I-Tinerary: The Romantic Travel Journal after Chateaubriand

-

Upload

john-joseph -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of I-Tinerary: The Romantic Travel Journal after Chateaubriand

The South Central Modern Language Association

I-Tinerary: The Romantic Travel Journal after ChateaubriandAuthor(s): John JosephSource: South Central Review, Vol. 1, No. 1/2 (Spring - Summer, 1984), pp. 38-51Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press on behalf of The South Central Modern LanguageAssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3189240 .

Accessed: 05/09/2013 13:11

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

The Johns Hopkins University Press and The South Central Modern Language Association are collaboratingwith JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to South Central Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I-tinerary: The Romantic Travel Journal after Chateaubriand

JOHN JOSEPH Oklahoma State University

I

In May, 1832, Washington Irving returned to this country after a seventeen-year stay in Europe, and found his readjustment scarce- ly less difficult than Rip Van Winkle's after a comparable period away from the scene. Disconcerted, restless, he left in early July- just over a month after his return-on a journey west, with two men he had met while crossing the Atlantic, Charles Joseph Latrobe of England, and Latrobe's high-spirited Swiss valet, the nineteen-year-old Count de Pourtales. En route to the western frontier, which it was their intention to explore, they encountered Henry Leavitt Ellsworth, member of a presidential commission for the relocation of certain native American tribes from southern states to the Indian Territory. The trio accepted Ellsworth's invita- tion to join his party; Irving even agreed to act as secretary of the expedition. On 8 October they reached Fort Gibson, then set off with a military escort and a pair of colorful scouts on a four-week expedition through unexplored country in what is today Okla- homa.

On 20 October the retinue passed to the southeast of the present Oklahoma State University, near the bank of the Cimarron River, and, as Irving would later write in his book A Tour on the Prairies:

... one of the characteristic scenes of the Far West broke upon us. An immense extent of grassy undulating, or as it is termed, rolling country with here and there a clump of trees, dimly seen in the distance like a ship at sea; the landscape deriving sublimity from its vastness and simplicity. To the south west on the summit of a hill was a singular crest of broken rocks resembling a ruined fortress. It reminded me of the ruin of some Moorish castle crowning a height in the midst of a lonely Spanish landscape. To this hill we gave the name of Cliff Castle.1

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

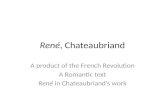

John Joseph 39

It was a long afternoon of driving unpaved roads and checking section boundaries before I located Cliff Castle on 20 October 1982, one hundred fifty years to the day after it received its name.2 (See Plate.) No evidence indicates that the red sandstone formation has undergone any marked change in structure or appearance in this century and a half, other than the overgrowth of planted cedars and the fact that the "rolling country" of Irving's northeasterly approach has been farmed since the 1890s. Not enough fallen rocks surround the "Castle" to suggest a prior magnificence. On each occasion I stood there, struggling to fathom how, in this singularly nondescript pile of stone, one could claim to see anything remotely resembling Irving's description. And through this struggle I ar- rived at an altered, better understanding of: one, Romanticism, particularly its component process of "ego projection" (see below); two, the travel journal as genre, in the Romantic period and in general; and three, metaphor and the act of poetic creation.

Irving's Castle. (Photograph by John J. Deveny, Jr.)

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

40 South Central Review

The travel literature of a given period shares the aesthetic and philosophical undercurrents shaping fictional writing, along with some of the same goals: to instruct and entertain by transporting readers, through the printed page, into contact with settings, circumstances, and characters unfamiliar to them, of a sort they have likely not encountered in actual experience and may or may not in the future. By reading about other places and persons, readers will come to an improved understanding of humanity and the world in general, of themselves, and the places most familiar to them.

