NTS Leaflet - From Prison to Prison, Occupation to Occupation

History of Human Occupation and Archaeology of Muriwai Regional Park

-

Upload

ninthshade -

Category

Documents

-

view

1.061 -

download

31

Transcript of History of Human Occupation and Archaeology of Muriwai Regional Park

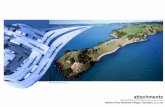

HISTORY OF HUMAN

OCCUPATION AND

ARCHAEOLOGY

AUCKLAND REGIONAL COUNCIL

MURIWAI REGIONAL PARK

MANAGEMENT PLAN

1994

Pages 55 - 80

(Please note that this plan has been superseded by the

Auckland Regional Parks Management Plan 2002)

55

Gigartina. Low sandstone reefs extend seawards for 20 - 50m and are coveredin clusters of the green-lipped mussel, Perna canaliculus.

Caves and guts.

Heavily shaded caves provide a unique habitat for marine organisms usuallyonly seen under water. Below a wide belt of barnacles including Epopellaplicata, Elminius modestus, Chamaesipho brunnea and Chamaesipho columnais a zone of the crumbling sponge Hymeniacison. Within very shady areas arethe golf ball sponge Tethya auranticum.

Within guts the bright red sea anemone Isactinia tenebrosa is common, alongwith the anemones Actinothoe alobocincta and Diadumene neozelanica.Ascidians or sea squirts Aplidium phortax and the soft coral known as deadman's fingers Alcyonium auranticum are also common. Tube wormsPomatoceros cariniferus, and Sabellaria kaiparaensis line the floor.

Subtidal Areas

The subtidal ecology of Muriwai has not been surveyed by the Regional ParksService! The most common fish caught off Fisherman's rock are kahawaiArripis trutta, kingfish Seriola grandis, red gurnard Chelidonichthys kumu,trevally Caranx georgianus, kelpfish Chironemus marmoratus and snapperChrysophrys auratus.

HISTORY OF HUMAN OCCUPATION

Muriwai Regional Park has a long and rich human history that extends back in time tothe earliest period of human settlement in the region. It is a history that ispredominantly concerned with the Maori occupation of the area, although it alsoinvolves European historical associations that go back to the early nineteenth century.The history of Muriwai Regional Park is reflected today in several ways. They include:archaeological sites, the modification of the natural resources of the area, and localplace names, both traditional and modern. These elements, in conjunction with bothoral and manuscript sources, provide the basis of this brief background human historyof the area. The history of Muriwai Regional Park and its environs reflects themigrations, conquests and occupations that have taken place in the district over manycenturies. Although the area has its own unique history, it is inextricably linked to thehuman history of the wider district. For this reason the human occupation of MuriwaiRegional Park must not be viewed in isolation, but rather in a wider geographical andhistorical context.

The study area is today referred to as 'Muriwai1, although this name did not come intocommon usage until the 1920's. 'Muriwai1, or literally the "backwater or lagoon1, was aname that was traditionally applied to the lower portion of the Muriwai Stream that islocated on the northern edge of the regional parkland. What is now Muriwai Beachwas traditionally known as Te One Rangatira' or The Chiefly Beach1. It extendedfrom Papakanui Spit at the entrance to the Kaipara Harbour to Tokaraerae1 (FlatRock) forty kilometres to the south. Many specific locality names were applied to

Inr

56

I j localities in and around the regional parkland, although the area was generally referredto as "Motutara1. This name, which literally means the 'island of the sea birds', wasapplied specifically to the rock stack standing ofFOtakamiro Point. This distinctivelandmark also lent its name to the land block at the southern end of the beach and tothe wider area.

At the time when European settlement began in the Muriwai Valley in the latenineteenth century the study area was occupied by two closely related tribal groups:firstly, Ngati Te Kahupara a subtribal group of both Ngati Whatua and Kaweraudescent; secondly, the people of Te Kawerau a Maki who also occupied the coastlineextending south to Whatipu. Small groups of Maori from outside of the region alsooccupied the Muriwai area at this time where they were engaged in gumdigging. Theyincluded Te Rarawa and Te Aupouri from the Far North, and Te Arawa from theRotorua area. Muriwai Regional Park and its environs, however, do have a humanhistory that pre dates all of these groups and extends back over eight centuries.

The first people to occupy the area were the Turehu' or literally those who 'arose fromthe earth'. These people, who were the first occupants of Te Ika Roa a Maui1 (theNorth Island), are seen by Tangata Whenua as their earliest ancestors in the district.The earliest known ancestor specifically associated with the Motutara area was arenowned rangatira or chieftain known as Takamiro. He, like his famouscontemporary Tiriwa, lived at a number of places between Motutara and Whatipu,although he generally occupied the headland which dominates Muriwai Regional Park.This landmark, and the pa which was constructed on it, are still referred to as 'O-Takamiro' or 'the dwelling place of Takamiro'. Both Tiriwa and Takamiro were leaderscredited in tradition with great spiritual power, and with the ability to modify thelandscape. During one gathering of Turehu tohunga, or spiritual leaders, Takamirocast off his maro (a short kilt-like garment) and threw it in the air. It flew southwardand landed at Whatipu where it was transformed into a rock known as "Miarotiri'l or'the maro that was thrown'.

According to local tradition the study area was subsequently settled by the Tini oMaruiwi' or the people of the Kahuitara canoe who had migrated north from theTaranaki coastline. Some of this iwi settled on the coastline between the Manukau andKaipara Harbours where they intermarried with the Turehu people. Over followingcenturies many other migrations were to influence the history of the study area. Thefamous Polynesian voyager Toi te huatahi left descendants in the district, as did manysubsequent ancestors associated with some of the well known ancestral voyagingcanoes that visited the region. According to the traditions of Te Kawerau a Maki therenowned ancestor and voyager Kupe visited the coastline between the Manukau andthe Kaipara. His visit is remembered in a number of place names on this coastline andin the traditional name for the seas that break relentlessly on Te One Rangatira(Muriwai Beach). They are sometimes referred to as "Nga Tai Tamatane' or 'Themanly seas', but more often as "Nga Tai Whakatu a Kupe', or 'the raised up seas ofKupe'. This name is said to have resulted from a karakia or ritual chant performed byKupe at Whakatu near Te Henga (BetheU's Beach) to upset the canoes of a group who

Today 'Marotiri1 is generally referred to ̂ y the) less inspirational name of"Cutter Rock".

57

were pursuing him from the Manukau area. Some say that it was Kupe who left theshellfish delicacy the toheroa, on the western coastline. In Ngati Whatua tradition theplacement of this taonga or treasure on Te One Rangatira1 is however credited toMareao one of the crew of the Takitimu canoe that visited the area over six centuriesago (Sheffield 1963: 24).

One of the earliest of the famed ancestral voyaging waka to visit the district wasMahuhu ki te rangi. "Entry was made by this vessel to the mouth of the KaiparaHarbour. Here Rongomai, the captain, Mawete, Po and others landed and settled withMaroto and his people who were the descendants of Toi living there at this time. TheMahuhu canoe left Kaipara and found haven in Doubtless Bay where the remainder ofthe crew formed the nucleus of the Ngatiwhatua tribe. Through intermarriages thepeople of the Mahuhu canoe were able to gain ascendancy over the residents they hadfound at Kaipara" (Sheffield 1963: 23). Another ancestral waka to influence theoccupation of the study area was the Moekakara. This canoe under the command ofTahuhunui landed at Te Wakatuwhenua near present day Leigh. Some of the crew ofthe Moekakara and their descendants migrated to the west and settled on the coastlinebetween Motutara and Whatipu. Here they become known as "Pu o Tahinga1 or 'thetribe of Tahinga'̂ . This name is still applied to a large land block lying to the south ofMotutara.

From these early iwi descended Oho mata kamokamo, who lived on the TamakiIsthmus. A number of his descendants migrated northward into the Kaipara districtwhere they settled. These people become known as "Nga oho mata kamokamo' orsimply as *Ngaoho'. They were also referred to as 'Ngaoho moko koha' on account oftheir distinctive method of tattooing. The Ngaoho iwi were to occupy the study areaand the wider surrounding district for several centuries and were to host othertravelling groups whose visits are well remembered in local tradition. In the mid-fourteenth century the famed ancestral canoe Tainui was portaged from the Waitematato the Manukau Harbour. After exploring the Manukau district, some of the crew setoff on a journey of exploration of the coastal area lying to the north. Led byRakataura, the senior tohunga of the Tainui canoe, this group explored the Waitakerecoastline upon which the name "Hikurangi1 was bestowed. Rakataura and his partyspent some time at the headland just south of the study area, which was namedTirikohua' to commemorate a place in Hawaiki or the Pacific homeland. They alsostayed at Maukatia (Maori Bay) and at Otakamiro, and then journeyed along Te OneRangatira to the entrance of the Kaipara Harbour. Here a 'tohu' or marker was placedat Oenuhu to commemorate the visit. The Tainui visitors were well received by theirNgaoho hosts with whom they established important genealogical links over thefollowing two centuries.

