General History of medieval Europe for students of architecture

-

Upload

suranjanac -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

1

description

Transcript of General History of medieval Europe for students of architecture

Note 1 : General History

Page 1 of 8

Timeline of European Architecture

CLASSICAL PERIOD

800BC-400BC Etruscan

750BC-AD250 Ancient Greece

600BC-300BC Ancient Rome

400BC-AD700 Roman

300BC-200BC Early Classical

MIDDLE AGES

AD700-1050 Pre-Romanesque/Early Christian (often referred

to as The Early and Later Dark Ages )

~ Merovingian 475-780

~ Asturian 711-910

~ Carolingian 775-890,

~ Ottonian 950-1050

1000-1250 Kiev

1050-1175 Romanesque

1066-1190 Norman

1120-1220 Romanesque Brick

1150-1550 Gothic

Gothic styles in England:

~ Norman 1066-1200

~ Early English 1180-1275

~ Decorated 1275-1380

~ Perpendicular 1380-1550

Gothic styles in France (Opus Francigenum):

~ Early 1140-1260

~ Late or Flamboyant 1150-1550

~ Rayonnant 1160-1250

~ High 1200-1320

~ Southern 13thC

Gothic in Germany and Eastern Europe:

~ Brick Gothic (Backsteingotik) 1175-1425

Gothic styles in Italy:

~ Development of the Cistercian 1150-1228

~ Early 1228-1290

~ Mature 1290-1385

~ Late 1385-1550

Gothic styles in Spain:

~ Early – 12thC

~ High – 13thC

~ Mudejar – 13-15thC

~ Levantino – 14thC

~ Flamboyant – 15thC

~ Isabelline – 15thC

ITALIAN RENAISSNACE

1400-1600 Renaissance

~ Quattrocento (Early) 1400-1500

~ High Renaissance 1500-1525

~ Mannerism 1520-1600

1475-1600 Tudor

1540-1600 Elizabethan

1600-1780 Baroque

~ Italian 1580-1780

~ Sicilian 1585-1640

~ Russian 1620-1730

~ French 1630-1750

~ English 1660-1715

1600-1660 Jacobean

1620-1700 Palladianism

1725-1850 Georgian

1750-1870 Neoclassical

REVIVALS :

1800-1900 Neogothic

1850-present day Gothic Revival

1870-1900 Romanesque Revival

1900-present day Baroque Revival

1900-present day Modernist

Note 1 : General History

Page 2 of 8

Note 1 : General History

Page 3 of 8

1. MIDDLE AGES

1.1. Middle Ages : Introduction

Petrarch, an Italian poet and scholar of the fourteenth century,

famously referred to the period of time between the fall of the

Roman Empire (c. 476) and his own day (c. 1330s) as the Dark

Ages.

Petrarch believed that the Dark Ages was a period of intellectual

darkness due to the loss of the classical learning, which he saw

as light. Later historians picked up on this idea and ultimately

the term Dark Ages was transformed into Middle Ages. Broadly

speaking, the Middle Ages is the period of time in Europe

between the end of antiquity in the fifth century and the

Renaissance, or rebirth of classical learning, in the fifteenth

century and sixteenth centuries.

1.2. Not so dark after all

Characterizing the Middle Ages as a period of darkness falling

between two greater, more intellectually significant periods in

history is misleading. Compared to the classical civilizations,

this age was bleak. Language, letters, arts, technology, culture,

Note 1 : General History

Page 4 of 8

governance of the classical ages were all lost and it is true that

most of it was not revived until the Italian Renaissance. Still,

the Middle Ages was not a time of complete ignorance and

backwardness, but rather a period during which Christianity

flourished in Europe. Christianity, and specifically Catholicism

in the Latin West, brought with it new views of life and the

world that rejected the traditions and learning of the ancient

world. The developments of this period were built on an

amalgamation of partial revival of Roman culture, the local

tribal culture and the ruling Muslim cultures that were

continually in conflict with the Christian culture.

