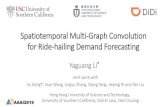

Hailing the Future: Expanding the availability of wheelchair accessible taxicabs in Massachusetts

description

Transcript of Hailing the Future: Expanding the availability of wheelchair accessible taxicabs in Massachusetts

-

Hailing the Future: Expanding the availability of

wheelchair accessible taxicabs

in Massachusetts

Law Office 9

Northeastern University School of Law

Legal Skills in Social Context

Social Justice Program

In conjunction with:

The Disability Policy Consortium

-

ii

-

iii

Law Office 9

March, 11 2013

Nichole Clarke Marion Johnston Evan Segal

Kassondra Dart Atenas Madico Nathaniel Spinney

Ryan Dobens Devin Morse Leah Tedesco

Kelly Elder Laila Nabi Kaitlyn Thomas

Shaun Robinson, Fall Lawyering Fellow

Dana Antenucci, Spring Lawyering Fellow

Alfreda Russell, Senior Law Librarian

Josh Abrams, Advising Attorney

Professor Susan Maze-Rothstein, Faculty Supervisor

-

iv

-

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8

I. INTRODUCTION 11

A. MBTA LIMITATIONS: THE RIDE

B. TRANSPORTATION ISSUES AND THE ELDERLY

12

17

II. LITIGATION UNDER THE ADA 19

A. TITLE II: PROHIBITION OF THE DISCRIMINATION BY PUBLIC

ENTITIES

21

1. Subtitle A: Taxicab Regulatory Bodies as Public Entities

2. Recent Litigation of Subtitle A: Noel v. New York City Taxi and

Limousine Commission

3. Subtitle A: Arguments Applied to Massachusetts

4. Subtitle B: Public Entities Which Provide Public Transportation

22

23

25

28

B. TITLE III: PROHIBITION OF DISCRIMINATION BY A PLACE OF

PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION

30

1. Public Accommodations 31

2. Public Accommodation under Massachusetts Law 35

3. Section 12184: Specified Public Transportation Services Provided by

Private Entities

36

a. Parts (b)(3) & (5) 36

b. Parts (b)(1) & (2) 38

III. MASSACHUSETTS STATUTORY AND REGULATORY OVERVIEW 42

IV. MASSACHUSETTS MUNICIPAL ORDINANCE CASE STUDY 47

-

vi

A. MUNICIPAL OBLIGATIONS UNDER FEDERAL AND STATE LAW

B. MUNICIPAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND COMPLIANCE WITH THE

ADA

47

49

1. Positive Municipal Advancements in Wheelchair Accessible Taxicab

Service

54

a. Boston

b. Brookline

c. Cambridge

d. Conclusion

55

59

61

64

2. Municipalities in Need of Further Development 66

a. Worcester 67

b. Somerville 68

c. Sudbury 69

d. Springfield 71

e. Pittsfield area 72

f. Hyannis area 73

g. Conclusion 74

V. CASE STUDIES OF UNITED STATES MUNICIPALITIES 76

A. FUNDING 76

B. CASE STUDIES 80

1. Chicago, IL 80

2. Rhode Island 84

3. New Haven, CT 87

4. Washington, D.C. 89

-

vii

5. Arlington, VA 92

C. CONCLUSION 94

VI. IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES 97

A. NON-TRADITIONAL FUNDING SOURCES FOR ACCESSIBLE

TAXICABS

97

1. Department of Energy

2. Green Technology Tax Incentives

3. Conclusion

99

100

101

B. SUMMARY OR STRATEGIES

101

Appendix A BUDGETING 103

Appendix B CONTACTS 108

Appendix C CLAIMS UNDER 12184(b)(1) and (b)(2) 109

Appendix D CITIES 120

-

8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

An integral component of the transportation infrastructure in many communities is

taxicab service. For many people, taxicabs provide the essential link between home,

employment and the community at large. However, for persons in a wheelchair, this may not be

a mobility option unless accessible taxi services are available. The Americans with Disabilities

Act (ADA), a federal statute, was enacted in 1990 to eliminate discrimination based on a

persons disability. While the ADA prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability, little has

been done around the issue of wheelchair accessible taxicab service. Through the ADA, persons

with disabilities have gained an opportunity to address structural problems they encounter in the

able-bodied world. Specifically, the ADA has been used to reform various aspects of interaction

between persons with disabilities and transportation. Although the ADA specifically exempts

automobiles, which includes most taxicabs, from accessibility requirements, there exist potential

routes to ensure taxicabs provide accommodation for persons in wheelchairs. Providing

wheelchair accessible taxicabs creates a unique, however necessary challenge for the future.

Seeking to improve Bostons wheelchair accessible taxicab services, the DPC has partnered with

Northeastern University School of Law to create a social justice project for a group of first-year

law students. The project consists of legal research and case analysis, integrating the findings of

each to provide a framework for recommendations to improve overall accessibility of taxicabs.

Recommendations

The DPC has a variety of strategies at its disposal to initiate an aggressive campaign to

increase the number of WAVs in Massachusetts. Several municipalities within the

Commonwealth, including Boston, Brookline, and Cambridge, have model taxicab

infrastructures in place. Other municipalities within the Commonwealth may look to these

-

9

models to ensure that each community has adequate WAV services. However, these systems

may be further strengthened to push Massachusetts to the forefront of the nations parantransit

service providers. The DPC may facilitate efforts across Massachusetts by examining and

applying strategies used by model cities and other states across the nation.

Litigation and legislation as a two-pronged attack has proven to be an extremely

successful means of heightening public awareness as a catalyst for change. In the majority of the

case studies litigation and legislation has preceded any meaningful change to the taxicab

infrastructure. These case studies reveal that through litigation the DPC has an opportunity to

bring lawsuits against municipalities for failing to comply with both Title II and Title III of the

ADA. This litigation strategy is the impetus for states and municipalities to enforce taxicab

regulations under federal statute. In addition to increasing public awareness and the number of

WAVs through litigation, the DPC can lobby the government to pass legislation requiring a

minimum number of WAVs be available within each community.

To ensure compliance with the resulting laws and regulations from the DPCs advocacy

efforts, it is necessary to incentivize these initiatives. The DPC may inform both taxicab

companies and municipalities about federal and state funding programs. Through the MAP-21

program, green initiatives, and partnering with elder advocates, these groups can pool valuable

resources towards a more effective means of garnering momentum for the goal of acquiring

WAVs.

There exists a large array of opportunities for the DPC to forever alter the disability

advocacy in Massachusetts by increasing the number of transportation options for persons with

disabilities. Through litigation, legislation, and an increase in funding, taxicab companies can

meet the high standards that the DPC has set for disability advocacy within the state of

-

10

Massachusetts. Overall, the report concludes that cab fleets maintaining a portion of accessible

taxicabs for door-to-door services is in the best long-term interest for both the public with a

disability and the taxicab companies.

-

11

I. INTRODUCTION

Many persons with disabilities1 within the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, especially

those in wheelchairs, do not have adequate access to taxicab services. Massachusetts paratransit

system is accessible to people in wheelchairs. However, to achieve true mobility and equal

access to transportation, the Disability Policy Consortium (DPC) is seeking ways to increase the

number and availability of wheelchair accessible vehicles (WAVs) across Massachusetts. The

DPC works to educate, connect, and organize with persons with disabilities to participate in the

electoral and legislative processes, to become active in their communities, and to advocate for

justice and equality.2

Since 1996, the DPC has provided the disability community with a voice through

legislative advocacy.3 Most recently, disability advocates came together to engage in impact

litigation against the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission to improve the

availability of taxicab services in New York.4 This case, though unsuccessful thus far, has

prompted the DPC to seek similar legal solutions in Massachusetts.

