ISSN Number 1353-7008 Cycle Coaching

Transcript of ISSN Number 1353-7008 Cycle Coaching

The Journal of

Cycle Coaching 2014/1 ISSN Number 1353-7008

The Association of British Cycling Coaches Developing and Sharing Best Practice

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

ABCC

Editor: Mr James Smith27 The Dell PlymouthPL7 4PSEmail: [email protected] Tel: 01752 248664Mobile: 07886280979

Administrator: Mark Gorman 3 Glebelands, Calstock, Cornwall. PL18 9SG Email mark.gorman@abcc .co.uk Tel: 01524 701340 Mobile: 07974 887259

Chairman: Bob Hayward Red House, The Street, Redgrave, Diss, Norfolk, IP221RY Telephone: 01379 898726 Email: [email protected]

Treasurer: Chip Rafferty

Committee Members: Richard Guymer, Gerry Robin-son, Dave Wall, Gordon Wright, Martin Nash, Duncan Leith, Richard Reade

Content

Foreword .................................................................................................................................3 Why The Warm Up?(pbscience.com)..................................................................................4Top Ten Errors for the Endurance Athlete to Avoid(pbscience.com)...............................6 Pedal Power 2013(Lewis Hall)................................................................................................9 Tri-Fitting Requires A Scientific Approach (Nicholas J Dinsdale)......................................10 Body Position Can Affect Cycling Comfort, Overuse Injury, and Performance:

A Review of the Literature, Part I (Nicholas J Dinsdale)..................................................12Books Reviews...................................................................................................................... 18 Costa Darauda.................................................................................................................... 19

2 Page

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

Foreword James Smith Editor Contribution

Many riders get to that point where they feel that they should take the next step. Improve their nutrition, get a bike fit, buy a power meter. We have all seen it before and long may it continue. However, athlete expecta-tion and your responsibility to your client are important. I think the management of athlete expec-tation is as important as any other facet of coaching. Your client wants to be told the truth not what he wants to hear. If you think his targets even after his nutritional improvements, his new disc wheel etc are unreasonable then tell him don’t lead him onto failure as this will mean an unhappy coach and unhappy client. Your coach client relationship should be based on realistic expectations and honesty, this leads to a longer term relationship and an overall higher success rate.This edition of the journal has tried to move back to the scientific journalistic mode, this is continuing learning experience for us all but to be able produce this journal ev-ery quarter we really do need feedback and articles from you out there. So again I ask please send any articles for review to me [email protected] you all have a great spring and I look forward to hearing from you all over the next few months. For now enjoy the journal and its offerings.

Page 3

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

Why The Warm Up? from pbscience.com

4 Page

id-up’3. It is acidity that brings about the following:

‘Potentiation’ of muscle fibre recruit-ment – preparing the fibres for more effective and efficient contraction to do workIncreased muscle blood flowElevation of oxygen uptake and switch-ing on of the aerobic system.

Surely acidity isn’t a good thing?

Most athletes associate acidity with blood lactate build up and subsequent fatigue. However, a lot of research sug-gests that it is acidity that prepares the body to exercise, especially at race pace intensities.

Research work performed at the University of Brighton4 indicates that exercising at intensities above the lac-tate threshold, and therefore inducing acidity in the muscle tissues, leads to an elevated oxygen uptake ahead of a second bout of exercise. Therefore, less of the following exercise is performed anaerobically i.e. there is a lower oxygen uptake debt. Initial sparing of the an-aerobic capacity may lead to improved performance, as it is a reserve that can then be utilised later on in races.How the acidity leads to this change isn’t entirely clear yet, but may be related to how oxygen is off-loaded to tissues. Think back to school biology lessons where you may have been intro-duced to the ‘Bohr effect’. When CO2 and hydrogen ions increase because of exercise, the associated acidity increases the dissociation of oxygen from hae-moglobin to the tissue, allowing the tissue to obtain enough oxygen to meet its demands. In a similar way, warm-up exercise affects the degree of oxygen at-tachment to the haemoglobin– research shows warm-up enables the body an extra ‘reserve’ of O2 early on in exercise.

Interestingly, despite not being able to give you a conclusive answer as to why, most would be reluctant to give up or alter their warm-up routine. Indeed, most people would indicate that it is not purely a physical benefit, but also psychological readiness to perform. For some, it might also be a chance to check equipment is running smoothly prior to the event.

Just how important IS a warm-up?

The impact of warm-up appears to depend on the event duration – the po-tential for improvement seems greatest in short term endurance events (up to 10 minutes) and less as event duration increases. A recent study looking at 3km time trialling1 suggests a signifi-cant improvement is to be gained, espe-cially in the first 1km of performance, with power output being increased by some 40W. Less, but still meaningful, improvements of ~30s are to be gained for events of ~20 to 30 minutes2.

What is the physiology surrounding the efficacy of warm-up?

The name implies that the majority of the effects observed with prior exercise are attributable to temperature related mechanisms:

An increased conduction rate of neural impulsesGreater offloading of oxygen from the blood (haemoglobin) to the muscleSpeeding of certain metabolic reactions – especially use of the anaerobic energy systemImproved flexibility around muscle and joint systemsMore likely though, performance enhancement may follow on from the metabolic acidity brought about by previous exercise. This has led some researchers to prefer use of the phrase ‘ac-

It is possible that residual acidity in the system changes muscle fibre recruit-ment patterns. If the acidity of the muscle is decreased, the body may re-spond with recruitment of more muscle fibres to maintain force development. A further possibility is that muscle blood flow is increased: Acidity leads to in-creases in bradykinin, a known ‘vasodi-lator’, which opens up the capillary bed of the exercising muscle tissue.

Intensity of warm-up

If, as suggested, warm-up is more likely to work when resting muscle metabo-lism is disturbed, the intensity of warm-up is critical to whether it works for an athlete or not. As explained above, research has found a link between the intensity of the warm-up and the oxy-gen uptake response at the beginning of exercise. Recent work in our laborato-ries investigated whether performance is actually improved5.

We took a group of cyclists and asked them to perform three types of warm-up: below the lactate threshold (mod-erate); above the lactate threshold but below the ‘Critical Power’; and above the critical power (severe); and to then enter a performance trial at the CP (this intensity approximates 10 mile time trial pace in most people. We discounted a temperature related effect by equalising the work done across all types of warm-up (so, watts x time was the same for all conditions). We also made sure we used a warm-up that ath-letes are familiar with i.e. short bursts of activity interspersed with recovery – emulating ‘strides’ or ‘leg openers’.

The effects were quite extraordinary – the ‘heavy’ warm-up not only decreased the oxygen deficit at exercise onset but also improved time to exhaustion by 45s (in a trial lasting ~15 - 20 minutes). The severe warm-up also changed the

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

oxygen uptake response, yet did not give similar changes to performance. In other words, the exercise intensity for the warm-up is crucial: moderate exercise does not enhance the aerobic contribution to subsequent exercise, whereas severe-intensity exercise causes too much disruption for the restoration of resting metabolism and/or removal of fatiguing metabolites.

Take home message

While more ‘aggressive’ methods should be utilised prior to shorter events, with long term performance care must be taken to ensure performance is im-proved not impaired – to preserve the muscle glycogen stores and to avoid excessive thermoregulatory strain

The key to warm-up is balance – you need to exercise hard and long enough to ‘rev up’ the system, but not so hard that you leave the muscle tissue in a fatigued state.

The problem most athletes have is gauging this balance. Most athletes will hold back on their warm-up in fear of going into the race tired.

It makes sense therefore for athletes and coaches to assess critical power and define the border between heavy and severe exercise. This takes the guess work away, and allows the athlete full confidence in their preparation.

