Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX September 2001 ...

Transcript of Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX September 2001 ...

Journal of Economic LiteratureVol. XXXIX (September 2001), pp. 869–896

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of AlliancesJournal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

Economics of Alliances: The Lessonsfor Collective Action

TODD SANDLER and KEITH HARTLEY1

1. Introduction

IN MARCH 1999, the North AtlanticTreaty Organization (NATO) admitted

three new members—the Czech Repub-lic, Hungary, and Poland—thus expand-ing the membership to nineteen allies.2Although NATO has taken in membersin the past, this largest and latest en-largement, coming just prior to NATO’sfiftieth anniversary, has implications fordefense burden sharing, allocative effi-ciency, and alliance design and stability.An understanding of these implicationscan also enlighten us about scheduled en-largements of the European Union (EU),the World Trade Organization (WTO),and other international organizations. Weinhabit a rapidly changing world wherecollective action, as directed by a grow-ing number of transnational institutions,is becoming more relevant owing to a hostof transnational externalities and publicgoods (Inge Kaul, Isabelle Grunberg, andMarc Stern 1999; Sandler 1997, 1998),

whose increased prevalence arises fromgrowing populations, the fragmentationof nations, enhanced monitoring abilities,and cumulative industrial pressures onthe ecosphere. Transnational externalitiesinvolve an action in one country thatcreates a benefit or cost in another, andthere is no market compensation.

Some 35 years ago, Mancur Olsonand Richard Zeckhauser (1966) wrote aseminal paper on the economics of alli-ances that spawned a large literature.Perhaps, the greatest insights of theirpaper and its forerunner by Olson(1965) is the recognition that economicprinciples of military alliances (hence-forth, alliances) apply to a wide range oftransnational issues and institutions(see, e.g., Bruce Russett and John Sulli-van 1971). Olson and Zeckhauser (1966)focused on burden sharing in an alli-ance, dependent on a pure public goodof deterrence in which the large, richally shoulders the defense burden ofthe small, poor allies by providing thelatter with a relatively free ride. Thisproposition became known as the “ex-ploitation hypothesis.” In 1970, forexample, the United States accountedfor just under 75 percent of NATO’sdefense spending, while the next larg-est allies—Germany, France, and theUnited Kingdom—each assumed lessthan 6 percent of NATO’s defense

869

1 Sandler: Dockson Professor, University ofSouthern California. Hartley: University of York,U.K. We have benefited from comments providedby three anonymous reviewers and John McMillanon earlier drafts. Full responsibility for the arti-cle’s content rests with the authors.

2 On NATO expansion, see Ronald Asmus, Rich-ard Kugler, and F. Stephen Larrabee (1995,1996), David Gompert and Larrabee (1997),NATO (1995), and Sandler and Hartley (1999,ch. 2).

burden. Because the United Statesreceived only 35 percent of NATO’sdefense benefits by one measure, anexploitation appears obvious. Otherfindings stemming from their and sub-sequent work on alliances addressed theoptimal size of such collectives, thesuboptimality of resource allocation,the strategic interactions among mem-bers, the nature of the collective link-age, and the form of the collective’sdemand for the public good. As theOlson-Zeckhauser model’s predictionswent wide of their mark over time forNATO and other alliances, new modelsstressed impurely public good aspectsof the shared defense good.

In recent years, the interest in alli-ances and similar transnational collec-tives has grown in importance. Ratherthan the tranquility and security antici-pated by the end to the Cold War, thesuperpower confrontation has given wayto small, vicious wars driven by territo-rial disputes, internal power struggles,resource claims, and ethnic conflicts. In1999, 27 wars raged throughout the globein 26 locations (Stockholm InternationalPeace Research Institute 1999, p. 9).During the post-Cold War era, defensecollectives have increasingly turned topeacekeeping and peace enforcement inthe world’s trouble spots.3 The creation ofhighly mobile forces, drawn from multi-ple allies, requires a degree of integra-tion and cooperation heretofore neverexperienced in NATO (Palin 1995).Dramatic declines in defense budgets inthe post-Cold War era have augmentedthe importance of allocative efficiency inthe defense sector, as countries must main-tain security with diminished resourcesassigned to defense.

Insights garnered from the study ofalliances can be applied to a broad setof collectives concerned with curbingenvironmental degradation, controllingterrorism, promoting world health,eliminating trade barriers, furtheringscientific research, and assisting foreigndevelopment. This essay on allianceshas much to offer for understanding awide range of international organi-zations such as arms-control regimes,the EU, the United Nations (UN),WTO, and pollution pacts. Althoughmuch of our specific reference will beto NATO, the economic theory of alli-ances has been applied to other currentand historical alliances. Perhaps, themain reason why the public good theoryand its offshoots have been first appliedto alliances and only later to other inter-national organizations is the relativelyeasy identification and measurement ofcosts and benefits afforded by specialistmilitary alliances. Similarly, the readilyavailable data on spending in NATOhave made it the focus of attention incontrast to other alliances where datafor so many years are not available.4

This essay has a number of purposes.First, it provides an up-to-date sum-mary of the findings of the literature onthe economics of alliances. Second, theessay emphasizes how the study of mili-tary alliances offers vital insights for alarge number of transnational collec-tives. Third, the essay establishes thatthe manner in which alliances address

3 NATO’s new strategic doctrine of peacekeep-ing is presented and discussed by Erika Bruce(1995), Robert Jordan (1995), Roger Palin (1995),Steve Rearden (1995), and Sandler and Hartley(1999).

4 By far, NATO is the most studied allianceusing public good theory. Studies include FrancisBeer (1972), Laurna Hansen, James Murdoch, andSandler (1990), Hartley and Sandler (1990, 1999),Gavin Kennedy (1979, 1983), Jyoti Khanna andSandler (1996, 1997), Klaus Knorr (1985), MartinMcGuire (1990), Murdoch and Sandler (1984,1991), Olson and Zeckhauser (1966, 1967), JohnOneal (1990a, 1990b, 1992), Glenn Palmer(1990a,b, 1991), Sandler (1975, 1987), Sandler andJohn Forbes (1980), Sandler and Murdoch (1990),Stephen Sloan (1993), and Jacques van Yperselede Strihou (1967).

870 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

burden sharing and allocative issues isrelated to strategic doctrines, weapontechnology, the perceived threat, andmembership composition. Fourth, theessay indicates bounds to what the eco-nomics of alliances can and cannot do,and why. Fifth, areas needing furtherdevelopment are identified. Through-out this essay, the reader is invited toreplace NATO with the alliance ortransnational institution of his or herchoosing. This replacement will affectthe impurity properties of the sharedactivity with predictable consequencesto the theoretic predictions.

The remainder of this essay containsnine primary sections. Section 2 reviewsthe origins of the economics of alli-ances. In section 3, the pure public,deterrence model of alliances is pre-sented. The more general and encom-passing joint product model of alliancesis then reviewed in section 4. The im-plications of these models on the allies’demand for defense are examined insection 5. Alternative empirical tests ofburden sharing are reviewed in section6, where the applicability of theseempirical methods to the study ofother collective action issues is alsoaddressed. The implication of theeconomics of alliances on peacekeepingactivities is the subject of section 7. Insection 8, other aspects of the study ofalliances are considered including dy-namic concerns, alliance expansion, andalliance trade-offs (e.g., between secu-rity and autonomy). Section 9 highlightsfurther applications to the study of otherinternational collectives. Concludingremarks follow in section 10.

2. The Origins of the Economicsof Alliances

Originally, the economic theory of al-liances rested on the notion that alliesjointly contribute to a defense activity

that is a pure public good with nonrivaland nonexcludable benefits. Defensebenefits are nonrival when one ally’sconsumption of a unit of defense doesnot detract, in the least, from the con-sumption opportunities still available tothe other allies from that same unit. Ifdefense benefits cannot be withheld atan affordable costs by the provider,then these benefits are nonexcludable.The true origins of this theory of alli-ances is Olson’s (1965, p. 36) The Logicof Collective Action where he used alli-ances, and NATO in particular, as anexample of the kinds of internationalorganizations which face allocative effi-ciency problems from sharing a purepublic good. A formal model followedin Olson and Zeckhauser (1966) wheredefense was characterized as deter-rence or inhibiting an enemy’s attackon any ally through the threat of anannihilating retaliation.5

Although these authors clearly recog-nized possible extensions, their modelrested on a number of key assumptions:(i) allies share a single purely public de-fense output, (ii) a unitary actor decidesdefense spending in each ally, (iii) de-fense costs per unit are identical ineach ally, (iv) all decisions are madesimultaneously, and (v) allied defenseefforts are perfectly substitutable. Olsonand Zeckhauser (1966) stressed the dis-proportionate sharing of burdens (i.e.,the exploitation hypothesis) and thesuboptimality of defense provision in amilitary alliance. Their approach cap-tured the interests and imagination ofeconomists, political scientists, and so-ciologists because of their explicit testsof unequal burden sharing of NATO in1964, where the large allies were shownto carry the defense burdens of thesmall. This test also influenced policy

5 On the meaning of deterrence, see ThomasSchelling (1960).

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 871

making and started a burden-sharingdebate among NATO allies that carrieson today (U.S. Department of Defense1999).

