KAIKA Maria (Form Follows Power)

-

Upload

odradek666 -

Category

Documents

-

view

35 -

download

2

description

Transcript of KAIKA Maria (Form Follows Power)

This article was downloaded by: [Umeå University Library]On: 19 July 2015, At: 06:55Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG

City: analysis of urban trends, culture,theory, policy, actionPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccit20

Form follows powerMaria Kaika & Korinna ThielenPublished online: 18 Aug 2006.

To cite this article: Maria Kaika & Korinna Thielen (2006) Form follows power, City: analysis ofurban trends, culture, theory, policy, action, 10:01, 59-69, DOI: 10.1080/13604810600594647

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604810600594647

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoeveror howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to orarising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

CITY, VOL. 10, NO. 1, APRIL 2006

ISSN 1360-4813 print/ISSN 1470-3629 online/06/010059-11 © 2006 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/13604810600594647

Form follows powerA genealogy of urban shrines

Maria Kaika and Korinna ThielenTaylor and Francis Ltd

In this paper, Maria Kaika and Korinna Thielen chart the historical development of ‘thesecular shrine’—an assertion of state and corporate power that came to dominate the urbanlandscape from the second half of the nineteenth century. Many of the aesthetic features ofthis secular monumentalism can be identified in earlier sacred and classical architecture andserved to legitimate its adaptation for secular purposes. With the exception of industrialarchitecture, it was only in the latter half of the twentieth century that the secular shrine asunadorned modernism finally emerged. The perceived failure of modernism to create live-able communities prompted a shift in emphasis towards a ‘picture postcard’ view of the cityin which ‘signature buildings’ stand as new forbidden temples. Kaika and Thielen concludethat both the sacred and the profane continue to use the built form as an iconography oftheir respective wills to power.

From religious monuments to “cathedrals of technology”: the birth of the secular public shrine

ince the birth of cities, it has alwaysbeen monuments dedicated to stateor religious power that have domi-

nated the urban skyline. From the Egyp-tian pyramids, a homage to the power ofthe Pharaohs, to the Athenian Parthenon,a monument to democracy, to Sienna’sPalazzo Publico, symbol of state authorityand a stage for public life, monumentalbuildings represented authority, and func-tioned as focal points for public urban lifeand as urban landmarks. In mediaevaltimes, cathedrals and town halls were themost important landscape landmarks, andhosted an array of public activities, fromcoronations to weddings, and from politi-cal intrigues to religious festivals(Cosgrove, 1984). The sheer volume andheight of these constructions made themprominently visible, while their visual

domination was further pronounced bythe choice for their location—on a hill, inthe centre of town, or in front of a publicsquare that was often purpose built to hostfunctions related to the building. Scale andlocation choice worked in synergy towardsaccentuating the symbolic character ofthese monuments, and cast in stone, quiteliterally, the power of authoritative institu-tions (Schorske, 1981; Zukin, 1991; Lefeb-vre, 1994 [1974]; Damisch, 2001). Thebuildings were committed to be standingproudly for as long as the authority thatthey represented remained in power.

However, with the shift to a modern,industrialized, secular society, state andchurch power, along with the power oflanded aristocracy, gave way to the powerof the emerging bourgeoisie. The belief ingod was complemented or even replacedby the belief in money power and thepower of technology. The state found anew role in supporting capitalist forma-tion, industrialization and technological

S

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

60 CITY VOL. 10, NO. 1

innovation while securing social cohesion.As part of its new role, the bourgeois statequickly became the key manager of therationalization of urban space and ofurban sanitation projects, and the keyprovider of “collective means of consump-tion” (Castells, 1977). The aforementionedchanges in the nature and constitution ofauthority and power were reflected inchanges in the production of urban spaceand in what constitutes a monument and apublic shrine. From the second half of the19th century, cathedrals were built not tohouse god, but to house money, technol-ogy and innovation. From banks to facto-ries, from pumping stations and watertowers to gas works and train stations, awhole new array of secular shrines werecreated and dedicated to money flows,technological innovation, and industrialproduction. These new urban shrines, soonreplaced churches and town halls as urbanlandmarks, and competed with them in aquest to dominate the urban skyline andthe public imagination. These buildingsbecame symbols of a new era of modern-ization and secularization, where the glori-fication of the power of capital and thepromotion of industrialization would gohand in glove with the rationalization ofurban space and urban life (Kaika andSwyngedouw, 2000).

