Global youth networks and the digital divide

-

Upload

heidi-thon -

Category

Documents

-

view

422 -

download

0

Transcript of Global youth networks and the digital divide

GLOBAL YOUTH NETWORKS AND THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

Has ICT become universally accessible, and has it contributed to increased communication between youth

in the global North and South?

SEPT/2015Report

CONTENT

ABSTRACT

1. INTRODUCTION

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. From the knowledge gap to the digital divide

2.2. Norris’ three aspects of the digital divide

2.3. Mobilization/ normalization theses

2.4. Diffusion theory and the Matthew effect

2.5. Bridging the gaps –how to counter the Matthew effect?

3. RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1. Quantitative analysis

3.2. Data collection

3.3. Validity and reliability

3.4. Limitations

3.5. Data analysis

4. FINDINGS

5. DISCUSSION, SUGGESTIONS AND CONCLUSION

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusion

APPENDIX

LITERATURE

04

040406

06

07

07

07

09

09

09

12

21

21

22

23

ABSTRACT

In the context of global development and cooperation, this report is a contribution to the discussion of global access to digital technology and to what extent information barriers still exist between the global North and South. In recent years, digital and social media have become increasingly accessible, but has this led to more frequent communication across geographical, cultural, socio-economic and linguistic barriers?

British scholar Pippa Norris’ theory of the “digital divide” has been central in the aim to uncover different levels of information gaps that exist in society today and, in particular, the perceived digital gap between the industrialized global North and the developing South.

Using Norris’ interpretation of the digital divide, relevant theories such as the knowledge gap, the mobilization and normalization theses, the diffusion theory and the Matthew effect have been briefly examined.

To test the degree to which these divides do exist, a survey collecting data by means of a quantitative study in Norway, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania was carried out, and the findings from the different countries were compared. Vennskap Nord/Sør (Friendship North/South) has collected and compared 629 valid responses from high school students in 33 different schools with existing school exchange partnerships in Norway and in East Africa, illustrating their motivation and use of information and communications technology, in this report referred to as ICT, to stay connected.

Several obstacles to bridging the digital divide were identified, and the findings suggest that both technological and motivational factors are relevant when establishing and maintaining digital networks between students in the global North and South.

This report presents the findings from a survey originally conducted as part of a project paper, written for an Executive Master of Management programme in Digital Communications Management at BI Norwegian Business School.

Heidi ThonSeptember 15th, 2015Vennskap Nord/Sør Friendship North/South

1. INTRODUCTION This report aims to sketch a brief digital portrait of the ICT use among high school students in the three African countries Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, and their inter- action with students at partner high schools in Norway. The goal of the exchange programme, which is admi-nistered by Vennskap Nord/Sør (VNS) aims to teach students about global issues and social responsibility, as well as creating friendship ties across borders. The programme is called “Elimu”, which means education in Swahili, and it facilitates exchanges between high schools in Norway and Latin America, Africa and the Middle East. It is financed by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD). Every year, between 6 and 10 students from the individual Norwegian schools travel to their exchange schools in the South, and later in the school year or the following year, an equal number of students from the South visit their Norwegian schools. It is not possible for a whole class to travel, but those who do not travel will still be involved in the exchange pro-gramme when the students from the exchange school visit.Based on the following reviewed literature, this report aims to identify some of the underlying factors in terms of technology and motivation when digital networks be- tween partner exchange schools in Norway and in Africa are established and maintained. The following two hypot-heses will examine the motivation and degree of contact between schools in Norway and in the South.

Hypothesis 1: Students who have personally travelled on a school exchange are more likely to stay in touch with students from their exchange school than those who have not travelled.

Hypothesis 2: Norwegian and African students give different reasons for not staying in touch with students from their exchange school.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW2.1. FROM THE KNOWLEDGE GAP TO THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

The early 1970’s saw the emergence of the term “know- ledge gap” and its founders have captured the essence of the theory in the following phrase:

“as the infusion of mass media information into a social system increases, segments of the population with higher socio-economic status tend to acquire this information at a faster rate than the lower status segments, so that the gap in knowledge between these segments tends to increa-se rather than decrease” (Tichenor et al., 1970: 159-160).

The original knowledge gap theory is considered valid even today, especially in the context of socio-economic status clusters and the way that they continue to create differential knowledge gains. The concern of the increasing knowledge gap within the

digital sphere emerged in the mid-1990s and focused on the disparities between those who had access to the Internet and those who did not. Described as the digital divide, this gap initially conceptualized the limited access to the technical infrastructure of the Internet, rather than considering the social infrastructure. (Kassam, Iding and Hogenbirk, 2013)Today, the question of access seems irrelevant to the industrialized world, as the definition has moved towards a variety of socio-demographic characteristics, and for which purposes the Internet is used. However, the initial definition is still very relevant in a global North/South perspective, as access in developing countries is restric-ted for a large part of the population by reasons such as lack of infrastructure, freedom of speech, cost, education, illiteracy etc.

