“I don’t want to become a China Buff”: Temporal dimensions of the discoursal construction of...

-

Upload

amy-burgess -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of “I don’t want to become a China Buff”: Temporal dimensions of the discoursal construction of...

Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Linguistics and Education

j ourna l ho me pag e: www.elsev ier .com/ locate / l inged

“I don’t want to become a China Buff”: Temporal dimensions of thediscoursal construction of writer identity

Amy BurgessGraduate School of Education, Exeter University, United Kingdom

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Available online 8 June 2012

Keywords:IdentityWriter identityLiteracyTimescalesDiscourseWriting

a b s t r a c t

This paper offers detailed analysis of ethnographic data concerning an adult literacy stu-dent producing and discussing a text about China, using the framework for investigatingthe discoursal construction of writer identity developed by Burgess and Ivanic (2010). Itsheds light on how writer identity changes and develops over time by showing how differ-ent aspects of identity and different timescales come into play during one act of writing.The analysis reveals the possibilities for and constraints upon change and developmentcontained within that act and enriches understandings of how a single writing activity cancontribute to writing development.

© 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

This paper sheds light on how writer identity changes and develops over time by showing how different aspects of identityand different timescales come into play during one act of writing. The analysis reveals the possibilities for and constraintsupon change and development contained within that act. Using the framework for investigating the discoursal constructionof writer identity developed by Burgess and Ivanic (2010), it offers detailed analysis of ethnographic data relating to anadult literacy student producing and talking about a piece of writing on China. A number of recent studies have suggestedthat identity needs to be understood not as a static entity, but rather as a continuous process of identification, somethingwhich unfolds over time (du Gay, Evans, & Redman, 2000; Ivanic, 2006; Lemke, 2000, 2002; Sfard & Prusak, 2005). I arguethat such an understanding of writer identity can be developed by investigating the interrelationship among its differentaspects and the timescales on which they exist. However, a temporal dimension has been largely absent from research onthe discoursal construction of writer identity (but see Burgess & Ivanic, 2010). At a more general level, Mercer (2008:38)argues that ‘there is a gap in contemporary educational theory where there should be a conceptual framework for explaining“becoming educated” as a temporal, discursive, dialogic process’. Bloome, Beierle, and Grigorenko (2009) point out that thisgap has recently been acknowledged by researchers who advocate a focus on learning across timescales longer than thelesson (see for example, Leander, 2001; Leander & Lovvorn, 2006; Lemke, 2000; Mercer, 2008; Wortham, 2003, 2008). Muchof this work traces the trajectories of people, texts and discourses across space and time. It also focuses on talk ratherthan writing. The present article complements this work by investigating writing, and specifically the interplay of differenttimescales within a single act or moment of writing.

Educational research and practice has traditionally been rooted in modernist understandings of time which can be tracedback to the Newtonian vision of the universe as a clockwork mechanism. According to this view, time – and by extension,causality – is conceived as a unidirectional, linear process (time’s arrow). Newtonian time is an entity capable of being

E-mail address: [email protected]

0898-5898/$ – see front matter © 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2012.04.001

224 A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234

manipulated, quantified and infinitely divided into space-like segments (Adam, 2004; Slattery, 1995). One example of themany types of educational research based on modernist assumptions about the nature of time would be studies whichuse pre- and post-test methodologies to measure learning by comparing snapshots of learners’ capabilities at differentpoints in time. Such studies treat time as a kind of universal measuring stick against which learning events can be placed.Modernist assumptions also give rise to views of learning as a linear, stepwise process in which ‘learning outcomes’ arethe predictable result of pedagogical ‘input’. However, scholars have begun to argue that such assumptions are out of stepwith understandings of the nature of time developed by natural scientists since the early 20th century (Adam, 1990, 1995;Slattery, 1996). Slattery argues for a postmodern understanding of time in education in which ‘the present experience isinfused with an evolving interpretation of the past and a socially constructed emergent future’ (1996:629). Similarly, Adamcalls for research which acknowledges that learning is a process with a history and a future and cannot therefore be containedwithin observable moments (1995:72). In other work (Burgess, 2010a) I have taken a first step in this direction by seekingto view learning as a dynamic process rather than a series of isolated events or static ‘before’ and ‘after’ states. This paperbuilds on that work by developing the concept of a learning ‘event’. My approach is to view ‘points in time’ or ‘events’ asbeing temporally extended by their links with other timescales (Burgess, 2010a; Adam, 1995). In this way I offer one possibleanswer to the question posed by Lemke: ‘[H]ow could events on the timescale of a conversation or an experiment or readinga story . . .. contribute to identity development?’ (Lemke, 2000:283 emphasis in original.)

Wortham (2008) shows how trajectories of identification can turn in new directions and argues for the need to examineempirically the different ways in which trajectories are formed out of events. I focus in detail on a single event – a particularact of writing – and trace a writer’s trajectory of identification forwards and backwards in time from it. The event consistedof a classroom activity in which adult students researched and wrote about a country they would like to visit. The eventrepresents a point at which the writer’s trajectory had the potential to turn in a new direction and my analysis reveals thepossibilities for and constraints on change embedded within it. I am thus able to uncover possible reasons why the writingactivity was – in the student’s eyes at least – less than successful. My analysis supports the claim that writing is a highlycomplex social activity (Ivanic, 1998) and enables me to argue that in order to take full account of this complexity, pedagogyshould include explicit attention to issues of writer identity. Teachers’ understandings of how a single writing activity cancontribute to writing development can be enriched by an awareness of how different timescales and different aspects ofwriter identity come into play within the act of writing. This kind of understanding is necessary if writing activities are tobe fully exploited as opportunities for learning.

The structure of the article is as follows. I begin by describing the research context, data and method. This section alsopresents two data extracts which form the focus of the analysis. I then explain the significance of timescales and the conceptof discourse for understanding writer identity, before providing an overview of Burgess and Ivanic’s (2010) framework forinvestigating the construction of writer identity. Finally, I discuss the insights gained by using the framework to interpretdata about one adult student’s writing. The analysis reveals both the possibilities for identity development offered by thewriting activity and the constraints which the student encountered when choosing among them.

2. Research context, data and method

The data discussed in this paper were gathered as part of an ethnographic study of the discoursal construction of identitywhich I carried out in three adult literacy classes in England. The writing activity described here took place in a class providedby a Further Education college in a city in the west of England. The course was designed for adults who wished to work onliteracy before finding or changing jobs or embarking on vocational or Access to Higher Education courses. It ran for 3 h oncea week for one academic year. Prior to starting the course, the students had been formally assessed and were all consideredto be working at around Entry Level Three or Level One of the UK National Qualifications Framework in literacy. In order tohelp the college meet externally set achievement targets, all students were expected to take the National Literacy Test atthe end of the year. When the fieldwork took place between six and eight students were enrolled, five of whom attendedregularly.

