Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs) in Mobile...

Transcript of Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs) in Mobile...

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs) in Mobile Health:Key Components and Design Principles for Ongoing HealthBehavior Support

Inbal Nahum-Shani, PhD1& Shawna N. Smith, PhD2

& Bonnie J. Spring, PhD3&

Linda M. Collins, PhD4& Katie Witkiewitz, PhD5

& Ambuj Tewari, PhD6&

Susan A. Murphy, PhD7

# The Society of Behavioral Medicine 2016

AbstractBackground The just-in-time adaptive intervention (JITAI) isan intervention design aiming to provide the righttype/amount of support, at the right time, by adapting to anindividual’s changing internal and contextual state. The avail-ability of increasingly powerful mobile and sensing technolo-gies underpins the use of JITAIs to support health behavior, asin such a setting an individual’s state can change rapidly, un-expectedly, and in his/her natural environment.Purpose Despite the increasing use and appeal of JITAIs, amajor gap exists between the growing technological capabil-ities for delivering JITAIs and research on the developmentand evaluation of these interventions. Many JITAIs have beendeveloped with minimal use of empirical evidence, theory, or

accepted treatment guidelines. Here, we take an essential firststep towards bridging this gap.Methods Building on health behavior theories and the extantliterature on JITAIs, we clarify the scientific motivation forJITAIs, define their fundamental components, and highlightdesign principles related to these components. Examples ofJITAIs from various domains of health behavior research areused for illustration.Conclusion As we enter a new era of technological capacityfor delivering JITAIs, it is critical that researchers developsophisticated and nuanced health behavior theories capableof guiding the construction of such interventions. Particularattention has to be given to better understanding the implica-tions of providing timely and ecologically sound support forintervention adherence and retention.

Keywords Just-in-time adaptive intervention . Support .

Mobile health (mHealth) . Health behavior

Introduction

An emerging intervention design, the just-in-time adaptiveintervention (JITAI) holds enormous potential for promotinghealth behavior change. A JITAI is an intervention design thatadapts the provision of support (e.g., the type, timing, intensi-ty) “over time to an individual’s changing status and con-texts,” with the goal to deliver support “at the moment andin the context that the person needs it most and is most likelyto be receptive” [1]. Increasingly powerful mobile and sensingtechnologies underpin this intervention design [2]. They allowus to monitor the dynamics of an individual’s internal stateand context in real time and offer support flexibly in terms oftime and location [3]. JITAIs are increasingly being used to

* Inbal [email protected]

1 Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, AnnArbor, MI, USA

2 Division of General Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine andInstitute for Social Research, University of Michigan, AnnArbor, MI, USA

3 Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University,Evanston, IL, USA

4 TheMethodologyCenter andDepartment of HumanDevelopment&Family Studies, Penn State, State College, PA, USA

5 Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico,Albuquerque, NM, USA

6 Department of Statistics and Department of EECS, University ofMichigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

7 Department of Statistics, and Institute for Social Research, Universityof Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

ann. behav. med.DOI 10.1007/s12160-016-9830-8

support health behavior changes in domains such as physicalinactivity [4], alcohol use [5], mental illness [6], smoking [7],and obesity [8]. Despite JITAIs’ increasing use and appeal,research on their development and evaluation is in its earlystages. Many JITAIs have been developed with little empiricalevidence, theory, or accepted treatment guidelines [9].

To close the gap between the growing technical capabilitiesto deliver JITAIs and an understanding of their scientific under-pinnings, it is important to clarify why JITAIs are needed andhow their objectives differ from those of other intervention de-signs. This will help scientists build the empirical basis neces-sary to develop efficacious JITAIs and decide whether a JITAIis warranted in a particular setting [10]. Further, JITAI develop-ment requires multidisciplinary effort, involving clinicians, be-havioral scientists, engineers, statisticians, computer scientists,and human-computer interaction specialists. A unified lexiconcan help to foster communication across diverse perspectivesand facilitate better collaboration and scientific exchange [2].Finally, because JITAIs are multi-component interventions, it isimportant to clearly define the components that comprise them,so that investigators can attend to the utility of each component.Investigating the effectiveness of each component and howwelldifferent components work together is critical in the process ofoptimizing a multi-component intervention [11].

In this article, we clarify the scientific motivation for JITAIs,define their key components, and highlight important designprinciples relevant to these components. We also discuss empir-ical, theoretical, and practical challenges for constructing effica-cious JITAIs. We ground our discussion by providing examplesof JITAIs from various domains of health behavior research.Table 1 provides a summary of key terms and definitions.

Examples of JITAIs

JITAIs have been implemented and pilot tested in several do-mains of health behavior change. For example, FOCUS [15] isa smartphone behavioral intervention that provides illnessmanagement support to individuals with schizophrenia.FOCUS prompts individuals three times a day (via auditorysignals and visual notifications) to assess their status in fivetarget domains: medication adherence, mood regulation,sleep, social functioning, and coping with hallucinations.Once signaled, individuals can engage or ignore the prompt.If they engage, the system launches a brief assessment. Whenan assessment indicates that the individual is experiencingdifficulties, FOCUS recommends self-management strategiesto ameliorate the type of difficulties the individual endorsed;otherwise, FOCUS provides feedback and positive reinforce-ment. No intervention is offered if the individual ignores theprompt.

ACHESS [5] is a JITAI for supporting recovery from alco-hol use disorders. It provides 24-7 access via smartphone to a

wide variety of supportive services, including computerizedcognitive-behavioral therapy, web-links to addiction-relatedwebsites, and information on alcohol-free events in their com-munity. Global positioning system (GPS) technology trackswhen an individual approaches a high-risk location, namely alocation that the individual pre-specified as a place where s/heregularly obtained or consumed alcohol in the past (e.g., fa-vorite bar). If the individual approaches a high-risk location,ACHESS sends an alert to the individual asking him/her ifs/he wanted to be there; otherwise, no alerts are delivered.

Finally, SitCoach [16] is a JITAI for office workers inwhich messages encouraging activity are delivered via asmartphone. Software on the worker’s computer records un-interrupted computer time via mouse and keyboard activity. If30min of uninterrupted computer time occurs, the smartphonedelivers a persuasive message to raise the individual’s aware-ness of his/her sedentary behavior and encourage a walkingactivity; otherwise, no messages are delivered. SitCoach doesnot deliver a message if the individual received a message inthe past 2 hours, even if s/he exceeds the computer activitythreshold during that time.

Motivation for Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions

Various scientific fields have used different terms to describeinterventions that adapt the provision of support to an individ-ual’s changing internal and contextual state. These includedynamic tailoring [17], intelligent real-time therapy [18], anddynamically and individually tailored ecological momentaryinterventions [19]. Here, we use the term JITAI because itintegrates two concepts: “just-in-time” and “adaptive.”Attending to these concepts sheds light on the motivationunderpinning these interventions as well as the componentscomprising them.

In various scientific fields, including manufacturing [20]and education [21], the term “just-in-time support” is used todescribe an attempt to provide the right type (or amount) ofsupport, at the right time [22], namely neither too early nor toolate [23]. The motivation for this approach is grounded in theidea that timing plays an important role in determining wheth-er support provision will be beneficial. Timing is defined as“the moment (a static reference point in time) at which a phe-nomenon, process, or part of process starts or finishes” [24].Timing onset and offset demarcates a state that reflects theparticular condition(s) that someone or something is in at aparticular point or period of time [24]. Here, the concept oftiming is largely event-based, in that the answer to the ques-tion “when is the right time?” is defined by events or condi-tions (e.g., when the individual approaches a high-risk loca-tion) rather than by clock time (e.g., at 2 pm). Such events/conditions are unexpected—they repeat irregularly, in a man-ner that cannot be fully predicted [25]. For example, it is

ann. behav. med.

impossible to anticipate exactly when the individual will ap-proach a high-risk location. Hence, ongoing monitoring of theindividual is required in order to identify when these events/conditions occur (i.e., when support is needed).

The right time to provide support is determined by thetheory of change that is guiding support provision, namelyhow and why a desired change is expected to unfold over timein a particular context [26]. The flip-side of providing the righttype of support at the right time is providing nothing when thetime is wrong and never providing the wrong type of support[27]. This operationalizes the notion of eliminating waste,namely any activity/action that absorbs resources (e.g., time,effort) but adds no value to, or even disrupts the desired pro-cess [28].

