Harp Music of The Italian Renaissance (Andrew Lawrence-King).

-

Upload

abhi-sharma -

Category

Documents

-

view

202 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Harp Music of The Italian Renaissance (Andrew Lawrence-King).

TRABACI . NEGRI . MAYONE . FILLIMARINO . CACCINI

Harp music of the

ITALIAN RENAISSANCE

ANDREW LAWRENCE-KING

arpa doppia

2

LIKE MOST INSTRUMENTS, the harp has become louder, larger and more mechanical asit has developed from simple medieval instruments with a dozen or fewer strings to themodern, five-and-a-half-octave, double-action pedal harp. The massive increase in

tension associated with the complex (and heavy) mechanism for altering the pitch of thestrings makes the modern concert harp as different from its Baroque predecessors as thepiano is from the harpsichord.

The twenty-five-string ‘Gothic’ harp was played throughout the Renaissance but around themiddle of the sixteenth century extra strings were added, making the instrument fullychromatic. The theorist Vincenzo Galilei (father of the astronomer) described the ‘arpa doppia’(double harp with twice the usual number of strings) in his Dialogue on Music (1581): thestrings were arranged in two parallel rows, corresponding to the white and black keys of akeyboard; the rows exchanged function halfway up the instrument so that each hand had thediatonic (white-note) row conveniently placed; the ‘black notes’ were played by poking afinger between two strings in the main row to reach a chromatic string beyond. In this way theharp was capable of extreme chromaticism long before the invention of pedals, although (likeall early instruments) it was easier to play in ‘normal’ keys, close to C major, where most ofthe notes would lie in the main row of strings.

For the same reason as the chitarrone was developed from the Renaissance lute, so harpswere made larger and provided with additional bass strings in order to play basso continuo.By around 1600 the ‘arpa doppia’ was ‘double’ not only because it had two rows of stringsbut also because it was very large and had a low-bass register (as in ‘double’ bass or‘double’ bassoon). The string-length was much increased but the tension was still relativelylow since the whole frame, having no rigid metal mechanism encumbering it, was light andfree to resonate.

Like the chitarrone, the ‘arpa doppia’ was primarily an accompanying instrument. Its powerfulbass made it ideal for early-Baroque continuo, and it combined the flexibility and tonal paletteof the theorbo with the compass of a keyboard. Many seventeenth-century title pagessuggest the harp as an alternative to lute or keyboard accompaniment, and writers such asPraetorius and Agazzari included the harp in their instructions on playing continuo.

The harp, unlike the lute or harpsichord, did not have a large amateur following to create amarket for published solo music. Nevertheless there were a number of virtuosi who achievedinternational fame for their mastery of the ‘arpa doppia’. In Rome, Orazio Michi wasconsidered second only to Frescobaldi as a musician, and unrivalled as a harpist. Histechnique of damping the strings to prevent the aural chaos caused by the harp’s long

3

resonance was particularly important. The Neapolitan school of composers associated withMacque included Trabaci and Mayone (harpists), Luigi Rossi (whose wife and brother bothplayed the instrument) and Rinaldo dall’Arpa (an employee of Gesualdo).

The harp and the lute had long been associated with love songs and dance music, and theseventeenth-century virtuosi were famous for ornamented transcriptions of well-knownmadrigals. An account of a young Sicilian girl playing ‘the most beautiful and artificial piecesby the most famous composers’ describes how she ‘ran quickly from the highest strings tothe lowest’ and played ‘with such pleasant and artful little scales and fugues’. (Her harp wasapparently so large that she had to stand on a chair in order to tune it.)

Dramatic arpeggios across the whole compass of the harp became a cliché, especially as anopening device. Composers also exploited the chromatic potential of the instrument and itscapacity for turns, trills and echoes, as recommended by Agazzari and Praetorius. There is afamous solo for the ‘arpa doppia’ in Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo, and keyboard publicationsby Trabaci and Mayone include pieces specifically designated for the harp (‘per l’arpa’). Thereis also a hidden repertoire of pieces written by harpists which, although not actually marked‘per l’arpa’, seems to be conceived in terms of the harp. Intervals too wide for the keyboard,trills arranged to suit the tuning of the ‘arpa doppia’ and similarity to known harp pieces aresome of the clues to such compositions. In any case, Renaissance sources unanimouslyagree on the suitability of keyboard and lute music for the harp, not to mention thewidespread practice of taking over repertoire from any other instrument.