The architectural language that was chosenfor these cathedrals of money and technol-ogy was traditional, directly copied frommonuments of the past. The gothic andneoclassical style of churches and town hallswas now used to build banking institutionsand train stations. From the Bank ofEngland, to the Fairmount Waterworks inPhiladelphia (early 19th century), toLondon’s Abbey Mills Pumping Station(mid-19th century) and Euston Station (early19th century), the new secular shrines wereas heavily adorned in neoclassical symbolismand ornament as cathedrals and town halls inthe past. Although dedicated to innovationand modernization, these buildingsborrowed the architectural language of the

past to invoke grandeur and to assert thepower of the new authorities that producedthem.

Moving into the 20th century, the use ofnew construction materials and techniques(notably the proliferation of steel frameconstructions) did not have an immediateeffect on the architectural language that wasused for these new urban shrines. BatterseaPower Station (1929–1939), designed by SirGilbert Scott (designer of the red telephonebox), was constructed using cutting-edgetechnology. However, its steel frameconstruction (similar to that of the Americanskyscraper) was covered by brickwork hang-ing from the building’s external façade. Thestation’s interior was also higly decoratedwith stunning Art Deco ornament, while thebuilding’s most characteristic feature, its fourchimneys1, were also moulded in the form ofGreek doric columns. Similarly, the BanksidePower Station (1947–1963, now hosting theTate Modern), designed by the samearchitect, also used brickwork to cover itssteel construction.

In general, adherence to traditionalismcharacterized the early urban shrines thatwere dedicated to the coupling of the powerof money and industry with state power, orhosted state-funded and -managed projectsof public sanitation and urban infrastructure.It was ironic that the innovations of an eraotherwise committed to the future wouldoriginally be vested in the symbols of thepast. The reasons behind the choice of atraditional architectural language for newfunctions related to state-funded technologi-cal innovation projects were threefold:firstly, because borrowing the language of atraditional style provided an easy designsolution for building a new type of monu-mental non-religious building for a secularsociety; secondly, because invoking elementsof the iconography of the past would maketechnological innovation and its new cathe-drals more palatable and publicly acceptable(Vaxevanoglou, 1996; Kaika, 2005); andthirdly, because traditional styles, in particu-lar the Greek Revival and the neoclassical

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

KAIKA AND THIELEN: GENEALOGY OF URBAN SHRINES 61

style, were considered to be more ‘noble’, asthey had adorned churches and town halls inthe past (Chant, 1989; Kaika, 2006). It wasonly towards the second half of the 20thcentury that the public secular shrines wouldresume a more innovative aesthetic form. Forexample, the boldly designed BT Tower(1961–1965, designed by Eric Bedford) was adecidedly modern construction and thetallest structure in the south-east of Englandat the time.

In this early period of state-funded urbaninnovation, it was only ephemeral state-funded constructions that dared to shed thesymbols of the past and assert the bareaesthetics of new building materials. This iswhy many of the buildings that hosted Inter-national Exhibitions became unique urbanlandmarks. They marked the urban landscapefor as long as the exhibition lasted, but wereexpected to fade away/be dismantled alongwith the end of the event. The spectacularconstructions that hosted or became emblem-atic cases of International Exhibitions couldafford to be bold precisely because they wereephemeral. Since they were built to accom-pany a momentary “urban pulsar” (Beriatosand Colman, 2003), their designers did nothave to worry about complying with public“taste”. The Exhibitions themselves werededicated to innovation, technology andinternationalization of trade and to innova-tive urban experience. Therefore, Interna-tional Exhibitions became ideal playgroundsfor engineers and architects to assert theaesthetic beauty of new materials and newtechnology: the Eiffel Tower (1889) and theCrystal Palace (1851) owe their bold design totheir then assumed ephemeral character.Indeed, it is well documented how theParisian public hated the Eiffel Tower origi-nally, precisely because its designer—an engi-neer—attempted a new design language,using the bare aesthetics of the constructionmaterials. In short, apart from ephemeralconstructions, little change occurred in thearchitectural “language”, that was used forthe new urban monuments. This continued tobe traditional.

