Jems201205 dl

-

Upload

santiago-clei-wandeson-ferreira -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

1.911 -

download

2

Transcript of Jems201205 dl

Choose 13 at www.jems.com/rs

FP-Spread.indd 5 4/23/2012 10:35:52 AM

JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES

TheConscience

of EMS

Contents

Premier media Partner of the iafC, the iafC emS SeCtion & fire-reSCue med www.jems.com maY 2012 JEMS 7

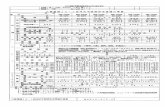

Departments & columns 9 i Load & go i now on JemS.com 14 i EMS in action i Scene of the month 16 i FroM thE Editor i on the front Lines By a.J. heightman, mPa, emt-P 18 i LEttErS i in Your Words 20 i Priority traFFic i news You Can use 24 i LEadErShiP SEctor i Crisis management By Gary Ludwig, mS, emt-P 27 i ManagEMEnt FocuS i extra Set of hands By richard huff, nremt-B 30 i trickS oF thE tradE i numbers �By thom dick 32 i caSE oF thE Month i miracle in the desert �By Jeff Westin, md; Pat Songer, nremt-P, aSm; Kelly Buchanan,

md; Loren Gorosh, md; ryan hodnick, do; & Bryan e. Bledsoe, do, faCeP, faaem

36 i rESEarch rEviEw i What Current Studies mean to emS �By david Page, mS, nremt-P 74 i ad indEx 75 i EMPLoyMEnt & cLaSSiFiEd adS 78 i thE LightEr SidE i Zombie emS �By Steve Berry 82 i LaSt word i the ups & downs of emS

46 i PrEParEd For thE worSt i tactical training offers many benefits to emS�� By�William�Justice,�NREMT-P;�Lt.�Kerry�Massie,�NREMT-I;�&�Jeffrey�M.�Goodloe,�

MD,�NREMT-P,�FACEP

52 i PartnErS in criME i emS provides a training program for local law enforcement� By�Capt.�Mario�Ramirez,�MD,�MPP;�Andrew�N.�Pfeffer,�MD;�Greg�Lee;�&�Corey�M.�

Slovis,�MD,�FACEP

56 i what’S buggin’ EMS i how to rid your rigs of a bedbug infestation�� � By�Wayne�M.�Zygowicz,�BA,�EFO,�EMT-P

62 i brEaking barriErS i Practice cultural sensitivity to provide care to immigrant

communities�By�Keith�Widmeier,�NREMT-P,�CCEMT-P,�EMS-I,�BA;�&�Emily�Coffey,�BA,�NREMT-P

68 i MuLtiPLE airwayS i rapid assessment is key for managing numerous patients�� � By�Paul�E.�Phrampus,�MD

About the CoverA Pima County (Ariz.) Sheriff’s Department deputy demonstrates the value of early law enforcement officer delivery of EMS treatment, particularly at an active-shooter incident or situations where it’s unsafe for EMS to enter. Find out how training and equipping first-arriving police officers, sheriff’s deputies and highway patrol officers can help save patients (and other officers) in “On the Front Lines,” p 16; “Beyond the Tape,” pp 38–45; “Prepared for the Worst,” pp. 46–51; and “Partners in Crime,” pp. 52–55. Photo Matthew StrauSS

MAy 2012 VOL. 37 NO. 5

i bEyond thE taPE i Law enforcement officers make major impact

as initial care providers By�David�Kleinman,�NREMT-P,�&�Tammy�Kastre,�MD

38

i 62

i 68

007_TOCMay.indd 7 4/20/2012 11:56:54 AM

www.jems.com mAY 2012 JEMS 9

The EMS 10: Innovators in EMS award winners pose at the dinner where they were honored for their achieve-ments. Pictured from top left are Tom Bouthillet, Michael Millin, Seth Hawkins, Will Smith, Pat Songer, Rob Lawrence, Stephanie Haley-Andrews and David Reinis. Not pictured are Mary Meyers, Paul Paris, E. Reed Smith and Todd Stout. In case you’ve missed the past winners of this annual award, make sure to check them out at jems.com/ems10

To vote, do a keyword search on JEMS.com for “polls.”s jems.com/poll2012/

The mobile version

s http://m.jems.com/poll/

may poll quesTion How do you celebrate EMS Week?

like usfacebook.com/jemsfans

follow us twitter.com/jemsconnect

geT connecTedlinkedin.com/groups?about=&gid=113182

ems news alerTsjems.com/enews

besT bloggersFireEMSBlogs.com

check iT ouTjems.com/ems-products

JEMS.com offers youoriginal content, jobs,products and resources.But we’re much morethan that; we keepyou in touch withyour colleaguesthrough our:

> Facebook fan page;> JEMS Connect site;> Twitter account;> LinkedIn profile;> Product Connect site; and> Fire EMS Blogs site.

follow us on

load & go log in for EXClUSiVE ConTEnT

A BETTEr WAy To LEArn

JEMSCE.CoM onLInE ConTInuIng

EduCATIon ProgrAM

april poll resulTsWhich is a more dangerous location for EMS providers driving an ambulance?

34% Interstate or rural highway

27% rural streets

39% Suburban streets.

Innovators dine

Sponsored Product FocusspeechmikeWith more than 50 years of experience in the voice technology market, Philips Speech Processing provides innovative, practical dictation and transcription solutions that allow professionals to increase productivity and efficiency. As the leading dictation device on the market, the SpeechMike is specifically designed to enhance productivity for optimal speech recognition results. Its ergonomic, intuitive design boasts dictation control, play-back speakers, and PC navigation in a single device, and it allows users to send sound files for transcription at the press of a button.

s Check out their ad on JEMS.com!

p My agency hosts an event.p I recognize it with coworkers.p I don’t even know when it is!p other

Pho

To g

ary

JaC

kSo

n

009_Load.indd 9 4/17/2012 10:10:11 AM

Editor-in-ChiEf I A.J. heightman, MPA, EMt-P I [email protected] Editor I Jennifer Berry I [email protected]

AssoCiAtE Editor I Lauren hardcastle I [email protected] Editor I Allison Moen I [email protected]

AssistAnt Editor I Kindra sclar I [email protected] nEws/BLoG MAnAGEr I Bill Carey I [email protected]

MEdiCAL Editor I Edward t. dickinson, Md, nrEMt-P, fACEP tEChniCAL Editors

travis Kusman, MPh, nrEMt-P; fred w. wurster iii, nrEMt-P, AAsContriButinG Editors I Bryan Bledsoe, do, fACEP, fAAEM; Ann-Marie Lindstrom

EditoriAL dEPArtMEnt I 800/266-5367 I [email protected]

Art dirECtor I Liliana Estep I [email protected] iLLustrAtors

steve Berry, nrEMt-P; Paul Combs, nrEMt-BContriButinG PhotoGrAPhErs

Mark C. ide, Craig Jackson, ray Kemp, Kevin Link, Julie Macie, Jeffrey Mayes, Courtney McCain, rick McClure, tom Page, rick roach,

steve silverman, Chris swabb, Grant therrien, raul torres

dirECtor of eProduCts/ProduCtion I tim francis I [email protected] CoordinAtor I Matt Leatherman I [email protected]

AdvErtisinG dirECtor I Judi Leidiger I 619/795-9040 I [email protected] ACCount rEPrEsEntAtivE I Cindi richardson I 661-297-4027 I

[email protected] sALEs CoordinAtor I Elizabeth Zook I [email protected]

sALEs & AdMinistrAtivE CoordinAtor I Liz Coyle I [email protected] eMEdiA CAMPAiGn MAnAGEr I Lisa Bell I [email protected]

AdvErtisinG dEPArtMEnt I 800/266-5367 I fax 619/699-6722

MArKEtinG dirECtor I debbie Murray I [email protected] MAnAGEr I Melanie dowd I [email protected]

dirECtor, AudiEnCE dEvELoPMEnt & sALEs suPPort I Mike shear I [email protected] dEvELoPMEnt CoordinAtor I Marisa Collier I [email protected]

suBsCriPtion dEPArtMEnt I 888/456-5367

rEPrints, ePrints & LiCEnsinG I wright’s Media I 877/652-5295 I [email protected]

eMedia Strategy I 410/872-9303 I MAnAGinG dirECtor I dave J. iannone I [email protected]

dirECtor of eMEdiA sALEs I Paul Andrews I [email protected] dirECtor of eMEdiA ContEnt I Chris hebert I [email protected]

eMS today ConferenCe & expoSitionrEEd ExhiBitions I Christine ford I 203/840-5391 I [email protected]

EMs todAy ExhiBit sALEs I 203/840-5611Jeff stasko I [email protected]

elSevier publiC SafetyviCE PrEsidEnt/PuBLishEr I Jeff Berend I [email protected]

foundinG Editor I Keith Griffiths

foundinG PuBLishErJames o. Page

(1936–2004)

JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES

TheConscience

of EMS

JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES

TheConscience

of EMS

Choose 16 at www.jems.com/rs

010_012_STAFFBOXES.indd 10 4/17/2012 10:12:46 AM

Choose 17 at www.jems.com/rs

4C J

EM

S_1

1

FP_RT.indd 1 4/16/2012 11:06:24 AM

JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES

TheConscience

of EMS

JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES

TheConscience

of EMS

EDITORIAL bOARDWILLIAm K. ATKInsOn II, PHD, mPH, mPA, EmT-PPresident & Chief Executive Officer

WakeMed Health & Hospitals

JAmEs J. AugusTInE, mDMedical Advisor, Washington Township (OH) Fire Department Director of Clinical Operations, EMP ManagementClinical Associate Professor, Department of

Emergency Medicine, Wright State University

sTEvE bERRy, nREmT-PParamedic & EMS Cartoonist, Woodland Park, Colo.

bRyAn E. bLEDsOE, DO, FACEP, FAAEmProfessor of Emergency Medicine, Director, EMS Fellowship

University of Nevada School of MedicineMedical Director, MedicWest Ambulance

CRIss bRAInARD, EmT-PDeputy Chief of Operations, San Diego Fire-Rescue

CHAD bROCATO, DHs, REmT-PAssistant Chief of Operations, Deerfield Beach Fire-Rescue Adjunct Professor of Anatomy & Physiology, Kaplan University

J. RObERT (ROb) bROWn JR., EFOFire Chief, Stafford County, Va., Fire and Rescue Department Executive Board, EMS Section,

International Association of Fire Chiefs

CAROL A. CunnIngHAm, mD, FACEP, FAAEmState Medical Director

Ohio Department of Public Safety, Division of EMS

THOm DICK, EmT-PQuality Care Coordinator

Platte Valley Ambulance

mARC ECKsTEIn, mD, mPH, FACEPDirector of Prehospital Care, Los Angeles County/

USC Medical CenterMedical Director, Los Angeles Fire DepartmentProfessor, Emergency Medicine,

University of Southern California

CHARLIE EIsELE, bs, nREmT-PFlight Paramedic, State Trooper, EMS Instructor

bRuCE EvAns, mPA, EmT-P Deputy Chief, Upper Pine River Bayfield Fire Protection, Colorado District

JAy FITCH, PHDPresident & Founding Partner, Fitch & Associates

RAy FOWLER, mD, FACEPAssociate Professor, University of Texas Southwestern SOMChief of EMS, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Chief of Medical Operations,

Dallas Metropolitan Area BioTel (EMS) System

ADAm D. FOx, DPm, DOAssistant Professor of Surgery,

Division of Trauma Surgery & Critical Care, University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey

Former Advanced EMT-3 (AEMT-3)

gREgORy R. FRAILEy, DO, FACOEP, EmT-PMedical Director, Prehospital Services, Susquehanna HealthTactical Physician, Williamsport Bureau of

Police Special Response Team

JEFFREy m. gOODLOE, mD, FACEP, nREmT-PAssociate Professor & EMS Division Director,

Emergency Medicine, University of Oklahoma School of Community Medicine

Medical Director, EMS System for Metropolitan Oklahoma City & Tulsa

KEITH gRIFFITHsPresident, RedFlash GroupFounding Editor, JEMS

DAvE KEsEg, mD, FACEPMedical Director, Columbus Fire Department Clinical Instructor, Ohio State University

W. Ann mAggIORE, JD, nREmT-PAssociate Attorney, Butt, Thornton & Baehr PCClinical Instructor, University of New Mexico,

School of Medicine

COnnIE J. mATTERA, ms, Rn, EmT-PEMS Administrative Director & EMS System Coordinator,

Northwest (Illinois) Community Hospital

RObERT J. mcCAugHAnChief, City of Pittsburgh EMS Chair, IAEMSC Metro Chief’s Section

RObIn b. mcFEE, DO, mPH, FACPm, FAACTMedical Director, Threat Science Toxicologist & Professional Education Coordinator,

Long Island Regional Poison Information Center

mARK mEREDITH, mDAssistant Professor, Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics,

Vanderbilt Medical Center Assistant EMS Medical Director for Pediatric Care,

Nashville Fire Department

gEOFFREy T. mILLER, EmT-PDirector of Simulation Eastern Virginia Medical School,

Office of Professional Development

bREnT myERs, mD, mPH, FACEPMedical Director, Wake County EMS SystemEmergency Physician, Wake Emergency Physicians PAMedical Director, WakeMed Health & Hospitals Emergency

Services Institute

mARy m. nEWmAnPresident, Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation

JOsEPH P. ORnATO, mD, FACP, FACC, FACEPProfessor & Chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine,

Virginia Commonwealth University Medical CenterOperational Medical Director, Richmond Ambulance Authority

JERRy OvERTOn, mPAChair, International Academies of Emergency Dispatch

DAvID PAgE, ms, nREmT-PParamedic Instructor, Inver Hills (Minn.) Community CollegeParamedic, Allina Medical TransportationMember of the Board of Advisors,

Prehospital Care Research Forum

PAuL E. PEPE, mD, mPH, mACP, FACEP, FCCmProfessor, Surgery, University of Texas

Southwestern Medical CenterHead, Emergency Services, Parkland Health & Hospital SystemHead, EMS Medical Direction Team,

Dallas Area Biotel (EMS) System

DAvID E. PERssE, mD, FACEPPhysician Director, City of Houston Emergency Medical Services Public Health Authority, City of Houston Department. of Health

& Human ServicesAssociate Professor, Emergency Medicine, University of Texas

Health Science Center—Houston

JOHn J. PERuggIA JR., bsHus, EFO, EmT-P Assistant Chief, Logistics, FDNY Operations

EDWARD m. RACHT, mDChief Medical Officer, American Medical Response

JEFFREy P. sALOmOnE, mD, FACs, nREmT-PAssociate Professor of Surgery,

Emory University School of MedicineDeputy Chief of Surgery, Grady Memorial HospitalAssistant Medical Director, Grady EMS

KATHLEEn s. sCHRAnK, mDProfessor of Medicine and Chief,

Division of Emergency Medicine, University of Miami School of Medicine

Medical Director, City of Miami Fire RescueMedical Director, Village of Key Biscayne Fire Rescue

JOHn sInCLAIR, EmT-PInternational Director, IAFC EMS SectionFire Chief & Emergency Manager, Kittitas Valley Fire & Rescue

COREy m. sLOvIs, mD, FACP, FACEP, FAAEmProfessor & Chair, Emergency Medicine,

Vanderbilt University Medical CenterProfessor, Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical CenterMedical Director, Metro Nashville Fire DepartmentMedical Director, Nashville International Airport

bARRy smITH, EmT-PCQI Coordinator, Regional EMS Authority (REMSA), Reno, Nev.

WALT A. sTOy, PHD, EmT-P, CCEmTPProfessor & Director, Emergency Medicine,

University of PittsburghDirector, Office of Education,

Center for Emergency Medicine

RICHARD vAnCE, EmT-PCaptain, Carlsbad Fire Department

JOnATHAn D. WAsHKO, bs-EmsA, nREmT-P, AEmDAssistant Vice President, North Shore-LIJ Center for EMSCo-Chairman, Professional Standards Committee,

American Ambulance AssociationAd-Hoc Finance Committee Member, NEMSAC

KEITH WEsLEy, mD, FACEPMedical Director, HealthEast Medical Transportation

KATHERInE H. WEsT, bsn, mED, CICInfection Control Consultant,

Infection Control/Emerging Concepts Inc.

sTEPHEn R. WIRTH, Esq.Attorney, Page, Wolfberg & Wirth LLC.Legal Commissioner & Chair, Panel of Commissioners,

Commission on Accreditation of Ambulance Services (CAAS)

DOugLAs m. WOLFbERg, Esq.Attorney, Page, Wolfberg & Wirth LLC

WAynE m. ZygOWICZ, bA, EFO, EmT-PEMS Division Chief, Littleton Fire Rescue

12 JEMS MAY 2012

010_012_STAFFBOXES.indd 12 4/17/2012 10:12:53 AM

>> Photos AssociAted PressEMS IN ACTIONscene of the month

14 JEMS MAY 2012

Providers from Southwest Ambulance prepare to initiate the transfer of U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D-Ariz.) to

TIRR Memorial Hermann Rehabilitation Hospital in Houston on Jan. 26, 2011. Providers use extreme caution to provide follow-up treatment for Giffords’ critical head injury after she was shot at a Congress On Your Corner event at a Safeway shopping center outside of Tucson, Ariz. This high-profile case serves as a reminder to EMS providers that they’re never able to predict what patients they may have the opportunity to treat or trans-fer. Thanks to the excellent care delivered to Giffords and the team effort between law enforcement and EMS, Giffords was transported in a safe and coordinated manner and has made outstanding progress in her recovery.