Most of the music of this recording is Neapolitan, reflecting Naples’ importance as the centreof Italian harp-playing. Much of it is by Giovanni Maria Trabaci, singer, harpist and (withAscanio Mayone) organist at the Spanish Chapel Royal in Naples. His 1615 book Il secondolibro de ricercate & altri varij capricci was published shortly after he succeeded Macque asmaestro di capella.

The Toccata Seconda & Ligature (track 1) is a tour de force of idiomatic harp writing with itsdramatic opening, marked chromaticism and typically Neapolitan variety of texture.Ancidetemi pur 3 is a virtuoso transcription of a plain four-part madrigal by Arcadelt. Theoriginal lines are scarcely recognizable beneath Trabaci’s ornaments and divisions, withscales, trills and echoes just as described by Agazzari. In his Partite sopra Zefiro 5 , Trabacimarks the second, eighth, ninth and eleventh variations ‘per l’arpa’. The tenth is marked ‘condue fughe’, and the last partita has two parts ‘in canone senza regola’. Although thegalliards 2 4 6 , like the harp pieces, are printed in score, Trabaci says that they could alsobe played by an ensemble of viols or violins. He does not limit himself to the strict galliardmeasure, but alternates sections in dance rhythm with imitative writing.

Cesare Negri’s dance manual Le Gratie d’Amore presents its tunes (mostly very simple) inboth staff notation and lute tablature, so that all kinds of instruments could provide music forthe dancers. In addition to a large number of short dances and balletti, there are a few large-scale pieces with a developed musical structure. La Barriera 7 is a choreographedtournament, culminating in a mock battle, whereas Brando per Quattro Pastore e QuattroNinfe 9 evokes an idealized pastoral world through a medley of Renaissance tunes (includinga galliard version of So ben mi ch’a buon tempo).

Vergine Bella 8 is another transcription of a vocal original, in this case a devotional madrigal,or ‘lauda’, by the Mantuan composer Bartolomeo Tromboncino. The restrained divisions leaveintact the polyphony and the form of the original with its closing ‘Amen’.

Ascanio Mayone’s Toccata Prima bl is in the same Neapolitan style of extreme contrasts asthat of his colleague Trabaci: a style that was to find its culmination in the madrigals ofGesualdo. The Gagliarda Prima bm comes from a Neapolitan manuscript which includes musicby Trabaci, Macque and Gesualdo. Fabrizio Fillimarino was a lutenist in Gesualdo’s academy,and the sour chromatics of his opening motif add a distinctly Neapolitan touch to the CanzonCromatica bn . This piece is found in a manuscript copied by the composer Luigi Rossi forMacque, his teacher.

Rome, where the brilliant Orazio Michi played for Cardinal Montalto, is represented by thepresent author’s own transcription of Amarilli mia bella bo (surely one of the ‘most beautifuland artificial pieces’) in the ornate style of seventeenth-century harp playing. Giuliano Caccini,sometimes referred to as ‘Giulio Romano’, studied in Rome as a singer, lute player andharpist before entering into service at the Medici court in Florence.

ANDREW LAWRENCE-KING © 1987

If you have enjoyed this recording perhaps you would like a catalogue listing the many others available on the Hyperion andHelios labels. If so, please write to Hyperion Records Ltd, PO Box 25, London SE9 1AX, England, or email us [email protected], and we will be pleased to post you one free of charge.

The Hyperion catalogue can also be accessed on the Internet at www.hyperion-records.co.uk

4

Musique pour harpe de la Renaissance italienne

COMME LA PLUPART DES INSTRUMENTS, la harpe a, au gré de son évolution, gagnéen sonorité, en taille et en mécanisme, passant des instruments médiévaux simples,qui ne dépassaient pas la douzaine de cordes, à la harpe à double mouvement

moderne (cinq octaves et demie). Par l’accroissement massif de la tension et par l’adjonctiond’un mécanisme complexe (et lourd) destiné à modifier la hauteur de son des cordes, laharpe de concert moderne est à la harpe baroque ce que le piano est au clavecin.

