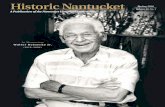

Historic Nantucket Spring 2012

-

Upload

novation-media -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Historic Nantucket Spring 2012

A Publication of the Nantucket Historical Association

Spring 2012

Volume 62, No. 2Historic Nantucket

MELVI L L EISSuE

The

The

Unemployable Herman Melville

“Nothing else to do”but Sign on a Whaleship

very like a

WHALE

Free speech and

Bike Paths

Editions of Moby-Dick

“Mystery Man” Identity Revealed

&

Nantucket’s Morris Ernst

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:43 AM Page 1

Board of Trustees

Janet L. Sherlund, PRESIDENT

Kenneth L. Beaugrand, VICE PRESIDENT

Jason A. Tilroe, VICE PRESIDENT

Thomas J. Anathan, TREASURER

William R. Congdon, CLERK

Josette Blackmore

William J. Boardman

Constance Cigarran

W. Michael Cozort

Franci N. Crane

Denis H. Gazaille

Nancy A. Geschke

Whitney A. Gifford

Georgia Gosnell, TRUSTEE EMERITA

Kathryn L. Ketelsen,FRIENDS OF THE NHA REPRESENTATIVE

William E. Little Jr.

Hampton S. Lynch Jr.

Mary D. Malavase

Sarah B. Newton

Anne S. Obrecht

Christopher C. Quick

Laura C. Reynolds

David Ross,FRIENDS OF THE NHA REPRESENTATIVE

L. Dennis Shapiro

Nancy M. Soderberg

EX OFFICIO

William J. TramposchEXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Benjamin SimonsEDITOR

Elizabeth OldhamCOPY EDITOR

Eileen Powers/Javatime Design DESIGN AND ART DIRECTION

NANTUCKETHISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

2 | Historic Nantucket

Winter 2012 | Vol. 62, No. 2

Historic NantucketA Publication of the Nantucket Historical Association

Historic Nantucketwelcomes articles on any aspect of Nantucket history. Original research; firsthand accounts; reminiscences of island experiences; historic logs, letters, and photographs are examples of materials of interest to our readers.

©2012 by the Nantucket Historical Association

Historic Nantucket (ISSN 0439-2248) is published by the Nantucket Historical Association, 15 Broad Street, Nantucket, Massachusetts. Periodical postage paid at Nantucket, MA, and additional entry offices.POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Historic Nantucket, P.O. Box 1016, Nantucket, MA 02554–1016; (508) 228–1894; fax: (508) 228–5618, [email protected] information log on to www.nha.org

Printed in the USA on recycled paper, using vegetable-based inks.

Very Like a Whale”: Editions ofMoby–DickFrom the first English and American

editions to the illustrated versions

MARY K. BERCAW EDWARDS

11

The Unemployable Herman Melville:Nothing else to do”

but Sign on a Whaleship

HERSHEL PARKER

4

Free Speech and Bike Paths:Nantucket’s Morris ErnstCivil rights and literary lawyer

advocates on Nantucket

KENNETH ROMAN

20

Literature and LifeNATHANIEL PHILBRICK

Mystery Man” Identity RevealedROBERT HELLMAN

NHA News Notes

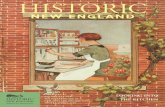

ON THE COVER: “Ahab is Ahab, man,” ink on Bristol board illustrationby Matt Kish, 2011, for p. 539 of Moby-Dick in Pictures: OneDrawing for Every Page (Tin House, 2011). COURTESY OF MATT KISH

3

21

22

“

“

“

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:43 AM Page 2

Spring 2012 | 3

efore twenty-one-year-old Herman

Melville shipped aboard the New Bedford

whaleship Acushnet on 3 January 1841, his

run of luck had run dry. He had found occasional

employment as a teacher, a clerk, a “young attorney,”

and a farmhand. He had lit out for what was then the

western frontier of Illinois, but had found nothing. He’d

even used his family’s political connections to land a job

on the Erie Canal, but had again been rebuffed. He was

truly “the unemployable Herman Melville.”

What was left for a young American, even one of

middle-class upbringing with a solid education, to do

with his life in 1841? Melville turned to that “last resort”

of desperados and down-and-outs: signing aboard a

whaling voyage. In an economy with “10 candidates for

every vacancy,” the shrewd owners and factors of

whaleships knew their way around the bottom of the

labor pool: several years of labor for little pay, or in some

cases, indebtedness.

It would have been hard in 1840 and 1841 to look

ahead, as Ishmael does in chapter 33 of Moby-Dick, to

“what shall be grand,” in the life of young Herman

Melville. Melville, sadly, remained largely

“unemployable” for much of his life, even long after he

had penned his masterpiece. His life stands as a tragic

reminder that sometimes worldly success and literature

are deeply alien to each other, even though great

literature may be born from that incompatibility.

In his brilliant two-volume biography of Melville,

Hershel Parker presented groundbreaking detail of just

what Melville was up to before he went to sea. In this

issue of Historic Nantucket, Parker presents even more

recent discoveries of the circuitous and frustrating path

NATHANIEL PHILBRICK

Literature and Life

B

NATHANIEL PHILBRICKHistorian and NHA Research Fellow

Philbrick will speak at the Annual Meeting of the Nantucket HistoricalAssociation on July 6, 2012, on the topic of his most recent book,Why Read Moby-Dick? (Viking, 2011).

that led Melville to New Bedford. In the process, Parker

shares reflections on his own journey as a biographer

sifting through the vast fields of discovery.

This issue also features Mary K. Bercaw-Edwards’s

article that provides an

overview of important

editions of Moby-Dick—

from the first English and

American editions up

through the Lakeside

Press edition, with

Rockwell Kent’s

illustrations, and the

Arion Press version

featuring engravings by

Barry Moser. Julie

Stackpole describes in a

sidebar her artful casing

of the Lakeside edition.

And, in a nod to a more

recent luminary, Ken

Roman presents the

Nantucket story of literary

and civil rights attorney

Morris Ernst.

Moby-Dick illustrated by RockwellKent, Lakeside Press Edition, Volume I,Chapter XLI, p. 273. COURTESY OF PLATTSBURGH STATE ART MUSEUM

PHOTO: MELISSA

PHILBRICK

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:43 AM Page 3

4 | Historic Nantucket

After All this time, we are still learning a little more about

herman melville’s decision to sign on a whaleship rather than to be

“pent up in lath and plaster—tied to counters, nailed to benches, clinched

to desks,” as ishmael says in the first chapter of Moby-Dick, “loomings.”

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:43 AM Page 4

Spring 2012 | 5

When Melville was twelve he had been put to work as a clerk in an

Albany bank, and then two years later, in 1834, was taken out to

clerk in his brother Gansevoort’s fur store there. Gansevoort lost

the store in April 1837 at the start of the Panic, which stretched

into a five-year depression. That summer, Herman ran the Melvill

[Original spelling of the name.—Ed.] farm south of Pittsfield,

presumably without pay, after his Uncle Thomas left for Galena,

Illinois; then in the fall he taught in a country school in the

Berkshires, nearby. After the term ended early in 1838 he may

have held jobs that we do not know about.

We have no idea where Melville had been in a long stretch of

time before 7 November 1838, when he arrived at the Melvilles’

new home, a cheap rented house in Lansingburgh, across the

Hudson from Albany and a little north. There at the Lansingburgh

Academy he took courses in surveying and engineering with the

hope of getting a job on the Erie Canal (though the long-term

benefits were from his literary papers and declamations, as

scholar Dennis Marnon is finding). In April 1839 his uncle, Peter

Gansevoort, recommended him to a Canal official in

unenthusiastic terms: “He . . . submits his application, without

any pretension & solicits any situation, however humble it may

be” (Jay Leyda, The Melville Log [New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1951],

p. 83). No position, “however humble,” was forthcoming.

On 23 May, Melville’s mother, Maria Gansevoort Melville, wrote

to Peter that “Herman has gone out for a few days on foot to see

what he can find to do” (Log, p. 85), and the next day Gansevoort,

who had been at home in Lansingburgh sick for several months,

reported that Herman had “returned from his expedition, without

success” (Log, p. 85). Leaving his mother frantic about unpaid

bills, Gansevoort returned to New York, taking with him his

brother Allan, the next younger after Herman, who had just

quarreled with his employer, Uncle Peter, and left his law office.

Gansevoort promptly wrote his mother that Herman should

come down and sign on a “Vessel.” (Allan soon returned to work

in a different Albany law office.)

