Hyde Park History · 2018. 4. 2. · It was decorated with a silk banner embroidered with ravens....

Transcript of Hyde Park History · 2018. 4. 2. · It was decorated with a silk banner embroidered with ravens....

This Newsletter is published by

the Hyde Park Historical Society, a

not-for-profit organization founded

in 1975 to record, preserve, and

promote public interest in the history

of Hyde Park. Its headquarters,

located in an 1893 restored cable car

station at 5529 S. Lake Park Avenue,

houses local exhibits. It is open to

the public on Saturdays and Sundays

from 2 until 4pm.

Web site: hydeparkhistory.org

Telephone: HY3-1893

President: Michal Safar

Vice-President: Janice A. Knox

Secretary: Gary Ossewaarde

Treasurer: Jay Wilcoxen

Editor: Frances S. Vandervoort

Membership Coordinator:

Claude Weil

Designer: Nickie Sage

VOL. 39 N0. 3 SUMMER 2017Published by the Hyde Park Historical Society

Hyde Park HistoryNon-Profit Org.

U.S. PostagePAID

Chicago, IL Permit No. 85

HP HS

Hyde Park Historical Society 5529 S. Lake Park Avenue Chicago, IL 60637

SUMMER 2017

A bout and hour’s drive west of Chicago, in a private park, sits a 110-year-old wooden ship that once made headlines around the world. The flimsy tarp that protected it from the

elements has been blown aside by strong winds, and rain now freely bounces against the exposed wood. It is only a matter of time until the ship is damaged beyond repair. But in its current location few people will even note its disappearance: many believe it is gone already.

It wasn’t always this way.

The story of the ship is a long one that goes back to 1880, to Gokstad, Norway, and the discovery of a Viking war vessel unearthed form a burial mound. The Gokstad, as it was called, was built around 890 A.D. and was in remarkable shape. It provided the first tangible evidence that the Vikings had built ships capable of traveling to the New World.

But the proof would have to wait for a Norwegian named Magnus Andersen who decided that a replica of a Viking ship should be sailed across the Atlantic, as a counterpoint to the World Exhibition that would be held in America in 1893 to honor Columbus. He later recalled, “As I thought this over more closely, I found the idea more and more attractive. That Leif Erickson had been in America before Columbus clearly proved but was not commonly known either in America or elsewhere, not even Norway...”

The replica of the Gokstad was funded by popular subscription and completed in time for the Exposition. It was decorated with a silk banner embroidered with ravens. The ship itself was christened “The Raven,” but American popular press quickly named it “The Viking.” Magnus Andersen was the Captain.

The Viking sailed from Bergen, Norway, and reached Newfoundland four weeks later. The crew, uncertain how the ship would handle on the open seas, found it exceeded all expectations. “We noted

with admiration the ship’s graceful movements,” Andersen later wrote.

From Newfoundland, Viking headed south to New York, then sailed into the Great Lakes. Carter Harrison, Chicago’s four-term mayor, boarded and took command for the last leg of the voyage, arriving at Jackson Park on Wednesday, July 12, 1893, to much fanfare. Magnus Andersen had turned his dreams into reality. ➤ 2

Hyde Park Historical Society COLLECTING AND PRESERVING HYDE PARK’S HISTORY

Time for you to join up or renew? Fill out the form below and return it to:

The Hyde Park Historical Society 5529 S. Lake Park Avenue • Chicago, IL 60637

Enclosed is my new renewal membership in the Hyde Park Historical Society.

Name

Address

Zip Email

Phone Cell

Student $15 Individual $30 Family $40

✁

The Viking of Hyde Park

r

The Viking moored at Jackson Park for the remainder of the Fair. Afterwards, the Captain piloted it through the Illinois and Michigan Canal to the Mississippi River, all the way to New Orleans — the only seafaring vessel ever to do so.

The ship was brought back to Chicago and stored in the Field Columbian Museum until 1919, when it was restored and placed in Lincoln Park. In 1933, Magnus Andersen repeated his historic voyage in a modern freighter to appear at Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition.

The ship sat in Lincoln Park right up to the 1970s. Covered by a roof and enclosed by a chain-link fence, it sat outside in the blistering heat of summer and the freeing cold of winter until the wood seemed more akin to steel that anything else. Time had taken its toll on the Viking.

The Chicago Park District, without the funds to do a proper restoration, sold the ship for $1.00 to the American Scandinavian Council, which promised to raise the necessary funds, estimated at $12 million, to restore the historic vessel.

