Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

Transcript of Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

-

7/27/2019 Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

1/8

Farmers' Suicides and Response of Public Policy: Evidence, Diagnosis and Alternatives fromPunjabAuthor(s): Anita Gill and Lakhwinder SinghReviewed work(s):Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 26 (Jun. 30 - Jul. 7, 2006), pp. 2762-2768Published by: Economic and Political WeeklyStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4418405 .Accessed: 27/02/2012 03:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Economic and Political Weekly.

http://www.jstor.org

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=epwhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/4418405?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/4418405?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=epw -

7/27/2019 Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

2/8

Farmers' Suicides a n d Responseo f P u b l i c P o l i c y

Evidence, Diagnosis a n d Alternatives f r o m P u n j a bLower yields, rising cost of cultivation,a mountingdebt burden and dippingincomesof cultivators have plunged agriculture into a crisis of unprecedentedscale, theconsequences of which are not just economic. The economic trauma is translatinginto mental trauma,and the ever hardworkingPunjabis, who have emergedstrongerwitheach difficultperiod, are now being forced to admit defeat to the extent of ending theirown lives. Farmers' organisations,political movements and even some state-ledresponseto this crisis have not met with success.

ANITA GILL, LAKHWINDERSINGH

gricultural development in economic theory has beenregarded as a prerequisite for rapid economic transfor-mation of the capitalist economy. Surpluses both oflabour and capital resources have historically been contributedby the agriculture to the modem and dynamic sectors of theeconomy such as the industrial sector. During the process ofeconomic transformation, the agriculture sector diminishes inimportance and the industrial sector plays a dominant role.Transformation of resources from agriculture sector to rest ofthe economy has been seen as a positive and universal phenom-enon by the modern thinkers of growth theory [Lewis 1954;Syrquin 1988].It is a widely acknowledged and accepted fact in economicliterature hata successful structural ransformation s painful foragriculture n all societies, hence nearly all rich countries protecttheir farmersattheexpense of domestic consumers andtaxpayersand of foreign producers[Timmer 1988]. However, a turnaroundin this kind of thinking occurred in mid-1970s to strengthen therural economy through linking rural production with industry.Suggested strategy and policy changes have a capacity not onlyto reduce the pain of structuraltransformation, but also to sub-stantially increase rural income and can also contain the popu-lation from moving to the cities with an already overflowingpopulation [Mellor 1976]. On the contrary, stagnation of tech-nology and yields and low levels of living standards of ruralpopulation along with the "squeeze agriculture" paradigm is asure way of economic stagnation rather than growth. The ag-riculture sector of Punjab has not only been moving towardsstagnation of yields, but also a squeeze on income as well.The state-led green revolution in Punjab increased incomes offarmers irrespective of farm size and catapulted it to the statusof being called the"grainbowl of India".The euphoria,however,was short lived, with the tide turning against the sector thatonce contributed nearly 70 per cent of wheat to the nationalfoodgrain pool. Marginalisation of agriculture and the slowdown in industrial growth during the economic reform periodhave further increased the pain of rural population which hasdrawn the attention of policy-makers, political leadership andacademicsalike. However, suggested policy solutions suffer fromthe same malaise which has already squeezed rural incomes.

This paper attempts to examine the agrarian crisis, some ofits consequences andalternative viable policy options with whatwe hope will be a fresh perspective. The paper is organised intofour sections. Section I examines the emergence of the crisisof the agrarian economy of Punjab. The manifestation of thecrisis in terms of nature, extent and causes of suicides by theagriculturists has been presented in Section II. Public policy asa remedy for this crisis, shortcomings of the public policy andpossible alternative solutions have been analysed in Section III.Concluding remarksarepresented in the last section of thepaper.

Growth ndStructural hangeinPunjabEconomyThe Punjab economy has grown at a rapid rate since theushering in of the green revolution. The growth rate was nearly5 per cent per annum of the net state domestic product (NSDP)during the period 1966-67 to 1998-99. Punjab's per capitaincome in the year 2000-01 was Rs 24,111 and was rankednumber one just ahead of Maharashtra with a difference ofRs 385 at currentprices. Punjab's per capita income at constantprices was Rs 14,916 in theyear2000-01 and was ranked numbertwo, superceded by Maharashtrawith a margin of Rs 256.Economic prosperity and the lead of Punjab in terms of percapita income are, however, now history and other fast growingstates arequite close to surpassing this long sustained lead. This

has been due to the fact that the development process in Punjabhas slowed down in the post-liberalisation regime. Growth rateof NSDP declined to 4.7 per cent in the 1990s compared to thatof the 1980s, which was 5.4 per cent. Majorsectors of the Punjabeconomy showed a deceleration of the growth process in the1990s compared with the 1980s and the worst performance wasof the agricultural sector. The rate of growth of the agriculturalsector dwindled from 5.15 per cent per annum during the 1980sto 2.16 per cent in the 1990s. Growth of income generated bythe agriculturesector from crops slid from a rate of 4.9 per centperannum in the 1980s to nearly 0.4 percent in the 1990s [SinghandSingh2002]. Previously, theagriculturesector was theengineof growth anda majorcontributingsector to theper capitaincome

