Horden&Purcell Corrupting Sea Cap3

-

Upload

ventocontra -

Category

Documents

-

view

135 -

download

1

Transcript of Horden&Purcell Corrupting Sea Cap3

"*J ,:.;"J

The .C·O·.·..,· 'rru"';" : P·.· -"'. t'fig' ; ': ;' ... :,'. .'. ' .. , •. ',,' •. :" :"".'<"

S···..'·'··ea..'·", ". . ...

-. , . " "

A STUDY OF MEDITERRANEAN HISTORY

Plaro thinkx thar thosc \\'110 wanr ;] wcll-govcrncd cirv ought ro shun lhe SCJ JS atcachcr of vicc (pOIw·odidaska.!os).

Srrabo , C;"O.rrmplll', 7.3.8

\\~lcrC'1t hc said firrnly: 'Whcn vour Excellcncv wnrcs J book , vou will nor sav:"Herc thcrc is J bcauriful church and J grcar castlc." Thc gcnrry (JIl sec rhar ti)rrhemsclvcs. Bur you shall sal': "111 rhis village rhcre Me no hcns." Thcn thcv willknow frorn lhe bcginning whar sorr of counrrv it is.'

Gcrtrudc l-lell (!<)07) 77l( {),J<Tt n ni! thc SOIl'II, <)3

PEREGRINE HORDENAND

NICHOLAS PURCELL

li]BLACI<WELLPublishers

'Phvsicallv, thc counrry ma)' bc dividcd inro four belrs', lhe Arab geogL.lpheràl-IV!lIq~ld:L)si wrorc (lf Svria ~lllJ rhe Lcbanon.

TIl<" lir.sl bclr is rh.n on rhc borde r otthe Mcdir crrancun sca. Ir is rhc plain countrv,lhe s~ndy rracrs following onc anorhcr and altcruaring with thc culrivatcd land

. Thc scrond bclt is thc mountain country, wcil-wooded and posscssing munvsprings, witl: trcqucnr villagcs and cultivarcd ficlds ... The third bclr is rhar (li" thevallcys of thc Gh311r, whercin are lound many villagcs and streams, "Iso p.ilrn rrccs,wcll-culrivatcd ticlds anel indigo planrations . . The fourth hclr is rhar bordcring011 lhe dcscrt. Thc mounrains hcre are high and blcak and thc climate rcserubicsthar of rhe 11 as te . Bur ir has n1all)' villages, wirh springs of water anel toresr trecs.(adaprcd trorn Miquel 1963, 85) .

Coasral plains of inrerrnirtenr fcrtilitv backed by woodcd mounrains and dcserrplatcaux , mixcd cultivation, sporadic scrtlc mcnt - ali qualiries of Mcditcrr.uicanlandscapc as t;lI1liliar to rhc traveiler as to rhe gcographcr. Thc problcm is tharcvcn such tasridious gcneralizations as ul-Muqadassis no more rhan hinr ar aninfinitclv complcx local rcaliry. Worse, thev givc a11 irnprcssion oi" uniíorrniry, offundamental rescmblancc bctwccn one rcgion and auot hcr , that is disust rouslvmisleading. Wc can ncvcr hope to (0111e to 311 undcrsranding 01 whar can use-flllly hc said (lf ihc Mcditcrrancan-widc human or physical landscapc until \\"care rullv scusirive to lhe cuormous varictv und diversiry 0[" cnvironments withinlhe basin of thc sca , nor just to rhc constants that apparently undcrlie thc (h305.

for rc.rsons which wc began to examine in I'art Onc , thc distincuve tcxturc ofMeditcrrancan lands is nor to be soughr in thc listing of typical ingrcdicnrs oflhe visible landscape , a srrategy in which obscrvation is ali too casilv overpowcredhy tradirion. Ir is rathcr to bc found in rhc phcnomcnon of 'subdividcdncss' -or , to paraphrase our epigraph frorn Lévi-Strauss, in thc continuurn ar discon-tinuitics. How is rhat conrinuurn to be dcscribed anel expiaincd?

Ar rhe cnd of rhc prcvious chapter wc cxplorcd the scnses in which an eco-logical approach rnighr be ar servicc to rhe hisrorian. To rhe ditlicultics thercseen to arisc, wc musr add furrhcr problcrns thar emerge trem lhe cxarninntion01" particular localirics. This cnablcs lIS to progrcss towards an excmplificarionof what thc 'historical' in our 'historical ccology' might mcan , as wc outlinc rhcnaturc 01" Medircrranean inreraction and thc charactcr of rhc microccologicalregions of which ihat inrcraction should bc predicatcd. A properly historical

54 Ill. FOUR DEfINITE PLACES

ccology \ViII ccrtainly nor be content with cithcr thc enumeration or thc classification of local fcarurcs. At lhe lcast it \ViII also havc to look at the dynarnicsof their inrcrplay with hurnan and animal populations, Em that will only rum ir'into a buman ecology - 01' a kind rhat rnay, we have suggcstcd, pay a hcavy priccfor irs inclusion 01' hurnaniry in terrns 01' thc biological reducrionism and rhc narrowncss of tocus that are alike rcquircd of ir. History has to bc broughr imo rhcccological picture in lWO ways: [irst, most import antly, in lhe avoidancc otrcduc-tionism rhrough lhe iIl \'(1cati 011 of as full a polit ical, social 0[' cconomic contcxr- spanning as lengthy a pcriod - as rhe localiry scerns to require; sccondly, in lhepursuit of that contcxt , through thc 'unbounding' of thc systCI11S on which ir isto be brought to bcar , 50 that thc 'dcfinitcncss of placcs' is always qualificd I1\'

thcir "intcrdcpcndcncc'. Thc imagc ofthc fuzzy ser, mcntioncd in IrA ;1.1 appro-priarc to lhe Mcdirerrancan as a whole , can now, as wc hopc to show in thisPart, be e xtendcd to thc microccologics of which thc rcgion is corupriscd. TI1(1'

will be sccn to have thcir íoci and their rnargins; bur thcsc are al\\'a1's changing,can scldorn bc casilv rclatcd [O aspccrs of gcography. and are ar ali times ['CSI?()!lSivc to lhe prcsslJl'cs of a much largcr sctting.

Our cmphasis in this chaprcr is thus \'lTy diltcrcnt írom t hat (lI' lhe 'geographical background ' thar inrroduccs so riun)' historic.il wor k». Ir cn.ibics L1S 10

.IreI' J lirrlc asidc 1;'0111what II'C havc broadly idcntificd as thc Rom.uuic t raclirion 01' Mcditcrrancall dcscription , wit h irs scduct ivc but Illiskading imagcrv. fIavoids an unprofirablc scicntisrn. Ir begins [O dose lhe gap- to which II'C ,shallbricfly rcturn at thc cnd of thc chaptcr - bctwccn the spccializcd intcrcsrs o;'lhe ccologist and more traditional polirical , social and eeonomie conccms in thestudI' of the past And it lcads naturallv imo thc subscqucnt discussion 01' thcdcgree to which lhe ccological approach can be cxrcndcd, tirst to largcr serrlcments (Chaptcr IV), thcn to rhc rcgion as a wholc (Chapter V),

In whar follows, thcn , wc approach Mcdircrrancan hisrory bv wav '01' ir5microfoundarions - its shorrcsr distanccs. Wc look ar four localitics in Ihc Medi,tcrrancan world - to sho-v how cornplcx is lhe intcrplay o!' ccological belOrsthat gil'cs each its apparcnr idcruiry or dcfinition; and to suggest rhar the principal elcmcnts in a microcc.ologvs ch.iracrcr derive as rnuch from its changlllgconfigur.inon wiihi» rhc wcb 01' intcracrions around ir, across ,jggregarcs ot'short disranccs'. as Irnru any long-Iasring phvsic.il pcculia-it ics.

1. THE BIQA

As mclaucholy political cvcnrs 01' our 0\1'11 time havc crnphasizcd , onc 01' rhcprincipal ingrcdicnts ot' the ropography 01' thc Lcvant is the grear vallcv bctwccnthc Lebanon and Anti- Lcbanon mountains in which rhc Oronres riscs, inlandfrom rhc south Phocnician coast (Mal' 2), It is known as the Biqa (or Beba), anirnmernorial narne applicd also to other abrupt vallcys and dcrived from a Serniricroot signifying a split. Aptlv; because rhis grcat vallcv some 100 kilornctres longand about 25 kilornetrcs widc, is a grcar dowu -taulrcd rrough, part of a tccronicsystcm stretching from the Taurus mountains of Anatolia to thc lakcs 01' EastAfrica by way of thc cvcn more pronounccd rift vallcys of rhc [ordan , lhe ReeiSca, and 01' Kcnya anel Tauzania. On cithcr side the vallcv is bounded bv lhestccp clifE of rhc mountains, which risc frorn thc vallcy floor at 2,OOO-3,O()()

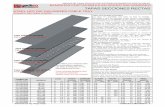

Key

lIiilIII Wetlonds

Streom-coursossemanal ond perenniol

Map 2 'lhe Biqa and its scrtingThc 1ll.1pis simplificd from thc magnificent geonlorpho!Og,icJI cortograrhy of de Vaumas

(ltJS4), The crfccts of the srceply dcclining r.unfall from \\'CS! 10 cast and from SOLHh tu northare apparcnt, ln addition therc is ver}' markcd variabilirv from ycar to ycar. 111 187R Bcirurrcccivcd 1,234 111m; in 1933 only 43R (de Vauruas 1954, 224),

56 1Il. FOUR DEFlNlTE PLACES

f(:C[ abovc sca levei [O SUl1ll11i[ lcvcls ot' more rhun 12,000 teet in rhe highlcbanon. For manv rcusons, this apparently sirnply boundcd g,eogr:lphical rcgiouhas a bcwildcring divcrsiry of ropcgraphv and environmcnr; ir reprcscnrs a dcgn:eof fragnlCtltation that makcs it an excellcnt exarnple with which to opcn oursequencc. Anel, as a furrher advantage , it lias been the objccr of detailed andprovoc arive acadcrnic study (Marfoc 1979).

Thc complcx ccology of this vallcy is dominated above ali by U1C diftercntinflucnccs ar the adj.iccnt mounrains, which producc varying degrces 01' rain-shadow and of shcltcr Irorn prevailing winds, and which each crcatc, by theirparticular aspect , cxtrernely local clirnatic conditions. Altitude, exposure andprecipitarion combine [O forrn a spcctrurn 01' minoenvironments, ranging frornlhe supposcdly clussic 'Mcdircrrancan" conditions of me sourh to rhe scmi-aridplains of rhc north. Hvdrology furthcr complicares lhe picturc. Thc abundantrainElIl of rhc Lcbanon mountains fccds numerous springs, but thc bcdrock isrhe limcsronc which g,il'cs rise in .10 1l131l)' parrs of thc Medircrrancan tu thcsccnerv known as karst (VIl 1.2). Thc disrribution of ground\\'Jta aud springsin t lus lyl'C of i.uidscapc is hig,hly crratic , anel rherc are both warerlcss aros Jl1dO;1SCSor marshv borroms. Thc strcams draining trom thc 1110Ullt:ÚI1Shave torrncdrcrrnccs and tans of usuallv íer tile alluvium, alrhough in rhc scmi-nrid north rhcirvallcys are more like wadis. Anv lisr ot cnvironrncnts must, howcvcr , also includclhe vullcvs pJL111cl to lhe Biqa in lhe high mountains, lhe surnrnir .plarcaux ,anel rhc rocky clitls and slopcs of lhe íuulr searps 011 both sides of the vallcv.Altogcl:her, climatc and gcology have produccd a dcnsc partem of cxrrcrnclvlocal e nvironmcnts. And rhcsc orfcr hurnaniry lhe widesr selection of ccologicalniches.