In the first volume of my biography, I began chapter 8 this way:

“On 31 May 1839 Gansevoort summoned Herman from

Lansingburgh down to Manhattan, sure that he could get him on

some sort of vessel, whaler or merchant” (Hershel Parker,

Herman Melville: A Biography, 1819–1851 [Baltimore: The Johns

Hopkins Press, 1996, p. 143]). That letter is known only from the

reply Maria Melville wrote on 1 June for Herman to carry down to

New York. On blank spaces of the letter, as William H. Gilman first

pointed out in Melville’s Early Life and “Redburn” (New York: New

York University Press, 1951, p. 128), Gansevoort plotted out the

distances between New York and two Long Island whaling

ports—Sag Harbor 109 miles away by the “lower road” and River

Head 81 miles away by the “middle road” (p. 332). Gilman said

before then, perhaps as many as ishmael, who in Ch. 104 of Moby-Dick facetiously presents his credentials as

a geologist by listing outdoor or at least subterranean jobs: “. . . in my miscellaneous time i have been a

stone-mason, and also a great digger of ditches, canals and wells, wine-vaults, cellars, and cisterns of all sorts.”

Melville haD helD Many jobs . . .

Left: View of the Erie Canal, watercolor on paper by John WilliamHill (1812–79), 1830–32. COURTESY OF THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

Opposite: ”Melville,” hand-colored etching by Jack Coughlin (b. 1932), 1993. COLLECTION OF THE EDITOR

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:43 AM Page 5

6 | Historic Nantucket

The uneMployable herMan Melville

Herman Melville. There is no reason to think that Herman did not

share his friend’s “very strong desire” to try his fortune in the

Western territories. They would make their fortunes together.

In 1840, Fly’s hopes for trying his fortune in the “Western

territories” were dashed very rapidly, and that fall he took the bar

exam in New York, as I mention later. Two and a half years later, on

25 January 1843, Fly wrote to Peter Gansevoort (Log, pp. 161–62):

“In the Summer of 1840, I left you—whether wisely or not, time will

determine—to act alone & for myself. Since that time I have had to

struggle with many difficulties, incident to the life of a young

attorney during the first few years in this City,—have been in

trouble & in want, and am now just supporting myself by my

profession—& nothing more.” In 1843, he wanted Peter’s help in

gaining the appointment as “commissioner of Deeds” for New York

City. Ironically and a little contemptuously, Peter declared that the

request was beyond his power to fulfill (Log, p. 162): “Well, Fly, this

is very pretty—mental perception—a real touch of abstract

mathematics—but if you will doff your gown & slippers & step into

the world of the metropolis—you will find 10 candidates for every

vacancy who all booted & spurred with Petitions Letters &c have

actively anticipated the fees of many months in a circuitous

Journey to the Capitol & there have been encouraged by nothing

more than a mere shake, of the Governors hand.”

Herman’s hopes to rise in the West with the help of his uncle,

Major Melvill, also were dashed. Stanton Garner’s “The Picaresque

Career of Thomas Melvill, Junior, Part II” (Melville Society Extracts,

No. 62 [May 1985]) is the most detailed investigation of Melville’s

uncle’s life in Galena. Sure that the Galena Melvills were

prosperous and active in the town, Garner was a little perplexed

that Thomas Melvill was not more involved in the raucous political

campaign: “This summer a presidential campaign was in progress,

though the part the major played in it, if any, was not prominent”

(p. 6). The reason for Major Melvill’s not helping Herman find a job

in Galena was not apparent to Garner.

Garner had found in a historical journal an account of the

that from the “figures that Gansevoort jotted down” it was “possible

to conclude that Herman had some intention of going to sea as a

whaleman” (p. 128). If so, he continued, Herman “was reasoned

out of his folly.” Unlike Gilman, I take it that the brothers seriously

considered Herman’s striking out across Long Island to a whaling

port, perhaps “on foot” again. It seems to me likely that the

brothers rationally considered the options, a whaleship or a

merchant vessel. I speculated this way (p. 144): “Herman and

Gansevoort weighed the possibilities with perturbation—the time,

expense, and uncertainty of getting to the whaling ports influenced

their decision to settle on a merchant ship sailing from Manhattan.

Maybe in a few months’ time (rather than the years a whaling

voyage might last) more jobs around Albany would be open.”

Herman signed on a merchant ship for a voyage to Liverpool.

In “The Pacific,” chapter 111 of Moby-Dick, Ishmael declares

“. . . the long supplication of my youth was answered,” on greeting

that ocean. Perhaps Herman in the 1830s made such a

supplication many a time, perhaps not, but after his return from

Liverpool in 1839 his efforts to support himself (while not

contributing to the support of his mothers, sister, and youngest

brother) continued to be miserably unsuccessful. He found a

teaching job at the Greenbush & Schodack Academy but was not

able to pay his board because the school was not paying his salary.

On 3 April 1840, Gansevoort summed things up as they then stood:

“Herman is becoming more & more indebted for his board, &

should he in the end be disappointed in receiving the sum that is

due him for his winter services, will be so much the more difficult

to pay” (Log, pp. 103–4). The Academy failed, without paying

Herman all that he was owed, and he taught for a while at a school

in Brunswick, northeast of Troy, but was not paid the six dollars he

had earned.

Despite these disappointments, Herman did not yield to any

longing to see the Pacific. He and a close friend, James M. (Eli) Fly,

who for years had been Peter Gansevoort’s clerk, decided to follow

his Uncle Thomas in making their careers in the American West, on

the Mississippi. Why not? Wasn’t his uncle now a prominent citizen

of the flourishing lead-mining town of Galena, Illinois? Of course

Herman would not have written his uncle about his intention to visit

him: the fun would be in surprising his uncle, aunt, and cousins.

We do not have a letter from Herman declaring that he was

determined to rise in the West with the help of his uncle, Major

Melvill. Happily, we do have explicit statements from his friend Fly,

the letter he wrote his employer, Peter Gansevoort, on 2 June 1840

(Log, p. 105):

I have had, for some weeks past a very strong desire to try my fortune

in the Western territories of this country.—I believe that a young man,

with temperance & perseverance joined with my knowledge of the

legal profession, will succeed much better in a new state, than in this

. . . . I am aware that I am taking a very singular step, and it may be a

fatal one,—but I am prepared for the worst.

Around 4 June, Fly left Albany “for the West,” accompanied by

One-room schoolhouse in Brunswick, New York (northeast of Troy), whereMelville taught in 1840. Pen drawing, circa 1975, by Douglas Bucher.COURTESY OF THE BRUNSWICK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:43 AM Page 6

major’s being caught stealing from the till in his employer’s store. A

daughter of Hezekiah Gear, the store owner, had put on record the

appalling story replete with this quintessentially melodramatic

dialogue (p. 8):

Thomas Melvill Jr: “Oh, Captain, spare me.”

Hezekiah Gear: “You must make some restitution.”

Thomas Melvill Jr: “I can’t, for the money is spent. It’s been going on

for years.”

Hezekiah Gear: “There is nothing to do. I could send you to prison

for life, but that would not bring back the money. [He pauses for a

moment then continues.] Major, for the sake of your good family

and for the sake of your gray hair, I’ll not punish you, but I never

want to lay eyes on you again.”

Garner dated the incident to the summer of 1841. Since Herman hadsailed for the Pacific in January 1841, Garner did not see the incident ashaving any significance for whatever occurred when Melville and hisfriend arrived in 1840 to make their fortunes in the West.

After I took over The New Melville Log in 1987, as Jay Leyda was

dying, I needed to date Garner’s 1985 discovery so I could

confidently place it in the Log. I inched through microfilms of

unpublished letters in the Shaw Papers I had first handled in 1962.

On 26 June 1840 Melvill wrote Shaw:

Here, as elsewhere, the effects of the policy & measures, of the past &

present administrations, are most severely felt—Not the less so, for

being more tardy—

Few houses, doing business in 1834.5.6. & 7. have been able to

withstand it. The one, with which I was, is among the Number. In

March last, I found it necessary, and for the interest of both parties,

to retire—& with some (to me,) considerable loss, or its equivalent,

delay—

You may have observed by the Papers—that I have made an agency

establishment—which in the present state of things, seemed to be

the only kind of business to which, I could turn my attention. . . .

. . . such is the situation of this place at present, that money is almost

unobtainable in any manner, or at any rate—It may be said, not to

exist. . . .