2.2.NORRIS’ THREE ASPECTS OF THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

British scholar Pippa Norris voiced one of the first thorough discussions of the digital divide. Her research on global political issues is recognized worldwide and her book from 2001, “Digital Divide –Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide” explains the concept of the digital divide as a multidimensional phenomenon, which encompasses three distinct aspects: 1. The global divide, which refers to the divergence of Internet access between industrialized and developing societies.2. The social divide, which concerns the gap between information rich and poor in each nation. 3. The democratic divide, which signifies the difference between those within the online community, who do, and do not, use the panoply of digital resources to engage, mobilize, and participate in public life. (Norris, 2001:4)

Cass Sunstein recognizes the existing inequality in access to digital technology, what Norris refers to as the global divide, but he believes that the gap is likely to close over time. He argues that the cost of technology and the Internet in particular, is diminishing and will become increasingly available to everyone, regardless of income or wealth. (Sunstein 2007:17)Van Deusen and Van Dijk (2014) agree with Sunstein, and suggest that the term digital divide should be redefined. They argue that the digital divide might finally have closed and that it is now more relevant to discuss the shifts in usage. Kassam, Iding and Hogenbirk are far from convinced that the digital divide will close by itself and argue that the concerns of the global digital divide between industria-lized and developing countries must take into account that access without proper training can do more harm than good. They stress the importance of acknowledging the need for education and democracy building when introducing ICT to populations with low education levels. (Kassam, Iding, Hogenbirk, 2013)

2.3. MOBILIZATION/ NORMALIZATION THESES

A central theme in the research on political and civic engagement relates to Norris’ democratic divide and to whether or not the increasing access and use contri-butes to strengthening and expanding participation. This question is often referred to as either mobilization, where new groups participate in new ways, or normalization where those who are already involved continue to use the new media, thereby increasing their influence while others remain passive. (Hirzalla et al., 2010)Norris also refers to the normalization thesis as the social stratification thesis. She claims that, compared to traditional media channels, the Internet will primarily serve to reinforce the activism of the activists, facilita-ting participation for those who are already interested in politics by reducing some of the costs of communicating, mobilizing, and organizing. She is of the same opinion as Hirzalla et al., regarding differences in social and politi-cal standing that interests are likely to be copied from the offline world into the digital world, further emphasizing the democratic divide. (Norris, 2001)Norris is particularly concerned with the importance of increasing and enhancing civic engagement for citizens and civil society groups worldwide. According to her, there is a danger that the underclass of “info-poor” will become even further marginalized in society, as basic ICT skills become essential for economic success and personal advancement, entry to good career and educational opportunities, access to social networks, as well as opportunities for civic engagement. (ibid.)Prior (2007) shares Norris’ point of view in terms of what she refers to as the social divide when he argues that the increase in media choice is contributing to larger infor-mation gaps between news-seekers and news-avoiders. He claims that the abundance of options makes it easy to completely avoid current affairs and news broadcasts. Prior suggests that the increasing gaps are related to lack of motivation rather than ability. According to him, the current media landscape with its increase in global and current topics as well as entertainment, allows politically interested people to seek and consume more information, while those who are not interested, find it easier to escape the news flow altogether. (ibid.)A recent Dutch survey by Van Deursen and Van Dijk (2014) also supports this view. Their findings conclude that as the internet matures, the cultural, social and economic relationships in the online world will mirror the relation- ships and inequalities in the offline world.While the normalization thesis claims that our online and offline behavior will be more or less identical, supporters of the mobilization thesis believe that the internet will provide the general public with the means to hold politi-cians and other people in positions of power accountable for their actions and promises, as they become more transparent (Dahlberg, Siapera, 2007). Likewise, Benkler (2006) is among those who take a more optimistic approach, believing that the digital media

will encourage new voices to rise, as communication becomes affordable and accessible, with the potential to spread quickly to a large number of people through information cascades. According to him, digital networks allow the individual to reach a large audience through a «little-world» effect, which includes a «long tail» of various media platforms.So where exactly does the problem lie? Is the major obstacle the actual global divide between those who have access and those who do not, should our concern rather be with the way in which people chose to use the techno- logy available to them, or is the root of the issue to be found elsewhere?

2.4. DIFFUSION THEORY AND THE MATTHEW EFFECT

According to Karlsen (2010), the digital divide is closely related to age, education and income. Youth and those who are both well educated and well paid are the ones who use the Internet most often. He uses the diffusion theory to explain this phenomenon where new techno-logy is first explored by the wealthy and highly educated. As the technology becomes more common, the divides disappear.Norris (2001) also draws upon the diffusion theory developed by Katz and Rogers in 1962 to explain how the adoption of many successful innovations often gains momentum and diffuses through the population follow- ing an S- (Sigmoid) shaped pattern. Some people, as part of a social system, try something new or do something differently. They are the first of five established adopter categories, the so-called innovators. Following the inno-vators are the early adopters, then the early majority and the late majority. The final category is the conservative and traditional laggards. In this way, new ideas or be-havior spread to larger layers of society over time. According to Norris, the more critical interpreters of the diffusion theory are of the opinion that compared with laggards, early adopters of innovations usually belong to groups with higher socio-economic status. Their level of education, literacy, and social status provide access to the financial and information resources required to adapt flexibly to innovative technologies. This again often reinforces economic advantages, so that the rich get richer, and the poorer fall farther behind. In a global per-spective, Norris claims that poorer societies, plagued by burdens of debt, disease, and ignorance, keep lagging behind and may ultimately fail to catch up in the digital race. (Norris, 2001).Enjolras et al. agree with Norris concerning the global distribution of wealth. In addition, they emphasize the fact that the algorithms and aggregation effects of search engines function in a way that they prioritize content based on where and by whom it originates, thereby con-tributing to the “rich get richer” effect, also called the Matthew effect, where elites persist. (Enjolras et al. 2013)In essence, one can argue that the Matthew effect con-tributes to building a new digital hierarchy, which partly

contributes to reproducing the power and influence of the existing elites, based on popularity in digital networks. On the other hand, the “small-world” effect contributes to democratization where everyone may be an influen-cer, as information is cascading through the net. (Enjolras et al., 2013)

