Slavery and anti-slavery: a history and analysis Slavery 200 years on.

History of Slavery in United States

-

Upload

radu-valcu -

Category

Documents

-

view

11 -

download

0

description

Transcript of History of Slavery in United States

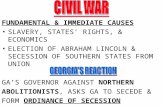

Slavery in the United Stateswas the legal institution ofchattel slaverythat existed in theUnited States of Americain the 18th and 19th centuries after it gained independence and before the end of theAmerican Civil War. Slavery had been practiced inBritish North Americafrom early colonial days, and was recognized in theThirteen Coloniesat the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776.Historically, the status of slave had become a caste associated with African descent, contributing to a system and legacy in which race played an influential role. At the time the United States Constitution was ratified, a relatively small number offree persons of colorwere among its voting citizens. After the Revolutionary War,abolitionistlaws and sentiment gradually spread in theNorthern states; in addition, as most of these states had a higher proportion of free labor, they abolished slavery by the end of the 18th century, some with gradual systems that did not free the last slave until the late 1820s. But the rapid expansion of the cotton industry from 1800 in the Deep South after invention of thecotton ginled to theSouthern statesto depend on slavery as integral to their economy. They attempted to extend it as an institution into the new Western territories. The United States was polarized over the issue of slavery, represented by theslave and free statesdivided by theMason-Dixon Line, which separated freePennsylvaniafrom slaveMaryland.Although the internationalslave tradewas prohibited from 1808, domestic slave trading continued at a rapid pace, driven by demand from the development of cotton cultivation in the Deep South. More than one million slaves were sold from the Upper South, which had a surplus of labor, and taken to the Deep South in a forced migration during the antebellum years, splitting up many families. New communities of African-American culture were developed in the Deep South; the total slave population in the South eventually reached 4 million before abolition.[1][2]As the West was developed for settlement, the Southern states believed they needed to keep a balance between the number of slave and free states, in order to maintain a political balance of power inCongress. The newterritoriesacquired fromBritain,France, andMexicowere the subject of major political compromises. By 1850, the newly rich cotton-growing South was threatening to secede from theUnion, and tensions continued to rise. With Southern church ministers having adapted to support of slavery, modified by Christian paternalism, the Baptist and Methodist churches split into regional organizations of the North and South. WhenAbraham Lincolnwon the1860 electionon a platform of no new slave states, the South finally broke away to form theConfederacy; the first six states to secede held the most number of slaves. This marked the start of the Civil War, which caused a huge disruption of the slave economy, with many slaves either escaping or being liberated by the Union armies. The war effectively ended slavery, even before theThirteenth Amendment(December 1865) formally outlawed the institution throughout the United States.