WHAT IS A HERO?. What is a hero? BRAINSTORM HERO ATTRIBUTES.

Joseph Campbell‛s definition of a hero: “Someone who has ...Stages+of+the... · 12 Stages of...

-

Upload

trinhkhuong -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of Joseph Campbell‛s definition of a hero: “Someone who has ...Stages+of+the... · 12 Stages of...

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

1

May16,2011

Joseph Campbells definition of a hero: Someone who has

given his or her life to something bigger than

him/herself

Joseph Campbells definition of an archetypal hero (one who goes on a Heros Journey):

any male or female who leaves the world of his or her everyday life to undergo a journey to a special world where challenges and fears are overcome in

order to secure a reward which is then shared with other members of the heros community

What characters can you think of from movies/books who have left their world?

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

2

May16,2011

So who is Joseph Campbell?

Joseph Campbell was born and raised in White Plains in an upper middle class Roman Catholic home. As a child Campbell became fascinated with Native American culture after his father took him to see the American Museum of Natural History in New York where he saw on display featured collections of Native American artifacts. He soon became versed in numerous aspects of Native American society, primarily in Native American mythology. This led to Campbell's lifelong passion for myth and to his study of and mapping of the cohesive threads in mythology that appeared to exist among even disparate human cultures.

Campbell's thinking on universal symbols and stories was deeply influenced by James Frazer, Adolf Bastian, and Otto Rank(The Myth of the Birth of the Hero), among others. Anthropologist Leo Frobenius was important to Campbells view of cultural history.

Campbell's ideas regarding myth and its relation to the human psyche are dependent in part on the pioneering work of Sigmund Freud, but in particular on the work of Carl Jung, whose studies of human psychology, as previously mentioned, greatly influenced Campbell. Campbell's conception of myth is closely related to the Jungian method of dream interpretation, which is heavily reliant on symbolic interpretation.

Jung's insights into archetypes were in turn heavily influenced by the Bardo Thodol (also known as The Tibetan Book of the Dead). In his book The Mythic Image, Campbell quotes Jung's statement about the Bardo Thodol, that it "belongs to that class of writings which not only are of interest to specialists in Mahayana Buddhism, but also, because of their deep humanity and still deeper insight into the secrets of the human psyche, make an especial appeal to the layman seeking to broaden his knowledge of life... For years, ever since it was first published, the Bardo Thodol has been my constant companion, and to it I owe not only many stimulating ideas and discoveries, but also many fundamental insights."

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

3

May16,2011

In 1940 Campbell attended a lecture by Professor Heinrich Zimmer at Columbia University the two men became friends, and Campbell looked upon Zimmer as a mentor. Zimmer taught Campbell that myth (rather than a guru or spiritual guide) could serve in the role of a personal mentor, in that its stories provide a psychological road map for the finding of oneself in the labyrinth of the complex modern world. Zimmer relied more on the meanings of mythological tales (their symbols, metaphors, imagery, etc.) as a source for psychological realization than upon psychoanalysis itself. Campbell later borrowed from Jung's interpretative techniques and then reshaped them in a fashion that followed Zimmer's beliefsinterpreting directly from world mythology. This is an important distinction, because it serves to explain why Campbell did not directly follow Jung's footsteps in applied psychology.

Monomyth Campbell's term monomyth, also referred to as the hero's journey, refers to a basic pattern found in many narratives from around the world. This widely distributed pattern was first fully described in The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) An enthusiast of novelist James Joyce, Campbell borrowed the term from Joyce's Finnegans Wake . As a strong believer in the unity of human consciousness and its poetic expression through mythology, through the monomyth concept, Campbell expressed the idea that the whole of the human race could be seen as reciting a single story of great spiritual importance and in the preface to The Hero with a Thousand Faces he indicated it was his goal to demonstrate similarities between Eastern and Western religions. As time evolves, this story gets broken down into local forms, taking on different guises (masks) depending on the necessities and social structure of the culture that interprets it.