A survcv of thar kind inevitably givcs :111ovcr-flartcriug picrurc of the naturalendo\\'ll1cnts of the region. Modern geugraphers lIsing JVCfage raintJll figures,like thei r :\l\eieIlt or mcdieval predcccssors (sueh :15 Al- M u'l:1ddasi) lo(\king 'Hlwrcllnial springs '1I1d II'cll·riJk:d lields, hal'c hJd IlU hcsitati<lll ill hbdling the13ilp as tenile. But krr.ilit)' is no!. dn absoltltc oC scientific IllcaSurcmcllt; ir is aililllpressionistic, clllrurallv ladcn, rcrm (V1I.l). t.,loreol'tr, gencralivriom 'lhllutregional i"enililY ignore j1:\rricubr conditioils -- in rhis Clse, no! only cOl1dirjoilsin the al"<::1, where rainfJl1 is consisteml\' \\"cll bel()\\' :l\'eragt, but also thosecreared \\"ithin rhe :m:as of ahove·;tvnage precipilatioll by il11l1lcnse allm[;l) andscasonJ.1 v'lriability in lhe \\"cather. Winter tJoods ai1d SUIl1il1er droughrs 'Ire rhepcrenniaJ hazards of a Mcditcrranc3n landsc'lpe; a village too Lir)' for habiratiol1()nc ycar C'1I1hc ,limoS! 11"lshcd aW;l1' the ncxr. .'\nd rhe Biep has extra prnhlems:ullusually j100r rains in the spring, \Vith cOllsequentl\' kl\\ discharge of \VarnSOLlfces; strong prc\'ailing winds thar erock the soil in areas unshcltered by theJl1ountains; a high carhonare horizon; malarial Sll'al11p5 in the south. Thc s\\'3mpsan: rhc ren1:lins 01" a lake artificiall)' drained berwecn 1320 alld 1339, J lakcwhosc eapriciolls rise and fali had led to the loco.lizo.tion in rhe \icinitv ()f tales ofthe Fload and or Noah and his sons (Dussalld 1927,402).

This vallcy is not rhen an arca thar on rcadil\' be irrigatcd. El'en u1e advent ofl110dern reehnology - dams, borc-hales, pllmps, ,lll the meJns (lf .,()il improve-I11CI1I:- !tas apparenrly aHccted no more thal1 a ljll:Jr!er ()I" rhe total L1l1d 11l1dcrculüvation. Systel11s of the typc uSlIally labelled 'dry brming;' h:\\'e always beellthe norm - in so tãr :lS the valle)' C3n bc said to display a l1orll1. for the cata-logue 01" t:conomic strategies is natur31ly as di\'ersc :lS thar of the cOl1ditiollS rlUI

1. THE BIQA 57

necessirate mCI11_ Ovcrall only one third of rhe vallcy is cultivarcd; and withineach of the many zoncs imo which a gcographcr ar an ccologisr divides ir, thcland undcr cultivarion varies frorn lcss than a fifth to barcly more than a half ofthe surface arca. The rneans 01' livelihood can take rhc form of highland tcrraccugricuiture, lowland cereal dry farming, ar (more rarely) sWJmp drainage or springirrigarion. Land is productive and profiruble only sporadically; and it is rhescisolared patches that are gencrally dcvoted to crops like cereais and legumes.

lrrigation rcrnains 50 cxpcnsive and incfficicnt thar only lucrative cash eropsmake it worthwhile. The place with which it lias been longest associatcd isBaalbek, the ancicur Heliopolis, where prosperiry has nlways dcpcnded on azonc of intensivo irrigated culrivarion. Ir is írorn ccntrcs likc this rhat irrigationcan De cxrcnded, and to which ir CJn rerract, dcpending 011 the circurnsrancesgoverning rhc choicc 01" agriculrural str.ucgics and rhe dcgrcc of inrcnsification(or abatcrncnr ) rhat are appropriate trorn one pcriod to anorhcr (VI.i; VII.4). Inlhe Biqa are prornincnt ccntrcs of horticulturc or ar boriculturc , such as EI Qa' atthe source of thc Oroures - its ancicnr narnc, Parudcisos, being an cloquentcxprcssion uf irs fcrriliry. And such cnvironrne nts Icnd thcmsclvcs to the highlyvisiblc prnduction 01" specializcd cash crops, JI110llg rhcrn thc narcotics for whichthe rcgion has been nororious in vcry rcc cur times. Bur pockcrs of abundanceshould nor bc .illowcd to determine our estimare 01' the wholc arca's porcntial.The pockcrs are roo isolated; their cconornic cflects do nor radiatc lar enough.Baalbck, ir is worrh noring, has functioned as a symbolic focus for thc arca borhrhrough thc religious imporrance of its templos, and also bccuusc ir has bccn a(entre of cnvironrncnral irnprovemcnt (t\\,(1 funcrions that we shall see associarcdin Part Four bclow). Ir does not follow that Baalbck has been decisivo in shapingthe ovcrall social ,1I1d cconomic pacterns of the valle)"s hisrory. Despire having a i

major 'central placc', rhe Biqa does nor behave as the rcrricor)', the ccologieal 'hilltcrbnd, of a cily -- disperscd or fragmenrc.:d rhough \\T shall find [hat sort ofhimcrland to hc (1\'.8). 'Une ci\'ilisatioll agricok a hien pu s'v dévélopper, celkci n ',.Ir jamais arril'ée ,\ donner I1ais.l<lnCC1 une perite région politiquc COIllI1le ilexiste Lll1l dans k pl"Oche-Oricnt. F:!it tvpiquc: JllCllIH': I'ilk importam n'y existe'(DlIssalld 1927,315).

Contra r)' to \\'hat glowing accou!lts or' J Meditnranean region's krtilir)' 1m}'rhlls leal! lIS to expect, agricltlture is ver\' ot"tt:n ha/.ardOlls alld )'iclds are lo\\".Thc twclllieth-celltllry alrernatives to ag;riclllturc have bcell the usual 011<':5:anil11J1husbandry, migration to the lo.rgest sc.:tt!cmcI1ts, cmigration. UnLÍI (ompar~1til'el\'["(.:cem"- rhe !it-st altern'lti\'c has bCCll lhc predol11inanr rccoursc. So, to the alr'-~ad~'long list of types of livclihood, IVe ha\"C ru add rranshull1:tnec al1d nomadislll.Tltcsc are il1 clfect a lo\\'-risk ["rm of capiral investmenr - Llr kss susceptibk toal1l1ual variarion than is dry t:1rtlling; mobile enough [() escape disastwus changcsin rhe I0C11 ecology; mobilc enough, also, to bcilitate tax evasion. That is whylhe largcst cOl1centrations of sheep 3nd goats hal't: becn fOllnd in ",hat are, inagricultural terms, rhe poorcst, the 1l10st risk-Iaden eIwironment5: an inrensivelvcultil'<ltcd arca can still also slIstain ;I small herdo

The Biqa has to be summed up not as one microccology but ratha :\s acollectioll of microccologies. The best accouIlt ()f thcse is a rnodern 3rch3<.:010-gical !icld sur\'ey (Martoe 1978). Bur thar roo, ho\Veva I1uanced its de5cript.ion,ho\\'cvcr alivc its author tO local vari:uion, is ncccssarily mislcadillg as evidenceti.lr the distant pasr. This is probably not beeause the character of the cnl'iranmcnr

58 lU. FOUR DEFINITE rLAC:E~~~~-----------------lias changcd 50 dramarically in historical Limes. Wc rcrurn to rhc subjcct inChaptcr VTII bclow; bur it is a fair provisiorial assurnption that ncither clirnarcnor any aspcct of me gcography has altcred so markedly that thc l'angc andnumbcr of thc microecologies would have bccn vcry diffcrcnt in Antiquiry or rheMiddle Ages from what is observablc toda)'. Whar has changcd, howcvcr , andchariged repcatedly - 50 that ir could not be accounted for by refercnce to anysingle environrnenral carastrophc or secular cvolution - is rhe subrlc intcrrclation01' diffcrcnt mcans of survival.

Thcse have not, of coursc, always bccn internally dctcrrnincd; rhe direcrionand nature of thc dcrnands made llpon the region from outside have also changcdfrcqucntly, The Biqa is 'Ie plus beau couloir de circularion entre le Nord ct lc

'Sud du Levanr' (Dussaud 1927,315); and me umbilical routc across MountLcbanon to rhc POrt of Bcirut has bccn 01' lasting imporrance (IX.7). But whcn ,for cxarnplc, Bcirut and Baalbck wcre part of a single Rornan ciry rcrritory,farrncd - ar lcast initially - by vereran soldicrs (Millar 1990), rhe cnvironrncurhad diftcrcnt dernands madc nn it frorn any rhar havc ariscn sincc (\'11.6).Indccd , rhis exarnple illustrarcs thc importam truth thar rhe ways in whichmicrorcgions intcracr and clustcr in the Mcditcrrancan are as importam as thcirdistinctivc interna! tcaturcs. Rural cornrnunitics havc frcqucnrlv maintained abroad conrinuurn 01' cconomic ncrivirics, shitting frorn dispcrscd nomadisrn ourhe northern stcppc-, and thc picdrnont tO highly conccm rarcd rranshurnanccaround thc ZOi\CS of inicnsc cultivation , altcring lhe balallce berwcen pastoraland arablc as and whcre necessary (cf. Sccrion 6). 'lhe dcsccndanrs 01' rhoscwho, :J century ago, wcrc among thc ícw cash-crop Iarmcrs in lhe cntire rcgionmay now be prcdominantly nornadic - or rhc reverso. JIl lhe central Biqa rribcsof bcdouin who wcrc oucc exemplar)' camcl nornads havc used rhcir wealrh topurchasc land - cvcn though thcir avcragc incornc musr, in rhc pasr, havc bccna good dcal higher than that 01' many farrncrs.

Ali this is a cIear reflcction of an unsrable , rrcacherous ecology. Thc fiucstwho survive are rhosc kccping thcir cconornic options opcn and rcvicwing thcirporrtolios freqllently. And that is rnost probably how it lus al\l'â)'s been inhistorical times: irnmcnse variation in spacc, from one microccology to anothcr;cqually il11IllenSe chronological variation, as individual microenvironments altersubrl" (or nO[ so subrly) or the hUIllan commllnities aS.lociJted wirh each adjllsttheir division 01' eftórt. Here, as in Greece, 'cach yCJr rhe l'armcr ma)' be iÚlningtor a differem production target, Irom a dinercllt arca 01' land, with a differcmlabour force and \Virh the cushion 01' a greater or lesser amOllllt 01' producc instore' (Halstead 1987, 85). A case like thar of the Biqa certainly hclps lIS rolIndcrsland how it has come about tl1at Mcditcrranean agricultur:d geographyhas nccn dominated sincc Anriquiry by certain cconomic Iabels '(salrus, highpasture; silva., woodland pasrure; arbustum, producti\'c orchard terrain; helos,marsh pasture or water-meadow, and so on). Yet tl\e Biqa shows emphaticallydut, for all this labeUing, whar matrers is nor the static formula bm the enrirespectrum of available strategies; and not fixcd points on the spCCrnlll1 nllt move-menr along ir. Flexibiliry is ali.

One case study is obviollsly not enough to esrablish our general view of lheMedirerranean environment; and the Biqa might after ali be dismissed as ~1marginal area (though cf. VT.3), at the point 01' u-ansition be\wee.n rhe coasrlandof rhe Medit~rranean sea and the semi-arid regions to rhe Easr. Bur rhe essential

2. :;OUTH ETRURIA,------------"'~ 59incohcrcncc 01' iis hurnan gcography, which secms [O havc bccn charactcristic 01'

the arca in ali pcriods, encourages us to look ar other parts of thc Mcdirerran-can , asking wherher a cornparablc degree of ccologicaJ fragrncnration is disccrn-iblc clscwhcre.