The political excitement here, is great—In fact, it is almost the only

business of the present times—There will be a large majority for

Harrison in Illinois—(MHS-S)

so in March 1840, Melville “found it necessary” to

“retire” from the business where he had worked—a masterful

transformation of the scene which Gear’s daughter recounted

decades later. On 2 July, Melvill Jr. wrote Shaw again at the foot of

the original of his letter of 26 June, the copy of which he had mailed

by mistake. In this new passage he did not mention his nephew

Herman, so presumably Herman and Fly had not yet arrived,

although they probably did within a very few days. Melvill’s letters

in the Shaw Papers from 1840 until his death in 1846 show that he

never had a job in a store in Galena again, so this evidence

conclusively ties the thievery to early 1840, to March, if Melvill

reported the month accurately.

Winter 2012 | 7

This discovery put a different light on Melville’s arriving in

Galena for a surprise visit, hoping to rise in the West with the help

of his uncle, Major Melvill. If his uncle had been successful in

Galena and the town had been flourishing, Herman might indeed

have stayed there indefinitely. On Herman’s arrival, the major was

not only jobless but disgraced, unable to help even himself and his

sons, and certainly not a mere nephew. It is possible that no one in

the family confessed to Herman that the old man had been caught

stealing. Whatever he learned, Melville was disappointed, although

we do not know just what ingredients went into the bitter mix.

Herman found no reason to linger very long in Galena, contrary to

what had been thought. In his 1951 Herman Melville: A Biography

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951), pp. 36–37, Leon

Howard had decided that Herman “was to stay with his uncle long

enough to see the silks of the prairie corn turn brown in the

autumn and to receive the impressions later incorporated in his

poem, ‘Trophies of Piece,’ but there was little for him to do. . . . At

the beginning of autumn there was nothing for Melville and his

companion to do but turn homeward with the hope of finding

some sort of employment in New York.” No, much sooner than

Howard had thought, Melville returned home, with consequences

for literature—his signing on a whaling voyage.

Good researchers sooner or later experience the high

excitement of discovering unknown episodes of their subjects’

lives. That excitement does not

necessarily make the

biographers the best

narrators of what they

discover, although it

sometimes assures

that they will make a

more comprehensive

and sensitive narrator

than anyone else

could do, at least in

the first telling. Stanton

Garner told a good story

about Uncle Thomas’s

being caught stealing in the

store in Galena while Melville

was in the Pacific. I told a

truer story, and one directly

involving Melville, since I

had discovered that the theft

and the firing had occurred

shortly before Melville showed up unannounced in Galena. When I

wrote the episode I was in a wrought-up state because for many

months I alone had known and sympathized with what I foresaw

would beMelville’s disappointment at finding his uncle jobless and

unable to help him. That sounds peculiar, but you can know

something previously unknown is going to happen in your

Portrait of Herman Melville by AsaTwitchell (1820–1904), oil on canvas,circa 1846/7. COURTESY OF THE BERKSHIRE ATHENAEUM

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:43 AM Page 7

8 | Historic Nantucket

The uneMployable herMan Melville

Portrait of HermanMelville, by JosephEaton, 1870. SC770, ORIGINAL PAINTING AT

HOUGHTON LIBRARY

narrative but not focus on it acutely until you actually start writing

it. Melville understood this when in chapter 33 of Moby-Dick he

has Ishmael look ahead to “what shall be grand” in Ahab, in the

narrative.

The first teller of a new story gets the privilege of choosing, but

to a great degree the manner of telling should be controlled by the

amount and the nature of the documentary evidence available. I

see now that I chose to tell this story about Galena pretty baldly in

my biography despite my strong emotions, perhaps because I was

leery of over-coloring the story with those emotions, and also

because I simply did not know how much Herman had learned

about the new shame to the family. He learned that hard times had

hit Galena, but what, if anything, he learned about his uncle’s

disgrace is still not known. There is no hint of the Galena scandal in

the memoir Melville wrote of his uncle for the History of Pittsfield,

Massachusetts, but neither is there any hint of his uncle’s staying in

Lenox jail in earlier decades as a debtor.

On reading my new revelation about his own discovery, Garner

in his review of my first volume in Melville Society Extracts,No. 112

(March 1998), p. 28, behaved just the way a fine scholar should

behave:

As an editor of the Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville’s

works, Parker has long been close to what is, collaterally, a large

biographical project. The experience also seems to have schooled him

in the techniques of discovering material where it lies hidden and

developed in him a sense of what may remain to be discovered if only

one persists. Nor has Parker been reticent in obtaining the assistance

of others, thus extending his reach beyond scholarly arm’s length.

The result is stunning. What in the past has been no more than a hint,

a reference, or a brief note in Howard becomes an illuminating

account of an incident in Melville’s life, and what was an error (in

this case, a date in my own report on Uncle Thomas’s disgrace in

Galena, Illinois), is corrected, uncloaking a new insight into Melville’s

early search for a career and thus into his motive for voyaging aboard

the Acushnet. If this is a large volume, it is also one in which questions

are answered, misapprehensions set aright, and whole briskets of

knowledge added to our hoarded heaps.

This was characteristically magnanimous, and surely Garner

was recalling the cooperation behind a footnote on p. 490 of his

The Civil War World of Herman Melville (Lawrence: University

Press of Kansas, 1993). Garner said this about the letter in which

John Hoadley described how he, Melville, and others participated

in Pittsfield’s celebration of the news from Gettysburg and

Vicksburg: “I am indebted to the late Jay Leyda and to Hershel

Parker for their aid in reading this almost illegible letter.” It took all

three of us, but we got it—got it in time for Garner’s book and in

plenty of time for the second volume of my biography and

(ultimately) The New Melville Log.Garner died in November 2011

without knowing that I had made a reference to his “largeness of

spirit in envisioning Melville” in my Melville Biography: An Inside

Narrative (forthcoming from Northwestern University Press in

2012).

in The Trove of Melliville papersmainly

acquired by the New York Public Library in 1983 (NYPL

Gansevoort-Lansing Additions), a portion of the papers of

Melville’s sister Augusta, was a very damaged letter where the ink

was so pale that even in the late 1980s, with only middle-aged eyes,

I had to gird myself up to struggle with it under my lighted

magnifier. In it Elizabeth Gansevoort, a cousin living in Bath, in

western New York, on 2 September 1840, pleaded with Augusta to

visit her: “you have a Brother that I know has nothing else to do,

and would be willing to come with you.” (Elizabeth’s underlining;

the letter is quoted in the first volume of my biography, p. 179.)

Once I deciphered the letter, I did a survey of the whereabouts of

the four Melville brothers and decided, Tom being far too young

and Allan and Gansevoort being at work in Albany and New York,

respectively, that the unoccupied brother had to be Herman, home

already from Galena, and home for some time, unlike what

Howard had thought.

So Herman was at home with his mother in early September,

and had been home long enough for Augusta to have written her

cousin about his return from the West and for Elizabeth to have

replied with the letter of 2 September. We know that the cousins did

not usually answer letters by return mail, even if they did not have

to wait for someone to carry the letter to the recipient: Herman

could have returned as early as July. He was unlucky, not lazy, and

would have been looking for work, I thought, whatever his cousin

in Bath thought. I am wary about taking anything in Melville’s

fiction as autobiography, but I have learned not to blind myself

with skepticism. While working on the first volume of my

biography I paid attention to the passage in “Loomings,” where

Ishmael explains that when he goes to sea as a simple sailor the

officers order him about in a way that is “unpleasant enough.” He

goes on: “It touches one’s sense of honor, particularly if you come

of an old established family in the land,

the Van Rensselaers, or Randolphs,

or Hardicanutes. And more than

all, if just previous to putting your

hand into the tar-pot, you have

been lording it as a country

schoolmaster, making the tallest

boys stand in awe of you. The

transition is a keen one, I assure

you, from a schoolmaster to a

sailor. . . .” Melville’s mother, of

course, was a Van Rensselaer, and

his sister Augusta was so regular

a visitor to the Manor House

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 8

Spring 2012 | 9

that she had her own room there. Knowing from Elizabeth

Gansevoort’s letter that Melville had returned from Galena much

earlier than we had thought, I decided that in late 1840 Melville,

like Ishmael, might have gone more or less directly from

schoolmaster to whaleman: perhaps “just previous” meant “just

previous.” In the first volume I ventured a guess (Parker 1:179) “Late

that summer, for all we know, he may very well have looked for

another job teaching school around Lansingburgh.”