2.5. BRIDGING THE GAPS –HOW TO COUNTER THE MATTHEW EFFECT?

The majority of discussions on how to close the global gap between the industrialized North and the developing South seem to, in one way or another, touch upon one central theme: education.According to Kassam (2013), giving access to technology without teaching critical meta-cognitive thinking and literacy has proven to be inadequate. Freedom of speech as a prerequisite to foster global responsibility, activism, pluralism and inclusion for all becomes meaningless without quality of education.Norris focuses on the potential that connectivity through digital networks can function as an umbilical cord to broaden and enhance access to information and commu-nications for remote rural areas and poorer neighbor-hoods. She believes that the process of democratization under transitional regimes must go hand-in-hand with improved access and quality of education, in order to ameliorate the endemic problems of poverty in the developing world. (Norris, 2001)Enjolras et al. point to the fact that while traditional media reduces the user to a passive recipient, social media, through media convergence, makes it possible for anyone to actively participate, commercially, politically and democratically into the digital flow. (Enjolras et al. 2013) This would suggest that, given a proper education, it is an opportunity for the youth in emerging democra-cies to take advantage of the possibilities that the Inter-net provides to influence society in an effort to counter the Matthew effect.In addition to lack of quality education in parts of the global South, another main obstacle is related to Norris’global divide and lack of access to the actual infrastru-cture. A third hindrance in the developing world is the cost of the use of technology which, compared to the av-erage income, is many times higher in most developing countries than in industrialized societies. (UNESCO, 2014).There are optimists who envisage that, as technology becomes increasingly affordable, the Internet will play a relevant role in transforming poverty in developing socie-ties. Others are more sceptic and believe that technology alone will make little difference one way or another. The pessimists, on the other hand, emphasize that digital technologies will further exacerbate the existing North-South divide. (Norris, 2001)It would seem therefore that Kassam, Iding and Hogen-birk’s (2013) argument that technology and infrastructure must go hand-in-hand with education is valid in trying to

reduce the digital divide and counter the Matthew effect. In addition, a general conclusion to the literature review can be that education and human development helps to drive both levels of democratization as well as the diffu-sion of digital technologies.

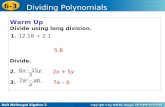

3. RESEARCH DESIGN 3.1. QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

For the purpose of this report, a quantitative approach with a descriptive design was applied, which records a specific behaviour through responses to a questionnaire.The questionnaire contained 14 questions, concluded by an open optional comment field. The main topics were the following:• Country of residence and whether or not the student had personally travelled on a school exchange between Norway and East Africa?• Which digital channels are most frequently used by youth in Norway and in East Africa?• How often is social media used among youth in Norway and in East Africa?• How accessible is digital media in Norway and in East Africa?• For which topics are digital media used among youth in Norway and East Africa?• Which perceived barriers prevent regular contact between students in Norway and in East-Africa?• How often do students with friendship linking stay in touch with each other?• What are the motivations or reasons for staying or not staying in touch?

3.2. DATA COLLECTION

The questionnaire was developed with the aim to reveal to which extent high schools in Norway and East Africa, which currently have existing exchange programmes, make use of digital and social media to stay in touch between and after the actual exchanges. Of particular interest was to determine whether students who travelled on an exchange showed a stronger interest in continuing the relationships online than those who did not travel. If there was no contact, we wanted to explore the reasons why and to uncover whether different re- asons for not staying in touch were given in the different countries.The data collection took place in schools in Norway, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania from December 2014 to February 2015 by means of identical questionnaires. In total 33 schools responded: 18 in Norway and 15 in East Africa. 629 valid responses were registered and entered into SPSS for analysis. The Norwegian students responded directly online through the Wufoo online sur-vey programme, while the African students used paper. Their data was then entered into the Wufoo online survey

07

programme. To ensure anonymity, the names of the different schools have not been used as a variable. The responses between the corresponding friendship schools have not been matched as pairs, but compared on a general level with all other participating schools. The students who were asked to respond to the questionnaire have an existing North/South school collaboration. In order to avoid language problems in interpreting the questions, the questionnaire was produced in three lang- uages: Norwegian, Swahili and English.

3.3.VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY

There is a good mix of male and female students: 44,8% male and 55,2% female. There is a larger number of Nor-wegian responses than Ugandan, Kenyan and Tanzanian individually but, in total, there are more East African than Norwegian responses. (Table 1)In Norway, higher education is available to all and the sample is a valid representation of the population. In East Africa it is worth noting that, although the different schools participating in the survey are representative of a larger population of high school students, higher education is not available to all segments of the general population. Among youth in the age group 14-20 who are not in school, the access to and use of digital media is expected to be much lower than for those attending secondary education. (UNESCO 2014; Elletson, MacKinnon, 2014)

3.4.LIMITATIONS

The most significant limitation of the questionnaire, which could have consequences for hypothesis 1, was that we did not ask students who did not travel whether or not they had made personal face-to-face contact with the students visiting their school. It would have improved the quality of the findings if it could be determined which of the students, despite not having personally travelled, had created ties through physical contact rather than just establishing contact via Facebook or other digital media.