In the mid fourteenth century another important migration was to influence the studyarea. At this time what is now Muriwai Regional Park and its environs was visited by aNgati Awa group who were the descendants of both Toi te huatahi and the crew of theMataatua waka which had made its final resting place in Northland. Some of thesepeople, who had initially settled in the north, migrated southward and occupied the

I

This iwi should not be confused wih Ngati Tahinga1 who occupy the Te Akau areatoday.

if! ' - ~158

southern Kaipara area for a short time. They then continued further south and,, ,, ultimately made their homes in both the Bay of Plenty and Taranaki districts. One

! i party led by Titahi spent some tune in the Muriwai area where they are credited withthe construction of a number of pa. These included Te Korekore the impressivefortification that stands inland of the Muriwai Stream mouth. A traditional reference tothis states - "Titahi was an ancient chieftain of these parts. He was of Ngatiawa stockand was in his day overlord (ariki) of all of the district from Aotea (Shelly Beach) to

1 Manukau .... he lived at Te Korekore. He was the man who built the fortifications ofthat pa". (Rukuwai in Graham 1914:1) The occupation of the area by this famousrangatira is remembered in the traditional name of the long ridge that extends inland onthe northern side of the Muriwai Stream. It is Te Tuara o Titahi1 or 'the back of Titahi1

(Ibid).

In the mid 1600's another migration that was to have a significant impact on the studyarea took place. It was to be the origin of the tribal grouping that become known asTe Kawerau1, and in particular of the people known as Te Kawerau a Maki' whooccupied the Motutara area until the 1890's. The leader of these people was Maki whois an important ancestor, not only to Te Kawerau a Maki, but in fact to all of the NgatiWhatua sub tribal groups who still occupy the Kaipara district today. Maki was amember of the Ngati Awa iwi from northern Taranaki who had settled at Kawhia. Heand large group of followers migrated northward through the Waikato seeking a newhome. They initially settled near Waiuku then moved north to live near Rarotonga (MtSmart). Maki and his people subsequently conquered the Tamaki Isthmus and land asfar north as the Kaipara portage. Maki initially stayed at 'Maramatawhana', a Ngaohopa near Reweti, as a guest of the local rangatira Tukaiuru. He then constructed hisown pa Tinaki' just to the west.

Maki and his followers ultimately fought a series of battles in both the WaitakereRanges arid the southern Kaipara where they settled and intermarried with the Ngaohopeople. Maki lived at several places in the study area and his occupation iscommemorated in the traditional name for the hill country that extends southward fromthe southern edge of Muriwai Regional Park to the Waitakere Ranges proper. Thesehills are known collectively as "Nga rau pou a Maki', or The many posts of Maki'.From an incident involving Maki during his stay in the Muriwai area came the epithetand tribal name Te Kawe rau a Maki1, or 'the carrying strap of Maki'. Often shortenedto Te Kawerau' this name was adopted by many of the descendants of Maki and hispeople as their tribal name. In time, as further conquests and occupations took place inthe southern Kaipara district other tribal names emerged, in particular as the influenceof the Ngati Whatua iwi grew. In spite of this the descendants of Maid who occupiedthe Motutara-Whatipu area retained the tribal name of Te Kawerau a Maki'. Thisname not only originated from Maki, but also from a son who was born to Maki andhis wife Rotu at Mimihanui near Helensville This ancestor Te Kawerau a Maki, whowas also known as Tawhia, lived at a number of places in southern Kaipara including:Kaikai (Mt Rex), Ruarangihaerere (near Woodhill), and at Tinaki and Te Korekore Paboth of which overlook Muriwai Beach. His grandson Te Au o Te Whenua came tocontrol all of the land between the Muriwai Valley and the Manukau Harbour. It was

HI this Kawerau rangatira who was in occupation of Te Korekore arid Otakamiro Pa inji the mid 1700's.in

59

pi.'.

During this time several hapu or sub-tribal groups of the 'iwi1 known by the generalname of Ngati Whatua, migrated into the area surrounding the entrance of the KaiparaHarbour. Over the next two decades a great deal of intermarriage took place betweenthese people and Te Kawerau. However, fighting ultimately broke out between thetwo groups. The Kawerau people of south western Kaipara were gradually pushedsouthward and were subjected to a long period of domination, including a majorinvasion - Te Raupatu Tihore' or 'The conquest that laid bare1. During this period offighting the Kawerau pa of Te Korekore was attacked but not taken, although many ofthe smaller fortifications on the Waitakere coastline fell. This taua, or war party, was,however, not seeking territory and its members were in fact closely related to theirpeople who they were attacking. Rather they were seeking utu or revenge for severalkohuru or unacceptable killings.

The combined hapu of Ngati Whatua went on to take control of the Kaipara districtand to conquer the Tamaki Isthmus in the 1740's. However, because of peaceagreements and several important marriages concluded between the Te Taou3 hapu ofNgati Whatua and Te Kawerau a Maki, the latter group were left in occupation of thearea to the south of Motutara. Te Au o Te Whenua of Te Kawerau gifted taonga orprecious heirlooms to Ngati Whatua at Te Korekore and Kahukuri (near Waimauku)to conclude peace. His brother in law Rautawhiri also made peace with Ngati Whatuaat RangitopunH (Riverhead). Peace between the two groups was concluded by Te Auo Te Whenua of Te Kawerau and Poutapuaka of Ngati Whatua on the cliffs nearTirikohua Pa. This agreement and the place where it took place became known as TeTaupaki1, or 'the firmly bound peace'.

Subsequent to these agreements, peace was finally confirmed when, Te Waitaheke aleading rangatira of Te Taou married Te Kahupara of Te Kawerau. Their descendants,who were known by the sub-tribal name of Ngati Te Kahupara, became the dominantgroup in the study area in the century prior to European settlement'. Their settlementwas focused on the Muriwai Stream Valley, and in particular on Oneonenui the kainganear the Okiritoto Falls. A small kainga and fishing camp known as Tikiarere was alsomaintained on the northern side of the mouth of the Muriwai Stream. They lived inpeace with their relatives of Te Kawerau a Maki whose occupation of the Muriwaiarea was now no longer focused on Te Korekore, but rather on Motutara, Maukatia(Maori Bay), and the land running south to Te Henga. When John Foster establishedhis flaxmill in the Muriwai Valley in 1870, both tribal groups were still in occupation ofthe area as is revealed by the census data for the period. Ngati Te Kahupara andothers of Te Taou occupied Oneonenui and Motutara under the leadership of HoriWiniata, Paiura Patu, Te Kepa Matu and Tautari Ngawaka. Te Kawerau a Maki underthe leadership of Te Watarauihi Tawhia, Hoani Te Tuiau and Te Utika Te Aroha livedbeside them at both places. These two tribal groups continued to travel over theirancestral land undertaking the seasonal cycle of resource gathering that had beenpractised in the area for many centuries.

This name 'Te Tao-u' arose during the Ngati Whatua conquest of Kaipara. It isstill the sub-tribal name of the Ngati Whatua people of south western Kaiparaand Tamaki today.

The names 'Rangitopuni' and 'Kahukuri1 both commemorate the gift of dogskincloaks to conclude peace.

60

I

The natural resources that still attract people to Muriwai Regional Park today, madethe area an attractive place to occupy in the pre European era. It was also a place ofgreat strategic importance because of its geographic location. The study area waslocated at the southern end of Te One Rangatira (Muriwai Beach) which was animportant routeway until the mid nineteenth century. At Motutara routeways turnedinland to the Waitemata-Kaipara portage and also to the eastern foothills of theWaitakere Ranges where a pathway led to Waikumete (Little Muddy Creek) on thenorthern shores of the Manukau Harbour.

Although much of what is now the northern portion of the regional parkland consistedof the large expanse of sand dunes known as 'Oneonenui'^, the area offered a rich arrayof natural resources to its human occupants. The included the resources of both theland and the sea as is illustrated in the following whakatauki or proverbial saying.

"He wha tawhara ki uta, he kiko tamure ki tai1

The flowering bracts of the kiekie on the land, the flesh of the snapper in the sea1.

The archaeological site record shows that settlement in the pre European era wasconcentrated around Otakamiro Pa, and in particular in the Muriwai Stream Valley.Both of these places had relatively fertile and free draining soil, thus providing an idealenvironment for the cultivation of the kumara. Early survey plans of the surroundingarea indicate that much of the land adjoining the main settlements was 'fernland1

probably as a result of fire used in association with cultivation. The edible root of thearuhe or bracken fern would have been dug from the old cultivations and pounded toprovide an important staple food. While mere remnants of the original coastal forestare found within Muriwai Regional Park today, nearby areas such as Houghtoris Bush1

indicate what a rich resource the local forest would have once offered. The forest,which had been extensively modified after centuries of resource use, would haveprovided the local people with a wide variety of foods, medicines and buildingmaterials.

