GTAA Noise Management Benchmarking Study · GTAA Noise Management Benchmarking Study. ... Francisco...

Transcript of GTAA Noise Management Benchmarking Study · GTAA Noise Management Benchmarking Study. ... Francisco...

Management and technology consultants

Final report Annex C - Detailed summary of research

Version 1.5 (FINAL), 24th September 2017

GTAA Noise Management Benchmarking Study

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Contents

Quieter fleet initiatives 2

Runway schemes 10

Night flight restrictions 22

Noise abatement procedures 33

Ground and gate operations 46

Land use planning 53

Noise complaints 65

Community outreach 82

Noise ombudsman 91

Fly Quiet programmes 96

Reporting of noise monitor data 106

1

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Introduction

Most airports have some form of measures to either limit

the use of the noisiest aircraft types or encourage the use

of quieter fleets. These measures can be in the form of

restrictions on certain types of aircraft (typically at night),

incentive schemes, voluntary arrangements and comparing

fleet mix between airlines.

Typical practices

Operating restrictions: These involve restricting the

operation of certain (older/noisier) aircraft types, typically at

night. These are usually based on the noise

certification/Chapter number of aircraft types according to

the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO).

Noise based charging schemes: It is common in Europe

for airports to assign a noise element to the landing and/or

take-off charge. Lower noise charges are levied on ‘quieter’

aircraft to incentivise their use. Again, these charges are

usually related to the certified noise level of an individual

aircraft or its ICAO Chapter.

A320 modification programmes: A relatively new

initiative is addressing the ‘whine’ generated Airbus A320

family of aircraft on approach. The aircraft have small vents

on each wing designed to help equalise the fuel pressure in

the intra wing tanks. When air rushes past the vents it

creates a high pitched ‘whine’ which can cause up to 6dB

“extra” noise. There is a simple modification (vortex

generator) which can resolve the issue and some airports

have undertaken voluntary and financially incentivised

initiatives to encourage airlines to modify the aircraft.

Special and unique practices

Incentives to replace older aircraft: Zurich and

Amsterdam Schiphol were found to have offered financial

incentives to airlines to replace older noisier aircraft.

Fly Quiet programmes: A small number of airports have

Fly Quiet programmes which publicly compare airlines

across a variety of noise metrics. Two of these airports

(Heathrow and San Francisco) have fleet metrics as a

means to encourage airlines to operate the quietest fleet

possible for a given type of operation.

Regional trends

Operating restrictions are the only initiative commonly

applied by airports across the world. Financial

mechanisms, such as noise based charging and incentives

are primarily applied in Europe

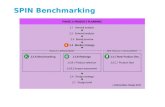

Quieter fleet initiatives - Overview

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Quieter fleet initiatives - Best practice from around the world

4

• Gatwick, Heathrow and Frankfurt incentivise

A320 retrofit through either voluntary

schemes or through additional charging.

• Noise based charging (or a noise factor in the

charge) is the norm for European airports – it

is either based on certified or measured

noise. There is a 10X difference at Heathrow

between loudest and quietest aircraft.

• Chapter 2 aircraft are banned at European

airports.

• Airports such as Charles de Gaulle and

Frankfurt limits the operation of marginally

compliant chapter 3 and Chapter 3 aircraft in

the overnight period.

• Heathrow has included aircraft chapter within

the Fly Quiet program.

• Incentive schemes for quieter aircraft have

been used at Zurich and Schiphol, rewards

are applied per arrival or departure if

marginally compliant chapter 3 aircraft are

replaced.

• Charges are mainly based

on weight.

• 40% discount is applied at

Changi to incentivise night

flights.

• Only Chapter 3 or better

aircraft are permitted.

• Charging is largely based on MTOW or PAX.

• Chapter 2 aircraft are largely banned. At

Montreal, Chapter 3 and 4 aircraft are

restricted during the night.

• Forums at Chicago O’Hare, LAX and San

Francisco jointly engaged with United Airlines

on the ‘whine’ generated by A320 aircraft.

• Softer schemes in operation, such as the MD-

80 phase out at O’Hare.

• Noise is not part of the charging scheme.

• Chapter 2 aircraft are banned at US airports.

• John-Wayne has restrictions based on the

actual noise output of aircraft on arrival and

departure.

• Only Chapter 3 or better

aircraft are permitted to

operate from Dubai.

• Charges are based on aircraft weight – Sydney

used to operate a night noise levy but this has

now ceased.

• Only Chapter 3 aircraft or better are allowed.

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Overview of research

Operating restrictions limit the use of certain (older/noisier)

aircraft types, either throughout the day or at sensitive

times of day such as the night. The key findings from the

research were:

• Almost all airports researched specify that Chapter 2

aircraft (according to ICAO Annex 16) are banned from

operating.

• At Amsterdam Schiphol aircraft that are marginally

compliant with Chapter 3 standards by < 5 EPNdB are

subject to restrictions at night:

• Aircraft with engine bypass ratio > 3 (typically commercial aircraft)

are not allowed to operate between 2200-0600

• Aircraft with engine bypass ratio < 3 are not allowed to operate

between 1700-0700

• Paris Charles de Gaulle restricts aircraft that are

marginally compliant with Chapter 3 standards:

• Aircraft compliant by < 5 EPNdB are banned

• Aircraft compliant by < 10 EPNdB are not allowed to take off or

land between 2200-0600

• Frankfurt does not allow the operation of marginally

compliant Chapter 3 aircraft 1900-0700 on weekdays and

does not allow their operation at the weekend (between

1900 on Friday to 0700 on Mondays).

• Montreal does not allow Chapter 3 and 4 aircraft over 45

tonnes to land between 0100-0700 or take off between

0000-0700 .

• New York (JFK) and John Wayne airports are subject to

movement limits. JFK is limited to 81 movements per hour

between 0600-2259

• Brussels, Heathrow, Gatwick and Madrid apply night-

time quota schemes which restrict the operation and/or

scheduling of aircraft in the noisiest aircraft categories at

different times of the night (quota schemes are

explained the night flight restrictions section)

Quieter fleet initiatives – Operating restrictions

5

ICAO Annex 16, Volume I, Aircraft Noise, front cover

Source:

http://www.icao.int/secretariat/PostalHistory/annex_16_environmental_protec

tion.htm

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Overview of research

Noise based charging schemes

It is common in Europe for airports to assign a noise

element to the landing and/or take-off charge. Lower noise

charges are levied on ‘quieter’ aircraft to incentivise their

use. Again, these charges are usually related to the

certified noise level of an individual aircraft/its ICAO

Chapter.

Charges are often also increased further at night as a

further incentive for airlines to operate quieter aircraft.

As summary of the findings in this areas are as follows:

• 8 of 26 airports in the study (all in Europe) employed

some form of noise based charge in their charging

schemes.

• Sydney airport did have a noise levy in place from 1996

but it was repealed in 2005.

• Hong Kong airport are investigating whether noise

based charging is appropriate for them.

• New York (JFK) have increased charges between 3pm

and 10pm for unscheduled/private aircraft.

• Although not an airport within the scope of the study,

Tokyo Narita airport has recently introduced a noise

based charge.

Case studies of noise-based charging schemes are given

in the following pages.

Financial incentives

Two examples were found of airports using financial

incentives to encourages airlines to replace older aircraft:

Zurich and Amsterdam Schiphol were found to have

provided direct financial incentives to airlines (or in the

case of Amsterdam cargo operators). Both schemes

focussed on incentives to replace ‘noisier’ aircraft with a

‘quieter’ one.

