Giving Old Barns New Life: Ethnic History and Beauty …evergreenquiltersguild.com/documents/Ethnic...

Transcript of Giving Old Barns New Life: Ethnic History and Beauty …evergreenquiltersguild.com/documents/Ethnic...

This is the first in a series of pub-lications about historic barns andfarmstead buildings, and why it isimportant that they be saved forfuture generations. This publicationand the one that follows cover the his-tory of barns and farmstead buildingsin Wisconsin, basic styles of barns,the history of silos and other farm-stead structures, farm buildings builtby various ethnic groups, and thebeauty associated with barns. Futurepublications will address a number oftopics relating to the restoration andmaintenance of historic farmsteadbuildings.

Reminders of history

The barns of Wisconsin are silentreminders of Wisconsin’s history,and a major source of beauty for

the rural countryside. Barns are every-where, along the interstate system, nearmajor cities, snuggled against little vil-lages, on dusty country roads thatwind through the hills, on the banks ofmighty rivers, and near gurgling troutstreams. They are even found onWisconsin’s Madeline Island (in LakeSuperior) and Washington Island (inLake Michigan). Almost anywhere yougo in Wisconsin you’ll see a barn.

As recently as 1830 there wereessentially no barns in the state.Northern Wisconsin was a vast forestland with giant pines and blue lakes.Southern Wisconsin was a combina-tion of woodlands and prairies, wherethe giant bur oaks stood and big bluestem grass bent with the wind.

Settlement history

Jean Nicolet, a Frenchman, steppedashore north of Green Bay in1634. But Nicolet and the French

who followed him were not farmersbut explorers and fur traders. Later,some of them took up the plow andbuilt farmsteads. The early Frenchcommunities were located in andaround Green Bay, Prairie du Cheinand La Pointe on Madeline Island.

It was known that lead existed insouthwestern Wisconsin before 1812,when miners came up the MississippiRiver from Galena, Illinois. As wordof lead mining in the area spread,Cornish and Irish miners began pour-ing into the region, following the

Ethnic history and beauty of old barnsJerry Apps

Givingold barnsnew life

1G3660

University of Wisconsin-Extension

State Historical Society of Wisconsin

Wisconsin Trust for HistoricPreservation

The map above depicts the population of Wisconsin in 1940 based on ethnicity.

LatvianSparse forestItalianIcelanderCroatian SloveneOld Stock AmericanNorwegianIndianSwedishDanishPolishFinnishBohemianMixtureRussianIrishScotchEnglishSwissGermanBelgianHollanderWelshLithuanianFrench

Mississippi River route. Mineral Pointbecame the center of lead miningoperations north of the Illinois bor-der. By 1845 half of Mineral Point’spopulation of about 1,500 wasCornish. Farming was a secondaryactivity for miners, a way to put foodon the table. However, many descen-dants of these miners became full-time farmers when lead miningdeclined. Southwestern Wisconsinbecame a major agricultural centerwith beautiful barns and well caredfor farmsteads.

We must not forget the NativeAmericans who had been here hun-dreds of years before the Frencharrived. We don’t often think ofNative Americans as farmers, butmany of them were. They did notbuild barns or other farm buildingsthat we today associate with farmersand farmsteads. But they grew crops,especially corn and squash, and thesethey stored for future use. Today, theOneida Nation, west of Green Bay,has a large farming operation.

Yankee settlersIt wasn’t until Wisconsin became a

territory in 1836 that settlers beganarriving in Wisconsin with the goal ofowning their own farms. Some of thefirst settlers came from New York State,but also from Ohio, Pennsylvania,Vermont and other states. These earlysettlers were called Yankees, and theysettled primarily in the southeasternregions of Wisconsin. Soon the echo ofax against wood rang out as settlersfelled the trees. The pungent smell ofwood burning filled the air as settlerscleared the land, piled the cut woodand burned it. Some of the trees, thestraighter and taller oaks, were savedfor cabins, barns and storage sheds.Neighbors helped neighbors hew thelogs and fit them together. The plow-man’s whip snapped over the backs ofthe struggling oxen as they pulled thewooden beamed breaking plow, leav-ing behind ribbons of black soil whereblue stem grass had stood for hun-dreds of years.

Black farmersSome of Wisconsin’s early settlers

were escaped and free slaves. A few ofthe early lead miners coming toWisconsin brought their black slaveswith them. Other escaped slavesarrived in the state by way of theunderground railroad. In the early1840s free blacks came to CalumetCounty and founded Chilton. Ablack man established the Town ofFreedom in Outagamie County. The1850 Wisconsin census listed 635 freeblacks and no slaves. By 1860 and thebeginning of the Civil War,Wisconsin’s black population hadreached 1,171.1

Two rural black communities hadbeen established in Wisconsin by1870. One was known as PleasantRidge near Lancaster in GrantCounty, and the other was CheyenneValley in northeastern Vernon County.Both were created by freed andescaped slaves. In both instances, theblack people integrated successfullywith other ethnic groups that had set-tled in the area. In fact, one of the firstintegrated schools in the state was aone-room country school that operat-ed in the Pleasant Ridge community.There is little evidence of the kinds ofbarns and other farm buildings con-structed in these communities.