Vers le milieu du XVIIe siècle, la harpe « gothique » à vingt-cinq cordes, qui avait eu cours toutau long de la Renaissance, reçut des cordes supplémentaires pour devenir entièrementchromatique. Dans son Dialogue sur la musique (1581), le théoricien Vincenzo Galilei (le pèrede l’astronome) décrivit la « arpa doppia », une harpe double tendue du double des cordeshabituelles : les deux rangées de cordes parallèles, correspondant aux touches noires etblanches d’un clavier, changeaient de fonction à mi-hauteur de l’instrument, en sorte que chaquemain avait la rangée diatonique (notes blanches) commodément placée ; quant aux « notesnoires », elles étaient jouées en passant un doigt entre deux cordes de la rangée principalepour atteindre une corde chromatique. Ainsi la harpe était-elle capable d’un chromatismeextrême bien avant l’invention des pédales, même s’il était tout de même plus facile (et celavaut pour tous les instruments anciens) de jouer dans les tonalités « normales », proches d’utmajeur, là où la plupart des notes étaient accessibles dans la rangée de cordes principale.

Tout comme le luth renaissant évolua en chitarrone, la harpe fut agrandie et dotée de cordesgraves supplémentaires pour jouer le bass continuo. Vers 1600, la « arpa doppia » était doubleà plus d’un titre : pourvue de deux rangées de cordes, elle était très imposante et disposaitd’un registre grave-basse (cf. la terminologie anglaise de la contrebasse ou du contrebasson,qui parle de « double » bass et de « double » bassoon). Nonobstant une longueur de cordesfort accrue, la tension demeura relativement faible, l’ensemble du cadre, dépourvu de toutmécanisme métallique rigide et encombrant, s’avérant léger et libre de résonner.

Comme le chitarrone, la « arpa doppia » était avant tout un instrument d’accompagnement.Sa basse puissante en fit l’instrument idéal du continuo du début de l’ère baroque, uninstrument qui alliait la flexibilité et la palette tonale du théorbe à l’ambitus d’un clavier.Maintes pages de titre du XVIIe siècle suggèrent un possible remplacement (pourl’accompagnement) du luth ou du clavier par la harpe, harpe que des auteurs commePraetorius ou Agazzari inclurent dans leurs instructions relatives à l’exécution du continuo.

Contrairement au luth ou au clavecin, la harpe ne disposait pas d’un nombre d’adeptesamateurs suffisant pour créer un marché de l’édition de pièces solistes. Ce qui n’empêchapas un certain nombre de virtuoses d’atteindre à une renommée internationale grâce à leur

5

maîtrise de la « arpa doppia ». À Rome, Orazio Michi arrivait juste derrière Frescobaldi commemusicien et était sans rival comme harpiste. Sa technique d’étouffement des cordes pourempêcher le chaos auditif né de la longue résonance de la harpe fut particulièrementimportante. Parmi les compositeurs de l’école napolitaine liée à Macque, citons Trabaci etMayone (harpistes), Luigi Rossi (dont la femme et le frère étaient également harpistes) etRinaldo dall’Arpa (un employé de Gesualdo).

La harpe et le luth ont longtemps été associés aux chants d’amour et à la musique de danse,et les virtuoses du XVIIe siècle étaient réputés pour leurs transcriptions, ornées, de madrigauxcélèbres. Un récit évoquant une jeune Sicilienne jouant « les pièces les plus belles et les plusciselées des plus fameux compositeurs » décrit la manière dont elle « passait prestement descordes les plus aiguës aux plus graves » et dont elle interprétait « avec un art si agréable lespetites gammes et les fugues ». (Sa harpe était manifestement si grande qu’il lui fallait se tenirsur une chaise pour l’accorder.)

