Irish Field Monuments.pdf

-

Upload

nguyendung -

Category

Documents

-

view

233 -

download

0

Transcript of Irish Field Monuments.pdf

Irish FieldMonuments

Contents

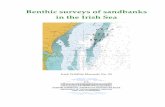

aAerial view of a ringfort atLisnabin, Co. Westmeath. On theright in the next field a ringbarrow,crowned with a bush, can beseen beside a pond, (photo - LSwan). The cover illustration isbased on this photograph.

DUBLINPUBLISHED BY THESTATIONERY OFFICE

To be purchased throughany Bookseller, or directlyfrom theGOVERNMENTPUBLICATIONS OFFICE,SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE,MOLESWORTH STREET,DUBLIN 2.

Text by C. Manning.

Design and cover illustration byAislinn Adams. Other illustrationsby P. Coffey.ISBN 0 7076 0035 9PDF 2004

2 Introduction

3 Ringforts

4 Souterrains

5 Crannogs

6 Hillforts and Promontory forts

8 Early ecclesiastical enclosures

10 Linear earthworks and roadways

11 Fulachta Fiadh andHorizontal mills

13 Megalithic tombs

15 Mounds, Cairns and Barrows

17 Stone circles, Alignments,Standing stones and Rock art

18 Medieval earthworks

20 Medieval buildings

21 Miscellaneous monuments

22 Sites not showing on the surface

23 Archaeological excavation

24 Relevant authoritiesFurther reading

IntroductionBy any standard the Irish countrysideis very rich in physical remains of thepast in the form of archaeologicalsites and monuments. This remarkable heritage and resource has,however, come under increasingthreat in the past couple of decadesand as a result many fine monuments,containing much valuable informationabout the past, have been destroyedor badly damaged.

An archaeological survey of the countryis in progress and Sites and MonumentsRecords have been produced on a countybasis. These consist of lists of knownarchaeological sites accompanied bycopies of the 6" maps with the sitesmarked on them. The ultimate aim is toproduce a detailed published survey on

every county but this will take manyyears. In the meantime archaeologicalinventories have been published for anumber of counties as well as thedetailed survey for Co. Louth. Theomission of a site from the maps or fromany of these surveys does not mean thatit is not important as many sites have yetto be discovered.

This booklet has been written for thelayman, particularly in the hope that itwill assist farmers and others involved indevelopments, that cause grounddisturbance, to identify ancientmonuments and thereby secure theirpreservation. It is also aimed at youngpeople to make them aware of the richheritage of monuments in Ireland and ofthe need to safeguard it for futuregenerations. Emphasis is placed on themonument types most frequentlyencountered or most likely to gounrecognised rather than on the moreimpressive and well-known monumentsmany of which are already protected.For information on these better knownsites and for general information on thearchaeology of Ireland the reader isreferred to the books listed on page 24.

E' *

\ —

M O

\

T 5w

HL E

,0 I .

f \ /—r

1 /..*. ./ 1

7 7^

ti -

/

7 ,hi•

\ /

\

••

* *

•

:

|

/

" " "

"V

v

—a

- • - •

v l -\"\ \ \

\/

//

/ /Z-A/

EA section of an Ordnance Survey6 inch map showing ringforts, arectangular moated site and amotte. (Co. Tipperary; sheet 27.By permission of the Government,Permit No. 4472).

RingfortsThese are undoubtedly the commonestmonuments on the landscape and theones most often under threat. They arefound in every county and are known byvarious names (fort, rath, dun, lios etc.).Basically the ringfort is a spacesurrounded by an earthen bank formed ofmaterial thrown up from a fosse or ditchimmediately outside the bank. Generallythey vary from 25-50 metres in diameter,are usually circular but can also be oval or

mA cashel or stone fort atLeacanabuaile, Co. Kerry, afterexcavation and conservation. Theconserved lower portions of dry-stone buildings can be seenwithin the fort. (photo -C. Brogan).

bank and ditch but such examples arerarer than the simple type. In some areas,especially in the west of Ireland, amassive stone wall enclosed the site inplace of a bank and ditch. This type ofringfort is called a caher, cashel or stonefort and well preserved examples mayhave terraces and steps in the inner faceof the wall. Most of these stone forts havebeen heavily robbed of stone to buildroads or field fences and often onlytraces of the wall survive.