Adaptation operationalizes how the provision of just-in-time support will be accomplished [29, 30]. Adaptation isdefined as the use of ongoing (dynamic) information aboutthe individual to modify the type, amount, and timing of sup-port [31]. To provide support just-in-time, the adaptation re-quires monitoring the individual to decide (a) whether theindividual is in a state that requires support; (b) what type(or amount) of support is needed given the individual’s state;and (c) whether providing this support has the potential todisrupt the desired process.

In the context of health behavior interventions, the use ofmobile technology to deliver just-in-time support is rooted intheoretical and practical perspectives suggesting that states ofvulnerability to adverse health events, as well states of

Table 1 Key terms anddefinitions Key term Definition

Intervention design The approach and specifics of an intervention program.

Just-in-time support Attempts to provide the right type of support, at the right time, whileeliminating support provision that is interruptive or otherwise notbeneficial

Individualization The use of information from the individual to select when and how tointervene.

Adaptation A dynamic form of individualization, whereby time-varying (dynamic)information from the person is used repeatedly to select interventionoptions over time.

Just-in-time adaptiveintervention (JITAI)

An intervention design aiming to provide just-in-time support, byadapting to the dynamics of an individual’s internal state and context.JITAIs operationalize the individualization of the selection anddelivery of intervention options based on ongoing assessments ofthe individual’s internal state and context. A JITAI includes 6 keyelements: a distal outcome, proximal outcomes, decision points,intervention options, tailoring variables, and decision rules.

State of vulnerability/opportunity A period of susceptibility to negative health outcomes (vulnerability)or to positive health behavior changes (opportunity).

Distal outcome The ultimate goal the intervention is intended to achieve; usually aprimary clinical outcome such as time to drug use/relapse or physicalactivity level.

Proximal outcomes The short-term goals the intervention is intended to achieve. Proximaloutcomes can be mediators, namely crucial elements in a pathwaythrough which the intervention can impact the distal outcome,and/or intermediate measures of the distal outcome.

Decision points Points in time at which an intervention decision must be made.

Tailoring variables Information concerning the individual that is used for individualization(i.e., to decide when and/or how to intervene).

Intervention options Array of possible treatments/actions that might be employed at anygiven decision point. This might include various types of support,from various sources, different modes of support delivery, variousamounts of support or different media deployed for support delivery.

Decision rules Away to operationalize the adaptation by specifying which interventionoption to offer, for whom, and when (i.e., under whichexperiences/contexts). The decision rules link the interventionoptions and tailoring variables in a systematic way.

Intervention engagement A “state of motivational commitment or investment in the client roleover the treatment process” [12].

Intervention fatigue A state of emotional or cognitive weariness associated with interventionengagement [13].

ann. behav. med.

opportunity for positive changes, can emerge rapidly (e.g.,over a few days, hours, minutes, even seconds [32–34]); un-expectedly (i.e., in an irregular manner [35]); and outside ofstandard treatment settings (for review, see [36]).

States of Vulnerability and States of Opportunity

Theories that focus on preventing adverse health outcomes,such as stress-vulnerability [37] and relapse prevention [38]theories, highlight the importance of properly addressingstates of vulnerability, namely periods of heightened suscep-tibility to negative health outcomes (e.g., unhealthy eating,heavy drinking). The emergence of a vulnerable state is adynamic process in which stable and transient influences in-teract. Stable factors refer to enduring predisposing influences,including both internal (e.g., personality, genetics) and con-textual (e.g., neighborhood safety, unemployment) factors thatincrease the odds that a person will experience an adversehealth outcome at some point in his/her life. In turn, transientinfluences precipitate a transition in vulnerability from latent(subthreshold) to manifest. Transient precipitating influencescan be both internal (e.g., how the person is feeling) and con-textual (e.g., location) [37, 38]. A vulnerable state can emergerapidly, unexpectedly, and in the individual’s natural environ-ment, as s/he encounters circumstances that precipitate his/herlongstanding vulnerability [39]. These precipitating circum-stances can vary between people and within a person overtime [32]. The JITAI aims to contain the vulnerable state andreturn the condition of vulnerability to latent.

One example of a JITAI that aims to address a vulnerablestate is FOCUS, which was motivated by evidence suggestingthat transient difficulties play an important role (along withstable factors such as biological predisposition) in the courseand outcomes of schizophrenia. Specifically, difficulties suchas fatigue and interpersonal conflict precipitate a transition to astate of vulnerability that signifies the patient’s increasing riskfor full symptomatic relapse and illness exacerbation. Thesedifficulties can emerge rapidly, unexpectedly, and outside ofstandard treatment settings. Further, these difficulties can takedifferent forms across individuals or even in the same individ-ual over time. For example, psychotic episodes might be trig-gered mainly by states of fatigue for some individuals and byinterpersonal conflict for others. Moreover, the individual maybe susceptible to relapse because s/he is experiencing sleepdifficulties at one time, and at another time because s/he forgotto take his/her medication. Hence, FOCUS aims to provide thetype of support needed to help the individual cope with thedifficulties s/he is experiencing, at the right time to break thelink between these precipitating circumstances, the emergenceof the vulnerable state, and its progression into full symptom-atic relapse.

JITAIs are also motivated by the importance of capitalizingon states of opportunity, namely periods of heightened

susceptibility to positive health behavior changes (e.g.,healthy eating, physical activity) [33, 34]. For instance, healthbehavior maintenance perspectives emphasize the importanceof anticipatory coping [40]—a dynamic process involving on-going anticipation of difficulties and timely execution of theright strategy to prevent and/or minimize temptation (e.g., adieter keeping healthy food in the refrigerator [39, 41]). Healthbehavior motivation theories suggest that it is important tobreak long-term health behavior goals into short-term, specif-ic, and achievable sub-goals; monitor progress; and providerelevant, timely feedback and guidance [35, 42]. Learning andcognitive theories emphasize the role of shaping (i.e., identi-fying and immediately reinforcing successively improving ap-proximations of the target behavior [43, 44]) and teachablemoments (i.e., natural opportunities for learning and improve-ment [45, 46]) in the acquisition of a new skill. Overall, theseperspectives emphasize that timely provision of interventionscaffolds and prompts can capitalize on short-term naturalopportunities to improve health outcomes. For example,SitCoach is motivated by evidence suggesting that the occur-rence of 30 min of uninterrupted computer use constitutes ateachable moment that can be framed to raise an officeworker’s awareness of his/her sedentarism. To capitalize onthis opportunity, when 30 min of sedentary behavior occurs,SitCoach provides feedback and persuasive messages to en-courage the worker to be more active.

Because states of vulnerability and/or opportunity canemerge rapidly, unexpectedly, and ecologically (i.e., in theindividual’s natural environment), it is usually infeasible touse in-person (face-to-face) approaches to identify the timewhen support is needed and to deliver the right type of supportin a timely manner. Hence, the provision of just-in-time sup-port in health behavior interventions relies heavily on the useof mobile and wireless devices (mHealth) [47]. The wide-spread use of technologies including smartphones, laptops,and tablets enables individuals to access or receive interven-tions anytime and anywhere [48]. Moreover, the portable na-ture of wearable and ubiquitous computing sensors (e.g.,wearable activity monitors, smartwatches), mobile-phone-based sensing (e.g., accelerometry, GPS), digital footprints(e.g., social media interactions, digital calendars), and low-effort self-reporting (e.g., ecological momentary assessment[EMA]) make it possible to monitor individuals continuouslyand hence to know when and why a state of vulnerability/opportunity emerges [49]. Even so, new challenges to inter-vention adherence and retention arise.

New Challenges to Intervention Adherence and Retention

Newly recognized challenges to intervention adherence andretention concern the use of mHealth to address states thatemerge rapidly, unexpectedly, and ecologically [19]. First, be-cause states of vulnerability/opportunity can occur repeatedly

ann. behav. med.

over time, providing support at the right time might suggestfrequent delivery of interventions [50]. Second, addressingthese states often requires the delivery of interventions in areal-life setting where multiple demands compete for the indi-vidual’s time and effort. Finally, to reduce costs and otherbarriers to treatment (e.g., availability of therapists, stigma),many mHealth interventions include minimal or no supportfrom clinicians or coaches (e.g., [51, 52]). This introducesunique challenges to the extent that supportive accountability(i.e., “implicit or explicit expectation that an individual maybe called upon to justify his/her actions or inactions” [53]) isenhanced by the felt presence of another human being [53].

