Inequality, Ability to Pay and the Theories of Equal and ... · 1 Leonel Cesarino Pessôa, São...

Transcript of Inequality, Ability to Pay and the Theories of Equal and ... · 1 Leonel Cesarino Pessôa, São...

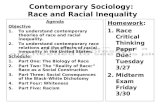

1

25th IVR World Congress

LAW SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Frankfurt am Main

15–20 August 2011

Paper Series No. 095 / 2012

Series B Human Rights, Democracy; Internet / intellectual property, Globalization

Leonel Cesarino Pessôa

Inequality, Ability to Pay and the Theories of Equal and Proportional

Sacrifices

URN: urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:3-249538 This paper series has been produced using texts submitted by authors until April 2012. No responsibility is assumed for the content of abstracts.

Conference Organizers: Professor Dr. Dr. h.c. Ulfrid Neumann, Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main Professor Dr. Klaus Günther, Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main; Speaker of the Cluster of Excellence “The Formation of Normative Orders” Professor Dr. Lorenz Schulz M.A., Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main

Edited by: Goethe University Frankfurt am Main Department of Law Grüneburgplatz 1 60629 Frankfurt am Main Tel.: [+49] (0)69 - 798 34341 Fax: [+49] (0)69 - 798 34523

1

Leonel Cesarino Pessôa, São Paulo / Brazil

Inequality, Ability to Pay and The Theories of Equal and Proportional

Sacrifices

Abstract: Brazil has one of the worst distributions of income in the world. The wealth of the richest

1% of the population is equal to that of the poorest 50%. Brazil has a greater concentration of wealth

than ninety-five percent of the countries on which data is available. In the legal field, tax justice is

based on the constitutional principle of the “ability to pay”, according to which taxes should be paid

based on the economic capacity of the taxpayer. This principle first appeared in the Brazilian legal

order in the 1946 Constitution, was excluded from the texts of 1967/69, and reappeared in § 1 of

article 145 of the 1988 Constitution.

The aim of this paper is to examine two possible grounds for the ability to pay principle (equal

sacrifices and proportional sacrifices) to show how, in Brazil, the interpretations that seek to assign a

positive content to the principle are limited to the horizons of a particular form of State associated

with the theory of equal sacrifice. This theory for its turn is consistent with a theory of justice, under

which no expense or charge levied by the government can alter the distribution of welfare produced by

the market. As the application of the ability to pay principle is done within the limits of that horizon,

as a consequence, this principle does not play an important role in the issue of reduction of inequality

in Brazil.

Keywords: ability to pay – tax justice - equal sacrifices – proportional sacrifices –– inequality –

distribution of income - theory of justice – Brazilian Federal Supreme Court

I. Introduction

Brazil is a country marked by social inequality. Although it has decreased recently, income

inequality in Brazil remains one of the largest in the world. In the book edited by Ricardo

Paes de Barros, Miguel Foguel and Gabriel Ulyssea on the recent reduction in income

inequality, are presented data showing how bad is the current situation: “the income earned by

the richest 1% of the population is equal to income earned by the poorest 50%” what makes

that “95% of the countries for which data is available, present lower concentrations than

Brazil”. 1 2

1 R. Barros, R. e M. Carvalho, Nota Técnica, In: Desigualdade de Renda no Brasil: Uma análise da queda

recente vol. 1, (ed. by R. Barros; M. Foguel; G. Ulyssea), 2006, 22. 2 In the book mentioned, it is shown that there is a long tradition of research on inequality in Brazil dating back

to the 1970s. They write: "Shortly after the publication of data from Census 1970, two studies showed the large

increase in inequality of income distribution in Brazil between 1960 and 1970: A. Fishlow, ‘Brazilian size

distribution of income’. In: American Economic Review, v. 62, n. 2, 1972 e R. HOFFMANN; J.C. DUARTE, ‘A

distribuição da renda no Brasil’, In: Revista de Administração de Empresas, v. 12, n. 2, p.46-66, 1972”.

2

While research on economic inequality date from some time, the discussion about how to

face it, in terms of tax policies, is not an issue in Brazil. Tax Justice is not a recurring theme

in the research taking place in the country. Very little has been written about it and this has

never been a topic in the public sphere debates. In this sphere, when the tax system is

discussed, it is usually discussed in terms of its efficiency. The proposal to impose a tax on

the financial transactions, for example, has this sense. This is also, in general, the goal of the

various tax reform proposals under discussion in Congress.