First immigrantsSoon immigrant groups began

arriving in Wisconsin, a few at first,and then an avalanche. They first set-tled along the major transportationroutes—the Mississippi River and thecounties along Lake Michigan. Then,as more came, they moved always justbeyond the fringe of the settlement,into the interior regions of the state.By 1840, what was called the frontierline formed a crescent with the highpoints in the southwestern and south-eastern counties and the low point inthe central part of the territory.2

As Fred Holmes wrote, “The OldWorld heard the gossip of cheap landsand freedom here in the Midwest.English, Germans, Norwegians,Hollanders, Irish, Belgians, Swiss andother nationalities crowded the boatsto reach this land of promise.”Between June 1846 and December1847, the population of Wisconsinincreased by 55,000, a gain of about30 percent.3

Wisconsin also encouragedimmigrant settlement, not waiting forword of mouth to spread from earlysettlers back to their homelands. Thestate legislature established aCommissioner of Emigration with anoffice in New York. In 1853 anotherlaw added a traveling agent who wasto make sure that the eastern newspa-pers knew of Wisconsin’s “…greatnatural resources, advantages, andprivileges, and brilliant prospects forthe future; and to use every honorablemeans in his power to induce emi-grants to come to this state.”4 Andthey came.

These early immigrants, a sturdyand venturous group, spent 44 dayson average crossing the Atlantic onsailing vessels tossed by rough waters,while enduring often overcrowded andfilthy accommodations. Withsteamships, the crossing time in themid-1860s was reduced to two weeks,and by the turn of the century the tripcould be made in less than a week.

Upon their arrival in New York,many immigrants got on boats for atrip up the Hudson River to Albany.There they transferred to canal boatson the Erie Canal (which was built in1817-1825) to Buffalo, New York andthen by water, rail or wagon to theirfinal destination. Once in Detroit,some took the Chicago Wagon Trailto Chicago. Others rode the lakeboats until they arrived at Milwaukee,and later at several other Wisconsinlake ports such as Sheboygan orManitowoc. A few immigrants camevia New Orleans and up theMississippi.

C 2 C

G I V I N G O L D B A R N S N E W L I F E▲■

German settlersMany of the early log barns in

Wisconsin, the half-timbered barns,and the bank barns that are so preva-lent today have German roots. Eventhough many immigrant groups weresettling in Wisconsin by the 1840s,the Germans soon became the largestgroup. (Before 1900, more than fivemillion Germans came to the UnitedStates. Another two million arrived inthe early 1900s.)5

By 1850, 12 percent ofWisconsin’s population was German.Although they scattered throughoutthe state, the largest numbers ofGermans were found along LakeMichigan and in the central counties.One of the largest groups consisted of800 men, women and children wholanded in Milwaukee in 1839.6

The German immigrants came inwaves. Peak periods were 1845–1855,1865–1874 and 1880–1894.7

Germans brought their knowledge ofbuilding with them from their homecountry. With the need to constructusable buildings quickly, manyGerman settlers built log structures.The Germans usually preferred oakfor their log buildings and erectedlogs to the eaves, closing the gableend with board and batten siding.Germans tended to hew only theinner and outer surfaces of the logs.The tops and bottoms of the logswere left to follow their natural con-

tour. The Germans usually hammeredtriangular-shaped blocks or stripsbetween the interstices in the logwalls, and plastered lime mortar overthe blocks to make the walls weather-tight.8 Of course oak logs were readilyavailable; indeed in many instancestrees had to be cleared from the landbefore it could be farmed.

Some Germans built houses,barns and other buildings following a“half-timbering” constructionapproach. Half timber barns were builtof heavy timbers, often white oak.They were mortised, tenoned and thenpegged together with wooden pegs. Nonails were used in building the barn’sframe. Between the timbers, the spaceswere filled with nogging, to form thewalls of the barn. Nogging took manyforms. It could be kiln-fired brick, clayand straw on wood slats, or even stove-wood. Different from the more typicalwood frame barn where the timberswere covered with wooden boards andthus not visible from the outside, thetimbers of a half-timber barn wereoften visible in the outside walls. A fewof the earliest half-timber barn roofswere thatched; later ones were coveredwith hand split or sawed shingles.

Many German immigrants werefamiliar with half-timber constructionwhich was known in German asFachwerk. From the Middle Ages on,half-timbering construction had beenpopular in much of Europe.

Germans also brought with themtheir knowledge of bank barns. A typ-ical bank barn had two floors, withthe cattle housed on the first floor,and the hay stored on the secondfloor. The barn was often built againstthe side of a hill, or a bank was builtup to the barn so the farmer couldhaul hay directly into the second floorof the structure. Some of the earliestbank barns in the country go back tothe 1700s when Germans settled inPennsylvania. Many German bankbarns were constructed with a forebay.

C 3 C

E T H N I C H I S T O R Y A N D N A T U R A L B E A U T Y O F O L D B A R N S ▲■

feed above

mud and straw nogging

hand split shingles

German half-dovetail corner notch

each timber marked with code

mortice hole

peg hole

tenon

Lutze house barn, c. 1847, Saxon German, near Cleveland.Note half-timber construction.

A German log or half-timber barndesigned to house both cattle and feed.

An expanded half-timber barn withbrick nogging covered by boards.

Half-timber barns were built withoutnails, using tenons and mortices.

A typical German log structure,circa 1850–60.