For more information on how to make best use of your warm up see the factsheet “The practicalities of warm up”. (http://www.pbscience.com/train-ing-articles/factsheets/583-the-practi-calities-of-warm-up.html)

REFERENCES

1. Hajoglou, A. et al. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005, 37, 1608-1614.

2. Atkinson, G. et al. J Sports Sci

2005, 23, 321-329.

3. Bishop, D. Sports Med 2003, 33, 439-454.

4. Burnley, M. et al. J Appl Physiol 2000, 89, 1387-1396.

5. Carter, H. et al. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005, 37, 775-781.

Page 5

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

Top Ten Errors For The Endurance Athlete To Avoid

from pbscience.com

6 Page

water, but you can’t make them drink”: many athletes return home with the same drinks they left with! By the time we feel thirsty, it is often too late to hy-drate. Dehydration can lead to muscle cramping, elevated heart rate (as you lose fluid from the blood plasma), and increased rates of muscle glycogen use with a subsequent decrease in ability to produce power. How much should one drink? Suggestions range between 500-750 mL/hr, and this will fulfil most athletes’ hydration requirements under most conditions. Turn up the heat, and you will need more. It is not uncom-mon for the athlete to neglect hydration during the winter months, as we don’t associate wrapping up warm against the elements to require hydration. However, sweat rates will be higher in thermal clothing. A good exercise is to weigh yourself pre and post session – the amount of kg you lose is equivalent to the water you lose. Next time, look to drink about 150% of the weight you lose – that extra volume is needed since the body will not be totally efficient at recouping the fluid lost.Whilst in business the catchphrase “cash is king” predominates, in training principles it becomes “consistency is king” – it is better to be realistic about training in the planning phase and to hit this week in, week out than to start out with high ambition and find your-self chasing your tail.The same principles apply to fuelling during exercise: wait until you notice a drop in intensity, or even feel hunger (yes, it happens!) and it is probably too late to rescue your muscle glycogen stores. ‘Hitting the wall’ or ‘bonking’ is not a nice experience, and affects not only that training session, but could compromise the next day’s training too. You are better off keeping a steady and consistent rate of carbohydrate fuelling than cramming it in to the second half of a session. Be particularly vigilant in sessions involving the upper ‘steady’

The title of this article may be a little misleading - there are obviously more than ten mistakes that athletes can make, but those listed in this article represent the most common perfor-mance-jeopardising. Some of these may seem basic and obvious, but you’d be amazed how many athletes neglect the basics and then wonder why their performance isn’t as good as it could be. Carefully read through the description of each of these mistakes: at least some of them will sound familiar – and keep in mind, there’s nothing wrong with making mistakes, its only human. What IS wrong is making the same one, over and over again.

1. Over reliance on sports nutrition products.There is no denying that the sports nu-trition industry is undergoing a massive boon time. A general awareness that the professional athlete is now seek-ing every performance edge, coupled with sports teams being sponsored by companies in the industry makes for high growth in sales. However, for the amateur athlete, sports nutrition prod-ucts are seen as a q uick fix in filling the gaps left by poor general nutrition. At its worst, these products are even seen as part of the identity of being an athlete – the post race recovery drink being a badge for some to wear.There is no substitute for getting your foundational nutrition right – eat a healthy diet FIRST, and use supple-ments as intended – as supplements! There is nothing wrong with sports nutrition products per se; it’s the abuse of them, rather than the use of them where the athlete must be aware.

2. Inadequate fuelling and fluid intakeIt is one thing to get people to take more drinks out on training rides – but as the old saying goes “you can lead a horse to

training zones (3 and 4) as these are heavily reliant on muscle glycogen, but may not feel so early on: it will catch up on you. Try to fuel in the last 20 to 30 minutes, and it is probably too late for sufficient carbohydrate absorption to help you home. 3. Trying to play ‘catch up’ on the training planThe training athlete will undoubted-ly lose training time at some point in their career: whether it be due to injury, illness, or even if work load and other lifestyle issues get in the way of completing the sessions detailed on the training plan. All too often though, the athlete becomes anxious about losing the session: meaning they attempt to double up on a given day to make amends. This probably does more harm than good, and can impact on the subsequent training – taking effect on the rate of progression the athlete can deal with (in terms of intensity, volume or frequency of sessions coming later in the training block).

The best advice to give is that if you miss a session, leave it to the past. The very fact you missed a session tends to indicate a rest was needed: even if the session was omitted because of non-training related incidents (like, getting home from work too late to train). Instead, give yourself permission to have a set number of ‘jokers’ to play in a training block (e.g. 3 extra rest days in a 10 week period).

4. Not taking enough restUnfortunately, because our working lives and society in general operates in a 7 day week, we tend to make our training cycles fit that pattern too. This can mean that we spend too many days a week training. Even if we attempt to split our weekly training hours evenly, we often end up with a 6 day cycle: which because of the 7 day system

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

means 6 days straight!

The body can only adapt to the physical stimulus of training when metabolic rate is reduced: tissue, muscle in partic-ular, cannot be anabolic and catabolic at the same time. Training strips the body down (catabolism), whilst recovery and nutrition allow re-building work to commence (anabolism).

It is better to train with good quality on fewer days a week than stick to a reg-imen of a set weekly volume objective just for the sake of it. Also, if you have restricted time for training, use those hours wisely – remove the padding of ‘recovery’ sessions, and instead use that time to rest, or catch up with other aspects of life that sometimes get com-promised: the mental break will give you an edge for your next session.Remember that recovery is as import-ant a part of your training and the achievement of your athletic goals as the actual training session. Make sure that you take your recovery as seriously as your training.

“Never stand when you can sit,never sit when you can lie down”

5. Under valuing ‘total stress’ and its impact on training and performanceVery few athletes are in tune enough with their bodies to be aware of how stress extrinsic to their training is im-pacting on them: both as athletes, and as humans. The odd sleepless night, or a slight dip in the motivation for training can often indicate that total stress is too high. It is often only when athletes look back over a season that they pinpoint poor performances due to factors out-side of their own control. The power of hindsight is a marvellous thing!

Think of a pie as a representation of the total stress you can cope with: there will be a slice for work, for family / social commitments, for money management, as well as for training, and for racing – you can probably think of many more areas of your life. The total size of this pie has to stay the same in order for you

to maintain health and balance: work stress goes up? Another slice must come down to compensate – and, as most athletes tend to be part time, it might be training stress (volume, intensity, frequency) that might have to be the compensatory factor. Be gentle on your-self, and take the foot off the pedal if needed. The body is better able to adapt to training if that training stands on a firm pillar of health.

6. Using something new in a race without having tested it in trainingThe title is pretty self-explanatory; it’s one of THE cardinal rules for all athletes, yet you’d be amazed at how many break it. Are you guilty as well? Unless you’re absolutely desperate and willing to accept the consequences, do not try anything new in competition, be it equipment, fuel, or tactics. These all must be tested and refined in training.

A common trap is where an event might be sponsored by a particular nutritional supplier. The athlete quite understandably uses the freebie product, and having not been used to it, they experience issues which causes deterio-ration in performance. Don’t let this be you: do your homework.

7. Racing too oftenIn his book the ‘7 habits of highly effec-tive people’, Stephen Covey refers to the “P/PC balance”, with ‘P’ standing for production and ‘PC’ production capability. The most famous example of this being the golden egg laying goose - you may have read this fable of Aesop: where the greedy farmer and his wife kill the goose, hoping they will find it full of gold. A rather simple illustration how people sacrifice the capability to produce in order to get the product, and to get it now! Training is the devel-opment of that ‘PC’, and long term, this is what is going to make you the better athlete: this investment in time (and patience) is well worth the effort. If you focus on ‘P’ too often, while you might appear to be ahead of the game, its short lived - soon you see those who have invested in PC overtaking. How

often we see ‘early season stars’ burn out.

