . In thepast, Blacks and Whites worked very stronglytogether. We were one. This thing that happened inthe last ten years has been most disappointing, mostuncomfortable. It’s like the revitalization of racism.

—Charles Ford, Boise resident since 195110

20 TRANSFORMING ANTHROPOLOGY 2007 VOL. 15(1)

In the 1990s, for the first time in 50 years, the popula-tion of Albina grew. The pattern of racial transition wasreversed, as Whites reclaimed the housing they had leftdecades earlier, enticed by the Victorian housing stock,affordable prices, and reinvestment efforts the city hadbeen making. The same four areas Blacks left in signif-icant numbers in the 1980s (Irvington, King-Sabin,Humboldt, and Boise) continued to experience a majordecline in population. For the first time, too, Blacks leftWoodlawn. Whites moved into these neighborhoods ingreater-than-average numbers—and they finally stoppedleaving Woodlawn (see Figure 5). And for the first timesince 1960, Blacks were no longer a clear majority inany Albina neighborhood except on the northwest sideof Eliot (an area that had lost 86 percent of its housingunits since 1960 and had a tiny population of 200).Realtors used the art galleries popping up on AlbertaStreet, a Black business corridor, to aggressively marketthe King-Sabin area as the “Alberta Arts District,” andit saw a rapid influx of White residents. Joe’s Place, at18th and Alberta, known in part for its great jukebox,was the last Black-owned bar on Alberta and one of thefew remaining in Portland. Other clubs such as Marty’sPlace, Stax, The Silk Hat, and Theme closed down dur-ing the late 1980s and early 1990s. Other ethnic groups,largely Hispanics, increased their presence in Albina,and these changes meant that the overall racial and eth-nic composition of Albina was transformed from Blackmajority to a three-way mixture, with no majority.These population trends explain the large decreases insegregation indices that ranked Portland in the top tennationally. For the first time in 60 years, since thecolor line was hardened in 1940, segregation fell

below a level considered high. At the turn of thecentury, less than one-third of Black Portlanders calledAlbina home.

During the 1990s, the City of Portland put con-certed effort into the revitalization of Albina. Inresponse to complaints of neighborhood activists andthe recommendations of a citywide task force report onabandoned housing, the City began using building codeenforcement to confront the extreme level of housingabandonment (City of Portland 1988). It gave more than100 foreclosed homes to the Northeast CommunityDevelopment Corporation for rehabilitation through thefederal Nehemiah grant program. It stepped upCommunity Development Block Grant and otherspending to support nonprofit housing development. Itshamed the bankers, who had been redlining the com-munity, into supporting the establishment of thePortland Housing Center to help boost home ownershipamong low-income households. It even set up a non-profit community development corporation to take overDominion’s portfolio of 354 single-family homes.

Gretchen Kafoury, former state legislator andcounty commissioner, ran for city council on a housingplatform and began work in 1991 at these activities.One of the White progressives who in the 1960s madeher home in integrated Irvington, she never thought shewould see an end to vacant and abandoned buildings ininner Northeast and North Portland “in her lifetime”(Kafoury 1998). But she has. Grassroots activists forcedlocal government to stop the bleeding, but this turnedthe redlining to greenlining. Of course, the flood ofWhite homebuyers would not have occurred without the1990s economic boom that raised home prices in all

Figure 6. Home values tripled and sometimes quadrupled during the 1990s.

Trend in Median Home Values in Gentrified Neighborhoods

$0

$50,000

$100,000

$150,000

$200,000

$250,000

Eliot E Irvington King-Sabin Humboldt Boise Woodlawn

1990 2000

KAREN J. GIBSON 21

other quarters of the central city. A booming economy,cheap mortgage money, bargain-basement property, andpent-up demand coincided to transform pockets ofAlbina in three or four years from very affordable to outof reach. At the beginning of the decade, the worry wasabandonment; at the end, it was the preservation ofaffordable housing.

By 1999, Blacks owned 36 percent fewer homes,while Whites had 43 percent more than a decade earlier.The decline was largely because Blacks sold theirhomes in Irvington, the most affluent neighborhood inAlbina. Although overall the Black home ownershiprate increased from 45 percent to 49 percent, it wasbecause the proportion of Black renters declined.Whites bought homes, displacing many low-incomefolks to relatively far-flung areas where they couldafford the rent. The White home ownership rate esca-lated from its rock bottom of 44 percent to 61 percent injust ten years. Housing values, as a percentage of the citymedian, rose significantly, from 58 percent to 71 percent(see Figure 6). This sharp rebound in Albina propertyvalues, which corresponds with the increase in Whitehome ownership, reveals the continuing correlationbetween property valuation and race.

This was made starkly clear to Susan Hartnett, aWhite Chicago transplant who purchased a home inEliot during the 1980s. Banks refused to lend to herbecause the mortgage amount was below their mini-mum, so she and her husband bought the $15,000 homewith savings. After using credit cards and pension fundsto rehabilitate it, they tried again to get a mortgage, thistime for $43,000. When the loan officer and appraisercame out to inspect the home, the appraiser said it wasa “nice place” that would appraise at a “much highervalue in another neighborhood,” but that he would havea hard time finding comparable sales. When Ms.Hartnett suggested other neighborhoods, the appraisersaid “No, no, that would not work.” Then the loan offi-cer said, “It’s because there are a lot more Blacks herethan in those other neighborhoods.” Ms. Hartnett was sosurprised by the remark that she “nearly fell off theporch” (Lane 1990a).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The larger community doesn’t see a lot of value inthis community—but before this crack epidemicyou could walk into any part of inner-North andNortheast Portland anytime, anywhere.

—James Mason, King resident11

I am hurt, to the core. But I’m not mad. My hurtmade me recognize the problems we had 40 yearsago still exist. We thought that we had achieved.

We thought we’d bridged that. Little did weknow—look at us today. We have to go back andstart all over again.

—Charles Ford, Boise resident12

In the late 1980s, when Portland’s Bureau of Buildingsbegan to execute its charge from the council to“research and develop a range of proactive housingcode enforcement programs,” it met with neighborhoodassociations; city, state, and federal agencies; housingindustry groups; and individuals (City of PortlandDepartment of Public Safety 1989). The city facedstrong opposition from industry groups such as theOregon Apartment Association, Multifamily HousingCouncil, Board of Realtors, Institute for Real EstateManagement, Oregon Mortgage Bankers Association,and the Association of Home Inspectors, which wereconcerned about the business impacts of the regulationsand fees associated with code enforcement. After all,these entities had been operating virtually unrestrictedfor many years in a market they had captured for profittaking. Only investors could purchase homes for cash,since there was no conventional financing. One residentcould borrow $25,000 for a car but could not get$16,000 for a house (Lane 1990b). Investors gobbled upproperties at bargain rates, earning their money backwith a few years of rental payments from low-incomeresidents with few choices. Speculation and slum-lordism flourished in this unregulated environment. Oneof the worst slumlords owned more than 100 houses andmade a living renting to the poor and vulnerable(Kafoury 2005). Houses changed hands often, fre-quently with land-sales contracts that went unrecorded,making it difficult for the Bureau of Buildings to iden-tify owners to make needed repairs. Houses would bemilked for profits until they were abandoned.According to Margaret Mahoney, Bureau of Buildingsdirector, most owners of abandoned houses were peopleshe called “close absentee owners—people who livesomewhere in the metropolitan area and own between15 and 40 run-down houses that they bought cheap inthe 1970s.” Also according to Mahoney, some were“responsible property owners” who were just “exhausted”by the problems associated with gang and drug activityin the 1980s (Durbin 1988a).