Recently, this situation has changed a bit. In the first presidential campaign, President

Lula has touched the issue of tax justice, when he said that the personal income tax, in Brazil,

should be more progressive, so that the rich would pay more tax than they currently do. A

Study of the IPEA3, from 2008, pointed in the same direction: from a comparison with other

countries, the study has shown that, in Brazil, the income tax is less progressive than in the

majority of these countries. In Lula’s government it was enacted a norm 4 that established two

new rates for the personal income tax, making it a little more progressive.

In the law field, the issue of tax justice is almost immediately linked to the constitutional

principle of the ability to pay. This principle entered the Brazilian legal order with the

Constitution of 1946, was excluded from the texts of 1967/69 and was once again included in

the Constitution of 1988. The first paragraph of article 145 of this Constitution states:

“Always when possible, taxes will have a personal character and will be graduated according

to the economic capacity of the taxpayer (...)”.5 Both with respect to law making and to its

application, discussions on tax justice depart from that concept.

Under the Legislative, this has occurred, for example, both when the Lula administration

increased the number of income tax rates, such as when the government Erundina 6 sent to the

parliament the proposal to increase taxation on property, in order to make public transport

free. Measures were justified by saying that the framework should be changed for taxation to

be in accordance with the ability to pay. Moreover, one of the strongest arguments against the

introduction of a single tax on financial transactions - proposal that is in the Brazilian

3 The acronym IPEA means: Institute of Applied Economic Research. It is the main institution for research in

this area in Brazil. 4 It was a Medida Provisória. It is a norm that is enacted by the executive power, but has to be approved by

parliament. 5 Victor Uckmar shows a series of recent constitutions that predict that taxes should be paid based on "the

economic possibilities" of taxpayers: Argentina (1946, art. 28), Bolivia (1967, art. 8 d), Bulgaria (1947, art. 94),

Ecuador (1966/67, art. 94), Greece (1951, art. Art. 3); Mexico (1917, art. 31), Switzerland (1981, art. 41), Chile

(1925, art. 10), Jordan (1952, art. 111), Italy (1947, art. 53), Syria (1950, art . 25), Spain (1977, art. 31.1),

Venezuela (1947, art. 282). Cf. V. Uckmar, Princípios comuns de direito constitucional tributário, 2ª edição,

1999. 6 She was the major of the city of São Paulo between 1989 – 1992.

3

Parliament - is that financial transaction are not a basis that reports adequately the different

manifestations of the ability to pay.

Also in the Judiciary discussion about justice in taxation is made based on the concept of

the ability to pay. Some jurists think that the practical application of this principle would

result in greater tax justice.

The aim of this paper is to analyze the interpretation that the legal literature and the

Brazilian Federal Supreme Court gave to the constitutional principle of the ability to pay. But

this analysis will be quite specific: its purpose is to put in evidence two possible grounds for

the principle (equal sacrifices and proportional sacrifices) and the social models or views that

correspond to each of them. This will be done in order to show how, in Brazil, the

interpretations that seek to assign a positive content to it are limited to the horizons of a

particular form of State associated with the theory of equal sacrifice.

The paper is divided in seven sections including this introduction. The second section

presents the interpretations of the principle in the legal literature, the third section examines

how it was interpreted by the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court, the fourth discusses two

possible grounds for the principle, the fifth explores the consequences of these different

grounds, the sixth section presents some final considerations.

II. The interpretations of the ability to pay principle in the legal literature

After the publication of the 1946 Constitution, the ability to pay principle was the object of

discussion and divergence amongst jurists, principally in relation to its application. 7 In the

first edition of his book, Teoria Geral do Direito Tributário, Becker shows how two currents

were in opposition in this point. 8

Even if some would defend that the ability to pay principle should produce effects

immediately, the position that it should be considered as a rule that merely states policies9

prevailed. This rule would serve, according to Sousa, to guide the lawmakers "in the choice of

facts, acts or transactions that should be subject to taxation, and in the grading of this

measure". 10

Over the years, this initial interpretation began to change and the other,

according to which the rule would take effect immediately, became the majority.

Historically, the interpretation of the effects to be produced by the principle has gone

through two distinct phases. This was true also in Italy, whose literature greatly influenced the

7 In Brazil, it is used a concept of “technical efficaciousness”. I am not sure which term should be used in

English 8 Alfredo Augusto Becker. Teoria Geral do Direito Tributário, 1963, 441.