In a follow-up study, Olson and Zeck-hauser (1967) started the process ofbreaking their limiting assumptions byallowing for differences in the marginalcost of defense among allies. Once suchdifferences are recognized, allocativeefficiency favors that defense burdensharing be driven partly by comparativeadvantage. A low-cost, small ally may, attimes, assume a greater defense burdenthan a larger ally if the smaller ally’scost advantage is sufficiently great (alsosee Kar-yiu Wong 1991). Efficiencythen requires that marginal costs beequated across allies at their respectivedefense provision levels, and that eachally adjusts for the marginal benefitsthat their provision confers on itself andthe other allies.

3. Alliances: Deterrence and PurePublicness

In Olson and Zeckhauser (1966),defense provision within NATO wascharacterized as providing deterrenceto forestall an enemy attack based on apledged retaliatory response of devas-tating proportions.6 Deterrence, as pro-vided by strategic nuclear weapons(e.g., Trident Submarines, cruise mis-siles), is nonrival among allies insofar asthese weapons’ ability to deter an attackis independent of the number of allies(or citizens) on whose behalf the retali-atory threat is made, so long as thepromised action is automatic and cred-ible to would-be aggressors. There canbe no time inconsistency problemwhere the allies pledging retaliation canreconsider the consequences of their

commitment following an attack on itsally. When an ally possesses a sufficientstockpile of nuclear weapons so that itcan absorb or defend against an enemyassault and still have enough survivingmissiles to unleash a massive retalia-tion (i.e., second-strike capability), thethreatened response is believable.Weapons that can be deployed to hittargets in any aggressor bolster thenonrivalry.

If the provider of strategic nuclearforces cannot fail to deliver a pledgedretaliatory response against an aggres-sor of another ally, then the deterrencebenefits are nonexcludable. Certainly, ifan attack on another ally results in sig-nificant collateral damage to the deter-rence provider in the form of civiliandeaths, lost investments, fallout, orsoldier casualties, then the promisedretaliation is expected and nondiscre-tionary. Actions that ensure collateraldamage serve to tie allies’ interests to-gether and make it difficult, if not im-possible, to exclude other allies from thepromised retribution to any invader oftheir territory. During the Cold War, thelarge number of U.S. troops and theirdependents stationed in West Germany,the United Kingdom, and Italy served as atripwire to the threatened U.S. strategicresponse if Europe were attacked.

3.1 Baseline Pure Public Good Model

In its most elementary representationeach of n allies is assumed to allocateits national income, I, or gross domesticproduct (GDP) between a privatenuméraire good, y, and a pure publicdefense good, q. A decision-makingoligarchy in each ally maximizes itsutility:7

6 On NATO’s alternative military doctrines, seeGompert and Larrabee (1997), Jordan (1995),Rearden (1995), Sandler and Hartley (1999), andJames Thomson (1997).

7 The utility function is a well-behaved strictlyquasi-concave function. If both goods are normalwith positive income elasticity, then the Nashequilibrium exists and is unique (Richard Cornes,Roger Hartley, and Sandler 1999).

872 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

Ui = Ui(yi,qi + Q− i,T), (1)

where Q–i is the sum of the other allies’deterrence spending, so that

Q−i = ∑ j ≠ i

n

q j, (2)

and threat, T, denotes the defense ex-penditures of the enemy. Utility riseswith increases in the private good andthe overall level of deterrence spending,Q = qi + Q–i. At this juncture, thedefense or deterrence contributionsare perfectly substitutable owing to theadditivity of Q.

To complete the model, we representeach ally as facing a linear budgetconstraint:

Ii = yi + pqi, (3)where the price of the private good is 1and that of the defense activity is p. Inkeeping with Olson and Zeckhauser(1966), the price of defense is the samein every ally, so that there is no compara-tive advantage. The Nash equilibriumfollows when each ally chooses its de-fense and private good amounts so as tomaximize utility subject to its budget con-straint and the best-response level of Q–iof the other allies. If all allies contributea positive amount, then the resultingfirst-order conditions can be written as:

MRSQyi = p (4)

for every ally i a member of the alliance.In (4), the MRS expression representsally i’s marginal rate of substitution be-tween defense and the private good and,as such, is a measure of the ally’s mar-ginal willingness to pay for defense or itsassociated marginal benefit. Thus, (4)indicates that each ally equates itsmarginal benefit from defense to the as-sociated marginal cost—in this case, therelative price of defense. Suboptimalityresults at the overall Nash-equilibriumlevel of Q defined by the equation sys-tem in (4), insofar as the marginal bene-

fits that an ally’s defense provisionconfers on the other allies is ignored.8A Pareto-efficient Q level requires thateach ally chooses its defense so that thesum of MRSs is equated to the relativeprice of defense. Thus, the Nash level ofdeterrence is less than the Pareto-efficient level (Olson and Zeckhauser1966; Cornes and Sandler 1996).

Another crucial relationship that fol-lows from the underlying optimizationproblem is the reaction function:

qi = qi(Q−i, p, Ii, T), (5)which relates an ally’s choice of qi to theother allies’ aggregate level of defense andthe remaining three exogeneous variables.The Nash level of alliancewide defensespending also corresponds to the sum of theallies’ defense levels that simultaneouslysatisfies the reaction paths in (5).

3.2 Reaction Paths: GraphicalPresentation

These reaction paths are the allies’demands for defense, which is a func-tion of market datum, the other allies’defense, and external threat. The sec-ond is known as defense spillins andgives rise to free riding as the defenseefforts of the allies replace the need forthe ally’s own defense provision. If allgoods are normal with positive incomeelasticities, then the reaction paths aredownward sloping.

In figure 1, the two-ally case is illus-trated. For the moment ignore thedashed reaction paths. Reaction pathN1N1 is that of ally 1, while N2N2 is thatof ally 2. The intersection of these reac-tion paths at point E is the Nash equi-librium where ally 1 supplies q1N andally 2 provides q2N. The overall level ofdefense at this equilibrium is found bydrawing a line (ET) with slope –1 fromE to the horizontal axis, so that distance

8 That is, Σj ≠ i

MRSQy j is not taken into account.

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 873

0T equals q1N + q2N (Cornes and Sand-ler 1996). The normality assumptionimplies that N1N1 (N2N2) is steeper(flatter) than a downward-sloping linemaking a 45° angle with the axes so thatthe equilibrium is both unique and sta-ble.9 Any given reaction path assumesthat threat, income, and the relativeprice of defense are fixed; changes inany of these things will shift the respec-tive path. If, for example, threat to justally 2 increases, then its reaction pathwill shift up and to the right (see N′2N′2in figure 1) so that ally 2 supplies

a great defense level for each levelof spillins. The new equilibrium at E′implies a higher alliancewide defenselevel (i.e., 0T′ > 0T) with ally 2 assum-ing a greater relative defense burden atE′ as compared with E. In fact, ally 1uses the enhanced threat to ally 2 as ameans to reduce its own defense by freeriding on ally 2’s augmented efforts.This same kind of shift will occur if ally2’s income rises or its relative price ofdefense falls. The shifts are in theopposite direction if threat diminishes,income falls, or p rises. Similarly, thesame kinds of shifts characterize ally 1’sreaction paths. The implications ofthese shifts allow us to sign the co-efficients of a demand curve in anempirical investigation.

Figure 1. Allies’ Reaction Paths in Deterrence Model

q2N

q1N

N2

N1

N1

N2

Ally 2’sdefenseprovision

Ally 1’s defense provision0

N ′2

E ′

T ′TA

E

N ′2

N ′′2

N ′′2

9 These implications are discussed in detail inCornes and Sandler (1996, ch. 6), which also indi-cates the underlying isoutility curves for a purepublic good model from which the reaction pathsare derived.

874 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

The exploitation hypothesis can alsobe illustrated in figure 1 by supposingthat ally 1 has a much greater incomelevel than ally 2. Under these circum-stances, ally 2’s reaction path (N2″N2″ infigure 1) may never intersect that of ally1, so that ally 1 would then supply 0A ofdefense, thus affording ally 2 a com-pletely free ride. Income disparity re-sults in the relative position of the reac-tion paths being such that the large allywill shoulder more, if not all, of theburden of defense. If, for example, thelarge ally spends $250 billion on de-fense and a small ally only desires tospend $50 billion in the absence ofspillins when equating its marginal will-ingness to pay to marginal costs, thenthe small ally is unlikely to spend verymuch. Of course, this exploitation hy-pothesis rests on defense efforts beingperfectly substitutable among allies.

