Homeless Man Recycling Their Past

Transcript of Homeless Man Recycling Their Past

T HREE

. . " Excavating "Globahzatton from Street Level

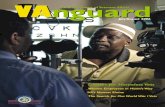

Homeless Men Recycle Their Pasts

Teresa Gowan

. . atin with his firefighter colleagues A San Francisco paramedic ts e gl . f)'et another call to haul

. kitch en H e comp ams o in the ftre stauon · · . f the gutter. "I should have . ·ed in vomtt out o a collapsed \Vll10 cover . ··I Some of the firefighters

. thing" Eyes sh1ft uneast Y· slipped hm1 some · t d not to h ear.

chuckle , o thers pre en f h h eless recyclers, Anthony. He h . dote to one o t e om k 1 tell t ts anec . n· dn 't 1 tell you we ran four mtsery I guess. 1 , laughs. "Put us out o , ;> Th t kind of attitude, that s

h · th the stray cats. · · · · a down somew ere wt l ' ·k·tng hard right before . I r When m WOI the whole point Wit 1 recyc,m~. ll drain on the public their eyes no one can say I m JUSt a sme y

purse.". o not dwell particularly on smellincss, Studtes of h omelessness d . . tage resultino- in a lit-

. . d acy take centet s , o . yet stckness and ma equ . d . dent income-generatton.

h lects to analyze m epen . l erature t at n eg k th eir work very sen ous y, d of his colleagues ta e . Anth ony an many d . . bility sh ould be my starung and I decided that work, rather than tsa '

point. . . . . . the roduct of several episodes of The material 111 thts chaptet IS p c.ve homeless recyclers liv-

. . h with some twenty-u . ethnographtc reseatc . ·ghborhoods. Followmg . . · . ,. ious San FranCisco net . mg and working m 'ar , h d the recyclers m the

. . ··t" e work I approac e my deciswn to pnot I JZ ' d . ther than through the

. h . ·cling com pany yar s, ra street, o r tn t e J ec) h h eless Using a combination of . t ing to t e om . service agenCieS ca er . . · g l got to know the

. . . t observation and informalmtemewm , parttnpan

74

HOMELESS :vl EN RECYCLE T HEIR PASTS 75

me n by working with them and spending leisure time together, as well as through recorded interviews.

Over time we climbed into dumpsters together, shared beer un-der th e freeways, and met up for occasional fry-ups in my kitchen. They brought me pans, sweaters, and jewelry from dumpsters and acted as my protectors in dodgy situations. I h elped with welfare and disability claims, giving them breakfast or a place to shower or visiting them in jail.

In this fie ldwork I focused pt;marily on th ose who were the most serious about their work, the most productive. And the interest was ofte n mutual. Approaching men as recyclers, and explicitly starting with a curiosity about recycling as work, I find that my work appeals most to those me n whose life-worlds suppo rt my· thesis. Men who a re investing recycling with a great deal of meaning, using scavenging to practice a specifically worker identity, respond instantly and enthusi-astically to my inquiries about the recycling life. Certainly some of the sample group, including Sam and Clarence, are champion recy-clers, carrying some of the biggest loads in th e city.

I initially framed the homeless recyclers as survivors, making a place for themselves in a growing tl1ird-world-style informal econ-omy. Yet the work of homeless recyclers makes little sense outside the context of tl1eir gen eral isolation and rejection by the broader society. As An th ony's comme nt suggests, the recyclers tend to inter-pret their work as an escape from stigma. But they do not escape, really. They are still homeless, mostly addicts and alcoholics, and few observers appreciate their efforts.

The "th ey arc \vorkers too" angle, while providing legitimate posi-tive images, came to feel blinkered . One limitation of doing etlmog-raphy with the ma rginalized is iliat it is hard to see the mechanisms of excl usio n . You can study the agencies trying to mop up the prob-lem, but you, like your subjects, are cut off from the larger social turns-institutional, economic, political-that provide the con text (although not necessarily the proximal cause) of their miseries. In Castells's terms, people like the recyclers are stuck in a stripped, decaying "space of places," unable to hook into th e "space of flows" of the information age.

In this paper, the instrument I use to hook into the big picture is nostalg ia, the nostalgia of the dispossessed for the lives they have lost. In each case, individual regrets and losses connect to the large-

TERESA GOWAN . . "Unlike many 7 6 ll " lobahzauon .

. ff by wh at we ca g d h ave n ot always . l shifts set o d Desmon . lf r scale sooa Clarence, an n aintam se -Americans, am , d h ·r attempts to I

homeless d destitute, an t el learned in more

\

· lized an l e systems . been margtna - . l bor" reflect va u . because th eir . gh "h on est a . f this ch aptei

respect th!O~ The)' are the subjects o b l. ation as loss, not us umes. lore glo a IZ or ..; prospero t helps us to exp . " than oth er p o

ostalgia for the pas . l or more '·deservm g

\ n re more mma' becau~e they a . Amen cans. . . inviting Its

'-- ·1s agaztn e qu1Z, ._, asks a Detat tn< f l . tory or the fast

first-century rnan. h dustbin o 11S . "Are you a twenty- ·r ou' re headed fort e h ir adaptabihty:

. ts to "see t y . . ised for t e hipster tal gef ture " High score rs ate pi a . •ou rely on no track to the u . and all organizauons .. ) e uide your

. You' re wary of any . •ou let expechenc g ·r ·obs Congratulauons. . ani zed religion . . .. ) d sanguinely shl t J '

. P government, Ol org 1 think on your fee~ an \ h t ln other words, gt ou ' . ou are ab e to of a vJrtua a . \ifesrvle chOices, y "d 1ces at the drop ., . nd resl el I friends, \ovets, ~he rwenty-fn·st century. aging its

ou' re ready fot t . . onorny, encour y . the mneu es ec . bl career paths, · · sptn on d1cta e Details puts a postuve brace flexibility over pre . c but only with that

young rnale read~rsbt~e~:-ity. The tone may b~i;~~;~cks a critical refere.~t opportunity ov~r JO f suoerf~irouic gloss, w . -k The message prevat s. Gen eration X ktnd o -~knowledgeable smn at~e smart, independ~nt,

nde r its raised ey ebr o - but you , dear reader, . You're money, baby. ~cyis for sadsack \ose::~ria\ enough to play to ;~~ngry, always with an

he~~:·~~~::~· r:~~:~~~~~~s ~~'~1~:~ess~{o~:~o;-~fe :;eb;~;:~:~~~h:rt~~~-eye to better oppo~t~~u~~s and stellar careers fo~ ~individualist can come economy offers qlll~ , u me the entrepre~euna. the Wild West of flex-

Lke the man wtth no na ' nd self-rehan ce 111 est. I roving his courage a f1led in into his own, p . f ntrepreneurs p ro . . r Sill The kmds 0 e d . the qUIZ, ible capita I : . b yish escapism. . ors celeb rate 111 f

Much of thiS IS o . th e unattach ed warn e at top-tier colleg~s, o th e magazine are h ardly. ns of vital contac~ ma~ rent kind of risk tf you wh at wi~h their tellt~~~;~amily memb ers.lt IS ~\~;~~s wh en things are not h elpful mvestrne nts . Mom's apartment bu . can return to managmg more margina\i.zed An~e;

wo6~~~~:~~·ty-ftrst-centu~ :~~~~~i~~~;! ::~e~ve _of ~~1:;,r ~~~~:;~~~~.~e: ans? T he writers~~!: vorK"er, migrant farm \alb. f yet the insecunt)·

c -=b ·gasasex'< dlr or t1te , · flexible em dd. t panhan e ' uve 1 crack a 1C , a1on e a h ome ess

H OMELESS MEN RECYCLE T H EIR PASTS 77

mobility, fl ux, and fragmentation of Details' "nventy-first century" is far truer for the poor than for college-educated professionals. Broadly speaking, the lower you go down the economic scale, the less stability you find, and there is nowhere in America where the basic conditions of everyday life are mo re volatile than on skid row. In the public soap ope ra played o ut endlessly in skid row stree ts across th e country, only continued poverty and disappoint-ment can be relied on . Devasta ting stabs of ill-luck become mundane, and for those witho ut sh elter the knocks seem to follow faster and harder. Any time, almost any place, such naked lives lie o pen to predators biological, criminal, voyeuristic, bureaucratic. Pneumonia , arrest, AIDS, robbery, or the official confiscation of those personal effects carefully n ursed th rough the wilderness, maybe even murder: any or all become possible, even likely, for a pe rson reduced to the status of h omeless derelict.

Indeed some homeless men respond to the unstable conditions oflife on""' -~~----- .. I

the street with a remarkable fl e_xibili ty. The bastard brothers of the entre-pre ne urialt echno-yuppies ta rgeted by Details, su ch twen ty-first-century 1

(nineteen th-century? third-world?) have-nots adopt a "hustle r" mode of homeless life .2 T hey improvise their daily needs through combina tions of 0 panhandling, plasma sales, selling the Street Sheet newspap er, dumpster-div- 1

ing for things to sell on th e sidewalk, prostitution, using soup kitchens and 1

other charity organizations, pe tty theft, recycling, selling personal posses-sions, and small-time drug dealing.

The "Hustle r as twen ty-first-century man" fi ts the perspective on homeless workers developed by David Snow and his collaborators.3 They describe the money-making strategies of the homeless as a set of improvisations fo r sur-vival, a constant ad-Jibbing for daily needs. And much of what they have to say about the unpredictability and constant crisis of homeless life rings true in the lives of the men featured in this chapte r.