The Zurich scheme encouraged operators to put a quieter

aircraft (a minimum 5 dB reduction is required over the

previous aircraft type) on one of its existing routes through

reductions in landing charges for up to 3 years.

Amsterdam Schiphol operates a Cargo Sustainability

Incentive Programme to stimulate the use of quieter cargo

aircraft. Airlines are incentivised to replace their Marginally

Compliant Chapter 3 (MCC3) dedicated freighter flights

with quieter wide body dedicated freighter aircraft.

Qualifying airlines are eligible for a reward of € 400 per

departure during the first year of operation with the new

aircraft.

Quieter fleet initiatives – Financial mechanisms

6

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Case study – Heathrow charging scheme

Heathrow has a noise element in its landing charges. For

aircraft over 16 metric tonnes there are 6 charging

categories based upon ICAO Chapter numbers (see the

top table to the right).

In addition, charges differ depending on whether an aircraft

lands during the day or at night. The top table to the right

shows that charges increase by a factor of almost 12 from

the quietest (Chapter 14 Low) aircraft, to the loudest

(Chapter 3).Charges are further increased by a factor of 2.5

for each category between 0100 and 0430.

The second table describes the qualification criteria for

categorising aircraft. The criteria are based on the

cumulative reduction in Effective Perceived Noise level

(EPNdB*) compared to the ICAO Chapter 3 standard. This

information must be provided to the airport in order to

calculate the appropriate charge.1

* The EPNdB metric represents the average sound level in

decibels over a 10 second period. A 10dB reduction is equivalent

to halving the sound level.

1. http://www.heathrow.com/file_source/Company/Static/PDF/P

artnersandsuppliers/Conditions-of-Use_2017.pdf

Quieter fleet initiatives - Noise based charging schemes

7

Heathrow conditions of use. Source:

http://www.heathrow.com/file_source/Company/Static/PDF/Partnersandsuppliers/Con

ditions-of-Use_2017.pdf

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Case study – Schiphol charging scheme

Amsterdam Schiphol also used aircraft certified noise

levels to categorise them into different charging bands

(see top table to the right).

A noise factor of between +60% and -20% is applied to the

basic compensation/charge (a unit charge per 1,000kg –

see table below) depending on the aircrafts noise

classification. An additional charge is also levied during the

night period (2300-0600). For the noisiest aircraft types

(marginally compliant Chapter 3 (MCC3)), charges

approximately double during the night.

Schiphol airport also states that where aircraft do not

provide evidence of their noise certification, they will be

allocated into a category by the airport based on their type.

This approach is termed the “conservative classification of

noise categories” (see table) since the classification is

based on the most unfavourable configuration of a given

type.

Quieter fleet initiatives - Noise based charging schemes

8

Schiphol “Conservative classification of noise categories” 01/04/2016 (for those

aircraft which do not have noise certification available)

Source: https://www.schiphol.nl/en/route-development/page/ams-airport-

charges-levies-slots-and-conditions/

Noise

category

Cumulative reduction in

EPNdB

Description

MCC3 0 ≥ change in EPNdB ≥ -5 Marginally compliant chapter 3

A -5 ≥ change in EPNdB > -9 Relatively noisy aircraft

B -9 ≥ change in EPNdB > -18 Average noise producing aircraft

C -18 ≥ change in EPNdB Relatively low noise aircraft

Noise categories at Amsterdam Schiphol airport

Source: https://www.schiphol.nl/en/route-development/page/ams-airport-charges-levies-

slots-and-conditions/Noise categories at Amsterdam Schiphol airport

Source: Setting_Charges___Conditions_1_April_17_.pdf

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Overview of research

6 of the 26 airports researched had undertaken some form

of initiative to encourage A320 operators to modify the

aircraft to alleviate the ‘whine’ generated when the aircraft

is on approach to land (see the introduction page to this

section for further information).

In May 2016, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Chicago

O’Hare airports submitted letters to United airlines via their

community round table groups. In December 2016, United

agreed to install vortex generators on its aircraft. 13 aircraft

were to be retrofit by early 2017 and subsequent aircraft at

a rate of 2 per month.

Heathrow airport publicly states that they encourage

airlines to retrofit their A320 fleets but no specifics were

identified.

Frankfurt and Gatwick modified the noise element of their

landing/take-off fees to encourage airlines to modify the

A320. For the noise element of its landing/take-off charges,

Frankfurt categorises aircraft into one of 15 charging bands

based upon certified noise levels. An A320 that has been

modified to remove the ‘whine’ falls into a different (less

expensive) band than its unmodified counterpart.

Gatwick created a separate charging category for

unmodified A320 family aircraft (see case study opposite).

Case study – Gatwick modified charging scheme

As part of an independent review of arrivals in 2016, it was

recommended that the airport introduce an A320

modification incentive scheme. Following a period of

consultation with airlines, it was decided that a higher noise

charge would be introduced for unmodified aircraft from 1st

January 2018 to give operators a chance to modify their

fleets. The table below shows that unmodified A320s will

be subject to the highest noise charges during both the day

and night.

The airport informed airlines of these changes and

continues to liaise them through requests of quarterly

updates of their A320 modification programmes.

Quieter fleet initiatives - The A320 modification program

9

Season Charge category Charging unit Day Night

Summer

(1 April - 31

October)

Unmodified A320 family per movement £784.40 £988.02

Chapter 3 & below per movement £78.44 £988.02

Chapter 4 per movement £39.22 £494.01

Chapter 14 High per movement £23.53 £296.41

Chapter 14 Base per movement £19.61 £247.00

Chapter 14 Minus per movement £15.69 £197.60

Winter

(1 November - 31

March)

Unmodified A320 family per movement £784.40 £988.02

Chapter 3 & below per movement £0.00 £988.02

Chapter 4 per movement £0.00 £494.01

Chapter 14 High per movement £0.00 £296.41

Chapter 14 Base per movement £0.00 £247.00

Chapter 14 Minus per movement £0.00 £197.60

Gatwick Unmodified A320 family noise charge – effective 1st January 2018, Source:

https://www.gatwickairport.com/globalassets/publicationfiles/business_and_community/all_

public_publications/2017/2017-18-conditions-of-use---final---sent-30jan17.pdf

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Introduction

In order to ensure safe take-off and landing, aircraft normally

land and take-off into the wind and air traffic control will

select the runway direction based upon current and forecast

weather conditions to facilitate this.

Runway schemes

At airports with multiple runways, preferred runway

directions for take-off and landing are often nominated for

noise abatement purposes, the objective being to utilize

whenever possible those runways that permit aircraft to

avoid noise-sensitive areas during the initial departure and

final approach phases of flight1.

Use of runway schemes

Of the 26 airports researched, most operate some form of

runway scheme for noise management purposes. The

exceptions were in the Middle East.

Day-time and night-time runway schemes

Both day and night-time runway schemes are common.

Night-time schemes are more widely used as this is both a

more noise sensitive period of the day, and airports are able

to operate their runways with increased flexibility at night

when traffic levels are lower.

Types of runway schemes

The type of schemes operated varied considerably,

reflecting the influence of several local factors –

geographical location, location relative to populations and

the number/orientation of runways. Each broadly aimed to

either provide some form of predictability of flight path use,

focussing overflight over sparsely populated/unpopulated

areas and/or sharing noise. For the reasons stated earlier,

schemes operated at night tended to apply more ingenious

solutions.

Conformance with runway schemes

Factors such as weather, traffic demand, safety, pilot

preferences and runway maintenance make it very difficult

to provide 100 percent conformance with any runway

scheme. For this reason a number of airports state that they

will apply their runway schemes voluntarily or ‘where

possible’.

