Investigating the Occurrence of Workplace Aggression of Front-line Staff of Hotel Industries in...

description

Transcript of Investigating the Occurrence of Workplace Aggression of Front-line Staff of Hotel Industries in...

International Bulletin of Business Administration ISSN: 1451-243X Issue 10 (2011) © EuroJournals, Inc. 2011 http://www.eurojournals.com

166

Investigating the Occurrence of Workplace Aggression of Front-line Staff of Hotel Industries in Penang Island by

Assigning Emotional Labor as Predictor (SEM Model)

Mohammad Hossein Motaghi-Pisheh Graduate School of Business, Universiti Sains Malaysia

11800 Penang Island, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected]

Harianto

Graduate School of Business, Universiti Sains Malaysia 11800 Penang Island, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected]

Abstract The research examined the occurrence of different categories of workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression) with emotional labor as predictors (surface acting and deep acting). Data collection was being done through survey with 186 samples of individual who work as front-line staff from various hotels located in Penang Island. In order to figure out the relationship among variables in proposed model, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is being adopted. The outcome demonstrated that surface acting is having positive and significant relationship with expression of hostility and overt aggression, but no significant relationship with obstructionism. In contrast, it also illustrated that deep acting do not have positive and significant relationship with different categories of workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression). This research stressed on the importance of using different methods (surface acting and deep acting) to perform emotional labor on the occurrence of workplace aggression. Hence, it helps to minimize behavioral problem of front-line staff during service interaction and delivering excellent service. In term of theoretical contribution, it enhances workplace aggression literature by new finding pertains to how surface acting and deep acting resulted in different categories of workplace aggression in service industry on Malaysian context. Keywords: Surface Acting, Deep Acting, Expression of Hostility, Obstructionism, Overt

Aggression, Front-line staff, Hotel Industries, Penang Island 1. Introduction As known, hotel industries in Penang Island were operated in highly competitive environment which indicated from widespread of hotel service providers throughout the city (Alan, 2007). Therefore, it is imperative for hotel industries that located in Penang Island to always seek the way to sustain and ensure the continuity of business operation. Apparently, the key success factor of hotel industry lies on

167

quality of service in order to create customer satisfaction (Panikkos & Paul, 2005; Mohr & Bitner, 1995). Basically, quality of service will be viewed from three different angles raging from “service product, service delivery, and service environment” (Rust & Oliver, 1994, p. 11).

In respect of creating excellent service delivery, hotel industries in Malaysia particularly imposed display rule for those individual who hold front-line staff position (Yuhanis, 2008). It is because of front-line staffs are the one who mainly interact with customers and the job positions “is known to be the nerve centre of a hotel” (Mohd Onn, Razlan, Dahlan, & Salleh, 2009, p. 44). As result, their attitudes, manners, behavior, and expression during performing the job task are important determinant of quality of service delivery (Barsky & Nash, 2002). In this case, display rule served a function as regulation to limit front-line staff from expressing out certain negative emotions when they are performing their task whereby they are obligated to show positive emotions expression (Steinberg & Figart, 1999).

In fact, expression of positive emotions of front-line staff might potentially improve the quality of service delivery, and eventually lead to customer satisfaction and customer intention for using particular service (Bolton, 2005; Zeithaml, Bitner, & Gremler, 2006). In turn, front-line staff must express out precisely the emotions that stated in display rule although their actual feeling of emotions differ from emotion expression at that particular time (Markus, Thorsten, & Gianfranco, 2009). Furthermore, all the time during performing the job task front-line staffs have to conform to display rule although they are dealing with irritating customers (Steinberg & Figart, 1999).

In this case, front-line staff emotion expression control process as compliance to display rule is called “emotional labor” (Hochschild, 1983). Apparently individual who hold front-line staff position have to do multi-tasking whereby they should do administrative works as well as showing positive emotions during service interaction (Johnson & Woods, 2008). To perform emotional labor, front-line staff generally used two methods which are known as “surface acting” and “deep acting” (Diefendorff, Croyle, & Gosserand, 2005, p. 339). “Surface acting” is method to demonstrate emotion expressions that in accordance to display rule by focusing to change the “outward emotional refection” (Humphrey, Pollack, & Hawver, 2008, p. 152).

On the other word, with surface acting it is unnecessary for an individual to have the particular feeling of emotion in order to present desirable emotion expressions , for instances: individual might show smile as part of compliance with organizational display rule, but interestingly he/she probably is actually having sad feeling.. In contrast, “deep acting” is way to demonstrate expected emotion expressions with changing the feeling of own emotion (Humphrey, Pollack, & Hawver, 2008). From emotional labor context, it is clear that front line staff may engage in either surface acting or deep acting in order to successfully express out positive emotions expression during performing the job-task. Since front-line staff must consistently follow display rule no matter how do they feel and customer treatment, it is believed that those individual who engage in surface acting to show positive emotion expressions are more likely frustrated (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) and encounter stress related problem (Grandey, 2003).

Due to deep acting which still required an individual to put considerable amount of effort to modify their internal feeling of emotion in order to produce expected expression, it will ultimately cause “emotional exhaustion” (Myriam, Conny, Johannes, & Dieter, 2007, p. 485). Similarly, there is an evidence indicated that “emotional exhaustion” is related to “stress” in workplace (Karatepe & Karatepe, 2010, p. 2). For different method to perform emotional labor, it can’t be denied that stress is one of negative outcome of performing emotional labor if front-line staff consistently can’t expressed out their actual emotion (Maslach & Jackson, 1981).

In this case, emotional labor performs by front-line staffs in hotel industry really give a matter of concern because it might bring contradiction emotions between expected emotions and actual feelings of an individual while performing their job (Hochschild, 1983). In fact, regardless of methods used to perform emotional labor front line-staff have to cope with stress when performing their daily task (Alicia, 2000). Besides that, there was evidence that indicated stress that arises in workplace is

168

propeller for an individual to involve in workplace aggression (Neumann & Baron, 1998). But it is still no clear whether performing emotional labor will have relation with the occurrence of workplace aggression.

To make it explicit how stress resulted in the occurrence of workplace aggression, individuals’ stress that originated from performing job task will contribute to increasing of the feeling of negative emotions (Anderson & Deuser, 2002). And, feeling of negative emotions is associated with person’ actions to undertake workplace aggression (Pcharlotte, 2005). Workplace aggression basically is “all forms of intentional harm-doing in organizations” which encompass “any act in which one individual intentionally attempts to harm another” (Neumann & Baron, 1998, p. 395). In workplace aggression perspectives, it can be divided into three categories which are “expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression” (Neumann & Baron, 1998, p. 397).

Expression of hostility is typical of “behaviors that are primarily verbal or symbolic in nature” such as: “gestures, facial expressions, and verbal assaults” (Neumann & Baron, 1998, p. 397). Meanwhile, obstructionism is kind of “(1) actions that are designed to impede an individual’s ability to perform his or her job or interfere with an organization’s ability to meet its objectives, (2) The majority of these behaviors involve passive forms of aggression” (Neumann & Baron, 1998, p. 398). Lastly, overt aggression is component of workplace violence whereby it entails to physical injury to victims such as: “attack with weapon, physical assault against person, personal property, and company property, theft” (Neumann & Baron, 1998, p. 399).

Importantly, different categories of workplace aggression differ in the term of negative effects that it brings into workplace (Pcharlotte, 2005). If workplace aggression exists among employees in workplace, it will only bring negative impact to organizations and well being of its’ stakeholders (Neumann & Baron, 1998). To date, the workplace aggression happened in almost all organizations over the places (Kathryne & Julian, 2006). In correspondent to front-line staff in hotel industry in Malaysia, the finding illustrated that on average front-line staffs who work under hotel industries in Penang Island are involved in service sabotage (Sien, 2006).

In addition, it has been found that front-line staff that being employed in hotel industries that located in Langkawi Island is also involved in workplace aggression (Shamsudin, 2003). Besides that, Faridahwati (2003; 2004) discovered that front-line staffs in hotel industries in Malaysia are involved in deviant behavior. On the other hand, Lau, Abdolali, & David (2005) research stated that the customers evaluation about quality of service delivery from hotel industries in Malaysia don’t meet exactly the criteria that they imagined. Hence, it is assumed that the occurrence workplace aggression of front-line staff in hotel industries in Malaysia is in line with customer dissatisfaction.

