Joost de Bloois - Our Work is Never Over Art and Activism

Transcript of Joost de Bloois - Our Work is Never Over Art and Activism

2

23 enter

the sleep laboratory: art, labor,

politics joost

de bloois

45 entra en

el laboratorio del sueño:

arte, trabajo, política joost

de bloois

71 the good of work

liam gillick

93 el propósito del trabajo liam gillick

3 INTRODUCTION: WheN exIsTeNCe beCOmes WORk 13 INTRODUCCIÓN: CUaNDO la exIsTeNCIa se CONvIeRTe eN TRabajO

our work is never over nuestro trabajo nunca se acaba

7 june – 26 august 2012

matadero madrid, contemporary art center. in the framework of Photoespaña 2012.

3

INTRODUCTION: WheN exIsTeNCe beCOmes WORk

The artist is lying down in bed, under a blanket, sometimes with his eyes open, sometimes closed; sometimes he turns his back to the camera. We don’t know if he’s sleeping, dozing or maybe just contemplating. The only thing the work reveals to us is that the artist is in a relaxed, easy position. Yet, the title of the work clearly states artist at Work.

artist at Work, a series of self-documented black and white photos by Mladen Stilinović, questions the seeming separation between life, art and labor. Stilinović performs a personal every day practice as a piece of work, a creative process and a work of art in itself, intertwining the boundaries of these three fields. As an action and an antiaction at the same time, the work initially aimed to challenge the symbolic power of labor under the communist regime. however, the advent of the pre-carious post-Fordist society in the last 20 years with its heavy reliance on flexible, creative and immaterial labor transforms the issues raised by Stilinović into ones that are except ionally urgent. This urgency is the point of departure for the exhibition Our Work is Never Over, which features works from artists who are constantly exploring where art, labor and everyday exis-tence overlap in contemporary society. This group of artists reflects on the immateriality of the artistic process, the role of labor in designating social life and the complexity of repre-sen ting invisible work.

The current relationship between labor and its represen -ta tions is a prominent theme in critical thought and artistic practice today. as many thinkers have shown, the invisi bility of a work is actually a sophisticated disciplinary power, one that “puts into work the entire life of the workers” and makes the distinction between free time and work

4

time obsolete.1 late capitalism uses the work’s immateri ality as an instrument for capital accumulation, while enslaving life itself, i.e. our thoughts and ideas, in any time and at any place, to the productive process. This process is accel-erated by the fragmentation and pulveri za tion of work, which leads to the financial instability and precariousness of life in general. Flexibility, mobility, adapt ability and, no less important, creativity, become the desirable attributes of any imma terial worker. In other words, life itself, i.e. our very own bodies and brains, is now subject to the borderless and rampant capitalist regime.

This bio-political nature of any immaterial production suggests new and complex modes of representation, where the artistic form of self-documentation plays a vital role. “art documentation,” writes boris Groys, “marks the attempt to use artistic media within art spaces to refer to life itself, that is, to a pure activity, to pure practice, to an artistic life, as it were, without presenting it directly.”2 The artists par ticipating in the exhibition choose to reflect on the totality of their bio-political existence from within and through life itself: some documented their everyday life and used the documentation as an artistic work; others framed their artistic acts as identical to any other form of labor; and a few made the gray area between artistic process and immaterial labor part of their own life. as part of Photoespaña, Our Work is Never Over strives to contextualize self-documentation as an inter section where the worlds of life, art and labor collide and dissolve into one another.

1 andré Gorz, Reclaiming Work: beyond the Wage-based society (Cambridge: Polity, 1999), p.50.

2 boris Groys, art Power (Cambridge: mIT Press, 2008), p.54.

5

Stilinović’s artist at Work reveals the latent link between a daily routine, such as lying in bed, and the complex social function labor has in today’s society. Through the act of self-documentation, he reflects on his position as a subject within a set of social norms, while trying to resist them. Guy ben-Ner’s work Drop the monkey follows the same path. Documenting himself as an artist-worker who manipulates his new project’s financial support for his own personal benefits, ben-Ner acknowledges his obligations as a worker in the field of art, while trying to protect his personal sense of agency. likewise, artist ahmet Ögüt depicts his status as an artist by manipulating both the art world and an existing artwork. send him Your money is Ögüt’s own version of Chris burden’s work send me Your money, where he asks the listeners to send money to him instead of burden. by re-enacting burden’s work, Ögüt re-addresses the position of the artist as a precarious worker who has to find creative solutions to make a living.

joana bastos uses the same playful approach to position herself within the “structural uncertainty”3 that is endemic to the precarious state of things. In Next money Income? she documents herself as a worker with different previous day jobs, and, accordingly, she creates a sincere statement on the current condition of livelihood and the inability to actually make a living from one’s art. Complementing this work, her performance and catalog intervention, Gray and shameless,

3 joost de bloois, making ends meet: Precarity, art and Political activism, lecture on the occasion of the exhibition Informality — a new collectivity, 13 – 8 – 2011: http://project1975.smba.nl/en/article/ lecture-joost-de-bloois-making-ends-meet-precarity- art-and-political-activism-august-13-2011.

6

merge her position as an artist participating in the exhibition and earning a fee for it with her position as a precarious worker who illegally trades goods around the exhibition space and then disappears to her other job.

marc Roig blesa and Rogier Delfos, meanwhile, make a dif-ferent attempt to reflect on working conditions while examining the possibility of encouraging collective practices of self- representation. In their Werker 4: an economical Portrait of the Young artist and Werker 6: Cinema Diary, which was created especially for this exhibition, the two collect and contextualize images taken by artists and cultural practitioners, where they questioned their contingent mode of being.

mounira al- solh’s video as if I Don’t Fit There expands the discussion on precariousness in today’s global so ciety by exhibiting documentation of female figures, who are not only former artists, but immigrants as well. These women share with the viewers their decision to quit making art and find ‘real’ jobs, but their solutions to the situation are fictional, as are the women themselves, all of whom are played by the artist. mapping the field of precarious im material labor while providing a physical space for reflection and research, the C.a.s.I.T.a artist collective creates a library comprising a selection of books as well as a set of external references and links. The library is part of the installation The Foundry of the Transparent entity, which is part of the collective’s ongoing project earning a living, where they seek to stimulate an exchange of ideas related to the notions of post-Fordist life and labor.

The attempt to reflect on one’s personal position through the act of self-documentation is closely connected to the questions of what it takes to define immaterial artistic pro cess as such and how we can discern between artistic labor and nonartistic labor. David Levine deals with these questions

mou

nira

al s

olh

Com

o si

no

enca

jara

aq

uí (

20

06

), v

ideo

. v

ive

y tr

abaj

a en

Ám

ster

dam

.

Cua

tro

muj

eres

se

desc

ubre

n an

te la

cám

ara.

el e

scen

ario

es

dife

rent

e pa

ra c

ada

una,

aun

que

a to

das

las

cara

c ter

iza

la m

ism

a co

mbi

naci

ón d

e fr

ivol

idad

y s

erie

dad.

Lo

que

real

-m

ente

vem

os e

s la

doc

umen

taci

ón d

e la

prá

ctic

a ar

tíst

ica

de c

ada

muj

er.

De

alg

una

man

era,

las

im

ágen

es p

arec

en

piez

as d

e ar

te d

e ca

da u

na d

e el

las

que

ya e

xist

en.

Junt

o

a la

s im

ágen

es h

ay t

exto

. e

l te

xto

nos

expl

ica

la h

isto

ria

pers

onal

de

cada

muj

er.

