Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan For the ... - Living · PDF fileHydrocotyle Weed Management...

Transcript of Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan For the ... - Living · PDF fileHydrocotyle Weed Management...

Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan For the Middle and Upper Canning River

Prepared for Perth NRM October 2015

Revised Final: January 2016

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | i

Executive summary Hydrocotyle ranunculoides (Hydrocotyle, Floating Pennywort) a native aquatic plant of South and Central Americas had been introduced to Australia through the aquarium trade in the early 1990s. The species found its way into the creeks that drain into the Canning River, WA, probably by inadvertent, aquarium waste dumping, and by 1993, had established dense infestations in many freshwater areas of the River, upstream of the Kent Street Weir.

A clonal species, with vegetative reproduction as its primary strategy for growth and colonisation, Hydrocotyle grew to dense infestations at most infested, freshwater locations, posing a major threat to ecological (environmental), social and economic values (i.e. recreational uses and other uses, such as irrigation and drainage) of the creek systems, Lagoons, Wetlands and the Canning River itself.

Following introduction as a new species to Australia, the absence of natural enemies in this new environment may have assisted its establishment over a relatively short period of time. However, as a freshwater species, Hydrocotyle has shown to be particularly sensitive to salinity; and its colonisation is strictly limited to creeks, lagoon and riverine habitat, which are fresh water. Major changes in hydrology and urban stormwater drainage, which have occurred in the region, over time, are probable factors in the spread and colonisation of the species.

Like most aquatic plants, Hydrocotyle responds readily to available nutrients and thrives in nutrient-enriched soft mud. Its luxuriant growth, extensive biomass production and entrenchment in lagoons and wetlands, such as the Wilson Wetlands, show that nutrient enrichment, resulting from urban runoff, are a contributory factor, assisting colonisation.

Information review

A significant amount of local research was undertaken between 1992 and 1996 to better understand the plant’s biology and ecology, as a basis for undertaking management efforts by multiple stakeholders, led by The Swan River Trust and the WA Department of Agriculture. Following reviews of influential factors affecting the spread of Hydrocotyle and available control options, management interventions were attempted at various infested locations with the mapping of infestation areas and integration of various control methods, including herbicides.

Control and eradication of existing infestations had been the goal of the initial management programs in the 1990s. The control methods were largely based on manual removal of small-to-medium sized infestations, in combination with herbicide treatments; and regular inspections.

In the mid-1990s, the herbicide of choice was the systemic and non-selective herbicide Glyphosate as its Round-up® formulation which contained the surfactant polyethoxylated tallow amine (POEA). Large-scale applications of these treatments were identified as potentially toxic to various amphibians, including frog species, due to the presence of this surfactant.

Public concern subsequently led to the registration of Bi-active® Glyphosate (Roundup Biactive®) in 1995-96, containing a substantially less toxic surfactant and was specifically designed for use in aquatic habitat. In WA and other Australian States, Round-up Bi-active® became a recommended option for use in waterways for control of problematic weeds.

Differences in opinion regarding ‘what works’ and ‘what does not’ have existed among stakeholder groups; and concerns about the potential overuse of herbicides have also been expressed by some community groups and agency stakeholders.

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | ii

The success and effectiveness of the overall management, undertaken with some degree of co-ordination across jurisdictions and stakeholders, has been variable and intermittent, due to insufficient funding and variable resources available to stakeholders for Hydrocotyle management within their jurisdictions. A low level of priority attached to Hydrocotyle management and inadequate co-ordination of the management effort may have also contributed to the risk of re-infestation of susceptible areas.

Hydrocotyle Working Group: The formation of a Hydrocotyle ‘Working Group’ in 1998, represented by various stakeholders and community groups, has had a significant positive impact in facilitating the management effort, including raising public awareness. Despite concerted efforts by the Group to coordinate action and eradicate the weed since the late-1990s, Hydrocotyle has continued to infest waterways within the Canning River region.

Recognising the continuing risk of re-infestation across a larger area and spread into new areas, stakeholders have sought and received additional funding to develop a Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan (Hydrocotyle WMP) following best practice Australian approaches and updated information on control from both WA and overseas.

Growth, Reproduction, Habitat and Environmental requirements

Knowledge of biology, ecology, habitat requirements and influential factors is important in planning the management of any problematic species. Hydrocotyle is an obligate freshwater species, without any particular preferences in terms of water velocity, water depth, bank slope, pH, dissolved oxygen or nutrients, thereby making it a generalist in its ecological response, within the limits of cool, freshwater bodies. Two distinct habitats favoured by Hydrocotyle have been identified where it can grow luxuriantly: these are high altitude tropical lakes of East Africa and South America (cooler climates); and low altitude coastal regions of the temperate zone of USA, South America, Australia and Europe.

Optimum photosynthesis occurs at temperatures between 25 and 35°C, and in high sunlight. Growth is fast in summer and in strong sunlight. Growth and regeneration rates of about 23 cm per day have been recorded overseas with biomass doubling every 3-7 days. The vegetative plant can remain relatively dormant over winter to avoid frost and low temperatures, and re-commence fast growth as temperatures rise and day length increases.

Hydrocotyle has relatively wide ecological amplitudes, tolerating a wide range of factors in aquatic environments - such as shade and nutrients - to varying degrees. It does not grow in water, and needs a substrate for rooting. Once established and rooted, it can produce mats or rafts that spread over water surfaces or moist riparian areas, building upon each layer. It is found rooted at the margins of lakes, ponds, ditches and slow-flowing canals and drainage ditches. The plant produces emergent leaves to 30 cm from the water surface; roots develop from every node of the stoloniferous growth form and the species can grow luxuriantly in eutrophic conditions. The species utilises both sexual reproduction by seeds and asexual reproduction by vegetative growth and fragmentation. Flowering and fruiting occurs in spring and summer and there is limited seed dormancy around 15 ºC (temperate species).

Vehicles of Spread: A range of vehicles cause Hydrocotyle to spread across catchments, waterways and continents by both seeds and other propagules (fragments). The species is introduced to new areas deliberately via the aquarium trade and can be spread through waterways via aquarium waste dumping and fragments carried downstream by flowing water. Spread can also occur via contaminated equipment.

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | iii

Current Infestation Levels

Recent surveys and mapping results indicate that the remaining colonies along the Canning River main channel (between the Kent Street Weir and Nicholson Road Bridge) and most of its shoreline areas are minor. Any remaining patches in the Mill Street Drain and Bannister Creek are also minor and quite small.

On the northern side of the River, major infestations still exist in the Wilson Wetlands and Lagoon complex, mostly located in the freshwater sections - Wilson 1 and 2. Hydrocotyle infestations vary in size, mostly in the range of about 25-50 m2; they are interspersed among Typha stands, or entrenched underneath Melaleuca trees. No Hydrocotyle exists in the saline, lower parts of the Wilson lagoon complex (i.e. Wilson 3).

Three lagoons on the southern side of the main river channel, alongside Marmot Way and their shorelines, have patchy, moderately-sized infestations. Those within the lagoons are floating mats, variable in size (mostly, 1-3 m2), located underneath the tree canopies.

Recent success in management

The review of recent results of the management program indicates that a very high degree of control and almost eradication of infestations has been achieved along the Canning River main channel and most shoreline areas either side of the channel, and in the Mill Street Drain and Bannister Creek. The high degree of success achieved has been due to regular (monthly) inspections, regular mapping and targeting of infestations, frequent manual removal where possible, and well-directed ‘spot’ treatments of herbicides.

In recent management efforts, the herbicide of choice has been the selective herbicide - Metsulfuron-methyl, to which Hydrocotyle is quite sensitive. The use of Metsulfuron has been preferred over Round-up Biactive®, because it affords a high degree of selectivity on native shoreline vegetation (mostly sedges and grasses).