Given the problem that front-line staff in hotel industry in Malaysia are engage in workplace aggression, it is clear that the front-line staff behavior and emotion expression will have significant impact on customer evaluation on quality of service offering (Chu, 2002), the quality of services goes down, customer complaints, and mark down company fame (Diefendorff & Richard, 2003). For this reason, it is necessary for this research to carefully focus on examining whether emotional labors is one of predictors of workplace aggression among front-line staff in hotel industry because it is believed that job related stressor is main factor that potentially cause an individual to undertake workplace aggression (Robinson & O'Leary-Kelly, 1998). However, hotel industries will not ever overcome the occurrence of workplace aggression of front-line staff without clear clarification on the causal factors.

To reinforce on argument regarding further research on the context on workplace aggression, Bowling & Gruys (2010) p. 54 stated that “despite the growing literature and interest in CWB, there are still problems of clarity as to how to proceed with research in the area”. Moreover, the research on misbehavior in organizations is still at the beginning stage whereby it is necessary for research to identify and further do some development on its construct (Bowling & Gruys, 2010). Although it has been recognized that there are many factors contribute to the occurrence of workplace aggression, such as: social factor, situational factor, and personal factors (Neumann & Baron, 1998). Without finding

169

the real root cause, hotel industry will only take wrong actions by firing the individual who undertake workplace aggression.

Based on current literature, it is unknown that whether performing emotional labor will have relationship with the occurrence of workplace aggression. Therefore, this research will comprehensively research whether performing emotional labor through surface acting or deep acting will have relationship with the occurrence of different categories of workplace aggressions (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression). Therefore, the practical contribution of this research could significantly helps current service industry (hotels) organizations become aware of consequences of their front-line staff in using different methods when performing emotional labor on the occurrence of different categories of workplace aggression.

Thus, hotel industries are able to launch more effective program to deal with front-line staff aggression in workplace. Moreover, in support of sustainability practices this research will be helpful to educate human resources management in order to set out their strategies on how to make front line staff in service industry (hotels) able to used emotional labor effectively without resulting in any harming behavior. Finally, industry practitioners are going to benefit from the outcome of the research by knowing what the industry can do to buffer the effects of the workplace aggression in relation to emotional labor at front-line staff job function. 2. Literature Review 2.1. Workplace Aggression

Aggressive behavior can be found commonly exist among members in organization such as: shout at colleague, passing gossip, physical attacking (Neumann & Baron, 1998). Actually, the beginning stage of workplace aggression is feeling of negative emotions (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). However, past research have already clearly differentiate between aggressive behavior that linked with negative emotions namely “affective aggression” and aggressive behavior that are not related to negative emotions namely “instrumental aggression” (Neuman & Baron, 1997).

In this research, the feeling of negative emotions will be taken into account as driver of workplace aggression of front-line staff of hotel industries in Penang Island because it is assumed that the feeling of negative emotions of front-line staff is derived from result of performing emotional labor (surface acting and deep acting). As known, emotional labor that being performed by front line staff is the process to hide negative emotion away and showing positive emotion (Diefendorff, Croyle, & Gosserand, 2005). Consequently, there was research presented that the emotional labor that performed by front-line staff increased the risk of the feeling of negative emotions (Zapf, 2002).

Workplace aggression become overwhelming studied due to its negative impacts toward organizations and members inside organization like: increased in company spending on unnecessary cost and time wasted (Coco, 1998), workplace communication problem (Anderson & Pearson, 1999), fail to show up at work, decreased in dedication at work, high turnover rate, thwarted organization objectives (Pearson, Andersson, & Porath, 2000). Nevertheless, until today there is still no exact term to reflect aggressive behavior in organization because of its diversity. In the available literature pertains to aggressive behavior, we can find many terms to understand the role of aggressive behavior such as “workplace incivility, workplace violence, workplace bullying” (Pcharlotte, 2005, p. 1), and “counterproductive work behavior” (Fox, Spector, & Miles, 2001).

In this present research, aggressive behavior will not only limit to workplace violence (Neumann & Baron, 1998), it might also encompasses “expression of hostility” (Neumann & Baron, 1998), “obstructionism” (Neumann & Baron, 1998), and “covert aggression” (Neumann & Baron, 1998). Therefore, workplace aggression will be used as term for the purpose of this present research. While, a similar term with workplace aggression also can be found to reflect various of aggressive behaviors in workplace, counterproductive work behaviors is made up of set of unwanted behaviors in workplace that also inclusive workplace violence (Fox & Spector, 2005). In present research,

170

workplace aggression is “all forms of intentional harm-doing in organizations” (Neumann & Baron, 1998 p.395) which include “any act in which one individual intentionally attempts to harm another” (Neumann & Baron, 1998 p.395).

In order to integrate more component of aggressive behavior that happened in work context, Neumann & Baron (1998) p.397 has classified “workplace aggression” into three categories which are: “expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression”. Expression of hostility is “behaviors that are primarily verbal or symbolic in nature (e.g., gestures, facial expressions, verbal assaults)” (Neumann & Baron, 1998, p. 397). Expression of hostility becomes more preferable for individual to aggress in workplace and it happened most over the time in comparison to other categories of aggression (Neumann & Baron, 1998).

According to Pcharlotte (2005) p. 5 findings, “negative eye contact, negative non-verbal cues, and non-denial rumours” are most common form of expression of hostility in any organization. In addition, verbal sexual harassment occupied the second position in term of frequency of occurrence of expression of hostility (Pcharlotte, 2005). Meanwhile, obstructionism is “Actions that are designed to impede an individual’s ability to perform his or her job or interfere with an organization’s ability to meet its objectives. “The majority of these behaviors involve passive forms of aggression (withholding some behavior or resource), so they are extremely difficult to track” (Neumann & Baron, 1998, p. 398).

The most common form of obstructionism in organization is “failure to warn of physical danger, being late for meetings, intentional work slow-down” (Pcharlotte, 2005, p. 5). Overt aggression is a typical of workplace violence whereby it causes an injury such as: “attack with weapon, physical assault against person, personal property, and company property, theft” (Neumann & Baron, 1998, p. 399). In any case, if the aggressive behavior occurred in workplace, it will significantly harm whole organizations and well being of its’ stakeholders (Neumann & Baron, 1998).

Apparently, there are several variables that potentially cause workplace aggression such as: “social, situational, personal, cognitive, and attitudinal in nature” (Pcharlotte, 2005, p. 2). For social factors that lead to workplace aggression, it will include: stressful condition (Storms & Spector, 1987), multicultural workforce (Dryer & Horowitz, 1997), “normative behavior and norm violations” (Neumann & Baron, 1998, p. 403). Apart from social factors, most of studies believe that the root cause of workplace aggression is originated from individual personality traits because it may affect the way of mind and emotion of person to undertake aggressive behavior (Awadalla & Roughton, 1998; Zohar, 1999; Goulet, 1997; Anderson & Pearson, 1999; Chen & Spector, 1992; Geddes & Baron, 1997).

On the other hand, situational factor that cause workplace aggression derived from external condition such as: organization injustice (Sandy, Michelle, Manon, Niro, & Kara, 2007, p. 229), workplace revolution such as: downsizing (Brockner, et al., 1997), job-overload (Tomasko, 1990), “environmental conditions” like: poor working condition (Neumann & Baron, 1998 p.404). Regarding on how situational factor lead to workplace aggression, firstly it will cause an individual to have negative emotions and subsequently this feelings mainly arouse individual intention to carry out aggressive behavior (Sandy, Michelle, Manon, Niro, & Kara, 2007).