Karaka groves are associated with all of the main archaeological sites in the study area.Fruit from these was gathered in autumn, processed, and stored as a supplementarywinter food source. The berries of trees such as the puriri and taraire were alsogathered for food, as was the fruit of the kiekie vine. Other forest foods included: thefleshy stems of the nikau and the ti or cabbage tree which were harvested throughoutthe year. These latter plants were also used for thatching and as weaving material.Other plants found in the coastal forest of the Muriwai area had specialised uses. Forexample, the wood of the whau was used to make floats for fishing nets, the ngaio wasused as an insect repellent, and the kawakawa as an important rongoa or medicine.The berry producing trees such as the puriri and taraire, along with the floweringkowhai and pohutukawa, would have attracted other important sources of food. Theseincluded the kiore or Polynesian rat, and such birds as the tui, kaka and kereru or NZpigeon.

'Oneonenui' - literally the 'expansive sand dunes', is the traditional name forthe major settlement on the Muriwai Stream;and of the land block north of thestream.

61

Local traditional also records that the moa was caught in the area, although it hadbecome extremely rare by the end of the sixteenth century. A Kawerau waiata refersto the existence of TCuranui' or the moa in the district, and the traditions of this iwirecord that it was referred to locally as Te Manu Pouturu1, or 'the bird on stilts'. NgatiWhatua tradition records that moa were caught in some numbers in the southernKaipara until the middle of the seventeenth century (Sheffield 1963: 25). It is alsorecorded that as late as 1700 a moa was sighted in the sand dunes in what is nowMuriwai Regional Park and was pursued . A child was named Te Kura reia' or 'thestartled moa' as a result of this well remembered incident^ (Graham ms 120 m 59). Inrelation to the ancient birdlife of the area, it is of interest to note that a locality on thehigh country north of the Muriwai Stream was known as Te Hokioi1. This namecommemorates the existence of the extinct giant eagle or Hokioi in the area in thedistant past. The existence of the NZ Falcon is commemorated in the traditional namefor the ridge east of the Muriwai Golf Course which was known as 'Karearea':

The food resources that made Muriwai special, both in the distant and recent past,were those found on its coastline. From the rocky coast south of Tokaraerae (FlatRock) and the offshore reef known as Pekakuku', a wide variety of Kaimoana washarvested. These delicacies included: kutae (mussels), kina, paua, hopetea, pupu(catseye), kotore moana (sea anemones), koura (crayfish), and such seaweeds asrimurapa (kelp) and karengo. From the sandy coastline came the tuatua and theresource for which Te One Rangatira was justly renowned - the toheroa. Traditionrecords that the Kawerau rangatira Te Au o Te Whenua had toheroa dried at Muriwaiand presented as a gift to his relatives who occupied the Upper Waitemata Harbourarea. They in turn reciprocated with gifts of a special dried eel found in theParemoremo and Waikotukutuku (Whenuapai) areas. (Te Whirowhiro in Graham1914:4). A wide variety offish was available from the sea, with Te Tokaraerae (FlatRock) and Pekakuku Reef being favourite fishing spots over the centuries, as they.stillare today. *

From the sea coast of what is now Muriwai Regional Park came several other specialresources. They included the kekeno or seal which is now found in growing numberson Oaia? the rounded island standing one and a half kilometres offOtakamiro Point.They also included the Korora or penguin, and most importantly the tohora or whalewhich often stranded on the beach providing the local people with a major foodresource. Whale bone also provided a valued raw material that was used in themanufacture of weapons and many other taonga. A number of whales have strandedon Te One Rangatira over the years. The most spectacular strandings in the postEuropean era include: 36 whales in 1892, 16 whales in 1953, and 72 in 1975. It is ofmajor interest that many of these strandings have occurred in the vicinity of theMuriwai Stream mouth, and that the land block adjoining it to the south is known as"Paengatohora" or 'the stranding place of the whale'.

Graham also suggests that this woman, also known as "Kuraroa1, became the wifeof Tuperiri, the Te Taou ancestor who played a leading part in the conquest ofTamaki. It was his brother Te Waitaheke from whom Ngati Te Kahupara claimedtheir mana in the Motutara area.

Although this island has been referred to as 'Oaia' since European settlement,Kawerau oral tradition records that this name should be more correctly 'Motu-o-haea' or the 'island of the gleaming'. Those who know the stark whiteness ofthe bird guano on the island in summer will recognise the origin of this name.

62

Even the seemingly barren dune country provided some natural resources. Here weregathered birds eggs, puha or sow thistle, pingao a valued weaving material, and toetoewhich was used in house construction. Behind the dune country lay the large swampylagoon known as Te Muriwai1, and the dune impounded lakes located inland of thenorth eastern edge of the regional park. They include: Paekawau, Okaihau, and thelittle lake known as Waitewhau. These freshwater lakes provided numerous resourcesand were focal points for settlement. An obvious yet vital resource provided by themwas water, which was a valuable commodity in what was a relatively barren landscape.They also provided many other natural resources including: wildfowl, tuna (eels),kakahi (freshwater mussels), koura (freshwater crayfish), fish such as kokopu, parera(ducks), and plants such as raupo and harakeke (flax). This latter plant was a versatileweaving material that was a highly valued resource in the pre European era. Hugevolumes of the plant were harvested, with certain varieties being recognised for theirspecific qualities. Superior varieties of "rnuka1 flax were cultivated for garment making,while other varieties were grown for general weaving purposes and for themanufacture of cordage and nets. It is for this reason, that the flax growing today onold occupation sites such as Otakamiro, is regarded as an extremely important elementin the archaeological landscape.

The rocky coastal section of Muriwai Regional Park, that extends from Tokaraerae(Flat Rock) to the southern end of Maukatia (Maori Bay), is treasured today for itsdistinctive geological formations and its important sea bird breeding colony. Bothnatural features were also of major importance to the pre European Maori of thedistrict. The eggs and young of tara (terns), takapu (gannets) and akiaki (red billedgulls) were taken from Motutara and Oaia Island in both early and late spring. Avariety of titi or mutton bird, known locally as 'pakaha' was taken from the cliffsextending south to Te Henga in early summer, while the korora or penguin was caughtin late autumn.

The cliffs, and water worn boulders located in the Maukatia area provided one of themost important resources in the wider district. That is, a source of workable stone thatwas of such immense importance in the pre contact period. Adze 'roughputs' weremanufactured using basalt eroded from pillow lava at Maukatia. Grinding andpolishing stones or hoanga were then used to finish adzes in nearby rock pools. Onesuch place is found on a large rock in the intertidal zone at the southern end of the bay.Local basalt was also used to manufacture hand held weapons known as 'patuonewa',as well as such items as files, drill points and sinkers. A significant proportion of stoneartefacts found in west Auckland can be sourced to the Maukatia stone working site(Lawrence, 1989).

The whole cycle of resource gathering was regulated by 'rahui' or a form of tapu thatrestricted the use of natural resources . Some places were permanently excluded fromresource use. These included areas, in both the foredunes and on the coastal cliffs, thatwere declared tapu and set aside for human burial. A number of such places existwithin Muriwai Regional Park and their ongoing care is monitored by both TangataWhenua and Regional Park Service staff.

The natural resources and strategically important routeways associated with MuriwaiRegional Park were protected by a number of pa or fortifications which provide the

63

I most visible symbols of the area's past history of human occupation. These defensiveI positions were not merely places of refuge, but were also 'tohu rangatira1 or symbols ofI chiefly power and nobility. They still provide a direct physical and spiritual link withIf those ancestors who constructed and occupied them, and are thus of immense

f'• importance to the Tangata Whenua of the area. The Motutara area was protected by1 three pa. They included the headland pa of 'Otakamiro', the adjoining refuge locatedj. on Motutara rockstack, and the inland pa of "Matuakore1. This latter fortification?' protected the southern ridgeline pathway known as Te Ara Kanohi'8 which ran south

to Te Henga. The cultivations and resources of the area adjoining the dune impoundedlakes of Okaihau and Waitewhau were protected by 'Tukautu1 the well preserved palocated in "Houghtoris Bush'. The Muriwai Stream Valley, and in fact the wholesurrounding area, was defended by the large headland pa known as Te Korekore(Pulpit Rock).

