ISSUE 7 - Karwansaray Publishers

Transcript of ISSUE 7 - Karwansaray Publishers

NINEVEHTHAT GREAT CITY

WW

W.A

NCIE

NTHI

STOR

YMAG

AZIN

E.CO

M //

KARW

ANSA

RAY

PUBL

ISHE

RS

THEME - SENNACHERIB'S PALACE // ISHTAR // WHY DID ASSYRIA COLLAPSE? // XENOPHONSPECIALS - HYPATIA // CONSTANTINE THE GREAT // FACT-CHECK: MARATHON // THE SCEPTICS

ISSUE 7ISSUEISSUE 7 7

US/CN $10.99 // €7.50

12

074

47058

034

8

DEC / JAN 2017

ahm_7.indd 1 28/10/2016 16:49

ahm_7.indd 2 28/10/2016 16:49

Ancient History Magazine 7Ancient History Magazine 7 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

THEME:

We take a look at Nineveh, the last capital of the ancient Assyrians, who were the first to unite the Near East.

The rise and fall of Nineveh A city without rival

The wonder of NinevehThe palace of King Sennacherib

Survival of the fittestCounting the words that remain

The Lady of Heaven Ištar of Nineveh

Why did Assyria collapse?A look at the imperial structure

The ruins of empireXenophon's visit to Nineveh

Discovering AssyriaNineveh in the 19th century

SPECIAL FEATURESSuperhuman featuresThe colossus of Constantine

Caught between religions The death of Hypatia

Birds greeting emperors The parrot in antiquity

Moors and mountains The Romans in Scotland

Fundamental uncertainty The philosophy of the sceptics

DEPARTMENTSProlegomenaEditorial, on the cover, and more

Fact-checkA clash of civilizations?

Book reviews Recent writing on the ancient world

How do they know? How to reconstruct ancient texts

THE WRITE STUFF There are many ancient languages. But how do we determine the most important ones?

NINEVEH, THAT GREAT CITY

HELLO BIRDYIn antiquity, parrots were a source of wonder (and an exotic ingredient for Roman chefs).

14

21

24

28

31

38

42

6 54

4

47

62

8

24 50

50

58

65

Publisher: Rolof van Hövell tot WesterflierManaging Director: Jasper OorthuysEditor: Jona LenderingContributing Editor: Josho BrouwersProofreading: Naomi Munts, Marie Smit-RyanDesign & Media: Christianne C. BeallDesign © 2016 Karwansaray Publishers

Contributors: Kees Alders, Radu Alexander, Maura Andreoni, Sidney E. Dean, Marc DeSantis, Roel Koni-jnendijk, Sean Manning, Daan Nijssen, Andrei Pogăciaș, John Richardson, Sara Van Hoecke, Lauren van Zoonen

Illustrators: Milek Jakubiec, Julia Lillo, Maxime Plasse, Radu Oltean, Vilius Petrauskas, Graham Sumner

Advice: Alessandro Frassine, M. Piacentino, David St-ronach, Suzanne Bott, Mary Prophit, Diane Siebrandt

Print: Grafi Advies

Editorial o�cePO Box 4082, 7200 BB Zutphen, The NetherlandsPhone: +31-575-776076 (NL), +44-20-8816281 (Europe), +1-740-994-0091 (US)E-mail: [email protected] service: [email protected]: www.ancienthistorymagazine.com

Contributions in the form of articles, letters, reviews, news, and queries are welcomed. Please send to the above address or use the contact form on www.ancienthistorymagazine.com

SubscriptionsSubscriptions can be purchased at www.kp-shop.com, via phone, or by email. For the address, see above.

DistributionAncient History Magazine is sold through retailers, the internet, and by subscription. If you wish to become a sales outlet, please contact us at [email protected]

Copyright Karwansaray B.V. All rights reserved. Noth-ing in this publication may be reproduced in any form without prior written consent of the publishers. Any in-dividual providing material for publication must ensure that the correct permissions have been obtained before submission to us. Every e«ort has been made to trace copyright holders, but in few cases this proves impos-sible. The editor and publishers apologize for any un-witting cases of copyright transgressions and would like to hear from any copyright holders not acknowledged. Articles and the opinions expressed herein do not neces-sarily represent the views of the editor and/or publishers. Advertising in Ancient History Magazine does not nec-essarily imply endorsement.

Ancient History Magazine is published every two months by Karwansaray B.V., Rotterdam, The Netherlands. PO Box 1110, 3000 BC Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

ISSN: 2451-8700

Printed in the European Union.

Unless otherwise indicated, all photos are copyright Karwansaray Publishers or Livius.org.

ahm_7.indd 3 28/10/2016 16:49

Ancient History Magazine 74

PROLEGOMENAI was nineteen years old, serving as a sol-dier, when I read about Mesopotamia for the first time. When you think about it, that is quite late. After all, the ancient Near East witnessed many “firsts”: agriculture, sanctu-aries, domesticated animals, metal working, interregional trade, monumental architec-ture, cities, the wheel, writing, empires, lit-erature, mathematics… all quite important, all documented for the first time in the land of the Euphrates and Tigris, all practically ig-nored when I went to high school. This blind spot is the consequence of a western view on history, which uses a kind of template. In this view, the people of the ancient Near East were deeply religious and tended towards obscurantism, while the Clas-sical West invented rationalism, philosophy, science, art, freedom, democracy. Growing interest in “the Greeks and the irrational” and the publication of thousands of cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia – a corpus that is about as large as all Latin literature (see page 26) – have made this template obsolete. To the list of Mesopotamian “firsts”, we can now add early forms of scientific thought. Still, the two great Mesopotamian civiliza-tions, Babylonia in the south and Assyria in the north, are not as well-known as Greece, Rome, or Judaea. This may have been one of the rea-sons why heritage organizations received so