3.5. DATA ANALYSIS

Tables 2, 3 and 4 relate to type of digital media most frequently used in each country, where the Internet is accessed from and what the Internet is most commonly used for. Findings from these questions show that mobiles and tablets are frequently used in all countries. In Africa, Internet cafés are popular places to access the Internet while, in Norway, school is the second most important point of access. School access is however insignificant in Tanzania, very limited in Kenya and relatively restricted in Uganda. 26% of Tanzanian youth have no access to the Internet at all, while the numbers in Kenya and Uganda are both 11%.(Table 5)

Norway Tanzania Uganda Kenya Total Percent

Male 75 47 99 61 282 44,8

Female 136 48 72 91 347 55,2

Total 211 95 171 152 629 100,0

Country of residence

Gender

TABLE 1: Gender: Country of residence: Crosstabulation

How do you access the internet (multiple choice)? Norway Tanzania Uganda Kenya Total

At home 208 32 91 108 439

At school 204 1 57 21 283

Internet cafe 46 19 61 42 168

Mobile/tablet 197 43 113 106 459

No access 0 27 18 13 58

Country of residence

TABLE 2: How do you access the internet (you can choose more than one answer)? Country of residence: Crosstabulation

09

Which types of media do you use (multiple choice)? Norway Tanzania Uganda Kenya Total

Internet 204 35 80 76 395

Facebook 203 54 141 108 506

Twitter 71 14 37 24 146

Instagram 168 27 20 13 228

Snapchat 186 3 2 5 196

Blog 47 6 0 3 56

Whatsapp 34 46 62 61 203

Skype 125 9 14 8 156

Chat 77 19 34 49 179

E-mail 175 27 50 24 276

Country of residence

TABLE 3: Which types of media do you use (you can choose more than one answer)? Country of residence: Crosstabulation

What do you use these media for (multiple choice)? Norway Tanzania Uganda Kenya Total

Staying in touch with friends 203 56 123 99 481

Read news 183 38 92 61 374

Research for school 179 35 88 75 377

Advocacy/Political involv. 35 4 5 12 56

Organize events 108 3 14 8 133

Participate in debates 24 7 12 7 50

Religious topics 10 16 46 44 116

Country of residence

TABLE 4: What do you use these media for (you can choose more than one answer)? Country of residence: Crosstabulation

Countryof residence Never Monthly Weekly Several Once a day Several Total times times per week per day

Norway 1 1 1 0 1 207 211

Tanzania 25 5 8 32 4 21 95

Uganda 20 18 25 49 23 36 171

Kenya 17 44 16 41 7 27 152

Total 63 68 50 122 35 291 629

How often do you have access to the internet?

TABLE 5: Country of residence: How often do you have access to the internet? Crosstabulation

4. FINDINGSDuring our research we aimed to find out more about the motivation for establishing and maintaining digital networks across geographical and cultural borders; what makes some more likely to stay in touch with and strengthen relatively weak ties than others?The motivational focus for establishing and maintai-ning global digital networks between partner exchange schools in Norway and in Africa, relates to our hypothesis 1:Students who have personally travelled on a school exchange are more likely to stay in touch with students from their exchange school than those who have not travelled.

In the first hypothesis, we hoped to find support for the assumption that having personally travelled is a strong motivational factor for staying in touch. The personal experience of a foreign culture and country, combined with face-to-face communication, so-called rich commu-nication with fellow students in the exchange country, is likely to grow the otherwise weak ties between students in exchange schools who literally live worlds apart. It is important to note that the number of students who made personal contact is significantly higher than the number of students who actually travelled, as the persons travelling will meet with several fellow students while visiting their exchange school. Each exchange trip normally lasts for two weeks, and the students stay with a host family from their friendship school during their stay, giving both travelling and receiving students ample time to establish bonds. The number of students having personally participated in an exchange is listed in table 6. 33% of the Norwegian respondents have travelled, while in Tanzania 15,1%, in Uganda 27,2% and in Kenya 24,2% of students have travelled on an exchange. According to Enjolras et al. (2013), Facebook is an important tool for maintaining ties, especially weak ones, but it is not essential for establishing new ones. Their findings suggest that young people in particular, seldom establish new ties through Facebook, and to a lesser extent than older generations. They also conclude that Facebook is very important for maintaining contact with friends and family who live in a different place. Table 7 gives an overview of the number of students who stay in contact with friends from their exchange school, according to nationality and whether or not they have travelled. It shows that 83% of students who travelled stay in touch, while only 50% of those who have not travelled keep contact. This initial finding supports the significance of personal experience posited in hypothesis 1. Table 8 gives a more detailed list of frequency of contact. The findings show that nearly half of Norwegian students and three quarters of Tanzanian students who have not travelled never stay in touch. The numbers are much lower in Uganda (21%) and Kenya (41%). Initially, this would suggest that my hypothesis 1 can be confirmed. However, the table does not indicate the reasons why there is no contact.