Both types of ringfort were erected asprotected enclosures around farmsteadsmainly during the Early Christian period(c. 500 - 1100 AD). The dwelling housesand other buildings were generally dry-stone or timber built and the remains ofstone structures are sometimes visible. It

is only during archaeological excavationthat the traces of wooden structures canbe found. Sometimes, especially inpermanent pasture land or rocky terrain,ancient field systems, associated withringforts, survive.

Diagram of a souterrain orunderground passage, a,Entrance. b, Passage. c,Corbelled Chamber. These aresometimes found duringploughing, quarrying or housebuilding.

SouterrainsA feature often found in ringforts is anunderground passage or souterrain(popularly known as a cave or tunnel).They are usually built of stone but canalso be tunnelled into rock or compactclay or gravel. Souterrains are sometimesfound apparently independent of anyenclosure and are also found in EarlyChristian ecclesiastical enclosures. Theywere used as places of refuge andpossibly also for storage and can beencountered unexpectedly duringploughing, bulldozing or quarrying.These structures can be unsafe,especially if recently uncovered andshould be treated with extreme caution.

Tree covered crannóg inKilcorran Lough, Co. Monaghan.(photo - C. Brogan).

\EA ringfort in hilly terrain withremains of an internal rectangularhut at Ballymakellett, Co. Louth.(photo - C. Brogan).

Interior view of a souterrainlooking from the chamber outalong the passage at Benagh, Co.Louth. (photo - C. Brogan).

CrannogsThese are small circular man-madeislands in lakes or marshland servingthe same function as ringforts and usedduring much the same period. Crannogswere made up of layers of material suchas lake-mud, brushwood and stones witha palisade of closely-set wooden stakesaround the perimeter to consolidate thestructure and act as a defensive barrier.The stumps of these stakes are oftenvisible, preserved by the water loggedconditions, which also preserve otherwooden and leather objects makingthese sites particularly interesting toarchaeologists. Drainage schemes oftenleave crannógs high and dry on theforeshore in which situation they can bedifficult to recognise.

Hillforts &Promontory fortsSome early forts were built makingmaximum use of naturally defendedpositions such as low hills andpromontories. Hillforts are largeenclosures delimited by a bank and ditch

or a stone wall enclosing the top of a hill. Insome cases there are a number of lines ofdefence widely separated from eachother. These must have been tribal ratherthan family units and were used mainlyduring the Iron Age (c. 300 BC - 500 AD).

Many suitable cliff headlands around thecoast and some inland were defended bythe erection of earthen ramparts ormassive stone walls cutting off the neck ofthe promontory. These promontory forts.which vary greatly in size, usually havethe element dun in their names and aregenerally assigned to the Iron Age.

fflThe promontory fort called DunDúchathair on high cliffs onInishmore, Aran Islands, Co.Galway. A massive dry-stone wallwith an entrance at one enddefends the interior where theremains of a few structuressurvive close to the wall. (photo -C. Brogan).

aAn aerial view of the massivehillfort at Mooghaun, Co. Clare.Three large concentric wallsenclose this hilltop and there arealso two smaller enclosures ofringfort size which appear to belater in date. (photo - L. Swan).

EarlyecclesiasticalenclosuresA large proportion of the old church sitesand graveyards around the country are onthe sites of Early Christian ecclesiasticalfoundations which were originally

surrounded by large enclosures, oftencircular or oval in plan, and usually farmore extensive than the survivinggraveyards. In some instances the entireenclosing bank, ditch or stone wallsurvives but more often the line of theenclosure is only indicated by curving fieldboundaries or cropmarks or lowearthworks visible only from the air. Aswell as an early church and burial groundthese enclosures contained the dwellingsand workshops of a communitysometimes approaching the size of atown. As the buildings were generally of

~-,0KEarly ecclesiastical enclosure atMoyne, near Shrule, Co. Mayo.An ancient wall here encloses anarea much larger than the presentgraveyard Note the earthworksforming further divisions within theenclosure. (Photo - L Swan).

The early monastic site of Lusk,Co. Dublin. Some of the roads ofthe present-day village follow thecurve of the early enclosure.Centrally placed in the graveyardis a 19th-century church attachedto a medieval tower whichincorporates an early roundtower. (photo - L. Swan).

wood nothing survives in the enclosuresabove the ground while in the graveyardsthere is often a ruined medieval parishchurch. These enclosures vary indiameter from c. 30m to as large asc. 400m.