Poc

o a

poco

nos

vam

os e

nter

ando

de

que

tod

as e

sas

muj

eres

son

art

ista

s in

mig

rant

es q

ue

deja

ron

de s

erlo

y b

usca

ron

trab

ajos

nue

vos.

la

arti

sta,

qu

e in

terp

retó

a c

ada

una

de la

s m

ujer

es y

cre

ó su

his

tori

a pe

rson

al d

e fic

ción

, de

stac

a el

hec

ho d

e qu

e ni

ngun

a de

el

las

se s

ient

e in

cóm

oda

por

su d

ecis

ión

de n

o cr

ear

más

ar

te.

¿se

está

n ha

cien

do il

usio

nes?

C

omo

si n

o en

caja

ra a

quí,

la ins

tala

ción

de

vide

o de

M

ouni

ra A

l Sol

h, e

s un

a cr

ític

a di

vert

ida

cent

rada

en

las

duda

s co

nsta

ntes

que

ella

tie

ne s

obre

su

deci

sión

de

tra-

baja

r co

mo

arti

sta.

Com

o m

ucha

s ot

ras

obra

s de

al s

olh,

la

iron

ía y

el h

umor

des

empe

ñan

una

func

ión

impo

rtan

te e

n su

inve

stig

ació

n au

torr

eflex

iva,

com

o ta

mbi

én s

u m

ezcl

a ún

ica

de fi

cció

n y

lo p

erso

nal,

de d

ram

a y

paro

dia.

En

esta

pi

eza,

la a

rtis

ta c

ombi

na s

u in

teré

s po

r la

man

era

de p

en-

sar

de lo

s in

mig

rant

es y

su

frec

uent

e ap

ropi

ació

n de

otr

as

obra

s ar

tíst

icas

. E

ste

enfo

que

desd

e va

rias

per

spec

tiva

s

Image: stills from

as If I D

on’t Fit T

here (20

06

). Courtesy of the

artist and sfeir-s

emler G

allery, b

eirut — h

amburg.

le p

erm

ite

expl

orar

de

man

era

ínti

ma

los

giro

s in

finit

os q

ue

se d

an t

anto

en

el t

raba

jo a

rtís

tico

com

o en

el t

raba

jo n

o ar

tíst

ico,

así

com

o en

el e

stat

us s

ocia

l de

cada

prá

ctic

a.

Imag

en:

foto

gram

a de

Com

o si

no

enca

jara

aqu

í (2

00

6).

Cor

tesí

a de

l ar

tist

a y

de la

Gal

ería

Sfe

irS

emle

r,

bei

rut

— h

ambu

rgo.

mounira a

l solh

as If I D

on’t Fit There (2

00

6), video.

lives and works in a

msterdam

and beirut.

Four w

omen reveal them

selves to the camera. F

or every w

oman, the setting

is different, although the sam

e com

bination of frivolity and seriousness characterizes all of them

. What w

e actually see is a documentation of

each wom

an’s artistic practice. som

ehow, the im

ages look like artw

orks that already exist. alongside the im

ages is text. T

he text tells us about each wom

an’s personal story. s

lowly, w

e learn that all these wom

en are imm

igrant artists w

ho decided to stop being artists and find new jobs.

The artist, w

ho played each of the wom

en and made up

their fictional life story, underlines the fact that none of them

are bothered by their decision to no longer create art. Is it w

ishful thinking? m

ounira al s

olh’s video installation, as If I D

on’t Fit T

here, is a playful criticism of the constant doubts she

has about her decision to work as an artist. a

s in other w

orks by al s

olh, irony and humor play an im

portant role in her selfreflective investigation, as w

ell as her unique m

ixture of fictional and personal, drama and parody.

In this piece, the artist combines her interest in the im

mi-

grant mindset w

ith her frequent appropriation of other artw

orks. This m

ulti-layered approach allows her to inti-

mately explore the endless shifts from

artistic labor to non-artistic labor and the social status of each practice.

12 11

when he asks professional actors to sign an actor’s union contract that defines their daily job as perfor mance. Consequently, the actors ‘do’ their job and ‘perform’ it at the same time. Pillvi Takala explores this performative as pect of labor and, like Stilinović, the poten tial for resistance that resides within it, in her installation The Trainee. Takala spent one month working at a consul tancy firm where she did practi-cally nothing the whole time. The mutable reactions from her colleagues reveal how immaterial workers have to perform their work in order for it to be considered as ‘work’, which forces us to re-think what actually counts as work today. The notion of non-performance as an act of non-compliance, which is essential for Takala and Stilinović, also appears in levi Orta’s Dias libres. In this piece, the artist per forms the passive action of drinking a Cuba libre cocktail on every day of anti-government demonstrations around the world. Orta implies that under the current social, economic and poli tical struc tures a non-action such as drinking a Cuba libre (with its multiple semantic meanings) can be an act of opposition.

Tehching hsieh adopts a much more industrious approach to the increasing diffusion of life, art and labor. In his canonical work One Year Performance 1980 – 1981 (Time Clock Piece), he physically embodies the gray area between these fields by punching a time clock, every hour, on the hour, for a year, while documenting himself every time. by doing so, hsieh transforms the artistic act into both a daily routine and a rigid labor activity, while meshing any immaterial crea tive process with the Fordist logic of production. As in Stilinović’s artist at Work, the Time Clock Piece suggests a radical intervention in life itself, and the close docu mentation of this intervention acts as a means to question the validity of what are considered the disassociated spheres of our existence.

12

Named after a song by the futuristic French electro duo Daft Punk, Our Work is Never Over aspires to unfold the multi-faceted axes of life, labor and art at this specific historical point in time, where the bio-political nature of work, followed by the reorganization of life, preempts every aspect of our existence. self-documentation, as a bio-political artistic form, can reflect, challenge and even subvert the dominant social, political and economic ideo logy when embodied in artistic practice.

— Yael messer and Gilad Reich

13

INTRODUCCIÓN: CUaNDO la exIsTeNCIa se CONvIeRTe eN TRabajO

el artista está tumbado en la cama, debajo de una manta, a veces con los ojos abiertos, a veces cerrados; a veces le da la espalda a la cámara. No sabemos si está durmiendo, si se está quedando dormido o si simplemente está contemplando. Lo único que la obra nos revela es que el artista está en una posición relajada y cómoda. Aunque, el título de la obra dice claramente artist at Work (artista trabajando).

artist at Work, una serie de fotos en blanco y negro que Mladen Stilinović se tomó a sí mismo, se pregunta por la aparente separación entre la vida, el arte y el trabajo. Stilinović realiza una práctica personal diaria como obra de arte, un proceso creativo y una obra de arte en sí misma, entrelazando las fronteras de estos tres campos. Como acción y antiacción a la vez, la obra inicialmente pretendía cuestionar el poder simbólico del trabajo en el régimen comunista. sin embargo, la llegada de la precaria sociedad postfordista en los últimos 20 años y su dependencia del trabajo flexible, creativo e inmaterial, transforma los problemas planteados por Stilinović en unos problemas excepcionalmente urgentes. esta urgencia es el punto de partida para la exposición Nuestro trabajo nunca se acaba, que presenta obras de artistas que constan-temente están explorando el lugar en el que el arte, el trabajo y la existencia de cada día se solapan en la sociedad contem-poránea. Este grupo de artistas refleja la inmaterialidad del proceso artístico, la función del trabajo al señalar la vida social y la complejidad de la representación del trabajo invisible.

la relación actual entre el trabajo y sus representaciones es un tema importante en el pensamiento crítico y la práctica artística de hoy. Como han mostrado muchos pensadores, la invisibilidad de un trabajo tiene realmente una capacidad

14

disciplinaria sofisticada, ya que “pone a trabajar toda la vida de los trabajadores” y hace que la distinción entre el tiempo libre y el tiempo de trabajo sea obsoleta.1 el capitalismo contem-poráneo utiliza la inmaterialidad del trabajo como un instru-mento para la acumulación de capital a la vez que esclaviza la misma vida, p. ej., nuestros pensamientos e ideas en cual-quier momento y en cualquier lugar, al proceso productivo. este proceso está acelerado por la fragmentación y la pulveri-zación del trabajo, que lleva a la inestabilidad económica y la precariedad de la vida en general. La flexibilidad, la movilidad, la adaptabilidad y, no menos importante, la creatividad, se convierten en los atributos deseables de todo trabajador inmaterial. en otras palabras, la vida misma, p. ej., nuestros propios cuerpos y mentes, está sujeta al régimen capitalista desenfrenado y sin límites.