Although Metsulfuron is not registered for aquatic use in Australia, its use for ‘spot treatments’ against Hydrocotyle (a declared pest species, to be controlled within WA) is covered by an off-label permit (PER 13333) obtained by the WA Department of Agriculture and Food.

To reduce herbicide use in waterways, preference has been to use the minimal effective dose (a quarter of the standard rate of Metsulfuron: 2.5 g active ingredient, per 100 L of water)1. In some instances, Metsulfuron has been mixed with Round-up Bi-active® (1 L/100 L), with which it is compatible. Spot treatments in the last few years have been either by motorised spray, or hand-held, knapsack spray. The use of a biodegradable vegetable oil surfactant (Endorse™, at 0.2% v/v) has made the treatments more effective, and in some upper riparian, terrestrial situations, the use of Pulse™ (an organo-silicone sticker) as an additive has also been effective.

Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan

Despite various efforts to control and eradicate Hydrocotyle from the Canning River region, the historical infestations have survived for more than 20 years, and have expanded their invaded territory in associated Lagoons and Wetlands. As a result, stakeholders have sought additional funding and resources to contain the threat posed by Hydrocotyle to other areas, and to control and eventually eradicate existing infestations.

1 The standard Metsulfuron label rate for general weed control is 10 g/100 L of water of the commercial product (600 g active ingredient, a. i./kg).

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | iv

Given the complex ecological nature of the infested waterway systems, and the different opinions and objectives of users and managers of those waterway assets, the development of the Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan (WMP) focussed on achieving a consensual approach to managing the weed in the affected areas.

The Hydrocotyle WMP was developed using the steps shown below. This included a review of historical research and management experiences, both in the Canning River region and overseas, and extensive stakeholder and community consultation, conducted through two facilitated workshops and one-on-one interviews.

Steps in developing the Hydrocotyle WMP Notwithstanding the differences of opinion on some issues, such as the potential impacts of herbicide use in waterways, the stakeholders agreed on the need to control and eventually eradicate Hydrocotyle from infested locations.

There was also consensus that – as in the past – Hydrocotyle management should be achieved using an integration of appropriate strategies and methods, with a preference for effective, non-chemical and environmentally-friendly methods.

Step 1 – Define the Goals and Objectives

Step 2 – Identify and Prioritise Weed/s

Step 3 – Map locations and extents of infestations

Step 4 – Research and review Biology, Ecology and Management of Weed

Step 5 – Set Priorities – What, Where and When?

Step 6 – Determine the best approach

Step 7 – Decide on Tools and Techniques appropriate for the Management Task

Step 8 – Develop Implementation Plan

Step 9 – Define how to Monitor and Report on Effectiveness

Step 10 – Define the process for future review

Strategic Approach

The strategic approach is one of adaptive management, which involves undertaking planned action against Hydrocotyle, learning from them and re-evaluating the effectiveness of management options, before re-implementing the control plans.

The strategic approach also recognizes that in Australia, best management of problematic species is all about tackling weed problems, not simply at the individual, local infestation level, but also at other scales, such as the management unit (e.g. conservation reserve, wetland, native vegetation remnant), catchment, landscape, waterway and the region as a whole.

This approach includes taking ‘direct action’, as well as ‘indirect action’ against contributory factors, integrating the following: (1) prevention, (2) eradication, (3) containment and (4) asset protection control activities – at times and places that make them most effective and efficient.

The Hydrocotyle WMP encompasses the following strategic weed management considerations:

Prevention of Hydrocotyle infestations to new areas through the vehicles of spread – either from new introductions; or from breakaway propagules;

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | v

Integrated weed control options2 – physical methods (i.e. manual and mechanical control), non-chemical methods (i.e. use of heat – steam and/or flame; manipulation of water flows, water levels, lake drawdown, and/or salinity management); cultural methods (i.e. re-vegetation; shading; weed matting; competitive planting) and chemical control.

The known ecology and biology of Hydrocotyle, including seed production, soil seed-bank, seed longevity, requirements for germination and establishment, vegetation reproduction (rhizomes and stolons); ease of fragmentation, and the plant’s growth attributes (biomass production and mat-forming nature);

The extent of the overall infestation and the densities of the populations and the economics and feasibility of control; and

The nature of the invaded environment, including that of non-target vegetation, as any control technique has potential side effects on the native flora and fauna.

Tactical Approach – Operational Management of Hydrocotyle

Information on the consequences of different weed management regimes upon biodiversity and environmental values of the Canning River and its associated waterways is generally inadequate. Despite this, the Hydrocotyle WMP makes an informed assumption (confirmed by stakeholders) that the positive benefits achievable for environmental, social and economic values in implementing the Hydrocotyle WMP are more desirable than the effects of the weed itself.

Stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder engagement is a crucial part of managing weeds in Australia. To achieve this, major stakeholders were engaged and consulted widely in developing the Hydrocotyle WMP. The following key visions were shared by all stakeholders:

Eradication of Hydrocotyle from the Canning River region; and

The continuation of positive and enduring stakeholder collaboration in managing Hydrocotyle in the Canning River regions.

Additional goals for the Hydrocotyle WMP, established by the stakeholders include: (a) Emphasise the application of non-herbicide control methods; (b) Empower the community to continue to deliver benefits for the Canning River environment; (c) Increase community awareness and education of aquatic weed problems; (d) Retain community enjoyment of the river environment; and (e) Ensure the Hydrocotyle WMP is a benchmark for aquatic weed management.

Site-specific Management and Implementation

Consideration of the nature and extent of existing Hydrocotyle infestations, as well as various site-specific considerations, were used in prioritising the infested areas for management action. Three important factors used for prioritisation were: (1) Potential for further spread within or beyond an infested area; (2) Consequences and the impact of on-going infestation; and (3) Management feasibility within a given management area.

2 The use of natural enemies as biological control has not yet been developed in Australia or overseas. However, future research on a bio-control agent may be warranted, given that it is a highly effective method against many aquatic weeds.

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | vi

Other important considerations were: knowledge of what combination of methods has worked and what has not; and which ‘Asset owners’ (agencies) have primary control responsibility.

The recommended management zones and priorities are as follows:

Management Zone 1 – Wilson Wetlands and areas within the Canning River Regional Park and adjacent land owned by Christian Brothers, managed by a collaborative arrangement and partnership between the Wilson Wetlands Action Group (WWAG), the Department of Parks and Wildlife (DPaW) and the City of Canning; (Priority: Medium);

Management Zone 2a – Canning River Main Channel from Kent Street Weir to Nicholson Bridge and the river bank areas in the Canning River Regional Park; managed by the Swan River Trust (now part of DPaW) (Priority: Highest);

Management Zone 2b - Three Wetland areas, which are integral parts of the southern side of the Canning River are proposed as a new Management Zone; Hydrocotyle infestation levels are considerably lower than in Wilson Wetlands; (Priority: Medium);

Management Zone 3 – Water Corporation Infrastructure – Welshpool Basin and Mill Street Drain (Priority: Highest);

Management Zone 4 – Bannister Creek; managed by City of Canning (Priority: Highest);

Management Zone 5 - Collier Pines Drain at Bodkin Park, Waterford. Managed by City of South Perth and Water Corporation (Priority -Highest - almost eradicated)

All areas where control action taken thus far has been successful receive the highest priority ranking, so that eradication of Hydrocotyle from these sites can be attempted. The time-frame for this is suggested to be the next 12-24 months.

The Wilson Wetlands (Zone 1) and the Lagoons on the southern side (Zone 2b) have some difficult-to-access infestations, which require different combinations of approaches, significantly more effort, time and resources for management, and careful consideration of safety for the staff involved. As a consequence, a Medium priority ranking is justified with a longer time-frame (3 to 5 years) for Hydrocotyle management within these wetlands.