In the fall of 2012, the DPC approached the Northeastern University School of Law to

1 The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has a three-part definition of disability. Under the ADA, an individual

with a disability is a person who: (1) has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major

life activities; OR (2) has a record of such an impairment; OR (3) is regarded as having such an impairment. 42

U.S.C. 12102(1). A physical impairment is defined by the ADA as "any physiological disorder or condition,

cosmetic disfigurement, or anatomical loss affecting one or more of the following body systems: neurological,

musculoskeletal, special sense organs, respiratory (including speech organs), cardiovascular, reproductive, digestive,

genitourinary, hemic and lymphatic, skin, and endocrine." Neither the ADA nor the regulations that implement it list

all the diseases or conditions that are covered, because it would be impossible to provide a comprehensive list, given

the variety of possible impairments.

We recognize that the term disability summarizes a great number of different functional limitations

occurring in any population. People may be disabled by physical, intellectual or sensory impairment, medical

conditions or mental illness. Such impairments, conditions or illnesses may be permanent or transitory in nature. For

the purpose of this report, when referring to persons with disabilities, we will be referring to people who have

problems with mobility and use a wheelchair. We acknowledge this population is not confined solely to people with

a disability, but could also encompass the elderly or people with temporary injuries requiring them to use mobility

devices. 2 DISABILITY POLICY CONSORTIUM, http://www.dpcma.org/ (March 9, 2013).

3 DISABILITY POLICY CONSORTIUM, http://www.dpcma.org/ (March 9, 2013).

4 Noel v. New York City Taxi and Limousine Com'n, 837 F.Supp. 2d 268 (2011).

-

12

research regulatory structure of taxicab services under the Americans with Disabilities Act

(ADA), Massachusetts law, and laws of the surrounding municipalities. Specifically, this report

outlines the laws governing taxicab regulation, an overview of municipalities in Massachusetts

and model cities across the United States, and potential solutions to taxicab accessibility through

legal initiatives, funding, and policy. This report will act as a guide for the DPC, as it decides the

best strategies to improve availability of WAVs across the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

A. MBTA LIMITATIONS: THE RIDE

The main paratransit5 service for persons with disabilities within the Boston area is The

Ride, managed by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA).6 There is debate as

to whether The Ride is adequate as the sole mode of transportation available to persons with

disabilities. This section highlights how The Ride operates, the effects of the MBTA deficit and

fare hikes on The Ride, and why persons with disabilities would prefer taxicabs instead of The

Ride.

The MBTA operates The Ride in accordance with federal regulation:

Any public entity which operates a fixed route system[7]

[must

provide] paratransit and other special transportation services to

individuals with disabilities, including individuals who use

wheelchairs, that are sufficient to provide to such individuals a

level of service (1) which is comparable to the level of designated

public transportation services provided to individuals without

disabilities using such system; or (2) in the case of response time,

which is comparable, to the extent practicable, to the level

5 49 C.F.R. 37.3 (2011). Paratransit means comparable transportation service required by the ADA for individuals

with disabilities who are unable to use fixed route transportation systems. 6 Riding the T, MBTA.COM, http://www.mbta.com/riding_the_t/accessible_services/default.asp?id=7108 ( last

visited Mar. 9, 2013). 7 42 U.S.C 12141 (2013). Fixed route system is defined as a system of providing designated public transportation

on which a vehicle is operated along a prescribed route according to a fixed schedule.

http://www.mbta.com/riding_the_t/accessible_services/default.asp?id=7108

-

13

designated public transportation services provided to individuals

without disabilities using such system.[8]

The Ride is a door-to-door, shared ride service.9 It operates 365 days of the year from

5:00 a.m. to 1:00 a.m. and personal care assistants or guests are allowed to accompany the rider

free of charge.10

Service extends only to three-quarters of a mile from any bus or subway stop.11

If the service is outside of that area there is a $5.00 premium fare.12

The Rides fleet consists of

363 WAVs.13

While this service provides a certain level of independence, it vastly limits persons

using it to a specific timeframe and location.

Those using The Ride must call ahead or go online to make a reservation up to 14 days in

advance.14

Reservations may be changed until 5:00 p.m. the day before their requested ride.15

Requested departure and arrival times must be an hour apart.16

Requests can be made for same-

day service or after 5:00 p.m. the day before but are not guaranteed.17

If The Ride is able to

provide the service, the premium fee will be charged.18

According to federal regulations, the

entity shall not require an ADA paratransit eligible individual to schedule a trip to begin more

than one hour before or after the desired departure time.19

The goal of scheduling is to make the

most efficient use of vehicles to ensure the service is available to all who need it.20

The Ride is

8 42 U.S.C.S. 12143 (1990).

9 THE RIDE Guide (Mar. 9, 2013, 2:31 PM),

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/Riding_the_T/Accessible_Services/The_Ride/RIDEGUIDE0701120R3.1.pdf. 10

Id. 11

49 C.F.R. 37.131 (2006). 12

THE RIDE Guide (Mar. 9, 2013, 2:31 PM),

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/Riding_the_T/Accessible_Services/The_Ride/RIDEGUIDE0701120R3.1.pdf. 13

Telephone Interview by Devin Morse with Tim Robbins, MBTA Representative (March 3, 2013). 14

THE RIDE Guide (Mar. 9, 2013, 2:31 PM),

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/Riding_the_T/Accessible_Services/The_Ride/RIDEGUIDE0701120R3.1.pdf. 15

Id. 16

Id. 17

Id. 18

Id. 19

49 C.F.R. 37.131(b)(2) (2006). 20

THE RIDE Guide (Mar. 9, 2013, 2:31 PM),

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/Riding_the_T/Accessible_Services/The_Ride/RIDEGUIDE0701120R3.1.pdf.

-

14

ADA compliant,21

but is not meant to be a comprehensive system, merely a safety net for those

people whose disabilities prevent them from using the regular fixed route system.22

In order to use The Ride, users must apply, interview, and be approved by a Mobility

Coordinator.23

The Ride is available to visitors of Boston for 21 days in a 12-month period. The

visitor must be able to provide an ADA Paratransit Certificate of Eligibility from the persons

home transit agency and a plan of how that person plans to utilize the program during his or her

visit.24

On July 1, 2012, the one-way fare increased from $2.00 to $4.00 each way.25

According

to federal regulations, the ADA fare must not be more than twice the standard fare for a trip of

similar length, at a similar time of day, on the entitys fixed route system.26

As of October 1,

2012, if the trip is non-ADA,27

the reservation is made on the same day, or is outside of the

three-quarter mile area of a bus or subway, then the premium fare is $5.00 each way.28

21

49 C.F.R. 37.131(a) (2006) states:

The entity shall provide complementary paratransit service to origins and

destinations within corridors with a width of three-fourths of a mile of each side

of each fixed [bus] route. (2) For rail systems, the service area shall consist of

a circle with a radius of of a mile around each station.

49 C.F.R. 37.131 (2006) states:

(c) The fare for a trip charged to an ADA paratransit eligible user of the

complementary paratransit service shall not exceed twice the fare that would be

charged to an individual paying full fare for a trip of similar length, at a similar

time of day, on the fixed route system (e) The complementary paratransit

service shall be available throughout the same hours and days as the entitys

fixed route service. 22

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, Riding the T, THE RIDE (Mar. 9, 2013, 2:31 PM),

http://www.mbta.com/riding_the_t/accessible_services/default.asp?id=7108. 23

Id. 24

Id. 25

Id. 26

49 C.F.R. 37.131(c) (2006). 27

2012 MBTA Fare Policy (Mar. 9, 2013, 2:39 PM),

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/Fares_and_Passes_v2/Final%202012%20MBTA%20Fare%20Policy%20Effect

ive%20July%201,%202012.pdf. Non-ADA trips include those which either the origin or destination is not within

the ADA-mandated service area [or] for trips that begin or end outside of the ADA-mandated service hours 28

THE RIDE Guide (Mar. 9, 2013, 2:39 PM).

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/Riding_the_T/Accessible_Services/The_Ride/RIDEGUIDE0701120R3.1.pdf.