Esta naturaleza biopolítica de toda producción inmaterial sugiere modos nuevos y complejos de representación, en la que la forma artística de autodocumentación desempeña una función vital. la “documentación del arte”, escribe boris Groys, “marca el intento de utilizar los medios artísticos en los espacios de arte para referirse a la vida en sí misma, es decir, a una actividad pura, a la práctica pura, a una vida artística, como si lo fuera, pero sin presentarla directamente”.2 Los artistas que participan en la exposición deciden reflexionar en la totalidad de su existencia biopolítica desde dentro y a través de la vida misma: algunos han documentado su vida cotidiana y han utilizado la documentación como una obra de arte; otros han captado sus actos artísticos de forma idéntica a cualquier otra forma de trabajo; y unos pocos han convertido

1 andré Gorz, Reclaiming Work: beyond the Wage-based society (Cambridge: Polity, 1999), p.50.

2 boris Groys, art Power (Cambridge: mIT Press, 2008), p.54.

15

en parte de su propia vida la zona gris entre el proceso artís-tico y el trabajo inmaterial. Como parte de Photoespaña, Nuestro trabajo nunca se acaba se esfuerza en contextualizar la autodocumentación como una intersección en la que los mundos de la vida, el arte y el trabajo colisionan y se disuelven en los demás.

artist at Work, de Stilinović, revela el vínculo latente entre una rutina diaria, como la de estar tumbado en la cama, y la función social compleja que el trabajo tiene en la sociedad de hoy. A través del acto de la autodocumentación, reflexiona sobre su posición como individuo sujeto a unas normas sociales, pero que intenta resistirse a ellas. Drop the monkey de Guy BenNer sigue la misma ruta. Documentándose a sí mismo como un artistatrabajador que manipula el apoyo financiero de su nuevo proyecto para su propio beneficio personal, ben-Ner reconoce sus obligaciones como trabajador en el campo del arte, mientras intenta proteger su sentido personal de negocio. De igual modo, el artista ahmet Ögüt representa su estatus manipulando tanto el mundo del arte como las obras que ya existen. send him Your money es la versión de Ögüt de la obra send me Your money de Chris Burden, en la que pide a los oyentes que le envíen dinero a él, en vez de a Burden. al reconstruir la obra de burden, Ögüt vuelve a tratar la posición del artista como trabajador precario que tiene que encontrar soluciones creativas para poder vivir.

Joana Bastos utiliza el mismo enfoque divertido para posicionarse a sí misma dentro de la “incertidumbre estructural”3

3 joost de bloois, making ends meet: Precarity, art and Political activism, conferencia durante la exposición Informality — a new collectivity, 13 – 8 – 2011: http://project1975.smba.nl/en/article/ lecture-joost-de-bloois-making-ends-meet-precarity- art-and-political-activism-august-13-2011.

16

que es endémica del estado precario de las cosas. En Next money Income? se documenta a sí misma como trabajadora con distintos trabajos anteriores de día y, en virtud de eso, crea una afirmación sincera sobre la condición actual de la vida y la incapacidad de vivir realmente a partir de arte propio. Complementando esta obra, su performance e intervención del catálogo, Gray and shameless, fusiona su posición como artista que participa en la exposición y que cobra un dinero por ello, con su posición como trabajadora precaria que comercializa de forma ilegal productos en el espacio de la exposición, y luego desaparece para ir a su otro trabajo.

mientras tanto, marc Roig blesa y Rogier Delfos realizan un intento diferente para reflexionar sobre las condiciones de trabajo mientras examinan la posibilidad de animar prácticas colectivas de autorrepresentación. en Werker 4: an economical Portrait of the Young artist y Werker 6: Cinema Diary, que se ha creado especialmente para esta exposición, recopilan y contex-tualizan imágenes tomadas por artistas y profesionales culturales en las que se cuestionan la posibilidad de su existencia.

el video de mounira al- solh, as if I Don’t Fit There, amplía el debate sobre la precariedad en la sociedad global de hoy mostrando documentación de figuras femeninas, que no solo son antiguas artistas, sino que también son inmigrantes. estas mujeres comparten con los espectadores su decisión de dejar de hacer arte y encontrar trabajos ‘de verdad’, pero sus soluciones a la situación son ficticias, como también lo son las mismas mujeres, a las que representa la artista. Con el objetivo de mapear el campo del trabajo inmaterial precario a la vez que se ofrece un espacio físico para la reflexión y la investigación, el colectivo de artistas C.A.S.I.T.A. crea una biblioteca con una selección de libros y una colección de referencias externas y enlaces. la biblioteca es parte de la instalación The Foundry of the Transparent entity, que es parte

joan

a b

asto

s ¿C

uánd

o te

ndré

el s

igui

ente

ingr

eso?

(2

00

7),

impr

esió

n cr

omog

énic

a.

Gri

s o

sinv

ergü

enza

(2

012

),

perf

orm

ance

e in

terv

enci

ón e

n el

cat

álog

o.

viv

e y

trab

aja

en l

isbo

a.

El p

rim

er a

utor

retr

ato

foto

grá

fico

a ta

mañ

o re

al r

epre

sent

a a

la a

rtis

ta c

omo

mie

mbr

o de

l equ

ipo

de a

tenc

ión

al p

úblic

o de

la N

atio

nal G

alle

ry.

el s

egun

do a

utor

retr

ato

la r

epre

sent

a co

mo

empl

eada

de

una

inm

obili

aria

y la

ter

cera

la r

epre

-se

nta

com

o un

a ni

ñera

ale

gre

y a

lgo

pija

. s

in e

mba

rgo,

el

cua

rto

auto

rret

rato

es

una

imag

en e

n bl

anco

. Im

puls

a

al e

spec

tado

r a

imag

inar

cóm

o se

rá la

art

ista

en

su p

róxi

mo

trab

ajo,

aun

que

toda

vía

se d

esco

noce

.e

n su

obr

a ¿C

uánd

o te

ndré

el s

igui

ente

ingr

eso?

,

joan

a b

asto

s ex

plor

a la

s re

laci

ones

labo

rale

s de

l cap

ital

ism

o m

ás c

onte

mpo

ráne

o ut

iliza

ndo

su p

ropi

a si

tuac

ión

pers

onal

re

spec

to a

l em

pleo

com

o m

ater

ia d

e su

s ob

ras

en p

arti

cula

r.

Al re

pres

enta

r lo

s tr

abaj

os r

eale

s qu

e ha

ten

ido

en e

l

pasa

do,

nos

pres

enta

una

col

ecci

ón d

e es

trat

egia

s de

sup

er-

vive

ncia

en

pote

ncia

den

tro

del m

undo

de

la e

mpr

esa

y el

m

undo

de

los

trab

ajad

ores

fle

xibl

es.

el m

arco

des

nudo

sin

au

torr

etra

to e

xpre

sa la

ans

ieda

d qu

e cr

ea la

bús

qued

a si

n fi

n de

la

sig

uien

te p

aga.

la

piez

a su

bray

a la

tem

pora

lidad

in

here

nte

en t

oda

exis

tenc

ia p

reca

ria,

a la

vez

que

nos

en

fren

ta a

la p

regun

ta s

obre

cóm

o vi

sual

izar

a lo

s tr

abaj

a-do

res

inm

ater

iale

s, c

omo

los

arti

stas

.

new and second-hand. T

he performance, G

rey or sham

eless, created especially for this exhibition, w

ill establish a nar rative w

ith Next m

oney Income?, and w

ill transform the

exhibition space as well as the catalog

into a working

area w

here bastos w

ill actually create a gray market, i.e. she

will be m

aking money from

the direct illegal trade of goods, w

hile earning her artists’ fee for participating

in the exhibition. b

oth works express the artist’s ong

oing search

to earn money at a tim

e when livelihood is precarious and

income unstable.

