High yields and bee pollination of hermaphroditic rambutan … · Beaucoup de plantes cultivées...

Transcript of High yields and bee pollination of hermaphroditic rambutan … · Beaucoup de plantes cultivées...

Fruits 2015 vol 70(1) p 23-27ccopy Cirad EDP Sciences 2015DOI 101051fruits2014039

Available online atwwwfruits-journalorg

Original article

High yields and bee pollination of hermaphroditic rambutan(Nephelium lappaceum L) in Chiapas Mexico

Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales1 David W Roubik2 Miguel A Guzmaacuten3 Miguel Salvador-Figueroa1Lourdes Adriano-Anaya1 and Isidro Ovando1

1 Centro de Biociencias Universidad Autonoma de Chiapas Carretera a Puerto Madero km 20 Tapachula CP 30700 Chiapas Mexico2 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Ancon Balboa Republica de Panama3 El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR) Carr Ant Aeropuerto km 25 Tapachula CP 30700 AP 36 Chiapas Mexico

Received 20 February 2014 ndash Accepted 9 September 2014

Abstract ndash Introduction Many cultivated plants do well with exotic pollinators and native pollinators can alsoserve exotic crops Both can be optimized for agriculture We studied Nephelium lappaceum L (Sapindaceae) anandro-dioecious Asian plant in tropical Mexico The hermaphrodite flowers were not known to shed viable pollen andoutcrossing from male pollinating plants was thought essential for efficient horticulture Materials and methods Weused the locally developed CERI61 variety of rambutan and conducted experiments on pollination and fruit yield Anorchard of 1000 trees was studied intensively during two flowering seasons in Chiapas Mexico Plantation yields wererecorded for 10 years We compared open pollination experiments with pollinator exclusion and lsquoinduced pollinationrsquotreatments We caged some trees with colonies of stingless bees Scaptotrigona and Tetragonisca Results and discus-sion Caged flowers produced fruit with no male plant present Pollen dehisced and was viable on approximately 5of flowers Trees caged with pollinators and open pollination treatments revealed 91 times more mature fruit than treeswithout pollinators Fruit mass was significantly higher in induced pollination treatments Yields exceeding 7 t haminus1

were obtained during a ten-year test period Scaptotrigona mexicana (Apidae Meliponini) was the main pollinator fol-lowed by social halictid bees (Halictus hesperus) Feral Africanized honeybees were not strongly attracted to flowersConclusion Both stingless bee species in open pollination treatments and within cages showed that fruit productionincreased nearly 10-fold in this variety of rambutan Although outcrossing versus selfing did not affect initial maturefruit set a superior fruit yield in weight and size was obtained from selfing mediated by pollinators in caged trees

Keywords Mexico Chiapas rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) pollinators Apidae bees selfing

Reacutesumeacute ndash Ameacutelioration des rendements et pollinisation par des abeilles du rambutan hermaphrodite(Nephelium lappaceum L) dans le Chiapas Mexique Introduction Beaucoup de plantes cultiveacutees srsquoaccommodentde pollinisateurs importeacutes mais les pollinisateurs naturels contribuent eacutegalement agrave la reacutecolte de fruits exotiquesLes deux types peuvent ecirctre optimiseacutes pour lrsquoagriculture Nous avons eacutetudieacute le rambutan Nephelium lappaceum L(Sapindaceae) une espegravece fruitiegravere asiatique andro-dioiumlque dans les conditions tropicales du Mexique Les fleurs her-maphrodites ne sont pas connues pour libeacuterer du pollen viable aussi la participation des plantes macircles feacutecondantes estessentielle en horticulture productive Mateacuteriel et meacutethodes Nous avons testeacute la varieacuteteacute CERI61 deacuteveloppeacutee locale-ment en expeacuterimentation agronomique portant sur le rendement en fruits et sur la pollinisation Un verger de 1000 arbresa eacuteteacute eacutetudieacute intensivement pendant deux saisons florifegraveres dans le Chiapas Les rendements fruitiers du verger ont eacuteteacuteenregistreacutes sur 10 anneacutees Nous avons compareacute les traitements entre une pollinisation ouverte avec exclusion de toutpollinisateur et une laquo pollinisation forceacutee raquo Quelques arbres ont eacuteteacute maintenus en cage avec des colonies drsquoabeillessans dard Scaptotrigona et Tetragonisca Reacutesultats et discussion Des fleurs en cage ont produit des fruits en lrsquoab-sence de toute plante macircle Le pollen produit eacutetait deacutehiscent et viable sur pregraves de 5 des fleurs Les traitements encage avec des pollinisateurs et en pollinisation ouverte ont reacuteveacuteleacute 91 fois plus de fruits arrivant agrave maturiteacute qursquoen lrsquoab-sence de pollinisateurs La masse de fruits reacutecolteacutes eacutetait significativement plus eacuteleveacutee suite aux traitements drsquoinductionde pollinisation que dans tout autre traitement Des rendements exceacutedant 7 t haminus1 ont eacuteteacute obtenus sur une peacuteriode-testde dix ans Scaptotrigona mexicana (Apidae Meliponini) eacutetait le pollinisateur principal recenseacute suivi par des abeilleshalictid sociales (Halictus hesperus) alors que les abeilles africaniseacutees sauvages nrsquoont pas eacuteteacute fortement attireacutees par

Corresponding author isidroovandounachmx

24 Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27

les fleurs de rambutan Conclusion Lrsquoespegravece drsquoabeille sans dard utiliseacutee tant dans des traitements de pollinisationouverte que sous cage a contribueacute agrave une augmentation proche de 10 fois la reacutecolte de fruits de cette varieacuteteacute de rambutanBien que la feacutecondation croiseacutee nrsquoait pas affecteacute la mise agrave fruit initiale par rapport agrave lrsquoautofeacutecondation un rendementsupeacuterieur a eacuteteacute obtenu en poids et en taille de fruits gracircce aux pollinisateurs sur fleurs en cage

Mots cleacutes Mexique Chiapas rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) animal pollinisateur abeilles autopollinisation

1 Introduction

Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L Sapindaceae) isa tropical plant that produces edible fruits and originatesfrom Malaysia and Indonesia According to FAO data thisfruit tree is being developed for commercial exploitationand the market is expanding rapidly Rambutan is nowa-days commercially grown in Southern Asia Australia theCaribbean India Sri Lanka Florida Hawaii and South andCentral America [1] However there is little information aboutits pollinators or insect flower visitors In nature rambu-tan plants are dioecious with about 50 male and 50hermaphrodite plants Therefore in commercial orchards onlyhermaphrodite plants are grown where most of them are func-tionally female For example in the Philippines the culti-vars ldquoMaharlikardquo and ldquoSeematjanrdquo produced about 9994and 9955 hermaphrodite functionally female flowers re-spectively [2] No functional pollen is supposed to be pro-duced by such andromonecious plants which is being ob-served in Australia where isolated trees with low functionalmale hermaphrodite flowers rarely set fruit satisfactorily [13]In Southeast Asia where rambutan is native cross pollinationby hand increases fruit set 13 times beyond the 1 found innatural conditions whereas bagged flowers fail to set fruits [3]Recent studies in India find the stingless bee Tetragonulairidipennis and Indian honeybee Apis cerana dominant for-agers on N lappaceum [4]

In our study region rambutan was introduced during1950minus1970 as an economic alternative to coffee mango orbanana and is now widely cultivated due to favorable agro-ecological conditions [5ndash7] Nonetheless few studies haveexamined the pollination system and insect visitors integralto a sound production technology We performed studies onpollen and fruit production in a commercially grown variety oframbutan in Chiapas Mexico by recording fruit yield pollendehiscence and viability flower visitors and pollinator man-agement in a commercial orchard with a fruit tree populationpreviously believed to be functionally female

2 Materials and methods

Our studies were performed on a commercial rambutan va-riety denominated ldquoCERI61rdquo by the Rosario Izapa experimentstation Mexican Institute of Forestry Agriculture and Live-stock Research In the Soconusco region rambutan varietiesintroduced from Malaysia and Indonesia were reproduced byseed and selected from plantations at this station In subse-quent plantings using grafted materials a genetic uniformitywas reached with smaller trees showing a good production andquality for marketing [5] The CER161 hermaphrodite varietywas studied in a 7 ha orchard of approximately 1000 trees

with no male individual trees flowering within the study areaor nearby This orchard at ldquoEl Herraderordquo ranch in the Metapade Dominguez municipality Chiapas Mexico (144948 N921132 W) is located at 100 m elevation Two flowering peri-ods were intensively studied each between January and Junein 2001 and 2002 Observations on fruit set (both initial andfinal) flower visitors and floral characteristics were repeatedin 2003ndash2004 The climate is hot and humid with abundantsummer rain [8 9] The habitat surrounding the orchard in-cludes orchards of mango (Mangifera indica L) Native sec-ondary vegetation commonly includes Ficus spp Tabebuiarosea (Bertol) DC Spondias mombin L S purpurea L Cy-bistax donnell-smithii (Rose) Seibert Tecoma stans (L) Jussex Kunth Ceiba pentandra (L) Gaertn and Pachira aquaticaAubl [9]

To determine the effects of flower visitors on the small(4 mm) apetalous and greenish flowers of rambutan ten treeswith six marked panicles were used for each of three experi-mental treatments The control treatment (T1) was open pol-lination without manipulation while (T2) excluded all visi-tors with a 1 mm mesh bag placed over the panicle in budstage (bagged flowers) The third treatment (T3) called ldquoin-duced pollinationrdquo was simultaneous with the other two Forthis we placed cages over trees with buds in the same stageas T1 and T2 and two bee colonies were placed at oppo-site ends of the 16 times 16 times 4 m cage The local stingless bees(Meliponini) in wooden hives were Scaptotrigona mexicanaGueacuterin-Meacutelenville and Tetragonisca angustula Lat whichmaintain colonies with approximately 1000 foragers They areconsidered as common flower visitors to rambutan in our re-gion From the marked panicles in each treatment final de-veloping fruits were scored and assessed at the time of com-mercial harvest In order to estimate the proportion of flowersproducing fruit total flowers were counted in bagged panicleson 10 trees