Les arpèges spectaculaires, embrassant tout l’ambitus de la harpe, sont devenus un lieucommun, surtout en ouverture. Les compositeurs ont également exploité le potentielchromatique de l’instrument et son aptitude aux doubles, aux trilles et aux échos,conformément aux recommandations d’Agazzari et de Praetorius. L’Orfeo de Monteverdirecèle ainsi un fameux solo pour la « arpa doppia », cependant que les publications pourclavier de Trabaci et de Mayone offrent des pièces spécifiquement conçues pour la harpe(« per l’arpa »). À cela s’ajoute tout un répertoire caché de pièces écrites par des harpistes etqui, pour n’être pas marquées explicitement « per l’arpa », n’en semblent pas moins avoir étéconçues en pensant à la harpe. Intervalles trop larges pour le clavier, trilles adaptés à l’accordde la « arpa doppia », similitudes avec des pièces pour harpe connues : tels sont certains desindices caractéristiques de ce genre de compositions. Quoi qu’il en soit, les sources de laRenaissance s’accordent toutes à reconnaître combien la musique pour clavier et pour luthconvient à la harpe, sans parler de la pratique, largement répandue, qui consistait àreprendre le répertoire de n’importe quel autre instrument.

La plupart des œuvres de cet enregistrement sont napolitaines – reflet de l’importance deNaples comme centre du jeu de harpe italien – et, pour beaucoup, de Giovanni Maria Trabaci,chanteur, harpiste et (avec Ascanio Mayone) organiste à la chapelle royale d’Espagne àNaples. Son livre Il secondo libro de ricercate & altri varij capricci parut en 1615, peu aprèsqu’il eut succédé à Macque au poste de maestro di capella.

La Toccata Seconda & Ligature 1 est un tour de force d’écriture pour harpe idiomatique,comme l’attestent son ouverture théâtrale, son chromatisme appuyé et sa diversité de texturetypiquement napolitaine. Transcription virtuose d’un madrigal simple, à quatre parties,

6

d’Arcadelt, Ancidetemi pur 3 masque presque entièrement les lignes originales sous lesornements et les divisions de Trabaci, dont les gammes, les trilles et les échos sontconformes aux descriptions d’Agazzari. Dans ses Partite sopra Zefiro 5 , Trabaci marque lesdeuxième, huitième, neuvième et onzième variations « per l’arpa », la dixième étant spécifiée« con due fughe » et la dernière présentant deux parties « in canone senza regola ». Bienqu’imprimées en forme de partition comme les pièces pour harpe, les gaillardes 2 4 6

pourraient, selon Trabaci, tout autant être interprétées par un ensemble de violes ou deviolons. Loin de se borner à la stricte mesure de gaillarde, Trabaci fait alterner des sectionsen rythme de danse avec une écriture imitative.

Le manuel de danse de Cesare Negri, Le Gratie d’Amore, présente ses mélodies (fortsimples, pour la plupart) notées en portées et en tablature de luth, si bien que toutes sortesd’instruments pouvaient fournir de la musique aux danseurs. Un grand nombre de dansescourtes et de balletti côtoient quelques pièces à grande échelle, dotées d’une structuremusicale développée. La Barriera 7 est un tournoi chorégraphié qui culmine en un simulacrede bataille, tandis que Brando per Quattro Pastore e Quattro Ninfe 9 évoque un mondepastoral idéalisé à travers un pot-pourri d’airs renaissants (dont une version sous forme degaillarde de So ben mi ch’a buon tempo).

Autre transcription d’un original vocal, Vergine Bella 8 reprend un madrigal dévotionnel(ou « lauda ») du compositeur mantouan Bartolomeo Tromboncino et parvient, avec sesdivisions tout en retenue, à préserver la polyphonie et la forme originelles, y comprisl’« Amen » conclusif.

La Toccata Prima bl d’Ascanio Mayone reprend le style napolitain, tout en contrastesextrêmes, de la Toccata de son collègue Trabaci – un style qui devait trouver son apogéedans les madrigaux de Gesualdo. La Gagliarda Prima bm provient d’un manuscrit napolitainrenfermant des œuvres de Trabaci, Macque et Gesualdo. Quant à Fabrizio Fillimarino, luthisteà l’académie de Gesualdo, les aigres chromatismes de son motif d’ouverture apportent unetouche typiquement napolitaine à la Canzon Cromatica bn , qui figure dans un manuscrit copiépar le compositeur Luigi Rossi pour son professeur, Macque.