I carried out fieldwork in the class described here over a period of four months, visiting regularly as a participant-observer.I also carried out recorded, semi-structured interviews with the tutor and five of the students. My data from the class consistof fieldnotes on observed sessions; interview transcripts; plans, drafts and final versions of 11 pieces of writing by students;stimulus and support materials used for writing; other teaching and assessment materials; schemes of work and sessionplans prepared by the tutor; photographs.

The discussion focuses in detail on the production of a written text by one student, here referred to as Marion, who wasa retired woman in her sixties. The quotation in the title of the article is from an interview I carried out with her after shehad completed her writing. The students had been asked to gather information and write about a country they would liketo visit. The tutor, Sheila, had provided them with a selection of travel brochures and they had used the internet to findmore information. Having retrieved large amounts of material from websites and holiday brochures, the students then usedmind maps to aid the processes of selecting information and planning the structure of the writing. They then producedhandwritten drafts before word-processing a final version.

Adult literacy educators have long recognised the value of encouraging students to write about their own interests andexperiences. Such writing has the capacity to shift the emphasis away from what students apparently lack, onto what theyalready know and can do (O’Rourke & Mace, 1992) and is able to foster personal development (Gillespie, 2007). Gaber-Katz

A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234 225

CHINA

China (People’s Republic China) is a vast and diver se cou ntr y situ ated in Eastern Asia bordered

by Russia and Mongolia and Canada. China is one of the most populace cities in the wor ld with

Beijing (famous for it’s collection of panda’s) as its capital an d Shanghai it’s largest city.

Travellers fr om all over the world vi sit China to soak up its historical sights that a re steeped in

ancient history. Many are surprised to find how modern China has become with explosive

growth an many concrete modern cities. Of c ourse Ch ina still mai ntains it s ric h and te xtur ed

history with its cult ural and artistic tradition.

Mandarin Chinese is the official language, with Cantonese widely spoken in the South, but many

Chinese people have now mastered the English language.

One could spend many months in China and not see all of it’s treasures. Many famous one’s are

the Great Wall of China (meandering over 3,000 miles), the Terra Cotta Army Warriors

discovered in 1979 and Mount Everest in Nepal on its borders and Tibet with it’s hidden history.

Its cultural heritage is legendary with calligraphy, painting, Buddhism, poetry, music, lacquer

work, and porcelain to name but a few. Acupuncture is one of China’s an cient tradition’s that

has been embraced by the West,

The eyes of the world will be on China in 2008 as Beijing hosts the World Olympics.

For westerners one symbol of Chinese food is the use of chopsticks. Chinese meals are usually

eaten in a group as diners share a variety of small dishes with delicate flavours and fresh

ingredients. Westerners have adapted many Chinese dishes to suit their palette, with thousands

of Chinese restaurants and takeaways.

For me with all it ’s con trasts and bea uty China would certainly be on the top off my list of

countries I would like to visit.

Fig. 1. Marion’s writing about China.

argues that personal writing can enable literacy students ‘to understand themselves better as individuals and as part ofsociety, and to envision and participate in the transformation of society – a society which presently benefits literacy learnersthe least’ (Gaber-Katz, 1996: 49). Sheila clearly wished to draw on this tradition in her teaching. She stated that she thought‘people’s experience’ was the best resource she could use as a writing teacher and that the main aim of her teaching wasto enable the students to develop confidence in themselves as writers. In what follows I use the notions of identity andtimescales to analyse the writing event described above and to assess the extent to which it met such aims.

The starting point for the research was the categories for investigating the discoursal construction of writer identitydeveloped by Ivanic (1998). Analysis followed the practical steps described by Barton and Hamilton (1998). I cycled backand forth between refining the categories and using them to inform data analysis. (I explain these categories in Section 4below, in relation to my data.) In parallel with this Ivanic and I developed the framework presented in Burgess and Ivanic(2010) (see below) through extended discussion of the significance of time and timescales for the discoursal constructionof identity, and of the implications of this theoretical link for data generated by our own research on writing in a varietyof contexts (see for example Burgess, 2008, 2010a, 2010b; Ivanic, 2005, 2006; Ivanic et al., 2009). I subsequently used theupdated framework to re-analyse data about a specific act of writing by one student and it is the findings of that analysiswhich I discuss here. The data selected for re-analysis consist of the following:

• Marion’s text about China.• Pages from websites which Marion used as source material.• The transcript of my interview with Marion.• The transcript of my interview with Sheila.• Fieldnotes from the sessions in which the class worked on the writing.

Fig. 1 shows Marion’s finished writing.In her interview Marion talked about how she had a long-standing interest in China, which had been sparked by a

particularly inspiring history teacher at school:

I’ve always, just always just had a fascination with China and Egypt as well . . .. . .. . ..I think it’s partly to do with whatI can remember at school. We had a brilliant history teacher and he inspired that enthusiasm in me you know, all thedifferent things. He was brilliant, it’s all stayed.

226 A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234

She went on to say that she was decorating a room in her home in a Chinese style, and I asked her how she would findinformation to help her do so, before inviting her to reflect on her writing about China.

I: You said you were going to decorate a room in your house in a Chinese style, how do you know how to do that?M: You read books, go on the internet, read books, I mean I’ve got four books in my bag now from the library just –and you think, Oh I like that, I like that colour, or I like that vase, yeah. I don’t, I don’t want to become knowledgeable,you know, I don’t want to become a China buff sort of thing, but I know what I like and I know what I want. . .. . ..I: Now you’ve finished that [the writing about China] how do you feel about it?M: I think it’s too, if I was taking maybe a history lesson I would think it was all right, but I think it’s, I think it’s toostilted and too factual, I don’t think I’ve made it interesting enough.I: When you were writing it what did you have in mind? What were you trying to make it like?M: I wanted someone to read that and think, Yes I want to visit China as well, I want to go there, gosh that’s, thatsounds really interesting, I’d love to go there. And I don’t think I’ve grasped or captured what I want to say.

I began data analysis by re-reading the interview transcript and Marion’s writing several times, following the proceduresuggested by Hammersley and Atkinson (1983), noting any odd or surprising things and how the data related to the theoret-ical framework. I selected the section of Marion’s interview in which she talked about her love of China and her evaluationof her writing for more detailed analysis because it did indeed seem ‘odd’ in some respects. Marion said she wanted to writesomething that would make the reader wish to visit China, but felt that her writing was ‘too stilted and too factual’. Elsewherein the interview she said she would award herself only 5 out of 10 for it. The reasons for her dissatisfaction, however, werenot immediately apparent. She told me that when Sheila introduced the task she had no difficulty in deciding which countryto choose because

I want to go there . . .. . .. . .. . .. . . I would LOVE to visit China, I just find it a fascinating country.

It was obvious that she was strongly motivated and interested in the topic and she explained in another part of herinterview that she enjoyed writing and thought she had a natural talent for it. So why did her finished piece fall so far belowher intentions? I suggest that in order to understand these issues it is necessary to explore the different timescales relevantto Marion’s identity as a writer.