This is where periodisation comes in: the scientific progression of training load - structuring the training year, working on building intensity in a step-wise manner, means we slowly nudge the body towards race pace: miss a step (i.e. start racing too soon) and you have missed out on a vital link in the chain. Think about how the body must build more structures, the proteins it must lay down, in order to cope with increasing workload. A classic example would be how zone 3 training is needed to boost capillary growth in the muscle bed before you work at zone 4 where lactic acid clearance determines performance level - less capillaries, less clearance. Start racing too soon, you jump steps (PC) that will ultimately limit your performance (P).

8. Not paying attention to detailIn preparation for sports performance, it is very easy to put the focus entirely on the training side of the equation. However, performance is built on 3 pillars:• Training is to stress the body, and

convince it to rebuild stronger to withstand more stress

• Recovery gives the body time to re-build, without it, the body won’t change.

• Nutrition provides the building blocks for the body to take and re-build

Take one of those pillars away, and you won’t get fitter, full stop. In other words, one is no more important than the other. It is one thing to ‘do’ a sport: but another to ‘be’ an athlete. You might break down sports performance further and consider other areas you could work on. How well do you keep your equipment serviced? How well do you prepare mentally for the events? Cov-ering the basics well will get you a lot further than training every spare hour you have – think about how you might devote time you have used traditional-ly for training to get more rest whilst applying effort elsewhere. For example,

Page 7

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

8 Page

how about taking an extra day off and using that time to practice mental im-agery, or to try a new recipe for a post training session meal?

9. Doing the same thing, week in week outWhen people enter a new sport, there is a temptation to rush at it without considering their long term plan. They try to put together a training plan that encompasses everything they might have heard about: base miles, intervals, speed work, tempo – the list goes on. This is understandable with novices. With time, athletes should soon start to use an approach where their year is ‘pe-riodised’: layers of training are applied at times specific to their season and key goals. However, there are still athletes who try to cover all bases simultane-ously, with the extreme being a mix of training sessions across all training zones in the same week, repeated every week of the year!

The body’s systems are no different to the human at the broader level – do too much of the same thing, and it will stagnate. Target your training so that you work in cycles, changing the stress to keep the body guessing. You will probably find you develop favourite sessions, and ones that you believe bring your fitness on the most efficiently. But exercise some caution, and try to keep things fresh – it helps mentally as well as physically.

10. Keeping your eye on YOUR ballOne of the questions coaches find themselves addressing most often is “why haven’t I started my intervals yet, everyone else has?” Understandably in sport - its very nature meaning we are competing with others - we often look around to compare ourselves. However, remember that each and every athlete has their own plan, their own goals, and even their own strengths and weakness-es. Two people with the same race goal will probably need different training because of their inherent physiological profile; likewise, two athletes with the same fitness might undergo different

training paths because of when in the year they wish to peak.

This also extends to the micro level too – within each training session, two riders might need to focus on different aspects. This can be particularly difficult in group training rides, or on training camps. Each athlete will have their own training zones, their own agenda. Put effort in sticking to YOUR plan, and not riding to their goals.

Message to take home:Preparation for sports performance doesn’t need to be sophisticated – most of the time athletes can get 90% of the way to their potential by taking a step back and applying some “good old common sense”. Why do so many fail to do this? Probably because we are too involved – working with a coach, someone with an objective view of your position, is the best way to get the sup-port where you need it. Also, get into the habit of asking a trusted ally (avoid close friends or family, as they tend to have a particular view of you) what they would do – you don’t always have to follow their advice, but sometimes it helps in seeing the bigger picture.

Pedal Power 2013 by Lewis Hall

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

The Starley Suite at Coventry Trans-port Museum once again provided a world class venue for Pedal Power. Attended by more than 40 coaches and riders from around the UK with two of the speakers travelling from France.

Lionel Reynaud and Dr. Roxane Blatters <ABCC coaches> work with a number of French professional teams including a number of leading riders. During their recent studies of power : weight ratios across a range of clients, they discovered a number exhibiting significant declines in performance despite following carefully planned race programmes and training schedules. Detailed investigations revealed that all had taken measures to reduce their nor-mal, racing weight. Individuals mistak-en in the belief that significant weight loss would improve their measured ratios. Unfortunately, all the affected riders were judged to have taken weight reduction too far. As a consequence, they had introduced health problems which resulted in power losses. Only corrected by very careful attention diet , increased body weight and a rebalanc-ing of hormone levels.

In complete contrast to the foregoing scientific studies, was the practical emphasis underpinning the Bikeabil-ity presentation by David Hearn and Patrick O’Kane, both active cyclists, employed as Instructors in Coventry. Working within a part of the national programme which caters for young people and adults. Namely, Cycling Proficiency in the 21st Century. The speakers explained how this provided 3 levels training, each level progressing to increased proficiency, road safe-ty and levels of attainment. Level 1 being focused on road safety, bike fit and road worthiness, routine safety

checks, weather protection all linked to increased cycling skills, The scope of training undertaken by Instructors was explained together with the interface relations with other organisations. During their talk, the speakers demon-strated the communication techniques employed together with the manage-ment of social, cultural and disability is-sues. When required, even the provision of bikes ! Clearly, Bikeability presents numerous challenges to Instructors. The delegates were left in no doubt as to the effectiveness of Bikeability and the re-wards of seeing participants developing cycling and social skills that may have escaped them, but for this programme, and allied to the dedication of people like David and Patrick. Booklets and DVD’s covering Bikeability were freely available to all attendees.

An unscheduled and welcome addition to the days programme came from Kevin Dawson, eleven times British Best All rounder Champion and with numerous national time trialing hon-ours to his name. Kevin spoke with Jim Sampson on the challenges faced by the riders and officials when competing in The Race Across America. And how after eleven days of non-stop riding, the relay team missed the outright win and setting a new record by a heart breaking 15 minutes ! The Ramin Minovi Medal was awarded by the ABCC to Mike Burrows, the legendary bicycle designer. Fore-ever linked to the Lotus bike on which Chris Boardman won the Olympic gold medal in the 1992 Games. Later, Mike was employed by Giant to undertake the creation and design for their com-pact range of frames. A concept now widely adopted across the industry. But on this occasion, Mike spoke on “The

search for the perfect machine”. In so doing, and in a most entertaining and informative delivery he explained the factors bearing upon bicycle perfor-mance. Including aerodynamics, mate-rials, geometry, transmissions, brakes, tyres and wheels and the technology behind the machines we love, equip, replace and adjust - and sometimes hate ! Elsewhere within Cycle Coaching is a review of Mike’s book Bicycle Design which contains information referred to in his talk.

The final speaker of the day was Dr. Gordon Wright, another ABCC coach and a man who has been coaching riders for over 30 years. During this time he has been able to assist the progress of absolute beginners through to a number of riders who have been successful in National Championships, Commonwealth and Olympic Games. Coaching across most disciplines. During his presentation of “Coaching and mentoring talented and motivat-ed riders, and challenges and lessons for coaches”, Gordon paid particular focus on the human characteristics, along with insight of the forces driving some champions. Touching upon the perceived, underlying reasons for their ambitions. In so doing,he provided fascinating and personal observations on some of the most successful and the lengths taken to achieve results at the highest level.

The morning and afternoon sessions were chaired in a timely way by Mar-tin Nash and Duncan Leith, with Jim Sampson teasing secrets from Kevin Dawson. The Annual General Meeting of the ABCC was held during the day, details will appear elsewhere.

Page 9

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 3:2013

Tri-Fitting Requires a Scientific Approach by Nicholas J Dinsdale

10 Page

20-35% cycle, and about 65-80% rider (3,4). These figures vary due to differ-ent bicycle design (5), rider shape and rider position (1,6,7).