Indeed, various studies demonstrate the law of attrition [54]in mHealth interventions, showing that individuals usemHealth resources only a few times before abandoning them[55, 56], even when they paid for these resources [57]. Forexample, in a randomized control trial, Laing and colleagues[58] compared a popular publically available app for weightloss with usual care for overweight patients in a primary caresetting. Although individuals reported liking the app, usedropped sharply after the first month. For example, the mediannumber of logins was eight in the first month and one in thesecond month; the number of individuals who actually usedthe app dropped by 64 % from month 1 to month 6. Hence,JITAIs in mobile health are also motivated by the need toaccommodate relatively rapid changes in key mechanismsunderlying intervention adherence and retention.

Intervention engagement and intervention fatigue are twoimportant mechanisms that affect adherence and retention.Intervention engagement is defined as a “state of motivationalcommitment or investment in the client role over the treatmentprocess” []. Intervention fatigue (i.e., burnout) is defined as astate of emotional or cognitive weariness associated with in-tervention engagement [13]. Empirical and theoretical evi-dence suggests that both mechanisms are important in inter-vention adherence and retention [14], and both might ebb andflow over the course of treatment as a function of aspectsrelated to the intervention, the individual, and the context[13, ]. For example, King and colleagues [] conceptualizeintervention engagement as a multifaceted affective, cogni-tive, and behavioral state that ebbs and flows over time dueto factors related to the intervention (e.g., how treatment ispresented and delivered), the individual (e.g., attitudes to-wards self and treatment), and the context (e.g., work/familydemands). Heckman and colleagues [13] conceptualize inter-vention fatigue as a cognitive and emotional state that fluctu-ates over time as a function of the interplay between interven-tion burden (i.e., the demands of an intervention in terms oftime and effort), the general demands on the individual (e.g.,daily life tasks related to work and family), the capacity of theindividual in terms of general resources (e.g., attention,mood), and illness burden (i.e., symptoms such as pain,craving).

Building on these ideas, and consistent with the notion ofwaste elimination, various perspectives in supportive commu-nication and ubiquitous computing [59–61] emphasize theneed to provide just-in-time support only when the person isreceptive. Here, receptivity is defined as the individual’s tran-sient ability and/or willingness to receive, process, and utilizejust-in-time support; receptivity is a function of both internal(e.g., mood) and contextual (e.g., location) factors [50]. Forexample, in FOCUS, support was not offered if the individualignored the prompt for self-report (i.e., s/he is not receptive).The underlying assumption is that providing support when theperson is not receptive will not be beneficial and may evenhave negative implications on engagement with the interven-tion and intervention fatigue [61, 62]. Receptivity mightchange rapidly in the course of a day [61], and what consti-tutes receptivity depends on the type (i.e., content, mediaemployed for delivery), amount, and timing of support pro-vided [63]. For example, if a person is in a meeting s/he mightbe receptive to an intervention delivered via a text message,but not receptive to a phone call. When it is raining, a personmight be receptive to a recommendation to exercise indoors,but not receptive to a recommendation to walk outside.

Summary of JITAI Definition and Scientific Motivation

A JITAI is an intervention design that employs adaptation tooperationalize the provision of just-in-time support, namely toprovide the right type (or amount) of support, at the right time,while eliminating support provision that is not beneficial. Theuse of mobile health (mHealth) in this setting is motivated bythe need to address states of vulnerability for adverse healthoutcomes and/or capitalize on states of opportunity thatemerge rapidly, unexpectedly, and ecologically. These statescan vary between individuals and over time within an individ-ual. Hence, addressing and/or capitalizing on these states in atimely manner requires continuous, ecological monitoring ofan individual’s internal state and context to identify when andhow to intervene. Advances in portable and pervasive tech-nologies make it possible to continuously monitor individuals,as well as the timely delivery of support “in the wild.”However, given the rapid, unexpected, and ecological natureof these states, as well as the law of attrition [54] in mHealthinterventions, JITAIs in mobile health are also motivated bythe need to address relatively rapid changes in mechanismsunderlying adherence and retention.

Notice that the definition above emphasizes that the adap-tation in a JITAI is employed by the intervention itself ratherthan by the target individual. In other words, decisionsconcerning when and how to provide support are based onthe intervention’s protocol. This intervention-determined ap-proach is based on evidence suggesting that individuals areoften unable to recognize when states of vulnerability and/oropportunity emerge [64, 65] and initiate the type of support

ann. behav. med.

needed to address these states in a timely manner [66, 67].Hence, a JITAI employs adaptation to actively address thesestates of vulnerability and/or opportunity. We distinguish thisfrom participant-determined approaches that make an array ofsupportive resources available for the target individual to de-cide when and what type of support to initiate.

Components of a JITAI

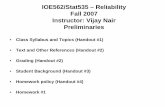

JITAIs are adaptive interventions. An adaptive intervention isan intervention design in which intervention options areadapted to address the unique and changing needs of individ-uals, with the goal of achieving the best outcome for eachindividual [68]. Existing frameworks for the design of adap-tive interventions [31] highlight four components that play animportant role in designing these interventions: (1) decisionpoints, (2) intervention options, (3) tailoring variables, and (4)decision rules. Below, we describe each of these componentsand how theymight be employed in a JITAI. Figure 1 includesa conceptual model of JITAI components.

Decision Points

A decision point is a time at which an intervention decision ismade. Given the nature of the conditions JITAIs in mobilehealth attempt to address and the capabilities of modern tech-nology, intervention decisions are made much more rapidlythan in standard adaptive interventions. For example, inFOCUS, intervention decisions were made following eachrandom prompt for self-report. An intervention was not nec-essarily provided following every random prompt: if the indi-vidual ignored the prompt (i.e., s/he was not receptive), nointervention was offered. Table 2 includes other examples ofdecision points in JITAIs. In general, the decision points in aJITAI might occur (a) at a pre-specified time interval (e.g., thelocation of a recovering individual is passively monitored ev-ery minute to detect if/when s/he is approaching a high-risk

location [5]); (b) at specific times of day (e.g., at 2 pm) [73], ordays of the week [70]; or (c) following random prompts [15].

Intervention Options

Intervention options are an array of possible treatments oractions that might be employed at any given decision point.In JITAIs, these include various types of support (e.g., infor-mation, advice, feedback), sources of support (e.g.,smartphone, therapist) , amounts of support (i .e . ,dose/intensity), or media employed to deliver support (e.g.,phone calls, text messaging). For example, intervention op-tions in FOCUS included both recommendations of self-management strategies, as well as feedback and positive rein-forcement. In a JITAI, intervention options are designed to bedelivered, accessed, and used in a timely and ecological man-ner. The term ecological momentary interventions (EMIs) isoften used to describe intervention options that can be deliv-ered and employed rapidly, as people go about their daily lives[19].

Tailoring Variables

A tailoring variable is information concerning the individualthat is used to decide when (i.e., under what conditions) toprovide an intervention and which intervention to provide. Forexample, in ACHESS, the tailoring variable is an individual’sdistance from a high-risk location. In a JITAI, the collection oftailoring variables is flexible in terms of the timing and loca-tion of assessments. This flexibility enables timely individu-alization of intervention options to conditions that mightchange rapidly, unexpectedly, and ecologically.

Tailoring variables in a JITAI can be obtained via activeassessments, passive assessments, or both [77]. Activeassessments, also known as EMAs, are self-reported andhence require engagement on the part of the individual [78].For example, in FOCUS, participants were prompted three

Fig. 1 Conceptual model ofJITAI components

ann. behav. med.

times a day to self-report the status of their difficulties.Passiveassessments are those that require minimal or no engagementon the part of the individual. For example, in ACHESS, themobile phone passively monitors the individual’s location.This information is used to determine when to send an alert.