The degree to which any piece of writing meets these goals and reflects current style trends depends totally on the talent and inclination of the writer. Normally the stylistic relation to "crea- tive" literature will be closer when the travel account's author is a master poet or storyteller. One purchases this account usually with somewhat different motives than in buying the anonymous Guide Michelin. The latter serves (or tries to serve) as a neutral, objective pointing finger that provides bare-bone background information, aimed almost exclusively at persons planning to visit, personally, the places treated. But very few readers of A Tour on the Prairies entertained serious thoughts of making the dangerous journey themselves; for some it might be a vague dream, for others a nightmare. I suspect that most bought it-and it was a very successful publication3-for the same reason they might purchase a book of fictional tales: to participate by exclusively vicarious means in adventures they would never actually play a part in. The metier of the creative writer is to present the raw materials the world furnishes in as interesting and significant a way as possible. If he or she is a master wordsmith, the narrative should be enjoyable reading. But I think an additional public faith is in operation-that because of a heightened perception of the world, the visionary ability to interpret scenes in terms of symbols and deep metaphysical meanings, the author is able to "interpret" the locus for readers, charging it with a meaningfulness they could not derive on their own.4 This is the same reason people go to the theater or watch television, rather than simply observe everyday happenings and meditate on them. For the price of x dollars, or of subjecting one's brain to violation by commercial announcements, one receives the promise that in an hour or two some highly charged slice of life will begin, climax and conclude, with a signifi- cance that does not require too much mental work to determine. Sales of the travel book will improve, too, if the publisher adds

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

John Joseph 41

photography done with the colors "filtered up," made more vib- rant, giving the scene an aspect no tourist could possibly see on his or her visit.

Are the tourists disappointed? Frequently, yes. "It doesn't look like the pictures," they lament. But do they blame the pictures, or the photographer, or the publisher? Never! It is, implicitly, the place itself which they blame, for not cooperating, not revealing its secret meanings to them; or more often, they blame themselves, as if their too too mortal eyes were incapable of seeing the mysteries without the intercession of the photographic artist, whose function thus assumes priestly dimensions. And likewise, mutatis mutandis, with the literary artist and the travel journal. She or he is the go- between with the ethereal.

In this light, seeing a ruined Moorish castle in an overgrown rock qualifies as a poetic act. It is vision by metaphor, and draws power from the special significance of a ruined castle for the Romantic imagination. We are unused to considering poetical acts outside of the direct context of writing, but that is how this one originated, more a mystical than a literary experience (not that the two are mutually exclusive). It therefore merits a bit of closer scrutiny. Of the three surviving written accounts of the tour besides Irving's, Latrobe's records nothing for the dates 18 to 25 October;s Ellsworth writes a passage very similar to Irving's:

... while conversing upon the beauties of the landscape, we descried at a distance, a perfect resemblance of an old Moorish castle in ruins-... -dame nature in her pranks some way, had so arranged the rocks and stones, as to give the repre- sentation, of every part, of an old citadel tumbling to ruins, and yet leaving all the traces of ancient magnificence-With leave of Mr Irving Doct Holt named it "Irvings [sic] castle."6

except that Irving records a different name; and finally Pourtal&s, writing in French, cites a rather more northeasterly metaphier and yet a third name: "'... we discovered a prairie butte formed of rock, like most of those we have seen. This one in particular so greatly resembled the ruins of those ancient towers along the Rhine that everyone agreed to name it Castle Rock."7 The actual journals which Irving kept during the tour, and to which he made reference when writing his book some one to two years later,8 are missing for the dates 15-25 September and 18-30 October, so we lack his immediate reactions for comparison.

