How to make money from cooking gas

Transcript of How to make money from cooking gas

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

1/32

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

2/32

NLNG - The Magazine2

From

theEditor-in-C

hief

CONTENLNG - The Magazine is the corporate magazine of Nigeria LNG Limited.The views and opinions within the magazine however do not neessarily reflect those of the Nige-ria LNG Limited or its management.Editor-in-Chief: Siene Allwell-BrownManaging Editor: Ifeanyi MbanefoDeputy Managing Editor: Mohammed Al-Sharji

Editor: Yemi Adeyemi

Deputy Editor: Elkanah Chawai

Writers: Eva Ben-Wari, Ophilia-Tammy Aduura, Anne-Marie Palmer-Ikuku, Dan Daniel

All Correspondence to:Yemi Adeyemi, Editor, NLNG The Magazine, Nigeria Limited, C & C

Building, Plot 1684, Sanusi Fafunwa Street, Victoria Island, PMB 12774, Lagos, Nigeria.

Phones 234 1 2624190-4, 2624556-60. e-mail: [email protected], www.nigerialng.com

Editorial consultancy, design and production: Magenta Consulting Limited, 1 Joel Ogunnaike Str.,

GRA, Ikeja, Lagos. Tel: 234 1 7360830, 234 1 07023236001.

e-mail: [email protected], web http: //www.magentaconsult.com

Ibeneche Olinma

You are already conversant with newspaper headlines on NigeriaLNG Limited: Nigerias world class company, Supplier of 10% ofworlds LNG demand, Owner of one of worlds largest dedicatedLNG fleet, Fastest growing LNG project in the world Nigeriascash cow, NLNG wins award for 50 million man-hours with nolost time injury, etc.What you may not be so familiar with is the story behind theheadlines. Why? I will limit myself to three reasons: The reporterscreed that bad news is good news, a creed that makes them give alot more space and newsprint to bad news, to the detriment oasisof good news like us.The second part reason is that by the very nature of their business,reporters write history in a hurry and most times paint picturesonly in broad strokes (please read headlines, and sound bites)missing the fine details.The third is that we usually try not to blow our trumpet.But the question persists: why is Nigeria LNG Limited such a greatcompany; why is it so much in the news for good and some say,

great things. We are not ready to divulge all our trade secrets, butwe have decided to give you, our esteemed reader, a sneak view.Nigeria LNG Limited has become a corporate citizen. Like citizensin the classical sense, NLNG has cultivated a broad view of its ownself-interest, while instinctively searching for ways to align thisself-interest with the larger good. We try, at all times, to reconcileour profit-making strategies with the welfare of society, and tosearch for ways to steer all parts of the company on a sociallyengaged course.This paradigm enables us to play a leadership role in social problemsolving by funding long-term initiatives, such as stabilizing ofdomestic cooking gas market, sponsorship of literature and scienceprizes, scholarship for students in tertiary institutions, nationalautism awareness campaign, provision of power, water and roads inour host communities.In NLNG we back philanthropic initiatives with corporate muscle.And in addition to cash, we make available to Nigeria managerialadvice, technological and communications support, and teams ofemployee volunteers. And we are funding these initiatives not onlyfrom philanthropy budgets, but also from business units, such asmarketing and Public Relations, community relations, shipping, etc.We recently organised training for PPMC on scheduling andterminal management and we are helping the regulatory agencyfor shipping, NIMASA, update its shipping register, so that thecountrys register would gain quality and worldwide acceptance.In doing these, we are forming strategic alliances with nonprofitsand government agencies and emerging as an important (I prefer,indispensible) partner in movements for social change, whileadvancing our business goals.I know what you are thinking! This must be corporatespeak,designed to bamboozle. No its not. And I warn that its only a tipof the iceberg. We are indeed and in fact a good, great corporatecitizen. And to prove it, we invite you to turn the pages and as

they say, kick the tyres of our corporate reputation.

Compliments of the season.

Siene ALLWELL-BROWN

and

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

3/32

NLNG - The Magazine 3

Opindi

NTS

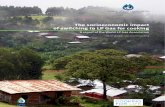

Cover Cylinder picture culled from Magenta Consultings archive.

Opportunities in Nigerias cooking gas industry .................................. 4

A transformation in cooking gas industry ........................................... 6

Our Mission: Availability, Affordability ................................................. 12

We need more jetties, storage facilities .............................................. 19

Cylinders, the next frontier ................................................................ 22

Upfront investments needed in LPG market ........................................ 27

Photos

GAN 2010 in Photos ........................................................................... 15

NLNG tours Nipco, Navgas facilities .................................................... 31

Erinne Ekundayo

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

4/32

4 NLNG - The Magazine

Business men in the cookinggas (Liquefied Petroleum Gas,LPG) industry say it out loud

whenever they get the chancethat LPG business is tough inNigeria. But it doesnt changethe fact that the industry is apotential N37 billion industrywith a 50% rate of return oninvestment, according to amarket research report in2010.A guaranteed supply of150,000 metric tonnes of LPG

(cooking gas) by Nigeria LNGLimited (NLNG) began thetransformation of this industryto help it reach its potential,solving a supply challenge atthe time. However, a supplyof 150,000 metric tonnesbrought with it new challenges

and opportunities.

The past...

In the 1980s and 1990s, Nigeriansconsumed over a hundred metric tonnes ofLPG and then the figures began to go down.The four refineries in the country were

desultory and could not supply the marketwith a combined installed LPG capacity of360, 000 metric tonnes. The effects of thisspiralled down to other things: wastage of

primary and secondary storage capacityof about 37, 000 metric tonnes. The 12storage tanks built and owned by theNigerian National Petroleum Corporation[NNPC] were a hopeless situation forLPG at the only functioning artery ofpetroleum products in the country, theNOJ Jetty at Apapa; an abandoned jetty inCalabar; corroded and decrepit cylinders;deteriorating infrastructure; over 300non-functioning filling plants; downturnin business in supply chain; dwindlinginvestments; all time high of LPG price;and an increase in the use of kerosene

and firewood, endangering health and theenvironment.

This situation left in its wake thedereliction of facilities used for thesupply of LPG to a nonetheless growingpopulation, making it a bourgeois affair touse LPG as cooking fuel. The industry losta major part of its market.

In September 2006, the Board of NigeriaLNG, worried about the adversity fromthe scarcity of LPG in the midst plentygas, decided to revive the LPG market

and reduce the dependence on firewoodfuels for cooking by majority of Nigerians.The decision was the beginning of afierce confrontation with infrastructuralchallenges that beset the industry.

- YEMI ADEYEMI & ELKANAH CHAWAI

A major challenge was the NOJ jetty inApapa which was over-burdened with themass importation of petroleum products.Unfortunately for the LPG businesses, LPG

was down the perking order of petroleumproducts that could run down the storagetanks owned by the Petroleum ProductsMarketing Company (PPMC). It was the caseof inertia in Calabar where the second jettysat. In addition to the daunting challenges,the low draught at the jetty didnt makeit possible for very large vessels to berth,the kind that would uplift from the Bonnyterminal where NLNG exports gas. Andso a major town hall meeting in 2006 wasorganised by the company to forge a wayout of the quagmire. This led to a dedicationof 150, 000 metric tonnes annually by the

NLNG Board, selection of six lifters (off-takers) and an ingenious idea of a Ship-to-Ship (STS) supply of LPG to the domesticmarket on a Free-on-board basis (FOB). Theproject, christened Domestic LPG (DLPG)by NLNG, involved lifting gas from Bonnyon board a mother vessel; processing thegas for domestic consumption on the vessel;transfer of gas to a smaller ship called theShuttle Vessel; and discharge at the jetty in

Apapa. It was a brilliant idea.

NLNG picked part of the cost for the mothervessel with a commitment from the lifters

that they will invest on infrastructuraldevelopment to make robust the supplychain.