It was from a point just north of Te Korekore that the first sighting of what is nowMuriwai Regional Park and its environs was made by the first European visitors to thearea. On July 28 1820 Reverend Samuel Marsden and a 'timber purveyor1 Mr Ewelsviewed Te One Rangatira' whilst on route to inspect the Kaipara Harbour entrance. Atthis time Marsden gave a vivid description of the desolate landscape that lay before himnoting - "the sandhills are very high and command a wide prospect on the sea and theinterior. There is no vegetation upon them and the sand shifts with the contendingwinds. They are several miles broad, and extend along the coast both to the right andleft further than the eye can reach" (Marsden in Elder 1932: 272). On November 121820 Marsden returned to the area, this time in the company of the CMS missionaries,Reverend John Butler, William Puckey and James Shepherd. Marsden and his partycrossed the canoe portage from Rangitopuni (Riverhead) and then walked westwardfrom Waimauku along the northern side of the Muriwai Valley. Reverend Butlerrecorded in his diary that, "a little before the going down of the sun we reached a smallvillage on the west side near the sea .....' this place is called Moodewye (Muriwai)"(Butler in Barton 1927: 101). He described the dune area beyond the village asresembling, "deep snow in winter .... an immense tract of sand, with a stunted shrubhere and there growing through" (Ibid).

Both Butler and Marsden made a number of interesting comments on the local Maoripeople. Butler commented that the occupants of Te Muriwai, "had never seen aEuropean, and the young of both sexes were filled with wonder and astonishment"(Ibid). Marsden noted however that the local people had been exposed to indirectEuropean influences which had brought change to both their diet and settlementpatterns!He observed that, "they had plenty offish and fresh potatoes, and... somehogs also amongst them" (Elder 1932: 316). Marsden also noted that they no longeroccupied the adjacent pa (Te Korekore). "The chief told us it now afforded them noprotection against their enemies since firearms had been introduced into New Zealand.He showed us where their enemies had fired upon them in the hippah (pa) with balls,and that the distance was too great for them to throw their spears" (Ibid: 272). Theinhabitants of the Muriwai area were obviously insecure at that time as a result of themusket raids which had begun in the district in 1818. Marsden noted that some of

'Te Ara Kanohi' or literally 'the pathway of the eyes' - so named because ofthe extensive views obtained of the whole coastline from this ridgelinepathway.

64

them, "had fled to this sequestered spot from the present war ..... they had not a singlehut built but lay down in the brush and fern" (Ibid: 316).

In spite of Marsden's comments this was a time of Ngati Whatua military prowess andconfidence, and in 1821 a large taua or war party assembled at Oneonenui to take partin a 'Amio Whenua1. This was a "marauding campaign around the central and southernparts of the North Island" (Kawharu 1975:5). This group also included some of thelocal Kawerau people led by Te Ngerengere. When this taua returned to the districtnine months later they found that many people had taken refuge there followingNgapuhi raids on both southern Kaipara and the Tamaki Isthmus. In late 1825Ngapuhi, while suffering heavy losses themselves, inflicted a major defeat on acombined Ngati Whatua force at Te Ika a Ranganui near Kaiwaka. After a brief periodof reorganisation Ngapuhi sent taua heavily armed with muskets to the Kaipara area toexact further revenge for past defeats. One group led by Te Kahakaha attacked NgatiWhatua at Kapoai (just south of Helensville), Kiwitahi (near Woodhill) and then atMuriwai. Here some of the local people were killed near Lake Paekawau and also inthe large cave beside Tokaraerae (Flat Rock) (pers. comm. Mr J Watene 1990). Thistaua then headed southward inflicting heavy losses on the Kawerau people occupyingthe coastline between Maukatia and Whatipu.

Following these attacks, Muriwai and the surrounding district was depopulated for adecade, as the local people sought refuge in the Waikato and lower Northland. In1832 the CMS missionaries Messrs Hamlin and King, "did not see one inhabitant orcooking fire between Kaipara and Manukau" (Sheffield 1963 : 41) After peaceagreements negotiated in 1835 and 1836, Te Taou under the leadership of MatiniMurupaenga resettled the Ongarahu (Reweti) area, while Te Kawerau under theleadership of Te Ngerengere returned to Parawai beside the lower Waitakere River.Both groups now occupied the Muriwai area only on a seasonal basis in conjunctionwith resource gathering. ' ........ ....... ......

The "Musket Wars' had left the tangata whenua of the study area devastated. Thiscreated the desire to attract Pakeha to the area and the conditions in which themissionary message seemed more attractive than in the past. In 1839 Reverend JamesBuller, the Wesleyan missionary based at Tangiteroria at the head of the NorthernWairoa River, began to visit the kainga of Southern Kaipara. By 1841 he wasbeginning to make an impact in the area, and in April of that year he baptised Te OteneKikokiko the leading Rangatira and Tohunga of Te Taou. This increased the pace ofChristian conversion, so that by 1845 the majority of the Maori inhabitants of the areawere practising Christians. In this period Reverend George Selwyn, the Bishop ofNew Zealand, visited the Muriwai kainga. He gifted the local people a fig tree whichgrew for many years on the old village site near Lake Okaihau."

Crown and individual land purchases had begun in the Upper Waitemata Harbour areain 1844, and Crown land purchases began in Southern Kaipara with the purchase of theWaikoukou Block near Waimauku in 1851. All of the land in the Muriwai arearemained in Maori ownership in this period. The inhabitants of the study area cameinto increasing contact with Europeans and .their technology in the 1850's as European

9 Offspring from that tree can still be found growing beside Lake Okaihau (pers.comm. S. Houghton, April 19.94)

i)i

65

settlement began in the south eastern Kaipara district. Most importantly the traditionalnature of land tenure and resource use patterns in the area was dramatically altered as aresult of the Native Land Acts (1862 & 1865). In 1865 a Native Land Court wasestablished at Te Awaroa (Helensville) to determine 'ownership1 of customary land inthe Kaipara district, with Certificates of Title being issued to rangatira for specific landblocks on behalf of local hapu. Most of the Maori land blocks in the wider Muriwaiarea were investigated by the Court in 1866-1871. Investigation of the land blocksthat now make up Muriwai Regional Park began at this time, although the process wasnot to be completed until the early twentieth century. The greater part of the parklandlies on part of the 'Taupaki' Block investigated in 1867, and on the 'Motutara' Blockfirst investigated in 1871. The land blocks which include the duneland adjoining thelower Muriwai Stream were among the last to be investigated in the district. ThePuaha o Muriwai' Block which is on the northern side of the stream mouth wasinvestigated in 1897, while the 'Paengatohora1 Block on the southern side of the streamwas investigated as late as 1915.

The section of the regional park that includes the Muriwai Golf Course is located onthe north western edge of what was the Taupaki Block. This large land block of 5211ha extended five kilometres to the south, and eastward to the Kumeu River. It hadbeen the subject of a major dispute in 1854 between Te Kawerau and their Waiohuarelatives on the one hand, and the Te Taou sub tribe of Ngati Whatua on the other.

'*' Governor Grey had personally adjudicated on the dispute with the assistance of theNgati Whatua rangatira Apihai Te Kawau, then resident at Orakei. "The agreementwas then that the Governor and Apihai should be entrusted with the land. TheGovernor said do not sell it until disputants agree to sell"(NLC Kaipara MB 1:78,1867). A compromise was ultimately arrived at between the parties and title to theland was granted to four rangatira on behalf of the respective groups who had aninterest in the block. They included Paora Tuhaere and Te Wiremu Reweti Te Whenuaof the Te Taou hapu of Ngati Whatua, Te Keene Tangaroa of the Te Marijgamata hapuof Ngati Whatua, and Te Waatarauihi Tawhia of Te Kawerau. The eastern half of theTaupaki Block was subdivided and sold by its Maori owners between 1867 and 1870.The western half of the block, which totalled 2792ha in area, was less accessible andwas to be retained in Maori ownership for another decade.

Between 1870 and 1871 most of the customary Maori land in the Muriwai area wassurveyed and investigations of title were undertaken for each block . Certificate ofTitle to 'Oneonenui1 and the blocks lying north of the Muriwai Stream was awarded torangatira representing the wider Te Taou hapu who occupied both southern Kaiparaand Tamaki. Title to 'Muriwai1 and 'Kahukuri', the two blocks south of the MuriwaiStream, was awarded to the Ngati Te Kahupara section of Te Taou led by NoperaWaitaheke, Tautari Ngawaka, Te Kepa Matu and Paiura Patu. In February 1871'Motutara No. 1', or the land surrounding Otakamiro Point, was investigated by theNative Land Court. Title to this 37 ha block was granted to Hori Winiata Nopera andseven other rangatira of Ngati Te Kahupara. At this time their main cultivations werelocated on the Muriwai block and Hori Winiata Nopera noted that Motutara was, "a

| pig run" (APG Gazette 1871: 18).

