False Advertising, Suggestive Persuasion, and Automobile Safety

Future Advertising Strategies - Theories, Persuasion Principles, and Value

-

Upload

cory-morrison -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Future Advertising Strategies - Theories, Persuasion Principles, and Value

Future Advertising Strategies

Theories, Persuasion Principles, and Value

Cory Morrison

December 2009

Contents:

SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION p. 1 SECTION TWO: THEORIES p. 2 SECTION THREE: PRINCIPLES p. 5 SECTION FOUR: VALUE p. 7 SECTION FIVE: KEY QUESTIONS p. 9 SECTION SIX: CONCLUSION p. 10 Bibliography p. 11

1

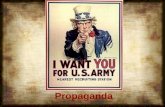

SECTION ONE: Introduction Chiefs are the decision makers, the path creators, the connection forgers, and the leaders of the Indians. Most importantly, however, the chiefs are Indians’ influencers. Without chiefs there would be no direction. From an advertising standpoint, direction refers to forwarding a product’s popularity and sales. Chiefs are the influencers who do this. People are innately Indians. They follow before they lead and trust those similar to them. People also follow groups, as evident by Germany’s propaganda success in the 1930s and the United States’ counter-culture in the 1960s and 1970s. Future advertising strategies should aim to make as many chiefs for a brand as possible. These chiefs will promote products through the “groundswell,” a term authors Charlene Li and Josh Bernoff of the book Groundswell use to label the online stage for person-to-person interactivity. The groundswell includes blogs, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, designated online communities, and many other Web-based collaborative, user-generated content sharing tools. Advertisers must now ask four crucial questions:

1. What does it take to make a chief out of an Indian? 2. Do consumers have to be Indians before they can be chiefs? 3. Who do people trust more- information disseminators or information receivers? 4. At what point does something or someone become trustworthy?

2

SECTION TWO: Theories Online Communities Theory

Online communities are groups of people who communicate primarily online. According to Pareto’s Law, 20 percent of the people in online communities do 80 percent of the posting. Peter Kollock used this theory to explain two reasons people do this:

1. A sense of belonging. 2. An opportunity for people to speak and see how their input is part of a system’s

output. a. Anticipated reciprocity- the notion that people will contribute if they

expect to get something in return (Anderson, 26-27).

Social Networks Theory

The Social Network Theory describes the relationship between members of social systems. Mark Granovetter found that boundaries of these social systems can be weak or strong, and thus determine how effective information dissemination can be. Strong boundaries limit interaction while weak boundaries encourage it. For example, sites like Facebook and MySpace have weak boundaries, allowing users to share as much information as they’re comfortable with (Anderson, 23). What is the groundswell?

The groundswell is a multistage platform where people use each other as sources to fulfill their needs rather than paid media personnel. Indulging in social networks and user-generated content sites gives a brand a personality page that others can follow and partake in. A chart showing the activity among certain age groups in the groundswell is shown below (Schafer, 16):

3

It is important to understand that people are innately people pleasers. Given the opportunity to provide input, help others, and communicate about something that matters to them, users generate “psychic income” (Bernoff, 170-1). Psychic income is self-rewarding satisfaction, and a huge factor in why people contribute content online.

Reptilian theory

Market researcher Clotaire Rapaille uses the Reptilian Theory to put consumers in the mindset they are in after waking up. This delves into their subconscious to rediscover memories associated with certain words. The Reptilian Theory also explains that “reptilian hotspots” are what trigger behavior. Pushing these hotspots exposes information that people would otherwise be unable to vocalize (Goodman).

Adoption Theory

The Adoption Theory explains how quickly and intricately a new technology or idea is adopted into society. Moreover, it states that in any population, there is always a certain group quick to do this. These people are called “innovators,” and are the chiefs who influence the groups following them as the adoption (diffusion) process progresses.

Powerful Effects Theory

The Powerful Effects Theory states that the effects of media are most powerful when it reaches people in multiple ways (Anderson, 43). For instance, one is probably likelier to trust a media story if he or she sees it on multiple platforms.

Power Law Effect

The Power Law Effect explains how people follow in others’ footsteps. Google is one example. The top search results on Google often hold that status because people see that they are at the top and infer that these results get the most clicks (Anderson, 43).