Yet man rarely lives o n junk and booze alo ne. The stigma, assaul ts, and casual in_s~ts of street life knock away m ost eXternal refe re nts for self· respect, making the_ prQject to be someone mor e crucial tban ever. But what ·n of someone feels like the real you? That depends in tl1e main on who you

already are, on who you have been before. The homeless recyclers featured h ere-the "pros"- are most reluctant

to see themselves as playing the system. Instead , they stride across the city, working hard and fast. Usually following esta blished ro utes and stopping places, they sort their findings into great bags of bottles and cans tied on to their shopping carts, heaving up to two hund red pounds to the recycling companies each run. T he most strenuous toile rs treat themselves as beasts of burden, ha rnessing themselves to pull two la rge carts at once. For o tl1ers i~ mo~mportant to use th eir work to reconnect socially with the non-'!?meless, or to assert th eir claims to public space as legitimate trash work-

78 TERESA GOWAN

. 1 common is the resolve to turn their backs on

l ers. But what the pros hokl~du r f s they try with all their su·ength to ere-the painful boredom of s ' I row I e, .a

-11 "d t" ·n their own eyes. ate lives that are su ecen I . In comparison with h omeless

For these men h ave no t always bhee n podoL share much more uniformly d dealers w o ten to f street vendors or rug ' . . y of the pro recyclers haYe su -

d . , .·shed life hrstones, man d' marginal an 1!11pO\eii d I earlier lives they were long- IS-. d · ·ncome an status. n ' . fered massrve rops m 1 . . . soldie rs industry electn-. . d kers mecham cs, career ' tance truckdnver s, oc ' . . f l had unionJ· obs, and most d d I' dnvers Many o t 1em cians, welders, an e Ivery '11 : 1 d t h ealth benefits and some degree of those wh o did no t were su enut e o

of job security. 1. 1 d . 1 a compound of poisons equal I. 1. a ·e gone c rsso ve n 1 Those ear 1er rves 1 ' . . . . ·a! context of exc u-n lace \.Ylthm the cull ent soo .

Parts unique and commo p . turnings surmountable m . 1 . misfortunes o r wrong sion and mto e i ance, Tl . rable decline of the recy-life senten ces 1e mexo kinder times now serYe as ~ - d nd multiplied with j obless-

" , · Jce the 197os has r eacte a . clers' prospects SI~ l" despair hallucinations, myopias ness, family trageches and unrave mg~, ·cera~ion ·connections to insti-

b 1 self-disgu st or mcm . d d born of su stance ove, ' . . ·al fall have corro e ld v them from this dramauc soci tutions that cou sa e ble fo r day-to-day survival. and crumbled, leaving them to scram . bly overshadowed by their

.1 h 1- of the pros are 1nescapa 1 Yet wh1 e t e 1ves . . . . the ir time spent in hust er . d h y do their best to mmimJze . immediate n ee s, t e . . d tion in favor of the peculiar d I Ia)' down then espera b-mode. lnstea t 1ey P 1. th eir maior means of su

f · · d hard labor Recyc mg, as :.o f comforts o routinize · . 1 mic floor the bare bones o nl}' an essenua econo , sisten ce, becomes no t o. . d celebrate the rou tines, produc-survival, but a broad proJect to I ecover an . . . d r d . ty of blue-collar work. .

UVIty, skill, an so I an . ali ty from sugma and to ere-The efforts of the recyclers to carve o ul t no In: is b)' no means reflected in

f th nomie of unemp oymen , . 1 ate routine rom e a . . . l melessness. The vast socla . 1 f h cademJC hte ratm e on l O . the mam boc y o . t e a d . g on th e failures, sickness,

I . d . 1ates the tiel ' convergm . welfare mac nne omn '- I ""'-""--'·vidual This perspective . of the h o me ess mm · or cult ral mcompete n ce - . 1 ' text o lhe vast increase in home-~ "'-" "b k ts t e broaoer sooa con . tfierefore rae e . I authoritative research proJects . h 'd sevenues La rge-sea e . b Jessn ess smce t e mi - ·. 1 thodological individualism Y

on poverty are usually _seduced ~~~to ~~~~~e~~eir bread and butte r. the government agenCies th~t c~JJ-s~ale ualitative research is that on e does

One advantage of cheap, sm a_ . . q Th refore instead of using my d ·k 'thin these hm1tauons. e ' not nee to wor Wt th d ninant theories on h ome-. h h homeless men to test e OJ . . 1 spothg t on t ese . '11 mr'n ate their relationshipS Wtt I h · ·ounds I use 1t to 1 u lessness on t eu· own gJ . ' . h · in America, the world outside the

the bigger picture , the piCture of cl an g gf t ... e l1uge shake up we call "glob-h 'd · t d 'g up loca traces o 1l' - -

brackets.~ IS od. I h U "ted States as a systemic turn awayTrom the alization/ expen ence m L e m

H O :vtELESS MEN R ECYCLE THEIR PASTS 79

Keynesian social con trac t among government, corporations, and unions of the postwar years toward the contemporary period of deregulation, welfare-state dismantling, and union busting.

_!f we take g lobalization to mean the transformations of locales by processes instigated o r maintained from outside n a tional borders, the United States has been a t the center of vario us forms of globalization for hundreds of years, as bo th a site and an agent of raw collisions among Europe, Am erica, and Africa. Today, in the richest and most powerful nation on earth, this new "globalization" does no t represent a new shatter-ing of the integrity of the local; our "locals" were already globally conn ected, expansive, reflexive. What Americans are experjencing is instead a g radual

"t re placement of the previous military, Keynesian form of globalization with a fresh neoliberal coalition, one representing ch anged forms of capi tal, dif-ferent sensibilities, new winners, and n ew losers, as well as a resurgence of traditional "conservative" discourse.

Conservative theory defines men like the recyclers, able-bodied single ~n, as high-functioning deviants in rebellion against the market. The solu-tion, say the rhetoricians of market freedom, is to force the dependent poor to adap t to the current economic structure by removing the safety ne ts that guarantee their subsisten ce. Severe penalties for crime will ensure that these newly stimulated energies toward subsistence will be channeled to legitimate activities. Only then will such men be forced by their need for subsistence to learn new skills, or to take jobs at wage and status levels they might previously have found de meaning.

Conservative policies have been put into practice at all levels of govern-ment over the last ten years. Financial entitlements have been transformed and safety nets removed, culminating with the 1996 abolition of the sixty-two-year o ld AFDC program , and the devolution of responsibility for the unemployed to the local level. States are sanctio ned with the withdrawal of federal support if they do not institute lifetime welfare limits.

Local governments increasingly require work in exchange for the bare subsistence a llowed to prisoners and welfare recipients. The number of wel-fare recipie nts in compulsory work programs is expected to reach one mil-lion within the next few months. 4 As of june 1997 the re were nearly 3,0oo "workfare" workers cleaning San Francisco's streets, buses, parks, and hous-ing projects for roughly one tenth of the pay of regular city employees. The new welfare laws could add up to 25,000 more workfare workers within the next two years.5

Enti tlements to freedom of movement have a lso been withdrawn. While a million and a half men and women swell the penal colonies, the space out-side is mo re subtly resu·icted. All over the United States public space is being redefined both fo rrJ!ally and Triformally as private space with selective access fo r people who do not look poor. New downtown developme nts use anti-

·\ ~ \ ··> ' ; ~~ u 8 TERESA GOWAN "' \ ';- • .

o I· '' . ss o ln ~ ' " br "space to pedestnan.a~ce h~~eless architectu~e ~at close~ o ff n~~m~~s are encouraged to bi:~wse and the sam e commercial stnps wh ei e co cited and arrested for en cam p-!. ger h omeless people are m oved on, t ,,'"Quality oflife" offenses n ot In ' f dom of m ovem en . . mak t" o r "obstructing ree . ted all over Amen ca, -m en ·on h ave been reacuva ) .II alto enfo rced since the de pressi . ( I ping urinating, and so on l eg . b ·c human funcuons s ee ' Ing many asi . . .

·c1 7 , nt was mltlated those ou tsi e. . . f" uality of life enforcem~ . . -The San Franosco versiOn o q kJ dan 's admimstrauo n , start d - Mayor Fran , o r . d to

b h "Matrix" program un ei . h 1 ss people receive ten Y t e u de r Matnx, orne e ""d -ink

ing in August of 1993· n c -offe nses such as "encampment, I -d 'tations a year t O I bl' , o r "obstruct-fiftee n thousan Cl 1. " "urinating in pu IC,

. . bl' ""aggressive panhand m g, , official high-profile m g m pu lC, " Wl 'le Matrix's status as an r h ing freed om of m ovement. . 11 rminated in 1996, the ticketing po tcy as

\itical campaign was offioally te . . . $76 rising to about $ t 8o and po . ted The nne fo r the average o tatw n lS I 'people are unable to pay pers1s · . id Most h ome ess

8 an arrest warrai~t If left unpa . them with outstanding warran ts. th ese fines, \eaVlng thousands of

OSTALG IA O F T H E DI SPOSSESSE D TH E · · 1d . b ' hical particulanues, ai

Th ere are so m any mediating in~ti~utioi~S;, l~;:l:~ation" or "neoliberalism" . ks of fa te lying between the tor ces o . g . le causal line from struc-

qlllr ·ndividual. It is ha rd to jusufy a simp h . dustrialized world and any one 1 d ' Yet across t e m tural sea-change to indivi~ual Jsaster. increased corporate mobility across th are su-iking correlations among d cy and the return of mass

ere . rtical ascen an ' . . d 'ffi national borders, conservative p o I ts The conceptual and pohucal I -indigen ce, bo th on and off the str~e ~ausal relationship between the huge culties involved in actually provmgsol 'ts exploration. Othen -vise we have

h ld no t forec ose I d ' per-c\ the person al s ou . r d some times degra m g, ~~thing to work with but the ~econtex~l~ : ; the social welfare institutions. sonal details revealed b~ the dtsease m~s ~e concept of nostalgia. Kathleen

The tool of exploration l use here lace oneself in time and place, Stewart defines !!ostalg_a as th~. ~tt~:~~~~ ~o th e alienation ofJ?2s~o~e~n creating "an in terpreuve space m d ' ""eren t forms of nostalg~a WIth m . . · n between two Ill' -~· c 9 She draws a disUncuo He.