In the above interview extracts Marion mentions a number of different timescales that were relevant to her writing, suchas her memories of school, her current home decoration project, her anticipation of her reader’s response to her writing,and her desire to visit China. This was a common feature of all the interviews and led me to consider the significance of thedifferent timescales people mentioned when I moved on to more detailed analysis of selected sections of the data. It wassomething I returned to when re-analysing the data about Marion.

In the next section I explain why I consider discourse and timescales to be important in understanding writer identity,before introducing Burgess and Ivanic’s (2010) framework. I then discuss the insights it generated when used to informdetailed analysis of data about Marion.

3. Writer identity, discourses and timescales

The overarching theoretical framework that guided the study connects theories of writing, identity and learning throughthe concept of discourse. It draws on Gee’s (1996) and Ivanic’s (1998) definitions of discourses as socially accepted represen-tations of reality which entail thinking and acting in particular ways, or as ‘identity kits’ (Gee, 1996:142) that enable peopleto take on particular socially recognisable roles. One of the most salient ways in which people participate in discoursesand take on the identities they proffer is through the use of language and other semiotic resources (De Fina, Schiffrin, &Bamberg, 2006). The discoursal construction of identity is therefore a key factor in language learning and writing (Gee, 1996,2001; Ivanic, 1998, 2005, 2006; Satchwell and Ivanic, 2010) and understanding how people learn and develop as writersnecessitates understanding the kinds of identities they are able and/or obliged to construct through their writing.

The view of writer identity presented here draws on insights developed within several strands of the research literature.Goffman’s (1969, 1981) social interactionist theory first gave rise to the idea that identities are relational; they are builtthrough interaction rather than being static attributes of individuals. His insight that the identity a person creates in interac-tion with others is not identical to the person creating it, captured by his terms ‘character’ and ‘performer’, is relevant to thediscussion below about the conflict Marion perceived between different aspects of her identity as a writer (see Ivanic, 1998pp. 98–105 for an application of Goffman’s theory to writing). Social constructionist theory (De Fina et al., 2006; Hall, 2000)provides a way of thinking about identity not as an individual state of being or a static attribute, but rather as a continuousprocess of identity formation or “identification” (see also Fairclough, 2003, for use of this term). This process takes place inspecific social interactions, such as producing or reading a written text, and the identities that result from it are fluid andmultiple, even contradictory. Holland, Lachiotte, Skinner, and Cain (1998) combine a cultural and social approach to issuesof identity in their theory of how identities form in practice, which includes literacy practices (Bartlett & Holland, 2002).They develop a distinction between personal and social identities and suggest the importance of timescales by noting that

‘Forming an identity on intimate landscapes takes time, certainly months, often years. . .. . .Forming an identity onsocial landscapes also takes time – public and institutional time.’ (Holland et al., 1998:285).

A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234 227

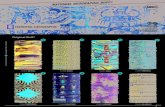

Fig. 2. The discoursal construction of writer identity: aspects and relationships (from Burgess & Ivanic, 2010).

As I have already noted, researchers have recently begun to consider how identity forms and changes over time. Lemke(2002), for example, argues that identities unfold over multiple timescales. He also points out that although identity maybe in a continuous state of flux, individuals do nevertheless develop the sense of relatively stable, coherent and recognisableidentities, and they do so by integrating processes which unfold over different timescales:

‘Like most everything else, [identity] too requires integration across timescales: across who we are in this event andthat, at this moment or the other, with this person or another, in one role and situation or another.’ (2000 p283)

In order to understand identity as a process, we therefore need to consider the interplay of different timescales. Theframework proposed by Burgess and Ivanic (2010) does this by mapping aspects of identity onto four timescales proposedby Wortham (2003, 2008). The first of these is the ‘sociohistorical’ timescale, or the decades and centuries over which widelycirculating ‘categories of identity’, such as ethnicity, gender or social class, will persist and change. Second, individualsdevelop their own unique identities over the months and years of ‘ontogenetic’ timescales. In doing so they draw on, andmay also contribute to the development of, ‘configurations of sociohistorically circulating categories’. The third timescalerelates to ‘mesolevel contexts’, which in formal educational settings include the ‘distinctive activities, structures, and styles’of individual classrooms which exist and develop over weeks, months and years. The fourth timescale is characterised byWortham as the ‘microgenetic level’, which includes processes lasting seconds, minutes and hours. Processes occurring onsociohistorical, ontogenetic and mesolevel timescales only exist empirically at the microgenetic level and must therefore beinferred from particular events and acts. Wortham argues that ‘an adequate analysis must consider several processes andtheir interrelations, instead of focusing on “macro”, or “micro”, or a simple relation between the two’ (2008:310).

4. Processes of identification in an act of writing

Fig. 2 is Burgess and Ivanic’s (2010) diagrammatic representation of the different aspects of writer identity which comeinto play during a single act of writing or reading. In this section I provide an overview of the framework as a referencepoint for the detailed discussion of data which follows. Rather than explaining the framework as a set of abstract concepts,I use the categories it presents to begin building up a picture of Marion’s identity as a writer. Since this framework has beenelaborated in detail in Burgess and Ivanic (2010), I will provide a summary and the concepts will be illustrated as I use themto analyse the data. The particular timescales relevant to each aspect of identity are not shown on the diagram, but I willrefer to them in the explanation below.

socially available possibilities for selfhood: These are the identities, or subject positions, inscribed in the discourses Marionencountered in the various contexts in which she participated. They exist as possibilities in social space and are realised inindividual lives. In other words, they circulate on the sociohistorical timescales identified by Wortham (2003) and, whentaken up in mesolevel contexts, they become part of people’s actual identities, which exist on ontogenetic timescales. Thepossibilities for selfhood available to Marion would include her gender, her status as a retired person, as well as more specificidentity possibilities such as ‘China Buff’. Her decision to enrol on the course also co-opted her into the identity of one ofthe ‘seven million adults’ defined (at that time) by the UK government as being in need of literacy education (DfES, 2001a,2001b), although it is important to note that she had not freely or even consciously chosen this identity. When producing herwriting about China, Marion was also exposed to the identity possibilities inscribed in the discourses, practices and genrescirculating within the literacy class, as I explain further below.