Opportunities

in Nigerias cookinggas industry

F O R E W O R D

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

5/32

NLNG - The Magazine 5

The Present...With as little as 150, 000 metric tonnes,the market began to open up. Even thoughconsumption per capita remained low atabout 0.5 kilograms per capita (Ghana is 3kgper capita while Morroco is 44.40) and themarket could only take about 60, 000 metrictonnes from NLNG annually, the marketcommenced with a slow awakening.To start with, the offtakers came togetherto surmount operational problems andinfrastructural challenges. That includedchartering the shuttle ship and using thePPMC facility in Apapa together. They alsocontributed enormously to bring back to life

the PPMC terminal and improve load-out.With more LPG into the terminal, comatosefilling and bottling plants sprang to life toabsorb the new surge of energy that hadmade taut the arteries of supply. Moretrucks shuttled between the PPMC terminaland filling plants. The price of cooking gascylinder dropped from N7, 000 to N2, 500.To quote the president of the NigerianLiquefied Petroleum Gas Association, Alhaji

Auwalu Ilu, in a newspaper report thecountry consumes 70,000MT per annumand we have about 130 LPG plants and7,000 retailing outlets. These numbers only

grew with guaranteed supply.

NLNGs contribution of about 80% to LPGsupplies led to millions of dollars spent tomove the volume to consumers.

Consider this fact: NLNG spent over $7million a year on the supply vessel; moreupstream players are investing in gasprocessing plants and more gas producersare coming into the game; more investmentsin through-put facilities, for example, Navgasfacility costing $50 million; Nipco worth N7billion and millions of dollars of off-takers

investments in the development of theirsupply chain.

As part of plans to develop a formidablechain of supply, many of the off-takersinvested in cylinders; not only revitalisingthe market with new cylinders, but bringingsmaller cylinders as a palliative to those

who could not afford the popular 12.5 kgcylinders. The initial entry investment (thecost of cylinders, stove and accessories)reduced. Currently, more offtakersare participating in the DLPG and theprogramme is beginning another cycle ofcontract with these offtakers. The increasingdemand for LPG outgrew the STS model ofsupply gas to the domestic market. Some ofthe initiatives materialised in the state-of-

F O R E W O R D

the-art automated Navgas facility with acoastal storage capacity of 8, 000 metrictonnes (see interview with James Opindi)and a terminal to lift and load ships at thesame time. Another positive development

was the partnership between PPMC andSahara Group to operate a 1000 metrictonnes LPG depot in Calabar Nigeria. It isbeing upgraded to a 2500 metric tonnesfacility.

With pleasant developments like these,Nigeria LNG raised its game to deliver gason Delivered Ex-Ship (DES) with a new

More volumes would mean need for morecoastal storages (see interview with Dr

John Erinne). This bit is capital intensivenevertheless necessary. These storages, withdedicated terminals, will increase capacityfor lifters to be able to bring LPG onshoreand distribute to inland storages and fillingplants. They become fundamental part ofa robust LPG circulation system. Droppinga notch down the value chain are inlandstorages (storage tanks) that will ensureconsistent supply in the regions across thecountry.

Further down the chain are filling plants.

According to Alhaji Ilu, a consumption levelup to 750,000 metric tonnes per annum willtranslate into 250 LPG plants and 74,970retailing outlets . There are remarkablepossibilities here. Some people have alreadyintroduced mobile filling plants (distribution

vans) that can take LPG to end-usersdoorsteps, make it more accessible. There isneed for more of such initiative.

Another link in the chain is trucks. Thetrucks transport LPG from coastal storagesand/or inland storages to filling plants.Setting up a truck company would be good

business. Presently, the market is beingunderserved with an estimate of 150 trucks.The market needs about 2,000 trucks (seeinterview with Felix Ekundayo).

Every link is important. However, the mostcritical are the cylinders. Cylinders bringLPG to homes from all the storages andfilling plants and therefore sacrosanct to thedevelopment of the market. A shortage ofcylinders translates into inaccessibility; andthat and other safety issues arising from thecirculation of decrepit cylinders accounts forthe slow growth in the market. Investments

are needed in the manufacturing of cylinderseither by way of importation of cylindersor better still, the importation of steelplates for cylinder manufacturing in thecountry. This is an investment area requiringinvestors attention. Cylinder refurbishingplants, cylinder assessories manufacturingplants can be set up that will also stimulateindustrial and commercial activities in themarket. Finding a way out of the initial entryinvestment gridlock can open a vista ofopportunities in manufacturing, distributionand warehousing.

A lot needs to be done in the industry and itneeds all stakeholdersprivate enterprisesand governmentto tighten the knots andmake this drooping arm of the oil and gasindustry a haven.

Cylinders bring LPG

to homes from all thestorages and filling plantsand therefore sacrosanctto the development ofthe market. A shortage ofcylinders translates intoinaccessibility; and that andother safety issues arisingfrom the circulation ofdecrepit cylinders accounts

for the slow growth in themarket.

vessel that will lift directly from Bonny anddeliver directly to terminals and coastalstorages like those in Lagos and Calabar,thus cutting out a major cost of chartering ashuttle vessel and making the supply of gasto the domestic market more efficient. Thenew model will kick off in the new contractstarting in 2011.

Yet, the extant supplies only cater for a

fraction of 150 million Nigerians.

The future (challenges-turned-

opportunities)In the Nigerian population lies a goldmine.

Another 150,000 metric tonnes to bededicated by NLNG and more volumes fromthe convalescing refineries will push thesupply volumes up in the coming five yearsbut the extant challenges will become moreprofound.These challenges can become opportunitiesfor investments; gateways for investors intoan undermined industry and a long term

plan to accommodate future growth indemand. It is a myriad of opportunities downthe value chain of the LPG market.

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

6/32

NLNG - The Magazine6

What exactly was the objective of

NLNGs intervention from the

beginning?Nigeria LNG went into the supply of cookinggas (LPG) to the domestic market primarilyto help remove an absurdity that actuallyexists in Nigeria. In 2007, it was clear thatNigerias consumption of cooking gas hadbeen declining over the years even thoughthere were two strong producers of LPGin the country. Nigeria LNG and Mobil

were exporting the product. Chevron,also in Escravos, produces a mixture ofbutane and propane from which the typeof cooking gas we use can be extracted.

Whilst these companies were exportingthe product, there was persistent scarcityof the commodity in the Nigerian marketbecause local consumption was premised onthe effectiveness of the refineries. The LPG

production of the refineries was actually ata level that could satisfy local consumption,

even though we all know that the refinerieshave not been operating efficiently and thatis why we still import refined products.Given the situation, Nigeria LNG steppedin to guarantee availability of supply to thelocal market, irrespective of the state of therefineries. The aim is to try to salvage thistrend whereby we produce and export LPGin huge volumes, yet supply to the localmarket is inadequate. I think it was the rightdecision to get involved in supplying theproduct to the local market. We all know theimpact of deforestation that occurs whenpeople cook with firewood. We usuallysee very long queues for kerosene at thefuel stations. Considering the numberof generators in operation nationwide,importers of refined products probably find

it more attractive to import diesel than toimport kerosene. Scarcity of kerosene is also

heightened because the consumers competewith the airlines for the product. Overall,it makes sense to provide cooking gas in acountry that produces oil and gas.

How would you rate NLNGs

intervention?

I think it is very successful. People nowbelieve it is the responsibility of Nigeria LNGto supply LPG to the domestic market. Today,the availability of cooking gas in Nigeria isassociated with the work of Nigeria LNG,but that doesnt mean we are home anddry. Nigeria LNG has done what it set out todo; to guarantee availability at internationalcompetitive prices. What has been lackingin the value chain is the infrastructurethat would actually make delivery of LPG

I N T E R V I E W W I T H IBENECHE

A transformation incooking gas industry

Just two years after he took over the helm of affairs in Nigeria LNG Limited, ChimaIbeneche has become a household name in Oil and Gas industry in Nigeria. And for goodreason. Chima is one of those experts you can easily describe as analytical and insightful,competent and incisively focused. He has excelled in ground-breaking ventures in differentupstream projects which include a successful leadership at Shell Nigeria Exploration

and Production Company (SNEPCo), the company that pioneered offshore deepwaterexploration in Nigeria.It is also to his credit that the $13 billion Nigeria LNG Limited, the single largest privatesector investment in sub-Saharan Africa, remained profitable during the economicrecession.In this interview withYemi Adeyemi and Dan Daniel, he bares his mind on the NLNGgame plan in the LPG industry. Excerpts:

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

7/32

7NLNG - The Magazine

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

8/32

NLNG - The Magazine8

I N T E R V I E W W I T H IBENECHE

to end-users efficient and cost effective.For instance, all the LPG we supply to thedomestic market come in through Lagos.