HIgH-PROfIlE cAre

014_015_EMSinAction.indd 14 4/17/2012 10:13:38 AM

To truly understand the importance of the content in the May 2012 issue of JEMS, which focuses on updating the

training and equipment carried by law enforce-ment officers in your EMS system, I’d like you to watch a gut-wrenching clip from the 1988 movie, In the Line of Duty. The clip is only eight minutes long, but I think those eight minutes will be some of the most stressful, and emo-tionally-charged of your career.

The clip shows a firefight that occurred on the streets of Miami on April 11, 1986, between eight FBI agents and two known murderers/bank robbers: Michael Platt and William Matix. Before the fight was over, multiple FBI agents were killed by .223 gunshots from a Ruger mini-14 in the hands of Michael Platt.

The brave FBI agents who were engaged in this street battle were not armed with weapons or ammunition that could make the most pro-nounced impact on their targets. Platt himself had sustained 12 gunshot wounds (9 mm, .38 and 00 shot) but continued to fight.

This firefight and the resulting aftermath resulted in dramatic changes in the way we equip law enforcement officers. It was the gen-esis of the 10 mm and .40 S&W rounds and use of more advanced weaponry by law officers.

When I watched this powerful docudrama in 1988, it dramatically affected me as an edu-cator and EMS system planner. It also sig-nificantly changed the way I thought about the EMS/law enforcement interface and the need for better frontline care by (and for) police officers and other members of the emergency response family.

At this year’s National Association of EMS Physician Conference in Tucson, Ariz., in January, I heard a hidden message during a keynote lecture by Brad Bradley, EMT-P, of the Northwest Fire Rescue District, and Joshua B. Gaither, MD, of the University of Arizona Medical Center, on the mass shoot-

ing near Tucson involving Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords (D-Ariz.)

Gaither pointed out that the Pima County Sheriff’s Department deputies who were in the initial hot zone arresting the would-be assassin and ensuring scene safety, used the recently updated EMS training and small specialized law enforcement Individual First Aid Kits (IFAKs) to treat 14 of the 19 surviving victims.

In the early stages of this incident, the depu-ties retrieved their IFAKs, carried conveniently behind the front headrest of their police cruis-ers, and used tourniquets and hemostatic clot-ting agents to control significant bleeding and prevent the onset of shock. They also used chest seals to seal open wounds and combat tension pneumothorax.

It was a subtle statement that begged for more explanation. So I contacted David Kleinman, a detective with the Arizona Department of Public Safety and a tactical

paramedic with Pima Regional SWAT. I learned that Kleinman had developed a spe-cialized training program, called The First Five Minutes, which was adopted by the Pima County Sheriff’s Department.

That training, plus the up-to-date medical supplies they carried in each patrol vehicle, allowed the Pima County deputies to have a major effect on the survival of many of the victims at the Safeway shooting scene. The content involved the most up-to-date treat-ment and supplies for hemorrhage control and shock abatement.

Military research on the care rendered to crit-ically injured soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan

has shown that if you combat and control hemorrhage before the onset of shock, mortality decreases significantly.1 So this training for law enforcement officers was not just up-to-date, but it was also timely.

I asked David to write an article for this month’s JEMS that detailed the training and how it was used effectively to keep many of the critically injured victims alive on Jan. 8, 2011. We found that several other innovative law enforcement initiatives were implemented in 2011 to train and equip officers to save themselves when injured, save their colleagues and save citizens during natural or man-made disasters and mass casualty incidents. It was clear to us that this new wave of updated train-ing was significant and worthy of our atten-tion, and yours.

The strong message for fire and EMS agen-cies is that law officers are often on the front lines long before fire and EMS units arrive. Please follow this educational trend, work to have updated training provided to the law offi-cers in your service area, and “arm” each officer with the essential equipment they need to save their lives and others.

The contents I believe each patrol officer should carry in a compact gear pouch include: >> 4"compressiondressing; >> Hemostaticclottingagentdressing; >> Tacticaltourniquet; >> Chestseal; >> 3x3x2(gauzesponges); >> 4-1/2"Kerlixsterilerollbandages; >> 1"Transporesurgicaltape; >> Traumashears; >> Ventilationmask; >> ThreepairofNitrilegloves;and >> SAMSplint

The cost per kit is less than $100—but it’s a small investment to save an officer or civilian when time is critical. JEMS

RefeRences1. KraghJ,LittrellM,JonesJ,etal.Battlecasualtysurvival

withemergencytourniquetusetostoplimbbleeding.JEmergMed.2011;41(6):590–597.

fRom the editoRputting issues into perspective

>> by A.J. HeigHtMAn, MpA, eMt-p

16JEMS MAY 2012

Go to www.youtube.com/watch?v=lBGfKtuo2Am

Contents of the Pima County Sheriff’s Dept IFAK.

On the FrOnt LIneS Updatingthetraining&carecapabilitiesoflawofficers

pHo

to M

Att

Hew

str

Au

ss

016_Editor.indd 16 4/20/2012 11:57:48 AM

LETTERSin your words

18 JEMS MAY 2012

SELf DEfEnSEI definitely think we should be prepared for any harmful situation. I was involved in a situation that went bad fast. I was assaulted by a patient who was on numerous illegal drugs. Initially, he presented with hypoglycemic symptoms, but after loading him into the unit, he began to exhibit signs of paranoia and hallucinations. Luckily, the police department was on scene, but unfortunately he had a chance to grab me.

It took the fast thinking of the officer to physically make him release his hold on me, and for my partner to administer Versed, which did absolutely nothing, to get me freed. It happened so fast, so I agree that it would have been helpful if I’d known some self defense. That way, I would have known how to break the death grip he had on me when he wrapped his legs around me, with-out injuring him. He not only physically harmed me, but he also made me lose the trust I had prior to that day.

Misty BortzVia Facebook

Like I was taught, I don’t plan to fight; I plan to end it. And I’m not referring to irrational, overdose or dementia patients. I’m referring to the rational patients who might turn on us one day. Everyone is always happy to see EMS. Cops are always immediately on hand and helpful, and happy endings are guaranteed, right? The truth is, you never know when something might happen. I believe in doing no harm first and foremost. I also believe in com-ing home safe and in one piece after every shift.

Heather Gaff MewisVia Facebook

While I was responding to a code orange (a suicidal psych patient), who had just been struck by a vehicle in an attempt to take his life after assaulting his mother in her home, police and sheriff were on scene as my unit arrived. I’ve done mixed martial arts for a few years, and when three law enforcement officers and one of my two partners couldn’t restrain the patient, I fell back on

my own training to ensure scene safety by doing what the rest on scene couldn’t.

I wrapped the patient up in a Brazilian Ju Jitsu hold. Once I had him fully restrained, the officers assisted in putting restraints on the man while they systematically strapped both me and the patient to the backboard. After we were both strapped in and he was much better restrained, they loosened one strap at a time, so I could slip my limbs out and prepare the patient for transport. If a patient’s aggression causes this kind of situation, knowing how to defend yourself is literally a lifesaver.

Joe LeeVia Facebook

AmiSh PERSPEcTivEAs a former EMT with Lancaster EMS as well as Strasburg EMS, I’ve worked with several of the Amish EMTs, and I must say they’re very dedicated and caring for the entire community—not just their own people. The area that they cover is a large tourist area, and they work well

with people from all over the country and from all walks of life.

However, treating the Amish themselves can be a real challenge. I ran on a call for a child with a trau-matic injury after being kicked by a horse. My partner and I wanted to fly the child to a nearby hospital, but the family said ‘no helicopter; just take the patient to the hospital and let God decide the outcome.’ As a healthcare provider, sometimes they do tie your hands as far as treatment and transport go.

James AdamsVia Facebook

I work in northeast Indiana, and we have a large Amish population. We have a very good relationship with them, perform occasional safety days for them and have several medics who travel to Amish schools with an ambulance to interact with the kids. We have several EMTs and medics who grew up Amish, which is helpful for speaking with the young kids who don’t speak English. As mentioned, there are sometimes differences in opinions, as far as flying patients (they strongly prefer not to use the helicopter), and they definitely don’t call unless things are very serious. The one thing you can always count on, with the Amish, though, is that they’re very grateful for our help and are supportive of what we do. JEMS

Julie ShoemakerVia Facebook

Do you have questions, comments or concerns about recent JEMS or JEMS.com articles? We’d love to hear from you. E-mail your letters to editor.jems@

elsevier.com or send to 525 B St. Suite 1800, San Diego, CA 92101, Attn: Allison Moen.