A sidelight on method: how was I to avoid writing parts of my

biography from Melville’s more or less autobiographical books? I

resolved on extreme measures. I set myself the goal of creating a

full first draft of the part of 1842 which Melville described in Typee

and Omoo by working solely from other surviving documents

(some authentic, some plainly skewed), never quoting those two

books. That salutary exercise helped me break the 1920s reliance

on Melville’s books as straight biography. Breaking that reliance, I

emphasize, requires heroic discipline, and disciplined judgment of

another sort is required in acknowledging that Typee and others of

Melville’s books are in fact, in passages, something like straight

autobiography. I guessed right about Melville’s teaching school

when he got home from Galena just because I allowed for the

possibility that something in “Loomings” could be straight (or

something very close to straight) autobiographical. You have to be

imaginative, alert, subtle, and supplied with a kit of phrases like “as

far as we know,” and “it just might be,” or my favorite, “for all we

know.” Even if reviewers mock you for your “perhapses,” you can

take satisfaction in being honest.

in 1999, a new DocuMenT emerged from a liquor box in

Paul Metcalf’s house. These were papers loaned to Metcalf’s

mother by her second cousin, Agnes Morewood, and now (with

one exception) belatedly rejoined with the bulk of the Morewood

documents in the Berkshire Athenaeum. The oldest Melville

brother, Gansevoort, had written to Allan on 6 October 1840: “I am

very glad that Herman has taken a school so near home.” Hurrah!

From the documents available to anyone at the Massachusetts

Historical Society I had discovered a story of the poignantly

disappointing ending to Herman’s hopeful trip to Illinois (however

much or little he learned about his uncle’s disgrace). What I

cautiously proposed about Herman’s teaching school was only an

educated guess, phrased as such (“for all we know”), one happily

verified three years after the volume was published.

“Only an educated guess,” I just admitted. That warrants a

comment. Leon Howard, whom I loved like an uncle, and a more

helpful one than Herman’s blood uncles, was a shrewd, responsible

scholar, who had been browbeaten, as he said, into writing his

biography from Leyda’s yet-unpublished Log.He had not spent

years in the archives himself. Howard was not a years-in-the-

archives man. He was the sort of scholar who would chat up

the director of a library, look over a famous manuscript with

him (the director of course was male in those years), and

come to reasonable conclusions about it that more

pedestrian workers might plod away for a long time without

perceiving. That is what happened at Harvard with the

manuscript of Billy Budd. In his biography, Howard made many

educated guesses about Melville, which by my tally were without

exception wrong. The problem was that given two or more choices

the would-be rational Howard always pushed Melville into taking

the sensible one. Informed, or I might say beaten down by a much

greater mass of evidence, I became predisposed to accept irregular,

irrational behavior from Melville. After a time I was never surprised

when he ran headlong away from the course that Maria

Gansevoort Melville and I both thought represented his own best

interests. On the matter of what Melville did after returning from

October 6, 1840, letter from Gansevoort Melville to his brother Allan Melville confirming Herman’s teaching school.COURTESY OF BERKSHIRE ATHENEUM

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 9

10 | Historic Nantucket

The uneMployable herMan Melville

Galena, I merely considered what he would naturally have done

once he was back in Lansingburgh. In instances where evidence

has later emerged, my record with educated guesses is, I think,

perfect, so far, and I would not be surprised to learn that other

biographers who have toiled in the archives would bet a few dollars

on their own best educated guesses. We are far from infallible, but

when we are forced to guess, we may bring an imposing array of

evidence to the topic, even if our reasons have to be dragged up

from a murky level of consciousness and even if, as in this instance,

they involve taking some of the details in a piece of fiction like

“Loomings” as possibly autobiographical.

While Herman was teaching school near home, Fly set himself to

study for the bar. On 6 October, Gansevoort wrote Allan, who was

clerking in Albany, not with Uncle Peter, saying he would be glad if

Fly would write him “a detailed account of the examination”

(Berkshire Athenaeum, Metcalf Donation). (On 4 November 1840,

Scott Norsworthy recently informed me, the New York American

reported that Fly had been admitted to the New York bar at the

October term.) Herman’s schoolteaching near Lansingburgh did not

last long, for on 26 November Gansevoort wrote Allan (Log, 110):

Herman is still here—He has been & is a source of great anxiety to

me—He has not obtd a situation—Fly is still on the lookout—He has

so far been entirely unsuccessful—You need not mention this to [John

J.] Hill, as his little mind would gloat over Fly’s disappointment—

They are both in good health & tolerable spirits—& are living at a

cheap rate of $2.50 per week, exclusive of dinner—They dine with me

every day but Sunday at Sweeny’s & are blessed with good appetites—

as my exchequer can vouch—Herman has had his hair sheared &

whiskers shaved & looks more like a Christian than usual. . . .

The brothers soon concluded that there was no point in looking

longer for work in New York City. On December 21, Maria Melville

reported to Allan that “Hermans destination” was being decided:

“The particulars you will hear when we see you” (Berkshire

Athenaeum). She continued: “Fly has a situation with a Mr

Edwards, where he has incessant writing from morning to Eveg.”

Leaving Fly to Bartleby-like industry, Herman had decided upon a

desperate grand physical adventure.

In this glance at Melville’s early job-hunting, I skip over evidence

for Melville and Fly’s later relationship, though we know that after his

return from the Pacific Melville was able to befriend Fly, who over a

period of several years was slowly dying. I skip all the way to a 4

March 1854 letter Maria Gansevoort Melville wrote to Augusta from

Longwood, near Boston (NYPL Gansevoort-Lansing Additions).

Here the judge is Melville’s father-in-law, Lemuel Shaw, and Lizzie is

Herman’s wife, and Mrs. Shaw is the judge’s second wife:

The next morning Miss Titmarsh called . . . Lizzie, the Judge & I were

alone in the room, & Mrs Shaw very much engaged. So we had all her

conversation. The subject happened to be about Hingham. In one of

the pauses I enquired if she knew Mr Fly. Oh yes the most interesting

man she had ever seen. She did not wonder, that notwithstanding his

bad health Miss Hinkley had married him. I then enquired about his

death. Mr Fly had left a message to Herman said Mrs Titmarsh,

looking at the Judge & something about a Cloake, Sir, I believe which

Mr Melville had given him? A post mortem examination had taken

place, one lung was entirely gone, of the other but half remained. The

widow was inconsolable.

The deathbed scene is Dickensian, we now think, and of course

Thackeray actually used the pen name “Michael Angeleo

Titmarsh.” Census records show that this real Mary T. Tidmarsh

[sic] lived in Hingham all thorough the 1850s. Perhaps this

concerned a most mundane fact, but the passage I quote was what

you could fairly describe as a deathbed message. Who would not

be intrigued by “something about a Cloake” which Herman had

given him? For several years I was haunted by the scene,

inexplicably moved by Fly’s dying message to Herman Melville.

Then, in the liquor box that Paul Metcalf opened in 1999 was a

letter (now part of the Berkshire Athenaeum Metcalf Donation)

from Gansevoort to Allan on 14 January 1841, just after Herman

had sailed on the Acushnet:

Fly called to see me on Sunday last and dined at Bradford’s. He

manages to scrape along on the slender salary which he receives from

Mr Edwards. He is very attentive to his duties, & steady & regular in his

habits. In the end he will doubtless succeed. Herman sent to Fly as a

parting souvenir his vest & pantaloons. The coat was exchanged at New

Bedford for duck shirts &c. At sea[,] shore toggery is of no use to a sailor.

Is it possible that Fly, knowing he was dying, remembered that

in 1841, if not longer, he had worn the vest and pantaloons of an

impoverished young whaleman who would become one of the

greatest American writers? Did he glory, as he died, in the memory

of that very tangible intimacy with a friend of high genius? It’s

possible. Dickens, with what Melville thought was his

characteristic over-plotting, would have made this so. I would not

put it in a biography as fact, but I like the story I imagine.

Something about a vest & pantaloons. . . . Something dating back,

perhaps, to the days when Herman Melville was unemployable.

Melville, of course, was unemployable in a government office in

1847, 1853, 1857, and 1861, as Harrison Hayford and Merrell Davis

showed in “Herman Melville as Office-Seeker,” Modern Language

Quarterly, 10.2 (June 1949), 168–83 and 10.3 (September 1949),

377–88. In 1860, Melville was unemployed, once he had given his

last lecture, and he remained unemployed till near the end of 1866,

when he gained his appointment in the New York Custom House.