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

42 South Central Review

There is no explicit proof, then, that it was Irving who came up with the metaphor, but it seems a natural assumption to make, given his tendency to compare Western scenes with European counterparts, and his proclivity to Spain. Incidentally, no possibili- ty exists that either Irving's or Ellsworth's written account was influenced by the other's, since Ellsworth's was sent as a letter to his wife and remained unpublished until 1937.9 Irving seems not to have begun his memoir until the latter part of 1833.10

Whence the castle? Irving did live in a Moorish castle in Spain the spring and summer of 1829, and made its name famous as the title of a book, The Alhambra, published just before his return to America." Now, the commonest negative judgment leveled against A Tour by twentieth-century critics has been that Irving saw everything in the west through an Easterner's eyes, constantly drawing European parallels-the savages are like Adonises, the landscapes like paintings by Claude Lorraine-making A Tour liber non gratus to an entire generation of Irving's staunchest admirers, including Stanley T. Williams and John Francis McDermott. But by 1966, McDermott was coming to recant his earlier stance;12 then in 1973 appeared a revisionist article by Wayne R. Kime, who takes the critics to task for not having read A Tour as "a formal or thematic whole."13 Fully three-fourths of all the European compari- sons, Kime points out, occur in the first one-third of the narrative. He claims that they were put there purposely by Irving to show how at the beginning of his tour he was, indeed, of "habits of perception impossibly ill-attuned to the realities of Western life,"14 and to illustrate how his perception gradually readjusted until he could appreciate the West on its own terms. Such a complex, sustained course of development held strictly to the subtextual level is a lot to ask of a writer like Irving. Yet given that he did not compose A Tour until months after the voyage, when his percep- tion would have quite completed its alleged alteration; and given the indisputable facts about the location of these allusions in the narrative, Kime's argument is strong, and we have no solid basis for denying that Irving had full artistic consciousness of what he was doing in this regard.

What mental processes were at play in the poetic act of castle building? Julian Jaynes might speculate that the castle image lay so fresh and vivid in the right hemisphere of Irving's brain that it took only the vaguest of resemblances in shape to call it forth to the left side, which gave it vocal vent.15 The other members of the tour party, moved (again, religiously) to be present at the formulation

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

John Joseph 43

of an impressive poetic act by one of the foremost authors the young nation had produced, were all too ready to participate in the novel vision. The rock, by being sufficiently unimpressive, unim- posing, neutral, allowed each man, upon the writer's suggestion, to build his own imaginary castle atop it. In fact, had the rock actually been more impressive, it might have impeded the imagi- nation's free constructive apparatus. Pourtales, for instance, might not have been able to visualize his Rhenish architecture where Ellsworth, prompted by Irving, saw the "perfect resemblance" of the Moorish.

For this reason too, along with that given by Kime, the harsh critical judgments accorded A Tour in the 1930s and '40s were undue. They failed to take into account the temper of the Romantic period, when every record of travel-geographical, moral, spiritu- al or socio-economic-was expected to be what I shall term an "I- tinerary": less an account of places or stations for their own sake than for their status as "evocative screens" for projection of the indefatigable Romantic ego.16

The published critiques of A Tour give no consideration to the meaning of the castle image for a second-generation Romantic like Irving. From medieval times, heroes had inhabited castles simply as a corollary to their noble status. Then toward the end of the eighteenth century came the first effects of the Industrial Revolu- tion and the ascent of the bourgeoisie. The days of castle building receded into the past, and the associative connotations of those imposing edifices began to change, from representing might and nobility and divine right, to dissipated power, an abandoned way of life: in short, death, gloom, evil. At least from the time of Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764), dark towers set high on stormy crags at midnight became an almost indispensable part of the Romantic repertoire, and Irving's sighting one in the middle of the Oklahoma prairie-a ruined one, at that-should not be looked on as a neutral event. We can read it as functioning on a multiplicity of levels. It is an intuition that this territory, virgin though it seemed, was yet the home of dying civilizations; a premonition too that the budding American civilization which would engulf even this land, was mortal as the rest.17 And perhaps a sense of personal decay: Irving was about to cross the half- century mark, and found himself less secure than he would like to be in his status as dean of American writers. After so long abroad, he was under suspicion of cultural treason.18 Cliff Castle, I submit, is Irving's Ozymandias. From Shelley, Byron, and other Romantic

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

44 South Central Review

precursors, he inherited an appreciation for the weird beauty of decay, and the pleasure, the voluptas dolendi connected with the realization of one's own demise.19