The forebay is an extension of theupper part of the barn and extendsbeyond the stable wall on the side ofthe stable that is exposed. The forebayprovided some protection for thedoors and windows on the exposedside of the barn.

IrishWith the potato famine in

Ireland in 1846, great numbers ofIrish fled their home country, manyof them finding their way toWisconsin. Irish were soon found inBrown County, near Manitowoc,around Holy Hill in WashingtonCounty and in Waukesha, Dodge andseveral other counties. After the1850s, Irish also settled in northwestWisconsin, in Polk, Erin Prairie in St.Croix County, and in Pierce County.By 1900, the Irish were the secondmost prominent ethnic group inWisconsin. They had settled in all ofthe southern counties, with the largestnumber in Milwaukee County. ManyIrish did not come directly toWisconsin but often lived in otherstates along the way, working theirway west. Some first worked in thelead mines; ancestors of these earlyminers now farm in the areas aroundBenton, Shullsburg and Darlington insouthwestern Wisconsin.

Scandinavians The first Norwegian settlers in

Wisconsin came in 1838 and settledin Jefferson and Rock Counties. TheKoshkonong colony in southeasternDane County was founded in 1838.The Lake Muskego settlement ofWaukesha and Racine Counties beganin 1839. Other major settlementssoon appeared in Vernon andTrempealeau Counties. The CoonValley and Coon Prairie settlements inVernon County once claimed to havethe most densely settled Norwegianarea in the state. As early as 1848 anumber of Norwegians also moved toWinnebago County. In 1850 anotherlarge group moved to Waupaca andPortage Counties.9

By 1850, 70 percent of theNorwegians in the United States livedin Wisconsin. They concentrated inthe area from Madison to the Illinoisstate line, but by the 1940s, everycounty in Wisconsin had aNorwegian settlement. Similar toother immigrant groups, Norwegiansfirst constructed log barns as well aslog homes and other farm buildings.The Norwegians tended to build theirlog structures with snug, tight-fittingjoints requiring a minimum of chink-ing material. They flattened their logsinside and out with their broad axes.Norwegians cut the log ends in a full

dovetail corner notch, and fitted themone over the other locking themtogether. They also used wooden pegsto make the log structure even moresturdy. Holes were drilled into twologs and they were joined with awooden peg which helped preventwarping when the logs dried. Thegable ends of some of these log build-ings were log all the way to the peak.

Rather than having a few largerlog buildings, the Norwegians builtseveral log structures in the farmstead.These might include a chicken coop,animal barn, a feed storage building,granary and workshop, besides thecabin where the settlers lived.

Later, when the Norwegiansbegan building frame barns, theyoften constructed them with gableroofs that were long and steep. A fewof the earliest ones used sod; the laterones were roofed with cedar shingles.

Other Scandinavians also settledin Wisconsin. Danes arrived in the1840s and settled around Racinewhich became known as the mostDanish city in the United States.Soon, Danes were found in Brown,Dane, Waushara, Winnebago, Dodge,Adams, Oconto, Portage and PolkCounties. The Danes clustered mostlyin the eastern and central counties ofthe state.

An early group of Swedes settledon the shores of Pine Lake inWaukesha County in the early 1840s.Another group settled near LakeKoshkonong in Dane County butwere overshadowed by the largerNorwegian settlement in the samearea. The Swedish community ofStockholm in Pepin County datesfrom the 1850s.10 However, thelargest numbers of Swedes came toWisconsin after the Civil War and set-tled in the St. Croix Valley in north-western Wisconsin, on cutover land.In the early 1900s, Swedes made upmore than 75 percent of the popula-tion of Burnett and Polk counties.The Swedes, like the otherScandinavian groups, often construct-ed log barns.

C 4 C

G I V I N G O L D B A R N S N E W L I F E▲■

Norwegian bank barn, near Stoughton.

The Finns were the latestScandinavian group to settle inWisconsin, although Finnish peoplehad come to the US as early as the1680s. Many of the Finns, like theSwedes, followed the loggers in north-ern Wisconsin. The first Finnish set-tlements in the state began in the1870s and 1880s, just south ofSuperior in Douglas County. Thepeak Finnish immigration occurred in1905. By 1900 there were 2,198Finns in Wisconsin; by 1910 thenumber had more than doubled to5,724.11

Most of the Finns coming toWisconsin wanted to farm, and dosome logging in the winter. Manyproceeded to wrest a living out of thisstump strewn wilderness, facing poorsoil, long winters and short growingseasons. Imagine the challenge ofclearing land that was studded withpine stumps, many three feet across.Those Finns without enough moneyto buy land first worked in UpperMichigan’s copper and iron mines, iniron mines in Iron and MarinetteCounty, Wisconsin, and inMinnesota’s Mesabi Iron Range.

The Finns were excellent buildersof log buildings, using hewn timberscarefully fitted together and dove-tailed at the corners. Some of their logbarns were of two-story construction,with cattle housed on the ground

floor and hay stored above. TheFinnish log builders were fussy. Theywould tediously lift a hewn log intoplace, check it for fit, take it down,remove a little more wood, and thenlift it into place again, until the fitwas perfect. This lifting up, checkingfor fit and taking down process mightbe repeated several times.