Reporting on runway schemes

The majority of airports do not report on the level of

compliance with their runway schemes.

Runway schemes – Overview

11

1 ICAO PANS-OPS Volume 1 - Section 2.1 Noise Preferential Runways

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Runway schemes - Best practice from around the world

12

• Almost all airports make use of runway schemes to

provide respite. However in some areas it’s used to

deliver capacity benefits (Frankfurt and Charles de

Gaulle).

• Schemes are either based upon fixed time (daily or

weekly) rotations (Brussels, Zurich and Heathrow)

or use a number of factors. Amsterdam uses

software to share noise by assessing the potential

noise impacts, traffic mix and metrological

conditions.

• Schemes are typically the same during the night

although some airports do not allow use of certain

runways during the night (Amsterdam, Madrid).

• Runway usage is reported by Heathrow, Gatwick

and Charles de Gaulle. However, Heathrow is the

only airport that reports departure runway

adherence.

• Changi and Hong Kong

attempt to push departures

away from residential areas by

using the runway closest to the

water for departures, with

arrivals on the closest runway.

• In Changi this only applies in

the early morning.

• Runways schemes used to divert traffic over low population

areas.

• Night time runway schemes typically operate between 2300 and

0600. Usually based on preferred operational direction

(Vancouver) or set list of runways (Calgary, Montreal, Toronto).

• Only Vancouver and Montreal report on runway usage in annual

or directors reports.

• Runways schemes are not typically used

during the day. Only Hartsfield Jackson

(Atlanta) states that the 4 northern runways

should be used between 0700 and 2200.

• O’Hare recently undertook a night-time

runway use rotation trial to vary runway use

on a 12 week rotation.

• Tendency to make use of ‘inner’ runways

during the night period.

• Voluntary night time runway schemes are

used between 2200 and 0700. The protocol

is designed to direct aircraft over water (Los

Angeles, San Francisco).

• Where runway schemes are used, runway

usage is reported in figures and maps in the

applicable time period.

• No information available

on runway schemes.

• Sydney has an aspirational Long Term Operational Plan

(LTOP) which aims to share traffic and drive traffic over

water where possible.

• In Auckland, opposite runway directions (landing and

take-offs nose to nose) are used to drive traffic over

water during the night.

• Sydney reports on runway usage through an online

community tool which is required to report performance

against the LTOP.

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Overview of research

Of the 26 airports researched, most operate some form of

runway scheme for noise management purposes.

Day and night-time runway schemes

As shown in the chart above, night-time runway schemes

were more common than their day-time counterparts. This

reflected both the night-time being a more noise sensitive

period of the day, and airports being able to be more

flexible with the operation of their runways at night when

traffic levels are much lower. Two airports, Paris Charles

de Gaulle and Frankfurt, had protocols but these are not

specifically used for noise management.

Night-time runway schemes typically start around 2300 and

end around 0600 (see chart on page 16).

Types of runway schemes

The type of schemes operated varied considerably

reflecting the influence of several local factors and

examples are given below, these are supported by case

studies in the following pages. In many cases combinations

of the examples below were used at a given airport:

• Prioritised list of preferential runways: Many airports,

publish an order of priority for runway use. If conditions

such as weather are satisfied, the first preference runway

combination is used. If conditions are not satisfied, the

second preference is used and so on (see Amsterdam

Schiphol case study).

• Fixed timetable for runway usage: In this example,

airports had a timetable stating the preferred runways to be

used at certain hours of the day. These aimed at providing

those under the flights paths with a degree of predictability

of when they would be overflown (see Zurich case study).

(Continued on the next page)

Runway schemes – Overview & types of runway schemes

13

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

Day protocol Night protocol Publicly reported onprotocol

Num

be

r o

f a

irp

ort

s a

pp

lyin

g

the

pro

toco

l

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

• Directing traffic over the least populated areas: These

examples aimed at focussing the use of runways for arriving

and departing aircraft on the least populated areas. In

particular, airports with a coastal location try to fly as many

aircraft as possible of the sea (see Sydney Case study). At

night, when traffic levels were lower, a number of this airports

aimed to have both arriving and departing aircraft operating

over the sea i.e. landing and departing in opposite directions.

(see Auckland and Vancouver case studies).

• Rotating timetable for runway usage: Similar to the

example above, but with a timetable that rotated, typically on

a weekly basis. As well as providing those under the flights

paths with a degree of predictability of when they would be

overflown, it also aimed to ensure that overflight did not occur

at the same time every day (see Chicago O’Hare and

Heathrow case studies).

• Use of runways furthest from populated areas: During the

day-time, Los Angeles, with its four parallel runways, where

practicable, aims to operate arriving aircraft on the outer

runways (closest to populations) and departure operations,

which are noisier than arrivals, on the inner runways (furthest

from populations). At night, the aim is to maximise the use of

the inner runways for both arriving and departing aircraft.

Similarly, other airports focus night-time operations on the

runway furthest from populations (see Vancouver case study).

• Long-term noise sharing: This approach aims to achieve

some form of equitable sharing of noise over an extended

period of time – for example the amount of overflight certain

areas will receive over a given period of time. The main

example of this is Sydney airport which sets targets for the

proportion of aircraft arriving/departing from/to the north, east,

south and west of the airport (see Sydney case study).

Runway schemes – types and limitations

14

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Conformance with runway schemes

Research identified that it is very difficult to provide 100

percent conformance with any runway scheme. The level of

conformance can vary quite considerably depending on the

scheme – for example 90 - 95% at Heathrow and 67% at

Chicago O’Hare. There are several factors for this, not all

of which are under the control of the airport. For this reason

a number of airports state that they will apply their runway

schemes voluntarily or ‘where possible’:

• Weather: This includes wind direction/speed and nearby

storms which preclude the use of a preferred runway.

• Traffic demand: Some preferred runway directions can

only be operated during low traffic demand.

• Pilot preferences: Pilots will sometimes request a certain

runway on safety grounds, for example the longest runway

at the airport.

• Emergencies: Use of a ‘non-preferred’ runway in the case

of emergencies.

• Runway inspections & maintenance: Use of another

runway while the preferred runway is being maintained or

inspected.

Reporting on runway operations

Of the 26 airports researched, 8 provided public reports on

usage of runways.

The method and frequency of reporting varied from

monthly, quarterly and annually written reports to daily

online reports as provided by Heathrow.

No clear trends were spotted in the frequency of reporting

periods, however all of the reports provided graphics

showing the percentage use of one particular runway

direction over the reporting period.

Runway schemes – Conformance and Reporting

15

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Runway schemes – Case studies

17

Case Study - between 2300 and 0600, when weather conditions

permit, Vancouver airport makes use of runways which direct both

arriving and departing aircraft over the Strait of Georgia. In addition,

the northern runway (08L/26R) is closed between 2200 and 0700

except in the event of an emergency or maintenance. During the day,

where weather conditions permit, departures are directed towards

the water.

The airport has published a short paper explaining how the protocol

works, the times at which it isn’t possible to use it, and notes the

specific operations which may not follow the protocol such as air

ambulances or police flights.

Reporting on compliance is made within the airport’s annual noise

report and covers 24 hour runway utilisation which is then subdivided

up into operations over the Strait of Georgia. In 2015 the airport

conducted 54% of take-offs over this body of water. There is no

separate reporting of night-time runway operations.