The exploitation hypothesis is depen-dent on a number of implicit assumptionsand does not hold in general (Sandler1992, pp. 54–58). If, however, all allieshave the same tastes, all good are in-come normal, and each ally faces thesame constant unit cost of defense,the exploitation hypothesis follows fromthe standard pure public good model.The hypothesis may fail when a smallally either possesses a greater taste fordefense than its larger counterparts(e.g., Israel allocates a much greatershare of its GDP to defense than theUnited States), or has a comparative ad-vantage in defense over the larger ally.But even with respect to the standardmodel, two key implicit assumptions arecrucial for the exploitation result;namely, that Nash behavior applies andalliancewide defense is the sum of theallies’ contributions. If, for example,leader–follower behavior replaces Nashbehavior and the leader is the large ally,then it is possible to reverse the exploi-tation as the leader exercises its strate-

gic advantage to place a greater burdenon the follower (Neil Bruce 1990; Sand-ler 1992, p. 57). In the case of NATO andmany other alliances, the requirementsfor the exploitation hypothesis apply tothe sharing of deterrent weapons.

3.3 Collective Action Implications

When an alliance shares a purelypublic defense activity, some importantcollective action implications follow.10

First, the exploitation hypothesis indi-cates that defense burdens are antici-pated to be shared in a disproportionatefashion, leading a large, rich ally to allo-cate a greater portion of its GDP todefense than a small, poor ally. Second,defense spending is predicted to be al-located in a suboptimal fashion. Third,cooperation needs to address thissuboptimality either through “tighter”alliance linkages to a central authority(Sandler and Forbes 1980; Sandler andKeith Hartley 1999) or else from anefficient response induced through re-peated interactions. Punishment-basedtit-for-tat strategies are anticipated toproduce more cooperation when re-peated plays among allies are allowed(John McMillan 1986; Sandler 1992, ch.3). Fourth, the absence of rivalry inconsumption for deterrence means thatthere is no efficiency reason to restrictalliance size as only benefits arise (e.g.,cost-sharing savings) from includingfriendly countries. This statementhinges on the absence of transactioncosts and rests on the nonrivalry notionthat extending deterrence to anotherally costs nothing, but would benefitthe entrant. Fifth, the match betweenbenefits received from deterrence andthe actual defense burdens carried isanticipated for many allies to be weakowing to free riding. This shows up, in

10 On collective action, see Russell Hardin(1982), Olson (1965), and Sandler (1992).

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 875

part, as a negative relationship betweenan ally’s real defense outlays and thoseof its allies—i.e., a negative slope to thereaction paths. Sixth, the extent ofsuboptimality may be positively relatedto alliance size, especially if allies are ofsimilar size (Olson 1965).

The perfect substitutability of deter-rence, stemming from the additive Qrelationship, imparts the purely publicalliance model with the structure of aPrisoner’s Dilemma provided that fail-ing to arm does not lead to negativepayoffs. If, however, an attack is emi-nent when adequate deterrent forcesare not maintained, the allies can thenill-afford the dire consequences of noone arming so that a Chicken gameresults with some minimal deterrencebeing provided by a subset of allies—ascenario descriptive of NATO during1950–66. Tit-for-tat strategies foster co-operation for repeated plays of either anunderlying Prisoner’s Dilemma or Chickengame. In an alliance context, a tit-for-tatresponse involves cutting an ally’s owndefense spending when other allies donot spend at “appropriate” levels.

4. A Joint Product Model of Alliances

The forerunner to the joint productmodel was presented by van Yperselede Strihou (1967) who pointed to ally-specific benefits that are private amongallies, but public within an ally.11 Forinstance, defense expenditures used tomaintain control over an ally’s colony,such as Portugal’s one-time interest inAngola, provide purely public benefitsto the ally’s population, but yield littleor no benefits to the other allies. Simi-larly, defense spending on addressing awithin-ally terrorist threat, not in dan-ger of infecting other allies, gives

mostly private benefits to the provider.Once private benefits are acknowl-edged, spending $1 billion more ondefense in ally A may no longer substi-tute for $1 billion of military spendingin ally B. A joint product model goes astep further by permitting the defenseactivity to produce a variety of outputs.

The joint product model was offeredas a generalization to the purely publicdeterrence model by allowing a defenseactivity, q, to give country-specific pri-vate benefits, purely public deterrence,and impurely public damage-limitationor protection for times of conflict(Sandler and Jon Cauley 1975; Sandler1977). Defense outputs are either par-tially or wholly excludable by theprovider, or else partially rival amongthe allies. Consider conventional forceswhich when deployed along an allianceperimeter are subject to a spatial rivalryin the form of force thinning as a givenamount of troops and weapons arespread over a longer exposed border.Coalescing troops in one place alongthe perimeter leads to vulnerabilities atother points, thus implying a rivalry inconsumption. Moreover, the actualdeployment decision can allow theprovider to exclude some allies. Al-though conventional forces also serve todeter a potential aggressor, the mix ofoutputs and their publicness are likelyto differ greatly between conventional andstrategic forces. Unlike conventionalforces, strategic nuclear forces cannotbe used for such country-specific bene-fits as curbing domestic unrest, thwartingterrorism, or providing disaster relief. Con-ventional forces possess a larger share ofally-specific benefits and impurely pub-lic benefits than strategic forces. Essen-tially, the extent of publicness in thepresence of joint products depends onthe ratio of excludable benefits (i.e., ally-specific and damage-limiting benefits)to total benefits.

11 Olson and Zeckhauser (1966, p. 272) clearlyacknowledged these ally-specific benefits, but didnot analyze their implications.

876 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

4.1 Joint Product Model Representation

A joint product representation allowsfor myriad alternative models depend-ing on the number and mix of jointlyproduced outputs. Also, the manner inwhich the defense activity produces thevarious outputs can also influence themodel. For illustrative purposes, weassume just two joint products—acountry-specific output, x, and analliancewide deterrence, z—which areproduced under a fixed-proportiontechnology. Each unit of the defenseactivity in ally i, qi, yields α units of xi

and β units of zi:

xi = αqi, (6)

zi = βqi. (7)

Overall deterrence, Z, is additiveamong allies and, thus, perfectly substi-tutable among allies:

Z = zi + Z−i, (8)

where Z–i is the sum of deterrence com-ing from other allies. By the joint prod-uct relationship, alliancewide deterrencecan be written as:

Z = β(qi + Q−i), (9)

where Q–i denotes the sum of the de-fense activities in allies other than ally i.The decision-making oligarchy’s utilityfunction is now:

Ui = Ui(yi, xi, Z, T), (10)

in which yi is again the privatenuméraire and T is threat. Using equa-tions (6) and (9), we can write thenoncooperative (Nash) maximizationproblem confronting each ally as:

maxyi,qi

{Ui[yi, αqi, β(qi + Q−i), T]

| Ii = yi + pqi}.(11)

In (11), the linear resource constraintequates the ally’s income with its spend-ing on the private good and the defenseactivity.

A Nash equilibrium results wheneach ally simultaneously satisfies itsfirst-order conditions:12

αMRSxyi + βMRSZy

i = p, (12)

where the first MRS is the marginalwillingness to pay for the private ally-specific defense good and the second isthe marginal willingness to pay for deter-rence. In (12), the weighted sum ofthese marginal valuations is equated tothe relative price of the defense activity.This weighted sum is the marginal valu-ation of the defense activity (MRSqy

i ). APareto optimum requires that the firstterm on the left-hand side of (12) beadded to the second term, summed overthe allies; hence, optimality is notachieved unless β is zero. Deterrencebenefits conferred on others are still be-ing ignored. The weights will changewith the fixed-proportion relationships.If, for example, α = 1 and β = 0, thenthe defense activity is purely privateamong allies; if, however, α = 0 and β =1, then we have a purely public deter-rence model. Hence, the joint productmodel is, indeed, a generalization of theOlson-Zeckhauser model.

An important extension, not pursuedanalytically here, is to allow for an im-purely public damage-limiting output sothat three or more outputs are pro-duced in fixed proportions. The first-order conditions will now include thesum of three weighted terms. With thisimpurely public output, thinning offorces becomes germane and an optimalalliance membership must match mar-ginal thinning costs that an entrant im-poses with the savings from sharingcosts over more allies (Murdoch andSandler 1982; Sandler 1977).

12 For a much fuller analysis of joint productmodels, see Cornes and Sandler (1984, 1994). Thelatter two works also present comparative-staticresults, including allowing the fixed-proportioncoefficients to change.

