HERBARIUM AND ITS USE-DEEPAK YADAV alld. university.UP

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

deepak-yadav-dee-pee -

Category

Education

-

view

215 -

download

1

description

Transcript of HERBARIUM AND ITS USE-DEEPAK YADAV alld. university.UP

Herbarium and its importance

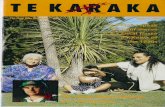

Herbarium specimens of various Nepenthes at the Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris,

France

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) – sometimes known by the Anglicized term herbar – is a

collection of preserved plant specimens. These specimens may be whole plants or plant parts:

these will usually be in a dried form mounted on a sheet but, depending upon the material, may

also be kept in alcohol or other preservative. The same term is often used in mycology to

describe an equivalent collection of preserved fungi, otherwise known as a fungarium.

The term can also refer to the building where the specimens are stored or to the scientific

institute that not only stores but researches these specimens. The specimens in a herbarium are

often used as reference material in describing plant taxa; some specimens may be types.

A xylarium is a herbarium specialising in specimens of wood. A hortorium (as in the Liberty

Hyde Bailey Hortorium) is one specialising in preserved specimens of cultivated plants.

Specimen preservation

Preparing a plant for mounting

To preserve their form and color, plants collected in the field are spread flat on sheets of

newsprint and dried, usually in a plant press, between blotters or absorbent paper. The

specimens, which are then mounted on sheets of stiff white paper, are labeled with all essential

data, such as date and place found, description of the plant, altitude, and special habitat

conditions. The sheet is then placed in a protective case. As a precaution against insect attack,

the pressed plant is frozen or poisoned, and the case disinfected.

Certain groups of plants are soft, bulky, or otherwise not amenable to drying and mounting on

sheets. For these plants, other methods of preparation and storage may be used. For example,

conifer cones and palm fronds may be stored in labeled boxes. Representative flowers or fruits

may be pickled in formaldehyde to preserve their three-dimensional structure. Small specimens,

such as mosses and lichens, are often air-dried and packaged in small paper envelopes.

No matter the method of preservation, detailed information on where and when the plant was

collected, habitat, color (since it may fade over time), and the name of the collector is usually

included.

Collections management

A large herbarium may have hundreds of cases filled with specimens.

Most herbaria utilize a standard system of organizing their specimens into herbarium cases.

Specimen sheets are stacked in groups by the species to which they belong and placed into a

large lightweight folder that is labelled on the bottom edge. Groups of species folders are then

placed together into larger, heavier folders by genus. The genus folders are then sorted by

taxonomic family according to the standard system selected for use by the herbarium and placed

into pigeonholes in herbarium cabinets.

Locating a specimen filed in the herbarium requires knowing the nomenclature and classification

used by the herbarium. It also requires familiarity with possible name changes that have occurred

since the specimen was collected, since the specimen may be filed under an older name.

Modern herbaria often maintain electronic databases of their collections. Many herbaria have

initiatives to digitize specimens to produce a virtual herbarium. These records and images are

made publicly accessible via the Internet when possible.

Uses

Herbaria are essential for the study of plant taxonomy, the study of geographic distributions, and

the stabilizing of nomenclature. Thus, it is desirable to include in a specimen as much of the

plant as possible (e.g., flowers, stems, leaves, seed, and fruit). Linnaeus's herbarium now belongs

to the Linnean Society in England.

Specimens housed in herbaria may be used to catalogue or identify the flora of an area. A large

collection from a single area is used in writing a field guide or manual to aid in the identification

of plants that grow there. With more specimens available, the author of the guide will better

understand the variability of form in the plants and the natural distribution over which the plants

grow.

Herbaria also preserve a historical record of change in vegetation over time. In some cases,

plants become extinct in one area or may become extinct altogether. In such cases, specimens

preserved in an herbarium can represent the only record of the plant's original distribution.

Environmental scientists make use of such data to track changes in climate and human impact.

Many kinds of scientists use herbaria to preserve voucher specimens, representative samples of

plants used in a particular study to demonstrate precisely the source of their data.

They may also be a repository of viable seeds for rare species.[1]

Largest herbaria

The Swedish Museum of Natural History (S)

Many universities, museums, and botanical gardens maintain herbaria.