It seemed like a good idea at the time. But the funds were never successfully raised, and no preservation or restoration has been done. Unfortunately, the ship was also moved out of Lincoln Park and has been out of the public eye for nearly thirty years. Now it

Answer to Mystery Quiz:

Czech composer Antonin Dvorak, whose most famous work was his Symphony No. 9, From the New World. Dvorak had spent several months in the small Czech community of Spillville, Iowa while working on the New World Symphony, but at the invitation of Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s conductor, Theodore Thomas, had agreed to conduct his Symphony No. 8 at the Music Court near the west lagoon of Jackson Park.

➤ 1

S u m m e r 2 0 1 7r

7

r

S u m m e r 2 0 1 7r

PH

OTO

/ T

HE

DIG

ITA

L R

ES

EA

RC

H L

IBR

AR

Y O

F IL

LIN

OIS

HIS

TO

RY

JO

UR

NA

L

miles away) and two hot dog stands, and matinees at local theaters and later drive-ins.

In 1952, at the age of 10 he accompanied his uncle on a one-day business trip to Chicago. The trip was made on a noisy four-engine pre-jet Viscount that landed at Midway Airport. In pre-freeway days, the cab ride to Evanston was long and very engrossing—so many kinds and sizes of structures. Since Gary’s uncle’s firm was in engineering and firebrick, he got to watch blueprints made on the old-fashioned machines and practice “designing” modern skyscrapers at a time when Miesian modernism had burst into popular consciousness. In the late afternoon they visited the Loop over the ever-magnificent Lake Shore Drive—then twelve lanes wide (he counted them) at the old S-curve by Randolph. After watching the “El” and streetcars on Wabash and State Streets and dinner at a then well-known Chinese restaurant on Lake Street near Wabash, it was back to Midway. The street and building/house lights in twilight and evening were magnificent, even more when airborne ahead of the darkness over the Lake. The great adventure ended with their arrival in Grand Rapids, to the relief of Gary’s parents.

Bert’s Words (Part 14)

“The lowly sleep in peace at night: Pride lies awake and fears a fall.” — Sanskrit proverb

“The trouble with our times is that the future is not what it used to be.” — Paul Valerie

“The trouble with the times is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt.” — Bertrand Russell

CorrectionThe pancake house at Hyde Park Avenue and Lake

Park was an ‘Original Pancake House’, not an IHOP. Quite a difference in my estimation. I had breakfast there nearly every Saturday morn. Now it’s the one at Armitage Avenue and Clark Streeet.

— Claude Weil

New MembersThe Hyde Park Historical Society welcomes new member Camille Hamilton-Doyle.

Vickers Viscount

Hotel Pantlind

HPHS

r2

PH

OTO

CO

UR

TE

SY

AV

IAT

ION

EX

PLO

RE

R.C

OM

PO

STC

AR

D /

TIC

HN

OR

BR

OT

HE

RS

, PU

BL

ISH

ER

3

S u m m e r 2 0 1 7

PH

OTO

S /

MA

RC

MO

NA

GH

AN

PH

OTO

/ M

AR

C M

ON

AG

HA

N

rRenovating HPHS HQs

During the past few months Hyde Parkers have been treated to the view of the renovation of the Society's headquarters by the Professional Masonry Restoration Company, owned by masonry. The owner, Jan Glowicki, has brought his talents to bear to replace and repair the "St. Louis Red" brick walls and conduct other improvements. The project will be completed within a few weeks.

Gary Ossewaarde Comes to Chicago

Gary Ossewaarde, Grand Marshal of the 2017 Fourth of July Parade on 53rd Street in Hyde Park, grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan in the Seymour Square area. Amazingly, one of Gary’s best friends now grew up about a mile away although they never met while attending Calvin College, one of the city’s treasures. Grand Rapids is a mid-sized regional city of many churches, hospitals (now a regional medical megaplex), middle class bungalows, cottages or modest mansions, and a human-scale downtown. Gary especially remembers the Pantlind Hotel with its five! Restaurants and two large department stores, Herpolsheimer’s and Wurzburg’s.

Among the pleasures he recalls are exploring the area on his bicycle, visits to the local airport (then just two

6

r

r

Mystery Quiz:What famous composer conducted his well-

known 8th symphony at the Music Hall of the 1893 World Columbian Exposition?

sits in Good Templar Park, a private park located in Geneva IL, and is closed to the public for much of the year. And the careful work of keeping it dry for the past fifty or so years is being undone by a temporary shelter that no longer keeps off the rain.