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 877

4.2 Collective Action Implications

The collective action implications ofthe joint product model may be dras-tically different than those of the purelypublic deterrence model of alliances.First, a high ratio of excludable bene-fits—ally-specific and damage-limitingprotection—to total benefits means thatan ally must support its own defense,regardless of its size, if it is going to beprotected. As this ratio nears one, theexploitation hypothesis is anticipated tolose its relevancy, so that the dispropor-tionality between allies’ GDP and theirshare of GDP devoted to defense isexpected to dissipate. Second, as thisbenefit ratio nears one, the operation ofmarkets and clubs achieves a closerequality between the relevant marginalbenefits and marginal costs, so that allo-cations are more efficient. Contribu-tions solicited from Kuwait, SaudiArabia, the United Arab Emirates, andoil-dependent countries (e.g., Japan andGermany) to support the Gulf War of1991 indicate how protection can becharged in a club-like arrangement.13

Third, there is, consequently, less needfor a tighter alliance linkage as the ex-tent of excludable benefits increases,since cooperative gains are reduced.Fourth, alliance size restrictions de-pend on any thinning of forces; allieswith long exposed borders cause morethinning and must contribute a greatershare of the conventional forces tooffset the resulting externality. Insofaras ally-specific benefits are not sharedand deterrence is shared at zero costs,neither of these classes of benefits

affects an alliance size determination.Fifth, joint products should result in agreater match between benefits re-ceived and burdens carried, which sup-ports a benefit principle of taxation.Sixth, the extent of suboptimality isnot related to the alliance size if thereis a large share of excludable benefits.

The presence of joint product alsohas an implication for reaction paths,which now depict the relationship be-tween an ally’s defense activity, qi, andthat of the other allies, Q–i. For normalgoods, the marginal influence of deter-rence spillins on an ally’s own deter-rence efforts was negative, while nowthe reaction of qi to increases in Q–i canbe positive or negative based on theconsumption relationship of the jointlyproduced goods. Suppose that theally-specific defense output and alliance-wide deterrence are complementary inconsumption, so that an increase in oneenhances the desirability or marginalvaluation of the other. The spillin of de-terrence may, thus, induce an ally tospend more on defense so as to securemore ally-specific benefits which canonly come from its own spending(Cornes and Sandler 1984, 1996). Con-sequently, a positive relationship be-tween an ally’s defense provision andthat of the other allies is now possible,thus curbing free riding.

With joint products, the underlyinggame form may be more conducive toaction than that associated with a deter-rence model of alliances. Sandler andKeith Sargent (1995) demonstrated thatjoint products may result in a coordi-nation game where one of the Nashequilibrium has all players contributingto the collective action. If the jointlyproduced private benefits are a suffi-cient share of the total outputs, thencontributing to the defense activity mayeven be a dominant strategy. This has im-plications for alliance formation. That is,

13 See Sandler (1992, pp. 177–80), Khanna, San-dler, and Hirofumi Shimizu (1998, p. 190), andthe U.S. Department of Defense (1992) on the fi-nancing of the Gulf War. In the end, the UnitedStates assumed only $8 billion of the $61 billioncosts, charging the rest to Kuwait, Saudi Arabia,and oil-dependent importers. On clubs, see JamesBuchanan (1965).

878 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

if alliance design allows potential alliesto take advantage of ally-specific benefitsas well as excludable public benefits,then the payoff pattern may be more con-ducive to initial formation. Thus, the mixof joint products and their publicnesscan influence alliance formation.

4.3 Doctrines, Weapon Technology,and Joint Products

By influencing the mix of joint prod-ucts, the strategic doctrine of an alli-ance can have important allocativeimplications. During 1949–66, NATOascribed to a strategic doctrine of mu-tual assured destruction (MAD) deter-rence, for which any Soviet expansioninvolving NATO allies would trigger adevastating nuclear retaliation by theUnited States, France, and Britain. Thealliance depended on strategic deter-rence and, as such, shared mostlypurely public benefits—this explainsthe successful predictions of the Olson-Zeckhauser model for 1964. During1967–90, NATO altered its strategicdoctrine to that of flexible response,where an act of aggression is met with acommensurate response: conventionalor strategic challenges are countered inkind. The measured response would es-calate if necessary (Erika Bruce 1995).As a consequence of this doctrine, thethree kinds of forces—strategic, con-ventional, and tactical—became com-plementary as they needed to be usedin conjunction, thus limiting incentivesto free ride (Murdoch and Sandler1984). Allies failing to deploy sufficientconventional forces became the weaklink that would draw an attack. Thisdoctrine’s reliance on all types offorces meant that defense activitieswithin NATO yielded joint productswith varying degrees of publicness.

From 1991 on, NATO adopted acrisis-management doctrine where thealliance assumed the responsibility for

ensuring Europe’s security and inter-ests from challenges both within andbeyond NATO’s boundaries (Gompertand Larrabee 1997, p. 37). Successfulpeacekeeping and crisis-managementoperations provide an increased mea-sure of world stability and security thatsupplies nonexcludable and nonrivalbenefits worldwide. This new strategicdoctrine also has NATO committed tolimiting the proliferation of weapons ofmass destruction, which also gives rise topurely public benefits. The share of purelypublic outputs associated with NATO’spost-Cold War defense activities hasincreased.

Not only can the strategic doctrineinfluence the mix of joint products, butso can weapon technology. For exam-ple, the perfection of precision-guidedmunitions over the last two decadesmeans that conventional forces do notneed to penetrate a front or to be de-ployed along a front to hit targets withpinpoint accuracy. A cruise missile canbe launched hundreds of miles awayand still destroy enemy assets as dem-onstrated in recent NATO attacksagainst Serbia or U.S. strikes directedat Osama bin Laden’s camps in Afghani-stan. Such weapons reduce thinningand the impurity of conventional forces.An important lesson for alliances and, infact, for any international organizationdependent on joint products, is that po-litical, technological, and other exoge-nous factors can alter the publicness ofthe shared activity.

Even the type of warfare influencesthe mix of joint products. Thinning con-siderations are more pronounced for aguerrilla warfare where large areas aredefended, in contrast to a conventionalwar where fronts are guarded. Also thegeographical location of the allies af-fects the mix of joint products (Sandler1999); if allies are clustered, thenpublicness is enhanced.

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 879

4.4 Aggregation of DefenseContributions

Another dimension of publicness,brought to light in Jack Hirshleifer’s(1983) seminal paper, concerns the re-lationship between individual contribu-tions and the overall level of the publicgood. This relationship is known as theaggregation technology14 and representsyet another factor that influences themix of joint products, burden sharing,and the underlying game form (Sandler1997, 1998). Thus far, we have onlyused the summation technology, whereeach unit of defense adds equivalentlyto the overall level of defense, re-gardless of the contributor. A secondaggregation technology is best shot forwhich the level of the public goodequals the largest provision level amongthe allies. The greatest effort may de-termine the overall level of protectionwhen disarming a rogue nation or elselimiting the proliferation of nuclearweapons. A best-shot technology is rele-vant for a “Star Wars” defense in whichone or more allies possess sufficient de-fensive weapons to destroy an attackingnation’s nuclear missiles shortly afterlaunch. Nuclear deterrence is anotherinstance of best shot. The U.S. nucleararsenal was sufficient owing to itssecond-strike capability to deter a So-viet attack. British and French nuclearforces really did nothing to bolster thisdeterrence during the Cold War. Untiltheir buildup in the 1990s, NATO’sEuropean nuclear strategic forces weremore symbolic than substantive.

In contrast, a weakest-link technologyapplies when the smallest contributionfixes the effective public good level ofthe group. When an alliance is con-fronted with a conventional war, theally deploying the least defense along

its perimeter sets the security standardfor the entire alliance. A fourth aggre-gation technology is weighted sum forwhich weights are applied to allieddefense efforts prior to aggregation,and hence, limits substitutability. Themarriage of these alternative aggregationtechnologies to a joint product modelwas accomplished by John Conybeare,Murdoch, and Sandler (1994) who thendistinguished among alternative tech-nologies for two World War 1 alliances.In particular, they showed that theaggressive Triple Alliance reflected abest-shot technology, while the defensiveTriple Entente abided by a weakest-linktechnology. The geographical positionof these two alliances also determinedthe aggregation technology charac-terizing these alliances. With its centralcluster of allies, the Triple Alliancecould rely on its strongest member,Germany, to attack the weakest link ofthe three geographically separatedmembers of the Entente (i.e., Britain,France, and Russia).