Decision Rules

The decision rules in JITAIs operationalize the adaptation byspecifying which intervention option to offer, for whom, andwhen. In other words, the decision rules link the interventionoptions and tailoring variables in a systematic way. There is adecision rule for each decision point. For example (see Table 2for additional examples), a decision rule similar to those usedin ACHESS but simplified for expository purposes might beof the following form:

If distance to high-risk location ≤S0

Then, IO = [Provide an alert]

Else if distance to high-risk location >S0

Then, IO = [Provide nothing]

Notice that a decision rule includes the values (levels,thresholds, ranges) of the tailoring variable that determinewhich intervention option should be offered. In the aboveexample, S0 is the value of distance to high-risk location (thetailoring variable) that determines whether an alert should beoffered (if distance ≤S0), or not (if distance >S0). In otherwords, S0 specifies when (i.e., the conditions under which)an intervention should be offered. Next we discuss designprinciples that are important for constructing effective deci-sion rules in JITAIs.

Design Principles for JITAIs

We discuss design principles and considerations aimed at max-imizing the effectiveness of the JITAI; that is, the ability of theJITAI to achieve the desired distal outcome(s) when imple-mented in a real-world setting. The distal outcome is concep-tualized as the ultimate goal the intervention is intended toachieve; it is usually a primary clinical outcome, such as weightloss, drug/alcohol use reduction, or increase in average activitylevel. All the design principles discussed below should be guid-ed primarily by the distal outcome targeted by the JITAI.

The Role of Proximal Outcomes

Proximal outcomes are the short-term goals the interventionoptions are intended to achieve; they can be measured shortly

after the intervention is provided, with the aim of gaugingwhether the intervention is on track in achieving its objectives[79]. As we discuss below, identifying and clearly defining theproximal outcomes can help scientists select appropriate deci-sion points, tailoring variables, and intervention options andformulate effective decision rules. Proximal outcomes are of-ten mediators, namely critical elements in a causal pathwaythrough which the intervention options are designed to impactthe distal outcome [79]. For example, JITAIs aiming to pre-vent adverse health outcomes often focus on mediators thatmark the emergence of a vulnerable state. Such markers canbe in the form of transient conditions that precede an adversehealth outcome, such as mood symptoms (e.g., anxiety, dys-phoria) in a JITAI aiming to prevent symptomatic relapse inindividuals with schizophrenia [15]. Proximal outcomes canalso be intermediate measures of the distal outcome. For ex-ample, JITAIs aiming to promote the adoption and mainte-nance of healthy behaviors often target proximal outcomesthat capture short-term progress towards an ultimate healthbehavior goal (e.g., daily step count in a JITAI aimed at in-creasing average daily step count over the study duration[80]).

In many cases, there are multiple pathways through whichthe intervention can impact the distal outcome [81]. In thesecases, intervention scientists might select multiple proximaloutcomes to be targeted by the JITAI. For example, considera JITAI for improving eating habits as the distal outcome.Suppose this intervention is designed to target two proximaloutcomes: (1) momentary food craving, selected to mark astate of heightened vulnerability for unhealthy eating; and(2) engagement with (operationalized in terms of using) anintervention that is offered to help reduce snack food cravings.Note that this example includes two forms of proximal out-comes: the first is a mechanism that underlies the health con-dition, and the second relates to intervention adherence/reten-tion. Below, we elaborate on the inclusion of mechanisms thatunderlie intervention adherence/retention as proximal out-comes in a JITAI.

Proximal Outcomes Related to Intervention Adherenceand Retention

To prevent poor adherence to and/or abandonment of JITAIs,it is important that intervention scientists consider proximaloutcomes pertaining to intervention engagement and interven-tion fatigue [82]. These proximal outcomes might be behav-ioral (e.g., accessing and using the intervention), cognitive(e.g., perceiving the intervention as useful), or affective (e.g.,trust in the intervention) []. When selecting proximal out-comes pertaining to engagement, it is important to specifythe extent and duration of intervention engagement requiredin order to achieve the distal outcome. For example, certaininterventions require long-term engagement (e.g., a JITAI

ann. behav. med.

designed to support HIV medication adherence), whereasothers require relatively short-term engagement (e.g., aJITAIs designed to prevent smoking lapses in the weeks im-mediately after quitting).

There are a number of proximal outcomes that potentiallyreflect intervention fatigue. One concerns cognitive overload,namely experiences of excessive mental demands that impairthe ability to remember goals or think clearly about necessaryactions [83]. Another is habituation, namely objective declinein physiological and/or behavioral response to an interventionover repeated exposures [84]. A third involves negative emo-tions, such as boredom (a negative affective state involvinglack of interest in and difficulty concentrating on a given ac-tivity [85]), as well as other negative emotions, such as angerand disappointment, that reflect emotional exhaustion [86]and intervention fatigue [87].

Interestingly, while the connection between engagement andfatigue has received little systematic research in interventionscience, empirical evidence in the area of occupational health

psychology indicates that engagement and fatigue are two dis-tinct, yet related concepts that share certain antecedents andconsequences [88] and that influence each other in a complexway [89]. In some instances, signs of poor behavioral engage-ment, such as ignoring intervention prompts, signal interven-tion fatigue [90], as when the effort needed for repeated use ofintervention materials leads to mental exhaustion. On the otherhand, the motivational aspects of engagement have the poten-tial to prevent or attenuate intervention fatigue. For example,optimism and trust in the intervention can increase its perceivedvalue and the resources that the individual allocates to bear thedemands of the intervention. Analogously, interventions thatsucceed in fulfilling core psychological needs (e.g., curiosity;discussed below under intervention options) might keep theindividual engaged despite any mental weariness caused byintervention demands [13, 91].

Given the reciprocal nature of the link between interventionengagement and fatigue, and given that both play an importantrole in intervention adherence and retention, we recommend

Table 2 Examples of decision rules in JITAIs

Example Decision rule Decision point Tailoring variables Intervention options

Substance abuseintervention based oncomposite riskassessment

At random EMA promptIf composite substance abuse risk ≥R0Then, IO = [recommend intervention]

Else if composite substance abuse risk <R0Then, IO = [encouraging message]

Random prompt[15, 51]

Composite risk [69] Recommend interventionOR encouraging message[15, 70]

An individual doesnot access interventionwithin M minutes

At M minutes after random EMA promptIf composite risk ≥R0 and intervention use inpast M minutes = NOThen, IO = [message encouragingintervention use]

Else if risk <R0 or intervention use in pastM minutes = YESThen, IO = [provide nothing]

M minutes afterrandom prompt [71]

Composite risk [69];Intervention use inpast M minutes [72]

Message encouragingintervention use ORprovide nothing [72]

Physical activityintervention usingpassive assessmentsof step count

At 4 pmIf current accumulated step count <P0Then, IO = [recommend exercise]

Else if current accumulated step count ≥P0Then, IO = [encouraging message]

Specific time ofday [73]

Current accumulatedstep count [74]

Recommend exercise[75]

OR encouragingmessage [74]

Responding to passivelyassessed risky location,using activeassessments of urge

Every 3 min,If location = close to a liquor store,Then,

If self-report urge ≥U0

Then, IO = [send alert to sponsor]Else, if self-report urge <U0

Then, IO = [recommend an intervention]Else, if location = not close to a liquor storeThen, IO = [provide nothing]

Pre-specified timeinterval [5]

Passively assessedlocation [5];self-reportedurge [51]

Alert sponsor [5] ORrecommend anintervention [15] ORprovide nothing [5]

An individual ignoresrequest for assessment

At M minutes following a random promptIf EMA completion = NOThen, IO = [TXT encourage EMAcompletion]

Else if EMA completion = YESThen, IO = [provide nothing]

M minutes followingrandom prompt [71]

EMAcompletion [76]

Text encouraging EMAcompletion OR providenothing [76]

IO intervention option, EMA ecological momentary assessment, TXT text message

ann. behav. med.

that scientists attend to both concepts when selecting interven-tion options as well as proximal outcomes. Even though re-search in organizational and social psychology provides ex-tensive information on both phenomena [92], future researchshould continue to uncover processes related to engagementand fatigue in the context of behavioral interventions in gen-eral and JITAIs in particular to inform the selection of proxi-mal outcomes in a JITAI. Attention should also be given to themeasurement of intervention engagement and fatigue giventhe multifaceted nature of these constructs. Human-computerinteraction (HCI) frameworks provide useful guidelines [93],emphasizing that various assessment tools, including self-reports (e.g., affect), physiological sensors (e.g., eye move-ment tracking to measure visual attention), and interventionusage patterns (e.g., the number of features used in a mobileapplication), should be combined to capture the emotional,cognitive, and behavioral dimensions of user engagementand fatigue.