"la te capitalism." I in the cultural landscape d· from one P ace . . . . it depends on whei-e y~u sta~1 ·_ . n of a ure present that r~d~nnages

nostalgia is a schizophi-entc :;<-ht.latauo . . ·. a ; ined watchful desire t~_frame -for their own sake; from an ~ther plac=~~~~?'"\V<rfli:-to make of the P.~·esent ~Uifalp-;:esent ~n relatton to an ropriated, refused, disrupted ot- made

I" '-1 ob•iect that can be seen, app a cu tura ~

something of."

HOMELESS MEN RECYCL E TH EIR PAST S 81

Stewart defin es th e first kind of nostalgia as the act of taking possessio n: "He re, individ ual life narratives d ramatize acts of separation '"(fre·edom , cho ice, creativity, Imagination , the power to model and plan and act on life)." 10 In such a way the disappearing blue-collar lifestyle mourned by many h omeless recyclers is appropriated as kitsch in front o f their eyes by pseudo-Bohemian multimedia programme rs wearing vintage work shirts with 'Johnny" o r "Ray" sewn on the chest.

In con trast to this fi rst nostalgia with its power to choose, to freely appro-p ria te, Stewart presen ts her "other" nostalgia, which might be called the 122stalgia of the dispossessed . The "others," wh o live away from the highways of power and self-de term inatio n , experie nce nostalgia as a "painful hom e-sickness," which aims at "the redemption of expressive images and speech ."

l Those deprived~ former 'tertain!ies and. thrown into ch <:los a nd loss use nostalgia as a way of p1aci'fig themselves inside a surrounding world which - -makes sense. 11

- As a collective a ttempt to reclaim a past world, nostalgia can sharply point up the places where a person 's life-turns most clearly knit into a bigger fa b-ric of expe rie nces com mon to o thers in similar social locatio ns. For each of the recyclers, the past is a primary referen t. Al though their pictures of the past are bo th similar and different, th ey all see th e present in relation to how things "used to be." Each of them makes a life on th e street where he can make use of skills, habits, and ways of thinking learned unde r quite dif-ferent conditions. In this they are no di fferen t fro m m ost o f us. What is less commonplace about the recyclers is the massive changes in th eir social standing between the n a nd now. Stigma a nd extreme downward mobili ty m ake the m favor the past wi th the intensity of dying m en.

Stewart's "nostalgia o f the dispossessed" describes h ow I unde rstand J!:!s_ attempts of the home less re2;Ie rs to recreate f<trn.iliar worlds oytof the dis-

~rientation andde~ton of life._§ the 7treeJ. They assert ;a lues and life-ways drawi1 t rom the past as bo th critinue and shield against the alien land-

'--'\./~ '-"- ...... scape of the new, that la ndscape we attempt to con tain and describe with the encompassing ho t signifie r, "globalization."

!2!_ the pros, the curre nt version of globalization feels differe nt from the Pax Americana of their pas t. This version has n otxace for the m, and con-"- ~ ...... _ ..... sequently appears as a collect~. a 1en i'()rces. xperien~baliza-~ -": ~~-...__......,.., ... uonme-all a bout subject position . For the purp oses of this chapter, I focus on three of the pros, Sam , Clarence, and Desm ond, taken from a broader fieldwork sample of twen ty-five. T hey are not composites, bu t discrete indi-viduals who happen to sh are certain histo ries, sensibili ties, and strategies with others of the group.

As they m ourn and try to keep a live the worlds of the ir earlie r lives, the particular nostalgias of each man po in t u p par ticula r elem ents of the shif t

E RESA GOWAN 82 T . -ld der. The h omeless

l.b a \ new wot o r d . nism to the neo 1 er . b deindustrialization an from Keynes1a k S 11 has b een marked fo r ltfe y ~Clarence h as wit-ex-manual ' _vor ' e r -at lo ·me nt. The hom eless _Yete1 an -· rovided by the decline 111 secLll e em_£ )_ I . nt work-creatwn program p ----ale

-!;!~.:::..:-:-,.--:a:r:::--~ -s closing on t l e gta . Desmond lamen ts -nessed ~o' . ' ) d th e lom eless ex-com·tct - d b)' the War on the postwar milttai)- . n working class rept esente

1 Af -·can Am e n ca civil war on t l e II - . Tiru~s . _

Ou FREE· SAM ' T WJl L SET y . .

\\ ORh. - . _1 c.f· s H espenthis . -· n in hts em Y u ue · ..

Sam is a m~scular, t~ci~~~~~~~~~~:,:~~r~~:ying a lot of footb~l;~no~:~~~1:~r~ youth working on h:s ~ l hoo\. H e never saw th e need fo a highly

ried s~:ii~ghtc~~tft~~~~gi~ s~is m ech a nic1al ~~~~~tgi~t:r~~~ni~~~;~: repairing

says, . ld" down a co up eo 1 , d and th en skilled mech antc, ho m g . before he becam e unemp O)e '

d . d stria\ machmes trucks an 111 u · · \lv . . . . h e works conunua , , hom eless. ld sports mJunes, but K ing his

Sam 's knees ach e from o d d rarely stopping to rest. ee~ h . ·n two h eavy shifts every ay an d vn a nd leaning h ard m to t c

putung ' h road h e steam s along, h ead lm d cans he keeps his eyes on cart on t e r As he picks up bott es an O n e of th e less weight of the recy~ m g. . into th e p roper category. "

( rung each ptece · "R bocan . his work, ast so h shares Sam 's turf calls hun o l or ted because vigorous recyclers w o h ave his recycling alreac y s ' B ing

Fo1-Sam it is very important to < h u·tne a t the recycling plan ts. he . ' · end n1UC \" than e IS

h e does n o t really ltke ~o sp h o are less obsessively '.vorkah o I tc b" is of anY . - und homeless peop e w . . . o the r recyclers on t 1e as . ai o b th -s him H e assumes lazm ess m k - clers are particularly sus-

~e:~~c ~est~;aki~g .o r excessi~~h~~~~~Y~:~~\e1

~~rd me after a"b,lac~:~~~~ct~1~~ t "I just don t want any o . vi th the two of us. l m . PI eke . v h ad tried to initia te con,versauohn ~- for fun . This is work." Sam h1m-

nm : shit. I don t come e1 e . .

~:;~~~:~~~~~: ~[~;~ ~:7:.:';,;~ ~~~:; ;~:~·~~e~oo~:'~::~,~~~:~ Whe n Sam It . lass town in the East ay. d es not

house in Pittsbu rg, a wo~ku~g-~age ended "bad ly," saying th at ~e oarried. occasion that his se_co.~1n ~~~'out. "She couldn't b el_ieve what ~ h: ~oes not blam e his wife fo r kJck1 g h 'ld n and two grandch1ldren : bu " "I '

- ld I " H e has four c 1 r e . --· e or death m the lam I )· f N01 cou · h r e 1s a mat n ag _ ult o n of them except whe n t ~ . second m arriage as a t es

see a y lains the de te riorauon of hi~ k" (This is no t unusual. The Sam exp h eavy dnn mg. .. ·n fam-

unemploym~t and su~~eq~~~~~t higher than the ~ation~l a\:~a;et~iya\ent divorce ra te ts around t ~ t a job and canno t quickly ftnd . -· q engines ilies where the father 1~S o~ fro m well-paid union work rcpau m g

I'') First Sam was la td of on e. -

HO :VIE L. ESS MEN RECYCLE T H E IR PAST S 83

fo r a utility company in 1985 . He had been working on the same vehicles fo r years, a nd knew them inside out. But engines changed , and he could no t get moti'"a ted to learn the new techn ology. "Hit me h ard, being on the scrap heap, I'll admit that. . .. You don 't much conside r about unemploym e nt, you know, till it happens to you. The n it's too la te to get your bearings." Electronic tinke ring with new m od els "controlled by a stupid piece of plas-tic" offended his deep love of "real" cars, to which he had dedicated bo th work and le isure hours since he was a teenager.

Sam found it very hard to deal with his declining position in the labor market. His last j ob was with a nonunion corporation specializing in brake repair, where he never ac tually got to work on cars, but instead had to fo l-low a mon o tonous and rigidly e nfo rced routine . Even though the pay was lower than ten years before , Sam sta rted spending half his incom e on cocaine. "My heart wasn 't with my j ob anymore, and the m anager was always pushing me. He gave us no respect ... . So I got to putting half my p aych eck up m y nose. o woman to check u p on m e." [Sam winks.] "I was generally

emoralized , you know. Everything had gon e to shit."

When ho meless recycle rs like Sam express disbelief a t their decreasing abil-ities to com mand eith er decent wages or respectful treatment in the years before they became hom eless, they are pointing to a phen om enon bigger than their own personal shifts in social location. Call it what you will-a "space of flows," d isorgan ized capitalism, the condition ofpostmoderni ty, o r la te capitalism 1:1-there are seve ral ways in which the Bay Area econo my of the nine ties manifests qualita tive breaks with the situ ation twe nty years ago.

On the national level, large-sca le, collective, wage-bargaining structures ha~appeared . Monopolies have broken out of state regulation almost entirely, and manufacturingjobs have either gone e lsewl1ere or been trans-formed into minimum-wage, temporary work-work designed for women, immigran ts, and young m en who do not have the m emories of better con-ditions that might make them mutinous.