Flower visitors were sampled intensively from trees byplacing a large net-tent over an entire tree The net mesh was1 mm and the tent 3 m on each side An individual tree wascovered after which insects were collected in tubes contain-ing ethyl acetate Collections were made on separate trees at agiven hour between 7 am and 5 pm every 15 days from Febru-ary through March 2001 and from February through April2002 Bees and other insects were identified by using taxo-nomic keys of Ayala [10] and Michener [11]

3 Results and discussion

Initial fruit set differed nearly ten-fold among the threetreatments (ANOVA P lt 0001) Developing and mature fruitper flower were most abundant in the open pollination treat-ment in both years (Duncan and Tukey tests P lt 0001

Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27 25

Table I Fruits produced and fruit mass in three treatments on rambutan variety CERI61 induced pollination (bee colonies present in cage)open flowers and bagged flowers with no visitor at Metapa de Domiacutenguez Chiapas Mexico

TreatmentVariable Induced pollination Open pollination Bagged flowers

2001 2002 2001 2002 2001 2002

Set Fruit 764 plusmn 272B 714 plusmn 212B 968 plusmn 377A 1101 plusmn 462A 70 plusmn 80C 56 plusmn 39C

Mature Fruits 212 plusmn 61A 171 plusmn 65A 228 plusmn 93A 231 plusmn 79A 18 plusmn 32B 34 plusmn 33B

Fruit mass (g) 222 plusmn 21B 284 plusmn 32A 155 plusmn 06C 151 plusmn 03C 138 plusmn 05D 126 plusmn 07E

All treatments included a similar number of flowers (1 804 plusmn 503 in 2001 and 1 749 plusmn 545 in 2002 P lt 005) Data are means (plusmnstandarddeviation) of 10 biological replications Cells with the same letter in a given row are not significantly different (Tukey test α = 001)

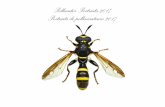

Figure 1 Anther of Nephelium lappaceum from hermaphrodite flowers Left stamen with opened anther middle magnifications of anthersand right pollen grains

table I) but no statistical differences existed between inducedpollination (in cages) and open pollination The fruit mass wassignificantly greater in induced pollination treatments (table I)which also resulted in greater seed mass and fruit length (datanot shown) The open pollination treatment of 2001 and 2002registered the highest fruit set due to the larger number offlowers present on panicles (1 804 plusmn 503 and 1 749 plusmn 545 re-spectively) (table I) In contrast the bagged flowers treatmentregistered the lowest fruit set (table I)

Flowering began early in February and ended in Aprilreaching a maximum during March The effective flower-ing period was 30 plusmn 5 days All flowers on panicles werehermaphrodite and approximately 5 of them had pollen onanthers that dehisced and remained present upon stamens upto two days when the stamens wilted (figures 1 2)

Many developing fruit dropped during the first four weeksafter flowering with 50 lost and an additional 15 was lostby the seventh week By fruit maturity at 11 weeks little ad-ditional loss occurred With the introduction of stingless beehives on this ranch from 2000 to 2004 the average yield in-creased from 35 to 70 t haminus1

A total of 28186 individual bees were collected on flow-ers which represented 971 of the total insects taken inFebruaryndashMarch 2001 and FebruaryndashApril 2002 (table II)The peak insect visitation was observed between 10 am and11 am (468 and 416 in average respectively) Two bee fami-lies Apidae (Tetragonisca Trigona Oxytrigona Nannotrig-ona Apis Exomalopsis Paratetrapedia and Scaptotrigona)and Halictidae (Halictus) visited flowers first collecting asmall amount of pollen and nectar then collecting almost ex-clusively nectar after 10 am Visitors carried only small pollen

Figure 2 Scaptotrigona mexicana on a hermaphrodite flower oframbutan in the Soconusco region

loads on their hind legs When subjected to microscopic studypollen loads consisted of Asteraceae Euphorbiaceae and otherflowering plants common in the area Scaptotrigona mexi-cana dominated flowers during the end of flowering in MarchndashApril 2001 with 3512 individuals and 8164 of all collectedbees Halictus hesperus a social but not perennial bee domi-nated flowers in April 2001 after most flowering had occurredOur results agree with those Shivaramu et al [2] from In-dia reporting a stingless bee (T iridipennis) as a predominantforager

Rambutan produces hermaphrodite flowers that are tradi-tionally viewed as functionally pistillate [2] Recent studies inAsia indicate rambutan is a cross pollinated plant and dependson insects for pollination and fruit set [2] However Kiew [12]

26 Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27

Table II Richness and abundance of bees collected in two flowering periods in rambutan flowers at ldquoEl Herraderordquo ranch (Metapa deDomiacutenguez Chiapas Mexico)

Bee species February March April Total Relative abundance ()Apidae Apinae

Apis mellifera 3 1 1 5 002Apidae Apinae

Scaptotrigona mexicana 2840 4819 2063 9722 3449S pectoralis 58 49 16 123 044

T(Tetragonisca) angustula 659 171 23 853 302Nannotrigona pelilampoides 204 48 105 357 127Trigona fulviventris 21 21 12 54 019T nigerrima 27 8 3 38 013Oxitrigona mediorufa 43 ndash 2 45 016

Apidae AntophorinaeExomalopsis sp1 10 4 ndash 14 005Paratetrapedia sp1 1 2 ndash 3 005

HalictidaeHalictus hesperus 27 973 13675 14675 5207Lasioglossum sp1 4 98 1409 1511 536Lasioglossum sp2 ndash 57 555 612 217Lasioglossum sp3 15 15 127 157 056Agapostemon aff splendens 7 5 4 16 006Total of bees 3919 6271 17995 28185 10000

stated that rambutan is not bee pollinated but apomictic andparthenocarpic because hermaphrodite flowers do not releasepollen and male plants are not cultivated because they produceno fruit In contrast Nakasone and Paull [3] listing seven cul-tivars of rambutan used in Thailand Indonesia and Malaysiastated that even with no male trees present mixed plantingsgiven flowering synchrony provided acceptable yields Yieldsin plantings not meeting such conditions were exceedinglylow

Our data strongly suggest that hermaphroditic flowers canhave viable pollen which must be transferred by a pollinatorfor the production of mature fruit The pollen grains dehiscedand were fully formed (figure 1) on the anther surface in con-trast to deformed pollen found on functionally female but ap-parently hermaphroditic flowers in Decaspermum [13] In ad-dition pollen grains kept in a 20 sucrose solution initiatedpollen tube growth Both geitonogamy and outcrossing werepossible but there is no convincing evidence for apomixis inour rambutan variety because occasional autogamy cannot bediscounted The ldquoinduced pollinationrdquo treatment which couldonly result in geitonogamy produced significantly lower initialfruit set but equally abundant ripe fruit in both years comparedto the open pollination treatment (table I) In contrast the flow-ers caged to exclude all pollinators produced almost no fruitwhich is not a condition expected if apomixis occurred

The interpretation that fruit initiation was higher whensome outcrossing pollen was deposited on stigmata by beesis consistent with the initial fruit set but the yield in maturefruit could not reach that provided by full self pollination (ta-ble I) Any conceivable apomixis was greatly outweighed bygeitonogamy facilitated by pollinators

In some self-fertilizing plants fruit set may be stronglyincreased by the diversity and abundance of flower-visitingbees [14ndash16] For example commercial yield of Coffeaarabica increased 56 in open pollinated treatments opposed

to autogamous and bagged treatments [17] Our results agreewith these C arabica studies because rambutan flowers ex-posed to S mexicana produced 91 times more mature fruitsthan the treatment without pollinators The bees presumablyvisited many flowers to obtain a nectar load and are knownas group foragers [18] Small bees are generally thought tofavor pollination of small generalized flowers [19] MostScaptotrigona had gathered negligible nectar when sampled onflowers and Apis mellifera scutellata present on a few flowerswas not strongly attracted to rambutan although its flowers oc-cur in dense clusters on large panicles A small amount of floralnectar reward scramble competition or both likely discour-aged this honey bee from greater visitation despite an unusu-ally high sugar nectar reward gt50 by weight Although theHalictus nested in the ground near the orchard and in the gen-eral area [20] it also appeared at rambutan flowers in increasingfrequency when numbers increased in tent traps placed overtrees [21] This seasonal social bee was a significant visitorseen on the flowers and not merely flying into the traps Otherstudies also find numerous social bees visiting rambutan [3]The insignificant production of fruit in their absence indicatesthis plant depends on the action of small bees to stimulate fruitset and retention Since H hespersus was active only duringlate flowering season it was unable to provide much pollina-tion service in our studies

This is the first study of which we are aware in a plantdescribed as dioecious that implies selfed flowers gain greatermaternal investment in fruit than outcrossed flowers Althoughwe did not experimentally outcross and self flowers on thesame plant to test this conclusion we expect that our openpollination treatments included bees that transported pollenbetween compatible flowers If the orchard was essentially asingle self-fertile clone the outcrossing would have little ef-fect but fruit production in cages compared to open plantswould not be so large nor would fruit drop by potentially

Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27 27

outcrossed plants be relatively larger than that of strictly selfedplants In theory selfing should help to purge lethal alleles [22]and in natural conditions protogyny could offset the tendencyof geitonogamy to monopolize maternal resources The largeproportion of dehisced fruits suggests maternal discriminationbased upon fruit genotype

4 Conclusion

Fruit abundance for commercial rambutan is reported to be10 to 20 per panicle in Costa Rica [23] compared to 21 in thepresent study while fruit number in Malaysia is lower [24] Inthe latter study and in Chiapas fruit size was very similar Tothe producers of rambutan it is of special interest that the totalyield (weight of individual fruit multiplied by fruit retained perpanicle) was highest in the induced pollination treatment (incage) This implies that controlled production in greenhousewith pollinators can provide relatively high yields The yieldsat our Metapa orchard were over twice that of the leading pro-ducers (in Thailand) of Nephelium lappaceum [25] Thailandhas approximately the same number and size of stingless beespecies as Chiapas but also possesses five honey bee speciesIn both hemispheres increasing productivity through polli-nator management seems possible and desirable Because ofthe number and availability of pollinators and particularly themanagement of Scaptotrigona in our Chiapas site rambutanorchard pollination is likely to be efficient as well as economi-cally sound

Acknowledgements The authors thank the Instituto parael Desarrollo Sustentable en Mesoameacuterica AC (IDESMAC)for supporting thesis development (MAG) Ing Alfonso Espino fororchard facilities the students of Biotechnology at UNACH forfield assistance and G Nieto for electronic microscope imagesDWR acknowledges Baird fund support Smithsonian Institution Wethank Julieta Grajales-Conesa for her advice and support during thecorrection of the manuscript

References

[1] Sivakumar D Wijeratnam W Wijesundera R AbeyesekereM Control of postharvest diseases of rambutan using cin-namaldehyde Crop Prot 21 (2002) 847ndash852

[2] Tindall H Rambutan cultivation FAO Plant production andprotection paper 1994

[3] Nakasone HY Paull RE Tropical fruits CAB IntWallington UK 1998

[4] Shivaramu K Sakthivel T Rami-Reddy PV Diversityand foraging dynamics of insect pollinators on rambu-tan (Nephelium lappaceum L) Pest Manag Hort Ecosyst18 (2012) 158ndash160

[5] Vanderlinden EJM Pohlan AAJ Janssens MJJ Cultureand fruit quality of rambutaacuten (Nephelium lappaceum L) in theSoconusco region Chiapas Mexico Fruits 59 (2004) 339ndash350

[6] Perez RA El rambutaacuten en Mesoameacuterica gestacioacuten de una re-alidad empresarial Rev AgriCult 3 (2000) 35

[7] Kido S El estudio de desarrollo integral de agriculturaganaderiacutea y desarrollo rural de la regioacuten del Soconusco enChiapas JICA Mexico 1999

[8] Garcia E Modificaciones al sistema de clasificacioacuten climaacuteticade Koppen Universidad Nacional Autoacutenoma de Mexico 1973

[9] Rzedowski J Vegetacioacuten de Mexico Limusa Mexico 1978[10] Ayala R Revisioacuten de las abejas sin aguijoacuten de Meacutexico

(Hymenoptera Apidae Meliponini) Folia EntomoloacutegicaMexicana 106 (1999) 1ndash123

[11] Michener CD The bees of the world Johns Hopkins UnivPress Baltimore 2nd ed 2007

[12] Kiew R Bee botany in tropical Asia with special referenceto peninsular Malaysia in Kevan PG (Ed) The Asiatic hivebee apiculture biology and role in sustainable development intropical and subtropical Asia Enviroquest Cambridge Ontario1995 pp 117ndash124

[13] Kevan PG Lack AG Pollination in a cryptically dioeciousplant Decaspermum parviflora (Lam) A J Scott (Myrtaceae)by pollen-collecting bees in Sulawesi Indonesia Biol J LinnSoc 25 (1985) 319ndash330

[14] Heard AT The role of stingless bees in crop pollination AnnuRev Entomol 44 (1999) 183ndash206

[15] Richards AJ Does low biodiversity resulting from agriculturalpractice affect crop pollination and yield Ann Bot 88 (2001)165ndash172

[16] Roubik DW The value of bees to the coffee harvest Nature417 (2002) 708

[17] Klein AM Steffan-Dewenter I Tscharntke T Bee pollinationand fruit set of Coffea arabica and C canephora (Rubiaceae)Am J Bot 90 (2003) 153ndash157

[18] Roubik DW Ecology and natural history of tropical beesCambridge University Press New York 1989

[19] Heard AT Behaviour and pollinator efficiency of stinglessbees and honey bees on macadamia flowers J Apicul Res 33(1994) 191ndash198

[20] Brooks RW Roubik DW A halictine bee with distinctcastes Halictus hesperus and its bionomics in central PanamaSociobiol 7 (1983) 263ndash282

[21] Guzman M Rincoacuten-Rabnales M Vandame R Salvador MEfecto de las visitas de abejas en la produccioacuten de frutos derambutan in Quezada-Euan JJG May-Itza WJ Moo-ValleH Chab-Medina JC (Eds) II Seminario mexicano sobre abe-jas sin aguijoacuten Meacuterida 2001 pp 79ndash87

[22] DeJong TJ Waser NM Klinkhamer PGL Geitnogamy theneglected side of selfing Trends Ecol Evol 8 (1993) 328ndash335

[23] Vargas M Quesada P Caracterizacioacuten cualitativa y cuantitativade algunos genotipos de mamoacuten chino (Nephelium lappaceum)en la zona sur de Costa Rica Boltec 29 (1996) 41ndash49

[24] Zee FT Rambutan Purdue University Center for newcrops and plant productshttpwwwhortpurdueedunewcopcropfactsheetsRambutanhmtlz 1995

[25] FAO-STAT Situacioacuten actual y perspectivas a plazo mediopara los frutales tropicales Direccioacuten de Productos Baacutesicos yComercio FAO 2003

Cite this article as Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales David W Roubik Miguel A Guzmaacuten Miguel Salvador-Figueroa Lourdes Adriano-AnayaIsidro Ovando High yields and bee pollination of hermaphroditic rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L) in Chiapas Mexico Fruits 70 (2015)23ndash27

- Introduction

- Materials and methods

- Results and discussion

- Conclusion

- References

-

24 Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27

les fleurs de rambutan Conclusion Lrsquoespegravece drsquoabeille sans dard utiliseacutee tant dans des traitements de pollinisationouverte que sous cage a contribueacute agrave une augmentation proche de 10 fois la reacutecolte de fruits de cette varieacuteteacute de rambutanBien que la feacutecondation croiseacutee nrsquoait pas affecteacute la mise agrave fruit initiale par rapport agrave lrsquoautofeacutecondation un rendementsupeacuterieur a eacuteteacute obtenu en poids et en taille de fruits gracircce aux pollinisateurs sur fleurs en cage

Mots cleacutes Mexique Chiapas rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) animal pollinisateur abeilles autopollinisation

1 Introduction

Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L Sapindaceae) isa tropical plant that produces edible fruits and originatesfrom Malaysia and Indonesia According to FAO data thisfruit tree is being developed for commercial exploitationand the market is expanding rapidly Rambutan is nowa-days commercially grown in Southern Asia Australia theCaribbean India Sri Lanka Florida Hawaii and South andCentral America [1] However there is little information aboutits pollinators or insect flower visitors In nature rambu-tan plants are dioecious with about 50 male and 50hermaphrodite plants Therefore in commercial orchards onlyhermaphrodite plants are grown where most of them are func-tionally female For example in the Philippines the culti-vars ldquoMaharlikardquo and ldquoSeematjanrdquo produced about 9994and 9955 hermaphrodite functionally female flowers re-spectively [2] No functional pollen is supposed to be pro-duced by such andromonecious plants which is being ob-served in Australia where isolated trees with low functionalmale hermaphrodite flowers rarely set fruit satisfactorily [13]In Southeast Asia where rambutan is native cross pollinationby hand increases fruit set 13 times beyond the 1 found innatural conditions whereas bagged flowers fail to set fruits [3]Recent studies in India find the stingless bee Tetragonulairidipennis and Indian honeybee Apis cerana dominant for-agers on N lappaceum [4]

In our study region rambutan was introduced during1950minus1970 as an economic alternative to coffee mango orbanana and is now widely cultivated due to favorable agro-ecological conditions [5ndash7] Nonetheless few studies haveexamined the pollination system and insect visitors integralto a sound production technology We performed studies onpollen and fruit production in a commercially grown variety oframbutan in Chiapas Mexico by recording fruit yield pollendehiscence and viability flower visitors and pollinator man-agement in a commercial orchard with a fruit tree populationpreviously believed to be functionally female

2 Materials and methods

Our studies were performed on a commercial rambutan va-riety denominated ldquoCERI61rdquo by the Rosario Izapa experimentstation Mexican Institute of Forestry Agriculture and Live-stock Research In the Soconusco region rambutan varietiesintroduced from Malaysia and Indonesia were reproduced byseed and selected from plantations at this station In subse-quent plantings using grafted materials a genetic uniformitywas reached with smaller trees showing a good production andquality for marketing [5] The CER161 hermaphrodite varietywas studied in a 7 ha orchard of approximately 1000 trees

with no male individual trees flowering within the study areaor nearby This orchard at ldquoEl Herraderordquo ranch in the Metapade Dominguez municipality Chiapas Mexico (144948 N921132 W) is located at 100 m elevation Two flowering peri-ods were intensively studied each between January and Junein 2001 and 2002 Observations on fruit set (both initial andfinal) flower visitors and floral characteristics were repeatedin 2003ndash2004 The climate is hot and humid with abundantsummer rain [8 9] The habitat surrounding the orchard in-cludes orchards of mango (Mangifera indica L) Native sec-ondary vegetation commonly includes Ficus spp Tabebuiarosea (Bertol) DC Spondias mombin L S purpurea L Cy-bistax donnell-smithii (Rose) Seibert Tecoma stans (L) Jussex Kunth Ceiba pentandra (L) Gaertn and Pachira aquaticaAubl [9]