-

15

Currently, the MBTA has a debt burden of $5.2 billion, which is the highest of any transit

agency in the United States.29

As of June 2013, the MBTA projects to have an $185 million

budget gap.30

As well, the MBTA has seen a 400 percent increase of ridership on The Ride alone

over the past decade.31

While The Rides operating costs have increased over the past 10 years,

the primary cost increase has been due to exponential growth in ridership on [the] service.32

The

fare hikes in 2012 (as of July 1 and October 1, 2012) increased ADA fares from $2.00 to $4.00

each way and increased non-ADA, outside of service or same-day fares to $5.00.33

However, the

MBTA did not reduce the service area.34

Since many persons who use The Ride are on a fixed or low income, the fare hike is

reducing the number of times they can use the service.35

Many have already cut back on their

usual number of outings, such as grocery shopping trips and doctor visits.36

In a recent Boston

Globe article, Karen Schneiderman, a senior advocacy specialist at the Boston Center for

Independent Living, stressed the importance for persons with disabilities to have the ability to

leave their homes and live their lives.37

Staying trapped in your home yes, its diminishing

quality of life, but its actually shortening the lifespan of people, Schneiderman said. 38

If you

29

MBTA Fare and Service Changes (Mar. 9, 2013, 2:52 PM),

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/About_the_T/Fare_Proposals_2012/MC12149%20Fare%20Increase%20Bookl

et_v7.pdf. 30

Id. 31

Id. 32

Id. 33

THE RIDE Guide (Mar. 9, 2013, 2:52 PM),

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/Riding_the_T/Accessible_Services/The_Ride/RIDEGUIDE0701120R3.1.pdf. 34

PowerPoint: MassDOT, MBTA 2012 Fare and Service Changes Presentation at the Staff Recommendation

Meeting (March 28, 2012), available at

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/About_the_T/Fare_Proposals_2012/MBTA%202012%20Fare%20and%20Serv

ice%20-%20RecommendationV2.pdf. 35

Kathleen Burge, For the Disabled, Fare Hikes on Ts Ride a Jolt, THE BOSTON GLOBE, July 29, 2012. 36

Martine Powers, The Ride Less Ridden After Increase in Fare, THE BOSTON GLOBE, February 2, 2013, at A1. 37

Id. 38

Id.

-

16

just sit in your house all the time and you cant get out, you cant see people, and you cant do

anything you enjoy, your life feels less valuable.39

To attempt to decrease its deficit, the MBTA raised fares and hoped that it would not lose

too many customers.40

However, since the fare hike, travel on The Ride has declined more

drastically than the 10.3 percent drop-off [MBTA] officials predicted last March, [2012].41

Between July and December of 2012, registered passengers rides decreased by 16.2 percent

from the same six-month period in 2011.42

When the MBTA looked at reducing its operating deficit, it also evaluated other cities

paratransit services comparing services and fares.43

Philadelphia, whose services are subsidized

by lottery funds, already charged $4.00 for ADA accommodations, but only $4.00 for premium

services.44

Also, Philadelphias system, as well as Atlantas and Los Angeles services, are only

curb-to-curb, as opposed to Bostons door-to-door.45

New York, Chicago, Atlanta, and Los

Angeles all charge below the $4.00 fare for ADA accommodations and do not charge a premium

fare.46

San Francisco and Washington D.C. fares vary from $2.00 to $7.00 for ADA

accommodations.47

They also have no premium fare.48

San Francisco employed more creative

methods and now offers a premium service through a taxicab debit card program that can be

39

Id. 40

PowerPoint: MassDOT, MBTA 2012 Fare and Service Changes Presentation at the Staff Recommendation

Meeting (March 28, 2012), available at

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/About_the_T/Fare_Proposals_2012/MBTA%202012%20Fare%20and%20Serv

ice%20-%20RecommendationV2.pdf. 41

Martine Powers, The Ride Less Ridden After Increase in Fare, THE BOSTON GLOBE, February 2, 2013, at A1. 42

Id. 43

PowerPoint: MassDOT, MBTA 2012 Fare and Service Changes Presentation at the Staff Recommendation

Meeting (March 28, 2012), available at

http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/About_the_T/Fare_Proposals_2012/MBTA%202012%20Fare%20and%20Serv

ice%20-%20RecommendationV2.pdf. 44

Id. 45

Id. 46

Id. 47

Id. 48

Id.

-

17

same-day service and serves some areas outside of the three-quarter mile zone.49

This could be

an option that Boston could pursue and these options will be presented through city case studies

in Section V of this report.

Current deficiencies of The Ride include inconvenience, inefficiency, and limitations on

service areas. Particularly, reservations are an inconvenience. They must be made a day ahead of

time, or the user will be charged a premium fee. Unanticipated trips and emergencies present a

disproportionate burden to persons with disabilities since they are unable to hail a WAV. The

Ride may not show up at the scheduled time and advises riders to have a Plan B. Riders may

not be able to create such alternative plans easily. The Ride may be their only source of

transportation. A taxicab would be a Plan B that could be used if The Ride is not available.50

Since The Ride conducts shared rides, there are more rules in place for the courtesy of

others such as no perfume, eating, or animals. Taxicabs on the other hand are usually not shared,

so the rider is able to take greater liberty and control of their situation.51 The Ride is only

available in areas that are three-quarters of a mile from a bus or subway line. This is extremely

limiting for those persons who may have appointments outside of that area.52 While the MBTAs

The Ride is ADA compliant and comparable to other cities paratransit services, it does not meet

the total needs of all persons with disabilities. Paired with the fare increases, The Ride may not

be a viable or desired resource for those persons with disabilities needing and wanting to leave

their house and go to places of business and entertainment within the Boston area.

B. TRANSPORTATION ISSUES AND THE ELDERLY

49

Id. 50

EASTER SEALS PROJECT ACTION, ACCESSIBLE COMMUNITY TRANSPORTATION IN OUR NATION: A SURVEY

ON THE USE OF TAXIS IN PARATRANSIT PROGRAMS (2008). 51

Id. 52

Id.

-

18

Limited access to transportation does not only affect persons with disabilities, it affects

Massachusetts elderly population as well. The DPC will benefit by joining forces with senior

advocates to increase wheelchair accessibility to taxicabs across the Commonwealth. The aging

of baby boomers in the United States are leading to high populations of elderly people within

the Commonwealth.53

According to the 2010 Census, there were 902,724 people over 65 years of

age in Massachusetts.54

The growing senior population will strain the Massachusetts public and

private transportation services, which are also used by persons with disabilities.

Demand for transportation is already high and will continue to grow.55

The Metrowest

Regional Transit Authority currently serves over 70,000 seniors with door-to-door services.56

In

fact, according to a national report by Transportation for America, by 2015, 45 percent of seniors

in the Boston area, or roughly 232,000 people, will lack access to nearby bus or rail

transportation.57

To combat the problems facing seniors, advocates are currently working to

improve accessibility for seniors through non-profit services. These services include

ITNGreaterBoston58

(in Metrowest) and SCM's Door2Door Transportation59

(in Somerville,

Cambridge, and Medford).60

These programs provide a promising start, however they do not

53

David E. Bloom, ET AL. Population Aging: Facts, Challenges, and Responses, PROGRAM ON THE GLOBAL

DEMOGRAPHY OF AGING, HARVARD PUBLIC HEALTH (May, 2011), available at

http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/pgda/WorkingPapers/2011/PGDA_WP_71.pdf. 54

David Riley, Growing Senior Population Faces Poor Public Transit Options, Metrowest Daily News, July 5, 2011,

at 1, available at http://www.metrowestdailynews.com/news/x1107265221/Growing-senior-population-faces-poor-

public-transit-options#ixzz2GpJn8iro. 55

TRANSPORTATION OF AMERICA, AGING IN PLACE, STUCK WITHOUT OPTIONS: FIXING THE MOBILITY CRISIS

THREATENING THE BABY BOOM GENERATION, 50 (June 14, 2011) available at

http://t4america.org/resources/seniorsmobilitycrisis2011/ Aging in Place, Stuck Without Options. 56

David Riley, Growing Senior Population Faces Poor Public Transit Options, Metrowest Daily News, July 5, 2011,

at 3, available at http://www.metrowestdailynews.com/news/x1107265221/Growing-senior-population-faces-poor-

public-transit-options#ixzz2GpJn8iro. 57

Id. 58

ITN Greater Boston: Dignified Transportation for Seniors, (January 26, 2013), available at

http://www.itngreaterboston.org/. 59

Door2Door Transportation by SCM (January 26, 2013), available at http://www.scmtransportation.org/. 60

David Riley, Growing Senior Population Faces Poor Public Transit Options, Metrowest Daily News, July 5, 2011,

at 3, available at http://www.metrowestdailynews.com/news/x1107265221/Growing-senior-population-faces-poor-

public-transit-options#ixzz2GpJn8iro.