California suffered the effects of this r estructuring later tha n the o lde,-manufactu ring regions of the United States. The state was insulated from the manufacturing collapse of the early 1g8os by its disproportionate sh are of defense contracts, its large share of compute r and bio-tech compa nies, and a real-estate fren zy finan ced by the Los Angeles-based junk-bo nd boom. 14

The early nine ties r evealed the inability of these industries to sustain gen-eral prosperity. Working-class Califo rnians suffered from a prolonged and severe recession, losing 1.5 mi ll ion jobs in 1ggo -g2, including a quarter of all manufacturing j obs. Construction , always the best be t fo r unskilled m ale labor, practically stopped-the rate of housing start~ in the early nine ties was the lowest since the Second World War.15 Sevet-al white recyclers have

8-t TERESA GOWAN

m entioned that journeyman work used to earn them twelve to fourteen dol-lars an h our. By 1994 it was down to six or seven. In the Bay Area the dis-junction between the decimation of hea,y-industry work and the booming computer indusuy added to the problems of blue collar workers by bring-ing in large numbers of younger people with high disposable incomes who are able to pay increasingly fantastic rents and house prices.

The unemploym e nt crisis for manual workers has contributed to the blossoming of the local informal economy. Unlicensed and tax-avoiding entrepreneurs and their employees flourish , working as und~r-the-table taxi drivers, carpenters, h ouse cleaners, hair dressers, recyclers, mechanics, dog walke rs, electricians,junk vendors, garment-makers, psychics, roofers, man-

ufacturers, nannies, and gardeners. Rather than providing competition for the more formal e nterprises,

much informal work actually interlocks with it, increasing the profits_!.O large companies. 16 ln the case of San Francisco recycling, the garbage giant Norcal dominates both the legal and the informal economies in trash. Norcal h olds the city contract for both garbage collection and curbside recy-cling. The company also owns the two largest recycling companies in the city, both of which buy the overwhe lming majority of their materials from the scavengers of the informal economy.

Sam and other ex-manual workers picking up bottles and cans on the streets o f San Francisco are participants in a great slide from secure wage labor in the formal economy to insecure "survival strategies" outside of any protective regulation. But the pros will not accept the idea th at recycling represents a reactive, hand-to-mout\1 existence, a desperate scrabbling at the bottom of the heap. Rather, they all appreciate and take pleasure in their work as a ch allenging, socially useful activity, which gives structure to their days. In Sam's case, recycl~~ vehicle for himjo bring his o ld mechanic persona aliveJgillrl• co~_P.ete1!,!;_.~ndustrious. But in order to convince himselfwith this act of will h e needs to continuously distance him-self from the apparition of the lazy scam artist.

Sam and most of the oth er white pros are quite explicit about diffe renti-ating themselves from Jess hard-worki ng homeless people. They often dis-cuss the hopeless dependence, laziness, and irredeemable "snakishness" of other poor men, me n who are not "worke rs" in their eyes. Some times they have good reasons for suspicion. Sniping across the timeworn frontier between the deserving and the undeserving poor, they effortlessly slip into a repertoire of contempt instilled in more prosperous former Jives.

Their contempt is racialized: poor African Americans are the most com-mon targets. H owever, most of the -white recyclers make a point of express-ing respect and collegiality toward the black recyclers, as long as they are fiercely gung-ho about their work. Derick, a thirty-something African American vete ran, credits Sam with getting him going as a successful rccy-

HOMELESS MDI RECYCLE T ' ' HEIR PASTS 8 -

cle~. ''Y~u wouldn't know it, but he 's ti ht ) losmg ll, but he persuaded m . g ,.·Sam. There was a time I was reall)' mone , [H ] e tecyc 111<T could mak ) · e ... ga,·e me a bunch of oodo ti s, e me som e dece nt

_Sam marches the streets to e gl p . 0 scape t 1e ghost fl . _eau_p_sr. the r pro recycler;~-;;-· - - - o . 1tmself as an undesening understandings ofthei . 11Jut e up more positive, even e~~nger I. . h r vigorous work ethic. D· ,. d , . < tea , Wit a much more counte rcultural h. I a\ I , another whne recycler h ow the moment-to-moment s /story t 1an Sam, talks passionately of of it all, keeps him human. ense o purpose, the rhythmic physical effort

I don 't know about other peo le but if , I'd lose hope for being able top I wasn table to recycle, I'd lose hope ' t' h 1 putone footinfro ftl · I 's a.c ~I enge. Takes determination. . ' nt o 1e other. A lot of times It s hke It accelerates )'Ou S d .. I m not domg so well, I push hardei· . . . . . orne ays 1 g r . . mean, I JUSt get on with my work f . et ~o eel hke the old Dave. . . I . , no uss,JUSt hke other guys. .

Whtle the physical work itself is usuall . pro recyclers can become a II . ' y solitary, the cultural work of the talk about their workJive• ;., .~~ . ecttfv~ project. Many of the men naturally . --~ ........... ....... nls o we " .al- l - -s~etal us~fulness of recy·clt.J1g . , . , espeu y when appealing to the 'J: k' VIS-a-VIS Other · a mg time out under the freewa on e d occupauons. of the homeless. cussed the superior morality of th y I. ay, ~nthony, Bill, and Javie r elis-e recyc mg hfe:

Anthony: We'l·ejust trying to be dece dealel-, because I do happen to h nt, you know. I mean I could be a drug ave a connect' [L we want to choose the other road not - . ' IOn . aughter.] But recycJe,-s something. Just cleaning up the l~e· hpbt eylm onto people's kids Ol" stealing o; 1g or10od.

]avil'r: But people disses us anyway. o res ect ~ ' Bill: ot evervone d . p . ou re a bum, you' re scum.

b ' tsses us. OK, those ig --ut at least we know and peo I . I not ant mothcr-fuckers don 't see it

o t I ' p e wiL 1 eyes know h ' ' u lere , the recyclers. The best w . ow we re doing a good job I"Ough. Well , most of us anyway. e can seemg as things are t11is fucking

Anthony- Exceptj · . . , avler. [He shoves Javier affectionately.] Bdl: You tore inLO t11ose ba l'k . . d I gs I e a pack of co t own I 1e profession. . . . yo es, man. Definitely letting

J avier: 1 e\'er kne I [G

w was a professional Well 1 d eneral amusement.] · w 1a claya know. I finally made it!

SE RGEA TT TO SCAVE . GER: CLARE CE

As he tells tt, Clarence was a mama' b . a tract ho~~ in South Central Los~ ~j" Ratsed "strict" i.n a Baptist family in most ofhJs free time playing sports ; ~s, he was rarely m trouble and spent

. ut e was not altogether a happy child.

86 T ERESA GOWAt':

His fear of his father, a m an who combined substantial drinking with h ellfire sermonizing and righteous whippings, led him to escape th e neighborhood as soon as he could. LeaY1ng his family for good, he j oined the army right out of high sch ool and did pretty well. o t seeing himself as the mach o type, he gravitated towa rd "wheelin' and dealin"' from his post as a supplies cle rk. ln his eigh t years sta tioned in Germany he built up se\'eral links to the local underground economy. ''1 be nt the rules some, but didn't do n o harm-everyone does it," he says. This made him plenty of friends, both on base and off. Clarence really liked Gennany and misses his German friends intensely. From where he is now, his years in Germany appear bo th impossibly far and close to his heart. The details o f his life over there, his daily routines, the n am es of acquaintances, of local bars, sh ops, and parks, all are extraordi-narily fresh in his mind. Like m any African Am ericans, h e experienced living in western Europe as a release from the type of racism he had grown up with in Los Angeles. "You never know what 's your good time till it's all over. T hat was my good time, I guess." He some times d ream s of getting together the air-fare, but he knows it would be real diffe re n t without the army.

Clarence is n ow 4 2 and a h om eless recycler. He was discharged from the Presidio army base in the la te eighties, after failing a second random drug test. In shock, he unsuccessfully floundered for subsistence an d hou sing. All he knew was the army and its ways a nd m eans, and he h ad long lost touch with his fa mily. H e considered u-yin g to find his mother. Maybe his fa the r was dead , o r pe rhaps they h ad se parated. In the end, Claren ce was so ash amed of his cocaine habit he could not face his mother anyhow. "I mean , I was the good son, you know, n o t the crackhead . Funny thing is, 1 still am , after all ." lot knowing other poor p eople, it took him six mo nths to find the soup kitch ens and to get on Ge neral Assistance. During this time h e Jived only a few minutes \Valk from his former base, camping on Baker beach and eating out of garbage cans. "1 was too depressed to get my shit together, too ashamed to ask fo r help. But one good thing, I got clean of cocaine, seeing as 1 had no cash . Didn't last though . .. . Drugs m ess you up, but o nce you 'r e

down , it's all you've got." Most o f the day Claren ce push es two large carts aro und the city, follow-

ing a recycling routine th at he calls his "patrol." Several restauran ts save him b ottles and b oxes. Apart from the obviou s be nefits of stabilizing income , su ch connections a re importan t p oints of pride, ways to convince himself and othe rs that people wh o are n o t h om eless rely on h.i_s services and trust him to keep to a routine. His manner is polite but preoccupie , a\~

'-_A. - "'-"""' , --....--..., -casn~ye contac . He often h as a puzzled, distracted look, as if be canno t

rem embe r where he put somethin g. Claren ce has m ad e quite a success out of recycling, winning the respect

of bo th suppliers and peers for the size and quality of his loads. He consid-ers his work socially useful and insists th at o thers realize this:

HO:v! ELESS :-.1 EN RECYC LE THE IR PASTS 87

The company, 1'\orcal, doesn't mind us tal kin ' . mission to pick up their reC\·clit Th ,' . ~ to the publtc and asking per-' lg. C) I t: WOI ktng to\ , ·d · consciousness. 1 believe tl'e)' 1 k 'a

1 an ennronmental • vatu to ma ·e sure th 1

place. V\'e' re sorting it out so it d . b k d e t~as 1 goes to the righ t . oesn t rca own an [ . k ' ] . contammous toxic waste in the soil. . . . ma e potsoned

To put Clare nce's interpre tation i extre mely antagonistic rela tio 1sh· n lcoii1text, many oth er recyclers haYe 1 1ps wtt 1 t 1e same comp . h

are som etimes physically viole nt to ho me! any, w ose work.ers to pe rsuade the Immigra tion and Nat e_ss/ec~'clers. Ot.1e m anager tned an o ther of th - y, • . lll a tzauon Se rnce to prosecute with some N:r~~~:~~t C~arencek~tmself has achieved a cordial rela tionship

. < · • e\ en wor mg fo r th em as a -· d occasiOns Few "street" h 1 secunty gu ar on a few . om e ess people can m·tke th I e nough for wage labo r but Cl . < em se ves acceptable • , atence m anages to k h. f. rally clean and well laundered I eep Jmsel supe rnatu-, even t 1ough h e sleeps · th out on the bare sidewalk ever ' . I f th . m e sam e clothes ) mg 1t o e year.