To determine the effects of flower visitors on the small(4 mm) apetalous and greenish flowers of rambutan ten treeswith six marked panicles were used for each of three experi-mental treatments The control treatment (T1) was open pol-lination without manipulation while (T2) excluded all visi-tors with a 1 mm mesh bag placed over the panicle in budstage (bagged flowers) The third treatment (T3) called ldquoin-duced pollinationrdquo was simultaneous with the other two Forthis we placed cages over trees with buds in the same stageas T1 and T2 and two bee colonies were placed at oppo-site ends of the 16 times 16 times 4 m cage The local stingless bees(Meliponini) in wooden hives were Scaptotrigona mexicanaGueacuterin-Meacutelenville and Tetragonisca angustula Lat whichmaintain colonies with approximately 1000 foragers They areconsidered as common flower visitors to rambutan in our re-gion From the marked panicles in each treatment final de-veloping fruits were scored and assessed at the time of com-mercial harvest In order to estimate the proportion of flowersproducing fruit total flowers were counted in bagged panicleson 10 trees

Flower visitors were sampled intensively from trees byplacing a large net-tent over an entire tree The net mesh was1 mm and the tent 3 m on each side An individual tree wascovered after which insects were collected in tubes contain-ing ethyl acetate Collections were made on separate trees at agiven hour between 7 am and 5 pm every 15 days from Febru-ary through March 2001 and from February through April2002 Bees and other insects were identified by using taxo-nomic keys of Ayala [10] and Michener [11]

3 Results and discussion

Initial fruit set differed nearly ten-fold among the threetreatments (ANOVA P lt 0001) Developing and mature fruitper flower were most abundant in the open pollination treat-ment in both years (Duncan and Tukey tests P lt 0001

Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27 25

Table I Fruits produced and fruit mass in three treatments on rambutan variety CERI61 induced pollination (bee colonies present in cage)open flowers and bagged flowers with no visitor at Metapa de Domiacutenguez Chiapas Mexico

TreatmentVariable Induced pollination Open pollination Bagged flowers

2001 2002 2001 2002 2001 2002

Set Fruit 764 plusmn 272B 714 plusmn 212B 968 plusmn 377A 1101 plusmn 462A 70 plusmn 80C 56 plusmn 39C

Mature Fruits 212 plusmn 61A 171 plusmn 65A 228 plusmn 93A 231 plusmn 79A 18 plusmn 32B 34 plusmn 33B

Fruit mass (g) 222 plusmn 21B 284 plusmn 32A 155 plusmn 06C 151 plusmn 03C 138 plusmn 05D 126 plusmn 07E

All treatments included a similar number of flowers (1 804 plusmn 503 in 2001 and 1 749 plusmn 545 in 2002 P lt 005) Data are means (plusmnstandarddeviation) of 10 biological replications Cells with the same letter in a given row are not significantly different (Tukey test α = 001)

Figure 1 Anther of Nephelium lappaceum from hermaphrodite flowers Left stamen with opened anther middle magnifications of anthersand right pollen grains

table I) but no statistical differences existed between inducedpollination (in cages) and open pollination The fruit mass wassignificantly greater in induced pollination treatments (table I)which also resulted in greater seed mass and fruit length (datanot shown) The open pollination treatment of 2001 and 2002registered the highest fruit set due to the larger number offlowers present on panicles (1 804 plusmn 503 and 1 749 plusmn 545 re-spectively) (table I) In contrast the bagged flowers treatmentregistered the lowest fruit set (table I)

Flowering began early in February and ended in Aprilreaching a maximum during March The effective flower-ing period was 30 plusmn 5 days All flowers on panicles werehermaphrodite and approximately 5 of them had pollen onanthers that dehisced and remained present upon stamens upto two days when the stamens wilted (figures 1 2)

Many developing fruit dropped during the first four weeksafter flowering with 50 lost and an additional 15 was lostby the seventh week By fruit maturity at 11 weeks little ad-ditional loss occurred With the introduction of stingless beehives on this ranch from 2000 to 2004 the average yield in-creased from 35 to 70 t haminus1

A total of 28186 individual bees were collected on flow-ers which represented 971 of the total insects taken inFebruaryndashMarch 2001 and FebruaryndashApril 2002 (table II)The peak insect visitation was observed between 10 am and11 am (468 and 416 in average respectively) Two bee fami-lies Apidae (Tetragonisca Trigona Oxytrigona Nannotrig-ona Apis Exomalopsis Paratetrapedia and Scaptotrigona)and Halictidae (Halictus) visited flowers first collecting asmall amount of pollen and nectar then collecting almost ex-clusively nectar after 10 am Visitors carried only small pollen

Figure 2 Scaptotrigona mexicana on a hermaphrodite flower oframbutan in the Soconusco region

loads on their hind legs When subjected to microscopic studypollen loads consisted of Asteraceae Euphorbiaceae and otherflowering plants common in the area Scaptotrigona mexi-cana dominated flowers during the end of flowering in MarchndashApril 2001 with 3512 individuals and 8164 of all collectedbees Halictus hesperus a social but not perennial bee domi-nated flowers in April 2001 after most flowering had occurredOur results agree with those Shivaramu et al [2] from In-dia reporting a stingless bee (T iridipennis) as a predominantforager

Rambutan produces hermaphrodite flowers that are tradi-tionally viewed as functionally pistillate [2] Recent studies inAsia indicate rambutan is a cross pollinated plant and dependson insects for pollination and fruit set [2] However Kiew [12]

26 Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27

Table II Richness and abundance of bees collected in two flowering periods in rambutan flowers at ldquoEl Herraderordquo ranch (Metapa deDomiacutenguez Chiapas Mexico)

Bee species February March April Total Relative abundance ()Apidae Apinae

Apis mellifera 3 1 1 5 002Apidae Apinae

Scaptotrigona mexicana 2840 4819 2063 9722 3449S pectoralis 58 49 16 123 044

T(Tetragonisca) angustula 659 171 23 853 302Nannotrigona pelilampoides 204 48 105 357 127Trigona fulviventris 21 21 12 54 019T nigerrima 27 8 3 38 013Oxitrigona mediorufa 43 ndash 2 45 016

Apidae AntophorinaeExomalopsis sp1 10 4 ndash 14 005Paratetrapedia sp1 1 2 ndash 3 005

HalictidaeHalictus hesperus 27 973 13675 14675 5207Lasioglossum sp1 4 98 1409 1511 536Lasioglossum sp2 ndash 57 555 612 217Lasioglossum sp3 15 15 127 157 056Agapostemon aff splendens 7 5 4 16 006Total of bees 3919 6271 17995 28185 10000

stated that rambutan is not bee pollinated but apomictic andparthenocarpic because hermaphrodite flowers do not releasepollen and male plants are not cultivated because they produceno fruit In contrast Nakasone and Paull [3] listing seven cul-tivars of rambutan used in Thailand Indonesia and Malaysiastated that even with no male trees present mixed plantingsgiven flowering synchrony provided acceptable yields Yieldsin plantings not meeting such conditions were exceedinglylow

Our data strongly suggest that hermaphroditic flowers canhave viable pollen which must be transferred by a pollinatorfor the production of mature fruit The pollen grains dehiscedand were fully formed (figure 1) on the anther surface in con-trast to deformed pollen found on functionally female but ap-parently hermaphroditic flowers in Decaspermum [13] In ad-dition pollen grains kept in a 20 sucrose solution initiatedpollen tube growth Both geitonogamy and outcrossing werepossible but there is no convincing evidence for apomixis inour rambutan variety because occasional autogamy cannot bediscounted The ldquoinduced pollinationrdquo treatment which couldonly result in geitonogamy produced significantly lower initialfruit set but equally abundant ripe fruit in both years comparedto the open pollination treatment (table I) In contrast the flow-ers caged to exclude all pollinators produced almost no fruitwhich is not a condition expected if apomixis occurred

The interpretation that fruit initiation was higher whensome outcrossing pollen was deposited on stigmata by beesis consistent with the initial fruit set but the yield in maturefruit could not reach that provided by full self pollination (ta-ble I) Any conceivable apomixis was greatly outweighed bygeitonogamy facilitated by pollinators

In some self-fertilizing plants fruit set may be stronglyincreased by the diversity and abundance of flower-visitingbees [14ndash16] For example commercial yield of Coffeaarabica increased 56 in open pollinated treatments opposed

to autogamous and bagged treatments [17] Our results agreewith these C arabica studies because rambutan flowers ex-posed to S mexicana produced 91 times more mature fruitsthan the treatment without pollinators The bees presumablyvisited many flowers to obtain a nectar load and are knownas group foragers [18] Small bees are generally thought tofavor pollination of small generalized flowers [19] MostScaptotrigona had gathered negligible nectar when sampled onflowers and Apis mellifera scutellata present on a few flowerswas not strongly attracted to rambutan although its flowers oc-cur in dense clusters on large panicles A small amount of floralnectar reward scramble competition or both likely discour-aged this honey bee from greater visitation despite an unusu-ally high sugar nectar reward gt50 by weight Although theHalictus nested in the ground near the orchard and in the gen-eral area [20] it also appeared at rambutan flowers in increasingfrequency when numbers increased in tent traps placed overtrees [21] This seasonal social bee was a significant visitorseen on the flowers and not merely flying into the traps Otherstudies also find numerous social bees visiting rambutan [3]The insignificant production of fruit in their absence indicatesthis plant depends on the action of small bees to stimulate fruitset and retention Since H hespersus was active only duringlate flowering season it was unable to provide much pollina-tion service in our studies