Image: N

ext money Incom

e? (20

07).

Courtesy of the artist.

Com

o pa

rte

de la

exp

osic

ión,

bas

tos

tam

bién

est

ará

de v

ez

en c

uand

o ej

ecut

ando

una

per

form

ance

, ve

ndie

ndo

pro-

duct

os y

efe

ctos

per

sona

les,

nue

vos

y de

seg

unda

man

o.

la p

erfo

rman

ce, G

ris o

sin

verg

üenz

a, c

read

a es

pecí

ficam

ente

pa

ra e

sta

expo

sici

ón,

esta

blec

erá

una

narr

ativ

a co

n ¿C

uánd

o te

ndré

el s

igui

ente

ingr

eso?

y t

rans

form

ará

el e

spac

io

expo

siti

vo a

sí c

omo

el c

atál

ogo

en u

na z

ona

de t

raba

jo

en la

que

Bas

tos

crea

rá u

n m

erca

do g

ris

real

, p.

ej.

,

esta

rá h

acie

ndo

dine

ro c

on e

l co

mer

cio

ileg

al d

irec

to d

e pr

oduc

tos,

a la

vez

que

gana

su

tari

fa c

omo

arti

sta

por

part

icip

ar e

n la

exp

osic

ión.

las

dos

obr

as e

xpre

san

la

búsq

ueda

act

ual d

e la

art

ista

de

gana

r di

nero

en

un m

omen

to

en e

l que

la v

ida

es p

reca

ria

y lo

s in

gres

os,

ines

tabl

es.

Imag

en:

¿Cuá

ndo

tend

ré e

l sig

uien

te

ingr

eso?

(2

00

7).

Cor

tesí

a de

la a

rtis

ta.

joana bastos

Next m

oney Income? (2

00

7), chrom

ogenic prints. G

rey or sham

eless (20

12),

performance and catalog intervention.

lives and works in lisbon.

The first lifesize photographic selfportrait depicts the art-

ist as a mem

ber of the National G

allery’s front of house team

. The second self-portrait depicts her as an em

ployee at a real estate agent, and the third one depicts her as a cheerful, yet som

ewhat m

undane, nanny. The fourth self-

portrait, however, is a blank im

age. It prompts the view

er to im

agine w

hat the artist will look like in her next, as yet

unknown, job.

In her work, N

ext money Incom

e?, joana bastos explores

late-capitalist labor relations using her own personal em

-ploym

ent situation as a subject for her works in particular.

by depicting the real jobs she held in the past, w

e are presented w

ith a gallery of potential survival strateg

ies w

ithin the corporate world and the w

orld of flexible workers.

The bare fram

e with no self-portrait expresses the anxiety

created by the everlasting search for the next pay packet.

The piece underlines the tem

porality inherent in any pre ca-rious existence, w

hile also confronting us with the question

of how to visualize im

material w

orkers such as artists. a

s part of the exhibition, bastos w

ill also occasionally be perform

ing, selling goods and belongings, both brand

21

del proyecto actual del colectivo earning a living, mediante el que buscan estimular un intercambio de ideas relacionadas con las nociones de la vida y el trabajo postfordista.

el intento de reflexionar sobre la posición personal de uno a través del acto de la autodocumentación está conectado estrechamente con las preguntas sobre qué es necesario para definir el proceso artístico inmaterial como tal y cómo podemos discernir entre trabajo artístico y trabajo no artístico. David levine trata estas cuestiones cuando pide a actores profesionales que firmen un contrato del sindicato de actores que define su trabajo diario como performance. Como consecuencia, los actores ‘realizan’ su trabajo y hacen su ‘perfor-mance’ al mismo tiempo. Pillvi Takala explora este aspecto performativo del trabajo y, como Stilinović, el potencial para la resistencia que reside en él en su instalación The Trainee. Takala pasó un mes trabajando en una consultoría en la que no hacía nada en todo el tiempo. Las reacciones mutables de sus compañeros muestran cómo los trabajadores inmateriales tienen que realizar su trabajo para que este se considere ‘trabajo’, lo cual nos obliga a volver a pensar qué es lo que realmente se entiende por trabajo en la actualidad. la noción de inacción como un acto de incumplimiento, que es esencial para Takala y Stilinović, también aparece en Días Libres de levi Orta. en esta pieza, el artista realiza la acción pasiva de beber un cóctel Cuba libre por cada día en el que se celebran manifestaciones antigubernamentales en el mundo. Orta da a entender que con las estructuras sociales, económicas y políticas actuales una inacción como beber un Cuba libre (con sus diversos significados) puede ser un acto de oposición.

Tehching Hsieh adopta un enfoque mucho más laborioso en la difusión cada vez mayor de la vida, el arte y el trabajo. en su obra canónica One Year Performance 1980 - 1981 (Time Clock Piece), encarna físicamente la zona gris entre estos

22

campos fichando en un reloj de control, cada hora, a la hora en punto, durante un año, mientras se documentaba a sí mismo cada vez. Al hacer esto, Hsieh transforma el acto artístico en una rutina diaria y una actividad laboral rígida, mientras que entreteje cualquier proceso creativo inmaterial con la lógica de la producción fordista. Igual que en artist at Work, de Stilinović, Time Clock Piece sugiere una intervención radical en la vida misma, y la exhaustiva documentación de esta intervención actúa como medio para cuestionar la validez de lo que se consideran las esferas desasociadas de nuestra existencia.

Llamada así por una canción del dúo francés de electro futurista Daft Punk, Our Work is Never Over aspira a descubrir los ejes polifacéticos de la vida, el trabajo y el arte en este momento específico de la historia, en el que la naturaleza biopolítica del trabajo, seguida por la reorganización de la vida, se adelanta a cualquier aspecto de nuestra existencia. La autodocumentación, como forma artística biopolítica, puede reflexionar, cuestionar y hasta subvertir la ideología social, política y económica dominante cuando se personifica en la práctica artística.

— Yael messer y Gilad Reich

23

enter the sleep

laboratory: art, labor,

politics

joost de bloois

24

Why cannot art exist any more in the West? The answer is simple. artists in the West are not lazy. — Mladen Stilinović

INsIDe The sleeP labORaTORY

Mladen Stilinović’s artist at Work (1978) evokes surprisingly dissonant associations: it vaguely reminds of eadweard muybridge’s photographic studies of human and animal movement. In Stilinović’s series of photographs, we see the artist, at first, eyes open, ruminating perhaps, his arms behind his head; then apparently sound asleep, turning over on his side and back, fully immersed in the choreography of sleep. artist at Work presents a peculiar study of Oblomovian non-movement; or perhaps: of inner movement, satirizing the romantic-Freudian cliché of the artist as a laborer of the unconscious. In Stilinović’s work, the artist’s studio acts as a sleep laboratory: we are let in to witness artistic work as dream work, but only if we whisper. Despite its obstinate refusal to be ideologically outspoken (all we hear is a light snort), artist at Work is an emphatically political piece. Stilinović’s work firstly gains its obvious political significance in the historical context of communist Yugoslavia. It performs the reversal of the communist celebration of work that, politically, only allows sleepwalkers. The modern cliché of the libertarian artist who drops out of bourgeois subjectivity by staying in bed, in Stilinović, becomes frightfully claustrophobic: the bedroom