-

19

adequately address current and growing populations.61

The desperate need for adequate transportation, for both seniors and persons with

disabilities, cannot be solved through public services and non-profits alone. New and creative

solutions must be found to serve the elderly and persons with disabilities. Taxicab companies are

preexisting systems that can be easily suited to serve these high-need populations. Rather than

reinventing the wheel, Boston can improve access to transportation for the elderly and persons

with disabilities by leveraging taxicab companies. The taxicab companies will potentially benefit

from increased revenue and a larger clientele base. It is crucial that advocates for both seniors

and persons with disabilities unite to demand increased access to public transportation. Rather

than reforms being seen as a threat, taxicab companies may have opportunities to receive public

funding to subsidize the cost of new or remodeled taxicabs. Furthermore they may be able to

increase business by serving a new customer base and serve this growing population in need of

assistance, as is detailed throughout this report. It is important to remember that these issues

impact everyone. While we will not all experience disability as we age, we may all require

similar services to help us maintain our ability to live independently and move freely within our

own communities.

II. LITIGATION UNDER THE ADA

On July 26, 1990, the United States Congress passed the ADA to provide a clear and

comprehensive national mandate for the elimination of discrimination against persons with

disabilities.62

The ADA is a wide-ranging civil rights law organized into five titles, each

61

TRANSPORTATION OF AMERICA, AGING IN PLACE, STUCK WITHOUT OPTIONS: FIXING THE MOBILITY CRISIS

THREATENING THE BABY BOOM GENERATION, 50 (June 14, 2011) available at

http://t4america.org/resources/seniorsmobilitycrisis2011/ Aging in Place, Stuck Without Options. 62

42 U.S.C. 12101(b)(1) (2013).

-

20

prohibiting discrimination in a particular setting.63

The current subject of concern is the

regulation of taxicab companies; therefore the applicable sections of the ADA are Title II and

Title III.64

Title II applies to public entities such as municipal governments who license taxicab

companies to conduct business. Title III addresses the activities of private entities considered

public accommodations.65

Public entities and public accommodations are defined below.

In order to establish a violation under the ADA one must demonstrate that three elements

have been met: (1) The plaintiff is a qualified individual with a disability,66

(2) the defendant is

subject to liability under the ADA,67

and (3) the plaintiff was denied the opportunity to

participate in or benefit from the defendants services, programs, or activities.68

Taxicab

companies are privately owned but regulated and licensed by municipal governments; therefore,

they occupy a troublesome space in regards to ADA litigation. To address this issue, the DPC

must consider:

(1) Whether a governmental regulatory body may be held liable for

the discriminatory acts of the taxicab industry, as a private

company regulated by a public entity, and (2) whether taxicabs are

considered to be a public accommodation under the ADA such that

the private companies may be held directly liable for their

discriminatory acts under Title III.69

Massachusetts statutes and regulations must be taken into account in conjunction with

63

42 U.S.C. 12101 (2013). 64

42 U.S.C. 12181-12189 (1990). 65

Id. 66

42 U.S.C. 12131 (1990) defines a qualified individual with a disability as:

an individual with a disability who, without reasonable modifications to rules,

policies, or practices, along with the removal of architectural, communication or

transportation barriers, or the provision of auxiliary aids and services, meets the

essential eligibility requirements for the receipt of services or the participation in

programs or activities provided by a public entity. 67

42 U.S.C. 12131, 12181 (1990). Subject to the ADA in the taxicab accessibility context means that the

defendant is considered either a public entity under Title II or and public accommodation under Title III. 68

Id. The claims put forth by a plaintiff must meet the definition of discrimination and prohibited behaviors and

activities as defined under the ADA. 69

Noel v New York City Taxi and Limousine Com'n, 837 F. Supp 2d 268, 272 (1st Cir. 2011).

-

21

the ADA.70

The Massachusetts definition of public accommodation is found later in section B,

while all other state statutes and regulations that may be helpful in litigation are discussed in

Section III of this document.

A. TITLE II: PROHIBITION OF DISCRIMINATION BY PUBLIC ENTITIES

Title II of the ADA, public services, is further separated into Subtitles A and B which

prohibit discrimination against persons with disabilities by public entities operating certain types

of public transportation systems.71

Title II, Subtitle A states: no qualified individual with a disability shall, by reason of

such disability, be excluded from participation in or be denied the benefits of the services,

programs, or activities of a public entity.72

Public entity is defined as any state or local

government and any of its departments, agencies, or other instrumentalities.73

Title II of the

ADA does not immediately construe taxicabs as a public entity, since they are owned and

operated by private companies.74

The regulation of taxicab companies is the responsibility of the

municipal government in which the taxicab company operates.75

In recent cases, arguments have

been made that the taxicab industry itself is actually a service, program, or activity of the city

government.76

If construed in that manner, a municipal government which licenses and regulates

the local taxicab industry and excludes from participation or denies the benefits of taxicab

services to persons with disabilities may be found liable for such discrimination.77

70

Kuketz v. Petronelli, 443 Mass. 355, 359-60, 821 N.E.2d 473, 476 (2005). 71

42 U.S.C. 12131-12189 (1990). 72

42 U.S.C. 12131-12132 (1990). 73

Id. 74

42 U.S.C. 12131 (1) (1990). 75

New York Taxi and Limousine Comn, 837 F.Supp. 2d 268 (2011). This argument was put forth in Noel v. New

York City Taxi and Limousine Comn which will be explored in detail in the following pages. 76

Id. 77

42 U.S.C. 12132 (1990).

-

22

1. Subtitle A: Taxicab Regulatory Bodies as Public Entities

Through arguments in litigation, it has been suggested that the ADA must be broadly

construed to effectuate its purpose, which is the elimination of discrimination against persons

with disabilities.78

However, one must recognize that the premise of any Title II, Subtitle A

argument in the field of taxicab accessibility is a great expansion of the ADA as it was written. A

claim brought under this particular subtitle may not succeed.

The crux of a Title II, Subtitle A claim depends upon the argument that taxicab regulating

bodies are entities closely related to the taxicab companies themselves, like the Taxi and

Limousine Commission (TLC) seen in Noel v. New York City Taxi and Limousine

Commission.79

The relationship between the regulatory bodies and the taxicab companies is

established through the granting of operating licenses and the regulation of rates and driver

conduct.80

Therefore, the public entity is in fact discriminating against persons with disabilities

by failing to require taxicab companies to operate accessible vehicles or by granting licenses to

taxicab companies, which do not operate a sufficient number of accessible vehicles.81

While one

cannot deny that a municipal level taxicab regulatory body is considered a public entity as

defined in 12131,82

it is a question for the court. The court must determine whether the

granting of licenses and the regulation of certain operating requirements of taxicab companies,

which fail to make their services accessible to individuals with disabilities, is sufficient to

constitute a discriminatory program, service or activity of a public entity under Title II.83

While the Department of Transportation (DOT) says that licensing cannot be a means for

78

Noel v. New York City Taxi and Limousine Com'n, 837 F.Supp. 2d 268 (2011) citing to Innovative Health Sys. v.

White Plains, 931 F.Supp. 222, 232 (S.D.N.Y.1996). 79

Noel v. New York City Taxi and Limousine Com'n, 837 F.Supp. 2d 268 (2011). 80

Id. 81

Id. 82

28 C.F.R. 35.104 defining Public Entity as any department, agency, special purpose district, or other

instrumentality of a State or States or local government. 83

42 U.S.C. 12131-12132 (1990).

-

23

liability on the part of a public entity for actions of a taxicab entity,84

this argument was still put

forth in Noel, where it ultimately failed on this point.85

Because Noel was brought under federal

law in New York, which is in the Second Circuit, the decision would not be considered binding

on a similar case if brought in Massachusetts, which is located in the First Circuit.