In some cases there is no survivinggraveyard or merely an old graveyardwithout any inscribed headstones. Suchsites were often used for the burial of

unbaptised children during the last fewcenturies and are known by variousnames (killeen, ceallunach etc.).Bullauns (boulders with round basin-shaped hollows in them) are often foundon early church sites while Holy Wellsmay be situated close to them.Professional archaeological adviceshould be sought before considering anyworks or development within 100 metresof an old graveyard.

Linearearthworks &roadwaysLarge banks with an accompanying ditchor ditches running for great distancesacross the countryside probably acted asterritorial boundaries and impediments tothe driving off of cattle. Such linearearthworks are generally only wellpreserved for short stretches and the bestknown example is the Black Pig's Dyke,

parts of which survive in countiesMonaghan, Cavan and Leitrim. Otherlinear earthworks are the Worm Ditch,the Dane's Cast and the Claidhe Dubh.

Ancient roadways can also be foundrunning for long distances but, becausethey have for the most part beenobliterated by modern roads orcultivation, they are often now only inevidence across mountain terrain oracross bogs where they are known astoghers. Many toghers were built of timberplanks laid lengthways on crossbeamsand kept in place by pegs driven into thebog. Well preserved examples have beenfound during turfcutting.

Togher or timber roadway acrossa bog at Corlea, Co. Longford asuncovered by archaeologicalexcavation. This togher was builtin 148 B.C. during the Iron Age.(photo - B. Raftery).

10

Fulacht Fiadh at Rathlogan, Co.Kilkenny. It has the normalhorseshoe-shaped mound and itslocation in marshy ground closeto a stream is typical.(photo - T. Condit).

Fulachta Fiadh &Horizontal millsAncient cooking places called FulachtaFiadh are one of the least well-knownmonument types, often not recognised asancient features and seldom marked onthe maps. They usually survive as smallhorseshoe-shaped mounds made up

mainly of small pieces of blackened stoneand situated close to a water source or inmarshy or formerly marshy ground. Arectangular pit, lined with wooden planksor stone slabs to form a trough, isinvariably found during archaeologicalexcavation under the open part of thehorseshoe-shaped mound. Water washeated in the trough by rolling hot stonesinto it from a fire close by. It has beenproved by experiment that water can beboiled in this way and meat cooked in it.The hot stones often shattered on contactwith the water and the mound was formedas a result of shovelling the broken stonesout of the trough so that it could be used

11

again. The timber trough or part of itoften survives in the damp conditionsusually prevailing on these sites.

The practice of using these sites persistedfrom at least the Bronze Age down to thehistoric period and the method of usingthem is described in early texts. Theycan occur in groups and are frequentlyencountered during land reclamationand field drainage.

Another monument type found in similarsituations is the horizontal mill. Theseare of rare occurrence and portions ofwooden structures, displayingsophisticated carpentry techniques, havebeen revealed during excavation. Thesemill sites have been dated to the EarlyChristian period but are generally notrecognisable on the surface.

Diagram of a Fulacht Fiadh.a, Crescent - shaped moundb, Section through wooden troughand moundc, View of trough.

Aerial view of Deer Park orMagheraghanrush Court-tomb,Co. Sligo. This fine example hasa central elongated court withburial chambers opening off eachend. Most of the cairn has beenrobbed over the centuries leavingonly the large structural stones.(photo - C. Brogan).

12

Megalithic tombsAs the word 'megalithic' signifies, thesestructures were built of large stones.Basically they consist of a burial chamberor chambers, built of large uprights androofed over in stone, originally containedwithin a cairn (heap of stones) or a claymound but accessible through anentrance. In most cases the cairns havebeen largely robbed of stone leavingonly the ruined chamber popularlyreferred to as a dolmen, giant's grave,druid's altar or Diarmuid and Gráinne'sBed. Many are given these or similarnames on the 6 inch O.S. map whileothers are not marked at all. Megalithictombs can be divided into four mainclasses: Court-tombs, Portal-tombs,Passage-tombs and Wedge-tombs.

Court-tombs are found mainly in thenorthern half of the country and are socalled because they generally have acurved forecourt at the entrance to thetomb at one end of a long straight-sidedcairn. As with all megalithic tombs thecairn may be partially or totally robbedand often only the upright stones of thechamber survive.