25

truly is the artist’s studio, since anywhere outside of it, he will be coerced into participating in a different type of subjectivity (and come to think of it: who is observing our ‘artist at work’ in Stilinović’s piece?). artist at Work is an outspoken political work precisely because it takes an anti-productivist stance: it rejects the marxist ontology of the Gattungswesen [‘species -being’] — of man as a being that produces, and does so collectively. Stilinović’s artist asleep demonstrates that there is another type of ‘work’, another way of conceiving life as work: a form-of-life that is irreducible to the shared productivist ontology of both the heroic laborer of historic communism and the truism of life-as-work-of-art. The political meaning, or perhaps rather: the strategy of Mladen Stilinović’s artist at Work strongly resembles that of Italian autonomism, which reached its peak during the same final years of the 1970s that were witness to Stilinović’s performances of radical inertia. For the autonomia movement, staying in bed was an effective form of refusal of the world of labor — of the very social rela tions that constitute the bread and butter of capitalist oppression — and a means of gaining autonomy. autonomia embraced bartleby’s ‘I would prefer not to’ as a political creed, and the ‘human strike’ as its preferred stratagem. It is this gesture of refusal of ‘work’, including artistic output, which provides artist at Work with its political importance today. Mladen Stilinović’s lethargic selfportrait is highly significant for our post-1989 and decidedly post-Fordist context. In the era of frictionless, but no less ferocious, financial capital, the era of the abstraction of each of our abilities as ‘cognitive’ or ‘immaterial labor’ and the era of the real subsumption of every aspect of our lives under the capitalist rule of value, Stilinović’s silent revolt for a form-of-life that refutes the productivist ontology might prove to be decisive. Therefore, artist at Work may serve here as a preamble to a reflection on the significance

26

of ‘political art’ today; that is to say of a ‘political art’ that would drastically question its complicity with political consensus and the ontologies that support it. a ‘political art’ once more, but a political art as a form-of-life.

The TIlT shIFT eFFeCT IN POlITICal aRT

We can hardly overlook the revival of ‘political art’ since the turn of the century. Not that politics was absent from art in the 1980s or 1990s, but we now see a political art that writes Politics and art with capital letters: it seems as if mediators such as ‘sexuality’ or ‘identity’ (that gave rise to the ‘sexual politics’ or ‘identity politics’ of the previous decades) in the nexus between art and politics have vanished. Politics and art now directly operate on one another, appear to mutually define one another and both now coalesce directly into ‘political art’ (obviously, this tendency echoes the 60s and 70s more than it does the 80s and 90s). Thus, shortly after the turn of the century, notions reappeared that we thought had been erased from our vocabulary: revolution, communism, insurrection, autonomy, etc. Today, such notions seem to constitute the lion’s part of any catalogue index. In fact, what is, once more, at stake in the notion of ‘political art’ today is the very possi-bility of engaging in what we obstinately call ‘art’. That is to say, ‘political art’ does not so much signify ‘protest art’ or ‘propa-ganda’ (although neither should be discarded as insignificant); ‘political art’’ is not so much an artistic genre among many, but touches upon the foundational problematic of modern art: that of the structural affinity between art and politics.

It is this structural affinity that is suggested in Jacques Rancière’s now commonplace notion of the ‘aesthetic regime’: the very definition of modern art entails that art carries

Guy

ben

-Ner

D

éjat

e de

ton

terí

as (

20

09

),

vide

o m

onoc

anal

Dv

D.

viv

e y

trab

aja

en T

el a

viv.

la h

isto

ria

se r

evel

a en

el vi

deo:

el ar

tist

a in

tent

a es

tafa

r al

sis

tem

a pe

ro f

inal

men

te s

e en

cuen

tra

atra

pado

en

el

mis

mo

sist

ema

que

quie

re m

anip

ular

. E

n es

te c

aso,

el

sis

tem

a so

n la

s fu

ndac

ione

s de

art

e qu

e su

bven

cion

an

el t

raba

jo.

Lo q

ue e

sas

fund

acio

nes

quie

ren

es u

n pr

oyec

to

artí

stic

o po

r el

que

el a

rtis

ta v

iaja

rá e

ntre

Tel

Avi

v y

Ber

lín,

ida

y vu

elta

, du

rant

e un

año

. Lo

que

no

sabe

n es

que

el

arti

sta

está

ena

mor

ado,

y q

ue la

pers

ona

a la

que

qui

ere

vive

en

Ber

lín.

La p

ropu

esta

del

pro

yect

o es

úni

cam

ente

un

a ta

pade

ra p

ara

finan

ciar

el d

eseo

del

art

ista

de

ver

a su

am

ante

cad

a se

man

a. S

in e

mba

rgo,

res

ulta

que

, in

clus

o ho

y en

día

, la

s su

bven

cion

es a

rtís

tica

s pu

eden

ser

más

es

tabl

es q

ue u

na r

elac

ión,

ya

que

la p

arej

a de

l art

ista

dec

ide

rom

per

con

él.

Por

des

grac

ia,

él s

igue

ten

iend

o qu

e vo

lar

de ida

y v

uelt

a ca

da s

eman

a, o

blig

ado

por

su c

ontr

ato,

ha

sta

final

de

año.

El ví

deo

de G

uy B

enN

er,

Déj

ate

de t

onte

rías

, es

una

re

flexi

ón d

el a

rtis

ta s

obre

su

inte

nto

de d

ifum

inar

el a

rte

y

la v

ida

mie

ntra

s in

tent

a cu

mpl

ir c

on e

l re

quis

ito

fina

ncie

ro

de e

ntre

gar

un

prod

ucto

al fi

nal de

l pr

oces

o. C

omo

en

otro

s ví

deos

de

Ben

Ner

, es

ta o

bra

tam

bién

lo

pres

enta

co

mo

prot

agon

ista

pri

ncip

al.

Aqu

í, e

l ar

tist

a ca

ptur

a

la c

onve

rsac

ión

tele

fóni

ca q

ue m

anti

ene

cons

igo

mis

mo

ben-N

er’s work is never off cam

era, and any editing is done entirely in cam

era. The narrative of the video, w

hich is the narrative of b

en-Ner’s life, is expressed in h

ebrew in

the form of a rhym

ing m

ora lity tale. The w

ork underlines the am

bivalent, precarious state in which the artist finds

himself, i.e. his ability to g

ain agency by m

anipulating reality for his ow

n benefit, combined w

ith his unmitigated

thrall to economic and cultural forces.

Image: stills from

Drop the m

onkey (2

00

9). C

ourtesy of the artist.

mie

ntra

s vi

aja

entr

e T

el A

viv

y B

erlín

. A

dife

renc

ia d

e lo

que

oc

urre

en

una

pelíc

ula

conv

enci

onal

, du

rant

e el

per

iodo

de

doc

e m

eses

el tr

abaj

o de

ben

-Ner

sie

mpr

e ti

ene

lug

ar

ante

la c

ámar

a, y

cua

lqui

er e

dici

ón s

e ha

ce c

ompl

etam

ente

an

te la

cám

ara.

La

narr

ativ

a de

l vid

eo,

que

es la

nar

rati

va

de la

vida

de

ben

-Ner

, se

exp

resa

en

hebr

eo,

en f

orm

a

de u

n cu

ento

rim

ado

con

mor

alej

a. e

l tr

abaj

o de

stac

a el

es

tado

pre

cari

o y

ambi

vale

nte

en e

l que

se

encu

entr

a

el a

rtis

ta,

p. e

.j.,

su c

apac

idad

par

a ga

nar

pode

r de

influ

enci

a m

anip

ulan

do la

real

idad

par

a su

pro

pio

bene

fici

o,

en c

ombi

naci

ón c

on s

u co

mpl

eta

sum

isió

n an

te la

s fu

erza

s ec

onóm

icas

y c

ultu

rale

s.