For several years now, thanks to databases of newspapers, Scott

Norsworthy, Dennis Marnon, and George Monteiro have pointed

out that Melville’s nineteen years of uninterrupted employment

were achieved only through the intervention of an angel in the

Custom House, a man with a Lansingburgh connection,

Chester A. Arthur._____________________________________________________________

Hershel Parker talked about “The Metaphysics of Indian-hating” at the MelvilleSociety meeting in Chicago in 1960. He is the author of the forthcoming MelvilleBiography: An Inside Narrative (available for pre-order on Amazon), and of theclassic two-volume Herman Melville: A Biography (1996 and 2002) as well as thelongtime editor of The New Melville Log.He blogs athttp://fragmentsfromawritingdesk.blogspot.com.

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 10

Spring 2012 | 11

Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick originally appeared in 1851 to

little fanfare and even less renown. With a drab, darkish, dreary cover, the first

American edition look s undistinguished, even shabby. The first English edition

is much handsomer; each of its three volumes has a gold whale on its spine.

Unfortunately, the whales are right whales, not sperm whales. Melville heaped

contempt upon right whales, who swam so “sluggishly” that they appeared

“lifeless masses of rock,” which could be mistaken for “bare, blackened

elevations of the soil”; in contrast, he called sperm whales—such as Moby Dick—

“the most majestic in aspect” of all whales.

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 11

12 | Historic Nantucket

Above: “Moby Dick was now again steadily swimming forward,” acrylic on watercolor paper illustration by Matt Kish, 2011,for p. 546 of Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page (Tin House, 2011). COURTESY OF MATT KISH

Previous page and top right:Woodcut illustrations of sperm whale and “View of Nantucket Harbor” by Barry Moser (b. 1940)for 1979 Arion Press edition of Moby-Dick. COURTESY OF ANDREW HOYEM.

“Very Like a WhaLe’: EDiTions of Moby-Dick

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 12

Spring 2012 | 13

The first American edition was set directly in type from

Melville’s manuscript, but it was not published first. In order to secure

copyright protection, a book by a non-British author had to have its initial

publication in England. The proof sheets were therefore sent to Richard

Bentley, Melville’s London publisher, where they were edited and sections

considered too blasphemous or bawdy cut. Bentley released the book

under its original title The Whaleon October 18, 1851. Harper & Brothers

published the book as Moby-Dick in New York on November 14, 1851.

The Bentley edition was only 500 copies. Even though Bentley

inserted a new title page into some copies in 1853, those copies were still

composed of the original sheets. The Harper edition was much bigger—

2,915 copies—with new printings of roughly 250 copies in 1855, 1863,

and 1871. Part of the reason for the new printings was the Harper fire in

1853. These were new printings, not new editions. In the forty years

between Moby-Dick’s publication in 1851 and Melville’s death in 1891,

only one British and one American edition were published.

Even while writing Moby-DickMelville experienced deep frustration.

He wrote to Nathaniel Hawthorne, “What I feel most moved to write,

that is banned,—it will not pay. Yet, altogether, write the other way I

cannot. So the product is a final hash, and all my books are botches.”

Such anguish is still painful to read 160 years later. But there is one

consolation: Melville dedicated Moby-Dick to Hawthorne, and upon

Hawthorne’s receipt of the book, he sent Melville a “joy-giving and

exultation-breeding letter.” Melville added, in his response to

Hawthorne’s letter, “A sense of unspeakable security is in me this

moment, on account of your having understood the book.”

And so the book was published. The review in the New Bedford,

Mass., Daily Mercury called the first American edition “a bulky, queer

looking volume, in some respects ‘very like a whale’ even in outward

appearance.” We know of one whaleman who read it: Benjamin Boodry

aboard the Arnolda in 1852. But few others did.

Melville died in 1891 with no expectations of literary fame for his

whaling book. In fact, on Melville’s death, the obituaries registered

surprise not so much that he had died as that he had still been alive:

“There died yesterday at his quiet home in this city a man who,

although he had done almost no literary work during the past sixteen

years, was once the most popular writer in the United States. . . .

Probably, if the truth were known, even his own generation has long

thought him dead.”

One year after his death, in 1892, Melville’s literary executor, Arthur

Stedman, republished Moby-Dick in what is sometimes called the

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 13

14 | Historic Nantucket

“Very Like a WhaLe’: EDiTions of Moby-Dick

“deathbed edition.” Three other editions followed: the Scribner’s

edition in 1899, with illustrations by I.W. Taber; the “Everyman’s

Library” edition in 1907; and the “World’s Classics” edition in 1920.

Then, in 1921, everything changed. That year, a Columbia

University professor, Raymond Weaver, published a biography of

Melville titled Herman Melville: Mariner and Mystic. It is poor

biography, but its importance cannot be overemphasized. Having

read the biography, readers clamored for Melville’s works. Twelve

new editions of Moby-Dick appeared in the next eight years, over

half of which were illustrated. Weaver served as editor of the

Constable edition of The Works of Herman Melville, Standard

Edition (1922–24), which remains the only complete set of

Melville’s works.

The first color illustrations appeared in the 1922 Dodd, Mead

edition. Mead Schaeffer created the first full-length portrait of

Ahab. Schaeffer’s style is realistic; one can even see the grain of the

wood on the quarterdeck and the details of Ahab’s belt-buckle.

But, as Elizabeth Schultz asks in Unpainted to the Last:Moby-Dick

and Twentieth-Century American Art (1995), “How does a realistic

artist depict ‘an infinity of firmest fortitude’ or ‘the nameless regal

overbearing dignity of some mighty woe’ or even the adjective

‘moody’?”—all phrases used in the initial description of Ahab

when he finally appears in chapter 28, “Ahab.” The answer is he

cannot. “[T]he Pequod’s captain,” Schultz writes, “looks like

nothing more than a common seaman, hardly the tragic, isolated

figure—romanticized or demonized—of later illustrators.”

Schaeffer’s Ahab stands in strong contrast to that drawn by the

most famous of all illustrators of Moby-Dick: Rockwell Kent. Kent’s

Ahab is brawny and powerful with a craggy face and determined

eyes gazing over the side of the Pequod. The full-length portrait of

Ahab does not appear until midway through chapter 46,

“Surmises.” It takes twenty-eight chapters for Ahab as a character

to appear, and forty-six chapters for Ahab as an illustration to

appear. As Schultz notes: “Kent intentionally postpones his

presentation of the Pequod’s captain in the full power of his

personality. Rigid in mind and body, dark-clothed and dark in his

thoughts, he stands alone.”

Kent’s three-volume Lakeside Press edition, containing 280

engravings and published in an aluminum slipcase, appeared in

1930. His are by far the most well known of all illustrations.

Although only a thousand copies of the Lakeside Press edition

existed, in 1930 Random House issued a short, squat, one-volume

copy containing 270 of the 280 illustrations that was picked up by

the Book-of-the-Month Club. In 1944, the Modern Library Giant

appeared, also containing Kent’s illustrations.

Kent’s fame, of course, does not rest on easy public access to his

illustrations, but on their tremendous power. Our vision of the

white whale is inextricably bound to Kent’s image of Moby Dick

ascending from black waters into a dark sky, sprinkled with stars,

the jet of his white spout flowing back across his back. The

bubbles of the whale’s wake seem inseparable from the stars.

Kent’s other most famous illustration of Moby Dick is a radiant

Some great books and their illustrators are indelibly linked in the minds ofalmost everyone—Alice in Wonderland and Tenniel, Treasure Island andN. C. Wyeth. For Moby-Dick, the black-and-white drawings of RockwellKent are the perfect companion pieces to Melville’s epic.Rockwell Kent was already a

well-established painter, woodengraver, and illustrator in 1926when he was asked by LakesidePress, the fine-press division ofthe Chicago publisher R. R.Donnelley & Sons, to illustrate adeluxe edition of Richard HenryDana’s Two Years before theMast, but Kent declared hispreference for Moby-Dick.Heprepared for the task bythoroughly researching whalesand whaling at the New BedfordWhaling Museum, the Museum ofNatural History in New York, andin all the literature on the subject.In addition, Kent’s Zpersonalhistory of adventures in Alaska,Newfoundland, and Tierra delFuego; then being shipwrecked ona sailboat in Greenland during the middle of the project, gave him unique insight into and sympathy with the crew of the Pequod and their creator, Melville. Donnelly was so pleasedwith the first group of drawings Kent produced that they gave him carteblanche to design the binding, slipcase, and typography as well. The finaldrawings were completed in Denmark at explorer Knud Rasmussen’shome, where he went after his Greenland escapade.