228 A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234

the autobiographical self of the writer: This is the sense of who she was which Marion brought with her to the act of writingand which was the unique product of her life experiences up to that point. In addition to this past-oriented dimension, itcontained a future-oriented dimension, encompassing the identity to which Marion might aspire (or indeed, wish to avoid)in the future. It included her sense of herself as a writer, but also other aspects of identity which can interact with writeridentity. This aspect of identity exists on the timescale of the human lifespan, characterised by Wortham (2003:229) as ‘onto-genetic time’. The autobiographical self (‘ontogenetic categories’ in Wortham’s terms) develops and changes in mesoleveltime. My data suggest that an important part of Marion’s autobiographical self was her relationship with her children andgrandchildren and her ambition to write the story of her life for them to read. She also saw herself as someone who hadwasted time at school and who had a ‘ruling passion’ (Barton & Hamilton, 1998:18) for China. Marion’s autobiographical selfalso included her repertoire of habitual writing practices, including the genres with which she was familiar. These includedpersonal genres, such as the journal she had kept intermittently over many years, and other types of writing which shedescribed as ‘creative’.

the discoursal self: This is the version of herself that is inscribed in Marion’s text. It is the representation of her self, herview of the world, her values and beliefs, which she constructed through her writing practices, her choices of wording andother semiotic resources. The discoursal self is formed in the interaction between the self the writer brings to the text andher assumptions about how she will be perceived by the reader. It is constructed on the microgenetic timescale of the actof writing and constitutes a set of signs which the reader later interprets to form an impression of the writer (the perceivedwriter: see below). The discoursal self cannot be said to be definitely this or that: it varies according to how the writing isread. In what follows I will focus mainly on Marion’s own view of her discoursal self, in particular the disjuncture betweenthe representation of herself that she wanted to construct and the one which she felt she actually had constructed.

the authorial self: This is the presence Marion constructed for herself as author of the text. It refers to the extent to whichshe felt able to claim authority for what she wrote and to convey that sense of authority to her reader. As I will argue below,it was Marion’s perception of the discoursal self and authorial self she had constructed that seemed to be the source of herdissatisfaction with her writing.

the perceived writer: As well as reading the subject-matter in the writing, the reader also ‘reads’ an impression of Marionfrom her writing, thus creating the fifth version of her identity: the perceived writer. Although Fig. 2 represents the perceivedwriter as a single aspect of identity, it may be helpful to differentiate between two ways in which it operates. The actualperceived writer is the impression of the writer which the reader forms when reading the text, while the anticipated perceivedwriter refers to the writer’s prediction (at the time of writing) about how the anticipated reader will perceive her. In Fig. 2the latter is represented by the arrows labelled (d) linking the perceived writer to the discoursal self and the authorial self. Eachact of reading the text and forming an impression of the writer will take place on a microgenetic timescale, but this aspectof writer identity will persist on ontogenetic and mesolevel timescales while readers remember their impression of Marion.The anticipated perceived writer is similarly created on the microgenetic timescale of writing, but will persist on ontogeneticand mesolevel timescales in the writer’s memory.

5. The construction of Marion’s identity in the act of writing

In this section I use the framework represented by Fig. 2 to explore how Marion’s identity was constructed within theact of writing the piece about China. By focusing on the arrows in the diagram, it is possible to see how the different aspectsof her identity interacted with one another and how the moment of writing was therefore temporally extended to includeprocesses of identification occurring on multiple timescales. The first two sections, discussing arrows (a) and (b) respectively,look backwards in time and consider the aspects of identity that pre-existed the moment of writing.

5.1. The role of socially available possibilities for selfhood in shaping Marion’s autobiographical self

Arrow (a) represents the way in which Marion has been exposed to a variety of discourses and has incorporated some ofthem into her personal repertoire of ways of acting and being: her autobiographical self. It thus represents the coordination ofsociohistorical and mesolevel timescales with an ontogenetic timescale. The data provide evidence of several discourses, or‘identity kits’ in Gee’s (1996) terms, which were particularly salient for the sense of herself as a person which Marion broughtto the task of writing about China. The first of these, which I will call a ‘fascination with China’ discourse, originally becameavailable to her at school, where she would have begun to incorporate it into her own repertoire of ways of acting and being,making it part of her autobiographical self. In adult life, she has continued to draw on the identity possibilities embedded inthis discourse in the mesolevel contexts of activities such as reading about China, undertaking a home decoration projectand learning calligraphy. This aspect of her autobiographical self has therefore developed over many years and continues tobe sustained and changed by her current practices. In contrast to this discourse, is a ‘China buff’ discourse which Marionactively wished to avoid and which she suggested would be instantiated by being ‘knowledgeable’ and writing in whatshe described as a ‘factual’ and ‘stilted’ way that would be suitable for a history lesson. One of the most salient discoursescirculating within the class while the writing was being produced was a tourism discourse, materialised in the brochuressupplied by Sheila and her words to the students: ‘This is your chance to dream.’ Marion was also exposed to this discoursethrough the internet sources she used, which were websites of companies selling holidays in, or travel guides for, China.Also exerting a powerful influence were the discourses of literacy and writing underpinning Skills for Life, the government

A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234 229

policy for adult literacy education in England. I return to this point in the discussion of Sheila’s expectations about Marionas a writer in Section 8 below, but here it is interesting to note that, since Marion had only recently joined the class, this wasstill a new aspect of the identity she brought to the act of writing in question.

When Marion drew on the possibilities for selfhood embedded in these discourses, she did not merely reproduce them;rather they were combined in a way that was unique to her and each one was subtly changed in the process. The mesolevelcontext and timescales of the class also exerted an influence on the way in which she drew on the discourses. When shewas reading about China and decorating her home she was taking up identity possibilities inscribed in the ‘fascination withChina’ discourse. However, although she also took up these possibilities in her writing, within the context of the class thisdiscourse was mingled with, and modified by, other discourses that were not present outside the class.

5.2. The role of Marion’s autobiographical self in shaping her discoursal self and authorial self

The two arrows (both labelled b) from the autobiographical self of the writer to the discoursal self and the authorial selfrepresent the way in which Marion drew on her personal repertoire of possibilities for self-hood in the act of writing andthus represent the co-ordination of ontogenetic and microgenetic timescales. The data suggest that a number of aspects ofMarion’s autobiographical self could have influenced the kind of discoursal self she constructed. Her ‘ruling passion’ (Barton& Hamilton, 1998), for China exerted a particularly strong influence and made her wish to engender similar feelings in herreader. Her dislike of the ‘China buff’ identity, which she mentioned in the context of her interests outside the class, alsoseems likely to have influenced the way she sought to represent herself in her text, although her criticism of her writingsuggests that she did not feel she had been completely successful in resisting this kind of identification.

In her interview she alluded to another aspect of her autobiographical self which would have been relevant to this writingactivity – her strong belief that she had a natural talent for writing. She stated that ‘I’ve always wanted to write but I don’tknow WHAT I want to write, I just know even as a child I always wanted to write’ and that, ‘I think if you can paint you canpaint, if you can draw you can draw, if you can write you can write . . .. . .. . .. . ..I think it’s there, I get quite excited about it’.She went on to describe how her love of reading made her wish to emulate professional writers: ‘You know if you’ve pickedup a book and you can’t put it down, it’s so, you know it just absorbs you and you think, what I would give to be able to writelike this – but I think that’s something you’re born with.’ In contrast to Marion’s sense of herself as a ‘born writer’ was hersense of herself as someone who had ‘messed about’ at school and who, as she wrote in another piece in the literacy class,now needed to ‘get back to basics’. In her interview she told me ‘I don’t think I’ve got the skills what I need, new skills ofhow to put things down.’ This facet of her autobiographical self formed a large part of her motivation for joining the classand thereby placing herself in a student–teacher relationship with Sheila, an aspect of her identity which is crucial to theact of writing about China.