4.5 Joint Products in Other Applications

The joint product model is relevantfor virtually every public good scenario.In the case of the World Health Organi-zation (WHO), Forbes (1980, pp. 121–23) indicated that its activities providedpurely public benefits (e.g., methods ofdisease prevention), impurely publicbenefits (e.g., prophylactic efforts tolimit the spread of diseases), andnation-specific benefits (e.g., medicaltraining). For rain forests, preservationgives global public benefits (e.g., bio-diversity, sequestration of carbon), pri-vate benefits (e.g., timber, fruits), andlocal public goods (e.g., erosion control,nutrient recycling). Additionally, tieddevelopment assistance not only pro-vides a transnational public good byalleviating a recipient’s poverty or im-proving its health, but it also supplies

14 Hirshleifer (1983) used the alternative nameof social composition function.

880 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

donor-specific private concessions(Leonard Dudley 1979; Ravi Kanbur,Sandler, and Kevin Morrison 1999).

5. Demand for Defense

The economic study of alliances hasincluded empirical applications fromits outset. Some of this interest hasbeen directed at estimating the demandfor defense or the reaction path asembodied in equation (5). Empiricalinnovations generated in these de-mand studies were soon applied toother areas—e.g., agricultural researchspending, charitable contributions, andenvironmental pollution.

5.1 Games and Estimations

Unlike a standard private good de-mand function, an ally’s demand for de-fense includes not only relative pricesand income, but also defense spillins ofthe other allies and a threat variable,which the theory treats as exogenous. Ifthe allies’ demands for defense are tobe properly estimated, then the inter-dependency among the error terms ofthe individual ally’s defense demandmust be taken into account. This inter-dependency follows because the under-lying game makes each ally’s choice ofdefense dependent upon that of theother allies.15 Thus, a two-stage estima-tion procedure must be used so that theendogeneity of spillins is taken into ac-count. The recognition of this simulta-neity later carried over to the demandestimates of other public good prob-lems such as charitable contributionsand agricultural research spending(Khanna 1993; Khanna and Sandler 2000;Bruce Kingma 1989). The threat vari-

able can also result in a simultaneity biasif allies’ and adversaries’ demands fordefense equations are being estimated.16

5.2 Distinguishing between Models

Given the two competing theoreticparadigms for the study of alliances, acrucial empirical breakthrough was todevise a procedure for distinguishingwhether a joint product or a pure pub-lic good model best describes the data.Without a clever trick, one could notrely on the reaction or demand func-tion, which when qi is related to Q–i hasthe same form for the two models(Sandler and Murdoch 1990). The trickinvolves the full-income approachwhere pQ–i is added to both sides ofthe relevant budget constraint, thustransforming it to:17

Ii + pQ−i = yi + pQ, (13)where Q is the Nash equilibrium choiceof total alliancewide defense spendingand the left-hand side sum is full in-come, Fi, or income plus the value ofspillins.

With a full-income approach, an ally’sequilibrium reaction path for alliance-wide defense spending is:

Q = Q(Fi, p, T) (14)for the pure public model, whereas it is:

Q = Q(Fi, Q−i, p, T) (15)for the joint product model. Because(14) nests within (15), the two modelscan be distinguished with the help of asimple F-test. In particular, the equationsystems in (15) can be estimated for theset of allies using a two-stage least-squares procedure and then an F-test

15 On this simultaneity bias, see Dudley andClaude Montmarquette (1981), Brian Hilton andAnh Vu (1991), McGuire (1982), Minoru Okamura(1991), and Sandler and Murdoch (1990). Also seethe survey by Ron Smith (1995) on the demand fordefense.

16 On estimates involving threat see, e.g.,Conybeare (1992), Conybeare and Sandler (1990),Rodolfo Gonzales and Stephen Mehay (1991),McGuire (1982), Okamura (1991), and Sandlerand Murdoch (1990).

17 The full-income approach is explained inTheodore Bergstrom, Lawrence Blume, and HalVarian (1986), Cornes and Sandler (1996), andSandler and Hartley (1995).

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 881

can be applied to ascertain the signifi-cance of the Q-i coefficient. If this coeffi-cient is significantly different than zero,as was the case for ten sample NATO al-lies during the 1956–87 period, then thejoint product model is appropriate (Sand-ler and Murdoch 1990). The same testcan be employed for any public goodsituation, national or international, whenjoint products may exist. For example,Khanna, Wallace Huffman, and Sandler(1994) employed this procedure to showthat agricultural research spending inmulti-state crop-growing regions in theUnited States adhered to the joint prod-uct model, while livestock regions (e.g.,the northeast) abided by the pure publicgood model. For livestock regions,research findings are less geoclimatic-specific and more basic, and could betransferred among states more easilythan crops research.

Other evidence for the joint productmodel has followed from demand esti-mates of NATO allies (Gonzalez andMehay 1991; Murdoch and Sandler1984), ANZUS allies (Murdoch andSandler 1985), and historical alliances(Conybeare 1992; Conybeare and Sand-ler 1990; Conybeare, Murdoch, andSandler 1994). By introducing a dummyvariable at the time of flexible response,Murdoch and Sandler (1984) showedthat following MAD the coefficient onspillins increased in value for seven ofnine sample allies, indicative of agreater complementarity among allies’defense spending. Evidence of positivespillin coefficients, consistent with thejoint product model, was corroboratedby Smith (1989) for Britain and Franceduring 1951–87. Thus, there is evidencethat changes in strategy and evenweapon technology can have a profoundinfluence on the demand estimates.During the MAD era, NATO allies’ re-action paths displayed the anticipatednegative coefficient on spillins.

5.3 Other Issues

A host of other empirical issues sur-round the estimation of an ally’s demandfor defense. Two are briefly mentioned.First, the nature of the decision makeris a relevant concern—i.e., is it a oligar-chy or a median voter? The identity of thedecision maker impacts the argumentsin the utility function and the form of theresource constraint—e.g., a governmentbudget constraint or the income constraintof a median voter—and so affects theindependent variables in the defensedemand function.18 Murdoch, Sandler,and Hansen (1991) devised a means fordistinguishing the demand function of agovernment oligarchy from that of amedian voter. Second, McGuire and CarlGroth (1985) raised the issue of theunderlying allocative process. For example,is it a Nash noncooperative process or acooperative Lindahl bargaining pro-cess? If applicable, the latter implies aPareto-optimal outcome in contrast tothe suboptimal Nash equilibrium. Thework of McGuire and Groth (1985) andSandler and Murdoch (1990) led to ameans for discriminating between thesetwo allocative process. For NATO, nineof ten sample allies abided by theNash process for 1956–87, while noneadhered to a Lindahl process.19 Thus,surprisingly, there was no evidence ofcooperation despite the repeated natureof the underlying game.

6. Burden Sharing and Alliances:A Look at the Evidence

To test the exploitation hypothesis,a measure of disproportionality wasrequired, and Olson and Zeckhauser

18 Median-voter models of alliances were pre-sented by Dudley and Montmarquette (1981), Hil-ton and Vu (1991), McGuire (1982), and Murdoch,Sandler, and Hansen (1991).

19 See Sandler and Murdoch (1990). Other stud-ies on the underlying allocative process for NATOinclude Oneal (1990b) and Palmer (1990a,b).

882 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

(1966) defined it in terms of the shareof GDP devoted to defense. By dividingmilitary expenditures (ME) by GDP,they adjusted for the ally’s ability topay, thus giving a within-ally burdenmeasure. According to Olson and Zeck-hauser (1966), those allies that spent agreater share of their GDP on defenseassumed a disproportionately large bur-den. The test was a simple nonparamet-ric Spearman test where GDP ranks forthe allies were computed along withtheir ME/GDP ranks. If a significantpositive correlation between these tworanks resulted, then support for theexploitation hypothesis was uncovered.Olson and Zeckhauser (1966) found thesought-after significant positive correla-tion for 1964 during the MAD era. Cor-roborating evidence was shown byRussett (1970) for NATO annually for1950–67 and for SEATO, CENTO, andthe Warsaw Pact. Frederic Pryor (1968)also presented support for the exploita-tion hypothesis for NATO and theWarsaw Pact during 1956–62, whileHarvey Starr (1974) indicated supportin the case of the Warsaw Pact during1967–71.

NATO burden-sharing behaviorstarted to change around 1967 at theinception of flexible response. EvenRussett’s (1970) Kendall taus (a mea-sure of correlation between defenseburdens and GDP) displayed a markeddecline starting in 1961 though they re-mained significant. Sandler and Forbes(1980) demonstrated that the significantrank correlation between defense bur-dens and GDP held up until 1966 andwas insignificant thereafter except for1973 during the Vietnam War. Similarevidence has been presented by Onealand Mark Elrod (1989) and Khanna andSandler (1996). Thus, the switch from onestrategic doctrine to another had theanticipated impact on burden sharingwith disproportionality ending with flex-

ible response. In a recent study, Sand-ler and Murdoch (2000) showed thatthis correlation has been insignificantduring 1988–99.