Decision Points

When selecting decision points, the first consideration shouldbe given to how often meaningful changes in the selectedtailoring variable(s) are expected to occur. Here, changes areconsidered meaningful if they have implications for whichintervention option should be recommended; such changesoften represent entry into and exit from a state of heightenedvulnerability or a state of opportunity. To clarify this, considerthe example decision rule above, where S0 is the value ofdistance from a high-risk location (the tailoring variable) thatdetermines whether an alert should be offered (if distance≤S0), or not (if distance >S0). Here, meaningful changes inthe tailoring variable would occur if an individual’s distancefrom a high-risk location reduces to a point S0, or increasesabove this threshold. The former indicates entry into a vulner-able state, which requires an intervention to prevent alcoholuse (the proximal outcome); the latter indicates exit from thisstate, so that an alert is not needed.

If distance from a high-risk location is expected to changein a meaningful manner every minute, then there might be adecision point every minute. Alternatively, if meaningfulchanges in the tailoring variable are expected to occur every30min, then theremight be a decision point every 30min. Thechoice of the time interval between decision points can have adramatic impact on the ability of the adaptation to achieve itsgoals. Important opportunities for intervention might bemissed if the timing of the decision points is not aligned withhow often meaningful changes in the tailoring variable(s) arelikely to occur.

When the tailoring variable is measured via active assess-ments, considerations of assessment burden may lead to lessfrequent decision points. For example, the selection of deci-sion points in FOCUS (i.e., at random prompts three times/

day) was intended to balance empirical evidence and theoriessuggesting that meaningful changes in mood symptoms (e.g.,depression and anxiety) among individuals with schizophre-nia are likely to occur rapidly (e.g., every few minutes) withconsiderations of burden (as well as quality of measurements)that might result from asking the individual to self-report toofrequently [15]. On the other hand, in ACHESS, meaningfulchanges in an individual’s location were expected to occurrapidly, and the passive measurement of location ensured min-imal burden. Therefore, the decision points are at very smallintervals in time (i.e., as often as 1 min, depending on howclose the individual is to the high-risk location).

Intervention Options

The intervention options included in a JITAI should be theo-retically and empirically driven, and they often target proxi-mal outcomes. Intervention options designed to impact mech-anisms that underlie the health condition, such as markers ofstate vulnerability or short-term clinical progress, are oftendeveloped on the basis of multiple health-behavior and copingtheories (see [94] for a full review). Although interventionoptions targeting proximal outcomes related to adherenceand retention might benefit from being based upon theoriesconcerning intervention engagement and fatigue [82], thisrarely occurs. Hence, we elaborate below on design consider-ations for these intervention options.

Intervention Options Targeting Engagement and/or Fatigue

Research in occupational health psychology provides a usefulframework for disentangling design considerations that pri-marily concern engagement from those that primarily concernfatigue. This line of research (see [92]) suggests that whileengagement and fatigue are related, engagement can beprompted primarily by efforts to fulfill basic psychologicalneeds, such as the needs for autonomy, relatedness, and com-petence, whereas intervention fatigue can be prevented andameliorated primarily by attending to the demands imposedon the individual in terms of time and effort (also referred to asintervention burden; see [13]). These ideas are echoed in re-cent conceptualizations of engagement and fatigue in the con-text of behavioral interventions [13, ].

To promote engagement, various strategies can be used inJITAIs to design intervention options that fulfill basic psycho-logical needs. For example, competence, which concerns in-dividual feelings of efficacy, challenge, and curiosity [95], canbe promoted by providing immediate feedback or rewards[96]; by ensuring that intervention options can be readily in-corporated into and used in the context of the individual’sdaily living activities [57, 97]; and by ensuring that interven-tion options maintain an optimal level of challenge to generatesufficient interest yet avoid frustration or failure [98].

ann. behav. med.

Relatedness, which concerns feelings of being connected toand cared about by others [99], can be promoted by facilitatingsupportive social interactions (e.g., creating online communi-ties [100]). Autonomy, namely experiencing an internal per-ceived locus of causality or the self-endorsement of one’saction [101], can be promoted by facilitating user agencythough participation (e.g., incorporating user preferences inintervention options [102]). Throughout, literature in the areaof persuasive computing can be used to guide the develop-ment of intervention options that fulfill basic psychologicalneeds by using games, augmented reality, and digital avatarsin the form of personal coaches and assistants [103].

To address intervention fatigue, various strategies can beemployed to minimize the emotional, cognitive, and physio-logical demands JITAIs impose on an individual (see [13]).For example, to minimize cognitive overload, it is importantto develop intervention options that are intuitive and easy tonavigate [6] and that include content that is brief and clear[104]. This is particularly important when the target popula-tion has less education, impaired cognitive functioning, and/orless experience with computerized and mobile devices [6].

Varying of the form, presentation, and timing of contentdelivery is a useful strategy for dealing with both engagementand fatigue [105]. For example, instead of delivering the samecontent multiple times, the JITAI might draw from a “bank”that includes various forms of relevant content [106].Additionally, the JITAI might vary the type of mediaemployed or the type of signal (e.g., alerts, pings) used toengage the individual with the content [107]. Enhancing nov-elty and allowing mental rest introduces variability that canfulfill basic psychological needs (e.g., curiosity), while mini-mizing boredom, habituation, and general loss of energy [91].A related strategy involves the explicit inclusion of a providenothing intervention option in a JITAI—an intervention op-tion that provides no intervention at a decision point. Thisintervention option can be incorporated into the decision rulesto address conditions where the provision of support may havenegative effects on intervention engagement and fatigue. Thisincludes situations in which the person is unreceptive, as wellas conditions in which support is not needed (e.g., because theperson is doing well). A “provide nothing” option can also beused to address situations in which the provision of certaintypes of just-in-time support might be unsafe or unethical(e.g., audibly prompting the person to interact with a messageon the phone when the person is driving a car; for more detailssee [50]).

Tailoring Variables

In this section, we discuss selection of tailoring variables in aJITAI, measurement of the tailoring variables in a JITAI, andmissing data on tailoring variables.

Selection of Tailoring Variables

Tailoring variables should be selected based on evidence(practical, clinical, theoretical, and/or empirical) indicatingthat a particular variable is useful for making interventiondecisions. By “useful” we mean that the variable (e.g., foodcraving) can be used to identify specific conditions (e.g., highfood craving) in which individuals are likely to benefit fromone intervention option (e.g., prompting a craving-reductionimagery intervention [108]) as opposed to another (e.g., pro-vide nothing) in terms of affecting the proximal outcome (e.g.,daily unhealthy snacking).

The selection of tailoring variables should also be guidedby the proximal outcomes. In JITAIs targeting proximal out-comes that mark the emergence of a vulnerable state (e.g.,alcohol craving), useful tailoring variables are typically thosethat help identify conditions that represent heightened suscep-tibility that precede the selected proximal outcome(s) (e.g.,approaching a location associated with past alcohol abuse;[5]); in JITAIs targeting proximal outcomes in the form ofshort-term health-behavior progress (e.g., daily step count),useful tailoring variables are typically those that help identifyconditions that represent heightened opportunity for short-term improvement (e.g., the person has been sedentary for30 min; [75]).

As discussed earlier, JITAIs are often designed to influencemore than one proximal outcome, in which case different tai-loring variables may be considered for different proximal out-comes. Note that the intervention options required to influenceeach proximal outcome might differ as well. As a simple ex-ample, assume that an intervention scientist is developing aJITAI to produce weight loss (distal outcome) by reducing thenumber of unhealthy snacking episodes per day (proximaloutcome). To maximize intervention adherence/retention, thescientist aims to minimize a second proximal outcome, inter-vention fatigue. To address the former, a different encouragingmessage would be offered at the end of each day depending onthe number of unhealthy snacking episodes during that day(tailoring variable). In the case of the later, a provide nothingintervention option would be usedwhen information about theindividual indicates that s/he is not receptive (tailoring vari-able); this includes when s/he ignores a prompt.