The Management Plan envisages modifications depending on the actual results of tried control methods which do not achieve expected results. However, it should be regarded as a tool to achieve better outcomes, over a given period of time.

Goals of the Hydrocotyle WMP are set as follows:

Goal 1: A collaborative framework is in place that enables stakeholders to work together in an integrated manner to manage Hydrocotyle infestations and new outbreaks in the Canning River and adjacent waterways and wetlands.

Goal 2: An overall reduction in the extent and intensity of infestations is achieved and eradication from some locations.

Goal 3: Further spread of the weed beyond current boundaries is effectively prevented.

Goal 4: All stakeholders are involved in cooperative effort against Hydrocotyle incursions; including the implementation of effective education and awareness programs.

Goal 5: New technologies and management options advised through research and development are supported and promoted in the management of Hydrocotyle in the region

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | vii

Specific actions, performance indicators and responsibilities for each Management Zone and the above Goals of the Hydrocotyle WMP are provided in the plan. It is recommended that the Hydrocotyle Working Group lead the implementation of the plan.

Monitoring and Review of Hydrocotyle WMP

Monitoring and reporting should be an integral part of implementing the Hydrocotyle WMP and should include:

(a) Annual reporting on implementation, particularly with regard to Federal funding;

(b) Report to be compiled by the relevant lead implementing agency and submitted to the Hydrocotyle Working Group and to all stakeholders, with reporting on achievement of each action;

(c) Annual survey of Hydrocotyle populations recorded on a central database and report of comparison with previous years made; and

(d) Review of the Hydrocotyle WMP in 2018 (after 3 years) and changes to be collaboratively developed through the Hydrocotyle Working Group and other stakeholder inputs.

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | viii

Table of Contents 1. Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1

1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objectives of the Plan .......................................................................................................... 1

1.3 The Problem ........................................................................................................................ 2

2. Information Review ........................................................................................................................ 6

2.1 Hydrocotyle Growth attributes and reproductive strategy.................................................... 6

2.2 Management experiences - Overseas ................................................................................. 8 2.3 A Brief History of Hydrocotyle management in the Canning River and

associated waterways .......................................................................................................... 9

2.4 Recent Management Effort ................................................................................................ 11

2.5 Levels of Current infestations ............................................................................................ 15

3. Key Issues .................................................................................................................................... 18 3.1 An adaptive management approach .................................................................................. 18

3.2 Negative Impacts of Hydrocotyle ....................................................................................... 19

3.3 Beneficial Uses of Hydrocotyle .......................................................................................... 19

3.4 Stakeholder and Community Engagement ........................................................................ 19

3.5 Management Principles and Strategic approach ............................................................... 21 3.6 Other key Issues ................................................................................................................ 21

4. Hydrocotyle Management Options ............................................................................................... 27

4.1 Strategic Weed Management ............................................................................................ 27

4.2 Integrated Weed Management (IWM) ............................................................................... 27

4.3 Factors affecting choice of control methods ...................................................................... 28 4.4 Non-Chemical Control Methods ......................................................................................... 29

4.5 Chemical Control – Herbicides .......................................................................................... 37

4.6 Integrated Control .............................................................................................................. 39

5. Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan ......................................................................................... 41

5.1 Justification for Management Plan ..................................................................................... 41 5.2 Overall Aim of WMP ........................................................................................................... 41

5.3 Objectives of the WMP ...................................................................................................... 42

5.4 Legislative Control and Prevention .................................................................................... 42

5.5 Stakeholders ...................................................................................................................... 43

5.6 Mapping of Infestations ...................................................................................................... 44

5.7 ‘Site-Specific Management and Management Zones ........................................................ 46 5.8 Specific Management actions ............................................................................................ 46

5.9 Considerations and Opportunities ..................................................................................... 56

5.10 Management Goals, Actions and Responsibilities ............................................................ 56

5.11 Implementation Schedule .................................................................................................. 60

5.12 Training .............................................................................................................................. 60

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | ix

5.13 Monitoring and evaluation .................................................................................................. 60

5.14 Performance indicators ...................................................................................................... 61

5.15 Benefits .............................................................................................................................. 61 5.16 Lead Implementer – ‘Hydrocotyle Working Group’ ............................................................ 61

5.17 Stakeholder Roles and responsibilities .............................................................................. 62

5.18 Re-evaluation of the Hydrocotyle Management Plan ........................................................ 63

6. References ................................................................................................................................... 64

List of Tables Table 1 Herbicide treatments at Mill Street Drain and Bodkin Park ............................................... 12

Table 2 Triple Bottom Line Impacts of Hydrocotyle*....................................................................... 20

Table 3 Scoring System for assessing spread and impact ............................................................. 24

Table 4 Herbicides recommended for controlling Hydrocotyle ranunculoides* .............................. 37

Table 5 Declared Plant Classes in WA and Actions required by Law ............................................ 42

Table 6 Management Units - Prioritisation for Control with rationale* ............................................ 47

Table 7 Specific Management Actions recommended for Management Units ............................... 51

Table 8 Management Goals, Action and Responsibilities for the Hydrocotyle WMP ..................... 57

Table 9 Summary of Stakeholder Roles and Responsibilities ........................................................ 62

Table 10 Key Issues and Strategies ................................................................................................. 69

Table 11 Summary of Discussions with Stakeholders ...................................................................... 70

Table 12 Summary of Discussions with Stakeholders at Workshops ............................................... 71

Table 13 Some monitoring data from Wilson Wetlands Water Quality Monitoring ........................... 84

List of Figures Figure 1 Canning River regions – Main River Channel, Wetlands and Lagoons .............................. 5

Figure 2 Life cycle of Hydrocotyle ranunculoides (Source: Hussner and Lösch 2007) ..................... 7

Figure 3 Known infestations of Hydrocotyle in 2007 (from mapping conducted by SERCUL) ........................................................................................................................... 16

Figure 4 Known infestations of Hydrocotyle mapped by SERCUL in May 2015 ............................. 17

Figure 5 Schematic diagram showing the adaptive management approach that underpins the Hydrocotyle Management Plan .................................................................................... 18

Figure 6 Extent of Hydrocotyle infestations in the Canning River Region, Lagoons, Wetlands and Tributaries (July 2015) ................................................................................ 45

Figure 7 A Map of Wilson Wetlands showing the main waterbodies (Wilson 1 –freshwater; Wilson 2 and Wilson 3 both saline), drainage channels and locations of WWAG’s Water Quality monitoring points ...................................................... 78

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | x

Figure 8 An aerial image showing Hydrocotyle infestations on the lower section of Wilson 2 Wetlands ......................................................................................................................... 79

List of Plates Plate 1 Hydrocotyle- leaves with lobes, succulent stalks ................................................................. 2

Plate 2 Dense infestations growing on shallow water ...................................................................... 2

Plate 3 Hydrocotyle- umbel and flowers .......................................................................................... 4

Plate 4 Aquatic habit - growing on shallow water ............................................................................ 4

Plate 5 A view of dense Hydrocotyle infestations in Wilson Wetlands ............................................ 4

Plate 6 An infestation in a canal in UK –removed by mechanical equipment (Source: Newman, 2006) .................................................................................................................. 31

Plate 7 Amphibious crafts ‘Truxor’ used for mechanical removal of aquatic plants (Source: Australian Catchment Management Website, 2015) .......................................... 32

Plate 8 A close up view of Centella asiatica in upper riparian areas ............................................. 34

Plate 9 Extensive Centella stands in Canning River Regional Park .............................................. 34

Plate 10 Weevil – Listronotus elongatus feeding damage on Hydrocotyle ...................................... 36

Plate 11 Hydrocotyle growing out of Typha infestations (14/2/2012) at Wilson Wetland 2 ............. 81

Plate 12 Hydrocotyle infestations in Wilson Wetland 2 (14 Feb 2015) ............................................ 81

Plate 13 Hydrocotyle removal by hand by WWAG volunteers at Wilson Wetland 2 (16 April 2015) .......................................................................................................................... 82

Appendices Appendix A – Summary of the Outcomes of Consultation with Stakeholders

Appendix B – A Summary of Key Issues raised in Stakeholder Discussions

Appendix C - Overview of A Weed Management Plan

Appendix D – An Update on Hydrocotyle Management at Wilson Wetlands

Appendix E – Minimising Potential Impacts of Herbicide Use

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | xi

Acknowledgements The following people and organisations took part in the consultation process and in the Workshops, and assisted in developing the Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan (WMP). Their assistance is gratefully acknowledged.