2762 EconomicandPoliticalWeekly June30, 2006

-

7/27/2019 Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

3/8

of the state from the mid-1960s to the early 1990s. Such a rapiddeceleration of the rate of growth of the agricultural sector ofPunjabhasfar-reachingconsequences for the restof theeconomydue to interdependenceof the sectors, and has pushed those whoaredependent for their livelihood on agriculture into an unprec-edented crisis. Wide variations noticed inthegrowthperformanceof different sectors of the Punjab economy have dramaticcon-sequences for the economic transformation.The character of the Punjab economy at the advent of greenrevolution was fundamentally agrarian. Agriculture consti-tuted 52.85 percent of the gross state domestic product (GSDP)in 1966-67 and increasedto 54.27 percent in 1970-71. Thereafter,the shareof agriculture ector's income in GSDP starteddecliningcontinuously and dwindled to 39.22 in 2000-01. The structuraltransformationprocess has been regarded, at least in theory, asa healthy sign of economic development [Timmer 1988]. How-ever, the growth process must be underlined by technologicalprogressandinvestmentof capital. This implies thatthe structuraltransformation occurring under conditions of a faster rate ofgrowthof theeconomy led by substantial investment and techno-logical progress through interdependence increases the impor-tance of dynamic sectors such as industry. It is important tomention here that the industrial sector of Punjab was not animportantsector of its economy, but gained importance duringthe faster growth of the agriculture sector and increased itsshare in GSDP from 7.86 per cent in 1966-67 to 20.12 per centin 1995-96. Thereafter, the industrial sector's share in GSDPdeclined and was 16.10 per cent in the year 2000-01. However,the tertiary sector has been emerging as an engine of growthduring the structural ransformation and generated 45 per centof the GSDP in 2000-01 (Table 1). The decreasing importanceof agriculture which includes livestock) and the industrialsector,and theincreasing importanceof thetertiarysector is not ahealthysign of structural ransformation.The rate of decline in thegrowthrate of the overall economy due to a sharp fall in the growthrates of the productive sectors was not neutralised by the slowacceleration of the growth of the tertiary sector of the Punjabeconomy.The other ndicatorof a structural ransformationof theeconomyare the changes occurring in the structure of workforce engagedacross sectors and over time. In Punjab, the workforce engagedin agriculture (cultivators and labourers) was 62.67 per cent ofthetotalin 1971, which declined to 58.02 percent in 1981 (censusdata) - a reduction of 4.65 percentage points over a decade(Table 2). The decline from 1981 to 1991 was only 1.95 per-centage points, that s, 56.07 percent workforce was still engagedin agriculture. From 1991 to 2001, there is some controversyregardingthe figures, because according to the census data, theproportionof the workforce engaged in agriculture declined to39.36 per cent, that is, a dramatic decline of 16.71 percentagepoints in a single decade. Now, this is unexplained, because ifwe take a look at the percentage of workforce engaged in theindustrial sector, these are 11.3 per cent in 1971, 13.5 per centin 1981. 12.28 percent in 1991, and 8.41 percent in 2001 (censusdata).Going by census data, this means that both agricultureandindustry have shed workers but this workforce has not foundemployment elsewhere also, because unemployment of both therural and urban population increased during this period [Gill2002]. Further,the NSSO data confirms also that employmenthasshrunk n the organised as well as unorganised tertiarysector.And if the NSSO data is to be followed, the workforce engagedin agriculture n Punjabwas still 53 percent in 2000-01 [Planning

Commission 2003]. Apart from the data controversy, the pointthat emerges is that even now a substantial percentage of theworkforce (53 percent according to the NSSO statistics or nearly40 percent according to the census data) is engaged in agricultureand the change (read decline) is ratherslow, while the squeezein income from agriculture has been rapid (from 40.91 per centin 1966-67 to 26.76 per cent of SDP in 2000-01, Table 1). Thisis an obvious sign.of a grave crisis.Deceleration of economic growth of the Punjab economy ingeneral and the agriculturesector in particularhas tremendouslyincreased the crisis of the capitalist path of economic develop-ment, especially in the liberalisation and globalisation era.A substantial proportion of the workforce still dependent onagriculturefor livelihood faces a serious problem to be gainfullyemployed elsewhere in the backdrop of squeezing share ofagricultural income. Obviously, this is expected because of thefact thatagriculturaldevelopment on capitalist lines of productionanda heavy dependence on marketoccasionally leads to this kindof situation [Timmer 1988]. Therefore, a need arises to examinethe process of agrarian capitalist development of the Punjabagriculture in a historical perspective to provide an appropriateexplanation of the emergence and rise of the agrarian crisis.The ushering in of the green revolution in Punjab began withthe arrivalof high-yielding varieties of seeds for wheat and ricecrop along with the use of chemical fertilisers. The new tech-nology was adopted by the Punjab farmers at a rapidrate whichhad a productivity enhancing effect mainly on two crops, thatis wheatandrice. Not only, landandlabourproductivity increasedmany times but it also had income enhancing effect across theboard. Punjab peasantry was able to reap income gains propor-tional to their ownership of cultivable land [Bhalla and Chadha1983]. The peculiar characteristic of the early green revolutionwas that it hadincreased labourintensity in agriculturalprocesses

Table1: Sectoral Distributionof State Domestic ProductSectors 1970-71 1980-81 1990-91 2000-01Agriculturend livestock 54.27 48.46 47.63 39.22(a) Agriculture 38.51 32.22 30.69 26.76(b) Livestock 15.76 16.24 18.94 12.46Forestryand logging 0.76 0.99 0.59 0.14Fishing 0.03 0.03 0.09 0.38Mining ndquarrying 0.05 0.02 0.02 0.00Manufacturing 8.04 11.00 16.27 16.10Electricity,as and watersupply 0.84 1.31 2.45 2.42Construction 9.21 6.15 3.74 4.97Trade,hoteland restaurants 10.96 14.58 11.33 12.73Transport,torage andcommunication 1.73 2.05 2.32 5.67Bankingand insurance 1.80 2.55 4.67 5.48Real estate and business services 4.79 4.26 3.20 4.22Publicadministration 1.79 -2.81 3.28 4.60Otherservices 5.72 5.76 4.32 4.07Source:StatisticalAbstracts,relevant ssues, Governmentof Punjab.