It was only in the cases where private capi-tal was decoupled from state power thatmore innovative design approaches wereundertaken. Famously, the AEG HighTension factory in Berlin, designed by PeterBehrens in 1910, was the first CorporateLogo building to follow the modernist motto‘form follows function’, while still followingthe time old motto “form follows power”.Behrens shed the traditional ornament anddevised a new architectural language(Frampton, 1983, p. 152), that would corre-spond to the company’s forward-lookingvision, thus producing one of the firstprivately commissioned secular shrines.However, like the early state- or church-funded monuments, the form of the innova-tive private shrines would also try to inscribepower into urban space.

The private secular shrine: building as homage to private capital

From the first half of the 20th centuryonwards, western cities underwent importantchanges as they assumed their role in thenewly configured international division oflabour. Once again, these changes werereflected in the production of urban space.The expansion of the size and importance ofthe Central Business District (CBD) was onesuch significant change (Hall, 1996). TheCBD had existed since the late 19th century.However, as corporations became larger, theCBD expanded accordingly and between1920 and 1930 office space in the 10 largestAmerican cities increased by 3000%, whileby 1929, 56% of America’s national corpora-tions had located their headquarters in NewYork City or Chicago (Tabb and Sawers,1984; Hall, 1996).

For the first time we had private commis-sions for bold architectural statements thatwould be neither private houses nor publicmonuments, that would glorify neither god,nor state or clergy power, but the achieve-ments of one single individual, or one singlecompany. Buildings that would become

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

62 CITY VOL. 10, NO. 1

identified with corporations, and wouldwork as a kind of logo for these corporations,gave for the first time the opportunity toarchitects to combine impressive design withinnovative building practices in a construc-tion that was neither public, nor ephemeral incharacter.

For the first time, the power of privatecapital consolidated its power in urban formto this extent and with such boldness. Thiswas the end of the Dutch ethic of “theembarrassment of the riches” that character-ized merchant and proto-industrial societies(Schama, 1987) and the assertion of conspic-uous bourgeois consumption as an ideal inits own right. The new urban species thatwas born out of advanced capitalist devel-opment, the banking, manufacturing, ship-ping, construction or media tycoon,considered the city to be their stage andwere keen to mark urban space as their ownterritory. Within this context, architectureitself became a product for conspicuousconsumption, along with luxury garments,cars, jewellery, gadgets, etc. and the privatesecular shrine was born. Of course, early20th-century tycoons were not the firstpowerful people in history to commissionshrines. From the Maecenas of antiquity tothe renaissance patrons of architecture, therich and the powerful had always contrib-uted to the monumentalization of urbanspace. However, although these earlypatrons glorified their name by commission-ing cathedrals in the name of god, 20th-century tycoons no longer needed to invokegod as an excuse to glorify their name andto put their mark on urban space. Instead,they erected cathedrals in their very ownname, which they had inscribed on to thebuildings. The Chrysler Building, a homageto the construction industry tycoon WalterP. Chrysler, was built between 1926 and1930, and claimed the title of the tallestbuilding in the world (319.4 m). Similarly,New York’s Rockefeller Centre (1929–1940)was a homage to the empire of a powerfulindividual, while the Woolworth Building,also in New York (1913), marked the

empire of the powerful merchant Frank W.Woolworth.

Still, these homages to corporate powerand individual achievement were originallyas shy as the state-built technological cathe-drals when it came to displaying innovativebuilding techniques and baring new materi-als. The early US skyscrapers would hidetheir steel frame behind brick or stone. TheWoolworth Building (1913, designed byGass Gilbert), known also as the “Cathedralof Commerce”, adopted a neo-gothic styleand was clad in terra cotta. The Singer Build-ing, in New York City (1908, designed byErnest Flagg), was veneered with brick in anattempt to make the corporate face of Singermore “friendly”. The architects of these earlyprivate shrines went out of their way to“familiarise the unfamiliar” (Meejin Yoonand Höweler, 2000) and make the newshrines publicly acceptable and hopefullyloved.

