Frontiers in the Treatment of Trauma · 2018-08-06 · an you just give us a quick rundown? Let's...

Transcript of Frontiers in the Treatment of Trauma · 2018-08-06 · an you just give us a quick rundown? Let's...

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 1

Frontiers in the

Treatment of Trauma

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma

the Main Session with

Pat Ogden, PhD and Ruth Buczynski, PhD

National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 2

Frontiers in the Treatment of Trauma: Pat Ogden, PhD

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma

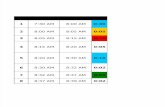

Table of Contents

(click to go to a page)

What Makes a Sensorimotor Approach to Trauma Unique .................................... 3

Working with Patients in “The Now” ...................................................................... 4

Key Skills: Tracking and Body Reading .................................................................... 5

Contact Statements ............................................................................................... 10

Experiments to Engage Curiosity ............................................................................ 11

Using Touch: A Potent Intervention ........................................................................ 13

How Body Awareness Helps to Track Potential Transference ................................. 14

Therapy Walk-Throughs: How Therapists Should Begin ......................................... 18

How to Reinstate Lost Resources ........................................................................... 21

How to Develop Interoceptive Awareness .............................................................. 23

How to Work with Procedural Memory .................................................................. 24

About the Speakers ................................................................................................ 26

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 3

Dr. Buczynski: Hello everyone and welcome back. I am Dr. Ruth Buczynski, a licensed psychologist and

President of the National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine. We’re so glad that

you’re watching.

Our guest is Dr. Pat Ogden. You know her because we’ve had her on many times, but in case this is your first

time watching us, Pat is a pioneer in somatic psychology.

She is the founder and the director of the Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute – that is an international

institute; it is housed in Boulder, Colorado and now a training program that is really worldwide.

She’s the author of the groundbreaking book, Trauma in the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to

Psychotherapy.

Pat, welcome, and it’s good to see you again!

Dr. Ogden: Thank you – good to see you, too!

What Makes a Sensorimotor Approach to Trauma Unique

Dr. Buczynski: We want to dig deep into the whole idea of sensorimotor psychotherapy, but first we should

give a recap to people who are new – who haven't heard us talking about this before.

Can you just give us a quick rundown? Let's start with a rundown on what makes your approach, or your way

of thinking about trauma, unique.

Dr. Ogden: Most of the therapists that we train have been trained in

the psychodynamic approach, which is talking about the trauma, trying

to resolve it through understanding it.

But talking about can stimulate the implicit and the physiological

recollections of the trauma, and a person can detach as they are talking about it.

Frontiers in the Treatment of Trauma: Pat Ogden, PhD

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma

“Trauma stimulates the

subcortical brain, the

instinctive responses of

fight, flight, freeze and a

feigned-death response.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 4

We work with and directly address the body, where trauma first impacts.

Trauma stimulates the subcortical brain, the instinctive responses of fight,

flight, freeze and a feigned-death response.

We see the effects of trauma on the body and the nervous system – a

nervous system that is hyperaroused or hypoaroused; we see tension that

reflects freezing or truncated active defensive responses that were

simulated in the face of trauma.

We really want to work with how the body has taken on the trauma and how it hasn't resolved it physically

and physiologically.

Dr. Buczynski: What would you say that we’re missing if we’re not

thinking about the body when we’re treating people who have

experienced trauma?

Dr. Ogden: We miss concrete ways to work with some of the

symptoms of trauma at the level that is driving those symptoms.

We all know that trauma dysregulates the nervous system; when trauma

happens, the physiological arousal is stimulated to arouse the body for

defense and protection, and often that arousal doesn't come back down.

People often try to work on that with insight – helping a person realize

that he/she is safe now – that the trauma is over. But if your physiology is still hyperaroused, your body is

constantly telling you that you are not safe.

What we want to do is work directly with somatic resources to help the body itself calm down – and then the

client will get a message from the body that, "I’m okay now. It's safe now."

Working with Patients in “The Now”

Dr. Buczynski: One of the key aspects of sensorimotor psychotherapy is to work in “the now.” Why is the

present so important?

“We want to work

with how the body has

taken on the trauma

and how it hasn't

resolved it physically

and physiologically.”

“We want to work

directly with somatic

resources to help the

body itself calm down.”

“When trauma happens, the

physiological arousal is

stimulated to arouse the

body, and often that arousal

doesn't come back down.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 5

Dr. Ogden: That's a great question. Because we’re never working with the actual events of the past, we’re

working with how those events are impacting the person in the present moment.

Instead of just talking about it, as a person starts to recount their

trauma, we will see the effects – the leftovers from whatever

happened to them in the body, in the prosody – their affect in the

now, in the present moment.

Really, the present moment is all we have to try to reorganize those responses.

Dr. Buczynski: Not everyone who’s watching is a therapist – we have practitioners that really span many,

many professions – so I just want you to define the word prosody. Stephen Porges also uses the word

prosody – what do we mean by that?

Dr. Ogden: Prosody is just how we use our voice. Do we use our voice like this – as if we're always asking a

question? Or do we use our voice like this – as if we're kind of depressed?

That comes across through our prosody.