Finns also constructed hay barnsof logs, leaving the logs round, andplacing the logs some distance apartso the hay could dry easily. Thesecrude log structures were built in thehayfields, making it handy to harvestthe hay, but also providing a source ofcattle feed if by chance fire destroyedthe farmstead barn.

Some of the later Finnish barnsin the area were of frame construc-tion, but with steeply pitched roofsthat gave the appearance that theywere too tall for their length andwidth. Rather than build large farmbuildings, the Finns constructed sev-eral smaller ones, an approach similarto the Norwegians. If a farmer neededanother building, it was relatively easyto construct a log structure, comparedto purchasing sawed lumber and hir-ing a crew to erect a frame building.

One cannot leave a discussion ofthe Finns without mentioning theFinnish sauna, a special little buildingassociated with Finnish farmsteadswhere the family enjoyed steam baths.

C 5 C

E T H N I C H I S T O R Y A N D N A T U R A L B E A U T Y O F O L D B A R N S ▲■

Swedish log barn, on Madeline Island.

Finnish hay barn, originally Douglas County. Moved to OldWorld Wisconsin.

Icelanders also settled inWisconsin; an early group came toWashington Island after the CivilWar. Although many of them werecommercial fisherman, some of thembecame farmers and built barns andother farm buildings on the island.

WelshThe first Welsh immigrants came

to Wisconsin in 1840. John Hughesand his family of seven settled inGenesse, Waukesha County. By 1842,99 Welshmen lived in the Waukeshasettlement.12

Welsh also settled in RacineCounty in 1840, and in ColumbiaCounty in 1845. Soon Welsh immi-grants were found in Winnebago,Fond du Lac, Waushara, Sauk,Jefferson, Rock and La CrosseCounties as well. Many of thembecame excellent farmers, with anendearing love for the land, their ani-mals and their farm buildings. Theywere excellent carpenters and stonemasons, constructing barns withbeautiful stone walls, with an empha-sis on aesthetics as well as usefulness.After the wheat growing era inWisconsin, the Welsh became excel-lent dairy farmers, caring for largeherds of cattle on the rolling lands ofWaukesha County as well as in otherparts of the state.

SwissIn the early 1840s, the first Swiss

families settled in Wisconsin, in theTown of Honey Creek and elsewherein Sauk County. Their legacy includessome fine stone buildings.

In 1845, Swiss agents came toGreen County and made entry for1,200 acres of land. In August of thatyear, more than 100 Swiss immigrantssettled in the Little Sugar River Valley.The land was divided among theheads of families, and the groupbegan farming.13 They brought withthem their knowledge for makingSwiss cheese. To this day GreenCounty is a major producer of Swisscheese in the country. The Swiss alsobrought their knowledge of bankbarns, and their skill for buildingthem. One feature that is distinctiveof many of the Swiss barns in GreenCounty is the pent roof that juts outabove the windows and doors on theexposed side of the first story of thebarn. The pent roof provides a placewhere cattle can get out of the rain onstormy days, as well as weather protection for the doors and windows.

C 6 C

G I V I N G O L D B A R N S N E W L I F E▲■

Welsh barns, near Wales.

Swiss barn near New Glarus. Note pentroof above the win-dows.

Other early immigrants Other immigrant groups arrived

in Wisconsin as well. Several Dutchfamilies settled near Sheboygan start-ing in the 1840s. Soon they were alsofound in Brown, Milwaukee andFond du Lac Counties, although thenumbers were never large. Likewise,Belgians located east of Green Bay toCasco and then north to SturgeonBay. They built farmsteads of logs,including barns, homes and otherfarm buildings. They also built somedistinctive red brick dwellings that arereadily seen in the area.

Bordering the Belgian communityto the South, and stretching throughKewaunee and into ManitowocCounty is a large Bohemian settle-ment. Some of their barns, oftenunpainted, were of frame construc-tion. More typically, their early barnswere of double-crib log construction.

C 7 C

E T H N I C H I S T O R Y A N D N A T U R A L B E A U T Y O F O L D B A R N S ▲■

Luxembourg stone barn near Port Washington.

Bohemian stone barn, near Random Lake.

Ross-Dutch barn at Gibbsville.

English came to Wisconsin,directly from the British Isles orsometimes transplanted from NewEngland. By 1850 nearly 19,000English had settled in the state. Butrather than settle in tightly definedcommunities, true for several of theother ethnic groups, the English tend-ed to disperse. By 1850 there wereEnglish in all of the southern countiesin Wisconsin, with the largest num-bers in Grant, Lafayette and Iowacounties.

ItaliansAs we recite the various ethnic

groups that settled in Wisconsin it iseasy to overlook the Italians. Most ofthe them came to the US after 1900.By 1930 some 4.7 million Italians hadsettled in the United States, making itone of the largest ethnic groups tocome across the ocean. By 1930 theonly country to send more immi-grants to the US was Germany, whichby that year had sent about 6 millionimmigrants to this new land.14

Many Italians came to Wisconsinas craftsmen—they labored in thegranite quarries in Redgranite and inMontello. They worked as barbers,bakers, musicians and cobblers. Theysettled in Madison, along lowerRegent Street, and in Hurley, Kenoshaand Waukesha. They settled in therural areas as well, and some farmed.By 1940 some 32,000 Italians hadsettled in the state.15

The major rural Italian settle-ments were in Barron County, nearCumberland, in and around Genoa inVernon County, and around Pound inMarinette County. The Marinettegroup brought with them their lovefor Italian cheese and their skill incheesemaking.