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

4

May16,2011

Monomyth (continued) Its ultimate meaning relates to humanity's search for the same basic, unknown force from which everything came, within which everything currently exists, and into which everything will return and is considered to be unknowable because it existed before words and knowledge. The Story's form, however, has a known structure, which can be classified into the various stages of a hero's adventure like the Call to Adventure, Receiving Supernatural Aid, Meeting with the Goddess/Atonement with the Father, and Return. As the ultimate truth cannot be expressed in plain words, spiritual rituals and stories refer to it through the use of "metaphors, a term Campbell used heavily and insisted on its proper meaning: In contrast with comparisons which use the word like, metaphors pretend to a literal interpretation of what they are referring to, as in the sentence 'Jesus is the Son of God' rather than 'the relationship of man to God is like that of a son to a father'."

Monomyth According to Campbell, the Genesis myth from the Bible ought not be taken as a literal description of historical events happening in our current understanding of time and space, but as a metaphor for the rise of man's cognitive consciousness as it evolved from a prior animal state.

Campbell made heavy use of Carl Jung's theories on the structure of the human psyche and he used terms like Anima/Animus and Ego Consciousness often. That is not to say that he necessarily agreed with Jung upon every issue, for he had very definite ideas of his own. He did believe however, as he clearly stated in the Power of Myth, in a specific structure that exists in the Psyche and is somehow reflected into myths.

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

5

May16,2011

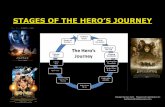

Twelve Stages of the Journey

1. Heroes are introduced in the ORDINARY WORLD, where 2. they receive the CALL TO ADVENTURE. 3. They are RELUCTANT at first or REFUSE THE CALL, but 4. are encouraged by a MENTOR to 5. CROSS THE THRESHOLD (the first of three times) and enter the

Special World, where 6. they encounter TESTS, ALLIES, AND ENEMIES. 7. They APPROACH THE INMOST CAVE, crossing a second threshold 8. where they endure the SUPREME ORDEAL. 9. They take possession of their BOON or REWARD and 10. are pursued on THE ROAD BACK to the Ordinary World. 11. They cross the third threshold, experience a RESURRECTION or

ATONEMENT, and are transformed by the experience. 12. They RETURN WITH THE ELIXIR, a boon or treasure to benefit

the community in the Ordinary World.

The Hero is introduced in the Ordinary World

The Hero's Journey begins in the Ordinary World. (Eventually the Hero travels to a Special World and returns to the Ordinary World as part of the Journey.) We are introduced to the Hero and given details of the setting in the Ordinary World, as well as information about the Hero's beliefs/desires/priorities/etc.

In terms of plot structure, this is part of the Introduction/Exposition. It is when we, as readers/receivers of the story, begin to care about the Hero and become involved in his/her Journey.

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

6

May16,2011

Call to Adventure

The call to adventure is the point in the Hero's life when s/he is first given notice that everything is going to change, whether s/he knows it or not. In terms of plot structure, the Call to Adventure is the exposition of the conflict.

Destiny has summoned the hero. S/he may go forward to accomplish the adventure of his/her own free will. S/he may be carried or sent by someone else. It might begin accidentally, or s/he could be walking down a familiar path and follow a distraction. An accident, a blunder, something planned or something hoped for. . .

The Call to Adventure sets the story rolling by disrupting the comfort of the Hero's Ordinary World, presenting a challenge, a problem, or an adventure that must be undertaken.

Reluctance or Refusal of the Call

Often when the Call to Adventure is given, the future Hero refuses to heed it. This may be from a sense of duty or obligation, fear, insecurity, a sense of inadequacy, or any of a range of reasons that work to hold the Hero in his or her current circumstances.