Or is our voice always excited and animated, maybe reflecting a high

arousal or just excitement?

So, prosody just refers to the pace, the tone, the syntax – how we speak.

Dr. Buczynski: Prosody is a cluster of factors – not just one. But it doesn't include the content of what we’re

saying.

Dr. Ogden: That's exactly right. It's more how we say it than what we say.

Key Skills: Tracking and Body Reading

Dr. Buczynski: Now, let’s move to other key skills. Two of the key skills in working with sensorimotor

psychotherapy are tracking and body reading, and I would like to go through them, but I’m wondering if we

can pick a case that you’ve had to show an example of tracking and body reading.

You can first describe what you mean by them and then talk about the case, or vice versa – either way.

“Prosody is how we use

our voice; the pace, the

tone, the syntax – how

we speak.”

“The present moment is all

we have to try to reorganize

those responses.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 6

Dr. Ogden: Sure. Body reading, very simply, is looking at the structure and the movement of the body that is

characteristic for the person.

One of my favorite things still to do with some of my friends and

colleagues is to go to a mall and watch bodies – watch how everybody

moves so differently.

In sensorimotor psychotherapy, with body reading, we can see the record of the history in a person's

movement and gait – the way they hold their head and shoulders. There are typical gestures that they use.

So that is body reading.

Tracking is simply tracking the moment-by-moment changes in the body through the session. In fact Beatrice

Beebe has broken this down with babies – this microsecond tracking of a baby's response to the mother. She

has all that on film, which is just exquisite to see.

We want to train ourselves to do that in therapy because we’re

looking at how the body reflects and sustains whatever difficulties

the client is having.

Dr. Buczynski: Are you, in therapy, doing it on the microsecond level?

Dr. Ogden: You’re capturing those fleeting little bodily expressions that can go by like that!

Yes – I'm thinking of a patient now who is a very well-known author, and he had a crisis – his parents passed

away and he got a divorce all within a year; it was in a very, very quick succession.

He had a posture that was kind of pulled in and down – like this – and as he talked about his history and his

losses, you could see just a slight exaggeration of that pattern.

We know that that is the presence of the past in the now – it is his

history that is re-stimulated by his current events. But much of his

old history had to do with very implicit memories that he couldn't

possibly remember because it happened when he was a baby.

His mother had had a breakdown after he was born; she probably had postpartum depression but didn't

know it because he was born in the early forties or maybe late thirties.

“In therapy we’re looking at

how the body reflects and

sustains whatever difficulties

the client is having.”

“With body reading, we

can see the record of

the history in a person's

movement and gait.”

“He had a posture that was

pulled in and down and as he

talked about his history, you

could see just a slight

exaggeration of that pattern.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 7

He was abandoned by his mother in the first month or two of his life,

and he didn't remember any of that consciously, but he knew it – his

body knew it and his body remembered.

Dr. Buczynski: Give us a little picture of how you worked with him.

Dr. Ogden: He was stuck in the pattern of despair, constant crying – just focused on the loss, the traumatic

loss of his childhood and also the traumatic loss of the past year.

It was as if he had stepped into a path that he couldn't get out of. It was just constant weeping. He said he

just couldn't work anymore.

He was just going through his days weeping and feeling the loss. As we worked together, the more he talked

about it, the more he got into his pattern.

Dr. Buczynski: The hunched-over pattern.

Dr. Ogden: Yes – the hunch and the loss of postural integrity – his spine did not support him.

You will see this very clearly in Ed Tronick's videos of babies when he has the mother stop responding to the

baby and just have a still face – no response. The babies will just start to collapse like that.

Let’s call this person Bill. He had lost his core, and what is so important about that in terms of the body, is

that our spine is the core of our body. If we have a flexible but sturdy and erect spine, it provides the axis

around which all movement can happen.

We see this in babies – how they set up so straight – they have

that postural integrity that people like Bill lose over time.

We had to work with his strengthening the core of his body so

that he could have a home that he felt was solid in his own body, rather than just this reflection of despair

that is very physical – it’s not just psychological.

So we worked in a couple of ways. First, we worked with what I call pushing actions – if you push from your

back, your spine will start to lengthen.

We worked with pushing up from the top of his head to the sky and down with his pelvic floor when he was

sitting, or down with his feet when he was standing.

“If we have a flexible but

sturdy and erect spine, it

provides the axis around which

all movement can happen.”

“He didn't remember any of

that consciously, but he

knew it – his body knew it

and his body remembered.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 8

That push is a very basic movement. We have to push to get out of the

womb – we push with the top of our head and we push with our feet. That

very basic movement he had lost and it showed up in many ways.

It showed up in his lack of a solid sense of self; it showed up with his

pattern – he repeatedly went to that collapse. It showed up in that he felt

no control over his life and he couldn't keep things out – everything just got in.

As we worked with that, he immediately started to get out of that pattern. But of course he needed to

practice this over and over and over because it was a basic action that he had lost when he was very young.

Dr. Buczynski: In what sense did he practice that? Did you set up experiments or real life experiences for him

to practice that? How did that go?

Dr. Ogden: Yes – both. In the therapy, it was an experiment to find out what would happen if he did push up

with the top of his head. I put a pillow there with some pressure and

then my hand so he had something to push against.