This month, Facebook users chime in on “EMS Providers Should Train like Fighters,” a JEMS.com article by fitness col-umnist John Amtmann, EdD, on why it’s important for EMS pro-viders to train for the worst-case scenario. Would you be prepared to defend yourself? Also, users share feedback on a March JEMS article by Bryan Bledsoe, DO,

FACEP, FAAEM, on EMS in the Pennsylvania Amish community (“Simple Way of Life: EMS in Amish country”).

Pho

to is

toc

kPh

oto

.co

m

illu

stra

tio

n s

tev

e be

rry

Due to graphic content,rubbernecking

discretion is advised.

018_Letters.indd 18 4/20/2012 11:58:45 AM

Speaker: Rob Lawrence

Sponsored by:

With content from writers who are EMS professionals in the field, JEMS provides the information you need on clinical issues, products and trends.

Available in print or digital editions!

Giving you the detailed product information you need, when you need it. We collect all the information from manufacturers and put it in one place, so it’s easy for you to find and easy for you to read. Go to www.jems.com/ems-products

Your online connection to the EMS world, jems.com gives you information on:

• Products• Jobs• Patient Care• Training• Technology

Sign up now for the weekly JEMS.com eNewsletter. Get breaking news, articles and product information sent right to your computer. Read it on your time and stay ahead of the latest news!

jems.com eNewsletter Product Connect

jems.com Websitejems, journal of emergency medical services

Watch live or in the

archives!

Go to www.jems.com

Comprehensive, Credible, Educational...

JEMS Products Help You Save Lives.

n ems strategies for Improving Cardiac Arrest survival may 21 2012, at 1 p.m. eT/10 a.m. PT n Drug shortage Action Plans for emsn Are You Bagging the Life Out of Your Patients?n statewide Trauma system enables multi-Agency Coordination with Trauma Centers to Improve Patient Outcomes

4 NeW WeBCAsTs! Register at jems.com/webcasts.

Sponsored by:

Sponsored by:

Sponsored by:

JEMS FOP May2012 FP.indd 1 4/16/2012 1:42:43 PM

L ook out, Washington, here comes EMS. Paramedics and EMTs from across the coun-

try went to the hill for the third time to talk to members of Congress about what’s important to the EMS community and its patients.

There’s only so much that can be done on the local and state lev-els. Federal funding and guidance is needed in some areas. And that’s why we saw the third EMS on the Hill Day, hosted by the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians (NAEMT).

Legislators have to hear from their constituents if there’s any chance of them understand-ing what’s going on outside of Washington. EMS providers go to talk to their representatives and sen-ators about what they see as a non-partisan issue: providing quality care to their patients.

NAEMT President Connie Meyer, EMT-P, EMS captain for Johnson County Med-Act in Olathe, Kan., was excited about this year’s EMS on the Hill Day. She says they expected 190–200 EMS personnel to attend—up from 145 in 2011. Something new this year was a partnership with the American Ambulance Association (AAA). AAA participation replaced their regular lobby day.

EMS on the Hill Day attendees were invited to participate in AAA’s Reimbursement Task Force meeting on Tuesday afternoon, March 20, for discussions on reimbursement issues, healthcare reform, Medicare ambulance relief and other emergent topics.

Tuesday evening included a pre-visit brief-ing with the opportunity for attendees to mingle and see old friends or network with new contacts.

Wednesday morning, the visits to Congressional offices began. Armed with their talking points (more on that below), EMS professionals met with their representa-

tives and senators or staffs. The meetings not only gave EMS personnel the chance to speak of legislature issues that touch them profes-sionally and personally, but they also allowed the legislators the opportunity to learn more about EMS. During a previous visit, one staffer asked, “So you’re not a fire man?”

And the knowledge exchange has already led to an event that Meyer characterized as “huge.” What she’s referring to is a request from a federal legislator for NAEMT input on a bill being written. An elected official in Washington came to NAEMT for advice.

While visiting the Congressional offices, attendees have talking points, supplied by NAEMT. This year’s issues include the fol-lowing talking points:

>> The Medicare Ambulance Access Preservation Act of 2011 to provide for a more permanent solution to below-cost Medicare ambulance reimbursement;

>> The extension of death and other ben-efits under the Public Safety Officers’ Benefits (PSOB) program to non-profit, nongovernmental paramedics and EMTs who die or are severely injured in

the line of duty; and>> The legislation to establish new

EMS grant programs; enhance research initiatives; and promote high-quality, innovative and cost-effective field EMS.

To assist active members in attend-ing EMS on the Hill Day, NAEMT awarded grants of up to $1,200 each to four active members.

One of the grant recipients was Jason Scheiderer, EMT-P, of Indianapolis, Ind. He’s employed by Indianapolis EMS and teaches paramedic courses at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. Scheiderer has advo-cated for local issues, walking the fine line between concerned taxpayer and public employee. NAEMT’s state advocacy coordinator for Indiana, Scheiderer appreciates NAEMT’s focus

on improving EMS on a grand scale. “Not getting into local issues like fire department vs. private EMS providers,” he says.

W. Mike McMichael III, EMT-B, and 2011 NAEMT grant recipient from Delaware, returns to Washington for the 2012 event. McMichael says, “I’m tickled to death to be involved” in this endeavor that “will help everyone in the country.” Although he personally knows his representative and Delaware’s two senators, he liked the oppor-tunity to see them working.

On May 4, 2011, in Washington, D.C., 145 EMS professionals from 39 states and the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico met with more than 217 U.S. Senators, House Representatives and their congressional staff at the second annual EMS on the Hill Day.

The fourth EMS on the Hill Day is tenta-tively scheduled for the first week in March 2013. That would coincide with 2013 EMS Today, so you could attend both on one plane ticket.

Mark your calendar and watch the NAEMT site for more details in the months to come.

—Ann-Marie Lindstrom

PRIORITY TRAFFICNEWS YOU CAN USE

20 JEMS MAY 2012

NAEMT hosts third-annual event EMS on the HILL

For more of the latest EMS news, visit jems.com/news

phO

tO d

rEA

mSt

imE.

CO

m

020_022_Ptraffic.indd 20 4/17/2012 10:15:26 AM

www.jems.com mAY 2012 JEMS 21

Mardi Gras No Party for EMs

New Orleans EMS responded to more than 2,000 calls during a 10-day

period in February. That’s 67 more than

their normal activity. Despite

all the strange weather across the

country this winter, the increased call volume in New Orleans wasn’t because of hurricanes or other natural disasters.

It was Mardi Gras—definitely a man-made, and perhaps unnatu-ral, event. Weeks of reveling take their toll on the thousands of residents and tourists who show up for the 60 Krewe parades and other celebrations.

Deputy Chief of EMS Ken Bouvier says, “Obviously, there’s a lot of alcohol poisoning.” Perhaps, not unrelated, there are also falls from ladders and balconies in the French Quarter.

Bouvier says their transportation fleet included 25 ambulances, six Fast Cars, an ASAP mini-ambulance, two bicycles and an 18-stretcher mobile ambulance bus.

The parade route is approximately 60 city blocks, according to Bouvier. “We try not to cross parades, so we have staff on both sides of the streets.”

The Red Cross saw about 1,000 patients in its four first aid tents. The tents were staffed with six to eight volunteers ready to treat such minor complaints as sprains, foreign objects in the eye or requests for a Band-Aid. Red Cross first responders also wandered through the crowds keeping an eye open for anyone in need of medical assistance. Armed with radios, the first responders called EMS as needed.

Bouvier characterized this year’s Mardi Gras as “well attended” without violence along the parade route—evidently that’s notewor-thy when you talk about Mardi Gras.

PlaNNiNGPlanning is paramount for a city-wide, three-week celebration. Bouvier says they start planning for the next year about a week after Mardi Gras ends. They look at the statistics and reports to see what worked and what could be improved. For example, the city made more use of the Red Cross this year, “because it works,” says Bouvier. The mini ambulance and bike teams are new additions, too.

As Mardi Gras draws near, New Orleans EMS has to make sure it has enough medications on hand, enough staff ready to work—for-get about ever getting time off to enjoy the festivities with your family or friends—and enough ambulances ready to roll.

Next year’s Mardi Gras will be an enhanced challenge, says Bouvier. New Orleans hosts Super Bowl XLVII on February 3, 2013, so the city has decided to split up the Mardi Gras events to bookend the Super Bowl. That is, there will be a week of Mardi Gras celebra-tion, a week devoted to Super Bowl activities and then another week of Mardi Gras.

Bouvier says they will be ready. And they’ll all probably be ready for a long vacation in March. —Ann-Marie Lindstrom

pho

to d

rea

mst

ime.

co

m

Choose 20 at www.jems.com/rs

020_022_Ptraffic.indd 21 4/17/2012 10:17:58 AM

22 JEMS MAY 2012

>> continued from page 21

Check out all the upcoming free webcasts JEMS has to offer: www.jems.com/webcasts

2012 NatioNal EMS MEMorial BikE ridEThe National EMS Memorial Bike Ride (NEMSMBR) is gearing up for the 2012 Ride, with routes beginning in Boston, Mass., or Paintsville, Ky., on May 19—both finishing in Alexandria, Va., on May 25.