It was much later that private shrineswould start “stripping” from ornament andtheir form started to follow more closelytheir function. This modernist turn reachedits epitome with the Seagram Building (1958,Mies Van Der Rohe with Philip Johnson). Awhole array of trademark modernist build-ings followed suit, competing over heightand importance, and tried to dominate theurban skyline and the public imagination:New York’s John Hancock Center (1969,Skidmore, Owings and Merrill) and WorldTrade Center (1972 and 1973, MinoruYamasaki Associates), Chicago’s SearsTowers (1974, Skidmorek Owings andMerrill), Boston’s John Hancock Tower(1976, Henry Cobb of I. M. Pei & Partners),etc.

After the 1970s, commissions for privateshrines moved away from the modernistaesthetic and tried hard to become venerable,not only through competing for height, butalso through competing for innovative designfeatures (Domosh, 1992). The Lloyds Build-ing in London (1979–1984, Richard Rogers)is imposing through its innovative high-techdesign, and although it does not claim the

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

KAIKA AND THIELEN: GENEALOGY OF URBAN SHRINES 63

highest point in London’s skyline, itcertainly claims a very high point in lay andexpert imagination and approval. TheLipstick Building (1986, Johnsohn andBurgee) in New York screams for attention,and so does London’s recently completedSwiss Re Tower—the “Gherkin” (2004,Foster and Partners), and Barcelona’s TorreAgbar, the new headquarters of the city’swater company (2002–2004, Jean Nouvel).These privately owned buildings openlycompete with older public monuments, andconsciously try to dominate the urbanskyline and the public imagination. Swiss ReTower is openly competing with St Paul’scathedral in height and significance, whileTorre Agbar competes with Gaudí’s SagradaFamilia.

Many amongst this new generation ofprivate shrines did not quite succeed inacquiring the desired venerable status, prov-ing that shape and size alone are not enoughto grant a building the status of an urbanlandmark. For despite the fact that thesebuildings dominate the urban skyline, theirrelation to public space is very different tothat of older shrines. They stand like self-assured and self-sufficient fortresses, neitherneeding nor desiring to engage with publicspace. Despite making a loud public state-ment, they nevertheless look inwards andmore often than not even try to “protect”themselves from the public realm, by block-ing access to the public, or by making accessexcessively expensive (e.g. group access toSwiss Re Tower’s top floor is charged inexcess of £200). In Manhattan, where thistype of building dominates, it is only thanksto an innovative New York City legislation,which allowed higher plot-ratios to build-ings that would accommodate public spaceon their ground floor that public plazas existon the ground floor of private buildings,allowing public access to what would other-wise be totally secluded and fortified privateurban realm at the street level (Fainstein,1994; Zukin, 1995).

Since private shrines were built asstatements to the lasting power of private

empires, their maintenance and longevitywould normally be guaranteed by the contin-uation of the dynasty or the corporation thatproduced them. However, while moneyempires rose and fell, many of these urbanlandmarks acquired a symbolic status and aspecial place in the public imagery. Many ofthem became cultural icons, a process oftenassisted by the rise of the power of the mediaand of Hollywood. The Empire State Build-ing, for example, made its first appearance onscreen in the 1933 film King Kong, and thatwas followed by an array of films including,more recently, Sleepless in Seattle andIndependence Day.

The rise of the private icon coincided alsowith the reinstatement of the architect’ssocial role (see the articles by DonaldMcNeill, 2006, and Leslie Sklair, 2006, inthis issue; also Sklair, 2001). Architects wereglorified alongside the tycoons whocommissioned them. Some of them becameglobal socialites and experienced a statussimilar to that of the renaissance architect, orthe Egyptian architect that was second onlyto the Pharaoh himself in social status.Along with the birth of the urban icon camethe birth of the pop-architect, the architectas fashion designer, who would competeover producing the louder and moreconspicuous building statement to matchequally loud patrons.