At the Apapa Jetty where this is done,there are limited opportunities and storagefacilities to receive LPG. So right from thejetty, the product begins to add cost dueto demurrage, and beyond that, after theoff-take from the storage near the shore, theproduct has to be transported over land. Wedont have the good fortune of rail transport

which would have made land transportationcheaper. We dont have the good fortune totransport over good roads either. Imaginetransporting from here to Port Harcourt. Youhave to pass through Ore and everybodyknows the difficulty of getting through thatstretch of road. All these add to the cost ofdelivery to the end-user. In this case, theend-user cannot expect a drastic reductionin prices because there are so many chokepoints that add to the cost of logistics ofdelivery of the product. However, whatmakes Nigeria LNGs effort very successfulis the guarantee of product availability.This has encouraged investors to beginto invest in infrastructure. For instance,

NIPCO along with their partners, have builtadditional storage in Apapa, Lagos area. It isnow possible to have a lot more cooking gasavailable in storage in Lagos area. In recenttimes, investors from Port Harcourt areaare understudying how they can invest instorage and jetty facilities in that part of the

country to achieve the same result. Oandoand other companies are also buildingstorage facilities.

With LPG dispensing facilities mountedon skids, which can be affixed within thefour walls at the fuel stations, people canactually take their gas bottles there andobserve as they are filled in their presence.So, NLNG has created a mini revolution inthis sector of the business. In the past whenthere was no guarantee on the viability ofthe business, nobody could make a five-yearplan, but now we have given assurance that,if investors make a plan, even if its for fiveor 10 years, they are certain to have a supplyof LPG that would meet Nigerias demand.

Many of these developments you have

mentioned are in Lagos. What are the

plans to improve the supply chain and

prevent cost going up in other locations,

especially further up north?

Since our production is in Bonny, one wouldrequire, as a front line infrastructure, a jettyto transport the commodity to differentparts. That is why Lagos features primarily atthat level, while Port Harcourt and Calabar

feature at a secondary level. Following thejetties would be the storage facilities, andmost big storages will be near the shore.Going beyond that, what we require, really,

would be things such as tanker trucksto transfer the product from one point tothe other. Many companies have started

buying these tanker trucks. There are someinland storage facilities but there are nottoo many new developments and I think itis being hampered by the choke points atthe jetties. When the jetty choke pointsare unblocked, people can move furtherinland to begin to develop storage tanksinland. For me, the biggest improvementthat would help better distribution inland

would be the construction of railways. Ifwe could just put a tanker wagon behind atrain, it can take the product to Sokoto orto Kano without substantially increasing theprice of the product. Unfortunately, that isnot available now, so I dont envisage majordevelopments in inland storage. NNPC hadbuilt certain infrastructure through theirbutanization programme but then again they

were never put to good use because of lackof supplies. So, I think you will see a gradualimprovement of the development of facilitiesand infrastructure from the coast towardsthe inland which will of course depend onthe commercial viability of all the factors.

Last year, there were talks about

encouraging the development of private

jetties. Has there been any progress inthis regard?

All the new developments I know aboutare happening around Lagos. Again, it isconsistent with the fact that Lagos is thecommercial capital of Nigeria, so peoplecan leverage networks with other activitiesgoing on around them. There are one ortwo people developing jetties that areindependent of the NNPC jetty and as Imentioned, NIPCO has developed quite asignificant storage capacity, but not much ishappening in other parts of the country. Inthese cases, government should actually stepin either with incentives or policies to makepeople invest in the areas that are strategicto it.

It is often claimed that Nigeria LNG

supplies about 70 percent to 80 percent

of the LPG consumed domestically. Does

it mean other players such as Mobil and

Chevron are not playing on this scene?

You need to realize that like NigeriaLNG before December 2007, many ofthe facilities were built purposely forexport. I mentioned initially that domestic

supplies were premised on supplies fromthe refineries. These producers are stillexporting and I dont know whether theyhave taken a similar measure like NigeriaLNG to ensure that a certain percentage

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

9/32

NLNG - The Magazine 9

of their production is dedicated to thedomestic market. But to start with, thedemand of our product has not gonebeyond 60 percent of the quantity we haveguaranteed each year so why would Mobilor Chevron provide additional availability

when the one that Nigeria LNG has providedhas not been used up? The problem isnot with Mobil or Chevron providingadditional availability, rather, it is the lack ofinfrastructure to facilitate distribution of theproduct in-country. As a company, we haveborne some costs in making this available.Until the end of 2010, we had what we calla mother vessel which is actually a floatingstorage that acts as a terminal for lighter

vessels to come and off-take products andbring them to the jetty. We bore the cost ofthat. There is a sacrifice in doing that andunless there is actually full utility of theavailable quantities, it doesnt make sensefor another company to bear the sacrificesfor no value at all.

smaller distributors to buy from them. Atthat time, it would become a self- sustainingbusiness like any other one.

Do you have other ideas or projections

on how long it might take to get there?

It is difficult to predict because it alldepends on the pace at which theinfrastructure develops. It depends also onhow the market consolidates into capablebig players. One can already think of thepossibility of businesses like Oando, NIPCOor African Petroleum concluding that thereis viable profit to be made from this businessso they can actually grow into that space

where they use their own ships to buy theproduct. The danger in going too fast isthat if it ends up too early being one entity,then you can also create a monopoly that

will erode the possibility of transferring theprice to the consumer at an acceptable level.It will be beautiful if two or three of thosebusinesses grow into that space. We will justhave to wait and see to conclude that thedomestic LPG business has matured. Untilthat happens, depending on Nigeria LNGBoards view, my recommendation as CEO

will be that we just continue what we aredoing to allow the market to mature becauseeven though we make sacrifices, I think it is

something worth doing for the benefit of theNigerian economy.

There are some

inland storagefacilities but thereare not too manynew developmentsand I think it is beinghampered by thechoke points at thejetties.

Where is NLNG going with this? Whats

the companys exit strategy?

Businesses are into making profit, but tomake profit you have to be a corporatecitizen of a place and if you are a citizen,

you have responsibilities. It is somethinglike cleaning your environment; you canleave your house in the morning withoutcutting the grass on your lawn but if youare a responsible citizen, you will keep

your environment clean. People term whatsome of these businesses do as corporatesocial responsibility, but some of these are

just the right thing to do as a citizen ofa place. Businesses are citizens; they arelegal citizens of the country and besides,the Nigerian Government owns 49 percent

of NLNG. I think it is in the interest of allthe shareholders and the company to try,once in a while, to solve a problem in their

neighborhood. That is why we get involvedin such ventures.

We would continuously monitor the LPGchain and when it becomes clear that wereally have no special value to add, we willreturn to our core business which is actuallyto export. We have changed the mode ofsupply and removed the mother vessel. Sothat reduces the cost of our being able tomeet our commitment. The mother vessel

was replaced with a lighter boat that cando a quick run between Apapa Jetty andCalabar. By the model we operate now, ifanybody has a jetty that meets the technicaland safety requirements that the shipcan call to, the person can buy LPG fromNigeria LNG and we would deliver at thatjetty. The more people join this mode ofoperation, the less the cost for everybodyand I think, ultimately, the plan would bethat people can actually buy from us onFree on Board (F.O.B) at our terminal as wedo for export. The reason it doesnt makesense to them now is that if you are buyingsmall quantities and we have several shipscoming, it increases the risks at the jetty.But eventually I think the market will mature

enough such that a few big distributors willbe able to hire their own ships and thenorder quantities, take it off from our jettyand then store it in their tank farm for other

I N T E R V I E W W I T H IBENECHE

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

10/32

NLNG - The Magazine10

I N T E R V I E W W I T H IBENECHE

What are the regulatory anomalies inthe industry? Are there regulations you

think government should put in place to

help the industry to grow?