Name Agency / Group

Kelly Fulker; Greer Gilroy; Luke McMillan Perth NRM

Brett Kuhlmann and Matt Grimbly SERCUL

Debbie Besch - Healthy Rivers Coordinator Department of Parks & Wildlife (formerly Swan River Trust)

John Snowden - Riverpark Operations Officer Department of Parks & Wildlife (formerly Swan River Trust)

Jenni Andrews (Coordinator Conservation and Environment) and Matthew Box (Operations Officer)

City of Canning

Julie Ophel - Environmental Officer City of South Perth

Michael Cobby - Operations Officer Department of Parks & Wildlife (DPaW)

Russel Gorton, Chairman, WWAG Wilson Wetlands Action Group (WWAG)

Jo Stone and Richard Stone Canning River Regional Park Volunteers

Stuart Martin; Vid Talevski; Martin Gehrmann Martins Environmental Services

Nathan Pearce - Director and Operations Manager Bunyip Contracting

Andrew Reeves, Development Officer Department of Agriculture and Food, WA

Karen Warner Eastern Metropolitan Regional Council

The preparation of the Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan was funded by the Australian Government’s National Landcare Programme.

Abbreviations SERCUL South East Regional Centre for Urban Landcare

DPaW Department of Parks & Wildlife (formerly Swan River Trust)

WWAG Wilson Wetlands Action Group

DAFWA Department of Agriculture & Food, WA

Hydrocotyle WMP Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan

SCRR Swan Canning River Recovery Programme

POEA Polyethoxylated tallow amine

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 1

1. Introduction 1.1 Background

In January 2015, the Federal Environment Minister Greg Hunt announced the Swan Canning River Recovery (SCRR) Programme, a $1 million commitment to improve the health of the Swan and Canning Rivers funded through the Australian Government’s National Landcare Programme. The programme aims to eradicate the Hydrocotyle weed, provide support for practical, community environmental action and help people understand how their actions affect the river.

Perth NRM, a peak natural resource management body, are managing the investment over two years, working in partnership with the local environmental community to deliver the outcomes required of this funding.

The Programme outcomes are:

- Local decision making relating to the development and implementation of the project through key stakeholders via a local steering group.

- Weed control and management in the Middle Canning estuary with a focus on controlling the weed, Hydrocotyle.

- Greater community action in the recovery of the Swan-Canning River system within the Middle Swan estuary and Middle Canning estuary.

- Improved community awareness of the behavioural changes needed to reduce nutrient loads entering the Swan-Canning River system in the Middle Swan estuary and Middle Canning estuary.

One component of the Programme was to undertake the development of a Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan (hereafter, referred to as the Hydrocotyle WMP) for the middle and upper Canning River (Canning Bridge to Nicholson Bridge), in consultation with key stakeholders and the local steering group (Hydrocotyle Working Group).

The development of the Hydrocotyle WMP was to be guided by previous, evidence-based knowledge and local actions that have been taken over the past twenty five or so years, to contain, control and eradicate Hydrocotyle from the infested Canning River areas.

1.2 Objectives of the Plan

The primary objectives of the Hydrocotyle WMP are as follows:

Develop a strategic approach to managing Hydrocotyle in the middle and upper Canning River, based on community consultation and available evidence and history;

Develop an Implementation Plan, also in consultation with the local Landcare community, assigning priorities to undertaking weed management actions in infested areas;

Ensure the SCRR Priority Weed Management Program aligns with and complements the Hydrocotyle Management Plan and the SCRR Direct Community Action program.

Specific Objectives

Review the history of Hydrocotyle management studies and efforts in the area to identify gaps in knowledge, understand the factors that contributed to spread, and evaluate historical control methods;

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 2

Map the extent and distribution of Hydrocotyle within the management area, to inform the management zoning and prioritisation of actions;

Identify/assess a range of non-herbicide, site specific management options for successful long-term management of Hydrocotyle in the area;

Determine the environmental risks associated with each management option; identifying preferred locations, and specific actions;

Provide recommendations on all options and the most appropriate combination of management options and approaches;

Develop implementation strategies to achieve potential eradication of Hydrocotyle from infested locations and responsible agencies and stakeholders; and

Establish a framework for long-term management of Hydrocotyle.

1.3 The Problem

Hydrocotyle ranunculoides, called the ‘Floating Pennywort’ (or Hydrocotyle), is a native of North America, but has become naturalised in Central and South America. In its native range, Hydrocotyle occurs in, and at the margins of, slow-flowing, warm and nutrient-rich water in Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay, also in southern states of the USA (Hussner et al., 2012 and references therein). Outside its native range, it is widespread in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Belgium, and present in France, Ireland, Italy, Germany, Australia, Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, Rwanda and Zimbabwe and possibly also in Sudan (Newman et al. 2009). Wherever it grows in introduced areas, it is considered to be a problematic invasive species,

In Europe, it is found in and around canals, lakes, rivers, streams, ditches, and garden ponds. Extensive infestations have been recorded in the Netherlands and in southern mainland Europe. According to Newman and Duenas (2010), Hydrocotyle was first brought to the United Kingdom in the 1980s by the aquatic nursery trade, for tropical aquaria and garden ponds, although the first note of concern over its potential to become a weed had been published in the UK, as far back as in 1936.

Hydrocotyle (Plate 1 and 2) was first observed in sections of the Canning River, mostly between the Nicholson Road Bridge and Kent Street Weir in 1983 and in the following years spread throughout the Canning River Regional Park (Webster, 1994), including adjoining creeks and in associated wetlands, such as Bannister Creek and Wilson Lagoon.

Plate 1 Hydrocotyle- leaves with lobes, succulent stalks

Plate 2 Dense infestations growing on shallow water

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 3

Records indicate that it was first observed in Bannister Creek, a tributary of the Canning River in 1983, and remained relatively static until 1991 when it suddenly spread (Swan River Trust, 1996). In February 1989, the infested area of river covered by Hydrocotyle, between the Kent Street Weir and Nicholson Road Bridge in the Canning River was estimated to be only 0.16% of the area, and the species was not considered a problem.

In 1991, Hydrocotyle suddenly expanded and by September 1992, its cover had increased to an alarming 29-30% of the open water area between the Kent Street Weir and Nicholson Road Bridge (Klemm et al., 1993). Infestations had extended throughout the drainage network into the river and adjacent wetlands, disrupting the ecology and recreational uses of the waterways, and posed a threat to other waterways (Ruiz-Avila and Klemm, 1996).

Hydrocotyle was recognised as an aquatic species that has the potential to develop into a serious environmental, economic and recreational threat to other lakes and waterways. The mass of plant material in the Canning River posed a potential risk of spread within the State, and also throughout Australia (Webster, 1994).