That is when he started to feel stronger – he could access another

part of himself rather than only the despair.

But then he also had to practice that on his own because when we’re

working with changing the procedural learning of the body, it takes

repeated iterations of the movement in order to develop a new pattern.

Dr. Buczynski: The other part, besides tracking, was body reading. When you worked with Bill, did the body

reading mean, “When a person does this, it means that?”

Or is body reading more about giving a voice to your shoulders that go into

that posture and see what it means?

Dr. Ogden: I would always want the meaning to come from the clients

rather than my saying, "When your body is like this it means this."

This all has to do with low self-esteem and the loss of a central sense of self, and every client has their own

particular belief structure that goes with their postures, so I'd like a person to go into the pattern and – as

you said – find out what words come, "What is your body saying?"

“When we’re working with

changing the procedural

learning of the body, it

takes repeated iterations of

the movement in order to

develop a new pattern.”

“I'd like a person to

go into the pattern

and find out what

words come, ‘What is

your body saying?’”

“We worked with what

I call pushing actions –

if you push from your

back, your spine will

start to lengthen.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 9

In terms of body reading, I am trained in the Rolf Method, which really looks at the alignment of the body to

see if the body is at peace with gravity.

If the body is in alignment with itself, gravity can uplift the body. It

doesn't just hold it to the earth but it lifts it up.

But many people have patterns where their heads are forward, their

shoulders are tight, or their shoulders are back, their spine is not

aligned, their knees are locked.

When I’m reading a body, I’m looking at: Is the body in alignment with gravity, or where is the body not in

alignment with gravity? The patterns of a lack of alignment with gravity are often formed in the face of our

childhood attachment relationships.

Dr. Buczynski: Now this concept of being in alignment with gravity is

something we haven’t talked about on our webinars with you – I want

to make sure that everyone understands what you mean. Can you just

summarize that for us?

Dr. Ogden: I’ll talk about it the way Ida Rolf talked about it – Ida Rolf

was the creator of Rolfing, which was a deep form of hands-on body work where you work with the fascial

layers so the body can find its alignment.

As she described it, if a person is standing still, there is a plumb line that goes through the ear, the shoulder,

the hip joint, the knee and the ankle.

If a person's body is aligned, that plumb line is straight. But very often it’s not. Very often the head is forward,

the shoulders are back, the pelvis is not in alignment and neither are the knees and the legs – the body just

doesn’t line up that way.

There are all these angles, and unless there was an injury that is organic or physical, we look at that through

psychological patterns.

I am thinking of a man who had a different pattern – his shoulders were up

and forward like this. It wasn't a collapse, and in working with him, what he

got in touch with was that he couldn't be weak; he had to be strong. He

“If the body is in

alignment with itself,

gravity can uplift the body.

It doesn't just hold it to

the earth but it lifts it up.”

“The patterns of a lack of

alignment with gravity are

often formed in the face

of our childhood

attachment relationships.”

“If a person's body is

aligned, that plumb

line is straight. But

very often it’s not.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 10

always had to be strong, and that showed in his body as a reflection of the message he got from his father.

Contact Statements

Dr. Buczynski: In another part of your work – you use what you call “contact statements." Can we talk about

what contact statements are in your way of looking at them and how you use them? Perhaps you can talk

about how they relate to this most recent person you talked about,

or with Bill, the man you talked about earlier.

Dr. Ogden: Sure. I learned about contact statements from Ron Kurtz,

who was my primary mentor in the seventies. What is interesting

about contact statements is that everybody makes them.

A contact statement demonstrates that you understand what a client is going through. So you might say,

"Oh, childhood must have been so hard for you." That is a contact statement.

The difference in this work (from other therapy) gets back to working with the now. Therapists have to learn

to make contact statements with present-moment experience that incorporate the body's response.

For example, with Bill, I might say something like, "As you talk about all these losses, your head is starting to

pull in more."

That is a contact statement with present-moment physical experience, which therapists are often hesitant to

make because it’s not a contact statement we would make in our daily lives.

We make contact statements with our friends all the time. "Oh, yes, you’re

having a great day." That's a contact statement – it shows that you

understand their experience.

But when you start to bring in the body, it feels off to people. That is where tracking comes in – you have to

track the client's response, and if they have an aversive reaction, then you have to make contact with that:

"Oh, something disturbed you about that statement. Is that right?"

Dr. Buczynski: And yet, when you’re using a contact statement in reference to the body, it sounds to me like

you’re not making an interpretation as in, "Your shoulders are hunched in and that therefore means."

“Therapists have to learn to

make contact statements

with present-moment

experience that incorporate

the body's response.”

“We make contact

statements with our

friends all the time.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 11

Dr. Ogden: Yes, you're right – I want the client to discover what it means.

Often we’ll even put in a qualifier. We might say, "You know, it looks like your shoulders are hunching up

right now." They can confirm or deny it.

If they’re interested in it, then we can explore it: "If you go into that pattern, what does it tell you? Do images

come up? Do words come up?"

Dr. Buczynski: Would you have them almost exaggerate that pattern so

that they can really get into it?

Dr. Ogden: Exactly, yes. But just a little bit – you don't need much.