This is the first study of which we are aware in a plantdescribed as dioecious that implies selfed flowers gain greatermaternal investment in fruit than outcrossed flowers Althoughwe did not experimentally outcross and self flowers on thesame plant to test this conclusion we expect that our openpollination treatments included bees that transported pollenbetween compatible flowers If the orchard was essentially asingle self-fertile clone the outcrossing would have little ef-fect but fruit production in cages compared to open plantswould not be so large nor would fruit drop by potentially

Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27 27

outcrossed plants be relatively larger than that of strictly selfedplants In theory selfing should help to purge lethal alleles [22]and in natural conditions protogyny could offset the tendencyof geitonogamy to monopolize maternal resources The largeproportion of dehisced fruits suggests maternal discriminationbased upon fruit genotype

4 Conclusion

Fruit abundance for commercial rambutan is reported to be10 to 20 per panicle in Costa Rica [23] compared to 21 in thepresent study while fruit number in Malaysia is lower [24] Inthe latter study and in Chiapas fruit size was very similar Tothe producers of rambutan it is of special interest that the totalyield (weight of individual fruit multiplied by fruit retained perpanicle) was highest in the induced pollination treatment (incage) This implies that controlled production in greenhousewith pollinators can provide relatively high yields The yieldsat our Metapa orchard were over twice that of the leading pro-ducers (in Thailand) of Nephelium lappaceum [25] Thailandhas approximately the same number and size of stingless beespecies as Chiapas but also possesses five honey bee speciesIn both hemispheres increasing productivity through polli-nator management seems possible and desirable Because ofthe number and availability of pollinators and particularly themanagement of Scaptotrigona in our Chiapas site rambutanorchard pollination is likely to be efficient as well as economi-cally sound

Acknowledgements The authors thank the Instituto parael Desarrollo Sustentable en Mesoameacuterica AC (IDESMAC)for supporting thesis development (MAG) Ing Alfonso Espino fororchard facilities the students of Biotechnology at UNACH forfield assistance and G Nieto for electronic microscope imagesDWR acknowledges Baird fund support Smithsonian Institution Wethank Julieta Grajales-Conesa for her advice and support during thecorrection of the manuscript

References

[1] Sivakumar D Wijeratnam W Wijesundera R AbeyesekereM Control of postharvest diseases of rambutan using cin-namaldehyde Crop Prot 21 (2002) 847ndash852

[2] Tindall H Rambutan cultivation FAO Plant production andprotection paper 1994

[3] Nakasone HY Paull RE Tropical fruits CAB IntWallington UK 1998

[4] Shivaramu K Sakthivel T Rami-Reddy PV Diversityand foraging dynamics of insect pollinators on rambu-tan (Nephelium lappaceum L) Pest Manag Hort Ecosyst18 (2012) 158ndash160

[5] Vanderlinden EJM Pohlan AAJ Janssens MJJ Cultureand fruit quality of rambutaacuten (Nephelium lappaceum L) in theSoconusco region Chiapas Mexico Fruits 59 (2004) 339ndash350

[6] Perez RA El rambutaacuten en Mesoameacuterica gestacioacuten de una re-alidad empresarial Rev AgriCult 3 (2000) 35

[7] Kido S El estudio de desarrollo integral de agriculturaganaderiacutea y desarrollo rural de la regioacuten del Soconusco enChiapas JICA Mexico 1999

[8] Garcia E Modificaciones al sistema de clasificacioacuten climaacuteticade Koppen Universidad Nacional Autoacutenoma de Mexico 1973

[9] Rzedowski J Vegetacioacuten de Mexico Limusa Mexico 1978[10] Ayala R Revisioacuten de las abejas sin aguijoacuten de Meacutexico

(Hymenoptera Apidae Meliponini) Folia EntomoloacutegicaMexicana 106 (1999) 1ndash123

[11] Michener CD The bees of the world Johns Hopkins UnivPress Baltimore 2nd ed 2007

[12] Kiew R Bee botany in tropical Asia with special referenceto peninsular Malaysia in Kevan PG (Ed) The Asiatic hivebee apiculture biology and role in sustainable development intropical and subtropical Asia Enviroquest Cambridge Ontario1995 pp 117ndash124

[13] Kevan PG Lack AG Pollination in a cryptically dioeciousplant Decaspermum parviflora (Lam) A J Scott (Myrtaceae)by pollen-collecting bees in Sulawesi Indonesia Biol J LinnSoc 25 (1985) 319ndash330

[14] Heard AT The role of stingless bees in crop pollination AnnuRev Entomol 44 (1999) 183ndash206

[15] Richards AJ Does low biodiversity resulting from agriculturalpractice affect crop pollination and yield Ann Bot 88 (2001)165ndash172

[16] Roubik DW The value of bees to the coffee harvest Nature417 (2002) 708

[17] Klein AM Steffan-Dewenter I Tscharntke T Bee pollinationand fruit set of Coffea arabica and C canephora (Rubiaceae)Am J Bot 90 (2003) 153ndash157

[18] Roubik DW Ecology and natural history of tropical beesCambridge University Press New York 1989

[19] Heard AT Behaviour and pollinator efficiency of stinglessbees and honey bees on macadamia flowers J Apicul Res 33(1994) 191ndash198

[20] Brooks RW Roubik DW A halictine bee with distinctcastes Halictus hesperus and its bionomics in central PanamaSociobiol 7 (1983) 263ndash282

[21] Guzman M Rincoacuten-Rabnales M Vandame R Salvador MEfecto de las visitas de abejas en la produccioacuten de frutos derambutan in Quezada-Euan JJG May-Itza WJ Moo-ValleH Chab-Medina JC (Eds) II Seminario mexicano sobre abe-jas sin aguijoacuten Meacuterida 2001 pp 79ndash87

[22] DeJong TJ Waser NM Klinkhamer PGL Geitnogamy theneglected side of selfing Trends Ecol Evol 8 (1993) 328ndash335

[23] Vargas M Quesada P Caracterizacioacuten cualitativa y cuantitativade algunos genotipos de mamoacuten chino (Nephelium lappaceum)en la zona sur de Costa Rica Boltec 29 (1996) 41ndash49

[24] Zee FT Rambutan Purdue University Center for newcrops and plant productshttpwwwhortpurdueedunewcopcropfactsheetsRambutanhmtlz 1995

[25] FAO-STAT Situacioacuten actual y perspectivas a plazo mediopara los frutales tropicales Direccioacuten de Productos Baacutesicos yComercio FAO 2003

Cite this article as Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales David W Roubik Miguel A Guzmaacuten Miguel Salvador-Figueroa Lourdes Adriano-AnayaIsidro Ovando High yields and bee pollination of hermaphroditic rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L) in Chiapas Mexico Fruits 70 (2015)23ndash27

- Introduction

- Materials and methods

- Results and discussion

- Conclusion

- References

-

Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27 25

Table I Fruits produced and fruit mass in three treatments on rambutan variety CERI61 induced pollination (bee colonies present in cage)open flowers and bagged flowers with no visitor at Metapa de Domiacutenguez Chiapas Mexico

TreatmentVariable Induced pollination Open pollination Bagged flowers

2001 2002 2001 2002 2001 2002

Set Fruit 764 plusmn 272B 714 plusmn 212B 968 plusmn 377A 1101 plusmn 462A 70 plusmn 80C 56 plusmn 39C

Mature Fruits 212 plusmn 61A 171 plusmn 65A 228 plusmn 93A 231 plusmn 79A 18 plusmn 32B 34 plusmn 33B

Fruit mass (g) 222 plusmn 21B 284 plusmn 32A 155 plusmn 06C 151 plusmn 03C 138 plusmn 05D 126 plusmn 07E

All treatments included a similar number of flowers (1 804 plusmn 503 in 2001 and 1 749 plusmn 545 in 2002 P lt 005) Data are means (plusmnstandarddeviation) of 10 biological replications Cells with the same letter in a given row are not significantly different (Tukey test α = 001)

Figure 1 Anther of Nephelium lappaceum from hermaphrodite flowers Left stamen with opened anther middle magnifications of anthersand right pollen grains

table I) but no statistical differences existed between inducedpollination (in cages) and open pollination The fruit mass wassignificantly greater in induced pollination treatments (table I)which also resulted in greater seed mass and fruit length (datanot shown) The open pollination treatment of 2001 and 2002registered the highest fruit set due to the larger number offlowers present on panicles (1 804 plusmn 503 and 1 749 plusmn 545 re-spectively) (table I) In contrast the bagged flowers treatmentregistered the lowest fruit set (table I)

Flowering began early in February and ended in Aprilreaching a maximum during March The effective flower-ing period was 30 plusmn 5 days All flowers on panicles werehermaphrodite and approximately 5 of them had pollen onanthers that dehisced and remained present upon stamens upto two days when the stamens wilted (figures 1 2)

Many developing fruit dropped during the first four weeksafter flowering with 50 lost and an additional 15 was lostby the seventh week By fruit maturity at 11 weeks little ad-ditional loss occurred With the introduction of stingless beehives on this ranch from 2000 to 2004 the average yield in-creased from 35 to 70 t haminus1

A total of 28186 individual bees were collected on flow-ers which represented 971 of the total insects taken inFebruaryndashMarch 2001 and FebruaryndashApril 2002 (table II)The peak insect visitation was observed between 10 am and11 am (468 and 416 in average respectively) Two bee fami-lies Apidae (Tetragonisca Trigona Oxytrigona Nannotrig-ona Apis Exomalopsis Paratetrapedia and Scaptotrigona)and Halictidae (Halictus) visited flowers first collecting asmall amount of pollen and nectar then collecting almost ex-clusively nectar after 10 am Visitors carried only small pollen