During the ride, participants will travel through the states of Massachusetts, Kentucky, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia.

“To see these parts of the United States on a bicycle is such a unique perspective,” says Tim Perkins, NEMSMBR public information officer.

“It’s also great to interact with the pro-viders and agencies along the route, not to mention the reason for the ride: honoring over 30 individuals who have given the ultimate sac-rifice providing EMS care,” says Perkins.

Additional rides are scheduled for Colorado in June and Louisiana in September.

QUiCk taKe

For more information about the bike ride,

visit www.muddyangels.com.

T he healthcare industry has come a long way since Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) went into effect almost a decade ago. For the most part, EMS providers now have a much bet-

ter understanding of how HIPAA applies to their day-to-day operations. Nevertheless, many “HIPAA myths” still exist. Here are some of the top myths in the EMS industry today.

>> MyTh: hIPAA prevents EMS agencies and facilities from sharing patient information.

All healthcare providers should know that HIPAA permits them to freely share patient information for treatment-related purposes. That means that facilities can give EMS providers medical records about patients, and crews can look at those records for treatment purposes. It doesn’t matter that another provider created the medical record.

Ambulance services may also provide a copy of their trip reports to facilities because such practice would also fall under the “treatment” umbrella. Under HIPAA, “treatment” includes the provision, coordination and management of healthcare between providers.

>> MyTh: Law enforcement offi-cers are automatically enti-tled to patient information.

Many EMS providers believe that if a law enforcement official asks for information about a patient, they’re automatically entitled to it. Although there are circumstances under which ambulance services may release patient informa-tion to law enforcement, there’s no general provi-sion in HIPAA that broadly permits providers to release patient information to law enforcement. To the contrary, providers can only give patient information to law enforcement officials under specific circumstances.

If an ambulance service receives a request for healthcare information from law enforcement, the service must check to see whether HIPAA contains a specific exception that permits the release of the information. Some of the more common exceptions include reporting a crime in an emergency or disclosures that are required by state law (e.g., gunshot wounds and dog bites). Check with your HIPAA privacy officer before you release information to law enforcement. If you improperly disclose information, you risk violating HIPAA, and that information might not be allowed to be introduced as evidence because it was improperly obtained.

>> MyTh: It’s OK to post as long as the patient isn’t identified.EMS providers have a legal and ethical duty to refrain from posting any “protected health information”

(PHI) on the Internet. Most of us know that PHI is anything that could directly identify a patient. However, what many fail to consider is that some information might reasonably identify a patient, even though it doesn’t mention a patient by name. The bottom line is that if someone reading the post might be able to figure out who the patient is, the information might be PHI, and posting it could violate HIPAA.

For example, a post stating, “Was on a pretty crazy trauma on I-95 tonight … that guy had no shot,” might convey enough information to enable friends or family members of the deceased patient to identify him because they undoubtedly know about the incident.

Because others can determine the identity of the patient from the limited information provided, this post improperly divulges PHI. Generally, no legitimate reasons justify posting any information about a patient on the Internet. Moreover, it’s unethical—and unprofessional—to refer to a patient, in any manner, on the Internet.

DEbunKIng HIPAA MytHs

Pro Bono is written by attorneys Doug Wolfberg, Ryan Stark and Steve Wirth of Page, Wolfberg & Wirth LLC, a national EMS-industry law firm. Visit the firm’s website at www.pwwemslaw.com for more EMS law information.

pho

to d

rea

mst

ime.

co

mEMS providers travel across the country for the national EMS Memorial bike Ride.

pho

to c

ou

rtes

y n

emsm

Br

020_022_Ptraffic.indd 22 4/20/2012 11:59:37 AM

LEADERSHIP SECTORpresented by the iafc ems section

>> by gary ludwig, ms, emt-p

24 JEMS may 2012

We’re familiar with the usual type of leadership that a manager at IBM, Bank of America or the cor-

ner grocery store shows when managing their operation and people. Usually these manag-ers mistakenly try to manage people when they should be leading people. The impor-tant thing to remember is that we manage things and we lead people. We manage budgets, inventory and fleets.

It’s rare that the manager working at IBM, Bank of America or the corner grocery store need to lead people in a crisis. That isn’t true for the EMS manager. Not only do they have to lead people under normal everyday con-ditions, but they also may be asked to show their leadership during high-intensity events, such as tornadoes or mass-casualty incidents. EMS managers may be thrust into a leader-ship role during an active shooter attack.

The leadership skills that an EMS manager must exhibit during a crisis are much differ-ent from the leadership skills that they use in their day-to-day operations. In their day-to-day office operations, they have the abil-ity to sit back and use discretionary time to make a decision. If someone comes into their office with a problem, the EMS manager has the luxury of requesting more information, maybe making some phone calls, sitting on it overnight or even checking with their boss before they make a decision.

Unfortunately, that isn’t the case on the scene of an active shooter or a bus crash. Sometimes split-second decisions must to be made. Sometimes decisions have to be made with limited information. And sometimes the EMS manager may have to make some tough decisions that have a direct affect on someone’s life. The leadership skills that an EMS manager must show during these criti-cal times are crucial.

LEADERSHIP TIPSIn my opinion, one of the finest examples of leadership was former New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s management of

9/11. Don’t forget, the U.S. president was sheltered away until late in the evening to protect the head of our federal government. President Bush wasn’t seen on television; it was Giuliani who became the face of reassur-ance on television for the American people. But 9/11 wasn’t the only time Giuliani was thrust into a crisis. He routinely showed up at emergency scenes in New York City.

Giuliani describes four steps for crisis lead-ership in his book Leadership. “It is in times of crisis that good leaders emerge,” he says.

He says the first step is to be visible. Giuliani says, “While mayor, I made it my policy to see with my own eyes the scene of every crisis so I could evaluate it firsthand.”1

Who can forget those scenes of Mayor Giuliani walking on the streets of New York with his contingent of staff and department heads while being interviewed by the news media? EMS managers must respond to scenes and take charge of their operation. Many times, they fall into the incident man-agement structure. Although they may not have overall command of an event, EMS managers are still responsible for the medical operations branch.

Giuliani’s second step is to be com-posed. He writes in his book, “Leaders have to control their emotions under

pressure. Much of your ability to get people to do what they have to do is going to depend on what they perceive when they look at you and listen to you. They need to see someone who is stronger than they are, but human, too.”

Many times in my career I’ve seen an inci-dent commander yell or even scream into a radio. Yelling on the radio or at employees on a scene, or giving an appearance of being out of control, is a prescription for crisis—the situation EMS managers are trying to control.

Giuliani’s third step is to be vocal. He writes, “I had to communicate with the public to do whatever I could to calm people down and contribute to an orderly and safe evacua-tion [of lower Manhattan].”

EMS managers must demonstrate the same trait during a high-intensity event. You need to be able to give people firm directions and instructions. You need to give your employees or others clear and concise instructions or action steps.

Giuliani’s fourth step to crisis leadership is to be resilient. Giuliani describes himself as an optimist. With his words during some of his press conferences about 9/11, he gave Americans hope that they would meet this challenge and overcome it.

EMS managers must also show the same resiliency. They demonstrate through actions and words that whatever the challenge that the EMS organization and its employees are facing, they’ll be able to deal with it.

And, most importantly, always remember there are times to demonstrate everyday lead-ership and times during emergencies that you have to demonstrate true leadership skills. JEMS

REfEREnCES1. Giuliani R: Leadership. Hyperion: New York, 2002.

Gary Ludwig, MS, EMT-P, is a deputy fire chief

with the Memphis (Tenn.) Fire Department.

He has 34 years of fire and rescue experi-

ence. He’s chair of the EMS Section for the

International Association of Fire Chiefs and

can be reached at www.garyludwig.com.

Crisis ManaGeMentRudy Giuliani advocates for managing things, not people

‘It is in times of crisis that good leaders emerge.’

024_Leadership.indd 24 4/17/2012 10:18:35 AM

Choose 22 at www.jems.com/rs

FP_RT.indd 1 4/16/2012 4:07:25 PM

FP_LFT.indd 1 4/16/2012 11:39:07 AM

If a call for a mass casualty incident (MCI) goes out in northern New Jersey, there’s

a good chance James Pruden, MD, the med-ical director for emergency preparedness at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center, is going for a ride.

Pruden is part of a breed of physicians who are just as comfortable working outside of the confines of an emergency department (ED) as they are in the field—where they can be more helpful controlling a scene.

“There’s a subset of physicians, wild and crazy guys, who get that surge and pleasure being out there in the environment,” says Pruden, who heads up St. Joseph’s Emer-gency Physician Response Vehicle pro-gram, MD-2.