Case Study - Heathrow airport uses a day-time runway alternation

scheme between 0600 and the last departure of the day when

aircraft land from the east/depart to the west (for historical reasons,

the scheme does not apply when aircraft land from the west/depart

to the east). The scheme runs over a two week rotating cycle

throughout the year and aims to provide residents under the flight

paths with a predictable break from noise. During week 1, the

northern runway is used for arriving aircraft until 1500, the southern

runway is then used for arrivals until the end of the day. On week 2,

the pattern is changed, with the southern runway being used for

arriving aircraft until 1500. During 0600-0700 arrivals can use both

runways, and alternation can be broken for safety and emergency

reasons. The airport publishes a yearly schedule outlining the

preferred operational direction and publicly reports daily on the use

of the preferred runway.

The runway in use is also rotated at night on a weekly basis.

Heathrow’s runway

alternation program,

source -

http://www.heathrow.c

om/noise/heathrow-

operations/runway-

alternationDepartures overwater

Arrivals overwater

Vancouver runway operations 2200 to 0700

Closure of Northern runway

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Runway schemes – Case studies

18

Case Study - Amsterdam Schiphol operates both a day-time and

night-time preferential runway scheme. The schemes are based

upon a prioritised list of runway combinations, with the chosen

combination being based upon weather conditions. The daytime

preferences operate from 0600-2230, and the night-time preferences

from 2230-0600. The aim of the scheme is to focus aircraft noise into

least densely populated areas.

The airport makes use of an Environment-Aware Runway Allocation

Advice System developed by NLR, the Dutch National Aerospace

Laboratory. The system is connected to a metrological system and

therefore has up to information on current wind and visibility

conditions. Using a known database of preferential runway

directions, noise management procedures and situational inputs

such as runway availability and the status of navigational aids such

as the ILS, the system can provide recommendations on which

runway to use. The system can also provide forecasts, or what-if

analysis to inform future runway selections.

The system is connected to a wider environmental management

system which allows Schiphol to update the preferential runway

listing in response to runway utilisation. This process allows the

preferential runways to be re-prioritised to meet environmental

targets. The system records data on runway utilisation and this is

provided to communities to ensure transparency.

Runway preferences at Amsterdam Schiphol, Source:

https://www.lvnl.nl/en/environment/route-and-runway-use/runway-

preferences.html

A: Valid 0600 to 2300 hours local

Pref.Runway combinations

ARR 1 ARR 2 DEP 1 DEP2

Required

visibility - and

daylight

conditions

Good visibility

within UDP

1 06 36R 36L 36C

2 18R 18C 24 18L

3 06 36R 09 36L

4 27 18R 24 18L

Good visibility5a 36R 36C 36L 36C

5b 18R 18C 18L 18C

Marginal visibility6a 36R 36C 36L 09

6b 18R 18C 18L 24

B: Valid 2300 to 0600 hours local

Pref.Runway combinations

ARR 1 ARR 2 DEP 1 DEP2

Required

visibility - and

daylight

conditions

Good or marginal

visibility

1 06 - 36L -

2 18R - 24 -

3 36C - 36L -

4 18R - 18C -

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Runway schemes – Case studies

19

Case Study - To investigate the potential benefits from a night

time runway rotation, Chicago O’Hare airport undertook a 25

week operational trial in 2016. The trial rotated the runways in

use at night on a weekly basis. The aim was to reduce noise

impacts at night and provide some predictability to this through a

25-week schedule published at the start of the trial (see extract

below). Each night the trial commenced at either 2200, or a

period thereafter when operations could be supported using a

single runway for arrivals, and a separate single runway for

departures. The trial ended at either 0700 or earlier when traffic

demand dictated.

Throughout the trial the airport tracked runway utilisation, noise

events and feedback using a survey. A public report was

generated at the end of the trial and showed 67% compliance

with the planned schedule. Reasons for non-compliance included

traffic demand at the start end of the night, runway inspections,

weather and pilot requests for specific runways. The airport has

since extend the trial into a second period.Case Study - Zurich airport has adopted a runway scheme

similar to Brussels which shifts traffic based upon time periods,

weekends and holidays as follows:

Case Study - between 2300 and 0600 and in low traffic periods,

Auckland airport makes use of a single opposing runway for

arrivals and departures to limit all noise exposure over water.

This effectively means that arrivals and departures face each

other on the same runway. As the procedure is only enacted in

very low traffic scenarios, such as late night/early morning both

arrivals and departures are never in conflict.

Runway Weekdays Weekends and German holidays

34 0500 to 0600 0500 to 0800

14 and 16 0600 to 20000800 to 1900 (Arrivals not allowed on

German Holidays)

28 2000 to 0500 1900 to 0500 An extract from the Chicago O’Hare runway rotation test schedule, source -

http://www.airportprojects.net/flyquiettest/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/10/25-

Week-Schedule-1-page.pdfZurich airport runway scheme, source - SkyGuide Zurich AIP

Departures overwater

Arrivals overwater

Auckland runway operations 2300 to 0600

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Runway schemes – Case studies

20

Case Study - Sydney airport’s Long Term Operating Plan (LTOP) was

introduced in response to community pressure to share noise around

the airport. The plan aims to share traffic around the airport according

to the following targets:

• 17% of movements to the North of the Airport

• 13% of movements to the East of the Airport

• 15% of movements to the West of the Airport

• 55% of movements to the South of the Airport

The LTOP defines ten different ways, or modes, of using the airports

three runways. The principal of LTOP is that when making selections of

the runway each day the Australian air traffic control body, Airservices

Australia, must ensure that, subject to safety and weather conditions:

• as many flights as practical come and go using flight paths over water or

non-residential areas where aircraft noise has the least impact on

people

• the rest of the air traffic is spread or shared over surrounding

communities as fairly as possible

• runway modes change throughout the day so individual areas have

some break (or respite) from aircraft noise on most days.

Some of the modes of operation are referred to a ‘noise sharing modes’

(mode 5, 7 and 14a). These procedures should be used whenever

possible on weekdays between 6am to 7am, 11am to 3pm and 8pm to

curfew.

Longer noise sharing hours apply at weekends. Long Term Operating Plan (LTOP) modes of operation-

http://sacf.infrastructure.gov.au/LTOP/files/LTOP_general

_information_fact_sheet_2015.pdf

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Runway schemes – Case studies

21

Case Study (con’t) - Sydney airport, via Air Services Australia, reports

on runway usage against the LTOP targets on its public engagement

website. This information includes an interactive map which shows

runway utilisation including the number of arrivals, departures and

hours when the runway was not used and can be broken down by

aircraft type. On a separate tab, the runway utilisation figures are

reported against the LTOP targets.

The website is easy to navigate and provides a good level of

information for most readers however if more detailed information is

required, the website provides links to detailed monthly reports. The

reports, which are also produced by Air Services Australia, include a

breakdown of runway operations per runway and per day on an hourly

basis, the LTOP runway modes in use and the level of respite provided

over the corresponding flight paths.

(Above) online runway

utilisation, (right) extract from

detailed monthly LTOP report

showing respite provided,

source -

http://aircraftnoiseinfo.bksv.com

/sydney/

Monthly runway utilisation reported against LTOP targets for 2016 for movements to (i) the

north of the airport (left) and (ii) south of the airport (right), source -

http://aircraftnoiseinfo.bksv.com/sydney/

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Introduction

Many airports define a night period where a different and

more stringent set of operating rules are applied compared

to the day-time. Examples of night time practices include

operating restrictions, night quotas, noise surcharges and

rules for managing airline operations in the night period,

including penalties if operations are off schedule.