You’ve raised the signal just a tiny bit – you have them try it a tiny bit more. The more subtle, almost the

more potent it is for them.

Dr. Buczynski: In your perspective, is it important for the therapist to be open to, "This person's walking and

leaning forward and that can mean any number of things – let's find out what the truth of it is for her/him."

Dr. Ogden: Yes. That's right, and that’s where the body reading and

the tracking interface. If a person is walking and leaning forward, that

is going to show up in some form when they’re sitting down and

talking to you.

So you’re looking at, "Do they lean forward when they’re talking

about their difficulties or their presenting problem? Is that pattern exacerbated?" If it is, it probably has

significant psychological import.

Experiments to Engage Curiosity

Dr. Buczynski: You talk about curiosity and about using experiments as a way to engage curiosity. First of all,

can we talk about what an experiment is, and then can you give us some examples of that?

Dr. Ogden: Sure. It goes along with what we’ve been talking about – how clients discover, inside themselves,

the patterns and the meaning of the patterns.

“If they’re interested in it,

then we can explore it: ‘If

you go into that pattern,

what does it tell you?’”

“‘Do they lean forward

when they’re talking about

their difficulties or their

presenting problem? Is that

pattern exacerbated?’”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 12

An experiment is just prefaced with the words, "Well, let's find out what

happens." As a therapist, you might have your hypothesis of what you think

is going to happen, but you have to be open to any outcomes.

Here are some experiments we’ve already talked. If somebody has an

exaggerates posture – if the head is forward, we might say, "Let's find out what happens if you just

exaggerate that a little bit by just putting your head a tiny bit more forward. What happens inside?"

We’re looking for the present-moment, here-and-now changes in emotions, body sensations, thoughts, and

images – we’re looking for what comes up as a result of the little experiment.

Dr. Buczynski: Can you give us an example of a case? Maybe you can

show us either with the two gentlemen we have already talked about or

with someone new.

Dr. Ogden: With Bill, the person who went like this, one of the first

experiments was, "What happens when you feel that pattern? What

happens if you just take it on a little bit more?"

That was one of the first experiments. But nothing new came from that experiment. He just wept more and

got more sad and hopeless.

So then, another experiment was, "What happens if you shift that pattern – if you do the opposite and you

push up with your head?" Then we noticed there was a pretty dramatic change.

Experiments can be infinite. It could be, "What happens when you think about what happened to you?"

That’s a little experiment. "My body gets tight. I start to feel frightened. I want to pull back."

The results of the experiment that we’re interested in are not about conversation – they’re about that

present-moment, here-and-now response. That’s what we have to work with in order to make the shifts.

Dr. Buczynski: I imagine that that really did engage his curiosity when you had him go into the opposite and

he found that that really made a shift.

Dr. Ogden: Right. Yes.

Dr. Buczynski: Something like that really does get someone's attention.

“An experiment is just

prefaced with the

words, ‘Well, let's find

out what happens.’”

“We’re looking for the

present-moment changes

in emotions, body

sensations, thoughts, and

images as a result of the

little experiment.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 13

Dr. Ogden: Yes, it did, and it doesn't mean – I want to be sure to say – that he overrides this part of him.

In long-term work, finding his alignment and his core strength will give

him what he needs to be able to work with that part of him that’s in

such despair.

It’s not about pushing one part away. We have to help those parts of

him relate to each other and communicate with each other.

Dr. Buczynski: It’s more about being friends with who he is in his body, including the way his voice sounds

and the way he moves and sits and stands.

Dr. Ogden: Exactly, yes.

Using Touch: A Potent Intervention

Dr. Buczynski: So let's talk about touch. Some of us use touch as an approach; others of us are trained not to

ever touch someone – not so true for folks on the medical side, but often true for the mental health people.

You’re talking about the body a lot – what’s your perspective on touch?

Dr. Ogden: It's a very interesting topic. I’ve been working with touch since the early seventies when I taught

yoga and dance in a psychiatric hospital and studied all kinds of massage, structural body work, and

movement.

I’m very comfortable with touch – but I don't use it very often. Even with Bill, when he was working with that

push, I used a pillow for him to push upward – I didn't use my hand.

Touch is a very, very potent intervention, especially when it’s combined with psychotherapy. Usually when

we’re touching people, we touch people we’re close to – our friends, our family, our lovers, our children.

We don't touch people that we’re not in some way having a

social relationship with.

Sometimes it’s difficult for therapists to realize that if they’re

using touch with their clients, it has a different meaning – you’re not using it for the same purpose that you

“We have to help those

parts of him relate to each

other and communicate

with each other.”

“Touch is a very potent

intervention, especially when it’s

combined with psychotherapy.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 14

use touch in your daily life. It’s also difficult for clients to separate that out as well.

Dr. Buczynski: Is this getting into thinking about transference and counter-transference?

Dr. Ogden: You bet! I was on an ethics board for a body-centered

psychotherapy school – not my own.

This was a very long time ago, thirty-five years or so ago, and all the

complaints that came in had to do with physical touch.

This was where clients unconsciously put the therapist in the role of the perpetrator although the therapist

had nothing but good intentions.

