Human ecology and the early history of St Kilda, Scotland

-

Upload

andrew-fleming -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

1

Transcript of Human ecology and the early history of St Kilda, Scotland

Journal of Historical Geography, 25, 2 (1999) 183–200

Article No. jhge.1999.0113, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on

Human ecology and the early history ofSt Kilda, Scotland

Andrew Fleming

It is 300 years since Martin Martin published his Voyage to St Kilda, one of the mostinformative accounts ever published of a seventeenth-century community. Historicaltreatments of St Kilda have often dramatized its isolation, distinctiveness and ‘mar-ginality’ but Martin’s writings suggest that the lifeways of the St Kildans were not verydifferent from those of contemporary Hebrideans. The economy described by Martinwas subject to a rigorous regime of communal self-management. This article arguesthat in late medieval climatic conditions, St Kilda’s particular combination of resources—sheltered arable land, seals and sea-bird colonies, including a huge gannetry—wouldhave made the archipelago a valued component of the MacLeod chiefdom and a goodtarget for the annual predatory visit of the sub-chief and his retinue. St Kilda’s historyshould be seen not in isolation, but in a context of regional interdependence, and thearchipelago’s ‘marginality’ is best understood in a long-term historical perspective.

1999 Academic Press

Introduction

The St Kilda group of islands (Figures 1 and 2) lie some 55 km WNW of North Uistin the Western Isles of Scotland. There never was a St Kilda; the name has arisen froma misunderstanding.[1] There is one habitable island, Hirta (formerly Hirt), which hasan area of 637 hectares.[2] Just off Hirta’s north-west tip is Soay (99 hectares) and 6 kmto the north-east lies Boreray (76 hectares). These two islands, girt by steep cliffs, havetraditionally been utilized as sheep pastures and as temporary bases for fowling parties.

St Kilda has an extensive literature, fed by its spectacular scenery, its remoteness,the real or apparent cultural idiosyncracies of its former inhabitants, and the dramasurrounding its abandonment in August 1930. Commentators’ emphasis on isolation,distinctiveness and marginality have had the effect of making the archipelago bothspecial and apparently irrelevant to regional history. The three existing modern accountsof St Kilda’s history, those by Steel, Maclean and Harman, are all excellent in termsof their own objectives.[3] But if archaeological research is to build upon evidenceprovided by the written record, we need to make a sober appraisal of St Kilda’s‘distinctiveness’ and to set this island group into the context of the long-term historyof north-west Scotland. That is what this article attempts to achieve.

Three hundred years ago, on the 29 May 1697, Martin Martin set sail for StKilda. On his return he wrote Voyage to St Kilda (1698), one of the earliest detailed‘anthropological’ studies of a small community anywhere in Britain. Martin also wrotea section on St Kilda in his A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland (1703). His

1830305–7488/99/020183+18 $30.00/0 1999 Academic Press

184 A. FLEMING

Figure 1. The St Kilda archipelago (inset) and the main island of Hirta, including placesmentioned in text (for general location, see Figure 2). This map marks the 1830 head dyke inVillage Bay, enclosing the 16 crofts instituted by Neil Mackenzie. Contours at 90, 150, 210, 270

and 330 m.

account of St Kilda represents the dawn of written history for this island group, whoseprehistoric past survived until the early thirteen century.[4] Almost four centuries ofprotohistory stand between the first written reference and the Voyage. Martin’s accountthus forms the starting-point for any archaeologically-based investigation of St Kilda’sprehistory. A further objective of this article is to provide a baseline study of St Kildaas it emerged into history.

At first sight, the Voyage is especially valuable because it pre-dates the re-populationof Hirta from Skye and Harris, after the smallpox epidemic of 1727, which was survivedby only seven adults and thirty-four children.[5] Martin’s account of Hirta is sometimesread as a vision of the island ‘uncontaminated’ by this fresh influx of people. Infact, anecdotes from post-1727 sources provide excellent illustrations of the customs

185EARLY HISTORY OF ST KILDA

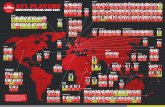

Figure 2. Map to show the modern distribution of main seabird colonies and breeding groundsof the grey seal in north-west Scotland, and the locations of places mentioned in the text. B=Barra, Be=Berneray, H=Harris, L=Lewis, NU=North Uist, R=Rodil, Sk=Skye, SU=South

Uist. Source: J. M. Boyd and I. L. Boyd, The Hebrides: A Natural History (London 1990).

documented by Martin. The smallpox survivors, few as they were, seem to have passedon a good deal of the pre-existing Hirta culture. The situation is potentially confused,however, because life on Skye and Harris was quite similar to life on Hirta. All threeareas were part of the MacLeod chiefdom and the respective environments had a gooddeal in common. But the evidence of place-names is telling. According to Coates:

most of the larger islands of the St Kilda group have names of Scandinavian origin,despite a lengthy period of Gaelic-speaking there since the period of Nordic dominance.Numerous small features have names that show every sign of having been formulatedin a Nordic language, rather than to contain elements of Nordic origin (which mighthave been borrowed and used by Gaelic speakers and thus not prove Scandinavianoccupation).[6]

186 A. FLEMING

These names survived the 1720s re-population of Hirta as well as the resurgence of theGaelic language. In the long term, disastrous events may almost wipe out the populationsof small islands like Hirta. Yet if the will exists to re-populate them, it may not requiremany survivors to transmit detailed cultural information to the new settlers. The impactof disasters upon long-term cultural continuity may be smaller than one might at firstimagine.

The St Kildans of Martin’s time formed a community which managed its economicaffairs according to a strict code of rules. They lived within the MacLeod chiefdom,which was based on Skye and Harris, and every summer saw the arrival of the ‘steward’(a sub-chief from a cadet branch of the MacLeods) and his retinue.[7] Martin, who wasfactor to the paramount MacLeod chief (based at Dunvegan on Skye) and who latertrained as a doctor in Leiden,[8] romanticized the St Kildans, characterizing them as“much happier than the generality of mankind”.[9] His ‘noble savage’ passages are brief,however, and clearly defer to contemporary literary conventions. In most respectsMartin was a shrewd observer of the Hirta scene.