Portal-tombs are found mainly in thenorthern part of the country and in SouthLeinster and Waterford. Some of the wellpreserved examples are among the mostimpressive megalithic tombs in thecountry. Their name is derived from the

13

two large upright stones forming theentrance or portal of the chamber. Theoften massive capstone is supported onthese and on the lower back and sidestones. It is seldom that any remains of acairn survive.

Passage-tombs are found mainly inconcentrations, known as cemeteries,of which that in the bend of the Boynearound Newgrange is the most famous. Inplan they consist essentially of a roundmound or cairn with a passage leadingfrom the edge to a chamber within. Manyof them are sited on hilltops and in somecases the structural stones of the tombare decorated. These along with thePortal and Court-tombs belong to theNeolithic or New Stone Age period(c. 4000 - 2000 BC).

The fourth tomb type, the Wedge-tomb,has been assigned to the succeedingEarly Bronze Age (after 2000 BC). Thistype is more widespread than the otherswith many occurring in Munster whereother tomb types are very rare. Thesetombs originally consisted of arectangular chamber often narrowing anddeclining in height towards the back(hence the name) and roofed with slabs.The cairn can be round, oval or D-shaped.

14

Portal-tomb at Kilclooney More,Co. Donegal. This photographshows the matched pair of tallportal stones at the entrance andthe large and impressivecapstone. (photo - C. Brogan).

Wedge-tomb at Caheraphuca,Co. Clare. As their name impliesthese tombs are often wedgeshaped both in plan and section.(photo C. Brogan).

Passage-tomb cairns on amountain at Carrowkeel, Co.Sligo. These are part of acemetery or group of passage-tombs at Carrowkeel. (photo - C.Brogan).

Mounds, Cairns &BarrowsCircular mounds or cairns of roundedprofile and varying greatly in size areknown in most parts of the country. Theseare generally burial mounds but maycover any one of a number of differenttypes of burial (Passage-tombs, or otherNeolithic or Early Bronze Age burials). It is

sometimes possible to classify robbed ordenuded examples if part of the structureis exposed.

The practice of burying in cists, box-likestructures made of stone slabs, is firstfound in the Neolithic period. These largecists containing one or two burialsaccompanied by decorated Neolithicpottery are found covered by roundmounds and to date occur only in thesouthern part of the country.

Early Bronze Age cists are found alsounder round mounds but are mostlysmaller than the Neolithic ones and anumber of them are usually found in the

15

one mound. The burials in them can beeither cremated or unburnt and decoratedpottery, either food vessels or urns, isgenerally found with them. Similar burialsare also found without the protection of acist but accompanied by the pottery. EarlyBronze Age burials can also occurindividually or in flat cemeteries wherethere is no mound. Such burials are oftenfound unexpectedly during sand andgravel quarrying.

Often difficult to see on the ground aresmall mounds with encircling ditch andbank known as ringbarrows. These canvary in size from about 4 metres across toas much as 20 metres. Usually the bank isoutside the ditch and sometimes there islittle or no mound within. They can occurin clusters and are often not marked onthe 6 inch map. Excavation has shownthat they are burial monuments usuallycontaining cremations of Bronze or IronAge date.

Isolated cist graves are generallyfound by accident when a ploughor bulldozer removes thecapstone. They contain burialswhich are usually cremated, andoften a pottery vessel. Diagram ofa cist grave: a. with capstone; b.without capstone.

aA ringbarrow at Rathnarrow, Co.Westmeath with archaeologicalexcavation in progress around it.(photo - C. Brogan).

-

16

Ogham inscribed standing stoneon Dunmore Head, at thewesternmost tip of the DinglePeninsula, Co. Kerry. (photo - F.Moore).

Stone circle at Bohonagh, Co.Cork. (photo - C. Brogan).

Stone circles,Alignments,Standing stones& Rock artThe stone circles which are found incertain parts of the country such as theWest Cork/South Kerry area wereapparently used for ritual purposes. Somecircles have a dozen or more uprightstones while the smallest ones have onlyfive stones and measure 2 to 4 metresacross.

Alignments or straight lines of three ormore closely set standing stones are

known especially in areas where stonecircles occur. Both types date from theBronze Age.