Imag

en:

foto

gram

a de

D

éjat

e de

ton

terí

as (

20

09

).

Cor

tesí

a de

l art

ista

.

Guy b

en Ner

Drop the m

onkey (20

09

), single channel video D

vD

. lives and w

orks in Tel-a

viv.

Throug

hout the video, the story unfolds: the artist tries to scam

the system but eventually finds him

self trapped in the sam

e system he w

ants to manipulate. T

he system in

this case is the art foundations that subsidize the work.

What these foundations sig

n up for is an artwork in w

hich the artist w

ill fly from T

el Aviv to B

erlin, back and forth, for a year. W

hat they don’t know is that the artist is in love,

and his love lives in berlin. T

he project proposal is only a cover for financing the artist’s desire to see his lover every w

eek. how

ever, it turns out that even today, artistic sub-sidies can be m

ore stable than a relationship, as the artist’s beloved decides to break up w

ith him. U

nluckily, bound by his contract, he still has to fly back and forth every w

eek, until the end of the year.

Guy b

en-Ner’s video, D

rop the monkey, is a selfreflec

tion on the artist’s attempt to blur art and life, w

hile com-

plying with the financial need to deliver a product at the end

of the process. as in other videos by b

en-Ner, this w

ork also depicts him

as the main protag

onist. here, the artist

captures the ongoing

phone conversation he has with

himself as he continues to fly betw

een Tel a

viv and berlin.

Unlike a regular film

, for the entire twelvem

onth period,

31

political promise. For Rancière, modern art no longer operates under the aegis of formal or technical perfection; what is at stake in modern art, as is the case for politics, according to Rancière, is not so much modes of doing but modes of being (a short-hand notion here may be that of forms-of-life: modern poli tics is a forms of anthropogenesis). both art and politics are engaged in the configuration of a specific space and time (Rancière’s muchquoted ‘distribution of the sensible’). The double bind between art and politics thus signifies that what can be defined as ‘art’ carries at least the promise of a re-dis tribution of the sensible, of a new community that no longer coincides with the state form. even though Rancière’s notion of the ‘aesthetic regime’ is certainly not immune to critique, it does show quite convincingly that modern art and modern politics are engaged in a sort of mutual becoming. Therefore, the history of modern art is primarily the history of art’s relation to politics; throughout the previous century, art has willingly placed its destiny in the hands of politics: from futurism to the Russian avant-garde, from situationism to Institutional Critique, the struggle over the definition of art went hand in hand with the struggle over the definition, and in fact the very possibility of politics as alternative to the modern, capitalist and bourgeois, state-form. This nexus between art and politics still determines current artistic practice and the ever-proliferating discourse on contemporary art.

however, crucially, if the definition and potential of art and politics is intimately related, there subsists a crucial tension be tween the two. Rancière’s ‘aesthetic regime’ is in fact founded on a paradox: (modern) art is art in so far as it is always already something other than art, i.e. the promise of a new politics, of new modes of being, of new communities, etc. From this paradox results the creed of ‘political art’: “art is exceptional and therefore may claim the universal.” It is this

32

article of faith, with all its resulting tensions, that still deter-mines the modus operandi of political art today. The very idea of ‘political art’ has meant that there is a relation of resem-blance between art and politics, but that does not necessarily imply a relation of equivalence: ‘political art’ entails a quasiimpossible position of both proximity and distance between the spheres of art and politics. as anthony Iles and marina vishmidt argue: if art wants to be effective politically, then it must, in the last instance, maintain a certain distance in relation to politics. art can be politically effective only if it does not fully coincide with politics. Ultimately, art needs to maintain a distance to be recognizable as a critical voice, to intervene, critically and effectively, in the political domain (we may even inverse Rancière’s paradox: political art is political art only in so far as it is always already something other than politics). The history of 20th-century art offers numerous examples of attempts to negotiate this irreducible tension. In much of modern and contemporary ‘political art’, this tension is in fact erased by dreaming up an ontological proximity, if not coinci-dence. One of the prevailing myths in political art is that art and politics are somehow on a par, since both are in the busi nes-ses of designing things, of imagining ways of being-together.

Nevertheless, the structural affinity between art and politics is first and foremost an intra-aesthetic problem. If the mutual becoming of art and politics has been vital in defining modern artistic practice, this does not imply that contemporary political practice (in particular its parliamentary variety) is necessarily concerned by art, or anything conceptualized in the sphere of art. To an unfortunately large extent, ‘political art’ remains an intra-aesthetic problem: it is very rarely operative outside of the narrow sphere of artistic practice and discourse. The relation-ship between political art and political consensus is, even in situations of revolutionary fervor, profoundly dissymmetrical.

33

art rarely gets to beat organized politics in the business of designing communities and lives. In this sense, once more, art does not have an ontological privilege or proximity in rela-tion to politics. In fact, the construction of forms-of-life entails (collective) organization, duration and critical mass. In its current dominant form at least, contemporary art appears to be structurally incapable of all of these things: the still dominant exhibition format, the hugely influential aesthetic format of event-based art (which ranges from performances and in-situ interventions to the art festival), and the romantic-libertarian subjectivity that still determines artistic modes of being (and that, as we will see, fits the working subject of modern-day capitalism like a glove) seem to cripple a politics that would last long enough to be operative effectively as well as the organization of a sustainable collective. This effectively condemns ‘political art’ to interventionism and a subsequent interventionist aesthetic that is as spectacular as it is limited. more often than not, contemporary political art thus fails to engage in any kind of unexpected alliance — and only these are effective politically — and ends up replicating the very socio- political context it claims to agitate against. Political art, fundamentally, does not translate into a form of constituent political practice (it does not call anything new into being: no new collectivity). In practice, this dissymmetry between ‘political art’ as the foundational problematic of modern art and its lack of constituent power, results in an ‘political’ artistic practice that is de facto impotent, but nevertheless grounded in and justified by the assumption of the ontological proximity and privilege of art in relation to politics. Consequently, this supposed proximity results in the confusion between microcosm and macrocosm: the microcosm of the art world metonymically becomes the placeholder for the macrocosm of politics. Artistic autocritique thus becomes

34

sociopolitical critique. In reality, ‘political art’ remains stuck in a self-contradictory unhappy performance, by proclaiming to exist politically and to structurally fail to do. much of today’s ‘political art’ therefore seems to reflect the male narcissism of lower management’s attempts to ‘empower’.

aDjeCTIves IN seaRCh OF NOUNs

Fundamentally, the failure to negotiate the tension described above, obscures any significant inquiry into the purpose of (political) artistic practice today, within a neoliberal political economy, within the realities of what we now, often indis-criminately, call the creative economy, cognitive capitalism, immaterial labor and so forth. Today’s political art runs up against its de facto role within (or symbiosis with) neoliberal capitalism as long as it assumes the possibility of an unme-diated transition from the microcosm of the (artistic) community to the macrocosm of politics. We may call this the ‘tilt shift’ effect of political art. The microcosm of the artistic event is projected onto the macrocosm of society (leaving us models for models for models…). exactly how this transition operates remains unexplained.

however, explaining this transition is crucial given the highly ambiguous role art, and culture at large, plays in today’s eco-nomic regime, which the sociologists boltanski and Chiapello call ‘the new spirit of capitalism’. To be brief (as this is a well-known narrative by now): the center of gravity of Western economies has moved towards the immaterial and the cognitive (see, for example, the dominance of the financial markets, the dominance of speculation over production). The valorization of art is quasiidentical to the modus operandi of contemporary capitalism: it operates through derived capital accumulation