C 8 C

G I V I N G O L D B A R N S N E W L I F E▲■

Bohemian barn, c. 1914. Near Kewaunee. Note square fieldstone silo.

Detail of overhang on Bohemianbarn.

Bohemian barn near Francis Creek. Has been moved to DoorCounty.

PolishThe Poles were another immi-

grant group that came relatively lateto the state, but then came in largenumbers; in fact, the Poles becamethe third largest ethnic group, exceed-ed only by the Germans and theNorwegians. A large number of Polishsettled in Portage County, in andaround Stevens Point, and in north-western Waushara County. In the1940s, half of the farm population inPortage County was Polish. Anothermajor settlement was in northwesternBrown County, in and aroundPulaski. But Poles could also be foundin the communities of Beaver Dam,Berlin, Princeton, Green Bay, LaCrosse, Manitowoc, Marinette,Menasha, Superior and Thorp.

The Poles took naturally to farm-ing. A good thing, too, for many ofthem bought land that others did notwant—a disadvantage in coming lateto the state. Many Poles found them-selves on sandy, droughty farms,where crop success depended on theamount of rainfall received each year.Yet, the Poles stuck to it. Manybecame excellent vegetable farmers;several Polish families became thenucleus for the large potato industrythat is today so important toWisconsin’s Central sands.

But many Poles were also dairyfarmers, and they built barns. Like somany of the other immigrant groups,the Poles began with log barns, someof which can still be found in thePulaski area. Some also built larger,frame barns with stovewood walls (Adescription of stovewood constructionis included below).

C 9 C

E T H N I C H I S T O R Y A N D N A T U R A L B E A U T Y O F O L D B A R N S ▲■

Polish barn, near Pulaski.

Polish stovewood barn, near Pulaski.

Polish stovewood barn near Pulaski.

AmishOne of the latest groups to move

into Wisconsin, generally comingfrom Indiana and Ohio, were theAmish. They continue to move intoWisconsin. Amish in the UnitedStates have their roots in the German-Swiss Anabaptists of the 16th century.It was William Penn, a Quaker, andthe recipient of a large grant of landin the British Colony (Pennsylvania)who invited Amish people to come tothis country to live among theQuakers. The first Mennonite group(less strict religiously than the Amish)came to this country in the late1600s. The first ship load of Amishleft Holland in 1727, settling inLancaster, Pennsylvania.16

Later, Amish families pushed onwest, into Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsinand into Canada. The first Amish inWisconsin arrived near Medford(Taylor County), in the 1920s, takingup farming on cutover lands. Soonother Amish moved to Wisconsin.Today there are Amish communitiesin Columbia, Marquette, Green Lake,Sauk, Vernon, Monroe, Portage,Waushara, Eau Claire, Clark, Dodge,Rock, Green, Buffalo and perhapsadditional counties.

As farming technology changes,the Amish mostly continue with olderpractices. They rely on draft horses forfield power. They have no electricityor telephones; they drive to town inhorse-drawn buggies, and theydepend on a one-room school to pro-vide education for their children.They also live together in tightly knitcommunities, with strong adherenceto their religious beliefs.

In many communities, the Amishbought existing farmsteads, removedelectrical wiring, barn cleaners andother modern conveniences and beganfarming. As the Amish communitiesexpanded (and they tended to havelarge families), additional farmsteadswere constructed. The Amish builtnew barns and houses, again follow-ing building strategies that were com-monly used before the middle of thiscentury. They continue to hold barnraisings (they call them frolics), abuilding approach that most oftoday’s farmers remember only dimlyif they remember at all.

C 10 C

G I V I N G O L D B A R N S N E W L I F E▲■

Amish barn, near Cambria.

Several styles of roofs were used in building Wisconsin’shistoric barns. An early style used was gable, south ofSpring Green.

Barns and agriculturalchange

As Wisconsin moved from wheatgrowing to dairy farming in thelate 1800s and early 1900s, a

new style of barn appeared. Little logbarns, so prevalent during the settle-ment years, were either torn down,remodeled or forgotten as new, largerbarns appeared. Three-bay, framebarns became places to store hay andhouse dairy cattle. The new dairybarns were built often a hundred feetlong and longer, most with gambrelroofs, and huge mows where the haycrops were stored for the ever-hungrydairy cows confined to their stalls onthe floor below. It became far moredifficult, with the appearance of thelarger, frame dairy barns, to associatethem with particular ethnic groups.The farm may have been owned byNorwegians but the barn builder wasGerman. The plan for the barn mayhave come from the College ofAgriculture at the University ofWisconsin. Was it a German barn ora Norwegian barn? The questionbecame irrelevant.

Aesthetics of barns

Barns are counterpoints to rollingland and broad skies. They arefocal points in a land of undu-

lating hills and far reaching valleys.Many are truly works of art, each onewith a character of its own; each onemaking a special, artistic statement.Destroy an old barn and the beauty ofthe countryside is destroyed as well.

Looking at an old barn up closewe can begin to see the dimensions ofits beauty. Barn roofs come in anassortment of shapes. The early barns,and many more modern ones as well,had simple gable roofs. The early logbarns had gable roofs; so did the firstframe barns. Occasionally a dormerwas built into the roof to add light.