II

If this was the general Romantic inheritance, its applications to the unexplored regions of the New World were primarily the legacy of Chateaubriand. In fictional works such as Atala and Rend, which became "poetic and novelistic episodes" of his Genie du Christianisme, in Les Natchez, and in later works of a chronicle nature, including the Voyage en Amerique of 1827, he created a Louisiana and a Florida that outdid any European scene in exotic horror and delight.20 The following is Chactas' description of a pine forest in a valley not far from Cuscowilla, the Seminole capital, from Atala of 1801:

The night was delicious. The Genius of the airs was shaking his head of blue hair, perfumed with the scent of the pines, and we breathed the faint odor of amber exhaled by the crocodiles asleep beneath the tamarinds of the riverbanks ....One might have said that the very soul of solitude was sighing across this whole deserted land.21

The night's "delicious"ness is due in no small measure to the danger of imminent death from the hidden crocodiles, and from the exquisite sadness of that solitude. Later, in the Epilogue, Chateaubriand describes in his own voice the scene of Niagara Falls:

... At the Fall it is less a river than a sea whose torrents press each other at the gaping mouth of a chasm. The cataract divides infto two branches, and curves like a horseshoe. Be- tween the two falls there projects an island, hollow beneath, which hangs with all its trees over the chaos of the waves. The mass of the river, rushing toward the south, rounds into a vast cylinder, then unrolls into a blanket of snow, and shines in the sun with all colors. The water which falls to the east descends into a frightful shadow; like a column of water from the Great Flood. A thousand rainbows bend and cross over the abyss. Striking the shaking rock, the water splashes in whirlpools of foam, which rise overtop the forests like the smoke of a vast holocaust. Pines, wild walnut trees, high rocks cut in the

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

John Joseph 45

shape of phantoms, decorate the scene. Eagles, swept in by the air current, fall whirling to the bottom of the gulf; and wolverines hang by their flexible tails at the end of a fallen branch, to take from the abyss the broken cadavers of elk and bears.

While, with a pleasure mixed with terror, I was contemplat- ing this spectacle, the Indian woman and her husband left me.22

These are examples in fiction of the ego projection, the narcissistic vision so characteristic of Romantic writing. The author's sense of beauty and suffering is sent out and reflected back by his land- scape. The ruined castle existed not on that little crested butte in the plains of Oklahoma, but somewhere deep in the imageworks of Geoffrey Crayon, Esq., the pen name under which A Tour on the Prairies appeared.

The book's Introduction helps clarify the psychological processes at play. Irving regrets that newspapers anticipated the publication of this book even before he began it: "I have always had a repugnance, amounting almost to disability, to write in the face of expectation; and, in the present instance, I was expected to write about a region fruitful of wonders and adventures... yet about which I had nothing wonderful or adventurous to offer." He has struggled against this block, however, wishing to satisfy the pub- lic's appetite as promptly as possible: "As such, I offer it to the public, with great diffidence. It is a simple narrative of every day occurrences; such as happen to every one who travels the prairies. I have no wonders to decribe...."23 Technically these are true statements, but with the truths carefully crafted to mask the real state of affairs. Indeed:... I have no wonders, no adventures to describe, only everyday events. It was not a terribly eventful trip. What goes unsaid: that in describing these events I transform them into wonders, adventures. The additional elements come from myself. Irving could not publish "a simple narrative of every day occurrences." Practical and egotistical considerations did not allow it. The book would have aroused no interest or sales, and his literary reputation would have suffered. The Romantic was expect- ed to live romantically, and his dark visions had motivation nearly as strong as the Old Testament prophets' and medieval mystics'.