Clare nce h as a similar approach to his rei· . . . bureaucracy. Welfare offici I f auonshtp wtth the welfare . · a s o te n act as though cr t I JObs, but no legitimate Jives outsid tl . l . ten s n o t on y have no for the m to treat such third clas· e. t .1etr c a tmant status. It is therefore easy - s CJ tzens as though they h h . ter to do than wait in lin e £ l ave no t m g be t-. o r seven 10urs o r spend ks \1 . n ght fo rms fo r entitlem ent t . . . wee · co ecung the o mamtam the tr bare s b · women on GA are pubr 1 ·I u stste nce. Men and the ir depende nt status ~~ ~:a~~~:r~f su·e~t-sweeping duties, which display common role o f resen g . . pub he. Yet gstre nce re jects the more ~ul t:a~e~et~n sti&!!!-~~:~e~~~t, thinkin g of himself more as dutJ-

Umque ly am ong the pros Cl d . _--~._..~-.;;;.;.;.;.;;:;~..:::;~~~~~a~re:;,:n~ce~~e~c;illlaJ~ h ·~earn~ngs to the city:

You know, with General Assistance we' re allo in our receipts once a month I' h. wed to make money, and we mail · m on t ts program now \~ d . h sweep the streets and we can do recv . . . c on t ave to we' re allowed

1 ·k . . ' chng. Actually, we sttll go to workfare but

0 wot part-l!lne. We're allow d , . bucks-well even more act . 11 E . e to eatn up to four hund t-cd · ua Y· veq one hundred d 11· -mmus twentv dollars frotll 0

. G 1 A . 0

at s ""e earn we arc 1

lll cnera sststance b • · zone for, well, eighty bucks. · · · · ut we re 111 the plus

I m entioned to ano ther rec 'cler W· l s:nt in his recycling receipts t~ GA. :et~:~tat at lea~'t o~e.recycler 1 kt~ew tlous " h e said "that' . . amazed . That s no t consoen-

' ' SJUSt m sane." V\1alter thinks h · · · sue any legitima te rela tionshi with the t at . .!!.•~omtless to pur-

l'iO'f"fi-eated l·J.ke otl . . p Ci ty, g iven th at homeless people are 1er Ci tizens "WI k.d

Clarence ~11 no t participare in hi . 1Y J . ~ou~sel~" was his take . But has to. One afternoon De rick was sc~wn ~~·ar.gmal~za~on any more than he office. Clarence said "OK . b mp ammg o hts treaunen t in the GA

• ' may e. But you can 't · · d respectful and tha t's what . . , D _. give .a ttttu e, brothe r. Act you get. en ck shook his head , incredulous.

88 TERESA GOWAN

. · ause fo r thought, )" Afte t· his characten suc p "Respect! Righ t! You crazy man . Clarence answered , "Not really. o t yet.

f ll of homeless veterans. . . . 1 The streets a re u . . . Clare nce's sto t-y ts no t unusu~ . . f the postwar years, the mthtary pt_o-As ilie biggest public works pt ~gt am o d women, with j ob secunty

. b c . 0 ·kmg-class men an L . "dec\ millions ofJ O s 101 w 1 Af · n American and a uno VI • 1 ns For many n ca · . a nd decent be nefi ts fo t \ e te ra . . "ddle-class Am erica. But warfat e

l d ddoormto mt . d h me n, it opened a muc ~-nee eh _ h-t ch highly mecha nized affatr, an _t ~ is being transformed m to_ a ~g eraciually sh ed , re moving the m?st t ell-mass-employment model '.s ?emg ~ion for the young me n of low-m come able employm ent and trammg op

communities. . . . the rest of tl1e American economy toward The changes mtrror the shtft m . b I' alysts on the one hand d f ll patd sym o JC an a dua e a no my com~ose ~ ~ve -. rvice and assembly_ worke rs on the an mass o low-pat~ ~nd ms~cut~sea~led technicians land well-paid and sta-o ther A core of e li te miiJtat-y office I" . d n e n and women clean floors

· h "l ·1r ons of en tste ' k ble employment, w ~ e. mt I . e level Basic military pay is $ tgg per wee and stand guard at mmtmum-wag . 1 "Article 15" punish ments

. ders frequent y use .. before taxes, and unit comman c. • "tt1fractions. One in iliree recrUits lei ' . ' pay 10r mmor · 1-

to furthe r dock ilie so Jet.s . . he r fi rst term of e nlistmen t. ' . drops out before comple tmg ~~~ OI . • . b tantial area of deindustriahza-

. f the milttarv IS a su s . h d The resu·u ctunng o ' C ld War mihtarv as use · es th e post- o ' tion. Like the Fortune 500 com~an-~c;le redundancies. Started by the avy d testing to pu~h ~hr!2UJQ1 ~~~ ~testing spread to other

---~eolcompulsory ran 0 " B I the m 9 ' a neavy tegi h ·u of"surprise and de terrence. ) ·1· unde r t e t1 e ·11 I d · g branch es of the mt na ry, 1 . . g to have reduced t ega Ill

. I p t on was c atmm I d" e nd of the eigh ttes t l e en ag d l"ke him dishonorab y ts-th . ds leaving Clarence a n many t use by two- tr '

chargec\. '8 .

. . es as an unskilled for ty-someiliing :Un can Making the best ofhts bleak chanc h ·tel usuall)l acting as tf sleep-

b - e face to t e wot ' · American , Clarence turns a ' av d f' . hundred po unds of bottles ts d h "ng aroun o u1 · 1 ing on the sidewalk an p~s I f . l tha t o the rs will see htm as t l e

J·ust fine wiili him. He tn es to have att 1 u· n es h e gives signs of what . h is Yet some J upright, harcl-workmg l_nan e ." d Once I asked him why he slept out might lie unde rneath thts upbeat faca e. tl e r than finding a hiding place

b ·c1 garment factO!)' ra 1 " h , 0 o n the sidewalk est e a . I 'd , h e answered . T ere s n

"I ' got nothmg to 1t e, . "B like most of the oth ers. ve I on him I asked htm, ut d keep some cas 1 ' 1-f need." As Clarence ten s to h "'" H hook his head and paused . c d D ur cas - e s Co uldn 't you getjumpe or yo . . ' t be givin ' them a reason , any . h " "Look you can d screwed up his eyes, stg mg. . . ' ickl l vVhat he meant, I later un cr-

reason." He changed th e subJeCt q~ I \ h er "decent" fo lk, le t alone the d

'"as that he d idn ' t want to gne o stoo , ·•

HO.\IE LESS ~1EN RECYCLE T H EIR PASTS 89

police, any reason to classif)' him as a furtive criminal. He is no smalltime dealer with a stash of rocks, no petty thi ef concealing his spoils, only a n hon-est worker of the unde nvorld, with nothing to hide bu t his pain.

Clare nce is no t the deluded fool that Walte r thinks he is. He knows that his status as a homeless black crack-user is the arch etyp e of th e violent crim-inal in mainstream popular culture. His response to this dilemma is to cre-ate a transparent, strenuo usly legitimate life, which leaves no room for

_ s1!§.g!_cion ,__. ~

In his struggle for respectabili ty Cla rence does his best to have the same kinds of rela tionships with his supplie rs, wi th the church, even with gov-ernment that he would choose to have if he were not h o me less. This is an incredibly diffic ul t task. For example, Clarence tried at one point to j oin a church congregation, attending serv ices for seve1-a1 weeks running. This a ttempt to j oin a community of ho used people on equal terms went into a spin whe n t1vo companio ns from the street insisted on j o ining him. Th ey sle pt through most of the service, the n ran off with the collection mo ney. "Tha t was just so depressing," he said. "I knew th ey were up to some thing, b ut I couldn 't be sure, you kn ow.':_ Not only does Cla rence act as if he is no t

_j!!Homatically stigmatized as a hom eless man , but he also giv(',.S his compan-~the..same ben efit of the doubt he requests fo r himself. In his own woi·ds,

"Yo u know, whe n you lose trust that 's it. You 're gone." Clarence's a ttempts to be "normal" mark his refusal to pa rticipate in the

stigmatizing process by prete nding he does no t see it. Tt-ying hard no t to "def:Oilllt" on his "schedule," he converts what most people consider a highly informal hand-to-mou th subsistence p rac tice in to a legal, transpare nt rou-tine. Fro~ infom1alizjng the milita1-y, he has moved to formalizing the infor-!!Jal economy.