9 A kind of norm that states a program.

10 Rubens Gomes de Sousa, Compêndio de Legislação Tributária, 1975, 95.

4

Brazilian tax law. According to a first interpretation, a precise content was assigned to the

principle: economic force. Only where economic force could be found could there be as well

ability to pay and, consequently taxation. One of the practical consequences of this was the

recognition of some situations, such as the zone of vital minimum which could not be taxed

because the people in this zone do not have ability to pay.

Later, it was interpreted that the ability to pay principle would be virtually linked to other

constitutional norms as the one which consecrates the duty of solidarity. In this sense, it

would have a fundamental role in the protection of the interest of the state: having in view, the

ideal of solidarity, the aspect to be singled out in the principle turns to be that no one should

shirk to contribute to public expenses in conformance with his ability to pay.

In this way, two distinct interests are protected by the ability to pay principle: in the first

place, the interest of the taxpayer, in the sense that no one should be taxed beyond his ability

to pay. Besides that, the interest of the state, for all manifestations of ability to pay cannot

escape taxation. 11

III. The Brazilian Federal Supreme Court

These two interests also appear in the interpretation that the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court,

the highest body of the Brazilian Judiciary, gave to the norm. In a research conducted on the

web site of the Federal Supreme Court, 12

it was verified that from the promulgation of the

1988 Constitution, in October 2008, until November 2008, the ability to pay principle was

applied 70 times at the decisions. After being excluded the judgments in which the use of the

principle was merely apparent, they were divided according to the interests that were being

protected - State or taxpayer.

In a few decisions, some dissenting opinions applied the ability to pay principle to

protect the interest of the taxpayer. Examples of these are the following: in one of them, it

was argued that financial transactions could not be chosen as the base for the CPMF 13

for not

expressing any manifestation of ability to pay. In another case, according to other dissenting

opinion, the introduction of a tax regime called in Brazil substituição tributária - in which the

tax of the entire production chain is paid at the beginning - would result in the violation of the

ability to pay principle.

11

This theme was developed in: L.C. Pessôa, Interesse fiscal, interesse do contribuinte e o princípio da

capacidade contributiva, In: Direito Tributário Atual, nº 18 (2004), 123-136. 12

The results of the research were presented at the Law and Society Annual Meeting, in Denver (CO) in may

2009 and were published later in Revista Direito GV, 5 (2009), 95-106. 13

A Brazilian tax on financial transactions.

5

In several cases, however, the ability to pay principle was applied to protect the interest

of the state. Examples of applications of the principle to protect the interest of the State are

the following: in the terms of article 145, first paragraph of the Constitution of 1988, literally,

the ability to pay principle applies in only one of the five types of tribute that being, the taxes

[impostos, in Brazil]: “Always when possible, the taxes (...)” (art. 145, § 1º). But there are

several decisions of the Federal Supreme Court which sought to apply the ability to pay

principle to another type of tribute: fees [taxas, in Brazil]. Even the fact that the constitution

literally determines that the principle is only applicable to taxes [impostos], the federal

Supreme Court understood that nothing impedes that it should be applied to fees [taxas] as

well.

There are also several court cases in which the ability to pay principle was applied in a

similar way. They are cases in which a differential treatment was given to some situations that

presented themselves as distinct. The taxpayer always rebelled against the distinction, arguing

principally violation of the principle of equality. The ability to pay principle was used in all

judgments, so as to ensure differential treatment to different situations. An example is the

following. It was argued that Article 9 of law 9.317/96, by impeding the corporations that

provide services to opt for a special tax regime for small business called simples, would be

establishing unequal treatment for taxpayers and then violating the principle of equality. The

Supreme Court decided that there is no violation of the principle of equality if the law, for

non-tax reasons, gives unequal treatment to micro and small businesses that have different

ability to pay. Therefore, the principle of ability to pay was being used to protect the interest

of the state and justify differential treatment.

The analysis of the decisions led to a principal conclusion: in Brazil, the ability to pay

principle was utilized by the Justices of the Federal Supreme Court, in some few dissenting

opinions, to protect the interests of the taxpayer and several times to protect the interests of

the state. Be it to assure differentiated taxes in some situations, as in the case of companies

who opted for the special tax regime, be it to guarantee that fees, [taxas, in Brazil] can be

collected at differentiated rates, be it, in general, to assure taxation in situations in which the

manifestation of the ability to pay exists, the ability to pay principle was always used in a way

that in situations in which the ability is revealed the tax should be collected.