A Hero often refuses [or is reluctant] to take on the Journey because of fears and insecurities that have surfaced from the Call to Adventure. The Hero may not be willing to make changes, preferring the safe haven of the Ordinary World. This becomes an essential stage that communicates the risks involved in the Journey that lies ahead. Without risks and danger or the likelihood of failure, the receivers of the story will not be compelled to be a part of the Hero's Journey.

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

7

May16,2011

Meeting the Mentor

The relationship between the Mentor and the Hero represents that of a parent/child or student/teacher. The Mentor can only go so far with the Hero. Eventually the Hero must make the decision to face the unknown. Sometimes the wise old Mentor is required to give the Hero a swift kick in the pants to get the adventure going. This is Obi Wan Kenobi giving Luke Skywalker his father's light sabre.

The Hero meets a Mentor to gain confidence, insight, advice, training, or magical gifts (aka "supernatural aid") to overcome the initial fears and face the Threshold of the adventure. The Mentor may be a physical person, or an object such as a map, a logbook, or other writing.

Crossing the First Threshold

Crossing the Threshold signifies that the Hero has finally committed to the Journey. S/he is prepared to cross the gateway that separates the Ordinary World from the Special World.

This is the moment at which the story takes off and the adventure gets going. The balloon goes up, the romance begins, the plane or spaceship blasts off, the wagon train gets rolling. Dorothy sets out on the Yellow Brick Road.

The Hero is now committed to the Journey... and there's no turning back.

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

8

May16,2011

Tests, Allies, and Enemies

Having crossed the First Threshold, the Hero faces Tests, encounters Allies, and confronts Enemies. Allies are earned, a Sidekick may join up, or an entire Hero Team may be forged. The Hero finds out who can be trusted and

prepares for the greater Ordeals yet to come. S/he needs this stage to test his/her skills and powers, or perhaps seek further training from the Mentor. In terms of plot structure, this is the rising action of the story.

If there are tests, they often come in threes, and the Hero may fail one or more of them. The Hero may meet a goddess or a temptress. Or it may not be a temptress at all it could be something else representing temptation. An example is in "The Natural" when Roy Dobbs is shot by the woman in black with a silver bullet. He then enters the Belly of the Whale, a point when it seems the Hero has lost hope and maybe will not succeed on this Journey.

Approach the Inmost Cave

The Hero must make the preparations needed to approach the Inmost Cave that leads to the Journey's heart, or central Ordeal. Maps may be reviewed, attacks planned, and possibly the enemies' forces whittled down before the Hero can face his greatest fear, or the supreme danger. The Approach may be a time for some romance or a few jokes before the battle, or it may signal a ticking clock or a heightening of the stakes. The Inmost Cave is the setting of the climax of the story--physically, psychologically, or often both.

The Hero has arrived at a dangerous place, often deep underground, where the object of the quest is hidden. In many myths the Hero has to descend into hell to retrieve a loved one, or into a cave to fight a dragon and gain a treasure. Sometimes it's the Hero entering the headquarters of the Enemy and sometimes it's just the Hero going into his or her own dream world to confront his or her worst fears . . . and overcome them.

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

9

May16,2011

The Hero endures the Supreme Ordeal

The Hero engages in the Ordeal, the central life-or-death crisis, during which s/he faces his/her greatest fear, confronts his most difficult challenge, and even may experience "death". This is a critical moment in any story, an ordeal in which the Hero appears to die and is born again the Journey teeters on the brink of failure. This is the climax of the story--the height of the action.

It's a major source of the magic of the hero myth. The audience has been led to identify with the Hero. We are standing outside the cave waiting for the victor to emerge it's a black moment. This is the magic of any well-designed amusement park thrill ride.

Reward (Seizing the Sword, The Ultimate Boon)

The Hero has survived death, overcome his greatest fear, slain the dragon, or weathered the crisis of the heart, and now earns the Reward that he went on the Journey to get. All the previous steps serve to prepare the Hero for this step.

The Hero's Reward comes in many forms: a magical sword, an elixir that can heal, the Holy Grail, greater knowledge or insight, reconciliation with a lover. The Hero may have earned the Reward outright, or the Hero may have seen no option but to steal it.

