God, Brains and Hearts

-

Upload

rachel-langford -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

description

Transcript of God, Brains and Hearts

HEALTH & SCIENCE6 S U N D AY, J A N U A RY 2 4 , 2 0 1 0 T H E J E R U S A L E M P O S T

Ben-Gurion University medicalhistorian Prof. Shifra Schwartz has anodd mission – to find Jewish adults,

now in their 60s and beyond, who aschildren in the US underwent low-graderadiation treatments for the skin disease

known as ringworm. Schwartz, on BGU’sfaculty of Health Sciences’ Prywes Centerfor Medical Education, is writing a bookabout victims of this procedure, in theearly decades of the 20th centuryconsidered the “state-of-the-art”treatment for this condition. Ringwormusually infected the scalps of its victims;radiation was used to remove the hairwith the root to eliminate the disease.The treatment was meant to minimizethe pain the children were put through,because radiation made the hair fall outrather than having to pull it out or shaveit closely. This treatment did not involvemedical negligence, she insists. Whatdoctors did not know then was that suchradiation could cause thyroid cancer andvarious other types of tumors and othermedical problems decades afterwards.

Radiation treatment for ringworm waswidespread during Israel’s early years,says Schwartz, especially amongSephardi children from North Africa.When the dangers were realized, Israeliswho took ill as a result regarded it as amatter of ethnic discrimination andemotional trauma, like arriving in the

country and immediately getting sprayedwith DDT. Even recently, the Knesset hasdealt with related issues such ascompensation for damage and suffering.

But the BGU historian insists the decisionto radiate was not ethnically based: AnAmerican Jewish health insurance servicenamed OSE radiated the heads of 27,000Ashkenazi Jewish children who arrived inNew York from Eastern Europe during the1920s and 1930s. In the 1940s, about4,500 Ashkenazi children who arrivedwere found to have ringworm, and about2,500 were treated with radiation by OSE.

But no records were kept of those whoreceived treatment, so those who havesurvived all these years probably don’tknow they are at high risk for possibleconsequences, Schwartz has informed TheJerusalem Post. Although research intoringworm treatment of this group hasbeen conducted at New York University,the doctors who treat these Jews probably

have no idea of their high risk for illness;some may have never heard of the skindisease or the standard treatment given solong ago, before an oral pill or liquidnamed Griseofulvin – effective in treatingringworm of the scalp – was put on themarket in the late 1950s. Schwartzdisclosed that special schools forimmigrant children with ringworm wereset up in New York so they could learn butnot spread the disorder.

Schwartz is studying the effects ofringworm irradiation on children around theworld, including Portugal (30,000 weretreated in the early 1950s), Serbia (50,000)and Eastern Europe (27,000). She sayschildren underwent radiation treatmentthroughout the US, thus the story is auniversal one that should be investigated notonly for historical reasons but also to followup the possible victims.

The historian notes than unlike the UShealth authorities, the Health Ministryhere issued instructions to all doctors toask patients over 65 who have problemsin their heads and necks whether theyunderwent radiation for ringworm intheir youths. However, there was a

special department in Washington, DCthat has documents showing thatringworm was quite common in this erain various parts of the country.

After news of Schwartz’s research waspublished in Serbia, hundreds of calls werereceived from people who as children hadundergone radiation. In Portugal, adoctor who noticd a rise in thyroid canceramong his elderly patients investigatedand found all had undergone radiation forthe skin fungus.

Schwartz says she is looking forringworm radiation victims from NewYork in the 1940 not because she canoffer medical services but so they willfinally be aware of the potential dangerto their health and seek appropriatetreatment. Their testimony will alsocontribute to documenting the story inher book and archival material. Inaddition, the data will enable her toprove that radiation of the heads ofnewly arrived Sephardi immigrantchildren was not ethnic discrimination.

Anyone with information can contactthe Beersheba researcher [email protected].

BGU medical historian seeks 1940s irradiation victims in US

RINGWORM INFECTION: It used to beconsidered so terrible that children had toundergo radiation to destroy the fungus.

HEALTH SCAN

• By JUDY SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH

Scientists have long believed that dramatic climatechanges were responsible for the ancient Near East’sAgricultural Revolution, about 8,500 BCE, in which

new domesticated crops were introduced to feed theregion’s population. But a new study by researchers at theHebrew University’s Levi Eshkol School of Agricultureargues that farming and the introduction of new cropsrelies on a relatively stable climate.