In many cases, it is reasonable to use the proximal outcomeas a tailoring variable. In the example above, the individual’scurrent number of snacking episodes (tailoring variable) isused to individualize the intervention options so as to reducesubsequent snacking episodes (proximal outcome). This ismotivated by the notion that information about the proximaloutcome at a given time point is useful in identifying condi-tions that represent heightened susceptibility for adverse con-sequences, or heightened opportunity for positive changes, interms of the proximal outcome at later time points/periods(e.g., experiencing a large number of snacking episodes on a

ann. behav. med.

given day is associated with increased odds of experiencing alarge number of snacking episodes in the following day). Ingeneral, the decision rules in a JITAI can use informationabout previous or current values of a proximal outcome toindividualize the intervention options. However, tailoring var-iables are not limited to the proximal outcomes targeted by theintervention. To clarify, assume the intervention scientist fromthe example above also decides to offer a craving-reductionimagery intervention when the person experiences high foodcraving (tailoring variable) in order to reduce the number ofsnacking episodes the individual experiences per day (proxi-mal outcome). Here, the tailoring variable differs from theproximal outcome.

Measurement of Tailoring Variables

When using active assessment to measure tailoring variables,it is helpful to carefully consider the dynamic theories thatinformed the selection of the tailoring variables. Suppose aninvestigator constructs a JITAI using emotion-regulation in-tervention options to reduce unhealthy snacking and decidesto use active assessment of momentary negative affect as atailoring variable. In this setting, negative affect is conceptu-alized as a dynamic, fluctuating, state construct, with meaningand operationalization that differ from the more static con-struct of trait negative affect [109]. Active assessment of adynamic construct can be challenging. For example, individ-uals may skim over or even ignore parts of an instrument thatis presented several times daily [110], possibly reducing mea-surement reliability and validity. Potential adverse effects re-lated to the response burden of repeated assessment must bebalanced against the need to measure the construct frequentlyenough to obtain an accurate picture of the dynamic processunderlying mood state changes.

Passive assessment of tailoring variables is becoming morefeasible as sensors of various kinds become more sophisticat-ed and cost-effective. Smartphones include a wide range ofsensors (e.g., accelerometer, camera), which can be used tomeasure the individual’s state and context [111]. Capitalizingon these smartphone sensors and other types of sensors (e.g.,ECG, galvanic skin response sensors (see also Sun et al. [112])could considerably reduce the burden of obtaining informa-tion about the individual’s state and context.

When sensors are used to measure the tailoring variable,the person’s value on the tailoring variables at a particulardecision point would often be the output of a machine learn-ing algorithm, such as support vector machine (SVM),which is used to process the raw data acquired through thesensors and classify the person’s state and context. Kumarand colleagues [113] provide a comprehensive review ofthese procedures, illustrating the process by which heart beatpatterns captured by ECG and sensor-based data on respira-tion patterns can be used to classify stress episodes [114],

conversations [115], and smoking puffs [116]. Tapia andcolleagues [117] provide a detailed discussion of how datacaptured by simple and ubiquitous sensors (e.g., door con-tact sensors on the fridge storing a timestamp each time thedoor is opened or closed) can be used to classify everydayactivities in the home setting (e.g., eating).

Regardless of whether the assessment of a tailoring vari-able is active, passive, or both, careful consideration must begiven to reliability and validity. Recall that the decision rulesin a JITAI provide the link between the tailoring variable andthe best intervention option. Valid and reliable tailoring vari-ables are required in order for the decision rule to recommendthe best intervention option. When one or more tailoring var-iables are measured unreliably, the decision rule will performlittle better than randomly selecting an intervention option,and when one or more of the tailoring variables are invalid,the decision rule may even recommend a counterproductiveintervention option (for more details see [31]).

Missing Data on Tailoring Variables

When designing a JITAI, scientists should anticipate and planthe functioning of the decision rule when measurements onthe tailoring variables are missing. Missing data can occur forvarious technical reasons [118, 119], including data corruption(e.g., loss of data due to technical problems associated withhow the data are stored); device detection failures (relevant inpassive data collection where the sensing device fails becauseof technical limitations; e.g., absent mobile phone reception,battery failure); and human error (e.g., incorrectly using thedevice, failure to correctly self-monitor). Missing data canalso occur due to poor engagement (e.g., individuals whoare not engaged in a weight loss program are less likely toself-report food intake) and/or intervention fatigue (e.g., indi-viduals not providing self-monitoring information becauseself-monitoring is too burdensome). In the last two cases, in-dicators of missingness may be used as tailoring variables thatreflect poor engagement and/or intervention fatigue. In allcases, it is important to anticipate situations that may lead tomissing data and ensure that the decision rules cover thesesituations.

Characteristics of Good Decision Rules in a JITAI

Good decision rules are based on an accurate and comprehen-sive scientific model that articulates experiences and contextsin which a person is likely to benefit from one interventionoption vs. another in terms of the proximal outcomes. Thisscientific model should build on evidence concerning the dy-namics of the health condition, as well as the dynamics ofintervention adherence and retention. Specifically, it is impor-tant that researchers understand what constitutes a state ofvulnerability and/or a state of opportunity, the temporal

ann. behav. med.

process by which these states emerge and relate to the distaloutcome, and possible interventions that can be employed toaddress or capitalize on this process. An example involvesunderstanding facilitators and barriers to adopting healthy eat-ing habits, how and to what extent these facilitators/barriersmight change over time, and the intervention options that canbe employed just-in-time to capitalize on these understand-ings. Also important is the challenge of achieving adherenceand retention to a just-in-time intervention. It is imperative tounderstand how and why intervention engagement and fatiguefluctuate over time, how these fluctuations impact the distaloutcome(s), and what strategies can enhance engagement andreduce fatigue. Integrating evidence about both aspects of theclinical challenge—how to positively shape the dynamics ofthe health condition and how to redress dynamic barriers tointervention adherence/retention—lies at the heart of formu-lating good decision rules in a JITAI.

Challenges and Directions for Future Research

A major gap that hinders the development of efficaciousJITAIs lies in the static nature of existing behavioral and in-tervention theories [10] and the lack of temporal specificity oftheories that are more dynamic in nature. As discussed earlier,the development of an efficacious JITAI can be guided by ascientific model that integrates evidence concerning (a) thedynamics of the health condition and (b) adherence and reten-tion in just-in-time interventions. However, most existingempirical/theoretical perspectives are not dynamic—they treatthe mechanisms underlying health conditions and interventionadherence/retention as relatively stable, allowing them to vary,at most, as a function of baseline variables, such as personalcharacteristics (e.g., age, gender) and baseline symptom se-verity [9]. Even when existing theories or perspectives ac-knowledge the dynamic nature of underlying health conditionand behavior change mechanisms, they often do not articulatehow and to what extent these mechanisms might change overtime and what kind of support should be offered to addressthem in a timely manner.

For example, consider emotional distress, a potential mark-er of an emerging state of vulnerability [37]. Althoughexisting theories acknowledge that emotional distress is a dy-namic construct that changes over time and hence needs to beregularly monitored and addressed, current theories andmodels do not specify its temporal dynamics (e.g., what con-stitutes meaningful changes in distress, how rapidly suchchanges are likely to occur [120, 121]). Moreover, althoughvarious types of evidence-based interventions exist to preventor ameliorate distress, their translation and effective imple-mentation in a just-in-time format would benefit from beinginformed by dynamic theories of intervention adherence/retention to guide the type, timing, and amount of support

provision. Achieving such theoretical integration can be chal-lenging, given that dynamic and comprehensive models of themechanisms underlying intervention adherence/retention arerare and incomplete.

Of course, the lack of temporal specificity of current theo-ries is only part of the story. Despite their limitations, currenthealth behavior theories play a central role in the creation ofbehavior change and maintenance strategies [122], and apply-ing them to build JITAIs has the potential to result in betteroutcomes compared to JITAIs that are not theoreticallygrounded [34, 123, 124]. However, many JITAIs lack theappropriate theoretical basis, perhaps due to the limited expo-sure of mobile application developers to health behavior the-ories [9]. While there are various theoretical overviews [125]and examples [126] that can guide JITAI developers, moreattention should be given to developing cross-disciplinary col-laborations to facilitate the appropriate use of theory in build-ing JITAIs.