Table 2: Structure of Workforce n PunjabYear Cultivators Agricultural Industrial Other TotalLabourers Workes Workers2001 2099330 1498976 769047 4774407 9141760(22.96) (16.40) (8.41) (52.23) (100.00)1991 1917210 1502123 749136 1929905 6098374(31.44) .(24.63) (12.28) (31.65) (100.00)1981 1767286 1092225 665442 1402806 4927759(35.86) (22.16) (13.50) (28.47) (100.00)1971 1665153 786705 442070 1018664 3912592(42.56) (20.11) (11.3) (26.03) (100.00)Source: StatisticalAbstract, elevant ssues, Governmentof Punjab.

EconomicandPoliticalWeekly June30, 2006 2763

-

7/27/2019 Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

4/8

such as sowing, weeding and moreso inharvesting andthreshing.Farmingchores were mainly done by family labourcoming fromthe households of small, marginal and medium-sized farms andwere supplemented by hired labour during the peak seasons.However, large farmers were mainly dependent on hired labourfor agriculturaloperations. A rise in the income of rural house-holds increased the capacity of the farm households to employinnovations to furtherexploit the potential of yield increases andenhance income from agriculture. Thus, the new innovations ofthreshing, cultivation of land through tractors, use of pesticidesand insecticides, diesel pump sets and electric tube wells in-creased the use of mechanical power for tilling and harvestingoperations. Also biological innovations for making crops freefrom weeds and pest attacks started reducing the role of familylabour in farm operations.lThe consequence of the increase in mechanisation, assuredirrigation, chemical fertilisers, pesticides and insecticides andhigh-yielding seeds was a manifold rise in land productivity anddecline in the intensity of labour. Crop yield increased at a rateof 2.43 percent perannumduringtheperiod 1967 to 1981, whichconstituted 40.91 per cent of total land productivity. The con-tributionof crop yield further increased at a rate of 2.71 percentper annum during the post-green revolution period (1981-91)which was 52.52 per cent of the total land productivity. In thestagnation period (1991-2001), yield growth declined to 0.26 percent and the contribution to land productivity also declined to31.33 per cent [Singh and Sidhu 2004].The labouruse patternalso underwent substantialchanges dueto the intensive use of biological and mechanical technologies.The mandays of labour use declined after the mid-1980s in thewheat crop from 52.35 to 38.9 perhectare during 1985-88-1998-2000, that is a 25 per cent decline. It is amazing to note thatlabour use in paddy crop has sharply declined from 103.60mandays per hectare in 1981-84 to 56.32 mandays per hectarein 1998-99. Mechanical harvesting was fundamentally respon-sible for the sharpdecline in intensity of labour use in predomi-nant crops of Punjab agriculture [Sidhu and Singh 2004].Mechanisation of harvesting of major crops and intensive useof biological technologies have not only reduced the householduse of labourpower but also substantially contributed to the risein the cost of production.Overcapitalisation of mechanical powersuch as tractors and tube wells has made available the use ofthe tractoron a hire purchase basis to the small farmers whichhas reduced the use of family labour as well as completelyeliminated tilling of land by bullocks even by the small andmarginal farmers. The farmers have turned managers of theproduction processes of agriculture because the manual opera-tions have been almost eliminated and the remaining tasks arebeing done by the migratory workforce available at low levelof wages.Rising costs along with stagnant technology and a near freezein the minimumsupportprice of wheat and paddy, which turnedthe already adverse terms of trade from bad to worse, surelyreduced returns on foodgrain production. The reduction of dif-ferentials between returns and cost of production, the increasinguncertaintyof weather as well as adependence on borrowed creditata higherrate of interest from informal lenders were the reasonsresponsible for increasing indebtedness among the farmers ofPunjab [Shergill 1998; Ghuman 2001; Gill 2004a]. This hascompounded problems to the extent that farmers of Punjabresortedto committing suicides [AFDR 2000]. The whole crisisis theconsequence of the fact that market forces operatedat much

larger scale during the phase of liberalisation and globalisationand thus reduced surpluses and increased costs leading to thedistress sale of the paddy crop over a nearly five-year periodduring Akali Dal rule in Punjab. The incidence of suicides inPunjab increased tremendously during this period.

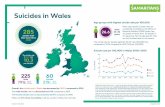

IIFarmers' uicides:Extent ndDiagnosisSuicides by farmers were first highlighted by the media inKerala, Kamataka and Andhra Pradesh. But then came reportsof suicides by farmersin Punjab,which were perturbingandquite

unexpected in such a prosperous region. So long as suicideremains an occasional and stray incident, it does not generatemuch public concern. But when the incidence shows an upwardtrend and affects a particular section of society, it becomes apublic issue, to be viewed, studied and analysed in all its seri-ousness. InPunjab,suicides by the farmersbecame a public issuesince the mid-1980s. The state government itself has admittedthat 2,116 suicides had taken place since 1986, but this couldjust be the "tip of an iceberg" as many more cases might havegone unreported, if not unnoticed [Tribune 2005].The gravity of the problem in Punjabhas been highlighted bythree main studies: by the Institute for Development and Com-munication (1998), followed by Iyer and Manick (1999), andby an NGO, the Association for Democratic Rights (2000)..Table 3 gives the main profile of suicide victims in the surveyareas of the three studies.The studies reveal thatSangrurandMansa arethe two districtswhich have reported the most incidents of suicides. These arethe relatively backward and poorer districts of Punjab. But, asnotedearlier, this by no way is an indication thatsuicides in otherdistricts have not takenplace - the numbercould be muchsmallerand might have gone unnoticed and unreported. Table 3 alsoreveals that the percentage of cultivators who committed suicideis much more than agricultural labourers. And among the

Table 3: Profile of Suicide VictimsStudyby Characteristics IDC lyerand AFDR(1998) Manick1999) (2000)Districts urveyed Gurdaspur Sangrur Patia'aSangrur MansaMansa SangrurLudhiana BathindaVillagescovered 14 11 29Householdscoveredwithconfirmedcases of suicides 53 75. 79Percentageof cultivatorswhocommitted uicide 55 66.66 84.80Percentageof agriculturelabourhouseholds 45 33.33 15.20Percentagef smallandmarginalarmers 25 84 65.70Percentageof illiterates 58.50 66.25 75Percentageof married ictims 81.10 - 76Causes of suicides: (percentage)(i) Multiplef which ndebtednesssone 38 78.75 62(ii) Crop ailure 1.05 10 5.10Debtexclusively romcommissionagents (percent) 36.72 67.50 27.40Debtfromcommissionagentsandothersources - 81.25 73.60

Unproductive se of loan (per cent) 68.20 51.61 20.00"Note:*Comprisespercentageof victimswho could not repaybackloan dueto the reasons ike xpenditurensocialceremonies,excess consumptionand illness, which are conventionally regarded as unproductiveexpenditures.