As I have noted above, Marion’s autobiographical self contained a future-oriented dimension and she also drew on thiswhen producing her writing about China. The task required students to imagine a hypothetical future in which they wouldvisit their chosen country, thus offering them a hypothetical identity associated with this future. This imagined autobio-graphical self provided an important resource for the construction of Marion’s discoursal and authorial self, although, for her,it was unlikely ever to become real.

5.3. The role of the perceived writer in shaping Marion’s discoursal self and authorial self

The two arrows labelled (d) in Fig. 2 linking the perceived writer to the discoursal self and the authorial self show how thefuture came into play during the act of writing. They represent the way in which Marion took into account her predictionsof her reader’s values, beliefs, interests and relative status. The extent to which her anticipation of Sheila as reader affectedher discoursal self and authorial self was influenced by the relations of power between them. It is important to rememberthat the only audience for this piece of writing was Sheila and that Marion knew that it would be used to assess her progressin the class. This positioned her as lacking in authority compared with her reader, although she was actually more of anauthority on the topic of the writing.

To summarise the argument so far, Marion’s description of her feelings about her writing suggests that the source of herdisappointment lay in the kind of discoursal self and authorial self she thought she had conveyed. She appeared to havea clear idea of which aspect(s) of her autobiographical self she wished to draw on and of the discoursal self she wished toconstruct. However, she criticised her writing for being “too stilted and too factual” and said it would be suitable for a historylesson but would not persuade the reader to visit China, which had been her aim in writing it. She seemed to feel that thediscoursal self she had conveyed was the “China Buff” (who would inhabit an intellectual discourse and write a “factual”piece), rather than the person with “fascination” and “enthusiasm” for China, whose writing would make the reader wantto visit China.

Although she had a range of possibilities to draw from when constructing her discoursal self and authorial self, her agencyin choosing among them was constrained. As Ivanic (1998) points out, any given social context will support a particularpattern of privileging among available possibilities for selfhood, with some being valued more highly than others, and somebeing excluded completely. In the next section I discuss the possibilities for selfhood that were privileged, or otherwise, by

230 A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234

China is situated in eastern Asia, bounded by the Pacific in the east. The th ird largest country in

the world, next to Canada and Russia, it has an area of 9. 6 million sq uare kilometers, or one-

fifteenth of the world's landmass. It begins from the confluence of the Heilong and Wusuli

Rivers (135°5' east longitude) in the east to the Pa mirs west of Wuqia County in Xinjiang Uygur

Autonomous Region (73°40' east longitude) in the west, with about 5,200 kilometers apart. In the

north, it starts from the midstream of the Heilong River north of Mohe (53°31' north latitude) and

stretches south to the southernmost island Zengmu'ansha in the South China Sea (4°15' north

latitude), with about 5,500 kilometers in between.

Fig. 3. Extract from ChinaTour.com website.

the genres and texts circulating in the class. I argue that the particular pattern of privileging may have constrained Marion’sagency, making it difficult for her to resist the identity of ‘China buff’.

6. Constraints on Marion’s agency in choosing among available possibilities for selfhood

Sheila introduced the writing activity by telling the students that they were going to write about a country they wouldlike to visit, using travel brochures and information downloaded from the internet to find out about their chosen country.After the initial explanation of the task, most of the time allocated to generating ideas was spent on reading and selectinginformation from the brochures and websites. Consequently, these texts occupied a central role in the activity. In Marion’scase, her supporting texts consisted entirely of the websites she accessed, since none of the brochures advertised holidays inChina and Marion did not refer to the library books she mentioned in her interview. It is therefore likely that the possibilitiesfor discoursal self and authorial self encoded in the web pages she downloaded would have exerted a particularly stronginfluence on her.

The extract shown in Fig. 3 is taken from the homepage of one of the websites Marion used. It contains fairly long sentenceswith multiple subordinate clauses, and presents a series of facts as objective truths by using the simple present tense andincluding a relatively large amount of statistical information. As such, it is closely related to the essayist literacy valuedin formal education settings. In this respect it differs markedly from the majority of tourist websites, which use stronglypersuasive language in order to promote the places they describe (Hallett & Kaplan-Weinger, 2010). Although the linguisticfeatures of this homepage convey a strong sense of authority, it could be seen as lacking the ‘passion’ for China that Marionwanted to convey. In addition, the discoursal self and authorial self represented here could be described as aspects of the‘China buff’ identity which Marion wished to eschew. Despite these potentially unappealing (to Marion) features, this extractappears to have served as a model for Marion’s opening paragraph. In fact, her own statement that China is bordered byCanada seems to be the result of her misreading the second sentence.

The next six paragraphs of her writing are much less ‘factual’ than her opening paragraph and are closely modelled onthe website of a company called Premier Holidays. Fig. 4 shows the first section of the company’s homepage, reproduced asit appears on the website.

In contrast to the first extract, this is a clear example of the promotional writing usually found in holiday brochures andwebsites. It contains a number of the linguistic features identified by Maci (2007) as typical of the genre. For example, it adoptsan informal style in order to create the illusion of a friendly relationship between the website’s producer and the reader. Inaddition, it represents China as a highly distinctive destination, somewhere very different from the places with which thereader is likely to be familiar. Maci (2007) identifies particular attributes – some of which are represented in the above extract– which are frequently assigned to destinations on tourist websites in order to create this sense of distinctiveness: continuity(ancient, traditions); novelty (new, startling, surprised, surreal, adventure); exclusiveness (unparalleled); and attractiveness(attractions, splendor, paradise). Although it is still impersonal to the extent that the author(s) remains anonymous andmakes no reference to her/his/their own opinions, interests or experiences, its other linguistic features are consistent withMarion’s aims for her own writing. For this reason it may have been more attractive to her than the first extract, although itdid not offer the possibility of conveying her passion and enthusiasm for China in a personal way.

Marion shifts genre again in the final sentence of her text, which reads like the kind of traditional essay she might havewritten in her schooldays. Sheila regularly referred to writing assignments as ‘essays’ and told me that she deliberately

Travell ers from all ove r the world visit China to soak up its unpar all eled cu ltural a� rac�ons, althoughmany ar e surprise d to discove r how modern it has become. Of co urse, th e anc ient with all its tradi�onsand spl endou ris s�ll ther e in ab unda nce, bu t nowa days it sits alon gsi de the new crea� ng startling, ando�en surreal, contrasts righ t across th e country. Chin a is fa r from being a holida y des�na�on – it is atravell er’s paradise and on e oflife’ s truly great adventures. There’ s no other experience lik e it !

Fig. 4. Extract from Premier Holidays website.