Dr. Shahal Abbo and colleagues recently published theirfindings in the Springer journal, Vegetation History andArcheobotany.

Basing their argument on evolutionary, ecological,genetic and agronomic considerations, the HU researchersshow why climate change is not the likely cause of plantdomestication in the area. Rather, the variety of crops inthe Near East was chosen to function within the normaleast Mediterranean rainfall pattern, in which good rainyyears create enough surplus to sustain farmingcommunities during drought years.

The team found that farming requires a relatively stableclimate and therefore is not a sustainable option in timesof climatic deterioration. “We argue against climatechange being the origin of Near Eastern agriculture, andbelieve that a slow but real climatic change is unlikely toinduce revolutionary cultural changes,” they concluded.

BETTER SAMPLING FOR SIGNALSA new invention developed by researchers at the Technion

Institute has the potential for improving the performance ofradar, increasing the capacity of audio recorders, reducingpatient exposure time to dangerous radiation and numerousother applications. The innovation, described as an“international breakthrough in sampling technology,” is thebuilding of an electric card prototype that enables thesampling of broadband signals using an especially lowsampling rate. It is arousing great interest among scientists.

The researchers say it can improve the sampling, recordingand processing capabilities of wideband signals by hundredsof percentages. The Technion has already registered a numberof patents on the discovery and expects returns, as theworld’s sampling market is worth billions of dollars a year.

“In digital devices, a physical signal is stored using a series ofbits. For example, music on a computer is represented by aseries of numbers,” explains electrical engineering Prof. YoninaEldar, who worked on the project with her doctoral studentMoshe Mishali. “Of course, the ear cannot hear numbers,”she adds. “This is where the sampling and reconstructionprocess comes in. The goal of the sampling stage is to converta physical signal into a series of zeros and ones. The digital‘tape’ samples the audible signal and translates it into bits.The key in this stage is to perform the conversion in such away that the true underlying signal can later be recovered.

We are all used to saying: “I saw a film of HDTV quality”or “I heard music from the digital player,” adds Mishali.“We forget that humans are capable of sensing, seeingand hearing only physical signals. In the interfacebetween the digital and analog worlds, there is acomponent that samples the physical signal andreconstructs it at the end of the process into the physicalworld that the human system can absorb.”

Existing wideband samplers typically require extensiveand sophisticated hardware and software toaccommodate wideband signals and produce high digitaldata rates. But the researchers say they built a samplerbased on cheap hardware whose manufacturing andcomputational costs would be very low and whoseperformance is much better.

During their work on complex mathematical formulas, thetwo researchers succeeded in “breaking” the basic limitestablished at the beginning of the previous century by theNyquist-Shannon sampling theorem. According to thistheorem, if you sample a signal at a rate that is twice themaximum frequency of the signal, it would be possible toreconstruct the signal exactly by using appropriate processing.This theorem forms the basis for most digital devices today.Since it is desirable to use these devices in the broadestpossible band, it is necessary to increase the signal samplingrate. Technological ability today limits the maximum rate atwhich it is possible to sample and as a result, this requireslarge storage capacity and a high price.

The breakthrough was achieved by using the fact that thereis no broadcasting in parts of the spectrum. “The idea is touse the ‘holes’ in the spectrum wisely in order to significantlylower the sampling rate without damaging the signal,” saysEldar. “The difficulty lies in the fact that since we don’t knowwhere in the spectrum these holes are placed, traditionalmathematical models can no longer be used to characterizeand manipulate such signals. What we were able to prove isthat the mere fact that we know the signal does not occupythe entire spectrum enables us to reduce the sampling rate.”