This analysis could make people believe in the thesis that the application of the ability to

pay principle would signify greater distributive justice. After all, if it is the State's interest, not

the taxpayer, which predominates widely in the interpretation of the Court, wouldn’t this lead

to more distributive justice? However, a careful reading of the situations in which the

6

principle was used does not indicate that its application has resulted in large gains in terms of

distributive justice. Even if it was to defend the interest of the state, the principle has been

used only in a few specific situations of the business life and fundamentally to ensure

differentiated treatment to companies of different sizes. But could it be different? To answer

this question, this paper is intended to go back to its foundations and present tow possible

senses for the ability to pay principle.

IV. Equal and proportional sacrifices

For what reason should taxation be a function of the ability to pay of each one? Historically,

not always the principle of ability to pay was dominant. At least one criteria ran with it

throughout history: the benefit principle. According to the latter, there would be justice in

taxation if the amount to be paid in terms of tax correspond to the benefit of each one for the

existence of the state. But why the principle of the ability to pay would be better than the

benefit principle in terms of justice? What are the fundamentals of the ability to pay principle

that mark its superiority?

The principle of ability to pay seems to be founded on a simple idea: those who have

more money, have more capacity to contribute. Murphy and Nagel show, however, that this

apparent simplicity hides major theoretical difficulties, since one can say that the rich have

more ability to pay the poor in at least two different senses. 14

In this regard, they write:

“First we might think that people with more money can afford to give away more in the sense

that additional money is worth less to them in real terms, so they can pay more money than a

poorer person – sometimes much more – with no greater loss in welfare. Alternatively, we might

think that people with more money can afford to give away more because even if they sustain a

larger real sacrifice they will be left with more: they will still have, in some sense, enough – and

will still be better off than those who started out with less”. 15

These two senses in which one can say that people have different ability to pay will give rise

to two theories that try to substantiate the principle differently. On the one hand, according to

the theory of equal sacrifices, the principle of the ability to pay determines that the richer

14

According to Murphy and Nagel, there is also a third interpretation of the of ability to pay principle presented

by them, according to which the ability to pay would be related not to the person's current wealth, but to its

potential wealth, to the decisions that could have been taken by the person and to the income that the person

could have obtained by virtue of those decisions. This interpretation leads to the theory of taxation according to

endowment: people should pay based not on the income that they actually hold, but “according to their

endowment, which is defined as their ability to earn income and accumulate wealth”. (L. Murphy, T. Nagel, The

Myth of Ownership, 20) “The origin of the endowment principle lies”, according to Murphy and Nagel, “in the

earliest versions of the ability to pay approach”. (op. cit., 21) The professor of the New York University School

of Law, David Bradford, recently died, is one of its most eminent defenders. 15

L. Murphy, L.; T. Nagel, The Myth of Ownership, 2002 p. 24.

7

contribute more than the poorer ones, because the amount of taxes to be collected should be

different in nominal terms, so that the sacrifice is equal in real terms.

This theory assumes, therefore, that the marginal value of money is decreasing. This

means that the money that one person has more than the other does not have its nominal and

real value raised the same way. While the nominal value increases to a certain extent, the real

value of money increases less than that. In other words, under this theory, the rich should pay

more than the poor ones, because with this payment they will not suffer a greater loss in their

welfare, because to them, money does not have the real value it has for the poorest.

On the other hand, according to the theory of proportional sacrifices, both “A” and “B”

must collect taxes in a different amount, because, it will rest much more money for those that

have more, even if they make a real greater sacrifice. The consequence is that, besides having

enough, they will continue to be richer than those with less and it is this difference that

justifies, for this theory, that they should contribute with more.

The difference between the theories of equal and proportional sacrifices were presented

at a given level of abstraction. It is important now to point out this difference more concretely

discussing, from the standpoint of the state organization, the consequences of the application

of both theories.

V. The differences between the theories

According to the so-called liberal paradigm, the state should be minimal. It should perform

minimal functions, such as ensuring the existence of the police and the judiciary to resolve

any conflicts. All that it could not do is to intervene in relations between the parties, which

should be absolutely free to interact in the market.

As Habermas points out, on the basis of these ideas there is a very particular conception

of justice: as the law ensures formal equality to the actors who interact in the market, it is

enough to define the individual spheres of freedom of each one, i.e. ensure that the state does

not intervene in private spheres, for the relations between them to shape and develop in a fair

manner.