It is good that you point out the anomalies.Its a very strange for people to import LPGand not pay Value Added Tax (VAT), whereasif you buy from local production, you pay

VAT. Its totally nonsensical and I have had achance to discuss this in certain fora. I think

we have to continue to say this. Hopefully,the Minister of Finance can convincehis colleagues to change the pattern. Imentioned that, so far, government hasbeen fairly quiet on policies to encourageLPG utilisation. I think that is unfortunatebecause desertification is a genuine danger.If people cant buy kerosene or cant buyLPG, they would use wood and I know thatthere is a fund that is set aside to fightdesertification; this would be one place toapply it, not to subsidise LPG because I dontthink subsidies make people rational in theireconomic behavior. Instead, the fund couldbe used to promote distribution. Specialfunds can be used, for instance, to createa jetty access in Port Harcourt as a matter

of urgency. That would have avoided theneed for LPG transported by sea to Lagosfrom Bonny and then carried by road backto Port Harcourta situation that shouldbe avoided immediately. If this happens, it

would mean that the landing price of LPGin Port Harcourt and Lagos would be aboutthe same. It would further reduce the costof LPG inland. So, something can be done,policy-wise, to improve the situation. It isa little investment and in one year or 18months, you could actually build a storage

We would continuously monitor the LPG chainand when it becomes clear that we reallyhave no special value to add, we will returnto our core business which is actually toexport. We have changed the mode of supplyand removed the mother vessel. So thatreduces the cost of our being able to meet ourcommitment. The mother vessel was replaced

with a lighter boat that can do a quick runbetween Apapa Jetty and Calabar.

tank farm and jetty which would also easethe burden on the distributors who canlease those facilities and use the capital theycan get from the bank to do other thingssuch as buying bottles, tanker trucks and,maybe, construct smaller inland storagefacilities. Without a coordinated policy,achieving success is difficult. I know that insome other places such as Indonesia, theyhave gone as far as subsidising the initialintroduction of cheap cookers and stoves sothat the population has enough demand forthe product. That also will mean a lot to thedistributors because if the volume is high,

you can afford to take a very small margin.But if the volume is small, you have to takea higher margin. This means if the initialintroduction can be helped by policy, then it

will make all these things go very well.

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

11/32

NLNG - The Magazine 11

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

12/32

NLNG - The Magazine12

I N T E R V I E W W I T H OLINMA

How did domestic LPG supply start forNLNG?The issue was first raised at the NLNGBoard. We were exporting a lot of gas atthat time and there wasnt any part of thatgas going into the domestic market. It wasdecided that NLNG should intervene indomestic LPG supply. Prior to that time,supply of LPG into the domestic market wasmainly from the refineries, supplementedby import. But then supplies from refineriesbecame irregular with regular shut downof the refineries which led to the bulkimportation of LPG consumed in theCountry. And in 2007, the interventionstarted.

When the intervention was planned,criteria were set for lifters (off-takers)and six were picked. Was it a deliberatedesign to pick six offtakers?No, it was not. What we did was to have atown hall meeting where we invited all thestakeholders. We had said at that time that

the whole idea behind the intervention wasto make sure the product is available forthe end-user to buy at a reasonable price.For that reason, we wanted lifters who hada full chain. If we have operators who havea complete chain, we can monitor whatthey do. That was one of the key criteria forselecting the six lifters. There were some bigplayers who didnt participate despite ourinvitation. Maybe they didnt believe that it

would work, but subsequently, we have hada number of new lifters. At the moment, wehave about 10 lifters and we are registeringmore. Once a company meets the criteria,the company is registered as a lifter. It isnot an exclusive club. We just wanted tostart with a pilot team to make sure that thesubsidy we were putting in got to the end-users. We are managing to achieve that.

The initial contract ended in September2010. Is the model of lifting LPG goingto be revised?

After three years of operations, we looked

at the model and looked at areas forimprovement so that we can cut cost anddrive the price of LPG further down. Welooked at the fact that we had double costsin the mother vessel and the shuttle vesselprocedure. We wanted to cut out the costof one of the vessels and we realised that

we could do away with the shuttle vessel.The problem was that the mother vessel

was too big to unload at the NOJ terminal.We therefore decided to get a smaller vesselwhich can go to load LPG in Bonny and godirectly to the unloading terminals to deliverfor the lifters, rather than do a ship-to-shiptransfer at sea. We currently have a smallermother vessel, about 15,000 metric tonnes,

which can unload directly to Navgas andNOJ terminals. That results in a saving ofabout $100 per tonne. For that reason, wenow sell the LPG on a Delivery Ex-Ship(DES) basis using our vessel to deliver theproduct rather than the previous model ofFree on Board ex Mother Vessel.

Patrick Olinma,General Manager for Commercial at NLNG is a soft spoken,brilliant lawyer and gentle man of the oil and gas industry.

As a principled and practical manager, Mr. Olinma combines cutting edgeindustry practices with innovation and a deep knowledge of the industry to

give NLNG its incisiveness in commercial activities. His role as a member of themanagement team in helping to stir the company out of stormy waters duringthe economic recession in 2009 and 2010 is proof enough.In this interview withYemi Adeyemi and Elkanah Chawai, Mr. Olinmaoutlays NLNGs role in the LPG industry and the future of DLPG programme.

Our mission:

availability,affordability

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

13/32

NLNG - The Magazine 13

Has the model taken off?Yes, indeed. We have already delivered closeto 6,000 tonnes under the new DES modeland more deliveries will follow in the weeksand months ahead.

How much of LPG is NLNG dedicatingto the market in the new contract?

We are still dedicating 150,000 metrictonnes. The NLNG Board has always saidthat if the market needs more, the volumededicated will be reviewed.

Some industry feelers have expressedconcern about the process ofparticipating in the scheme and that theprocess is not transparent. How do yourespond to this?I dont think that is a fair comment because

we have had meetings with variousstakeholders in the LPG industry to explainour processes to them. We have explainedeverything we do, including the pricingmechanism and the subsidy which NLNGprovides for the domestic LPG supply.

We have also decided that after all theexplanations we have provided, if there arestill people who believe that our processis not transparent or that our price is notcompetitive, then they can buy LPG fromother producers, since NLNG is not the onlyproducer in Nigeria.

Will the off-takers (lifters) continue toact as a group or a club?No. we dont want that. We only did thatto start. We dont want a cartel. We want afree market. We only wanted to help themstabilise. But after three years, we believethey have had enough time to operate, so

each can stand alone, and NLNG can nowdeal with each company individually. We donot accept any anti-competition behaviour.

We want everybody to compete and selltheir product in the open market without

restrictions. We, however, encouragecollaboration in operations and logistics.They can also come together to get theproduct delivered at the terminals. It helpsin optimising the use of the vessel. Its doesnot make good business sense if one buyer

will make an order for 1,000 tonnes and wecome all the way from Bonny just to deliver1,000 tonnes, but if three or four buyerscome together and they take 10,000 tonnes,it makes more sense.

The PMS and other fuel market aredemand-driven while the LPG market issupply-driven, depending on the amountyou can get into the market. Whats yourtake on how to make it demand driven?I am not exactly sure that I agree that LPGis supply-driven. I think it is actually marketdriven. True, it was supply driven at a point,but that was a misnomer. What happenedbefore we intervened was that there were alot of dislocations in the market which madesupply irregular and unreliable. But withthe intervention of NLNG, it has becomedemand driven as it should be. However,the market is not growing as much as wehad anticipated because of a couple ofinfrastructural problems. For a long time,the NOJ terminal was the only functionalone and people who imported productshad to wait two weeks or more beforethey discharged and paid demurrage thatcompletely made nonsense of the economicsof the trade. Now with the Navgas terminal,

we can only hope that things will improve.Another problem relates to end-usersability to afford the initial capital investmentrequired to move to LPG consumption.That is a key problem. We have seen that

in India and Indonesia. Unlike with LPG,people can just go to market and buy astove for just N500, and a litre of kerosene,and they are cooking. For LPG, you needsome initial capital investment to buy acylinder and stove which is about N15,000today. You will need the stove which isanother N5,000. So you are looking at anaverage of N20,000 before you can convertto LPG. That is a big hurdle. In India, thegovernment had to intervene to help peoplescale that hurdle. They made loans andstarter-packs available to the people. Forsome, they gave away the packs for free andfor others at a subsidized rate, pretty similarto the model the telecommunications peopleare runningthey give you free handsetsknowing that you will come back to buythe top-up. They still do that in Europe.Those kind of things need to happen hereto help people overcome the initial capitalto be spent. The other big hurdle is safety.