Rome, où le brillant Orazio Michi jouait pour le cardinal Montalto, est représentée ici par latranscription, due au présent auteur, d’Amarilli mia bella bo (assurément l’une des « pièces lesplus belles et les plus ciselées ») dans le style orné propre au jeu de harpe du XVIIe siècle.Giuliano Caccini, alias « Giulio Romano », étudia à Rome le chant, le luth et la harpe avant deprendre ses fonctions à la cour des Médicis, à Florence.

ANDREW LAWRENCE-KING © 1987Traduction HYPERION 2004

7

Harfenmusik der italienischen Renaissance

WIE DIE MEISTEN ANDEREN MUSIKINSTRUMENTE ist die Harfe im Zuge ihrerEntwicklung vom schlichten mittelalterlichen Instrument mit einem Dutzend (odernoch weniger) Saiten zur modernen Doppelpedalharfe mit einem Tonumfang von

fünfeinhalb Oktaven lauter, größer und mechanisierter geworden. Die massive Zunahme anSaitenspannung, die mit dem komplexen (und schweren) Mechanismus zur Veränderung derTonhöhe einzelner Saiten verbunden ist, unterscheidet die moderne Konzertharfe von ihrenbarocken Vorgängern in ebensolchem Maße, wie sich das heutige Klavier vom Cembaloabhebt.

Die fünfundzwanzigsaitige „gotische“ Harfe kam über die ganze Epoche der Renaissancehinweg zum Einsatz, aber um die Mitte des sechzehnten Jahrhunderts wurden weitere Saitenhinzugefügt, die das Instrument vollständig chromatisch spielbar machten. Der TheoretikerVincenzo Galilei (der Vater des Himmelsforschers) beschrieb in seinem Dialogo della musicaantica, et della moderna von 1581 die „arpa doppia“ (eine Doppelharfe mit zweimal sovielenSaiten wie damals üblich): Die Saiten waren in zwei parallelen Reihen angeordnet,entsprechend den weißen und schwarzen Tasten des Klaviers; auf halbem Weg derBespannung wechselten die Reihen ihre Funktion, so dass die diatonische Reihe (der„weißen“ Töne) für jede Hand gut erreichbar lag; die „schwarzen“ Töne wurden gespielt,indem man einen Finger zwischen zwei Saiten der Hauptreihe hindurch steckte, um diedahinter liegende chromatische Saite zu erreichen. So wurde die Harfe lange vor derErfindung von Pedalen zu extremer Chromatik befähigt, obwohl es (wie bei allen frühenInstrumenten) stets einfacher war, in „normalen“ Tonarten nahe bei C-Dur zu spielen, in denendie meisten Noten in der Hauptreihe der Saiten zu finden waren.

Aus dem gleichen Grund, der aus der Renaissance-Laute den Chitarrone entstehen ließ,wurden Harfen vergrößert und mit zusätzlichen Basssaiten versehen, um Basso continuospielen zu können. Etwa um 1600 wurde die „arpa doppia“ zu einem besonders großenInstrument mit tiefem Bassregister („doppelt“ entsprechend dem „double bass“ oder „doublebassoon“, wie Kontrabass bzw. Kontrafagott im Englischen bis heute heißen). Die Saitenwurden erheblich verlängert, doch blieb ihre Spannung relativ gering, da der ganze leichteRahmen, den kein rigider Metallmechanismus belastete, frei mitschwingen konnte.

Wie der Chitarrone wurde auch die „arpa doppia“ in erster Linie als Begleitinstrumenteingesetzt. Durch ihren kräftigen Bass eignete sie sich ideal zum Generalbassspiel desFrühbarock, verband sie doch die Flexibilität und Klangpalette der Theorbe mit demTonumfang eines Tasteninstruments. Viele Titelblätter von Musikpublikationen des

8

siebzehnten Jahrhunderts schlagen die Harfe als Alternative zur Begleitung durch Laute oderTasteninstrument vor, und Autoren wie Praetorius und Agazzari schlossen die Harfe in ihreAnweisungen zum Basso-continuo-Spiel ein.