The collective performer: social housing projects as public shrines

The role of the bourgeois state as a guarantorof social cohesion did not only entail fundingand managing urban sanitation and infra-structure projects. When the living condi-tions of the working class deteriorated to theextent of jeopardizing industrial productionand capital accumulation through strikes andsocial upheaval, the state would intervene tore-establish social cohesion. This interven-tion would sometimes take the form of thestick, by accentuating police and militaryintervention, but occasionally it would take

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

64 CITY VOL. 10, NO. 1

the form of the carrot, by launching socialhousing projects that would improve theliving conditions of the working class. Thequestion of social housing also attractedthe interest of the architectural avant-garde.It became the central theme of the secondCIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architec-ture Moderne; held in Frankfurt in 1929),and the years before the Second World Warwitnessed a number of pioneering experi-mental social housing projects across Europe:in Holland, Michel de Klerk’s five-storeyblocks of flats at Spaarndammerplantsoen(1915–1916) became prototypes of modernliving; in Rue du Cubisme, in the Koekelbergdistrict of Brussels, Victor Bourgeois’ groupof houses (1922) pioneered flat roofs andlarge windows; in Vienna, the Karl Marxhof,a mini city for 6000 people, designed by KarlEhn in 1927, became a flagship project forsocial housing.

However, it was not only the state thatfunded pioneering social housing projects.Acknowledging the importance of socialcohesion many industrialists undertookthemselves the building of social housing fortheir workers. As early as mid-19th century,the father of industrial paternalism, Sir TitusSalt, relocated his woollen mills outsidecrime-ridden Bradford, and created Saltaire, atown that housed both his new mills and hisworkers. Similar examples could be foundacross the western world. Much later, in1925, Le Corbusier would build the“Quartier Moderne”, a housing complexnear Bordeaux, funded by the industrialistHenri Fruges, pioneering pre-fabricatedconstruction.

After the end of the Second World War,the need to house millions of homelesspeople and the commitment of westernstates to social welfare projects led to themass production of housing projects thatwon international recognition and reapedarchitectural awards. As with corporateshrines, these projects gave architects thechance to assert modernist aesthetics, andexperiment with new materials. Thesehistorical circumstances gave Le Corbusier

the chance to realize his dream for building‘machines for living in’. His Unités d’Habi-tation in Marseilles (1947–1952) and Berlin(1956–1959) were massive apartment blocksfor functional and efficient living. The samehistorical moment also realized some ofEbenezer Howard’s late 19th-century ideasin the form of New Towns. Although theyreceived fierce criticism in the 1990s, theseinnovative landmarks of post-war planningwere hailed as they were built as the bestcases of social housing and social planning.British New Towns were visited byhundreds of visitors in the 1960s, 1970s and1980s, who marvelled at the ability of thepost-war state to produce a totally newconcept and form of urban space.

Also included amongst the award-winningpost-war social housing projects was the(in)famous Pruitt-Igoe, in St. Louis,Missouri, USA. Designed in 1951 by archi-tects Minoru Yamasaki and GeorgeHellmuth, and completed in 1956, it wasfunded through the post-war US federalpublic-housing programme, and featured 33eleven-storey buildings spread on a 35-acresite (von Hoffman, 2005). When built, it waspraised as “the epitome of modernist archi-tecture—high-rise, ‘designed for interaction,’and a solution to the problems of urbandevelopment and renewal in the middle ofthe 20th Century” (Keel, 2005). In April1951, the Architectural Forum announcedthat the project had “already begun to changethe public housing pattern in other cities”(cited in Bailey, 1965).

Although these projects were hailed aspioneering by architectural critiques and theavant-garde, they never quite acquired ahigh status in the public imagination, andwere never really liked by the people whoactually inhabited them. From the 1970sonwards, private land speculation practices,combined with huge public deficits, madesocial housing projects more financiallydemanding and difficult to implement. Notonly was there not enough funding for newprojects, but existing projects also becamedifficult to maintain and manage. The post-

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

KAIKA AND THIELEN: GENEALOGY OF URBAN SHRINES 65

war welfare state that had produced thelandmark social housing projects of the1950s and 1960s was now crumbling and itsflagship projects were left to ruin. Only 10years after the completion of the Pruitt-Igoe,the Public Housing Administration spent $7million in an attempt to save the project thathad already fallen into disrepair, and wasvandalized by its own residents (Bailey,1965; Keel, 2005). Unable to continue tosubsidize the project, the authority finallyordered its demolition. The first block wentdown with a bang on 16 March 1972, andthe demolition was completed in 1976 (Keel,2005). The once award-winning projectbecame the symbol for everything that waswrong with modernist architecture, andarchitectural critic Charles Jencks hailed16 March 1972 as the end of modernism.Although this aphorism has been widelydisputed since (Harvey, 1989a), the momentcertainly symbolized the end of the post-war Keynesian state and the difficulty thatthe welfare state was faced with, in its effortsto keep up with large-scale social housingprojects.