Conserving energy for the runModern-day triathlon fit is about con-serving energy and muscle function for the run. There is clear evidence in Elite Olympic Distance Triathlon that run splits are a better predictor of overall

NJD Sports Injury Centre, based in Clitheroe Lancashire, strongly believe modern-day triathlon fitting should be based on science. The ideal Tri-fit is in-herently difficult that requires a delicate balance to optimise power-output, re-duce aerodynamic drag (aero-drag), and to conserve energy and muscle function for the run. Read on for more informa-tion on the science behind Tri-Fitting.

The aero-drag factorCyclists live in a world governed by physics where aerodynamics becomes relevant to all cyclists at speeds above 15km/h. When racing at speeds of 40kph, aero-drag accounts for approx-imately 90% of the total energy cost (1,2). Physics shows that to double your cycling speed necessitates you to generate eight-times more power out-put i.e. power supply.

Rider vs. bicycle drag factorWhich is more important? The answer is both – however the rider represents by far the greatest drag factor. Research shows us that the total composite of aerodynamic drag constitutes about

success (8,9). This is because drafting significantly reduces energy consump-tion (10,11). Consequently, the ability to run efficiently after cycling is crucial as it can improve the overall finish-ing position (12,13). However, while drafting is the main method of con-serving energy in elite events, research shows that appropriate frame geometry (14,15,16), body position (1,6,13,17), and potentially crank length (18,19)

Nick has a First Class BSc (Hons) in Sports Therapy and MSc (Distinction) in Sports Injuries. Nick has been Sports Therapist to the GB and England cycling teams, covering both domestic and overseas events. A keen athlete, Nick won the National Cyclo-Cross Series and many Cycle Time Trials. In 2013, at the first attempt, he won the National Standard Distance Duathlon (Age-Group) Championship. Nick specialises in lower-limb biomechanics and Bikefitting. His unique research was acknowledged by Spe-cialized USA and has since been disseminated worldwide.

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 3:2013

temporary triathlon: implications for physiological analysis and performance. Sports Medicine, 32:345–35911. Hausswirth C, Lehénaff D, Dreano P, et al., (1999). Effects of cycling alone or in a sheltered position on subsequent running performance during a triathlon. Med Sci Sports Exercise, 31:599–60412. Vleck, V. & Alves, F. (2011) Triathlon transition tests: overview and recommendations for future research, Inter Journal of Sport Science, 7(24):1-3 13. Vleck, V., Bentley, D., Millet, G. et al., (2008) Pacing during an elite Olympic distance triathlon competi-tion: comparison between male and female competitors, Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 11(4):424-43214. Burke, E., & Pruitt, A. (2003) Body positioning for cycling, in E. Burke (ed.) High-Tech Cycling, USA: Human Kinetics, pp. 69-92 15. Heil, D., Wilcox, A., & Quinn, C. (1995) Cardiorespiratory respons-es to seat-tube angle variation during steady-state cycling, Journal of Medi-cine and Science in Sports and Exer-cise, 27:730-73516. Price, D., & Donne, B. (1997) Effect of variation in seat tube angle at different seat heights on submaximal cycling performance in man, Journal of Sports Sciences, 15:395-402 17. Gnehm, P., Reichenbach, S., Altpeter, E., et al., (1997) Influence of different racing positions on metabolic cost in elite cyclists, Medicine & Sci-ence in Sports and Exercise, 9(6):818-82318. Martin, J., & Spirduso, W. (2001) Determinants of maximal cycling power: crank length, pedalling rate and pedal speed, European Journal of Applied Physiology, 84:413-418 19. Barratt, P., Korff, T., Elmer, S., & Martin, J. (2011) Effect of crank length on joint-specific power during maximal cycling, Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182125e96

Olds, T., Norton, K., Craig, N., et al.,

can be alternative methods for conserving energy in non-drafting events.

References

1. Gibertini, G., Campanardi, G., Grassi, D., et al., (2008) Aerodynamics of biker positions. BBAA VI Interna-tional Colloquium on: Bluff Bodies Aerodynamics & Applications; Milano, Italy, July, 20–242. Gnehm, P., Reichenbach, S., Altpeter, E., et al., (1997) Influence of different racing positions on metabolic cost in elite cyclists, Medicine & Sci-ence in Sports and Exercise, 9(6):818-823 3. Peveler, W., Bishop, P., Smith, J., et al., (2005) Effects of training in an aero position on metabolic econo-my, Journal Exercise Physiology online 8(1):44-504. Pruitt, A. (2003) Body posi-tioning for cycling, in E. Burke (ed.) High-Tech Cycling, USA: Human Kinetics5. Chowdhury, H., Alam, F., & Khan, I. (2011) An experimental study of bicycle aerodynamics. International Journal of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, 6(2):269-2746. Bini, R., Hume, P., and Croft, J. (2012) Cyclists and triathletes have different body positions on the bicycle, European Journal of Sports Science,7. Ashe, M., Scroop, G., Frisken, P., et al., (2003) Body position affects performance in untrained cyclists, Brit-ish Journal of Sports Medicine, 37:441-4448. Vleck, V., Burgi, A. & Bentley, D. (2006) The consequences of swim, cycle and run performance on overall results in elite triathlon Olympic dis-tance triathlon, International Journal of Sports Med 27:43-489. Frochlich, M., Klein, M., Pieter, A et al., (2008) Consequences of the three disciplines on the overall results in Olympic-distance triathlon, International Journal of Sports Science and Engineering, 2(4):201-210 10. Bentley D, Millet G, Vleck V, et al., (2002) Specific aspects of con-

(1995) The limits of the possible: Mod-els of power supply and the demands in cycling, Australian Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 27:29-33

Page 11

Body Position Can Affect Cycling Comfort, Overuse Injury, and Performance: A Re-

view of the Literature, Part I by Nicholas J Dinsdale

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

AbstractHistorically, improvements in cycling performance have focused predom-inately on physiological factors and training strategies. In contrast, few studies have investigated the implica-tions of body position. This two-part article examines the 3 classic disci-pline-specific body positions and their impact on comfort, incidence of overuse injury and cycling performance. Part I highlights key factors impacting on comfort and common overuse injuries. Part II examines key factors related to cycling performance. Moreover, this complete review scrutinises the rela-tionship between man-and-machine.

Introduction The unprecedented success of British Cycling, British Triathlon (Brownlee brothers) combined with the indefati-gable Boris Johnson’s 100 mile epic ride in the 2013 inaugural Prudential Ride London race has enthused the nation’s passion for cycling. Cyclists of all ages, gender and ability enjoy the multiple established health benefits and diverse uses cycling now offers. Cycling is used for commuting and recreational purpos-es, rehabilitation after joint replacement (Herndon et al., 2010), prevention of cardiovascular disease (Hoevenaar et al., 2011), cardiac rehabilitation (Oja et al., 2011) and an engaging plethora of competitive disciplines. Although there is disagreement within the scientific and coaching communities on cycle set-up and body position (Bini et al., 2012), this two-part article will attempt to highlight evidence-based parameters from which meaningful guidance can be derived.

Whether cycling for recreational or competitive purposes, a proper body position (riding position) achieved through cycle set-up is paramount for comfort, performance and fewer injuries (Burke and Pruitt, 2003). Pruitt (2003) admirably describes cycling as “a marriage between the adaptable human body and adjustable machine” (p69), achieved through proper set-up parameters at the three-contact points i.e. saddle, pedals, and handlebars (Burke and Pruitt, 2003). Just as cycles are designed to be discipline-specific to meet given demands (e.g. moun-tain-bike, road bike, and triathlon bike) it follows that cyclists should therefore adopt discipline-specific body positions for given cycling demands (Ashe et al., 2003; Bini et al., 2012).