A lot of people still have this mortal fear ofLPG. They believe it is dangerous. Sure itis dangerous if not properly handled, but itis also safe and clean; very environmentalfriendly. There has to be an educationalprogramme to help people understand thatif LPG is properly handled, it is the best fuelto use for cooking.

How do we get government involved inthese issues?NLNG has served on a ministerialsubcommittee on this and we made a couple

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

14/32

NLNG - The Magazine14

I N T E R V I E W W I T H OLINMA

of proposals. We are still waiting for someof those proposals to be implemented.

Another point is the fact that today wehave this misnomer where imported LPGhas VAT waiver whereas domestic LPG has5% VAT. That was part of our proposals togovernment to have the VAT on domesticLPG waived as well. This can be a quick winfor government. We also believe that if someof the other proposals are implemented themarket will grow very rapidly.

In your criteria for participating inthe domestic LPG supply scheme, youmentioned that you are looking forcompanies that have a complete chainin the industry. Where do small and

medium size enterprises come in?I need to elaborate more on what we meanby having a complete chain. We realise thatit will be difficult for one lifter to have allof these. So what we said was that we willalso accept people partnering, like a joint

venture, so they can control what goes on inthe chain. What we dont want to happen,especially when we are providing subsidy,is for people to inflate prices without much

value added. We just want to make surewe can have a handle on the situation. If it

gets to the user at a reasonable price, theturnover will be quick and the market willgrow.

Please describe the chain from

production to the consumer andpinpoint areas in need of investmentsand more participation?A typical chain will be from productionplant to LPG vessel for transportation todischarge terminal and then unto trucksfor transportation to bottling plants, andultimately to retailers and consumers. Thereis definitely need for more investment ininfrastructure, especially LPG terminals.In the whole of Nigeria, there is just NOJand Navgas terminals in Lagos and a smallcapacity terminal in Calabar. Definitely, weneed more terminals. We also need morebottling plants. You can also have smallbottling plants in housing estates wherepeople can go and refill their cylinders. Weneed investment in trucking to facilitatedistribution of products around the country.

We dont need to have terminals everywhereif we have an efficient network of roadsand enough trucks to cover the country.

We need more distribution outlets. Todaythere are all sorts of improvement intechnology and one can now have a smallbottling facility for about $20,000. Thereare also trucks that now have their ownmobile bottling facility and can move aroundto bottle the product for users. All of this

calls for more investments. We need morecylinders. We need to have a factory tomanufacture them. We need investment as

well in stove-making factories. There are justmany opportunities for investors.

When do you think the industry can runon its own without the subsidy?It is difficult to put a timeline on this. Ifthe market continues to grow and there areincentives and support, it is not impossiblethat this will happen sooner. If you lookat India, after several years of governmentintervention and growth, there is still somesubsidy. So, there will be some kind of

subsidy if people are to be encouraged tomove away from the use of firewood andkerosene, especially in the rural areas. It isa continuous process until we get to a point

where there is enough market penetration tostop the subsidy.

Unlike LPG, people canjust go to market and buy astove for just N500, and alitre of kerosene, and theyare cooking. For LPG, youneed some initial capitalinvestment to buy a cylinderand stove which is aboutN15,000 today.

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

15/32

NLNG - The Magazine 15

2010

From Left: Osondu Irobi, Prof Akaehomen Ibhadode,Chima Ibeneche, Yerima Ahmed and Dr Adinoyi Onukaba

HRM, Robinson O. Robinson, Eze of Ekpeye Logbo II ofEkpeye Land

Alhaji Basheer Koko, Deputy Managing Director of NLNG

Professor Ayo Banjo, Chima Ibeneche, MD NLNG and hiswife, Ugo Ibeneche

Left, Chairman of NLNG Board of Directors, Dr Osobonye LongJohn and Prof Ayo-Banjo

Jean-Eric Molinard, Mr Ibeneche and Alhaji UmaruDahiru, members, NLNG Board of Directors

Beeta Universal Dance Group in action

Mr. Ibeneche delivering his keynote address

Ifeanyi Umeh, Amanyanabo of Bonny, HRM, King Edward Asmini William Dappa Pepple III (Perekule XI), Belejit Ikuru

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

16/32

NLNG - The Magazine16

The GAN venue at Eko Hotel and Suites

Onos Birisibis Band

GM External Relations at NLNG, Siene Allwell-Brown (2nd from right), Mr. and Mrs.

Ernest Ndukwe and a guest.

From left, GM External Relations at NLNG, Siene Allwell-Brown and guests

Prof. Ben Elugbe, President of the Nigerian Academy of Letters decoratesAyo Bamgbose, inductee into the Hall of Fame for Letters

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

17/32

17NLNG - The Magazine

Winner of 2010 The Nigeria Prize for Science, Professor Akaehomen Akii Ibhadode, displays his prize

Left, President of the Nigerian Academy ofScience, Prof. Oye Ibidapo-Obe and Hall of Famefor Science inductee, Prof. Umaru Shehu

Some NLNG managers, Ibrahim Adekunle and EyonoFatayi-Williams

Chairman of the panel of judges for Literature Prize, Prof.Dapo Adelugba, announces winner of prize. To his left areProf Mary Kolawole and Prof Tanimu Abubakar. To his rightare Prof Kalu and Prof John Ilah

Basheer Koko and Alhaji DahiruOsondu Irobi speaks on behalf of his brother and winnerof the 2010 Nigeria Prize for Literature, Late Esiaba Irobi

GM Production at NLNG, Mats Gjers and his wife(left) Brigitta Gjers

Special Guest of Honour, Sam Efe Loco

Salute for winners by Beeta Universal dance group

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

18/32

18 NLNG - The Magazine

Grand entry of Amanyanabo of Bonny, HRM, King Edward Asmini WilliamDappa Pepple III

Prof. Ben Elugbe and Emmanuel Obiechina, inductee of the Hall of Fame for Letters

Prof Ibidapo-Obe decorates Sylvester Adegoke, inductee of the Hall ofFame for Science

Prof. Ben Elugbe congratulates Michael Echeruo, inductee of the Hall of Fame for Letters

Emeka Dike, son of Kenneth Dike, inductee of the Hall of Fame forLetters, collects medal from Prof Elugbe Prof Ibidapo-Obe decorates Prof Idris Mohammed, inductee into the Hall of Fame for Science

Prof Adenike Abiose, inductee of the Hall ofFame for Science

Onos Birisibi entertaining guestsYemisi Ransome-Kuti receiving medals of Hall of Fame forScience inductee, Dr Olikoye Ransome Kuti and Hall of Famefor Letters inductee, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

19/32

NLNG - The Magazine 19

I N T E R V I E W W I T H E R I N N E

How did you get involved in NLNGs domestic

LPG supply project?

We had done a number of jobs in the industrypertaining to LPG, so we had a bit of a credential.NLNG was interested in the project, asked aroundand they were given references. We were invitedto participate in the bid. We were successful andwe became the consultant to the project.

What is the focus of your company?

Matrix Petro-Chem Limited does two things. One,we provide consultancy and advisory services inthe oil and gas industry mainly for projects relatedto LPG, natural gas utilisation, lubricants, projectsdevelopment & management service depots and

facilities as well as conduct studies and technicalevaluations for clients in the industry, occasionallyfor government agencies. Two, we have a divisionthat is involved in providing chemical services tothe oil and gas industry. I am a chemical engineer

We need more

jetties, storagefacilitiesDr. John Erinne birthed the Domestic LPG (DLPG) programme with NLNG. Workingbetween 2005 and 2006 as the Managing Director of Chex and Associated Limited -consultants on the study for supply of LPG to the Nigerian domestic economy - his teamevolved the blueprint that salvaged the industry. He is a chemical engineer with over 30

years experience in the upsteam and downstream oil and gas sector and also CEO MatrixPetro-Chem Limited. Dr. Erinne is also a Fellow of the Nigerian Society of Engineers andthe Nigerian Society of Chemical Engineers.He spoke withYemi Adeyemi and Elkanah Chawai on the factors that gave birth to theDLPG programme and challenges facing the LPG industry. The interview:

by training and all these services are aligned withmy background in chemical engineering.