London’s Barbican constitutes an interest-ing moment of transition in public socialhousing projects. Its proximity to the Cityof London made the development morecomplex than that of other areas of thecapital, and while the first proposal wassubmitted to the Corporation of London in1955, as part of the post-war London rede-velopment plan, it was only in 1971 thatconstruction work began, and the projectwas completed in 1982. While the economicand design principals were the same as thosethat guided the production of other areasaround London after the Second WorldWar, the delay in the Barbican’s construc-tion meant that it got caught up in the realestate boom of 1963–1973 that, as we haveseen, made social housing expensive anddifficult. The new design that was launchedto accommodate the new real estate situationmade the Barbican one of the first mixed-useprojects, and one of the last large-scale socialprojects in the UK.

Still, in countries that continue to maintaina commitment to social welfare, such projectssaw a revitalization in the late 1970s and early1980s. In France, the Arènes de Picasso, inMarne-la-Vallee (1977–1984, ManoloNunez-Yanowsky) as well as the Palaisd’Abraxas (1978–1982, Ricardo Bofill),became self-proclaimed post-modernshrines, with imposing design details that arereminiscent of fascist architectrure (Lucan,2001). According to Bofill, his mission was togive the residents a sense of “royal grandeur”to compensate for their limited floorspace.The Palais d’Abraxas gained cult status afterit became the setting for Terry Gilliam’s filmBrazil.

The private–public shrine: the building as a temptress

After the 1970s, sweeping internationaleconomic social and political changes intro-duced inevitable changes in the productionof urban space. Notably, the state’s role inthe production of urban space shifted frombeing an entrepreneur, who would fund andoversee projects of urban renewal, tobecoming a networking institution and ahands-off manager of projects that would befully developed by private entrepreneurs(Harvey, 1989b). As the role of the state waswaning, private developers and privatecapital became key actors in urban renewalinitiatives. As an ever-increasing number ofservices that used to be public became priva-tized, the public’s role also changed frombeing a citizen to becoming a consumer(Fainstein, 1994; Swyngedouw, 2000; Lees,2001).

The new power configuration around theproduction of urban space entailed a shift offocus from large-scale projects, based oncomprehensive economic and spatial plan-ning, to smaller-scale projects based onurban design practices that put more empha-sis on design aesthetics and were lessconcerned with fostering synergies betweenthe re-designed areas and the rest of the city.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

66 CITY VOL. 10, NO. 1

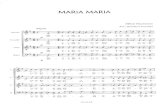

Part of the new managerial role of urbangovernance was to attract capital to invest incities through forging public–privatepartnerships. Thatcher’s Britain pioneeredprivate–public developments with the rede-velopment of London’s Docklands acting asa flagship project for the new ethics ofconservative urban renaissance. However, itwas Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum that stolethe title of the exemplary global ‘iconic’private–public project (see Jencks, 2004; alsoJencks, 2006 in this issue). Many other citiesacross the western and non-western worldfollowed suit in an effort to build ‘iconic’ inthe hope of putting themselves on the map asglobal cities. An array of Guggenheim-likebuildings were commissioned to a handful ofstar architects over the last decade, anticipat-ing a Bilbao-like effect: Birmingham’s BullRing and Selfridges; and Barcelona’s Euro-Forum 2004 (see Brenner, 1998; Moulaertet al., 2003).Figure 1 The private secular shrine ‘competes with older public movements and tries to dominate… .’ The Swiss Re Tower and the Royal Exchange in the City of London. Photograph: Maria Kaoka.The recent public–private partnershipswere expected to act as catalysts for furtherurban renaissance. This new type of devel-opment, however, often produced sleekislands of development in the middle ofdecaying urban areas. The 19th- and 20th-century preoccupation with large-scalelandscaping and planning gave way to apractice of urban design that aimed atproducing ‘postcard views’ of the city, thatcould be photographed and used topromote the contemporary metropolis tothe tourist industry and to internationalcapital. The strategy adopted by localauthorities to this end, i.e. to commissionstar architects to design public–privatebuildings that can act as logos for their city,is identical to the strategy adopted byprivate corporations. Indeed, it is often thesame architects who are commissioned tobuild for both the private and the publicsector. From museums and stadiums toshopping malls, the recent public–privateprojects that act as symbols of prosperityfor a location bear remarkable similarities instyle and function, and use almost identicalarchitectural language. For example, the