Clare nce's proj ect of transparency and connection is quite d ifferent from Sam's compulsion to throw himself passionately into his physical la bor. Withou t reducing eith er man to racial stereotypes, it seems clear iliat for

..... qa,~:ence-dignity ~ n ot to bs_~cbieved by back-breaking labor, "slavin~ Such donkey work is all-too-connected with the legacy of slavery to be a source of self-es teem. J ames, a no ther African American pro, is equally dis-paraging of "pure" labo'~ comme nting: "My old man slaved himself to an early death laying tarmac. He wan ted some thing better fo r me." Most of the African American recyclers underplay the physical effo rt involved, alth ough many of them work very hard ind eed. For them, ilie pure effort and bodily strength th ey put into recycling is no t the primat-y hon or in ilie work, no t ilie part that th ey say makes them feel more hum an. They are more con-cerned to see th emselves as skilled and kno~ledgeable, able to make and maintain relationships with 'tlleir supplierf'"Sam'":"i n~tlikirlg antith esis, draws on ilie long time n o tion oftlle white Republican worker, for whom vigorous, taciturn work habits fo rm the corne1·stone of individual freedom and oppor-

--------------------~F~---------------------92 TERESA GOWAN

. . otTense several years before. Now he was the law be ing a drunk-dn~lng I . t Once inside he suffe red the . f T ' lea,1 n g them c esutu e . ' . ripped from his ami ), . first-time prisoners. He did not . huini' II'atio n and despair common to pamc, ' knmv how to fight: ,

I · , •orld there s a . f lk a nd then , well , I le musiC ' , . See, 1 grew up wnh women o d 't -ant to know the shil I went thm ugh m bunch of me llow dudes. · · ·You on " f . 1 got myself thm ugh by

1 1 1 n 't the worst o tl. · · · there. Losing my t~et 1, l w wash TV ... . Sta •ing out of certa in people's ~,·ay, reading and watchmg too muc ' I ~ tha t 's a full-time occupation. u-ying not to rattle this or that psychos c lam , <

bl k While the mili-'f - a working-class ac man. It is easy to be a felon I you aie ' I -col- unskilled working-class

k · le as mass emp oye1 1' tary has cut bac on Its ro . . d t ' has taken up many of them. In

I · ' ng pnson In us I) . men and women , t 1e nsi . I -· I d ince Jg8o while nauonally . h b - fpnsoners 1as t11p e s ' . Califorma t e num et 0 . . h _locked up or under supen'l-f th bl ck populauo n was eit ei .,

7·9 percent o e a ' th 1 ~ ercent of the white population.-~ . sion by Iggo, comp~red WI ·/ ~. 1 of the military, the vast expansiOn of

Taken together with the downsiZJI g d f I Cold War is emblematic of . . d . ce the en o L 1e the incarcerauo~ 111 ust~ ~.~~~ of Am erican governme nt. The gradual era-certain changes 111 the pnonues f te m of penal colonies has T , . d growth 0 a mass sys sion of the mass mi Ita!J an k' I . black Inen African Americans . · ' fi t for wor mg-c ass · been particularly sigm can . d . th lower ranks of the armed . - · tely represente m e . have been dispropOI uona d I . , a t the same tim e been dispro-. h s d World War, an la\ e forces smce t e econ . . . . h . 'I 'IaJl economy. T hey now . d . d u· ahzauon m l e CIVI ' . portionately hn by em us I . . victed of crack cocaine deahng, account tor over go percent of pns~nei s c~7ar e American cities.22 and the majority of homeless m.en m m~s . < g re the e ngine of the in car-

. d t ·afficking COn\IJCUOnS a Drug possesswn an 1 th Af-· n Americans doing time , 86 to I 99 I e lJCa ceration boom. In the years I ~ . d b 465 5 percent.23 This law

· t , pnsons 111crease Y . · fo r drug offenses m sta e d . . tl black and Latino crack h· · on the pre omman Y e nforcement emp asis d l t Until Ig82 he roin was the . 1 · 1' -ecent eve opmen · cocaine trade ts a re attve ) I A (DEA) and local police . . f D - Enforcement gency . .

pnmary target o Jug . h mass consumption o£ powdei . · · A- nd that t1me l e . 1 anudrug acuvny. 1 ou . . th 'ddle and upper-tmdd e d nanly among e mi

cocaine mushroom: , pru these secto rs was quite hierarchica!, and classes. The economic structure of I . f . k cocaine taking off m the . bl Tl popu an ty o cr<tc , therefore relauvely sta e. le f th dJ·ug trade Anyone with cook-. . . "0 d " the structure o e · . . mtd-eighues, atte ne . d ld convert powder cocame mto ing equipment and bakm?. powTel r cou ·ng turf-wars became more and

. . h peuuon 1e e nsut . rocks and JOlll t e com . · 1. 1. on this new more hon zon-. .fy. · easm g po ICe ocus ' more viole nt, jUStl mg mer k . d has consolidated the crack-1 t as the crac · tJ a e ' tal industry.-~~ seems t 1a d I' d The decline may, however, be too late related homtcide rate has ec me .

HOMELESS ;vrEN RECYC LE THEIR PASTS 93

to change public opinion. Media pe rceptions of the problem were manip-ulated by the Reagan administration and the DEA, until most journalists, and therefore most Amel-icans, accepted as common sense the idea that street crack dealers were the primary agen ts of the d ecline of the quality of life in the inner cities.2·1

Desmond 's experience would suggest a more complex relationship be tween devastated inne r city neighborhoods and the crack trade. For him dealing was a last resort rather than a longtime project. H e says tha t he cer-tainly had no ambition to rise in the business, only hoping to find some thing e lse and get out. That is why he was halfheartedly working a street corner a t the age of forty. "It 's ironical how, well, I wasn 't really suited to dealing. Not a t all. For a start, I'm too softhearted. Some poor fiend come beg me for credit I found it hard to resist. Especially women. I' m a family man. "

T he mandatory sentencing required by the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act slammed down on Desmond and his companions in the vast pool of"clock-e rs" (street dealers), most ofth em African American and La tino me n . Drug arrests and convictions soared . Squeezed into dealing for subsistence by tight labor markets, long-te rm poverty, racial segregation, and incremental welfare destruction, thousands of nonviolent poor men and women were pulled into the j aws of the expanding penal-industrial complex.

When she realized how long Desmond 's sentence was, Shirley took th e girls back to Trinidad, promising to come back when he was released. According to Desmond, his wife's mother, an evangelical Christian, was horrified by his offense, and put pressure on Shirley to divorce him during his fourth year in prison. H e has never seen any of them since. On release, Desmond was paroled to San Francisco, where h e hoped to make a fresh stan in a place whe re no one knew him as a d eale r. H e did not contact his sister, hoping to surprise her with good news later on . "Donna was good to Shirley, but shamed of my fooling. I never could get her to visi t m e in the joint," h e said.

Good news never reached Donna. Desmond's spiri ts were n o t high leav-ing prison , and he easily sank in the Te nderloin distri ct's sea of indigent ex-cons. Work seemed harder than ever to find, as he had no frie nds among the working population. It was a t this point, staying in a we lfare ho tel with a prison acquaintance, that Desmond developed a crack habit for the first time. "I knew what I was getting into. r was thinking, OK, things can ' t get any worse. May as well get high before I die." With no one to turn to, crack quickly exha usted his minimal income and he could no longer afford his share of the room.

Recycling, he says, is the best street life offers. "Less of the bullshit, maybe a fraction more of the respect." Keeping his cart in the mouth of one of three alleyways, Desmond can sit out on one of th e main drags, retrieving containers as soon as people discard the m. Every fifteen minutes or so, he

9 -1 TERESA GO WAN

makes a sma ll collectio n with a plastic bucke t from the nearby public trash-cans and sorts it into his cart. The rest of the time he sits o n doorsteps, read-ing the paper o r talking. A few wo rkers fro m the Ita lian restauran ts will bring him bottles, a ll stopping to discuss the weather o r the news. H e has great "people skills ," a low-key charm and an ability to connect with a great vad e!:)' of people . "Yeah, I've always been sociable," h e explained. ''1 used to wo rk the audience real good . It was a pity I wasn ' t a great singer." Most days Desmond sets offwi.th his heavy load in the early evening, toward a recycling company three miles across town. This is one o f the few places wh ere he can sell his wine bo ttles. vVith the mo n ey he can usually affo rd two h amburgers, a five dollar hit of crack, and some b ourbo n to get him thro ugh the night. Compared to m any homeless men , Desm ond's crack h abit is quite well con-tro lled. H e gets the crack and bourbo n in the Te nderloin o n his way back

to North Beach . Desm ond's fri end Julio, a Salvado ra n bus boy a t o ne of the upscale

Italian restaurants , arrives every couple of days with a load of empty wine bo ttles and a spliff of marijuana to share in the alley. Sometimes he brings leftovers. When they first becam e fri ends, Julio was convinced h e could eventually get Desmond a j o b as a dishwash er. "Have to keep trying, amigo. You' ll do good, 1 know." Desmond wo uld play along, "Maybe, we' ll see," but told m e privately that Julio \vas a great guy but he did not understand

Am erica ye t. Not black America anyway. I'm not saying it's im.possible for blacks to get ahead , because l sec plenty of them every day up here. £ \·en those traveling college kids \\~ th the sucker bags [back packs], some of those arc black kids now.~t for us it's always been one strike you're o ut. Me, I' m out, literally. [Desmond laughs.]

A couple of months afte r this conversatio n , julio got Desmond an inte r-view with his manager. Desmo nd was ambivalent about going, but eventually came to my place to spruce up, saying he did n o t want to hurt .Julio 's feel-ings. By th e time h e had to leave, he seemed o ptimistic, cracking j o kes about those free meals he would serve us whe n he was pro mo ted to waiter.

Apparently the m an ager spe nt only about one minute talking to Desmond and said he thought h e already had someone for the j o b. Julio and Desmond came away with different sto ries . .Julio seem ed fr ustra ted that Desm ond acted too une nthusiastic, te lling him , "You got to look like you want tlwt j ob." Desmond was softly unyielding:

Look, hombre, 1 knew he wasn't interested . He took one look at my face and knew I was on hard times. 1 doubt they ever hire blacks in those j oints any more, even if I wasn't a bum and a felon .... But my mouth doesn't help. 1f I was really serious about employment, I need to get me Medicaid and see about some dentures.