Duration of the night period

Thirteen airports had defined night period of 6-9 hours in

duration, typically starting at 2200 or 2300 and ending at

0600 or 0700. Some airports applied the same restrictions

throughout the night, while others applied different levels of

stringency – typically at the start/end of the night period or

during the hours before/after the night period. These were

often less stringent than those applied during the night

period.

Typical practices

Operating restrictions: Restrictions applied include

movement limits, curfews/night-flight bans, restrictions on

the operation of certain (noisier) aircraft and runway used.

Night quotas: A small number of airports operate night

quotas. These schemes aim to manage the overall amount

of noise generated at night by having an overall noise

‘quota limit’ as well as a movement limit.

Each aircraft is allocated a number of points depending on

the amount of noise they produce (the louder the aircraft,

the more points allocated). The airport must operate within

a defined limit of night quota points as well as movement

limits.

Night noise surcharge: Airports that included a noise

element in their landing/take-off charges had a separate

day and night-time charge. This is typically a percentage

increase on top of the day-time charge.

Management of late running aircraft: Some airports have

rules applied to manage late running aircraft or have

protocols in place to allow dispensations for aircraft not

scheduled to operate in the night period that are running

late. In the case of the latter these often refer to exceptional

circumstances and require authority, or delegated authority,

from a government department. Some airports also have a

contingency set aside for off-schedule activity.

Penalties applied for non-conformance: Some airports

applied fines for non-conformance with night flight

restrictions.

Regional trends

More than half of the airports researched had defined a

night period although it was more common in Europe.

Airports without a defined night period were primarily those

in the Middle East and United States.

Night flight restrictions – Overview

23

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Night flight restrictions - Best practice from around the world

• Night period starts at 2200 or 2300 and ends between 0400

and 0700. Some airports define night shoulder periods (Zurich)

or night quota periods (Heathrow, Gatwick, Brussels, Madrid).

• Night restrictions have noise at their core and are based on a

number of criteria: noise certification (MCC3 banned at

Amsterdam), quota system (Brussels, Gatwick, Heathrow,

Madrid), night curfew (Zurich), movement limits (Amsterdam,

Gatwick, Heathrow).

• Restrictions on scheduling and the operation of noisier aircraft

during the night period, or periods before or after the night

period (shoulder periods).

• Amsterdam, Charles de Gaulle, Madrid, Heathrow and Gatwick

either apply higher charges in the night period or make use of a

night noise surcharge.

• Changi restricts operations

on one runway between

0000 and 0600.

• Has a scheme to shift

noise away from residents.

• Night time restrictions vary across Canadian airports

starting between 2200 and 0001 and ending between 0600

and 0814. Variations in type of aircraft restricted.

• Pearson is the only airport with a night flight budget

(approximately 15,000 aircraft allowed per year). Number

of night flights allowed to grow with traffic.

• Montreal prohibits aircraft over 45 tons at night.

• Violations of night restrictions incurs fines of up to

CAD5000 for individuals and CAD25000 for corporations.

• Only John-Wayne has a night period. It

applies a night curfew from 2200 to 0700 on

weekdays and 2200 to 0800.

• John-Wayne has a sliding scale for

violations of the night time restrictions

($2,500 to $10,000).

• Other airports do not have penalties as no

night restrictions are in place. Penalties are

applied for violations with NAPs.

• No information on

night restrictions.

24

• Sydney has a night curfew which restricts operations

between 2300 and 0600. Auckland will soon introduce a

similar scheme as part of its 2nd runway. The curfew

times are adjusted at weekends.

• Curfew applies to aircraft based on several criteria

including weight, type, dispensations, missed

approaches.

• Sydney curfew is under Australian law and violations

incur a fine of up to AUD 650,000.

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Duration of the night period

Of the 26 airports investigated, 13 had a defined night

period where a different and more stringent set of operating

rules where applied compared to the day-time. Night

periods were 6-9 hours in duration, typically starting at

2200 or 2300 and ending at 0600 or 0700.

Airports without a defined night period were primarily those

in the Middle East and United States.

Restrictions in the hours adjacent to the night period

Four airports also applied additional restrictions in the 1-2

hours adjacent to the night period. Often the

rules/restrictions applied in these hours were less stringent than those applied during the night period, but more

stringent than those in the day. Examples in these hours

included – gradual increasing of night-time charges and

restrictions on the noisiest aircraft types. Some airports

take a similar approach, but at the start/end of the night

period (see below).

Variation in rules/restrictions during the night-period

While many airports apply the same rules/ restrictions

throughout the night period, others apply different levels of

stringency throughout the night. Examples include having

less stringent restrictions at the start/end of the night

period, allowing a small number of aircraft per night to be

scheduled/operated at certain times and having periods

where no aircraft may operate.

Night flight restrictions – Duration of the night period

25

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Introduction

Examples of the types of night-time operating restrictions

identified by the research are summarised below.

Movement limits

Four of the airports researched applied night-time

movement limits. These limits are either applied annually or

based upon scheduling seasons. Examples of movement

limits compared to Toronto are shown in the figure below.

Movement limits are set by legislation. For example,

Gatwick and Heathrow apply movement limits as part of

their quota count systems which are set by the Department

for Transport.

Amsterdam Schiphol airport is currently limited to 34,620

movements per year but this could be reduced this year to

32,000 due to delayed implementation of continuous

descent approach (CDA) operations.

Curfews/night flight bans

Frankfurt, John Wayne, Sydney and Zurich, airports have

bans/curfews on night flights.

• At Sydney there are restrictions on the number and type of

movements that can take place during the curfew (see

case study on page 33)

• At Frankfurt, the curfew runs from 2300-0500, with a limit

of 133 movements each night from 2100 to 2259.

• At Zurich a night-time curfew is in place between 2330-

0600, with the time between 2300-2330 used to reduce the

backlog of delayed flights. Landings/take-offs between

2330-0600 are only allowed in exceptional circumstance

and incur high charges (see Zurich case study later in this

document).

Night flight restrictions – Operating restrictions

26Figure: Movement limits during the night period

Source: Government legislation

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Night-time restrictions on certain aircraft types

Airports apply restrictions on certain aircraft types, typically

based upon their Chapter number of certified noise levels.

• Chapter 2 bans: 18 of the 26 airports researched

implemented a total ban on ICAO Chapter 2 aircraft during

the night. Note that today, a limited number of those

aircraft are in use.

For aircraft quieter than Chapter 2, a range of different

approaches are used:

• Marginally compliant chapter 3 bans: Amsterdam

Schiphol, Brussels and Paris Charles de Gaulle airports

implemented a ban on aircraft whose Effective Perceived

Noise Level (EPNdB) was close to the limit of Chapter 3

standards.

• Shoulder hour restrictions: Frankfurt airport ban airlines

from scheduling marginally compliant Chapter 3 aircraft

between 1900-0700 (night period is 2300-0500). Only

Chapter 4 aircraft (which are quieter) are allowed to take

off between 2100-2200.

• Other examples: Airports with night quota systems (see

later pages in this section), restrict the

scheduling/operation of the noisiest aircraft types at night.

Several airports define criteria to restrict certain operations

at night. Montreal airport bans Chapter 3 aircraft that are

over 45 tonnes. Calgary airport is one example of an

airport that restricts Chapter 3 aircraft to certain runways at

night.

Runway restrictions

Some airports also place restrictions on which runways can

be used at night – see the ‘runway schemes’ section in this

document.

Night flight restrictions – Operating restrictions

27

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Night flight restrictions – Night curfew case study (Sydney)

28

Runways

There are also restrictions on the runways that can be used:

• 2300-0600: Only runway 34L is allowed to be used for

landings during the daily and additional weekend hours

(unless assigned an alternative by ATC).