Israeli study: ‘Climatechange didn’t trigger

agricultural revolution’NEW WORLDS

• By JUDY SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH

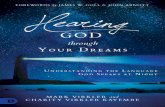

God, brains and heartsThe dating scene for religious singles is strained by unwritten rules and social pressure

to marry. Judy Siegel-Itzkovich reports on a book written by a researcher looking for the neurological and even genetic factors behind falling in love

IIt happens hundreds of times a day – mostly inthe afternoons and evenings – in hotel lobbies,on park benches and at other public places. Ifyou’re not in the know, you won’t even catch

on. It’s the phenomenon of blind dates amongsomewhat nervous young modern Orthodox (andmany haredi) men and women interested ingetting married. They are absolute strangers exceptthat they have probably spoken a few times on thephone in preparation for their first meeting, or werebriefed on the potential marriage partner by relatives,friends, rabbis or matchmakers who suggested the“shidduch.”

Unlike secular, traditional and even some religiousJews who follow less-rigorous practices, members ofthis sector do not “pick up” others or get picked up atparties, bars or on the street, and the aim is not havingfun or going to bed. Everybody participating in thisdating game – in their late teens, early 20s andsometimes beyond – is serious about getting to thehuppa as soon as possible.

It is said that 40 days before birth, God decideswhom the person will eventually marry (bashert).Making matches is also said to be as difficult assplitting the Red Sea.

What psychological, social and even biologicalinfluences affect a decision to commit one’s life toa stranger after a relatively short period, withoutfirst even physically touching the other or beingalone in the same room?

Although this phenomenon has been chronicledin a top-rated Srugim (Crocheted Kippa) TV serieson YES, it took a 27-year-old, strikingly beautifulbut still-unmarried Orthodox woman doing amaster’s degree in brain research to examine itthrough personal interviews and studies ofneurotransmitters and hormones.

RACHEL LANGFORD, who graduated from a PetahTikva ulpana (high school for religious girls) and nowlives with her family in Bnei Brak, has produced a 138-page Hebrew book on the subject.

Titled Darush: Nasich Al Sus Lavan (Wanted: A Knightin Shining Armor) and available atwww.rachelilangford.com, it offers the blind-dateexperiences of 11 single observant women and theauthor – out of 34 such women plus secular ones andreligious men from around Israel. These areinterspersed with chapters about research on how thebrain influences such choices. Langford did notinclude the ultra-Orthodox (haredi Jews), but she didinterview young religious women from a wide varietyof backgrounds, schools and styles, from Bnei Akiva toEzra youth movements.

The author, a student at the Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School who is researchingpotential stem-cell treatment of mice and chickembryos damaged by alcohol and narcotics, has aninteresting background herself. She comes from theshowbiz and artistic Langford family. Hergrandfather Barry was a BBC and Israeli TV director;her father Jeremy a ba’al teshuva (returnee toOrthodox Judaism) and glass artist; her mother Yaela chemistry graduate who became a brainwaveenthusiast; and her aunt Caroline an actress andformer wife of actor and director Assi Dayan.

Rachel (known to friends as Racheli), had a moreconventional childhood as a religious girl wholoved horseriding.

She concedes in an interview with The JerusalemPost that the religious dating scene can be quitesuperficial. Numerous young observant womenwill automatically turn down a suggested match ifthe prospective partner wears his tzitzit out of histrousers (or not); has a beard (or not); wears jeans;is shorter than her; wears sandals with socks (orwithout); lives in the settlements (or not) wears alarge (or too-small) crocheted kippa; is more than acouple of years older; studies in yeshiva (or not);has served in the Israel Defense Forces (or not); orhas a car and apartment of his own (or not).

Many young religious men will turn down asuggested wife if she is not wealthy and shapely; has acar or apartment (or not); is left wing (or not); willwear the “right” head cover after marriage; has sleevesand hemline that are “too short”; or if she is older thanhim. The mind boggles.

There are some different criteria among haredim,she says, but they usually require only a very fewmeetings before they decide to marry, and some –

especially hassidim – won’t see each other againuntil the wedding.

She begins the book with a scene in an ulpana inwhich the news spreads that an 11th-grade pupil hasgotten engaged. This is openly discouraged by theprincipal and teachers, as girls are not supposed to dateuntil after graduation, even after national service. Butthe fact that the girl will soon be married – and quicklypregnant – gives the 17-year-old automatic prestige,she writes. “How romantic!” her girlfriends swoon.

ONLY THE first dating story can be attributed toLangford, even though she presents all of them in thefirst person without pseudonyms. She met a youngman named Meir, a horse lover like herself, andchatted with him while on horseback, she in anappropriate skirt (for modesty) rather than ridingbreeches; as a result, all she got was bruised thighs. “Ididn’t hear heavenly music when I looked at him, andno heart-shaped pink stars sparkled in my head...” sherecalls in the book.