St Kilda and its neighbours

St Kilda has an extensive literature.[10] Commentators have usually dealt with thearchipelago in isolation, emphasizing its people’s adaptation to a set of peculiar andchallenging conditions. But a comparison with Martin’s Description of the Western Isles(1703) demonstrates just how similar were the St Kildans’ lifeways to those of theirneighbours. The St Kildan dress, apparently, was “much like that used in the adjacentisles” only coarser.[11] Visited every summer by the MacLeod retinue, the St Kildansindeed had little excuse for being unaware of changes in Hebridean fashion. On thefeast of All Saints they held a ‘cavalcade’, riding their horses from the beach to thevillage guided by a simple straw rope[12] and eating a large triangular cake before thenext day.[13] Martin recorded the presence of this Michaelmas–All Saints cavalcade,with varying degrees of detail, in other parts of north-west Scotland.[14]

The beliefs and customs of the St Kildans resembled those of their neighbours invarious interesting ways. These members of the Reformed Church fancied “spirits tobe locally in rocks, hills or wherever they list”.[15] Macaulay says that on the road toGleann Mor was a stone where “formerly” (pre-smallpox) they poured “libations” ofmilk to the gruagach; a kind of stone which existed “in almost every village throughoutthe western isles”.[16] A little above this was liani nin ore, the “plain of spells”, wherethe “old” St Kildans “sanctified” their cattle with salt, water and fire “every time theywere removed from one grazing place to another”.[17] The St Kildans shared an interestin the sacred and medicinal aspects of wells and springs with many other Hebrideans.[18]

They also shared with the people of North Rona a belief that the rarely-heard cuckoo’scall indicated the recent death of the clan chief. On St Kilda, this might also portendthe arrival of some notable stranger.[19] They knew that sea-weed ash was a goodpreservative and to some extent a salt substitute, knowledge which they shared withthe inhabitants of North Uist and Berneray (south of Barra).[20] The St Kildan harrowswith wooden front teeth in front of bundles of sea-weed or heath were comparablewith those which Martin recorded on Lewis.[21]

Only their thin beards and notable strength set the people of Hirta apart physicallyfrom “those of the Isles and Continent”.[22] Like their fellow Hebrideans, the St Kildansevidently liked poetry, music and dancing; they had a piper who could imitate thepiping of the gawlin.[23] Like other Hebrideans,[24] they much enjoyed alcoholic drinks

187EARLY HISTORY OF ST KILDA

when they could make or get hold of them.[25] The ‘Parliament’ of later fame is mentionedonce, and described as “a general Council, in which the master of every family has avote”.[26] Judging by the numerous occasions on which it was necessary to draw lots orseek the headman’s arbitration, the council must have met quite frequently.[27] Therewere also what Martin calls women’s “assemblies” which took place in the middle ofthe village, to the accompaniment of singing, poetry-making, and work.[28]

From Martin’s account it appears that fowling and its associated customs were fullyestablished in 1697. The St Kildans practised the basic techniques of rock climbing,including ‘leading’ climbs and roping climbers together. When they climbed Stac Biorachin Soay Sound they belayed a rope from the top.[29] They knew enough about thenatural history of the gannet, for instance, to time the harvest of their eggs carefully,as between Stac Lee and Boreray.[30] There were several corbelled store-houses, thefamous cleits or cleitean, what Martin calls “pyramid-houses”, on Stac an Armin, about40 on Boreray, and a bothy on Stac Lee.[31] Eggs were preserved in the cleits in bedsof turf ash, and birds were dried in them for up to a year. Gannets’ feet might also becut with distinguishing owners’ marks.[32] Martin’s map makes it clear that two majorhills—Conachair and Oiseval—were already festooned with “stone pyramids” and hesuggests[33] that there were over 500 of them (the present-day figure is about 1200 onHirta, and some 170 in other parts of the archipelago).[34] Given that the populationwas in decline after Martin’s time, it seems likely that most of the small, old-lookingcleitean outside the area of the village pre-date the late seventeenth century. Sir RobertMoray noted their existence two decades earlier than Martin’s visit.[35] The cleits wouldcertainly have been in existence by 1549, when reistit (dried) mutton and sea-birds werepart of the local diet.[36] St Kilda’s ‘bird culture’ did not set the archipelago apart. Most,perhaps all bird-covered stacks in north and west Scotland were targetted by localcommunities.[37] The skills known to the St Kildans, and the dangers which they regularlyfaced, were to be found wherever gannets whitened a stack.

The relative isolation of St Kilda in the late seventeenth century did not mean thatit was ‘old-fashioned’. Martin recorded that “both sexes have a great inclination tonovelty”.[38] By Martin’s time they had taken enthusiastically to tobacco.[39] Despite thecomplains of Buchan[40] about popery, ignorance and the shortcomings of religiousleadership in the earlier seventeenth century, Martin records that the St Kildans were“of the reformed religion . . . neither inclined to Enthusiasm nor to Popery”.[41] Theykept the Sabbath and regularly attended open-air services, as the church was too smallto hold them all.[42] A school was established on St Kilda in 1711.[43]

In the context of the contemporary lifeways of the Hebrides, late seventeenth centuryHirta was ordinary enough in most respects. In regional terms, Hirta was part of theMacLeod chiefdom, which covered much of Skye and Harris and was centred atDunvegan on Skye.[44] The St Kildans had to maintain the retinue of the sub-chiefduring its annual visit. In Martin’s time, the ‘steward’ lived on Pabbay in the Soundof Harris.[45] He collected tribute in the form of “down, wool, butter, cheese, cows,horses, fowl, oil, and barley”.[46] The late seventeenth-century retinue contained 40 to60 persons, according to Martin.[47]

The community of St Kilda

The community of 1697, numbering 180 to 200 people, ran a very carefully-managedeconomy, with strict rules governing the distribution of resources and the avoidance ofconflict.[48] One of the most valuable aspects of Martin’s account is that it allows thereconstruction of a commons in the ‘regulated’ state in considerable detail.[49]

188 A. FLEMING

Martin reported that St Kilda’s arable land was “very nicely parted into ten divisions,each distinguished by the name of some deceased man or woman” which echoes Moray’sreference to ten “families”.[50] This would produce an average of about 18 to 20 personsper “family”—arguably a small lineage of siblings, with their spouses and children,plus survivors from the older generation. A small number of “poor” were the jointresponsibility of the community.[51] The reference to both male and female ancestorsmay suggest that the history of Hirta had encompassed both patrilineal and matrinealdescent, and that, in the past or the present, the people were able to take advantageof the flexibility of a bilateral kinship system. The ten-fold division of land and peopleshould have facilitated the monitoring and control of food supplies, work allocationand family recruitment at a realistic scale, without generating costly community-leveldisputes. According to Martin, there were about 90 cows, up to 18 horses and perhaps2000 sheep on the island: “the richest man hath not above eight cows, eighty sheep,and two or three horses”.[52] If all adult males were potentially livestock owners, andthere were 40 of them, or if there were about 30 (presumably nuclear) families orhouseholds at this time,[53] the average household would have owned 50 or 60 sheepand two or three cows. One household in two would have owned a horse. Within apredominantly egalitarian distribution of resources, there was a potential for short-term accumulation for exchange or payments made at marriage: “if a native here havebut a few cattle, he will marry a woman, tho she have no other portion from her friendsbut a pound of horse-hair, to make a gin to catch fowls”.[54]