• 2245-2300: Only 16L or 16R can be used for take off.

• 0600-0700 and 2200-2245 (weekends only): Only 16L or

16R can be used.

Exemptions

Exemptions are granted in exceptional circumstances such as

emergencies or search and rescue operations

Penalties

If the curfew is breached, offenders can face criminal

prosecution and fines of up to AUD$550,000.

Other

There are also restrictions and conditions on the use of reverse

thrust and missed approaches.

Case study – Sydney airport night curfew

The Australian Government enacted the “Sydney Curfew Act

of 1995” to restrict aircraft movements during the night.

Specifically, the curfew includes the following:

Time

Movements are restricted daily between 2300-0600. There

are also additional restrictions daily during the shoulder

period between 2245-2300 and on weekends between 0600-

0700 and 2200-2300 on the runways that can be used.

Aircraft movements

During the curfew period take-offs and landings at the Airport

are restricted to specific types of aircraft and operations:

• Small (less than 34,000kg) noise certificated propeller

driven aircraft and ‘low noise’ jets (mostly business and

‘small’ freight jets—these are specified on a list which has

been Gazetted by the Minister) are allowed to operate

without a quota on the number of their movements

• 74 small freight (BAe146 size) aircraft are allowed to

operate per week.

• Between 0500 and 0600, 24 intercontinental arrival flights

are allowed to operate per week.

During the curfew aircraft must operate over Botany Bay, that

is take-offs to the south and landings to the north.

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Night quotas

Brussels, Heathrow, Gatwick and Madrid all operate night

quota schemes. These schemes aim to manage the overall

amount of noise generated at night by having a noise

‘quota limit’.

Typically a number of quota points will be assigned to each

aircraft depending on the amount of noise they produce. In

the examples identified, this uses the certified noise levels

of an individual aircraft. The louder the aircraft, the more

points allocated (see example for Madrid below). For a

given duration of time (year or scheduling season) the

airport must operate within a defined number of night quota

points. Typically the night-quota period will also have a

movement limit.

Both the Belgium and UK quota systems also limit the

scheduling/operation of the noisiest aircraft types at certain

times of the night quota period (see example for Heathrow

opposite). For example, at Brussels take-off or landing of

aircraft with QC>12 is forbidden 0500-0559.

A case study of the UK night quota system is presented on

the next page.

Night flight restrictions – Night quotas

29

Night-time restrictions at Heathrow (source: Heathrow night flights fact sheet)

Madrid airport quota points allocation

Source: http://www.enaire.es/csee/Satellite/navegacion-

aerea/en/Page/1078418725163/?other=1083158950596&other2=1083857758835

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Case study – UK night quota system

Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted airports use a quota system

during the night quota period (2330 - 0600). This was first

established by the Department for Transport in 1993. The system

is based upon aircraft movements and noise (note that a

movement is defined as either a single departure or a single

arrival). Each aircraft is placed in a Quota Count (QC) band

according to their certified noise output. The band can be different

for a given aircraft, depending on whether it is departing or

arriving.

Each band is associated to a fixed number of Quota Count points.

The quietest band has 0 points and the loudest has 16 points

(note that aircraft with Quota Count 8 or 16 are banned from

operating in the night). In effect, the quieter the aircraft

movement, the lower the number of points awarded.

Each airport is granted a total quota limit for each season

which is applied in conjunction with a limit on movements.

This is shown in the table below.

Airports Coordination Limited (ACL) is the independent

organisation that allocates quota to airlines who wish to

operate in the night quota period. Some quota count is

retained by the airports as a contingency, for example in the

case of aircraft were scheduled to operate outside of the night

quota period, but for various reasons (e.g. mechanical failure,

weather, ATC delay) operate inside it.

In exceptional circumstance (e.g. prolonged disruption)

aircraft are granted dispensations to operate in the night

quota period with oversight provided by the Department for

Transport (i.e. their operation does not count against the

quota). The quota system is reviewed and consulted upon

every few years.

Night flight restrictions – Quota system

30

Quota count points per noise classification. Source:

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachm

ent_data/file/582863/night-flight-restrictions-at-heathrow-gatwick-

and-stansted.pdf

Quota count and movement limits for London airports. Source:

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_d

ata/file/582863/night-flight-restrictions-at-heathrow-gatwick-and-

stansted.pdf

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Night-time noise charges

All 8 European airports that included a noise element in

their landing/take-off charges (see the quieter fleet section

for further information) had a separate day and night-time

charge.

The night-time charge is typically percentage on top of the

day-time charge. In the case of Amsterdam Schiphol and

Heathrow, charges are increased by a factor of 2-2.5 at

night. But in some cases the night-time charge can be 10

times higher.

Zurich airport applies a different approach – see case study

below.

Case study – night-time charges at Zurich airport

Zurich airport have a ban/curfew on flights between 2330-

0600 although in exceptional circumstances some flights are

allowed.

A noise surcharge is levied between 2100 and 0700 local to

cover both the night hours and shoulder periods. Charges

increase from 2100 until 0600 and then reduce for operations

between 0600-0700. After 0700 the night noise surcharge no

longer applies.

Charges also increase if the aircraft is in a higher noise class.

The discrepancy between the charge applied to aircraft is

significant. For example, an aircraft operating at 0030 in the

noisiest class (class 1) will be charged CHF18,000 whereas

an aircraft operating at 2130 in the quietest class (class 5) will

be charged CHF40. The charges (in CHF) are as follows):

Night flight restrictions – Night-time noise charges

31

Charg

es i

ncre

ase f

rom

2100 u

ntil

0600

Charges increase if

the aircraft is noisier

Night noise surcharges at Zurich airport

Source: https://www.zurich-airport.com/business-and-partners/flight-

operations/charges

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Management of aircraft running late or arriving early in

the night period

Some airports have protocols in place to allow

dispensations for aircraft not scheduled to operate in the

night period that are running late or early. These often refer

to exceptional circumstances and require authority, or

delegated authority, from a government department.

Examples include:

• The Transport Minister is able to given dispensations

(permission) to aircraft operating late or early into Sydney

airport’s curfew period

• At Brussels airport, aircraft operating late or early into the

night period must be given an exemption by the national

CAA.

• Heathrow and Gatwick airport can given dispensations to

aircraft running late/early. This power is delegated to them

by the Department for Transport. In addition, the quota

schemes has a ‘pool’ set aside for off-schedule activity.

Additionally, airports also apply some latitude for late

running aircraft. Taking Frankfurt as an example:

• Chapter 3 aircraft (which are banned between 1900-0700)

are allowed to operate until 2100 or from 0500 if they are

running late or early as long as the delay was not foreseen.

• Chapter 4 aircraft scheduled to land between 2100-2200

are permitted to land until 2300.

Penalties for non-conformance/late running –

Overview of research

A number of airports were also found to apply penalties for

non-conformance with night time restrictions. Examples

identified were:

• At Toronto Pearson the penalty for non-conformance with

restrictions is 16 times landing fee. Further enforcement

action may be taken by Transport Canada.

• Across the rest of Canada, fines are applied by Transport

Canada for violations. This is up to CAD$5,000 for

individuals and CAD$25,000 for corporations.

• John Wayne Airport applies fines on a sliding scale. For

the first 5 violations with night time restrictions the penalty

is $2,500 per issue (i.e. if two rules were broken then the

aircraft operator would be fined $5,000). The next 5

violations attract fines of $3,500-$5,000 per issue. For the

next 10 it is $5,000-$10,000 per issue.