For pre-World War 2 alliances de-pendent on conventional armaments,Wallace Thies (1987) presented tablesof burden shares that suggested theabsence of exploitation and support fora joint product models. A subsequentstudy by Conybeare and Sandler (1990)for the Triple Entente and the TripleAlliance also uncovered little evidenceof free riding on the part of the smallerallies.

This same kind of burden-sharing testcan be applied to other transnationalpublic goods and international organi-zations provided that some caution isexercised. When examining interna-tional organizations, the researchermust be careful to ascertain whethersome institutionalized sharing arrange-ment is already in place so that partici-pants cannot really exercise discretion.For example, INTELSAT, an interna-tional organization, is a consortiumwhose member nations share a satellite-based communication network (Sandler1997, pp. 156–58). Its revenues arebased on user fees and, as such, IN-TELSAT is a club arrangement withburdens based on internalizing a crowd-ing externality with nonpayers ex-cluded. If a large country pays more, itdoes so because it utilizes the networkmore often and gains more benefits—there is no presumption of unfairburden sharing.

Another burden-sharing measure, de-vised by Sandler and Forbes (1980), de-notes among-ally burdens by relating anally’s share of NATO’s total spending(MEi/NATO ME) to its derived benefitsfrom being defended. Benefits fromdefense spending arise from what isprotected by the various conventionaland strategic forces: the ally’s industrial

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 883

base, its population, and its exposedborders (i.e., borders not contiguouswith another NATO ally). To calculatean overall proxy measure for these de-fense benefits, these authors computedeach ally’s share of NATO’s GDP, itsshare of NATO’s population, and itsshare of NATO’s exposed borders. Be-cause the ally’s exact preferences arenot known, these three measures aretypically added together and divided bythree for an “average benefit share.”

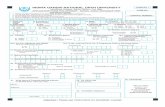

In table 1, defense burdens and aver-age benefit shares for six selected yearsare listed. For example, in 1970, Franceassumed 5.59 percent of NATO’s totaldefense spending, while France re-ceived an average benefit share of 6.30percent, thus implying an under-payment. In contrast, the United Statesassumed 74.25 percent of NATOdefense spending, while it received anaverage benefit share of 34.55 percent,thus indicating a significant overpayment.

TABLE 1DEFENSE BURDENS AND AVERAGE BENEFIT SHARES IN NATO

USING POPULATION, GDP, AND EXPOSED BORDERS AS PROXIES FOR BENEFITS: SELECTED YEARS

1970 1980 1985

CountryDefenseBurden

AverageBenefit Share

DefenseBurden

AverageBenefit Share

DefenseBurden

AverageBenefit Share

Belgium 0.73 1.09 1.55 1.25 0.67 0.91

Denmark 0.35 0.93 0.64 0.99 0.35 0.85

France 5.59 6.30 10.17 7.21 5.79 5.75

Germany 5.85 7.65 10.55 8.56 5.58 6.56

Greece 0.45 2.12 0.89 2.16 0.64 2.04

Italy 2.41 5.99 3.45 6.19 2.12 5.86

Luxembourg 0.01 0.04 0.02 0.05 0.01 0.04

Netherlands 1.06 1.49 2.16 1.85 1.08 1.40

Norway 0.38 2.75 0.66 2.86 0.50 2.76

Portugal 0.42 0.97 0.34 0.98 0.18 0.78

Spain NA NA NA NA 1.10 3.26

Turkey 0.52 3.36 0.96 3.80 0.65 3.78

UK 5.58 6.96 10.48 7.44 6.51 6.30

Canada 1.98 25.82 1.79 25.64 2.01 25.53

US 74.25 34.55 56.36 31.06 72.82 34.19

NATO-Europe 23.77 39.63 41.85 43.30 25.17 40.28

NATO-North America 76.23 60.37 58.15 56.70 74.83 59.72

Source: Figures for 1970, 1980, and 1985 are from Khanna and Sandler (1996, Tables 2–3), while those for the 1990sare from Sandler and Murdoch (2000, Tables 4–5).Notes: Figures represent percentage shares of NATO’s total for each variable. For example, defense burdenindicates the ally’s defense spending divided by total NATO defense spending. Average benefit share denotes thearithmetic mean of each ally’s share of NATO’s population, NATO’s GDP, and NATO’s exposed borders. Germanyrepresents West Germany up to and including 1990, and it denotes unified Germany thereafter. NA denotes notapplicable. Iceland is excluded because it has no defense spending.

884 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

When various Wilcoxon tests are em-ployed to ascertain whether the distri-bution of defense burdens and thedistribution of average benefit sharesfor the NATO allies are the same, therewas no evidence of a difference exceptfor 1985 during the Reagan buildup(Khanna and Sandler 1996). This resultis further support for the joint productmodel where benefits and burdens areanticipated to match. By augmentingpurely public benefits, the Reagan pro-

curement buildup in 1985 lessened theapplicability of the joint product modeltemporarily.

7. Peacekeeping: Burden Sharingand Demands

From 1988 to the mid-1990s, UNpeacekeeping expenditures increasedover a magnitude from under $300 mil-lion to over $3 billion annually (WilliamDurch 1993; Khanna, Sandler, and

TABLE 1 (Cont.)

1990 1995 1998

CountryDefenseBurden

AverageBenefit Share

DefenseBurden

AverageBenefit Share

DefenseBurden

AverageBenefit Share

Belgium 0.92 1.03 0.94 1.06 0.82 0.96

Denmark 0.52 1.30 0.66 1.31 0.63 1.27

France 8.45 6.39 10.12 6.34 9.01 5.90

Germany 8.39 7.58 8.72 9.34 7.33 8.77

Greece 0.77 2.11 1.07 2.12 1.29 2.10

Italy 4.64 5.93 4.10 5.12 5.12 5.06

Luxembourg 0.02 0.04 0.03 0.06 0.03 0.05

Netherlands 1.47 1.54 1.70 1.60 1.50 1.50

Norway 0.67 2.81 0.72 2.81 0.71 2.78

Portugal 0.37 0.98 0.57 0.99 0.53 0.95

Spain 1.80 3.73 1.83 3.50 1.65 3.36

Turkey 1.05 4.12 1.40 4.18 1.84 4.22

UK 7.89 6.69 7.17 6.29 8.17 6.56

Canada 2.29 25.82 1.92 25.50 1.50 25.47

US 60.74 29.93 59.06 29.80 59.85 31.06

NATO-Europe 36.97 44.26 39.12 44.69 38.65 43.47

NATO-North America 63.03 55.74 60.98 55.31 61.35 56.53

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 885

Shimizu 1998; Sandler and Hartley1999, pp. 105–106). In the mid-1990sand thereafter, NATO has taken onlarge peacekeeping missions in Bosniaand Kosovo as the United Nations’ abil-ity to cope with so many missions wasstretched to the limit (Khanna, Sandler,and Shimizu 1999; CongressionalBudget Office 1999).20 NATO’s newcrisis-management doctrine paved theway for it to assume peacekeeping mis-sions whenever its security interestswere in jeopardy. Insofar as successfulpeacekeeping activities provide an in-creased measure of world stability andsecurity that benefits all nations, con-tributors and noncontributors, somebenefits of peacekeeping are nonex-cludable. Other peacekeeping outputsmay be contributor-specific and/or par-tially rival. Thus, peacekeeping activi-ties give rise to joint products whoseoutputs display a variety of publicness.As an example of country-specific out-puts, select nations taking part in theGulf War received lucrative contracts torebuild Kuwait. Moreover, countries incloser proximity to a conflict or withlarger trade interests may gain benefitsfrom peacekeeping, not available toother nations (Davis Bobrow and MarkBoyer 1997). Surely, the influence ofthe United States in the Middle Eastgrew in importance owing to its leader-ship in the Gulf War. A thinning ofpeacekeeping forces results as they aredeployed to trouble spots worldwide.

Methods and insights gleaned from thestudy of alliances can be fruitfully ap-plied to the study of peacekeeping. Inthe case of UN-financed peacekeeping,it became apparent at the time of thefirst sizable operation in the Congo dur-ing 1960–64 that UN resources would

be taxed too heavily if the UN relied onregular membership fees for financingsuch operations. Given the publicnessnature of peacekeeping, early attempts tosolicit voluntary contributions yieldedlittle funding. To create a more perma-nent and reliable funding source, theUN General Assembly passed a resolu-tion that established assessment ac-counts beginning in 1975 for peace-keeping operations.21 Assessments arebased on Security Council membership,national income, and other factors(Mills 1990). Nations could still freeride by failing to honor assessments;many nations exercised some discretionand did not always fulfill their assess-ments (e.g., the United States in the1980s and 1990s).