Control of other resources must be taken into account. Martin claimed that theprevious year’s gannet harvest amounted to 22 600, a bad year, apparently.[55] Thisfigure is regarded as a gross exaggeration by Nelson who suggests that a cull of only2000–3000 adult birds and 5000 gugas (young ones) would have meant that thepopulation could not have held its own without immigration.[56] Gannet-hunting wasassociated with masculine prowess and ability to win a wife. Martin records that theplucked carcasses of the fattest fowls were taken home from the stacks “to their wives,or sweethearts, as a great present, and it is always accepted very kindly from them,and could not indeed well be otherwise, without great ingratitude, seeing these menordinarily expose themselves to great danger, if not to the hazard of their lives, toprocure these presents for them”.[57] This present was known as the “rock fowl”.[58]

Women did most of the agricultural work on Hirta, using “a kind of crooked spade”.[59]

On the basis of later accounts, it seems likely that females were also responsible fordairy work and were involved in puffin-snaring expeditions.[60] Moray wrote that “themost service of their women is to harrow the land, which they must do, when theirhusbands are climbing for fowls for them”.[61] As we have seen, there were male andfemale ‘assemblies’ echoing this gendered division of labour.

The Hirta community divided responsibility equally between ‘families’ for the main-tenance of collective property, drawing lots to randomize exposure to risk, to allocateresources which could not be split into ‘equal’ shares, and to establish a rota for accessto a facility which could only be used by one family at a time. For instance, lots weredrawn for the use of the common corn-drying kiln.[62] The island’s boat was “verycuriously divided into appartments proportional to their land and rocks” and when itwas beached in summer each “partner” had to supply “a large turf to cover his spaceof the boat”.[63] It seems that “lands, grass, and rocks” were frequently re-allocatedunder the leadership of the headman or maor, the “officer” as Martin calls him.[64] Thethree long climbing ropes, made of horse-hair, were communal property and were “notto be used without the general consent”. Lots determined the time, place and personsusing them.[65] The risks taken by particular individuals were thus consigned to chance

189EARLY HISTORY OF ST KILDA

or fate. The lottery for fowling and fishing rocks would have randomized the distributionof variable and often unpredictable resources and it also aimed to ensure even coverageof fowling areas in different sectors of the Hirta coastline.[66]

Where shared provision was impractical, individual families were rewarded forsupplying a critical resource. On expeditions to Boreray, for instance, the provider ofthe steel and tinder-box was paid the ‘fire-penny’, and the provider of the iron cooking-pot was paid the ‘pot-penny’ by each family. The duty to provide the pot rotatedbetween families. Good commons management also included payment by each familyof an amir of barley per annum to the maor, as also happened in the case of thesouthern and lesser isles of Barra.[67] The role of the maor was crucial to the successfulworking of the system. He was ‘speaker’ of the mod or ‘parliament’ and presidedimpartially over the drawing of lots.[68] Martin makes it clear that he was traditionallychosen by “the people”.[69] As his duties also involved leading the most hazardousfowling expeditions, as well as rock climbs, he must have been selected largely on merit,a natural leader combining physical skills, intelligence, knowledge and a personalitywhich inspired trust.[70] The community also shared the responsibility of welfare provisionfor the poor, hospitality for guests and ship-wrecked sailors, and above all for feedingand billeting the retinue of the MacLeod steward, during his annual visit.[71] Aspectsof this strict system of self-regulation were preserved until the very last days of theHirta community. In the 1980s, Lachlan Macdonald, who was 24 when the island wasevacuated in 1930, recalled how responsibility for feeding the bull in winter was sharedbetween the crofters who used an agreed rope measure to equalize the size of thebundles of hay provided: “they never quarrelled about it”, he insisted.[72] It might besuggested that the particularly difficult conditions of the St Kilda environment werelargely responsible for the development of such a comprehensive and rigorous systemof community regulation. However, Martin also recorded aspects of similar rules andregulations in other parts of north-west Scotland.[73]

St Kilda and the MacLeod chiefdom

The MacLeod retinue had been paying its annual visit since at least 1549.[74] Accordingto Martin, by 1697 the numbers were “retrenched”, as were some of its “ancientand unreasonable exactions”.[75] If, as Martin suggests, the late seventeenth-centurypopulation of around 200 was visited by a retinue of 50 for two months, the islanderswould have to increase their annual output by just over four per cent to feed them;rather more if considers that most, if not all, visitors would be adult whereas a relativelylarge proportion of St Kildans were children. It is hard to know the size of the additionalburdens imposed upon the islanders by the tribute which they were obliged to pay.They were obliged to produce a surplus of some kind to exchange for commodities ormaterials produced elsewhere; as Martin states, they “barter among themselves and thesteward’s men for what they want”.[76]

The visit of the sub-chief and his retinue was accompanied by various customs andrituals: exchanges of presents, the obligation to provide the sub-chief with ‘a large cakeof barley’ at every meal, with mutton or beef for Sunday dinner, and the show ofresistance offered to the sub-chief by the maor, with its ritual acknowledgement by atleast three cudgel blows to the head.[77] How far were the St Kildans disadvantaged bythis arrangement and to what extent were they at the mercy of the chiefdom? Evidenceand argument suggest that the relationship between the MacLeod chiefdom and theHirta community was one of mutual benefit which partly transcended the calculus of

190 A. FLEMING

economics. Clan loyalty evidently impelled the St Kildans to “mourn two days in thefields” when they heard of the chief’s death.[78]

It was certainly in the interests of the chiefdom to look after its component resourceareas. Martin recounts how the islanders’ boat was “split to pieces” on Boreray, andthe crew saved themselves by their climbing skills.[79] He omits details on how the crewwere rescued and how the boat was replaced, as if there was nothing remarkable aboutsuch an occurrence. When the island’s boat was lost, it was replaced by the chiefdom.Harman records the purchase of new boats in 1712 and 1735, and her summary of theevidence shows that there were two or three boats on Hirta in the late eighteenth andearly nineteenth centuries, and more than one in the 1740s.[80] The chiefdom must alsohave supplied Hirta with horses (or at least foals), if the written sources are correct instating that horses were absent in the late sixteenth century, but present in 1615.[81]

For their part, the St Kildans may have been more independent and prone to takeinitiatives than is sometimes recognized. They also resisted the chiefdom in somecircumstances. Martin records several instances of their ingenuity in emergencies.[82]

They were far from slow-witted, and their courtesy was not subservience. Martinrecords how several years before his arrival, the sub-chief, claiming a precedent, hadattempted to “exact a sheep from every family in the isle”. The St Kildans refused,explaining the special circumstances in which the alleged precedent had been set. Whenthe sub-chief tried to use force, the St Kildans armed themselves with daggers andfishing rods, gave his brother several blows on the head, and told him they would payno new taxes—“by this stout resistance, they preserved their freedom from suchimposition”.[83]

An argument broke out, apparently during Martin’s visit or not long before it, aboutthe measure used in payment of tribute which

has been used these fourscore years; in which tract of time it is considerably fallen shortof the measure of which it was at first, which they themselves do not altogether deny;the steward [sub-chief] to compensate this loss, pretends to a received custom of addingthe hand of him that measures the corn to the Amir [measure] side, holding some ofthe corn above the due measure, which the inhabitants complain of as unreasonable.