• Violations of the curfew at Sydney airport can incur fines of

up to AUS$850,000. This is administered by the

Department for Infrastructure and Transport.

Night flight restrictions – Other practices

32

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Introduction

The noise generated by aircraft arriving and departing an

airport can be influenced by the procedures used by the

flight crew and air traffic control. A range practices and

operational procedures can be employed to manage the

noise generated by aircraft in these phases of flight.

Common practices

Many of the arrival and departure practices and operational

procedures are in common use at the airports researched.

These includes:

Arriving aircraft:

• Continuous Descent Approaches (CDA), where the aircraft

approaches the runway using a ‘consistent’ descent angle.

• Altitude restrictions during the approach to an airport;

• Advisory restrictions on the use of reverse thrust in night

and off peak periods.

Departing aircraft:

• Noise Abatement Departure Procedures (NADP) 1 and 2.

These are internationally recognised procedures intended

to provide noise reduction to those areas close to the

airport (NADP1) or to those areas further away (NADP2)

• Altitude restrictions limiting early turns;

• The application of noise limits for departures.

Special and unique practices

In addition to the common practices, a number of initiatives

have been developed to either solve a local issue or as a

creative and innovative solution to noise management. The

initiatives in this area include

Arriving aircraft:

• The combination of CDA and Low Power Low Drag (LPLD)

operations;

• The joint development and introduction of an arrivals code

of practice by airports, airlines and air traffic control;

• Swing-over arrivals when the aircraft approaches a pair of

parallel runways. The approach is made to one runway

with a visual manoeuver to land on the neighbouring

runway.

• Steeper approaches such as a 3.2 degree glideslope.

Departing aircraft:

• The joint development and introduction of a departures

code of practice.

• Continuous Climb Operations (CCO).

Trials

In addition this section has also researched practices in the

management and communication of trials.

Noise abatement procedures - Overview

34

1a continuous descent may not necessarily involve a continuous descent, level segments are permitted within the researched definitions. Level segments are often used to aid aircraft to slow

down at the start of the descent without the use of the flaps / speed brake.

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Noise abatement procedures - Best practice from around the world

35

• UK airports arrivals and departures code’s of practice.

• CDAs are commonly used at all airports, however

definition varies along with the applicable time periods.

• LPLD used at both London, Madrid and Zurich airports.

• NADP 1 or 2 used at almost all airports.

• P-RNAV and PBN used at the majority of airports

however this is mostly a straight replacement for the

legacy SID.

• Early turns are not typically used, however ‘noise

preferential routes’ are applied.

• Airports used mini-websites to report on trials activities,

which provide updates on progress along with trial

reports.

• Steeper approaches (3.2⁰) have been trialed at Heathrow

and Frankfurt with limited improvements in noise seen.

• Frankfurt uses ‘swing over’ visual approaches to shift to

a parallel runway up to 4 NM from touchdown to avoid

directly overflying specific areas.

• CDA used based upon

vectored approach/RNAV

implementation.

• NADP 1 or 2 used on

departure at Hong Kong.

• Early turns are not used to

maintain straight out

departure over the water

at Hong Kong.

• CDAs used by NAV CANADA where possible, although its more commonly used on RNAV STARs.

• Vancouver request pilots to use LPLD approaches.

• NADP 1 or 2 used and altitude restrictions in place to limit turns post departure, applied in some

areas to limit noise impact / maintain operations over industrial areas.

• Websites used to communicate information on trials such as P-RNAV/PBN implementation.

• Early turns are used to allow prop aircraft to exit the departure flow.

• CDA not commonly used however are

seen as a future step as part of NextGen

and have been trialled at San Francisco.

• Implementation of departure procedures

linked to P-RNAV implementation including

FAA AC 91-53A NADP procedure.

• Some early turns used at San Francisco

and Chicago O’Hare to keep noise over

industrial areas.

• Airports operate trials websites (NextGen

program) which include detailed

information, consultation, environmental

reviews and workshop materials.

• NADP 1 or 2 used at

Istanbul Ataturk.

• CDA implemented using P-RNAV STARs.

• ILS joining point at 14nm and 4,000ft to keep

aircraft higher on approach.

• ICAO NADP 1 or 2 used on departures.

• Early turns are not allowed and 3,000ft limit

applied before turns can be commenced.

• Websites used for trials covering PBN

implementation, includes status updates,

consultations and output documents.

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Arrivals procedures - overview

Twenty-two of the 26 airports researched prescribed at

least one procedure or practice to manage noise from

arriving aircraft. Often more than one initiative was used

with the most common being the use of Continuous

Descent Approaches (CDA) and the application of altitude

limitations during the approach phase of flight.

Continuous Descent Approaches

Conventional approaches to an airport involve phases of

level flight, as shown in the diagram on the upper right. A

Continuous Descent Approach (CDA) aims to reduce the

amount of time an aircraft remains in level flight during the

approach phase. Doing so offers the opportunity to reduce

noise, emissions and fuel burn along the approach path

(see case study for Amsterdam on following sides).

Work by the UK CAA shows CDAs to provide noise

reductions of up to 2.5 to 5 dB, varying over distances from

touchdown of 10 to 25nm1. The noise reduction is achieved

by keeping the aircraft higher for longer and allowing the

aircraft to maintain a managed gliding approach using low

to idle thrust setting.

Although sounding simple in theory, in practice it is difficult

to currently enable CDAs to be flown without any level flight

in the busy traffic environment experienced at international

airports. For this reason airports tend to either operate less

stringent definitions of CDAs which allow some periods of

level flight (UK case study on the next page), thereby

achieving some of the noise benefits of CDA throughout

the day. At other airports, CDAs are only used at night or

other periods of low traffic density.

Noise abatement procedures - Arrivals

36

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

CDA CDA/LPLD Reverse thrust Altitude limits

Num

be

r o

f a

irp

ort

s

ap

ply

ing

pra

ctice

s

The procedures which airports apply to manage arrival noise

Typical stepped approach

vs a typical CDA

1 CAA Paper 1165, Managing Aviation Noise, UK Civil Aviation Authority, 2014.

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Nine of the airports researched made reference to CDA

procedures, although only 4 actively used CDA at all

operational times. The remaining airports had implemented

CDA as part of an RNAV or PBN arrival routing which was

not in use at all times.

Although the majority of airports make use of new

navigational technology, it is possible to undertake a CDA

using radar vectoring (the provision of direction, speed and

altitude commands by air traffic control to pilots).

Continuous Descent Approaches and Low Power Low

Drag

When an aircraft extends its flaps and undercarriage on

approach this disturbs the airflow around the aircraft and

creates noise.

Low Power Low Drag procedures are intended to safely

delay the extension of flaps and undercarriage. In the

United Kingdom LPLD is defined as “a noise abatement

technique for arriving aircraft in which the pilot delays the

extension of wing flaps and undercarriage until the final

stages of the approach, subject to compliance with ATC

speed control requirements and the safe operation of the

aircraft.”

Noise abatement procedures - Arrivals

37

Case Study - CDA definitions vary around the world as follows:

EUROCONTROL define CDA as follows: ‘Continuous Descent

Approach is an aircraft operating technique in which an arriving

aircraft descends from an optimal position with minimum thrust and

avoids level flight to the extent permitted by the safe operation of

the aircraft and compliance with published procedures and ATC

instructions’.

The UK use the following wording in the AIP: ‘A descent will be

deemed to have been continuous provided that no segment of

level flight longer than 2.5 nautical miles (nm) occurs below 60001

ft QNH (FL070) and ‘level flight’ is interpreted as any segment of

flight having a height change of not more than 50 ft over a track

distance of 2 nm or more, as recorded in the airport noise and

track-keeping system.