!' Census information indicates that the Muriwai area was occupied at this time by small! groups of both Ngati Te Kahupara, led by Te Kepa Matu and Paiura Patu; and Te

J 66

I Kawerau led by Te Waatarauihi Tawhia and Te Utika Te Aroha. Maori from othertribal areas also occupied the district during this period while engaged in gum digging.They included people of Te Rarawa and Te Aupouri from the Far North, as well as TeArawa from the Rotorua district. One group from the Arawa sub tribe of NgatiWhakaue occupied the Muriwai Valley for over twenty years. Led by Hamuera TeRakato these people established a small kainga on the shores of Roto Okaihau(Houghton's Lake). Their occupation of the land was formalised in 1871 when theywere gifted the 23 ha "Pukemokemoke1 Block adjoining Roto Okaihau by Tautari ,Ngawaka and Nopera Waitaheke.

The 1870's and 1880's brought major change to the Muriwai area as Europeansettlement began. In 1870 John and Annie Foster established a flax mill at Okiritoto onthe Muriwai Stream. They later purchased a substantial part of the Kahukuri Block,and in 1888 opened a general store and gum store at Waimauku. Flax fromthroughout the Muriwai area, including what is now the regional parkland, washarvested and taken to the mill for processing. It did not however operate for long asmuch of the flax on the Muriwai Block was destroyed by fire. In October 1875 theHarkin's Point^ - Helensville railway was opened, and in 1881 the rail link withAuckland was completed. This meant that the previously inaccessible land west ofWaimauku became more attractive to European settlers.

In 1878 the western portion of the Taupaki Block was leased by its Maori owners to( Albert Walker 'of Auckland, Gentleman'. His lease included the right of purchase

which he exercised in March 1879 for £1500. This transition marked the beginning ofthe transfer of Maori land on what is now Muriwai Regional Park to Europeanownership. Walker sold the 2792 ha block later in the same year to ChristopherGalbraith 'of Oamaru, Timber Merchant1. In September 1882 the land was resold toDavid Henderson 'Blacksmith1 and David Miller 'Contractor1 of Oamaru. Under theirownership the western portion of the Taupaki Block was subdivided into 37 allotmentsand offered for sale by public auction on February 21 1884. Several allotments soldimmediately, although the sale of blocks that lacked road access was not completeduntil 1887. Thomas Edwin Roe 'of Auckland, Bush Manager' purchased the forestedallotments between Taiapa Road and the Mokoroa Stream and began a major timbermilling enterprise that was to operate until the late 1880's. Allotments 31 and 33 whichadjoined the Motutara Block were purchased by William Joseph Moore 'of SpringfieldCanterbury, Collier Overseer' in October 1885. Moore, his wife Mary, and theirchildren, constructed a house on the property where they settled in September 1888,becoming the first Europeans to occupy land that now lies within Muriwai RegionalPark. Over the next few years the Moore family purchased more land in the Motutaraarea, including the 214 ha allotment 37 of the Taupaki Block, or what is now MuriwaiGolf Course.

In the 1890's the Muriwai area had few permanent Maori residents. The Ngati TeKahupara people now led by Watene Tautari had settled at Orakei near Auckland.They only visited Muriwai and Motutara periodically from this time to gather kaimoanawith their Te Taou relatives from Reweti. The Kawerau people now led by Te UtikaTe Aroha had settled permanently on the 1180 ha Waitakere Native Reserve south of

10 Harkin's Point is located just north of the mouth of Brigham's Creek.

67

Tirikohua. Following the sale of the western portion of the Taupaki Block they nowhad no land in the Muriwai area. They still however camped at Motutara, andespecially at Maukatia while gathering kaimoana and mutton birds in summer. The1890's saw the sale of much of the remaining Maori land in the Muriwai area. InJanuary 1890 Motutara No. 2, (the inland portion of the Motutara Block), was sold toAndrew Stewart and Richard Garlick who had leased the land since 1884 to millpohutukawa and other timber. Following this sale the Crown moved to secure theMotutara No. 1 Block to protect beach access and what was an area of obviousrecreational potential. On October 15 1890 this 33 ha block was purchased by theCrown from Watene Tautari, Hakuene Ratu and Hori Winiata for £81, thus formingthe focal point of what was later to become known as Motutara Domain'.

During this period Oneonenui and Muriwai, the two large land blocks in the MuriwaiValley were also purchased from their Maori owners. Oneonenui was purchased inJune 1884 by Richard Waters of Waimauku and then resold to the local contractorJohn Foster and his financial partners in 1891. In 1905 Oneonenui was purchased byJames Fletcher who was then a timber mill manager at Aratapu on the NorthernWairoa River. Sadly James Fletcher died soon after the block was purchased, althoughit was subsequently developed by his family who have now been associated with thedistrict for over a century. Fletcher had earlier purchased the Puaha o Muriwai Block,or what is now the part of the regional park sited north of the Muriwai Stream inSeptember 1903. Certificate of Title to this duneland had been awarded in 1897 to WiHoete Maihi and others of the Te Mangamata hapu of Ngati Whatua then resident atHaranui northwest of Helensville. They claimed their right to the land through theoccupation of Tikiarere kainga by their ancestors until the 1860's. The Muriwai Blockwas purchased in the mid 1890's by Te Aira Rangiarua the wife of Auckland SolicitorEdmund Dufaur. The land was transferred to Dufaur in 1899, and then in 1900 toChristopher Ingram of Avondale who began the development of the property with thehelp of his sons David and John: = --- -

In the early 1900's the Motutara area remained isolated with access being along a'bullock road' that was impassable in wet weather. It was not until 1914 that a road tothe area was formally surveyed, and not until 1918 that it was 'formed1. It was for thisreason that the large properties near Motutara remained as extensive pastoral runs at atime when farms nearer to Waimauku were running dairy herds supplying the localWaitemata Dairy Co factory established in 1904. The largest of these properties wasthe farm developed by the Hon. Sir Edwin Mitchelson in the first two decades of thetwentieth century. Born in Auckland in 1846, Sir Edwin had founded a flourishingkauri gum and timber milling business based at Aoroa near Dargaville. He was MP forMarsden 1882-1887 and Eden 1887-1896, during which time he held the positions ofMinister of Public Works and Native Affairs, Postmaster-General, Commissioner ofCustoms and Electric Telegraph Commissioner. On retirement from national politicsSir Edwin was very active in Auckland local body politics being Mayor of Auckland1903-1905, and Chairman of the Auckland Harbour Board 1905-1909.

In the late 1880's Sir Edwin moved to Auckland, where he had established the businessheadquarters of E Mitchelson & Co in Little Queen Street, and he and his wife Sarahsettled in a large home in Remuera (now Baradene College). At times they travelledout to Motutara where they spent holidays on the Motutara No. 1 Block that had been

68

purchased by Sarah's brother William Wilson and his wife Ann in 1897. SarahMitchelson suffered badly from asthma, although her condition seemed to improvewhen on holiday at Motutara. For this reason the Mitchelson's decided to purchase theMotutara Block from the Wilsons in February 1901 so that they could spend more timenear the 'ozone rich' breezes of the Tasman Sea (pers. comm. Rangi Mitchelson, April1994).

Sir Edwin and his wife initially had a holiday cottage built on the property and thenthey constructed the large homestead which was named "Oaia". An extensive gardenwas developed between the house and the lookout above Otakamiro Point. Many ofthe larger exotic trees planted by Sir Edwin at this time, including macrocarpas, gumsand Norfolk pines still remain in the regional park. In the period between 1905 and1918 the Mitchelson's purchased a number of the allotments on the old Taupaki Blockas well as the Tirikohua and Waitakere No. 2 Maori land blocks to the south. A 1215ha farm was developed and managed by Sir Edwin's son Edwin Parore (Rangi)Mitchelson. This property, centred around a shearing shed and stockyards in OaiaRoad, *1 was operated as an extensive pastoral run with stock being driven to therailway at Waimauku for sale. The Mitchelson property ran a Romney stud flock, withsheep numbers rising from 1450 in 1910 to almost 2500 in 1920. In 1921 most of theproperty was purchased by the Crown at £11 per acre to create the 'MotutaraSettlement' for returned soldiers. At this time the Mitchelsons ceased farmingoperations but retained the Motutara Block. Following the death of Sir Edwin in early1938 it was sold to the Auckland Returned Soldiers Association Inc. who sold it toHorace Massey in October 1943. Massey sold the property in 1947 to an Aucklandsolicitor Norman Spencer. The Mitchelson family association with the regionalparkland is commemorated in the names of the 'Mitchelson Block1 which lies within thePark, the 'Mitchelson Track', and in the nearby "Edwin Mitchelson Road'.

— The recreational potential of the Motutara area had been recognised by the Crown in| the 1890's, although the land had remained as'Waste Land of the Crown'and

technically available for sale. In 1892 Motutara, "came into prominence on account ofthe large 'pod' of whales coming ashore at the spot," (L & S District Office File 8/89,1908) and growing numbers of campers began to visit the area from this time. In July1908 a request was made from, "a number of settlers and visitors to the GovernmentReserve at Motutara ... to have the Reserve gazetted and vested in Trustees" (Ibid). Itwas stated that, "as this portion of the coast is being visited by large numbers of peopleduring the summer months and holidays, there is no doubt it is fast becoming much infavour as a health resort, being within one hours drive from Waimauku RailwayStation" (Ibid). It was also noted that the Hon. Sir Edwin Mitchelson was lookingafter the unofficial reserve and that visitors were, "indebted to his kindness ... forspaces to erect tents on & c." (Ibid).