The distribution of Hydrocotyle is restricted to freshwater habitats, where the plant makes rapid growth during the warm months of the year and forms dense floating mats which can cover the waterway from bank to bank. If unmanaged, Hydrocotyle can restrict movement of recreational boating, alter ecosystems and spread to other lakes and waterways. Hydrocotyle stems are mostly creeping (i.e. rhizomatous stems and stolons) and produce profuse, hair-like adventitious roots from the nodes, which usually occur at intervals of approximately 4-6 cm (Newman and Dawson, 1998). The stems and leaf stalks are hairless and somewhat fleshy in nature with aerenchyma, which aid in floatation.

Hydrocotyle leaves are mostly emergent, rising on stalks from the horizontally-growing stems. The leaves are alternately arranged along the stems and are also hairless. The leaves (Plate 1) are typically 2.5-4 cm across, but can often be large (4–12 cm across) and can attain a maximum diameter of about 18 cm. They are almost round in shape with a deep split, or are occasionally kidney-shaped with shallow or deep lobes and bluntly toothed margins. Leaves and stems may stand out of water about 40 cm above the water surface in large infestations, while the interwoven mat of roots can sink down to a depth of about 50 cm (Newman and Dawson, 1998).

Hydrocotyle flowers are arranged in clusters (i.e. compound umbels), arising from the leaf axils and are often hidden underneath the leaves (Plate 3; Plate 4). These flower clusters consist of a stalk (peduncle) which has several 1-5 cm long branches, each bearing a smaller cluster (an umbel) of 5-10 flowers. The tiny flowers are white, greenish or yellowish in colour with five minute petals and no obvious sepals. Flowering occurs mostly during spring and summer.

The fruit (mericarp) is oval-elliptic to round in shape, green in colour, 1-3 mm long, flattened, and has faint ribs. It divides into two halves when mature. Mature seeds are light to dark brown in colour; about 3 mm long and there are two seeds set in each fruit/flower.

Whilst the reproduction by seeds is well established for Hydrocotyle, its primary growth strategy is vegetative reproduction via stolons and stem fragments. Seed reproduction adds to the persistence and capacity of the species to disperse and spread (Webster, 1994). The management implication is that even if the vegetative biomass is controlled and removed, seeds could remain viable in slushy mud. Therefore, timely management action is needed to reduce the sexually mature vegetative growth leading to the production of flowers, fruits and seeds.

Given favourable conditions, Hydrocotyle is capable of forming extensive mats from the smallest root or stem fragments. Longer distance dispersal of stem fragments usually occurs by water movement and floods or as a result of human activities (e.g. dumped aquarium waste).

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 4

Plate 3 Hydrocotyle- umbel and

flowers Plate 4 Aquatic habit - growing on

shallow water

The current distribution of Hydrocotyle in the Canning River region has been mapped, based on the work of community groups and agencies involved in its management. A program of regular inspections by a number of agencies and community groups has provided accurate information on the current distribution, extent and abundance in the management area.

Hydrocotyle infestations in open water areas, in drains, and in slushy mud in wetlands and lagoons are currently managed in the Canning River region using a number of methods. These include manual removal of small populations in soft mud and the use of herbicides - Glyphosate and Metsulfuron-methyl. Whilst these methods have had varying success, this WMP takes into consideration all options, including environmentally-sound, non-herbicide options, as well as site specific approaches and techniques that may be applicable to specific, environmentally-sensitive sites, such as the Wilson Wetlands (Plate 5).

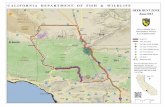

The Wilson Wetlands are a brackish water lagoon system, which has well-established conservation values. Three lagoons (Wetlands 1, 2 and 3) have been recognised (Figure 1).

Over several decades, the Lagoons have undergone major changes in their hydrology (from brackish to freshwater); as a result of local landuse changes, upstream developments, and freshwater inflows from major, urban stormwater drains.

Plate 5 A view of dense Hydrocotyle infestations in Wilson Wetlands

There has been at least two decades of Hydrocotyle research and management effort documented from the Canning River region (Ruiz-Avila and Klemm, 1996; Swan River Trust, 1996). Given this previous history, and the high degree of interest by the local community in managing Hydrocotyle in the Canning River region, the Hydrocotyle WMP needs to achieve a high level of consensus amongst stakeholders in terms of the way forward.

The Hydrocotyle-infested Canning River area – the main channel between Kent Street Weir and Nicholson Road Bridge and associated wetlands and lagoons are depicted in Figure 1

Kent Street Weir

Albany Highway

Leach Highway

Nicholson Road

Marmot 2

Marmot 1

Marmot 3

Wilson 2Wilson 1

Wilson 3

Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Earthstar Geographics, CNES/Airbus DS, USDA, USGS, AEX,Getmapping, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, swisstopo, and the GIS User Community, Esri, HERE, DeLorme, MapmyIndia,© OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS user community

397,000

397,000

398,000

398,000

399,000

399,000

400,000

400,000

401,000

401,000

6,456,

000

6,456,

000

6,457,

000

6,457,

000

Figure 1

Job NumberRevision A

23-15602

G:\23\15602\GIS\Maps\Working\2315602_Z008_WetlandsOverview_A4.mxd

Map Projection: Transverse MercatorHorizontal Datum: GDA 1994Grid: GDA 1994 MGA Zone 50

0 110 220 330 44055

Metres

LEGEND

o© 2015. Whilst every care has been taken to prepare this map, GHD (and ESRI) make no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and cannot accept liability and responsibility of any kind (whether in contract, tort or otherwise) for any expenses, losses, damages and/or costs (including indirect or consequential damage) which are or may be incurred by any party as a result of the map being inaccurate, incomplete or unsuitable in any way and for any reason.

Date 02 Sep 2015

Perth Region NRMHydrocotyle Management Plan

Canning River Regional ParkWetlands and Lagoons

Data source: GHD, Hydrocotyle/HydrocotyleCover, 7/8/2015; ESRI, World Imagery/http://services.arcgisonline.com/ArcGIS/rest/services/World_Imagery/MapServer accessed 7/8/2015 Created by:atdickson

20 Smith Street Parramatta NSW 2150 Australia T 61 2 8898 8800 F 61 2 8898 8810 E [email protected] W www.ghd.com

Paper Size A4

DRAFT

Wilson WetlandsMarmot Way Wetlands

Principal RoadMinor Road

Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe,GeoEye, EarthstarGeographics, CNES/AirbusDS, USDA, USGS, AEX,

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 6

2. Information Review Effective control strategies for aquatic plants are usually based on a sound knowledge of their biology, ecology and factors that influence the plants’ spread and colonization. Accordingly, the Hydrocotyle WMP needs to take into consideration the key factors, which influence the Hydrocotyle infestations in the region, based on both local research and management experiences, as well as overseas experiences in similar habitat and situations.

These views were endorsed by the Stakeholders during the consultation process and workshops (see Appendix A and Appendix B).

This Section provides an overview of the ecology of Hydrocotyle and management experiences, gleaned from available historical information in the Canning River region, WA and from overseas. Information was obtained from: (a) A review of all available historical reports relevant to Hydrocotyle management and related issues in WA; (b) Consultation with major stakeholders, in face-to-face interviews and phone interviews with individuals and groups; and (c) A global literature search, covering journals and publications.

There is extensive information and documented experiences of Hydrocotyle control from UK and other Western European countries (mainly, The Netherlands, Belgium and Germany), where the species has been of concern for about 20 years. A summary of some relevant information is provided in Appendix B.

The Information Review provides an increased understanding of ecology and biology of Hydrocotyle, as well as methods that have been found to be effective in other jurisdictions and situations. The information immediately relevant to this WMP are summarised below.