Single standing stones known by variousnames (gallán, dallán, liágán, long stoneetc.) are of more widespread occurrencebut are not necessarily all of one period orone purpose. Some have been shown tomark prehistoric burials while others mayhave served some other commemorativeor ritual function. They vary in heightconsiderably, up to a maximum of about 5metres. Some smaller upright stones canhave crosses inscribed on them fromEarly Christian times or Oghaminscriptions. The latter is an ancientalphabet consisting of dots and strokescut along the edge or edges of a stone.The bulk of these ogham stones are foundin Counties Cork, Kerry and Waterford.

17

They are often found lying flat or reusedas lintels in souterrains or other laterstructures.

Rock outcrops and natural boulders weresometimes inscribed with cup and circles,concentric circles and other designsduring the Bronze Age.

MedievalearthworksThe most impressive of these is the motte,popularly called a moat, which cansurvive as a very large steep-sidedmound of earth with a flat top. These wereconstructed during the early phases of theAnglo-Norman settlement in the 12th and13th centuries. Originally there wouldhave been a wooden tower and palisadeon top and many examples have anattached enclosure called a bailey whichwould have contained houses and otherbuildings. During an attack the motte itselfwould have served as the main strongpoint and last resort.

In certain areas Anglo-Norman settlersconstructed square or rectangularenclosures called moated sites. Their

Rock art on outcropping rock atKealduff Upper, Co. Kerry.(photo - C. Manning).

aMotte at Clonard, Co. Meath.(photo - C. Brogan).

18

Moated site at Grove, Co.Kilkenny. The fosse or moat stillfills with water during wetweather. This site is not markedon any edition of the OrdnanceSurvey map. (photo - T. Barry).

The deserted medieval town ofNewtown Jerpoint, Co. Kilkennyas shown on the OrdnanceSurvey 6 inch map (1839). At thattime the streets, house sites andplots were still visible on theground.

main defensive feature was a wide (oftenwaterfilled) fosse with an internal bankand sometimes a slight external bank. Aswith ringforts, which they resemble inscale, these enclosures protected ahouse and outbuildings usually built ofwood.

The Anglo-Normans also founded townsand villages in the areas they settled andwhile some of these are still importantcentres others have dwindled in size orbecome deserted. These desertedsettlements can cover large areas ofground and where grazing only has takenplace they can survive as complexsystems of small banks which cansometimes be rationalised as the remainsof houses, outbuildings and propertyboundaries arranged around a street orstreets. Often there is an old church andgraveyard nearby and a castle, motte ortower house.

».-t

/ 7•••• /a. A » -**

v- \

MedievalbuildingsMedieval castles come in a great varietyof shapes and sizes and are usuallymarked on the 6 inch O.S. maps. Alsomarked as castles on the maps are thetall structures of the later Medievalperiod (15th-16th centuries) which aremore correctly referred to as towerhouses. Many of these are remarkablywell preserved.

Medieval churches and monasteries areoften surrounded by graveyards underthe care of local authorities but some areunprotected in open fields. Again theseare normally marked on the maps or areknown of locally.

Some castles and churches have beenlargely removed over the years and novisible trace or just a few humps in theground may survive. Such sites ofchurches or castles (frequently marked assuch on the maps) are of archaeologicalimportance and can yield muchinformation if properly excavated.Earthworks of a settlement or enclosureare often found surrounding or close tocastles, tower houses and churches andeven if these are not in evidence thearea surrounding any of these structuresshould not be disturbed. Professionalarchaeological advice should be soughtin defining this area.

20

Aerial view of a tower house atRockstown, Co. Limerick. Tracesof a pear-shaped enclosure orbawn can be seen enclosing thetop of the rocky knoll on which thetower house was built. (photo - C.Brogan).

Aerial view of CreeveleaFranciscan Friary nearDromahair, Co. Leitrim. The longchurch has a central tower whilethe domestic buildings were builtaround an open square cloistergarth. (photo - C. Brogan).

siA recently restored 19th-centurymill with its mill wheel on thebanks of the Funcheon atGlanworth, Co. Cork. On the cliffbehind is Glanworth Castle datingfrom the 13th to 17th centuries.(photo - C. Brogan).

MiscellaneousmonumentsThere are many other ancient monumentsin our countryside which are worthpreserving. Among these are fortifiedhouses of the 16th and 17th centuries,star-shaped artillery forts of the same

period, Martello towers, old houses andmansions of architectural interest andlandlord's follies. Of a less imposingnature are isolated house and hut sitesincluding booley huts in mountain areasand the stone-corbelled huts common inKerry called clocháns. There are alsomany interesting structures such as oldbridges, sweat houses, lime and corn-drying kilns, ice houses, pigeon housesand old light houses. A specialist studyin itself is industrial archaeology which isconcerned with industrial monumentssuch as windmills and watermills of allsorts, old factories, canals, mines, etc.