In the treatment of trauma, traumatic transference can cause a client, when they’re touched, to interpret

that touch as a violation, even though the toucher has no intention of violating.

If clients are dissociative, one part of them can go, "Oh, I'm being

abused again" – and that can cause lawsuits.

Unless you really understand traumatic transference and

common transference, I would suggest being very, very cautious

about using touch with traumatized patients.

This is what I tell all our students: if you are using touch, be very clear in your mind about why you’re using it.

Are you using touch to support a different action – like with Bill?

Is it to keep somebody grounded because they’re starting to go out of their window of tolerance? If you’re

working with preverbal trauma, is it to help them feel that you’re actually there and they’re not alone?

It’s important to be very, very specific about the use of touch because the pattern is just to fall into touch as a

way to comfort somebody and make them feel better.

How Body Awareness Helps to Track Potential Transference

Dr. Buczynski: Talk to us about how body awareness helps the practitioner keep track of potential

transferences.

“Unless you understand

traumatic transference and

common transference, I would

suggest being very, very

cautious about using touch

with traumatized patients.”

“Traumatic transference can

cause a client, when they’re

touched, to interpret that

touch as a violation.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 15

Dr. Ogden: If you know your own body and you keep some of your mindful awareness with that, you will

start to become aware of when you're going into a pattern. Not always – but often.

But I want to preface that by saying that transference and counter-transference and getting into those

patterns of "stuckness" that we all get into are not at all

negative in therapy.

I've learned this from Philip Bromberg: when we get into

those collisions of transference and counter-transference, we

can get into these therapeutic enactments that often provide

very rich terrain for transformation – and without that, we might not be able to have the transformation.

I remember one client that I worked with who had been severely abused. This was a consultation session,

and she wanted to work with her anger.

Whenever she tried to work with her anger, she would self-harm; she would cut herself and even tried

suicide. I was working with her and it was going very well.

There were about ten people on her treatment team watching from a one-way mirror, which implicitly

stimulated my performance anxiety…

In my family and as I grew up, doing well was really prized – you were supposed to get all A’s on your report

card, and I have this pattern of mobilization when I feel that pressure.

I wasn't real aware of it, but I was pushing her to go further even though she'd already made great gains.

I was pushing her to go further, and one of her big issues was not being able to set boundaries; she could

never protect herself from the abuse.

What was so great about this session was that in my pushing, she

finally said, "I need to stop" – and she set a boundary with me.

We'd gotten into this "stuckness" together, which enabled her to

come forward with this verbal response when we’d been working with being able to say no physically.

She described how wonderful it was to be able to say no to me in the session – that would never have

happened if I hadn't gotten into my childhood history and if she hadn't first gone into her "stuckness" about

“We'd gotten into this

‘stuckness’ together, which

enabled her to come forward

with this verbal response.”

“If you know your own body

collisions of transference and

counter-transference provide very

rich terrain for transformation.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 16

not being able to say no.

It turned out to be a more potent transformation for her than would have happened if we hadn't gotten into

that.

Dr. Buczynski: When you were involved in that moment, were you aware of the connection to you?

Dr. Ogden: No, not at all!

Dr. Buczynski: It was more from processing what happened afterwards.

Dr. Ogden: Yes, it was. And I think she said, "I've had enough of this."

She said, "I've had enough of this!" and she sat down – and then I realized what happened.

I want to normalize with therapists that we will get into our transference, counter-transference, and

dynamics with clients. We will get into those collisions – and there is nothing bad or wrong with that. They’re

important evidence for healing.

Dr. Buczynski: That's so important because it’s part of the whole process. It’s the process of working either

in our own therapy or with colleagues, or in our own meditation to

increase our awareness of that afterwards.

Dr. Ogden: Yes – and with your clients as well. I had to be willing to

say, "Yes, I was kind of pushing you, wasn't I? It was going over your

boundaries." I had to be willing to own that and validate that it was an interpersonal dynamic between us.

Dr. Buczynski: And this happened without necessarily going into your own personal history.

Dr. Ogden: Right – exactly, yes.

Dr. Buczynski: Before we leave transference, what about practitioners who are taking on the body

experience – posture, breathing patterns of their patients?

Dr. Ogden: It’s very interesting that you ask that because just yesterday I was editing a videotape of mine

where I was working with this thirteen-year-old girl who was referred by her school counselor who thought

she was going to be the next suicide at the school.

Her body was literally like this: her head was pulled to one side and her shoulders were up around her ears. I

“I had to be willing to own

that and validate that it

was an interpersonal

dynamic between us.”

“Therapists will get into

transference, counter-

transference, and

dynamics with clients.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 17

was watching myself on the video yesterday and my body was like this. I was initially horrified – because I

don't sit like this. I'm pretty aware.

Then I realized, of course, that I was mirroring her, and how important that is to establish a sense of

connection with your client.

If I had been sitting like this and she had been sitting like that,

there wouldn't be the implicit sense from her that I understood

her experience – it was the body-to-body communication.

The harm is if therapists aren't aware – they’ll often stay stuck in that posture. Posture will really influence

how you feel about yourself and how you communicate to others.

Often at the end of the day, therapists will say things like, "I just feel awful. I feel like I took on my client's

problems." I would bet that their body is taking on their client's body and not getting through that –they're

not able to release it.