2, SOUTH ETRURIA

The major part 01' rhc modcrn Iralian provincc of Lazio, rhe rcgion of Romc,covcring Sourh Etruria and ancicnt Latiurn, offers another rcrnpting local casesrudy in Mcdircrranean ccology (Maps 3 and 4). Indccd , as a constituem ofwest-cenrral Iraly (lhe orhcr part being Carnpania , to rhe sourh ) it fcaturcs inrnany rcgionalIy based analyscs. I'art of rhc appcal of lhe arca to the historian isundoubrcdly that it lias rcccivcd a good dcal of scholarly artcntion; and this againincludcs a particularly thorough and revealing archacological survey, dcsignedto clucidatc lhe rransirion trorn a classical landscapc 01' dispcrscd dwclling» to amedieval one of nuclcatcd, dcfensive , hilltop sctrlcrnent - csscnriallv lhe proccssknown ao incastellamcnto (Potrer 1979).

Thc ropography of Latium has bccn describcd as a rccapirulation in minia-ture of thc char.icrcristics 01' lhe cntire península (Toubert 1973, 137). Thcrcgion ccrt.iinlv dispLws :l rcrnarkablc cornplcxiry anel divcrsiry of geologv, soiland rclief Broadiy it compriscs rwo largc volcanir complexos rhnr separare lhernarsh and shinglc (lI' rhc coasr frorn rhc lirncstonc ranges of the Apcnnincs anelthcir outlicrs. Thc more southcrly volcanic group, the Alban Hills, forms aconspicuous focal poinr for rnuch of thc region (V.1). Thc raiufall is abundanr,particularlv on rJ1C highcr ground; and thc volcanir ruffs are disscctcd by hun-drcds 01' gullies carrying pcrcnnial srrearns, many 01' which drain imo rhe Tibcr ,a major river flowing in a widc t100d plain berwccn the rwo clustcrs 01' volcaniccrarcrs. The surnmers :l1'C dry and very hor , lhe wintcrs quite cold. Thc r.iin ,bcrwcen 700 and 1200 mm PCI' annum over lhe greatcr part of the rcgioll,b.lIs Illostly in allttImn ~i\d carl)' spring. Some of the allllvial ;)nd \'oloni( soilsare agriclIlturally productive, and the ,uca has been intensivcly farmed sincc lheBronze Age \Vith a \\'idc: range of strategies suggcsred by the di\'Crsit\, of terrain:vines, olivcs or fruir rrces wherc the soils are bC.lr, cereaIs e\'crywhcre, animais inlhe \\'atcrlogged meado\Vs or the becch, oak and chesrnut \\'oods ()f rhe stcepslopcs, transhllmancc in slImmer r.o the high Apenninc pasturcs - ali theseexisting side by side oftl:n wirhin rhc minlltest regioI\S.

This local variety, reduplicatcd across the wholc zonc, makes it attracrivc t()consider the region as a unir. Thc cnvironment is not, ho\Vcver, so onliging.The heal'y qualiticaLions made above abour rhe fertilitv af the Biqa are appropri·are hcrc roo. The volcanic soils arc far from llnifórmly tertilc. Many are very thinand lIIHctcnuve of warer; orhers - :ll1d r.his is also true 01' t)le aJluvial soils - tcndto be 100 sticky and \Vaterlogged for the light ploughs which have bem CllstoI11-ary. Thesc ditticulties are compoundcd by hydrology. Thc raintàll is abundantbur \'aries considerably frOI11 year to year in qllantiry and distribution. It isnarurall)' highest on the mountains where ir is lcasr used, and in any casc tallsIllost ot1en at the end of the agricultural )'ear in torrents thar cal\ be el\ormouslydestrllclive. 50 the soils which might, with irrigation, be tCrrilc, and the \Vaterirsclf, are both available. But irrigation is exrrcmely ditticulr. ()IJ the ridges lhe

~

2

~~.c,

c

~'/)

]'"'~.n

"ې

v;

'"c,"~

2. SOUTH ETRURIA nlsoils are roo thin and dry; the slopcs are roo stecp; and thc valiey botrorns areroo wer. ln addition, the force of the run-oficauses soiJ erosion and rnaintains thestecp sides of the gullics, which separare 011<: localiry frorn another to a surpris-ing exrenr (cf. VllI.2).

Thc ropographical rnicroecologics thus crcated ma)' not bc as varicd as rhoseof thc Biqa , but they are each none rhe less disrinct. As in the Biqa, moreovcr ,pastoral can otrcn bc more attractive rhan arable farming. Pigs feed in the woodslln thc srecp slopcs: catrlc and shcep can bc grazcd DO thc wetlands in rhc winrcrand rhc high pasrurcs.in rhe surnrner. Full advantagc is rhus takcn of rhe rangeof cnvirourncnrs rnadc availablc by differenccs in altitude: the mountain pas-turcs, inacccssible in winter , come imo rhcir own when thc lowlands are ar thcirdricsr nnd rnosr prone [() rever.

In Anriquirv, ccrrain parts of thcsc rerrains wcrc indecd proverbial for t hcirugricuhurul intransigencc. Thc ROITlJns, invoking thc cnviroumcural dctcrrnin-iSI11 C0111111011 in ancierir culrurcs, attributcd the hardihood of rheir carlv gcnnJlsand soldicrs to rhe difficuliies of tracts like rhe Ager Pupinius, in rhe plain castof Romc. And ar rheir most extremo. rhesc local disadvanragcs o!" arable cultiva-tion cven lcd, berwcen lhe sevcntcenth and nincrcenth ccnruries, ro the virtualdcscrrion of rhe relarively flat and dry arca to the south and east of Rorne , rhcCampagna (a social, polirieal and geographical dcvelopmenr 01" thc highesr intcr-

. esr, to which I\T shall return in Volume 2).Archucological work has helpcd to claritv anorher aspcct af lhe instabilirv of

thc landscape: in historica] times lhe rivers havc changed rhcir n arurc and thcircoursc along rhc vallcys with surprising trcqucncy. Most of rhern 1101\' Iloxv insrccp-sidcd channcls thar are deeply cut imo a broad , levei flood plain. Flood-ing, alwavs ;1 porcnrial danger wirh Mcditcrrancan rivcrs swollen unprcdicrablybv wintcr rain , is thcrctorc rare in rhc arca today. Whcn in sparc the rivers tcnd[(J dig ;\ vet dcepcr (h'lI1nel into rhcir undcrlying dcposit, lsut condirions havcnor al\\'J)"s bccn likc rhis. Evidcncc IrClm cxcavation. has shown borh rhe murkedropographical ch.uigcs rcsulring trorn nvcrs ' shifting rheir channcls, .uid also lhealtcrarions in rhe parrcrn of crosion .md dcposition rhat have atlccrccl I'I'Cf\' strc.uu\'<1l1cI' Jl1d nvcr ílood pl.iin in this deeply dissccrcd aren. Thc pOlem')' or crosived;\lll.lgC and of lhe consranr deposirion 0(" 11111d through cndlcssiv repc.ucdílooding is mos! irnprcssive.

Such cnvirouniental murabiliry is also to be cxpccrcd - and is incrcasinglvbeing dcrnonstrat cd .- in orhcr purts of rhc Mcdirerrancan. Ir is a torceful rc-mindrr rhar thc vallcv íloors and alluvial cousral plains which Me todav 5U ofrcnlhe ccntrc of Mcdirerrancan population were virtually unusablc unri] rhe carlymodcrn period - indeed in most cases unril rhc rwenrieth ccnrurv - 3 thcmetu bc considcred in much grearcr derail in Chaprer VIII. Thc gcographer 5rrabohad alreadv noticcd in thc time (li" Augustus thar Rornc was lhe only (ir)' 011 rheTiber (Geography, 5.3.7). And ROl11e's floods wcrc notorious unril the 1890s.

111 thc case of Sourh Etruria , rhen, whar appearcd to be 3 rclarivcly cohercnrand comprehcnsible rcgion, with which rhe historian or archacologisr could use-fi.I1I)' op<!r:lte, provcs disconccrtinglv subjcct to environrnenral murabiliry. Thismutabiliry is, moreover, supcrimposcd on the type of rnicrorcgional differenc«thar wc havc already lound brcaking up the conceptual unity 01' thc Biqa. West-central ltnlv, toe>, has developcd highlv Ilexiblc and opportunisric responses torhc possibiliries of thc l.mdscapc. Polvculrure - mixed tàrming - is rhc tirst

8.

~...Q61""Q >-c oo Üg -gm C8. •E 18 ~

§j-oc~

oE.s ª 1t 2

t!' ~

I·r" ~I-~{j . I':"..J , ,~

J ~ ~x, o o

~E8:::'

c c

gl ..:o J .2..• .;;;

1 <;o S ~ o

Ec

Z . "" s.q .2 -.o' -s .~.

,"I ~ ~1 j J~Dd'

jJ ~', mil

~;1,~z~<""c<""wUJl:);=;;,::::>wSl~

~ ~~ g ~

J'··-·'f:'·-llrlr':.::i~.. j'<::: ~;;.: 1::1 k:, ~ t?J'

~§

-;:;.~::-õ.

".-l

'"o.":z

2. SOUTH ETRURlA 63ingrcdicnr of this responsc, ;} prcdictablc rcflccrion of thc variery of terrain. TI1(:sccond ingrcdienr is , as we have scen , pasroralism, which because 01' thar variervand irs topographical disrriburion , is closely intcrwovcn with thc differing forrnsof culrivation.

Bclow rhc walls of the hill-scttlcrncnr of Picnza, in thc more norrhcrly sccrorof Etruria, rernains 01' a Neolithic settlerncnr have suggcsrcd :1 precocious originfor pasroralisrn in the region, and cvcn for thc developed form of long-disrancccuvironrncntal exploirarion, transhurnancc (G_ W. W. Barkcr 1975, 146). Grainsof crnrncr , whear anel barlcy werc rccovered from a series 01' occuparion sires.Thc proporrions of Iivestock bones found were: 62 per cem shccp anel goats,16 pcr cem (arrie, l2 per ccnr pig, 8.5 per ccnt dog, and 1.5 pcr cent dccr. Thcminimurn nurnbcr of animaIs rhat could havc crcarcd rhese rcmains, and thcirprobable age ar dcarh, hcars a str()ng rescmblance to rhc normal rcquircrnenrs01' more rccenr pcriods: mixcd farming: a te\\' cattle for rracrion: a tew shcepgr':lzing round about rhe setrlc mcnt and killcd whcn far: cereal cultivarion ; shccpanel gO:l!S for milk nnd woo] -- \\'irh thc crnphasis on shccp. Not onlv thar ; rhesircs n1\15r, ill rhe Ncolirhic as now , havc bccn situarcd 1\',11 above rhc winrcr.'J!()\\,lim;, and rhcy could not thcrcforc havc bccn pcrmancntly inhahitcd. Inrcr-mediare bcrwccn upland and lowland pusr urcs, t.hev lic prcrrv 1l111ch on whatwould, in rhe ver)' diflcrcnt condirions (lI' rhe larcr ivliddlc Ages, again bccorncan csr.iblishcd rranshurnancc roure.

Thc conclusion rhat rhc Iong-rcrrn hisrorv of pasroralism in Picnza can silllpl)'bc 'rcad ofi' frorn rhc ropography anel J fcw archacological finds is nOI1(: rhelcss 10 be rcsisrcd. Therc has bcen J persistem scholarlv tcudcncy to l:Jy toornuch emphasis on a pastoral, pre-agriculrural phasc in thc larcr prehisrorv 01' rhcMcditerranean - a rendcncy that perhaps bcars rhc coiltilluing starnp of veryancicnr notions of hurnan prcgrcss (scc Scction ó bclow). Prcssure of populationis somctirnes invokcd as rhc dcrcrrnining tactor hcrc, as if rhe cnvironrncnrallocarion of animal husbandrv wcrc idcnrical to rhat 01' culrivation, Growingpopularions could supposcdly not alford thc luxurv of animais and rhcreforerurncd ti) agriculrllrc. In this cornplex environmcnr, t hough, lhe rang<: of nichesfor hurnans .md thcir planrs and animais is 100 broad for rhar argurncnt to bcrcadilv pcrsuasive. As we saw in rhc prcvious chaprcr , rhc rc.ilirv of rhc p.1stdclics srricrlv ccological rnodclling. Whcu prcscntcd with data likc rhosc fr0111Picnza, thcrcfore , wc should not invoke some familar general imagc - cirhcr 01'

.l heroic world of pastoral carnivorcs or of an 'ur-transhurnancc ' :lnricipating thcNcapoliran Dogana bv rnillcnnia.