The St. Joseph’s program, which is part of the New Jersey EMS Task Force system, is used to respond to everything from school bus rollovers, to fires and planned events throughout the region.

The parameters for the units being dis-patched are wide open, but the common thread is that the doctors responding are dif-ferent from their hospital-bound brethren.

“It’s not just about having an emer-gency physician,” says Scott Matin, vice president of Mobile Health Services at the Monmouth Ocean Hospital Services Cor-poration (MONOC), which also launched mobile physician unit MD-1 in January.

MONOC’s MD-1 unit is headed by Mark Merlin, MD, a new member of MONOC’s Medical Advisory Board, chair of the EMS/Disaster Medicine Fellowship at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center and medical director of the New Jersey EMS Task Force. MD-1 is stationed with Merlin or a member of his team.

“It’s about having someone with emer-gency experience. It is different doing something in the emergency room than it is having to do it in the field. You’re not on

a table, but in the back of [a] crashed upside down vehicle,” says Matin.

And that’s where the mobile physicians’ units come into play, especially at times when there may be an MCI or some other incident in which the scene could use a physician on hand.

In some ways, the MD units are a “force multiplier,” says Robert J. Bertollo, MICP, LRCP, MBA, the program man-ager of Life Support Education and Emer-gency Response Operations for St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center.

St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center has operated an MD unit for two years that was funded through the Urban Areas Security Initiative. Pruden recalls a scenario a few years ago—before MD-2 existed—during which employees at a local factory were overcome by a chemical odor that trav-eled through the building. There were hun-dreds of potential patients involved, and 50

www.jems.com mAY 2012 JEMS 27

EmErgEncy physicians assist thEir prEhospital countErparts >> By RichaRd huff, NREMT-B

ManageMent Focus

The medical director units that arrive on-scene with a physician are especially beneficial during mass casualty incidents.

pho

to is

toc

kph

oto

.co

m

027_029_ManagementFocus.indd 27 4/17/2012 10:19:09 AM

28 JEMS MAY 2012

ended up being transported to local EDs. “What you can do is send the physician to the site, where you then

have the ability to express people on the scene,” Pruden says. Triage and treatment protocols could have been decided on the

scene of the factory incident, he says, altering the volume of patients sent to local hospitals.

MD Units UseThere has been an increase in the use of MD units in the field around the country in recent years. For example, besides the units in New Jersey and Erie County, New York, has a Specialized Medical Assis-tance Response Team, which is a volunteer public health emergency response organization that makes physician response available around the clock.

For the most part, the MD units are similar. They’re staffed by physicians like Pruden, who enjoy the challenge of working at an emergency scene. Typically, the medical teams operate out of non-transport-type sports utility vehicles that mimic paramedic vehi-cles—although without the required depth of supplies. Some units include equipment for on-scene surgical procedures.

The initial concept for MD vehicles in EMS responses was for the more serious patient scenarios in which extrication may severely cut into the golden hour and reduce survivability. It’s safe to say,

however, the parameters for use are evolving. Although relatively new in New Jersey, the greatest use so far has been for MCIs and pre-planned events, such as major festival concerts for which a high range of injury is likely.

“Its real worth is when there’s a physician on scene and in a med-ical control capability,” says Bertollo. In those cases, the specially trained doctors can increase the volume of patients handled on scene by taking medical control.

“When it gets to the point where you need that, a doctor can make multiple decisions,” Bertollo says.

“If you are at the scene, you can identify and quickly establish symptom protocols,” Pruden adds.

The Monmouth Ocean Hospital Service Corporation unit wouldn’t respond to the typical EMS call, but rather come into play for cases in which someone is trapped for an extended amount of time, or when there might be a need for an emergency amputation to free the patient.

“These are going to be ones where a half-hour response time still means you’re going to make it to the scene,” Matin says.

ProtocolAt St. Joseph’s, the response parameters for the MD unit have been pretty broad, Bertollo says, and often left to an on-scene agency to request the team. When the program was launched, he explains, the folks at St. Joseph’s visited regional EMS providers to familiarize them with the operation.

extra set of HanDs >> continued from page 27

In some ways, the MD units are a ‘force multiplier.’

choose 23 at www.jems.com/rs

027_029_ManagementFocus.indd 28 4/20/2012 3:03:59 PM

www.jems.com mAY 2012 JEMS 29

“You need a physician because you’ve transcended the ability of the EMTs or paramedics on scene,” he says. “We’ve had multiple patients at fire scenes, industrial accidents ... and we’ve certainly dis-patched during floods,” he adds. “Also, if there are specialty things, like a shooting or multiple-patient pediatric calls.”

There will be more use of the unit in mass casualty situations than a physician strapping on a surgical kit to do an on-scene ampu-tation or blood transfusion, says Bertollo. The dispatch operation serving St. Joseph’s has put a system into place: When something on scene seems unusual, a call goes out to the five physicians on the MD-2 team.

“Basically, what we’ve said is if you get into a circumstance where you find something unique or strange looking and the medics say, ‘we wish we had a doc out here,’ give us a call,” Pruden says.

Doing so, of course, gives the physicians in the program real-time exposure with the frontline emergency responders they normally wouldn’t see with any regularity, making everyone more comfort-able in future scenarios. Likewise, it also gives the physicians experi-ence in situations that are dissimilar from routine ED settings.

And it also expands the program beyond simply preparing EMS providers to respond to “the big one,” adds Pruden.

There are benefits to the mobile physician teams beyond responses, too. The folks at MONOC expect to use Merlin and his team in educational situations and drills.

“What’s nice about this program is, we hope in the end there is not a lot a huge need for it,” Matin says. “There are added benefits being involved with this program. We do a tremendous amount of educa-tion. Having that number of physicians at hand is a fantastic thing.”

EMS IntEractIonHaving a higher medical authority on the scene of an EMS call does raise the potential for conflicts between providers. Matin says he understands there could be concerns about how EMS provid-ers react in the field to the arrival of a physician on the scene, but it shouldn’t be a problem in this case.

“These doctors are going to be coming out on special scenes,” he says. “I can tell you the medics will be glad they’re there.”

Bertollo agrees, “They’ve integrated well. The physicians that have staffed those responses have known from the outset they’ve wanted to be an integrated player. We’re here to augment and lend support.”

Pruden goes a step further, noting the goals of the MD-2 unit are similar to why he loves disaster responses.

“It’s the unity of purpose,” he says. “In an event, when you’re responding to some critical event, you and other human beings have the same goal, to help people, to get a response, to turn this thing into the most positive outcome you can make. Frequently, those events suppressed ulterior motives. It’s amazing to work in an envi-ronment where everybody has the same goal. It’s an incredible rush to be engaged with that kind of mindset where people are working together.” JEMS

Richard Huff, NREMT-B, is an active member and the former chief of the Atlantic

Highlands (N.J.) First Aid & Safety Squad. He’s a CPR, CEVO and first aid instructor and

multi-dimensional EMS educator. He’s also an award-winning journalist and author.

choose 24 at www.jems.com/rs

027_029_ManagementFocus.indd 29 4/17/2012 10:28:19 AM

TRICKS OF THE TRADEcaring for our patients & ourselves

>> by thom Dick, emt-p

30 JEMS MAY 2012

I don’t think you can quantify everything that’s important in life. But in all of the science on which emergency medicine

has come to depend, we never seem to give up trying.

Think for a moment. We use a numeric score to rate people’s pain. (I don’t think it tells us a dang thing.) We use endless scales to measure the concentration of ions in their body fluids, the physical pressure of the blood in their vascular systems, the color of their urine, and their heart and respira-tory rates. We use scales to assess the sizes of their pupils and describe the shapes of their upper airways. We use a trauma score to predict their survival after they get hurt, and another scale to describe the severity of their burns. We imprint depth scales on the tubes we insert in their orifices. We even use numeric gradients during our runs to express the urgency of our responses to their emergencies.

We frame our lives in the same way, Life-Saver. A while back, my hometown’s pro football team (the Broncos) braced itself to take on the New England Patriots in a divi-sional championship game. The Broncos were no better than mediocre this year, but they had supposedly earned a shot at the Pats by beating the Steelers a week earlier, in the first few seconds of overtime. The media and the Bronco fans celebrated the win; although, few would have blamed the Steeler fans for believing they were robbed. The final score was 29–23.

In reality, there was only the barest margin of difference between the play of those two teams, and an objective observer would probably have awarded the win to Pittsburgh. In addition, the NFL’s history won’t reflect the fact that Pittsburgh’s great quarterback, Ben Roethlisberger, played the whole game on a painful, unstable ankle.

We seem obsessed with the numbers in our lives. We’ve developed maps to tell us the depths of the ocean, as well as its salin-ity, its temperature and how much water it

contains. We assess the effects of the wastes we pour into it by guessing how many living organisms disappear afterward. (No doubt some of us believe there are acceptable num-bers of those, too, even if we can’t possibly count them all.)