2. Recent Litigation of Subtitle A: Noel v. New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission

Noel was a civil suit brought against the taxicab regulatory body of New York City

(NYC), which alleged discrimination against individuals with disabilities under the ADA Title II

and Title III, the Rehabilitation Act, and New York Human Rights Law.86

The plaintiff put forth

an argument premised on Title II, Subtitle A, which was successful on partial summary judgment

at the trial court level but was later overturned on appeal.87

The trial court found the defendant,

TLC, was a public entity and was violating Subtitle A of the ADA by failing to provide

meaningful access to taxicab services for persons with disabilities.88

The trial court reasoned that

TLC is a public entity carrying out a public regulatory function that affects and confers a benefit

to NYC taxicab riders and therefore may not discriminate.89

Support for this holding was found

in the legislative history of the ADA, which explains that [Title II] simply extends the anti-

discrimination prohibition in [the Rehabilitation Act] to all actions of state local governments.90

Additional support was based on the Department of Justice (DOJ) regulations implementing Title

II which explained that a public entity in providing any aid, benefit, or service, may not,

directly, or through contractual, licensing, or other arrangements, on the basis of disability, deny

84

49 CFR 37.37 (1991). 85

Noel v. New York City Taxi & Limousine Comm'n, 687 F.3d 63 (2d Cir. 2012). 86

Id. 87

Id. 88

Noel v. New York City Taxi & Limousine Comm'n, 837 F. Supp. 2d 268, 276 (S.D.N.Y. 2011). 89

Id. 90

Noel v. New York City Taxi & Limousine Comm'n, 837 F. Supp. 2d 268, 276 (S.D.N.Y. 2011) citing to 28

C.F.R. 35.130(b)(1)(i) (2011).

-

24

a qualified individual with a disability the opportunity to participate in or benefit from the aid,

benefit or service.91

The DOJ regulations further mandate that public entities be prohibited from

establishing requirements for programs or activities of licensees that subject qualified

individuals with disabilities to discrimination on the basis of disability.92

This partial summary judgment on Title II, Subtitle A was later overturned on appeal

when the court held that the TLC exercises pervasive control over the taxicab industry in NYC.

Defendants were not required by Title II to deploy their licensing and regulatory authority to

mandate that persons who need wheelchairs be afforded meaningful access to taxis.93

Rather, the

appellate court held that Title II, Subtitle A merely governs the conduct of the public entity

regulating the taxicab industry, not the conduct of those private entities.94

The regulations which

were promulgated to implement Title II:

prohibit a public entity from administer[ing] a license or

certification program in a manner that subjects qualified

individuals with disabilities to discrimination on the basis of

disability [or] establish[ing] requirements for the programs or

activities of licensees or certified entities that subject qualified

individuals with disabilities to discrimination on the basis of

disability.[95]

Under this application, the appellate court found that Title II prohibits the TLC from

refusing to grant licenses to qualified persons with disabilities seeking to obtain a license to

operate a taxicab but does not protect consumers of the taxicab operators service.96

While the

DPC would benefit from this application to all passengers, the appellate court held that Title II,

Subtitle A simply applied to the licensing process, and not to the activities of the licensees which

91

Noel v. New York City Taxi & Limousine Comm'n, 837 F. Supp. 2d 268, 276 (S.D.N.Y. 2011) citing to 28

C.F.R. 35.130(b)(6) (2011). 92

Id. 93

Noel v. New York City Taxi & Limousine Comm'n, 687 F.3d 63 (2d Cir. 2012). 94

Noel v. New York City Taxi & Limousine Comm'n, 687 F.3d 63, 69 (2d Cir. 2012) citing to 28 C.F.R.

35.130(b)(6) (2011). 95

Id. 96

Noel v. New York City Taxi & Limousine Comm'n, 687 F.3d 63, 69 (2d Cir. 2012).

-

25

are the actions of the taxicab companies.

The court found that Title II afforded a stricter interpretation of the services, programs,

and activities of a public entity. This finding resulted in a reversal of the judgment by the lower

court, in favor of the defendant, TLC.97

At this time, it is unknown if the plaintiff in Noel is

further appealing this issue.

3. Subtitle A: Arguments Applied to Massachusetts

Although the favorable ruling under Title II, Subtitle A was overturned on appeal, it is

important to recognize that this argument was persuasive to the trial court.98

Since Massachusetts

is a progressive circuit, the chances of prevailing under a broad interpretation of the ADA may

be likely. As stated above, the courts ruling in Noel is not binding on a court in Massachusetts

because they are located in different federal circuits.99

However, the Noel case may be

considered persuasive authority, and the court in Massachusetts may rule in a manner consistent

with the appellate court in Noel, for the same or different reasons.100

Title II provides for liability only against public entities.101

There is substantial

disagreement among courts as to whether private companies can be held liable under Title II

when they perform contracted services102

for the government.103

Many courts hold the view that,

even where such a private entity contracts with a government to perform a traditional and

essential government function, it remains a private company, not a public entity.104

Although

97

Id. 98

Id. 99

Id. 100

Id. 101

42 U.S.C. 12131-12132 (1990). 102

Armstrong v. Schwarzenegger, 622 F.3d 1058 (9th Cir. 2010). Such contractual services include licensing or

other arrangements, discriminating against persons with disabilities. 103

Wilkins-Jones v. County of Alameda, 859 F. Supp. 2d 1039 (N.D. Cal. 2012). 104

Armstrong v. Schwarzenegger, 622 F.3d at 1058 citing to Edison v. Douberly, 604 F.3d 1307, 1309-10 (11th Cir.

2010).

-

26

our research has not provided beneficial precedent regarding this issue in the First Circuit, a

decision that would be considered binding authority if brought in Massachusetts, there has been

persuasive litigation in the Ninth Circuit applying Title II to private entities contracting services

for the government.105

This is not binding authority, but is certainly persuasive.

In Armstrong v. Schwarzenegger, the court held public entities may not contract their

liability by partnering with private entities to perform certain services.106

The court in Armstrong

stated, public entity, in providing aid, benefit, or service, may not, directly or through

contractual licensing, or other arrangements, discriminate against individuals with

disabilities.107

The court also provided the illustration of a private restaurant operated within a

state park and the state Department of Parks, a public entity, was subject to Title II.108

The parks

department was obligated to ensure, by contract, that the restaurant was operated in a manner

that enabled the parks department to meet its Title II obligations, even though the restaurant was

not directly subject to Title II.109

Although taxicabs are private entities, and therefore not directly

subject to Title II,110

their regulation is the responsibility of the municipal government in which

the taxicab company operates. Therefore, because the government provides aid to taxicab

companies through licensing, they cannot contract their liability while discriminating against

persons with disabilities in wheelchairs by not providing enough accessible taxicabs.

Moreover, for public policy reasons, the public entity remains liable for the unlawful acts

of its agent, even if that agent, a private entity, is not itself liable under Title II of the ADA.111

Thus, even though a plaintiff does not have recourse under Title II directly against the private

105

Wilkins-Jones v. County of Alameda, 859 F. Supp. 2d 1039 (2012). 106

Armstrong v. Schwarzenegger, 622 F.3d 1058 (2010). 107

28 C.F.R. 35.130(b)(1) (2011). 108

See Department of Justice, The Americans with Disabilities Act: Title II Technical Assistance Manual II-

1.3000 (1993). 109

Id. 110

42 U.S.C. 12131(1) (1990). 111

Wilkins-Jones v. County of Alameda, 859 F. Supp. 2d at 1039. Citing to Armstrong, 622 F.3d at 1058.

-

27

entity, she still has recourse against the government when a private contract violates the ADA.112

Although a plaintiff does not have recourse against taxicabs under Title II, she may still have

recourse against the government for their regulation.