A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234 231

used this word to ‘take the fear out of it’ because she knew that it often has negative connotations for literacy students.She was aware that most of the students would be continuing on to other courses in the college, where assignments wouldbe referred to as ‘essays’, and wanted them to become accustomed to thinking of their writing in this way. It is thereforehighly likely that Marion would have drawn on her knowledge of this genre when producing her writing about China. As thestandard genre used in formal education settings, the essay offers the subject position of student or pupil. In Marion’s mindit appeared to be strongly associated with memories of school, since she explicitly referred to the writing she had done atschool as ‘essays’. However, the data show that a student identity was problematic for her. For example, in another writingassignment she explained that she had not succeeded at school because she lacked discipline and concentration, and shedescribed feeling out of place in the college. So it seems likely that the (implicit) requirement to write an essay reduced heragency as a writer by co-opting her into an identity she associated with lack of achievement. Her agency may have beenfurther reduced by the lack of explicit teaching about the characteristics and uses of the essay genre, since this resulted inher being unable to reflect consciously on her own use of it.

Another text which exerted a powerful influence on the writing activity – although it was not physically present in theclassroom and never explicitly mentioned – was the Adult Literacy Core Curriculum (DfES, 2001). Sheila, like all adult literacytutors on publicly funded programmes, was expected to cross-reference each classroom activity mentioned in her sessionplan to one or more elements of the Core Curriculum. In the version of the Core Curriculum in use at the time of the fieldworkthere is a lack of distinction between purpose and genre in writing, and this may have created further difficulties for Marion.The concept of purpose is introduced in the Reading section, where students are required to understand that texts havedifferent purposes, and five such purposes are listed: inform, explain, instruct, entertain, describe, persuade. However, theexamples given are in fact examples of different genres: newspaper, telephone directory, computer manual, tourist informa-tion leaflet. In the Writing section of the curriculum, at text level, several of the elements refer to the need for writers to takeaccount of purpose, context and audience. For example, at the level these students were working at (Entry Level 3), one of theelements requires writers to ‘understand that the choice of how to organise writing depends on the context and audience’.However, the example given for this element is to ‘plan and draft their own writing to a satisfactory final standard for the task,e.g. a letter to teacher explaining they are going on holiday; a story or poem for a college or community magazine’, which againare examples of genres. At Entry Level 3, the word ‘genre’ is used only once, in a text box giving advice on the use of writingframes. The ‘Skills, Knowledge and Understanding’ at text level at E3 do not include any reference to different genres. SinceSheila was using the Core Curriculum to guide her planning, it is perhaps not surprising that the same confusion was evidentin the classroom activities I observed. In an interview she told me that the aim of the travel writing was to enable studentsto improve their descriptive writing, which relates to purpose. When she introduced the task she told the students that theyneeded to make the writing ‘descriptive’ and ‘interesting’ so that it would persuade someone to visit their chosen country.The source material provided a strong steer to write in the style of holiday brochures and websites, and all the students choseto do so. However, they were given no guidance about genre and there was no explicit discussion of the generic features oftheir source texts. In Marion’s case, this uncertainty seems likely to have contributed to her disappointment with the text sheproduced.

7. The construction of Marion’s identity in the act of reading

In the next sections I move on to consider the aspects of Marion’s identity as a writer which are represented in the lowerhalf of Fig. 2; in other words I move from the act of writing to the act of reading. The reader (in this case Sheila) just like thewriter, co-ordinates processes that exist on multiple timescales in order to create her own version of Marion’s identity, theperceived writer. The act of reading, like the act of writing, has past, present and future dimensions.

The act of reading mirrors the act of writing; it constitutes the second part of a cycle which begins with the writer,in this case Marion, incorporating socially available possibilities for selfhood into the autobiographical self which shethen draws on in order to create a discoursal self and an authorial self in the act of writing. In the act of reading, thereader, Sheila, interprets Marion’s discoursal and authorial self to create the perceived writer (represented by the twoarrows labelled (f) in Fig. 2). This perceived writer then becomes one of the possibilities for selfhood to which Sheila hasbeen exposed and which will thus be available to her in her own writing in future. The socially available possibilities forselfhood to which Sheila has been exposed will set up expectations in her mind as to appropriate writer-characteristicsfor this piece of writing. As was the case for the act of writing, these possibilities for selfhood exist on relatively longsociohistorical timescales which transcend the act of reading. Sheila had previously encountered the possibilities forselfhood inscribed in conventional discourses of tourism and incorporated them into her autobiographical self. Sheassumed that the students were also familiar with, and valued, such discourses and that it would therefore be easyfor them to take on the prototypical subject-positions inscribed within the genre of travel brochures and websites.Her expectations, although not stated explicitly, were quite definite; in her interview, for example, she made it clearthat she felt all the students would find the task accessible and enjoyable:

S: Everyone wants the chance to dream, so why shouldn’t they write about something that they would like to dreamabout? . . .. . .. . ..It gives them motivation.

232 A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234

Sheila’s interview provides evidence of how she might have perceived Marion as a writer. She did not talk about Marionindividually, but made several comments about all her students:

S: My aim for them is . . ... to develop confidence in writing . . ... that’s my priority because all of them want to go onto do higher courses . . .. and they need confidence in their own ability to write and by the end of this term I wantthem to have produced a reasonable essay at least one A4 page of descriptive writing . . .. . .they’re coming in, they’renervous, they’re new, they don’t know what to expect. You’ve got to make what they do INTERESTING, you’ve got tomake it appeal to them.

In this extract Sheila suggests that she views the students as needy (they lack confidence, which she can help them togain) and deficient (they lack essayist literacy skills, which they need to develop if they are to go on to other courses.) Thisview is somewhat at odds with the more complex picture of her capabilities as a writer which Marion herself expressed. Onthe one hand, her view accorded with Sheila’s to the extent that she felt she needed ‘new skills of how to put things down. . .. . .. I think it’s going back to basics, getting down to grassroots.’ On the other hand, she did not conform exactly to Sheila’sexpectations because she had considerable confidence in what she saw as her natural talent for writing.