We’ve developed systems to help us enu-merate the stars, assess their color, bright-ness, size and mass, and measure how far they are from us (almost as though we still believe they revolve around us). We think we know the volume of the vast space they inhabit (even if it’s so great, we can’t compre-hend it). We’ve envisioned ourselves at the tippy-top of the hierarchy of all life, based on the complexity of our cognitive thought processes. Scholars have attempted since the fifth century to describe the value of nothing. (What a surprise: We’ve assigned a number to that, too.)

We even rate human intelligence using a numerical value. We call it IQ, for intel-ligence quotient. We discuss people in terms of their IQs, as well as their age, height, weight, body-mass index, annual income, and belt and neck sizes (as though their dimensions actually help us to understand anything about them).

The business of helping people in crisis is a lot bigger than the stuff we can measure. Measurements are simple routines, each of which typi-cally reveals no more than a single answer to a simple question. What’s the blood pressure? What’s the blood glu-

cose? What’s the pH?It’s important to respect what those

numbers tell us, but only as puzzle pieces. Whatever we do, we need to be much more focused instead on a prime number we call “one.”

Serving people is all about individuals. Taking care of them requires a willingness to admit that we don’t know much about them. But we have a persistent commitment to observe, question, examine and think. In emergency situations, we sometimes need to do all of those things at warp speed. (If anybody ever told you this EMS stuff would be easy, they altered the truth.)

Next time you kneel in front of somebody you don’t know or sit beside someone in that ambulance of yours, look them straight in the eye. No matter how ordinary they seem, how ugly or even unpleasant, ask for their name. And use it. And make sure there’s no doubt in their mind about one thing: While they’re with you, they’re important. What they say matters. And how they feel is essential. Not just any old person has the talent or the desire to do that. Those who do are called caregivers.

Are you one of those? If so, you really are special. JEMS

Thom Dick has been involved in EMS for

42 years, 23 of them as a full-time EMT and

paramedic in San Diego County. He’s currently

the quality care coordinator for Platte Valley

Ambulance, a hospital-based 9-1-1 system in

Brighton, Colo. Contact him at [email protected].

Numbers Reflections on the value of one

Our patients are much more than the numbers of their blood pressure reading or their pH level; they’re individuals.

pho

to is

toc

kph

oto

.co

m

030_Tricks.indd 30 4/17/2012 10:28:46 AM

Choose 26 at www.jems.com/rs

Choose 25 at www.jems.com/rs

pg31_RT.indd 1 4/20/2012 3:11:28 PM

CASE OF THE MONTHDILEMMAS IN DAY-TO-DAY CARE

>> BY JEff WESTIN, MD; PAT SONgER, NREMT-P, ASM; KELLY BuChANAN, MD; LOREN gOROSh, MD; RYAN hODNICK, DO; & BRYAN E. BLEDSOE, DO, fACEP, fAAEM

32 JEMS MAY 2012

Burning Man is a massive event held around every Labor Day in the Black Rock desert in northwestern Nevada.

The encampment is an official city called Black Rock City, and although it exists for only a week or so each year, it becomes the third-largest city in Nevada. The event attracts in excess of 50,000 attendees.

The purpose of Burning Man is radical self-expression in various art forms. It’s truly a one-of-a-kind event. Black Rock City operates as a functional geopolitical entity with fire, police and EMS systems. Each is dispatched from a manned com-munications center that’s constructed and deconstructed annually.

In 2011, Humboldt General Hospital EMS in Winnemucca was contracted to provide medical care for Burning Man. Medical care included a fully staffed and operational EMS system, as well as a field hospital called Rampart General and two BLS aid centers.

A total of 2,307 patients were treated. Three-hundred and eighty-two requests for ambulances were made, with 185 patients being transported to Rampart General. Only 33 patients were transported out of the desert for care. The following high-lights one of those cases that took place during the event.

REMOTE CAREOn the final day of the Burning Man event, EMS is summoned to a chest pain call in a trailer within the encampment. On arrival, paramedics find a 60-year-old male in acute distress.

He’s pale and diaphoretic and in extremis. The patient describes the pain as “tearing”

and can’t get into a comfortable position. The EMS crew extricates him from his trailer and moves him to the awaiting ambulance for a more detailed assessment.

He becomes unresponsive shortly after they place him in the ambulance. Paramedics check his pulse, take a quick look at the monitor, and note the patient is in a non-perfusing v tach. On a hunch, they administer a precordial thump, and it works. The patient converts to a sinus rhythm. He’s transported to Rampart General in Black Rock City.

Once the patient arrives at the field hos-pital, the emergency staff rapidly assesses him. He’s alert and oriented, but his blood pressure is undetectable. He’s writhing in pain on the stretcher. IV fluids are given, and his blood pressure is finally detectable at a systolic pressure of 72 mmHg and then

up to 76 mmHg. He remains mildly tachy-cardic. He receives IV fentanyl for pain. Rampart General has X-ray capabilities and a stat chest X-ray is obtained. The emer-gency physician notes that the mediasti-num is wide at 10.5 cm—consistent with a thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. A medical helicopter is summoned and the patient is closely monitored and stabilized by the emergency staff.

As soon as the helicopter arrives, the patient is moved to the aircraft and transported to a major medical center about 150 miles away. Once he arrives, he undergoes a computed tomography angio-gram (CTA) that confirms the suspected aortic dissection.

The patient is emergently taken to sur-gery where the aneurysm is repaired. The operation is successful, and the patient is

Miracle in the DesertCardiac case at remote Burning Man event presents challenges

>> a case froM university MeDical center in las veGas

PhO

TO C

Ou

RTES

Y B

RYA

N B

LED

SOE

Burning Man, an elaborate weeklong festival in the nevada desert, presents unique challenges to eMs providers.

032_035_Case.indd 32 4/17/2012 10:29:16 AM

www.jems.com mAY 2012 JEMS 33

moved to the intensive care unit (ICU).Following surgery, the patient suffers a second cardiac arrest

and is taken to the cardiac catheterization lab for evaluation and subsequent stenting of a coronary artery lesion. He’s returned to the ICU and remains stable. He’s discharged home with appropri-ate provisions for follow-up. Despite his ordeal, he’s already plan-ning his next trip to Burning Man.

DiscussionFirst, this is not a true “case from University Medical Center” because it didn’t happen at UMC. However, emergency physi-cians, emergency medicine residents and medical students from the University of Nevada School of Medicine provided much of the medical care at Burning Man. As you can tell, this patient had all the cards stacked against him. He had a critical thoracic aortic dissection, and he was in the middle of a Nevada desert more than 150 miles from a medical facility with cardiothoracic surgery capa-bilities. Furthermore, he suffered a cardiac arrest. Yet despite all of this, he survived.

Thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections are life-threatening conditions that affect the thoracic portions of the aorta. An aneurysm is a dilation of an artery greater than 50% of its nor-mal diameter. They’re classified based on the region of the aorta affected (e.g., ascending aortic, aortic arch, descending aortic and thoracoabdominal), and are at risk for rupture.

A dissection results from a tear in the interior lining of the aorta (the tunica intima). This tear, referred to as an intimal tear, causes the layers of the aortic wall to separate thus forming a false lumen. The pressure from the blood within the aorta causes the false lumen to expand, or dissect.

As the dissection progresses, blood flow to various blood ves-sels is affected, causing ischemia to the tissues they supply (e.g., the coronary arteries and spinal cord). Thoracic aneurysms most commonly occur in persons older than age 65. Death from a rup-tured aneurysm is typically one of the top 10–20 causes of death annually. The incidence of thoracic aneurysmal rupture is approxi-mately 3.5 per 100,000 persons.1

Patients who develop cardiac arrest from a thoracic aneurys-mal dissection rarely survive. Furthermore, resuscitation with a precordial thump is even less common.2 Hypotension is common, and hypertension should be avoided. This patient received enough fluids to restore perfusion as determined by monitoring his men-tal status and a maintaining a systolic blood pressure between 76–78 mmHg.

Consideration was given to adding vasopressors, but because dissection was suspected, they weren’t administered. A thoracic aortic dissection is characterized by widening of the mediastinum on chest X-ray. Fortunately, limited X-ray capabilities were avail-able at Rampart General. The diagnosis was later confirmed by a CTA at the receiving hospital.

Teaching PoinTsIt’s often difficult to diagnosis aortic dissection, either thoracic or abdominal, in the prehospital setting. Because of this, EMS provid-ers must have a high index of suspicion when patients present with signs and symptoms consistent with thoracic aortic dissection. The most common presenting sign is pain—either in the chest or

choose 27 at www.jems.com/rs

032_035_Case.indd 33 4/17/2012 10:33:45 AM

www.jems.com mAY 2012 JEMS 35

between the scapulae in the upper back. With large aneurysms, the superior vena cava can be compressed, causing distended neck veins. A murmur may be heard. Sometimes hoarseness, cough and wheezing may be present. In other instances, such as this one, shock and cardiac arrest may be present.