When you came onboard the DLPG, what was

your mandate?

Essentially, what NLNG wanted us to do was togo out and characterize the LPG sub-sector; toestablish the state of the industry at that pointin time; and to know the problems. The industrywas in a very bad shape at that time. It was in direstrait. They wanted to know what the problemwas, what the causes were and what needed tobe done in order to get the industry going oncemore.

So how did you do this?We had to discuss with all stakeholders in thedomestic LPG market as well as the majormarketers, the independent marketers, industryassociations, suppliers of equipment and

vendors in the industry, cylinder manufacturers,government regulatory agencies and all otherstakeholders. We visited all the key installationsin the country in order to ascertain their statusat that time. It involved a lot of travelling andevaluation of infrastructure.

What was the reception like? Were

stakeholders forthcoming with information?

In most cases, we enjoyed excellent cooperationfrom stakeholders. It was only in few cases thatwe were not privileged to be accorded that kindof reception. But we got enough information thatwas necessary for the work.

What were your findings?The industry started growing in the early 1990s.At that time of the study, the industry was about50,000 tonnes per annum whereas we had hit like130,000 tonnes per annum before that time. So

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

20/32

NLNG - The Magazine20

we shrunk like almost three times and that wasa problem. That was key and the trend neededto be reversed. We also established that, at thattime, the industry was depending more or less onimport because the refineries, despite promises,had failed to deliver LPG to the economy. Yet, wewere exporting about 2.5 million tonnes of LPGfrom the gas plants like NLNG, Mobil in Bonnyand Chevron in Escravos. But those plants werenot configured for the Nigerian market; they were

configured to deliver gas to the export market.It was a major challenge to see how they candivert some production to the domestic market.We were to establish if that was workable. Apartfrom being able to move that gas from the plantsto the domestic market, we had a major challengein infrastructure for reception and distribution ofgas. We were able to characterize and determinethe kind of shortfall that we have in the market.

What options did you explore to tackle the

challenges in the industry?

One of the options we looked at was layinga pipeline from Bonny to Port Harcourt. Wealso looked at the option of moving gas intothe refinery storage facility in Warri and Port

Harcourt. That was an excellent proposal becausethose facilities could be modified to accept gasinto the tanks from the waters and, subsequently,take from the refineries onshore. They had thatflexibility but the tanks, in both cases, especiallyWarri, were in very bad shape. The pipelines andall the associated gadgets were also in very badshape and they were going to require a lot ofmoney to fix.Anyway, it did not seem that the Nigerian NationalPetroleum Corporation (NNPC) was well disposedto making that kind of change. It would haveentailed a change in configuration and they werenot in a hurry at that time. They believed thatthey were likely to start producing LPG soon in

the refineries. Therefore, we decided to discardthat option. There were one or two other optionswe looked at but we had to settle with a model.We thought that if we could station a vessel to bean intermediate storage in the waters, we could

have coaster vessels to lift the product from it andthat would solve the problem. NLNG was happywith that solution.

How long is this model expected to service

the LPG industry?

We identified the model but it was also fearedthat it wasnt a permanent solution. It wasntfor us to put time limit on it because it involvesNLNG making a sacrifice by providing a vessel

for the industry and paying for it. So it dependedon how long Nigeria LNG was going to do that.

Domestic supply by NLNG has not been used

up, yet importation of LPG continues to grow.

Is there anyway to make the domestic supply

more attractive to discourage importation?

We dont have too much importation now. Most ofthe LPG we use comes from NLNG. Importationwas in two forms prior to NLNG intervention - byvessels and subsequently, overland from Cotonou,Benin Republic. Importation by vessels virtuallydied out. Importation from Cotonou persisted a

while, but is no longer consistent because thereisnt much room for it. It is a little more expensiveand has a longer supply route with a lot of risksand difficulties. Basically, the industry now relieson NLNG to supply gas.

Some experts feel that limiting the players

in the project to six then hasnt helped the

market at all. At what stage was this decided?

We didnt limit ourselves in terms of numbers.It was based solely on how we perceived theirpreparedness in respect of the entire LPGsupply chain. We were looking for people thatwould try to work in consortia to provide thecomplete supply chain capability. There wereindividual companies which had capability in some

aspects such as trading, shipping, bulk storage,distribution, bottling and marketing. That wasntgood enough. We therefore encouraged them towork together. On this basis, we were able toselect the six that had met the required criteriaas closely as possible. In this kind of situation,you can never satisfy everyone. There will alwaysbe some complaints, but one thing was clear:the intervention of NLNG saved the industryand marked the beginning of recovery of theLPG industry in Nigeria. Today, for the past threeyears, people go to the service stat ions and retailshops to buy LPG without hassles. Prior to that itwas a big problem and prices were very unstable.Now, it has reasonably stabilised.

Do you think the market is liberal enough?

Yes, it is. LPG market is perhaps the most liberalin the downstream segment of the oil and gasindustry.

I dont think there is anymagic about this. The mostimportant thing is to get intoa situation where we haveadequate primary storagesfacilities and jetties.

Also, we agreed with NLNG (and I thought thatwas an excellent strategy) that whoever wasgoing to participate in the scheme should betied to developing infrastructure over a periodof time. NLNG came down to three yearseventually. Part of the problem we identifiedwas the bottleneck at Apapa. Everybody wasgoing into Apapa and all the vessels importingrefined products came there, jostling for spaceto berth. Priority went to the refined productsbecause if there was no petrol or diesel in thefuel stations, it could become a big problem onthe streets. Consequently, LPG was lower downin priority ladder. Also, there is a limit to the sizeof the vessel that brings LPG to the jetty in Apapabecause of the water depth. These were theproblems NLNG envisaged and that was the basis

for telling the offtakers to develop infrastructurelike coastal storage facilities and jetties to acceptand discharge LPG.

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

21/32

NLNG - The Magazine 21

I N T E R V I E W W I T H E R I N N E

NLNGs intervention has assured availability.But has it really assured affordability with the

dearth of infrastructure? How can we address

this?

First, we have to understand that whatever pricewe pay for LPG has some bearing with the costof crude oil in the world market. In the last twoyears, we have been almost constantly at the levelof $80 to a barrel. This has to have some impacton the price of LPG on the street. Once we havethat in mind, I think the prices would have tobe considered to be reasonable in that context.I think that part of the problem is not so muchthe cost of gas but the cost of the accessories forapplication of LPG. A starter has to buy a cylinder,a cooker and these things cost money. And thismay not be affordable to everybody and that ispart of the problem. I know the industry haslooked at different ways to solve this problem tosee if there can be some subsidy or structuredfacility that can enable new entrants to get intothe market, but I dont think anything has workedout.

What were your findings in the downstream

sector, most especially the movement of the

product from storage to the consumer and

what was your understanding of the market

at that time?

The industry was almost comatose. Theinfrastructure and facilities for distribution

and marketing of LPG were not in good shape.The way the industry was structured, we hadprimary storages that were at the coastal areasor the refineries and the product was expectedto move to secondary storages inland; and fromthe secondary storages to the filling plants. Wealso had a special set of storages that were setup by NNPC in the early 1990s. The projectwas supposed to popularize LPG in Nigeria andthey built a set of 12 depots for LPG across thecountry. They are in Calabar, Enugu, Makurdi,Lagos, Ibadan, Ilorin, Kano, Gusau and Gombe.They were commissioned but never put incommercial use after completion because LPGdried out from the refineries. The idea was forrefineries to supply these inland depots withstorage and marketers will load from the depotsto their filling plants. But it never worked. After10 years, they were not in a good shape to beused immediately. Also, several of the bottlingplants were not in use because there was no

product. They couldnt be put back to usewithout considerable work. A lot of trucks hadbroken down and people had moved away fromLPG. These were the things we discovered andwe knew that it was going to take considerableinvestments and effort to get the industry backto work.

Most of these facilities have come back with

the intervention of NLNG. Can you give

an objective analysis of the usage of these

facilities after the intervention?