Kent’s Moby-Dick drawings have frequently been erroneouslydescribed as “engravings,” but they were all created with India ink andbrush or pen. Kent was a master wood engraver, and his drawing stylewas similar to that even before he took up engraving in 1919, andafterwards borrowed even more from it as he learned to balancedramatic areas of black and white. A fine-tipped stiff brush was hispreferred tool.

The 1930 Lakeside Press deluxe edition of a thousand copies was inthree volumes in an aluminum slipcase (hence its nickname in the booktrade “Whale-in-a-Pail”), with 280 illustrations. It has been praised inConstance Martin’s Distant Shores for its “integration of text and imagery . . . its energy and suggestive power” and “Kent’s identificationwith Melville’s story.” Donnelley also printed a smaller-sized one-volumetrade edition with fewer illustrations for Random House. So quickly hadKent’s illustrations become identified with Moby-Dick that authorMelville’s name was left off the binding!

A Special Container for theLakeside Press Moby-DickBy Julie H. B. Stackpole

India ink illustration of Ahabby Rockwell Kent (1882–1971)in Lakeside Press edition ofMoby-Dick, Volume II, p. 36.COURTESY OF PLATTSBURGH

STATE ART MUSEUM

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 14

Spring 2012 | 15

My copy of the three-volume Lakeside Press Moby-Dick descended to me frommy paternal grandfather, Hayo Hans Hinrichs, a malt and grain broker in NewYork. He was a friend, patron and “collaborator” of Rockwell Kent and had manyof his drawings, engravings, and paintings in his homes in Quogue and StatenIsland, New York, which I saw and admired as a young girl. In 1960, at age nine, I came home to Nantucket when my family joined that of my stepfather, summerresident Walter Beinecke Jr., who was a keen appreciator of Nantucket’swhaling history as well as of rare books and fine printing. It was because of hisinfluence that I eventually became a bookbinder, so I could both work with booksand live on Nantucket. When I married maritime historian and one-time curatorof the Whaling Museum, Renny Stackpole, I also received the bonus of havingAmerica’s preeminent whaling expert Edouard A. Stackpole as a father-in-law.

Our Moby-Dick did not have a slipcase when my father, Herbert Hinrichs,decided it logically belonged with me on Nantucket. For years I meant to makeone. A few years ago, when I decided to put it on the market, something finallyhad to be done to protect the valuable volumes. I thought of making a slipcasecovered in silver paper to imitate the aluminum one (boring). Instead, I seized theopportunity to be creative, and to differentiate this copy from the others withoutharming, or replacing, the original Kent bindings.

The “art box” I made is a slipcase with a front flap, so the three books areentirely enclosed. Covered in gray Niger goatskin, it has panels on the two sidesand the front with scenes taken directly from Kent’s illustrations. These arecarried out with thin onlays of different colors and textures of leather that havebeen tooled “in blind” (without gold) and embossed with linoleum cuts. Althoughthe panels copy Kent’s drawings, I interpreted them in color rather than slavishlyreproducing the black and white. There is no title, but the iconic scene of thewhite whale rising out of the water on the front flap leaves no question as towhat is in the box, I think. To tie the box to my Stackpole connections, a smalloval scrimshawed whaleship that once belonged to E.A.S. covers the area ofVelcro on the top where the flap attaches. The inside is lined with a hand-marbled paper by Chena River Marblers._________________________________________________________________

Julie H. B. Stackpole lives in Thomaston, Maine, with her husband, Renny Stackpole. Shedoes hand bookbinding and rare-book restoration as well as period-costume researchand reproduction. Her Web site is www.juliestackpole.com.

Illustrations from the hand-tooled leather slipcase byJulie Stackpole for LakesideEdition of Moby-Dick.COURTESY OF JULIE STACKPOLE

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 15

16 | Historic Nantucket

white whale soaring into heaven, trailing white water behind him,

dazzling light surrounding him: a true apotheosis.

Kent consulted with Robert Cushman Murphy, who had made a

whaling voyage on the Daisy in 1912–13 and visited the New Bedford

Whaling Museum and the 1841 whaleship Charles W. Morgan, then,

as now, berthed in New Bedford, before creating his illustrations. But

his research pales in comparison to that undergone by Barry Moser

for the 1979 Arion Press edition. Each illustration that Moser

completed had to be vetted by a group of maritime-museum

curators. For example, Moser’s first illustration of a cutting stage was

sent back because the version he had drawn did not come into use

until after Melville returned from his four years at sea in 1844.

During a visit to San Francisco in October of 1977, Moser met

Andrew Hoyem and agreed to produce a hundred engravings for the

Arion Press’s forthcoming Moby-Dick.Hoyem strictly controlled the

project. He believed that “pictorial presentation of the characters or

interpretations of events would inhibit a reader’s imagination” and

therefore Moser’s woodcuts “depict only whales (live and dead,

skeletal and blubbery), the objects, tools, and processes used in

whaling, the types of vessels from which the hunts were conducted,

the ports from which they sailed, and the seas over which they

voyaged.” Moser himself has long chafed against Hoyem’s

restrictions and talks of producing a new version of Moby-Dick in

which he will engrave Ahab, Ishmael, Queequeg, and the other

characters as he has imagined them. Nonetheless, his 1979

engravings remain deeply loved.

Arion Press produced only 265 copies (250 for sale), so they are now

extremely rare. In 1981, however, the University of California Press

issued a seventy-percent smaller version in hardback and paperback,

therefore ensuring that the general public could have access. Actor

Daniel Day Lewis and director Paul Thomas Anderson were so

impressed when they saw a copy of the Arion Press Moby-Dick that

they hired typographer Kenny Howard to set the type and print the

title sequence for “There Will Be Blood” (2007).

Not all editions are as grand, imposing, or—Hoyem’s word—

“monumental” as that of the Arion Press; some are simply fun,

quirky, or odd. As early as 1925, Grosset & Dunlap released an

edition that was “Illustrated with Scenes from the Photoplay.” The

photographs show such elusive characters as Ahab’s evil brother

Derek and loyal girlfriend Esther Harper—elusive, of course, because

they do not exist in Melville’s text. Filmed in 1925 and released in

January of 1926, this silent black-and-white film was titled The Sea

Beast,but based on Moby-Dick.A new version, a talkie, starring John

Barrymore, was released in 1930; called Moby Dick,Ahab’s beloved is

now named Faith Mapple. In both versions, we finally learn Ahab’s

last name: Ceely. Grosset & Dunlap had a later printing with

photographs from the 1930 film.

In contrast to the quirky editions were the scholarly editions. For

these, textual editors try to present a text as close as possible to what

Melville wrote. Texts are corrupted in many ways, accidentally by

printers’ sloppy compositorial work, or purposefully by editors in

order to remove anything they fear might be offensive. Textual editors

report all changes, then seek to determine whether any change is

“authorial” (done by the author) or not. For the 1952 Hendricks

House edition, Luther S. Mansfield and Howard P. Vincent report a

small number of editorial changes and “verbal changes made in the

first English edition.” Their edition is justifiably famous above all for

their extensive “Explanatory Notes,” which run for 263 pages.

The next scholarly edition after Mansfield-Vincent was Harrison

Hayford and Hershel Parker’s Norton Critical Edition of Moby-Dick

(1967, but in progress since the early 1960s and independent of the

Melville Project). For two decades the NCE, designed to make textual

history and issues accessible to students, was the standard edition of

Moby-Dick.Textually the 1967 NCE was almost identical to the 1988

Northwestern-Newberry edition, which featured a more

conventional textual apparatus and in which Hayford and Parker

were joined by a third editor, G. Thomas Tanselle. The NN text was

used in the Arion Press edition (1979) and later in the Penguin

edition (1992), with introduction by Andrew Delbanco and notes by

Tom Quirk, and the Penguin eBook (2009), with additional eNotes

and essays by Mary K. Bercaw Edwards. This is the gold standard of

texts, with an exhaustive Textual Record; the NN edition aims to

establish a text—a “critical edition”—as close to the author’s

intention as surviving evidence permits, but also to give the reader

all the information on that text.