In determining whether the conduct of an otherwise private actor constitutes indirect state

action, courts have traditionally deemed a private entity to have become a state actor if (1) it

assumes a traditional public function when it undertakes to perform the challenged conduct,113

or

(2) an elaborate financial or regulatory nexus ties the challenged conduct to the State, or (3) a

symbiotic relationship exists between the private entity and the State.114

Taxicabs can be

indirectly related to the state under the first criterion. In Carmack v. Massachusetts Bay

Transportation Authority, the court held that security guards employed by a private corporation

performed a traditional public function115

when they arrested citizens that were distributing

leaflets on a public walkway.116

The court reasoned that in deciding who can use the public

[walkway], and under what circumstances the security guards performed more akin to a

policeman [than a] private contractor.117

Therefore, the DPC may benefit from arguing that

private taxicabs operating on public streets are indirectly tied to the state, as their actions closely

resemble that of a common carrier, which is a traditional public function.

Historically, the Boston Hackney Division118

falls under the second criterion, since it is

regulated and receives its licenses through the Boston Police and the Department of Public

112

Wilkins-Jones v. County of Alameda, 859 F. Supp. 2d at 1039. 113

Note that under current case law these criteria are disjunctive, indicating that only one of the three must be met to

demonstrate indirect state action. 114

Perkins v. Londonderry Basketball Club, 196 F.3d 13, 18 (1st Cir. 1999); Richards v. City of Lowell, 472 F.

Supp. 2d 51, 73 (D. Mass. 2006). 115

Id. 116

Carmack v. Mass. Bay Trans. Auth., 465 F.Supp.2d 28 (D. Mass. 2006). 117

Id. 118

City of Boston.gov, Boston Licensed Hackney Carriages, (Mar. 6, 2013, 12:47PM),

http://www.cityofboston.gov/police/hackney/taxis.asp. Boston's Taxis, historically called Hackney Carriages, are

licensed by the Police Commissioner under the authority of Chapter 392 of the Acts of 1930. The unit is

commanded by a Boston Police Superior Officer who bears the title of Inspector of Carriages and who regulates the

taxi industry as direct by the Police Commissioner.

-

28

Utilities, both state actors. The 1930 Mass. Acts 392 (amend. 1933 and 1934) authorizes the

Boston Police Commissioner to regulate the taxicab business in Boston in part by issuing

hackney licenses, or medallions, authorizing the holder to operate a cab within the city. 119

If the

Commissioner denies an application for a medallion because the maximum number has been

reached, an applicant may appeal to the Department of Public Utilities, which then may

determine that the public convenience and necessity requires a higher limit and shall establish the

limit so required, under the 1934 Mass. Acts 280.120

In addition, the Hackney Division receives

up to $500 a week for the medallions.121

This further demonstrates the existence of a financial

connection between taxicab companies and the state.

Unfortunately for the DPC, there is persuasive precedent in the First Circuit that states:

For a private actor to be deemed to have acted under color of state

law, it is not enough to show that the private actor performed a

public function. Rather, the plaintiff must show that the private

entity assumed powers traditionally exclusively reserved to the

state. The exclusive function test screens for situations where a

state tries to escape its responsibilities by delegating them to

private parties.[122]

In Richards v. City of Lowell, however, the court found that although Richards could not

establish direct state action, he had presented enough facts to create a genuine dispute as to

whether the defendants' actions were fairly attributable to the state under a theory of indirect

state action. 123

If the DPC were to bring a claim under Title II advocating that taxicabs may be

tied to indirect state action, this claim may prove to be fruitful.

4. Subtitle B: Public Entities Which Provide Public Transportation

Title II, Subtitle B of the ADA addresses discriminatory acts by public entities, which

119

Boston Neighborhood Taxi Ass'n v. Department of Public Utilities, 410 Mass. 686, 687 (Mass. 1991). 120

Id. 121

The exact amount was not provided in the lease agreement for the medallions. 122

Barrios-Velazquez v. Associcion De Empleados Del Estado Libre Asociado, 84 F.3d 487, 493 (1st Cir. 1996). 123

Richards v. City of Lowell, 472 F. Supp. 2d 51, 73 (D. Mass. 2006).

-

29

provide public transportation services.124

The legislation is broken into two parts: (1) public

transportation in forms other than aircraft or certain rail operations, and (2) public transportation

by intercity and commuter rail systems.125

Subtitle B, Part One applies to public entities operating a fixed route system, a demand

responsive system, or a paratransit system which supplements a fixed route system.126

A

demand responsive system is any system of providing designated public transportation127

which is not a fixed route system.128

When a public entity operates a demand responsive system

it is considered discrimination for the system if, when viewed in its entirety, it does not provide

the same level of service to persons without disabilities as it does to persons with disabilities.129

This section is inapplicable for the DPC because there is no evidence that such a taxicab

company, owned and operated by a public entity and providing demand-responsive services, is in

existence in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

A fixed route system is defined as a system providing designated public transportation

in which a vehicle is operated along a prescribed route according to a fixed schedule.130

An

example of this type of public transportation system is the MBTA bus operations.131

Subtitle B

further requires public entities operating fixed route systems to supplement that service with a

paratransit system if the general service is not equally accessible to persons with disabilities.132

124

42 U.S.C 12141-12165 (2013). 125

Id. Because the current focus is on the operation of taxicab companies which utilize passenger vehicles, Subpart

II is wholly inapplicable. To be considered in this section is the relevance of Subpart I only. 126

42 U.S.C 12141-12150 (2013). 127

42 U.S.C 12141(2) (2013). Defined as any means of transportation, other than public school transportation, by

bus, rail, or any other conveyance, other than transportation by aircraft or intercity or commuter rail, that provides

the general public with general or special service on a regular and continuing basis. 128

42 U.S.C. 12141 (2013). 129

42 U.S.C. 12144 (2013). 130

42 U.S.C 12141 (2013). 131

MBTA, http://www.mbta.com/schedules_and_maps/ (last visited Mar. 9, 2013). The MBTA operates the public

transportation system in Boston, Massachusetts which is comprised of subway, commuter rail, bus, and boat

services. 132

42 U.S.C. 12143 (2013).

http://www.mbta.com/schedules_and_maps/

-

30

The Ride133

is an example of this type of supplemented public transportation service specifically

for persons with disabilities who cannot use the general MBTA transportation system.

Allegations of discrimination can be brought against a public entity that operates a fixed

route system if, when acquiring new vehicles, it does not purchase or lease new buses, new rapid

rail vehicles, new light rail vehicles, or any other new vehicles that are readily accessible to

persons who use wheelchairs.134

All used vehicles acquired by a public entity operating a fixed

route system must be readily accessible to persons who use wheelchairs unless, a good faith

effort is shown that this was not possible.135

Except for certain historic vehicles, vehicles on a

fixed route system, which are remanufactured to extend their useful life five years or more, could

be considered discriminatory unless, to the maximum extent feasible, they are readily accessible

for persons who use wheelchairs. Again, this section applying to public entities operating a fixed

route system or a fixed route system supplemented with a paratransit system is not likely to apply

to taxicab companies for two reasons: (1) most taxicab companies would not be considered

public entities, and (2) taxicab companies do not operate on a fixed route.

B. TITLE III: PROHIBITION OF DISCRIMINATION BY A PLACE OF PUBLIC

ACCOMMODATION

Title III of the ADA states [n]o individual shall be discriminated against on the basis of

disability in the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages,

133

RIDE THE T, http://www.mbta.com/riding_the_t/accessible_services/default.asp?id=7108 (last visited Jan. 24,

2013). The Ride, paratransit service, provides door-to door, shared-ride transportation to eligible people who

cannot use general public transportation all or some of the time, because of a physical, cognitive or mental

disability. 134

42 U.S.C 12142(a) (2013). 135

42 U.S.C. 12142(b) (2013). To establish good faith effort, a public entity must show that:

(1) the initial solicitation for used vehicles made by the public entity specifying

that all used vehicles were to be accessible to and usable by individuals with

disabilities, or, if a solicitation is not used, a documented communication so

stating; (2) a nationwide search for accessible vehicles, involving specific

inquiries to manufacturers and other transit providers; and (3) advertising in

trade publications and contacting trade associations.