The most common negative emotions that lead to workplace aggression may include: the angry feelings, unhappiness, sorrow, or stressful feelings (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). In respect of how the feeling of anger relates to workplace aggression, past research indicate that human emotions possess huge power to control over mind and individual actions (Frijda, 1993). On the other hand, the feeling of angry emotion equips an individual with strong premises why they should engage in aggression (Glomb, 2002). Perhaps, another research discovered that situational factor such as: the presence of aggravation can also stir someone’ actions to aggression in workplace like: anything that prevent person to accomplish the objectives (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939), impolite or unmannered behaviors (Anderson & Bushman, 2002).

171

In present research, situational factor particularly job stressor (emotional labor) will become main focus in predicting workplace aggression because it is believed that job stressor are the main contributor to workplace aggression (Robinson & O'Leary-Kelly, 1998).

In details, emotional labor in hotel industry reflects job position that needs front-line staff to control their emotion expression that they want to show to customer. And, front line staffs are faced with only one option which has to always comply with prescribed emotion no matter they like or dislike it. So, it is clear that front line staff’ job position possess characteristics of job stressor which are high expectation and minimum control (Radmacher & Sheridan, 1995). 2.2. Emotional Labor

In today Malaysian market, the control of emotional display of front-line staff become business practice of hotel industries because of its usefulness in delivering acceptable customer services experience to customer (Bruce, Gianna, & Eric, 2006), “maintaining positive relations with customers” (Gail, 2009, p. 120), and avoiding “emotional “leakage” of boredom or frustration of customers (Gail, 2009, p. 120). Furthermore, Hochschild (1983) in his research identified that managing employee emotions in workplace are integral part of service components that helps organization to achieve competitive advantage.

Besides that, another research shows that “the manners in which interactions between employees and customers unfold constitute a principal component of a customer’s expectations and experience of service quality” (Phillips, Tsu-Wee Tan, & Julian, 2006, p. 4). Thus, it is not unusual that most of hotel industries take actions to manage their employees’ emotions by administering formal rule for their employees to always have positive emotion when dealt with customer (Hwee H, Maw D, Chee L, & Renee, 2003; Rafaeli & Sutton, 1987).

Positive emotions that come together with service offered to customer are believed to create emotional contagion which influences level of customer satisfaction (Tan, Foo, & Kwek, 2004), customer intention to buy (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1985), future loyalty (Pugh, 2001), “enhancing the organization’s public image” (Tan, Foo, & Kwek, 2004, p. 961). Meanwhile, front-line staff in hotel industry is the key element that mainly interacts with potential customer and initiates service offerings (Bruce, Gianna, & Eric, 2006). In fact, the research shows that “the interaction between service employees and customers is considered an essential part of both customers’ assessments of service quality and their relationship with the service provider” (Hennig-Thurau, Groth, & Gremler, 2006, p. 58).

And “the success of the interaction between employees and customer upon employees’ creation of an appealing, positive emotional climate” (Salman & Uygur, 2010, p. 191). Hence, most of hotel industries require their employee who occupied front-line staff job position to express positive emotions and present acceptable behavior to customer (Bolton, 2005). By the time, display rule is also being established in hotel industry in order to guide and direct front-line staff about what emotion expression are compatible during service transaction (Constanti & Gibbs, 2004). In this case, emotion of front-line staffs is fully being controlled by job role and they are obligated to develop certain ways to express their feelings as instructed by organization during performing their job.

In addition, Hochschild, (1983) p.147 ruled out that job task should be performed using “emotional labor” because the job position required: “(1) work face to face and voice to voice with the customers, (2) are required to produce a positive emotional state in customers, (3) are trained and supervised in order to provide the customers with a standardized “moment of truth” each and every time, (4) are paid with amount of money compensate for their physical work and cognitive ability”. Indeed, it can be said that front line staff job position possess high expectation of emotional labor because the task need longer time interaction with customer, larger effort to control their emotion and “greater congruity is required between different modalities (vocal tone, facial expression, and body language)” (Gail, 2009, p. 121).

172

Thus, “emotional labor” concept is highly applicable in this research because front line staff who is working under hotel industry is expected to manage their behavior and feelings according to display rule and they are compensated with wages (Abraham, 1998). And emotional labor that performed by front-line staff is mainly done at organization’ interests with the purpose to influence customer satisfaction (Hochschild, 2003). With emotional labor, a person able to demonstrate emotions according to emotions that specified into job rule (Rafaeli & Sutton, 1987). In relation to front-line staff job position in hotels industry, the company wants their employees who occupied that position to hold negative emotion expression and always show positive emotion expression.

Since employees have to comply with this specific display rule (show positive emotions) of hotels industry, employees will normally employ emotional labor with two main methods which is: surface acting and deep acting (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1993; Gosserand & Diefendorff, 2005). Surface acting take place if an individual adjust their emotion expression matched to the desired one by not showing unwanted emotion expression. In details, surface acting is the process to show expected emotions by large degree of control to their external bodily display although the emotion is not actually felt (Alicia, 2003).

Indeed, it can be done with “careful presentation of verbal and non-verbal cues such as facial expression, gestures, and voice tone” (Mann, 1997 p.10), for instances: due to fulfillment of hotel display rule, front-line staff will still show smiles to customer although he is in deep sorrow at that point of time. In this case, front line staff only managed his emotion expression to comply display rule without changing his actual state of emotion. On the other hand, a person used deep acting if only he/she can control the emotions felt at given point of time so that the desirable emotion expression will be automatically produced out (Humphrey, Pollack, & Hawver, 2008).

Actually, deep acting involves altering the current state of emotions in accordance to expected emotion. Deep acting can be done “through cognitive reappraisal of the events surrounding the emotional experience” (Daniel, Trougakos, & Weiss, 2006, p. 1054). In details, person who used deep acting will try to imagine about something coherent that could change the actual emotion felt into other emotion in order to generate out desirable emotion expression (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1993). Or he may “exhort his feelings” to generate out desirable emotion expression (Hochschild , 1983 p.39). For instance: By thinking about customer is old people a person who works as stewardess able to change his irritating feelings because of customer bad respond toward her to friendliness and helpfulness (Hochschild, 1983).

Notwithstanding the differences in actual emotions felt, both surface and deep acting can still produce out desirable emotion expression. But, deep acting will result in more genuine emotion expressions which have stronger influence toward customer compared to surface acting (Grandey, 2003). Indeed, deep acting will induce customer as perceiver to feel more pleased and comfortable as compared to surface acting (Grandey, Fisk, Mattila, Jansen, & Sideman, 2005). Furthermore, there is an evidence that prove deep acting caused emotional exhaustion (Bono & Vey, 2005), but less likely lead to emotional dissonance (Grandey, 2003).

In contrast, the past research implies that surface acting is correlated with ingenuity work behavior that makes customer less satisfied (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002). Besides that, the research also indicated that surface acting will cause the individual to feel stress, over work load, perceive their job is full of tension, and bring “stressful experiences” in prolong time (Abraham, 1998; Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Erickson & Wharton, 1997; Alicia A. , 2000, p. 101). Past research indicated that work task that consistently built emotional dissonance will significantly drive an employee to carry out “stress related behavior” (Ronald, Jeffrey, & Thomas, 2008, p. 159). Due to tendency of person as human being who always want to show their actual expression, both surface and deep acting are associated with individual level of stress in workplace (Hochschild, 1983; Gross, 1998; Gross & Levenson, 1997).

173

2.3. Hypotheses Generation

It is known that front-line staffs have to live with the feeling of negative emotions because the job position that they hold required them to interact with customer with acceptable manner and behavior (Zapf, 2002). Besides that, it is common that individual as human being is always need harmony between internal strength owned and outer expectation (Cannon, 1932). In this case, the feeling of negative emotions will interrupt the equilibrium between both of them. Hence, the negative emotions should be controlled in order to balance back the emotional experiences. Subsequently, this event may cause front line staff to feel stress due to front line staff’ jobs possess characteristics of high expectation and minimum control (Radmacher & Sheridan, 1995).