2764 Economicand Political Weekly June 30, 2006

-

7/27/2019 Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

5/8

cultivators, it is thecategory of small andmarginalfarmers whichreportedthe maximum number of suicides. Most of the suicidevictims were illiterate. The causes of suicides, of which indebt-edness figured prominently, were multiple. The other factorsincluded economic distress, crop failure, alcoholism, maritalanddomestic discord, drug addiction, etc. All these causes, in oneway or the other, pointed towards the poor economic status ofthe victims which manifested itself in various ways. Indebtednesswas more towards non-institutional sources of finance, in whichcommission agents figured prominently. This fact has beenestablished earlier also in the studies of Shergill (1998); Gill(2000); Gill and Kaur(2004); and NSSO (2005). Also, most ofthe loans (from institutional as well as non-institutional sources)of these victims were used for purposes that are traditionallyclassified as unproductive - social ceremonies, illness, houseconstruction, etc.The twin aspects of indebtedness fmostly to informal lenders)and the "unproductive"use of loans need to be studied simul-taneously in greater detail to analyse the true reasons behindsuicides. One side of the picture is that with the ushering in ofthe green revolution, the incomes of all classes of farmers in-creased initially, which set off the aspirations of cultivators tolead a better life in terms of living conditions and consumption.Always one to be on the ostentatious side of life, the Punjabifarmer, especially in the Malwa region (Bathinda, Faridkot,Sagrur,Mansa,Patiala andLudhiana)now freely startedspendinglavishly on social ceremonies. Dowry in marriages invariablybegan to include a car, among other things. If there was a paucityof funds, there was always. the informal lender, willing to giveloans in substantial amounts. Or even a tractor loan from insti-tutional sources could be used to give dowry. The beginning anddeepening of economic crisis in agriculture shrunk the incomesof peasantry,but not their aspirations and the firmly entrenchedsocial norms. Failure to pay back loans indebted them further,entrapping hem in a debt trap.Harassmentby lenders, the threatof arrestand then the public shame accompanying the impendingcompulsion to forsake their most prized asset - land - provedto be the last nail in their coffins.A second but important aspect of the problem of the so-calledunproductive use of loans (mostly informal loans) raises thequestion as to how to define the term "unproductive"?Recallingthe crisis in agriculture once again, the spending of loans forsurvival - essential consumption, for medical expenses, and forbuilding a roof over one's head - is notjustifiably unproductive.Spending for maintaining/enhancing one's productive capacityhas now beenrecognised asvery productive expenditures [Straussand Thomas 1995]. If an in-depth disaggregative analysis of theloan use is made, instead of just the two broad conventionalcategories, then a substantialproportionof the loan use classifiedas unproductivecould possibly be deducted. The expenditure onmarriages and other social ceremonies are safely classified asunproductive.Butthen,why is only one section of society singledout andchastised for spending on marriages when the entire setup of the Punjab state is under the influence of this social evil.Farmerscannot be studied and analysed in isolation from what ishappening in society at large, because they are not autonomousfromthesocial structure, ndtheiractionswill be influenced largelybythesociety ingeneral.The problem is thatfarmers,unlike mostothersectionsof society, do not haveregular,assured ncomes; andwhatever thfy earn is shrinking by the day. Suicides due to drugabuse, alcohol and domestic ormaritaldiscord are ust reflectionsof thismalaiseof economic crisis with grave social consequences.

Also, a less notedandthoughtof, albeitequallytrue side ofthepicturewhich s much essreported,s thatnotall loans,eveninformal oansaremisused.Yeta majority f thepeasantryandlandlessworkers) re n a graveeconomicsituation. t has beenestablishedby micro-empiricaltudies hata majority f borro-wingsof cultivatorsreused orproductive short-termnd ong-termpurposes.Gill(2000);Gill andKaur2004)haveestablishedthatnearly63 percentand57 percent,respectively f informalcreditwas utilised orproductive urposesTable4). It wasonlyin the caseof landlessworkershata greaterpercentage f loanswere utilised orconsumption r repayment f old debts.Apartfrom thesestudies,the NSSO data too confirm hat in Punjab,of everyRs 1,000of outstandingoans takenbyfarmers,Rs 264was forcapitalexpendituren farmbusiness,Rs 360 forcurrentexpendituren farmbusiness,Rs 44 fornon-farm usiness,Rs 85for consumption,Rs 102 for marriagesand ceremoniesandRs 126 for medical and otherexpenditure.For the countryasa whole, the NSSO concludedthat morethan 50 per cent ofindebted armerhouseholdshadtaken oansfor thepurposes fcapitalor current xpenditure NSSO 2005].Theproductive urposesor which nformal oans areutilisedis for repair, uel, maintenance nd hiringof machinery,ubewells andpumpsets.Theexpenditure n these cannotbe post-ponedduring eak easons,and t isonlythe nformaloanswhichareimmediately vailable.The institutionaloans,on theotherhand,usuallyhave a credit imit(seton the basisof owned,notcultivatedand),andarereadilyavailableonlyafter he first oanis repaid.Hence,the cultivatorshave no optionbut to turntotheinformalenders,whereredtapismandlengthypaperworkseldom xist,unlike he nstitutionaloans.Moreover,ormal reditisnotable o fulfil heentire reditdemands f cultivators. able5bearsanampleproofof this. For mostcategories, hesupplyofformal credit is not even 50 per cent of demand or credit.The wholesituation, hus,has tobeviewed na broadermacroframework f the needs of farmersand the set upto fulfil theseneedsratherhanonlimitingourselves ostudyingusttheprofileof suicidevictims,so that the menacecan be checked beforeassuminggiganticproportions.n theagriculturalet-up,borro-wing is a necessity.It is neitherobjectionablenor a sign ofweakness. t is thefailureof the institutional etupin supplyingcreditcommensurate ithdemand hat s mainlyresponsibleorthe crisis and ts manifestationn the formof suicides.Commis-sion agentsarethrivingas informal endersbecausetheyhavechosencrop,rather han and,as collateral,andenticefarmersinto nterlinkedontracts pledgeofsaleofcrop n returnor loan[Gill2000;Bell and Srinivasan1989].Crop s not undervaluedas landis, but the rates of interestare keptexorbitantlyhigh