HO~IELESS MEJ\i RECYCLE TH E IR PAST S 95

Like a ll the , 1 I reC)c ers, Desm ond feels that the . c 1anged , no t just his own circumstances: nature of "socie ty" h as

I'm sm-e of it p 1 • , cope m general, across the b . ·d themsekes. Proud to be selfi I y. h . oat , now they more out fr>r

d I s 1· ou ear tt all over rk "I' . .

an a I that bullshit 1' II 1. ' 1 e 111 gemng me mine" . · · · · m a or self-help vou k b unity, people. ' n ow, ut, hell, we need some

Ano ther ex-con ·e 1 . . I eye er, a white man called George f, I h way. , ee s muc the sam e

I went to prison in 'S t Wh I . · en got out m ·ss I r. d changes in prison, but when }'Ott con , oun the change. othing 1 1e out you kno· · · a ways changing. Vll1en I came om If, d,. w, mto soo ety, things are who didn 't gi\'e a c tt-e ab h.' o un so many "snakish .. people people ' out no t mg. '

I asked Ceo ·f h rge I t c change was no t m o r h poorer people, unemployed or h o I . eAft a t now he was associa ting with

· · . me ess te r all h · positi on m those days a. d I. : , e was m a very diffe rent . ' s a e tverv dnvet· . h fnend. 1 wtt an apartment and a g irl

It's true, no o ne gives a homeless u ' the b . you wouldn 't let a guy go ho I g } enefit of the doubt. But back then

d) I . , me ess. ot unless he wa . u· I f . d . age · t d tdn t seem so much of . . bl s u Y n e [drug dam-would n 't get stuck. . . . a pr o em. There was work, you know, so you

Desmond also complains o f the difficul . street, given the mutual fear and h T ty of creating communi!:)' on the talks of street life as a )'Oung ,ostt tty[ among too m any street people. H e

. . man s wo r d requi · h ent mvmcibility of brutal youth: , nng t e energy a nd appar-

Oh, 1 dunno. Sometimes I think I'm ·ust too and now, now I su '"can 't de I . I .hJ . old now. I never was real hard I

a Wlt 1 t e kmd of bt II I . t . , mean, 1 sound like an old time " h ' • s 1t gomg down out here

I - r: l mgs ·tin 't ho tl ·

crest t 1e wave so I got sand . h ' w 1ey used to be." Can 't ' m l e mo uth. Shit

Later that night Desmond ran over a va .· . do successfully. "I don't ask f, • h . ' u ety of j o bs he thought he could h d . o t muc n ght now , h e .d I . . .

ea agam st an alley wall 'J . . ' sat , eanmg hts fore-. ust gtve m e a minim . appearance of basic respect and I'll b h . um-wage JOb and the e t at old-tuner."

INTO TH E D USTBI N OF HISTORY:>

Despite their differences Sam Cl· . . P

· . • , a te nce and De· d h ast m whtch they earned d , smon s are a common f

11 . ecent money and we r .. u y. As a mustcian Desmot d . e gen e t a lly treated respect-

S ' 1 was never m tl I'd fi . am and Clarence in the ir g d d 1e so I m anClal position o f never doubted th at a sol'd ~o b ays, but h e moved in similar circles and

' t JO would be his f o r the ask· D m g. esm ond

96 T ERESA GO WAN

remarked that ''In the o ld days, you know, it felt like some thing to be American , even for us" [black Americans] . "I used to know a couple of dudes from India . . . . We'd talk abo ut how you 'd never get that kind of exu·eme shit over he re. Not since slavery. But now . . . . " Desmond pointed to a wheelchair-bound h omeless man trying unsuccessfully to relieve himself discreetly. "Now we've got that."

Clarence , Sam , and Desm ond may not h ave considered themselves for-tunate at the time , but in re trospect their o ld days are bathed in a golde n glow. They exp erience the n ev,r o rder as a set of fo rces against them , which they canno t harness to their advantage . H owever, the reason the recyclers see deindustrializa.tion, military downsizing, and the War on Drugs as antag-

-oYfistic fo rces is no t becat~se they are inhe rently external, but becau~e these force~~ p art of a social o rder in which th ey h ave no part. Flexible nineties ~ a oes ~ ... haQl.(;S th~ioterests, Qr artic~ate th~ir e~

"-era of eyn esianism and the Pax Ame ricana was equally "big,"'l)u l"th ere they felt part o f the bign ess. Indeed, as soldiers, unionized worke rs, and consumers of goods subsidized by American m arket control, they were part of it. Even Desm ond m ade his living cate1ing to a prosperous black working-classallih ence, now either scattere d outside the historical black communi-____._ .. __. - . ties or suffering in their decay. The swinging club strips fed by the postwar black prosperity have diminished o r disappeared .

This new order int roduced by the Reagan administration , like its Keynesian predecessor, is no t only global but profo undly local. It presents itself to individuals in the form of both oven ¥helming constraints and novel opportunities. H e re in San Francisco the winners and losers are painfully thrust together. The disproportion ately black and Latino working class, the e lderly, and the poor of the city a re progressively displaced into Oakland and smaller de pressed suburbs by all the young people from suburban backgrounds pouring in to take ad vantage of the flexibility, good pay, in te r-esting work, and pseudo-Bohemia n lifestyles offered by the computer indus-try in th e Silicon Valley a nd San Fra ncisco's Mul timedia Gulch. San Fran-cisco h as lost over half of its African Am erican population since 1970. As for the hom eless, the software takeoff has nothing to offer them beyond a glut of mine ral-water empties. Emaciated panha ndle rs with hunted eyes creep into the less well lit restauran ts and bars, trying to hustle a buck befo re expulsio n.

The pros feel left behind-Sam explicitly calls himself a "relic." But in their h omeless state, the pros are in the ir own way integral manifes ta tions of resurgent conservatism in the United States. Mass homelessness is the m ost visible and, to many, th e m ost disturbing result of the end of the Keynesia n tax-and-spend model. Th e recyclers are th erefore no t exactly typical but are emblematic in their fa ll from working-class respectability into indigen t marginality.

HO MELESS MEN R ECYCLE T H EIR PAST S 97

"!'l:~cyclers are a lso emblem a tic in tha . "welfare mOiFie · ".gh etto ch ell . 1 1

t the poor- m ost specifically I --- - - v ers, t 1e 10m eless o r d . d .

t 1e most common targets of th . ' estttute a diets- are the las t fiftee~'ears. e compulsion t~ adapt that is the Zeitgeist of

Ne~l't Gingrich, coordinator of the Re bl' . " Amenca," said that "we siinpl)' b pu Jean 1 996. Contrac t with must a andon the If: . an opportuni ty socie ty "25 M D we a1 estate and move to · ost em ocra ts co1 · · · gm·ernment support from th d ' d 1C.Lll , mto nmg tha t rem oving I

. e 1sa van taged 1s the t . 1 . c 10 ice, the only wa)' to save thein f' . l . I u y compassiOnate rom ISO auon and de d · ond presidential debate of th e I 6 . gra auon. In the sec-

99 campaign, Bill Clinton claimed: I stan ed working on welfare reform b . . trapped in a system that was inaeasin ~~~: he~.~ use ' ·was stck of seeing people their kids more vu lnerable to . ~ , p }stcally tsolaung them a nd ma king

gettmg 111 trouble. 2G

Both parties would have us believe that th . is good honest work }'e t the d ' . ~ solutwn to endemic p over ty ' con ltlons of av·· 1 bl · b c ers a re unlike ly to pull a pe I I aJ a e JO s w r unskilled work-

< rson, e t a o ne a fam·l f workers are not covei·ed b c d l l y, out o pover ty. Workfare y •e era wage legis! ti I d terms of the Pe rsonal Respo 'b ' l· A a on. n eed , under the . ns• t ny ct they d h· . thmg over their basic welfare be nefit I l Tl o n o t ave to be pmd any-

1 of woi·kfare workers and worker . e.ve. 1e entry of bo th high numbe rs wages considerabl)' in low-wage l sbpl :V1ouksly on welfa re is like ly to de press

I a OJ mar e ts whe · k 1 g e to pay for ho using medical t . ' I e wor e rs a ready strug-

p . ' < Ieatme nt,and childcare 27 .ro.tectmg the wages a nd workin conditi . . . . .

realistic app roach in a glo b- l' d gl I ~ns of Cltlzens IS no lo nger a a Ize wor c eXJJlam R b R . left secretary of labo r during c J· '' s o e n eich , the cente r-m to n s first term c ment should resign itself to the reali h . . . on temporary govern-set th e basic terms of the wo ·k . ty t at m uluna uonal corporations can

• environme nt Go trate on leading the populat· . .h . . vernment sho uld con cen-. Ion mto t e m ost favor· bl . h . nattonal economy. In thet·l. t . 1 A . a e m c es m the inter-

lll n, t 1e m en can bl' 1 ld o n skill acquisition so tha t a f I pu IC s 10u concentrate . s many o t1em as 'bl bohc an a lysts the only wot·k .. h possi e can become sym-, e1 s w o can expe t d conditions.~~ c ecent pay and working

Even before they became home less the r . . . aged, re la tively uned ucated men like rh . e was .IJttl~ chance of middle-g rowth. Too young for re tiremen t, too ol~j~~sr ~~vmg mto t~1 e aJ:eas of j ob of the recyclers have neither th d . a. •cal.ly new direcuons, m ost capacity for "em otion work" e e ~cauon for high tech j obs no r the . . necessary tOr most · · · b 29 lite histo ries tend to prodt h sei V1ce JO s. · These kinds of . tee men w o a re bo th f, . .

p en enced at using the ir " . l' " . uncom Ol table and m ex-pe isona tty fo r direct e . . even minimum-wage em p loye l' k l . . conomJc gam. Besides, . rs are I e y to dismiss such . b l' po tentially overly assertive and unlike! . JO app lcants as they might well be right. Afte r all l ~to _learn new work practices. And

- ' w 1at e I ecycle rs took fo r granted abo ut

1 oo TERESA COW At\

her position in society. If Clarence h ad h ad a close, loving family to re turn to , technical or educational qualifications, or even just friends with civilian employment know-h ow, it is unlike ly that his discharge from the military would have left him so fundamentally alone.