35

such as city branding or the never-ending circus of biennials and festivals. structurally, the artistic economy operates through various modes of speculation; the valorization of art is not fundamentally different from that of designer and luxury goods. Furthermore, because of the shift towards immaterial production, ‘art’ increasingly blends into the ‘creative indus-tries’ (design, fashion, media, etc.) that are now advertised as the spearheads of the Western economy. In this new economy that thrives upon the cognitive and emotional exploitation of our communicative and creative skills, total flexibility and perma-nent mobilization, the artist serves as the new stakhanov, the soviet model worker. as hito steyerl calls it, the artist is the creative or knowledge worker ‘who has nothing to offer but her free labor’, and is thus condemned to perpetually invest in her own ‘human capital’. artistic labor at least appears to coincide with, if not provide the model for, modes of production as well as the type of subjectivity that defines socalled postFordist labor. as Richard Florida infamously argued: today, the model for our working environment is no longer henry Ford’s factory, but andy Warhol’s Factory. What has long been the privilege of art — communication, creativity, collaboration — has moved to the forefront of the economy. In a sense, the capi-talist logic of abstraction (that is to say: the designation of ‘work’ as the ability to perform any kind of labor activity) that is at the root of both art and labor, has come back to haunt art. Today, art has in fact been superseded in the process of labor’s further abstraction into the domain of the creative and the cognitive; having fuelled the creative industries, art is now in the process of dissolving into the creative economy. The precarious working conditions of the art world and the pre carious status of the artist have been appropriated by the new spirit of capitalism, and are now, in a sense, being turned against art: art can no longer claim its exceptional

36

status (whereas, as we have seen, art’s political significance to a large extent depends on that exceptional status). In this context, for the German art theorist Isabelle Graw, “autonomy is no longer the dominant structural characteristic of the field of art.” Today, the “external constraints are in the foreground” of what defines ‘art’; for Graw, this entails that we can only speak of an artistic field that is at best ‘relatively heteronomous’. an example of this ‘relative hetero-nomy’— and this will be the last example of this arguably bleak tone — is the ever-increasing synergy between art and education: art has moved into the academic world (with its MFA’s, curatorial programs, and the now ubiquitous ‘artistic research’), which often acts as a shelter against precarization. Yet, academic institutions are equally subjected to the econo-mization of knowledge work and thus drag art back into the very mechanism it tries to escape. In the past decade, the realiza-tion of the bologna treaty has dramatically reorganized higher education according to the decrees of neoliberalism.

however, the fact that ‘political art’ is, in the first place, as we saw, an intra-aesthetic problem, and the added fact that there is a profound dissymmetry between art’s political radius or impact and its immediate political context, em phatically, does not mean that there cannot be, and, even less so, that there should not be any affiliation between art and alternative ways of imagining politics and political praxis. as we have seen, this affiliation should not be translated into an ontological proximity or unmediated and therefore privileged relationship between art and politics. On the contrary, the stakes of ‘political art’ are set in the zone of indistinction between art and political practice. It is the dynamics between proximity and distance that makes for political art. Political art, first and foremost, signifies the potential politicization of art: the political is an adjective in search of a noun. and what can

C.a

.s.I

.T.a

.

(lor

eto

alo

nso,

edu

ardo

Gal

vagn

i y

Die

go d

el P

ozo)

e

l obr

ador

de

el e

nte

tran

spar

ente

,

bib

liote

ca-d

ecál

ogo

y m

edia

teca

(2

00

6-

en c

urso

), in

stal

ació

n.

viv

en y

tra

baja

n en

mad

rid

y m

éjic

o.

est

a no

es

una

bibl

iote

ca n

orm

al.

los

libro

s no

est

án o

rga-

niza

dos

por

orde

n al

fabé

tico

y t

ampo

co s

e pu

eden

sac

ar

en p

rést

amo.

en

luga

r de

ello

, lo

s co

nten

idos

est

án

map

eado

s de

acu

erdo

con

las

pre

mis

as c

once

ptua

les

del

Dec

álog

o de

el e

nte

tran

spar

ente

, un

pro

yect

o ar

tíst

ico

que

actú

a co

mo

aleg

oría

del

tra

bajo

y d

e la

s co

ndic

ione

s ac

tual

es d

e pr

oduc

ción

. P

or e

jem

plo,

una

sec

ción

de

libro

s se

llam

a “T

raba

jam

os c

uand

o co

nsum

imos

, cu

ando

est

able

-ce

mos

rel

acio

nes

soci

ales

, cu

ando

nos

com

unic

amos

”,

mie

ntra

s qu

e ot

ra s

e lla

ma

“Pre

cari

ousn

ess:

our

lab

our

prob

lem

s ar

e ou

r pe

rson

al p

robl

ems”

. e

n es

ta b

iblio

teca

fu

era

de lo

com

ún a

lgun

as p

arte

s de

los

text

os e

stán

su

bray

adas

y los

vis

itan

tes

no s

olo

pued

en e

ncon

trar

lib

ros

y ar

tícu

los,

sin

o ta

mbi

én r

efer

enci

as y

enl

aces

a

otro

s co

nten

idos

, in

clui

do m

ater

ial a

udio

visu

al.

el o

brad

or d

e e

l ent

e tr

ansp

aren

te,

conc

ebid

o po

r C

.A.S

.I.T

.A.,

es

una

inst

alac

ión

que

actú

a co

mo

un lu

gar

para

refl

exio

nar,

un

espa

cio

de r

euni

ón y

una

her

ram

ient

a pa

ra la

defi

nici

ón s

ocia

l del

tra

bajo

. D

esar

rolla

do in

icia

lmen

te

com

o un

esp

acio

de

trab

ajo

abie

rto

de lo

s m

iem

bros

del

events that encourage public participation. Conceptually, it

follows the post-Fordist conditions of production, leaving

no place for a distinction between consum

ption, comm

uni-cation, social relations and production. T

he aim is to pro-

duce discur sive and symbolic value, w

here the place of w

ork and the result of work are intertw

ined.

Image: Installation view

of the library-D

ecalogue and media

archive, (2

00

6- ongoing).

Courtesy of the artists.

cole

ctiv

o y

post

erio

rmen

te c

omo

un á

rea

de t

raba

jo p

ara

el

púb

lico,

el p

roye

cto

tam

bién

incl

uye

un a

rchi

vo m

ulti

med

ia

y un

pro

gram

a de

act

ivid

ades

que

fom

enta

la p

arti

cipa

ción

pú

blic

a. C

once

ptua

lmen

te,

sig

ue las

con

dici

ones

de

pro-

ducc

ión

post

ford

ista

s, y

no

deja

luga

r pa

ra la

dis

tinc

ión

entr

e el

con

sum

o, la

com

unic

ació

n, la

s re

laci

ones

soc

iale

s y

la p

rodu

cció

n. e

l obj

etiv

o es

pro

duci

r va

lor

disc

ursi

vo

y si

mbó

lico,

don

de e

l lu

gar

de

trab

ajo

y el

res

ulta

do d

el

trab

ajo

esté

n en

trel

azad

os.

Imag

en:

vis

ta d

e la

inst

alac

ión

b

iblio

teca

-dec

álog

o y

med

iate

ca

(20

06

- en

cur

so).

C

orte

sía

de lo

s ar

tist

as.

C.a

.s.I.T

.a.

(loreto alonso, e

duardo Galvagni

and Diego del P

ozo) T

he Foundry of the Transparent e

ntity, library-D

ecalogue and media a

rchive (2

00

6– ongoing), installation.

live and work in m

adrid and mexico.