111 irs simplcst forrn transhurnance involvcs thc seasonal rnovcrncnt of animaisfrorn lowland to adjaccnt upland and back; but in many places thc disranccstravelled are far grcarer, and the routcs raken by thc hcrdcrs and thcir animalssomctirncs beco me major thoroughfares rhar nu)' rcrnnin in use for ccnrurics,Thc similariry of pastoralism in Italy within living rncrnorv (O thc practiccs tharcan perhaps be glirnpscd in prchistory, and thar are rCLHi\·c.:I)' wcll known inancicnt times, can narurally sLlggeSt that rhis long-distancc [orrn 01' transhum-ancc has bccn a constanr of Iralian life. Bur our dcscription 01' thc Biqa shouldprornpt cxtrerne caution. The rnanagcrncnr of rclations ovcr cvcn the distanccbcrwecn low water-rncadow and snowlinc pasturc is a cornplex social and polir-ical rnatrcr, and ovcr long disrances ir is srill more so, ln landscapcs such ast!Jose 01' SOlIIh Erruria, pastorn./ism is an obviollS ingredielH ill lhe range of local

64 l ll. FOUR DEFINITE PLACES

:. possibihties. Transhumauce, in so cornplcx an ccology, is a ver)' ditlcrcnt nurter,. rcquiring particular social and econornic - and polirical - conditions (VI.7).

Undersranding how rhc microccologics work enables us to dístinguish thc rwo,aud to bc charv 01' rash assertions of thc continuiry or straightforwardncss 01'agrarian response. No strarcgy (;11\ sirnply be prcdicatcd of thc landscapc.

Eacb rnicroccology has its physical characteristics, which mal' be discernible ina number of differcnr periods by mcans 01' archaeologica! or documenrary cvid-l'IKC. Em thcir significance can changc radically berwecn onc pcriod and the ncxtrhrough altcrarions in the nerworks rhat bind rhc rnicroccology to its neigh-bours. A pasture in South Etruria mal' exist for millcnnia. Irs contribution to its

, locality will, howcvcr , vary cnorrnously as the animais on ir changc Irorn bcingrhosc 01' a local proprieror to rhose 01' a large-scale invesror trorn the cirv ofRornc whosc Ilocks are scatrered across southern Italy; or to those of a Rornanvcrerun soldicr with intcrcsts in J neurbv ciry; ar to those 01' rhe dependanrs 01'J papal estare. Thc gr3ss and lhe goars cornprisc 01111'J srnall parr of thc ovcrallpicturc

Pastoralism conccivcd ou thc grand scalc and munagcd .icross lhe lcngrh andbrcadrh 01' J pluralirv ofmicroregions is ;) porenriallv unitying torce in a rcgionas fragmcnted as South Etruria. Ycr it eould nor havc hclped to shape rhe par-rcrns 01' allcgiancc and COIltJU across rhat region in rhc abscnce 01' a strongccnrra] .uuhoriry. ln thc urch.iic pcriod , rhere is a clear diílcre ncc in settlcmentgcogr.iphy betwccn rhe arcas to rhe north and the sourh of rhc Tibcr, despirerhe sirnilarirics of the landscapc. As in the Biqa, scttlcmcnr historv tlIr11S out tobc a poor rctlccror of microtopcgraphy. Ultimarely, it was thc rise 01' Rome ,rathcr than any prcdominantly cconornic feature sue h as pastoralisrn, thar carneto wcld rhis arca into sornething approaching a uniry. That unity funcrions 011rhc idcological as much as 011 the ecological levei. ln rhe late ninctccntb centuryrhc simplisric cornparison of past glories with present dccay did rnuch to conccalthe illberenr variery 3I1d illsrabiliry of the bndscape: ir \\',IS politically npcdil'ntto belie\'c that hurnan acrivities bore the sole burden 01' cxpla1l3tion ((li' POSt-cbssiCJI dcreliction. Again, lhe political and cultural f':!ôliril's of ROl11c h:l\'cIhcll1sd\'l:s h<':l:n respuIl5ibk for rhe seholarlv w()rk thal makes lhe: rq!;ioll kcl5() 1l111ch morc intelligibk than l1lanv Olhas. Above ali, the fame anel suecos ()fthe inhabitants ()f ROl1ll' rhe (ir)', \\'hether as cOllqUl'fOrS 01' lhe \\'orld in the I,nl'Republic or as spiriwal ~l1idcs in the Middlc Ages, h3\'e had enormolls C(ln·seql1cnces for cxpectatiollS about lhe (ity's neighbourhood.

Ir is lO those expcLtatiol1$, and tO some extent to their ecoll()l1lic cnllseqllcnccs- rhe leisure architcctun: 01' the elile for instance, its bl1ying in 01' large quanrilie.\(lI' raw marerials troll1 tú 'llil'ld (1:\.4), and the l'l1hanccd attracrion 01' the cit)'fuI' mobile populatiollS (IX.S) - thar west-(el1lral ltalv owes Illuch 01' irs 3pparclllcoherence. Thc managl'l11cl1t of \\'ater in the arca shows a further response toROll1c's gravitational pul!. Although precipitarion is 50 much greater in aggregate,hcre as in tl1l: Biqa, warer control represcnts the way in which humanity canmost re3.clily rnodify lhe crwironment so as to intensify productiün, The hydraulicworks of the Etrllscan and, stilllllore, the Roman period - for drainage, storage,transportarion and irrigatioll - are cloqucm testimon)' to the po\\'cr of lhe(entre to subsume a variel)' of local effurts inro a wide-ranging sl'sr<::m (VII.2).

ln 50mh EtI'uria we em, therdore, glill1pse the interplay of external 3nd locallüctors borh 011 the fUllcriolling of Illicroecologies and (lll the \\'3)' in \\'hich rhc\'

3, THE CREEN MOUNTAIN, CYRENAICA 65------are perceived. The tcrrirorv of Tivoli, say, on lhe border berwccn thc limestoncmourrtain , and rhc ROlTI3n piain, or rhar ofthc Erruscan ciry of Vcii, can only bcfully undcrstood in rerrns 01' rheir rclarionships with influcnces from altogetherourside thcir own ccologics, as well as on the basis of rhe local variablcs rhatwc lcarned to crnphasizc in considering lhe Biqa (IV.S). ()f these outsidc influ-cnccs, rhe dorninanr one has been thc privileged acccss to thc sca and its con-tinuum of cornmunications. Both the Erruscan (entres and the Iittle settlcrncnrs01' Latiurn usually each had a scala, a bcach or landtàll-point, pcrhaps a rnarshyinlet bchind a spit of shingle, where contact wirh the world 01' Mcditcrrancanrcdisrribution might bc maintained. ln the long run, rhcsc wcrc overshadowed b)'rhe espccially privilcged roure providcd by thc Tiber and reflccred in thc status01'Rornc, rhe Tiber porr (lX,7). Bur if Romc 's ncrwork of influences perrnearcsthc arcas around ir, transforming and shaping thcrn in various ways frorn age to;)ge, that is not to say rhat rhese arcas C3n simply be considercd as an isolarcd,rcaciily dcfinablc ciry rcrrirory. Nor , in lhe abscncc of cvidcncc for interdepend-cnce , should \\'e bc quick ro postulare a primitivo aurarky (TV.7), To crnphasizerhar poinr srill turrhcr, und to sho«: rhat rhc pull 01' Rornc is only an cxtrcrncversion of a more cornmon Mcditcrr.uu-an phcnolllcllon, we rurn to rwo orhcrcase studicx. In rhesc, isolarion - 01':1 kind - is rnuch more apparcnt. Onc involvesa virtual island, rhc orhcr a real onc.

3, TlIE GREEN MOUNTAIN, CYRENATCA'I

In Wandt:ril~fJs in North Africa (L856) [ames Hamilton conrrastcd 'the rnonu-mental industrv offallen civilization with the slorhful hut ofvictorious barbarism'.Prior to rhc discovcry 01' pcrrolcurn, bedouin Cvrcnaica was a land ()f tenrs:rhcse are rhe slothfu] huts. As in South Etruria, the fallen ci\'ilization is that01' classieal Amiquity. :\nciclH rClllains are a rrolllincnt kature of parts or theCyrenaican landsclpe (,1vlap 5). 5YStell13tic archaeological researeh has revealedrhe colllplexity o( production anei the demity of settlement tiom the scvelllhccntur\' H.C. orl\\'ards: scvn31 importam cities, Illan)' brgc villages, seatten:dbrlllsteJds .- alllounting to ;) respollse to the potemial of the Crcell Mountain 'scll\'ironl11enr which \Vas cl'rtainly Illarkedlv ditrerelll froll1 :1.llvthing thar suc-cccded it arter lhe sixth cCIltur)' i\. D.

This particular sort 01' prosperity \\'as, ho\\'c\'l'r, fi·agile. An indigenous plant,local to lhe regi()ll. \Vas I(lr cx;lI11ple devclopcd in Antiquity as J highly speci;)l.ized c<lsh-crop - silphion. From the sixth eClltury R.C. this ulllbellifCrolls planl\\'as o. rcno\Vncd and valuablc COJl1ll1odity. S(;)rcc:, distinctive and costly, it hadnumerous culinJI)' and medicaluses. Its identirv rcmJins, ho\\'cver, an enigma tornodern botanists. The numan impact on the landscape 01" Cyrenaiea has com-hined \\'ith tlle heJ\)' dell1~lIld for silphiull to render lhe plant extinct, thoughir is not ctear preeiscly whcn the do.mage \Vas donc. The SIOI)' is instructi\·e.Silphiun is in some \\'al's a typical MediterranC3n commodity, AccidentaJ spceial-ity or a singk set 01' environrnents, it alters a highly Clrrracti\'e opportunity toproduecrs \\'irh wide horizons \\'ho C:ln auapt to the ad\'Jnt3gcs of particularlocalities. The agriculturalisls af Grec:k C)'renaicJ also specialized in cllmin:anOlhcr culinary/mcdie:ll cOllll1lodiry whieh, although not botanically so singu-Lir as silphiun, dcrivcd its value onl:' ti-alll its pOlelltiJI for rc:distributiOIl, More

0~~~t Il __~_

~ II ~--- ------<=;1, I\---- -- --::í~1--1Li ,1--- - --- --,I! : '.:11

\ ---

,··· .... 11\ ~l·.::::.-'-

C:íi:':::'J.i! :~-)p:~l·:.::! 1

1

1

1 t:\

. -'!'l -j , , . I~\.-.----------... z,····, 1; 11: ._ ... -

'i:!{\'::' li' 1\rl D/~" \ 'I 1-----

[. (.:.: 5.[111

,]i\- ~ o c

\'lliJ~~-=.·fUh~;1'.':""'.::.:.: .. ' 11 :1

1! r'\-----~--

tp' IOOilfl'm~::~llllltJIi I mU'i1 i : I~~~-~--<,<,~lJ. U..-L..l. : I llJill· -.,

q -~ ~

~ ~

f--'1--

"""l~~J

1(.ô<,ô8 g-s 4:c-º

(;

.~(;

"o.LVo

o

"".,~

'ai~ ~~ .~ ~z ~ -'-LU Õ Q)

cc i!J -6>-- r» oU li 3:

~f-

ZWU

t.z ,9. :

ID

] (>

ID

'8</>0

ª"RIE

i:-·1':'1l~

li~

~.

5n.2cv".c~'""':)c;'"

5noÕ-avc.

"'J.;:;c;~u'

l/l

C.