Ancient texts were written on scrolls of papy-rus. The vulnerability of this writing material forced ancient library owners to have their scrolls copied about every hundred years, which was a great e«ort. One solution was to replace the scrolls with parchment books, which were more durable. They were also more expensive, but the fact that papyrus ulti-mately went out of fashion proves that parch-ment was considered a good investment. Still, all texts had to be copied and if there was no immediate audience, library

owners would not waste money on them. To put it simply: every ancient text was bound to disappear sooner or later unless it continued to find a readership and people willing to pay for copies. Therefore, much ancient literature has been lost. Nobody was interested in the last book of Polybius’ World History, in which he told about his sources. The po-etry of Sappho went out of fashion, was not copied, and is now lost – except for some 200 fragments. Of the twelve large poems

little support when vandals started to loot the ancient sites of Iraq in 2003, a process that gained momentum after the Arabian Spring, and has reached its nadir with the demolishing of archaeological sites by IS terrorists. Although vandals, terrorists, and the buyers of illegal antiquities do their best to erase the cradle of civilization from history, it is ironic that they achieve precisely the opposite: because of the destruction of so many ancient sites, there has been more attention for the old cultures of the Near East than ever. This issue of Ancient History Magazine will not repair the damage but can give you a sense of the scope of the first world empire of Antiquity. AHM

— Jona LenderingEditor Ancient History Magazine

Hiatus: Texts

Editorial

PROLEGOM

ENA

ahm_7.indd 4 28/10/2016 16:49

Ancient History Magazine 7

Correction On page 3, you will find some small print:

“unless otherwise indicated, all photos

© Karwansaray Publishers or Livius.org”.

Other photographers are credited more

fully and we regret that we forgot, in our

sixth issue, to mention the Satricum Pro-

ject of the University of Amsterdam for

the photos on page 16-21.

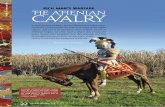

The cover, made by Radu Oltean, shows a

scene in the “Lachish Room” of the Palace

of King Sennacherib in Nineveh. The king

himself is based on a relief from Khorsabad

King Sargon II (right) and his son Sen-

nacherib (left) on a relief from Khors-

abad, now in the Louvre, Paris.

that constituted the Greek Epic Cycle, only the Iliad and the Odyssey survive: about one third of the entire corpus. A surprisingly great number of an-cient texts have survived in only one copy, which shows how vulnerable the process of transmission was. If this one copy was damaged, the contents are forever lost. The final chapters of Aristotle’s Poetics are missing, perhaps because the last part of a scroll was torn o«. The same can be said about the manuscript of the six first books of Tacitus’ Annals: there is a gap at the end of Book 5 and the beginning of Book 6, which suggests that several leaves of a book have disappeared. Only occasionally, something important is added to the corpus of ancient texts. In Her-

culaneum, one of the towns destroyed when the Vesuvius erupted in AD 79, burnt scrolls have been found: a library with texts by the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus of Gadara. Two years ago, “new” fragments of Sappho surfaced. The number of authentic plays by Eu-ripides rose from eighteen to nineteen when in 2007 a large part of the Phaethon was redis-covered. (Seventy-six plays are still lost.) Discoveries like these are exception-al. The Roman writer Suetonius published Lives of famous prostitutes and Physical de-fects of man but we will never know what is behind these intriguing titles. This is very disappointing, but on the other hand, this lack of evidence leaves us free to speculate about the lyrics of Nero’s song about the destruction of Troy. AHM

On the coverthat is now in the Paris Louvre; the courtier is inspired by representations on reliefs from Khorsabad and Nineveh.

THE NUMBER: 753When Rome had become a great power, it would occasionally build completely new cities. There was an o�cial ritual for this and it could be said that these new towns had been built in a particular year. This made the Romans believe that the found-ing of their own city had been a precisely datable event as well. Today, we think that this was the wrong question. There were peasants liv-ing in what is now called Rome as early as the second millennium BC; their vil-lages clustered together during the Iron Age; this conglomerate would become a real city in the course of some two centu-ries. Unlike later city foundations, Rome wasn’t built in a day. Still, the Romans tried to establish a year in which their city had been founded. Towards the end of the third century BC, a historian named Fabius Pictor thought

that it was the first year of the eighth Ol-ympiad, which is between the summers of 748 and 747 BC. His contemporary Cincius Almenus believed it was 728/727, and one generation later, Marcus Porcius Cato pointed at 752/751. This date was also used by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Livy, and Velleius Paterculus. In the mid-first century BC, Mar-cus Terentius Varro said that Rome had been founded in 754/753. As it hap-pens, we know how he arrived at this date. Erroneously believing that Rome had become a republic in 509/508, he added thirty-five years for each of Rome’s seven kings. This is clearly an unscientific approach. Of all possible dates, the date that is nowadays most often given for the foundation of Rome, the year 753 BC, is the only date about which we know why it is wrong. AHM

5

ahm_7.indd 5 28/10/2016 16:49