Dr. Buczynski: Do you pace with the client's breathing?

Dr. Ogden: Sometimes, yes.

Dr. Buczynski: What about when their breathing is really shallow?

Dr. Ogden: It’s a natural phenomenon for us to mirror each other. All the research has shown – the

discoveries about mirror neurons – that we will mimic each other's movements and breathing.

I don't think that mirroring is a voluntary act – we do this naturally with each other. It’s an implicit way of

really resonating and connecting.

The value of working with the body is that you notice these patterns. For example, with the thirteen-year-old,

my intention in that session was to help her out of this pattern so that she could put her head on straight and

have more length in her spine.

That awareness protects me a little bit from taking that on

unconsciously. But we do take on – we do mimic and mirror

unconsciously.

Dr. Buczynski: Right, absolutely. Before we moved to transference, you referred to someone and I just want

“Posture will really

influence how you feel

about yourself and how you

communicate to others.”

“I realized that I was mirroring

her, and how important that

is to establish a sense of

connection with your client.”

“It’s a natural phenomenon for us

to mirror each other. Mirroring is

an implicit way of really

resonating and connecting.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 18

to make sure everyone heard you mention his work.

Dr. Ogden: Yes, it’s Philip Bromberg. He’s a relational psychoanalyst in New York City. He’s written many,

many wonderful papers and I think three or four books now. His most

recent book, in 2011, is Shrinking the Tsunami.

His book before that was called Awakening the Dreamer. I told him his

books are like reading literature – they’re the most poetic, beautifully written books in our field, to my

knowledge, and I highly recommend his work.

Therapy Walk-Throughs: How Therapists Should Begin

Dr. Buczynski: Now, I want to do some therapy walk-throughs. Let's start with the first phase of trauma

treatment, specifically, and how therapists should begin.

Some of the folks watching are not practicing psychotherapy; they’re most likely physicians and nurses,

occupational and physical therapists, and even teachers and pastors. Some are laypeople – but I think it still

helps to have an understanding of this whole process, at least that's what people tell us.

Dr. Ogden: Oh, I think so, too! When I think of therapists, or physicians, or teachers, or parents, they can all

benefit from the understanding of what dysregulation looks

like and how to help people regulate.

And that is the first phase of treatment, pioneered by Pierre

Janet in 1898. He said, "The first phase of trauma treatment

has to be stabilization."

When a person is destabilizing, their arousal is either too high or too low. We look for that window of

tolerance within which arousal is fairly well regulated, and when you find that, you’re stabilized.

But trauma causes arousal to escalate into hyperarousal, and then often plummet into hypoarousal. So

stabilization, in our work, is working somatically to help a person's arousal get back into the window.

This is often misunderstood in working with children. They’re called "aggressive" or "acting out," or the

“silent ones” in the corner who don't speak in school and they sit very, very quietly and don't make contact.

“Therapists, or physicians, or

teachers, or parents, can all

benefit from the understanding of

what dysregulation looks like and

how to help people regulate.”

“The value of working

with the body is that you

notice these patterns.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 19

That’s often dysregulated arousal.

With the child who is hyperaroused, for example, how can we

help their arousal get back into the window of tolerance? Sitting

still won't do it!

Dr. Buczynski: So what would you do – taking the example of the hyperaroused child and seeing that as

dysregulation and wanting to bring that back into regulation? Telling him to sit still isn't working – what

would you do?

Dr. Ogden: There are many, many ways to address it, depending on the child's physicality and how they’re

using their bodies.

I’m thinking of one little boy whose session I recently saw because now we’re developing sensorimotor

psychotherapy for children and adolescents.

He came in hyperaroused, and the therapist, Bonnie Goldstein, just gave him a therapy ball and let him

bounce on the ball as he told his story. That alone was regulating for him.

He was a child who had come in because he was frightened – he was nine years old, and he was frightened

that he was going to ragefully attack his younger brothers and sisters. His mother was frightened of that as

well, and he knew it – he said he couldn’t control himself.

So this was the first step: it was not to try to control and sit still, but to allow movement as he spoke. He was

so cute because he said he really wanted patience and control.

Another intervention that Bonnie worked with from that – it was borrowed from sensory integration – was to

take a big therapy ball and have him lie down on his belly and

press the ball, with pretty deep pressure, on his body. He

immediately felt himself calming down.

That deep pressure, then, is something his parents can help him with (outside the session).

In occupational therapy they talk about how that reorganizes the nervous system.

Some children just need that pressure to quiet down their nervous system. To try to address this from a

psychological level – that he shouldn't be feeling frightened (or whatever the feeling might be), just wasn't

“This first step was not to try

to control and sit still, but to

allow movement as he spoke.”

“With the child who is

hyperaroused how can we help

their arousal get back into the

window of tolerance?”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 20

helpful to him.

Dr. Buczynski: You also mentioned a youngster who is solemn and withdrawn. How would you try to

regulate that?

Dr. Ogden: I'm thinking of that thirteen-year-old child that was

referred to me – there had been a suicide at her school and the

counselor thought she would be the next one.