Table4: Utilisationof InformalCreditby Sample Households(Per cent)

Size-groupof Owned Produ/tive ConsumptionHolding Acres) Purp6se PurposesPatiala Amritsar Patiala AmritsarLandless 4.28 49.64 64.11 50.36Upto 2.5 70.23 47.29 29.77 52.712.51-5.00 51.41 48.74 45.92 51.265.01-10.00 50.66 81.50 48.26 18.50Above 10 68.95 71.18 29.29 28.82Total 63.03 57.14 36.36 42.86Note: The percentages forproduction nd consumption n case of Patialamaynotaddupto 100, because itexcludes the utilisation f credit orrepaymentof olddebt of cooperativesocieties.Source:Calculated rom ieldsurvey.

Economic and Political Weekly June 30, 2006 2765

-

7/27/2019 Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

6/8

[Gill 2000], while keeping paperwork to a minimum. Landgrabis only in extreme cases, and that too in case of big landlordsturnedcommission agents. But harassment, threats,fear of arrestand the public shame is enough to drive the borrowers to suicide,even thoughtheloan mightnothave been used "unproductively".Hence, suicides as a manifestation of indebtedness in particularand agrariancrisis in general have to be viewed and analysedin a broad macroeconomic framework. It has to be realised thatthe root cause of the problem lies not just under the cursoryheading of indebtedness; it has to be traced back to the entirecredit set-up and then the crisis within the agricultural sector.

IIIHopeandSuggestedPolicyMeasuresDespite the grave situation in which the Punjab peasantry isengulfed, thereis still a rayof hope. Since in the previous section,an attempt was made to diagnose the problem, suitable alter-natives can now be suggested as remedial measures, in the lightof the efforts already made at the level of the state. Since theagrarian risis has manifested itself in suicides, theproblemneedsto be tackled at various levels, beginning from the immediate

relief measures to the families of suicide victims, to long-termpolicy decisions covering the entire agricultural sector.As a part of the immediate relief package for the families ofsuicide victims, there is a need to provide monetary assistanceascompensation so thattheaggrieved family can meet its physicalsurvival needs. This is all the more importantin the cases wherethe victim was the only earning member of the family. Properidentification of such families by a non-partisan organisationmust precede such financial compensation. Additional financialcompensation can also be provided by voluntary organisationsand NGOs. Since most of the suicides are directly or indirectlyrelated to indebtedness and economic distress (not necessarilyin this order), it is proposed that a moratorium on.the debt ofthe victim be implemented. Also the rate of interest and the loaninstalments need to be substantially lowered thereafter.In casethe victim was the sole earning member, waiving off the entireloan - formal or informal - would be highly recommendable.2Again, takingacue from the relief measuresprovidedto suicidevictims in Andhra,a pension scheme to the next of kin (especiallyif he/she is aged and/or a non-earner) should be implemented.As part of longer-term relief measures, it is suggested thatprovisionforcost-free skill-oriented education be made for minorchildren.Olderchildrencould beprovidedsuitableemployment torehabilitate the family. This would also ensure that the victim'sfamily is made capable of paying off the debt and live a life ofhonour,havingwashed off thestigmaof beinga suicidevictim's kin.The growing agriculturalcrisis and its manifestations have notgone entirely unnoticed, with the Punjabgovernment appointingacommittee asearlyas in 1985 under thechairmanshipof S S Johlto diagnose the problem and suggest remedial measures. Thecommittee put forward the idea of diversification of agriculturefrom the existing wheat-paddy cropping pattern[GovernmentofPunjab1986]. It was argued that this diversification from cerealsto fruits, vegetables andpulses will not only increase the incomeof farmers, but also reduce environmental degradation for long-term sustainability of Punjab's agriculture. It may be recalledthat this agriculture diversification based rural industrialisationgrowth strategy met with success in the early 1980s in a numberof south-east Asian countries. The Punjab government recentlytried to promote diversification of agriculture by taking on the