So much of quality EMS is identifying injuries and illness in the field, recognizing the potential severity and ensuring the patient is rapidly transported to an appropriate medical facility.

The concerns of EMS crews and a presumptive field diagno-sis can also aid emergency department personnel in directing appropriate resources to critically ill or injured patients. Quality emergency physicians will listen to the concerns of field crews and react accordingly.

SummaryThis was a miraculous case that illustrates the importance of seam-less interaction between field EMS crews and physicians. First, this case occurred in one of the most austere and hostile environ-ments imaginable. Next, it included a patient who was resuscitated from pulseless v tach with a precordial thump performed by a paramedic crew. The patient was subsequently evaluated and diagnosed with a thoracic aorta dissection by medical staff in a tent (with a diagnosis made by plain chest X-ray) and emergently transported 150 miles to a hospital where successful surgery was carried out.

It truly was a “perfect storm,” or perhaps, it was the general goodwill and spirit of Burning Man. Or maybe those crystals that were everywhere actually worked. JEMS

Jeff Westin, MD, was a third-year emergency medicine resident at the University

of Nevada School of Medicine. He’s an attending emergency physician for Kaiser-

Permanente in Portland, Ore. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Pat Songer, NREMT-P, ASM, is director of EMS at Humboldt General Hospital

EMS. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Kelly Buchanan, MD, is an EMS fellow at the University of Nevada School of

Medicine. She can be contacted at [email protected].

Loren Gorosh, MD, is a third-year emergency medicine resident

at the University of Nevada School of Medicine. He can be contacted at

Ryan Hodnick, DO, is a second-year emergency medicine resident

at the University of Nevada School of Medicine. He can be contacted at

Bryan Bledsoe, DO, FACEP, FAAEM, is professor of emergency medicine at

the University of Nevada School of Medicine and director of the EMS Fellowship

Program. He is also the medical director for Burning Man. He can be contacted at

referenceS1. Rogers RL, McCormack R. Aortic disasters. Emerg Med Clin North Am.

2004;22(4):887–908.2. Haman L, Parizek P, Vojacek J. Precordial thump efficacy in termination of

inducedventriculararrhythmias.Resuscitation.2009;80(1):14–16.

>> continued from page 33

caSe Of THe mOnTH

choose 29 at www.jems.com/rs

032_035_Case.indd 35 4/17/2012 10:34:00 AM

Aguilar SA, Patel M, Castillo E, et al. Gender differences

in scene time, transport time, and total scene to hospi-

tal arrival time determined by the use of a prehospital

electrocardiogram in patients with complaint of chest

pain. J Emerg Med. 2012; Feb 15. [Epub ahead of print].

These authors retrospectively analyzed San Diego EMS charts, measuring the

effect of prehospital 12-lead ECGs on scene times. Out of 21,742 chest pain calls, no sig-nificant scene time increases or differences were found between patients with and without ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). This is nothing new; this has been studied many times. The researchers did, however, find that in STEMI cases, male patients had an average of 17-minute scene times vs. females, who had 20-minute scene times. This delay is then projected to a pos-sible increase of 0.25–1.6% greater mortality.

This study adds to a growing body of literature showing that women experiencing acute coronary syndromes receive delayed diagnosis and care. Possible explanations could include atypical presentations, delayed symptoms or comorbidities. I’ll add my own observation that performing prehospital 12-leads on women involves a certain need for tact and social privacy that may cause a delay. In any case, now that we are aware of it … let’s all try to speed up identification and care for women having STEMIs.

Waldron R, Finalle C, Tsang J, et al. Effect of gender on prehospital refusal of medical aid. J Emerg Med. 2012; Feb 9. [Epub ahead of print].

It shouldn’t be any news that patient refusals often end in adverse outcomes and con-

tinue to be a problem for EMS. I applaud these authors for discovering a new angle to this issue. This New York City project retrospectively reviewed one year’s worth of patient-care reports for a single hospital-based ambulance service. The staff at this service is made up of 82 EMTs and paramed-ics, with 67 men (82%) and 15 women (18%).

Out of 19,455 total patient encounters, 238 refusals were documented. (If this is accurate, congratulations are due on a 1.2% refusal rate. This is one of the lowest ever reported in recent literature).

Although most of the refusals came dur-ing the evening tour, no correlation was found to it being in the beginning or near the end of the crew’s shift. The authors did, however, discover that crews composed of two male providers were four times more likely to have an encounter end in a refusal when compared to a crew that had one or both female crew members.

In the discussion, the authors note that differences in communication styles between genders may lead to perceptions of behaviors demonstrating greater care by female healthcare providers.

I TreaTmenT of seIzures ISilbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, et al.

Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospi-

tal status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):591–600.

The much anticipated results from the Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior

to Arrival Trial (RAMPART) study were published in February in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study’s main objective was to show that prehospital intramuscular (IM) midazolam (10 mg) was just as good as the in-hospital standard of care: IV loraz-epam (4 mg) for status epilepticus.

Because lorazepam has a short shelf life when it’s stored un-refrigerated, most EMS systems find it costly and impractical to

carry. Midazolam is widely used, but it hasn’t been studied well in the prehospital environment. This landmark prehospital study will likely be remembered more for its rigorous scientific methods rather than for the actual results. It’s a great example of the “gold standard” of research: double-blinded, prospective, randomized studies with great follow through to hospital discharge. The authors used some innovative and ground-breaking strategies to overcome the usual hurdles that make prehospital research so difficult.

First, the details: RAMPART involved 4,314 paramedics from 33 EMS agencies and 79 receiving hospitals across the U.S. They enrolled 893 patients and randomly assigned them to either the midazolam or the lorazepam group. Neither the patient, the paramedic nor the receiving hospital were aware of what medication was admin-istered. The results: IM midazolam stopped the seizure before hospital arrival 73.4% of the time while IV lorazepam was 63.4% effective. They conclude that midazolam is safe and effective.

Although IV lorazepam had a more rapid onset, establishing an IV in a seizing patient was widely variable. Thanks to accurate time stamps, this study clearly proves that auto-injectors allow for rapid administra-tion of medications and faster seizure ces-sation—even if the IM medication is slower to take effect. Patients who received mid-azolam were also hospitalized less often and required fewer intubations.

Now for the unique components that make this a landmark study. The authors used a special box that contained both an auto-injector and the IV medication. The paramedics were blinded to which treat-ment they were administering by having them give all patients an IM shot first, then starting an IV and giving everyone an IV bolus. All the auto-injectors and syringes looked the same, so it was impossible to tell which had active medication.

36 JEMS MAY 2012

researCH reVIeWWhat current studies mean to ems

>> by david Page, ms, nremt-P

Gender MaTTersStudy compares cardiac care for male vs. female patients

study evaluated IM vs. IV treatment.

Pho

to is

toc

kPh

oto

.co

m

036_037_ResearchReview.indd 36 4/17/2012 10:34:43 AM

www.jems.com mAY 2012 JEMS 37

David Page, MS, NREMT-P, is an educator at Inver Hills Community College and a paramedic at Allina EMS in Minneapolis/St. Paul. He’s a member of the Board of Advisors of the Prehospital Care Research

Forum. Send him feedback at [email protected].

Visit www.pcrfpodcast.org for audio commentary.

If the box contained “active” midazolam auto-injectors, then the IV bolus was a pla-cebo and vice versa. If the box had “active” lorazepam IV bolus, then the auto-injec-tor was a placebo. This is clever because many studies have shown that providers will go to great lengths (even tasting the two medications) to uncover which is the “active” medication. This often destroys the randomization process that is so critical to research.

Another interesting technique was the inclusion of an automatic, time-stamped voice recorder that was activated as soon as the box was opened. Most studies try to use the notoriously inaccurate times on the patient-care report or have providers fill out an extra piece of paper with study information—or sometimes they even have to be interviewed by telephone after the fact. The paramedics in this study could simply say what was happening, such as the “IM shot has been given” and “the seizure has stopped.” The recordings were later analyzed and the accurate time stamp extracted.

Note that Seattle’s Medic One program has measured improvements objectively for decades with voice recordings for cardiac arrest patients. This system pro-vides valuable feedback, which the crews look forward to hearing to help measure improvements objectively. The technique, however, is dependent on a cumbersome ECG monitor add-on, and it unfortunately hasn’t caught on with the rest of us. It’s too bad we appear to be more afraid of recording our errors than we are motivated to learn from them, and eventually save more lives. Congratulations to RAMPART for incorporating state-of-the-art recording boxes to get accurate data. JEMS

I glossary IPlacebo: Simulated but ineffective or inert medication replacement, such as giving injecting saline instead giving an actual medication.