In fact, there is research mentioned that the job with characteristics of low control have significant relationship with workplace deviant (Bennett, 1998). In addition, many studies have emphasized that emotional labor that being practiced in many service organizations has lead to occupational stress (Hochschild, 1983; Hall, 1991; Wharton, 1993; Adelmann, 1995; MacDonald & Sirianni, 1996; Morris & Feldman, 1996; Pugliesi, 1999). Followed the theory of Gottfredson & Hirschi (1990), they mentioned aggression is an action that being carried out by an individual to compensate themselves therefore it become interest of most of individual. So, workplace aggression will be considered as method to cope with negative emotions and stress in workplace.

On the other hand, according to job-stress model the stressful experiences of front line staff at work, it may trigger the feeling of negative emotions and further produce “job strain” as respond to stressor (Spector, 1998). In this case, job stain will come into two forms which are psychological and behavioral (Jex & Beehr, 1991). In details, behavioral strain is actually an individual way to respond to stress by directly counter the stressor (seeking the method to solve the problem, or discuss with colleague), or make their emotion to calm down (purposely late, breaking company property, workplace aggression, and etc.) (Penney & Spector, 2002).

Thereby, this research is interested to examine whether surface acting and deep acting provide evidence that resulted in workplace aggression. And this research will consist of six main hypotheses which are:

Due to tendency of person to feel contradicted emotions is highly related with surface acting, workplace aggression will makes an individual feel comfort, better, and free from negative emotions that derived from their interaction with customer. Based on argument, it is being predicted that surface acting will have positive relationship with workplace aggression. In this perspective, workplace aggression divided into three categories which are “expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression” (Neumann & Baron, 1998 p. 397).

• HA: There is significance relationship between surface acting and expression of hostility. • HA: There is significance relationship between surface acting and obstructionism. • HA: There is significance relationship between surface acting and overt aggression.

Due to deep acting still can cause an individual to have feeling of negative emotions (Totterdell, 2002), the researcher will assume that deep acting will also have positive relationship with workplace aggression. And in this perspective, workplace aggression divided into three categories which are expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression.

• HA: There is significance relationship between deep acting and expression of hostility. • HA: There is significance relationship between deep acting and obstructionism. • HA: There is significance relationship between deep acting and overt aggression.

3. Methodology The research will be using quantitative method in order to investigate the relationship among emotional labor (deep acting and surface acting), different categories of workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression).

174

3.1. Sample

Sample for the research is derived from front-line staffs employed under hotel companies located in Penang Island. However, the unit of analysis will be individual. In collecting the sample, the researcher approach Human Resources Department of hotel industries that are willing to participate in this research. And, the researcher discussed the research purpose with human resource managers for each of hotel companies. So, they agreed to distribute the questionnaires to front-line staff. Therefore, each human resource managers of hotel industries were being provided with sufficient number of questionnaires (around 10 to 20 copies/hotel) with total of 235 questionnaires was being disseminated. Furthermore, the researcher was asked to come back and did collection when it was being contacted by particular hotel industry. By this, the researcher has collected 220 set of questionnaires. 3.2. Measurement

There are five elements involved in this research which are two from independent variable (surface acting and deep acting) and three from dependent variable (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression). Importantly, all the measurement for each variable is being taken from the designed questionnaire from published journals. In order to measure independent variable (emotional labor (surface acting and deep acting), this research adopted 11 items from Diefendorff, Croyle, & Gosserand (2005), which five items that used to measure surface acting emanated from Grandey (2003), an additional two items to measure surface acting derived from Kruml & Geddes (2000) emotive dissonance scale.

The remained four items are used to measure deep acting which comprises of three items adapated from Grandey (2003), and one item adapated from Kruml & Geddes (2000) emotive effort scale. Emotive effort is actually have same concept with deep acting because it measure the effort to present expected emotions. Moreover, these 11 items are being put in format of 5-point likert scale (“never”=1, “rarely”=2, “sometimes”=3, “often”=4, and “always”=5). Meanwhile, in order to measure the dependent variable (different categories of workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression), this research adopted modified version questionnaires from Baron & Neuman (1996).

In this questionnaire, it divided into 15 items to measure expression of hostility, 10 items to measure obstructionism, and 8 items to measure overt aggression. For all 33 items are also being put in format of 5-point likert scale (“never”=1, “rarely”=2, “occasionally”=3, “often”=4, and “very often”=5). 3.3. Data Analysis

Due to the presence of multiple predictors in current research particularly surface and deep acting and different outcome of workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression), the researcher used SPSS 19.00 and AMOS 16.0 to do statistical analysis.

In fact, the researcher makes use of statistical package for social sciences (SPSS version 19.00 for Windows) in order to perform exploratory factor analysis and reliability analysis. Moreover, the researcher performed confirmatory factor analysis and path analysis used AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures). In addition, the past research suggested that both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis should be done in order to testify particular model (Churchill, 1979). And, finally structural equation model will be employed in order to test the relationship between independent and dependent variables.

In term of exploratory factor analysis, a questions response is valid to domain and pattern of relationship among variables if all the items in each variables are acceptable if it possess coefficient of main loading above .5 and cross loading below .35 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Anderson & Gerbing, 1988), In correspondent with reliability analysis, the measurement employed in the research is

175

appropriate and good quality of scale used if Cronbach Alpha coefficient fall above .7 (Cronbach, 1946).

In respect of confirmatory factor analysis, it is used to evaluate whether the variables in present research applied the proper and correct measurement therefore it can be dependent upon (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006). There are various criteria to measure model fit that can be used. However, the model in present research can be considered overall good fit if : X2/df indicate value between 1 to 5, CFI, NFI, and TLI have coefficients above .9, and the result of RMSEA should show coefficient below .08 (Arbuckle & Wotke, 1999; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). 4. Result 4.1. Respondents’ Demographic Profile

In term of age, 47.3% out of total respondent have age categories below 25 years old. And 52.2% out of total respondent have age categories between 25 years and 50 years old, while the remained 0.5% out of total respondent has age categories above 50 years old. Meanwhile, demographic profile in correspondent with gender is obtained with 63.4% out of total respondents are females and 36.6% out of total respondents are males. In respect of marital status, the present research indicates that 30.6% out of total respondents are having families (married) whereas the remained 69.4% out of total respondents are single. Eventually, for working experiences 42.5% out of total respondents are having experiences with category less than 2 years, 27.4% out of total respondents are having experiences with category between 2 years and 8 years, and 30.1% out of total respondents are having experiences with category above 8 years. 4.2. Goodness of Measure

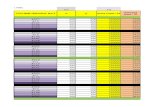

With factor analysis, items surfaceQ1 and surface Q3 are being removed from datasheet since it incorrectly measure particular domain. And, the final outcome generated show that the result is satisfying all the criteria with Kaise-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy value .868, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity significance value .000, all anti image correlation value for each item is above .8, eigenvalue with value above 1 located in 2 component, and also the main loading & cross loading criteria also being fulfilled. Table 4.2.1: Rotated Component Matrixa

Component

1 2 SurfaceQ2 .198 .605 SurfaceQ4 .269 .694 SurfaceQ5 .091 .813 SurfaceQ6 .253 .737 SurfaceQ7 .306 .736 DeepQ8 .789 .345 DeepQ9 .779 .329 DeepQ10 .839 .175 DeepQ11 .859 .175

Following the same process of factor analysis, items WAQ1EOH, WAQ5EOH, WAQ6EOH,

WAQ16OB, WAQ23OB, WAQ27OVERT are being deleted due to incorrectly measure particular domain. Eventually, the outcome 4-2-2 yielded show Kaise-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy value .913, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity significance value .000, all anti image correlation value for each item is above .8, eigenvalue with value above 1 located in 3 component, and also the main loading & cross loading criteria also being fulfilled. The reliability analysis was also being conducted in order to establish the internal consistency of the measurement used. And it is beneficial in

176

enhancing the confident of researcher for using all the items in particular scale over the time. The result of reliability analysis for all items is presented in figure 4.2-3 below: Table 4.2.2: Rotated Component Matrixa