Im Gegensatz zur Laute oder dem Cembalo genoss die Harfe keine große Beliebtheit unterAmateurmusikern, die einen Markt für veröffentlichte Solowerke hätten schaffen können.Nichtsdestoweniger gab es eine Anzahl von Virtuosen, die ob ihrer meisterhaftenBeherrschung der „arpa doppia“ zu internationalem Ruhm gelangten. In Rom konnte sichOrazio Michi als Musiker sogar mit Frescobaldi messen und galt als unübertrefflicherHarfenist. Von besonderer Bedeutung war seine Technik des Saitendämpfens, mit der sichdas aus der langen Nachhallzeit der Harfe resultierende akustische Chaos verhindern ließ.Zur neapolitanischen Komponistenschule, die man mit Giovanni de Macque verbindet,gehörten die Harfenisten Giovanni Trabaci und Ascanio Mayone, außerdem Luigi Rossi(dessen Frau und Bruder beide das Instrument beherrschten) sowie Rinaldo dall’Arpa (der imDienste von Don Carlo Gesualdo stand).

Harfe und Laute verband man seit langem mit Liebesliedern und Tanzmusik, und dieVirtuosen des siebzehnten Jahrhunderts waren für ihre reich verzierten Transkriptionenbekannter Madrigale berühmt. Ein Bericht beschreibt eine junge Sizilianerin, die „dieschönsten und kunstvollsten Stücke der bekanntesten Komponisten“ spielte, dabei „raschvon den höchsten zu den tiefsten Saiten wechselte“ und „ausnehmend erfreuliche undraffinierte kleine Skalen und Fugen“ ausführte. (Ihre Harfe war anscheinend so groß, dass sieauf einen Stuhl klettern musste, um sie zu stimmen.)

Dramatische Arpeggien über den ganzen Tonumfang der Harfe wurden zum Klischee,insbesondere als Eröffnungskunstgriff. Komponisten nutzten auch gern das chromatischePotential des Instruments und seine Eignung für Doppelschläge, Triller und Echoeffekte, wiesie von Agazzari und Praetorius empfohlen wurden. In Monteverdis Oper L’Orfeo findet sichein berühmtes Solo für „arpa doppia“, und Veröffentlichungen mit Tastenmusik von Trabaciund Mayone enthalten Stücke, die ausdrücklich für Harfe gedacht sind („per l’arpa“).Daneben gibt es ein gewissermaßen verborgenes Repertoire von Stücken, die ihre Harfespielenden Urheber zwar nicht ausdrücklich „per l’arpa“ designierten, doch anscheinend imHinblick auf die Harfe konzipierten. Intervalle, die für Tasteninstrumente zu groß sind, Triller,die auf die Stimmung der „arpa doppia“ zugeschnitten zu sein scheinen, und Ähnlichkeitenmit bekannten Harfenwerken liefern Hinweise auf solche Kompositionen. Überhaupt sind sichdie Quellen aus der Renaissance darüber einig, dass Tasten- und Lautenmusik für die Harfegeeignet ist – ganz zu schweigen von der insgesamt weit verbreiteten Praxis, das Repertoireanderer Instrumente zu übernehmen.

9

Der größte Teil der hier eingespielten Musik stammt aus Neapel, was die Bedeutung der Stadtals Zentrum des Harfenspiels in Italien widerspiegelt. Viele der Werke sind von Giovanni MariaTrabaci, der als Sänger, Harfenist und (zusammen mit Ascanio Mayone) als Organist an derköniglichen Kapelle des spanischen Hofs zu Neapel tätig war. Sein 1615 gedruckter BandIl secondo libro de ricercate & altri varij capricci erschien kurz nach seiner Ernennung zummaestro di capella in der Nachfolge von Macque.

Die Toccata Seconda & Ligature (Nr. 1) ist mit ihrer dramatischen Eröffnung, derhervorstechenden Chromatik und dem für Neapel typischen strukturellen Abwechslungs-reichtum eine Glanzleistung idiomatischer Harfenkomposition. Ancidetemi pur 3 ist dievirtuose Transkription eines schlichten vierstimmigen Madrigals von Arcadelt. Die Original-stimmen sind unter Trabacis Verzierungen und Diminutionen mit ihren Skalen, Trillern undEchos (ganz im Sinne von Agazzari) kaum noch zu erkennen. In seiner Partite sopra Zefiro 5

versieht Trabaci die zweite, achte, neunte und elfte Variation mit der Anweisung „per l’arpa“.Bei der zehnten steht „con due fughe“, und die letzte Partita hat zwei Stimmen „in canonesenza regola“. Obwohl die Gaillarden 2 4 6 wie die Harfenstücke in Partitur gedruckt sind,merkt Trabaci dazu an, sie seien auch von einem Gamben- oder Violinensemble zu spielen.Er beschränkt sich nicht auf den strengen Gaillardentakt, sondern wechselt Abschnitte imTanzrhythmus mit imitativer Stimmführung ab.