2.1 Hydrocotyle Growth attributes and reproductive strategy

In aquatic environments, Hydrocotyle forms floating mats as an emergent, stoloniferous, aquatic plant. However, in moist, lower and upper riparian vegetation, it behaves as a helophyte (perennial marsh plant that bears its overwintering buds in the mud below the surface; from the Greek words: helos – marsh; phyte - plant). The plant possesses a number of characteristics typical of strongly colonising (weedy) species. These include the following:

a. High growth rates, particularly when conditions are favourable (warm temperature; high sunlight; high nutrients);

b. Effective vegetative propagation (new plants arising from even small fragments);

c. Reproduction from seeds; at least 50% of seeds per fruit are viable with little dormancy;

d. Plasticity in growth responses (e.g. over-wintering, aquatic, as well as partly-terrestrial growth forms; increased growth in high nutrient environments);

e. Relatively easy spread by various agents (fragments are known to gain weight and produce roots while floating, and then rapidly grow in new environments); and

f. High resistance to herbivory (McChesney, 1994).

The growth season of Hydrocotyle is the warm months - spring and summer (June and July in the Northern Hemisphere; and October to February in the Southern Hemisphere) and growth typically starts in early spring from small plants or fragments when air and water temperatures rise (Klemm et al., 1993; Ruiz-Avila and Klemm, 1996; Newman and Dawson, 1998; Newman, 2006; Hussner and Lösch, 2007; Newman et al., 2009; Newman and Duenas, 2010).

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 7

The life-cycle can be schematically depicted as in Figure 2. Hydrocotyle grows slowly in spring and form small, up to 10 cm2 large leaves (Figure 2a), which mostly float on the water surface. With increasing temperatures, photoperiod and light intensity, leaves grow larger and petioles reach a height of up to 40 cm above water level (Figure 2b) (Webster, 1994; Newman, 2006; EPPO, 2006; CABI, 2015).

The stems root freely from nodes at about 4-15 cm intervals. With decreasing temperatures and light availability in autumn, smaller leaves develop and some of the leaves die due to night frost. At this time, Hydrocotyle will form floating and submerged leaves (Figure 2c). The latter are able to survive the low water temperatures during the winter (Hussner and Lösch, 2007). From these small submerged plants and leafless over-wintering stolons plants will grow out again in spring.

Figure 2 Life cycle of Hydrocotyle ranunculoides (Source: Hussner and Lösch 2007)

There is evidence from Western Europe that natural fragmentation tends to occur, releasing fragments in fast flowing environments, and in the winter; however, both fast flowing water and winter conditions are noted as less suitable for rapid regrowth and re-colonization.

From the information review, the following observations can be made of the biology, ecology and growth conditions of Hydrocotyle:

Many growth parameters, such as leaf area index (LAI), total dry weight, dry weight of leaves, petioles, shoots and roots, total shoot length, number of nodes, total number of leaves and the average leaf size) have been recorded to be much higher in habitat with high nutrient content of the soil, compared with stands in habitats with lower nutrient contents (EPPO, 2006; Hussner et al., 2012; CABI, 2015).

In one of the European studies, which included modelling Hydrocotyle growth, the model (CHARISMA) accurately predicted growth patterns and biomass accumulation in an unmanaged state. The model predictions matched the actual annual biomass production (maxima of approximately 1,200 g dry weight m-2).

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 8

The model also suggested that biomass maxima may occur on more than one occasion per year, resulting in peak releases of vegetative fragments on a more regular basis, especially if plant material is cut, releasing fragments at optimal times of the year for regrowth and colonisation (Hussner et al., 2012). However, the study has not been extended to model the effects of management actions.

In Australia, research indicates that Hydrocotyle doubles its biomass in 3 days (Ruiz-Avila and Klemm, 1996). In the UK, doubling times vary between 4 and 7 days in summer, depending on the availability of nitrate, and the plant also exhibits a seasonally variable growth rate with maximum growth in late summer when it typically forms extensive floating mats of vegetation (Newman, 2006). It over-winters in the margins and on banks of waterways, as a much flatter and smaller plant.

Webster (1994) determined seed viability in glasshouse conditions to be about 44% and average seed production (estimate) under favourable conditions to be approximately 8000 seeds/m2. Her studies indicated that only one seed per mericarp was viable, resulting in approximately 50% of seeds being viable.

Klemm et al. (1993) estimated the potential seed production in the field, based on biomass (per m2 of plant biomass) of Hydrocotyle, to be 9000 seeds/m2. Their estimate included immature fruits and seeds, some of which may have aborted. A separate study by Webster (1994), collecting mature Hydrocotyle seeds from mats in the field for 50 hours- yielded only 1600 seeds, which was suggested as a much lower figure than Klemm et al.’s (1993) estimate based on plant biomass.

Webster’s studies (1994) also showed that seed viability and seedling germination were both significantly higher at lower temperatures (15 0C), compared with higher temperatures (23 0C or 28 0C); this was possibly an adaptation of a species of temperate origin (Webster, 1994). Seeds did not germinate in the dark; nor did they grow in water. Seeds grew strongly in muddy substratum. These findings suggest that seeds caught in and under mats of Hydrocotyle would not germinate, but the removal of mats could stimulate new plants from seeds.

Salt affects the growth and survival of Hydrocotyle, as it is essentially a freshwater species. This suggests that salinity management could be a management tool in the Canning River. Preliminary studies in WA by Klemm et al. (1993) indicated the critical salinity levels to be in the range of 4% - 20% sea water. Webster’s studies (1994) indicated the critical range to be 10% to 20% of sea water, and severe impairment of Hydrocotyle growth levels below 10% sea water.

Salinity inhibited Hydrocotyle root growth, leaf production and stunted the vigour of clonal growth; however, the repressive effects of salt depended on the level of salt and duration of exposure. The research conducted in WA (Webster, 1994) indicated varying levels of salt tolerance by clonal fragments and rapid recovery of growth in freshwater. The management implication is that relatively short exposure of a few days to salt water up to 20% sea water is highly unlikely to be sufficient for Hydrocotyle control.

2.2 Management experiences - Overseas

In the UK and several other European countries, mechanical control is the main method of Hydrocotyle management, with cutting and removal of large floating mats. In the Dutch canal systems, mechanical cutting is commonly used, as part of regular maintenance, resulting in a much reduced final biomass.

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 9

In the UK, mechanical control has probably perpetuated the presence of the plant at several locations, primarily as a result of the timing of cutting and the release of vegetative fragments at optimum times for regeneration of fragments.

In overseas studies on the comparison between mechanical and chemical costs, herbicides are approximately 50% cheaper than mechanical control, and have also resulted in a better overall reduction in plant biomass in the following year.

Novel techniques, i.e. the use of hydrogen peroxide, flame throwers (heat), adjuvants and combined mechanical and chemical techniques have all been tested in greenhouses studies, and these show considerable promise (Newman et al., 2009).

The prospects for flame weeding have also been positive; as a result, this control option is being investigated in Belgium under practical conditions in the growth season for the optimal timing of application in relation to the growth stages of Hydrocotyle.

Trials using herbicides and adjuvants, in combination with mechanical control, have been on-going in the UK. Much of the research indicates that site requirements and conditions govern the choice of technique and optimisation of those techniques in particular situations requires up to date advice, based on experience.

As reported by Hussner et al. (2012; and references therein), in Flanders, Belgium, provincial and local authorities have collaborated with the Flemish Environment Agency in a monitoring and control program that addressed both water bodies in both public and privately-owned lands. The program aimed to eradicate Hydrocotyle, with the plan consisting of using contractors for mechanical removal, according to a strict protocol, avoiding techniques producing plant fragments, and manual harvesting of all plants remaining after three weeks. Chemical treatment is not allowed in the program. Manual intervention is continued until an infested site is cleared of Hydrocotyle. It has been noted that the efficiency of removal strongly depends on the quality of the work of contractors and good project management. On private properties, initial removal can be carried out at no expense to the proprietor if prospects for success and follow-up by the land owner are good. Results over the past few years appear to be promising.