One can picture the scene: cunning, disingenuity, a contest of wills. In the end, the StKildans resolved to send the headman to Dunvegan to present their case. It appearsthat it was not uncommon for embassies of this kind to take place, with the crew ofthe boat, normally comprizing at least one representative of each family, accompanyingthe headman.[84] Although Martin makes much of the local modes of baptism andmarriage when there was no permanently resident priest,[85] Sir Robert Moray claimsthat 15- and 16-year-olds were brought to Harris by the headman to be baptized,presumably in the church at Rodil.[86]

One cannot leave the subject of ‘resistance’ without touching upon the gruesometopic of the two murders mentioned by Mackenzie, writing in the nineteenth century.[87]

In one case, one of the sub-chief’s female servants married into the island and wassuspected of being her former master’s spy. In the temporary absence of her husband,the women of the island persuaded her onto the shore to gather limpets. The men thenput a loop of rope around her neck and strangled her by pulling on each end: “all tookpart in it, so that all might be equally guilty, and thus less risk of anyone informing”.This story was recounted by a minister discussing the moral condition of his flock butthe actions of the participants sound very St Kildan, communitarian even in crime.The other anecdote is about the murder of a male also suspected of compromizedloyalties. These stories remind us that members of the retinue may well have refreshed

191EARLY HISTORY OF ST KILDA

the ‘breeding stock’, helping to lessen the extent of inbreeding.[88] Evidently the retinuecontained at least some women, including the sub-chief’s wife, who presented the wifeof the maor with a head-dress and an ounce of indigo.[89]

So although Martin characterized the people of Hirta as exceptional—“the onlypeople in the world who feel the sweetness of true liberty”[90]—his account describes adisciplined, hard way of life, not obviously dissimilar to the lifeways in other parts ofthe Hebrides. The annual visit of the retinue, although predatory, was essential to thecontinuing existence of the St Kildan community, and it kept the people in touch withthe outside world. It can be argued that the ‘strangeness’ of the people of Hirta becamemore and more apparent in the post-Martin centuries, when the gulf between theirlifeways and those of other parts of north-west Scotland widened. St Kilda, after all,saw no ‘clearance’, and its ‘improvement’ in the 1830s was by persuasion and communalagreement. The people evidently saw Mackenzie’s reforms as an opportunity to redefinetheir agrarian system:

they wished to have the land (which they had hitherto held in common) divided amongthem, so that each might build upon his own portion . . . with some difficulty I gotthem at last to agree to divide the land themselves, and when they had made thedifferent portions as equal as possible, then to apportion them by lot. This they didand were satisfied.[91]

This mode of community self-management—meticulous subdivision, followed by thedrawing of lots—is also very St Kildan. It precludes further discussion as well asallowing the intervention of God, or fate.

Later, more and more visitors came to Hirta as tourists. They wanted to see strange,old-fashioned St Kildans, and the islanders duly obliged. There is a famous ‘Parliament’photograph which is obviously posed, although long time exposures were of coursecharacteristic of photography in the late nineteenth century.[92] For the last hundredyears of St Kilda’s existence as an inhabited island, there was another mutually beneficialrelationship between the islanders and their visitors—collaboration in the cultivationand perpetuation of an image of exoticism. As Connell put it in 1887: “the studentwho allows himself to be sent to train the young St Kilda idea . . . is quite as entitledto the gratitude of his church as the missionary who goes to Old Calabar or theCannibal Islands”.[93] In the post-1930 period, this perception must have been a powerfulinfluence on the production and sale of books about this tiny archipelago.

Demography and the economy

From the chiefdom’s point of view, Hirta was well worth the annual visitation. It isnot clear that the MacLeod would have concurred with Dodgshon, in leaving it off a mapof MacLeod domains![94] Dodgshon argues that gathering food-rents, with increasinginsistence and urgency, was the main concern of these chiefdoms.[95] The retinue’s longstay on Hirta, and some of its activities, were almost certainly illegal. The earlyseventeenth-century Statutes of Iona had banned sorning (the forcible extraction ofhospitality) and the forcible demanding of gifts. The size of the retinue may well havecontravened the spirit, if not the letter, of these statutes.[96] In all these circumstances,it is worth considering the possibility that Martin’s Hirta had descended from areasonably prosperous, populous late medieval community, sustainable if not quite self-sustaining.

Such a claim must, of course, be weighed against our knowledge and understandingof Hirta’s demographic history. Martin’s population figures of 180 or 200 are higher

192 A. FLEMING

than any recorded later, but the implied ratio between families (quoted variously at 27,30 or 33 around this period) and absolute population numbers fits the norm for thispart of Scotland at that time.[97] Harman has described the dietary and health problemsof the St Kildans in the early eighteenth century, problems which supposedly madethem more vulnerable to the smallpox epidemic of 1727.[98] She argues that after theepidemic and the re-population of Hirta, neo-natal tetanus kept population levels fairlystable.[99] Numbers from the mid-eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries fluctuatedaround 100. By the time the causes of these infant deaths were understood and theinfection could be prevented, in the final years of the nineteenth century, other factorscame into play. The community’s age and sex profile had changed drastically andirredeemably after the emigration of 36 people to Australia in 1856.[100]

How, then, are we to regard the relatively large population of the late seventeenthcentury? Harman argues that Hirta had been re-populated earlier in the century, perhapsin response to Coll McDonald’s raid in 1615, although she points out that if the re-colonization had been substantial it would surely have been mentioned directly byMartin.[101] But she also suggests that “180 was too great a number for the island tosupport”.[102] However, this was the period of the Little Ice Age when climatic conditionswere creating havoc along the coasts of north-west Scotland.[103] On Hirta, Walkerinterpreted zone GM-5 on his pollen diagram for Gleann Mor as demonstrating thelocal effects of the Little Ice Age, with increasing amounts of salt spray leading to anexpansion of maritime plant communities.[104] Both crops and sea bird biomass wouldhave been seriously affected. Deficiency diseases and malnutrition, as Harman pointsout, would have diminished the islanders’ economic performance and worsened theirconditions of existence.