Mr Hugh Boscawen of the Department of Lands inspected the area in mid 1908. Hereported that up to 120 campers were using the block each summer, and thatMotutara's "great charm (was) the pohutukawa trees and its wild state" (Ibid).

Sir Edwin Mitchelson financed the development of an "all weather surface" onOaia Road using hand placed, locally quarried sandstone rocks (pers. comm. S.Houghton, April 1994).

69

Boscawen recommended that the land be formally reserved, and on 17 December 1908the "Motutara Domain1 was gazetted by the Crown as 'a reserve for recreation1.

The Domain was initially administered by trustees including Vincent Kerr-Taylor,Rangi Mitchelson and John Foster jnr. Then in October 1923 an Order in Councilcreated the Motutara Domain Board which was to be elected by local residents. At apublic meeting at Waimauku Hall the first Board was elected. It included five localrepresentatives: Richard Hoe, Joseph Copeland, Frederick Summers, ReubenCushman and Thomas Moore. Mr George Henning was appointed as therepresentative of the Auckland Automobile Association and Mr R Glasgow wasappointed as the Waitemata County Council representative. This body was toadminister the domain until 1969 when the Auckland Regional Authority took overmanagement of the land as a regional park. Those who served for long periods on theDomain Board included: Thomas Moore (1923-1947), Charles West (1928-1952),Harold Houghton (1935-1960), Walter Reber (1948-1969) Malcolm Andrew (1952-1969), Mervyn Jonas (1952-1969), and Arthur Sorrenson (1952-1963).

In the period between 1909 and 1923 little development took place on the Domain,although some improvements were introduced using a £50 grant from the Departmentof Lands. The Domain was fenced, two conveniences and dressing sheds wereinstalled, and several footpaths were formed on Otakamiro Point. In 1915 the DomainBoard received a £100 grant to plant eighteen and a half tons of marram grass on theforeshore of the northern half of the reserve. With the formation of the Waimauku-Motutara Road in 1918, and the introduction of motorised transport, the Motutaraarea became more accessible to the wider public and increasing numbers of peoplebegan to visit the area. To cater for the growing number of visitors, the Boarddeveloped a grassed camping area, and installed a rudimentary water supply.

Many of those who visited Motutara Domain at the time were holiday makers stayingin either of the two accommodation houses that had been established in the area. Alarge guesthome had been established on the Muriwai Block near Lake Okaihau by theIngram family in 1912. This facility had originally been constructed by three Aucklanddoctors, including Dr Erson and Dr Scott on a site leased from Edmund Dufaur in1899. It had been developed as a 'sanitorium' for the treatment of T.B patients, who itwas thought would benefit from the ozone rich sea air and immersion in the hot blacksands of the nearby dunes. The sanitorium operated for only a brief period until itbecame the Ingram family home, and later Ingrams Guesthouse. Managed by John andMary Ingram (nee Bethell), it was based on the successful guesthouse operated byMary's family at Te Henga (BethelTs Beach). It was however run on a much granderscale and included a formal dining area, ballropm, and a croquet green. The activitiesof guests staying at Ingram's Guesthouse were focused on Lake Okaihau and theMuriwai Stream, although they were often transported to Motutara Domain via boththe beach and Oaia Road to enjoy recreational pursuits.

In 1912 the 523 ha Muriwai Block was sold to Frederick Mulcock, who farmed theblock and operated the guesthouse as only a secondary concern with help from hisneighbours James and Ellen Rutherford. They managed the property until 1918 whenMulcock subdivided the Muriwai Block into five allotments and offered it for sale.During this time the Rutherfords purchased a small stand of kauri trees near the

70

Toroanui Falls from the Fletcher family to ensure its preservation as most of the otherKauri in that vicinity had been milled. They also become the first European owners ofthe duneland block lying south of the Muriwai Stream mouth . It was the 89 haPaengatohora Block which was purchased from Wiremu Watene Tautari and others ofNgati Te Kahupara who had been awarded title to it in March 191612. in December1918 Lot 1 of the Muriwai Block (which included the guesthouse), was sold to HoraceSalter of Paihia. Because of difficulties resulting from poor year round road access andthe economic effects of World War I, the guesthouse had become an uneconomicproposition and it was closed in 1920. At this time the property was sold to HarryWheeler of Waitakere who farmed the block and used the guesthouse as a familyhome.

The remainder of the Muriwai Block, including allotments 2-5 (386 ha), had beenpurchased as a speculative venture by Edward Grimwade, Florence Reimers and JohnRoche of Auckland in March 1918. In April 1921 the property was transferred to J H(Harold) Houghton who had settled there in April 1920. He then set about clearing theheavy scrub on the land and developing the farm which was to become known as'Muriwai Downs'. He maintained a small dairying unit and ran drystock which weredriven to Waimauku Station to be railed to Auckland for sale. As previouslymentioned Harold Houghton served for a long period on the Domain Board and playedan important part in the local community, as have his family who still farm the propertytoday. At the same time as the Houghton property was being developed, returnedsoldiers took up the nineteen properties included in the Motutara Settlement1 on whatwas the old Mitchelson farm. Most found the farming of these dry and exposedproperties difficult, especially as the nation entered a major economic depression. As aresult, many of them and their wives, "fell ill both physically and mentally with theexhausting struggle for existence" (Rea 1963: 34-35). In the 1930's several of thesefarms were abandoned and they were later amalgamated into larger, more economicunits: "" ' - " '" " • ' - • • - " • ' • • •

In 1925, while local farmers were struggling to develop their properties in whatremained an inaccessible area, a new guesthouse was developed near to MotutaraDomain by Martin Blanchfield and several local financial backers. 'Muriwai House1

was initially a very successful venture and brought an increasing number of visitors tothe area, in particular after the production of a publicity booklet 'Muriwai the Beautiful'in conjunction-with the Brett Printing Co Ltd. It also brought the names 'Muriwai' and'Muriwai Beach' into common usage, with the result that Motutara' the traditionalname for the parkland area disappeared from use except among the local community.

As was the case with the earlier guesthouse, the activities of visitors staying at'Muriwai House1 were largely focused on Motutara Domain and the area that nowmakes up Muriwai Regional Park. A feature of the area then, as is the case today,were the views obtained from Otakamiro Point. .They included: views of the beach andPah Hill' (Te Korekore) to the north, Oaia Island, and 'the wild coast' to the south. Ofparticular interest were the caves and other landscape features that existed in the MaoriBay area before it was impacted by quarrying. They included: "shelves, ridges, crags,

12 Title to this block was claimed from descent from .Rangiawhiowhio an ancestorwho occupied the area following the ;'Te Taupaki' peace agreement.

71

If

KI

faces almost human, castles in the air, knobs, rings, cracks, spires, points, grooves,dykes, all in a kind of regular irregularity1." (Brett Printing Co, c. 1926:5). The areawas also seen as being an "ideal spot for photographers' and as a good place fromwhich to 'view the wild seabirds1. It is of interest to note however that in the mid1920's, "their home (was) on the little island of Oaia" (Ibid:5).

Nearer to the beach, fishing was a favourite activity on "Flat Rock1, where "at the rightstage of the tide good catches are always made" (Ibid:2). Here in rough weather the"blowhole" could also be observed giving "a geyser-like display". On the beach itself'surf bathing' was the favoured activity, although many people enjoyed long walks tothe stream mouth looking for driftwood, whalebone and ambergris. Others took aspade and dug for, "the edible toheroa found in large numbers all along the beach"(Ibid:2). Many visitors to Motutara Domain went on the all day inland walk beyondthe guesthouse to the Wheeler property. Here, if accompanied by a guide from"Muriwai House", they could see "the kauri gully containing over 600 kauri treeswhich (was) to be preserved as a scenic resort" (Ibid: 14-16)13. They could see'Selwyn's fig tree', the maiden-hair fern glades, the two lakes and the waterfalls on theMuriwai Stream. Some visitors walked to the lower reaches of the Muriwai Stream,not to view its natural wonders, but rather to enjoy, "the excellent shooting .... (of)pheasants, quail, plover, wild duck, and other game to be found in abundance"(Ibid: 11).