It seems unbelievable that the historic vessel has ended up in this condition. But the situation is not entirely without hope. Ownership of the ship may have reverted to the Chicago Park District. And all parties are now seeking a new, permanent location. Cook County Commissioner, Carl Hansen, a long-time advocate of the project, describes all parties involved as committed to saving the ship and giving it a new home where everyone can enjoy this part of their cultural heritage. “We are looking for a permanent location for the ship, before we try again to preserve it,” Hansen said. “We’ve all learned the hard way how hard it is to raise funds for something

when no one knows what will happen to it once it is finished.”

Nothing has been decided yet, and discussions for a new home for the Viking are still underway. Among the possibilities, the Museum of Science and Industry, housed in the last remaining World’s Fair building still located in Jackson Park. Perhaps someday soon, the Viking will once again set sail, and return to the place that has always been its only true destination.

Footnote

In 1978, the Viking Ship Restoration Committee, was formed by the Scandinavian-American community. The American Scandinavian Council bought the ship from the Chicago Park District in 1994.

The ASC moved the ship to a materials yard in West Chicago and secured it under a canopy. Two years later it was moved to the Good Templar Park in Geneva, where it remains on display under a heavy fabric canopy.

In 2012, the trusteeship of the Viking Ship was officially transferred from the CPD to Friends of the Viking Ship NPF in a courtroom signing of an agreed order.

HPHS

The Viking in Lincoln Park Zoo

Viking arrives in Washington Street Harbor

Captain Andersen and the Viking Ship crew of 11

PH

OTO

S /

TH

E D

IGIT

AL

RE

SE

AR

CH

LIB

RA

RY

OF

IL

LIN

OIS

H

ISTO

RY

JO

UR

NA

L

Grand Marshal Gary Ossewaarde

S u m m e r 2 0 1 7r

S u m m e r 2 0 1 7r

5

r

S u m m e r 2 0 1 7r

4

rhad its company’s name attached to the car (“Macy-Benz,” “Mueller-Benz,” “De La Verne Refrigerating Company-Benz”). The fourth four-wheeler was the car built and driven by Frank Duryea. The two two-wheelers were electric vehicles each made by a different company in the United States. Each car had a driver and an “umpire,” that is, an observer who made sure the proper road was followed and all relay stations were visited.

At 8:55am on November 28 when the first car (Frank Duryea’s) took off from Jackson Park there were 6 inches of snow on the ground and a few barely effective horse-drawn snowplows in action on the “race course.” By 9:05, all six vehicles were on the road north. A crowd of spectators attended the start, a few of them equipped with Kodak cameras that attracted almost as much attention as the departing cars.

Somewhere near the center of town, the “Macy-Benz” collided with a horse-drawn vehicle but continued undamaged, in fact, about one fourth into the race, it was ahead of the field. The Duryea car was next. The “Mueller-Benz” was slipping badly on the ice, had twine wrapped around its pneumatic tires, but continued moving steadily. Both electric vehicles were slow, had trouble going uphill and dropped out of the race around its quarter mark. The third Benz car never reached the first relay station.

Years later, Frank Duryea penned an autobiography and wrote about the race. Here are some excerpts: “The Duryea was the first car away ...and made good going. It was in the lead when the left front wheel struck a bad rut at such an angle that the steering arm was broken off... we, fortunately, located a blacksmith shop where we forged down, threaded and replaced the arm. While thus delayed, the “Macy-Benz” passed us and held the lead as far as Evanston, where we regained it. Having made the turn at Evanston, elated at being in the lead again, we started on the home trip. We had not yet come to Humboldt Park, when one of the two cylinders ceased firing... This repair was completed in fifty-five minutes and we got going, feeling that the “Macy-Benz” must surely be ahead of us, but learned later that it did not get that far... After a stop for gasoline and a four minute wait for a passing train at a railroad crossing, we continued on to the finish in Jackson Park, arriving at 7:18 p.m. The motor had at all times shown ample power, and at no time were we compelled to get out and push.”

Frank Duryea and his car were the winners but he remains rather sober and writes simply: “After receiving congratulations from the small group still remaining at the finish line, among whom were the Duryea Motor Wagon Company party, I turned the

car and drove back to its quarters... The “Mueller-Benz,” the only other machine to finish, was driven across the line at 8:53 p.m. by the umpire, Mr. Charles B. King, Mr. Mueller (the original driver) having collapsed from fatigue.”