She had not spoken for a year at school. She was from a Latino

family. Nobody had told her parents. This poor girl – she had this

most luscious, beautiful dark hair that she would hide behind like this – it would fall in front of her face.

The school suggested that the parents cut her hair, so they did. But it didn’t help, of course, at all.

Dr. Buczynski: That must have even felt like more confusion.

Dr. Ogden: Worse – she was more exposed. When she came in like this, I interviewed her and her mother,

but she didn't speak at all – her mother did all the talking.

This girl’s posture held this part of her that was in such pain and felt so humiliated.

The mother had said that the daughter felt something was wrong with her, but then when the daughter got

in, she literally talked like this, and I had to be so close to her to hear – she spoke in a bare whisper like this.

This relates to Steve Porges's work – there was so much tension around her larynx, which is one of the first

signs of the social engagement system going off-line and a person feeling endangered that they start to lose

their voice.

So we worked with the part of her that was "so humiliated" – these were her words. I helped to comfort that

place in her and then worked with her posture.

My goal was definitely to prevent her suicide, so we had to address the part that felt like "going out of

existence" – that is how she put it.

But we also had to develop a part of her that could embody more confidence and self-esteem. Then, of

course, we had to work with the family; I worked with the mother and daughter during several sessions as

well.

“We had to address the part

that felt like ‘going out of

existence, but we also had to

develop a part of her that

could embody more

confidence and self-esteem.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 21

How to Reinstate Lost Resources

Dr. Buczynski: In the first phase of treatment, you’ve said that an important goal is reinstating lost

resources. What do we mean by resources?

Dr. Ogden: Resources are physical capacities that really have to do with psychological health.

In the client I just described, she had lost this resource of her head being

aligned on her shoulders and her spine having some integrity. She had lost

that with this posture.

We use all kinds of resources – from being able to reach out, being able to

defend, being able to take in what you want, being able to hold on, and being able to relax – all of these are

somatic capacities that influence our psychological well-being.

Dr. Buczynski: How are you trying, in the first phase of treatment, to develop those?

Dr. Ogden: We want to assess with the client what kind of resources they might need to help them stabilize

– to help the arousal come back into the window.

For many clients who are hypoaroused – hypoarousal has to do with

flaccidity in the musculature and a loss of action – so a resource for

them can simply be movement.

For example, with one patient I remember who was also highly dissociative, she sat down in the chair with

me and she got more and more still, more and more unable to move, and almost unable to speak.

I suggested that we just stand up and start walking around the office so that she could feel that her legs could

carry her in motion, and carry her away from something that she didn’t want and towards something that

she did.

Hers was a basic flight response – in her horrible childhood abuse, she couldn't escape. That was a lost

resource for her, and that was all implicit. Of course she could get up

and walk, but implicitly she felt trapped. Does that make sense?

Dr. Buczynski: Yes, yes. With trauma survivors, when they are in a

place where they are either experiencing hypoarousal or

“We want to assess with

the client what kind of

resources they might need

to help them stabilize.”

“Resources are physical

capacities that really

have to do with

psychological health.”

“Hers was a basic flight

response she could get up

and walk, but implicitly she

felt trapped.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 22

hyperarousal, what are you thinking about and what are your goals?

What are you trying to do to achieve them?

Dr. Ogden: I’m thinking about how their arousal can come into the

window of tolerance.

I’m assessing their bodies for two things. One is for the lost resources – like the young woman I just described

who got more and more still and couldn't move.

I was assessing and understanding that she had lost that resource of the experience of her legs being able to

carry her away.

Often people will demonstrate those resources in their own bodies,

which is very nice for therapists. If you’re tracking the body, you can see

the resources start to emerge.

For example, one patient, as she was talking about being molested by a photographer, her hands started

rubbing the tops of her legs.

We can capitalize on that natural intelligence by tracking it and making a contact statement – "Wow, I see

what your hands are doing – they’re rubbing your legs. What

happens" (and here comes the experiment) “as you feel that

movement on the tops of your legs?"

She said that it helped her ground. It helped her not to leave her body.

When we discover those resource capacities, then she could go home with the practice exercise – whenever

she felt herself starting to leave her body, she could do this action.

A therapist tracks a client's body for what somatic resources they are using, but a therapist also has to be

able to recognize what resources are missing and be able to suggest practicing those as an experiment to see

if they do bring arousal into the window.

“When we discover those

resource capacities, then

she could go home with

the practice exercise.”

“We can capitalize on

that natural intelligence

by tracking it and making

a contact statement.”

“If you’re tracking the

body, you can see the

resources start to emerge.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 23

How to Develop Interoceptive Awareness

Dr. Buczynski: Let's talk a little bit about interoceptive awareness. Sometimes, following trauma,

interoceptive awareness can be compromised and I'd like to talk about how practitioners can help their

clients develop more interoceptive awareness. But let's define it – let's just lay that out first.

Dr. Ogden: Interoceptive awareness is really the capacity to be aware

of body sensation.

The sensation is caused by movement of all kinds in your body. If I lift

my arm, there is sensation in my shoulder that wasn't there before; there is sensation from the movement of

our digestion and the movement of the blood flowing.

Clients have experienced a loss of that for many reasons. One, the body was often the battleground – you’re

often hurt physically with trauma so a natural salubrious response is to disconnect from your body – just not

feel it.