Figure 2 Scaptotrigona mexicana on a hermaphrodite flower oframbutan in the Soconusco region

loads on their hind legs When subjected to microscopic studypollen loads consisted of Asteraceae Euphorbiaceae and otherflowering plants common in the area Scaptotrigona mexi-cana dominated flowers during the end of flowering in MarchndashApril 2001 with 3512 individuals and 8164 of all collectedbees Halictus hesperus a social but not perennial bee domi-nated flowers in April 2001 after most flowering had occurredOur results agree with those Shivaramu et al [2] from In-dia reporting a stingless bee (T iridipennis) as a predominantforager

Rambutan produces hermaphrodite flowers that are tradi-tionally viewed as functionally pistillate [2] Recent studies inAsia indicate rambutan is a cross pollinated plant and dependson insects for pollination and fruit set [2] However Kiew [12]

26 Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27

Table II Richness and abundance of bees collected in two flowering periods in rambutan flowers at ldquoEl Herraderordquo ranch (Metapa deDomiacutenguez Chiapas Mexico)

Bee species February March April Total Relative abundance ()Apidae Apinae

Apis mellifera 3 1 1 5 002Apidae Apinae

Scaptotrigona mexicana 2840 4819 2063 9722 3449S pectoralis 58 49 16 123 044

T(Tetragonisca) angustula 659 171 23 853 302Nannotrigona pelilampoides 204 48 105 357 127Trigona fulviventris 21 21 12 54 019T nigerrima 27 8 3 38 013Oxitrigona mediorufa 43 ndash 2 45 016

Apidae AntophorinaeExomalopsis sp1 10 4 ndash 14 005Paratetrapedia sp1 1 2 ndash 3 005

HalictidaeHalictus hesperus 27 973 13675 14675 5207Lasioglossum sp1 4 98 1409 1511 536Lasioglossum sp2 ndash 57 555 612 217Lasioglossum sp3 15 15 127 157 056Agapostemon aff splendens 7 5 4 16 006Total of bees 3919 6271 17995 28185 10000

stated that rambutan is not bee pollinated but apomictic andparthenocarpic because hermaphrodite flowers do not releasepollen and male plants are not cultivated because they produceno fruit In contrast Nakasone and Paull [3] listing seven cul-tivars of rambutan used in Thailand Indonesia and Malaysiastated that even with no male trees present mixed plantingsgiven flowering synchrony provided acceptable yields Yieldsin plantings not meeting such conditions were exceedinglylow

Our data strongly suggest that hermaphroditic flowers canhave viable pollen which must be transferred by a pollinatorfor the production of mature fruit The pollen grains dehiscedand were fully formed (figure 1) on the anther surface in con-trast to deformed pollen found on functionally female but ap-parently hermaphroditic flowers in Decaspermum [13] In ad-dition pollen grains kept in a 20 sucrose solution initiatedpollen tube growth Both geitonogamy and outcrossing werepossible but there is no convincing evidence for apomixis inour rambutan variety because occasional autogamy cannot bediscounted The ldquoinduced pollinationrdquo treatment which couldonly result in geitonogamy produced significantly lower initialfruit set but equally abundant ripe fruit in both years comparedto the open pollination treatment (table I) In contrast the flow-ers caged to exclude all pollinators produced almost no fruitwhich is not a condition expected if apomixis occurred

The interpretation that fruit initiation was higher whensome outcrossing pollen was deposited on stigmata by beesis consistent with the initial fruit set but the yield in maturefruit could not reach that provided by full self pollination (ta-ble I) Any conceivable apomixis was greatly outweighed bygeitonogamy facilitated by pollinators

In some self-fertilizing plants fruit set may be stronglyincreased by the diversity and abundance of flower-visitingbees [14ndash16] For example commercial yield of Coffeaarabica increased 56 in open pollinated treatments opposed

to autogamous and bagged treatments [17] Our results agreewith these C arabica studies because rambutan flowers ex-posed to S mexicana produced 91 times more mature fruitsthan the treatment without pollinators The bees presumablyvisited many flowers to obtain a nectar load and are knownas group foragers [18] Small bees are generally thought tofavor pollination of small generalized flowers [19] MostScaptotrigona had gathered negligible nectar when sampled onflowers and Apis mellifera scutellata present on a few flowerswas not strongly attracted to rambutan although its flowers oc-cur in dense clusters on large panicles A small amount of floralnectar reward scramble competition or both likely discour-aged this honey bee from greater visitation despite an unusu-ally high sugar nectar reward gt50 by weight Although theHalictus nested in the ground near the orchard and in the gen-eral area [20] it also appeared at rambutan flowers in increasingfrequency when numbers increased in tent traps placed overtrees [21] This seasonal social bee was a significant visitorseen on the flowers and not merely flying into the traps Otherstudies also find numerous social bees visiting rambutan [3]The insignificant production of fruit in their absence indicatesthis plant depends on the action of small bees to stimulate fruitset and retention Since H hespersus was active only duringlate flowering season it was unable to provide much pollina-tion service in our studies

This is the first study of which we are aware in a plantdescribed as dioecious that implies selfed flowers gain greatermaternal investment in fruit than outcrossed flowers Althoughwe did not experimentally outcross and self flowers on thesame plant to test this conclusion we expect that our openpollination treatments included bees that transported pollenbetween compatible flowers If the orchard was essentially asingle self-fertile clone the outcrossing would have little ef-fect but fruit production in cages compared to open plantswould not be so large nor would fruit drop by potentially

Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27 27

outcrossed plants be relatively larger than that of strictly selfedplants In theory selfing should help to purge lethal alleles [22]and in natural conditions protogyny could offset the tendencyof geitonogamy to monopolize maternal resources The largeproportion of dehisced fruits suggests maternal discriminationbased upon fruit genotype

4 Conclusion

Fruit abundance for commercial rambutan is reported to be10 to 20 per panicle in Costa Rica [23] compared to 21 in thepresent study while fruit number in Malaysia is lower [24] Inthe latter study and in Chiapas fruit size was very similar Tothe producers of rambutan it is of special interest that the totalyield (weight of individual fruit multiplied by fruit retained perpanicle) was highest in the induced pollination treatment (incage) This implies that controlled production in greenhousewith pollinators can provide relatively high yields The yieldsat our Metapa orchard were over twice that of the leading pro-ducers (in Thailand) of Nephelium lappaceum [25] Thailandhas approximately the same number and size of stingless beespecies as Chiapas but also possesses five honey bee speciesIn both hemispheres increasing productivity through polli-nator management seems possible and desirable Because ofthe number and availability of pollinators and particularly themanagement of Scaptotrigona in our Chiapas site rambutanorchard pollination is likely to be efficient as well as economi-cally sound

Acknowledgements The authors thank the Instituto parael Desarrollo Sustentable en Mesoameacuterica AC (IDESMAC)for supporting thesis development (MAG) Ing Alfonso Espino fororchard facilities the students of Biotechnology at UNACH forfield assistance and G Nieto for electronic microscope imagesDWR acknowledges Baird fund support Smithsonian Institution Wethank Julieta Grajales-Conesa for her advice and support during thecorrection of the manuscript

References

[1] Sivakumar D Wijeratnam W Wijesundera R AbeyesekereM Control of postharvest diseases of rambutan using cin-namaldehyde Crop Prot 21 (2002) 847ndash852

[2] Tindall H Rambutan cultivation FAO Plant production andprotection paper 1994

[3] Nakasone HY Paull RE Tropical fruits CAB IntWallington UK 1998

[4] Shivaramu K Sakthivel T Rami-Reddy PV Diversityand foraging dynamics of insect pollinators on rambu-tan (Nephelium lappaceum L) Pest Manag Hort Ecosyst18 (2012) 158ndash160

[5] Vanderlinden EJM Pohlan AAJ Janssens MJJ Cultureand fruit quality of rambutaacuten (Nephelium lappaceum L) in theSoconusco region Chiapas Mexico Fruits 59 (2004) 339ndash350

[6] Perez RA El rambutaacuten en Mesoameacuterica gestacioacuten de una re-alidad empresarial Rev AgriCult 3 (2000) 35

[7] Kido S El estudio de desarrollo integral de agriculturaganaderiacutea y desarrollo rural de la regioacuten del Soconusco enChiapas JICA Mexico 1999

[8] Garcia E Modificaciones al sistema de clasificacioacuten climaacuteticade Koppen Universidad Nacional Autoacutenoma de Mexico 1973

[9] Rzedowski J Vegetacioacuten de Mexico Limusa Mexico 1978[10] Ayala R Revisioacuten de las abejas sin aguijoacuten de Meacutexico

(Hymenoptera Apidae Meliponini) Folia EntomoloacutegicaMexicana 106 (1999) 1ndash123

[11] Michener CD The bees of the world Johns Hopkins UnivPress Baltimore 2nd ed 2007

[12] Kiew R Bee botany in tropical Asia with special referenceto peninsular Malaysia in Kevan PG (Ed) The Asiatic hivebee apiculture biology and role in sustainable development intropical and subtropical Asia Enviroquest Cambridge Ontario1995 pp 117ndash124

[13] Kevan PG Lack AG Pollination in a cryptically dioeciousplant Decaspermum parviflora (Lam) A J Scott (Myrtaceae)by pollen-collecting bees in Sulawesi Indonesia Biol J LinnSoc 25 (1985) 319ndash330