path of contract farming, between farmers and the agribusinessfirms [Singh 2004]. However, the very design and implemen-tationof contractfarmingleft the small-sized farmersat the mercyof the private firms which secured monopoly situation in themarket. In the absence of enforcement agency, such profitconsiderations and market orientation acted-against the farmersandthey have been left with no choice but to continue the wheat-paddy cropping pattern [Gill 2004b].Diversification of agricultureof Punjabis, no doubt, a desiredgoal fortransformationof theeconomy into an industrialisedone,but so long as theprocessing activities of agricultureproductiontake place away from the farm gates, the agriculture sector willcontinue to face the threat of exploitation and a decline in ruralincomes [Timmer1988; Singh 2005]. The south-eastAsian coun-tries in general and Taiwan in particular,have been the successstories because agriculture produce was processed on the farmgates andsurpluseswere ploughed backto expand rural ndustrialactivities and also raising the level of living of the ruralpopu-lation. The farmers' association of Taiwan successfully bypassedtheexploitative intermediaryagency. The state too played its roleby providingessential institutionalinfrastructureand investment.The organisation of production, thus has to be changed fromindividual to cooperative - not the bureaucratic state-controlledcooperative but modern member-owned and controlled coopera-tives. Amul in ourown countryis an example of one such coope-rative. The farmers'cooperative in Junnar alukain Maharashtrafor industrialisation of grapecultivation is another success story.The government of Punjab, too, needs to offer a strategy whichis not purely private and marketbased, but which leads farmersto organise themselves to carry out production, processing andmarketing. For this, suitable institutional and infrastructuralarrangementsandelimination of middle manhereto be provided.

Specifically, addressingthe problem of credit, there areno twoviews that it is the middleman - who is exploiting the farmersthe maximum and leading them into a debt trap.The remedy liesin the provision of institutional credit at cheaper rates of interestand, more important, at levels commensurate with the demandfor credit. Although the recommendations of the NarasimhamCommittee(1991) regarding owering of prioritysector (of whichagriculture is a very importantpart) target of bank credit from40 percent to 10percent was notapproved by thepoliticalmastersin our country, the monitoring and fulfilment of 'targets havebegun to be taken much less seriously. This is not desirable,keeping in view of the grave economic situation of agriculture.To aggravate the situation, the priority sector list is being regu-larly revised to the detriment of small and marginal farmers[Dasgupta 2002]. For instance, in the category of direct advancesto agriculture, the acquisition of jeeps, pick-up vans, etc, havebeen included - vehicles that areminimally made use of by smalland marginal farmers. Again, the target of 18 per cent of directadvance is now being fulfilled by including a certain percentage

Table 5: Supply of Formal Creditas Percentageof Demandfor CreditSize-Groupof OwnedHolding Acres) Patiala AmritsarLandless 10.77 14.58Upto 2.5 27.12 61.932.51-5.00 49,51 41.435.01-10.00 24.96 40.07Above 10 75.11 67.75Total 47.85 43.67Source:Calculated rom ieldsurvey.

2766 Economicand PoliticalWeekly June30, 2006

-

7/27/2019 Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

7/8

in the form of indirect credit [EPWResearch Foundation, SpecialStatistics 2003; TNS 2003]. That the supply of institutional creditis much less than demand has already been mentioned earlier.The Punjab government's recent measure to revise the 1997vintage land rates taken into account by cooperative banks forlending purposes has enhanced the loan availing capacity offarmers and is a step in the right direction, but the inclusionelement of landownership as a basis for a loan and that tooprocessedwith considerable redtapeanddelays arestill aproblem.A lower rate of interest is of no use if the loan is not adequate,timely and without the additional costs of procuring it. Theseadditional costs involve cost of frequent visits to the institution,payment of a fee, submission of documents (requiring paymentto some 'munshi' who can do the paper work for the illiteratefarmers), etc. These expenses, if added to the rate of interest,make formal borrowings quite expensive.On the other side are the informal lenders - mainly commissionagents - who charge exorbitant rates of interest but provide aneasy finance, commensurate with demand, while linking sale ofcrop to loan amounts. These practices are highly exploitative,but the farmers are forced to borrow from them out of sheernecessity. To serve ruralcredit needs, the experiences of Indo-nesian rural financial institutions, where organisations providecreditservices locally, with character-based ending [ChavesandGonzalez 1996], or like the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh canbe adaptedto Indian needs. And most importantis the delinkingof politics from credit, which turns loans into grants with everyelection, making the task of credit institutions difficult. Thesolution to indebtedness will go a long way in solving the entireagrarian risis. Among othermeasures, it is suggested that formalinstitutions would do well to shift to crop as collateral, insteadof insisting on land ownership, especially for long-term loans.This would ensure that the credit is need-based. Farmersshouldalso be provided crop insurance at par with what is availableto industry, as agriculture is the sector most vulnerable to thevagaries of nature. Failure of crops almost always renders thefarmers ncapableof paying backthe loan instalment, andif cropsfail in two or more consecutive seasons, farmersinvariably findthemselves in a debt trap. This is exactly what is happening insome parts of Punjab, where the fury of the Ghaggar river (inthe Malwa region where the maximum suicides have beenreported)during monsoons wreaks havoc year after year.Apart from this, since the farmers cannot escape certain ex-penditure on consumption, health and even social ceremonies,efforts can be made to set up a pool of separate funds, withmatching contributions from the farmers and the government,which can then be used to give interest free loans specificallyforsuch expenses as mentioned above. This pooling can be doneat thevillage level, by thepanchayatsorsome such organisations.Funds can be loaned out to member farmerson a rotational,need-based or lotterybasis if the fund pool is small. The idea can beroughly similar to the chit funds or nidhis operating in urbanareas.However, the success of such a scheme will depend purelyon the farmers and the honesty with which they operate thescheme. If such schemes can be successfully implemented, thenfarmerswould not need to "misuse" the borrowings from insti-tutions or avail of informal loans for "unproductive"purposes.Since it has already been argued that despite using a majorportionof theborrowings for "productive"purposes, farmers arefalling into a debttrap,steps have to be taken to addresstheentirecredit needs of farmers and the very set-up of credit providingagencies - formal, as well as informal.