When the findings in table 8 is combined with table 12, regarding use of social media, they become more inte-resting. 30% of Tanzanians never use social media. The corresponding number for Norwegian students is 1,4%. In Uganda and Kenya, the number of students who do not use social media is 11% and 8%. The findings would suggest that part of the challenge of keeping in touch is related to Norris’ global divide, i.e. limited or no access to the Internet. In Tanzania especially, the number of students with no access is very high and a definite obsta-cle to communicating through social media.Another point that the survey revealed, is that limited/ restricted access is also a result of school policy regar-ding use of mobile telephones in school. A large number of African students attend boarding school, which means that they are restricted from using social media for longer periods of time while on school premises. We will further comment on this issue when we explore the findings from the open comment field in the survey. Table 8 further shows that, apart from Tanzanian students, there is a relatively high frequency of contact between students, with a larger number of students keeping monthly contact, while there is also a relatively high number of students who communicate several times per day. Although limited or no access to technology among some students in the South prevents communication, the findings suggest that hypothesis 1 can be supported.Further, students were asked whether or not they have established a Facebook group, and again, this was tested against country of residence and whether or not the student had personally travelled. (Table 9) A very large number of students in all countries do not know whether a Facebook group exists and, as might be expected, the majority of these students have not travelled. A suggestion to teachers responsible for the exchange might be to encourage and inform the stu-dents about the possibility of establishing or joining a Fa-cebook group, particularly in connection with an actual exchange, in order to encourage more contact between exchanges. The findings indicate that some schools have established separate groups while others have not. Seen in the context of table 10, the perceived usefulness of so-cial media for staying in touch also differs according to a similar pattern.As our hypothesis 1 suggests, the perceived usefulness of social media for staying in touch is higher among stu-dents who have travelled than for those who have not. 98% of travellers and 86% of those who have not travel-led find social media to be a useful tool for staying in tou-ch. The table indicates that students who have travelled are more positive when assessing the usefulness of so-cial media for staying in touch with students from their exchange school than those who have not travelled. The percentage of positive responses among those who have not travelled is, however, surprisingly high, when taking into account the findings of table 7

Countryof residence Yes No Total Yes No Total number number number % % %

Norway 49 162 211 23,2 76,8 33,5

Tanzania 8 87 95 8,4 91,6 15,1

Uganda 24 147 171 14,0 86,0 27,2

Kenya 26 126 152 17,1 82,9 24,2

Total 107 522 629 17 83 100

Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Programme?

TABLE 6: Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program? Country of residence: Crosstabulation

Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Do you stay in contact with friends from your exchange school? Norway Tanzania Uganda Kenya Total

Travelled: 1. Stay in touch: Yes 43 7 23 16 89

No 6 1 1 10 18

Total 49 8 24 26 107

Not travelled: 1. Stay in touch Yes 58 17 112 73 260

No 104 70 35 53 262

Total 162 87 147 126 522

Total 1. Stay in touch Yes 101 24 135 89 349

No 110 71 36 63 280

Total 211 95 171 152 629

Country of residence

TABLE 7: Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program? Country of residence: (How often) do you use social/ digital media to stay in touch with friends from your exchange school? Crosstabulation

13

TABLE 8: Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program? Country of residence: How often do you use social/ digital media to stay in touch with friends from your exchange school? Crosstabulation

How often do you use social/ digital media to stay in touch with friends from your exchange school? Norway Tanzania Uganda Kenya Total

Yes 6 1 1 10 18 No 104 70 35 53 262 Total 110 71 36 63 280

Yes 28 3 9 7 47 No 19 2 17 27 65 Total 47 5 26 34 112

Yes 5 2 3 2 12 No 3 5 23 12 43 Total 8 7 26 14 55

Yes 3 2 5 3 13 No 5 5 36 17 63 Total 8 7 41 20 76

Yes 2 0 1 0 3 No 2 1 14 3 20 Total 4 1 15 3 23

Yes 5 0 5 4 14 No 29 4 22 14 69 Total 34 4 27 18 83

Yes 49 8 24 26 107 No 162 87 147 126 522 Total 211 95 171 152 629

Country of residence

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Never

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Monthly

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Weekly

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Several times per week

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Once a day

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Several times per day

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Total

Finally, the optional open response section was briefly analyzed, categorizing responses into corresponding groups, and then quantified. The open comments shed further light on the issues of motivation, access to techno- logy and the cost of use, as well as voicing concerns from the South regarding improper use of the Internet and the need for training in practical use of the technology. More than half of the Norwegian students who provided open comments stated that they had made limited or no contact with students from their exchange school. Quite a few also claimed no knowledge of the programme at all. Some students commented that limited access or no access to computers or the Internet in their exchange school made digital contact difficult or impossible. In

Uganda, limited or no access to the Internet or restricted use of mobile telephones in school was voiced as concerns, as well as the cost of internet access. In addition, many young Ugandans are concerned about pornography and improper use of the Internet. Tanzanians voiced similar concerns, where limited or no access to computers or the Internet being by far the most commented on and in addition, they commented on the need for computer training in school.In Kenya, students are concerned with the restricted use of mobile phones and social media in school. They also see the need for better access to and more computer training in school.

Country of residence: Yes No I don’t know Total

Yes 20 24 5 49 No 32 64 66 162 Total 52 88 71 211

Yes 1 3 4 8 No 4 35 48 87 Total 5 38 52 95

Yes 10 10 4 24 No 40 77 30 147 Total 50 87 34 171

Yes 10 14 2 26 No 26 82 18 126 Total 36 96 20 152

Yes 41 51 15 107 No 102 258 162 522 Total 143 309 177 629

Have you established a separate Facebook-group between your exchange schools?

TABLE 9: Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program? Have you established a separate Facebook-group between your exchange schools? Country of residence: Crosstabulation

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Norway

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Tanzania

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Uganda

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Kenya

4. Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

Total

15

To what extent do you find social/ digital media useful for staying in touch with friends from your exchange school?

Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program? Norway Tanzania Uganda Kenya Total

Not useful Travelled? Yes 1 0 0 1 2

No 32 14 16 7 69

Total 33 14 16 8 71

Somewhat useful Travelled? Yes 4 0 1 4 9

No 17 18 6 12 53

Total 21 18 7 16 62

Quite useful Travelled? Yes 11 1 5 7 24

No 49 16 39 56 160

Total 60 17 44 63 184

Very useful Travelled? Yes 19 2 9 8 38

No 31 16 52 32 131

Total 50 18 61 40 169

Excellent Yes 14 5 9 6 34

No 33 23 34 19 109

Total 47 28 43 25 143

Total Travelled? Yes 49 8 24 26 107

No 162 87 147 126 522

Total 211 95 171 152 629

Country of residence

TABLE 10: Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program? Country of residence: To what extent do you find social/ digital media useful for staying in touch with friends from your exchange school? Crosstabulation

The comments are very interesting in as much as they give a nuanced picture of the underlying reasons for limitations in contact between the exchange schools. The open comments also touch upon the need for education in use of the technology, which is exactly what Kassam, Iding and Hogenbirk (2013) deem to be an essential part of bridging the digital divide.The premise of hypothesis 1, that having travelled is a strong motivational factor for further contact, seems to be supported by the data from the survey. An inte-resting experiment in this context would be to follow-up

the same students in a few years and see if, and to what degree, the contact is still kept.Hypothesis 2, Norwegian and African students give different reasons for not staying in touch with students from their exchange school, examines the motives for degree of contact and any possible differences from a North/ South point of view. The questions in our survey also investigate the issue of a possible divide in terms of motivation for staying in touch, further explained in table 11.

If you are not staying in touch with friends from your exchange school, what is the reason (you can choose more than one answer)? Uganda Kenya Total

Norway Limited/restricted access to internet 7 8 15

Tanzania 3 21 24

Uganda 7 42 49

Kenya 10 50 60

Total 27 121 148

Norway Internet access is too expensive 1 3 4

Tanzania 1 16 17

Uganda 10 47 57

Kenya 12 61 73

Total 24 127 151

Norway Limited free time 10 30 40

Tanzania 4 31 35

Uganda 14 69 83

Kenya 10 47 57

Total 38 177 215

Norway Language barrier 4 5 9

Tanzania 4 4

Uganda 4 10 14

Kenya 3 16 19

Total 11 35 46

Norway Not interested in staying in touch 8 48 56

Tanzania 2 2

Uganda 1 16 17

Kenya 9 9

Total Not interested in staying in touch 9 75 84

Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program?

TABLE 11: If you are not staying in touch with friends from your exchange school, what is the reason (you can choose more than one answer)? Have you personally travelled in the ELIMU School Exchange Program? Country of residence: Crosstabulation

17

Again, parameters are related to nationality and whether or not the student has travelled. Particularly relevant are the questions of access to the internet and to social media as shown in tables 5 and 12.Hypothesis 2 assumes that the motivation for not staying in touch is different depending on nationality. Table 13 lists the different reasons given by students in the four countries. As indicated in tables 5 and 12, there are signi-ficant divides between the North and the South in terms of access to the Internet; also between Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda the divide is substantial, with Tanzania still lagging behind. Again, in tables 11 and 13, this divide is evident with only 15 out of 211 Norwegian students stating that limited or restricted access is one of the reasons for not staying in touch. The limitations stated by Norwegian students may well refer to restrictions in their partner school, although this cannot be verified. Of the 278 Afri-can students, 133 gave the same reason. As this question allows for multiple choices, it is impossible to estimate a percentage of a whole.In terms of cost, tables 11 and 13 show an even larger divide between Norwegian and African students with only 4 out of 211 students worrying about the expense of internet use. Among African students, the number is

significant with 147 out of 278 claiming that cost is an essential factor for not staying in touch.When it comes to limited free time, 40 out of 211 Norwegians and 175 of 278 Africans have limited free time, something which indicates that African students have somewhat less free time than Norwegian students. A small but positive surprise is the fact that language barriers do not seem to be a major concern in any of the four countries.The final alternative given for not staying in touch was lack of interest and, here, the numbers are very inte-resting. While as many as 56 out of 211 Norwegians state that they are not interested in staying in touch, only 2 Tanzanians, 17 Ugandans and 9 Kenyans, a total of 28 out of 278 African students are of the same opinion.Therefore, the findings show that, from a Norwegian per-spective, the main reason given for not staying in touch is a lack of interest. In East Africa, on the other hand, very few students responded in the same way, showing that it is not lack of personal motivation which hinders contact, rather the fact that access to the Internet is both restricted as well as expensive. The findings lend support to hypo- thesis 2, regarding motivational factors for not staying in touch.

Countryof residence Never Monthly Weekly Several Once a day Several Total times times per week per day

Norway 3 3 1 6 9 189 211

Tanzania 29 6 9 28 4 19 95

Uganda 19 16 24 42 28 42 171

Kenya 12 32 19 38 12 39 152

Total 63 57 53 114 53 289 629

How often do you use digital/ social media?