Beyond this, it may be that with the Oklahoma prairies, Irving found an extraordinarily receptive medium for his sensibilities. For the Romantic muse, characterized by narcissistic extrapolation of the ego, the dark, lonely scenes of Spain are stimulating; but

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

46 South Central Review

perhaps the ideal canvas is the blank one, where reality interferes as little as possible with the projection of the internal vision. Again, the construction of Cliff Castle was facilitated, not impeded, by the plain ordinariness of that rock; and its subsequent name shift to "Irving's Castle" is true poetic justice, since no castle existed before Irving's mind built it there. Chateaubriand achieved his blank screen in a different way, because the truth is that his travels in America never took him farther west than Pittsburgh.24 Seeing the places he wrote about might, again, have blocked his creative imaginary process.

Irving may also have found that the travel journal provided a medium of surprising "purity" for the exercise of vision and style, there being no plot as such to which he should feel compelled to bend them, and character development amounting to little more than progressive sketches.

Perhaps the best known of post-Romantic castles, thanks to Edmund Wilson, belongs to the hero of Villiers de l'Isle-Adam's long dramatic prose poem, "Axel." You may recall that Axel stumbles upon a young noblewoman, escaped from a convent, at the moment she discovers the enormous treasure hidden in the castle by his father. They struggle, then almost immediately fall in love, and indulge in rapturous dreams of the travels they will make with their new-found riches to the world's most exotic places. But the dreams, Axel declares, are too beautiful. In dreaming them the couple has attained a moment of perfection, and the actuality, if realized, could only prove a disappointment. And so they commit suicide. Wilson writes:

... whereas it was characteristic of the Romantics to seek experience for its own sake-love, travel, politics-to try the possibilities of life; the Symbolists, though they also hate formulas, though they also discard conventions, carry on their experimentation in the field of literature alone; and though they, too, are essentially explorers, explore only the pos- sibilities of imagination and thought.25

The readers of Irving's Oklahoma, Chateaubriand's Florida, and

Byron's Greece, who sustained themselves with others' adven- tures and never realized them on their own: this was the seedbed from which blossomed the Symbolists. Inevitable, perhaps, that the generation succeeding the last Romantics, no longer being perfectly in tune with the "I"s whose I-tineraries they read, failed to assimilate the priestly summons; thus on the actual viewing did

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

John Joseph 47

not respond as programmed, and could not help but be disap- pointed. West of the Mississippi, Washington Irving saw much as his slightly older (fifteen years) contemporary Chateaubriand had led him to see. Likewise, the other members of the prairie tour party saw as Irving commanded them (with a slight and very telling variation in the case of Pourtales, for whom something may have gotten lost in the network of translations).

III

The Romantic I-tinerary is not restricted to fictional works and travel journals for places inaccessible to most readers. Stendhal, who shared with Irving a bicentenary in 1983, published books and guides on Italy and Southern France, very clearly intended for prospective travelers. It is true, as Allan Seager has written, that "Scenes of nature he describes dryly, accurately, unromantically, partly in reaction against the florid romantics of his time like Chateaubriand... "26--a development predictable from the ideas I have outlined. Yet in his description of the view of the dome of St. Peter's from his room at sunset, it is personal reaction all the way:

Nothing on earth can be compared to this. The soul is moved and elevated, a calm felicity fills it to overflowing. But it seems to me that in order to be equal to these sensations one must have loved and known Rome for a long time. A young man who has never encountered unhappiness would not under- stand them.27

In good Chateaubriandian manner, Stendhal wrote his "pro- menades dans Rome" in his Paris apartment, across the Rue Richelieu from the Bibliotheque Nationale, from which his cousin would bring him other writers' memoirs of Rome for... inspira- tion. Stendhal at least had visited the Italian capital, though once less than he claimed to have in the Introduction to Promenades.28 Again, it may be supposed that distancing himself from his locus aided Stendhal in attaining the book's superbly Romantic vision. Promenading through the actual streets of Rome, he would con- stantly be slapped to reality by the cries of fishmongers and strident children, by the overpowering stink of feces decaying everywhere in the oppressive August sun. Instead, he pro- menaded through the city as it existed within his own mind, an ideal vision in the most literal sense of the word. The title gives a clue to

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

48 South Central Review

this: ever since Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Reveries du promeneur sol- itaire which Stendhal's promenades recall, the lonely walk has been a ritual for engaging the soul in Romantic flights. The continuing popularity of Promenades dans Rome as a travel guide even in our own century attests to a popular hunger for idealized El Dorados and storybook rapture that burgeoning technology, rather than attenuating, has possibly augmented.