Other Theories

Agenda Setting

The Agenda Setting Theory states that the media tells us not what to think, but what to think about. Therefore, the media sets the public agenda and serves as gatekeepers of thought. This theory may seem invalid now because people have more television networks, the Web, etc. to confirm information and base opinions on. On that note, though, lies the validity in the notion that people have so much clutter coming at them that advertisers must provide value (see: value) in their messages. Products, services, policies, reviews, ratings, polls, etc. bombard consumers daily. How do consumers filter these things to prevent them from doing what they want to do? Consumers use the knowledge presented to them to assess what has value, what interests them, and what they can trust as reputable and useful.

4

Spiral of Silence Theory The Spiral of Silence Theory states that people who feel they are in the minority will not voice their opinions for fear of isolation. Cognitive Dissonance Theory The Cognitive Dissonance Theory states that people find inconsistencies (dissonance) uncomfortable so they try to reduce their exposure to them.

5

SECTION THREE: Principles Commitment/Consistency The commitment, or consistency, principle states that people often act and think Routinely (Cialdini, 52). Reasons for this may relate to the Spiral of Silence Theory or the Cognitive Dissonance Theory. A key thing to remember about the commitment principle is that once someone has acted a certain way multiple times and feels comfortable and successful doing so, it becomes routine. The commitment principle relates to the Reptilian Theory and the Powerful Effects Theory. The Reptilian Theory can be used to interrupt, redefine, or even define the day-to-day behavioral patterns consumers consistently follow but cannot verbalize. The way to do this is to examine an individual from all angles. Market research too often focuses on groups of people and therefore makes generalities. Consider a person who consistently buys Tide and one day randomly decides to buy Cheer. Using the Reptilian Theory, market research can help explain why this change in behavior occurred. To illustrate the use of the Reptilian Theory, consider the example below of how Clotaire Rapaille conducted research for Lexus:

The small group of individuals who were a part of Rapaille’s research process was told to lay down in the dark and close their eyes. After giving them time to relax, Rapaille woke them from their relaxed state to simulate an experience of having just woken up from a deep sleep. He then asked them questions. He found that people were more able to vocalize their attitudes toward the word “luxury,” a word associated with Lexus’ advertising, because of their clearer state of mind. Rapaille had successfully tapped into the subconscious of how people associate the word luxury with their lives (Goodman).

While it was mentioned above that market research should focus on individuals, generalizations can be made in this case, as the research performed was more substantive than traditional research. While there will never be a concrete way to explain human behavior and attitudes, treating consumers as individuals during research certainly helps and can be applied to larger groups. This is because while everyone is different, there are certain human instincts, behaviors, and thought processes that connect us. It is simply a matter of uncovering how one person does that to intelligently explain how others do as well. The commitment principle also relates to the Powerful Effects Theory because if people are hearing the same or a similar message across multiple platforms and media types, their response to and trust in that message’s validity becomes more substantial. Therefore, these people will likely react to similar messages in the same way, and thus commit to consistent behaviors and attitudes whether they realize it or not. This notion of people not realizing things that have become routine is very similar to how advertising works on many people. The general stigma toward advertising is that it is annoying and manipulative. Therefore, people like to believe they are immune to it. This is naïve for two reasons. The first reason is because no matter how much people say they