8. The way the writing contributes to shaping future socially available possibilities for selfhood

In Fig. 2 arrow (h) links the autobiographical self of the reader with socially available possibilities for selfhood. It shows howthe impression of Marion formed by Sheila in the act of reading (the perceived writer) had the potential to become part ofthe set of possibilities for selfhood available to Sheila and, through her, ultimately to other people. As Burgess and Ivanic(2010) point out, this enables us to see how an act of reading taking place in microgenetic time is co-ordinated with thedevelopment of the reader’s autobiographical self in ontogenetic time, as well as playing a part in sustaining, refining andchallenging possibilities for selfhood which circulate in mesolevel and sociohistorical time. Marion, like any other individual,is sometimes a reader and sometimes a writer. The interplay between her reading and writing experiences, as well as otheraspects of her life, constructs and changes her identity as a writer in ontogenetic time. Marion has previously encountered arange of possibilities for selfhood, identifying more closely with some than with others, and actively rejecting some, such as the‘China buff’. In producing her writing about China, she has drawn on some of these possibilities for selfhood willingly becauseshe found them attractive, whilst drawing on others (such as the identity of student) because it is in her own interests todo so in the social context of the literacy class. The unique recombination of possibilities for selfhood she has created in hertext conveys an image of her to Sheila, and at the same time adds to the pool of possibilities for selfhood to which Sheilahas been exposed. However, it seems unlikely that Sheila would see this writing as contributing to the wider circulationof discourses or that she might try to identify herself with Marion by writing in a similar way. As far as I was able to see,Sheila was not interested in finding out about China and regarded Marion’s text as a linguistic object, rather than a vehiclefor information or enjoyment. This is confirmed by her answer to one of my interview questions about how she planned toassess the students’ writing:

I: Can I ask about the piece of work they’re doing now? When they’ve finished that and they hand it in, how will yoube assessing it?S: I’ll be checking on their spelling and punctuation obviously and the content of their work.I: How will you judge the content?S: The content, as you know we’ve been doing the grammar, we’ve been doing the nouns and adjectives, so I’ll wantto see plenty of that. I’ll want to see plenty of descriptive stuff in there. In the past we’ve already done some spellingrules and punctuation and a lot of them come to the writing workshop anyway, so I’ll be checking the spelling andpunctuation and their paragraphing probably . . .. As I said, the content, you know, whether they’ve made it descriptiveenough, and picking out things that they might fall down slightly on, so that I know that’s something we need morework on.

In order to understand Sheila’s response to Marion’s writing, I turn now to considering the discourses shaping her identityas a writing teacher. Some of the most powerful of these discourses entered the local setting through the texts and practicesassociated with Skills for Life, the government policy which has set the context for adult literacy education in England overthe past decade. Other studies (Hodgson, Edward, & Gregson, 2007; Cara, Lister, Swain, & Vorhaus, 2010) have describedthe position of Skills for Life practitioners, who have been excluded from the policy making process, yet find themselvescoping with its sometimes negative consequences in their daily lives. Hamilton (2009) discusses how aspects of the policyconstruct practitioners’ identities by co-opting them as active agents into its systems and processes. Sheila’s identity as aliteracy teacher was powerfully shaped by the discourses underpinning Skills for Life, which conceptualises literacy primarilyas a set of decontextualised technical skills. Such discourses are clearly evident in the content and design of the NationalLiteracy Test, which the students were expected to take at the end of the academic year. This multiple choice test emphasisesthe technical aspects of writing by requiring students to identify incorrect spelling, punctuation and grammar in short textsand then select the correct versions from a list of alternatives. It does not require them to produce any writing of their own.Sheila was well aware that her own performance as a teacher would be partly judged by the number of students who passedthis test. She also knew that the college as an institution was under pressure to achieve high pass rates, as this would be used

A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234 233

to determine the level of government funding it received. It is therefore not surprising that her teaching and assessmentpractices focused on the technical aspects of writing.

9. Conclusion: identity, discourses and time

Mercer (2008) points out that a temporal analysis is essential to a full understanding of educational outcomes. Heintroduces his discussion of learning across timescales with the following quotation from Macbeth

If you can look into the seeds of timeAnd say which grain will grow and which will notSpeak, then, to me . . .. (Macbeth, Act 1, Scene 3)

In this article I have used the framework developed by Burgess and Ivanic (2010) as a microscope for examining the‘seeds of time’ contained within one act of writing. I have argued that a single ‘act’ or ‘moment’ of writing involves theco-ordination of processes which occur on different timescales and is thereby temporally extended to include the pastand the future. An understanding of learning as a temporal process therefore needs to include an understanding of ‘acts’or ‘moments’ as temporally extended in this way. I have shown that by examining the interplay of different aspects ofidentity and different timescales within an act of writing it is possible to understand the opportunities for, and constraintsupon, identity development presented by that act. Using this analytical framework has enabled me to construct a dynamic,processual picture of writer identity by showing how its different aspects interact with each other and to begin to answerthe question posed by Lemke:

‘[H]ow could events on the timescale of a conversation or an experiment or reading a story . . .. contribute to identitydevelopment?’ (Lemke, 2000:283 emphasis in original.)

In common with teachers across educational sectors and settings, Sheila was expected to produce a scheme of work at thestart of each new term and from that to write a plan for each session according to a standard format used in the college. Eachsession plan itemised the particular ‘learning outcomes’ which were expected to result from the planned activities. Learningoutcomes were written in the form of a list of specific things the students were expected to be able to do by the end of thesession. This approach to lesson planning makes sense because learning is a cumulative process (Mercer, 2008). However, itprivileges a model of learning as the predictable product of input, which, as Ivanic and Tseng (2005) point out, is inadequate.A similar argument is advanced by Slattery (1995). In my view, this model obscures the importance of events happeningon very different timescales from the lesson itself (Lemke, 2001). The identity development that took place when Marionproduced her text was not simply the outcome of the classroom activities that had led up to it. Events from the distant past,such as her schooldays, as well as anticipated future events, such as her predictions about her reader’s likely response, werejust as important as retrieving information from websites, and possibly more important than some other classroom eventsthat occurred in the hours and weeks before the writing was produced. Ivanic and Tseng (2005) argue that teaching is bestunderstood as the creation of ‘learning opportunities’ and I would add that in order to create, and enable their students toexploit such opportunities, teachers need to understand the temporal dynamics of classroom activities and interactions.

As I noted earlier, there is a strong tradition of personal writing in adult literacy education which is still flourishingtoday. Sheila sought to align her teaching with this tradition by adopting an approach which placed strong emphasis on theautobiographical aspect of a writer’s identity. Although this sort of personal writing can be beneficial because it validates theexperiences of people who are often marginalized in society and can enable them to develop a ‘voice’, in practice a slippagecan occur, so that ‘personal’ comes to be equated with the writer’s autobiographical self. Pedagogy which gives primacy tothis aspect of writer identity is past-oriented in that it focuses mainly on what learners bring to the act of writing; it doesnot encourage them to think about the discoursal and authorial self that is created in the moment of writing, nor does itinvite consideration of the future reader’s needs and possible response. It also downplays the cognitive aspects of writingdevelopment and privileges the affective elements, in this case, confidence. However, Marion’s assessment of her completedtext suggests that her confidence had not increased as a result of producing it.