The tradition of "ego projection" lives, in all types of fiction where setting is a prime ingredient of mood and plot; and even, to a reduced degree, in modern, supposedly objective travel guides. The following excerpts from the Oklahoma section of Fodor's South- west 1982 promise the tourist scenes of

battle Cold air pouring down from the Rockies and the warm, humid air coming up from the Gulf generally collide somewhere over Oklahoma, launching the vast weather systems that sweep eastward across the United States.

superhuman achievement Perhaps the most remarkable development in recent years has been the bringing of the sea to Oklahoma. Through massive dredgings and a series of seventeen locks, the Arkansas River is now navigable by seagoing vessels from the Mississippi River as far as the port of Catoosa, near Tulsa.... [T]he project was the largest ever undertaken by the U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers....

drama From Bartlesville, travel south on State 123 to Woolaroc, once the ranch of the late oilman Frank Phillips, now converted into a dramatic museum. Collections in the museum illustrate the

story of the American West... Here are Jo Mora's heroic bronze statues...; the entries in Ernest Marland's Pioneer Woman competition; mounted hunting trophies from around the world; canceled milliondollar [sic] checks and other mementos of Phillips' oil deals.

history Passing through the small mountain community of Big Cedar,

you see a United States flag flying high over a commemorative

plaque where the late President John F. Kennedy opened and dedicated this highway.

wonders of the world From Spiro, drive south to Poteau, site of Cavanal, the world's largest hill. Rising 1,999 feet, Cavanal doesn't qualify geo-

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

John Joseph 49

graphically as a mountain, which must rise at least 2,000 feet above the surrounding terrain. Here turn north on State 50 to Alabaster Caverns State Park, where you may tour the world's largest known alabaster cave....

Inside the caverns are such unusual formations as the Cathedral Chamber and Dome, the Catacombs, the Heart Dome, the White Way... Gun-Barrel Tunnel and...the Devil's Bathtub.... For those who enjoy spookier aspects, guides point out bats hanging overhead. The ranks of grain elevators lining the railroad silently testify to the tremendous volume of wheat shipped from Enid each autumn. Bank upon bank of these gargantuan, silo-like cylin- ders-each containing millions of bushels of grain-reach skyward.29

The average modern traveler is far less subject to the paroxysms of rapture without which the early nineteenth-century journey was a crushing disappointment. This may stem in part from our much increased opportunities for travel, which has meant both that the average voyager is of a lower social rank than before, and perhaps less "spiritually" developed, in the Romantic sense-still desiring the ecstasy, but unwilling to do the necessary preparatory read- ing-and also that even for the "sensitive" traveler, the greater commonness of the event tends to reduce its promise. National Geographic magazines and television programs make the world so devastatingly accessible that each month leaves less room for the kind of imagination and ego projection once practiced by Chateaubriand, Washington Irving, and Stendhal, and shared by their grateful readers.30 As the ecstasy diminishes, the priestly role adjusts down accordingly; and Mr. Fodor and the French tire company are careful to mete out just a little romance, enough to invite, enough to inspire-never enough to provide the volup- tuousness of a shattered heart.

NOTES

An earlier version of this paper was presented at a conference entitled "The World as Mirror: Narcissism in the Fine Arts and Humanities," at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, on 4 June 1983. I wish to express my gratitude to Norman Grabo of the University of Tulsa for his most gracious assistance.

1Washington Irving, The Crayon Miscellany, ed. Dahlia Kirby Terrell (Boston: Twayne, 1979), p. 61.