During this time, the Roman Empire slowly fragmented into

many smaller political entities. The geographical boundaries for

European countries today were established during the later

Middle Ages. This was a period that heralded the formation

and rise of universities, the establishment of the rule of law,

numerous periods of ecclesiastical reform and the birth of the

tourism industry. Many works of medieval literature, such as

the Canterbury Tales, the Divine Comedy, and The Song of

Roland, are widely read and studied today.

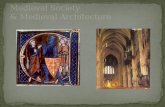

The visual arts prospered during Middles Ages, which created

its own aesthetic values. The wealthiest and most influential

members of society commissioned cathedrals, churches,

sculpture, painting, textiles, manuscripts, jewelry and ritual

items from artists. Many of these commissions were religious

in nature but medieval artists also produced secular art. Few

names of artists survive and fewer documents record their

business dealings, but they left behind an impressive legacy of

art and culture.

1.3. Byzantium

In the medieval West, the Roman Empire fragmented, but in

the Byzantine East, it remained a strong, centrally-focused

political entity. Byzantine emperors ruled from Constantinople,

which they thought of as the New Rome. Constantinople

housed Hagia Sophia, the world’s largest church until 1520,

and was a major center of artistic production.

The Byzantine Empire experienced two periods of Iconoclasm

(730-787 and 814-842) – discussed later, when images and

image-making were problematic. Iconoclasm left a visible

legacy on Byzantine art because it created limits on what

artists could represent and how those subjects could be

represented. Byzantine Art is broken into three periods. Early

Byzantine or Early Christian art begins with the earliest extant

Christian works of art c. 250 and ends with the end of

Iconoclasm in 842. Middle Byzantine art picks up at the end of

Iconoclasm and extends to the sack of Constantinople by Latin

Crusaders in 1204. Late Byzantine art was made between the

sack of Constantinople and the fall of Constantinople to the

Ottoman Turks in 1453.

In the European West, Medieval art is often broken into smaller

periods. These date ranges vary by location.

c.500-800 – Early Medieval Art

c.780-900 – Carolingian Art

c.900-1000 – Ottonian Art

c.1000-1200 – Romanesque Art

c.1200-1400 – Gothic Art

2. Christianity, an introduction

2.1. How little we know

Almost nothing is known about Jesus beyond biblical accounts,

although we do know quite a bit more about the cultural and

political context in which he lived—for example, Jerusalem in

the first century. What follows is an introductory, generally

agreed upon historical summary of Christianity. It hardly needs

stating that there are many interpretations and disagreements

among historians.

2.2. Jesus v. Rome

The biblical Jesus, described in the Gospels as the son of a

carpenter, was a Jew and a champion of the underdog. He

rebelled against the occupying Roman government in what

was then Palestine (at this point the Roman Empire stretched

across the Mediterranean). He was crucified for upsetting the

social order and challenging the authority of the Romans and

their local Jewish leaders. The Romans crucified Jesus, a

typical method of execution—especially for those accused of

crimes against the government.

Jesus’ followers claim that after three days he rose from the

grave and later ascended into heaven. His original followers,

known as disciples or apostles, travelled great distances and

spread Jesus’ message. His life is recorded in the Gospels of

Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, which are found in the New

Testament. “Christ” means messiah or savior (this belief in a

savior is a traditional part of Jewish theology).

2.3. Old and New Testaments

Early on, there were many ways that Christianity was practiced

and understood, and it wasn’t until the 2nd century that

Christianity began to be understood as a religion distinct from

Judaism (it’s helpful to remember that Judaism itself had many

different sects). Christians were sometimes severely persecuted

by the Romans. In the early 4th century, the Roman Emperor

Constantine experienced a miraculous conversion and made it

legally acceptable to be a Christian. Less than a hundred years

later, the Roman Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the

official state religion.

The first Christians were Jews (whose bible we refer to as the

Old Testament or the Hebrew Bible). But soon pagans too

converted to this new religion. Christians saw the predictions of

the prophets in the Hebrew Bible come to fulfillment in the life of

Jesus Christ—hence the “Bible” of the Christians includes both

the Hebrew Bible (or the Old Testament) and the New

Testament.