Thus, justice in the relations between citizens is assured, according to the liberal

paradigm, by the minimal state intervention in these relations. Whitin the grounds of taxation,

the theory of equal sacrifice conceives the state just like that. According to Murphy and

Nagel, the idea of equal sacrifices “does make sense if embedded in a wider theory of justice

8

that rejects all government expenditure or taxation to alter the distribution of welfare

produced by the market”. 16

For the state not to intervene in the relations between the parties, the tax system could not

play any role that would undermine the free market interaction. The more neutral it is, the

better it would perform its function of not intervening in the decisions of economic agents. It

is precisely not to intervene in the pre-tax relationships that exist between economic agents,

that the state should require from each of them, in terms of tax, the same sacrifice. Murphy

and Nagel accordingly conclude:

“Such a libertarian theory of justice, typically based on either some notion of desert for the

rewards of one’s labor, or of strict moral entitlement to pretax market outcomes, limits the role of

the state to the protection of those entitlements and other rights, along, perhaps, with the

provision of some uncontroversial public goods. If (and only if) that is the theory of distributive

justice we accept, the principle of equal sacrifice does make sense”. 17

Therefore, the theory of equal sacrifices makes sense within a particular theory of the state,

according to which its role is limited to ensure certain private rights and provide some public

uncontroversial goods.

However, the ability to pay principle can be also founded on the idea of proportional

sacrifices. This theory for its turn is compatible with the claim that the state perform broader

functions to correct the inequality of income distribution. Require, for example, from the

richer, to pay more taxes than the poorer not only to correct market failures, but to correct the

inequity of the current state of affairs is also to impose that both contribute according to their

ability to pay. But in this case, not ability to pay as equal sacrifices, but as proportional

sacrifices.

VI. Final Considerations

At the beginning of the work were presented data on the inequality in income distribution in

Brazil and it was seen that, in the law field, the discussion about tax justice departs from the

concept ability to pay that reentered in Brazilian legal system with the Constitution 1988.

It was presented the interpretation originally given to this constitutional disposition.

From the works of Rubens Gomes de Sousa, it was seen that this principle would be

interpreted as a merely programmatic norm. Over the years, the legal literature both in Italy

and Brazil, as the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court gave the ability to pay principle an

effective role in protecting both the interest of the taxpayer and the state.

16

L. Murphy; T. Nagel, The Myth of Ownership, 2002, 26. 17

L. Murphy, T. Nagel, The Myth of Ownership, 2002, 26.

9

It was seen then that the idea that everyone pays taxes according to their ability to pay is

compatible with two different grounds: equal and proportional sacrifices. Thus, the same

principle may give rise to different interpretations as distinct social models or visions are at its

foundation.

According to the theory of equal sacrifices, the richer should pay more taxes than the

poorer so that the ultimate sacrifice is the same. According to the theory of proportional

sacrifices, the richer should pay more because even if they pay, they will still be better off

than the poorer and this form of taxation reduces the injustice of the current situation of

inequality.

Internationally, the theory of equal sacrifices has always prevailed as the foundation for

the principle. Writing about vertical equity that is a term that, in the economic literature,

corresponds to the principle, Musgrave wrote: “vertical equity, since Stuart Mill, has been

viewed in terms of an equal-sacrifice prescription. Taxpayers are said to be treated equally if

their tax payments involve an equal sacrifice or lost of welfare”. 18

In Brazil, the ability to pay principle is always invoked when the issue is the reduction of

inequality and the role the tax system can play in this regard. Within the judiciary, the

principle appeared in 70 decisions of the Supreme Court.

The analysis of these decisions showed that, even though the principle was almost always

applied in the defense of the interest of the state, it has been used only in a few specific

situations of the business life and to ensure, fundamentally differentiated treatment to

companies of different sizes.

From a normative point of view, the issue in those decisions is the possibility to provide

more favorable conditions to a particular group of companies. Large and small companies

should pay taxes differently, since they have different ability to pay, in order for the sacrifices

to be the same. This use of the principle, therefore, is compatible with the Liberal State in

which the idea of taxation based on the theory of equal sacrifice is grounded.

In these decisions, in was never called into question the so-called pre-tax distribution

established by the market: the application of the principle not even remotely threatened to

problematize it.

18

Richard Musgrave; Peggy Musgrave, Public Finance in Theory and Practise, 1989, 228.