most recent home to the Mayor of Londongives a corporate iconography to a statefunction, marking the new managerial roleof urban governance (McNeill, 2002).Indeed, if we compare the public London’sNew City Hall, designed by Foster andPartners (1998–2002) and the private SwissRe Tower, designed by the same architec-tural partnership, we can easily identify thesame desire to make a statement and to‘stand out’. Regardless of their very differ-ent functions, the two buildings hold acunning resemblance. The similarities in thearchitectural language used on both occa-sions undermines the power of symbolismthat these buildings try to convey, as itblurs the boundaries between the iconogra-phy of the private and the public in theurban skyline.

The now widespread ideology of usingdesign as a siren calling for further urbanrenaissance did not produce only new‘iconic-to-be’ buildings. It also had an inter-esting effect on earlier (late 19th- and early20th-century) shrines—power stations, gas,train stations, etc.—that had undergone aprocess of ruination and had long becomedead capital. The London Docklands, thathad become obsolete with the introductionof container technologies, was one of thefirst landmarks of the past to undergo sucha transformation. The buildings alongLondon’s South Bank are a more recentexample of the same process. London’s OldCounty Hall (designed by Ralph Knott, andofficially opened in 1922) had been‘hollowed out’ of its original function, afterMargaret Thatcher abolished the GreaterLondon Council in 1986, but was laterturned into the Saatchi Gallery. Similarly,the old Bankside Power Station that wasclosed down in 1981, only 20 years after ithad become fully operational, was revampedin 2000 by Herzog & de Meuron into theTate Modern and has since become one ofLondon’s landmarks. The Battersea PowerStation is also on its way to undergoingsuch a transformation through a controver-sial public–private partnership that will turn

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

KAIKA AND THIELEN: GENEALOGY OF URBAN SHRINES 67

it into a commercial and entertainmentcentre.

Conclusion

Despite the recent focus of journalistic andacademic discourse on ‘iconic building’, theidea and practice of monumental buildingthat serves the glorification of authority isnot new. By performing a genealogy ofurban shrines that were constructed in thecourse of the 19th and 20th centuries in thewestern world, this article identifies changesin the public perception of this type ofbuilding and searches for the driving forcesbehind these changes. The article asserts thatchanges in the way urban shrines are

commissioned as well as changes in theirform and function can only be interpretedby looking at changes in the nature of theinstitutions or power brokers that fundthese projects. Five types of urban shrinehave been identified: pre-modern monu-ments—deference to state and churchauthority; public cathedrals of technologyand money power—tributes to a new era ofsecularization and industrialization; privatesecular shrines—homage to individualachievement under capitalism; social housingprojects—patially inscribed bold statementsof the post-war welfare state; and private–public shrines—temptresses for globalfinance. The article identifies the struggle forpower under capitalism and the role of thestate as key driving forces behind changes in

Figure 1 The private secular shrine ‘competes with older public monuments and tries to dominate… ’. The Swiss Re Tower and the Royal Exchange in the City of London. Photograph: Maria Kaika.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

68 CITY VOL. 10, NO. 1

what constitutes an urban shrine andchanges in the iconography of buildings.The rise and fall of urban shrines, the riseand fall of styles, as well as the rise and fallof pop-architects, has always been linked tothe rise and fall of public or private empires.

Note

1 1 Two chimneys are part of the original 1939 building, while the other two were built as part of Power Station B, between 1953 and 1955.

References

Bailey, J. (1965) ‘The case history of a failure’, See http://bacweb.the-bac.edu/~michael.b.williams/Pruitt-Forum.htm. Accessed 11 January 2006. Architectural Forum, December 1965.

Beriatos, E. and Colman, J. (2003) ‘The pulsar effect in urban planning’, in Beriatos, E. and Colman, J. 38th International ISoCaRP (International Society of City and Regional Planners) Congress, Athens September 2002. Volos, Greece: University of Thessaly Press.

Brenner, N. (1998) ‘Global cities, glocal states: global city formation and state territorial restructuring in contemporary Europe’, Review of International Political Economy 5(1), pp. 1–37.