~

3. THE CREEN MOUNTAIN, CVRENAICA 67convcnrionally, ancient Cyrcnaica also produccd a notable surplus ar cereais,whosc value depended in part on the prccociry of t hc harvcst bv cornparisonwith rhose of rhe Acgcan.

Choices about primary producrion in this area, then, turn out to havc bccnthe result of a combinarion of vcry spccific local circurnstanccs 011 onc hand, andthc changing nctwork of relationships which the arca enjoyed with rhc widerMediterranean world on rhe orher. Environrncnral opportunisrn, morcovcr , cntailsa spectrurn of responses to environmcnral variabiliry through space and time.Against this background, maior transitions berwcen widcsprcad agriculrurc andmuch grcarer cmphascs on animal husbandry no longa appcar so carasrrophic.

Cyrcnaica is a striking region, and une which appears to bc isolated. Ccrtainlvir is separared from its African neighbours by descri: 700 kilornetres of it beforerhc Nilc delta is reachcd to lhe east , thc coastal srrip being only slighrlv morehospirablc rhan the interior; and alrnost as great a distancc to thc rclarivelv fertilctcrritorv 01' Tripolirania to thc wcsr Otherwise thc hintcrland is some half amillion square kilorncrrcs 01' Sahara, The homogcnciry 01' the descri margin canrnakc Cyrenaica arpear a unirarv fronticr zonc. But rhe appcarancc mislcads.ln tcrrns of clirnatc and vcgctation, it is as if a fragmcnr of some Mcdircrrancai,archipelugo had bccn uneasi.v wedgcd against rhc African continent - Mcditerruncan not just in irs charactcristic rainfall and tcmpcrarure , but in being a tanglcdand minutclv subdivided cornplcx ot intcrdcpendcnr cnvironrncnrs: plarcauxar difrcrcnr altitudes, intcrmonranc basins, dccp wadis. Ultimarei)' ir owcs thisintense rnicrofragmentation to its locarion , which, in rhc tcr minologv of piaretectonics, is a subduction zone (Bousquet and I'cchoux 1983). The seu irsclf ofcoursc provides a rcady nctwork of comrnunicarions: along rhc coast to cast andwcst, by way of chains 01' watering-places and srnall harbours on a provcrbiallvdangerous shorc (V.3), and across thc rclarivcly narrow scas (almosr a strair )to Grcccc and the Aegcan - thc island 01" Crere being less rhan 300 kilorncrrcsaWJy. Indccd, in lhe Rornan pcriod, Cyrcnaica formcd part of a provincc wirhCrere and was govcrncd (i'OI1l Gortys, jUS[ inland from the ports of that island'ssourhcrn shorc. Cyrcnaica irsclf, for ali rhat, is in anorher scnse insular in tharits coasral zonc is uncxpcctcdlv inhospitablc: lhe more productivc cnvironrncnts.irc rhosc turrhcr south and turthcr inland, whcrc thc rainfal] is highcr.

For Cyrcnaica (Map 6), with a[1 irs cornplcxirv, is csscntiallv a mouutain risingIrorn thc srcppe-likc tcrrain 01' the descrrs to the platcau 01' thc Icbcl Akhdar(sornctimcs known as al-ghaba, the forest, since its vegeration includes parchcsof evcrgreen forcsr and rnaquis ). Thc platcau is about 400 kilomerres long, ISOkilorncrrcs frorn north to south; and ir consists of a scries of rerraccs somctimcsreaching a hcighr of more than 800 rncrres abovc sca level, Thcrc is a riarrowsrrip 01' coastal plain, barely a kilornctrc wide , from which the first interrncdiarcterrace (to the wcst ) is accessible ro animal transport only through a very srnallnumber of prccipirous ravines. This tcrrace is a succession 01' wooded ridges andbroad wadis, Thc rnain terracc, thc tablcland , is whcrc the c1assical ruins, and rhcdeserred farrns of carly rwenticrh-centurv Iralian colonisrs, are to bc sccn; ir risesto a narrow third terrace ovcrlooking lhe arca of forme r serrlerncnt, Thc plateauthcn slop'cs sourhwards gradually down to thc stcppe through a belr 01' juniper(['ees, a zone ofrich vegetation [O which the sllphion ma)' at fir.lt have been nari\'e.

Therc are no permancmly flo\\'ing ri\'crs in [his karsric Iandscape. Thc only\\,;llerCOllrses are scasonal wadis, some 01' them (notably in lhe ,:oll1plcx oi" lhe

·."oo'",.

..s

" ~I.!.J

V)

;)./.:

" "I.!.J 8V) cs .

:<:

"C<:::.::I.!.J

h-QlJ..i..,..-=". '.:::.::

j~. !

!~\"l:-:;··.:(,

).

j1"fr·"~.I·: /'J...." .. , I'·',;1.'\\ I. -'__(lI' .'~)!,\ '\

~':'J::!:~-i1:/ 'Á'J:1;;i "K~

(\'~~~~0i: i i! i i 1"'\\\}.·....··:·,.I..·.·.. .! '., ,/i'iJ,,, ,:; .: '.

I·\·'[t/ ' .' li'/'.:.f·-nt· j" ·"t "(r,' ~,:II~~' 1\' .. ;/i:'1'~'~--",{", I, .. :Ik" _:~-~ '.'1 •. 1,·.·,I ','., -- 'Jl// ", ""~H-~.-- -l!l'iJ .I .:~I', r~> ~ •r í -, - ,~l,) f ;fl' ",!ô--=~'\:.• J • 7/;/ "

- ?\í~( .

\\jgi,tt

!

e]~

-go

- <. .~

~~ g- ~

11~i~~8'.3'hg8.~o~.~e-g~-r5~·.~e'~-5§~ ~,êV'12.V}~tl5§::':1' p~1[:~Ir:: i.:.'", li!'::j tjJ d

~0-"

~~ -o1\ 8 2~ , .x

~"n ri.LJ uco

"2Q)

rnQ)

> ~j ~<i' Ez ~LJ.J ÕO<>- iu

~>-zwU

0-.:.:.~co

'fll

~e=>

~.. ~<l: uu<i'zLJ.J •a<

.....:

:l ~g {)

~ -ge o. _ o

~tJ f~~ 8 ~ J ~

o Q[][J[l

:.=.,::;c;'-'Oú'-'.>

c"~§

"5D1::

""ê:;J

g",.).~

"1:;.;..

U

<O

C.

"~

3. Tm; GREEN MOUNTAIN, CYRENAICA--------------------- 69Wadi cl- Kuf) vc:ry dccply incised and íavouring nortb -sourh over easr-wcsrcommunicariuns. In the l11argins of lhe deserr srcppe, dew is a vital additionalsourcc of rnoisture. On thc terraccs ar thc Icbel Akhdar itsclf, rhe rclatively highrainfall (up to 600 111m per clI1l1LJI11) íecds I1LJf11Crous springs. Yet Map 7sho\\'show lirnitcd is rhe arca which benefirs frOI11 thar rainfall. Ir is also rnarkcdlyseasonal, in ;1Il exrrcrnc vcrsion 01' the Mediterrnnean patrern; and inrcrannualvariation is very high (local wisdorn prcdicrs OI1C droughr year in four ). Espc-cially in rhe less clcvatcd arcas wherc annual avcrage prccipitatiou is lowcr, rhefragmenrcd ropography cntails thar surplus and near-drougbt can be found onlyshort distances apart. As usual in Mcditerrancan lands, me patrcrn of rhe windsis borh dísrincrive anel crucial to cach :'ear's production. Winds Irom rhe sourh,laden with Saharan sand (qihh, rhe anciem netos: Roques 1987, 70-2) havecnrichcd rhe mineral contem 01' tl\;\ny local soils (d. Map 5) - anorhcr rcasonfor microcm'ironrnentalvariability. Yct t hc sandxrorms ofspring and aLltUIl1J1canbc disastrous ir rhe spring ruins havc ccascd carly.

111 modcrn rimes, bcduuin rribes havc competcd for rhosc north-south'srrips ' 01' lhe rt:giol1 rhat \\'ill each corurnand the Iull range of rcsourccs to bc

-round , in cast-wesr ZUI1CS, bct\\'cell high plateau and scrui-dcscrr. Mosr tarnilieshavc rnixed agriculture and pastoralisrn (carrle , gO<llS, shecp, cumels). Whcat isgrown for bmil)' consumprion. Barley aud straw are teci tu catrle: rhc rnajorirvof landowncrs have in rcccnr times 110t sold rheir harvcsr 01\ rhe rnarker. Burrhc rclarion bcrwccn .u ab!c and pastoral is more cornplcx rhan that, bccauserhc ccologies 01' tavoured spccies are \'ery ditferent, and suitable land II)r cachspecics is likclv 10 be scarrcrcd. Carrlc necd barley, str aw anel plcntiful supplicsof warcr: lhe nornadism characrerisric of other parts of Africa such as lheSudan is irnpossiblc in Cyrenaica. Goars are lcss particular in their dcrnands.but thc juniper forcsr serves rhcm besr. Shccp ar coursc necd good pasturc, andthey rnusr spcnd t hr wintcr 011 the sreppc and the surnmcr on rhe plareauCarncls w.inr shrub to cal bur can casily travei for ovcr a wcck wirhour takingwatcr.

50 how, given rhis divcrsiry, are animal husbandry and cultivation corubined>Firsr , agriculrure has bccn cmph.u ically a subsidiary activirv for rhe Cyrcnaicanbedouin , irs 1110St importam tasks C;\I1 be quite comfortablv fitted into evcn ase mi-nomadic pasruralist's schcdule . The move sourhward frorn plareau to steppedoto not rakc place unril Dcccrnher , attcr ploughing. The sheep may have bccnmovcd 01\ ahead with J porrion 01' rhe workforce; bur the majority 01' peoplerernain in the fJl11ily tcnts until rhe crop lias bcen SOWII. Sccondiv, rhc cerealficlds on both sreppe and plarcau are conccntrcred near major water supplies,

. so rhar even if catrle and goar hcrdcrs did not have to harvcsr rheir ficlds during, summer they would narurally arrivc ar thc SJl11e parts oe the rcgion in order towater rheir carrle. Finally, agricultural land can be used as pasture when appro.priate. CatrJe, goats, sheep al\d camel, \ViII all happily graze field stubble, cspe-cÍally to the nonh \Vhere ,thc alrernati\'e flora are (for them) unapperizillg.Acc<.:ss to so \Vicie a rangc 01' enl'ironmc.:nrs has rhe advantages of rcsiliencc tothe conditions 01' <1 bad yedr and the: jlossibiliry ot' mixed herding. The sCJsonalIllovernent 01' the Jllimals, 111Orcover, dovc:cails unllsually lIeatlv \Vith the raising01' 311 arablc (rol'. For the herd's presellcc in the ZOI\C where \\'intcr ll1uisruremhal\cés crop vield coincides \Virh lhe dI)' SUl1lll1er. The hcrd tl1m tert.ilizes thefields \Virh lllanure whilc.: these are unplanrcd.