Next came gambrel roofs in thehistory of frame barn building.A bit more complicated toconstruct, but a style thatallowed for considerablymore hay storage areaunder the roofthan a gable roofdesign. Thencame thearched roof,

with laminated rafters and an internalstructure quite different from the gam-brel- and gable-roofed barns. Ofcourse there were many other styles ofbarn roofs. Occasionally we find hip,salt box, monitor, and various othercombinations of roof styles. As barnswere enlarged over the years, we mayfind a gable roof barn with a gambrelroof addition. Attached to the gambrelroof addition may be a further archedroof addition. No matter what roofdesign, all make a pleasing sight, par-ticularly when they are framed againsta clear blue sky, are covered with afresh coat of snow, or merely stand incontrast to the other buildings thatsurround them. The barn is almostalways the dominant building in thecluster.

C 11 C

E T H N I C H I S T O R Y A N D N A T U R A L B E A U T Y O F O L D B A R N S ▲■

Gable roof with a lean-to on each side, east of Mineral Point.

concrete silo

milk house

wood shingles

cupola ventilator

A gambrel-roofed dairy barn, circa 1910.

fieldstone walls with slacked lime mortar

lightning rods

An 1880s dairy barn built into the side of a hilland equipped with a basement and lightning rods.

Cupolas add beauty to a barn’sroof. Usually one cupola was placedin the center of the roof, although onlarger barns we can find two or more.Cupolas came in various shapes. Somehad simple gable roofs, others hadelaborate, many-sided roofs. Somewere octagonal, some square, somerectangular. Many were unadorned.Others were extremely ornate, withlouvered windows, wood carvings andvarious designs. All had a practicalpurpose beyond the artistic—theyprovided ventilation for the storagearea below.

Lightning rods and weather vanesalso adorned many old barn roofs.They, as the cupolas, were first practi-cal and second decorative. Lightningrods, fastened along the top of theroof, were connected by a cablewhich, in turn, was anchored into theground. Being taller than the barn,their job was to attract lightning andthen send the jolt harmlessly earth-ward.

Many lightning rods had various-ly colored glass bulbs attached tothem. There was a practical reason forthem, too. If the farmer noticed abroken bulb, chances were good thatlightning had struck the barn, or aneighbor kid had shattered it with his.22 rifle. Weather vanes often serveddouble duty. They were lightning rodsand they showed the direction of thewind. For farmers, wind direction wasan indicator of upcoming weather. Aglance at their weather vane eachmorning gave them the informationthey needed.

C 12 C

G I V I N G O L D B A R N S N E W L I F E▲■

Arched roof, near Couderay.

Gambrel roof, one of the most popular roof styles found inWisconsin, near Washburn.

Wooden cupolas were found on many of the old barns, someof them with elaborate wood carvings.

The first-story walls of bankbarns, the most common type of barnin Wisconsin, are often beautifulstructures. Hundreds of old barns,especially those built around the turnof the century, had field stone orquarried rock walls. If the barn waslocated in the glaciated area ofWisconsin, then the wall was likelymade of field stone. In the non-glaciated area it was probably quarriedrock.

Field stone walls were built 24 ormore inches thick, and eight feet or sotall. Beyond building sturdy, practicalstructures, the stone masons knew howto blend color and shape into a pleas-ing tableau, often not admitting oreven knowing that they were creatingart as well as building a wall. The mas-sive barn wall, with its array of shapesand colors—browns, blacks, reds,grays—contrasted well with thestraight lines of the barn boards andthe red color they were usually painted.

Occasionally we find a brick wall,and more recently cement block, cin-der block, or poured concrete walls.In some parts of the state, particularlyin the northeast, it is still possible tofind barns with stovewood walls. Afarmer, usually without the means tobuild a stone wall, went to the woodsand cut 24-inch lengths of cedar ortamarack wood. He then corded upthe sticks, placing mortar aroundthem to form a wall. Many believethat farmers who built stovewoodwalls were ashamed of them, an indi-cation that they couldn’t afford amore substantial wall. So as soon asthey had the money these farmerscovered their stovewood walls withclapboards. As it turned out, the clap-boards helped preserve the stovewoodand kept out drafts and rodents.Today we find several beautiful exam-ples of this rather unique buildingapproach in Wisconsin.

C 13 C

E T H N I C H I S T O R Y A N D N A T U R A L B E A U T Y O F O L D B A R N S ▲■

Salt box roof, east of Hollandale.

In the non-glaciated areas of Wisconsin, many barn wallswere constructed of quarried rock.

Where field stones were readily available, they were used.

Of course the color of the barnitself adds to its beauty. Many werepainted red because red oxide paintwas cheaper than other colors. Somewriters suggest that farmers in thestate who came from New York andNew England brought with them theidea that a barn ought be red, butmany barns were also painted white,and often not painted at all.17

Traveling around Wisconsin it is notdifficult to find green, brown, black,yellow, white and unpainted, naturallygray barns. But most are painted red.