Component

1 2 3 WAQ2EOH .846 .076 .074 WAQ3EOH .863 .024 .049 WAQ4EOH .803 .011 .051 WAQ7EOH .844 .081 .095 WAQ8EOH .871 .095 .057 WAQ9EOH .880 .038 .137 WAQ10EOH .840 .011 .206 WAQ11EOH .838 .028 .205 WAQ12EOH .854 .018 .242 WAQ13EOH .863 .031 .181 WAQ14EOH .835 .059 .242 WAQ15EOH .815 .069 .134 WAQ17OB -.010 .833 .017 WAQ18OB .037 .897 .022 WAQ19OB .066 .884 .133 WAQ20OB .037 .878 .080 WAQ21OB .096 .858 .108 WAQ22OB .075 .899 .100 WAQ24OB .076 .872 .109 WAQ25OB .005 .864 .142 WAQ26OVERT .157 .239 .630 WAQ28OVERT .088 .046 .764 WAQ29OVERT .135 .018 .734 WAQ30OVERT .073 .037 .761 WAQ31OVERT .137 .163 .475 WAQ32OVERT .205 .065 .705 WAQ33OVERT .163 .042 .790

Table 4.2.3:

Variables Number of items Cronbach’s alpha value 1 Surface Acting 5 items 0.809 2 Deep Acting 4 items 0.879 3 Expression of Hostility 12 items 0.968 4 Obstructionism 8 items 0.958 5 Overt Aggression 7 items 0.833

Confirmatory factor analysis is used to determine the models’ dimensionality, convergent, and

validity (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Subsequently, the outcome of analysis shows that x2/df (1.636) and p level (0.00). It is reflect good indication of model fit. In same way, the CFI and TFI have value above 0.9 which can be said the model fit is considered good. From point view of comparison of lack of fit, RMSEA give value 0.059 which was below 0.08 and this is represent acceptable fit of model. But, the NFI possess value 0.834 which was below 0.9. In short, the whole model can be considered good fit although the NFI value is below 0.9. Table 4.2.4:

Index Initial Coefficient X2/df 1.636 P 0.000 CFI 0.928 NFI 0.834 TLI 0.922 IFI 0.928 RMSEA 0.059

177

Figure 4.2: (Confirmatory Factor Analysis)

Surface Acting

.58

SurfaceQ7S5

.76.54

SurfaceQ6S4.74

.47

SurfaceQ5S3.68

.46

SurfaceQ4S2 .68

.29

SurfaceQ2S1.54

Deep Acting.63

DeepQ11D4

.79

.59

DeepQ10D3.77

.66

DeepQ9D2 .81

.70

DeepQ8D1.84

Expression of Hostility

.69

WAQ2EOH H1

.83

.70

WAQ3EOH H3

.84

.59

WAQ4EOH H4

.77

.70

WAQ7EOH H7

.83

.74

WAQ8EOH H8

.86

.78

WAQ9EOH H9.88

.73

WAQ10EOH H10.85 .72

WAQ11EOH H11.85.77

WAQ12EOH H12.88

.76

WAQ13EOH H13

.87

OvertAgg

Obstructionism

.63

WAQ17OB B1

.80

.76

WAQ18OB B2.87

.77

WAQ19OB B3.88 .75

WAQ20OB B4.87.73

WAQ21OB B5.86

.38

WAQ26OVERT O1

.62

.49

WAQ28OVERT O2

.70

.47

WAQ29OVERT O3.68

.47

WAQ30OVERT O4.68 .20

WAQ31OVERT O5.44

.81

WAQ22OB B6

.90

.75

WAQ24OB B7

.87

.73

WAQ25OB B8

.85

.73

WAQ14EOH H14

.86

.66

WAQ15EOH H15

.81

.49

WAQ32OVERT O6.70

.61

WAQ33OVERT O7

.78

.23

.13

.39

.67

.36

.10

.34

.25

.11

.26

4.3. Path Analysis

After being assured of goodness of the model, path analysis is used to decide whether all the hypotheses proposed should be accepted or rejected. As shown in figure 4.3 below, the proposed model will include the causal factor (different component of emotional labor (surface acting and deep acting)), and the endogenous variable (different categories of workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression).

Figure 4.3: Proposed Model Of Path Analysis Graph

Surface Acting

.57

SurfaceQ7S5

.76.55

SurfaceQ6S4.74

.46

SurfaceQ5S3.68

.45

SurfaceQ4S2 .67

.29

SurfaceQ2S1.54

Deep Acting.63

DeepQ11D4

.79

.59

DeepQ10D3.77

.66

DeepQ9D2 .81

.70

DeepQ8D1.84

.15

Expression of Hostility

.69

WAQ2EOH H1

.83

.71

WAQ3EOH H3

.84

.60

WAQ4EOH H4

.77

.70

WAQ7EOH H7

.84

.74

WAQ8EOH H8

.86

.78

WAQ9EOH H9.88

.73

WAQ10EOH H10.85 .72

WAQ11EOH H11.85.76

WAQ12EOH H12.87

.76

WAQ13EOH H13

.87

.13

OvertAgg

.02

Obstructionism

.63

WAQ17OB B1

.80

.76

WAQ18OB B2.87

.77

WAQ19OB B3.88 .75

WAQ20OB B4.87.73

WAQ21OB B5.86

eH

eB.68

.37

WAQ26OVERT O1

.61

.49

WAQ28OVERT O2

.70

.47

WAQ29OVERT O3.69

.47

WAQ30OVERT O4.69 .19

WAQ31OVERT O5.44

.81

WAQ22OB B6

.90

.75

WAQ24OB B7

.87

eA

.73

WAQ25OB B8

.85

.73

WAQ14EOH H14

.86

.66

WAQ15EOH H15

.81

.49

WAQ32OVERT O6.70

.61

WAQ33OVERT O7

.78

.38

.09

.36

.00

.05

.00

Based on various indices available in model fit like being presented in table 4-3-1, it can be concluded that the model fit is acceptable. According to Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black (1998) research, they mentioned the model is good fit if they are fulfilling at least 5 of criterias of X2/df indicate value between 1 -5, CFI is greater than 0.9, IFI is greater than 0.9, TLI is greater than 0.9, and RMSEA is less than 0.08. Therefore, the hypotheses can be tested based on this proposed model.

178

Table 4.3.1: Index Initial Coefficient X2/df 1.662 P 0.000 CFI 0.924 NFI 0.831 TLI 0.919 IFI 0.925 RMSEA 0.06

There is an established rule in order to accept particular dimension as predictor of specific

outcome (endogenous) which are critical error (C.R.) of particular variable should be more than 1.96 while p < 0.05 (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). Regression Weights: (Group number 1 - Default model)

Estimate S.E. C.R. P Label Expression of Hostility ← Surface Acting .366 .121 3.031 .002 par_33 Obstructionism ← Surface Acting .091 .129 .706 .480 par_34 OvertAgg ← Surface Acting .201 .076 2.645 .008 par_35 Expression of Hostility ← Deep Acting -.001 .102 -.013 .990 par_36 Obstructionism ← Deep Acting .047 .113 .411 .681 par_37 OvertAgg ← Deep Acting .001 .063 .015 .988 par_38

Table 4.3.2:

Hypotheses Result 1. There is significance relationship between surface acting and expression of hostility. Accepted 2. There is significance relationship between surface acting and obstructionism. Rejected 3. There is significance relationship between surface acting and overt aggression. Accepted 4. There is significance relationship between deep acting and expression of hostility. Rejected 5. There is significance relationship between deep acting and obstructionism. Rejected 6. There is significance relationship between deep acting and overt aggression. Rejected

5. Discussion The present research is being conducted to figure out whether independent variables, particularly emotional labor (surface acting and deep acting) will have positive relationship with different categories of workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression). From the statistical outcome, it is given that emotional labor that being performed by front line staff through surface acting have positive relationship with expression of hostility, and overt aggression. But, it has no significant relationship with obstructionism. In contrast, deep acting is being discovered have no relationship on the occurrence of different categories of workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression). Thereby, the discussion will be further described in details as followed: 5.1. The Effect of Surface Acting and Expression of Hostility

In fact, in this initial discussion surface acting of front-line staff in hotel industry context will be observed in relation to workplace aggression particularly expression of hostility. Expression of hostility is “antagonistic behaviours that are primarily verbal or symbolic in nature” (Angela & Donald, 2005, p. 258)

179

As known, surface acting involved modifying external expression without changing on how the emotions felt of someone (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1993). Due to the negative impact surface acting, individual might sometimes faced contradiction emotions whereby it influenced on individual psychological states with increase the feeling of negative emotions (Zapf, 2002) and makes them perceive frustration and stress over the time (Abraham, 1998; Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Erickson & Wharton, 1997; Alicia, 2000). On the other word, surface acting can be assumed as workplace stressor that situational in nature which caused an individual ends up in building the feeling of negative emotions, frustration, and stress (Fox, Spector, & Miles, 2001).