A population of between 180 and 200 may have been too high for the conditions ofthe Little Ice Age but it is by no means clear that it would have been unsustainable inthe climatic conditions of the twelth and thirteenth centuries or comparable conditionsin earlier times. The MacLeod retinue had evidently been turning up annually on Hirtaand claiming cuddiche since at least the early sixteenth century.[105] It was suggestedabove that in Martin’s time the St Kildans may have had to produce an extra four orfive per cent above their own requirements in order to feed the retinue, in addition tothe extra production represented by the goods and produce taken away by the sub-chief. In Martin’s day, each of the 30 or so families had two extra persons to support(and perhaps to accommodate). According to Martin, the late seventeenth-centurynumber of 40 to 60 persons was “retrenched” and their “ancient exactions” had oncebeen greater.[106] If this is true, the implication is that in earlier times the retinue hadexpected to visit a relatively populous and prosperous island. If, as Harman implies,St Kilda’s normally sustainable population was nearer to 100 than 200, with perhaps16 families (the number of holdings which corresponded to these population levels inthe nineteenth century), and if we believe Martin’s statement about the traditional sizeof the retinue, then the burden on the islanders in the sixteenth century appears hardto sustain. In the early nineteenth century, the St Kilda population of 100 or so includedonly 40 to 50 adults in the physical prime of life, ranged between 15 and 44 years ofage.[107] Would a population of around 100 really have been able to support a retinuein which visiting adults outnumbered native adults by two to one?

Other arguments are worth considering. I have suggested elsewhere that the ‘regulated’stage of commons development should relate to a time when population is relativelyhigh in relation to resource availability and/or when there is a demand for greaterproductivity.[108] In St Kilda, it is hard to imagine how the community could havebecome more than mildly involved in the competitive generation or accumulation of

193EARLY HISTORY OF ST KILDA

‘wealth’. As we have seen, the level of mutual interdependence in economic productionwas very considerable. But one could easily envisage a highly regulated system developingin response to rising population numbers, or the demands of a predatory external elite,whose perception of Hirta’s potential wealth had to be realistically grounded in thelonger term, or a situation of mutual feedback between these two factors, perhaps inrelatively favourable climatic conditions.

This is where we must ask how ‘rich’ were the St Kildans, potentially and in relationto their neighbours. According to Martin, Hirta grew the finest barley in the WesternIsles.[109] In the mid-eighteenth century, Macaulay commented favourably on the highquality of the pasture and the quantity and richness of the milk, and on the potentialof the arable land which was “rendered extremely fertile by the husbandry of veryjudicious husbandmen”. The barley, it appeared, ripened earlier than anywhere else inthe Western Isles. Macaulay also claimed that the island should be able to supportabout 300 persons.[110] The availability of marine resources must have been a considerablebonus. Their present-day Hebridean distribution displays some interesting patterns(Figure 2). According to Boyd and Boyd, St Kilda is by some way the largest ‘seabirdisland’, followed by three ‘medium-sized’ islands (Handa, Shiant, Rum) and a groupof lesser islands (still with over 20 000 breeding pairs) consisting of Sula Sgeir, NorthRona, Flannan, Mingulay and Berneray (south of Barra).[111] These colonies are quiteevenly spaced, and the distances between them are considerable. Boyd and Boyd indicatethat St Kilda is currently host to five-sixths (50 000 pairs) of the gannets in the Hebrides,almost half the fulmars (63 000 pairs) and about three-fifths of the puffins (230 000individuals).[112] Gannets and their eggs were at most times a prized resource, “a delicacyat all Scottish banquets” according to Nelson.[113] The gannet seems to have been easilythe most exploited seabird in the region’s Iron Age (in the broadest sense).[114] As criticallocations for gannets, only St Kilda, Sula Sgeir and possibly the Flannans come intoconsideration in today’s circumstances.[115] Writing of the fulmar, Martin recorded that,as well as taking the oil, which had medicinal uses, “the inhabitants prefer this, whetheryoung or old, to all other; the old is of a delicate taste”.[116]

Seal-breeding locations for the grey seal have a largely complementary distribution.[117]

Most are to be found in the central west zone of the Long Island—between Gaskerand the Monach Isles (Figure 2). The main seal islands and the main seabird islandsonly overlap on North Rona and St Kilda. In Martin’s day, seals were an importantresource, though he usually states or implies that it was only the poor or the “vulgar”who hunted them. The St Kildans certainly hunted seals. As far back as 1549, Monrorecorded that the sub-chief was fed with ‘reistit [dried] muttonis, wild reistit foullis andselchis [seals]’ on his visits to Hirta.[118] George Buchanan also mentioned tributes ofseals and sea-birds.[119] Moray tells of seal-hunting in Soay Sound.[120] The number ofseals breeding in the archipelago, however, is constrained by the restricted number ofsuitable sites, which would also have been limited in the past by the human presencehere. It is noteworthy that just before the arrival of the military in 1957, when Hirtawas unoccupied, seals were beginning to haul out in Village Bay itself.[121]

If we may project the recent ecological situation in the Hebrides backwards into thelater Middle Ages, and if outlying rocks and stacks were generally claimed and defendedas the hunting and fowling grounds of the communities which were nearest, or couldreach them most easily, it appears that quite a small number of communities wouldhave had access to seal-breeding locations and major seabird colonies. The St Kildanswere apparently unique in controlling seal-breeding grounds and major seabird coloniesand a major gannet colony. The inhabitants of North Rona had access to birds andseals, but North Rona is considerably smaller than Hirta and does not possess the

194 A. FLEMING

latter’s acreage of relatively sheltered agricultural land. Furthermore, St Kilda had nonear neighbour to compete for fowling and fishing rights. Of course, projecting today’secological situation backwards in time may be unwise. Potential changes in coastal andecological conditions, as well as in inter-specific relationships, have to be taken intoaccount. There is evidence, however, that major gannet colonies have displayed con-siderable long-term stability in recent centuries (human predators having been the mainthreat to them). A major cause of such stability is the fact that young gannets returningnorth in the spring are normally attracted to existing colonies as potential breedingsites.[122] As Nelson says (his emphasis): “there are many islands and headlands thatgannets probably could use, but at present do not. Undoubtedly, traditional gannetriescould absorb many more thousands of pairs before major new ones became necessary”.The critical point is that “dense nesting provides behavioural (social) stimulation whichenhances reproductive success”.[123] Choice of colonies is also restricted by the gannet’sneed for wind-assisted take-off and landing. Although gannets apparently can and docolonize relatively flat sites, such as low islands, human predation is a major determinantof colony survival and success. Given our knowledge of the vigour and ingenuity ofthe human food quest over the past ten thousand years or so, and the attraction andcapacity of existing colonies from the gannet’s point of view, it seems likely that by theMiddle Ages the large and enduring gannetries will have been more or less confined tothe stacks which they occupy today.[124]

These marine resources would have given St Kilda an advantage over many othernorth-west Scottish communities. They were an extra source of food as well as a risk-buffering mechanism when the cereal harvest was in trouble. Furthermore, the cleits inwhich dried birds were stored were also available for the storage of dried mutton, theuse of which in the seventeenth century was recorded by both Munro and Buchanan.[125]

It would have been possible to store varying proportions of wind-dried birds andmammals—seal as well as perhaps sheep—switching between them according to pre-vailing conditions. These practices are reminiscent of Williamson’s description of theFaeroe Islands 50 years ago, with wind-dried birds and mutton (roest kjøt) kept inwooden-slatted hjallur.[126]

Conclusion: interdependence within the chiefdom

The St Kildans should have been able to develop a broadly-based and sustainableeconomy, whose products included relatively scarce, valuable resources which were wellsuited to the redistributive character of a chiefdom. It was evidently well worth theMacLeods’ time and effort to send a tribute-fetching retinue every year, long aftersorning had become illegal, and to repopulate Hirta after the 1727 smallpox epidemicand apparently also in the seventeenth century.[127] Despite Hirta’s remoteness (and itwas not a ‘stepping-stone’ island like Fair Isle) any temptation to abandon it wasevidently resisted. In any case, Martin tells us enough, I believe, for St Kilda to beconvincingly reconstructed as a self-managing (though not independent) communityand a valued component of the MacLeod chiefdom.