2According to Ellsworth's narrative of the tour, sent originally as a letter to his wife, "With leave of Mr Irving Doct Holt named it 'Irvings castle' " (Henry Levitt

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

50 South Central Review

Ellsworth, Washington Irving on the Prairie, ed. Stanley T. Williams and Barbara D. Simison [New York: American Book Co., 1937], p. 62). Today, those local residents who are aware of the formation and know that it has a name call it Irving's Castle- a fact which will prove significant in my subsequent discussion.

3See Martha Dula, "Audience Response to A Tour on the Prairies in 1835," Western American Literature, 8, Nos. 1 & 2 (1973), 67-74.

4By no means do I wish to sound as if Washington Irving is some kind of visionary or symbolist-that is absurd. For many readers his first reputation was as a humorist, or a chronicler; but I think he was and is most widely and best appreciated as a teller of tales-and that is enough.

5See Charles Joseph Latrobe, The Rambler in Oklahoma, ed. Muriel H. Spark and George H. Shirk (Oklahoma City and Chattanooga: Harlow Publ. Corp., 1955), p. 51n.

6Ellsworth, p. 62. 7Count Albert-Alexandre de Pourtales, On the Western Tour with Washington

Irving, ed. George F. Spaulding, tr. Seymour Feiler (Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1968), p. 62.

8Irving, Crayon Miscellany, pp. xxiii, xxvii.

9See Irving, Crayon Miscellany, pp. xxiv-xxv.

10Irving, Crayon Miscellany, p. xxiii.

11Cf. Ellsworth, p. 62n.

12See Washington Irving, The Western Journals of Washington Irving, ed. John Francis McDermott, 2nd ed. (Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1966), p. ix.

13Wayne R. Kime, "The Completeness of Washington Irving's A Tour on the Prairies," Western American Literature, 8, Nos. 1 & 2 (1973), p. 56.

14Kime, p. 56.

15Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1976).

16The subsequent development of Romanticism may also be resumed under this view: growing concern with the evocative screen itself rather than with the

projecting ego gave rise to Symbolism. Impressionism might be seen as a reversal of the emitter--+ object schema, and thus in this sense as a revolutionary opposite of Romanticism, except that in most cases it is not simply a case of the object promoting its impression onto the ego, but rather an extension of the matrix here

suggested for Romanticism, thus: artist's ego-- evocative screen-* back to artist's

perceptive faculties. This might also link Naturalism and the Decadence as most

"pure" heirs of the Romantic mode, distinguished primarily by the loss of the ego's heroic aspects and by changes in the artistic qualities of its projection.

17William Bedford Clark, who reads A Tour as a mock-heroic reversal of common-

places regarding the inevitable victory of the civilized over the wild, concludes that

"... even before he set foot on the southern plains, Irving was aware that he would be visiting a region already doomed to fall before the march of progress. His

willingness to allow the West to win so decisively in that work would seem to

represent a conscious subordination of reality to romantic desire" ("How the West Won: Irving's Comic Inversion of the Westering Myth in A Tour on the Prairies," American Literature, 50 [1978], 346-347).

18See John Joseph, "The Romantic Lie," in Washington Irving Papers, Hofstra Univ. Cultural & Intercultural Studies (New York: AMS Press, forthcoming).

19The classic statement is, of course, that of Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony, tr.

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

John Joseph 51

Angus Davidson, 2nd ed. (New York: Meridian Books, 1956). 20As it happens, Chateaubriand also preceded Irving in visiting the Alhambra.

See Chateaubriand, Les Aventures du dernier Abencdrage, ed. F. Letessier (Paris: Garnier, 1962), pp. 283-293; Fernand Letessier, "Chateaubriand etait-il accompagne ou non quand il visita l'Alhambra en avril 1807?" in Chateaubriand, pp. 389-398; and John A. Frey, "Irving, Chateaubriand and the Historical Romance of Granada," in Washington Irving Studies, Hofstra Univ. Cultural & Intercultural Studies (New York: AMS Press, forthcoming).