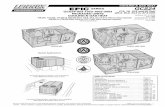

Figure 1 - The 3 Classic Body Positions

The 3 classic body positions As stated by Bini et al (2012), to date little attention has been given to body

position on the bicycle for different cy-cling disciplines. The needs and objec-tives of recreational and commuting cy-clists are fundamentally different from those of competitive cyclists. Therefore, guidelines for cycle set-up and body position should reflect the needs and objectives for each chosen cycling discipline. Essentially, most cycling disciplines can fit into one of 3 classic body positions (Pruitt, 2003) (Fig. 1). Figure 1a represents the typical moun-tain-bike, recreational and commuting position. The cyclist adopts an upright trunk. The priority is not aerodynamics, but more for a comfortable relaxed ride designed for improved vision, stability, traction, and handling characteristics. Figure 1b is a compromise between the two extremes: it is representative of road race cyclists and sportive riders. This position offers a compromise be-tween speed, handling and comfort. The classic road body position is dynamic, meaning small changes can be made for improved efficiency over different terrain. Figure 1c represents the classic road time-trialist and triathlon position. This extreme, aerodynamic position adopts a forward saddle position, with a highly flexed trunk, designed to minimise frontal area, thus minimise aerodynamic drag – in the quest for ground speed.

Marriage between man and ma-chine Historically, cycle set-up has been performed by cycle mechanics purely from a mechanical perspective, often unaware of anthropometric differenc-es, biomechanical peculiarities and/or musculoskeletal deficits prevalent in

12 Page

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

cyclists (Dinsdale and Dinsdale, 2011). The aetiology (cause) of overuse injuries are often multifactorial and diverse (As-plund and St Pierre, 2004; Hreljac et al., 2000). Meaning, overuse injuries can arise from an improper body position on the cycle, or intrinsic musculoskel-etal factors / deficits mentioned above, or a combination of both; in addition to extrinsic factors like training errors etc. Thus, common sense implies that ef-fective management of a given problem relies on an accurate initial diagnosis. Therefore, authors cite the emerging need to consider both man-and-ma-chine as a single integrated unit (Cal-laghan, 2005; Dinsdale and Dinsdale, 2014); e.g. a marriage between man and machine (Pruitt, 2003). To reinforce this more contemporary view, Cal-laghan (2005) states that “to obtain a diagnosis for a cycling related problem we must evaluate faults in the bicycle as well as in the cyclist”.

Overuse injuries attributed to im-proper body positionDespite the popularity of cycling, the epidemiological study of overuse musculoskeletal injuries among cyclists remains scarce (Clarsen et al., 2010). Nevertheless, overuse injuries have been reported amongst a wide range of cycling disciplines, e.g. mountain-bikers (Sabeti et al., 2010), road cyclists (Cal-laghan, 2005) and triathletes (McHardy et al., 2006). There is no complete es-cape from injuries, all ages and abilities, from recreational to professional cy-clists, are affected (Wanich et al., 2007). Overuse injury is caused by repetitive mechanical overload of the bone, joint and soft tissue with inadequate recovery time (Taimela et al., 1990).

An improper body position (cycle set-up) is frequently cited as a major cause of overuse injury (Callaghan, 2005; Clarsen et al., 2010; Marsden, 2010). While not exhaustive, factors include pedal systems (Wheeler et al., 1995), issues at the shoe/pedal interface (Asplund and St Pierre, 2004; Berry et al., 2012; Dinsdale, 2012), saddle height (Peveler and Green, 2011), saddle tilt

(Sommer et al., 2010), saddle design and trunk angle (Carpes et al., 2009), handlebar position (Partin et al., 2012), and anthropometric differences (Dins-dale and Dinsdale, 2014). Furthermore, musculoskeletal deficits can prevent some riders from acquiring a disci-pline-specific body position, or at least, compromise their ability to do so (Din-sdale and Dinsdale, 2011). For example, poor spinal flexibility can compromise a true aero-position. Inadequate hip-joint flexion may adversely affect pedalling action over top-dead-centre, causing the knee to flick outwards.

Common cycling related overuse injuries The most frequently reported ana-tomical areas of overuse injuries are the lower back, perineum, hand, knee and foot (Schwellnus and Derman, 2005). The knee is the most common site (O’Brien, 1991; Silberman, 2012), affecting an estimated 40% to 60% of all regular cyclists (Wanich et al, 2007). Clarsen et al (2010) reported that symptoms of anterior knee pain were common among professional cyclists, with an annual prevalence of 36%. These findings are consistent with previous epidemiological investigations of professional cyclists (Barrios et al., 1997) and recreational cyclists (Wilber et al., 1995). More specifically, the most commonly reported knee problem is patellofemoral joint pain, often labelled ‘cyclists knee’ (Sanner and O’Halloran, 2000). Predisposing factors include im-proper saddle height i.e. too low (Bini et al., 2011; Sabeti et al., 2010), saddle position that’s too far forward (Asplund and St Pierre, 2004) and issues at the shoe/pedal interface (Schwellnus and Derman, 2005) which include prona-tion and improper foot position (Berry et al., 2012). Iliotibial Band Syndrome is arguably the second most frequently reported knee problem (Callaghan, 2005). Most commonly reported predisposing factors include improp-er saddle height i.e. too high (Burke and Pruitt, 2003; Farrell et al., 2003), anatomic abnormalities, excessive foot pronation and improper cleat position

(Asplund and St Pierre, 2004).

Chronic lower back pain (LBP) appears to be common in cycling, yet few scientific studies exist on the epide-miology and risk factors associated with LBP in cyclists (Marsden, 2010). The prevalence of LBP in cyclists has been reported as 10-60% (Marsden, 2010), up to 50% in recreational cyclists (Schulz and Gordon, 2010) and 22% in professional cyclists (Clarsen et al., 2010). Factors for the development of LBP have been linked with increased training loads (Schulz and Gordon, 2010), improper cycle set-up i.e. low handlebars provoking increased trunk flexion (Schulz and Gordon, 2010), and improper saddle level/tilt (Bressel and Larson, 2003; Marsden, 2010).

The most commonly reported overuse hand injury is chronic ulnar nerve com-pression, a condition termed ‘Cyclist’s Palsy’ (Slane et al., 2011); the medi-an nerve is less commonly involved (Schwellnus and Derman, 2005). Ulnar and median nerve compression has been reported amongst both experi-enced and inexperienced cyclists (Ken-nedy, 2008; Slane et al., 2011), in long distance cyclists (Akuthota et al., 2005) and mountain bikers (Patterson et al., 2003; Sabeti et al., 2010). Symptoms of ulna nerve compression typically present as numbness and/or paresthesia in the fourth and fifth finger as a result of sustained pressure on the hypothenar eminence (Kennedy, 2008). It would appear the simple solution is to reduce pressure on the hypothenar eminence. Often, this can be achieved by simple adjustments to body position, designed to unload hand pressure on the handle-bars (Patterson et al., 2003; Schwell-nus and Derman, 2005), or by regular changes in hand position (Slane et al., 2011), or by wearing padded gloves (Slane et al., 2011). A nose down saddle (forward tilt) tends to redistribute the body-weight, moving it forwards, as a result this can lead to increased pressure on the hands and hypothenar emi-nence. Likewise, hand pressures tend to increase when the handlebars are lower

Page 13

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

than the saddle (Patterson et al., 2003).

Complaints associated with increased perineum saddle pressures are common in male (Carpes et al., 2009; Sommer et al., 2010) and female cyclists (Partin et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2010). A re-cent review which yielded 62 pertinent articles, reported complaints in 50-91% of cyclists (Leibovitch and Mor, 2005). The consensus of literature links the aforementioned complaints with pro-longed saddle pressure (Bressel et al., 2010; Bressel and Larson, 2003; Partin et al., 2012), more specifically, excessive body weight and saddle design (Carp-es et al., 2009; Schrader et al., 2008), saddle level/tilt (Bressel and Larson, 2003) and improper handlebar position (Carpes et al., 2009; Partin et al., 2012), most of which can be alleviated by proper body position facilitated by cycle set-up.