6

dislike advertising, when the right ad comes around it reaches them. The second reason is that advertising can often be a behind-the-scenes influencer. It may not yield immediate consumer action, but often does later. Furthermore, consider someone who thinks a particular brand’s advertising is annoying. If that brand advertises significantly more than its competitors, the person is likely to remember that advertising if the time comes for him or her to buy something from its industry. Authority Principle The authority principle states that people assume seemingly credible people are always more credible than themselves. In other words, people obey those in power because of a predetermined perception that those people are more knowledgeable than they are (Cialdini, 181). A simple example of this is an employee not questioning her boss’ instruction, despite being confident that it is wrong. What the employee has done here is undermined herself because of the aforementioned perception that her boss is more knowledgeable than her, and thus she “must be overlooking something.” The authority principle is relevant to the Adoption Theory because the Adoption Theory’s innovators are becoming the new form of authority. People have already begun to trust their fellow man more so than advertisers or other paid media personnel. This is because product and brand testimonials, reviews, ratings, and endorsements in the groundswell are real and posted by people with nothing to lose. The groundswell is a hot spot for voicing opinions, especially since the Spiral of Silence Theory is void within it because there can be no direct tie to the people who contribute content. Reciprocity Principle The principle of reciprocity states that people who receive something feel obligated to give something in return (Cialdini, 31). It is often shown in marketing. For example, the server of a free sample in a grocery store is serving that sample for a reason- to get the customer to buy more of it. In this example, the employee is the giver and is anticipating reciprocity. Another example comes from the groundswell. Someone may write a blog post or post a YouTube video in hopes that someone will comment on it. Furthermore, this comment may feature a link to the commenter’s website, an instance of the commenter using the reciprocity that someone else has established. The reciprocity principle relates to two of the aforementioned theories. In the Online Communities Theory, the 20 percent of posters who contribute 80 percent of the content are the innovators from the Adoption Theory. Therefore, empowering the creators and critics in the groundswell (see: groundswell users chart) to be chiefs is highly beneficial, as they will likely be the most influential changers of a product or brand’s trajectory. Because of the reciprocity principle, readers of chiefs’ groundswell postings feel obligated to react to it. This generates more conversation and groundswell presence around a product or brand.

7

SECTION FOUR: Value Advertising starts with two things: relevance and value. If an advertising message lacks either of these, a consumer will dismiss it. It is difficult to determine which of the two comes first. Does something have to be relevant to have value, or can relevance simply be tied to timeliness of current events or societal trends and norms? Defining value is just as inconclusive. Brands create products that serve individuals and groups, so therefore value cannot be limited to a specific number of people. Value relates to Rapaille’s Reptilian Theory, as it is often what people cannot explain or even notice. However, the power of value is great, as it is the driving force behind consumerism. People do not waste their money on things that serve no benefit to them. Chiefs are good for advertising because they often share their experience with a product and how it has changed some part of their life. This experience may not be what the advertiser was advertising, which is why it is important to understand the necessity of individual attention on consumers. No product experience is the same. However, chiefs have an important role in sharing how a product or brand enhanced their life. They enjoy doing this because the value a product gives them empowers them to become a chief. Another principle by Cialdini is the liking principle, which explains that people identify with others similar to them. Keeping this principle in mind, consider the following example:

The product is the Pet Hair Removal device by Swiffer. The chief, a 40-year-old woman, uses the groundswell to write a blog post about the product. This blog post features a review and personalized story about how it helped her clean her sofas before relatives flew in for the holidays. Seeing this, an Indian, or spectator (see: groundswell users chart), thinks to herself that she needs to prepare her car for a potential buyer, and therefore indentifies with the chief. While the user experience may be different because both the chief and Indian are cleaning different surfaces for different reasons, the chief played an important role in shaping an additional sale.

Intangible Value Rory Sutherland presented at TED in July 2009 on the power of intangible value, a kind of value that “in many ways is a very, very fine substitute for using up labor or limited resources in the creation of things” (Sutherland). Intangible value can also be called badge value, perceived value, subjective value, messaging value, or symbolic value (Ibid). Sutherland argues that all value is relative and subjective (Ibid). Individuals determine what is valuable to them, and thus another person’s interpretation of value may differ. However, there are examples of things intangibly valuable to all types of people. Two examples of democratic intangible value are Denim and Coca-Cola. Sutherland labels such products as democratic products because they are universally accepted and

8

have no greater value to person A than person B. This creates a more egalitarian society (Ibid). Another principle by Cialdini, the social proof principle, refers to the notion that people behave according to how the person before them behaved, much like the Power Law Effect. The social proof principle also bears resemblance to the bandwagon phenomenon, where one person joins the bandwagon because everyone else has. Using social proof and the thought of an egalitarian society, consider the following point:

Intangible value can come from things that are scarce or ubiquitous. Ubiquitous things create social norms or trends, and to align one’s self with such trends creates a perception that one is adapting value because others are as well (Ibid).