Drug and alcohol use and abuse, after all , are endemic to society, both in urban and rural areas. Yet most people with addictions continue to function in their work lives. Cocaine, in particular, is favored by workers in high-stress jobs-high-end restaurant workers and lawyers, as we ll as the overtime hounds of the working class. One of the other recyclers developed his habit while working as a h ouse painter. "Th e money was no good, so they paid us a bonus in cocaine. I'd never clone it before. It used to be expensive. But on that painting crew there was a fair amount of peer pressure. You know, if you 're not one of the boys, you won 't get called next time. Some j obs it's beer, some jobs it's coke, o r crack. You work better on coke, of course."

The connection among drug use, hare\ labor, and impoverished men goes way back. Like the Bolivian miners chewing their coca leaves, the tramps and h oboes who built America usee\ alcohol heavily to numb their regrets and and reward their back-breaking labor. els Anderson tells how the "hoboes" senrec\ an intermediate role in developing the West in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They arrived too late for the great land grabs, but served a vital "in-be tween" role as cheap, fl exible labor power for the extractive industries that fueled the American juggernaut. The hobo labor market centered on the railway hub of Chicago; half a mil-lion transients passed through that city every year. Too poor to marry, too proud to do se rvice jobs, the hard-drinking, rebellious hoboes became a class of their own, often ending up dependent on the urban missions when economic slumps, old age, or industrial injury cut them c\own.

35

It was not their hard drinking that destroyed the hobo class. Just as the steel mills, auto plants, and other h eavy industries of the postwar period closed their doors on the industrial worker of the 1970s and 8os, the indus-trial frontier gradually lost its use for the hobo. Mech anization, corporate consolidation, and family settlement of the West lowered the demand for large numbers of migrant workers to build railroads, work temporary min-ing camps, harvest ice, and move crops. In this late r phase, in the 1920s and 30s, the underemployed hobo became a burden on the cities, as more and more former transients turned into "h ome guards" -low-paid petty work-ers, panhandlers, and con artists.

Like the homeless in the t g8os, the "transients" of the 1920s became a much-discussed social problem. Charitable municipal communities were instituted, and the h obo became an early subject of the new discipline of psychopathology. Specialists generally presented the problem in individual terms. Even though it was the demand of the frontie r fo r a tough, Hexiblc, bachelor workforce that hac\ created skid row, its culture, and characteristic

H OMELESS ~!EN RECYCLE TH ETR PASTS I OI

institutions, the psychopathol . e2·oblem" pu,:eiY!n terms of th ogtsts and . social workers assessed the "hobo imma ture '·wanclerlust " " e pe~s~nalny defects of the homeless matl ht·s · , egocentnc ty '"' · ' a ll, his drinking. ' ' emouonal instability," a nd, aboYe

Anderson , who was a former h obo and th . . tended to a more hol istic analysis: e child of a transient worker,

All tl~e problems of the homeless man o back . condHtons of his wo1·k Th ·. 1 . g 111 one " ·ay or another to tl1e . · e ureguanrvof l ·- . Irregularity of allj) lnses of I . . ., l ts employmentts reflected in the

• < 11s cxtstence To d . 1 ,- h 1 . ual, soc tctY must deal a lso' "tl I . ea ''It ltm even as an ind ivid-. ' "' 1 t 1e economi ~ . bchai10r, with the seasonal a nd I" · I fl c ~rces which hare formed his

tha t the problem of the hom I eye tea_ uctuauons in industry. This means e ess man ts not local but natio naJ. 36

" For Anderson, the primary solution to th I decasua lization of labor" t b . e lobo problem would be the · ' o e achteved b · · · ~auonal ~n:ployment system with the "ob of y ms~Itutmg a we ll-funded oes, prm'ldmg public works co . . Jd regulatmg employment agen-1 · 1 ' I peno s of bts. c1 · atmg unemployment insurance . ' I •_m ess epresswn, and regu-

An d in deed th · · 1 111 'u n erable mdustriesY

. •s IS w la t came to be in th N . depressiOn pulled so many of the o ul . e _ew De~! era. First, the great tural inte rpretation of vagra P ~ at.Jon mto sk•d row that the struc-R

ncy gamed un · c1 oosevelt administration set up th \AT ks p pr ece en ted strength. The C .. 1. e ·vor rogres Ad . . . tVI •an ConserYation C k s mm•strat.Jon and the . orps wor progran d I enutlements rescued the elde I f k. l S, an t l e new Social Security

b . r Y rom s 1d row In th , . · oom, the skid rows of Am . I . e v.a• ume and postwar . enca s 1ranktoaf· · f. radtcal tramps of the IW"' d. 1

1 ac uon o the1r o ld glory the n 1ec out, and th · .· . '

class found the means c0 r . . e m~oll ty of the white working '' marnage and bT · commo nwealth. sta ' tty m the new tax-and-spend

Now the shape of the society has chan eel a . so very different from the I . g gam, and the Iggos are not

1 920S. t IS an age of 1 , d · are new fortunes to be made b h 1) pe an ghttel~ and there . h ' ut at t e same time I . e ts ave been displaced an I . . aige numbe rs of work-' c ate roammg th . c

the labor surplus is less about th I . . e country lOr work. This time, mechanization of farnling d e c osmg of the second frontier and the

f . ' an more about gl b r · o heavy mdustry and union I b As o . a •zauon and the collapse ascendancy and imprisonment r:te~r~re hithen, free-market. politics are in thousands of si ngle indigent ' d gh. And, once agam, hundreds of th . nen an women cro d h k"

e maJor cities, panhandling, workin b th w . t e s ·•d row areas of and operating various minor sea . ~h_Y . e day, sellmg papers, selling sex, of the m are black or brown-skinn~:·d ;~:Ime they ar~ younger, and more

Like Ande rson 's hoboes t d ' .h poorest of them are homeless. h c1 1 ' 0 ay s omeless me h ar -c rugging crew with d . . n are a ard-drink.ing . ' a •sproportwnat b . ' convicts, o rphans, and other misfits 3R Ifth' ehnum er of free-thinkers, ex-

. ey ave enough money they may

1 02 T£RESAG0\\'AN

stay in one of the fe\V remaining single-occupancy h otels. The cage h otels and flophouses that enabled their forerunners to sleep inside for a minimal fee h ave disappeared. ow they can either sleep in shelters similar to the old missions or lie outside in the stree ts or under bridges, in doorways, or over steam vents. Like the mission stiffs of the twenties, a disproportionate numbe r of the h omeless and near-homeless are sick or disabled. Around 30 percent are said to show signs of serious mental illness.

39 A significant mod-

e rn developmen t is that illness h as become much more lucrative than it was in the past. O\V, a crippling hit-and-run injury or the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness is surprisingly often assessed as "worth it" by a man exhausted from years on the street. Now h e will qualify for disability pay-ments and can fmally move inside, into his own place. Disability becomes a solution as well as a cause of homelessness for some individuals.

Today, however, the problem of homelessn ess is even more international than it was in the Great Depression. ln all th e richest countries of the world, large numbers of men of working age are sleeping rough. In J apan , [or example, homelessness h as become a major issue since the recent econ omic crisis. In urban underpasses armies of men sleep in cardboard boxes, their shoes neatly positioned beside them. France , Russia, Britain, ltaly-all the European countries have th eir own manifestations of th e problem.

Like the psych opathologists of the twenties, most policy experts on the subject of homelessness and indeed poverty in general , agree that the growth of h omelessness in the eighties and nineties has little to do with labor or housing markets but is generated by diseases of the mind, dysfun c-tional families, and demon drugs. Like the reformers of the past, some favor outreach and treatment, othe rs prohibition and imprisonment.

The radical h omelessness advocates see the homeless as canaries in the mine, the vulnerable or unlucky few wh o are the first to succumb to the dan-gerous gases around all of u s. And many poor and working-class people agree that they are ''on e paycheck away from h omelessness." Lillian Rubin says that "Nothing [better] exemplifies the change in the twenty years since I last studied working-class families than the fear of being "on the street."

40

Yet at tl1e same time, policy experts, politicians, and other opinion lead-ers continue to medicalize homelessness, telling us that the canaries are suf-fering from a specific disease of their own. All we can do is h elp the best of them back into the mine, wh ere work shall set them free. With such lordly discourses we render natural and inevitable the grand social upheavals of our times: the sweeping destruction of blue-collar living standards, th e mass

.._ incarceration of black men, and the wh olesale abandonment of the poor.

N OTES

In the academic field 1 received wonderful encouragement and guidance frotn Leslie Salzinger and Amy Schale t. Back home, my band-Andrew, j osh, Gina, and

HOMELESS \<lEN RECYCI E T H.EI ' · - R PASTS

James- and my chosen family- Tricia I o 3 to kee~ ~ll)' fee t on the ground and m : 11~~:1-~oy, Kev, and Mark-all did their best ~f my hfe. Yly biggest thank- •o u oes) t full of music dudng a difficult e riod t esearch, especially Sam, Cla t~nceg dt~ a ll the recyclers who helped me wi~h h. chapter to those who didn 't k ,_an e_smond, a ll fic titious names I ded · t ts ma e It. Rest 111 peace b . h · Icate the , JOt e rs

t. Delails, Janmul ' 1997, p. 53_ · . 2. Both Details' flexible man !me Yisio 1 D ·1 · and the street hustle r d 1 . . rear t' / s, elat s because such levels of disaffir . mo e are pnmarily mascu-