Figure 2 - Setting Saddle Height

Saddle heightThe effect of saddle height on perfor-mance and injury prevention is arguably the most important and fundamental adjustment of cycle set-up and body position (Bini et al., 2011; Peveler, 2008; Peveler and Green, 2011). The reported benefits of optimum saddle height include optimum muscle length for optimal power output (Peveler, 2008) and alleviation of compressive pressures across the patellofemoral joint (Wanich et al., 2007). For years there have been many unsubstantiated theories and multiple methods of deter-mining optimal saddle height. Argu-

ably, the two most common methods are Hamley and Thomas (1967) using 109% inseam leg length and Holmes et al (1994) who recommend a 25º-30º knee angle flexed. Recent studies have established that saddle height based on inseam leg length is problematic as they tend to yield highly variable knee angles (Peveler et al., 2005a: Peveler et al., 2007), possibly due to anthropometric differences i.e. femur, tibia, foot dif-ferences (Bini et al., 2011), or perhaps mechanical differences i.e. variation in pedals, cleats, shoes and saddles (Dins-dale and Dinsdale, 2014). Consensus of recent studies universally recommends an optimum saddle height for trained and untrained cyclists of 25º-35º knee angle set by goniometer, for anaerobic power output (Peveler et al., 2007; Pe-veler and Green, 2011), aerobic power output and cycling economy (Peveler, 2008; Peveler and Green, 2011). More specifically, Peveler (2008) and Pevel-er and Green (2011) found VO2 was significantly lower at a saddle height of 25º knee angle compared with 35º knee angle. In summary, a saddle height set by goniometer (Fig. 2) to a knee flexion angle 25º-35º is desirable for reducing knee injuries and improving performance in trained and untrained cyclists. However, recreational cyclists, mountain-bikers and long distance road cyclists that prefer a more relaxed and comfortable ride may opt for 30º-35º. Conversely, competitive cyclists in search of optimum power output and lower oxygen uptake when racing over relative short distances are more likely to opt for 25º-30º (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 - Optimum Saddle Height

Figure 4 - Saddle Tilt

Saddle tiltGenerally, the conventional saddle (with nose) should be set horizontally ‘level’, or with a slight tilt (±3º), using a spirit level (Fig. 4) (Burke and Pruitt, 2003). Women often prefer the front to be angled slightly downwards to reduce pressure on the perineal area (Partin et al., 2012) and in some cases of LBP (Bressel and Larson, 2003). Cyclists adopting the classic aero position, with a highly flexed trunk, often prefer a more drastic forward tilt (≤10º), or prefer to use a ‘no-nose’ saddle (Din-sdale and Dinsdale, 2011). Cyclists that adopt an upright trunk position, typically mountain-bike and recreation-al cyclists often prefer a level saddle or slightly tilted backwards (Burke and Pruitt, 2003). This position can also help alleviate pressure on the ulnar nerve by redistributing the body weight (Schwellnus and Derman, 2005).

Aero positionRiding in an aero position where the trunk is highly flexed can have conse-quences (Dinsdale, 2014). The increased lumbar flexion places increased stress on intervertebral discs and demands high levels of spinal flexibility, combined with adequate pelvic and core stabili-ty (McHardy et al., 2006; Schulz and Gordon, 2010). Moreover, this extreme forward position can increase pressure on the anterior perineum (Carpes et al., 2009; Sommer et al., 2010). Recom-mendations to reduce stresses within the anterior perineum and thus improve comfort include adjusting saddle tilt downwards (i.e., nose down) (Carpes

14 Page

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

et al., 2009; Spears et al., 2003), using a saddle width sufficiently wide to support the ishial tuberosities (Sommer et al., 2010), using a ‘holed’ saddle for men (Bressel and Larson, 2003; Potter et al., 2008) but found none effective for women (Potter et al., 2008) or using a ‘no-nose’ saddle (Bressel and Larson, 2003; Schrader et al., 2008).

Figure 5 - Foot misalignment

Shoe/pedal interfaceOften neglected, undervalued, or misunderstood by cyclists, coaches and bikefitters alike (Dinsdale, 2014), the shoe/pedal interface can influence power output (Dinsdale and Williams, 2010) and predispose the cyclist to overuse injuries (Asplund and St Pierre, 2004). The make-up and function of the shoe/pedal interface dictate how effectively pedal forces are transmitted down the cranks; and how deleterious forces can be transmitted up the kinetic chain to adversely impact on vulnerable musculoskeletal structures, principal-ly the knee (Dinsdale and Dinsdale, 2011). During one hour of cycling, a cyclist can average 5,000 pedal revolu-tions; the smallest amount of misalign-ment whether anatomic, biomechanical or mechanically related, can lead to injury and reduced performance (As-plund and St Pierre, 2004). Foot mis-alignment (Fig. 5) is prevalent amongst cyclists, potentially affecting >85% of riders (Garbalosa et al., 1994). Studies have demonstrated that the repetitive forces applied to the pedal during the

downstroke (power-phase) are of a sig-nificant magnitude reaching 300-500 N (Farrell et al., 2003). These forces oc-cur at the foot/pedal interface, reaching 3 times body mass during sprinting and equal to body mass during steady-state cycling. Hennig and Sanderson (1995) found that as power outputs increased so did the amount of foot pronation (foot misalignment). Hannaford et al (1986) reported that under light or moderate loads a simple longitudinal arch support or rearfoot support might be adequate, but when the load in-creases and the force is placed directly under the metatarsal heads, the foot will collapse in the direction that allows the forefoot to become parallel with the pedal. Moreover, forefoot varus exag-gerates the amount of foot pronation which can lead to greater knee mis-alignment and potentially greater power loss (Sanner and O’Halloran, 2000). Therefore, controlling foot misalign-ment is crucial and can prove beneficial. It has been postulated that improper foot positioning may contribute to knee injury in cyclists. To investigate this, Berry et al (2012) performed a study to assess the effect of changing the foot position at the shoe/pedal interface on quadriceps muscle activity, knee angle, and knee displacement in cyclists. The authors found that by altering the foot position to either 10 degrees inversion or 10 degrees eversion, knee angle and knee displacement can be significantly influenced. Berry et al concluded by suggesting that clinically, subjects with a foot-type classified as pronating may benefit from some degree of forefoot inversion wedging. The above high-light the potential problems, and thus the opportunities, that the shoe/pedal interface has to offer.

Summary and conclusionBody position unequivocally affects comfort, overuse injury and perfor-mance - over the full range of cycling disciplines and abilities. For optimum outcome, cycle set-up and subsequent body position should reflect disci-pline-specific objectives. Moreover, bikefitters, physios, coaches, and cyclists

should approach man-and-machine as a single integrated unit, ideally working together as a multi-disciplinary team.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank Matt Bottrill (National Champion cyclist) and Brian Hall (photographer) for their consent in supply and use of images.

ReferencesAkuthota, V., Plastaras, C., Lindberg, K., Tobey, J., Press, J., and Garvan, C. (2005) The effect of long-distance bi-cycling on ulnar and median nerves: an electrophysiologic evaluation of cyclist palsy, American Journal of Sports Med-icine, 33(8):1224-1230

Ashe, M., Scroop, G., Frisken, P., Amery, C., Wilkins, M., and Khan, K. (2003) Body position affects perfor-mance in untrained cyclists, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 37:441-444

Asplund, M.D., and St Pierre, P. (2004) Knee pain and bicycling, The Physician and Sports Medicine, 32:23-30

Barrios, C., Sala, D., Terrados, N., and Valenti, J. (1997) Traumatic and overuse injuries in elite professional cyclists, Sports Exercise and Injury, 3:176-179.