Interesting comparisons may be made with another domain within the MacLeodchiefdom. The isle of Pabbay, just beyond the western edge of the Sound of Harris,midway between Harris and North Uist, has almost exactly the same surface area asHirta. It has a good range of archaeological sites and monuments—a dun, a Pictishsymbol stone, cross-slabs, and the ruins of two churches.[128] Pabbay was clearly animportant component of the MacLeod chiefdom, being frequently mentioned in Grant’s

195EARLY HISTORY OF ST KILDA

history of the MacLeods and described in the 1790s as “once the granary of Harris”.[129]

In the early sixteenth century, it was described as “ane maist profitable Ile . . . plentifullof beir, girsing and fisching”. A later sixteenth-century report described Pabbay andHirta as each paying “60 bolls victuall”.[130] If a boll weighed a little over 156 lbs, 60bolls represents about 4.25 tonnes, or 21.25 kg per head for a population of 200.[131]

These late sixteenth-century figures are comparable with the 1793 figure for Hirta of43 bolls of barley paid by a population which numbered about 87 in 1795; in otherwords, about 35 kg per head.[132] Macaulay, writing in 1764, gave a figure of 50 bollsper year.[133] According to Martin, yields of barley were 16- to 20-fold[134] and there issome reason to believe that a high proportion of the crop went to pay the ‘rent’.[135] Itlooks as if Hirta, then, was a high input/high output zone for barley production, alongwith Pabbay and also, apparently, Berneray and parts of South Uist.[136] With such highyields, storage and distribution would be important considerations, and it would notbe surprising to find that these places were targetted by predatory chiefs.

Much of Pabbay’s cultivable land is exposed to the Atlantic westerlies, as, of course,are the machair lands of the Western Isles. In terms of its vulnerability to climaticchange or population crisis, Pabbay seems no better off than Hirta. Perhaps at sometimes of the year grain could be imported more easily to Pabbay than to Hirta but onthe other hand, if crops failed on Pabbay they would probably fail in other parts ofthe MacLeod chiefdom. At least the St Kildans had stores of eggs and dried meat closeat hand, under their own control. And if worsening storms and sea-spray were a seriousregional problem in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Hirta waslargely immune to the coastal erosion and massive sandblows which were affectingmany of the more productive parts of the Long Island.[137] Writing about Pabbay,Groome put it succinctly: “it formerly grew very fine crops of corn, but it has in agreat degree been rendered barren and desolate. Sand-drift has overwhelmed its SEside; the spray from the Atlantic almost totally prevents vegetation in the NW”.[138]

It is at least arguable, then, that the homeland of the MacLeod subchief was actuallyless productive than the distant island group to which he brought his retinue everyyear, especially if one takes the harvest of sea-birds and their eggs into account, andthe product of the island sheep pastures of Soay and Boreray. The relationship ofinterdependence was clearly complex, and may have been quite well reflected by therole-playing which apparently formed part of the transactions between the sub-chiefand the St Kildans. In their geographical situation, the St Kildans were vulnerable topredation by the retinue, but they also needed it to supply certain commodities whichthey were otherwise normally unable to obtain. They were forced to supply the retinueat levels which made it worth the latter’s while to return each year and re-invest in theSt Kildan economy, for example by replacing the islanders’ boat from time to time.But given the comparisons made between Hirta and Pabbay (itself apparently one ofthe more productive parts of what may be termed Greater Harris) one could turn theequation round, and argue that the MacLeods really did need the product of the StKilda archipelago to supplement the clan’s food supplies, and/or to take part in moresocially and politically ambitious prestations. From the chiefdom’s point of view,investment in the economy of St Kilda was worthwhile. The St Kildans, for their part,had no problem in attracting the small external contribution which their economyneeded. Of course, these relationships must have been partly masked and mediated bythe ideology of the clan. It would be interesting to know how far they can be projectedbackwards in time and how many other, different scenarios might be envisaged for thelong-term maintenance of comparable island communities.[139]

I have argued that in many respects the culture of Hirta was not unusual. The

196 A. FLEMING

similarities recorded by Martin between Hirta and other north-east Atlantic communitiesmust be of absorbing interest to archaeologists and historical geographers, sup-plementing and tending to confirm the rather coarse-grained evidence of monumentsand material culture on which we base the assumption that this was a fairly uniformcultural province. In their daily lives, the men and women of Hirta took more risksthan most as individuals, but the long-term dangers to which their community wasexposed were no greater than those faced by many Hebridean communities. It doesnot seem likely that St Kilda was more ‘marginal’ than other component parts of theMcLeod chiefdom. The archipelago was probably better buffered against the risk ofsubsistence failure than many of its neighbours. Access to stores of dried sea-birds,dried mutton and eggs, the opportunities for sealing, and the secure and interdependentrole of Hirta within the MacLeod chiefdom may have helped the St Kildans, with theircarefully-regulated economic system, to cope with short-term crises better than manyof their neighbours. In the long term, the risks which the St Kilda community ran weremore likely to have been genetic and epidemiological, and even in these areas we shouldnot necessarily assume that the St Kildans were more exposed than their neighboursin the Long Island. In any case such risks are better understood from a historian’s oran ecologist’s perspective than by members of communities which will eventually haveto face them.

I have also argued that the St Kilda archipelago had characteristics which at certainperiods at least allowed its people to be relatively successful and prosperous by regionalstandards. It is my contention that the history of St Kilda should be viewed within acontext of regional interdependence, rather than in the timeworn terms of ‘isolation’and ‘marginality’. This is not to say that St Kilda’s history can be regarded simply asthat of a small component of a late-surviving Scottish chiefdom, just a special case ofa special case of an anthropologically-recognized phenomenon. On the contrary, as Ihope has been demonstrated, the history of the archipelago in itself is of absorbinginterest.