In addition to the fulfillment of prophecy, Christians saw parallels

between the events of the Hebrew Bible and the New

Testament. These parallels, or foreshadowings, are called

Note 1 : General History

Page 5 of 8

typology. One example would be Abraham’s willingness to

sacrifice his son, Isaac, and the later sacrifice of Christ, God’s

son, on the cross. We often see these comparisons in Christian

art offered as a revelation of God’s plan for the salvation of

mankind.

2.4. Different Christianities

Unlike Greek and Roman religions (there was both an official

“state” religion as well as other cults), Christianity emphasized

belief and a personal relationship with God. The doctrines, or

main teachings, of Christianity were determined in a series of

councils in the early Christian period, such as the Council of

Nicea in 325.

Nevertheless, there is great diversity in Christian belief and

practice. This was true even in the early days of Christianity;

today there are approximately 2.2 billion Christians who belong

to a multitude of sects.

The two dominant early branches of Christianity were the

Catholic and Orthodox Churches, rooted in Western and

Eastern Europe respectively. Protestantism (and it’s different

forms) emerged only later, at the beginning of the sixteenth

century. Before that there was essentially just one church in

Western Europe—what we would call the Roman Catholic

Church today (to differentiate it from other forms of Christianity

in the West such as Lutheranism, Methodism etc.). Christianity

spread throughout the world. In the 16th century, the Jesuits (a

Catholic order), sent missionaries to Asia, North and South

America, and Africa often in concert with Europe’s colonial

expansion.

2.5. Christian Practices :

Christianity holds that God has a three-part nature—that God is

a trinity (God the father, the Holy Spirit, and Jesus Christ)* and

that it was Jesus’s death on the cross—his sacrifice—that

allowed for human beings to have the possibility of eternal life in

Heaven. In Christian theology, Christ is seen as the second

Adam, and Mary (Jesus's mother) is seen as the second Eve.

The idea here is that where Adam and Eve caused original sin,

and were expelled from paradise (the Garden of Eden), Mary

and Christ made it possible for human beings to have eternal

life in paradise (heaven), through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.

Christian practice centers on the sacrament of the Eucharist,

which is sometimes referred to as Communion. Christians eat

bread and drink wine to remember Christ’s sacrifice for the sins

of humankind. Christ himself initiated this practice at the Last

Supper. Catholics and Eastern Orthodox believe that the bread

and wine literally transform into the body and blood of Christ,

whereas Protestants and other Christians see the Eucharist as

symbolic reminder and re-enactment of Christ’s sacrifice.

Christians demonstrate their faith by engaging in good

(charitable) works (works of art—like the frescos by Giotto in the

Arena Chapel—were often created as good works). They often

engage in rituals (sacraments) such as partaking of the

Eucharist or being baptized. Traditional Christian churches have

a hierarchical structure of clergy. Clergies are authorises or

ordained people who can perform religious rites. Devout men

and women sometimes take vows of chastity, obedience and

poverty become nuns or monks and may separate themselves

from the world and live a cloistered life devoted to prayer and

good deeds in a monastery or abbey. All monks may not be a

clergy i.e. he may not have the authority to perform religious

duties.

Around 8-9th century, to spread Christianity among illiterate

people, the lure of eternal heaven and fear of eternal burning

hell after death was used as a strong motivator by the clergy.

The propriety of any action could be judged by whether is a sin

or a good deed. A person’s entire life came to be judged by

whether it will ensure his stay in heaven or send him to hell.

2.6. Christianity in Europe

Christianity in Europe was prevalent and spreading after it

was made the state religion by Constantine in early 4th

century. Eastern Empire maintained the dominance of

Christianity. Once the Germanic prince of Rome adopted

Christianity, West Europe was slowly Chirstianising. The

Franks were one of the firsts to convert to Christianity and to

spread the religion. The Franks originated from Scandinavia,

settling in Germany and moving towards present day

northern France. Frankish ruler Charlemagne was a devout

Christian and an able ruler who unified many of the tribes

under his rule. Even though the his grandfather was the first

most major emperor of this family and the one who ensured

in battle of Tours (733) that the Muslims do spread into

Europe from Spain, the Carolingian dynasty was named after

Charlemagne (Charles the Great or, in German, Carolos

Magnus). Seeing him to be a charismatic ruler and a devout

Christian Bishop of Rome, i.e. the Pope seized this

opportunity to strengthen the ties between Church and state.