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

10

May16,2011

The Road BackThe Hero must finally recommit to completing the Journey and accept the Road Back to the Ordinary World. A Hero's success in the Special World may make it difficult to return. Like Crossing the Threshold, The Road Back needs an event that will push the Hero through the Threshold, back into the Ordinary World. The Hero's not out of the woods yet. Some of the best chase scenes come at this point, as the Hero may be pursued by vengeful forces. The Road Back may be a moment when the Hero must choose between the Journey of a Higher Cause versus a personal Journey of the Heart.

The magic flight scenario--sometimes the Hero must escape with the Boon, if it is something that the gods have been jealously guarding. It can be just as adventurous and dangerous returning from the Journey as it was to undertake it.

The Resurrection/Atonement

The Hero is transformed from the lessons and insights gained from the characters along the road. The Resurrection may be a physical change, or final showdown between the Hero and the Shadow. This battle is for much more than the Hero's life. Other lives, or an entire world, may be at stake and the Hero must now prove that s/he has achieved heroic status. Other Allies may come to the last-minute rescue to lend assistance, but in the end the Hero must rise to the sacrifice at hand.

Joseph Campbell calls this Atonement (at-one-ment)--the Hero is made whole or complete as a result of the journey, and s/he will use the lessons learned to contribute to the greater good in some way.

The trick in returning to the Ordinary World is to retain the wisdom gained on the quest, to integrate that wisdom into the Hero's life, and then figure out how to share the wisdom with the rest of the world. This is usually extremely difficult.

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

11

May16,2011

Return with the Elixir

The Hero comes back to the Ordinary World, but the journey would be meaningless unless s/he brought back the Elixir, treasure, or some lesson. Sometimes the Boon is treasure won on the quest, or love, or just the knowledge that the Special World exists and can be survived. Sometimes it's just coming home with a good story to tell. Sometimes it's just knowledge or experience, but unless the Hero comes back with the Elixir or some Boon, s/he's doomed to repeat the adventure until s/he does.

Many comedies use this ending, as a foolish character refuses to learn the lesson and embarks on the same folly that got him/her in trouble in the first place.

Even if the ending is tragic it can still provide the best lessons of all, specifically creating a greater awareness of the world for the receivers of the story.

A Short Recap of the Hero's Journey

The hero is introduced in the ordinary world, where s/he receives the call to adventure. S/he is reluctant at first but is encouraged by a mentor to cross the first threshold into the special world. Here the hero encounters tests to gain knowledge and skills, and s/he learns who can/cannot be trusted (allies and enemies). The hero reaches the innermost cave, where s/he endures the supreme ordeal. After overcoming the ordeal the hero "seizes the sword" (the reward) and is pursued on the road back to the ordinary world. S/he is transformed by the experience (resurrection/atonement), and returns to the ordinary world with the "elixir"--a boon--to benefit the community.

SMART Notebook

-

12StagesoftheHero'sJourney.notebook

12

May16,2011

Comments about the Hero's Journey

Following the guidelines of the monomyth too rigidly can lead to a stiff, unnatural structure in the story, and there is danger of being too obvious.

The monomyth, or Hero's Journey, is a skeleton that should be masked with the details of the individual story, and the structure should not call attention to itself.

The order of the hero's stages as given here is only one of many possibilities. The stages can be deleted, added to, and drastically reshuffled without losing their power. It grows and matures as new experiments are tried within its basic framework.

The values of the myth are what's important. The images of the basic version -- young heroes seeking magic swords from old wizards, fighting evil dragons in deep caves, etc., -- are just symbols, and can be changed infinitely to suit the story at hand. The myth is infinitely flexible, capable of endless variation without sacrificing any of its magic.

Page 1Page 2Page 3Page 4Page 5Page 6Page 7Page 8Page 9Page 10Page 11Page 12