To facilitate the integration of current health behavior the-ories in JITAI construction, as well as the development of newtheories and scientific models, a number of approaches havebeen proposed to organize existing evidence and identify openscientific questions [127]. These approaches require clear ex-plication not only of the relationship between factors influenc-ing the dynamics of the health condition (e.g., whether distressinfluences smoking), but also of how this relationship mani-fests and evolves at different timescales. A timescale is de-fined here as the size of the temporal interval within which aprocess, pattern, phenomenon, or event occurs (e.g., a day, aweek) [50]. Specifically, timescale considerations require thatJITAI developers think through the key mechanisms underly-ing the health condition, as well as the key mechanisms un-derlying intervention adherence/retention, and seek to articu-late how they unfold over time towards the distal outcome.This can be facilitated by specifying key factors and effectswithin and between various timescales. These frameworks canbe used not only to organize existing evidence in a way that isuseful for JITAI development, but also to identify directionsfor further research that can build the foundation for moredynamic health behavior theories.

Building the empirical basis to construct such dynamicmodels requires study designs and analytic methods that cap-italize on the rich, fine-grained, temporal data that can now becollected with ubiquitous mobile and wireless technology. Forexample, data analysis methods from engineering and statis-tics [122, 128, 129] can inform the construction of dynamicbehavioral models. Smith and Walls [130] provide an exten-sive review of study designs and data analytic methods thatcan be used with data frommobile health studies to inform thedevelopment of scientific models for JITAI construction.

Study designs and data analytic methods to understand thecausal effects of intervention options are needed as well. Forexample, recently Murphy and colleagues [131] introduced the

ann. behav. med.

micro-randomized trial (MRT) design—a form of a sequentialfactorial design that involves random assignment of interventionoptions at numerous decision points. This trial design allowsinvestigators to address scientific questions concerning the caus-al effect on proximal outcomes of providing an interventionoption compared to the alternative and whether this effect variesdepending on an individual’s internal state and context.

Other data analytic methods emerging in computer scienceare designed to continually re-adapt; that is, update the JITAIdecision rules to an individual over time as s/he experiencesthe intervention. For example, MyBehavior [132] is a lifestylemobile intervention that uses a “multi-armed bandit” dataanalysis method to modify decision rules as user behaviorchanges in the course of the intervention. MyBehavior usessensor data to suggest a frequent behavior (e.g., walking)when the person is in a particular location and life context(e.g., on the way home after work). However, it also occasion-ally prompts infrequent higher-energy-expending behaviorsthat the person does only rarely (e.g., running) to allow thedata analytic methods to learn whether the person would re-peat these behaviors. If the person repeats these behaviors, thedecision rule is modified so that the new, higher-energyexpending behavior is recommended (instead of walking)when the person is in a particular context (e.g., after workhours).

Experimental and data analytic methods are evolving rap-idly, offering increasingly exciting opportunities to improvethe effectiveness of JITAIs and the utility of the scientificmodels that inform the design of these interventions.However, as noted byKaplan and Stone [133], “most psychol-ogists were trained to use statistical inference techniques de-signed for the study of agronomy in the 1930s.” Accordingly,greater attention should be given not only to the developmentof new methodologies but also to training the next generationof researchers in study designs and analytic methods that aresuitable for mobile health data.

Finally, a JITAI is defined in this manuscript as an inter-vention design in which decisions concerning when and howto provide support are intervention-determined rather thanparticipant-determined. While this definition excludes inter-ventions that rely solely on the individual’s initiative to accessand select from available supportive resources, adding someparticipant-determined features to a JITAI might have advan-tages. These include the ability to accommodate conditions inwhich the target individual is in the best position to knowwhatkind of support is needed and when, facilitate autonomousregulation by giving the individual control over the supportiveprocess, and introduce minimal waste and disruption (assum-ing individuals do not initiate support when they are unrecep-tive) [134]. Additional research is needed to investigate howto best add participant-determined features to a JITAI, so as tobalance the provision of planned, externally initiated supportwith personal volition and agency [134].

Conclusion

This article articulates the scientific motivation and key com-ponents of interventions that use mobile devices to offer sup-port in a timely, adaptive, and ecologically attuned manner. Aswe enter a new era that presents the technological capacity toindividualize and deliver just-in-time interventions, there iscritical need for sophisticated, nuanced psychological andhealth behavior theories capable of guiding the constructionof such interventions. Providing timely and ecologicallysound support for intervention adherence and retention holdsthe potential to counteract the law of attrition fromtechnology-supported interventions.

Acknowledgments We thank Daniel Almirall, Dror Ben-Zeev,Andrew Isham, and Dave Gustafson for their helpful feedback and ad-vice. This project was supported by awards R01 DA039901, R01AA022113, R01 HD073975, R21 AA018336, R01 AA023187, R01HL125440, U54 EB020404, R01 DK108678, R01 DK097364, P50DA039838, P01 CA180945, R01 DK097364, and R01 AA022931 fromthe National Institutes of Health, and awards IIS-1452099 and IIS-1545751 from the National Science Foundation. The content is solelythe responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent theofficial views of the funding organizations.

Compliance with ethical standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence toEthical Standards Authors Nahum-Shani, Smith, Spring,Collins, Witkiewitz, Tewari, and Murphy declare that they haveno conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informedconsent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethicalstandards of the responsible committee on human experimentation(institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of1975, as revised in 2000.

References

1. Spruijt-Metz D,WenC, O’Reilly G, et al. Innovations in the use ofinteractive technology to support weight management. Curr ObesRep. 2015; 4(4): 510-519.

2. Spruijt-Metz D, Nilsen W. Dynamic models of behavior for just-in-time adaptive interventions. Pervasive Comput IEEE. 2014;13(3): 13-17.

3. Kumar S, Nilsen WJ, Abernethy A, et al. Mobile health technol-ogy evaluation: The mHealth evidence workshop.Am J PrevMed.2013; 45(2): 228-236.

4. Consolvo S, McDonald DW, Toscos T, et al. Activity sensing inthe wild: A field trial of ubifit garden. 2008.

5. Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih M-Y, et al. A smartphoneapplication to support recovery from alcoholism: A randomizedclinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014; 71(5): 566-572.

6. Ben-Zeev D, Kaiser SM, Brenner CJ, Begale M, Duffecy J, MohrDC. Development and usability testing of FOCUS: A smartphonesystem for self-management of schizophrenia. Psychiatr RehabilJ. 2013; 36(4): 289.

ann. behav. med.

7. Riley W, Obermayer J, Jean-Mary J. Internet and mobile phonetext messaging intervention for college smokers. J Am Coll Heal.2008; 57(2): 245-248.

8. Patrick K, Raab F, Adams MA, et al. A text message-based inter-vention for weight loss: Randomized controlled trial. J MedInternet Res. 2009;11(1).

9. Riley WT. Theoretical models to inform technology-based healthbehavior interventions. Behav Health Care Technol: Using Sci-Based Innov Transform Pract. 2014;13.

10. Riley WT, Rivera DE, Atienza AA, Nilsen W, Allison SM,Mermelstein R. Health behavior models in the age of mobile in-terventions: Are our theories up to the task? Transl Behav Med.2011; 1(1): 53-71.

11. Collins LM, Nahum-Shani I, Almirall D. Optimization of behav-ioral dynamic treatment regimens based on the sequential, multi-ple assignment, randomized trial (SMART). Clinical Trials.2014;1740774514536795.

12. King G, Currie M, Petersen P. Child and parent engagement in themental health intervention process: A motivational framework.Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2014; 19(1): 2-8.

13. Heckman BW, Mathew AR, Carpenter MJ. Treatment burden andtreatment fatigue as barriers to health.Curr Opin Psychol. 2015; 5:31-36.

14. Kreyenbuhl J, Nossel IR, Dixon LB. Disengagement from mentalhealth treatment among individuals with schizophrenia and strat-egies for facilitating connections to care: A review of the literature.Schizophr Bull. 2009; 35(4): 696-703.