As might be expected with a work as important as Moby-Dick,

there are those who disagree with the NN editorial policies. In 2007,

John Bryant and Haskell Springer published the Longman Critical

Edition, which indicates the differences between the first American

and first English editions with the use of gray type. The editors

discuss any extensive difference in a “Revision Narrative” that

appears on the same page. Therefore, the differences are visually

obvious to the reader during the act of reading.

One might wonder if, after 160 years, it is still possible to create a

new edition of Moby-Dick.The answer is a resounding yes. In 2009,

librarian Matt Kish began a project during which every day he

selected a phrase, theme, or quotation from each page of the Signet

Classics edition of Moby-Dick and translated it into a piece of art that

he then posted on his blog. It took him 543 days to illustrate the 552

pages. As Kish writes: “At first, I had identified with Ishmael, feeling

like a passenger, a silent observer, on a doomed journey that I had

no real control over. But as I started working through the second half

of the book, I began to identify more and more with Ahab, obsessed

with the idea of the White Whale and the task of finally finishing the

art and slaying the monster. I worked harder and harder each day. I

lost sleep.” Published as Moby-Dick in Pictures in 2011, the result is

visually stunning and evocative.____________________________________________________________

Mary K. Bercaw Edwards is a Melville scholar, author of Cannibal Old Me: SpokenSources in Melville’s Early Works (2009) and Melville’s Sources (1987), and editor ofWilson Heflin’s Herman Melville’s Whaling Years (2004). An Associate Professor ofEnglish and on the Maritime Studies faculty at the University of Connecticut, Dr.Bercaw Edwards works aboard the Charles W. Morgan, only remaining whaleship,berthed at Mystic Seaport, and has accrued 58,000 miles at sea under sail.

“Very Like a WhaLe’: EDiTions of Moby-Dick

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 16

Spring 2012 | 17

By Kenneth Roman

James Thurber’sbook jacketillustration for Morris Ernst’s The Best Is Yet…(1945).

HE WASN’T A BIKER HIMSELF. It was a matter of PRINCIPLE for

Morris Ernst. IT WAS GOOD FOR NANTUCKET. An inventive lawyer, he had

a knack for getting things done. If the law said the state would fund roads for

wheeled vehicles, he would point out that it did not say HOW MANY wheels.

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 17

18 | Historic Nantucket

FREE SPEECH AND BIKE PATHS

That led to funding for the Milestone Road bike path, which heinspired and promoted. It was the first leg of Nantucket’s belovedand still growing web of island bike paths. “Nantucket doesn’t needmore roads,” he observed.On another matter of principle, government censorship of books,

he became famous to generations of literature lovers when hesuccessfully argued before the U.S. District Court to get James Joyce’sUlysses, the groundbreaking novel of the twentieth century, admittedinto this country. Until he won that case in 1933, Victorian-eraobscenity laws permitted the federal government to decide whatpeople could and could not read. It was a matter of principle forErnst: the right to free speech.

eRnst wAs one of the mostsignificant public intellectuals inthe 1920s and 1930s, and afamiliar presence on Nantucket,with a home in Monomoy. Hewas a force, full of ideas andalways working to make themhappen, remembers his friendBob Mooney, then a rising locallawyer. “You ought to dothis. . . .” was one of his favoriteexpressions.The idea for a bike path came

from President Eisenhower’sphysician, Paul Dudley White.White instructed his famouspatient to get some exercise andget back on the golf course afterhis heart attack while in office in1955. Until that time, doctorsadvised their patients to stayquiet, often in wheelchairs, andrest. The energetic Dr. Whitegenerated publicity for exercise anda healthy lifestyle by riding his bikeeverywhere. Newspapers lovedrunning photos of the biking Massachusetts General Hospitalcardiologist.But when he vacationed on Nantucket for several summers,

White found no good, safe place to ride. Bob Mooney had beenelected to the State House of Representatives, so he and Ernst startedto work together with Dr. White. “Oh dear, is this biking again?” saidWhite’s secretary when Mooney called for an appointment. “That’sall he talks about.” The first bill Mooney proposed—in 1957—was forthe ’Sconset bike path, along Milestone Road, the first one funded bythe Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Dr. White testified for the bill,came to Nantucket for the opening, and cut the ribbon. Afterwards,Ernst, “a flaming liberal,” in Mooney’s words, took White to theairport. They talked biking, and he thanked the doctor for keeping Ikealive—and “keeping that Nixon [Eisenhower’s Vice President] out ofthe White House.” Ernst and his wife, Margaret, first stayed at the White Elephant

when they came to Nantucket in the 1920s. One day in 1927, he lookedacross the harbor at Monomoy, which had been cleared years earlierfor sheep- and cattle-raising and was still sparsely populated with onlya few houses, and mused, “That would be a good place to have ahouse.” All his friends in town thought it was crazy, remembers hisgranddaughter Debbie (who still lives on island), “because of all themosquitoes, and it took the northeast storms on the nose.” Even AnneCongdon, who owned the 600-foot vacant waterfront lot he wanted,tried to warn him. He couldn’t stop winter storms, but he could dealwith mosquitoes, so he bought the land and got the mosquitocommissioner to dig a drainage ditch and let the water out of the

swamp. The house he built at 64Monomoy Road was modeled on theWhite Elephant and designed by itsarchitect, Edward Ludwig. It was adecision he would not regret: “Everydollar I put into that house wouldhave been lost in the stock market.”It was followed by three smaller

cottages, for each of his children. “Ican visit you at any time,” heannounced to them. “You can comewhen invited.” Over time, hebecame one of three majorlandowners in Monomoy Heights,along with James H. Gibbs andFrederick A. Russell. When he diedin 1976 at 87, the Inquirer andMirror wrote that “Nantucket haslost one of its best known and mostloyal longtime summer residents.For some fifty years Mr. Ernst hastaken advantage of everyopportunity to escape from the cityto spend maybe only a weekend,

maybe a couple of months, at hishome in Monomoy, where he couldrelax, indulge in his favorite pastime—

sailing—and greet his friends at leisure.”A self-tAught sAiloR,he learned navigation from a book. His

sailing started with a Crosby 12� or 14� catboat. “He used to hit all theboats going in and out, learning to sail,” says his son Roger. Thecatboats were replaced by a Wianno 25� gaff-rigged schooner, whichhe used to cruise to Maine, including visits with New Yorker writer E.B. White, Thomas Lamont of J. P. Morgan, and Connecticut GovernorChester Bowles. Sailing to Campobello to visit President FranklinRoosevelt, he was accompanied by his wife, Margaret, a trueSouthern lady who wore a dress even on the sailboat, and hadbecome close friends with Eleanor Roosevelt.His fleet grew successively with a 39� ketch, a 35� cutter and, after

World War II, a 33� Hinckley. Along the way, he persuaded men workingon the ship channel to dredge a five-foot channel to his dock. Since hecouldn’t get into the Nantucket Yacht Club at that time (a nonobservantJew, he also represented the non-theistic Ethical Culture Society as its

Morris and Margaret (Maggie) Ernst enjoying a sail. SCAN GIFT OF DEBBIE NICHOLSON, SC873-1

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 18

Spring 2012 | 19

lawyer), he became a founding member of the short-lived NantucketBoat Club, quartered on the third floor of the Granary on Old SouthWharf. Leisure is a relative concept. A Wharf Rat, he also held court on the

Main Street bench. He played golf (not well, but felt he should do it) atTupancy Links. He taught himself carpentry, and built a playhouse forhis grandchildren; in the winter, he lent his tools to his caretaker,Leroy True, to use at the Coffin School’s manual-training courses. Heplayed the piano and the cello, skills he practiced at Williams College.