-

31

or accommodations of any place of public accommodation by any person who owns, leases (or

leases to), or operates a place of public accommodation.136

As a general rule, no person can be

discriminated against on the basis of a disability in the full and equal enjoyment of specified

transportation services.137

Therefore, under Title III the DPC will have the most compelling

arguments for meaningful access to taxicabs. Under Title III, the DPC may bring separate claims

to bolster its case under 12182 Prohibition of Discrimination by Public Accommodation and

under 12184 Prohibition of Discrimination in Specified Public Transportation Services

Provided by Private Entities. There is a possibility that if the DPC was able to bring a claim

under 12184, they would be unable to bring a claim under 12182. However, there is strong

evidence that the DPC will be able to pursue a claim under 12184, as taxicabs are a

specified public transportation service provided by a private entity that is primarily engaged

in the business of transporting people and whose operations affect commerce.138

1. Public Accommodations

The purpose of Title III is to extend the general prohibitions against discrimination to

privately operated public accommodations and to bring individuals with a disability into the

economic and social mainstream of American life.139

In general, it is discriminatory to subject

an individual with a disability directly, or through contractual, licensing, or other arrangement to

the denial of an opportunity to participate in or benefit from a service that is not equal and

afforded to other individuals.140

136

42 U.S.C. 12182(a) (2012). 137

Id. 138

Id. 139

H.R. REP. 101-485 at 1 (1990). 140

42 U.S.C. 12182(b)(l)(A)(i) (2012).

-

32

Private entities are considered public accommodations if: (1) the operations of the entities

affect commerce, and (2) if those operations are one of the twelve places or services specifically

outlined in the ADA.141

Although the list of twelve services may appear limiting, the Senate

Committees report notes that many of the enumerated public accommodations include a list of

examples and then the phrase other similar entities.142

In doing so, it was Congress intent for

these sections to be construed as liberally consistent with the intent of the legislation that persons

with disabilities should have equal access to establishments and services as individuals who do

not have disabilities.143

In National Association of the Deaf v. Netflix, Inc., the plaintiff sued Netflix for not

providing closed captioning service in conjunction with its Internet media streaming service.144

The United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts held that Internet media

streaming was a private entity providing a public accommodation.145

The court found that video

streaming was a place of public accommodation because it is a service establishment under the

141

Under 42 U.S.C. 12181(7) the twelve places of public accommodation are:

(1) an inn, hotel, motel, or other place of lodging, except for an establishment

located within a building that contains not more than five rooms for rent or hire

and that is actually occupied by the proprietor of such establishment as the

residence of such proprietor; (2) a restaurant, bar, or other establishment serving

food or drink, (3) a motion picture house, theater, concert hall, stadium, or other

place of exhibition or entertainment, (4) an auditorium, convention center,

lecture hall, or other place of public gathering, (5) a bakery, grocery store,

clothing store, hardware store, shopping center, or other sales or rental

establishment, (6) a laundry mat, dry-cleaner, bank, barber shop, beauty shop,

travel service, shoe repair service, funeral parlor, gas station, office of an

accountant or lawyer, pharmacy, insurance office, professional office of a health

care provider, hospital, or other service establishment, (7) a terminal, depot, or

other station used for specified public transportation, (8) a museum, library,

gallery, or other place of public display or collection, (9) a park, zoo,

amusement park, or other place of recreation, (10) a nursery, elementary,

secondary, undergraduate, or postgraduate private school, or other place of

education, (11) a day care center, senior citizen center, homeless shelter, food

bank, adoption agency, or other social service center establishment, and (12) a

gymnasium, health spa, bowling alley, golf course, or other place of exercise or

recreation. 142

H.R. REP. 101-485 at 100 (1990). 143

Id. 144

National Assn of the Deaf v. Netflix, Inc., 869 F. Supp. 2d 196, 201 (D. Mass 2012). 145

Id.

-

33

ADAs enumerated listing.146

The court also noted Congress intent to liberally construe these

sections in providing equal access to those persons with a disability.147

Netflix provides persuasive precedent for the First Circuit Court, which has jurisdiction

over Massachusetts. A taxicab service could be deemed a public accommodation under the

description of a service establishment,148

which is not defined directly in the ADA but further

interpreted by Netflix.149

The First Circuit, as in Netflix, seems to adopt a progressive view

towards public accommodations. However, defining taxicab service as a public accommodation

under the service establishment provision has not yet been tested in the Massachusetts courts.

If taxicabs were deemed a service establishment, there would be more compelling evidence for a

discrimination claim under Title III of the ADA.

On the assumption that a taxicab would qualify as a service establishment, the DPC

must show that the taxicab service has been discriminatory in some fashion.150

The public

accommodation section of Title III lists five specific discriminatory prohibitions for those areas

that are public accommodations:

(1) Eligibility criteria that screens out an individual,

(2) Failure to make reasonable modifications in policies, practices,

or procedures when necessary for an individual with a disability,

(3) Failing to take steps as may be necessary to insure no

individual with a disability is excluded, denied, services,

segregated, or otherwise treated differently than other individuals,

(4) Failure to remove architectural barriers, communication

barriers, and transportation barriers in existing vehicles where such

removal is readily achievable, and

(5) Where barrier removal are not readily achievable but failing to

make such goods, services, facilities, privilege, advantage, and

146

National Assn of the Deaf v. Netflix, Inc., 869 F. Supp. 2d 196, 201 (D. Mass 2012); 42 U.S.C. 12181(7)(F)

(2013). 147

National Assn of the Deaf v. Netflix, Inc., 869 F. Supp. 2d 196, 201 (D. Mass 2012). 148

42 U.S.C. 12181(7)(F) (2012). 149

Id. 150

42 U.S.C. 12182(b)(2)(A) (2013).

-

34

accommodation if alternative methods are readily achievable.[151]

Taxicab services may discriminate based on one or more of the specified prohibitions.

Since taxicabs with wheelchair accessibility is not the standard, the private entity which

operates a public accommodation is failing to take steps as may be necessary to ensure no

person with a disability is excluded, denied services, segregated, or otherwise treated differently

than other individuals.152

Furthermore, the taxicab services are discriminatory because of their

failure to remove transportation barriers in existing vehicles where such removal is readily

achievable.153

Current vans owned and operated by the taxicab companies, can be customized to

accommodate and serve persons with disabilities.154

For purposes of 12182, a public accommodation includes a demand responsive system

not covered under 12184 as a specified public transportation service.155

It is unclear whether

this provision would preclude a claim related to a demand responsive system altogether under

12182 public accommodation. If 12184 applies to the demand responsive system, it may

nullify the taxicab service establishment argument.

In summary, a taxicab service could be a private entity that operates as a service

establishment and is deemed a public accommodation. Should this proposition hold true, there

are at least two discrimination provisions that could apply in a suit filed against the taxicab

industry. The first discrimination provision would be used to highlight the taxicab companies

failure to take the appropriate steps to avoid excluding or denying service to persons with

disabilities. The second discrimination provision would be used to state that the taxicab

companies are failing to remove transportation barriers to persons with disabilities. The

151

42 U.S.C. 12182(b)(2)(A) (2012). 152

42 U.S.C. 12182(b)(2)(A)(iii) (2012). 153

42 U.S.C. 12182(b)(2)(A)(iv) (2012). 154

WHEELCHAIR MINI VANS AND MANUFACTURERS, http://www.nmeda.com/what-to-buy/mini-vans (last visited

Mar. 9, 2013). 155

42 U.S.C. 12182(b)(2)(C) (2012). See analysis infra Part II.B.3.

http://www.nmeda.com/what-to-buy/mini-vans

-

35

arguments may demonstrate how taxicab companies in Massachusetts are discriminatory as

public accommodations and may result in a favorable judicial proceeding for the DPC.