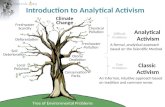

This is not a norm

al library. The books are not organized in

alphabetical order and they can’t be lent out either. Instead, the contents are m

apped out according to the

conceptual premises of The D

ecalogue of The Transparent e

ntity, an art project that acts as an allegory of labor and

the contemporary conditions of production. F

or example,

one section of books is called “We w

ork when w

e consume,

when w

e establish social relations, when w

e comm

unicate”, w

hile another section is called “Precariousness: our labour

problems are our personal problem

s”. In this unusual library, certain parts of the texts are underlined, and not only can visitors find books and articles, but they can also find references and links to other content, including audiovisual m

aterials.The Foundry of the Transparent e

ntity, conceived by C

.A.S

.I.T.A

, is an installation that acts as a place to reflect, a space to m

eet and a tool for the social definition of work.

Initially developed as an open workspace for the m

embers

of the artist colecive and later as a work area for the public,

the project also contains a media archive and a program

of

41

be politicized, as Mladen Stilinović’s artist at Work demon-strates, is art, in so far as it is potentially constitutive of forms-of-life. The choice concerning political art is not: absolute autonomy versus absolute heteronomy: the purity-cum- universality of art versus the impurity of the market. The issue is: how to make art pour into other forms-of-life? This is not to be confused with the social democrat’s dream of ‘socially relevant art’, neither with a desire for the dialectical supersession of art, and it certainly should not be confused with the immediate passage from art to revolutionary politics. Rather, ‘political art’ refers here to art as a domain that allows for the constitution of modes of being, which, as such, — that is to say: as modes of presence in the world, as ways of experiencing life — can be potentially politicized. art may pour into politics, art can be politicized precisely be-cause art institutes modes of being. Rather than assuming the equivalence between art and politics, I would argue that ‘political art’ refers to an adjective in search of a noun, and vice versa: it refers to a process of politicization, which is a very precarious process indeed (and the chances of a missed encounter between adjectives and nouns here are legion).

I am borrowing the notion of form-of-life primarily from Giorgio agamben and its rethinking by Tiqqun: the emphasis in form-of-life is precisely on ‘form’: how do we incline our lives? The notion of form-of-life does not refer to the capitalist idea of ‘lifestyle’, of the shaping of life as individual life, usually and paradoxically by purchasing generic attributes (whatever: apple laptops and the latest in eco footwear), nor does it refer to the idea of life-as-a-work-of-art (life as ‘general perfor-mance’, as Dutch art theorist sven lütticken calls it, which as it happens perfectly fits an economic model that demands permanent adaptability, mobility and self-promotion), but rather to the singular ‘how’ of our being in a situation, as Tiqqun

42

call it. The million dollar political question is ‘how to ignite the game between forms-of-life’: how to politicize the dynamics between forms of being. The emphasis on the form-of-life and its politicization is crucial in a socio-political context in which the mediators between state power (which at this point is indis-tinguishable from global corporate and financial capitalism) and individual lives are rapidly vanishing. The infrastructure of civil society, of which the art world has been a vital part, and collective shelters against economic warfare, such as the welfare state, are being rapidly dismantled. Therefore, any constituent political potential is no longer to be located in these forms of mediation, but in the direct politicization of forms-of-life (arguably, to a very large extent, this will be part of fairly dark socio-political scenarios that involve the unraveling of the social fabric, growing nepotism and new forms of social inequality). As the American anthropologist David Graeber says: “artists and those drawn to them have created enclaves where it has been possible to experiment with forms of work, exchange and production radically different from those promoted by capital [...] These have been spaces where people can experiment with radically different, less alienated forms of life.” In this sense, collectively constituted artistic subjectivity becomes a form-of-life, becomes active as a political operator, becomes a constituent political force. The zone of indistinction between art and politics permits making political use of an artistic identity that is historically defined and institutionally embedded to create a political subject that is not, however, limited by its history and its insti-tutions. The choice is, therefore, not between the fallacy of art’s unmediated political significance or the alternative fallacy of art’s complete ideological subjection and de facto impotence. Just as the myth of art’s real equivalence with politics leads contemporary art into an impasse (when it turns out that,

43

in practice, the affection is rather unilateral), obsessing about art’s embeddedness in its historical political situation is equally unproductive. The fact that art today is an integral part of the neoliberal economy does not necessarily make it impotent politically, although it makes its political significance so much harder to establish. art is never purely inside or outside its political context, rather: it performs a delicate balancing act; it is in this zone of indistinction that it consti-tutes forms-of-life that can be politicized.

In The Praise of laziness, Mladen Stilinović argues: artists in the West are not lazy and therefore not artists, but rather producers of something [...] Their involvement with matters of no importance, such as production, promotion, gallerysystem, museum system, competition system (who is first), their preoccupation with objects, all that drives them away form laziness, from art. just as money is paper, so a gallery is a room.

As Stilinović shows, the very possibility of ‘art’ lies in the con-stitution of forms-of-life that refuse any productivist ontology and the institutions that thrive upon such a productivism. Stilinović’s artist at Work thus refutes both the phagocytosis of art by the new spirit of capitalism and the running around in circles of (new) institutional critique, which, by questioning the complicity between art and the political and economic infrastructure, merely ends up replicating these. The sleep

44

laboratory we get to enter in artist at Work constitutes a form-of-life that, far from the moralizing narratives of ‘slow living and ‘the art of laziness’, sets the stakes for ‘political art’ today.

¿Por qué el arte ya no existe en Occidente? la respuesta es sencilla. los artistas occidentales no son perezosos. — Mladen Stilinović

45

entra en el laboratorio

del sueño: arte, trabajo,

política

joost de bloois

46

DeNTRO Del labORaTORIO Del sUeñO

artist at Work (1978), de Mladen Stilinović, evoca asociaciones sorprendentemente disonantes y trae a la mente los estudios fotográficos de movimiento humano y animal de eadweard Muybridge. En la serie de fotos de Stilinović, al principio vemos al artista con los ojos abiertos, quizás cavilando algo, con los brazos detrás de la cabeza; después, parece estar profundamente dormido, girándose sobre su costado y su espalda, inmerso del todo en la coreografía del sueño. artist at Work presenta un estudio peculiar del no movimiento Oblomoviano; o quizás del movimiento interior, satirizando el cliché freudiano romántico del artista como trabajador del inconsciente. En la obra de Stilinović, el estudio del artista actúa como un laboratorio del sueño: se nos ha dejado entrar para ser testigos del trabajo artístico como trabajo soñado, pero solo si susurramos. a pesar de su rechazo obstinado a ser franco ideológicamente (lo único que se escucha es un ligero resoplido), artist at Work es una pieza empáticamente política. La obra de Stilinović logra por primera vez su significado político obvio en el contexto histórico de la Yugoslavia comunista. ejecuta el reverso de la celebración comunista del trabajo que, políticamente, solo tolera sonámbulos. El cliché moderno del artista libertario que abandona la subjetividad burguesa quedándose en la cama, en la obra de Stilinović, se convierte en espantosamente claustrofóbico. el dormitorio es el estudio real del artista, ya que en cualquier lugar externo a él, se verá obligado a participar en un tipo distinto de subjetividad (y llegará a pensar sobre ello: ¿quién está observando a nuestro ‘artista trabajando’ en la pieza de Stilinović?). artist at Work es una obra abiertamente política precisamenteporque adopta una postura antiproductivista: rechaza la ontología marxista del Gattungswesen [‘esencia de la especie’] — del hombre como

(and demand) for flexible w

ork. As in H

sieh’s act, workers as

well as artists have to be aw

ake and aware on a hourly

basis in order to survive in the capitalist system.

Image: s

tills from O

ne Year P

erformance 19

80

–198

1 (T

ime C

lock Piece). C

ourtesy of the artist and s

ean kelly G

allery, N

ew York.

Teh

chin

g h

sieh

P

erfo

rman

ce d

e un

año

, 19

80

-19

81

(P

ieza

del

rel

oj d

e co

ntro

l) (

198

0–1

98

1),

vi

deo

digi

tal d

e un

a pe

lícul

a de

16

mm

.

viv

e y