To add additional decoration,many farmers painted designs on theirbarn doors, especially on the largedoors that opened into the hay mows.If the barn was red, white squares, awhite X, circles and other designswere painted on the doors. A fewbarns were painted with red andwhite vertical stripes. It is also not dif-ficult to find barns with murals paint-ed on their sides and ends; scenes varyfrom a lakeside picture on a barn nearBayfield to a picture of the Mona Lisawearing a Bucky Badger T-shirt on abarn west of Gilman. And, manybarns were once used as billboardsadvertising everything from GoldMedal Flour to Bull Durham tobacco.

On a windy day in April, stand-ing inside an old barn is like standingin the midst of a great orchestra. Asthe wind blows around the cornersand shakes the side walls, the barntalks back in squeaks and creaks andmoans. In the huge expanse of theopen barn, the sounds echo back andforth, creating an audio beauty thatfew have heard.

There is also the beauty of spacefor in no other place in a rural com-munity can we sense such immensityof enclosed openness as the hay mowsof the old barns. Without admittingto the enjoyment of it, many a farmerstood silently in his empty barn inspring, simply absorbing the beauty ofthe space, and the vastness of it.

C 14 C

G I V I N G O L D B A R N S N E W L I F E▲■

Occasionally, the entire barn was constructed of quarriedrock.

The old historic barns built in the late 1800s and into the1900s had elaborate systems of wooden posts, beams, andbraces, all fastened together with wooden pegs, shownhere and above.

Visual beauty abounds inside thebarn as well. The timbers in the oldframe barns, many of them 10 x 10inches, stretched across the wideexpanse of the hay mows. Juttingtoward the roof were smaller timbers,all elaborately tied together withbraces. The interiors of the old barnswere built entirely of wood, from thehuge supporting beams to the wood-en pegs that held them together. Thebarn was a single wooden entity.Before sawmills were widely available,the beams were hand hewn with adzesand broad axes. As the timbers aged,no matter if sawed or hewn, they tookon a yellowish tan cast that changedcolors slightly as the light inside thebarn changed.

There was also beauty in thecraftsmanship of the early barnbuilders. Rather than building thebarn by installing the upright postsone at a time, and attaching thebeams to them, the heavy framingsections, called bents, were formed onthe ground. A bent was a completeunit of framework, fully braced andextending from the sill to the pointwhere the roof was attached. In someof the taller barns, the bents wereerected in sections.

Barns builders went to greatlengths to measure, cut the mortisesto receive the adjoining members, andfit the framing pieces together. Therewas no electricity and all work wasdone with hand tools, includingdrilling holes in the timbers to receivethe wooden pegs that held the bracingpieces to the timbers and posts. Ittook a master barn builder and hiscrew one to two months to make thebarn ready for the barn raising. Onthe day of the barn raising, the farmerinvited his relatives, neighbors andfriends. By day’s end what began as anaked first-story wall now had stand-ing on top of it a beautiful barn, com-plete with framing, roof and outsideboards. It is still possible to witness abarn raising if one happens to livenear an Amish community wheremany of the old ways of buildingbarns are still followed.

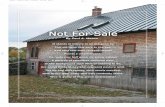

Why save the old barns?

For those who own them, oldbarns can often be remodeled forother uses, saving the money

required by new construction, andproviding a practical reason for pre-serving these structures.

But there are other reasons forsaving the old barns that go wellbeyond the practical and the econom-ic. Barns and other farm buildings arereminders of the state’s ethnic history,of the emigrant families who came bythe thousands to scratch out a livingin the Wisconsin frontier. The Finnsand Swedes who settled in the north,the Germans and Swiss who settled inthe south. The Norwegians who set-tled in the south and west. The Polishwho settled in central Wisconsin. TheBelgians, Bohemians and Dutch whosettled in the northeast—to mentiona few.

The barns of Wisconsin are alsoreminders of the state’s agriculturalhistory. Soon after settlement, wheatwas king, but by the 1870s it had lostits throne and the state was in a timeof agricultural transition, not knowingwhich way to turn. Enter the lowlydairy cow that required daily milkingand feeding, 365 days of the year, anda comfortable stable to provide shelterfrom the long, cold and snowy win-ters of the north. The big barns beganappearing, most of them bank barnsand the majority of them rectangularin shape, 36 feet wide and 50, 60 ormore feet long.

In the 1980s and 1990s, agricul-ture continued changing as dairyherds became larger, and technologyencouraged new ways of harvestingand storing hay and silage for the cat-tle. Economic conditions forced farm-ers to expand their dairy herds andthe size of their farms, switch fromdairy farming to other enterprises, orgo out of business. With several peri-ods of great economic stress (the early1980s for example), thousands ofdairy farmers sold their herds and

their farms. Fewer, but much largerdairy enterprises emerged. Many ofthe old barns became obsolete, nolonger so vital as they once were tothe livelihood of the dairy farmer whobuilt them. New types of barnsappeared. Some were single-story,steel structures. More recent barns arebuilt like greenhouses and coveredwith plastic or with canvas. So the oldbarns become agricultural historywrapped up in a building with acupola on the top.

The history of Wisconsin farm-ing is expressed in a barn. In our hasteto propel ourselves into the future, itis easy to overlook our history. But wecannot know where we are goingunless we know where we have been.Barns can tell us.

For a rural community, barnsprovide a sense of continuity. Theyare visual reminders of where thecommunity has been and what it hasbeen doing. On a more personal level,farm families, those currently livingon the land, and those who havemoved away keep their connections tothe land through the old buildings.The barn often links farm people totheir family histories. They arereminders of the stories associatedwith caring for cows and making hay,of draft horses and calf pens, of frozensilage, and the rain pattering on thebarn roof on a warm July day.