The winner’s “elapsed time” from start to finish was 10 hours and 23 minutes for the 54-mile (87 kilometers) course. Actual “running time” for the car was 7 hours and 53 minutes which made for an average “running speed” of 6.66 miles per hour. The “official distance” of the route turned out to be 52.4 miles. The race was an endurance test not only for these early automobiles but also for the drivers, umpires, and observers who spent the day in snow and cold temperatures, with little protection from the elements.

The winner received a cash prize of $2,000 (worth over $50,000 in today’s money). The runner-up was given $1,500.

Newspapers all over the US and around the world reported on the race in Chicago and speculated about the future of this new invention, the “horseless carriage,” “motocycle,” “automobile.” The increased interest pushed development in the field and led to the first commercial production of automobiles in the US just a year later. And it may have been the beginning of Americans’ infatuation with cars which is alive and well to this day.

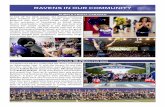

Recent HPHS eventsOn Thursday morning, June 8, 16 Hyde Park

Historical Society members were treated to a special exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry commemorating a new exhibit about the Manhattan Project—the founding of the Atomic Age, especially as it affected Chicago. Memories were stirred about this historic event, much of which took place in this part of Chicago.

Also, on Saturday, June 17, another program for outstanding local history fair projects was held at the Augustant Lutheran Church. The program included a panel led by Jay Mulberry, Timuel D. Black, Jr., and Maryhelen Matijevic, Assistant Principak, Mt. Carmel High School. Projects included “Jane: The Fight for Equality,” William H McNeill, and the

A VOICE FROM CHICAGO

America’s First Automobile RaceBy Vreni Naess

It took place on November 28, 1895 (Thanksgiving Day). The race started in Chicago’s Jackson Park, about ten walking minutes south of where I live (and would have gone by very close to my building which, however, was not constructed until 1909). It continued north along Lake Michigan to Evanston, Chicago’s closest suburb to the north, and back to my neighborhood. The distance was 54 miles (87 kilometers). The road on the day of the race was snowy, icy, rocky, sandy in spots, with ruts, potholes, and snowdrifts. The competing “motocycles” (a name coined by the editors of the newspaper sponsoring the race) were either a two-wheeled or a four-wheeled open vehicle, powered by an electric battery or a gasoline motor.

While Henry Ford usually receives most of the credit for developing the automobile in the United States, he did not actually produce the first American car. That was the achievement of two brothers, Charles and Frank Duryea, who built the first gasoline-powered “horseless carriage” in the state of Massachusetts (MA) in 1893.

Just like the Wright brothers, the Duryea brothers were bicycle mechanics with an interest in motors and innovation. They built their first car in a workshop in downtown Springfield, MA. In September 1893, their “horseless carriage” had its first test run on the streets of their hometown. It had a one-cylinder gasoline

engine and a three-speed transmission mounted on a used horse carriage and was able to reach a top speed of 7.5 miles per hour, about double that of a horse and carriage. It was open and offered no protection to its driver and passengers.

A year later, Frank developed a second car with a more powerful engine. That was the car he drove in America’s first automobile race which was sponsored by the Chicago Times-Herald to promote the young “motocycle” industry (just two years old) and to boost sales of its own newspaper.

The race was originally intended for November 2, but by that date only a few cars had shown up and it was postponed to a later date. Eighty-three cars were originally registered for the race but only six actually arrived for the competition. Many were unable to complete the journey because of mechanical breakdowns, bad roads and weather. Several proposed entrants did not finish building their “motocycles” in time for the race.

The first two cars to arrive in the city were stopped by the police and told to get horses to pull them “as they had no right to drive a motorized vehicle on city streets.”

This caused the race date to be postponed a second time while the Times-Herald editors scrambled to convince the city leaders to quickly pass an ordinance

giving “motocycles” the right to drive on Chicago’s streets. Once the ordinance was passed, the final date for the race was set for November 28, 1895.

On the day, six cars were ready to start, four four-wheeled and two two-wheeled. Three of the cars were built in Germany by Karl Benz (considered by many to be the original inventor of the gasoline-powered car), and each of those had a sponsor that

The winner

HPHS

Historical marker of the first automobile race

PH

OTO

/ F

RA

NC

ES

VA

ND

ER

VO

OR

T