TABLE 12: Country of residence: How often do you use digital/ social media? Crosstabulation

TABLE 13: If you are not staying in touch with friends from your exchange school, what is the reason (you can choose more than one answer)? Country of residence: Crosstabulation

If you are not staying in touch with friends from your exchange school, what is the reason (you can choose more than one answer)? Norway Tanzania Uganda Kenya Total

Limited/restricted access to internet 15 24 49 60 148

Internet access is too expensive 4 17 57 73 151

Limited free time 40 35 83 57 215

Language barrier 9 4 14 19 46

Not interested in staying in touch 56 2 17 9 84

Country of residence

The optional open response section, however, suggests that the findings from table 13 are more nuanced than they seem. More than a quarter of the Norwegian students stated that they were not interested in staying in touch. However, another perspective should be added, as the comments from the open response section shows that many Norwegians claim not to know the students from their exchange school. As many as 40 comments were related to limited or no contact or even a lack of knowledge about the exchange programme.As previously commented upon, there seems to be a lack of involvement and communication in some of the Norwegian partner schools, as a very high number of

students have had limited or no contact with visiting exchange students from Africa and, indeed, some of them do not even know of the existence of the programme. As a conclusion, hypothesis 2 may only be partly suppor-ted, as the supposed lack of interest among students in Norway may be related to poor communication and knowledge about the exchange programme in some Norwegian schools and not entirely to lack of interest. From an African perspective, the limited or restricted access to digital media, as well as high costs are factors that seem to far outweigh any lack of interest or motivation in terms of staying in touch with Norwegian students.

19

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

5.1.DISCUSSION

Media is increasingly adapted to personal wants and needs and the technology is with us everywhere we go. Although Africa has taken huge steps forward in the last decade in terms of digital development, the two biggest obstacles for a stable development in Africa today are related to uni-versal education and to the building of stable democratic states.The findings from our analysis indicate that Norris’ definition of the global divide still is a major reason why communication between youth in Norway and in Africa is restricted today. The findings do, however show that the issue is many-faceted. On the one hand, the lack of basic infrastructure is still a major issue, as well as re-strictions imposed by schools, which limit students’ use of mobile phones while on school premises. On the other hand, the number of mobile phone users is growing at an explosive rate, and according to the World Bank, the mobile penetration among the 15 years+ population in Sub-Saharan Africa is already at 69%, compared to 93% in Europe. (Handjiski, 2015) In Handjiski’s opinion, the developing countries will most likely close the global digital gap within a decade. (ibid.)Emerging out of cost-efficiency and practicality, mobile technology is developing at a very rapid rate in Africa. Compared with computers, mobile phones are affordable and practical, as they do not need constant access to electricity and are easy to carry everywhere. African youth are eagerly about to join the social media revolution, as the technology becomes increasingly available. Services like mobile banking, M-Pesa, and the dual Sim-card mobile phone, are African inventions born out of necessity and are among innovations that are now being exported to markets with similar needs such as India, Iraq and Afghanistan. In a continent where electricity is scarce, new inventions include solar-power chargers. According to the World Bank, the African mobile IT industry could be worth $150 billion by 2016. (Ewing et al., 2012)If we assume that access to technology will become uni-versally accessible and that the global gap will eventually disappear, what will happen to Norris’ other two gaps? According to Handjiski, (2015), the main difference be- tween the global North and South is that, in the North, we have everything and we have never really lacked anything. In the context of the democratic divide and the mobilization/ normalization theses, one can claim that in industrialized societies our generation has not had very much to fight for. A major reason why the expected behaviour in industri- alized and developing countries cannot be directly com- pared, relates to the Matthew effect and the uneven distribution of wealth, access to education and a stable political system. While industrialized societies take edu-

cation, a good standard of living, political stability and job opportunities more or less for granted, the developing societies have everything to gain by standing up for their ambition to create a better society. Africa is now in the process of leapfrogging decades of digital development in a matter of a few years. The question is whether they will use their newly gained voice to mobilize through digital channels in order to change and improve their societies. Will they behave differently than some of the theories discussed in my literature review suggests, continuing life as normal as the normalization thesis indicates, or will they take the opportunity to mobil- ize, challenge authorities and demand change?Siapera (2006), points to the discussions on the digital divide and the increasing relevance of new technologies for questions of social justice. She believes that media convergence, where the mass media has lost its mono-poly, has given everyone a voice which can be important for empowerment and that through education and the use of new technologies, digital media can be used stra-tegically to combat the democratic divide. The question of the social divide is primarily related to conditions within a society. In the literature review, the-ories were mainly related to industrialized societies, where several scholars point to motivation rather than ability when explaining different usage of the Internet. In a developing perspective, the issue seems much more complex, as ability and interest do not take into account the level of education within the society. Even when having access to a mobile phone, limited reading skills and a general poor level of education may prevent a person from taking advantage of the opportunities of the techno- logy available.This is where the Matthew effect and the diffusion theory come into play yet again. This time, however, the perspe-ctive is not between the global North and the South, but between the information rich and the information poor inside each developing society, where the innovators, those who have access to an education and to material wealth, will most likely create a gap between themselves and those in society who do not have access. A more optimistic approach would be to suggest that as the access to technology becomes available to a larger part of the population, ICT could actually contribute to reducing illiteracy. Tablets and smartphones are in many respects constructed to facilitate an intuitive approach, and could in turn be a great tool for increasing literacy. Children learn through experimenting and the techno-logy itself could spark curiosity and interest for learning. However, lack of motivation and qualifications among teachers may prove to be yet another obstacle, as their limited technical knowledge and, therefore, perceived control, may lead to their losing face in front of their students. In some developing societies, authorities may attempt to restrict access used for learning purposes, for fear of losing control of the information flow.