Clients often try not to feel their bodies. The bodies are often the source of mysterious physical symptoms –

pain, rapid heart rate, and dysregulation – all that doesn't cause someone to want to be in their bodies.

So our traumatized clients are often disconnected from their bodies.

Dr. Buczynski: We can't talk about trauma without thinking about memory and

how you think about memory and what you do with that. First, can we just talk

about traumatic memory and your perspective on it?

Dr. Ogden: I always think of Pierre Janet because he made that brilliant statement, "Traumatized patients

have not been able to experience the acts of triumph that they should have been able to experience."

We can think of that in many, many ways. I think of it, of course, physically – traumatized patients haven't

been able to protect themselves from the abuse, or the violation, or the

accident, or the bullet – whatever it was.

It’s very important, when we think about memory, that we’re always

working with the effects of what happened and we’re never working with

the event itself.

“Our traumatized

clients are often

disconnected from

their bodies.”

“Interoceptive awareness

is the capacity to be aware

of body sensation.”

“It’s very important that

we’re always working

with the effects of what

happened an we’re

never working with the

event itself.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 24

Bessel van der Kolk has said, "We have to get over our voyeuristic tendencies of liking to hear about what

happened." And it's true – we do, but the telling of it often exacerbates the dysregulation.

If we think about that, working with the long-lasting effects of that

memory, how the person lives in their bodies, the dysregulation of their

nervous system, and the flashbacks that they keep having, then memory

work takes on a whole different nature.

Dr. Buczynski: Is it usually implicit or explicit?

Dr. Ogden: It depends. Whether we have trauma or not, we’re dominated by what Allan Schore calls "The

right-brain implicit self."

These are the neural networks and patterns that have been laid down before language and before the left

brain have fully come online to explain things to us.

Even if we don't have trauma, the implicit patterns of the first few years of life are really strong – in all of us.

With trauma, people may have a full narrative or they may not – but it doesn't matter because you’re

working with the effects of it.

I have often worked with people who say they have birth trauma

because they have been told about it.

We know that the hippocampus isn't developed then and you

can't really remember your birth trauma, but something happens

in their bodies as soon as they think about it – and that is then what we can work with.

How to Work with Procedural Memory

Dr. Buczynski: Let's talk about procedural memory. Again, we probably we need to define what we mean by

procedural memory and then how we work with it.

Dr. Ogden: The easiest way to think about procedural memory is this way: at one point, we all had to learn

to tie our shoes, and we had to think about where to put the loop but then, once that is learned, we don't

“Even if we don't have

trauma, the implicit

patterns of the first few

years of life are really

strong – in all of us.”

“With trauma, people may

have a full narrative or they

may not – but it doesn't

matter because you’re

working with the effects of it.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 25

have to think about it anymore.

We can have a conversation while we’re tying our laces – we

don't have to think about where to put the little loop.

When you think about that psychologically, we have learned

patterns – ways of moving, gesturing, and being in physical conversation with others that is procedural.

Once we learn it, it’s regulated by the lower brain; it’s no longer regulated by our conscious, thinking brain so

it is just pattern – just procedural.

That procedural learning from early on really shapes our movement and how we live in our bodies. That is

what we’re interested in shifting through sensorimotor psychotherapy.

Dr. Buczynski: I'm so sorry that we have to stop, that we have to wrap up, but I was just now thinking, "I

could talk to this woman for a long time – we could really get into

'How do you see this, or this, or this?'"

Dr. Ogden: Yes – it's really a pleasure.

Dr. Buczynski: I just want to say thank you for being with us and

sharing your thoughts, teaching us more about a very special, unique

way of seeing and working with trauma.

Thanks for all the people that you have taught all over the world. Everyone, take good care – and good night.

“We have learned patterns –

ways of moving, gesturing, and

being in physical conversation

with others that is procedural.”

“Procedural learning from

early on shapes our

movement and how we live

in our bodies. That is what

we’re interested in shifting

through sensorimotor

psychotherapy.”

The Body's Critical Role in the Treatment of Trauma Pat Ogden, PhD - Main Session - pg. 26

Pat Ogden, PhD is a pioneer in somatic

psychology having trained in a wide variety of somatic

and psychotherapeutic approaches. She has 34 years

experience working with individuals and groups in

diverse populations. She is first author of the

groundbreaking book, Trauma and the Body: A

Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy.

Dr. Ogden is both founder and director of the

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute. She is a

clinician, consultant, international lecturer and

trainer, co-founder of the Hakomi Institute, and on faculty at Naropa University. She has

published the book Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment.

Ruth Buczynski, PhD has been combining her commitment to mind/body medicine

with a savvy business model since 1989. As the founder

and president of the National Institute for the Clinical

Application of Behavioral Medicine, she’s been a leader

in bringing innovative training and professional

development programs to thousands of health and

mental health care practitioners throughout the world.

Ruth has successfully sponsored distance-learning

programs, teleseminars, and annual conferences for

over 20 years. Now she’s expanded into the ‘cloud,’

where she’s developed intelligent and thoughtfully

researched webinars that continue to grow exponentially.

About the speakers . . .