[14] Heard AT The role of stingless bees in crop pollination AnnuRev Entomol 44 (1999) 183ndash206

[15] Richards AJ Does low biodiversity resulting from agriculturalpractice affect crop pollination and yield Ann Bot 88 (2001)165ndash172

[16] Roubik DW The value of bees to the coffee harvest Nature417 (2002) 708

[17] Klein AM Steffan-Dewenter I Tscharntke T Bee pollinationand fruit set of Coffea arabica and C canephora (Rubiaceae)Am J Bot 90 (2003) 153ndash157

[18] Roubik DW Ecology and natural history of tropical beesCambridge University Press New York 1989

[19] Heard AT Behaviour and pollinator efficiency of stinglessbees and honey bees on macadamia flowers J Apicul Res 33(1994) 191ndash198

[20] Brooks RW Roubik DW A halictine bee with distinctcastes Halictus hesperus and its bionomics in central PanamaSociobiol 7 (1983) 263ndash282

[21] Guzman M Rincoacuten-Rabnales M Vandame R Salvador MEfecto de las visitas de abejas en la produccioacuten de frutos derambutan in Quezada-Euan JJG May-Itza WJ Moo-ValleH Chab-Medina JC (Eds) II Seminario mexicano sobre abe-jas sin aguijoacuten Meacuterida 2001 pp 79ndash87

[22] DeJong TJ Waser NM Klinkhamer PGL Geitnogamy theneglected side of selfing Trends Ecol Evol 8 (1993) 328ndash335

[23] Vargas M Quesada P Caracterizacioacuten cualitativa y cuantitativade algunos genotipos de mamoacuten chino (Nephelium lappaceum)en la zona sur de Costa Rica Boltec 29 (1996) 41ndash49

[24] Zee FT Rambutan Purdue University Center for newcrops and plant productshttpwwwhortpurdueedunewcopcropfactsheetsRambutanhmtlz 1995

[25] FAO-STAT Situacioacuten actual y perspectivas a plazo mediopara los frutales tropicales Direccioacuten de Productos Baacutesicos yComercio FAO 2003

Cite this article as Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales David W Roubik Miguel A Guzmaacuten Miguel Salvador-Figueroa Lourdes Adriano-AnayaIsidro Ovando High yields and bee pollination of hermaphroditic rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L) in Chiapas Mexico Fruits 70 (2015)23ndash27

- Introduction

- Materials and methods

- Results and discussion

- Conclusion

- References

-

26 Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27

Table II Richness and abundance of bees collected in two flowering periods in rambutan flowers at ldquoEl Herraderordquo ranch (Metapa deDomiacutenguez Chiapas Mexico)

Bee species February March April Total Relative abundance ()Apidae Apinae

Apis mellifera 3 1 1 5 002Apidae Apinae

Scaptotrigona mexicana 2840 4819 2063 9722 3449S pectoralis 58 49 16 123 044

T(Tetragonisca) angustula 659 171 23 853 302Nannotrigona pelilampoides 204 48 105 357 127Trigona fulviventris 21 21 12 54 019T nigerrima 27 8 3 38 013Oxitrigona mediorufa 43 ndash 2 45 016

Apidae AntophorinaeExomalopsis sp1 10 4 ndash 14 005Paratetrapedia sp1 1 2 ndash 3 005

HalictidaeHalictus hesperus 27 973 13675 14675 5207Lasioglossum sp1 4 98 1409 1511 536Lasioglossum sp2 ndash 57 555 612 217Lasioglossum sp3 15 15 127 157 056Agapostemon aff splendens 7 5 4 16 006Total of bees 3919 6271 17995 28185 10000

stated that rambutan is not bee pollinated but apomictic andparthenocarpic because hermaphrodite flowers do not releasepollen and male plants are not cultivated because they produceno fruit In contrast Nakasone and Paull [3] listing seven cul-tivars of rambutan used in Thailand Indonesia and Malaysiastated that even with no male trees present mixed plantingsgiven flowering synchrony provided acceptable yields Yieldsin plantings not meeting such conditions were exceedinglylow

Our data strongly suggest that hermaphroditic flowers canhave viable pollen which must be transferred by a pollinatorfor the production of mature fruit The pollen grains dehiscedand were fully formed (figure 1) on the anther surface in con-trast to deformed pollen found on functionally female but ap-parently hermaphroditic flowers in Decaspermum [13] In ad-dition pollen grains kept in a 20 sucrose solution initiatedpollen tube growth Both geitonogamy and outcrossing werepossible but there is no convincing evidence for apomixis inour rambutan variety because occasional autogamy cannot bediscounted The ldquoinduced pollinationrdquo treatment which couldonly result in geitonogamy produced significantly lower initialfruit set but equally abundant ripe fruit in both years comparedto the open pollination treatment (table I) In contrast the flow-ers caged to exclude all pollinators produced almost no fruitwhich is not a condition expected if apomixis occurred

The interpretation that fruit initiation was higher whensome outcrossing pollen was deposited on stigmata by beesis consistent with the initial fruit set but the yield in maturefruit could not reach that provided by full self pollination (ta-ble I) Any conceivable apomixis was greatly outweighed bygeitonogamy facilitated by pollinators

In some self-fertilizing plants fruit set may be stronglyincreased by the diversity and abundance of flower-visitingbees [14ndash16] For example commercial yield of Coffeaarabica increased 56 in open pollinated treatments opposed

to autogamous and bagged treatments [17] Our results agreewith these C arabica studies because rambutan flowers ex-posed to S mexicana produced 91 times more mature fruitsthan the treatment without pollinators The bees presumablyvisited many flowers to obtain a nectar load and are knownas group foragers [18] Small bees are generally thought tofavor pollination of small generalized flowers [19] MostScaptotrigona had gathered negligible nectar when sampled onflowers and Apis mellifera scutellata present on a few flowerswas not strongly attracted to rambutan although its flowers oc-cur in dense clusters on large panicles A small amount of floralnectar reward scramble competition or both likely discour-aged this honey bee from greater visitation despite an unusu-ally high sugar nectar reward gt50 by weight Although theHalictus nested in the ground near the orchard and in the gen-eral area [20] it also appeared at rambutan flowers in increasingfrequency when numbers increased in tent traps placed overtrees [21] This seasonal social bee was a significant visitorseen on the flowers and not merely flying into the traps Otherstudies also find numerous social bees visiting rambutan [3]The insignificant production of fruit in their absence indicatesthis plant depends on the action of small bees to stimulate fruitset and retention Since H hespersus was active only duringlate flowering season it was unable to provide much pollina-tion service in our studies

This is the first study of which we are aware in a plantdescribed as dioecious that implies selfed flowers gain greatermaternal investment in fruit than outcrossed flowers Althoughwe did not experimentally outcross and self flowers on thesame plant to test this conclusion we expect that our openpollination treatments included bees that transported pollenbetween compatible flowers If the orchard was essentially asingle self-fertile clone the outcrossing would have little ef-fect but fruit production in cages compared to open plantswould not be so large nor would fruit drop by potentially

Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27 27

outcrossed plants be relatively larger than that of strictly selfedplants In theory selfing should help to purge lethal alleles [22]and in natural conditions protogyny could offset the tendencyof geitonogamy to monopolize maternal resources The largeproportion of dehisced fruits suggests maternal discriminationbased upon fruit genotype

4 Conclusion

Fruit abundance for commercial rambutan is reported to be10 to 20 per panicle in Costa Rica [23] compared to 21 in thepresent study while fruit number in Malaysia is lower [24] Inthe latter study and in Chiapas fruit size was very similar Tothe producers of rambutan it is of special interest that the totalyield (weight of individual fruit multiplied by fruit retained perpanicle) was highest in the induced pollination treatment (incage) This implies that controlled production in greenhousewith pollinators can provide relatively high yields The yieldsat our Metapa orchard were over twice that of the leading pro-ducers (in Thailand) of Nephelium lappaceum [25] Thailandhas approximately the same number and size of stingless beespecies as Chiapas but also possesses five honey bee speciesIn both hemispheres increasing productivity through polli-nator management seems possible and desirable Because ofthe number and availability of pollinators and particularly themanagement of Scaptotrigona in our Chiapas site rambutanorchard pollination is likely to be efficient as well as economi-cally sound

Acknowledgements The authors thank the Instituto parael Desarrollo Sustentable en Mesoameacuterica AC (IDESMAC)for supporting thesis development (MAG) Ing Alfonso Espino fororchard facilities the students of Biotechnology at UNACH forfield assistance and G Nieto for electronic microscope imagesDWR acknowledges Baird fund support Smithsonian Institution Wethank Julieta Grajales-Conesa for her advice and support during thecorrection of the manuscript

References

[1] Sivakumar D Wijeratnam W Wijesundera R AbeyesekereM Control of postharvest diseases of rambutan using cin-namaldehyde Crop Prot 21 (2002) 847ndash852

[2] Tindall H Rambutan cultivation FAO Plant production andprotection paper 1994

[3] Nakasone HY Paull RE Tropical fruits CAB IntWallington UK 1998

[4] Shivaramu K Sakthivel T Rami-Reddy PV Diversityand foraging dynamics of insect pollinators on rambu-tan (Nephelium lappaceum L) Pest Manag Hort Ecosyst18 (2012) 158ndash160

[5] Vanderlinden EJM Pohlan AAJ Janssens MJJ Cultureand fruit quality of rambutaacuten (Nephelium lappaceum L) in theSoconusco region Chiapas Mexico Fruits 59 (2004) 339ndash350

[6] Perez RA El rambutaacuten en Mesoameacuterica gestacioacuten de una re-alidad empresarial Rev AgriCult 3 (2000) 35