21

Global digital networks have made the world increasingly connected and many will agree with Canadian philosopher of Communications Theory, Marshall McLuhan (1962) that we now live in a “Global Village”. Teenagers today grow up as part of this rapidly changing digital environment, buil-ding international friendships without the restrictions of the national postal services. The main goal for the students taking part in this survey is to gain global knowledge and cross-cultural skills, which they can share in their home environments, in their local communities and globally through international networks. In addition, the regular practical use of ICT tools through communication by social media will give students in the South, many of which have limited experience with the use of technology, the opportunity to practice their digital skills. This analysis has, however, uncovered the necessity of providing students in the South with increased access to digital tools, either by allowing use of existing mobile phones or by providing access to the Internet. Our survey describes the situation at one specific time. A suggestion for further research would be to monitor the long-term development of the digital contact between youth in the global North and the South. Will the relati-onships endure, and if so, how will they develop? Will the technological development in the South contribute to in-creased contact? Who will keep contact and who will not? Enjolras et al. (2013) claim that if social capital can be measured through meaningful meetings between people and the opportunity to create social relations, online relations contribute positively to this, as it makes it pos-sible to extend the reach and content of social relations. In their opinion, online groups can be as meaningful as physical communities, as weak ties are allowed to develop.

5.2. CONCLUSION

There are still millions of children without access to basic education, but the joint global efforts of the United Nations ambitious Millennium Development Goals have made great progress in terms of combating illiteracy and ensuring quality of education. Students from the South participating in the survey have been among the fortun- ate ones to see the results of these efforts. Through access to secondary education, they have laid the foun-dations for future personal achievements as well as for their society as a whole. During the actual exchanges, the youth in the North and in the South are encouraged to participate actively in their community, sharing their knowledge of globally sustain-able development and encouraging critical reflection on the causes of inequalities within global resources and political power. Our empirical investigation of motives for use and access to ICT in the global North and South suggests that Norris’ different aspects of the digital divide exist to different degrees within and between the countries analysed.

While children and youth who have grown up in the global North over the past few decades have become “digital natives” (Prensky, 2001), the young generations in deve- loping societies are only just on the cusp of entering the same phase.

APPENDIX

LITERATUREBENKLER, YOCHAI. 2006 The wealth of networks : how social production transforms markets and freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press.

DAHLBERG, LINCOLN AND EUGENIA SIAPERA. 2007 Radical democracy and the Internet : interrogating theory and practice.Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

ELLETSON, H. AND MACKINNON, A. (EDS) 2014 The eLearning Africa Report 2014ICWE: Germany

ENJOLRAS, BERNARD. 2013Liker - liker ikke : sosiale medier, samfunnsengasjement og offentlighet. Oslo: Cappelen Damm akademisk

EWING, JAVIER, NICOLAS CHEVROLLIER, MARYANNA QUIGLESS, THOMAS VERGHESE AND MATTHIJS LEENDERSTE. 2012 ICT Competitiveness in Africa. World Bank, African Development Bank, African Union, Exelsior Firm TNO Innovation for Life

HANDJISKI, BORKO. 2015 Downloaded 01.05.2015. http://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/print/mobile-connectivity-in-africa-has-already-arrived

HIRZALLA, FADI, LIESBET VAN ZOONEN AND JAN DE RIDDER. 2010 Internet Use and Political Participation: Reflections on the Mobilization/Normalization Controversy. An International Journal, 27 (1): 1-15. doi: 10.1080/01972243.2011.534360

KARLSEN, RUNE. 2010Internett, valgkamp og demokrati.Norsk statsvitenskapelig tidsskrift, 26 (03): 235-246.

KASSAM, ALNAAZ. 2013Changing society using new technologies: Youth participation in the social media revolution and its implications for the development of demo-cracy in sub-Saharan Africa. The Official Journal of the IFIP Technical Committee on Education, 18 (2): 253-263. doi: 10.1007/s10639-012-9229-5

KASSAM, ALNAAZ, MARIE IDING AND PIETER HOGENBIRK. 2013 Unraveling the digital divide: Time well spent or “wasted”? The Official Journal of the IFIP Technical Committee on Education, 18 (2): 215-221. doi: 10.1007/s10639-012-9233-9

MCLUHAN, MARSHALL. 1962 The Gutenberg galaxy : the making of typographic man. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

NORRIS, PIPPA. 2001Digital divide : civic engagement, information poverty, and the Internet worldwide. Communication, society and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

PRENSKY, MARC. 2001Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1.On the Horizon, 9 (5): 1-6. doi: 10.1108/10748120110424816

PRIOR, MARKUS. 2007Post-broadcast democracy : how media choice increases inequality in political involvement and polarizes elections. Cambridge studies in public opinion and political psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press

SIAPERA, E. 2006 Multiculturalism online: The internet and the dilemmas of multicultural politics. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 9 (1): 5-24. doi: 10.1177/1367549406060804

SUNSTEIN, CASS R. 2007Republic.com 2.0. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

TICHENOR, P. J., G. A. DONOHUE AND C. N. OLIEN. 1970Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 34 (2): 159-170.

UNESCO. 2014Education for all Global Monitoring Report 2013/4 ISBN 978-92-3-104255-3

VAN DEURSEN, ALEXANDER J. A. M. AND JAN A. G. M. VAN DIJK. 2014The digital divide shifts to differences in usage.New Media & Society, 16 (3): 507-526. doi: 10.1177/1461444813487959

23

Vennskap Nord/SørFriendship North/South

SEPT/2015Report

Pho

to: R

icca

rdo

Lenn

art N

iels

May

er -

iSto

ck (1

), M

atth

ias

G. Z

iegl

er (

3), H

eidi

Tho

n (5

) , R

Aw

pixe

l (8,

20)

, Kri

stof

fer

Gaa

rder

Dan

nevi

g (1

1), I

culig

(13)

, Per

Kri

stia

n Lu

nden

(15,

19)

, Sh

utte

rsto

ck