An approach to teaching writing which focuses only on the autobiographical self may produce some personal development,but I argue that such development will be limited and is unlikely to match the aims for writing pedagogy advocated byGaber-Katz, to which I alluded earlier: namely, to enable adults ‘to understand themselves better as individuals and as partof society, and to envision and participate in the transformation of society’ (Gaber-Katz, 1996:49). My analysis has shownthat such aims were not supported by the curriculum and assessment system with which Sheila was required to workand it is not surprising therefore, that they were not reflected in her practice. Furthermore, whilst teaching that focuseson the autobiographical self may foster some (limited) personal development, I argue that development as a writer entailsdeveloping greater understanding of, and control over, all aspects of writer identity. This is necessary if writers are to developthe confidence which Sheila aimed to foster, but which eluded Marion. A rich and balanced pedagogy therefore needs toencompass explicit teaching about each aspect of identity and its relation to the others because, as Ivanic points out

‘Not only is [identity] a significant factor in any act of writing . . .. . . but it also connects a particular act of writing tothe bigger picture: discussing the writer’s identity places an act of writing in the context of the writer’s past history,of their position in relation to their social context, and of their role in possible futures.’ (Ivanic, 1998:338)

234 A. Burgess / Linguistics and Education 23 (2012) 223– 234

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the following colleagues for providing comments on an earlier draft of this paper: Professor Mary Hamilton,Dr Bill Muth, Professor Debra Myhill, Dr Karin Tusting.

References

Adam, B. (1990). Time and social theory. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.Adam, B. (2004). Time. Key concepts. Cambridge: Polity Press.Adam, B. (1995). Timewatch: The social analysis of time. Cambridge, UK; Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.Bartlett, L., & Holland, D. (2002). Theorizing the space of literacy practices. Ways of Knowing, 2(1), 10–22.Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (1998). Local literacies: Reading and writing in one community. London; New York: Routledge.Bloome, D., Beierle, M., & Grigorenko, M. (2009). Learning over time in a ninth grade language arts classroom: Social construction of collective memories

and classroom chronotopes. Language and Education, 23(4), 313–334.Burgess, A. (2008). The literacy practices of recording achievement: How a text mediates between the local and the global. Journal of Education Policy, 23(1),

49–62.Burgess, A. (2010a). Doing time: An exploration of timescapes in literacy learning and research. Language and Education, 24(5), 353–365.Burgess, A. (2010b). The use of space-time to construct identity and context. Ethnography and Education, 5(1), 17–31.Burgess, A., & Ivanic, R. (2010). Writing and being written: Issues of identity across timescales. Written Communication, 27(2), 228–255.Cara, O., Lister, J., Swain, J., & Vorhaus, J. (2010). The teacher study: The impact of the skills for life strategy on teachers. London: NRDC.De Fina, A., Schiffrin, D., & Bamberg, M. (2006). Discourse and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.DfES. (2001a). Adult literacy core curriculum. London: DfES.DfES. (2001b). Skills for life: The national strategy for improving adult literacy and numeracy skills. Department for Education and Skills: DfES.du Gay, P., Evans, J., & Redman, P. (2000). Identity: A reader. London: Sage.Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse. London: Routledge.Gaber-Katz, E. (1996). The use of story in critical literacy practice. Gender and Education, 8(1), 49–60.Gee, J. (1996). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses (2nd ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. (original work published 1990).Gee, J. (2001). Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Review of Research in Education, 25, 99–125.Gillespie, M. (2007). The Forgotten R: Why adult educators should care about writing instruction. In A. Belzer (Ed.), Toward defining and improving quality

in adult basic education (pp. 159–178). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Goffman, E. (1969). The presentation of self in everyday life. London: Penguin.Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. Oxford: Blackwell.Hall, S. (2000). Who needs identity? In P. du Gay, J. Evans, & P. Redman (Eds.), Identity: A reader (pp. 15–30). London: Sage.Hallett, R., & Kaplan-Weinger, J. (2010). Official tourism websites: A discourse analysis perspective. Bristol: Channell View Publications.Hamilton, M. (2009). Putting words in their mouths: the alignment of identities with system goals through the use of Individual Learning Plans. British

Educational Research Journal, 35(2), 221–242.Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (1983). Ethnography: Principles in practice. London: Routledge.Hodgson, A., Edward, S., & Gregson, M. (2007). Riding the waves of policy? The case of basic skills in adult and community learning in England. Journal of

Vocational Education and Training, 59(2), 213–229.Holland, D., Lachiotte, W., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Ivanic, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Ivanic, R. (2005). The discoursal construction of writer identity. In R. Beach, J. Green, M. Kamil, & T. Shanahan (Eds.), Multidisciplinary perspectives on literacy

research (pp. 391–496). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.Ivanic, R., & Tseng, M. (2005). Understanding the relationships between learning and teaching: An analysis of the contribution of applied linguistics. London:

National Research and Development Centre for Adult Literacy and Numeracy.Ivanic, R. (2006). Language, learning and identity. In R. Kiely, P. Rea-Dickens, H. Woodfield, & G. Clibbon (Eds.), Languagr, culture and identity in applied

linguistics. London: BAAL/Equinox.Ivanic, R., Edwards, R., Barton, D., Martin-Jones, M., Fowler, Z., Hughes, B., et al. (2009). Improving learning in college: Rethinking literacies across the curriculum.

London: Routledge.Leander, K. (2001). “This is our freedom bus going home right now”: Producing and hybridizing space-time contexts in pedagogical discourse. Journal of

Literacy Research, 33(4), 637–679.Leander, K., & Lovvorn, J. (2006). Literacy networks: Following the circulation of texts, bodies, and objects in the schooling and online gaming of one youth.

Cognition and Instruction, 24(3), 291–340.Lemke, J. (2000). Across the scales of time: Artifacts, activities and meanings in ecosocial systems. Mind, Culture and Activity, 7(4), 273–290.Lemke, J. (2001). The long and short of it: Comments on multiple timescale studies of human activity. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 10, 17–26.Lemke, J. (2002). Language development and identity: Multiple timescales in the social ecology of learning. In C. Kramsch (Ed.), Language acquisition and

language socialisation: Ecological perspectives. Continuum.Maci, S. (2007). Virtual touring: The web-language of tourism. Linguistica e Filologia, 25, 41–65.Mercer, N. (2008). The seeds of time: Why classroom dialogue needs a temporal analysis. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 17, 33–59.O’Rourke, R., & Mace, J. (1992). Versions and variety: A report on student writing and publishing in adult literacy education. Stevenage: Avanti Books.Satchwell, C., & Ivanic, R. (2010). Reading and writing the self as a college student: Fluidity and ambivalence across contexts. In K. Ecclestone, G. Biesta, &

M. Hughes (Eds.), Transitions and learning through the lifecourse (pp. 47–68). London: Routledge.Sfard, A., & Prusak, A. (2005). Telling identities: In search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educational Researcher,

34(4), 14–22.Slattery, P. (1995). A postmodern vision of time and learning: A response to the National Education Commission Report Prisoners of Time. Harvard Educational

Review, 65(4), 612–633.Wortham, S. (2003). Curriculum as a resource for the development of social identity. Sociology of Education, 76, 228–246.Wortham, S. (2008). The objectification of identity across events. Linguistics and Education, 19, 294–311.

Web referenceshttp://www.chinatour.com/ (Last accessed 08/02/2011).