2.3 A Brief History of Hydrocotyle management in the Canning River and associated waterways

The following is a synthesis of the history of Hydrocotyle infestations in the Canning River regions, gleaned from a review of available literature (Webster, 1994; Swan River Trust, 1996); Ruiz-Avila and Klemm, 1996) and information provided by stakeholders.

In late 1991, there was an estimated 175 tonnes of Hydrocotyle in the Canning River (biomass was calculated, based on aerial photography of the infestation areas and actual biomass determinations and area/weight relationships).

Early control attempts involved a two-week program of physical removal of Hydrocotyle by cutting the floating mats with sickles and scythes from small boats. The mats were then pushed by small boats to an aquatic macroalgal conveyor-harvester, floated to the bank and removed by a backhoe. Follow-up maintenance control was conducted until January 1992, when the growth rate exceeded the rate of removal.

Whilst the physical removal program of 1991 provided short-term relief, it resulted in fragmentation of plant material, which dispersed and regenerated in new habitat, causing Hydrocotyle to spread beyond the original infestation. New mats grew from these fragments over the following 12 months greatly increasing the infestation size.

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 10

By September 1992, the estimated biomass in the River was 420 tonnes, mostly in the freshwater sections of the River, above the Kent Street Weir. During the summer, the mats grew rapidly, covering the River from bank to bank. Downstream of the Kent Street Weir, the rise in salinity destroyed all of the mats. The experience and knowledge gained during these early attempts at control proved invaluable in the development of an integrated strategy for Hydrocotyle management in the Canning River regions (Ruiz-Avila and Klemm, 1996).

Stakeholder agencies and the local community were then involved in the complex technical, environmental, organizational, legislation-related, educational and social requirements of developing an integrated management strategy (Klemm et al., 1993). Extensive consultation was undertaken and was regarded as a vital component for ensuring community support for Hydrocotyle management. The aim of the strategy was to eradicate Hydrocotyle in the long-term, whilst minimizing adverse effects on water quality, river ecology, recreational amenities and public health. As part of the strategy, Hydrocotyle was declared a noxious weed in 1992 by the then WA Department of Agriculture.

The lack of biological and ecological information was identified as a key constraint to effectively managing the plant. This led to various research studies being supported and undertaken (see McChesney, 1994; Webster, 1994; 1995). A two part management strategy was developed, which consisted of a short-term control program, implemented in early 1993; and a long-term eradication program.

The short-term strategy relied largely on physical removal, similar to the methods used in 1991, and follow-up treatments with herbicide. About 2,000 tonnes of Hydrocotyle were removed in 1993, with plant matter then composted by the Local Councils. Biological control was not considered as an option; ecological techniques were either unsuitable or unavailable for use in the short-term program, but were recognised as suitable in the long-term strategy of eradication – if other methods failed (Ruiz-Avila and Klemm, 1996).

Round-up™ Glyphosate, a systemic (one that translocates in a plant) but non-selective herbicide, was the herbicide of choice in the early stages, based on the results of glasshouse trials, its low toxicity to mammals, fish and microbes, and low to medium toxicity towards birds and other aquatic life. Initially (1993), an application rate of 360 g/ha (i.e. 1 L of commercial product in 100 L of water per ha) was used. Later, in 1994, a stronger rate commercial product (450 g/ha) was used. Strong community concerns were raised at this time about the overuse of herbicides and potential adverse impacts of other techniques on the riverine ecosystems.

Despite providing a high degree of short-term control, regrowth of Hydrocotyle still occurred after a single round of Round-up™ Glyphosate treatments. This suggested that one round of treatments was not sufficient to eradicate Hydrocotyle. Regrowth was attributed to some material surviving the treatments, establishment from new seedlings and re-introduction of Hydrocotyle from other areas to the treated areas. Subsequent research and monitoring of Bannister Creek treatments by Webster (1994) confirmed that a single round of Glyphosate treatments was inadequate for Hydrocotyle control.

The long-term program included investigating the opportunities for reduction of nutrient loads into the River from the upper catchment and the removal of nutrient-rich sediments from sections of the River. Major waterway health programs commenced in the upper catchments around this time with the aim of reducing nutrient loads in the drainage network.

Nutrient enrichment of the waterways was regarded as a cause of Hydrocotyle’s expansion, and reduction of nutrients would reduce the opportunity for invasion by Hydrocotyle, as well as other aquatic species (Ruiz-Avila and Klemm, 1996).

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 11

Responding to public concerns, an ecological investigation was also undertaken to identify whether or not there are environmental impacts of management action on the riverine fauna and their habitat, and to measure such effects. Macro-benthic fauna were measured throughout the management program and areas where control was being implemented with multiple herbicide treatments. The findings (Donahue, 1994) indicated no adverse effects either on water quality, or the communities of benthic organisms, which inhabited the river.

Subsequently, other herbicides were also investigated for use in combination with physical control, and the initial trials involved five herbicides: Chlorsulfuron; Metsulfuron-methyl; Glyphosate, Simazine and Imazethapyr (Klemm et al., 1993).

Previous studies had shown that Hydrocotyle is quite sensitive to salinity levels. Based on this information, an option considered in the long-term strategy was the possibility of manipulation of salinity in the freshwater sections of the Canning River by the removal of the weir boards.

Reporting on the Hydrocotyle management efforts in the Canning River and surrounding areas, Ruiz-Avila and Klemm (1996) concluded that the integrated strategy was successful in controlling the Hydrocotyle invasion with no long lasting environmental impacts.

The lessons learnt were the need for: (1) Broader community/stakeholder consultation; (2) Integration of all appropriate methods; (3) Control of the cause of the weed’s proliferation (i.e. eutrophication); (4) A commitment to long-term involvement to eradicate the weed; (5) Intervention at an early stage, when the weed populations are still small (i.e. 1983); and (6) Understanding the risks of selling and dumping of non-native aquatic plants.

The historical accounts indicated hope that additional biological and ecological knowledge (determining life-history attributes; population dynamics and habitat requirements) of Hydrocotyle would aid in the efficacy of long-term eradication, which may be achieved in the next 5 years. However, the growth of Hydrocotyle in terrestrial environments, noted during that period was also another setback. It was also suggested that the Canning River system requires a long-term rehabilitation program to prevent future problems of aquatic weeds, posed by Hydrocotyle and others (Ruiz-Avila and Klemm, 1996).

2.4 Recent Management Effort

2.4.1 Hydrocotyle Working Group (since 2002)

Several agencies and stakeholders formed a partnership in 2002 in response to the need for co-ordinated control and management of Hydrocotyle across the Canning River regions, tributary creeks, lagoons, wetlands and the associated drainage network.

The group included representatives from the City of Canning, Water Corporation, former Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC, now Department of Parks and Wildlife, DPaW), Swan River Trust (also, now part of Department of Parks and Wildlife, DPaW), Department of Agriculture (now DAFWA) and the local community of volunteers and catchment groups, including SERCUL (Brett Kuhlmann, Matt Grimbly, SERCUL, July 2015, personal communications).

The formation of the group is regarded as an important mechanism for co-ordinated action, discussions of management issues and resolving areas where there have been differences of opinion, due to jurisdictional issues, as well as on-ground implementation of control. Lack of continuous funding for Hydrocotyle management has been a major constraint that the Working Group has had to manage.

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 12

During a period of several years, the program was not well funded, and inadequate control led to the re-establishment of Hydrocotyle in many areas that had been previously kept free of the weed by early management efforts. The weed also spread to new locations during this period.