1 Not all airports in the UK start CDA at this altitude as it can vary due to airspace, for example Gatwick commences CDA at 7,000ft and Luton from 5,000ft.

Frankfurt use the following wording in the AIP: ‘pilots should expect

a clearance to descend below FL 70 only 6 NM prior to reaching

the above-mentioned points. Pilots should adjust their speed

accordingly (approx. 200 – 220 kt when leaving FL 70) and are

urgently requested to perform their descent from FL 70 as a

continuous descent whenever possible’.

Schiphol use the following wording in the AIP: ‘Executing a CDA

implies that after NIRSI, NARIX or SOKSI a continuously

descending flight path without level segments is to be flown in a

low power and low drag configuration. A flight path is considered

continuously descending when there is no level segment. A

segment is considered level if the altitude loss is less than 50 ft

over a distance of 2.5 NM’.

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Work by the UK CAA shows LPLD can deliver reduction of

between 3 to 5dB1.

Low Power Low Drag (LPLD) can be combined with a CDA

to ensure the aircraft maintains a low noise configuration,

with a reduced flap setting and the delayed deployment of

the landing gear for as long as possible. 8 airports, mainly

in Europe, prescribe the use of LPLD procedures in the AIP

alongside CDA. Although the exact wording used is

typically non-descript.

Noise abatement procedures - Arrivals

38

1 CAA Paper 1165, Managing Aviation Noise, UK Civil Aviation Authority, 2014.

Case Study - LPLD definitions vary around the world as

follows:

Heathrow and Gatwick use the following LPLD wording in the

AIP: ‘Where the aircraft is approaching the aerodrome to land it

shall, commensurate with its ATC clearance, minimise noise

disturbance by the use of continuous descent and low power,

low drag operating procedures’.

Schiphol use the following LPLD wording in the AIP: ‘Executing

a CDA implies that after NIRSI, NARIX or SOKSI a

continuously descending flight path without level segments is

to be flown in a low power and low drag configuration’.

Vancouver use the following LPLD wording in the AIP: ‘Use low

power/drag profiles consistent with safe operating procedures,

conforming to published visual approaches and as directed by

ATC’.

Hong Kong use the following LPLD wording in the AIP: ‘During

a CDA pilots should maintain a low thrust setting and should

not have recourse to level flight.’

Case Study - Amsterdam Schiphol uses P-RNAV routing to

accurately direct aircraft on approach to the ILS in the night

period between 2300 to 0600 making use of both CDA and

LPLD.

The procedure has been specifically designed for night time

operations and commences around 30 nautical miles from the

airport. Aircraft are directed onto the P-RNAV routing, which

has been carefully designed to maintain a vertical path direct to

the ILS. An LPLD configuration with minimal thrust setting is

maintained throughout, providing an optimum low noise

approach. Whilst the lateral path was designed to minimise

overflight of noise sensitive areas.

The introduction of the procedure has reduced the ‘noise

footprint’ of a Boeing 747-400 aircraft by 20km as shown in the

figure on the next page. (Continued)

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Altitude Limits

Thirteen airports applied specific altitude limits within their

noise abatement procedures, these restrictions focus on:

• Restricting the altitude at which aircraft can join the

glideslope/Instrument Landing System (ILS);

• Specifying altitude limits over noise sensitive areas such

as urbanised areas.

In all situations, the restrictions aimed to increase the

altitude of aircraft and keep them higher for longer thus

reducing the impact of noise.

Noise abatement procedures - Arrivals

39

According to the Netherlands slot coordinator (SACN), the

implementation of CDAs is delayed and Amsterdam Airport

Schiphol is facing temporary environmental restrictions in order to

compensate this. Due to these temporary restrictions, a further

reduction of night movements to 29,000 per year (from 34,620) is

expected within a maximum of three years’ time.

Reports via the Environmental Council Schiphol note that the

difficulty in implementing CDA is due to the nature of the RNAV

CDA arrival routing, limiting capacity to a level where it is not

sustainable given the current airport and network traffic levels.

Source: NLR Research Paper,

environmental benefits of CDA at

Schiphol Airport NLR-TP-2000-275

Noise footprint comparison between

CDA and typical approach for a B744

Distance from airport (km)

Altitude

Case Study - Auckland airport applies altitude restrictions in its

AIP. The entry notes that ‘Except when operating in accordance

with an instrument approach procedure… aircraft must not be

flown over the high density population areas of greater Auckland

city at an altitude of less than 5000 ft. The boundaries of these

high density population areas are defined in the Auckland Noise

Abatement Chart’. The Auckland noise abatement chart provides

a map of the area around the airport and clearly marks areas of

high population density for which this restriction applies.

Case Study - Los Angeles airport applies restrictions on

helicopter flights over the city requiring operators to avoid flying

below 2,000ft during the day and not flying over the city between

2200 and 0700 local.

Case Study - Heathrow airport applies restrictions on the ILS

joining point and does not permit aircraft to join the ILS below

2500ft in the day (0600 to 2330 local) and 3000ft or 10nm in the

night.

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Reverse thrust

Nine of the airports researched have voluntary restrictions

on use of reverse thrust on landing where pilots were

asked to minimise the use of reverse thrust unless it was

required to maintain safety. The majority of airports applied

these restrictions in the overnight period only.

Additional noise based restrictions

The research also highlighted a number of specific

practices applied at individual airports. These included:

• Voluntary industry code of practice: In the UK, the

Department for Transport, Civil Aviation Authority, airports,

airlines, the air navigation service provider developed an

industry code of practice for noise from arriving aircraft.

The document defines options to reduce approach noise

including the implementation of CDA and LPLD procedures

and provides guidance to air traffic control, flight crews and

airports on how to deliver improvements.

The document also reports on improvements made since

the work commenced including the benefits made to air

traffic controller training and the improvements seen in

CDA compliance. The document was widely circulated

within the industry and is publicly available on the

Sustainable Aviation website1.

• Swing over arrivals: This is a visual procedure

implemented at Frankfurt airport to reduce the impact of

noise on populations living under the approach path to one

of the airports runways (runway 25C). The procedure is

outlined in the figure below. It requires the crew to initially

fly an approach to runway 25C using the approach path for

runway 25L. At any point on the approach, but not less

than 1,000ft AGL (above ground level) and 4 nautical miles

from touchdown, the pilot will visually manoeuver the

aircraft onto the approach path for runway 25C.

Noise abatement procedures - Arrivals

40

Case Study - Madrid Barajas restricts the use of reverse thrust

in the night period with the following wording contained within its

AIP, The use of reverse thrust above from idle regime is

prohibited at night time (2300-0700 LT) except if necessary for

safety reasons, in this case, it must be notified to TWR and the

Departamento de Medio Ambiente of the airport.

25 L

25 C

Approach path if continued

Town under approach path

Swing-over procedure

Typical approach path

The swing-over approach procedure in use at Frankfurt

1 http://www.sustainableaviation.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Noise-from-Arriving-Aircraft-%E2%80%93-An-Industry-Code-of-Practice1.pdf

w w w . a sk he l io s . c o m

Steeper Approaches

Steeper approaches have recently been trialled at both

Frankfurt and Heathrow. A steeper approaches involves

flying along the instrument landing system at a slightly

steeper angle, of 3.2 degrees in comparison to the typical 3

degrees. The increase in approach angle increases the

height of arriving aircraft and therefore reduces the noise

for aircraft closest to the airport.

Departure procedures - overview

Twenty three of the 26 airports researched applied