21My translation. The original: "La nuit etait delicieuse. Le Genie des airs secouait sa chevelure bleue, embaum&e de la senteur des pins, et l'on respirait la faible odeur d'ambre, qu'exhalaient les crocodiles couches sous les tamarins des fleuves.... [O]n eiit dit que l'ame de la solitude soupirait dans toute l'etendue du desert." Chateaubriand, Atala, ed. F. Letessier (Paris: Garnier, 1962), p. 58.

22, ... au moment de la chute, c'est moins un fleuve qu'une mer, dont les torrents se pressent a la bouche beante d'un gouffre. La cataracte se divise en deux branches, et se courbe en fer a cheval. Entre les deux chutes s'avance une ile creusde en dessous, qui pend avec tous ses arbres sur le chaos des ondes. La masse du fleuve qui se precipite au midi, s'arrondit en un vaste cylindre,puis se deroule en nappe de neige, et brille au soleil de toutes les couleurs. Celle qui tombe au levant descend dans une ombre effrayante; on dirait une colonne d'eue du deluge. Mille arcs-en-ciel se courbent et se croisent sur I'abime. Frappant le roc ebranle, l'eau rejaillit en tourbillons d' cume, qui s'el&vent au-dessus des forets, comme les fumees d'un vaste embrasement. Des pins, des noyers sauvages, des rochers taills en forme de fant6mes, d&corent la scene. Des aigles entraines par le courant d'air, descendent en tournoyant au fond du gouffre; et des carcajous se suspendent par leurs queues flexibles au bout d'une branche abaiss&e, pour saisir dans l'abime les cadavres brises des elans et des ours.

"Tandis qu'avec un plaisir mAl de terreur je contemplais ce spectacle, 1'Indienne et son epoux me quitterent." Chateaubriand, pp. 157-158.

23Irving, Crayon Miscellany, pp. 8-9. 24See Chateaubriand, pp. xvi-xxi; and Joseph Bedier, "Chateaubriand en Ameri-

que," Revue d'Histoire littcraire de la France, 1899, pp. 501-532, and 1900, pp. 59-121, which enumerates the sources of Chateaubriand's "borrowed" wilderness.

25Edmund Wilson, Axel's Castle (New York: Scribner's, 1931), p. 265. 26Stendhal, Memoirs of a Tourist, ed. & tr. Allan Seagar (Northwestern Univ.

Press,1962), p. x. 27Stendhal, A Roman Journal, ed. & tr. Haakon Chevialier (New York: Orion, 1957),

pp. 10-11. The original: "Rien sur la terre ne peut etre compare a cela. L'ame est attendrie et dlev&e, une filicite tranquille la penetre tout entiere. Mais il me semble que, pour etre a la hauteur de ces sensations, il faut aimer et connaltre Rome depuis longtemps. Un jeune homme qui n'a jamais recontre le malheur ne les compren- drait pas" Stendhal, Promenades dans Rome (Sceaux: Jean-Jacques Pauvert, 1959), p. 17.

28See Joseph, "The Romantic Lie." 29From Ross Goodner and Bill Burchardt, "Oklahoma," in Fodor's Southwest 1982

(New York: Fodor's Modern Guides, 1982), pp. 175, 179, 184, 186, 186, 199, and 192, respectively.

3The prose of National Geographic is never extravagant, nor do the photographs appear tampered with beyond the cameraman's normal light, color, and focus adjustments. Yet these are nothing like the snapshots which the readers themselves would take if they ever visited the place.

This content downloaded from 143.88.66.66 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 13:11:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

![Document fourni par les éditions Acamedia Etudes historiques [Document électronique] / [Chateaubriand] Avant-propos Mars 1831. " Souvenez ...](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5e62aaa1396cfa45b2361519/document-fourni-par-les-ditions-acamedia-etudes-historiques-document-lectronique.jpg)