Another reason for saving the oldbarns is their beauty. There is a naturalblending and contrasting of color andshape as farm buildings often standnext to a woodlot, and are surroundedby hillsides of green alfalfa and tallcorn. The beauty of shape and color, ofrelationship and perspective.

The barns of Wisconsin are ofthe land. They are built on it, andthey are from it. They are remindersthat all of us are of the land as well.

C 15 C

E T H N I C H I S T O R Y A N D N A T U R A L B E A U T Y O F O L D B A R N S ▲■

Further readingApps, Jerry. Barns of Wisconsin. Madison,

WI: Wisconsin Trails, (2nd ed.) 1995.

Arthur, Eric and Dudley Witney. TheBarn: A Vanishing Landmark in NorthAmerica. Greenwich, CT: New YorkGraphic Society Ltd., 1972.

Auer, Michael J. The Preservation ofHistoric Barns: 20 Preservation Briefs.Washington, DC: National ParkService, 1989.

Humstone, Mary. Barn Again! A Guide toRehabilitation of Older Farm Buildings.Des Moines, IA: MeredithCorporation and the National Trustfor Historic Preservation, 1988.

Johnson, Dexter W. Using Old FarmBuildings. National Trust for HistoricPreservation. Washington, DC,National Park Service, InformationSeries, No. 46. 1989.

Sloane, Eric. An Age of Barns. New York:Funk & Wagnalls, 1967.

Notes1 Zachary Cooper. Black Settlers in Rural

Wisconsin. Madison, WI: The StateHistorical Society of Wisconsin, 1994, p. 3.

2 Alice E. Smith. The History of Wisconsin:From Exploration to Statehood. Madison,WI: The State Historical Society ofWisconsin, 1973, p. 466.

3 Fred L. Homes. Old World Wisconsin.Minocqua, WI: NorthWord Press,1944, 1990, p. 3.

4 Richard N. Current. The History ofWisconsin: The Civil War Era. 1848-1873. Madison, WI: The StateHistorical Society of Wisconsin, 1976,p. 44.

5 Leonard Dinnerstein and David M.Reimers. Ethnic Americans: A History ofImmigration and Assimilation. NewYork Harper & Row, 2nd ed., 1982, p. 14.

6 Alice E. Smith, p. 491.7 Robert C. Nesbit. The History of

Wisconsin: Urbanization &Industrialization, 1873-1893. Madison,WI: State Historical Society ofWisconsin, 1985, p. 288.

8 Mark Knipping. Finns In Wisconsin.Madison, WI: The State HistoricalSociety of Wisconsin, 1977, pp. 24-26.

9 Richard J. Fapso. Norwegians inWisconsin. Madison, WI: The StateHistorical Society of Wisconsin, 1982, p. 15.

10 Frederick Hale. The Swedes inWisconsin. Madison, WI: The StateHistorical Society of Wisconsin, 1983,pp. 3-8.

11 Knipping, p.11.12 Phillip G. Davies. The Welsh in

Wisconsin. Madison, WI: The StateHistorical Society of Wisconsin, 1982,p. 6.

13 Frederick Hale. The Swiss in Wisconsin.Madison, WI: The State HistoricalSociety of Wisconsin, 1984, pp. 4-6.

14 Dinnerstein and Reimers, p. 12.15 Holmes, p. 172.16 Ellis Christian Lenz. Amish Ways and

Ours. Los Angeles, CA: AuthorsUnlimited, 1987, pp. 3-4.

17 Allen G. Noble and Hubert G. H.Wilhelm. Barns of the Midwest. Athens,Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1995, p. 238.

Author: Jerry Apps is professor emeritus of adult and continuing education at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the authorof more than 20 professional and popular books, among them Barns of Wisconsin.

Photography by Jerry Apps and Alan Pape. Illustrations by Alan Pape are courtesy of Wisconsin’s Ethnic Settlement Trail, Inc.

Special thanks to Todd Barman, Tom Garver, James Hayward, Chuck Law, Alan Pape, Larry Reed, Bill Tishler, Marsha Weisiger andBarbara Wyatt for reviewing this publication.

Funding for this publication was provided by the Wisconsin Humanities Council, the Pleasant Company and the George L. N. Meyer Foundation.

Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department ofAgriculture, University of Wisconsin–Extension, Cooperative Extension. University of Wisconsin–Extension provides equal opportu-nities in employment and programming, including Title IX and ADA requirements. If you need this information in an alternativeformat, contact the Office of Equal Opportunity and Diversity Programs or call Extension Publications at (608)262-2655.

© 1996 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System doing business as the division of Cooperative Extension ofthe University of Wisconsin–Extension. Send inquiries about copyright permission to: Director, Cooperative Extension Publications,201 Hiram Smith Hall, 1545 Observatory Dr., Madison, WI 53706.

You can obtain copies of this publication from your Wisconsin county Extension office, from Cooperative Extension Publications,Room 170, 630 W. Mifflin Street, Madison, WI 53703, or by calling (608)262-3346. Before publicizing, please check on this publication’s availability.

G3660-1 Giving Old Barns New Life: Ethnic History and Beauty of Old Barns