In 800, on Christmas, when Charlemagne was attending

Mass in Rome, the Pope crowned him the Holy Roman

Empire (the term was coined later). After the sack of Rome in

476, more than three centuries later, there was thus another

empire in west Europe that was Christian and was tied to

Rome by the verdict of Pope. From this period onwards, the

Franking emperors and the Ottonians were spreading

Christianity in West Europe, converting the fragmented tribes

to Christianity by penalty of death. In 1066, William the

Conqueror, a Norman (i.e. from Normandy or north of

present day France) conquered Britain and slowly

Chirstianised the Anglo-Saxons with great effort. Central and

Southern Spain was under Muslim Caliphate upto 12th

Century. Italy was divided between Byzantines, Normans

and Muslims for a long time and their architecture shows a

mix of all style for the medieval and renaissance period both.

Note 1 : General History

Page 6 of 8

2.7. A New Pictorial Language: The Image in Early Medieval Art

Definition of Icons

Icons (from the Greek eikones) are sacred images representing the saints, Christ, and the Virgin, as well

as narrative scenes such as Christ's Crucifixion. While today the term is most closely associated

with wooden panel painting, in Byzantium icons could be crafted in all media, including marble, ivory,

ceramic, gemstone, precious metal, enamel, textile, fresco, and mosaic. Icons ranged in size from the

miniature to the monumental. Some were suspended around the neck as pendants, others (called

"triptychs") had panels on each side that could be opened and closed, thereby activating the icon. Icons

could be mounted on a pole or frame and carried into battle, Alternatively, icons could be of a more

permanent character, such as fresco and mosaic images decorating church interiors.

Icons are not to be confused with surface sculpture and relief in medieval architecture. The sculpture in

medieval period are almost invariably religious, even when they depict apparently non-religious

subjects. The philosophy behind mediaval period of sculpture is fundamentally common with the

creation of Christian icons but the subject matter of icon is limited and subject matter of sculptures are

vast.

Christian art, which was initially influenced by the illusionary

quality of classical art, started to move away from naturalistic

representation and instead pushed toward abstraction. There

was a general feeling that "realistic" art was a falsehood (it's

not what it appears to be). It may lead people to idolatry (idol

worship), i.e. idol-(falsehood-)worship which is against God’s

will. The New Testament prohibits worshipping graven images.

Open hostility toward religious representations began in 726

when Emperor Leo III publicly took a position against icons;

this resulted in their removal from churches and their

destruction. This marks the period of iconoclasm (=removal of

icons) period during the years 726–87 and 815–43 in

Byzantium. This period resulted in the removal / destruction /

plastering over of a great number of icons from byzantine

churches. Once this period was over and icons were re-

admitted in religious architecture, they became extremely

stylized and each posture and colour had certain significance.

In classical art human figure itself was an object of study,

appreciation and artistic presentation. In Christianity, human

figure had strict theological principles. The contemplation of

icons allowed the viewer direct communication with the sacred

figure(s) represented, and through icons an individual's prayers

were addressed directly to the petitioned saint or holy figure.

Miraculous healings and good fortune were among the

requests.

Simultaneously with the religious movement regarding icons,

the classical knowledge of producing realistic images and

sculptures were lost with the fall of Western roman empire.

As a result, artists began to abandon classical artistic

conventions like shading, modeling and

perspective conventions that make the image appear more

real. They no longer observed details in nature to record them

in paint, bronze, marble, or mosaic. Most of the professional

and well-known artists were working for the church, so what

they made was what the church wanted made. So, instead of

realistic art, artists favored flat representations of people,

animals and objects that only looked nominally like their

subjects in real life. Artists were no longer creating the lies, as

these abstracted images removed at least some of the

temptations for idolatry. This new style, adopted over several

generations, created a comfortable distance between the new

Christian empire and its pagan past. The eyes were large and

prominent because they reflected the soul. The raised hands,

facial expressions all represented religious messages.