15. Ben-Zeev D, Brenner CJ, BegaleM, Duffecy J,Mohr DC,MueserKT. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of asmartphone intervention for schizophrenia. SchizophreniaBulletin. 2014.

16. Dantzig S, Geleijnse G, Halteren AT. Toward a persuasive mobileapplication to reduce sedentary behavior. Pers Ubiquit Comput.2013; 17(6): 1237-1246.

17. Kennedy CM, Powell J, Payne TH, Ainsworth J, Boyd A, BuchanI. Active assistance technology for health-related behavior change:An interdisciplinary review. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(3).

18. Kelly J, Gooding P, Pratt D, Ainsworth J, Welford M, Tarrier N.Intelligent real-time therapy: Harnessing the power of machinelearning to optimise the delivery of momentary cognitive–behav-ioural interventions. J Ment Health. 2012; 21(4): 404-414.

19. Heron KE, Smyth JM. Ecological momentary interventions:Incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health be-haviour treatments. Br J Health Psychol. 2010; 15(1): 1-39.

20. Monden Y. Toyota Production System: An Integrated Approach toJust-in-Time. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2011.

21. Novak GM, Patterson ET, Gavrin AD, Christian W. Just-in-timeteaching blending active learning with web technology. 1999.

22. Hoffmann B, Ritchie D. Using multimedia to overcome the prob-lems with problem based learning. Instr Sci. 1997; 25(2): 97-115.

23. Hulshof CD, De Jong T. Using just-in-time information to supportscientific discovery learning in a computer-based simulation.Interact Learn Environ. 2006; 14(1): 79-94.

24. Quintens L, Matthyssens P. Involving the process dimensions oftime in case-based research. IndMarkManag. 2010; 39(1): 91-99.

25. Ancona DG, Okhuysen GA, Perlow LA. Taking time to integratetemporal research. Acad Manag Rev. 2001; 26(4): 512-529.

26. Funnell SC, Rogers PJ. Purposeful Program Theory: EffectiveUse of Theories of Change and Logic Models. Vol. 31.Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2011.

27. Pauker SG, Zane EM, Salem DN. Creating a safer health caresystem: Finding the constraint. JAMA. 2005; 294(22): 2906-2908.

28. Turnbull P, Oliver N, Wilkinson B. Buyer‐supplier relations in theUK‐automotive industry: Strategic implications of the Japanesemanufacturing model. Strateg Manag J. 1992; 13(2): 159-168.

29. McCuaig J, Cordick A. Scaffolding for experts: Trial not error.Paper presented at: Proceedings of World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and HigherEducation. 2007.

30. Rummel N, Weinberger A, Wecker C, et al. New challenges inCSCL: Towards adaptive script support. Paper presented at:Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on InternationalConference for the Learning Sciences. Vol. 3. 2008.

31. Collins LM, Murphy SA, Bierman KL. A conceptual frameworkfor adaptive preventive interventions. Prev Sci. 2004; 5(3): 185-196.

32. Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA. Dynamic self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: Prediction of smoking lapseand relapse. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005; 114(4): 661.

33. AbrahamC,Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniquesused in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008; 27(3): 379.

34. Webb T, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet topromote health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior changetechniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res.2010; 12(1): e4.

35. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. HealthEduc Behav. 2004; 31(2): 143-164.

36. Campbell ANC, Muensch F, Nunes E. Technology-based behav-ioral interventions for alcohol and drug use problems. BehavHealth Care Technol: Using Sci-Based Innov Transf Pract.2014;40.

37. Zubin J, Spring B. Vulnerability: A new view of schizophrenia. JAbnorm Psychol. 1977; 86(2): 103.

38. Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for alcohol anddrug problems: That was zen, this is tao. Am Psychol. 2004;59(4): 224-235.

39. Shiffman S. Conceptual issues in the study of relapse. In: GossopM, ed. Relpse and Addictive Behavior. New York: Routledge;1989: 149-179.

40. Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. AnnuRev Psychol. 2004; 55: 745-774.

41. Shiffman S. Dynamic influences on smoking relapse process. JPers. 2005; 73(6): 1715-1748.

42. Strecher VJ, Seijts GH, Kok GJ, et al. Goal setting as a strategy forhealth behavior change. Health Educ Behav. 1995; 22(2): 190-200.

43. Krueger KA, Dayan P. Flexible shaping: How learning in smallsteps helps. Cognition. 2009; 110(3): 380-394.

44. Skinner BF. The Behavior of Organisms: An ExperimentalAnalysis. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1938.

45. Lawson PJ, Flocke SA. Teachable moments for health behaviorchange: A concept analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2009; 76(1): 25-30.

46. McBride C, Emmons K, Lipkus I. Understanding the potential ofteachable moments: The case of smoking cessation. Health EducRes. 2003; 18(2): 156-170.

47. Diez-Canseco F, Zavala-Loayza JA, Beratarrechea A, et al. Designand multi-country validation of text messages for an mHealthintervention for primary prevention of progression to hypertensionin Latin America. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015;3(1).

48. Patrick K, Intille SS, Zabinski MF. An ecological framework forcancer communication: Implications for research. J Med InternetRes. 2005;7(3).

49. Hekler EB, Klasnja P, Froehlich JE, Buman MP. Mind the theo-retical gap: Interpreting, using, and developing behavioral theoryin HCI research. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the SIGCHIConference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2013.

50. Nahum-Shani I, Hekler E, Spruijt-Metz D. Building health behav-ior models to guide the development of just-in-time adaptive

ann. behav. med.

interventions: A pragmatic framework. Health Psychol. 2015;34(Supp): 1209-1219.

51. Witkiewitz K, Desai SA, Bowen S, Leigh BC, Kirouac M,Larimer ME. Development and evaluation of a mobile interven-tion for heavy drinking and smoking among college students.Psychol Addict Behav. 2014; 28(3): 639.

52. Thomas JG, Wing RR. Health-e-call, a smartphone-assisted be-havioral obesity treatment: Pilot study. JMIR mHealth uHealth.2013;1(1).

53. Mohr DC, Cuijpers P, Lehman K. Supportive accountability: Amodel for providing human support to enhance adherence toeHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1).

54. Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(1).55. Fukuoka Y, Gay C, Haskell W, Arai S, Vittinghoff E. Identifying

factors associated with dropout during prerandomization run-inperiod from an mHealth physical activity education study: ThemPED trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015;3(2).

56. Owen JE, Jaworski BK, Kuhn E, Makin-Byrd KN, Ramsey KM,Hoffman JE. mHealth in the wild: Using novel data to examine thereach, use, and impact of PTSD Coach. JMIR Mental Health.2015; 2(1): e7.

57. Dunbrack L. Will the convergence of mobile and consumer en-gagement technologies lead to better health outcomes? In: KrohnR, Metcalf D, eds. mHealth Innovation: Best Practices from theMobile Frontier. Chicago: HIMSS; 2014.

58. Laing BY, Mangione CM, Tseng C-H, et al. Effectiveness of asmartphone application for weight loss compared with usual carein overweight primary care patients: A randomized, controlledtrial. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 16(10_Supplement): S5-S12.

59. Ho J, Intille SS. Using context-aware computing to reduce theperceived burden of interruptions from mobile devices.Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors inComputing Systems. Portland, Oregon, USA; 2005

60. McIntosh BS, Seaton RAF, Jeffrey P. Tools to think with?Towards understanding the use of computer-based support toolsin policy relevant research. Environ Model Softw. 2007; 22(5):640-648.

61. Sarker H, Sharmin M, Ali AA, et al. Assessing the availability ofusers to engage in just-in-time intervention in the natural environ-ment. 2014.

62. Pejovic V, Musolesi M. InterruptMe: Designing intelligentprompting mechanisms for pervasive applications. Paper present-ed at: Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International JointConference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing; 2014.

63. Fischer JE, Yee N, Bellotti V, Good N, Benford S, Greenhalgh C.Effects of content and time of delivery on receptivity to mobileinterruptions. 2010.

64. Goldstein RZ, Bechara A, Garavan H, Childress AR, Paulus MP,Volkow ND. The neurocircuitry of impaired insight in drug addic-tion. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009; 13(9): 372-380.