With the tenfold increases in crisis-management spending in the last de-cade, an exploitation concern existswhere the large, rich nations in boththe UN and NATO shoulder much ofthe burden of peacekeeping. Peace-keeping is anticipated to possess asmaller share of excludable benefitsthan defense spending and, conse-quently, is prone to more dispropor-tionate burden sharing. To investigatethis hypothesis, Khanna, Sandler, andShimizu (1998) examined the Kendallrank correlation between GDP and theshare of GDP devoted to UNpeacekeeping for the UN and NATO.During the 1976–96 sample period,evidence of disproportionality onlysurfaced in the 1990s, coinciding withthe era of increased peacekeepingactivities. These significant rank corre-lations were particularly pronouncedwhen non-UN-financed missions in Ku-wait and Bosnia were included with UNmissions. Non-UN-financed peace en-forcement operations cost the United

20 On UN peacekeeping, its problems, and pros-pects, see Durch (1993), John Heidenrich (1994),Stephen Hill and Shahin Malik (1996), and SusanMills (1990).

21 For institutional details, consult Sandler andHartley (1999, ch. 4) and Durch (1993).

886 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

States well over $3 billion in both 1997and 1998 (Congressional Budget Office1999) and much more in 1999, so thatthis disproportionality is expected togrow further in the coming years as theUnited States, France, Britain, andGermany assume ever greater shares ofpeacekeeping efforts.

Yet another consideration supportingthis prediction of greater disproportion-ality stems from investments in powerprojection or the ability to transporttroops and matériel to conflict areas.Currently, the United States is spendingnearly $20 billion during 1998–2002 toimprove these projection capabilities(Congressional Budget Office 1997).Other investments are being made forrapid deployment forces with light-armored vehicles. Only the three largestNATO allies are investing heavily introop projection and mobility. Ofcourse, there is a strategic advantage tothe smaller allies’ lack of investment be-cause when a contingency later arises,the large allies will necessarily have totransport the small allies’ peacekeepers.At a time of crisis, there is no time toprocure the transport vehicles.

In a follow-up study, Khanna, Sand-ler, and Shimizu (1999) applied themethodology, described in section 5, toestimate a system of UN peacekeepingdemand equations for the primary sup-porters of UN peacekeeping efforts, whileaccounting for the endogeneity of peace-keeping spillins and country–specifictrade gains. This study supported thejoint product representation and iden-tified some complementarity amongdifferent countries’ efforts in providingpeacekeeping.

8. Additional Issues and Questions

To date, the economic theory of alli-ances has been a static affair; there hasbeen no successful marriage of a dy-

namic arms race model with the publicgood theory of alliances. Threat interms of enemy spending is eithertreated as an exogenous variable forwithin–alliance choices,22 or else as asimultaneous–choice variable among al-lies and adversaries (Neil Bruce 1990).In the latter situation, reaction paths ofadversaries and allies are derived, butthe analysis is still static. A first step atincreasing the dynamics of alliancetheory is to devise two- and three-stagegames. For a two-stage game, the firststage can involve the alliance member-ship decision, while the second stagecan concern the level of defense spend-ing.23 If a third-stage is added, it mayinclude an interactive choice betweenopposing alliances, so that a within-alliance sharing decision is then fol-lowed by a noncooperative interallianceinteraction in choosing defense outlays.When opposing alliances are investi-gated, the desirability of allied coopera-tive gains must be reevaluated. By aug-menting defense spending, increasedcooperation within an alliance may be

22 In the international security literature, a moredynamic representation of alliance formation hasbeen proposed (see, e.g., Paul Schroeder 1994;Randall Schweller 1994). Nations are viewed asjoining an alliance to either balance a threat or tobandwagon. Bandwagoning, often for territorialgain, can heighten the threat to an opposing alli-ance, so that the entry decision endogenizesthreat. By treating threat as exogenous, most eco-nomic theories of alliances are unable to addresssuch dynamic choices. Cultural, political, and so-cial considerations also influence which countriesare likely to ally. Robert Axelrod and D. ScottBennett (1993) developed a theory of allianceformation based on shared values which facilitatecooperation.

23 In the political science literature, Morrow(1994) presented the alliance formation decisionas an extensive-form game with incomplete infor-mation about the costs of war. A trade-off is madebetween short-run peacetime costs from allyingand possible long-run costs from war resultingfrom not allying. Robert Powell (1993) examinedinteralliance decisions concerning whether or notto attack. There is again a short-run versus long-run trade-off implied by decisions to arm and/orattack.

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 887

met in kind by the enemy alliance, sothat more is spent but security is notenhanced. Neil Bruce (1990) has shownthat this can then result in welfarelosses in a small alliance, implying thatthe concern over suboptimal provisionwithin an alliance ignores interallianceinteractions. This recognition that co-operation may have negative conse-quences in the presence of strategicresponses of agents outside the grouphas now characterized recent analyses ofother transnational public goods—e.g.,pollution control (Wolfgang Buchholz,Christian Haslbeck, and Sandler 1998).Toshihiro Ihori (2000) has shown thatthe “Bruce effect” is less likely to holdwhen the number of cooperating alliesincreases in number—Neil Bruce (1990)had only assumed two cooperating allies.

Another means for augmenting thedynamics of alliance theory is to beginwith an arms race model and introducealliance elements of defense publicness.This, too, is a formidable task becausepublic goods and joint products are dif-ficult to analyze in a dynamic multi-agent framework. If true dynamics areto characterize the study of alliances,then this is probably the preferablemethod to pursue.

A second important issue involvesmultiple public goods within alliancesand the potential trading opportunitiesthat they offer allies (Boyer 1989,1990). Such multiple public goods gobeyond joint products and include nu-merous activities, each of which can giveoff joint products. A good example ofthis is James Morrow’s (1991) autonomy-security trade-off as the large allies pro-vide the security for the small allies inreturn for their support on politicalissues. In a recent paper, Palmer and J.Sky David (1999) devised an empiricaltest to distinguish Morrow’s diversity-of-goals model from a pure public de-terrence model by examining non-

nuclear and nuclear alliances, with thelatter abiding by the deterrence model.

A different issue involves the designof alliances based on a transaction costsand transaction benefits approach (OliverWilliamson 1975). Such transaction-costs design analyses depart from thestandard noncooperative model thatunderlies our study thus far. Designissues rely on a cooperative gametheory where all participants mustrealize a net cooperative gain over thenoncooperative status-quo equilibrium.When the ratio of excludable benefits issmall, cooperative gains from improvedefficiency can arise as allies formtighter linkages and sacrifice autonomy.Cooperation can take the form of in-creased defense spending, equipmentstandardization, common logistics, sharedintelligence, coordinated troop deploy-ment, common infrastructure, and collabo-rative weapons projects (Hartley 1991).With NATO’s new crisis-managementdoctrine, this cooperation can also in-volve the development of an alliance-wide rapid deployment force. Such co-operation provides transactions benefitsin terms of efficiency gains, economiesof scale, and enhanced information andcommunication, while they also createtransactions costs in the form of deci-sion making, loss of autonomy, enforce-ment efforts, and monitoring. In de-signing an optimal alliance, transactionsbenefits and costs must be identifiedand traded off against one another(Sandler and Cauley 1977; Sandler andForbes 1980).24 Because alliances are

24 David Lake (1999, pp. 35–37) presented sucha theory where the form of an alliance varied fromno alliance to a tightly knit hierarchy. The allianceform was determined by maximizing net transac-tion benefits that accounted for benefits of econo-mies of scale and costs of hierarchical control.This exercise is analogous to a much earlier one bySandler and Cauley (1977). Also see the net trans-action benefits approach to international organi-zations by Kenneth Abbott and Duncan Snidal(1998).

888 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

now involved with numerous activities,transaction interactions among such ac-tivities must also be accounted for whendeciding alliance structure. A looser,less integrated structure is appropriateif the ratio of excludable benefits nearsone as market transactions and clubarrangements can operate relativelyefficiently. As strategic doctrine, tech-nologies, and missions change withtime, the proper form of alliances willneed alterations—loosening some linksand tightening others.

Alterations in the composition ofthe allies can also require structuralchanges to an alliance. For example,decision-making rules may need to beless inclusive when there are more al-lies (or members in an international or-ganization) with greater taste diversity.Without a relaxation of an inclusivevoting rule, decisions may never bereached which might destroy the viabil-ity and effectiveness of NATO as a mili-tary alliance. Of course, club member-ship principles can be applied todetermine the optimal membership sizebased on thinning and transaction con-siderations. In a multiproduct frame-work where congestion can affect alli-ance activities differently, membershipdetermination is more difficult. None-theless, the possibility of diminishingbenefits and rising costs of extendedmembership suggests a limit to the sizeof the alliance; thus, the need for acomprehensive analysis of the marginalbenefits and costs of NATO enlargementfor existing and new members.