Cesare Negris Tanzanleitung Le Gratie d’Amore notiert ihre (meist sehr einfachen) Melodiensowohl in Liniensystemen als auch in Lautentabulatur, so dass verschiedenste Arten vonInstrumenten den Tänzern ihre Musik liefern konnten. Neben einer großen Anzahl von kurzenTänzen und balletti finden sich einige größer angelegte Stücke mit ausgearbeitetermusikalischer Struktur. La Barriera 7 ist ein choreographiertes Turnier, dessen Höhepunkt einScheinkampf bildet, wohingegen Brando per Quattro Pastore e Quattro Ninfe 9 durch einPotpourri von Renaissance-Melodien (darunter eine Fassung von So ben mi ch’a buon tempoin Gaillardenform) eine idealisierte pastorale Welt heraufbeschwört.

Vergine Bella 8 ist eine weitere Transkription eines ursprünglich für Gesang bestimmtenStücks – in diesem Fall eines Erbauungsmadrigals („lauda“) des mantuanischen KomponistenBartolomeo Tromboncino. Die gemäßigten Diminutionen lassen die Polyphonie und die Formder Vorlage mit ihrem abschließenden „Amen“ intakt.

Ascanio Mayones Toccata Prima bl ist im gleichen neapolitanischen Stil extremer Kontrastegehalten wie die seines Kollegen Trabaci: Dieser Stil sollte seine höchste Ausprägung inden Madrigalen von Gesualdo erfahren. Die Gagliarda Prima bm stammt aus einemneapolitanischen Manuskript, das Musik von Trabaci, Macque und Gesualdo enthält. FabrizioFillimarino war Lautenist in Gesualdos Accademia, und die bittere Chromatik seines

10

einleitenden Motivs verleiht dem Canzon Cromatica bn einen ausgesprochen neapolitanischenKlang. Dieses Werk ist einem Manuskript entnommen, das von dem Komponisten Luigi Rossifür seinen Lehrer Macque kopiert wurde.

Rom, wo der brillante Orazio Michi dem Kardinal Montalto aufspielte, ist hier vertreten durcheine Transkription, die der Autor der vorliegenden Anmerkungen von Amarilli mia bella bo imreich ausgeschmückten Stil der Harfenisten des siebzehnten Jahrhunderts vorgenommen hat(es handelt sich dabei mit Sicherheit um eines der bewussten „schönsten und kunstvollstenStücke“). Giuliano Caccini, auch bekannt als „Giulio Romano“, wurde in Rom als Sänger,Lautenist und Harfenist ausgebildet, ehe er in Florenz in den Dienst des Medici-Hofs trat.

ANDREW LAWRENCE-KING © 1987Übersetzung ANNE STEEB/BERND MÜLLER 2004

Also available:THE HARP OF LUDUVICO

Fantasias, Arias and Toccatas by Frescobaldi and his predecessorsANDREW LAWRENCE-KING baroque harps

Compact Disc CDH55264GRAMOPHONE CRITICS’ CHOICE

‘This is a quite stunning record. Treat yourself to it, even if it means pawning something you can live without’ (Gramophone) ‘This is a stunning record’ (Fanfare, USA)

11

Copyright subsists in all Hyperion recordings and it is illegal to copy them, in whole or in part, for any purpose whatsoever, withoutpermission from the copyright holder, Hyperion Records Ltd, PO Box 25, London SE9 1AX, England. Any unauthorized copying orre-recording, broadcasting, or public performance of this or any other Hyperion recording will constitute an infringement ofcopyright. Applications for a public performance licence should be sent to Phonographic Performance Ltd, 1 Upper James Street,London W1F 9DE