[7] Kido S El estudio de desarrollo integral de agriculturaganaderiacutea y desarrollo rural de la regioacuten del Soconusco enChiapas JICA Mexico 1999

[8] Garcia E Modificaciones al sistema de clasificacioacuten climaacuteticade Koppen Universidad Nacional Autoacutenoma de Mexico 1973

[9] Rzedowski J Vegetacioacuten de Mexico Limusa Mexico 1978[10] Ayala R Revisioacuten de las abejas sin aguijoacuten de Meacutexico

(Hymenoptera Apidae Meliponini) Folia EntomoloacutegicaMexicana 106 (1999) 1ndash123

[11] Michener CD The bees of the world Johns Hopkins UnivPress Baltimore 2nd ed 2007

[12] Kiew R Bee botany in tropical Asia with special referenceto peninsular Malaysia in Kevan PG (Ed) The Asiatic hivebee apiculture biology and role in sustainable development intropical and subtropical Asia Enviroquest Cambridge Ontario1995 pp 117ndash124

[13] Kevan PG Lack AG Pollination in a cryptically dioeciousplant Decaspermum parviflora (Lam) A J Scott (Myrtaceae)by pollen-collecting bees in Sulawesi Indonesia Biol J LinnSoc 25 (1985) 319ndash330

[14] Heard AT The role of stingless bees in crop pollination AnnuRev Entomol 44 (1999) 183ndash206

[15] Richards AJ Does low biodiversity resulting from agriculturalpractice affect crop pollination and yield Ann Bot 88 (2001)165ndash172

[16] Roubik DW The value of bees to the coffee harvest Nature417 (2002) 708

[17] Klein AM Steffan-Dewenter I Tscharntke T Bee pollinationand fruit set of Coffea arabica and C canephora (Rubiaceae)Am J Bot 90 (2003) 153ndash157

[18] Roubik DW Ecology and natural history of tropical beesCambridge University Press New York 1989

[19] Heard AT Behaviour and pollinator efficiency of stinglessbees and honey bees on macadamia flowers J Apicul Res 33(1994) 191ndash198

[20] Brooks RW Roubik DW A halictine bee with distinctcastes Halictus hesperus and its bionomics in central PanamaSociobiol 7 (1983) 263ndash282

[21] Guzman M Rincoacuten-Rabnales M Vandame R Salvador MEfecto de las visitas de abejas en la produccioacuten de frutos derambutan in Quezada-Euan JJG May-Itza WJ Moo-ValleH Chab-Medina JC (Eds) II Seminario mexicano sobre abe-jas sin aguijoacuten Meacuterida 2001 pp 79ndash87

[22] DeJong TJ Waser NM Klinkhamer PGL Geitnogamy theneglected side of selfing Trends Ecol Evol 8 (1993) 328ndash335

[23] Vargas M Quesada P Caracterizacioacuten cualitativa y cuantitativade algunos genotipos de mamoacuten chino (Nephelium lappaceum)en la zona sur de Costa Rica Boltec 29 (1996) 41ndash49

[24] Zee FT Rambutan Purdue University Center for newcrops and plant productshttpwwwhortpurdueedunewcopcropfactsheetsRambutanhmtlz 1995

[25] FAO-STAT Situacioacuten actual y perspectivas a plazo mediopara los frutales tropicales Direccioacuten de Productos Baacutesicos yComercio FAO 2003

Cite this article as Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales David W Roubik Miguel A Guzmaacuten Miguel Salvador-Figueroa Lourdes Adriano-AnayaIsidro Ovando High yields and bee pollination of hermaphroditic rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L) in Chiapas Mexico Fruits 70 (2015)23ndash27

- Introduction

- Materials and methods

- Results and discussion

- Conclusion

- References

-

Manuel Rincoacuten-Rabanales et al Fruits 70 (2015) 23ndash27 27

outcrossed plants be relatively larger than that of strictly selfedplants In theory selfing should help to purge lethal alleles [22]and in natural conditions protogyny could offset the tendencyof geitonogamy to monopolize maternal resources The largeproportion of dehisced fruits suggests maternal discriminationbased upon fruit genotype

4 Conclusion

Fruit abundance for commercial rambutan is reported to be10 to 20 per panicle in Costa Rica [23] compared to 21 in thepresent study while fruit number in Malaysia is lower [24] Inthe latter study and in Chiapas fruit size was very similar Tothe producers of rambutan it is of special interest that the totalyield (weight of individual fruit multiplied by fruit retained perpanicle) was highest in the induced pollination treatment (incage) This implies that controlled production in greenhousewith pollinators can provide relatively high yields The yieldsat our Metapa orchard were over twice that of the leading pro-ducers (in Thailand) of Nephelium lappaceum [25] Thailandhas approximately the same number and size of stingless beespecies as Chiapas but also possesses five honey bee speciesIn both hemispheres increasing productivity through polli-nator management seems possible and desirable Because ofthe number and availability of pollinators and particularly themanagement of Scaptotrigona in our Chiapas site rambutanorchard pollination is likely to be efficient as well as economi-cally sound

Acknowledgements The authors thank the Instituto parael Desarrollo Sustentable en Mesoameacuterica AC (IDESMAC)for supporting thesis development (MAG) Ing Alfonso Espino fororchard facilities the students of Biotechnology at UNACH forfield assistance and G Nieto for electronic microscope imagesDWR acknowledges Baird fund support Smithsonian Institution Wethank Julieta Grajales-Conesa for her advice and support during thecorrection of the manuscript

References

[1] Sivakumar D Wijeratnam W Wijesundera R AbeyesekereM Control of postharvest diseases of rambutan using cin-namaldehyde Crop Prot 21 (2002) 847ndash852

[2] Tindall H Rambutan cultivation FAO Plant production andprotection paper 1994

[3] Nakasone HY Paull RE Tropical fruits CAB IntWallington UK 1998

[4] Shivaramu K Sakthivel T Rami-Reddy PV Diversityand foraging dynamics of insect pollinators on rambu-tan (Nephelium lappaceum L) Pest Manag Hort Ecosyst18 (2012) 158ndash160

[5] Vanderlinden EJM Pohlan AAJ Janssens MJJ Cultureand fruit quality of rambutaacuten (Nephelium lappaceum L) in theSoconusco region Chiapas Mexico Fruits 59 (2004) 339ndash350

[6] Perez RA El rambutaacuten en Mesoameacuterica gestacioacuten de una re-alidad empresarial Rev AgriCult 3 (2000) 35

[7] Kido S El estudio de desarrollo integral de agriculturaganaderiacutea y desarrollo rural de la regioacuten del Soconusco enChiapas JICA Mexico 1999

[8] Garcia E Modificaciones al sistema de clasificacioacuten climaacuteticade Koppen Universidad Nacional Autoacutenoma de Mexico 1973

[9] Rzedowski J Vegetacioacuten de Mexico Limusa Mexico 1978[10] Ayala R Revisioacuten de las abejas sin aguijoacuten de Meacutexico

(Hymenoptera Apidae Meliponini) Folia EntomoloacutegicaMexicana 106 (1999) 1ndash123

[11] Michener CD The bees of the world Johns Hopkins UnivPress Baltimore 2nd ed 2007

[12] Kiew R Bee botany in tropical Asia with special referenceto peninsular Malaysia in Kevan PG (Ed) The Asiatic hivebee apiculture biology and role in sustainable development intropical and subtropical Asia Enviroquest Cambridge Ontario1995 pp 117ndash124

[13] Kevan PG Lack AG Pollination in a cryptically dioeciousplant Decaspermum parviflora (Lam) A J Scott (Myrtaceae)by pollen-collecting bees in Sulawesi Indonesia Biol J LinnSoc 25 (1985) 319ndash330

[14] Heard AT The role of stingless bees in crop pollination AnnuRev Entomol 44 (1999) 183ndash206

[15] Richards AJ Does low biodiversity resulting from agriculturalpractice affect crop pollination and yield Ann Bot 88 (2001)165ndash172

[16] Roubik DW The value of bees to the coffee harvest Nature417 (2002) 708

[17] Klein AM Steffan-Dewenter I Tscharntke T Bee pollinationand fruit set of Coffea arabica and C canephora (Rubiaceae)Am J Bot 90 (2003) 153ndash157

[18] Roubik DW Ecology and natural history of tropical beesCambridge University Press New York 1989

[19] Heard AT Behaviour and pollinator efficiency of stinglessbees and honey bees on macadamia flowers J Apicul Res 33(1994) 191ndash198

[20] Brooks RW Roubik DW A halictine bee with distinctcastes Halictus hesperus and its bionomics in central PanamaSociobiol 7 (1983) 263ndash282

[21] Guzman M Rincoacuten-Rabnales M Vandame R Salvador MEfecto de las visitas de abejas en la produccioacuten de frutos derambutan in Quezada-Euan JJG May-Itza WJ Moo-ValleH Chab-Medina JC (Eds) II Seminario mexicano sobre abe-jas sin aguijoacuten Meacuterida 2001 pp 79ndash87

[22] DeJong TJ Waser NM Klinkhamer PGL Geitnogamy theneglected side of selfing Trends Ecol Evol 8 (1993) 328ndash335

[23] Vargas M Quesada P Caracterizacioacuten cualitativa y cuantitativade algunos genotipos de mamoacuten chino (Nephelium lappaceum)en la zona sur de Costa Rica Boltec 29 (1996) 41ndash49

[24] Zee FT Rambutan Purdue University Center for newcrops and plant productshttpwwwhortpurdueedunewcopcropfactsheetsRambutanhmtlz 1995

[25] FAO-STAT Situacioacuten actual y perspectivas a plazo mediopara los frutales tropicales Direccioacuten de Productos Baacutesicos yComercio FAO 2003