At the same time, based on Penney & Spector (2002) the feelings of negative emotions are main causes that stimulate individual to undertake workplace aggression. To date, there is no research that attempt to research the direct relationship between surface acting and different categories of workplace aggression. So, it is still lack of evidence to prove the relationship between surface acting and different categories of workplace aggression. Meanwhile, this research demonstrated that surface acting has positive and significant relationship with expression of hostility (C.R. (2.87 > 1.96); p (0.04 < 0.05)). This result is almost the same with Myriam, Conny, Johannes, & Dieter (2007) research which found that surface acting have positive relationship with counterproductive work behavior particularly interpersonal deviance.

Basically, interpersonal deviance refers to behavior that being aimed to physical and psychological harm people in organization (Michael, Remus, & Erin, 2006). Besides that, Schat, Frone, & Kelloway (2006) figure out that those people who are holding position in customer service are more likely involved in workplace aggression in comparison with other professional profession, like: lecturer. In particular, the underlying reason of the occurrence of workplace aggression might be due to surface acting creating negative emotions that interrupt the balance between body and soul of a front-line staff when their actual emotions are inexpressible (Cannon, 1932).

In turn, rationally front-line staff needs to do something that associated with their body and soul in order to gain back the stability of their feelings. Since workplace aggression able to makes front line staff feeling better, it becomes appealing way to mitigate the feeling of negative emotions (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990). Meanwhile, there is “affective event theory” that tried to explain the whole scenario of the occurrence of workplace aggression and its potential causes (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). When front line staff consistently hides the feelings negative emotions, it may cause stressful conditions that triggered “affective reactions” from front-line staff and resulting in “affect-driven behavior”.

In details, affective reactions here can be anger emotions, consequently workplace aggression is one form of “affect-driven behavior” (Berkowitz, 1993; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996; Buss, 1961). In workplace aggression perspectives, expression of hostility become an individual choices to carry out aggressive act if there are many people in organization that able to monitor on their behavior and what they have done (Bjorkqvist, Osterman, & Lagerspetz, 1994). Moreover, the employers in Malaysia are not really concern about the expression of hostility that happened among their employees (Sien, 2006). The companies don’t even give response by having regulation that imposed strict punishment to the occurrence of expression of hostility.

As consequences, when front line staff chose to used surface acting as part of fulfilling their job responsibilities to show organization expected emotions expression, it is undeniable that they will engage in workplace aggression particularly expression of hostility. In fact, “expression of hostility” of front line staff in present research will only include 12 items from Baron, Neuman, & Geddes (1999) p. 288 which are “staring, dirty looks, or other negative eye contact, belittling someone’s opinions to others, giving someone “silent treatment”, flaunting status by acting in superior or condescending manner, criticizing or attacking someone’s protégé, failing to deny false rumors about others, purposely leaving the work area when others enter, holding others or their work up to public ridicule, sending unfair negative information about others to superior in the company, making negative or obscene gestures toward others, delivering unfairly negative performance appraisals, and interrupting others when they are speaking”.

180

5.2. The Effect of Surface Acting and Obstructionism

Similarly, surface acting of front-line staff in hotel industry context will be observed in relation to workplace aggression particularly obstructionism. Obstructionism in this research refers to “behaviors intended to obstruct or impede the performance of co-workers or supervisors” (Angela & Donald, 2005 p. 258). And, the result of statistical analysis shows that surface acting has positive relationship with obstructionism but not significant (C.R. (0.703 < 1.96); p (0.482 < 0.05)).

This is giving an evidence of surface acting that being performed by front-line staff will have no effect on the occurrence of obstructionism. Although past literature have not yet discovered this type of relationship, this findings is being supported by the fact that high supervision over front-line staffs in hotel industry in Penang Island (Faridahwati, 2003). Therefore, whenever front-line staffs are emotionally unbalanced, they will never engage in obstructionism. 5.3. The Effect of Surface Acting and Overt Aggression

For workplace aggression that associated with overt aggression, surface acting are being found to have positive and significant relationship with it. Overt aggression in this research refers to “behaviors that are typically thought of as workplace violence” (Angela & Donald, 2005 p. 258). It is surprising that the result of statistical analysis shows that surface acting has significance positive relationship with overt aggression instead of obstructionism (C.R. (2.396 > 1.96); p (0.017 < 0.05)). Due to nature of human beings, if an individual want to carried out aggression toward others most of them will option for typical of aggressive behavior that able to cause severe damage to victims (Bjorkqvist, Osterman, & Lagerspetz, 1994).

So, it is clear that overt aggression will become preference most of individual since it’s possess highest categories of harmful result like: attacking, murdering/killing, and etc (Bjorkqvist, LAgerspetz, & Kaukiainen, 1992).Another past research also reiterated that most of employees in organization prefer to engage in overt aggression in comparison with other form of aggression (Spivey & Prentice-Dunn, 1990). According to the employees view, overt aggression provides them a remedy to feel that human beings are equal treated (Skarlicki & Folger, 1997) . However, the occurrence of workplace violence is not considered as new phenomena, and it happened in almost companies throughout in world irrespective of location, working environment, and job position (Chappell & DiMartino, 1998).

Meanwhile, workplace violence also has been found to happened in Malaysian workplace (Rohana & Faridahwati, 2006; Rahman & Shamsudin, 2000), which indicated from “11,851 sexual assault cases happened at the Malaysian workplace between year 1997 and year 2001” (ILO press release 06/33) (Glenn, 2010). Furthermore, Ahmad (2009) also found workplace violence occurred within education insitituation in Malaysia (UUM). And, Hala (2009) founded that 5% of employees in particular health care industry perceive the occurrence of workplace aggression. Since, surface acting may cause front-line staff to have abundant of the feeling of negative emotions that makes them very unease, therefore, they might perform workplace aggression particularly overt aggresssion.

In addition, when front-line staff involved in overt aggression, they are not care about what are the consequences of their act anymore because the feeling of negative emotions have reached its peak level as result of performing surface acting. And, “overt aggression” of front line staff when performing surface acting in present research comprise of 7 items that adapted from Baron, Neuman, & Geddes (1999) p. 288 which are “physical attack or assault, damaging or sabotaging company property that other need to work, attack with a weapon, threats of physical violence, failing to take steps that would protect others welfare or safety, stealing or removing company property needed by others to work, destroying mail or messages needed by others. In short, if front-line staff used surface acting to perform emotional labor, they are likely to engage in expression of hostility and overt aggression in order to regain the balance between their body and soul”.

181

5.4. The Effect of Deep Acting and Different Categories of Workplace Aggression

In deep acting perspectives, a person is controlling on internal feeling of negative emotions in order to generate expected emotions expressions (Hochschild, 1983). In the event that front-line staff in hotel industries used deep acting to perform emotional labor, they will able to show their original emotion expression to customer (Grandey, 2003).

In respect to present research, the statistical analysis of deep acting gives contradictory result with surface acting, which stated that front-line staff who used deep acting to perform emotional labor will never engage in different categories of workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression). In addition, this research presented that deep acting has positive but not significant relationship with expression of hostility (C.R. (0.037 < 1.96); p (0.971 > 0.05)), obstructionism (C.R. (0.307 < 1.96); p (0.759 > 0.05)), and overt aggression (C.R. (0.083 < 1.96); p (0.934 > 0.05)). Even though deep acting were never been observed directly in relation to workplace aggression, this findings is still considered valid since deep acting will never cause someone to have contradiction emotions felt (Grandey, 2000).