In Western Europe, this approach to the visual arts dominated

until the imperial rule of Charlemagne (800-814) and the

accompanying Carolingian Renaissance. This controversy over

the legitimacy and orthodoxy of images continued and

intensified in the Byzantine Empire. The issue was eventually

resolved, in favor of images, during the Second Council of

Nicaea in 787.

It should be noted here that the debate over icons are not

limited to Christianity and the abovementioned historical period

alone.

1. EDUCATION AND ARCHITECTURE IN MEDIEVAL PERIOD :

The Carolingian Revival : When Charlemagne became the

king, the scenario of Western Europe was quite bleak in all

senses. There was no education, even among the priests who

gave sermons in churches. Each said his own prayers. The

nobility could not read or write. The Latin language decayed

into what is called Dog Latin, to which even the most educated

person was limited. The Eastern Roman Empire referred to the

westerns as barbarians (after the Barber tribe) and uncivilised

and they continued to do so for centuries afterwards.

Charlemagne changed all this. He was very enthusiastic about

education. He brought Latin scriptures and manuscripts from

Rome, brought teachers from Rome whom he sent to different

corners of his empire where they educated the priests. Often

the nobility also received education. Charlemagne himself

started learning to read and write. Purpose of education was

primarily to spread and preach Christianity. In addition, it was

Note 1 : General History

Page 7 of 8

required to run matters of church as church and monasteries

were self-sufficient settlements themselves. They required

accountants, artisans, masons, doctors and above all people to

preach the religion, train novice monks and copy manuscripts.

The common people were serfs, i.e. that worked in fields and

workshops and they did not require education. Thus the

monasteries came to accommodate schools within the

premisesin the Carolingian period. The revival of education led

to the revival of art, architecture and culture. This revival is

known as Carolingian revival or Renaissance in instrumental

for the germination of Romanesque and Gothic architecture.

The later monarchs were not as enthusiastic or able but the

trend of education continued under the patronage of Royalty

and nobility. As number of towns grew in size and number,

education was also required for operating business as well as

religion.

Early Middle Ages : During the early Middle Ages, any type of

higher education was usually available only in monasteries and

cathedral schools, where Christian monks and nuns taught

each other and preserved the writings of classical authors. But

by the eleventh-century, medieval Europe was becoming more

urban and complex, and royal governments needed highly

trained men to run their bureaucracies. Students and teachers

were also demanding better ways to be educated, and the

solution to this came about with the creation of universities.

Universities come from the Latin word universitas, which

means guild, and these schools were essentially groups of

students and teachers who got together into their own groups

for the purposes of learning -- in some universities it was the

students themselves who paid the teachers and ran the

institution. The main curriculum was based on seven areas -

grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, music, geometry, and

astronomy - all of which were important for a cleric in the

Catholic church. In some universities, other subjects were also

important - Salerno was renowned as a place to study

medicine and Bologna for law.

Later Middle ages : By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries

universities were becoming important centres of learning and

some would become quite famous - like Oxford and Cambridge

in England, and the University of Paris in France. In the later

Middle Ages, universities would emerge in most other parts of

Europe too, as monarchs and cities wanted them as sources of

highly-skilled bureaucrats and to increase their own reputation.

Occasionally, though, the relations between university students

and their local communities could get hostile, and since

students were treated as clergy, it meant that they could not be

tried by local courts for crimes, only the much more lenient

ecclesiastical courts.

While very few medieval men (and no women) could be part of

a university, the institution did develop and grow throughout

the Middle Ages, and became home to some of the periods

greatest thinkers. The university has since become the

standard of higher education not just in Europe, but throughout

the world.

2. MUSLIM INCURSION AND MEDIEVAL EUROPE :

In less than 100 years, Muslim warriors conquered lands for

Islam from Persia to Spain. Muslims then pushed further into

Europe. Their incursion into Western Europe was stopped in

France. Their invasion from the east was finally halted at the

gates of Vienna.