VJ11 iJJ~'-fI -"r ';l" J: - ,\é: 5 ~ n.. / r

~~~~~'<ec il ( ':-1' ~~ F. ~'1i; ;-t '. ~~'!:';:11 ' /~ , "~'" -, ~ I

z; " ';'. .. '" WJ ':.. '\1;\1 [;tijj1i' _~1~ 't"e, . t:..:,~~rlj dJULX :.]"~":::::::::;'~ ~""~r,õ~;,r,:'~ ~ ""E"

~1·í~f.h{:,®1~I ~ 1êj _·~t:i::','::\:.>§ 2 !;Jftn:.~,l::~I}':\':J}(>~ '";t~\\,.:"-", ;;:w:. <Á"-8 <J:-c c> ~~--\.yL:~:.::.j 0<'1-.-." ~

~~Y;O~~""'''-~~'''s' ~~r ,_, "-""~~-.,...- <~ "''' ~f5y' R ii!

(',<-,.,.- '" ~gJ .> .- '( ,:. li• '~ / ~- ,.t,- _ "_,,, ~\ \ ) \, ~ :;.'f;-I \,,\\} '\( <iE '< /1/\,,*,, __, j • 1 ". '"; '/ /t; "',, \11 s "; I-= ~,'.J \ ,'I_~ ~./ '! Z~ 1'\ 1.' ((CO"""'l,<:"u 'w; :: ,1l '~-'-:3 c uN ;&) ••• ~ -/"'t~ ;;~? .<,

Il~í,l~d" 'c-':;,_ ("·.5hr c~ (z,:- I 'to .j[\",' ) \\1W,,,,,

\~-- l::, , <V\~)'':'~"'' I .., ~ '1..•..~\~~;(, '" ":~-D \.~-~;i. 10 '\3\~".~ o~"

§ \~~o -c ~o ~ .J:l~

~L.!.l

VJ

%~L.!.l

%~Cl::Cl::L.!.l

""eh•...•ClL.!.l

~

"ctvõi!..'2

~5ga. '~• c~ ::;

.- '"·2 ~o :>

.õJi Q.

I...

'~

<:

Ii::'.J

:2 Ec "2êo ~

:> -cc "c .5 '"o E E E E E E~ ê~~~g~L!l ª a'- 8_NNM"qV) "Cl} _ ., • , ei5 ~8~8~88 ~« L,f"J.-_NNM'<1

" .~~ ]~rr-Ilnl'TJ '"'c:

~ ':::,Hh -:-: ! L; -61:!

li LXjuLJL.d~j ~o

UI'c..'"~

], THE GREEN MOUNTAIN, CYRENAICA 71

Thc later twcntierh-ccnrury life of rhc bedouin ma)' hint ar rhe likcly rncans 01'sUI"\'Í\';11in thc pasr: thc cornbinarion of srratcgics rhc ucccssarv adaprarion 01'parrcrns of scrtlemenr and migration to a jumblcd mosaic 01' ecologies - thcsefundamental cornplexities have apparcntly not altcrcd grcarly sincc Antiquiry,despi te the varying portion of land undcr rhe plough, In particular, ir must bcemphasized that agriculture and pastoralism are (here as elsewhcrc ) dosei)' intcr-lockcd. The apparcnrly independent pastoralisrs are parr 01' thc socicty of rhccultivators. This is nor to sal' that the rwo aurornarically co-operare. In thc carlicr .fourrh century A,D. for insrance, Roman Cyrcnaica was period.ically ovcrrun bynornads or scmi-nornads from sourhern Nurnidia and Tripolitania. But suchantagonisrn is not incompatiblc with various forrns 01' inrerdepcndencc , some 01'thcrn quite subtle. On onc occasion rhe raidcrs are rcporrcd to huvc dcploycd5,000 camcls to carry away thcir boory. Turning frorn horscs to camcls nu)'liavc cnhanccd thc scriousness of their incursions. But t hc changc should abahe inrcrprcrcd ,1S a rcflccrion of rhc incrcasiug rnargin.ilirv of lhe t,lIld, bcyondlhe range of shccp and goats, to which the nornads h.id to rcsorr as thc íronticrs01' agriculturc wcrc advanccd by Rornan powcr (Licbeschuerz 1990, 229).Tlic propagation 01' new forms of production oftcn involvcs contlict bctwccnlhe innovarors and orhcr grollps. Thc groups may in addiriou bc dittcrcurinredalong crhnic lines -- as in Cvrcriaica, at thc time ()( lhe consolidarion 01' thcCrcck prcscnce, and again in late Ant iquitv Thc intcrdcpcudcncc bcrwccn r.hcIW() ccological srratcgics rcmains nonc rhe lcss s.ilicnt. .

Nor onlv the rnain fcarures of rhe cnvironmcnt , bur lhe Rornan rcsponse to iralso , 11,1\'ccontinucd to rnakc thcir mark on rribcsrncn 01' rhc pcninsuia. Modcrnccmctcrics srill rcgister thc gcography 01' classical agriculrurc. For 'burial' hasusuallv bcen on rhc surfacc, wirh rhc body covcred 111' a srone cairn; and ruincdfarrn sitcs are rhe besr sourcc 01' loose, easily workcd sroncs wirh which the cairncan bc construcrcd. Old collapscd cistcrns, sirnilariv, can bc cxploircd (or rhcirrich soil and rnadc inro pear and olive gardens ('1'1.10); whilc some of rheclassical srrucrures (rcnovatcd aI'ter rhc oil boorn of thc 1960s) havc againprovcd capablc of proper use, Evcn ir unused, cisrcrns havc rcmaincd a vaiuablcguidc to navigation in what is othcrwisc likcly to De a fcarurclcss landscape. Thcancicnr Grcck and Rornan roads are still habirually uscd for sc.isonal 1ll00'CnlCIHsof people and animais. Barbarisrn and civilizarion are lcss rernote rhun rhc anti-quarian , and Rornantic, conrrast 01' tenr and ruincd tcrnplc suggcsIS.

lndccd, that cornparison (with which we began this scction ) both rcllccrs aproccdural error and announces an irnporrant rhcrnc. 11', despiu: e.ulicr cavears,wc iakc Cyrcnaica as a singlc area - 01' thc order 01' 2,000 squarc kilorncrrcs 01'producrivc lal1d and a Inuch larger exrenr of marginal rerrain- it is (;115)'to .Ia)'

()f ir thar, for instance, it \\'as prosperous undcr the Batti:Jd kings 01' rhe archaicand classicaJ pcriods in Grcccc, or during the latc Rcpuolic and caril' Empire, andthat subscljuently ir wem imo decline. Yet the 'prosperirv' II'hich rh'H I'erdicrallriblltcs to 'Cyrenaica' in Amiquiry is an impressionistic gClleralizatioll thatbcars onl)' very inadcquately 011 rhe region as a wholc - rhe rcgioll as il is fàmilarin brge-scalc maps,

Consider first the outlinc 01' the stm)'. Thc socicty rhat c:mergcd dUI'illg lhefirsr two cel1tllries of Greek 'colonialism', \Vith the crcaliün 01' <1 nc\\' setrlcmcnrpacrcm al1d thc imroduction of Ile\\' productil'e aims Jnd Illethüds, cOlllnlandedby lhe end 01' the tóurrh century R.C. a surpllls equivalem to rhe yicld 01' several

72m. FOUR DEFINITE 1'\u.CES

rhousand sqllare kilomerrcs 01' whcar ficlds (Map 8). Thc key to this rapid sue-ccss appcars to h ave bccn rhc early harvcst time, a monrh carlier rhan that 01'mosr 01' Greece aud wcll betorc that of thc Black Sea, which became anorherrccüursc for Greck citics in rimes 01' cereal shortage (J3run 1993, 525-6). Ovcrthe folíowiug ccnrurics, the cconomy of the productive micron:gions of Cyrenaicaconrinued to yield surpluscs for rcdistribution, though individuallv they waxcdund wancd in prospcrity. An asidc in a legal rexr of lhe Rornan imperial period(1)iBc,.t, 19.2.61) rhus aitcsrs rhc r ornrncrcial cxport 01' whcar and oil. Thc inugesof prospcritv srill featlIrc in lhe writings 01' Bishop Syllcsius of Cvrcuc in theculy fifrh ccntury A.D., bur rhc dcnsirv 01' Cvrcnaica's tics wirh thc rcst of rheworld was grcatlv ksscll<.:d (Roques 1987, 409-31). Svncsius could otlcr as aplallsibk cxcuse for non -pavmcnt of tri burc thc lack of ships sailing trom Cvrcncto Rome AnJ thc bishop reporrs finding linle more rhan 3 day's journey Irornrhc Iv1cdirerr:llle3.11, country folk who h3.J never glirnpscd the seu and could 110tbclicvc thar it \\'3S o,bk to support lifc: rhcy llcd ar the sight 01' tried fish , rhink-ing thcm scrpcnts i Lcttcrs, cd. Hercher 1871, nos. 147-8). Towards rhc eud 01'thc miliennilll11, h owc vcr , rhc geographn lbn Hawqal Iound Barca and its ter-rilc pluin prospt:ring Irom su hstant ial (OI11I11Cr(Cwith orhcr arcas, bur cspeeiallyFgypr (tr.ins. Kr.uncrs and Wicr 1964, 1.62-3). Anel his resurnonv is corrobor-atcd nOI onlv by orhcr Arubic sources , but bv archacologv, which rn'cals aturrhcr and previouslv llJ1SUspCCled commcrcc wit h Sicily Irom perhaps thc latet cn rh (C n tury onward (Kcnnct 1994). Nor wcrc thc significam outside links onlyrhc seabornc or coasr\\'ise oncs ; due art cnt.ion ruust be paid to rhc Saharan koincand to lhe distriburion 01' goods - slaves, dares, cloth and rhe likc - ;lCWSS rhcwastc , along lhe routcs to the oasis of Augila or bcyond (Stucchi 1989; cf. Brctt1969). Quite rapid flucmations in ecollomic fortune, dcpcnding on eot1llcctions()f varving kinds in a numbcr 01' diflercut dircctions, are rhus a normal fc.uurc ofwhru appcarcd ut lirsr sig;ht tO bc a rcgion quitc separ;llcd trol11 lhe rcst (li" lhel\'kdit<:IT:lncln worh! and .ihou: \\'hich generali,.alions uf un:\111higuous scopecould satelv be vcru ur cd. 1\[ the e.llds ol ihc rransccrs of- t:colng,icll opp0rllll\itiesare lhe multiplc routcs t hat kad imo the descrt and the ports which opeu oniolhe \\'orld nf thc seu. Borh so!'!S ot 'g,:lle\\';ly' (I X.7) can bc fl·.ollized more or less\'igorlHlsh', ;1!1d lhe 1()rtul1cs (lI' rhc port s 01' Cvrcne , at Apollonin , or t hc inlandhasill ur Barca, ut Ptokl11:lis, havc Huctuarcd wilh rhosc of rhe chlslcrs 01' mier o

reg;ions iuland.Thc causes 01' chaugc in sue h an cconorny should not bc conccivcd iu ruo

slraig;htfór\\'ard a mnuncr. ln part, pcrhaps, bccausc of Ibn Khalduu's me mor-able irnugc rv il1 thc Muqllddimah (trans. Rosc nthal 1967, l.?OS, 2.289), rhcrransirion from prospcriry to dedinc has oftcn becn pn:scntcd in c:ltastrnphie tcrrnsand anributed sirnply to thc progress 01' lhe pastoralist. Adval1ce 01' transhlln1Jl1tsin rhc wakc 01' lhe first Arab COI1QllcstS has bcen hcld rc::sponsiblt for the

Map 8 Cyrene deploys its cercal surpluses, 330-26 !l.c.'Thosc to whom the city g"vc ",hear, when the whcat-shonage occurrcd in Greecc' is the

heading 01' an inscriprion probablv onginally from the sanetu"r,. of Cyrcne's parton dcityApollo. Thc \Vide horizons "r lhe eiry's gc.ncrosity are remarbbk, anel probably rdltel lhe!1ornul disrribmion ~alternS 01' the Cvrel1Jean eacal surplus. E\'en if this gift had no strings3ttJchcd, rhose \\'ho dClccll1ined the dcstin;ltions 01' the fruirs of Cyrenaean producrion, and\\'ho ('()ulJ disposc uf suc!l in.t1ueJ1rial LH'ours nn (his SL:.lk, slood to g;.lin cnormutlsly in

diplolll;\ric and political I'rcstigc (SEG, 'i.2).

.''. "!2.....,:r~I~1 t" QfiW")' <...~.. 1 .TI év~ .- ~' =

rJ: y'~' 8r -', >. ~-".'\. ~,.

\)

.' .- "-", - -O; r i~.~.,~fo··""'rcl!!" .. !;," .L '" '''''''''''~

_. 17r.::': .c,,,~,,,S!oz'

CYCI ~ fio 'c" DI: S \" 0\ .\,,","''<,1. -) os,,,,, !.)'"''''

,\\l'IOi \~~('J )~·1· (::./) J~--6 L f Slpl''llH'' <""r ..

'" I:'.i,,,',;,,,, Hh""" \. I"""I' . "'1"""'0 ','>;-<.' ... Dei'

,,,,,,,",,,1,,,,8 ···_,I?h,-J''''', ."". ".' '_J~"-...).\\yc,'nm

~."'''''''.(',,,; .

(/,'0. C, ) ""li'~l~~;:~I/'.~o.~.

.1 o. ~

11':1<1 ~~ ~\)

.... ri' ~~"\:,,:. -A-N• \. '" '. . ATO lHA' .'" / . r.··, '

!:,~'d"" ~:~ .D~v~·\' ~~ 0/;'»_' "r()lIllll~, _RHODE,S)' '---:/t