21

Sites not showingon the surfaceVery few prehistoric habitation sites havebeen found in comparison with thenumber of known burial and ritualmonuments. This is due to the fact that thehouses were generally flimsy structuresmade of wood or other perishablematerials and not normally defended by

large walls or banks. Such habitation sitesare usually found only by accident duringthe excavation of some other monumentor as a result of the finding of smallartifacts during ploughing or other landdisturbance. Any works that involveconsiderable disturbance of the groundsurface such as drainage and landimprovement works, quarrying, road andbuilding construction and pipe laying canuncover hitherto unknown sites of alltypes including monuments that had beentotally levelled prior to the first edition ofthe Ordnance Survey maps. All such findsshould be reported without delay to theChief Archaeologist (address below).

The site of a circular post-and-wattle house during excavation atLackenavorna, Co. Tipperary.This photograph illustrates howarchaeological features cansurvive in certain circumstancesvery close to the surface. (photo -C. Manning).

22

A complex series of cropmarksshowing in a field of corn in thetownland of Bracklin, Co.Westmeath. Cropmarks resultfrom buried features (such asditches or wall foundations)causing differences in cropgrowth which may be visible fromthe air. Archaeological sites withno surface features can bedetected in this way. (photo - LSwan).

Another area of work where interestingdiscoveries can be made is in the cuttingof turf both in the raised bogs common inthe Midlands and the blanket bogscovering much upland terrain especiallyin the West. Toghers (wooden trackwaysacross bogs) are the main monumenttype found in raised bogs but blanketbog can cover many types ofmonuments including megalithic tombs,cairns, stone circles, house sites andfield walls. A massive Neolithic fieldsystem associated with a court-tomband habitation sites was discovered inNorth Mayo during turf cutting.

ArchaeologicalexcavationModern archaeological excavation is ahighly skilled activity requiring muchexpertise in the recovery of the evidenceand in its interpretation and publication.Contrary to popular opinion archaeologistsdo not excavate in order to find gold orother valuable objects. Rather, theirintention is to get the maximuminformation about the past from theground. Objects found in an excavationare important principally because of theirrecorded association with other objects,structures, layers or features. For thisreason it is important that unqualifiedpersons should not undertakearchaeological excavation and if byaccident a discovery is made everythingshould be left as it is without any furtheruncovering of the object or feature or anyother disturbance of the immediate areauntil an official inspection has beenmade.

The National Monuments Acts, makes itunlawful to excavate for archaeologicalpurposes without a licence from theDepartment of the Environment, Heritage &Local Government. Their consent is alsorequired to use a metal detector for thepurpose of searching for archaeologicalobjects. Such consents are normally issuedto qualified and experience archaeologists

23

RelevantauthoritiesThe National Monuments Section,Department of the Environment,Heritage & Local Government,Dun Scéine,Harcourt Lane,Dublin 2.Telephone (01) 4117112

Reports of monuments in clanger or newdiscoveries should be directed to thesame address.Other than in licensed excavation thediscovery of ancient artefacts orarchaeological objects should bereported without dealy to:

The Director,National Museum of Ireland,Kildare St.,Dublin 2.Telephone (01) 6777444.

(see National Monuments Acts 1930-1994).

Further readingS.P. Ó Ríordáin Antiquities of the IrishCountryside (5th edition, revised byR. de Valera). Methuen 1979.

P. Harbison Guide to the NationalMonuments of Ireland.Gill and Macmillan 1975.

Historic Monuments of Northern Ireland:An Introduction and Guide.H.M.S.O. Belfast 1983.

E. Evans Prehistoric and Early ChristianIreland: A Guide. Batsford 1966.

M. Herity and G. Eogan Ireland inPrehistory. Routledge and Kegan Paul1977.

P. Harbison, Pre-Christian Ireland.Thames and Hudson 1988.

M.J. O'Kelly, Early Ireland. CambridgeUniversity Press 1989.

T.B. Barry, The Archaeology of MedievalIreland. Methuen 1987.

N. Edwards, The Archaeology of EarlyMedieval Ireland. Batsford 1990.

24