Those NNPC strategic depots have not reallybounced back as such. One or two are being putto use; they were privatized four years ago andhave a major problem of not being connectedby pipeline. So there is a double handling issue.Hence, those facilities are not fully utilized. But alot of the other small secondary storage facilitiesare being used. Some plants initially abandonedhave been reactivated and new trucks put intothe market. That is why we have moved from50,000 tonnes per annum to about 90,000 tonnesnow. That tells you that there is progress andyou cant make that kind of progress without thedownstream.

Most of these facilities are investment

opportunities. But why have they not got the

required investments? Are the opportunities

not attractive enough?Like I said, investments are beginning to flow intothe industry. A number of people have investedin trucks and filling plants. Some of the old plantshave been reactivated. The major investment willbe required in primary storage facilities to beable to receive bulk volume from the vessels intocoastal storages. A number of the off-takers aredeveloping their own facilities and by the time wedo that, it will help open up the industry. Therewill be more availability of the product. Gas is stillnot as available as it is required because of thebottleneck in Apapa.

Cylinders have been identified as the missing

link to the development of the market. What

is your take on the solution?

Cylinders are very critical for LPG distribution.I am going to talk about this from a commercialand safety angle. I was hoping that when lifebegins to come to the industry, owners of existingcylinder manufacturing plants in the country willbe encouraged to make necessary investment torefurbish their plants and support the industry.Unfortunately, that has not quite worked out Wehave two plants, one at Ibadan and the other atAbeokuta.. I am a believer in local content andI believe in the support of local manufacturingas much as possible but not to the detrimentof the business. Increasingly, people have beeninvesting in importation of new cylinders which

have grown the industry. A lot more investmentsare still required in cylinders if the industry hasto continue to grow. The industry is still not atthe level we expect it to be. We expect rapidgrowth to be sustained. I project that Nigeriashould be able to consume more than 300,000

tonnes of LPG. That will require continuousinvestment in facilities like these. That is on thecommercial side. On the safety side, there is stillno clear cut mechanism or platform for managingthe cylinders and making sure they meet thetechnical requirement for safety. Some years ago,a study supported by the American governmentwas done by the Federal government. The studywas very extensive but, unfortunately, the reportwas never implemented. It appeared the reportdisappeared. It was going to be the basis forproper management of cylinders by the industryto ensure that the safety of consumers is properlytaken care of.Some people who wanted to invest in the industryin the past were a bit concerned about the safetyissues. The industry was chaotic at the time anda lot of people refrained from putting money in. Iknow that the Department of Petroleum Resources(DPR) has done a lot on regulations, especially onthe cylinder, but we still have a long way to go toensure they are properly managed.

If you were asked to suggest a better model

or tweak the model being used now, what

would you suggest?

I dont think there is any magic about this. Themost important thing is to get into a situationwhere we have adequate primary storagesfacilities and jetties. As long as we dont havethese, we have a problem on our hands. It is

clear that the refineries will not provide anystrong support for the LPG industry in Nigeria.The medium term supply, and possibly longterm, is from marine vessels. So we need to havethose storage facilities because that will be theemphasis.

What drives your passion for the LPG

industry?

I am a chemical engineer. My first job in theOil and Gas industry was LPG Coordinatorfor Texaco Nigeria Limited, as it was in thosedays. Essentially, they wanted someone whohad a combination of technical and commercialunderstanding to expand the LPG market forthem and that was how I was hired. As a chemicalengineer, I could understand the characteristics,handling requirement and the infrastructure forhandling LPG. That was on the technical side. Ialso showed I had a basic understanding aboutthe market and distribution. That was how I gotin. I found it very exciting and challenging. Whenthey moved me out of the job two years later, Iprotested vigorously but the management thoughtit was time to move to the core business. Thatwas how I got into the lubricant business. But Inever took my eyes off LPG. When I left Texacoin the 1990s to set up my company, one of thethings I did was to keep touch with LPG industryand I had a number of clients who came to me forstudies and assistance to set up bottling plants.

From my training and experience, I developed apassion for LPG and I have a personal commitmentto see that the domestic market is reasonablywell developed. LPG is the most convenient fuelyou can use for cooking at home and for severalindustrial applications.

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

22/32

NLNG - The Magazine22

I N T E R V I E W W I T H E K U N D A Y O

How did the domestic LPG supply business

start with you?

I was privileged to work for Nexant Limited, anenergy consultancy in the United Kingdom, andin 2003, we were approached by the World Bankto bid for a project to investigate why the LPGmarket was moribund in Nigeria. In the course ofpreparing that bid, I identified an opportunity inthe market after looking at the entire value chainand concluded that the bottleneck then was incoastal infrastructure and logistics. That was thehighest impact point of investment.It became almost a burning passion at thetime. Over the next few years, I moonlighted,developing a business plan. Sometime in 2004,we (my partners and I) requested for a meetingwith Dr. Andrew Jamieson, Managing Director

of NLNG at the time. We met him in the NLNGoffice in London in August 2004 on the day theFinal Investment Decision (FID) was taken onTrain 6 NLNG and made a presentation to him.It was supposed to be an informal presentation.

Cylinders,

the next frontierFelix Ekundayo describes his entry into the cooking gas (LPG) industry in Nigeria as purebold-face stupidity. Dont be fooled! Behind that claim is a passionate man working hardto see that the cooking gas market grows out of its inertia. Mr. Ekundayo has over 21 yearsexperience in the Oil & Gas industry.The UK-trained chemical engineer spent more than 11 years of engineering experiencecovering midstream and downstream oil and gas processes - in particular, refineries, gastreatment plants, petrochemical plants, pipelines, and offsites & utilities with a numberof multinational engineering companies like Foster Wheeler, ICI, Bechtel and Stone &

Webster. He was a Senior Consultant with Nexant Limited, world renowned managementconsultants to the energy industry. During his time with Nexant, he consulted on variousmulti-billion dollar refining, gas, infrastructure, LNG and petrochemical projects aroundthe world and in 2006 founded Linetrale Gas with family and friends. He is also theManaging Director of Gas Terminalling and Distribution Limited. Linetrale Gas is one ofthe off-takers lifting gas from NLNG. Mr Ekundayo is currently Chairman of the Off-takersClub. In this interview with Elkanah Chawai andYemi Adeyemi, he gives one of themost lucid expos of the LPG industry in recent times. Excerpts:

Five minutes into the presentation, Dr. Jamieson

excused himself, asking us to wait (we thoughtwe had upset him). He returned with the DeputyManaging Director and the Commercial Managerand requested that we begin the presentationagain. At the end, he seemed impressed andremarked that we sounded like bona fide peoplewhom he thought he could do business with.Though, he felt NLNG was likely to encounterproblems with its Memorandum and Articles ofAssociation if they adopt what we proposed, butpromised they would address the issue internally.His concern at that time was that NLNGsMemorandum and Articles of Association did notallow it to participate in the domestic market butthat the company was under enormous pressure[from the Government] to participate in the localmarket. He bought into our idea, which gave usthe early confidence we needed.That was our introduction to NLNG, thoughthe company wasnt called Linetrale Gas at thetime. Unfortunately, things didnt go quite as

smoothly as we expected and a couple of months

afterwards, Dr. Jamieson was transferred andwe lost that continuity. But we kept pushing inthe system and the preliminary Domestic LPG(DLPG) programme kicked off in 2005, whichcoincided with when I had decided to hand in myresignation at Nexant in order to come and startthe business in Nigeria.

What did you do when NLNG threw the idea

open at the stakeholders forum?

We had been working individually with NLNGbefore that town hall meeting. Our initialproposal had, in fact, been short listed alongwith one from Bergesen and the choice wasto go with either or get us to collaborate. Mypartners and I travelled to Oslo and Bergesenagreed to put its mother vessel proposal in withus, a major achievement for a start-up company.Unfortunately, as we understood it, our proposalgot to the NLNG Board where it was decided,under the Chairman at that time, to throw the

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

23/32

NLNG - The Magazine 23

process open. It was a bit of a disappointmentto us. In any event, it made it more legitimate.So, we attended the town hall meeting andresubmitted our proposal. We ended up asone of the 11 shortlisted in June 2006 and wewere invited to make a series of presentationsto NLNG thereafter, finally emerging as one ofthe four originally short listed off-takers, whichsubsequently became six .