On the other words, deep acting will bring lesser feeling of negative emotions in comparison with surface acting (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1993). And the individual does not necessary to suppress their actual emotion because they are displaying the expression that in line with expected emotion expression (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002). To reinforces current research arguments, deep acting also being found profoundly useful to produce high quality of service (Grandey, 2003) and bring high job satisfaction of employees (Bono & Vey, 2005). 6. Limitations Apparently, the present research also has some limitations. First of all, the sample are being drawn from front-line staff of service industry particularly hotels that located in Penang Island. And, it is believed the result of this research might not be applicable in the front-line staff of companies that established in other location. Furthermore, workplace aggression is not only occurred among front-line staff of hotel industry instead it happened in almost front-line staff in other industry like: manufacturing, hospitality, banking, and etc (Vardi & Weitz, 2004). Indeed, the working situation and job task might vary between companies in different sectors. Therefore, future research can be done in other business sector or different job position that required emotional labor.

Besides that, it is believed that the working expectation and responsibilities between services organization that belong to private are differs with service organization that belong to public (Aryee, Budhwar, & Chen, 2002). As consequences, future research should be emphasized on the occurrence of workplace aggression in service organization that in public sector. Furthermore, the present research conducts the data collection during particular period. And, front-line staff might sensitive to the time particularly when they want to perform workplace aggression because they might have proper planning before launching their aggressive act (Henle, 2005). With strategic and better planning, the aggressive act can be profoundly harm the organization as whole (Aquino, Galperin, & Bennett, 2004; Griffin & O'Leary-Kelly, 2004; Vardi & Weitz, 2004).

So, future research of emotional labor and different categories of workplace aggression should be conducted in different data collection manners like: collected the information periodically. And, the researcher will better understand and identify the front-line staff actual level of aggressiveness in relation to emotional labor with this concept of collecting information periodically. On the other hand, for the purpose of examining whether emotional labor is one of main predictor of the occurrence of different categories of workplace aggression, the researchers has not include other variable such as: individual personality as one of predictors of workplace aggression as well.

So, it is need for future research considering other important variables aside from emotional labor. Besides that, it is being recognized that other significant variable also play important role in mediating or moderating the relationship between independent and dependent variables, such as: job

182

satisfaction, individual personality (Lau, Au, & Ho, 2003), locus of control, abusive supervision (Jones & Kavanagh, 1996). So, it is suggested that future research should take into account how all of these variables have impact toward emotional labor (surface acting and deep acting) and workplace aggression (expression of hostility, obstructionism, and overt aggression). 7. Conclusions Finally, this research has shown significant relationship between surface acting and different categories of workplace aggression particularly expression of hostility and overt aggression. But at the same time, the research also shows that deep acting will have no relationship with different categories of workplace aggression. Therefore, it is very important for service organization to achieve service excellence by carefully selecting individual at front-line staff position that perform emotional labor by using deep acting in order to minimize the possibilities of the occurrence of difference categories of workplace aggression. It is very hope that this research will be beneficial for human resource management in hotel industry to improve on how to imposed emotion control of their front-line staff by taken into account the methods of performing emotional labor. References [1] Abraham, R. (1998). Emotional dissonance in organizations; a conceptualization of

consequences, mediators, and moderators. Leadership and Organization Development Journal , 137-146.

[2] Adelmann, P. (1995). Emotional labor as a potential source of job stress. In S. Sauter, & L. (. Murphy, Organizational risk factors for job stress (pp. 371-381). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

[3] Ahmad, M. (2009). A research on workplace violence factors in University Utara Malaysia. Kedah: Universiti Utara Malaysia.

[4] Alan, S. (2007). Turnover intentions of hotel managers: Investigating the influence of organizational justice, psychological contract violation and affective commitment. Universiti teknologi MARA, Malaysia: Unpublished Master Dissertation.

[5] Alicia, A. (2000). Emotion Regulation in the workplace: A New Way to Conceptualize Emotional Labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 5, 95-110.

[6] Alicia, A. (2003). When "THE SHOW MUST GO ON": Surface Acting and Deep Acting as Determinants of Emotional Exhaustion and Peer-Rated Service Delivery. Academy of Management Journal , 86-96.

[7] Anderson, C., & Bushman, K. (2002). Human Aggression. Annual Review of Psychology , 53, 27-51.

[8] Anderson, C., & Deuser, W. (2002). Human Aggression. Annual Review of Psychology , 53, 27-51.

[9] Anderson, J., & Gerbing, D. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin , 103 (3), 411-423.

[10] Anderson, L., & Pearson, C. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiralling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review , 452-472.

[11] Angela, R., & Donald, W. (2005). Sex Differences in Workplace Aggression: An Investigation of Moderation and Mediation Effects. Aggressive Behaviour , 31, 254-270.

[12] Aquino, K., Galperin, B., & Bennett, R. (2004). Social status and aggressiveness as moderator of the relationship between interactional justice and workplace deviant. Journal of Applied Pschology , 1001-1029.

183

[13] Aryee, S., Budhwar, P., & Chen, Z. (2002). Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organization justice and work outcomes: Test of Social Exchange Model. Journal of Organization Behavior , 23 (2), 267-285.

[14] Ashforth, B., & Humphrey, R. (1993). Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity. Academy of Management Review , 18, 88-115.

[15] Awadalla, C., & Roughton, J. (1998). Workplace violence prevention: The new safety focus. Professional Safety , 43 (12), 31-35.

[16] Bagozzi, R., & Phillips, L. (1982). Representing and testing organizational theories: A holistic construal. Administrative Science Quarterly , 27 (3), 459-489.

[17] Baron, R., & Neuman, J. (1996). Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence of their relative frequency and potential causes. Aggressive Behavior , 22, 161-173.

[18] Baron, R., Neuman, J., & Geddes, D. (1999). Social and personal determinants of workplace aggression: Evidence for the impact of perceived injustice and the Type A Behavior Pattern. Aggressive Behavior , 25, 281-296.

[19] Barsky, J., & Nash, L. (2002). Evoking emotion: affective keys to hotel loyalty. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly , 39-46.

[20] Bennett, R. (1998). Perceived powerlessness as a cause of employee deviance. In R. Bacharach, Griffin, & A. O'Leary-Kelly, Dysfunctional behavior in organizations: Violent and deviant behavior (pp. 221-239). Stamford, Connecticut: JAI Press.

[21] Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

[22] Bjorkqvist, K., LAgerspetz, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1992). Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Develop mental trends in regard to direct an indirect aggression. Aggressive Behavior , 18, 117-127.

[23] Bjorkqvist, K., Osterman, K., & Lagerspetz, K. (1994). Sex differences in covert aggression among adult. Aggressive Behavior , 20, 27-33.

[24] Bollen, K. (1989). Structural equations with latent variable. New York: Wiley. [25] Bolton, S. (2005). Emotion Management in the Workplace. London: Palgrave. [26] Bono, J., & Vey, M. (2005). Toward understanding emotional management at work: A

quantitative review of emotional labor research. In C. H¨artel, W. Zerbe, & N. Ashkanasy, Emotions in organizational behavior (pp. 213-233). NJ: Erlbaum: Mahwah.

[27] Bowling, N., & Gruys, M. (2010). Overlooked issues in the conceptualization and measurement of counterproductive work behavior. Human Resource Management Review , 20, 54-61.

[28] Brockner, J., Wiesenfeld, B., Stephan, J., Hurley, R., Grover, S., Reed, T., et al. (1997). The effect on layoff survivors of their fellow survivior reactions. Journal of Applied Psychology , 27, 835-863.

[29] Brotheridge, C., & Grandey, A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspective of "people work". Journal of Vocational Behavior , 60, 17-39.

[30] Bruce, P., Gianna, M., & Eric, L. (2006). Managing tourism and hospitality services: theory and international applications. CABI Publishing Series.

[31] Buss, A. (1961). The psychology of aggression. New York: Wiley. [32] Cannon, W. (1932). The wisdom of the body. New York: W.W. Norton. [33] Chappell, D., & DiMartino, V. (1998). Violence at Work. Geneva: International Labor Office. [34] Chen, P., & Spector, P. (1992). Relationships of work stressors with aggression, withdrawal,

theft, and substance use. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology , 65 (4), 177-184.