w:tt::=l One dlvi5ion of the b ~"" I;. , 1mar = 1000 m . 'ed,mnoi 01 corn ) '. :(:r'i' .

()

(."f?'._'J

\ '"·~~U"

I ~-\. "

~\\Jr;\.~omm:IlD

\~RETE.,,\oano

.. \··.•é\ "" ' .. "\.,.( .,'

oC~:0;

NORTH

~

\i

K' ....0.--.-\' :':..-\~.

<:I"".' f'.\ u'bo,ri.0;;;·;~I' ..'.f~-j· ,} \, ..., (:-'

l~;../ O ve F-::-

1H ~ /"~ )'A ~. -' ' '.\~ .-"J-~ [~:l~·(.~~. ,

-0. 'z.._??.f r' ' I. v'o 'J;' (.. ..

~~, (1.... '-\:". '"Jí'i) ,C ~,",o"J ."~., "'o~)'• <\, ~\..

fJ -.C:J I.···" .' (-;,

c-~ ~ ./":'\, J"c-.

\.~) P,,;)ról

;":

'-\H)"Pl:lf;l~

. v '"

=.,,',.

o

'-0,_,

;.',

'~ 1,',

74 rn. FOVR DEFINrrE PLACES -----------collapse of rhe North Africm export of olive oil (Fremi 1955). Thc invasion ofthc nomadic Hilali has bccn supposed to havc brought to a sharp cnd a period ofrenewed prosperity in the mid-cleventh centllry. Relations bc1'.veen irnmigranrsand narivcs ean now, however, as we havc already suggcsred, bc envisaged in lcssdramatic terrns. Ir is not simply a mattcr of shifting the emphasis awav from lhevio\ence of invasion and on to broad ecological matrers, such as thc dcsiccacionpotentially causcd by increascd grazing. For doing rhar srill fails to C3ptllrc lheway in which lhe nornads variously graspcd the opportunities pro\'ided bv rhcirnewlv oecupied lands. In order to gain 'protection rnoney' rhcy might enhancc theprospeets for agricultllfe in a particular arca, not destroy it. Some grollps mightbe employed as guardians of crops against other immigrant rribcs. Whcrc thcmarkets for animal productS werc in decline - markets sllstained by agricultural·ists _. ir was hardly in rhc rranshumant's interest tO cnlargc his herdo Pastorolisrs,in orher words, do not inevitably torce land out of prodUCUOIl. Thcv are more asymptolll t1un a cause of economic chang;c. Thc vicissitudes of agriculture: inCl'renaica have owcd as much to rhc sr.rcngth of central go\'ernrnellt as ro thc

activitics 01' omcls .ind gO:HS (Cahen 197:1).Thc \'ocabular)' of prosperirl' or dcsobtioll as applicd ro wh o]c gcognrhiol

regions should be sccn os parr of rhc rhetoric ar political aurhoriry aud centralmanagemcnt. (Ir was for instance favourcd by rhe Iralian colonists 01' rhc rascistperiod.) I ts proper application is only to spceific cenrrcs of production (Frornwhich , as in the Biqa, expansion is possiblc) anel ro thc enremes 01' a spectrul11of economic possibiliues. To understand how movemcnt along that spectrurn ispossible , the focus 01' analysis rnust bc sharpened, and thc interrelationship ofsmall-scalc phcnomena more clcarly held in view. Ir is thc frequency of changefrom year to ycar , in both production and distribution, rhat makcs Mcdirerran-ean histar)' disrincrive. That history I11USt therefore be founded on the stlldy ofthe local, thc small-scale - the specific ('definire') wadi, co\'<: or dtlsrer ofspringsand wells. But in rhe pursuir of that srudl' ir must never be torgotten that sllchtiny unirs are not crispll' boundcd ccllular entirics wirh their own desrinits. Theyare not definire in the sense rhat rhey have fixed bOllndaries. Rarher, rheir dehni-tion is always changing os their rclations with wider wholes murate. ln t.he caseor South Etruria, Romc prol'idcd the most obvious e:.:ample of 3 lInifving force:\t. work wirhin a region. Like rhe Biqa, C)'renaica h3S had irs Romes: not jl!Srone (entre, thar is, but several; shifting eeological foci thar ha\'e b)' no meansneeessarily been cities, that ma)' by no\\' h~1\'c Ieft few visible traces 01' theirsignihcance, and that havc not inevirably been consrr~lÍned bv geographical

boundaries of sea or desertoWhat is moreover true of isolated pockers of landscape, and 01' quasi·insular

regions on rhe larger seale, sllch as Cl'renaica, is even more rrue 01' genllinc

islands, set in the all-influencing sra.

4. MELOS

The small island of Iv1elos, in the Aegean, lics in a c1l1srer with thrce otherl'et smaller ones on the sOllth-western edge of the Cyclades. Ir is about20 kilometres long and has J surfacc area ofsome 150 square kiloJl1ctres. Unlikcmost of the other Cycladcs, it sits O!1 one (lf the 1'.1'0 bands of still actil'e

4. MELOS 75

vulcaniciry rhat stretch frorn the Greek mainland alrnost to lhe Turkish coastlinc.Volcanic rock rhereforc coverx around Iour-fifths of rhe island. Ar SOI11<':caril',r3!Se aftcr lhe end of the last glaciation, rhis rock would havc becn ovcrlain byIairly dccp soil. Bur the hill slopes have since bccn croded alrnost cverywherc.Scdimcnr has gradually accurnulared both on low-Iying inland arcas and arvarious coastal sitcs. At best , ali thar has rcrnained on high ground is a ver)' thinsoil cover or a laycr of loose rock. Most often, rhough, thc volcanic rock iscompletely cxposcd. Mcanwhilc in me valleys the scdimenr is now dissccrcd bvstrcarns.

This pattern of erosion and dcposition obviously has much in eommon withrhe geornorphology 01' the valleys in sourhern Etruria. Thc chronology is, how-ever , wholly diffcrent. Erosion sccrns to havc bcgun, not in late ROIl1Jn imperialtimes, as wc would expect frorn the Iralian cvidcncc, bur at thc end of rhc BronzeAge. And this process was more or IcS5 continuous from thcn on. It ccascdaround A.D. SOO - just whcn it was bcginning. in some ot hcr pluccs, Unril thccarly Middlc Ages, rhc lowcsr-Iying arcas rnust havc bccn Llrgely uninhabirab!c.But a chnnge in fluvial regime Irorn alluviation to incision opencd thc vallcvsano pluins to srcadv culrivarion. Whv rhis changc occurrcd is obscuro. Ir mightcouccivubly bc visualizcd as having hegun whcn Bronze Age farrncrs dcforcsrcdlhe uplands and cultivatcd rathcr too inrcnsivcly thc soil that they cxposcd, andthus looscncd - alrhough wc shall late!', in Chapter VII!, scc thar cxplanationsof rhis kind havc to bc rreatcd with cnormous cauciono I'criods 01' hcavy rainfalland scvcrc flood did not help matrers. Nurnerous hillsidc tcrraccs, artificially'darnming ' the rnoverncnt of soil down to the vallcys, rcrnain as witncsscs to thcstruggle of carly populations to arrcst that progrcss towards apparcnt disasrerOnly after A. D. 500 could the ccology have stabilizcd; and cven in stabiliry itwas not altogether cas)' tO manage.

Nowadays 40 per cem of the island's slIrface is bare rock, and almosr 80 pcrcent of the total is unllsed. Tilc lêrtile sail is largell' on rhe easrcrn half of theisland bUl it is very lIne\'cnly distributed rhere. Widely scanered tields Jndterraces are the typical modern farm holding - some indicarion 01' rhe scarcit)'of usablc land, and of the ditl1eulty thar has pcrennially rJced tanncrs sincecrnsion on the hills began. In 1975 eighry-ninc t:1fmers \Vcre askcd ho\\' longit took them to walk to their mosr distam pior. The ans\\'ers f3.nged bcrwccnfi\'e minutes and si:.: hours; the avcrage was r\\to hours. Yet disrance is nm rhe!armer'.> onl)' problem. Even \\'here there is good soil lhe uIl<.krlying I'o\canicrocks are pOrollS. Nor is the suppl;; 01' warer ideal in an)' use (maximum \\'inrerrainfàll a\'cragcs 450 mm anJ there is an interannual variation (lI' almost 50 percent; cf Tablc 1). 'rhe winter soil is therdore dry by Mediterranean standards.

Prospcns tór animal hllsbandry, jllst as much as lor agriculture, are dimin·ished b)' alI this. The onll' animais rhat can be kept in large nllmbers are goats;rranshumance is rare. This is in part because the distance that farmas have totravei tO the ílclds compels them to keep only a tcw animais so rhat the)' can beeasil)' tcnded close to the farmstead ar the beginning and cnd 01' the workingday. Ir is also because of the scarcity 01" pasture and the risks inl'olved in anymajor shift aIVav from mixed farming (wheat and barle)', vine Jnd olives, leg-umes ~lnd gourds, sheep and goats). At tlrst sight, therc!ore, wc h31'C here asil11plc isolatcd clllsrer of niches, exploited wirh tenacity and ingcnuity since rimeimmemorial. Meios might be typical of the precarious naturc of iv1cditerraIlcan

76 !lI. FOUR DEFINITE\l:.MCES

life ; ir might serve as an cxample 01' lhe most ordinary and obscurc backwarcr,whcrc rrudirional rhythrns J.nJ ofreu-repcated patrerns are casilv disccrnihle.

Thc ditiiculry is rhar the hisrory of Medircrrancan islands, marginal cnvirori-mcuts rhough in some scnses thcy may contain, conlounds cxpecrations 01'insigniticClnce that an analysis of the environrnenr 011 irs OWI1 miglu raisc. Thendrnirublc rcsenrch project 011 'the archaeology 01' exploirarion on Meios (Rcnfrcwanel Wagstaíf 1982) placcd considcrablc emphasis on the 'intra-sysrernic rcla-tions" of rhc island , in particular those involved in the prehistoric dcploymenrove r J widc arca 01' a scarcc local rcsourcc , volcanic obsidian. The 3SSUIl1pÚ0l1underlying rhe project was, none the iess, thar Melos rcprescnrcd a tuudameruallysclf-sutficicnr unir, isolatcd enough frorn thc complcxities of mainland svsremsf(lr rhe archacologist to disccrn the processes of hurnan organiz ation witb relat-ivc case. Thar assumprion is rcvcaled in thc dcploymcnr by Rentre«: anJ Wagsratl'ot' rhc /vklian dialogue of Thucydidcs (History, 5.84-116), which mighr havcbccu thougln r.ingcruial to the rcaliucs 01' life on Meios. Thcv irnplicitlv .icccprrhc idea rh.u thc Mclians werc naturally nuronornous and rhar Athcnian aggres-sir m cousriruted a suhvcrsion 01' thar aurouorny. Yct rhe Mcli.uix' stJICl11Cnt 01'this case i Hisrory, 5.112), \\'hich serves as an epigraph tu thc 1982 \'OIUlIlC, wasinte ndcc] bv ilS author, Thucydidcs, not to bc self-evident bur to torm pan ot' adr barc in which rhc Athcnians ' posirion - rhar there is a ccrrain ncccssirv to rhcaccrcrion (lf inllucncc hy lhe pO\\'tr UUt rules rhe sca - is designcd ulrimarclv to.ichievc a tarif\'ing plausibilirv.