These off-takers came together to form a

club. What prompted that?

NLNG prompted it and that was a good thing.

The crux of the problem was infrastructure. Inso far as we were not all going to go out and getindividual vessels, we were going to share somefacilities in common in order to save cost. In doingthat, we needed a forum to come together. NLNG

brought the idea and with our own backgroundand familiarity with the Major Oil MarketersAssociation of Nigeria (MOMAN) model, LinetraleGas proposed to the others (that was actuallythe first time we met with them) a model wherecompetitors work closely together on operationalmatters. We brought the MOMAN charter tothe table. The six members of MOMAN formeda body that operates the three main marketersjetties in Apapa that were initially problematicin terms of bringing in white products. We weregoing to be using one of these jetties, NOJ. So, ineffect, some of our ground work had been done

for us because MOMAN already existed and wedid not need to reinvent the wheel. By and large,the charter for the off-takers club reflected whatMOMAN was already doing.The interest that arose and the pressures we

got from all sorts of quarters, especially thelegislature, was the accusation that we werea cartel. That came up every time. MOMANconstitute the bulk of hydro-carbon productscoming into Nigeria and are not seen as a cartelbut rather they are seen as working together toovercome infrastructural challenges. Meanwhile,the off-takers constitute less than 1% of hydro-carbon products coming into the country andwe were simply doing the same thing in the gassector. It was incredibly burdensome when wefirst started the NLNG programme.

How were you able to overcome that image ofbeing a cartel?

I think the legislature did not have the facts rightat first, but we managed to educate them alongthe line.

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

24/32

NLNG - The Magazine24

I N T E R V I E W W I T H E K U N D A Y O

How would you rate the cooperation withinthe club?

The cooperation within the club, as you wouldexpect from competitors brought together bycircumstances, was fraught with challenges in theearly stages of the programme. We would reach anagreement but as soon as you walked out of theroom, one party would not honour it because atthat point in time it didnt meet their commercialrequirements. Those were teething problems youwould have in any new marriage. What developedlater was that people started to trust each othermore. More importantly, the way we interactedwith each other built that bond of trust. The clubwas also set up in a way where the chairman andtreasure positions rotated every six months. Atone point, the club decided to retain the treasurerposition with one company because it wasnt justpractical to move bank accounts around. It wasan indication to the fact that trust had started tobuild.All the past chairmen did tremendously well ingetting us here today. Towards the back end of[the DLPG programme], the global economiccrises set in and some of the flaws we hadseen in the [original 3 year] NLNG contractbecame apparent. They almost put some of usout of business; at least two of our numberswere severely damaged by the downturn. Therealisation dawned on everyone that the impactof the programme could be a lot better if more

effort was focused on the external and not theinternal problems. We turned the internal offtakermachinery to just an operational machinery sothat we could then go out and face the expansionof the market. The whole purpose of having stable

supply is to go out and develop the market. Andquite frankly, we all have our niche in the market,so if we focus on market expansion, it can bea positive collaboration, not just one where weerode each others competitiveness.

After three years operating with NLNG on

LPG, how much has the demand grown in the

market?

There is a misconception about LPG. Oil productsare Demand Driven because there are millionsof cars on the road. So, if you bring your cargoin and the price is right, it will be bought. Gason the other hand is Supply Driven. The supplyinfrastructure to push gas into the market has

to be as efficient as possible to make it as cheapas possible. Gas has alternatives. I cant run mycar on water. I have to use gasoline. I am lockedin and so it is demand driven. On the gas side,if it is too expensive, I can shift to kerosene orfirewood. Supply of LPG has to be in a way thatmakes it cheap so people can access and afford toconsume it.You then have to understand that the supplychain is not simply one bottleneck but a series ofbottlenecks. Imagine the LPG market as a double-ended funnela funnel at the entrance andanother at the exit. At one end you have unlimitedsupply in terms of all the new producers in thelast 10 years or so; at the other end you have nearunlimited consumption in terms of latent demandin the domestic market. Supply was the initialbottleneck, which is where NLNG came in andmade a difference. Then you go on to terminals,transportation, filling plants and cylinders. Theinterconnecting value chain or tube between thetwo funnels wasnt particularly straight: therewas under investment at the front end in termsof terminals resulting in a choke point; there wasover-investment in the middle in terms of fillingplants (there are over 300 filling plants in thecountry); and there was chronic under-investmentin the last mile (cylinders and distributors)resulting in a another choke point.NLNG came in and sorted out the supply aspectbut there was insufficient terminal capacity. Theofftakers spent a lot of money assisting Pipelineand Products Marketing Company (PPMC) inupgrading their facilities. Our recommendationsand initial funding in terms of getting the PPMCterminal back up to improve load-out wereacknowledged by PPMC. We started with oneload-out bay but today, four are operational.This means that their through-put ability hasquadrupled. PPMC at that time could onlymanage 11 trucks (220 tonnes) a day but nowthey can comfortably do 40 trucks (800 tonnes)a day. Many of us also had our own investmentprogrammes. Other (third) parties had theirinvestment programmes as well and two of themhave been successful in completing their facilities.

The terminal end has now been opened up. Butthe story is not complete in terms of bottlenecks.In terms of transportation, offtakers have beenbringing in trucks so this particular bottleneck isbeing alleviated on an ongoing basis.

Presently, there is excess capacity in terms offilling plants and we believe many less efficientfilling plants will shut down in the medium term.For example, Linetrale Gas has three modernfilling plantsone in Kano, Abuja and Lagos.They are all completed except Lagos which is 99%complete. Kano and Abuja have the capacity of25,000 tonnes per annum each and Lagos muchin excess of 50,000 tonnes per annum. Just thethree filling plants have the full capacity of thecountry and there are 300 filling plants around.You have got the funnel really wide open atfilling plants then you come to the finally criticalcomponent - the cylinders. That is our majorchallenge.

You cant underestimate the kind of problemsNigeria has with cylinders. It is a regulatory,consumer and supply problem. On the regulatoryside, there is no control over the street tradersand we need better controls and not just from theperspective of protectionism. You cant channelthis product to the consumer safely using bottlesthat are 30 years old. You cant achieve efficiency

With the new DESmodel, the needfor a Mother Vessel

and ship-to-shipoperations has beenlargely eliminated.

in a market where NLNG spends millions ayear on the supply vessel; upstream players areinvesting in gas processing plants; the NIPCOfacility probably cost between $25m and $40m;Navgas spent $50m; Linetrale Gas has spent over$10m on infrastructure; and there is what otheroff-takers have spent. Yet all these investmentsare dependent on a man who is carrying aN2,000, thirty-year old bottle as his only asset.If anything happens with the consumer, theyare not going to hold the street guy who soldthe cylinder responsible, rather the owners ofplants and others along the supply chain are heldresponsible. For these reasons, regulation needsto be stronger.From the commercial perspective, imagine a gasbottle as a bottle of Ragolis water. In the totalvalue chain, NLNG and other suppliers takeone-quarter; Off-takers take another quarter forlogistics and distribution; then you now have thestreet trader who has invested little taking 50%of the market value as his margin. So when youhear that the price of a cylinder is N2, 500 in thestreet, you can more or less halve that number

to see what the offtakers component is in termsof sale price. There is no incentive for us. Wesometimes end up selling below cost just to pushvolumes into the market. Why then would I invest$10 million when I can just go and buy a 30-year-

-

7/30/2019 How to make money from cooking gas

25/32

NLNG - The Magazine 25

old bottle with a hose and sit on the street andmake more money per tonne? That is the kind ofproblem we have today in the LPG business. Thatis why off-takers have to push the frontier and goand compete at the distributor level. The model inthe country now where street traders come to youto fill is inefficient and is not sustainable.We did a study at our plants and found out thatalmost 70% of gas goes out as 50kg cylinders.That means we are effectively selling to ourcompetitors who resell on the street. Theconcept is that we go to the next level, whichis warehousing this involves deploying 500cylinder capacity warehouses in neighbourhoodsso that the end customer knows what your price