Sutherland says the goal of advertising “is to help people appreciate what is unfamiliar but also to gain a greater appreciation and place a far higher value on those things which are already existing” (Ibid). Social media does this by using third-party enjoyment out of the little things in life and giving them intangible value (Ibid). A groundswell “creator” who combines two kinds of empowerment by using the groundswell’s intangible value to promote a product or brand’s intangible value becomes a driving force for influencing others. This creator has become a chief.

9

SECTION FIVE: Key Questions What does it take to make a chief out of an Indian? As previously mentioned, the Reptilian Theory can be used to engage an Indian consumer on a level he or she cannot vocalize. Doing so creates a new way for him or her to look at a brand or product. If done correctly, this can empower the Indian to become a chief and therefore influence others. Do consumers have to be Indians before they can be chiefs? Consumers do not have to be Indians before they can be chiefs. However, once a chief is created, that person will likely remain a chief for the brand’s next product. Who do people trust more- information disseminators or information receivers? Typically speaking, Web 2.0 and the impending Web 3.0 are part of an era where Web browsers trust information receivers more than paid media personnel. This is because of the unbiased, truthful accounts of products and brands that receivers provide, which are higly concentrated in the groundswell. At what point does something or someone become trustworthy? Put quite simply, a product is trustworthy when it has intangible value. This also generates consumer trust in the brand that created the product.

10

SECTION SIX: Conclusion Empowering consumers to become chiefs for a brand is a crucial element to advertising as the digital and hyperconnectivity age progress. Consumers are essentially becoming advertisers, and even the molders of brands. Many advertisers do not realize the value in chiefs, and will subsequently struggle to keep up with the imminent and drastic changes the advertising industry continues to see. More chiefs equals:

o Less money and work to advertise. o Increased brand loyalty, as chiefs are brand advocates. o Real, unbiased testimonials to a product’s intangible value. o An increase in social proof as Indians follow in chiefs’ footsteps. o More brand “shareholders.” o Agenda Setting by a more trustworthy source- the common man. o A greater push for the Adoption Theory’s influential power. o More brand presence in the groundswell. o A conversion of enthusiasts into evangelists.

11

Bibliography

Anderson, J. Q. (2009, July). An introduction to interactive media theory. Retrieved from http://facstaff.elon.edu/andersj/imedia/COM530THEORYbook.pdf.

Anderson’s account of interactive media theory delves into why people respond to information the way they do. Many theories that operate behind the scenes of interactivity are featured in this book, as well as an interactive timeline starting in 1969.

Cited as ‘Anderson’ Bernoff, J & Li, C. (2008). Groundswell. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Groundswell is the term Bernoff and Li use to describe the conglomerate of social media and web communication. In this book, they offer strategies along with logic of how a marketer can interpret the groundswell, enter it, leverage it, and succeed in it. Cited as ‘Bernoff ’

Cialdini, R. B. (2009, 2001). Influence: Science and practice. Pearson Education, Inc.

Cialdini writes about influential strategies for information conveyance as well as the theories behind them, He includes principles such as social proof and the reciprocity rule, and how people manipulate others to get what they want.

Cited as ‘Cialdini’ Goodman, B., & Rushkoff, D. (Writers) & Goodman, B. & Dretzin, R. (Directors) (2003, November 9). The persuaders. PBS Frontline. WGBH Boston. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/persuaders/view/.

The Persuaders is a documentary on advertising. Market researcher Clotaire Rapaille talks about his self-developed Reptilian Theory as it relates to consumer behavior.

Cited as ‘Goodman’ Schafer, I. The future of marketing, advertising, and branded entertainment. Retrieved

from: http://www.slideshare.net/ischafer/the-future-of-marketing-advertising-and-branded-entertainment. Schafer’s presentation focuses on how traditional communication theory is applicable today. He talks specifically about the Diffusion of Innovations Theory. Cited as ‘Schafer’

Sutherland, R. (2009). Life lessons from an ad man. Video presentation. Retrieved from: http://www.ted.com/talks/rory_sutherland_life_lessons_from_an_ad_man.html.

Rory Sutherland presents on intangible value, a type of value that is typically overlooked by advertisers. His presentation provides a more comprehensive look at what value means. Cited as ‘Sutherland’