Thc tindings 01' rhe rescarch projcct itself suggest thar thc vulncrabiliry ofMeles in rhc late fifih century B.C. has becn more rvpical 01' its long-terrn his-rory rhan has an)' quier aurarky. 111particular rhe rclatively high populations -high in tcrrns of a11)' likclv 'carrying capaciry' of lhe cnvironrucut - spcnk (lI'

;] rathcr ditlcrenr srarc of affairs, in which Melos is an outpost 01' the demo-gruphic aud cconomic dynamics 01' J wider world. Frorn the classical pcriod ,whcu t hcv bclieved thcrnsclvcs oftshoots of thc rnainland pcoples, to lhe caril'll10dern aa \\'hCll Lhc population sizc tluctuated with extrcme rapiditv (th;lt ()f

lllid-ciglnccnth-c<':llwrv l\lclos blling frum c.5,000 to c.I ,000 in JUSI a 1l:\V\'ears),the tÓrtulles (lI' the is\;Jmkrs l'cspollded to the \Vider mal'irime cCllltinuum. Meli3nasscnions (lI' politiC11 sclf-dctermin3tion do not rc.:pn:sl'nt the 110r111. It is ratherrhc (onflictillg pulls of the various olha regiolls \\'l1ose l11eeling-poim is rheAegean lhat havc given shape tO lhe island's history.br ti-OI11h<:ing ulluSUJllvquitt and remole, an arca sllch as Meios, 01' O!1C01' its cümponent microecologies,is aClu.\lli' more suhjcü ro the shiti:s and shocks (lI' change [h;\11 rnClnv mainlandareJ..\. More Ck3rly, C\'Cll, than the disrricrs 01' \\'cst-ccntr31 lul\', \\'ith rheir C3SVinrnCOlllH:CÚO!1S allel their pril'ilcged access to br-flung lletw(xks through theSllCCCSSof their polirical cc!1tn: 01' grlvilv, Meios o\\'es irs distillCtivc chara([Ll'not to the. 3ccidenls ()f its o\Vn geology or climare so mllch as to its relarioll-ships, changing over limc, with the fluid pattcrns ()f coml11unicariol1 in the midstof which it is situatcd.

IslanJs are pbccs 01' strikingly enhanccd exposure to inrcraction, :lnd are centralto historv 01' the r\kditcrranean (V.2, Vr.11, IX.2-3). Bur \\'hat is required 01'the r'vkdilerranean histori:lI1 is the ability to recognize, in pbces that art: notliteral islands, lhe insular qllaliry 01' being 'il1 th\: s\\~m' (lI' cO!1\l11unications. Iris this recognition lhat \\'c 11<1\'eno\\' sOllght to prol11ote i!1 fóur e.xal1lpks: :\11

5. 'LA TRAI\IE DU MONDE' 77

inland districr thar proves less coherenr and definite than irs physical geogrnphyinitially suggested; J. seemingly natural region rhat derives its varying eeologicalresponscs from places far beyond it; an isolatcd rerrirm)' which also rcacts to thcncrworks thar ir bdongs ro, overcorning still grearer barriers 01' distanee anelaridiry; and a real island, physically cur off and in thar sense totally distincr, yetnor in the least isolatcd.

5. 'LA TRAME OU MONDE'

'Whcn I want to understand Italian hisrorv;' ArnaJdo Momiglíano wrote, 'Lcarcha train and go to Ravennn There, berweer, the rornb of Thcodoric and thar 01'Danre , in the rcassuring neighbourhood 01' thc besr manllscript of Aristophanesund in rhe lcss reassuring onc 01' the bcsr portrait 01' rhe Empn.:ss Theodora, 1can begin to reeI what Italian hisrory has rcaily bem' (1969a, 181).

Regions like our lour 'definire places' are rhc ltJvennas 01' Medircrranean his-ror)'. For Momigliano, .unong rhc dennirivc fearures of I taly's pasr thar R.wennacl\capsul3tes are rhe prescnce of a forcign invader, lhe memory of pagan anelimperial Antiquity, and thc enduring force of the Catholir tradition, A sciectiveccwirollll\enral survey does riot rcvcn] cultural trair, 01' thar order. But our definiteplaces h:l\'c indccd introduccJ a nurnber of equally arrcsring thcmcs, and ourcxarrunarion ofrhesc in more derail should begin to revcal whar kinds O('cOlltinu-ir}', similariry, or generllir)' rnusr prcoccupv Mediterranean historians And norjusr those inrcrestcd in gcographical or environmenral history. I'ropcrly understood and inrerpreted, \lfe suggest, rhese mattcrs which seern so far rernovcd frOlllU1C associations of Theodoric and Dante may in tàct prove to be contiguous tothe historian 's 'traditional' spheres of inrercsr - church, sociciv, cultural litt:,polirics - aud indced somctimes esscurial (Q rheir propor lInderstanding.

Wt: sh:tll Jeve10p that idea ar the CllJ of this chaptcr and in Pans Three andFOUL MomigliallO's remark, Wt may at ulÍs stage add parenthericallv, is irself ofconsiderablc hisroriographic:tl inreresr. \Vhethcr a vivid jàçon de parlcr or speciesof gcnuine Rornanricisl11, his assertion th,u the particular colloc3tiollS of his-tori(;\II)' eloljllCl\t !\lOl1Ull1Cnts have al1 espccial significallce lor the historian ()f

Iralv puts him in a posiriOll - odd fi)r a Piedrnonrcsc - rarher likc lhat 01' anoutsider looking in at the Meditcrranean. Ir aJigns him (cmphasizing as hc doesrhe proce.\'S of travei anel the choice 01' vehicle) \Viril the mobile, touristic tradi tionin IVhidl the panicularity of p!Jet:s is so importam. As Momigliano IVas nudoubt \Vell J\Vare, his rCl\lJrk also associates him \Viril a norable sratCl\lcnt by J

lllllCh carlier coslllopolite, Sl Jeromc. !n tllt: prdàc<: to his rirst trans!arion of1 Chronicles, he advised mar inrellecrllaJ undersranJing \Vollld come onJy throughphysical travcl - tr3vel to Athens 101' Greek history, to rhe !nnian Islands lor thewJnderil1gs ofAeneas, to the Holy Land for the Scriprures (PL, 29, col. 401/\).As we sugg<:sred in Chaprcr lI, lllln}' aspects of modern Mediterranean histori-ography h3ve been grounued in the experience 01' the SCholar-explorer-pilgrim.

Om 0\\'11 particular 'rour' 01' four locaJities \VJS intended to promote a nllmber01' rclated ideas. Thc most illlpurrant by far is rhat the 'lZ;tvcnnas' 01' Mediter-ranean history are nOn!wl. Histor:' uf this rcgion, as we propose it, conCcrnslocalitics \Vl!idl have expericnced tht: equivalem in social and econOlnic n:lations01' rhe cHjuisile parricularities 01' culrllre and polities rh:tt are to be Savoured at

78 llI. FOUR DEFINITE PLACES

Ravcnna. l ralian history, likc Anatolian hisrory or lhe p3st 01' thc lvbghrch, hasindccd 'really bccn ' microlocal. Thc mosr pcrccptivc svnrhcsis of MedirerrancJngcography expresses the fact mcrnorably. Thc Mcditcrrancan world is 'a mosaic,

in which lhe. rnean size of each homogencous uniry is of rhc ordcr of reli kilo-rnctrcs. Nowhcrc elsc is rhc weave of rhe world's surfacc [Ia trame du monde] 50

fine - not cvcn 011 rhc islands of [apan, whcre , ir lhe clcrncuts of ropographicalunity are comparnblc, rheir conrent is infinircly kS5 various. (Biror 1964, ,;)

Gcographical survcys always have to wrestle wirh complcxiry. Frag!1lclltariollis cornrnon enough i11 landscapes evcrywhcrc. 13lH ir is rhc dC81-U to which ir issubdividcd , as Birot pointcd ou L, rhat distinguishcs Lhe Mcditcrrancan world.Indccd , rhis poinr mal' be taken a sragc furrhcr: rhc zones and localitics rhatjostle in rhe Mcditcrrancan can bc diffcrcnriarcd in rhc inrcnsirv of rhcir Iragmcntation (Mcdciros 1988). Thc naturc ofthc diversitv itsclf is divcrsc. In anygivcn 10c:1Ie, relatively more uniform tracts of platcau or plain may mcsh withrhc ulmost absurd variabiliry of rhe hrokcn ropography in which cvery SlOI'L ortcrracc of a vallcv-side , cach hollow, dum; and pool of a coastal lowland , 11);1)'

have its own idenriry.Ulrimatcly, thcrc are gcophysical rcasons for lhe gcological varicrx of thc

Mediterranean basin and ror the violencc (lI' its rclicf In thc layout of rhccontincnts.. this sca and its irnrncmorial forebcar lhe inland sca Tcrhys have hada placc which is hard to parallcl for irnporrancc and longeviry. Movcmcurs ofthc plates across rhe surface of the globe havc , ovcr ge.ological time, rcsultcd inrnany subduction zoncs, which havc becn replaced with chains of fold moun-tains. But thcrc are some grounds for thc claim thar nowhcrc clsc in thc worldspalacogcography has rhcrc been 50 cornplex or cnduring an cxamplc of rhe pro-ccss as in rhe Mcditerranean basin and its prccursors (VII!.2). 'The climarcs thatare knówn around rhe globc as 'Mcdircrraneau' are also rcrnarkable t()r thcir\'ariability ycar by year and scason by seaSOll. Hcncc the LXrrell1elv local (har·acter ot' the eHecrs _. on soil5, hydrology, rclieC - th.ll reslIlt troll1 lhe interpbv (lI'tectonic Illovements sllch as tàulring, earthquakc or orogCI1\', Wilh lhe 'ph)'sicn-cJimat.ic fórces (lf dcnlldarion', Alrhough tht:rc are orher cornhinaliol1s (lI' youngfold-ll1oul1tains with climarcs of this trrC, ir can !lc argucd that the dfecl (lI" lhephysic;d variely of landscape on the already capriciolls wcather is lIniqucly pm·nounced across the Mcditerranean (Houstan 1964). Anel rhar Illust, to an extem,be the result of the strangcly fraglllented IlUp of rhe sea itself - as microregional,in many arcas, as lhe adjoining bnd. SOl1lcthing of a n:ductio ad ,l'Í7.illnlrtl/1

of microtopography is consequenr.ly to be tóund arnong the Mcdirdranc'lllarchipdagos (VI. 11 ).

There is litrle rcason for the earth scientist to go bcvond discussing fi'actlltcdlandscapes in convenient macroregional clusrcrs s-uch as rhe Iberian ar Italianpeninsulas, or thelllarically according to onc or more of the principal physical\'ariables - mountain terrains, brsüc topography, littoral climates, and the like.In investigating Ia tm,me du monde, however, lhe hisrorian needs to press l-uI'-ther than rhe physical geographer. The second kss(Jl1 thar our fOllr cxamplcshave helped us comprehend is tllar the hisrorian mllsr examine lhe r.extme 01' rht:landscape in terms of lhe attcmpt to satistY hllman 11eeds from rhe resourccs01' rhe environmel1t. Study of ta trame will, like the lik 01' tht: nver\\'hclmingmajority 01' Mediterranean pcople in rhe past, bc 'close to the soil'. Ir \\'ill illl'ol\'e

5. 'LA TRAME OU MONDE' 7Yminuto artcnt ion to the varying consrrainrs lIpon production. Arcas whcrc agri.culturc is ar ali possiblc are oftcn lirnircd in rhcir cxt cnt and highl)' fragrncnrcdin rhcir disposition.