An optimal alliance might also becharacterized by specialization based oncomparative advantage with the principleapplied to both armed forces and de-fense industries. For example, the UnitedStates might provide high-technologyforces (e.g., nuclear deterrence, precision-guided weapons); Germany might sup-ply armored forces; and the United

Kingdom might contribute anti-submarineand special forces. The alliance wouldalso need to identify and collectivelyfund those new weapons and forcesthat give rise to pure public goods (e.g.,ballistic missile defenses). Weaponsshould be bought and sold in a NATOfree-trade area.

9. Applications to Other InternationalCollective Action Scenarios

9.1 Background

Olson (1965, pp. 35–36) focused onvarious interest groups (e.g., unions),most of which were national rather thaninternational organizations, althoughreference was made to the UN andNATO as examples of suboptimality inlarge groups and the exploitationhypothesis. But Olson’s (1982, p. 13)methodology towards theory and itstesting always warned against acceptinga theory based on one set of facts. In-stead, a reader should ask, “What canthis theory explain that it is not tailor-made to explain?” (Avinash Dixit 1999,p. F449). Olson insisted that “a list ofinstances supporting a hypothesis, nomatter how lengthy, did not clinch thematter; one had to search diligentlyfor counterarguments and counterexam-ples” (Dixit 1999, p. F444). This sectionadopts the more limited aim of consid-ering whether the logic of internationalcollective action can be extended tointernational organizations other thanmilitary alliances.

There are numerous examples of in-ternational organizations, ranging fromglobal government organizations suchas the UN; to international nongovern-mental organizations (NGOs) such asOxfam, Consumers International; inter-national sports organizations (e.g.,olympics, tennis); and food organi-zations such as Hungry International.Table 2 presents a four-way taxonomy

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 889

based on the number of nations in aninternational organization and the typeof product provided. Small numbersinvolve two or three nations. Organi-zations providing multiple public goodsor distinct activities are distinguishedfrom those that supply a single publicgood. If, however, a single activityyields joint products, the parent organi-zation is still characterized as a single-product organization owing to itssingle-purpose orientation. Thus, theUN and the EU are viewed as supplyingmultiple public goods, in contrast to theWTO, whose main purpose is to facili-tate free trade, or the Universal PostalUnion, which oversees the free flow ofinternational mail.

9.2 Transnational Pure Public Goods

There has been a growing awarenessand interest in the study of transna-tional public goods (e.g., actions to con-trol malaria, to limit some pests, or toclean a transboundary river). At theglobal level, preservation of the strato-sphere ozone layer and curbing globalwarming represent two pure publicgoods, which will be undersuppliedwith much of the burden falling on thericher nations. In an empirical study,Murdoch and Sandler (1997) showedthat a country’s income and politicalfreedoms were the two primary deter-minants of cutbacks in ozone-depleting

chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) emissions.Once the ozone hole over Antarctica wasdiscovered and its genesis understood,action by the primary CFC-producingand CFC-consuming countries wasswift, culminating in the Montreal Pro-tocol and its even stricter amendments(Richard Benedick 1991; Scott Barrett1999). The large, rich countries notonly shouldered the burdens, but alsooffered inducements to small, poorcountries in the form of technical sup-port and a ten-year reprieve from cut-backs. Thus, an exploitation of the largeby the small is evident. The treatyserved more of a long-term escape fromany Prisoner’s Dilemma pressures byinstituting a tit-for-tat punishment ondeflectors in terms of trade boycotts.

To date, the progress on global warm-ing has not been a success story sincemany of the rich countries have beenunwilling to shoulder the disproportion-ate burdens that small countries wantplaced on the rich. For CFCs emis-sions, the small countries emitted smallquantities of the pollutants and werenot projected in the near term to in-crease these emission levels. This is notthe case for global warming where evenpoor countries can create greenhousegases (GHGs) through their agricultureor destruction of their forests. The eco-nomic losses associated with reducingGHG emissions are much greater than

TABLE 2A TAXONOMY OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

Small number of nations Large number of nations

Single product (specific)

US-Russian Space Stations; US-USSR INFTreaty 1987; Anglo-French Concorde airliner; Eurofighter; US-Cuba Anti- Hijacking Treaty

WTO; European Space Agency;Environmental Treaties; InternationalTelecommunication Union (ITU); Universal Postal Union

Multiproduct (general)

Anglo-Irish Agreement 1999; CulturalExchange Programs

NATO; United Nations; EU; Antarctic TreatySystems; International Maritime Organization

890 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXIX (September 2001)

those tied to limiting CFCs emissions.Thus, carrying a disproportionate bur-den for reducing GHGs is a much moreexpensive proposition for the rich. Evenefforts to sequester carbon in tree plan-tations raise burden-sharing difficulties,not unlike those faced by defense alli-ances—each nation would prefer thatthe others finance these plantations.NATO’s unintegrated structure servesas a good role model for getting aglobal-warming agreement off theground, which can be subsequentlytightened if warranted as we learn moreabout the consequences of a warmer at-mosphere. If the world community ini-tially holds out for too integrated atreaty, none may be ratified. A practi-cal, imperfect treaty may be better thannone at all.

9.3 Transnational Joint Products

By far the overwhelming number oftransnational public goods are activitiesthat yield outputs of varying degrees ofpublicness and, as such, can benefitfrom the joint product analysis of alli-ances. Take the case of sulfur emissionswhich remain airborne for up to sevendays before falling as acid rain or drydepositions.25 Sulfur cleanup possessesa strong country-specific share of bene-fits insofar as the majority of sulfuremissions in Europe land within theemitting country’s own borders (HildeSandnes 1993). Thus, it is not surpris-ing that European countries ratified theHelsinki Protocol mandating a 30 per-cent cutback in sulfur emissions from1980 levels. For nitrogen oxides wherea much smaller share of the emissionsbecomes self-pollution, an agreementwas much slower and mandated smallercutbacks than the sulfur treaty. As formilitary alliances, a high ratio of ex-

cludable benefits induced emission-reducing actions and allowed fortreaties without stated punishments,unlike the Montreal Protocol for whichthis ratio was near to zero and punish-ments explicit. Consider the UnitedKingdom which did not sign the sulfuror nitrogen oxides protocols. A rela-tively small share of these pollutantsfrom Britain land on its own soil, and,hence, it lagged other European coun-tries in controlling emissions. Becauseits progress in reducing emissions wasfar behind treaty-mandated cutbacks,Britain opted not to ratify the treaties.Other European countries, whose self-pollution was much greater or whichsuffered large pollution spillins, wereeither already close to satisfying man-dated reductions when the treaties wereframed or else had much to gain frompollution constraints on others.

The UN is an example of an interna-tional organization that illustrates theimportance of group size: small groupsare more likely to solve the collectiveaction problem compared with groupsof many nations. As a large group, theUN is prone to fail to supply an optimalamount of public goods and to be char-acterized by free riding with largermembers bearing disproportionateshares of the organization’s burden.Such features are reflected in the habit-ual complaints that the UN allocates toofew resources (e.g., for peacekeeping,economic development, and famine anddisaster relief), that too many nations freeride (e.g., consuming peace as a publicgood), and that the large member statesare exploited (e.g., U.S. leadership inUN-sponsored military actions). Thejoint product model of alliances, how-ever, cautions that these conclusionsmust be attenuated if large shares ofnation-specific benefits are derivedfrom a member’s UN support. In theabsence of these member-specific

25 On acid rain and sulfur emissions, see Sandler(1997, pp. 115–29) and Murdoch, Sandler, andSargent (1997).

Sandler and Hartley: Economics of Alliances 891

benefits, the large nations can re-taliate against such exploitation bywithholding funds for other UN activi-ties or by using the veto in the UNSecurity Council (i.e., a tit-for-tat strat-egy). This raises interesting questionsabout the constitution and voting ar-rangements in large-number internationalorganizations and their implications foroptimal outcomes.

Further instances of joint productsinclude supplying foreign medical assis-tance, alleviating poverty abroad, creat-ing scientific discoveries, preservingtropical forests, and neutralizing arogue nation. In all of these examples,an activity not only provides contributor-specific benefits but also groupwidepure and impure public benefits. When,for example, a country supplies foreignmedical assistance, it gets contributor-specific benefits from both the experi-ence that its medical personnel acquireand the goodwill that its efforts earn.By helping to improve the recipientcountry’s health, people worldwide areat a reduced risk because diseases areless apt to gain or maintain a footholdthere and be transmitted abroad. Medi-cal assistance given in one country limitsassistance that can be given elsewhere,so a rivalry is also present.