Langford has a wonderful sense of humor and atalent for detail when she describes a woman’s datewith a young man who disappears from their parkbench when she looks in the other direction for asplit second. She searches for him for quite a while,thinking he couldn’t stand her. Finally, she findshim sitting under the leaves of a tree. Embarrassed,he explains that a big dog had come near; since hisbrother had been savagaed by a dog, he istraumatized by them.

In another dating escapade, the young man insistson walking kilometers to a “perfect place to talk,” butthe girl gets bogged down in an dirt path thatsuddenly turns to mud; because of the rules againsttouching, he does not extend his hand to pull her out,and her clothes and limbs become filthy.

Young observant Jews are usually given books ondating written by rabbis and other experts. But, likeone young man who insists on accompanying an“unsuitable date” to her bus stop even when shedoesn’t want him to, “there are cases in which theylearn the protocol but don’t understand it,”Langford comments.

Langford, who has gone on “several dozen” datesover the years since competing her national service,complains about the heavy social pressure to marry assoon as possible. “I discovered that social pressurecomes not just from outside, but also from the brain,”she says, getting to the pure science part of the story.

When a woman smells a baby’s head or skin, herbrain is affected by a pheromone – a chemical signalthat triggers a natural response. “Her brain tells her shewants to become a mother.” Some perfumes containylang ylang, which affects the brain and can ignite anemotional connection.

In a chapter of the book, she also notes that whena young woman is at the acme of her menstrual

cycle – when she is ovulating – she becomes verycritical of other females so as to overcome“competition” from them.

She quotes studies showing that when you walk intoa party where there are several attractive men orwomen, your brain registers your attraction for eachone. Romantic love can activate brain activity with ahigh concentration of receptors for neurotransmitterslike dopamine, which is linked to euphoria, addictionand craving, or norepinephrine, which is connected tosleeplessness, hyperactivity, heightened attention andgoal-oriented behavior. Brain scientists have comparedbrain scans taken of people in various emotional statesand found significant differences.

Beware: A surge in dopamine can make you beunable to think logically for a while. Functionalmagnetic resonance instruments (fMRI scans) can’tactually read people’s minds, but they can displayemotional complexity, the author notes. There areeven genetic influences, she says.

LANGFORD NOTES that according to Canadianstudies released last year, belief in God can “help blockanxiety and minimize stress,” but plenty of stressremains for observant daters. None of the 11 personalstories presented married any of their dates, and manyof those involved found their experiencesuncomfortable. “One of my points was to stress that itis vital for people to improve communications skills,including non-verbal ones,” she says.

The author found that if she runs alongside apotential mate, she feels better toward him thanwhen she doesn’t; the endorphins released byexercise are apparently involved. If the youngman’s eyes face upwards, “his brain is in a visualphase.” If she does the same, Langford maintains,“this can improve communications. This hasbeen researched.”

If one has gone out for a few weeks but feels therelationship has no future, Langford advises beingpolite but telling the truth. “Don’t ask why anddon’t argue,” she advises.

She bemoans the fact that with increasingreligiousity, there are a dwindling number of placeswhere eligible religious men and women can meet.Many little boys and girls are separated inkindergartens, she says, although she says it ispreferable if they do not study in the same schoolsfrom intermediate through high school. If onedoesn’t find “the one” in a youth movement(many of whose branches are now sex segregated),one needs other places in one’s 20s. There is aJerusalem synagogue that periodically offers Torahlectures for men and women sitting on differentsides of the aisles without a physical divider, shesays, and this should be copied.

Langford concludes the book with this sentence(in Hebrew): “Let us choose our way to chose amate.” Young people should not be pressured andshould want a shidduch out of free will. There arepeople who go out only to avoid the socialpressure, not really to get married. I say that onlythe person himself or herself knows what is goodfor him or her.”

RACHEL LANGFORD recalls going on a date on horseback, but ‘I didn’t hear heavenly music when Ilooked at him, and no heart-shaped pink stars sparkledin my head.’ Her book is pictured below. (Courtesy)

(Uni

vers

ity o

f Io

wa)