Beginning :

The prophet Mohammed was born around 570AD in Mecca. In

610 AD a divine experience changed his life and the Muslim

religion was born. Mohammed and his followers gathered force

and increased in numbers, occupying Mecca and Medina

followed by others cities and progressing in both east and

west. In the west, it was slowly eating onto the Byzantine

Empire. In the east, it moved towards India and South East

Asia. In the process, the Muslims occupied in 637 the Holy City

of Jerusalem, damaging the Byzantine Church of The Holy

Sepulcher. This church was said to have been erected on the

very spot where Jesus was crucified. This was a major blow to

the Christians, both eastern and western.

The Invasion of Europe by the Muslims

Muslims gradually captures and Carthage from the Byzantines

Egypt and progressed towards the north-west end of Ifriqiya

i.e. what later became Africa. The capture of Morocco in 669

AD was a major milestone. In 711-715 Muslims captured Spain

by beating the Visigoths rulers and started a 400 year long

rule. Cordova (Qurtuba) becomes the capital of Muslim

holdings in Andalusia (Spain). After capturing Spain, the

Muslims progressed towards Gaul or modern day France.

Before they could occupy much, they were thoroughly beaten

by Charlemagne’s grandfather, Frankish King Charles Martel

(also the father of the first Carolingian King) in the Battle of

Tours in 733 AD. This is a very significant battle since it is said

to have stopped the Muslim occupancy of the Western Europe.

Thus most of Europe was saved from Muslim rule and to this

day remain Christian.

Aftermath

Nevertheless, the expansion of Islam was astounding. In just

100 years since Muhammad first claimed prophethood, Islam

had by force of arms, conquered all of Arabia and then

expanded out and conquered as far west as Spain and as far

east as Afghanistan. The Islamic Caliphate had become the

largest empire the world had yet known, controlling some of

the most important centers of civilization. Of the 5 Christian

Patriarchates (the 5 great urban centers of Christianity in the

6th-7th centuries AD), 3 of them now fell under Islamic rule

(Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch), with only Rome and

Constantinople still under Christian rule. From this point on,

much of Mediterranean history would be characterised by the

struggles between the Christian and Islamic faiths, the

Christians holding the north side of the Mediterranean and the

Muslims the south side. The battlegrounds were to

be Spain, Jerusalem, Constantinople, and the islands caught in

the middle.

Influence on Art and Architecture :

Note 1 : General History

Page 8 of 8

Islamic art took from the civilizations surrounding it and also

impacted them. The Chinese were influenced in their vases

and carpets. Medieval Europe were influenced in their arts and

showed it from their adoption of arches to their illuminations of

Latin and Hebrew manuscripts. For instance, Gothic

architecture was influenced by Islamic architecture. Specifically

Islamic architecture influenced gothic architecture with the

architectural feature, the pointed arch. The pointed arch was

introduced to Europe after the Norman conquest of

Islamic Sicily in 1090, the Crusades which began in 1096,

and the Islamic presence in Spain, which all brought about

knowledge of this significant structural device. It is probable

also that decorative carved stone screens and window

openings filled with pierced stone also influenced Gothic

tracery. In Spain, in particular, individual decorative motifs

occur which are common to both Islamic and Christian

architectural mouldings and sculpture. Of course the epitome

of Islamic art can be seen in the greatest Islamic masterpieces

such as the grand mosques of Cordova in Spain, the Taj Mahal

in India, and the Blue mosque in Turkey. The works of these

Muslim artists have become prototypes and models on which

other artists and craftsmen patterned their own works, or from

which they derived the inspiration for related work. Even in the

pre-Romanesque period architecture (Charlemagne’s palatine

chapel at Aachen, Germany, 9th century) influence of the Great

Mosque of Cordova is evident. The evidence is stronger in the

Romanesque period arches and surface decoration of

churches. Even though the pointed arch in Gothic style is

commonly agreed upon to be a knowledge derived from the

Muslims, the European regions under Muslim rule in the pre-

Gothic area show occurrences of pointed arch as in crossing of

the duomo of Pisa. In the 17th century, renowned architect

Christopher Wren went as far as coining a term, “Saracen

Style” to denote the major contributor of Gothic Style.