2.4.2 South East Regional Centre for Urban Landcare (SERCUL)

Since 2013, SERCUL has been involved in controlling Hydrocotyle in Mills St Main Drain for the Water Corporation and Collier Pines Drain (Bodkin Park) for the City of South Perth and Water Corporation. The methodology involved initial treatment of the entire infestation to reduce the biomass using a mixture of Round-up Biactive® at 1% and Metsulfuron- methyl at the standard rate of 10 g per 100 L of water.

Herbicide applications were assisted by the vegetable oil additive ‘Endorse’ at 200 mL/100 L. This initial spraying was repeated until the Hydrocotyle reached a level where hand removal became possible. Hydrocotyle colonies less 0.1 m² were easily hand removed; larger patches were subject to repeat herbicide treatments (Table 1).

Table 1 Herbicide treatments at Mill Street Drain and Bodkin Park

Date Volume used

Chemical Area of treatment

22/03/2012 750 L Round-up Biactive (1%) + Metsulfuron-methyl (10 g/100 L)

Whole area of original infestation

28/03/2012 450 Round-up Biactive (1%) + Metsulfuron-methyl (10 g/100 L)

Whole area of original infestation

24/04/2012 450 Round-up Biactive (1%) + Metsulfuron-methyl (10 g/100 L)

Whole area of original infestation

2/07/2012 100 Round-up Biactive (1%) + Metsulfuron-methyl (10 g/100 L)

Spot treatments

5/10/2012 100 Round-up Biactive (1%) + Metsulfuron-methyl (10 g/100 L)

Spot treatments

15/11/2012 100 Round-up Biactive (1%) + Metsulfuron-methyl (10 g/100 L)

Spot treatments

8/01/2013 650 Round-up Biactive (1%) + Metsulfuron-methyl (10 g/100 L)

Whole area of original infestation

7/03/2013 600 Round-up Biactive (1%) + Metsulfuron-methyl (10 g/100 L)

Whole area of original infestation

29/10/2013 450 Round-up Biactive (1%) + Metsulfuron-methyl (10 g/100 L)

Whole area of original infestation

17/01/2014 50 Round-up Biactive (1%) Spot treatments

11/03/2014 220 Round-up Biactive (1%) Whole area of original infestation

8/04/2014 100 Round-up Biactive (1%) Spot treatments

17/10/2014 100 Round-up Biactive (1%) 1st basin

19/11/2014 400 Round-up Biactive (1%) Whole area of original infestation

3/03/2015 400 Round-up Biactive (1%) Whole area of original infestation

In conducting treatments for Hydrocotyle, control of other exotic vegetation in the Mills Street Drain was also targeted - to prevent Hydrocotyle becoming obscured. According to the monitoring and mapping conducted by SERCUL, the success of the program is evident; no Hydrocotyle has been recorded at either site, since November 2014.

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 13

2.4.3 Swan River Trust (SRT) and Department of Parks & Wildlife (DPaW)

The Swan River Trust merged with the WA State Department of Parks & Wildlife (DPaW) from 1 July 2015. At the time of writing this plan, Hydrocotyle, along the Canning River shorelines and riparian zone up to 2 m from the water’s edge was being managed by the DPaW’s Riverpark Unit (John Snowden, July 2015, personal communications).

The department’s Hydrocotyle control program involves regular monitoring by vehicle and vessel of the area from Kent Street Weir to Nicholson Road Bridge. When Hydrocotyle infestations or small colonies are spotted, a contractor is engaged to treat the Hydrocotyle. For the past two years, spot treatments have been conducted using Metsulfuron-methyl at a quarter-dose (i.e. 2.5 g/100 L of water), combined successfully with hand removal of small colonies.

Given below is a brief summary of the Hydrocotyle control program over the last 12 months, which demonstrates the effectiveness of the program:

12/03/2014 Spraying of Hydrocotyle. Swan River Trust areas on the Canning River. Chemical used Metsulfuron-methyl @ 2.5 g/100 L; 2.5 hrs of labour and 15 L used.

26/09/2014 - Spraying of Hydrocotyle. Swan River Trust areas on the Canning River. Chemical used Metsulfuron Methyl @ 2.5 g/100 L. 1 hr of labour and 10 L used.

20/01/2015 inspection by vehicle. Colahan Way Billabong, Camsel Way and Marmot Way. A number of suspect plants noted at Colahan Way and Marmot Way.

26/02/2015 - inspection by vessel. Kent Street Weir to Masons Landing. Small patch 0.5 x 0.5 m removed by hand from an area opposite Richmond St.

6/03/2015 - inspection by vehicle. Colahan Way Billabong, Camsel Way, Marmot Way, Bergall Circuit and Leige Street Wetlands drain.

17/04/2015 - inspection by vessel Kent Street Weir to Masons Landing.

20/04/2015 hand removal - Patch of 2 m2 removed from downstream from Bacon Street boat ramp; 6 m2 patch also on the north side of the river, just past Mason Street;

21/04/2015 - Spraying of Hydrocotyle in Canning River Regional Park area Marmot Way; 10 hrs of labour and 200 L used.; Swan River Trust areas on the Canning River downstream of Masons Landing (Metsulfuron Methyl @ 2.5 g/100 L; 50 L).

14/06/2015 - inspection by foot Masons Landing to Mason Street, north side of the Canning River. Good results noted for areas treated on 21/04/2015.

19/05/2015 - inspection by foot from Nicholson Road Bridge to Masons Landing - No Hydrocotyle recorded.

2.4.4 Wilson Wetlands and Wilson Wetlands Action Group (WWAG)

The Wilson Wetlands Action Group (WWAG), which formed in 1998, has been very active in restoring the Wilson Wetlands’ (brackish water lagoons) environment on the northern side of the Canning River and maintaining healthy wetland systems, which have undergone major changes over decades, as a result of upstream developments.

The Wilson Wetlands and Lagoons are part of the Canning River Regional Park. Hydrocotyle infestations of the Wetlands have been managed by WWAG, which is committed to restoring the wetlands' vegetation through natural processes (WAGG, 2015a). Parts of the Regional Park land WWAG volunteers work on are privately owned by the Trustees of the Christian Brothers (Castledare), who have been supportive of the Group’s commitments and efforts.

GHD | Report for Hydrocotyle Weed Management Plan - For the Middle and Upper Canning River, 23/15602 | 14

As a member of the Hydrocotyle Working Group, WWAG maintains strong working relationships with stakeholders, such as Department of Parks and Wildlife (DPaW), Swan River Trust, as well as with neighbouring community groups (such as Canning River Volunteers and SERCUL), local schools and individuals.

Hydrocotyle infestations within the Wilson Wetlands and Lagoon system are patchy. Most are rooted mats of about 1-3 m2 in extent with loosely floating stolons over water. However, there are also some patches which are quite extensive and greater than 5 m2 of dense mats, deeply-entrenched in slushy mud and in some cases, aggressively spreading across the surface of the lagoons, growing out from beneath the tree-scapes of the Melaleuca rhaphiophylla.

The boggy nature of the Wetland system prevents ready access in some areas, which has resulted in Hydrocotyle infestations becoming entrenched (WWAG (2015a; b). The Group recognises that without active management, Hydrocotyle poses a major threat to the conservation values of the Wetlands, which include habitat loss, due to encroachment and displacement of native species. WWAG is also concerned about poor water quality that may result from decaying vegetation and re-release of nutrients; and potential non-target impacts (i.e. off target damage to native sedges and native flora) that may result from management action, such as excessive herbicide use.

WWAG’s hypothesis is that the growth of Hydrocotyle in the Wilson Wetlands is correlated with the effects of ebb and flow of tidal movements, along with impacts from ground water saline seepages and freshwater inflows through the discharges received from upstream. Given that Hydrocotyle is inhibited by increased salinity, and controlled completely by high levels of salinity, the Group’s efforts are aimed at understanding how these factors can be manipulated to manage Hydrocotyle in the future, using non-chemical methods as tools.