[35] Chu, K. (2002). The Effects of Emotional Labor on Employee Work Outcomes. Balcksburg: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

[36] Churchill, G. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Reserach , 16 (1), 64-73.

184

[37] Coco, M. (1998). The new war zone: The workplace. S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal , 63 (1), 15-21.

[38] Constanti, P., & Gibbs, P. (2004). Higher education teachers and emotional labour. International Journal of Educational Management , 243-249.

[39] Cronbach, L. (1946). Response sets and test validity. Educational and Psychological Measurement , 6, 475.

[40] Daniel, J., Trougakos, J., & Weiss, H. (2006). Episodic Processes in Emotional Labor: Perceptions of Affective Delivery and Regulation Strategies. Journal of Applied Psychology , 91 (5), 1053-1065.

[41] Diefendorff, J., & Richard, E. (2003). Antecedents and consequences of emotional display rule perception. Journal of Applied Psychology , 284-294.

[42] Diefendorff, J., Croyle, M., & Gosserand, R. (2005). The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. Journal of Vocational Behavior , 66 (2), 339-359.

[43] Dollard, D., Doob, L., Miller, N., Mowrer, O., & Sears, R. (1939). Frustation and aggression. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

[44] Dryer, D., & Horowitz, L. (1997). When do opposites attract? Interpersonal complementarity versus simalirity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 72, 592-603.

[45] Erickson, R., & Wharton, A. (1997). Inauthenticity and depression: Assessing the consequences of interactive service work. Work and Occupations , 24, 188-213.

[46] Faridahwati, M. (2004). Are you listening? Researching and Understanding Organization Misbehaviour among hotel employees in the Malaysian context. Unpublished doctoral thesis Lancaster University .

[47] Faridahwati, M. (2003). Workplace deivance among hotel employees: an exploratory survey. Malaysian Management Journal , 7 (1), 17-33.

[48] Fornell, D., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equations model with unobserved variable and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research , 18, 39-50.

[49] Fox, S., & Spector, P. (2005). Counterproductive work behavior: Investigation of actors and targets. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

[50] Fox, S., Spector, P., & Miles, D. (2001). Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior , 59, 291-309.

[51] Frijda, N. (1993). Moods, emotion episodes, and emotions. In M. Lewis, & J. Haviland, Handbook of emotions (pp. 381-403). New York : Guilford.

[52] Gail, K. (2009). Emotional labour and strain in "front-line" service employees: Does mode of delivery matter? Journal of Managerial Psychology , 24 (2), 118-135.

[53] Geddes, D., & Baron, R. (1997). Workplace aggression as a consequences of negative performance feedback. Management Communication Quarterly , 10 (4), 433-455.

[54] Glenn, F. (2010). Workplace violence towards a global standard for workplace conduct. Toronto: The Canadian Initiative on Workplace Violence.

[55] Glomb, T. (2002). Workplace anger and aggression: Informing conceptual models with data from specific encounters. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 7, 20-36.

[56] Gosserand, R., & Diefendorff, J. (2005). Emotional display rules and emotional labor: The moderating role of commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology , 90, 1256-1264.

[57] Gottfredson, M., & Hirschi, T. (1990). General Theory of Crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

[58] Goulet, L. (1997). Modelling aggression in the workplace: The role of role models. Academy of Management Executive , 11 (2), 84-86.

[59] Grandey, A. (2000). Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 5, 95-110.

185

[60] Grandey, A. (2003). When 'the show must go on': Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal , 46 (1), 86-96.

[61] Grandey, A., Fisk, G., Mattila, A., Jansen, K., & Sideman, L. (2005). Is "service with a smile" enough? Authencity of positive displays during service encounters. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 96, 38-55.

[62] Griffin, R., & O'Leary-Kelly, A. (2004). An introduction to the dark side. In R. Griffin, & A. O'Leary-Kelly, The dark side of organizational behaviour. San Francisco: Josey-bass.

[63] Gross, J. (1998). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 74 (1), 224-237.

[64] Gross, J., & Levenson, R. (1993). Emotional suppression: Psychology, self-report, and expressive behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 970-986.

[65] Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

[66] Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6 ed.). NJ, USA: Pearson International Edition.

[67] Hala, A. A. (2009). Motivation and its effect on the performance on nurses in ARAMCO health care. Penang: Open University Malaysia.

[68] Hall, E. (1991). Gender, work control, and stress: A theoretical discussion and an empirical test. In J. Johnson, & G. (. Johansson, The psychosocial work environment: Work organization, democratization and health (pp. 89-108). Amityville: Baywood, NY.

[69] Henle. (2005). Predicting workplace deviant from the interaction between organizational justice and personality. Journal of Managerial Issues , 17 (2), 247-263.

[70] Hennig-Thurau, T., Groth, M., & Gremler, D. (2006). Are All Smiles Created Equal? How Emotional Contagion and Emotional Labor Affect Service Relationships. Journal of Marketing , 70, 58-73.

[71] Hochschild, A. (2003). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling (Twentieth anniversary edition). Berkley: University of California press.

[72] Hochschild, A. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feelings. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[73] Humphrey, R., Pollack, J., & Hawver, T. (2008). Leading with emotional labor. Journal of Managerial Psychology , 23, 151-168.

[74] Hwee H, T., Maw D, F., Chee L, C., & Renee, N. (2003). Situational and dispositional predictors of displays of positive emotions. Journal of Organization Behavior , 24, 961-978.

[75] Jex, S., & Beehr, T. (1991). Emerging theoretical and methodological issues in the research of work-related stress. Res. Personnel Hum. Res. Manage. , 9, 311-365.

[76] Johnson, M., & Woods, R. (2008). Recognizing the emotional element in service excellence. Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly , 49(3), 310-316.

[77] Jones, G., & Kavanagh, M. (1996). An experimental examination of the effect of the individual and situational factors on unethical behavior intentions in the. Journal of Business Ethics , 15 (5), 511-523.

[78] Kamil, B., Shamsudin, M., & Idris, M. (2009). Predicting Compliance Intention on Zakah on Employment Income in Malaysia: An application of Reasoned Action Theory. Jurnal Pengurusan , 28, 85-102.

[79] Karatepe, O., & Karatepe, T. (2010). Role Stress, Emotional Exhaustion, and Turnover Intentions: Does Organizational Tenure in Hotels Matter? Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism , 9, 1-16.

[80] Kathryne, E., & Julian, B. (2006). Predicting and Preventing Supervisory Workplace Aggression. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 13-26.

186

[81] Kruml, S., & Geddes, D. (2000). Catching fire wthout burning out: Is there an ideal way to perform emotional labor? In N. Ashkanasy, C. Haertel, & W. (. Zerbe, Emotions in the workplace: Research, theory and practice (pp. 177-188). Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

[82] Lau, P. M., Abdolali, K., & David, Y. (2005). Service Quality: A Research of the Luxury Hotels in Malaysia. Journal of American Academy of Business , 7 (2), 46-55.

[83] Lau, V., Au, W., & Ho, J. (2003). A qualitative and quantitative review of antecedents of counterproductive work behavior in organizations. Journal of Business and Psychology , 18 (1), 73-99.

[84] MacDonald, C., & Sirianni, C. (1996). The service society and the changing experience of work. In C. MacDonald, & C. (. Sirianni, Working in the service society (pp. 1-26). Philadephia: Temple University Press.

[85] Malhotra, N. (1999). Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc.

[86] Markus, G., Thorsten, H., & Gianfranco, W. (2009). Customer Reactions To Emotional Labor: The Roles of Employee Acting Strategies and Customer Detection Accuracy. Academy of Management Journal , 52 (5), 958-974.

[87] Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior , 2, 99-113.

[88] Michael, M., Remus, I., & Erin, J. (2006). Relationship of personality traits and counterworkproductive work behaviours: the mediating effects of job satisfaction. Personnel Psychology , 59, 591-622.