Herbaria have also proven very useful as sources of plant DNA for use in taxonomy and

molecular systematics. The largest herbaria in the world, in approximate order of decreasing size,

are:

1Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (P) (Paris, France)

2New York Botanical Garden (NY) (Bronx, New York, USA)

3Komarov Botanical Institute (LE) (St. Petersburg, Russia)

4Royal Botanic Gardens (K) (Kew, England, UK)

5Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de la Ville de Genève (G) (Geneva, Switzerland)

6Missouri Botanical Garden (MO) (St. Louis, Missouri, USA)

7British Museum of Natural History (BM) (London, England, UK)

8Harvard University (HUH) (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA)

9Museum of Natural History of Vienna (W) (Vienna, Austria)

10Swedish Museum of Natural History (S) (Stockholm, Sweden)

11United States National Herbarium (Smithsonian Institution) (US) (Washington, DC,

USA)

12Nationaal Herbarium Nederland (L) (Leiden, Netherlands)

13Université Montpellier (MPU) (Montpellier, France)

14Université Claude Bernard (LY) (Villeurbane Cedex, France)

15Herbarium Universitatis Florentinae (FI) (Florence, Italy)

16National Botanic Garden of Belgium (BR) (Meise, Belgium)

17University of Helsinki (H) (Helsinki, Finland)

18Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem, Zentraleinrichtung der

Freien Universität Berlin (B) (Berlin, Germany)

19The Field Museum (F) (Chicago, Illinois, USA)

20University of Copenhagen (C) (Copenhagen, Denmark)

21Chinese National Herbarium, (Chinese Academy of Sciences) (PE) (Beijing, People's

Republic of China)

22University and Jepson Herbaria (UC/JEPS) (Berkeley, California, USA)

23Herbarium Bogoriense (BO) (Bogor, West Java, Indonesia)

24Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh (E) (Edinburgh, Scotland, UK)

25Herbarium Hamburgense (HBG) (Hamburg, Germany)

The importance of herbaria.

The sheets from herbaria have more than taxonomic import. They have been used to look at

aspects of physiological ecology. As mentioned ‘overleaf’, specimens taken from from the

Cambridge herbarium have been used to examine how stomatal frequency has changed over the

last 150 years.

The leaves of native trees in South East England now have 40% less stomatal pores than those

collected at the turn of the Nineteenth Century. This seems to be a response to changing levels of

carbon dioxide.

Detailed records and maps of the distribution of species over time can also be valuable in

understanding how our flora is changing, the impact of invasive species and the possible effects

of changing climate.

One such invasive species is the leaf miner moth (Cameraria ohridella) that affects Horse

Chestnut trees. The ‘progress’ of the horse chestnut leaf miner has been reported on the web

from summer 2006 to more recently, when a national survey was under way. This small, but

highly efficient parasitic moth was first ‘discovered’ in trees bordering Lake Ohrid in Macedonia

in 1986. It was described as species new to Europe, and has since managed to spread across

almost all of Europe.

There has been a debate as to whether the moth

was an ‘introduction’ – from an area like south east Asia, or

whether it was a parasite that had changed its host – perhaps from sycamore or maple

trees.

However, work on ‘historical’ herbarium sheets of horse chestnuts from various institutions

across Europe have established that the larvae of the moth were present in foliage dating back to

1879. These early specimens were collected in Greece – a century before the moths were

suspected to be present in Europe! DNA analyses of the archival DNA of various specimens

indicate that the moth has its origins in the Balkans – effectively quashing the introduced species

and host switch hypotheses.

The studies of this moth by David Lees (an expert on moths and butterflies at the Natural

History Museum and the National Institute for Agricultural Research, France) and H Walter

Lack (Botanic Garden and Museum, Berlin) demonstrate the relevance and importance of

herbaria (both local and national) in studying plant – insect interactions, historical distributions

of plants and their parasites, and the origins of invasive species. The leaf miner probably

existed for centuries in remote valleys in the Balkans (‘home’ of the horse chestnut), but with the

development of roads / transport – the moth was able to ‘escape’ and spread.*

In a similar way to tracking of the horse chestnut leaf miner, so analysis of archival DNA from

64 specimens from 11 different herbaria has helped clarify the origins of the ‘European

potato’. Potatoes appeared in Europe in 1567 (Canary Isles) from South America and soon

spread world wide, and across Europe.

In England, the potato began to be used more widely as a crop when it received (in 1662) an

endorsement from the Royal Society, which suggested that the planting of potatoes would help

prevent / offset famine. There have been two main hypotheses as to the geographical origin of

the European potato; one holds that it came from the Andes whereas the other suggests a lowland

Chilean origin.

Analysis of the material (which dates from circa 1600 to 1910) from the various herbaria

indicates that the Andean potato was grown into the 1700’s, but the Chilean form came to

dominate in early C19th (through further introductions).

The paper by Ames and Spooner (American Journal of Botany, 2008, 95(2): p 252- 257) is

another demonstration of the importance of herbaria and their specimens in terms of the analysis

of the origin of our modern crops and their various cultivars.

Professor David Mabberley, former keeper * of the Herbarium, Library, Art and Archives at

Kew said in a recent interview: “The purpose [of a herbarium] is as a record of plants, in

particular places, at particular times.” Herbaria enable scientists to create a map (in time and

space) of the genetic distribution of plant material across the world, allowing them at times to

reconstitute damaged ecosystems; and sometimes find relatives of ‘staple crops’ that have

disease resistance.