Department of ArchaeologyUniversity of WalesLampeterCeredigion SA48 7EDWales

AcknowledgementsThis article is a by-product of the St Kilda Stone Implements Project, which is supportedfinancially and in other ways by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, the National Trust forScotland, and the Departments of Archaeology at the University of Wales, Lampeter and theUniversity of Sheffield. I thank Mark Edmonds and Alex Woolf for discussing some of theseideas, Ian Fraser and Richard Phillips for bibliographical help, and two anonymous referees forhelpful comments.

Notes[1] Expert commentary has been provided by A. B. Taylor, The name ‘St Kilda’, Scottish

Studies 13 (1969) 145–58 and R. Coates, The Place-Names of St Kilda (Lampeter 1991).Taylor argues that the name ‘Skildar’ or ‘Skilder’, originally applied to the ‘shield-shaped’islands of Gaskeir or Haskeir Eagach, was marked on sixteenth-and seventeenth-centurymaps, and then understood to refer to Hirt or Hirta; Martin’s use of the name ‘St Kilda’was highly influential in spreading its use.

197EARLY HISTORY OF ST KILDA

[2] According to Taylor, op. cit., the names Hirt and Hirta derive from Old Norse hjortr,meaning ‘stags’, which supposedly refers to the islands’ appearance in profile.

[3] T. Steel, The Life and Death of St Kilda (Edinburgh 1965); C. Maclean, Island on the Edgeof the World (Edinburgh 1972); M. Harman, An Isle called Hirte (Waternish, Isle of Skye1997).

[4] The earliest reference to Hirtir occurs in a thirteenth-century Icelandic saga, linking thearchipelago to events which took place in 1202; see A. B. Taylor, The Norsemen in StKilda, Saga Book of the Viking Society 17 (1967–8) 116–44, and W. Sayers, Spiritualnavigation in the western sea: Sturlunga saga and Adomnan’s Hinba, Scripta Islandica 44(1993) 30–42.

[5] K. Macaulay, The History of St Kilda (Edinburgh 1974, facsimile of 1764 edition) 197–8.[6] R. Coates, op. cit., 5.[7] R. A. Dodgshon, Modelling chiefdoms in the Scottish Highlands and Islands prior to the

’45, in B. Arnold and D. B. Gibson (Eds) Celtic Chiefdom, Celtic State (Cambridge 1993)99–109.

[8] S. Lee (Ed.), Dictionary of National Biography (London 1893) 289.[9] M. Martin, A Voyage to St Kilda (Edinburgh 1986, facsimile of 1753 edition, originally

published 1698), hereinafter VSK.[10] There is an extensive bibliography in Harman, op. cit.[11] M. Martin, A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland (Edinburgh 1981, facsimile of

1716 edition, originally published 1703) 284, hereinafter WI.[12] VSK 44; WI 295.[13] WI 287.[14] The beach is mentioned for Harris and North Uist (WI 52, 79). In Lewis and on North

Uist, women also rode in the cavalcade (WI 30, 79). A special cake was involved on Eriskayand at Eoligarry (north Barra) (WI 89, 100). There were also cavalcades on Tiree and Coll(WI 270, 271). The most complete account exists for North Uist (WI 79–80), where thecavalcade involved racing for prizes, with no harness except “two small ropes made ofbent . . . The men have their sweethearts behind them on horseback, and give and receivemutual presents . . . the women receiving knives and purses, the men fine garters and wildcarrots.”

[15] VSK 43.[16] Macaulay, op. cit. 86–8.[17] Ibid. 88–9[18] VSK 16–7; WI passim.[19] VSK 26; WI 25.[20] VSK 58; WI 56, 94.[21] The St Kildan harrow was “of wood as are the teeth in the front also, and all the rest

supplied only with long tangles of sea-ware tied to the harrow by the small ends; the rootshanging loose behind, scatter the clods broken by the wooden teeth; this they are forcedto use for want of wood” (VSK 18). The Lewis harrow had wooden teeth in the front tworows and “rough heath” in the third row (WI 3).

[22] VSK 37.[23] WI 38, 47, 63, 72.[24] For example, WI 106–7, 171.[25] VSK 58; WI 299.[26] VSK 49.[27] VSK 52 and passim.[28] VSK 63.[29] VSK 20. Martin refers to Stac Biorach as Stac Dona. See Harman, op. cit. 24.[30] VSK 23[31] VSK 22, 24, 25.[32] VSK 36, 59, 25.[33] VSK 59.[34] G. Stell and M. Harman, Buildings of St Kilda (Edinburgh 1988) 29.[35] Sir R. Moray, A description of the island Hirta, Transactions of the Royal Society 12 (1678)

929.[36] R. W. Munro (Ed.), Monro’s Western Isles of Scotland and Genealogies of the Clans

(Edinburgh 1961) 78.

198 A. FLEMING

[37] Martin (WI 94, 96) gave accounts of fowling on Berneray (to the south of Barra) and ofclimbers ascending the rock of Linmull (Mingulay) with the assistance of ropes, the climbbeing lead by the gingich. Gannets were taken from Ailsa Craig (WI 227–8). Martin alsorefers to dangerous fowling exploits involving ropes and a “cradle” at Noss (Shetland) andalso on Foula (WI 375–6). The most absorbing account is of the summer visit by fowlersfrom Lewis to the Flannan Isles (WI 16–19). The enterprise involved numerous taboos,rituals and ‘superstitions’—“punctilios” as Martin called them. On arrival, the fowlerswalked sunways round the island, bare-headed. On no account must they defecate anywherenear their boat, nor kill a bird with a stone or after evening prayers. They prayed, bare-headed, at the old chapel. They were not to speak the name of the Flannan Isles, andHirta had to be called ‘the high country’.

[38] VSK 63.[39] VSK 62; WI 299.[40] A. Buchan, A Description of St Kilda (Aberdeen 1974; facsimile of 1752 edition; originally

published 1727) 36–7.[41] VSK 42; WI 287.[42] VSK 43, 44.[43] I. F. Grant, The MacLeods: The History of a Clan 1200–1956 (London 1959) 358.[44] Dodgshon, op. cit., fig. 11. 1[45] WI 48.[46] VSK 10, 44–5; WI 289–90.[47] VSK 48.[48] Martin suggests a population of 180 in some places and 200 elsewhere. See VSK 51; WI

284.[49] A. Fleming, The changing commons: the case of Swaledale (England), in A. Gilman and