During summer months arrangements could be made at Muriwai House" to motor thefull length of the beach at low tide. As more Aucklanders acquired cars 'motor picnics'became more popular at Motutara and many people took private cars onto the beachvia a concrete ramp installed at Flat Rock by the Auckland Automobile Association.The first vehicle to venture onto Muriwai Beach had been a "Velie" driven by localfarmer William Jonas in 1918. It had become stuck in the sand and had to be hauledoff the beach by horses. Drivers were warned in the 1920's to, "beware of stoppingtheir cars near the stream, as the sand is a bit soft and the wheels soon sink in"(Ibid: 11). This hazard has remained a problem, as subsequent Domain Caretakers andRegional Park staff could testify. ;

In the early 1920's the surface provided by Muriwai Beach at low tide came to berecognised as one of the best available for motor racing, and in 1922 the NZ MotorCup race of 50 miles was held there. Organised by the Auckland AutomobileAssociation, the annual two day Muriwai motor racing carnival was New Zealand'spremier motor sports event for nearly a decade. It attracted large crowds who came bycar, bus, and in some cases aeroplane to Motutara Domain. On February 21 1925, "sixthousand people attended Saturday's racing most of them camping out in thesandhills overnight" (Buffett, 1985). By the late 1920's Muriwai Beach was howevercoming under increasing criticism as a motor racing venue because of, "uncontrolledcrowds, a poor surface to race on (largely as a result of the activities of toheroadiggers), and most of all the axle snapping Muriwai access road" (Ibid). During theeconomic depression of the 1930's the popularity of Muriwai as a motor racing venue

13 This impressive reserve, seen as "the best place around Auckland to get a goodview of the noble kauri trees", was preserved by Harry Wheeler even when he wasin serious financial difficulties with the guesthouse. Sadly after he sold theproperty to the Harrison family in 1929 most of the kauri was milled. Whatremained was preserved by Harold Houghton who purchased the property in 1937.

72

faded, although motor sports events (including hill-climbs on Watea Road) were heldperiodically until the 1960's.

During the first decade of the development of Motutara Domain another event of notetook place on Muriwai Beach in the vicinity of the present day regional park. OnSeptember 28 1916 the 'Albany1, a small steamer of 10 tons register, was beached atthe mouth of the Muriwai Stream to carry out engine repairs. "When being refloated arope fouled the propeller at a critical moment, and the steamer was caught by thebreakers and cast ashore, becoming a total loss" (Ingram 1972: 326). No lives werelost and the vessel's engines were salvaged. Between 1865 and 1908 seven othervessels had been wrecked on Muriwai Beach north of the stream, with the loss ofeleven lives. In February 1863 thirteen bodies from the wreck of the HMS Orpheus atthe Manukau Heads had been washed ashore near Motutara. They were buried byReverend William Gittos and local Maori on the northern side of the MuriwaiStream.14

In the 1920's up to 1200 vehicles and 5000 people were visiting Motutara Domain attimes other than during motor racing events (L & S District Office File 8/89, 1927). Inorder to cater for this growing number of visitors the Domain Board extended thecamping area, and allowed Mr Len Foster of Waimauku to build a small store near thebeach access road in 1924. This store operated until January 25 1926 when during amajor flash flood it was "undermined and washed out to sea" (Ibid: 1938). It wasreplaced by another store located at the eastern end of what is now the beach accessroad. In 1928 the Board appointed a resident caretaker Mr H Ralph who was providedwith a small cottage on the domain and placed on a salary of £1 per annum. Under hiscontrol a number of improvements were carried out to the Domain over the nextdecade. A 'community cookhouse1 was constructed on the camping ground, a hotwater supply for visitors and campers was installed, concrete steps were constructed toprovide beach access, and 'electric light' was introduced into the campground. Treeswere also planted throughout the Domain to provide "shade and shelter". Theseincluded 533 native trees kindly donated by Mr William Wilson.

In this period campers were charged a fee of l/6d per tent per day, or 5 shillings perweek. The income from this barely covered the costs of maintaining the Domain so theBoard began to investigate alternative sources of revenue. It proposed theintroduction of a toll of one shilling per vehicle visiting Motutara Domain in order, "todevelop the domain and the Bush Road1^ (Ibid:1927). The Department of Landsrefused to allow the collection of this toll but instead allowed the Domain Board toinstitute a one shilling per vehicle parking fee in the Domain. This became the Board'smain source of income in the pre war era, bringing in nearly twice the amount taken incamping fees. In 1932 the Board also allowed several regular campers to construct'cottages' on the Domain with the annual rental set at £5 per annum. By 1933 seven ofthese baches had been built to the north of the camp ground on what was to becomeknown as 'Skid Row'. Even though these baches were constructed on skids, and"could be removed at any time", (Ibid: 1933) the Department of Lands objected

14

15

The site was marked by a plaque located near the old cable hut.

The 'Bush Road' was the section of Motutara Road between the Oaia Road turnoffand Motutara Domain.

73

•?. strongly and ordered all baches to be removed within five years. The Domain Board> initially agreed, but later sought an extension until 1950. Further baches were

constructed on "Skid Row1 throughout this period and they were to be an ongoingsource of contention between the Board and the Department until after the ARA tookcontrol of the Domain in 1969. In another attempt to increase income the MotutaraDomain Board examined the possibility of purchasing part of the Mitchelson Estatesouth of Motutara Road and developing a holiday camp using Public WorksDepartment huts. The Board was, however, unable to secure either the land or thehuts, and the proposal lapsed.

During the economic depression of the late 1920's and early 1930's visitor numbersdeclined and little development work was undertaken on the Domain. In the mid1930's Motutara Domain again became a popular holiday destination andimprovements were undertaken by the Domain Board. The bush section of MotutaraRoad was metalled, tree planting was undertaken in the camping ground, andMitchelson Creek1 ̂ which flowed through the Domain was diverted to preventongoing flooding problems. At this time the camping area was enlarged by thedevelopment of several large terraces above Motutara Road, concrete steps wereconstructed to improve beach access, and most importantly "life-saving gear1 wasinstalled at the southern end of the beach. In February 1938 Charles Allen the DomainBoard Secretary reported proudly to the Department of Lands and Survey - "MotutaraDomain is becoming increasingly popular. As a holiday and health resort it is probablyunequalled by any other Domain in the whole of New'Zealand" (Ibid: 1938). In 1938Mr J Wiggins was appointed as Domain Caretaker. He also secured trading rights onthe Domain and opened a Post Office-Store and Tearooms inland and to the north ofthe beach access road which had been formed by the AAA in the late 1920's.

One of the most important developments carried out on what is now Muriwai RegionalPark in the 1930's was the sand dune reclamation work undertaken by the Public —Works Department and the New Zealand Forest Service. The dune country behindMuriwai Beach had long consisted of open, active duneland, as evidenced by thedescriptions of the early missionaries. However as a result of the removal of scrub andforest cover behind the duneland, the introduction of stock, and increased visitornumbers, sand had begun to move further inland from the early 1900's. By 1930 itthreatened to engulf the main highway and railway line north of Reweti. In June 1934the Ministry of Public Works gazetted notice of intention to take approximately 4020ha of duneland north of Motutara for 'sanddune reclamation purposes'. This includedthe duneland between the campground and the Muriwai Stream, running inland toLake Okaihau. It also included the Puaha o Muriwai Block and part of the PuketapuBlock lying north of Muriwai Stream. This area was planted in lupins and marramgrass by the New Zealand Forest Service which had been developing Woodhill Forestfrom 1928. When the dunes had stabilised, the NZFS planted the inland portion ofwhat is now the Regional Park (lying north of Motutara Domain) in exotics. Thiswoodlot, which was planted in 1943-1947, was made up predominantly ofPinuspinaster (33 ha) and also included smaller plantings ofPinus radiata (15 ha) andP/wwsmuricata (3 ha).

16 Sometimes also referred to as 'Maori Creek'.

74

The 1940's saw few developments of any note on Motutara Domain. Between 1942and 1943 the northern part of the Domain, and what is now Muriwai Golf Course, wasoccupied by the US Army Mobile Company who were undergoing beach landingtraining for the Pacific campaign. Many of these troops Were subsequently to lose theirlives during the attack on Tarawa, Kiribati (Gilbert Islands), in the Pacific. During thisperiod public access to the beach was limited and Motutara Domain could only be usedbetween sunrise and sunset. The 1940's also saw the beginning of quarrying on what isnow Muriwai Regional Park, and several important changes in the status and tenure ofland in the vicinity of the Park. In 1945 control of the foreshore area bordering theDomain was vested in the Domain Board. In 1949 a small area north of the MuriwaiStream was set aside by the Crown for the Trans Tasman telephone cable terminal, andthe NZFS land south of the stream was gazetted as a wildlife refuge.

In the early 1940's the Motutara Domain Board had made several unsuccessfulattempts to purchase that part of the old Mitchelson property adjoining the Domain inorder to extend the campground and to provide better access to Otakamiro Point. Thisproperty had been purchased by the Auckland RSA from Sarah Mitchelson in 1938with the intention of developing, "a community housing scheme and camping sites formembers" (Motutara Domain File, L&S Dept 1939). Although the old 'Oaia1

Homestead and the lower part of the property were used by members in the war years,the priorities of the RSA lay elsewhere and the property was offered for sale to theDomain Board. Before negotiations began, however, the 59 ha property waspurchased for £4,000 by an Auckland solicitor Mr Norman Spencer in 1947. MrSpencer was appointed to the Motutara Domain Board in 1952 and was to have asignificant impact on the development of the Domain.