And he wRote—a book every other summer, authoring orcoauthoring twenty-one volumes of essays and personal memoirs.From America’s Primer in 1931 to Privacy, or The Right to Be Let Alonein 1962, interspersed with commentaries (The Censor Marches On andThe First Freedom) and memoirs (The Best Is Yet and UNTITLED: TheDiary of my 72ndYear).He had close personal relationships

with public figures. Justice LouisBrandeis, New York Governor HerbertLehman, Vice President Henry Wallace,Boss Hague of Jersey City, New York’sMayor Fiorello LaGuardia, andPresidents Harry Truman and FranklinRoosevelt. In 1933, FDR stayedovernight in Nantucket Harbor on hisschooner Amberjack II.Ernst’s law firmrepresented Edna Ferber, E. B. White,Groucho Marx, Al Capp, CharlesAddams, Grandma Moses, HeywoodBroun, Margaret Bourke White, RussellCrouse, and George S. Kaufman. Heknew them all, and got many of themto Nantucket. Robert Benchley was aclient and friend.Ernst compared his two favorite

islands, Manhattan and Nantucket,claiming it was the summer on Nantucketthat enabled him to survive another winter in Manhattan. In New York, he was a bon vivant, going to

the theater and dining with clients and friends at “21”, Sardi’s, andthe Algonquin (home of the Round Table). He decided to bringsinger Marian Anderson to lunch at the Algonquin and told theproprietor, Frank Case, he wanted his usual table—up front. “You’regoing to scare off a lot of people,” said Case, “she’s black.” “Nevermind,” replied Ernst, “we’ll do it.” Anderson became the first blackwoman to be served at the Algonquin. Born in Uniontown, Alabama in 1888, he grew up in New York; his

Czech father and German mother moved the family there when hewas two years old. After graduating from Williams College, he made aliving in the shirt business and as a furniture salesman, until hediscovered he could go to the New York Law School at night. Upongraduating, he cofounded the firm of Greenbaum, Wolff & Ernst withtwo classmates (they never had more than an oral agreement) andspent the rest of his career there.

A short, wiry man, with alert eyes behind his wire-rimmedglasses, on Nantucket he dressed as casually as possible—usually ina tee shirt and Bermuda shorts. Seeing him in town one morning,Bob Mooney mentioned that he was getting married that afternoonat St. Mary’s Church and invited Ernst. “Do I have to get dressed up?”he asked. Mooney describes him as “peppy, always talking.” The Ernst home was disciplined. He took a cold shower every

morning. There was a dictionary and an atlas on the breakfast table.The children had to make something in his workshop every summer(“you have to earn your rights”). Houseguests were given projects aswell; everybody had to sign up on a pad posted on the swinging doorto the kitchen. There’s a photo of his client, Edna Ferber, cutting thegrass. Over the course of a sixty-six-year legal career, Ernst championed

every major social movement of the time: labor rights, civil rights, freespeech, birth control—causes not allpopular on conservative Nantucket. Adedicated New Deal Democrat, hebecame a close friend of Cora Stevens,head of the local RepublicanCommittee. “They found commonground in what’s good for America,”explains his son Roger.

he ARgued (And won) morecontroversial cases in New York and inFederal courts than any other lawyerof his era. A friend described him as “adefender of really unpopular causesthat are really unpopular.” Hedemonstrated early support of gay andlesbian rights by inviting hispsychiatrist friend Fran Arkin toNantucket, with her female partner. The case that elevated Ernst to the

national scene was United States v. OneBook Called Ulysses, argued in the U. S.District Court in New York. The publisherwas so doubtful of the case’s success thatits president, Bennett Cerf, required

Ernst to take a share of the book’s royalties in lieu of his usual legalfees. First published in France, the novel could not be brought into theU. S. because it was judged to be obscene. Random House, with Ernstas its counsel, arranged a test case to challenge the implicit ban, andimported the French edition so it could be seized by the U. S. CustomsService. There was no trial as such; both parties stipulated the facts. The U. S. District Attorney asserted the work contained sexual

stimulation (notably in Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in the last chapter),was blasphemous in its treatment of the Catholic Church, andsurfaced coarse thoughts usually repressed. Attorney Ernst arguedthat the book should be considered in its entirety as a work of “artisticintegrity and moral seriousness” and not just on selected passages,that it was not obscene in that it did not promote lust, and that it wasprotected by the First Amendment to the U. S. Constitution. Judge John M. Woolsey’s trial court opinion, said to be the most

Dr. Paul Dudley White and Robert Mooney celebrate theopening of the ‘Sconset Bike Path, August 13, 1958. BILL HADDON PHOTO

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 19

20 | Historic Nantucket

widely distributed judicial opinion in history, is reproduced in allRandom House printings of the novel. Judge Woolsey determined thatportraying the coarse inner thoughts of the characters was necessaryto show how their minds operated, and presented a “true picture” oflower-middle-class life, drawn by a “great artist in words” who hasdevised “a new literary method of the observation and description ofmankind.” On the issue of obscenity, he wrote: “Whilst in many placesthe effect of Ulysses on the reader undoubtedly is somewhat emetic,nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac.” His ruling was affirmed bythe U. S. Court of Appeals.

the decision to Admit the book into the country came the sameweek in 1933 as the repeal of Prohibition. Ernst saw a parallel. In hisforeword to the first legally published edition in the U. S., he wrote,“Joyce’s masterpiece, for the circulation of which people have beenbranded criminals in the past,may now freely enter thiscountry. . . . We may now freelyimbibe of the contents ofbottles and forthright books.”His defense of Ulyssesredefined American legalinterpretation of the FirstAmendment, and made thebroader case for literaryfreedom.Ernst took on censorship in

many areas, including lack ofreproductive rights forwomen. Working withMargaret Sanger in the earlydays of the birth-controlmovement, he set up a testcase by shippingcontraceptives to Connecticut(where they were illegal), andarranging to have the recipientarrested on arrival of the packages from the post office. He took thatcase to the Supreme Court, helping cement the legality of birthcontrol. From birth control to death with dignity, he represented the“right-to-die” Hemlock Society, and helped them get started.He helped found the predecessor organization to the American

Civil Liberties Union, working closely with its first president, RogerBaldwin (for whom his son Roger is named). A strong supporter of J.Edgar Hoover and the FBI, Ernst led the drive to ban Communistsfrom the ACLU, a move that baffled and angered many of his civillibertarian friends. He argued that his anticommunism was anextension of his liberal values, especially the promotion of dueprocess and a “marketplace for ideas” and information needed for afree society. As attorney for a number of labor unions, he went before the

Supreme Court in 1937 to uphold the constitutionality of the NationalLabor Relations Act (the Wagner Act), establishing the right of mediaemployees to organize labor unions. His counsel was sought at the top government levels. President

Harry Truman appointed him to the Civil Rights Commission; NewYork Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia employed him as a labor arbitrator;he was in President Roosevelt’s office almost every week, andbecame FDR’s personal representative on overseas missions duringWorld War II. To make a point, he sent Roosevelt two packages through the

mail—same price, same weight, one containing the Bible and theother just junk. “Why did you send these?” asked the President.“Because if you open them, you’ll realize they’re quite different. Butthey cost the same, and they shouldn’t. Good literature ought to becheaper or, put it the other way around, junk mail ought to be moreexpensive.” “Go see the Postmaster General, and fix it,” said Roosevelt.With James Farley, he wrote the bill to provide book-rate postage, anice benefit for his several publisher clients.

Bike paths weren’t his onlycause on Nantucket. He wasinstrumental in reorganizingthe boat line. At that time, theNantucket ferry first went toMartha’s Vineyard and NewBedford, tying up the boat forhalf a day before coming toNantucket. Ernst worked withthe Town Crier, then thesecond paper on the island, topromote a “citizen’s crusade”to get a more direct route.

A populAR speAKeR at theWinter Club, the Rotary, andother organizations, he wasknown for his humorous andinteresting talks, and wasgenerally available as “thefogbound speaker,” if the

invited speaker couldn’t make itto the event—a tradition followed

by his diplomat son Roger, who still summers in one of the threesurviving Ernst cottages.Roger believes the trait that helped his father make friends in

both places —often on opposite sides of issues—was his ability tobring people together through informal diplomacy. He sought tofind the common ground of a solution rather than litigation of rightand wrong. “What kind of man is this?” his publisher asked rhetorically. “The

Daily Worker calls him ‘fascist’; right-wing senators insist he talks theCommunist line. His law office in New York City is said to be the onlyone where the office boys consider a senior partner too radical. MorrisErnst is often at the center of the controversy he so dearly loves. Hehas unlimited zest—for people, for natural phenomena, for living. Heis a happy man.” _____________________________________________________________

Kenneth Roman, a thirty-two-year seasonal resident of Monomoy, is a formerchairman of Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide and author of several books, including abiography of David Ogilvy.

The Ernst compound in Monomoy, 1950s. SCAN GIFT OF DEBBIE NICHOLSON, SC873-3

FREE SPEECH AND BIKE PATHS

32645 Nantucket Historical_Layout 1 4/17/12 9:44 AM Page 20

Spring 2012 | 21

BY ROBERT HELLMAN

n my “Nantucket Whalecraft” article, which appeared

in the Fall 2011 issue of Historic Nantucket, I discussed

an account book kept in Nantucket by an unidentified