It s alsonecessaryhat hegovernmenttarts hinkingn termsof setting up some sort of cooperativeorganisationo hireoutagricultural achinery tractors,hreshers ndharvest ombines- on subsidised ates.This will save a lot of expenditureorthefarmers.Evenfor rrigation,t shouldnot benecessaryhateveryfarmer pendson installation f tube wells andpumpsets in-dividually.Government-installedubewells, collectively oper-atedby farmers an serve thepurpose. n view of thedecliningwater able n Punjab, ubmersible umpsets (deeptubewells)needto be installed.The installation ost of submersible umpsets is beyondthe financialcapacityof thesmall andmarginalfarmers.fsuchpumpetsarenstalledy hegovernment,aterusewouldbe more quitably istributed,n additionosavingofcosts.IVConcluding emarks

The structuralransformationf an economy involves thereducing mportance f theagrarianectorthat s thereductionof the workforcedependenton agriculturewhile shiftingsur-pluses othemoredynamic ectorof theeconomy hat s industry.ThePunjab conomy s undergoing transformationeading oa gravecrisis,insteadof becominga healthysign of capitalisteconomicdevelopment.Thisis becausewhilethesurpluses rebeing rapidlyextracted, he dependenceof the workforceonagricultures still veryheavy.The situation s aggravated ueto decliningproductivity nd incomein this sector.The onsetof the greenrevolutionhad given a tremendousboost to theeconomybybringing harpncreasesnincomes,productionndproductivityor all classesof agriculturists. owever, he boostwas short-lived withproductivity ecliningover a periodoftime, incomedippingdue to increased osts of production utanear reeze n minimumupport rices,andwith argenumbersrenderedunemployeddue to mechanisationof agriculturaloperationsand lack of alternative mploymentopportunities.Nearstagnationn the agriculturalector andnon-descript e-velopment f the other ectorsof theeconomysaw thebeginningof a crisiswhichhasreached nprecedentedravity, o theextentthatcultivatorswereforced to take theirown lives rather hanlivealifeofextreme overty,mounting ebtburden nd heagonyof not beingable to pay back the debts.Thismanifestationf theagrarianrisis n theformof suicideshas reacheddangerousevels in Punjab. ntensive ieldsurveyscarriedout to gaugethe gravityof the problemas well as itscausespointedout thatmostof the suicide victims wereculti-vatorsandbelong o thecategoryof smallandmarginalarmers.Suicides were attributedo a numberof reasons,ranging rompoverty o cropfailure, ndebtedness,maritaldiscordandalco-holism,but nourview it wasmainlydue to theeconomiccrisisthat hepeasantry,nPunjab,ngeneral, s facingandwhichhasled themto borrowheavily.The heathas beenfelt moreby thesmall andmarginalarmers, incetheyare at a disadvantageouspositionso far as borrowingrominstitutional ources s con-cerned,and landownership s a criteria or borrowing.Hencenon-institutionalources,particularlyhe commissionagents,havecome to occupya dominantposition,as theylendon thebasis of crop as collateral,and with minimumpaperwork.Although,contraryo popularbelief, much of the borrowings(frombothsources)areused for what are traditionally nownasproductive urposes.Yet,thepeasantrys underdebtpressurebecause ncomes romagriculturalropsarenotenough o meetsurvivalneedsas well asrepaymentf loan nstalments.fother

Economic and Political Weekly June 30, 2006 2767

-

7/27/2019 Gill Andd Singh Farmers Suicides

8/8

reasons are given, they are just essential links in the chain ofeconomic difficulty leading to borrowing and indebtedness, andthen the pressure - of family, of lenders, even mental pressure- of returning the loan or face public shame and humiliation,not to speak of threats of land grab.Remedies thus have to be found not only in terms of short-term or immediate solutions to suicides, but also long-termsolutions to end theagrarian risisitself. While immediatemeasurescould include relief, mainly financial, to the families of suicidevictims,andattemptsat theirrehabilitation, helong-termmeasuresto "nip the evil in the bud" should comprise attempts at ruralindustrialisation.This could be done on the lines of how and whathasbeen undertaken neast Asian countries especially inTaiwan.The farmers'cooperatives, sans middlemen, to produce, processandmarketoutputon the farmgates can be a way out. This wouldnot only provide the agricultural sector with a much neededdiversification from the wheat-paddy rotation, but also prove tobe remunerative in terms of incomes and employment. Thefarmers'organisationsmustengage themselves to startcollectivelyprocessingandmarketingenterprisesrather hanpurely dependingonagitations ormoreremunerativeprices. Asking forrights alongwithengaging inindustrialactivities has acapacitytoeliminate themiddlemen who thrive on surpluses generated througprocessingand marketing activities. The state government apartfrom sup-porting and extending cooperation must become innovative toarticulatepolicies in the fast globalising world to prod farmers'organisations to initiate those activities which integrate theprocessing and marketing activities on the farm gates. This alsounderlinesthatthe state andstate-runfinancial institutions wouldhaveto alter heirsystem of lending- loans would have to be madeadequate, imely, cheap, andcommensuratewith demand. The redtapeandadditionalcosts involved, which make institutional oansso unattractive, would also have to be reduced drastically. l3Email: gill_anita2003 @yahoo.comlkhw2002 @yahoo.com.NotesI It is importanto note here that theelectric tube wells installedin Punjabhave been increasing continuously from 1.46 lakh in 1976 to 2.83 lakhin 1981 and were more than8.29 lakh in 2002 which is nearlya sixfoldincrease. This increasein the rate of growth of numberof electric tubewells could not satisfy the demand because a substantial number ofapplicationsemained ontinuouslypendingwiththe stateelectricityboard[ESO2002]. The numberof tractors n Punjabhas increased o 3.87 lakhwhich constitutesone-fourthof the totalnumberof tractors n India and

everythird arm household hasa tractorkeeping in view 11.17 lakh totaloperationalholdings in Punjab [Singh 2004].2 Itneeds o bepointedoutat hisstage hat hePunjab lanningdepartment adannounceda compensationof Rs 2.5 lakh in its annualPlan of 2001-02,but thispromisehasyet to be fulfilled,unlike the case of AndhraPradesh.In fact, highly moved by the state's apathy,a petitionhas been filed bytheMovementagainstStateRepression MASR)inthePunjab ndHaryanaHigh Court seeking instructions to the Punjab government and thegovernmentof Indiato compensateand rehabilitate amilies of farmerswho committed suicides in the state (The HindustanTimes,January21,2005).