CDH55162

Harp music of theITALIAN RENAISSANCE

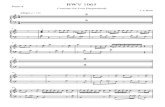

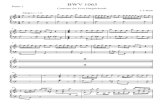

1 Toccata Seconda & Ligature GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [2'46]

2 Gagliarda Terza a 4, detta la Talianella GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [2'13]

3 Ancidetemi pur GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [7'12]

4 Gagliarda Terza a 5, sopra La Mantoana GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [3'25]

5 Partite sopra Zefiro GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [10'50]

6 Gagliarda Quarta, alla Spagnola GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [4'20]

7 La Barriera CESARE NEGRI (c1536– fl1604) [4'08]

8 Vergine Bella ANONYMOUS (1517) [2'37]

9 Brando per Quattro Pastore e Quattro Ninfe CESARE NEGRI (c1536– fl1604) [5'32]

bl Toccata Prima ASCANIO MAYONE (c1565–1627) [5'03]

bm Gagliarda Prima ANONYMOUS (early seventeenth century) [2'42]

bn Canzon Cromatica FABRIZIO FILLIMARINO (fl1594) [4'03]

bo Amarilli mia bella GIULIANO CACCINI (1546–1618) [3'18]

ANDREW LAWRENCE-KINGarpa doppia

Recorded on 26–27 August 1986Arpa doppia made in London by MARTIN HAYCOCK

Recording Engineer ANTONY HOWELLRecording Producer MARK BROWN

Front Design TERRY SHANNONExecutive Producer EDWARD PERRY

P Hyperion Records Limited, London, 1987C Hyperion Records Limited, London, 2004(Originally issued on Hyperion CDA66229)

Front illustration: The Allegory of Music by Giovanni Lanfranco (1582–1647)showing the ‘Barbarini’ harp which still exists in the Barbarini Palace, Rome,

with whose permission this picture is reproduced (photograph by Arauco Orellana)

HELIO

SC

DH

5516

2H

ELIO

SC

DH

5516

2 HA

RP M

USIC

OF T

HE ITA

LIAN

REN

AISSA

NC

EA

ND

REW LA

WREN

CE-K

ING

HA

RP

MU

SIC

OF

TH

E IT

ALI

AN

REN

AIS

SAN

CE

AN

DRE

W L

AW

REN

CE-

KIN

G

Harp music of theITALIAN RENAISSANCE

1 Toccata Seconda & Ligature GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [2'46]

2 Gagliarda Terza a 4, detta la Talianella GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [2'13]

3 Ancidetemi pur GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [7'12]

4 Gagliarda Terza a 5, sopra La Mantoana GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [3'25]

5 Partite sopra Zefiro GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [10'50]

6 Gagliarda Quarta, alla Spagnola GIOVANNI MARIA TRABACI (1575–1647) [4'20]

7 La Barriera CESARE NEGRI (c1536– fl1604) [4'08]

8 Vergine Bella ANONYMOUS (1517) [2'37]

9 Brando per Quattro Pastore e Quattro Ninfe CESARE NEGRI (c1536– fl1604) [5'32]

bl Toccata Prima ASCANIO MAYONE (c1565–1627) [5'03]

bm Gagliarda Prima ANONYMOUS (early seventeenth century) [2'42]

bn Canzon Cromatica FABRIZIO FILLIMARINO (fl1594) [4'03]

bo Amarilli mia bella GIULIANO CACCINI (1546–1618) [3'18]

ANDREW LAWRENCE-KINGarpa doppia

MADE IN ENGLAND

CDH55162Duration 60'03

A HYPERION RECORDING

DDD

Recorded on 26–27 August 1986Recording Engineer ANTONY HOWELL

Recording Producer MARK BROWNFront Design TERRY SHANNON

Executive Producer EDWARD PERRYP Hyperion Records Limited, London, 1987C Hyperion Records Limited, London, 2004(Originally issued on Hyperion CDA66229)

Front illustration: The Allegory of Music by Giovanni Lanfranco (1582– 1647)

‘An impressive debut, beautifully recorded’(Gramophone)

NOTES EN FRANÇAIS + MIT DEUTSCHEM KOMMENTAR