Soon after the purchase of the property, Mr Spencer subdivided a large portion of it,while retaining the 'Oaia1 Homestead and the land surrounding it. The development ofthis subdivision was to have a number of important impacts on both'Motutara Domain'and the surrounding area. It resulted in the addition of land to the southern portion ofthe Domain and ultimately greatly increased the size of the resident Muriwaicommunity . Between 1950 and 1958 Mr Spencer.gifted several sections to theDomain, and made reserve contributions exceeding the minimum requirement of theland subdivision provisions. This resulted in the addition of 22 ha to the Domainincluding the 13 ha 'Mitchelson Block'. In order to fund the construction of an accessroad (Watea Road) to the southern part of the subdivision, a number of sections weredonated to the WCC for sale. At this time Mr Spencer also gifted the quarry aboveMaori Bay to the County, on the condition that a royalty of 10 cents per cubic yard onall rock quarried be paid to the Domain Board. It was intended that this quarry, whichhad been operated briefly in the late 1940's by Mr Wilton, was to operate for only tenyears and was to be reinstated following its closure.

In the 1950's Muriwai became an increasingly popular venue for day trippers andholiday makers as more Aucklanders acquired motor cars: To cater for these peopleand the growing local community^, the Domain Board initiated the development of anumber of new facilities on the Domain. This work was undertaken in conjunctionwith local organisations, most notably the Muriwai Progressive Association, and

By 1952 the permanent resident population of 'Muriwai Beach1 had risen to 148.

75

fe;

I

included the introduction of tennis courts, a Scout Hall, a First Aid Centre and achildrens paddling pool. Most importantly, in 1950 the Domain Board approved theten year lease of a 0.4 ha section within the Domain for the development of a surflifesaving clubhouse. The Muriwai Surf Lifesaving Club had originally been formed in1939 but had gone into recess during World War n. It was reformed in 1948, "at theinstigation of George Hilton the Waimauku Stationmaster who had been netting fishwith several friends who had got into difficulties" (Rea 1963: 29). Surf carnivals beganat Muriwai in 1951, and provided the Motutara Domain Board with an importantsource of income. The Surf Lifesaving Clubhouse was constructed by voluntary labourin 1953, with much of the furniture being donated by Mr Spencer from 'Oaia'homestead. The Muriwai Surf Lifesaving Club has continued to make a hugecontribution to public safety in the area until the present time. Today it is one of NewZealand's leading lifesaving clubs and it still stages major events.

Another important development in the Muriwai area in this period was the formation ofthe Muriwai Golf Club. In 1957 the NZFS agreed to lease 64 ha of dunelandimmediately north of the Domain to the Golf Club for 33 years. The club subsequentlydeveloped a fine clubhouse and one of the best golf courses in the Auckland Region. Itis of interest to note that much of this development took place under the direction ofthe club's Secretary-Manager Mr Innes Kerr-Taylor, a nephew of one of the firsttrustees of Motutara Domain Mr Vincent Kerr-Taylor. In 1972 the Golf Course, andthe 129 ha State Forest of which it was part, were reserved by the Crown 'forrecreational purposes' and then added to the Domain in 1974. At this time the Ministerof Lands granted the Muriwai Golf Club a perpetually renewable 21 year lease overpart of the Domain.

By the early 1960's the Domain was, "becoming increasingly popular as a picnic areafor the day tripper from the city" (Auckland Star 17 April, .1,9.62). This increase inpublic usage led to the development of additional facilities on the Domain and placedincreasing pressure on the natural resources of the area. It also ultimately led to majorchanges in the administration and management of the Domain and its environs. Thisperiod of change was symbolised by a name change for the Domain and a major changein its management. In 1960 the Department of Lands and Survey changed the name ofMotutara Domain to Muriwai Beach Domain1, "as the area was more widely known bythe public as Muriwai Beach" (L&S Dept File 8/3/94, December 1977). Until 1969 theDomain continued to be managed by the locally elected Domain Board who introduceda number of improvements. These included: the construction of a new Caretaker'scottage and additional public conveniences, and the installation of a chlorinated,reticulated water supply from the WCC bore in Motutara Road. The Board, inconjunction with the Department, also undertook erosion control work to deal withwhat was becoming a major problem south of the Muriwai Stream.

The Department of Lands and Survey had been concerned about the administration ofMuriwai Beach Domain from the early 1960's, in particular because of the ongoingproblems relating to the 'Skid Row' baches and the proposal to develop a 'beachcottage subdivision'on the north eastern edge of the Domain. In late 1967, when theterm of the Domain Board was due to expire, the Commissioner of Crown Landsentered negotiations with the WCC which agreed in principle to accept control of theDomain. (L&S Dept File, DOC Archives 8/3/94, Oct 1967). At this time the newly

1

76

formed Auckland Regional Authority indicated its willingness to take control of the 53ha Domain, "as it constituted a facility of regional significance" (ARC Regional ParksService File 915, August 1967). The Department accepted this offer and the ARAformally accepted control of the Domain on June 4 1968 subject to certain conditions.These included the requirement that the Crown take full responsibility for the removalof all baches from the Domain, and also contribute to the cost of foreshore erosioncontrol work to be undertaken by the Authority. All funds of the Domain Board wereto be transferred to the Authority, and it was also to take over responsibility for allexisting tenancies and licences.

Physical control and possession of Muriwai Beach Domain was undertaken by the IARA on April 1 1969 under an agreement with the Crown that also provided for the 'foreshore land (extending north to the 8km mark on the beach and east to ForestryRoad) to be transferred progressively to the Authority as NZFS operations ceased.The development of the Domain began immediately under the direction of Phil JewARA Manager, Parks and Bert Blumhardt ARA Parks Officer. Work was undertakenand supervised by the Muriwai Resident Superintendent Ken Lovell (who hadpreviously been the Domain Caretaker) assisted from late 1971 by Park Attendant JimDent. Development work initially centred around the installation of signage, amenityplanting, and the upgrading of conveniences, car parking, access reading, and campground facilities. A great deal of effort was also expended by the Authority during thisperiod in controlling foreshore erosion and instability which had been an ongoingproblem at Muriwai from the late 1950's.

By 1969, "a serious foredune - erosion problem had arisen .... and threatened to engulfthe picnic ground (and surf club)" (Jew 1970:1). The ARA adopted a three foldapproach to the problem with the assistance of NZFS officers. Firstly the entireforedune area was reshaped using earthmoving machinery, and 1000 metres of twometre high batten fencing were constructed around the margins. Public movement onthe foredune was then restricted to specific accessways surfaced with 2000 cu.m ofclay. Finally all fenced areas were planted with marram grass and yellow lupin. Thiswork was to be ongoing throughout the 1970's, with dune stabilisation work extendingnorthward to the Muriwai Stream mouth. In the late 1970's Rodney County Councilwas granted a licence to erect the Muriwai Fire Depot on the Domain, and a landing .pad was installed near the surf club for use by the rescue helicopter.

As the development of Muriwai Beach Domain proceeded under ARA management inthe early 1970's, several important resource management issues arose at Muriwai. Thefirst concerned the management of the renowned toheroa resource, and the secondconcerned the operation of the Maori Bay Quarry. The toheroa population had beenmonitored at Muriwai Beach by the Marine Development from 1927, and a daily limiton toheroa take had been set at 50 per person over a 10 month season. TheDepartment noted a decline in toheroa numbers on Muriwai Beach throughout the1930's, although numbers increased during the war years. In the 1950's a daily limit of20 toheroa per person was imposed over a two month season . Despite the impositionof these regulations, enforcement remained a problem, and toheroa populationscontinued to decline over the next two decades. In 1969 the commercial exploitationof toheroa was banned, and in 1976 the Muriwai toheroa beds were closed to allharvesting. Numbers have not increased since that time.

77

.••It had originally been envisaged that the Maori Bay quarry, gifted by Mr N Spencer to|fc. the WCC in 1952, would cease operations in the early 1960's. The County had

;however continued to operate it until 1971, at which time it began extendingJK southward on to the Domain. The continued operation of the quarry and its ongoing

impact on Maori Bay was objected to by several local residents who formed the Maori:Bay Preservation Society in 1971 and lobbied for the closure of the quarry. TheSociety publicised the situation and received support from the Auckland University

•Field Club, the Auckland University Geology Department and the Geological Societyof New Zealand. As a result of their combined efforts the quarry was closed in 1975

, and the remaining 16.8 million year old geological features of Maori Bay were•' preserved. The quarrying operations had however left rubble to a depth often metres