R. Hunt (Eds) Property in Economic Context (Lanham and Oxford 1999).[50] VSK 18; Moray, op. cit. 928.[51] VSK 44.[52] VSK 17; WI 295.[53] Harman, op. cit. 124–6 quotes recorded figures of 27 (Martin), 30, or 33 (Buchan) for the

pre-smallpox period[54] WI 295.[55] VSK 59.[56] B. Nelson, The Gannet (Berkhamsted 1978) 286.[57] VSK 60–1.[58] WI 295.[59] VSK 18.[60] Macaulay, op. cit. 40, 186.[61] Moray, op. cit. 928.[62] VSK 53.[63] VSK 59.[64] VSK 50.[65] VSK 54.[66] D. A. Quine, St Kilda Portraits (Ambleside 1988) 152.[67] VSK 49; WI 99.[68] VSK 52.[69] VSK 51–2.[70] VSK 53.[71] VSK 44–5.[72] Quine, op. cit. 139.[73] On North Rona, for example, hospitality involved each man killing a sheep (“being in all

five, answerable to the number of their families”); on Berneray (or Barra?), each familytook in one guest (WI 22, 95). When Martin’s party arrived on Hirta, “the inhabitants . . .by concert agreed upon a daily maintenance allowance for us, as bread, butter, cheese,mutton, fowls, eggs, fire etc. all of which was to be given in at our lodging twice everyday; this was done in a most regular manner, each family by turns paying their quotaproportionately to their lands; I remember the allowance for each man per diem, beside abarley cake, was eighteen of the eggs laid by the fowl called by them lavy, and a greaternumber of the lesser eggs, as they differed in proportion” (VSK 10). On North Rona (WI

199EARLY HISTORY OF ST KILDA

22) “they are very precise in the manner of property among themselves; for none of themwill by any means allow his neighbour to fish within his property”. On St Kilda (WI 291),on the other hand: “one will not allow his neighbour to sit and fish on his seat”. Thereare references to shared maintenance of community officials in relation to the isles southof Barra (WI 99).

[74] Munro, op. cit. 78.[75] VSK 48.[76] WI 290.[77] VSK 50–1.[78] VSK 57.[79] WI 293.[80] Harman, op. cit. 269.[81] Harman, op. cit. 194. If one takes the written sources literally, the horses must also have

been replaced after Coll MacDonald’s raid of 1615, although as Harman points out (ibid.84) the source which claims that “all the bestiall” were killed on that occasion is likely tohave been exaggerating.

[82] WI 285–6[83] WI 290[84] VSK 49, 51[85] VSK 46–7[86] Moray, op. cit. 929.[87] J. B. Mackenzie, Episode in the Life of Rev. Neil Mackenzie at St Kilda from 1829 to 1843

(privately printed 1911) 30.[88] According to Martin, the seventeenth-century St Kildans were “nice in examining the

degrees of consanguinity before marriage”. See VSK 38.[89] VSK 50.[90] VSK 66.[91] Mackenzie, op. cit. 21.[92] This image has been widely reproduced, perhaps most influentially in T. Steel, op. cit.[93] R. Connell, St Kilda and the St Kildians (London 1887) 148.[94] Dodgshon, op. cit. fig. 11. 1.[95] Ibid.[96] Grant, op. cit. 211, 236.[97] W. R. Mackay, Early St Kilda: a reconsideration, West Highland Notes and Queries 27

(1985) 17–21.[98] Harman, op. cit. 128.[99] Harman (ibid. 262) points out that Martin, despite his interest in medicine, does not

mention infantile tetanus, but Macaulay (who visited Hirta in 1758) does. This leads herto argue that the bacillus probably arrived sometime in the first half of the 18th century,perhaps during the re-population after the 1727 smallpox epidemic, and (ibid. 129) that itwas primarily responsible for the stability of population numbers from the mid-eighteenthto mid-nineteenth centuries.

[100] E. J. Clegg, Population changes in St Kilda during the 19th and 20th centuries, Journal ofBiosocial Science 9 (1977) fig. 2.

[101] Harman, op. cit. 126, 128.[102] Ibid. 128.[103] S. Angus and M. M. Elliott, Erosion in Scottish machair with particular reference to the

Outer Hebrides, in R. W. G. Carter, T. G. Curtis and M. J. Sheehy (Eds), Coastal Dunes:Geomorphology, Ecology and Management for Conservation (Rotterdam 1992) 93–112.

[104] M. J. C. Walker, A pollen diagram from St Kilda, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, New Phytologist97 (1984) 99–113.

[105] Munro, op. cit. 78.[106] VSK 48.[107] Clegg, op. cit. table 1.[108] Fleming, op. cit.[109] VSK 18.[110] Macaulay, op. cit. 29–30, 33–4, 196.[111] J. M. Boyd and I. L. Boyd, The Hebrides: A Natural History (London 1990) fig 26.[112] Ibid. table 11. 1

200 A. FLEMING

[113] Nelson, op. cit. 279.[114] D. Serjeantson, Archaeological and ethnographic evidence for seabird exploitation in

Scotland, Archaeozoologia II/1.2 (1988) 209–24.[115] Boyd and Boyd, op. cit. table 11. 1.[116] VSK 31[117] Boyd and Boyd, op. cit. fig. 28. There is apparently no statistical information for the

common seal.[118] Munro, op. cit. 78.[119] G. Buchanan, Historia Rerum Scoticarum (Aberdeen 1762) 78.[120] Moray, op. cit. 928.[121] R. N. Campbell, St Kilda and its sheep, in P. A. Jewell, C. Milner and J. M. Boyd (Eds)

Island Survivors: The Ecology of the Soay Sheep of St Kilda (London 1974) 25.[122] Nelson, op. cit. 94–5.[123] Ibid. 89, 147.[124] Ibid. 142–3.[125] Munro, op. cit. 78; Buchanan, op. cit. 25.[126] K. Williamson, The Atlantic Islands (London 1948) 29–31.[127] Harman, op. cit. 126, 128.[128] Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, Inventory of

Monuments and Constructions in the Outer Hebrides, Skye and the Small Isles (Edinburgh1928) 30–1, 39, 45, 126 plus figs 93 and 175.

[129] Grant, op. cit. passim; J. Sinclair (Ed.), The Statistical Account of Scotland 1791–99(Wakefield 1983) 51.

[130] Munro, op. cit. 79; Anon (1577–95) in W. F. Skene (Ed.), Celtic Scotland: a history ofancient Albion (Edinburgh 1890) 431.

[131] According to R. C. MacLeod of MacLeod, The Island Clans during Six Centuries (Invernessc. 1930) 139.

[132] Harman, op. cit. 100, 125.[133] Macaulay, op. cit. 38.[134] VSK 18.[135] Harman, op. cit. 99, 199.[136] I. F. Grant, Highland Folk Ways (London 1961) 94.[137] Angus and Elliott, op. cit.[138] F. H. Groome, Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland (Edinburgh 1884) 147.[139] According to Canon R. C. MacLeod of MacLeod, The MacLeods of Dunvegan (Edinburgh

1927) 1: “there can be no doubt that Leod flourished at some period in the thirteenthcentury” and “it is almost certain that Leod was born about the year 1200”. In TheMacLeods: Their History and Traditions (Edinburgh 1928) the same author acknowledgedthe existence of a debate over whether Leod was ‘Norwegian’ or ‘Celtic’.