2. Public Accommodation under Massachusetts Laws

Massachusetts expands the meaning of a place of public accommodation in 272 MLGA

92A.156

Most claims brought under 92A are made in tandem with 272 MLGA 98.157

This

section gives the Commonwealth the power to penalize those who violate 92A and will be

discussed further in the Section III.158

Under 92A the Commonwealth defines a place of public

accommodation as a place that accepts patronage of the general public and includes a carrier

used to transport persons.159

Furthermore, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) consistently holds that the

statute must be given a broad, inclusive interpretation in order to achieve its remedial goal of

eliminating and preventing discrimination.160

This is a positive reaction from the Massachusetts

SJC expanding the ADA, showing that the First Circuit interprets the ADA more broadly than

New York in the Second Circuit. Additionally, it must be noted that one of the cases making the

assertion to a broad interpretation was decided in 1968, twenty-two years before the ADA was

enacted.161

This shows that Massachusetts continues to be a reform state and ahead of the federal

156

MASS. GEN. LAWS 272, 92A states:

A place of public accommodation, resort or amusement within the meaning

hereof shall be defined as and shall be deemed to include any place, whether

licensed or unlicensed, which is open to and accepts or solicits the patronage of

the general public and, without limiting the generality of this definition, whether

or not it be (2) a carrier, conveyance or elevator for the transportation of

persons, whether operated on land, water or in the air, and the stations, terminals

and facilities appurtenant thereto 157

See Concord Rod & Gun Club, Inc. v. Mass. Comm'n Against Discrimination, 402 Mass. 716, 720 (1988); See

Local Fin. Co. v. Mass. Commn Against Discrimination, 355 Mass. 10, 12 (1968). 158

MASS. GEN. LAWS 272, 98 (2012); See infra Part III. 159

MASS. GEN. LAWS 272, 92A (2012). 160

Concord Rod & Gun Club, Inc. v. Mass. Comm'n Against Discrimination, 402 Mass. 716, 720 (1988); See Local

Fin. Co. v. Mass. Commn Against Discrimination, 355 Mass. 10, 13 (1968). 161

Local Fin. Co. v. Mass. Commn Against Discrimination, 355 Mass. 10 (1968).

-

36

law. This further indicates that it could be the state leading the way for finding that taxicabs

discriminate when they are not wheelchair accessible.

3. Section 12184: Specified Public Transportation Services Provided by Private

Entities

a. Parts (b)(3) & (5)

A demand responsive system owned by a private entity is discriminating under Title III if

it fails to either upgrade or buy new vehicles; however, it specifically removes automobiles from

such requirement:

The purchase or lease by such entity of a new vehicle (other than

an automobile, a van with a seating capacity of less than 8

passengers, including the driver, or an over-the-road bus) which is

to be used to provide specified public transportation and for which

a solicitation is made after the 30th day following the effective

date of this section, that is not readily accessible to and usable by

individuals with disabilities, including individuals who use

wheelchairs; except that the new vehicle need not be readily

accessible to and usable by such individuals if the new vehicle is to

be used solely in a demand responsive system and if the entity can

demonstrate that such system, when viewed in its entirety,

provides a level of service to such individuals equivalent to the

level of service provided to the general public [emphasis

added].[162]

This provision imposes a significant barrier. However, Title III does not treat vans that

hold less than eight passengers in the same category as automobiles.163

The purchase or lease of

a new van by a taxicab company must be accessible to or usable by persons with disabilities

unless the provider can show that the system, when viewed in its entirety, provides equivalency

of service:

The purchase or lease by such entity of a new van with a seating

capacity of less than 8 passengers, including the driver, which is to

be used to provide specified public transportation and for which a

162

42 U.S.C. 12184(b)(3) (2012). 163

42 U.S.C. 12184(b)(5) (2012).

-

37

solicitation is made after the 30th day following the effective date

of this section that is not readily accessible to or usable by

individuals with disabilities, including individuals who use

wheelchairs; except that the new van need not be readily accessible

to and usable by such individuals if the entity can demonstrate that

the system for which the van is being purchased or leased, when

viewed in its entirety, provides a level of service to such

individuals equivalent to the level of service provided to the

general public.[164]

This second provision could prove more useful than the first for Massachusetts taxicab reform.

The provision applies only to those entities that provide specified public transportation.165

Although not all taxicabs are vans, the DPC may advocate for a larger taxicab fleet of vans. This

would bring the new taxicab vans under the Title III requirements and would therefore have to be

wheelchair accessible.166

Furthermore, the aforementioned provision states that these new vans must be readily

accessible to, or usable by, persons with disabilities.167

Therefore, before bringing a claim under

this provision, the DPC must look at how the court has interpreted new within the meaning of

the statute. Depending on the definition of new, a taxicab company may be able to avoid the

implication of the Title III purchase requirements by merely acquiring vans that are previously

used or will be forced to purchase vehicles that have been manufactured after 1990 that are

wheelchair accessible.168

In 2006, the question of what a new van was, for purposes of the

second provision, found its way to the court.169

In Toomer v. City Cab, a disability rights

organization in the Tenth Circuit argued that new should be defined as any vehicle

164

42 U.S.C. 12184(b)(5) (2012). 165

42 U.S.C. 12181(10). The ADA notes that specified public transportation means transportation by bus, rail, or

any other conveyance (other than by aircraft) that provides the general public with general or special service

(including charter service) on a regular and continuing basis. 166

42 U.S.C. 12184(b)(5) (2012). 167

Id. 168

49 C.F.R. 37.3 (2011). The DOT defines a new vehicle as one which is offered for sale or lease after

manufacture without any prior use. 169

Toomer v. City Cab, 443 F.3d 1191 (10th Cir. 2011).

https://a.next.westlaw.com/Link/Document/FullText?findType=L&pubNum=1000547&cite=49CFRS37.3&originatingDoc=Id9196984c45011da8d25f4b404a4756a&refType=LQ&originationContext=document&transitionType=DocumentItem&contextData=(sc.UserEnteredCitation)

-

38

manufactured after the passage of the ADA.170

The defendants, a group of local taxicab

companies, argued that the definition of new should mean, not previously used.171

The court

focused its attention on the statutory language of the relevant ADA provision, noting [t]he ADA

does not mandate that all private transportation entities provide accessible vehicles a taxi fleet

consisting entirely of non-accessible vehicles would be in accord with the ADA.172

The court

also relied heavily upon the DOT definition of a new vehicle.173

Furthermore, the court

stipulated that as an agency that had been delegated authority by Congress, the DOT had the

institutional competence to define new vehicle as it appeared in the ADA.174

In the end, the

court found in favor of the taxicab companies and held that new merely meant not previously

used.175

There is a gaping loophole when purchasing these new vehiclesother than

automobilesas taxicab service providers could choose to purchase used vehicles, only a few

years old, and avoid the accessibility requirement altogether. However, the court added that if

taxicab companies are exploiting this gaping loophole it should be left to Congress to address

it, not the courts.176

This could be a barrier to bringing a case in the First Circuit challenging the

definitional loophole. The DPC could pursue the litigation strategy in the First Circuit under a

similar theory since a more progressive viewpoint is possible.

b. Parts (b)(1) & (2)

170

Id. at 1194. 171

Id. 172

Id. at 1195. 173

Id. 174

Id. 175

Id. 176

Id. at 1197.

-

39

The following claims vary in strength and persuasiveness. Following a litigious route for

claims 12184(b)(1) and (b)(2) would require aggressive advocacy.177 It is our contention that

there is a reasonable claim available to the DPC under 12184(b)(1) of Title III.178

In order to

win on a claim for a violation under 12184(b)(1) against a taxicab company, it seems a plaintiff

in a wheelchair would need to show that the taxicab company: (1) used eligibility criteria, (2) the

criteria screened out on the basis of their disability, and (3) the criteria is not necessary for the

provision of the service.179

Based on the case law interpretation of the statute, the DPC could argue that a driver of a

sedan taxicab, by definition, uses (1) eligibility criteria to exclude persons in wheelchairs, as

motorized wheelchairs cannot fit in a sedan. This presents an obstacle to the DPC because it is

subjective to the opinions of the driver. As in Emery v. Caravan of Dreams, Inc., criteria

implies an active or conscious decision, which is also subjective to the driver.180

To avoid this

obstacle, the DPC may bring a claim against a taxicab company that only dispatches sedans. In

such a case, the eligibility criteria could be more easily construed as a policy, like in

Guckenberger v. Boston University, where students with learning disabilities claimed that

177

42 U.S.C. 12184(b)(1) (2013) states:

the imposition or application by a [an] entity described in subsection (a) of