Berry, A., Phillips, N., and V. Spark-es, V. (2012) Effect of inversion and eversion of the foot at the shoe-pedal interface on quadriceps muscle activity, knee angle and knee displacement in cycling, Journal of Bone and Joint Sur-gery, British Volume 94.SUPP XXXVI: 61-61

Bini, R., Hume, P., and Croft, J. (2011) Effects of bicycle saddle height on knee injury risk and cycling performance, Sports Medicine, 41(6)463-476

Bini, R., Hume, P., and Croft, J. (2012) Cyclists and triathletes have different body positions on the bicycle, European Journal of Sports Science, DOI: 10.1080/17461391.2011.654269

Page 15

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

[Accessed 22.11.2013]

Bressel, E., Nash, D., and Dolny, D. (2010) Association between attributes of a cyclist and bicycle seat pressure, Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7:3424–3433

Bressel, E., and Larson, B. (2003) Bicycle seat designs and their effect on pelvic angle, trunk angle, and comfort, Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports and Medicine, 35(2):327-332

Burke, E., and Pruitt, A. (2003) Body positioning for cycling, in E. Burke (ed.) High-Tech Cycling, USA: Human Kinetics, pp. 69-92

Callaghan, M.J. (2005) Lower body problems and injury in cycling, Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 9:226-236

Carpes, F., Dagnese, F., Kleinpaul, J., de Assis, M., and Bolli, M. (2009) Bicy-cle saddle pressure: Effects of trunk position and saddle design on healthy subjects, Urologi Internationalis, 82:8-11

Clarsen, B., Krosshaug, T., and Bahr, R. (2010) Overuse Injuries in Professional Road Cyclists, American Journal of Sports Medicine 38(12):2494-2501

Dinsdale, N.J., and Dinsdale, N.J. (Miss) (2011) The benefits of anatom-ical and biomechanical screening of competitive cyclists, sportEX dynamics, 28:17-20

Dinsdale, N.J. (2012) Musculoskeletal Screening of Competitive Cyclists prior to Cycle set-up, Conference presenta-tion – unpublished. 40th Annual Pedal Power Conference, Association British Cycling Coaches, Coventry, 2012

Dinsdale, N.J., and Williams, A.G. (2010) Can forefoot varus wedges enhance anaerobic cycling performance in untrained males with forefoot varus? Journal of Sport Scientific and Practical Aspects, 7(2):5¬-10

Dinsdale, N.J., and Dinsdale, N.J. (Miss) (2014) Modern-day Bikefit-ting can offer proactive therapists new opportunities, sportEX dynamics, 39:25-32

Farrell, C., Reisinger, K., and Tillman, M. (2003) Force and repetition in cy-cling: possible implications for iliotibial band friction syndrome, The Knee, 10:103-109

Garbalosa, J.C., McClure, M.H., Cat-lin, P.A., and Wooden, M. (1994) The frontal plane relationship of the fore-foot to the rearfoot in an asymptomatic population, Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 20:200-206

Hamley, E., and Thomas, V. (1967) Physiological and postural factors in calibration of the bicycle Ergometer, Journal of Physiology, 8(2):119-121

Hannaford, D.P.M., Moran, G.T., and Hlavac, A. (1986) Video analysis and treatment of overuse knee injury in cycling: a limited clinical study, Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery, 3:671-678

Hennig, E.M., and Sanderson, D.J. (1995) In-shoe pressure distributions for cycling with two types of footwear at different mechanical loads, Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 11:68-80

Herndon, J.H., Rorabeck, C.H., Spen-gler, D.M., Hanley, E.D., Weinstein, S.L., Gelberman, R.H., Stern, P.J., Primis, L., and Simon, M.A. (2010) Ergometer cycling after hip or knee replacement surgery: a randomized controlled trial, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 92(4):814-822

Hoevenaar, M., Wendel-Vos, W., Spijkerman, A., Kromhout, D., and Verschuren, W. (2011) Cycling and sports, but not walking, are associated with 10-year cardiovascular disease incidence: the MORGEN Study, Euro-pean Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 18:41-47

Holmes, J., Pruitt, A., and Whalen, N. (1994) Lower extremity overuse in bicycling, Clinical Sports Medicine, 13(1):187-205

Hreljac, A., Marshall, R.N., and Hume, P.A. (2000) Evaluation of lower extremity overuse injury potential in runners, Medicine & Science in Sports and Exercise, 32(9):1635-1641.

Kennedy, J (2008) Neurologic injuries in cycling and bike riding, Neurological Clinics, 26(1):271-279

Leibovitch, I. and Mor, Y. (2005) The vicious cycling: bicycling related urogenital disorders, European Urology, 47(3):277-286

Marsden, M. (2010 Lower back pain in cyclists: a review of epidemiology, pathomechanics and risk factors: review article, International SportsMed Jour-nal 11(1):216-225

McHardy, A., Pollard H., and Fernan-dez, M. (2006) Triathlon injuries: A review of the literature and discussion of potential injury mechanisms, Clinical Chiropractic, 9:129-138

O’Brien, T. (1991) Lower extremity cycling biomechanics: a review and theoretical discussion, Journal of Amer-ican Podiatric Medical Association, 81(11):585-592 Oja, P., Titze, S., Bauman, A., de Geus, B., Krenn, P., Reger-Nash, B., and Kohlberger, T. (2011) Health benefits of cycling: a systematic review, Scandina-vian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sport 21(4):496-509

Partin, S., Connell, K., Schrader, S., LaCombe, J., Lowe, B., Sweeney, A., Reutman, S., Wang, A., Toennis, C., Melman, A., Mikhail, M., and Guess, M. (2012) The bar sinister: Does han-dlebar level damage the pelvic floor in female cyclists? Journal of Sexual Medi-cine, 9:1367–1373

16 Page

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

Patterson, J., Jaggars, M., and Boyer, M. (2003) Ulnar and median nerve palsy in long-distance cyclists: A prospec-tive study, American Journal of Sports Medicine, 31(4):585–589

Peveler, W., and Green, J. (2011) Ef-fects of saddle height on economy and anaerobic power in well trained cyclists, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(3):629-633

Peveler, W. (2008) Effects of saddle height on economy in cycling, The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(4):1355-1359

Peveler, W., Pounders, J., and Bishop, P. (2007) Effects of saddle height on anaerobic power production in cycling, Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 21(4):1023-1027

Peveler, W., Bishop, P., Richardson, M., and Smith, J. (2005a) Comparing methods for setting saddle height in trained cyclist, Journal Exercise Phys-iology online 8(1):51-55 [on-line] Available from; http://www.asep.org/files/PevelerSaddle.pdf [Accessed December 2013]

Peveler, W., Bishop, P., Smith, J., and Richardson, M. (2005b) Effects of training in an aero position on metabol-ic economy, Journal Exercise Physiology online 8(1):44-50 [on-line] Available from; http://www.asep.org/files/Peveler.pdf [Accessed December 2013]

Potter, J., Sauer, J., Weisshaar, C., Thelen, and Ploeg, H. (2008) Gender differences in bicycle saddle pressure distribution during seated cycling, Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 40(6):1126-1134

Pruitt, A. (2003) Body positioning for cycling, in E. Burke (ed.) High-Tech Cycling, USA: Human Kinetics

Sabeti, M., Serek, M., Geisler, M., Schmidt, M., Pachtner, T., Ochsner, A., Funovics, P., and Graf, A. (2010) Over-use Injuries Correlated to the Moun-

tain Bike’s Adjustment: A Prospective Field Study, The Open Sports Sciences Journal, 3:1-6

Sanner, W.H., and O’Halloran, W.D. (2000) The biomechanics, etiology, and treatment of cycling injuries, Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Asso-ciation, 90(7):354-376