Castells, M. (1977) The Urban Question: A Marxist Approach. London: Edward Arnold.

Chant, C. (1989) Science, Technology and Everyday Life 1870–1950. London: Routledge (in association with The Open University).

Cosgrove, D. (1984) Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. London: Croom Helm.

Damisch, H. (2001) Skyline: The Narcissistic City. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Domosh, M. (1992) ‘Corporate cultures and the modern landscape of New York City’, in Inventing Places—Studies in Cultural Geography. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire, pp. 72–88.

Fainstein, S. (1994) The City Builders: Property, Politics & Planning in London and New York. Oxford: Blackwell.

Frampton, K. (1983) Modern Architecture 1851–1945. New York: Rizzoli International Publications.

Hall, P. (1996) ‘“The City of Theory” from Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Desiging in the Twentieth Century’, in R. LeGates and F. Stout (eds) The City Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 382–396.

Harvey, D. (1989a) The Condition of Postmodernity. Oxford: Blackwell.

Harvey, D. (1989b) ‘From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation in urban governance in late capitalism’, Geografiska Annaler 71, pp. 3–17.

Jencks, C. (2004) The Iconic Building: The Power of Enigma. London: Frances Lincoln.

Jencks, C. (2006) ‘The iconic building is here to stay’, City 10(1), pp. 3–20 .

Kaika, M. (2005) City of Flows: Nature, Modernity and the City. New York: Routledge.

Kaika, M. (2006) ‘Dams as symbols of modernization: the urbanization of nature between geographical imagination and materiality’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 96(2) (forthcoming).

Kaika, M. and Swyngedouw, E. (2000) ‘Fetishising the modern city: the phantasmagoria of urban technological networks’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24, pp. 120–138.

Keel, R.O. (2005) ‘Pruitt-Igoe and the end of modernity’, http://www.umsl.edu/∼ rkeel/010/pruitt-igoe.htm, accessed 15 November 2005.

Lees, L. (2001) ‘Towards a critical geography of architecture: the case of an ersatz colosseum’, Ecumene: A Journal of Cultural Geographies 8(1), pp. 51–86.

Lefebvre, H. (1994 [1974]) The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lucan, J. (2001) L’Architecture en France (1940–2000). Paris: Le Moniteur.

McNeill, D. (2002) ‘The mayor and the world city skyline: London’s tall buildings debate’, International Planning Studies 7, pp. 325–334.

McNeill, D. (2006) ‘Globalization and the ethics of architectural design’, City 10(1), pp. 49–58 .

Meejin Yoon, J. and Höweler, E. (2000) 1001 Skyscrapers. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Moulaert, F., Swyngedouw, E. and Rodriguez, A. (2003) The Globalised City. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schama, S. (1987) The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. London: Collins.

Schorske, C.E. (1981) Fin-de-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sklair, L. (2001) The Transnational Capitalist Class. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sklair, L. (2006) ‘Iconic architecture and capitalist globalization’, City 10(1), pp. 21–47 .

Swyngedouw, E. (2000) ‘Authoritarian governance, power and the politics of rescaling’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 18, pp. 63–76.

Tabb, W.K. and Sawers, L. (eds) (1984) Marxism and the Metropolis: New Perspectives in Urban Political Economy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vaxevanoglou, A. (1996) The Social Reception of Novelty: The Example of Electrification in Greece

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

KAIKA AND THIELEN: GENEALOGY OF URBAN SHRINES 69

During the Interwar Period. Athens: Centre for Modern Greek Studies, National Research Foundation of Greece.

von Hoffman, A. (2005) ‘Why they built the Pruitt-Igoe Project’, Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, http://www.soc.iastate.edu/sapp/PruittIgoe.html, accessed 15 November 2005.

Zukin, S. (1991) Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zukin, S. (1995) The Cultures of Cities. Oxford: Blackwell.

Maria Kaika is a lecturer in the School ofGeography, University of Oxford and aFellow of St Edmund Hall, Oxford, UK.Korinna Thielen is an architect at ArupUrban Design, London, UK.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

06:

55 1

9 Ju

ly 2

015

![Presentation by maria, silvia, maria shi]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/547a8906b4af9f8f5e8b481a/presentation-by-maria-silvia-maria-shi.jpg)