ReferencesAFDR (2000): Suicides in RuralArea of Punjab:A Report(in Punjabi),Association for Democratic Rights, Ludhiana.Bell, Clive and T N Srinivasan(1989): 'InterlinkedTransactions n RuralMarkets:An EmpiricalStudy of AndhraPradesh,Biharand Punjab',OxfordBulletinof Economics and Statistics, Vol 51, No 1.

Bhalla,G S et al (1998):Suicidesin RuralPunjab,Institute orDevelopmentand Communication,Chandigarh.Bhalla,G S andG KChadha 1983): GreenRevolutionandtheSmallPeasant:A Study of Income Distributionamong Punjab Cultivators, ConceptPublishingCompany, New Delhi.Chaves,R A and Gonzalez-Vega(1996): 'The Design of Successful RuralFinancial ntermediaries: vidence romIndonesia',WorldDevelopment,Vol 24, No 1.Dasgupta, R (2002): 'Priority Sector Lending: Yesterday, Today andTomorrow', Economic and Political Weekly,38(41).EPWResearchFoundation 2003): 'Money, Bankingand Finance:SpecialStatistics-33',Economic and Political Weekly,38(8).ESO(2002):StatisticalAbstractof Punjab:PublicationNo880, Governmentof Punjab, Chandigarh.Ghuman,R S (2001): 'WTO and IndianAgriculture:CrisisandChallenges:A Case Study of Punjab',Man and Development,June.Gill, Anita(2000): RuralCreditMarkets:Financial SectorReformsand theInformalLenders,Deep and Deep Publishers,New Delhi.- (2004a): 'InterlinkedAgrarianCredit Markets:Case Study of Punjab',Economic and Political Weekly,39(33).Gill, Anita and Gian Kaur(2004): 'InformalAgrarianCredit MarketsanaPublicPolicy:EmpiricalEvidence fromPunjab',TheGlobal JournalofFinance and Economics, 1(2).Gill, Sucha Singh (2002): 'EconomicReforms,Pace of DevelopmentandEmploymentSituationnPunjab' nIAMR ed),Reform ndEmployment,Concept Publishing Company,New Delhi.- (2004b): 'ContractFarmingHurts Farmers:Area underWheat, PaddyIncreases',The Tribune,Chandigarh,September27.Government of Punjab (1986): Report of the Expert Committee onDiversification of Agriculture in Punjab, Government of Punjab,Chandigarh.Iyer, K GopalandM S Manick(2000): Indebtedness, mpoverishmentndSuicides in Rural Punjab,India Publishers and Distributors,Delhi.Lewis, W A (1954): 'EconomicDevelopmentwith UnlimitedSupplies ofLabour',Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies, 22.Mellor,J W (1976): TheNew Economicsof Growth:A Strategy or Indiaand the Developing Countries,Cornell UniversityPress, Ithaca.NarasimhamCommitteeReport(1991): Report of the Cbmmitteeon theFinancial System,Govermmentof India,New Delhi.PlanningCommission(2003): PunjabDevelopmentReport,GovernmentofIndia,New Delhi.NSSO(2005);Indebtedness fFarmerHouseholds,NSS59thRound,January-December 2003, Report No 498(59/33/1), National Sample SurveyOrganisation, Ministryof Statistics and Programme Implementation,Governmentof India,May.Shergill,H S (1998): RuralCreditand Indebtedness n Punjab,Institute orDevelopmentand Communication,Chandigarh.Sidhu,RSandSukhpalSingh(2004): 'AgriculturalWagesandEmployment',Economic and Political Weekly,39(37).Singh, Joginder and R S Sidhu (2004): 'Factors in Declining CropDiversification',Economic and Political Weekly,39(52).Singh, Lakhwinder 2005): 'Decelerationof IndustrialGrowthand RuralIndustrialisationtrategy orIndianPunjab',Journalof PunjabStudies,(forthcoming ssue).Singh, Lakhwinderand SukhpalSingh (2002): 'Decelerationof EconomicGrowthin Punjab:Evidence, Explanationand a Way-Out', Economicand Political Weekly,37(6), February9.Singh, Sukhpal(2004): 'Crisisand Diversificationin Punjab Agriculture',Economicand Political Weekly,39(52).Strauss, andDuncanThomas 1995):'HumanResources:EmpiricalModellingof Householdand Family' in Jere Behrman andT N Srinivasan(eds).Handbook fDevelopmentEconomics,Vol3A,ElsevierSciencePublishers,Amsterdam.

Syrquin,Moshe (1988): 'Patternsof StructuralChange' in Hollis Cheneryand T N Srinivasan eds), Handbookof DevelopmentEconomnics, ol I,ElsevierScience Publishers,Amsterdam.The HindustanTimes(2005): 'Suicide by PunjabFarmers:Relief for KinSought, The HindustanTimes,Chandigarh,January22.Timmer,C P (1988): 'The AgricultureTransformation' n Hollis Cheneryand T N Srinivasan eds), HaIndbookf DevelopmentEconomics,Vol I,Elsevier Science publishers,Amsterdam.TNS (2003): 'MarketImperfectionsand FarmersDistress in Punjab'.TheTribune,Chandigarh,December 23.Tribune(2005): 'Suicides by FarmersBeing Underplayed: Report', TheTribune.August 10.

2768 Economic and PoliticalWeekly June30, 2006

![Psychopathic Suicides [solo cello]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/577cdb691a28ab9e78a81e65/psychopathic-suicides-solo-cello.jpg)