Schrader, S., Breitenstein, M., and Lowe, B. (2008) Cutting off the nose to save the penis, Journal of Sexual Medi-cine, 5(8):1932-1940

Schulz, S., and Gordon, S. (2010) Recreational cyclists: The relationship between low back pain and training characteristics, International Journal of Exercise Science, 3(3):79-85

Schwellnus, M.P., and Derman, E.W. (2005) Common injuries in cycling: Prevention, diagnosis and manage-ment, South African Family Practice, 47(7):14-19

Silberman, M. R. (2012) Bicycling inju-ries, Current Sports Medicine Reports, 12(5):337-345Slane, J., Timmerman, M., Ploeg, H., and Thelen, D. (2011) The influence of glove and hand position on pressure over the ulnar nerve during cycling, Clinical Biomechanics, 26(6):642-648

Sommer, F., Goldstein, I., and Korda, J. (2010) Bicycle Riding and Erectile Dysfunction: A Review, The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(7):2346-2358

Spears, I., Cummins, N., Brenchley, Z., Donohue, C., Turnbull, C., Burton, S., and Macho, G. (2003) The effect of saddle design on stresses in the perineum during cycling, Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(9):1620-1625

Taimela, S., Kujala, U.M., and Oster-man, K. (1990) Intrinsic risk factors and athletic injuries, Sports Medicine, 9(4):205-215

Wanich, T., Hodgkins, C., Columbier,

J.A., Muraski, E., and Kennedy, J.G. (2007) Cycling injuries of the lower extremity, Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 15:748-756

Wheeler, J.B., Gregor, R.J., and Broker, J.P. (1995) The effect of clipless float design on shoe-pedal interface kinetics and overuse knee injuries during cy-cling, Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 11:119-141

Wilber, C., Holland, G., Madison, R., and Loy, S. (1995) An epidemiological analysis of overuse injuries among rec-reational cyclists, International Journal of Sports Medicine, 16(3):201-206.

Page 17

curious to learn more about the ma-chines we ride, why they are - as they are, along with the applied technology. It is likely that many readers will ride on what is commonly called a compact frame, namely one where the top tube slopes down towards the rear wheel. I wonder how many of those cyclists are aware that Mike Burrows was instru-mental in creating this design ? Mike remains a competitive in the area of re-cumbent events. Those who were pres-ent at Pedal Power 2013 when he gave the Ramin Minovi Memorial Lecture on “In search of the perfect machine” will know that he is an entertaining speaker with an engaging personali-

Mike Burrows is an engineer whose name is synonymous with at least two areas of bicycle design – the radical Lotus Sport on which Chris Board-man won Olympic Gold in 1992, later establishing a new World Hour Record and the creation of a string of interest-ing and successful designs of recumbent machines. This book was first published some years back but it’s contents remain relevant today. It addresses ergonomics, aerodynamics, materials, wheel and tyre design, transmissions, brakes, suspen-sion systems and many more factors which bear upon bicycle design and performance. I have no hesitation in rec-ommending Bicycle Design to anyone

ty. If you missed Pedal Power, buy the book and it may just help complete your education.

Bicycle Design is available from Snow-books Ltd or BHPC.com Price £12 including post and packing. ISBN 13-978-1-905005-680

Book Review: “Bicycle Design” by Mike Burrows

by Elvet Bridges

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

Cycling Club. Or his progress towards winning the most prestigious time trials both at home and abroad. Sean being the first British rider to win a time trail stage in the Tour de France and six year later his time trialling abilities resulted in him wearing the yellow jersey. And so, the story unfolds, the unchallenged role of rouleur in the most demanding races. Someone who enjoyed riding ridiculous distances in training- even when managing teams. Sean provides frank accounts of his childhood and the family he grew up in, his marriage and its breakdown. Later, his health prob-lems. All very revealing, but perhaps the most remarkable chapter is Pippa’s Story – Chapter 13. Pippa being his former wife and who he evidently con-

The book opens with a statement of fact, Sean has been to the Tour de France 20 times, as a competitor twelve times and eight as a Director Sportif. He describes in detail the demands of the job and the personalities involved both when employed by Sky and previously as a rider with US Postal, Motorola, 7-Elev-en. These being only four of the many professional teams he raced for, accumu-lating enormous experience along the way. Latterly, managing the Sky team when Bradley Wiggins won the Tour in 2012. Experiences described in detail including his highly successful career in the amateur ranks. But this book pro-vides much more than a highly detailed account of his early introduction to cy-cling, starting with the East Grinstead

tinues to rely on for advice and guidance. I recommend that you buy this book and learn more not just about a world class rider, but the lifestyle of Sean Yates during this period in his life. I fancy we will hear more of this man in the future.

Published by Bantam Press, price £18.99. ISBN 978-0-593-07193-9

18 Page

Book Review: “It’s all about the bike” by Sean Yates

by Lewis Hall

The Journal of Cycle Coaching: Issue No 1:2014

Costa Daraudaby James Smith

Riding wise from the attached map you can see you are well catered for from coastal roads right through to mountain passes from the beaches near Cambrils right into the Monstant Natural park. We stayed for 6 days and were able to ride a different route daily.

We had a guide daily plus a supporting a vehicle provided by Costa Duarada cycling, this makes a huge difference when you have had enough of cycling or suffer a major mechanical. All in all I would recommend visiting this region as it really is an undiscovered cycling region.

A Trip to an uncharted land…. Well Costa Daurada at least.

I recently had the pleasure of joining Cycling Costa Daurada near Barcelona, my group stayed at the very nice Cam-brils park an all inclusive resort perfect for tired cyclists after a long day in the saddle. The Costa Daurada is one of the main tourist destinations on the Mediterranean. It is a rich and varied territory, with a long coastline bathed in sunshine and an interior dotted by quiet villages and cultivated fields. The Costa Daurada is much more than sun, sea and sand. It offers its visitors a wide range of leisure activities, culture, nature and history in an ideal setting of peace and tranquillity, perfect for holidays with the whole family.The map indicates the relative location of the Cambrils resort around 90 min-utes south of Barcelona and about 20 minutes outside of Reus and Taragona.

Cambrils Park is an immaculately presented campsite. The roads are lined with palm trees and pampas grass, and emplacements are located near the first-class facilities, of which the lagoon-style pool complex is undoubt-edly the focal point. We attended in early spring so the campsite was empty apart from some very noisy youngsters on football training camps. We stayed in two bedrrom villas which were well decorated with a dishwasher.

Page 19

The Journal is calling for papers and contributions for its quar-terly journal.

The scope of the journal is broad, including features on: psy-chology, physiology, nutrition, technical/equipment, tacti-cal, individual training plans and coach-rider relationships for example.

The papers and contributions range from being relative-ly technical and scienti c, to case studies of 1:1 coaching, through to recipes for a healthy meal.

In addition we are not averse to the odd ‘political’ comment and would consider papers that have a ‘point’ to make in an objective manner.

The Journal of Cycle Coaching also publishes book and pa-per reviews, written in an analytic and critical manner. So you can either send us a book review, or send us your book for review.

The membership and additional readership embrace many aspects of cycle sport from track, road, time trial, cyclo-cross, speedway, MTB, BMX, sportives and touring.

Currently, 800 copies of the Journal are distributed every quarter to an International audience of coaches and riders. Potential contributors should therefore focus on the practical coaching aspects of their work in relation to this audience.

Contributions can vary in length so we can accommodate long and short pieces in a variety of ways. The editor retains the right to edit the length and style, but not the content of the work to t the journal. Final copy will be agreed between both parties before publishing. Please send your contributions either by post or email to the editor.

The Journal of Cycle Coaching

The Journal of Cycle Coaching

Call for papers and contributionsCall for papers and contributions